European Literature on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Western literature, also known as European literature, is the

As the

As the

The earliest vernacular literary tradition in Italy was in

The earliest vernacular literary tradition in Italy was in

The ''Historia de excidio Trojae'', attributed to

The ''Historia de excidio Trojae'', attributed to

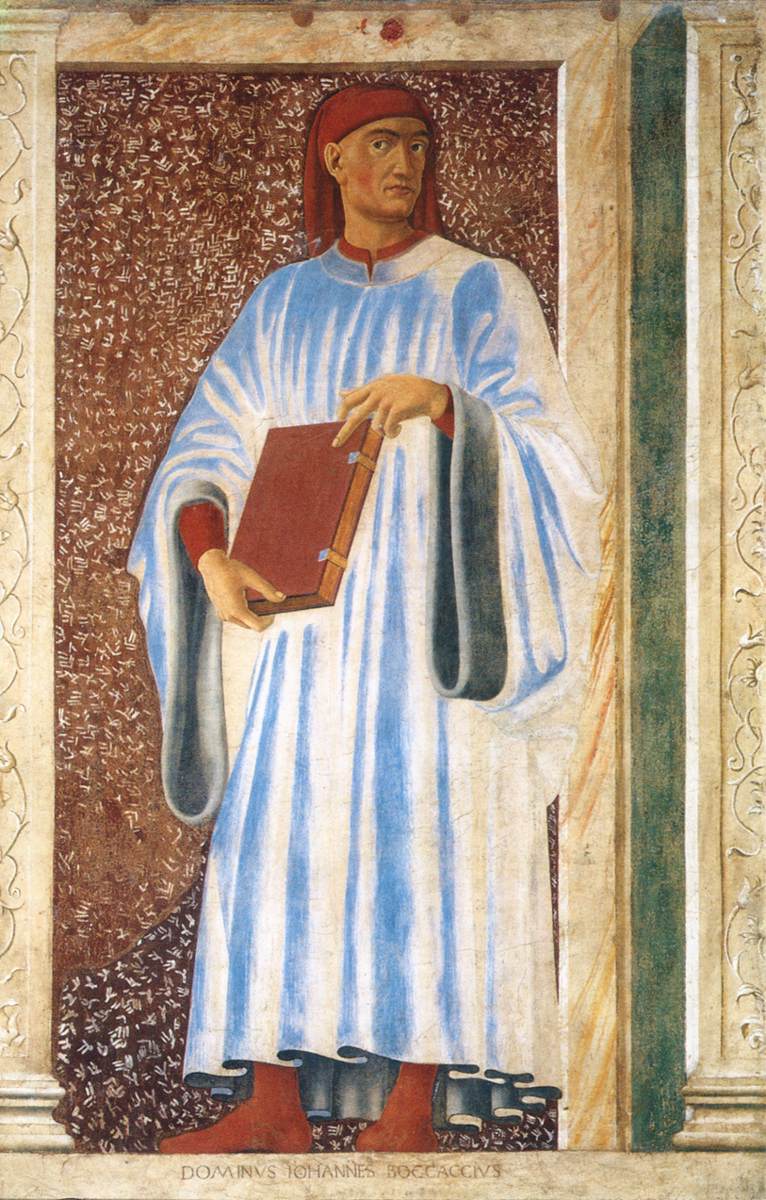

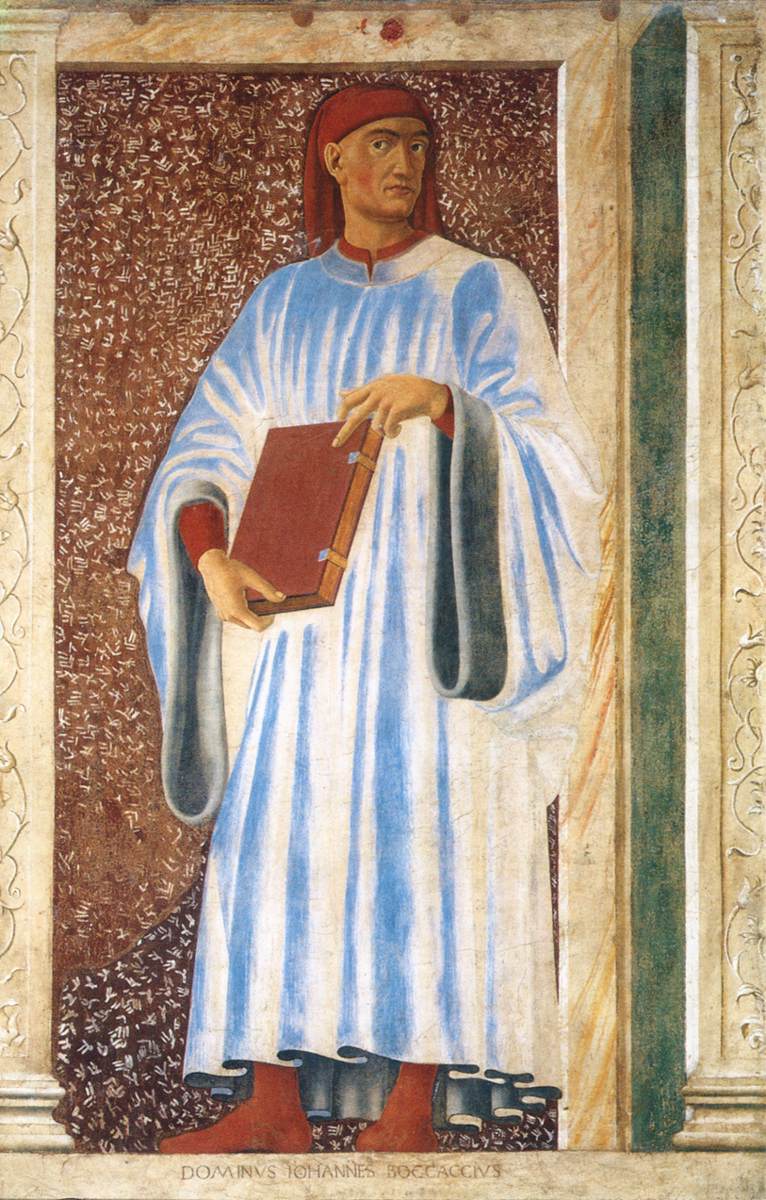

Petrarch was the first

Petrarch was the first

Leone Battista Alberti, the learned Greek and Latin scholar, wrote in the vernacular, and Vespasiano da Bisticci, while he was constantly absorbed in Greek and Latin manuscripts, wrote the ''Vite di uomini illustri'', valuable for their historical contents, and rivalling the best works of the 14th century in their candour and simplicity. Andrea da Barberino wrote the beautiful prose of the ''Reali di Francia'', giving a coloring of ''romanità'' to the chivalrous romances. Feo Belcari, Belcari and Girolamo Benivieni returned to the mystic idealism of earlier times.

But it is in Cosimo de' Medici and Lorenzo de' Medici, from 1430 to 1492, that the influence of Florence on the Renaissance is particularly seen. Lorenzo de' Medici gave to his poetry the colors of the most pronounced realism as well as of the loftiest idealism, who passes from the Platonic sonnet to the impassioned triplets of the ''Amori di Venere'', from the grandiosity of the ''Salve to Nencia'' and to Beoni, from the ''Canto carnascialesco'' to the ''lauda''.

Next to Lorenzo comes Poliziano, who also united, and with greater art, the ancient and the modern, the popular and the classical style. In his ''Rispetti'' and in his ''Ballate'' the freshness of imagery and the plasticity of form are inimitable. A great Greek scholar, Poliziano wrote Italian verses with dazzling colours; the purest elegance of the Greek sources pervaded his art in all its varieties, in the ''Orfeo'' as well as the ''Stanze per la giostra''.

A completely new style of poetry arose, the ''Canto carnascialesco''. These were a type of choral songs, which were accompanied by symbolic masquerades, common in Florence at the carnival. They were written in a metre like that of the ''ballate''; and for the most part, they were put into the mouth of a party of workmen and tradesmen, who, with not very chaste allusions, sang the praises of their art. These triumphs and masquerades were directed by Lorenzo himself. In the evening, there set out into the city large companies on horseback, playing and singing these songs. There are some by Lorenzo himself, which surpass all the others in their mastery of art. That entitled ''Bacco ed Arianna'' is the most famous.

Leone Battista Alberti, the learned Greek and Latin scholar, wrote in the vernacular, and Vespasiano da Bisticci, while he was constantly absorbed in Greek and Latin manuscripts, wrote the ''Vite di uomini illustri'', valuable for their historical contents, and rivalling the best works of the 14th century in their candour and simplicity. Andrea da Barberino wrote the beautiful prose of the ''Reali di Francia'', giving a coloring of ''romanità'' to the chivalrous romances. Feo Belcari, Belcari and Girolamo Benivieni returned to the mystic idealism of earlier times.

But it is in Cosimo de' Medici and Lorenzo de' Medici, from 1430 to 1492, that the influence of Florence on the Renaissance is particularly seen. Lorenzo de' Medici gave to his poetry the colors of the most pronounced realism as well as of the loftiest idealism, who passes from the Platonic sonnet to the impassioned triplets of the ''Amori di Venere'', from the grandiosity of the ''Salve to Nencia'' and to Beoni, from the ''Canto carnascialesco'' to the ''lauda''.

Next to Lorenzo comes Poliziano, who also united, and with greater art, the ancient and the modern, the popular and the classical style. In his ''Rispetti'' and in his ''Ballate'' the freshness of imagery and the plasticity of form are inimitable. A great Greek scholar, Poliziano wrote Italian verses with dazzling colours; the purest elegance of the Greek sources pervaded his art in all its varieties, in the ''Orfeo'' as well as the ''Stanze per la giostra''.

A completely new style of poetry arose, the ''Canto carnascialesco''. These were a type of choral songs, which were accompanied by symbolic masquerades, common in Florence at the carnival. They were written in a metre like that of the ''ballate''; and for the most part, they were put into the mouth of a party of workmen and tradesmen, who, with not very chaste allusions, sang the praises of their art. These triumphs and masquerades were directed by Lorenzo himself. In the evening, there set out into the city large companies on horseback, playing and singing these songs. There are some by Lorenzo himself, which surpass all the others in their mastery of art. That entitled ''Bacco ed Arianna'' is the most famous.

