Athens 1896 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The 1896 Summer Olympics (), officially known as the Games of the I Olympiad () and commonly known as Athens 1896 (), were the first international

With the prospect of reviving the Olympic games very much in doubt, Coubertin and Vikelas commenced a campaign to keep the Olympic movement alive. Their efforts culminated on 7 January 1895 when Vikelas announced that crown prince Constantine would assume the presidency of the organising committee. His first responsibility was to raise the funds necessary to host the Games. He relied on the patriotism of the Greek people to motivate them to provide the required finances. Constantine's enthusiasm sparked a wave of contributions from the Greek public. This grassroots effort raised 330,000 drachmas. A special set of postage stamps was commissioned; the sale of which raised 400,000 drachmas. Ticket sales added 200,000 drachmas. At the request of Constantine, businessman

With the prospect of reviving the Olympic games very much in doubt, Coubertin and Vikelas commenced a campaign to keep the Olympic movement alive. Their efforts culminated on 7 January 1895 when Vikelas announced that crown prince Constantine would assume the presidency of the organising committee. His first responsibility was to raise the funds necessary to host the Games. He relied on the patriotism of the Greek people to motivate them to provide the required finances. Constantine's enthusiasm sparked a wave of contributions from the Greek public. This grassroots effort raised 330,000 drachmas. A special set of postage stamps was commissioned; the sale of which raised 400,000 drachmas. Ticket sales added 200,000 drachmas. At the request of Constantine, businessman

Seven venues were used for the 1896 Summer Olympics.

Seven venues were used for the 1896 Summer Olympics.

On

On

International Olympic Committee Afterwards, nine bands and 150 choir singers performed an

A regatta of sailing boats was on the program of the Games of the First Olympiad for 31 March 1896 (Julian calendar). However this event had to be given up.

The official English report states:

The German version states:

Rowing races were scheduled for the next day, 1 April 1896 (Julian); however, poor weather forced their cancellation.

The official English report states:

The German rower, Berthold Küttner, wrote several articles about the 1896 Games that were published in his Berlin rowing club's magazine in 1936 and reprinted in the

A regatta of sailing boats was on the program of the Games of the First Olympiad for 31 March 1896 (Julian calendar). However this event had to be given up.

The official English report states:

The German version states:

Rowing races were scheduled for the next day, 1 April 1896 (Julian); however, poor weather forced their cancellation.

The official English report states:

The German rower, Berthold Küttner, wrote several articles about the 1896 Games that were published in his Berlin rowing club's magazine in 1936 and reprinted in the

The swimming competition was held in the open sea because the organizers had refused to spend the money necessary for a specially constructed stadium. Nearly 20,000 spectators lined the

The swimming competition was held in the open sea because the organizers had refused to spend the money necessary for a specially constructed stadium. Nearly 20,000 spectators lined the

The sport of weightlifting was still young in 1896, and the rules differed from those in use today. Competitions were held outdoors, in the infield of the main stadium, and there were no weight limits. The first event was held in a style now known as the "

The sport of weightlifting was still young in 1896, and the rules differed from those in use today. Competitions were held outdoors, in the infield of the main stadium, and there were no weight limits. The first event was held in a style now known as the "

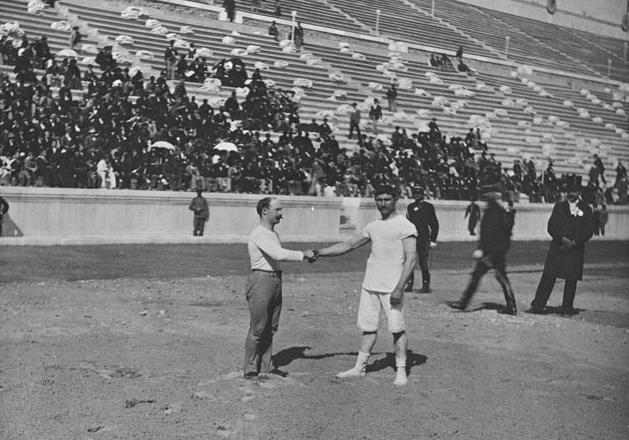

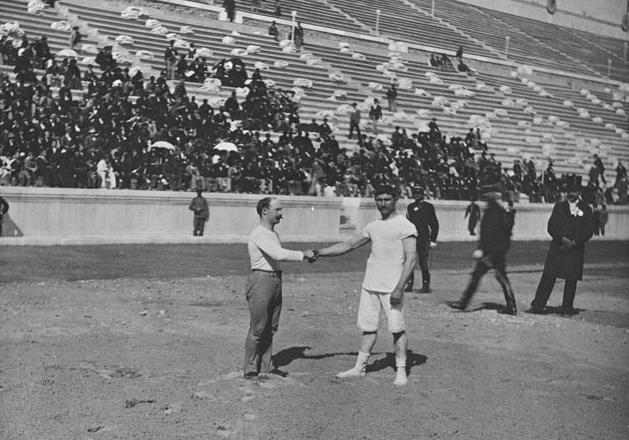

No weight classes existed for the wrestling competition, held in the Panathenaic Stadium, which meant that there would only be one winner among competitors of all sizes. The rules used were similar to modern

No weight classes existed for the wrestling competition, held in the Panathenaic Stadium, which meant that there would only be one winner among competitors of all sizes. The rules used were similar to modern

On the morning of Sunday 12 April (or 31 March, according to the Julian calendar then used in Greece), King George organised a banquet for officials and athletes (even though some competitions had not yet been held). During his speech, he made clear that, as far as he was concerned, the Olympics should be held in Athens permanently. The official closing ceremony was held the following Wednesday after being postponed from Tuesday due to rain. Again, the royal family attended the ceremony, which was opened by the

On the morning of Sunday 12 April (or 31 March, according to the Julian calendar then used in Greece), King George organised a banquet for officials and athletes (even though some competitions had not yet been held). During his speech, he made clear that, as far as he was concerned, the Olympics should be held in Athens permanently. The official closing ceremony was held the following Wednesday after being postponed from Tuesday due to rain. Again, the royal family attended the ceremony, which was opened by the

The concept of national teams was not a major part of the Olympic movement until the

The concept of national teams was not a major part of the Olympic movement until the

1896 Olympic Games Programme – UK Parliament Living Heritage

{{Authority control 1896 Summer Olympics, 19th century in Athens 1896 in Greek sport History of Greece (1863–1909) Olympic Games in Greece Sports competitions in Athens Summer Olympics by year O

Olympic Games

The modern Olympic Games (Olympics; ) are the world's preeminent international Olympic sports, sporting events. They feature summer and winter sports competitions in which thousands of athletes from around the world participate in a Multi-s ...

held in modern history

The modern era or the modern period is considered the current historical period of human history. It was originally applied to the history of Europe and Western history for events that came after the Middle Ages, often from around the year 1500, ...

. Organised by the International Olympic Committee

The International Olympic Committee (IOC; , CIO) is the international, non-governmental, sports governing body of the modern Olympic Games. Founded in 1894 by Pierre de Coubertin and Demetrios Vikelas, it is based i ...

(IOC), which had been created by French aristocrat Pierre de Coubertin

Charles Pierre de Frédy, Baron de Coubertin (; born Pierre de Frédy; 1 January 1863 – 2 September 1937), also known as Pierre de Coubertin and Baron de Coubertin, was a French educator and historian, co-founder of the International Olympic ...

, the event was held in Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

, Greece, from 6 to 15 April 1896.

Fourteen nations (according to the IOC, though the number is subject to interpretation) and 241 athletes (all males; this number is also disputed) took part in the games. Participants were all European or living in Europe, with the exception of the United States team, and over 65% of the competing athletes were Greek. Winners were given a silver medal

A silver medal, in sports and other similar areas involving competition, is a medal made of, or plated with, silver awarded to the second-place finisher, or runner-up, of contests or competitions such as the Olympic Games, Commonwealth Games, ...

, while runners-up received a copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

medal. Retroactively, the IOC has designated the top three finishers in each event as gold

Gold is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol Au (from Latin ) and atomic number 79. In its pure form, it is a brightness, bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile metal. Chemically, gold is a transition metal ...

, silver, and bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals (such as phosphorus) or metalloid ...

medalists. Ten of the 14 participating nations earned medals. On April 6, 1896, American James Connolly

James Connolly (; 5 June 1868 – 12 May 1916) was a Scottish people, Scottish-born Irish republicanism, Irish republican, socialist, and trade union leader, executed for his part in the Easter Rising, 1916 Easter Rising against British rule i ...

became the first Olympic medalist in more than 1,500 years, competing in the triple jump

The triple jump, sometimes referred to as the hop, step and jump or the hop, skip and jump, is a track and field event, similar to long jump. As a group, the two events are referred to as the "horizontal jumps". The competitor runs down the tr ...

. The United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

won the most gold medals, 11, while host nation Greece won the most medals overall, 47. The highlight for the Greeks was the marathon

The marathon is a long-distance foot race with a distance of kilometres ( 26 mi 385 yd), usually run as a road race, but the distance can be covered on trail routes. The marathon can be completed by running or with a run/walk strategy. There ...

victory by their compatriot Spyridon Louis

Spyridon Louis ( , sometimes transliterated ''Spiridon Loues''; 12 January 1873 – 26 March 1940), commonly known as Spyros Louis (Σπύρος Λούης), was a Greek water carrier who won the first modern-day Olympic marathon at the 1896 ...

. The most successful competitor was German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

wrestler

Wrestling is a martial art, combat sport, and form of entertainment that involves grappling with an opponent and striving to obtain a position of advantage through different throws or techniques, within a given ruleset. Wrestling involves diffe ...

and gymnast

Gymnastics is a group of sport that includes physical exercises requiring balance, strength, flexibility, agility, coordination, artistry and endurance. The movements involved in gymnastics contribute to the development of the arms, legs, sh ...

Carl Schuhmann

Carl August Berthold Schuhmann (12 May 1869 – 24 March 1946) was a German athlete who won four Olympic titles in gymnastics and wrestling at the 1896 Summer Olympics in Athens, becoming the most successful athlete at the inaugural Olympics ...