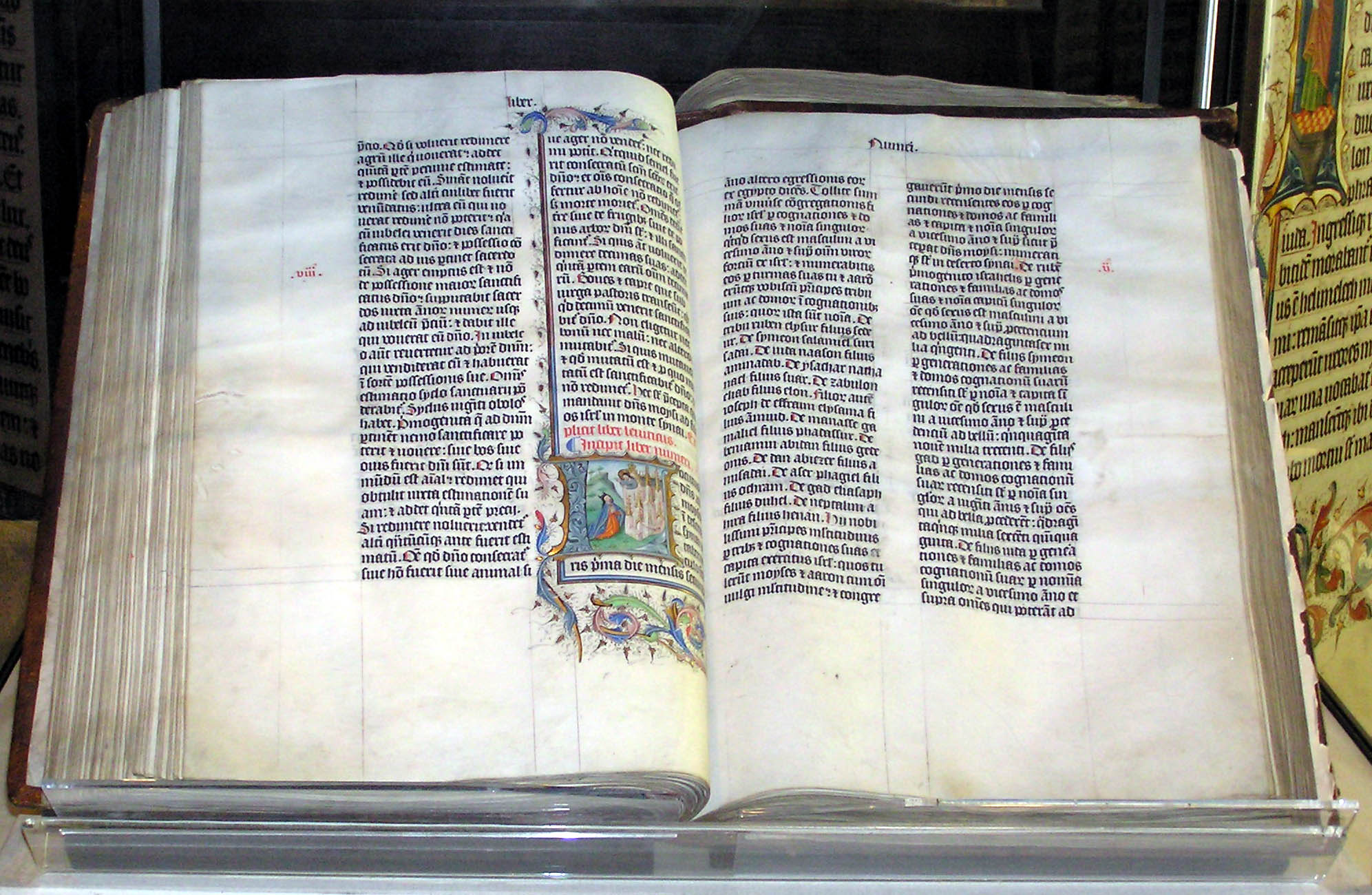

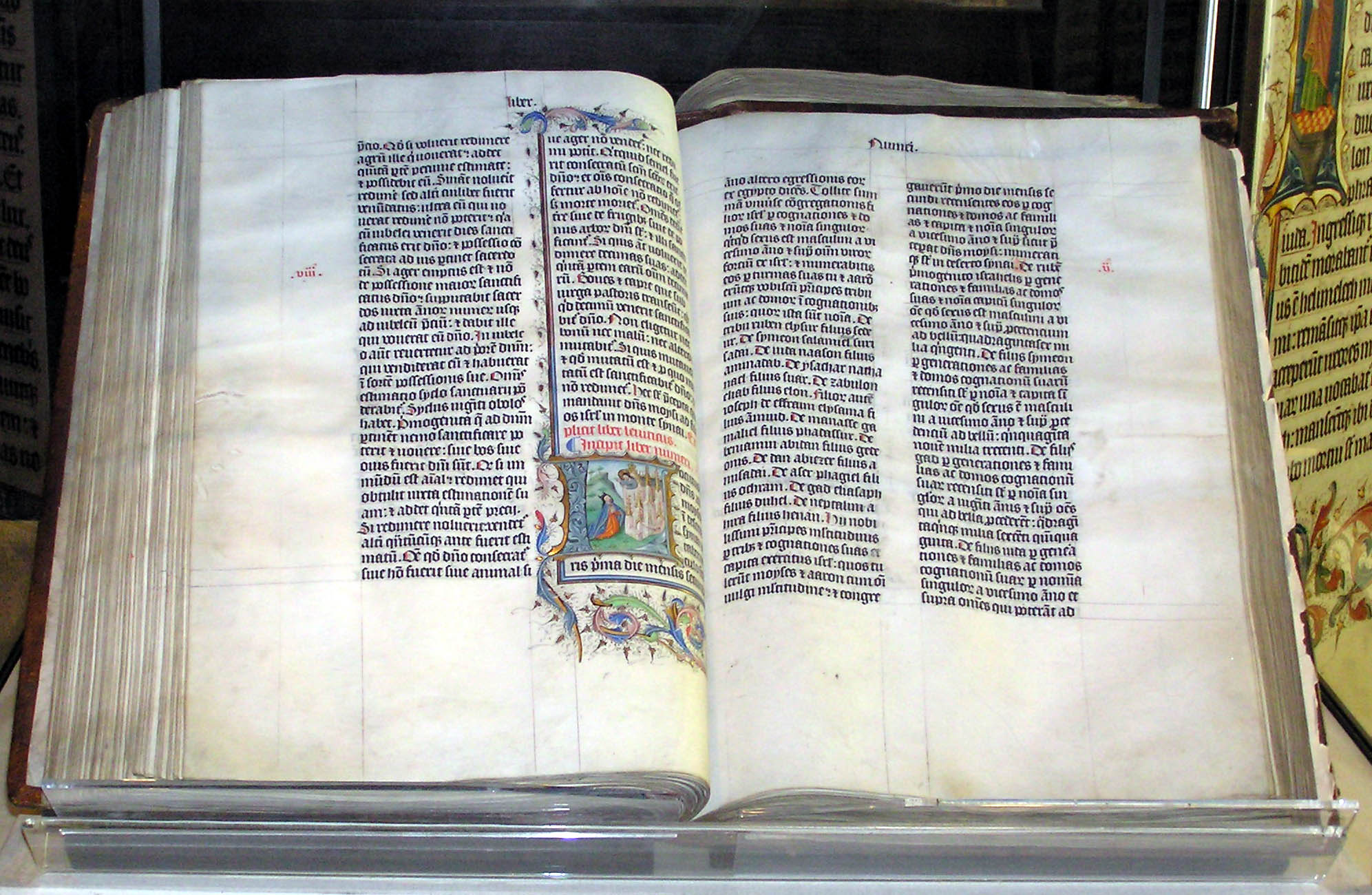

Prose and poetic literature within western regions, most prominently in England during the early modern era, had a distinct Bible, Biblical influence which only began to be rejected during the Enlightenment period of the 18th century. European poetry during the 17th century tended to meditate on or reference the scriptures and teachings of the Bible, an example being orator George Herbert's "The Holy Scriptures (II)", in which Herbert relies heavily on biblical ligatures to create his sonnets.

Prose and poetic literature within western regions, most prominently in England during the early modern era, had a distinct Bible, Biblical influence which only began to be rejected during the Enlightenment period of the 18th century. European poetry during the 17th century tended to meditate on or reference the scriptures and teachings of the Bible, an example being orator George Herbert's "The Holy Scriptures (II)", in which Herbert relies heavily on biblical ligatures to create his sonnets.

The Jacobean era, Jacobean period of 17th-century England gave birth to a group of Metaphysics, metaphysic literary figures, metaphysical referring to a branch of philosophy which tries to bring meaning to and explain reality using broader and larger concepts. In order to do this, the use of literary features including conceits was common, in which the writer makes obscure comparisons in order to convey a message or persuade a point.

The term metaphysics was coined by poet John Dryden, and during 1779 its meaning was extended to represent a group of poets of the time, then called "metaphysical poets". Major poets of the time included John Donne, Andrew Marvell and George Herbert. These poets used wit and high intellectual standards while drawing from nature to reveal insights about emotion and rejected the romantic attributes of the Elizabethan era, Elizabethan period to birth a more analytical and introspective form of writing. A common literary device during the 17th century was the use of metaphysical conceits, in which the poet uses "unorthodox language" to describe a relatable concept. It is beneficial when trying to bring light to concepts that are difficult to explain with more common imagery.

John Donne was a prominent metaphysical poet of the 17th century. Donne's poetry explored the pleasures of life through strong use of conceits and emotive language. Donne adopted a more simplistic vernacular compared to the common Petrarchan sonnet, Petrarchan diction, with imagery derived mainly from God. Donne was known for the metaphysical conceits integrated in his poetry. He used themes of religion, death and love to inspire the conceits he constructed. A famous conceit is observed in his well-known poem "The Flea (poem), The Flea" in which the flea is utilised to describe the bond between Donne and his lover, explaining how just as multiple bloods are within one flea, their bond is inseparable.

The Jacobean era, Jacobean period of 17th-century England gave birth to a group of Metaphysics, metaphysic literary figures, metaphysical referring to a branch of philosophy which tries to bring meaning to and explain reality using broader and larger concepts. In order to do this, the use of literary features including conceits was common, in which the writer makes obscure comparisons in order to convey a message or persuade a point.