, who won four events.

Athens had been unanimously chosen to stage the inaugural modern Games during a congress organised by Coubertin in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

on 23 June 1894 (during which the IOC was also created) because Greece was the birthplace of the Ancient Olympic Games

The ancient Olympic Games (, ''ta Olympia''.), or the ancient Olympics, were a series of Athletics (sport), athletic competitions among representatives of polis, city-states and one of the Panhellenic Games of ancient Greece. They were held at ...

. The main venue was the Panathenaic Stadium

The Panathenaic Stadium (, ) or ''Kallimarmaro'' ( , ) is a multi-purpose stadium in Athens, Greece. One of the main historic attractions of Athens, it is the only stadium in the world built entirely of marble.

A stadium was built on the site o ...

, where athletics and wrestling took place; other venues included the Neo Phaliron Velodrome

The Neo Phaliron Velodrome (New Phaleron) was a velodrome and sports arena in the Neo Faliro District of Piraeus, Greece, used for the cycling sport, cycling events at the 1896 Summer Olympics held in Athens.Quote from page 194/241: ''The bicycle ...

for cycling

Cycling, also known as bicycling or biking, is the activity of riding a bicycle or other types of pedal-driven human-powered vehicles such as balance bikes, unicycles, tricycles, and quadricycles. Cycling is practised around the world fo ...

and the Zappeion

The Zappeion (, ) is a large, palatial building next to the National Gardens of Athens in the heart of Athens, Greece. It is generally used for meetings and ceremonies, both official and private and is one of the city's most renowned modern land ...

for fencing

Fencing is a combat sport that features sword fighting. It consists of three primary disciplines: Foil (fencing), foil, épée, and Sabre (fencing), sabre (also spelled ''saber''), each with its own blade and set of rules. Most competitive fe ...

. The opening ceremony was held in the Panathenaic Stadium on 6 April, during which most of the competing athletes were aligned on the infield, grouped by nation. After a speech by the president of the organising committee, Crown Prince Constantine, his father officially opened the Games. Afterwards, nine bands and 150 choir singers performed an Olympic Hymn

The Olympic Hymn (, ), also known as the Olympic Anthem, is a choral cantata by opera composer Spyridon Samaras (1861–1917), with Demotic Greek lyrics by Greek poet Kostis Palamas. Both poet and composer were the choice of the Greek Deme ...

, composed by Spyridon Samaras

Spyridon-Filiskos Samaras () (29 November 1861 - 7 April 1917) was a Greek composer particularly admired for his operas. His compositions were praised worldwide during his lifetime and he is arguably the most important composer of the Ionian Scho ...

and written by Kostis Palamas

Kostis Palamas (; ; – 27 February 1943) was a Greek poet who wrote the words to the Olympic Hymn. He was a central figure of the Greek literary generation of the 1880s and one of the cofounders of the so-called New Athenian School (or Pala ...

.

The 1896 Olympics were regarded as a great success. The Games had the largest international participation of any sporting event to that date. The Panathenaic Stadium overflowed with the largest crowd ever to watch a sporting event. After the Games, Coubertin and the IOC were petitioned by several prominent figures, including Greece's King George King George may refer to:

People Monarchs

;Bohemia

*George of Bohemia (1420-1471, r. 1458-1471), king of Bohemia

;Duala people of Cameroon

* George (Duala king) (late 18th century), king of the Duala people

;Georgia

*George I of Georgia (998 or ...

and some of the American competitors in Athens, to hold all the following Games in Athens. However, the 1900 Summer Olympics

The 1900 Summer Olympics (), today officially known as the Games of the II Olympiad () and also known as Paris 1900, were an international multi-sport event that took place in Paris, France, from 14 May to 28 October 1900. No opening or closin ...

were already planned for Paris, and, with the exception of the Intercalated Games of 1906, the Olympics did not return to Greece until the 2004 Summer Olympics

The 2004 Summer Olympics (), officially the Games of the XXVIII Olympiad (), and officially branded as Athens 2004 (), were an international multi-sport event held from 13 to 29 August 2004 in Athens, Greece.

The Games saw 10,625 athletes ...

, 108 years later.

Reviving the Games

During the 19th century, several small-scale sports festivals across Europe were named after theAncient Olympic Games

The ancient Olympic Games (, ''ta Olympia''.), or the ancient Olympics, were a series of Athletics (sport), athletic competitions among representatives of polis, city-states and one of the Panhellenic Games of ancient Greece. They were held at ...

. The 1870 Olympics

The modern Olympic Games (Olympics; ) are the world's preeminent international sporting events. They feature summer and winter sports competitions in which thousands of athletes from around the world participate in a variety of competit ...

at the Panathenaic stadium, which had been refurbished for the occasion, had an audience of 30,000 people. Pierre de Coubertin

Charles Pierre de Frédy, Baron de Coubertin (; born Pierre de Frédy; 1 January 1863 – 2 September 1937), also known as Pierre de Coubertin and Baron de Coubertin, was a French educator and historian, co-founder of the International Olympic ...

, a French pedagogue

Pedagogy (), most commonly understood as the approach to teaching, is the theory and practice of learning, and how this process influences, and is influenced by, the social, political, and psychological development of learners. Pedagogy, taken ...

and historian, adopted William Penny Brookes

William Penny Brookes (13 August 1809 – 11 December 1895) was an English surgeon, magistrate, botanist, and educationalist especially known for founding the Wenlock Olympian Games, inspiring the modern Olympic Games, and for his promotion of ...

' idea to establish a multi-national and multi-sport event

A multi-sport event is an organized sporting event, often held over multiple days, featuring competition in many different sports among organized teams of athletes from (mostly) nation-states. The first major, modern, multi-sport event of intern ...

—the ancient games only allowed male athletes of Greek origin to participate. In 1890, Coubertin wrote an article in ''La Revue Athlétique'', which espoused the importance of Much Wenlock

Much Wenlock is a market town and Civil parishes in England, parish in Shropshire, England; it is situated on the A458 road between Shrewsbury and Bridgnorth. Nearby, to the north-east, is the Ironbridge Gorge and Telford. The civil parish incl ...

, a rural market town in the English county of Shropshire

Shropshire (; abbreviated SalopAlso used officially as the name of the county from 1974–1980. The demonym for inhabitants of the county "Salopian" derives from this name.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West M ...

. It was here that, in October 1850, the local physician William Penny Brookes founded the Wenlock Olympian Games

The Wenlock Olympian Games, dating from 1850, are a forerunner of the modern Olympic Games. They are organised by the Wenlock Olympian Society (WOS), and are held each year at venues across Shropshire, England, centred on the market town of Much ...

, a festival of sports and recreations that included athletics and team sports, such as cricket

Cricket is a Bat-and-ball games, bat-and-ball game played between two Sports team, teams of eleven players on a cricket field, field, at the centre of which is a cricket pitch, pitch with a wicket at each end, each comprising two Bail (cr ...

, football

Football is a family of team sports that involve, to varying degrees, kick (football), kicking a football (ball), ball to score a goal (sports), goal. Unqualified, football (word), the word ''football'' generally means the form of football t ...

and quoits

Quoits ( or ) is a traditional game which involves the throwing of metal, rope or rubber rings over a set distance, usually to land over or near a spike (sometimes called a hob, mott or pin). The game of quoits encompasses several distinct vari ...

. Coubertin also took inspiration from the earlier Greek games organised under the name of Olympics

The modern Olympic Games (Olympics; ) are the world's preeminent international sporting events. They feature summer and winter sports competitions in which thousands of athletes from around the world participate in a variety of competit ...

by businessman and philanthropist Evangelis Zappas

Evangelos or Evangelis Zappas (23 August 1800 – 19 June 1865) was a Greek philanthropist and businessman who is recognized today as one of the founders of the modern Olympic Games, which were held in 1859, 1870, 1875, and 1888 and preceded ...

in 1859, 1870 and 1875. The 1896 Athens Games were funded by the legacies of Evangelis Zappas

Evangelos or Evangelis Zappas (23 August 1800 – 19 June 1865) was a Greek philanthropist and businessman who is recognized today as one of the founders of the modern Olympic Games, which were held in 1859, 1870, 1875, and 1888 and preceded ...

and his cousin Konstantinos Zappas

Konstantinos Zappas (; 1814–1892) was a Greek entrepreneur and national benefactor who together with his cousin, Evangelos Zappas, played an essential role in the revival of the Olympic Games.

Biography

Zappas was born in 1814 in the village ...

and by George Averoff

George M. Averoff (15 August 1815 – 15 July 1899), alternately Jorgos Averof or Georgios Averof (in Greek: Γεώργιος Αβέρωφ), was a Greek businessman and philanthropist. He is one of the great national benefactors of Greece. Bor ...

who had been specifically requested by the Greek government, through crown prince Constantine, to sponsor the second refurbishment of the Panathenaic Stadium

The Panathenaic Stadium (, ) or ''Kallimarmaro'' ( , ) is a multi-purpose stadium in Athens, Greece. One of the main historic attractions of Athens, it is the only stadium in the world built entirely of marble.

A stadium was built on the site o ...

. The Greek government did this despite the cost of refurbishing the stadium in marble already being funded in full by Evangelis Zappas forty years earlier.

On 18 June 1894, Coubertin organised a congress at the Sorbonne, Paris, to present his plans to representatives of sports societies from 11 countries. Following his proposal's acceptance by the congress, a date for the first modern Olympic Games needed to be chosen. Coubertin suggested that the Games be held concurrently with the 1900 Universal Exposition

A world's fair, also known as a universal exhibition, is a large global exhibition designed to showcase the achievements of nations. These exhibitions vary in character and are held in different parts of the world at a specific site for a perio ...

of Paris. Concerned that a six-year waiting period might lessen public interest, congress members opted instead to hold the inaugural Games in 1896. With a date established, members of the congress turned their attention to the selection of a host city. It remains a mystery how Athens was finally chosen to host the inaugural Games. In the following years, both Coubertin and Demetrius Vikelas

Demetrios Vikelas (; ; 15 February 1835 – 20 July 1908) was a Greek businessman and writer; he was the co-founder and first president of the International Olympic Committee (IOC), from 1894 to 1896.