The term metaphysics was coined by poet John Dryden, and during 1779 its meaning was extended to represent a group of poets of the time, then called "metaphysical poets". Major poets of the time included John Donne, Andrew Marvell and George Herbert. These poets used wit and high intellectual standards while drawing from nature to reveal insights about emotion and rejected the romantic attributes of the Elizabethan era, Elizabethan period to birth a more analytical and introspective form of writing. A common literary device during the 17th century was the use of metaphysical conceits, in which the poet uses "unorthodox language" to describe a relatable concept. It is beneficial when trying to bring light to concepts that are difficult to explain with more common imagery.

John Donne was a prominent metaphysical poet of the 17th century. Donne's poetry explored the pleasures of life through strong use of conceits and emotive language. Donne adopted a more simplistic vernacular compared to the common Petrarchan sonnet, Petrarchan diction, with imagery derived mainly from God. Donne was known for the metaphysical conceits integrated in his poetry. He used themes of religion, death and love to inspire the conceits he constructed. A famous conceit is observed in his well-known poem "The Flea (poem), The Flea" in which the flea is utilised to describe the bond between Donne and his lover, explaining how just as multiple bloods are within one flea, their bond is inseparable.

At the head of the school of the ''Secentisti'' was Giambattista Marino, especially known for his epic poem, ''L'Adone''. Marino himself, as he declared in the Preface to ''La lira'', wished to be a new leader and model for other poets. Second, he wished to surprise and shock the reader through the marvellous (''meraviglioso'') and the unusual (''peregrino''). The qualities he and his followers most valued were ''ingegno'' and ''acutezza'', as demonstrated through far-fetched metaphors and conceits, often ones that would assault the reader's senses. This meant being ready, in fact eager, to break literary rules and precepts. Marino and his followers mixed tradition and innovation: they worked with existing poetic forms, notably the sonnet, the sestina, the canzone, the madrigal, and less frequently the ottava rima, but developed new, more fluid structures and line lengths. They also treated hallowed themes (love, woman, nature), but they made the senses and sensuality the dominant element. The passions, which had attracted the attention of Paduan writers and theorists in the mid-16th century as well as of Tasso, take centre stage, and are depicted in extreme forms in representations of subjects such as martyrdom, sacrifice, heroic grandeur, and abysmal existential fear. The Marinists also take up new themes—notably the visual and musical arts and indoor scenes—with a new repertoire of references embracing modern scientific advances, other specialized branches of knowledge, and exotic locations and animals. There are similarities with Tasso, but the balance between form and content in Tasso is deliberately unbalanced by Marino and his followers, who very often forget all concerns about unity in their poems (witness the ''Adone''). The most striking difference, however, is the intensified role of metaphor. Marino and his followers looked for metaphors that would arrest the reader by suggesting a likeness between two apparently disparate things, thus producing startling metamorphoses, conceits (''concetti''), and far-fetched images that send sparks flying as they create a friction between two apparently diverse objects. The extent to which this new metaphorical freedom reveals a new world is still open to critical debate. In some ways it seems to make poetry a form of intellectual game or puzzle; in others it suggests new ways of perceiving and describing reality, parallel to the mathematical measures employed by Galileo and his followers in the experimental sciences.

Almost all the poets of the 17th century were more or less influenced by Marinism. Many ''secentisti'' felt the influence of another poet, Gabriello Chiabrera. Enamoured of the Greeks, he made new metres, especially in imitation of Pindar, treating of religious, moral, historical, and amatory subjects. Carlo Alessandro Guidi was the chief representative of an early Pindarizing current based on imitation of Chiabrera as second only to Petrarch in Italian poetry. He was extolled by both Gravina and Crescimbeni, who edited his poetry (1726), and imitated by Parini. Alfieri attributed his own self-discovery to the power of Guidi's verse. Fulvio Testi was another major exponent of the Hellenizing strand of Baroque classicism, combining Horatianism with the imitation of Anacreon and Pindar. His most important and interesting writings are not, however, his lyrics (only collected in 1653), but his extensive correspondence, which is a major document of Baroque politics and letters.

At the head of the school of the ''Secentisti'' was Giambattista Marino, especially known for his epic poem, ''L'Adone''. Marino himself, as he declared in the Preface to ''La lira'', wished to be a new leader and model for other poets. Second, he wished to surprise and shock the reader through the marvellous (''meraviglioso'') and the unusual (''peregrino''). The qualities he and his followers most valued were ''ingegno'' and ''acutezza'', as demonstrated through far-fetched metaphors and conceits, often ones that would assault the reader's senses. This meant being ready, in fact eager, to break literary rules and precepts. Marino and his followers mixed tradition and innovation: they worked with existing poetic forms, notably the sonnet, the sestina, the canzone, the madrigal, and less frequently the ottava rima, but developed new, more fluid structures and line lengths. They also treated hallowed themes (love, woman, nature), but they made the senses and sensuality the dominant element. The passions, which had attracted the attention of Paduan writers and theorists in the mid-16th century as well as of Tasso, take centre stage, and are depicted in extreme forms in representations of subjects such as martyrdom, sacrifice, heroic grandeur, and abysmal existential fear. The Marinists also take up new themes—notably the visual and musical arts and indoor scenes—with a new repertoire of references embracing modern scientific advances, other specialized branches of knowledge, and exotic locations and animals. There are similarities with Tasso, but the balance between form and content in Tasso is deliberately unbalanced by Marino and his followers, who very often forget all concerns about unity in their poems (witness the ''Adone''). The most striking difference, however, is the intensified role of metaphor. Marino and his followers looked for metaphors that would arrest the reader by suggesting a likeness between two apparently disparate things, thus producing startling metamorphoses, conceits (''concetti''), and far-fetched images that send sparks flying as they create a friction between two apparently diverse objects. The extent to which this new metaphorical freedom reveals a new world is still open to critical debate. In some ways it seems to make poetry a form of intellectual game or puzzle; in others it suggests new ways of perceiving and describing reality, parallel to the mathematical measures employed by Galileo and his followers in the experimental sciences.

Almost all the poets of the 17th century were more or less influenced by Marinism. Many ''secentisti'' felt the influence of another poet, Gabriello Chiabrera. Enamoured of the Greeks, he made new metres, especially in imitation of Pindar, treating of religious, moral, historical, and amatory subjects. Carlo Alessandro Guidi was the chief representative of an early Pindarizing current based on imitation of Chiabrera as second only to Petrarch in Italian poetry. He was extolled by both Gravina and Crescimbeni, who edited his poetry (1726), and imitated by Parini. Alfieri attributed his own self-discovery to the power of Guidi's verse. Fulvio Testi was another major exponent of the Hellenizing strand of Baroque classicism, combining Horatianism with the imitation of Anacreon and Pindar. His most important and interesting writings are not, however, his lyrics (only collected in 1653), but his extensive correspondence, which is a major document of Baroque politics and letters.

Marino's work, with its sensual metaphorical language and its non-epic structure and morality, stirred up a debate over the rival claims of classical purity and sobriety on the one hand and the excesses of marinism on the other. The debate went on until it was finally decided in favour of the classical by the Accademia dell'Arcadia, whose view of the matter prevailed in Italian criticism well into the 20th century. The Accademia dell'Arcadia was founded by Giovanni Mario Crescimbeni and Gian Vincenzo Gravina in 1690. The ''Arcadia'' was so called because its chief aim was to imitate the simplicity of the ancient shepherds who were supposed to have lived in Arcadia (utopia), Arcadia in the golden age. The poems of the Arcadians are made up of sonnets, madrigal (music), madrigals, ''canzonette'' and blank verse. The one who most distinguished himself among the sonneteers was Felice Zappi. Among the authors of songs, Paolo Rolli was illustrious. Carlo Innocenzo Frugoni was the best known. The members of the Arcadia were almost exclusively men, but at least one woman, Maria Antonia Scalera Stellini, was elected on poetical merits. Vincenzo da Filicaja had a lyric talent, particularly in the songs about Vienna besieged by the Ottoman Empire, Turks.

The philosopher, theologian, astrologer, and poet Tommaso Campanella is an interesting albeit isolated figure in 17th century Italian literature. His ''Poesie'', published in 1622, consist of eighty-nine poems in various metrical forms. Some are autobiographical, but all are stamped with a seriousness and directness which bypasses the literary fashions of his day. He wrote in Latin on dialectics, rhetoric, poetics, and historiography, as well as the Italian ''Del senso delle cose e della magia'', composed in 1604 and published in 1620. In this fascinating work, influenced by the teachings of Bernardino Telesio, Campanella imagines the world as a living statue of God, in which all aspects of reality have meaning and sense. With its animism and sensuality this vision foreshadows in many ways the views of Daniello Bartoli and Tesauro. Campanella's theological work, closely connected with his philosophical writings, includes the ''Atheismus triumphatus'' and the thirty-volume ''Theologia'' (1613–24). His most famous work, and the one that brings together all his interests, is ''La città del sole'', first drafted in 1602 in Italian and then later translated into Latin in 1613 and 1631. In it a Genoese sailor from Christopher Columbus' crew describes the ideal state of the City of the Sun ruled over in both temporal and spiritual matters by the Prince Priest, called Sun or Metaphysician. Under him there are three ministers: Power (concerned with war and peace), Wisdom (concerned with science and art, all written down in one book), and Love (concerned with procreation and education of the citizens of the Sun). The life of the citizens is based on a system of communism: all property is held publicly, there are no families, no rights of inheritance, no marriage, and sexual relations are regulated by the state. Everyone has his or her function in the society, and certain duties are required of all citizens. Education is the perfect training of the mind and the body, and it is radically opposed to the bookish and academic culture of Renaissance Italy: the objects of study should be not 'dead things' but nature and the mathematical and physical laws that govern the physical world. There are links here with the burgeoning modernism of the ''Quarrel of the Ancients and the Moderns, Querelle des anciens et des modernes'', and with the methods and scientific aspirations of Galileo, whom Campanella defended in writing in 1616.

The Lyncean Academy, the first and most famous of the scientific academies in Italy, was founded in 1603 in Rome by Federico Cesi. The academy dedicated its activities to the study of the natural and mathematical sciences and to the use of the experimental method associated with Galileo. The European dimension of the academy was characteristic of the founders' foresight and perspective: elections were made of foreign corresponding members, a practice that continues to this day. Members included Claudio Achillini, Pietro Della Valle, Galileo (from 1611), Francesco Sforza Pallavicino, Giambattista della Porta, Giambattista Della Porta (from 1610 ), and Filippo Salviati. Their work involved the large-scale publishing of scientific results based on direct observation, including Galileo's work on the moon's surface (1610) and his ''The Assayer, Assayer'' (1623). The academy defended Galileo at his trial in 1616, and played a crucial role in the early diffusion and promotion of his method.

The successor of the Lynceans was the Accademia del Cimento, founded in Florence in 1657. Never as organized as the Lynceans had been, it began as a meeting of disciples of Galileo, all of whom were interested in the progress of the experimental sciences. Official status came in 1657, when cardinal Leopoldo de' Medici, Leopoldo de' Medici sponsored the academy's foundation. With the motto 'provando e riprovando', the members, including Carlo Roberto Dati, Lorenzo Magalotti, and Vincenzo Viviani, set seriously about their work. Unlike Galileo, who tackled large-scale issues, the Cimento worked on a smaller scale. One of the legacies of the Cimento is the elegant Italian prose, capable of describing things accurately, that characterizes the ''Saggi di naturali esperienze'' edited by Magalotti and published in 1667.

Galileo Galilei, Galileo occupied a conspicuous place in the history of letters. A devoted student of Ariosto, he seemed to transfuse into his prose the qualities of that great poet: clear and frank freedom of expression, precision and ease, and at the same time elegance. Paganino Bonafede in the ''Tesoro dei rustici'' gave many precepts in agriculture, beginning that type of georgic poetry later fully developed by Luigi Alamanni in his ''Coltivazione'', by Girolamo Baruffaldi in the ''Canapajo'', by Giovanni di Bernardo Rucellai, Rucellai in ''Le Api'', by Bartolomeo Lorenzi in the ''Coltivazione de' monti'', and by Giambattista Spolverini in the ''Coltivazione del riso''.

Marino's work, with its sensual metaphorical language and its non-epic structure and morality, stirred up a debate over the rival claims of classical purity and sobriety on the one hand and the excesses of marinism on the other. The debate went on until it was finally decided in favour of the classical by the Accademia dell'Arcadia, whose view of the matter prevailed in Italian criticism well into the 20th century. The Accademia dell'Arcadia was founded by Giovanni Mario Crescimbeni and Gian Vincenzo Gravina in 1690. The ''Arcadia'' was so called because its chief aim was to imitate the simplicity of the ancient shepherds who were supposed to have lived in Arcadia (utopia), Arcadia in the golden age. The poems of the Arcadians are made up of sonnets, madrigal (music), madrigals, ''canzonette'' and blank verse. The one who most distinguished himself among the sonneteers was Felice Zappi. Among the authors of songs, Paolo Rolli was illustrious. Carlo Innocenzo Frugoni was the best known. The members of the Arcadia were almost exclusively men, but at least one woman, Maria Antonia Scalera Stellini, was elected on poetical merits. Vincenzo da Filicaja had a lyric talent, particularly in the songs about Vienna besieged by the Ottoman Empire, Turks.

The philosopher, theologian, astrologer, and poet Tommaso Campanella is an interesting albeit isolated figure in 17th century Italian literature. His ''Poesie'', published in 1622, consist of eighty-nine poems in various metrical forms. Some are autobiographical, but all are stamped with a seriousness and directness which bypasses the literary fashions of his day. He wrote in Latin on dialectics, rhetoric, poetics, and historiography, as well as the Italian ''Del senso delle cose e della magia'', composed in 1604 and published in 1620. In this fascinating work, influenced by the teachings of Bernardino Telesio, Campanella imagines the world as a living statue of God, in which all aspects of reality have meaning and sense. With its animism and sensuality this vision foreshadows in many ways the views of Daniello Bartoli and Tesauro. Campanella's theological work, closely connected with his philosophical writings, includes the ''Atheismus triumphatus'' and the thirty-volume ''Theologia'' (1613–24). His most famous work, and the one that brings together all his interests, is ''La città del sole'', first drafted in 1602 in Italian and then later translated into Latin in 1613 and 1631. In it a Genoese sailor from Christopher Columbus' crew describes the ideal state of the City of the Sun ruled over in both temporal and spiritual matters by the Prince Priest, called Sun or Metaphysician. Under him there are three ministers: Power (concerned with war and peace), Wisdom (concerned with science and art, all written down in one book), and Love (concerned with procreation and education of the citizens of the Sun). The life of the citizens is based on a system of communism: all property is held publicly, there are no families, no rights of inheritance, no marriage, and sexual relations are regulated by the state. Everyone has his or her function in the society, and certain duties are required of all citizens. Education is the perfect training of the mind and the body, and it is radically opposed to the bookish and academic culture of Renaissance Italy: the objects of study should be not 'dead things' but nature and the mathematical and physical laws that govern the physical world. There are links here with the burgeoning modernism of the ''Quarrel of the Ancients and the Moderns, Querelle des anciens et des modernes'', and with the methods and scientific aspirations of Galileo, whom Campanella defended in writing in 1616.

The Lyncean Academy, the first and most famous of the scientific academies in Italy, was founded in 1603 in Rome by Federico Cesi. The academy dedicated its activities to the study of the natural and mathematical sciences and to the use of the experimental method associated with Galileo. The European dimension of the academy was characteristic of the founders' foresight and perspective: elections were made of foreign corresponding members, a practice that continues to this day. Members included Claudio Achillini, Pietro Della Valle, Galileo (from 1611), Francesco Sforza Pallavicino, Giambattista della Porta, Giambattista Della Porta (from 1610 ), and Filippo Salviati. Their work involved the large-scale publishing of scientific results based on direct observation, including Galileo's work on the moon's surface (1610) and his ''The Assayer, Assayer'' (1623). The academy defended Galileo at his trial in 1616, and played a crucial role in the early diffusion and promotion of his method.

The successor of the Lynceans was the Accademia del Cimento, founded in Florence in 1657. Never as organized as the Lynceans had been, it began as a meeting of disciples of Galileo, all of whom were interested in the progress of the experimental sciences. Official status came in 1657, when cardinal Leopoldo de' Medici, Leopoldo de' Medici sponsored the academy's foundation. With the motto 'provando e riprovando', the members, including Carlo Roberto Dati, Lorenzo Magalotti, and Vincenzo Viviani, set seriously about their work. Unlike Galileo, who tackled large-scale issues, the Cimento worked on a smaller scale. One of the legacies of the Cimento is the elegant Italian prose, capable of describing things accurately, that characterizes the ''Saggi di naturali esperienze'' edited by Magalotti and published in 1667.

Galileo Galilei, Galileo occupied a conspicuous place in the history of letters. A devoted student of Ariosto, he seemed to transfuse into his prose the qualities of that great poet: clear and frank freedom of expression, precision and ease, and at the same time elegance. Paganino Bonafede in the ''Tesoro dei rustici'' gave many precepts in agriculture, beginning that type of georgic poetry later fully developed by Luigi Alamanni in his ''Coltivazione'', by Girolamo Baruffaldi in the ''Canapajo'', by Giovanni di Bernardo Rucellai, Rucellai in ''Le Api'', by Bartolomeo Lorenzi in the ''Coltivazione de' monti'', and by Giambattista Spolverini in the ''Coltivazione del riso''.

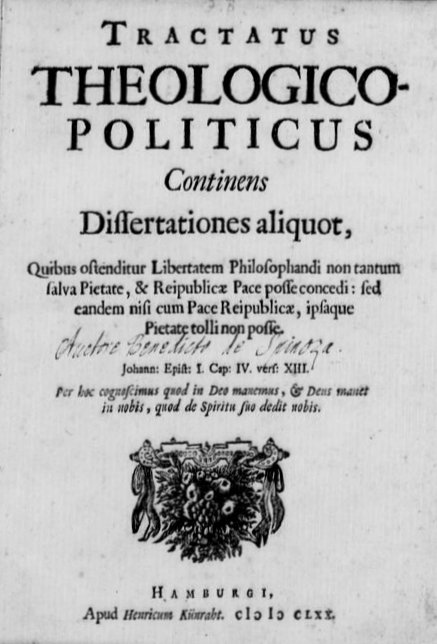

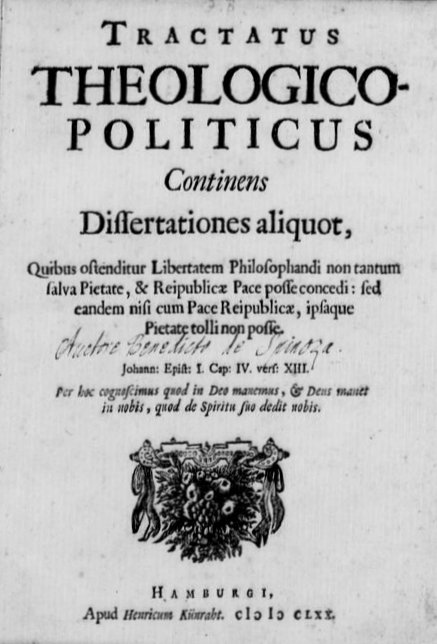

Significant texts which shaped this literary period include ''Tractatus Theologico-Politicus'', an anonymously published treatise in Amsterdam in which the author, Baruch Spinoza, Spinoza, rejected the Jewish and Christian religions for their lack of depth in teaching. Spinoza discussed higher levels of philosophy in his treatise, which he suggested was only understood by elitists. This text is one of many during this period which attributed to the increasing "anti-religious" support during the time of Enlightenment. Although the book held great influence, other writers of the time rejected Spinoza's views, including theologian Lambert van Valthuysen.

Significant texts which shaped this literary period include ''Tractatus Theologico-Politicus'', an anonymously published treatise in Amsterdam in which the author, Baruch Spinoza, Spinoza, rejected the Jewish and Christian religions for their lack of depth in teaching. Spinoza discussed higher levels of philosophy in his treatise, which he suggested was only understood by elitists. This text is one of many during this period which attributed to the increasing "anti-religious" support during the time of Enlightenment. Although the book held great influence, other writers of the time rejected Spinoza's views, including theologian Lambert van Valthuysen.

Giambattista Vico showed the awakening of historical consciousness in Italy. In his ''Scienza nuova'', he investigated the laws governing the progress of the human race, and according to which events develop. From the psychological study of man, he tried to infer the ''comune natura delle nazioni'', i.e., the universal laws of history.

Lodovico Antonio Muratori, after having collected in his ''Rerum Italicarum scriptores'' the chronicles, biographies, letters and diaries of Italian history from 500 to 1500, and having discussed the most obscure historical questions in the ''Antiquitates Italicae medii aevi'', wrote the ''Annali d'Italia'', minutely narrating facts derived from authentic sources. Muratori's associates in his historical research were Scipione Maffei of Verona and Apostolo Zeno of Venice. In his ''Verona illustrata'' Maffei left a treasure of learning that was also an excellent historical monograph. Zeno added much to the erudition of literary history, both in his ''Dissertazioni Vossiane'' and in his notes to the ''Biblioteca dell'eloquenza italiana'' of Monsignore Giusto Fontanini. Girolamo Tiraboschi and Count Giammaria Mazzucchelli of Brescia devoted themselves to literary history.