After a childhood spent in Greece and Is ...

would offer recollections of the selection process that contradicted the official minutes of the congress. Most accounts hold that several congressmen first proposed London as the location, but Coubertin dissented. After a brief discussion with Vikelas, who represented Greece, Coubertin suggested Athens. Vikelas made the Athens proposal official on 23 June, and since Greece had been the original home of the Olympics, the congress unanimously approved the decision. Vikelas was then elected the first president of the newly established International Olympic Committee

The International Olympic Committee (IOC; , CIO) is the international, non-governmental, sports governing body of the modern Olympic Games. Founded in 1894 by Pierre de Coubertin and Demetrios Vikelas, it is based i ...

(IOC).

Organization

News that the Olympic Games would return to Greece was well received by the Greek public, media, androyal family

A royal family is the immediate family of monarchs and sometimes their extended family.

The term imperial family appropriately describes the family of an emperor or empress, and the term papal family describes the family of a pope, while th ...

. According to Coubertin, "the Crown Prince Constantine learned with great pleasure that the Games will be inaugurated in Athens." Coubertin went on to confirm that, "the King and the Crown Prince will confer their patronage on the holding of these games." Constantine later conferred more than that; he eagerly assumed the presidency of the 1896 organising committee.

However, the country had financial troubles and was in political turmoil. The job of prime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

alternated between Charilaos Trikoupis

Charilaos Trikoupis (; 11 July 1832 – 30 March 1896) was a Greek politician who served as a Prime Minister of Greece seven times from 1875 until 1895.

He is best remembered for introducing the vote of confidence in the Greek constitution, p ...

and Theodoros Deligiannis

Theodoros Diligiannis (also transliterated as Deligiannis;Konstantinos Apostolou Vakalopoulos, ''Modern History of Macedonia (1830-1912)'', Barbounakis, 1988, p. 95. ; 1826–1905) was a Greek politician, minister and member of the Greek Parlia ...

frequently during the last years of the 19th century. Because of this financial and political instability, both prime minister Trikoupis and Stephanos Dragoumis

Stefanos Dragoumis (; 184217 September 1923) was a judge, writer and the Prime Minister of Greece from January to October 1910. He was the father of Ion Dragoumis.

Early years

Dragoumis was born in Athens. His grandfather, Markos Dragoumis (1 ...

, the president of the Zappas Olympic Committee, which had attempted to organise a series of national Olympiads, believed that Greece could not host the event. In late 1894, the organising committee under Stephanos Skouloudis

Stefanos Skouloudis (; 23 November 1838 – 19 August 1928) was a Greek banker, diplomat and the 34th Prime Minister of Greece.

Early life

He was born in Istanbul on 23 November 1838. His parents, John and Zena Skouloudis, were originally from ...

presented a report that the cost of the Games would be three times higher than originally estimated by Coubertin. They concluded the Games could not be held and offered their resignation. The total cost of the Games was 3,740,000 gold drachma

Drachma may refer to:

* Ancient drachma, an ancient Greek currency

* Modern drachma

The drachma ( ) was the official currency of modern Greece from 1832 until the launch of the euro in 2001.

First modern drachma

The drachma was reintroduce ...

s.

With the prospect of reviving the Olympic games very much in doubt, Coubertin and Vikelas commenced a campaign to keep the Olympic movement alive. Their efforts culminated on 7 January 1895 when Vikelas announced that crown prince Constantine would assume the presidency of the organising committee. His first responsibility was to raise the funds necessary to host the Games. He relied on the patriotism of the Greek people to motivate them to provide the required finances. Constantine's enthusiasm sparked a wave of contributions from the Greek public. This grassroots effort raised 330,000 drachmas. A special set of postage stamps was commissioned; the sale of which raised 400,000 drachmas. Ticket sales added 200,000 drachmas. At the request of Constantine, businessman

With the prospect of reviving the Olympic games very much in doubt, Coubertin and Vikelas commenced a campaign to keep the Olympic movement alive. Their efforts culminated on 7 January 1895 when Vikelas announced that crown prince Constantine would assume the presidency of the organising committee. His first responsibility was to raise the funds necessary to host the Games. He relied on the patriotism of the Greek people to motivate them to provide the required finances. Constantine's enthusiasm sparked a wave of contributions from the Greek public. This grassroots effort raised 330,000 drachmas. A special set of postage stamps was commissioned; the sale of which raised 400,000 drachmas. Ticket sales added 200,000 drachmas. At the request of Constantine, businessman George Averoff

George M. Averoff (15 August 1815 – 15 July 1899), alternately Jorgos Averof or Georgios Averof (in Greek: Γεώργιος Αβέρωφ), was a Greek businessman and philanthropist. He is one of the great national benefactors of Greece. Bor ...

agreed to pay for the restoration of the Panathenaic Stadium. Averoff would donate 920,000 drachmas to this project. As a tribute to his generosity, a statue of Averoff was constructed and unveiled on 5 April 1896 outside the stadium. It stands there to this day.