While the new spirit of the times led to the investigation of historical sources, it also encouraged inquiry into the mechanism of economic and social laws. Ferdinando Galiani wrote on currency; Gaetano Filangieri wrote a ''Scienza della legislazione''. Cesare Beccaria, in his ''On Crimes and Punishments, Trattato dei delitti e delle pene'', made a contribution to the reform of the penal system and promoted the abolition of torture.

The reforming movement sought to throw off the conventional and the artificial, and to return to truth. Apostolo Zeno and Pietro Metastasio had endeavoured to make melodrama and reason compatible. Metastasio gave fresh expression to the affections, a natural turn to the dialogue and some interest to the plot; if he had not fallen into constant unnatural overrefinement and mawkishness, and into frequent anachronisms, he might have been considered the most important writer of ''opera seria'' libretti and the first dramatic reformer of the 18th century.

Carlo Goldoni overcame resistance from the old popular form of comedy, with the masks of ''pantalone'', of the doctor, ''harlequin'', Brighella, etc., and created the comedy of character, following Molière's example. Many of his comedies were written in Venetian language, Venetian. His works include some of Italy's most famous and best-loved plays. Goldoni also wrote under the pen name and title ''Polisseno Fegeio, Pastor Arcade'', which he claimed in his memoirs the "Accademia degli Arcadi, Arcadians of Rome" bestowed on him. One of his best-known works is the comic play ''Servant of Two Masters'', which has been translated and adapted internationally numerous times.

The leading figure of the literary revival of the 18th century was Giuseppe Parini. In a collection of poems he published at twenty-three years of age, under the name of Ripano Eupilino, the poet shows his faculty of taking his scenes from real life, and in his satirical pieces he exhibits a spirit of outspoken opposition to his own times. Improving on the poems of his youth, he showed himself an innovator in his lyrics, rejecting at once Petrarchism, ''Secentismo'' and Arcadia. In the ''Odi'' the satirical note is already heard, but it comes out more strongly in ''Del giorno'', which assumes major social and historical value. As an artist, going straight back to classical forms, he opened the way to the school of Vittorio Alfieri, Ugo Foscolo and Vincenzo Monti. As a work of art, the ''Giorno'' is sometimes a little hard and broken, as a protest against the Arcadian monotony.

The ideas behind the French Revolution of 1789 gave a special direction to Italian literature in the second half of the 18th century. Love of liberty and desire for equality created a literature aimed at national objects, seeking to improve the condition of the country by freeing it from the double yoke of political and religious despotism. The Italians who aspired to political redemption believed it inseparable from an intellectual revival, and thought that this could only be effected by a reunion with ancient classicism. This was a repetition of what had occurred in the first half of the 15th century.

Giambattista Vico showed the awakening of historical consciousness in Italy. In his ''Scienza nuova'', he investigated the laws governing the progress of the human race, and according to which events develop. From the psychological study of man, he tried to infer the ''comune natura delle nazioni'', i.e., the universal laws of history.

Lodovico Antonio Muratori, after having collected in his ''Rerum Italicarum scriptores'' the chronicles, biographies, letters and diaries of Italian history from 500 to 1500, and having discussed the most obscure historical questions in the ''Antiquitates Italicae medii aevi'', wrote the ''Annali d'Italia'', minutely narrating facts derived from authentic sources. Muratori's associates in his historical research were Scipione Maffei of Verona and Apostolo Zeno of Venice. In his ''Verona illustrata'' Maffei left a treasure of learning that was also an excellent historical monograph. Zeno added much to the erudition of literary history, both in his ''Dissertazioni Vossiane'' and in his notes to the ''Biblioteca dell'eloquenza italiana'' of Monsignore Giusto Fontanini. Girolamo Tiraboschi and Count Giammaria Mazzucchelli of Brescia devoted themselves to literary history.

While the new spirit of the times led to the investigation of historical sources, it also encouraged inquiry into the mechanism of economic and social laws. Ferdinando Galiani wrote on currency; Gaetano Filangieri wrote a ''Scienza della legislazione''. Cesare Beccaria, in his ''On Crimes and Punishments, Trattato dei delitti e delle pene'', made a contribution to the reform of the penal system and promoted the abolition of torture.

The reforming movement sought to throw off the conventional and the artificial, and to return to truth. Apostolo Zeno and Pietro Metastasio had endeavoured to make melodrama and reason compatible. Metastasio gave fresh expression to the affections, a natural turn to the dialogue and some interest to the plot; if he had not fallen into constant unnatural overrefinement and mawkishness, and into frequent anachronisms, he might have been considered the most important writer of ''opera seria'' libretti and the first dramatic reformer of the 18th century.

Carlo Goldoni overcame resistance from the old popular form of comedy, with the masks of ''pantalone'', of the doctor, ''harlequin'', Brighella, etc., and created the comedy of character, following Molière's example. Many of his comedies were written in Venetian language, Venetian. His works include some of Italy's most famous and best-loved plays. Goldoni also wrote under the pen name and title ''Polisseno Fegeio, Pastor Arcade'', which he claimed in his memoirs the "Accademia degli Arcadi, Arcadians of Rome" bestowed on him. One of his best-known works is the comic play ''Servant of Two Masters'', which has been translated and adapted internationally numerous times.

The leading figure of the literary revival of the 18th century was Giuseppe Parini. In a collection of poems he published at twenty-three years of age, under the name of Ripano Eupilino, the poet shows his faculty of taking his scenes from real life, and in his satirical pieces he exhibits a spirit of outspoken opposition to his own times. Improving on the poems of his youth, he showed himself an innovator in his lyrics, rejecting at once Petrarchism, ''Secentismo'' and Arcadia. In the ''Odi'' the satirical note is already heard, but it comes out more strongly in ''Del giorno'', which assumes major social and historical value. As an artist, going straight back to classical forms, he opened the way to the school of Vittorio Alfieri, Ugo Foscolo and Vincenzo Monti. As a work of art, the ''Giorno'' is sometimes a little hard and broken, as a protest against the Arcadian monotony.

The ideas behind the French Revolution of 1789 gave a special direction to Italian literature in the second half of the 18th century. Love of liberty and desire for equality created a literature aimed at national objects, seeking to improve the condition of the country by freeing it from the double yoke of political and religious despotism. The Italians who aspired to political redemption believed it inseparable from an intellectual revival, and thought that this could only be effected by a reunion with ancient classicism. This was a repetition of what had occurred in the first half of the 15th century.

Patriotism and classicism were the two principles that inspired the literature that began with Vittorio Alfieri. He worshipped the Greek and Roman idea of popular liberty in arms against tyranny. He took the subjects of his tragedies from the history of these nations and made his ancient characters talk like revolutionists of his time. The Arcadian school, with its verbosity and triviality, was rejected. His aim was to be brief, concise, strong and bitter, to aim at the sublime as opposed to the lowly and pastoral. He saved literature from Arcadian vacuities, leading it towards a national end, and armed himself with patriotism and classicism. It is to his dramas that Alfieri is chiefly indebted for the high reputation he has attained. The appearance of the tragedies of Alfieri was perhaps the most important literary event that occurred in Italy during the 18th century.

Vincenzo Monti was a patriot too, and wrote the ''Pellegrino apostolico'', the ''Bassvilliana'' and the ''Feroniade''; Napoleon's victories caused him to write the ''Prometeo'' and the ''Musagonia''; in his ''Fanatismo'' and his ''Superstizione'' he attacked the papacy; afterwards he sang the praises of the Austrians. Knowing little Greek, he succeeded in translating the ''Iliad'' in a way remarkable for its Homeric feeling, and in his ''Bassvilliana'' he is on a level with Dante. In him classical poetry seemed to revive in all its florid grandeur.

Patriotism and classicism were the two principles that inspired the literature that began with Vittorio Alfieri. He worshipped the Greek and Roman idea of popular liberty in arms against tyranny. He took the subjects of his tragedies from the history of these nations and made his ancient characters talk like revolutionists of his time. The Arcadian school, with its verbosity and triviality, was rejected. His aim was to be brief, concise, strong and bitter, to aim at the sublime as opposed to the lowly and pastoral. He saved literature from Arcadian vacuities, leading it towards a national end, and armed himself with patriotism and classicism. It is to his dramas that Alfieri is chiefly indebted for the high reputation he has attained. The appearance of the tragedies of Alfieri was perhaps the most important literary event that occurred in Italy during the 18th century.

Vincenzo Monti was a patriot too, and wrote the ''Pellegrino apostolico'', the ''Bassvilliana'' and the ''Feroniade''; Napoleon's victories caused him to write the ''Prometeo'' and the ''Musagonia''; in his ''Fanatismo'' and his ''Superstizione'' he attacked the papacy; afterwards he sang the praises of the Austrians. Knowing little Greek, he succeeded in translating the ''Iliad'' in a way remarkable for its Homeric feeling, and in his ''Bassvilliana'' he is on a level with Dante. In him classical poetry seemed to revive in all its florid grandeur.

Ugo Foscolo was an eager patriot, inspired by classical models. The ''Lettere di Jacopo Ortis'', inspired by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Goethe's ''The Sorrows of Young Werther'', are a love story with a mixture of patriotism; they contain a violent protest against the Treaty of Campo Formio, and an outburst from Foscolo's own heart about an unhappy love-affair of his. His passions were sudden and violent. To one of these passions ''Ortis'' owed its origin, and it is perhaps the best and most sincere of all his writings. The ''Sepolcri'', which is his best poem, was prompted by high feeling, and the mastery of versification shows wonderful art. Among his prose works a high place belongs to his translation of the ''A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy, Sentimental Journey'' of Laurence Sterne, a writer by whom Foscolo was deeply affected. He wrote for English readers some ''Essays on Petrarch'' and on the texts of the ''Decamerone'' and of Dante, which are remarkable for when they were written, and which may have initiated a new type of literary criticism in Italy. The men who made the revolution of 1848 were brought up in his work.

Ugo Foscolo was an eager patriot, inspired by classical models. The ''Lettere di Jacopo Ortis'', inspired by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Goethe's ''The Sorrows of Young Werther'', are a love story with a mixture of patriotism; they contain a violent protest against the Treaty of Campo Formio, and an outburst from Foscolo's own heart about an unhappy love-affair of his. His passions were sudden and violent. To one of these passions ''Ortis'' owed its origin, and it is perhaps the best and most sincere of all his writings. The ''Sepolcri'', which is his best poem, was prompted by high feeling, and the mastery of versification shows wonderful art. Among his prose works a high place belongs to his translation of the ''A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy, Sentimental Journey'' of Laurence Sterne, a writer by whom Foscolo was deeply affected. He wrote for English readers some ''Essays on Petrarch'' and on the texts of the ''Decamerone'' and of Dante, which are remarkable for when they were written, and which may have initiated a new type of literary criticism in Italy. The men who made the revolution of 1848 were brought up in his work.

During the 18th century, Russia was experiencing expansions in military and geographical control, a key facet of the Enlightenment period. This is reflected in the literature of the time period. Satire and the panegyric had influenced the development of Russian literature as seen in the Russian literary figures of the time including Feofan Prokopovich, Kantemir, Derzhavin and Nikolay Karamzin, Karamzin.

During the 18th century, Russia was experiencing expansions in military and geographical control, a key facet of the Enlightenment period. This is reflected in the literature of the time period. Satire and the panegyric had influenced the development of Russian literature as seen in the Russian literary figures of the time including Feofan Prokopovich, Kantemir, Derzhavin and Nikolay Karamzin, Karamzin.

The Romanticism, Romantic era for literature was at its pinnacle during the 19th century and was a period which influenced western literature. The romantic school had as its organ the ''Conciliatore'' established in 1818 at Milan, on the staff of which were Silvio Pellico, Ludovico di Breme, Giovile Scalvini, Tommaso Grossi, Giovanni Berchet, Samuele Biava, and Alessandro Manzoni. All were influenced by the ideas that, especially in Germany, constituted the movement called Romanticism. In Italy the course of literary reform took another direction. Italian writers of the 19th century, including the likes of Giacomo Leopardi, Leopardi and Alessandro Manzoni, detested being grouped into a "category" of writing. Therefore, Italy was home to many isolated literary figures, with no unambiguous meaning for the term "Romanticism" itself. This was explained in the writings of Pietro Borsieri, in which he depicted the term Romanticism as being a literary movement that was self-defined by the writers. Contrastingly, it was noted by writers of the time, including Giuseppe Acerbi, how Italian Romantics were merely mimicking the trends seen in foreign nations in a hasty way which lacked the depth of foreign writers. Authors including Ludovico di Breme, and Giovanni Berchet did classify themselves as Romantics, however they were critiqued by others, including Gina Martegiani, who wrote in her essay "Il Romanticismo Italiano Non Esiste" of 1908 that the authors who considered themselves Romantics only created two-dimensional imitations of the works of German Romanticism, German Romantic authors.

The poetry of the Romantic era of Italy was focused greatly on the motif of nature. Romantic poets drew inspiration from Ancient Greek literature, ancient Greek and Latin poetry and mythology, while poets of this time period also sought to create a sense of unity within the country with their writings. Political disunity was prevalent in 19th-century Italy, reflected in the Unification of Italy, Risorgimento. After the Parthenopean Republic, Neapolitan Revolution of 1799, the term "Risorgimento" was used in the context of a movement of "national redemption" as stated by Antonio Gramsci. The one facet which held Italy together during this time of political disunity was the poetry and writings of the time period, as suggested by Berchet. The desire for freedom and the sense of "national redemption" is reflected heavily in the works of Italian Romantics, including Ugo Foscolo, who wrote the story ''The Last Letters of Jacopo Ortis'', in which a man was forced to commit suicide due to the political persecutions of his country.

The great poet of the age was Giacomo Leopardi. He was also an admirable prose writer. In his ''Operette Morali''—dialogues and discourses marked by a cold and bitter smile at human destinies that freezes the reader—the clearness of style, the simplicity of language and the depth of conception are such that perhaps he is not only the greatest lyrical poet since Dante, but also one of the most perfect writers of prose that Italian literature has had. He is widely seen as one of the most radical and challenging thinkers of the 19th century but routinely compared by Italian critics to his older contemporary Alessandro Manzoni despite expressing "diametrically opposite positions". The strongly lyrical quality of his poetry made him a central figure on the European and international literary and cultural landscape.

The Romanticism, Romantic era for literature was at its pinnacle during the 19th century and was a period which influenced western literature. The romantic school had as its organ the ''Conciliatore'' established in 1818 at Milan, on the staff of which were Silvio Pellico, Ludovico di Breme, Giovile Scalvini, Tommaso Grossi, Giovanni Berchet, Samuele Biava, and Alessandro Manzoni. All were influenced by the ideas that, especially in Germany, constituted the movement called Romanticism. In Italy the course of literary reform took another direction. Italian writers of the 19th century, including the likes of Giacomo Leopardi, Leopardi and Alessandro Manzoni, detested being grouped into a "category" of writing. Therefore, Italy was home to many isolated literary figures, with no unambiguous meaning for the term "Romanticism" itself. This was explained in the writings of Pietro Borsieri, in which he depicted the term Romanticism as being a literary movement that was self-defined by the writers. Contrastingly, it was noted by writers of the time, including Giuseppe Acerbi, how Italian Romantics were merely mimicking the trends seen in foreign nations in a hasty way which lacked the depth of foreign writers. Authors including Ludovico di Breme, and Giovanni Berchet did classify themselves as Romantics, however they were critiqued by others, including Gina Martegiani, who wrote in her essay "Il Romanticismo Italiano Non Esiste" of 1908 that the authors who considered themselves Romantics only created two-dimensional imitations of the works of German Romanticism, German Romantic authors.

The poetry of the Romantic era of Italy was focused greatly on the motif of nature. Romantic poets drew inspiration from Ancient Greek literature, ancient Greek and Latin poetry and mythology, while poets of this time period also sought to create a sense of unity within the country with their writings. Political disunity was prevalent in 19th-century Italy, reflected in the Unification of Italy, Risorgimento. After the Parthenopean Republic, Neapolitan Revolution of 1799, the term "Risorgimento" was used in the context of a movement of "national redemption" as stated by Antonio Gramsci. The one facet which held Italy together during this time of political disunity was the poetry and writings of the time period, as suggested by Berchet. The desire for freedom and the sense of "national redemption" is reflected heavily in the works of Italian Romantics, including Ugo Foscolo, who wrote the story ''The Last Letters of Jacopo Ortis'', in which a man was forced to commit suicide due to the political persecutions of his country.

The great poet of the age was Giacomo Leopardi. He was also an admirable prose writer. In his ''Operette Morali''—dialogues and discourses marked by a cold and bitter smile at human destinies that freezes the reader—the clearness of style, the simplicity of language and the depth of conception are such that perhaps he is not only the greatest lyrical poet since Dante, but also one of the most perfect writers of prose that Italian literature has had. He is widely seen as one of the most radical and challenging thinkers of the 19th century but routinely compared by Italian critics to his older contemporary Alessandro Manzoni despite expressing "diametrically opposite positions". The strongly lyrical quality of his poetry made him a central figure on the European and international literary and cultural landscape.

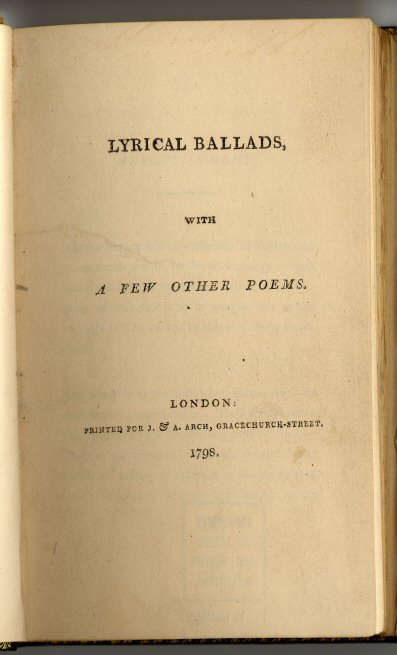

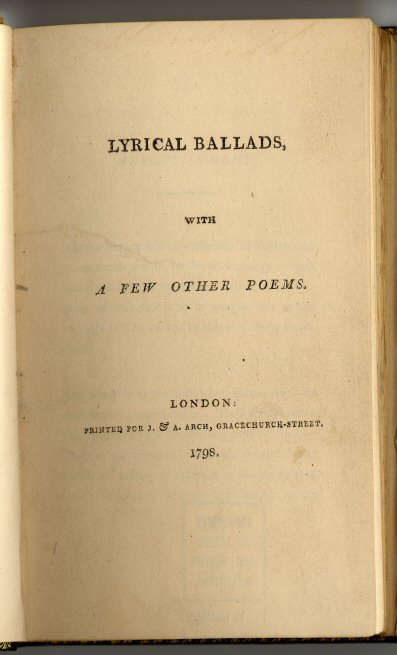

Historical events including the Age of Revolution, European Revolution, within which the French Revolution, French revolution is claimed to be most significant, contributed to the development of 19th-century Romantic literature in English, British Romanticism. These revolutions birthed a new genre of authors and poets who used their literature to convey their distaste for authority. This is seen in the works of poet and artist William Blake, who used primarily philosophical and biblical themes in his poetry, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth, also known as the "Lake Poets", whose literature including the ''Lyrical Ballads'' is claimed to have "marked the beginning of the Romantic Movement".

There was known to be two waves of British Romantic authors; Coleridge and Wordsworth were grouped into the first wave, while a more radical and "aggressive" second wave of authors included the likes of Lord Byron, George Gordon Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley. Due to the adamant aggression of Byron in his poetic works which advocated for an anti-violence revolution and world in which equality existed, a form of fictional character was born named the "Byronic hero", who is known to be rebellious in character. The Byronic hero "pervades much of his work" and Byron is considered a reflection of the character he created.

Greek and Roman mythology was prevalent in the works of British Romantic poets including Byron, John Keats, Keats and Percy Bysshe Shelley, Shelley. However, there were poets who rejected the notion of mythological inspiration, including Coleridge, who preferred to take inspiration from the Bible to produce significantly religious-inspired works.