Some of the athletes would take part in the Games because they happened to be in Athens at the time the Games were held, either on holiday or for work (e.g., some of the British competitors worked for the British embassy

A diplomatic mission or foreign mission is a group of people from a Sovereign state, state or organization present in another state to represent the sending state or organization officially in the receiving or host state. In practice, the phrase ...

). A designated Olympic Village

An Olympic Village is a residential complex built or reassigned for the Olympic Games in or nearby the List of Olympic Games host cities, host city for the purpose of accommodating all of the delegations. Olympic Villages are usually located clos ...

for the athletes did not appear until the 1932 Summer Olympics

The 1932 Summer Olympics (officially the Games of the X Olympiad and also known as Los Angeles 1932) were an international multi-sport event held from July 30 to August 14, 1932, in Los Angeles, California, United States. The Games were held du ...

. Consequently, the athletes had to provide their own lodging.

The first regulation voted on by the new IOC in 1894 was to allow only amateur athletes to participate in the Olympic Games. The various contests were thus held under amateur regulations with the exception of fencing matches. The rules and regulations were not uniform, so the Organising Committee had to choose among the codes of the various national athletic associations. The jury, the referees and the game director bore the same names as in antiquity (''Ephor'', ''Helanodic'' and ''Alitarc''). Prince George acted as final referee; according to Coubertin, "his presence gave weight and authority to the decisions of the ephors".

Women were not entitled to compete at the 1896 Summer Olympics, because de Coubertin felt that their inclusion would be "impractical, uninteresting, unaesthetic and incorrect".

Venues

Seven venues were used for the 1896 Summer Olympics.

Seven venues were used for the 1896 Summer Olympics. Panathenaic Stadium

The Panathenaic Stadium (, ) or ''Kallimarmaro'' ( , ) is a multi-purpose stadium in Athens, Greece. One of the main historic attractions of Athens, it is the only stadium in the world built entirely of marble.

A stadium was built on the site o ...

was the main venue, hosting four of the nine sports contested. The town of Marathon

The marathon is a long-distance foot race with a distance of kilometres ( 26 mi 385 yd), usually run as a road race, but the distance can be covered on trail routes. The marathon can be completed by running or with a run/walk strategy. There ...

served as host to the marathon

The marathon is a long-distance foot race with a distance of kilometres ( 26 mi 385 yd), usually run as a road race, but the distance can be covered on trail routes. The marathon can be completed by running or with a run/walk strategy. There ...

event and the individual road race events. Swimming

Swimming is the self-propulsion of a person through water, such as saltwater or freshwater environments, usually for recreation, sport, exercise, or survival. Swimmers achieve locomotion by coordinating limb and body movements to achieve hydrody ...

was held in the Bay of Zea

The Bay of Zea (), since Ottoman times and until recently known as Paşalimanı (Πασαλιμάνι), is a broad bay located at the eastern coast of the Piraeus peninsula in Attica, Greece. It hosted the swimming events at the 1896 Summer ...

, fencing

Fencing is a combat sport that features sword fighting. It consists of three primary disciplines: Foil (fencing), foil, épée, and Sabre (fencing), sabre (also spelled ''saber''), each with its own blade and set of rules. Most competitive fe ...

at the Zappeion

The Zappeion (, ) is a large, palatial building next to the National Gardens of Athens in the heart of Athens, Greece. It is generally used for meetings and ceremonies, both official and private and is one of the city's most renowned modern land ...

, sport shooting

Shooting sports is a group of competitive sport, competitive and recreational sporting activities involving proficiency tests of accuracy, precision and speed in shooting — the art of using ranged weapons, mainly small arms (firearms and airg ...

at Kallithea

Kallithea (Greek language, Greek: Καλλιθέα, meaning "beautiful view") is a suburb in Athens#Athens Urban Area, Athens agglomeration and a municipality in South Athens (regional unit), south Athens regional unit. It is the eighth larges ...

, and tennis

Tennis is a List of racket sports, racket sport that is played either individually against a single opponent (singles (tennis), singles) or between two teams of two players each (doubles (tennis), doubles). Each player uses a tennis racket st ...

at the Athens Lawn Tennis Club

The Athens Lawn Tennis Club (Greek language, Greek: Όμιλος Αντισφαίρισης Αθηνών) is a sports club, multi-sports club that is located in Athens, Greece. The club currently has departments in contract bridge, bridge, gymnast ...

. Tennis was a sport unfamiliar to Greeks at the time of the 1896 Games.

The Bay of Zea is a seaport

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as Hamburg, Manc ...

and marina

A marina (from Spanish , Portuguese and Italian : "related to the sea") is a dock or basin with moorings and supplies for yachts and small boats.

A marina differs from a port in that a marina does not handle large passenger ships or cargo ...

in the Athens area; it was used as the swimming venue because the organizers of the Games wanted to avoid spending money on constructing a special purpose swimming venue.