British 19th-century Romanticism developed literature which focused on the "self-organisation of living beings, their growth and adaption into their environments and the creative spark that inspired the physical system to perform complex functions". There are observed close ties between medicine, a concept which was experiencing innovation during the 19th century, and Romantic English literature. British Romanticism also had influences from 13th-/16th-century Italian art as a consequence of British artists who resided in Italy during the time of Bonaparte's invasion dealing paintings to London clients from Middle Ages, medieval to the High Renaissance Italian periods. The exposure to these artworks influenced

Historical events including the Age of Revolution, European Revolution, within which the French Revolution, French revolution is claimed to be most significant, contributed to the development of 19th-century Romantic literature in English, British Romanticism. These revolutions birthed a new genre of authors and poets who used their literature to convey their distaste for authority. This is seen in the works of poet and artist William Blake, who used primarily philosophical and biblical themes in his poetry, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth, also known as the "Lake Poets", whose literature including the ''Lyrical Ballads'' is claimed to have "marked the beginning of the Romantic Movement".

There was known to be two waves of British Romantic authors; Coleridge and Wordsworth were grouped into the first wave, while a more radical and "aggressive" second wave of authors included the likes of Lord Byron, George Gordon Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley. Due to the adamant aggression of Byron in his poetic works which advocated for an anti-violence revolution and world in which equality existed, a form of fictional character was born named the "Byronic hero", who is known to be rebellious in character. The Byronic hero "pervades much of his work" and Byron is considered a reflection of the character he created.

Greek and Roman mythology was prevalent in the works of British Romantic poets including Byron, John Keats, Keats and Percy Bysshe Shelley, Shelley. However, there were poets who rejected the notion of mythological inspiration, including Coleridge, who preferred to take inspiration from the Bible to produce significantly religious-inspired works.

British 19th-century Romanticism developed literature which focused on the "self-organisation of living beings, their growth and adaption into their environments and the creative spark that inspired the physical system to perform complex functions". There are observed close ties between medicine, a concept which was experiencing innovation during the 19th century, and Romantic English literature. British Romanticism also had influences from 13th-/16th-century Italian art as a consequence of British artists who resided in Italy during the time of Bonaparte's invasion dealing paintings to London clients from Middle Ages, medieval to the High Renaissance Italian periods. The exposure to these artworks influenced

Important early-20th century writers include Italo Svevo, the author of ''Zeno's Conscience, La coscienza di Zeno'' (1923), and Luigi Pirandello (winner of the 1934 Nobel Prize in Literature), who explored the shifting nature of reality in his prose fiction and such plays as ''Sei personaggi in cerca d'autore'' (''Six Characters in Search of an Author'', 1921).

Federigo Tozzi was a great novelist, critically appreciated only in recent years, and considered one of the forerunners of existentialism in the European novel.

Grazia Deledda was a Sardinian writer who focused on the life, customs, and traditions of the Sardinian people in her works.Migiel, Marilyn. "Grazia Deledda." Italian Women Writers: A Bio-bibliographical Sourcebook. By Rinaldina Russell. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1994. 111-117. Print. In 1926 she won the Nobel Prize for literature, becoming Italy's first and only woman recipient.

Sibilla Aleramo published her first novel, Una Donna (A Woman) in 1906. Today the novel is widely acknowledged as Italy's premier feminist novel. Her writing mixes together autobiographical and fictional elements.

Pitigrilli was the pseudonym of Dino Segre who published his most famous novel (cocaine) in 1921. Due to his portrayal of drug use and sex, the Catholic Church listed it as a "forbidden book". It has been translated into numerous languages, reprinted in new editions, and has become a classic.

Maria Messina was a Sicilian writer who focused heavily on Sicilian culture with a dominant theme being the isolation and oppression of young Sicilian women.Lombardo, Maria Nina. "Maria Messina." Italian Women Writers: A Bio-bibliographical Sourcebook. By Rinaldina Russell. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1994. 253-259. Print. She achieved modest recognition during her life including receiving the Medaglia D'oro Prize for "La Mérica".

Anna Bantiis most well known for her short story Il ''Coraggio Delle Donne'' (''The Courage of Women'') which was published in 1940. Her autobiographical work, Un Grido Lacerante, was published in 1981 and won the Antonio Feltrinelli prize. As well as being a successful author, Banti is recognized as a literary, cinematic, and art critic.

Elsa Morante began writing at an early age. One of the central themes in Morante's works is narcissism. She also uses love as a metaphor in her works, saying that love can be passion and obsession and can lead to despair and destruction. She won the Premio Viareggio award in 1948.

Alba de Céspedes was a Cuban-Italian writer from Rome.Nerenberg, Ellen. "Alba De Céspedes." Italian Women Writers: A Bio-bibliographical Sourcebook. By Rinaldina Russell. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1994. 104-110. Print. She was an anti-Fascist and was involved in the Italian Resistance. Her work was greatly influenced by the history and culture that developed around World War II. Although her books were bestsellers, Alba has been overlooked in recent studies of Italian women writers.

Poetry was represented by the Crepuscolari and the Futurism, Futurists; the foremost member of the latter group was Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. Leading Modernism, Modernist poets from later in the century include Salvatore Quasimodo (winner of the 1959 Nobel Prize in Literature), Giuseppe Ungaretti, Umberto Saba, who won fame for his collection of poems ''Il canzoniere'', and Eugenio Montale (winner of the 1975 Nobel Prize in Literature). They were described by critics as "Hermeticism (poetry), hermeticists".

Neorealism (art), Neorealism was a movement that developed rapidly between the 1940s and the 1950s. Although its foundations were laid in the 1920s, it flourished only after the fall of Fascism in Italy, as this type of literature was not welcomed by Fascist authorities because of its social criticism and partially because some of the "new realist" authors could hold Anti-Fascist views. For example, Alberto Moravia, one of the leading writers of the movement, had trouble with finding a publisher for his novel which brought him fame, ''Gli indifferenti'' (1929), and after he published it, he was "driven into hiding"; Carlo Bernari's ''Tre operai'' (1934, ''Three Workers'') was unofficially banned personally by Mussolini who saw "communism" in the novel; Ignazio Silone published ''Fontamara'' (1933) in exile; Elio Vittorini was put in prison after publishing ''Conversations in Sicily, Conversazione in Sicilia'' (1941). The movement was profoundly affected by the translations of socially conscious U.S. and English writers during the 1930s and 1940s, namely Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, John Steinbeck, John Dos Passos and the others; the translators of their works, Vittorini and Cesare Pavese, would later become acclaimed novelists of the movement. After the war, the movement began rapidly developing and took the label "Neorealism"; Marxism and the experiences of the war became sources of inspiration for the postwar authors. Moravia wrote the novels ''The Conformist'' (1951) and ''Two Women (novel), La Ciociara'' (1957), while ''The Moon and the Bonfires'' (1949) became Pavese's most recognized work; Primo Levi documented his experiences in Auschwitz in ''If This Is a Man'' (1947); among the other writers were Carlo Levi, who reflected the experience of political exile in southern Italy in ''Christ Stopped at Eboli'' (1951); Curzio Malaparte, author of ''Kaputt (novel), Kaputt'' (1944) and ''The Skin (novel), The Skin'' (1949), novels dealing with the war on the Eastern Front (World War II), Eastern Front and in Naples; Pier Paolo Pasolini, also a poet and a film director, who described the life of the Roman ''lumpenproletariat'' in ''Ragazzi di vita, The Ragazzi'' (1955); and Corrado Alvaro.

Dino Buzzati wrote fantastic and allegorical fiction that critics have compared to Franz Kafka, Kafka and Samuel Beckett, Beckett. Italo Calvino also ventured into fantasy in the trilogy ''I nostri antenati'' (''Our Ancestors'', 1952–1959) and post-modernism in the novel ''Se una notte d'inverno un viaggiatore...'' (''If on a Winter's Night a Traveler, If on a Winter's Night a Traveller'', 1979).

Carlo Emilio Gadda was the author of the experimental ''Quer pasticciaccio brutto de via Merulana'' (1957).

Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa wrote only one novel, ''Il Gattopardo'' (''The Leopard'', 1958), but it is one of the most famous in Italian literature; it deals with the life of a Sicily, Sicilian nobleman in the 19th century. Leonardo Sciascia came to public attention with his novel ''The Day of the Owl, Il giorno della civetta'' (''The Day of the Owl'', 1961), exposing the extent of Sicilian Mafia, Mafia corruption in modern Sicilian society. More recently, Umberto Eco became internationally successful with the Medieval detective story ''Il nome della rosa'' (''The Name of the Rose'', 1980).

Dacia Maraini is one of the most successful contemporary Italian women writers. Her novels focus on the condition of women in Italy and in some works she speaks to the changes women can make for themselves and society.

Aldo Busi is also one of the most important Italian contemporary writers. His extensive production of novels, essays, travel books and manuals provides a detailed account of modern society, especially the Italian one. He is also well known as a refined translator.

Important early-20th century writers include Italo Svevo, the author of ''Zeno's Conscience, La coscienza di Zeno'' (1923), and Luigi Pirandello (winner of the 1934 Nobel Prize in Literature), who explored the shifting nature of reality in his prose fiction and such plays as ''Sei personaggi in cerca d'autore'' (''Six Characters in Search of an Author'', 1921).

Federigo Tozzi was a great novelist, critically appreciated only in recent years, and considered one of the forerunners of existentialism in the European novel.

Grazia Deledda was a Sardinian writer who focused on the life, customs, and traditions of the Sardinian people in her works.Migiel, Marilyn. "Grazia Deledda." Italian Women Writers: A Bio-bibliographical Sourcebook. By Rinaldina Russell. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1994. 111-117. Print. In 1926 she won the Nobel Prize for literature, becoming Italy's first and only woman recipient.

Sibilla Aleramo published her first novel, Una Donna (A Woman) in 1906. Today the novel is widely acknowledged as Italy's premier feminist novel. Her writing mixes together autobiographical and fictional elements.

Pitigrilli was the pseudonym of Dino Segre who published his most famous novel (cocaine) in 1921. Due to his portrayal of drug use and sex, the Catholic Church listed it as a "forbidden book". It has been translated into numerous languages, reprinted in new editions, and has become a classic.

Maria Messina was a Sicilian writer who focused heavily on Sicilian culture with a dominant theme being the isolation and oppression of young Sicilian women.Lombardo, Maria Nina. "Maria Messina." Italian Women Writers: A Bio-bibliographical Sourcebook. By Rinaldina Russell. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1994. 253-259. Print. She achieved modest recognition during her life including receiving the Medaglia D'oro Prize for "La Mérica".

Anna Bantiis most well known for her short story Il ''Coraggio Delle Donne'' (''The Courage of Women'') which was published in 1940. Her autobiographical work, Un Grido Lacerante, was published in 1981 and won the Antonio Feltrinelli prize. As well as being a successful author, Banti is recognized as a literary, cinematic, and art critic.

Elsa Morante began writing at an early age. One of the central themes in Morante's works is narcissism. She also uses love as a metaphor in her works, saying that love can be passion and obsession and can lead to despair and destruction. She won the Premio Viareggio award in 1948.

Alba de Céspedes was a Cuban-Italian writer from Rome.Nerenberg, Ellen. "Alba De Céspedes." Italian Women Writers: A Bio-bibliographical Sourcebook. By Rinaldina Russell. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1994. 104-110. Print. She was an anti-Fascist and was involved in the Italian Resistance. Her work was greatly influenced by the history and culture that developed around World War II. Although her books were bestsellers, Alba has been overlooked in recent studies of Italian women writers.

Poetry was represented by the Crepuscolari and the Futurism, Futurists; the foremost member of the latter group was Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. Leading Modernism, Modernist poets from later in the century include Salvatore Quasimodo (winner of the 1959 Nobel Prize in Literature), Giuseppe Ungaretti, Umberto Saba, who won fame for his collection of poems ''Il canzoniere'', and Eugenio Montale (winner of the 1975 Nobel Prize in Literature). They were described by critics as "Hermeticism (poetry), hermeticists".

Neorealism (art), Neorealism was a movement that developed rapidly between the 1940s and the 1950s. Although its foundations were laid in the 1920s, it flourished only after the fall of Fascism in Italy, as this type of literature was not welcomed by Fascist authorities because of its social criticism and partially because some of the "new realist" authors could hold Anti-Fascist views. For example, Alberto Moravia, one of the leading writers of the movement, had trouble with finding a publisher for his novel which brought him fame, ''Gli indifferenti'' (1929), and after he published it, he was "driven into hiding"; Carlo Bernari's ''Tre operai'' (1934, ''Three Workers'') was unofficially banned personally by Mussolini who saw "communism" in the novel; Ignazio Silone published ''Fontamara'' (1933) in exile; Elio Vittorini was put in prison after publishing ''Conversations in Sicily, Conversazione in Sicilia'' (1941). The movement was profoundly affected by the translations of socially conscious U.S. and English writers during the 1930s and 1940s, namely Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, John Steinbeck, John Dos Passos and the others; the translators of their works, Vittorini and Cesare Pavese, would later become acclaimed novelists of the movement. After the war, the movement began rapidly developing and took the label "Neorealism"; Marxism and the experiences of the war became sources of inspiration for the postwar authors. Moravia wrote the novels ''The Conformist'' (1951) and ''Two Women (novel), La Ciociara'' (1957), while ''The Moon and the Bonfires'' (1949) became Pavese's most recognized work; Primo Levi documented his experiences in Auschwitz in ''If This Is a Man'' (1947); among the other writers were Carlo Levi, who reflected the experience of political exile in southern Italy in ''Christ Stopped at Eboli'' (1951); Curzio Malaparte, author of ''Kaputt (novel), Kaputt'' (1944) and ''The Skin (novel), The Skin'' (1949), novels dealing with the war on the Eastern Front (World War II), Eastern Front and in Naples; Pier Paolo Pasolini, also a poet and a film director, who described the life of the Roman ''lumpenproletariat'' in ''Ragazzi di vita, The Ragazzi'' (1955); and Corrado Alvaro.

Dino Buzzati wrote fantastic and allegorical fiction that critics have compared to Franz Kafka, Kafka and Samuel Beckett, Beckett. Italo Calvino also ventured into fantasy in the trilogy ''I nostri antenati'' (''Our Ancestors'', 1952–1959) and post-modernism in the novel ''Se una notte d'inverno un viaggiatore...'' (''If on a Winter's Night a Traveler, If on a Winter's Night a Traveller'', 1979).

Carlo Emilio Gadda was the author of the experimental ''Quer pasticciaccio brutto de via Merulana'' (1957).

Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa wrote only one novel, ''Il Gattopardo'' (''The Leopard'', 1958), but it is one of the most famous in Italian literature; it deals with the life of a Sicily, Sicilian nobleman in the 19th century. Leonardo Sciascia came to public attention with his novel ''The Day of the Owl, Il giorno della civetta'' (''The Day of the Owl'', 1961), exposing the extent of Sicilian Mafia, Mafia corruption in modern Sicilian society. More recently, Umberto Eco became internationally successful with the Medieval detective story ''Il nome della rosa'' (''The Name of the Rose'', 1980).

Dacia Maraini is one of the most successful contemporary Italian women writers. Her novels focus on the condition of women in Italy and in some works she speaks to the changes women can make for themselves and society.

Aldo Busi is also one of the most important Italian contemporary writers. His extensive production of novels, essays, travel books and manuals provides a detailed account of modern society, especially the Italian one. He is also well known as a refined translator.

Italy has a long history of children's literature. In 1634, the ''Pentamerone'' from Italy became the first major published collection of European folk tales. The ''Pentamerone'' contained the first literary European version of the story of Cinderella. The author, Giambattista Basile, created collections of fairy tales that include the oldest recorded forms of many well-known European fairy tales. In the 1550s, Giovanni Francesco Straparola released ''The Facetious Nights of Straparola''. Called the first European storybook to contain fairy tales, it eventually had 75 separate stories, albeit intended for an adult audience. Giulio Cesare Croce also borrowed from stories children enjoyed for his books.

In 1883, Carlo Collodi wrote ''The Adventures of Pinocchio'', the first Italian fantasy novel. In the same year, Emilio Salgari, the man who would become "the adventure writer par excellence for the young in Italy"Lawson Lucas, A. (1995) "The Archetypal Adventures of Emilio Salgari: A Panorama of his Universe and Cultural Connections New Comparison", ''A Journal of Comparative and General Literary Studies'', Number 20 Autumn published for the first time his ''Sandokan''. In the 20th century, Italian children's literature was represented by such writers as Gianni Rodari, author of ''Il romanzo di Cipollino'', and Nicoletta Costa, creator of Julian Rabbit and Olga the Cloud.

Italy has a long history of children's literature. In 1634, the ''Pentamerone'' from Italy became the first major published collection of European folk tales. The ''Pentamerone'' contained the first literary European version of the story of Cinderella. The author, Giambattista Basile, created collections of fairy tales that include the oldest recorded forms of many well-known European fairy tales. In the 1550s, Giovanni Francesco Straparola released ''The Facetious Nights of Straparola''. Called the first European storybook to contain fairy tales, it eventually had 75 separate stories, albeit intended for an adult audience. Giulio Cesare Croce also borrowed from stories children enjoyed for his books.

In 1883, Carlo Collodi wrote ''The Adventures of Pinocchio'', the first Italian fantasy novel. In the same year, Emilio Salgari, the man who would become "the adventure writer par excellence for the young in Italy"Lawson Lucas, A. (1995) "The Archetypal Adventures of Emilio Salgari: A Panorama of his Universe and Cultural Connections New Comparison", ''A Journal of Comparative and General Literary Studies'', Number 20 Autumn published for the first time his ''Sandokan''. In the 20th century, Italian children's literature was represented by such writers as Gianni Rodari, author of ''Il romanzo di Cipollino'', and Nicoletta Costa, creator of Julian Rabbit and Olga the Cloud.

literature

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially novels, Play (theatre), plays, and poetry, poems. It includes both print and Electroni ...

written in the context of Western culture

Western culture, also known as Western civilization, European civilization, Occidental culture, Western society, or simply the West, refers to the Cultural heritage, internally diverse culture of the Western world. The term "Western" encompas ...

in the languages of Europe

There are over 250 languages indigenous to Europe, and most belong to the Indo-European language family. Out of a demographics of Europe, total European population of 744 million as of 2018, some 94% are native speakers of an Indo-European lang ...

, and is shaped by the periods in which they were conceived, with each period containing prominent western authors, poets, and pieces of literature.

The best of Western literature is considered to be the Western canon

The Western canon is the embodiment of High culture, high-culture literature, music, philosophy, and works of art that are highly cherished across the Western culture, Western world, such works having achieved the status of classics.

Recent ...

. The list of works in the Western canon varies according to the critic's opinions on Western culture

Western culture, also known as Western civilization, European civilization, Occidental culture, Western society, or simply the West, refers to the Cultural heritage, internally diverse culture of the Western world. The term "Western" encompas ...

and the relative importance of its defining characteristics. Different literary periods held great influence on the literature of Western and European countries, with movements and political changes impacting the prose and poetry of the period. The 16th Century is known for the creation of Renaissance literature, while the 17th century was influenced by both Baroque and Jacobean forms. The 18th century progressed into a period known as the Enlightenment Era for many western countries. This period of military and political advancement influenced the style of literature created by French, Russian and Spanish literary figures. The 19th century was known as the Romantic era, in which the style of writing was influenced by the political issues of the century, and differed from the previous classicist form.

Western literature includes written works in many languages:

* Albanian literature

Albanian literature stretches back to the Middle Ages and comprises those literary texts and works written in Albanian language, Albanian. It may also refer to literature written by Albanians in Albania, Kosovo and the Albanian diaspora particul ...

* Argentine literature

Argentine literature, i.e. the set of literary works produced by writers who originated from Argentina, is one of the most prolific, relevant and influential in the whole Spanish speaking world, with renowned writers such as Jorge Luis Borges, Ju ...

* Armenian literature

Armenian literature (), produced in the Armenian language, has existed in written form since the 5th century CE, when the Armenian alphabet was invented by Mesrop Mashtots and the first original works of Armenian literature were composed. Prior ...

* American literature

American literature is literature written or produced in the United States of America and in the British colonies that preceded it. The American literary tradition is part of the broader tradition of English-language literature, but also ...

* Aromanian literature

Aromanian literature ( or ) is literature written in the Aromanian language. The first authors to write in Aromanian appeared during the second half of the 18th century in the metropolis of Moscopole ( Theodore Kavalliotis, Daniel Moscopolites ...

* Australian literature

Australian literature is the literature, written or literary work produced in the area or by the people of the Australia, Commonwealth of Australia and its preceding colonies. During its early Western culture, Western history, Australia was a ...

* Austrian literature

Austrian literature () is mostly written in German language, German, and is closely connected with German literature.

Origin and background

From the 19th century onward, Austria was the home of novelists and short-story writers, including Ada ...

* Basque literature

Although the first instances of coherent Basque language, Basque phrases and sentences go as far back as the Glosas Emilianenses, San Millán glosses of around 950, the large-scale damage done by periods of great instability and warfare, such as ...

* Belarusian literature