Four of the 1896 venues were reused as competition venues for the 2004 Games. The velodrome

A velodrome is an arena for track cycling. Modern velodromes feature steeply banked oval tracks, consisting of two 180-degree circular bends connected by two straights. The straights transition to the circular turn through a moderate easement ...

would be renovated into a football

Football is a family of team sports that involve, to varying degrees, kick (football), kicking a football (ball), ball to score a goal (sports), goal. Unqualified, football (word), the word ''football'' generally means the form of football t ...

stadium in 1964 and was known as Karaiskakis Stadium

The Georgios Karaiskakis Stadium (), commonly referred to as the Karaiskakis Stadium (, ), is a Association football, football stadium in Piraeus, Attica, Greece, and the home ground of the Piraeus football club Olympiacos F.C., Olympiacos. It i ...

. This venue was renovated in 2003 for use as a football

Football is a family of team sports that involve, to varying degrees, kick (football), kicking a football (ball), ball to score a goal (sports), goal. Unqualified, football (word), the word ''football'' generally means the form of football t ...

venue for the 2004 Games. During the 2004 Games, Panathinaiko Stadium served as host for archery

Archery is the sport, practice, or skill of using a Bow and arrow, bow to shooting, shoot arrows.Paterson ''Encyclopaedia of Archery'' p. 17 The word comes from the Latin ''arcus'', meaning bow. Historically, archery has been used for hunting ...

competitions and was the finish line for the athletic marathon event. The city of Marathon itself served as the starting point for both marathon events during the 2004 Games. The Zappeion served as the first home of the organizing committee (ATHOC) for the 2004 Games from 1998 to 1999, and served as the main communications center during those Games.

Calendar

‡ The iconicOlympic rings

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) uses icons, flags, and symbols to represent and enhance the Olympic Games. These symbols include those commonly used during Olympic competitions such as the flame, fanfare, and theme as well as those u ...

symbol was not designed by Baron Pierre de Coubertin

Charles Pierre de Frédy, Baron de Coubertin (; born Pierre de Frédy; 1 January 1863 – 2 September 1937), also known as Pierre de Coubertin and Baron de Coubertin, was a French educator and historian, co-founder of the International Olympic ...

until 1912.

Note: Silver medals were awarded to the winners, with copper medals given to the runners-up, and no prizes were given to those who came in 3rd place in any events.

Opening ceremony

On

On Easter Monday

Easter Monday is the second day of Eastertide and a public holiday in more than 50 predominantly Christian countries. In Western Christianity it marks the second day of the Octave of Easter; in Eastern Christianity it marks the second day of Br ...

6 April (25 March according to the Julian calendar

The Julian calendar is a solar calendar of 365 days in every year with an additional leap day every fourth year (without exception). The Julian calendar is still used as a religious calendar in parts of the Eastern Orthodox Church and in parts ...

used in Greece until 1923), the games of the First Olympiad were officially opened. The Panathenaic Stadium was filled with an estimated 80,000 spectators, including King George I of Greece

George I ( Greek: Γεώργιος Α΄, romanized: ''Geórgios I''; 24 December 1845 – 18 March 1913) was King of Greece from 30 March 1863 until his assassination on 18 March 1913.

Originally a Danish prince, George was born in Copenhage ...

, his wife Olga

Olga may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Olga (name), a given name, including a list of people and fictional characters named Olga or Olha

* Michael Algar (born 1962), English singer also known as "Olga"

Places

Russia

* Olga, Russia ...

, and their sons. Most of the competing athletes were aligned on the infield, grouped by nation. After a speech by the president of the organising committee, Crown Prince Constantine, his father officially opened the Games with the words (in Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

):Athens 1896 – Games of the I OlympiadInternational Olympic Committee Afterwards, nine bands and 150 choir singers performed an

Olympic Hymn

The Olympic Hymn (, ), also known as the Olympic Anthem, is a choral cantata by opera composer Spyridon Samaras (1861–1917), with Demotic Greek lyrics by Greek poet Kostis Palamas. Both poet and composer were the choice of the Greek Deme ...

, composed by Spyridon Samaras

Spyridon-Filiskos Samaras () (29 November 1861 - 7 April 1917) was a Greek composer particularly admired for his operas. His compositions were praised worldwide during his lifetime and he is arguably the most important composer of the Ionian Scho ...

, with words by poet Kostis Palamas

Kostis Palamas (; ; – 27 February 1943) was a Greek poet who wrote the words to the Olympic Hymn. He was a central figure of the Greek literary generation of the 1880s and one of the cofounders of the so-called New Athenian School (or Pala ...

. Thereafter, a variety of musical offerings provided the backgrounds to the Opening Ceremonies until 1960

It is also known as the "Year of Africa" because of major events—particularly the independence of seventeen African nations—that focused global attention on the continent and intensified feelings of Pan-Africanism.

Events January

* Janu ...

, since which time the Samaras/Palamas composition has become the official Olympic Anthem (decision taken by the IOC Session in 1958). Other elements of current Olympic opening ceremonies were initiated later: the Olympic flame

The Olympic flame is a Olympic symbols, symbol used in the Olympic movement. It is also a symbol of continuity between ancient and modern games. The Olympic flame is lit at Olympia, Greece, several months before the Olympic Games. This ceremony s ...

was first lit in 1928

Events January

* January – British bacteriologist Frederick Griffith reports the results of Griffith's experiment, indirectly demonstrating that DNA is the genetic material.

* January 1 – Eastern Bloc emigration and defection: Boris B ...

, the first athletes' oath was sworn at the 1920 Summer Olympics

The 1920 Summer Olympics (; ; ), officially known as the Games of the VII Olympiad (; ; ) and commonly known as Antwerp 1920 (; Dutch language, Dutch and German language, German: ''Antwerpen 1920''), were an international multi-sport event held i ...

, and the first officials' oath was taken at the 1972 Olympic Games.

Events

At the 1894 Sorbonne Congress, a large roster of sports was suggested for the program in Athens. The first official announcements regarding the sporting events to be held featured sports such as football and cricket, but these plans were not finalised, and these sports did not make the final program for the Games.Rowing

Rowing is the act of propelling a human-powered watercraft using the sweeping motions of oars to displace water and generate reactional propulsion. Rowing is functionally similar to paddling, but rowing requires oars to be mechanically a ...

and sailing

Sailing employs the wind—acting on sails, wingsails or kites—to propel a craft on the surface of the ''water'' (sailing ship, sailboat, raft, Windsurfing, windsurfer, or Kitesurfing, kitesurfer), on ''ice'' (iceboat) or on ''land'' (Land sa ...

events were also scheduled but were cancelled on the planned days of competition: sailing due to a lack of special boats in Greece and no foreign entries, and rowing due to poor weather.Coubertin–Philemon–Politis–Anninos (1897)

As a result, the 1896 Summer Olympics programme featured 9 sports encompassing 10 disciplines and 43 events. The number of events in each discipline is noted in parentheses.

Athletics

The athletics events had the most international field of any of the sports. The major highlight was themarathon

The marathon is a long-distance foot race with a distance of kilometres ( 26 mi 385 yd), usually run as a road race, but the distance can be covered on trail routes. The marathon can be completed by running or with a run/walk strategy. There ...

, held for the first time in international competition. Spyridon Louis

Spyridon Louis ( , sometimes transliterated ''Spiridon Loues''; 12 January 1873 – 26 March 1940), commonly known as Spyros Louis (Σπύρος Λούης), was a Greek water carrier who won the first modern-day Olympic marathon at the 1896 ...

, a previously unrecognised water carrier, won the event to become the only Greek athletics champion and a national hero. Although Greece had been favoured to win the discus and the shot put

The shot put is a track-and-field event involving "putting" (throwing) a heavy spherical Ball (sports), ball—the ''shot''—as far as possible. For men, the sport has been a part of the Olympic Games, modern Olympics since their 1896 Summer Olym ...

, the best Greek athletes finished just behind the American Robert Garrett

Robert S. Garrett (May 24, 1875 – April 25, 1961) was an American athlete, as well as investment banker and philanthropist in Baltimore, Maryland and financier of several important archeological excavations. Garrett was the first modern ...

in both events.

No world record

A world record is usually the best global and most important performance that is ever recorded and officially verified in a specific skill, sport, or other kind of activity. The book ''Guinness World Records'' and other world records organizatio ...

s were set, as few top international competitors had elected to compete. In addition, the curves of the track were very tight, making fast times in the running events virtually impossible. Despite this, Thomas Burke, of the United States, won the 100-meter

The 100 metres, or 100-meter dash, is a sprint race in track and field competitions. The shortest common outdoor running distance, the dash is one of the most popular and prestigious events in the sport of athletics. It has been contested at ...

race in 12.0 seconds and the 400-meter race in 54.2 seconds. Burke was the only one who used the "crouch start

Sprinting is running over a short distance at the top-most speed of the body in a limited period of time. It is used in many sports that incorporate running, typically as a way of quickly reaching a target or goal, or avoiding or catching an op ...

" (putting his knee on soil), confusing the jury. Eventually, he was allowed to start from this "uncomfortable position".

Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in western South America. It is the southernmost country in the world and the closest to Antarctica, stretching along a narrow strip of land between the Andes, Andes Mountains and the Paci ...

claims one athlete, Luis Subercaseaux

Luis Subercaseaux Errázuriz (10 May 1882 – 1973) was a Chilean diplomat and athlete. He is claimed to be the first Chilean and Latin American sportsman to have competed in the Olympic Games, at the 1896 Summer Olympics in Athens.

Biography

B ...

, who competed for the nation at the 1896 Summer Olympics. This makes Chile one of the 14 nations to appear at the inaugural Summer Olympic Games. Subercaseaux's results are not listed in the official report, though that report typically includes only winners and Subercaseaux won no medals. Some sources claim that he was entered to compete in the 100m, 400m and 800m events but did not start. An appraisal of a famous photo of series 2 of the 100 meters sprint, performed by facial recognition experts of the Chilean forensic police, concluded that Subercaseaux was one of the participants.

The day after the official marathon, Stamata Revithi

Stamata Revithi (; 1866 – after 1896) was a Greek woman who ran the 40-kilometre marathon during the 1896 Summer Olympics. The Games excluded women from competition, but Revithi insisted that she be allowed to run. Revithi ran one day after ...

ran the 40-kilometer course in 5 hours 30 minutes, finishing outside Panathinaiko Stadium

The Panathenaic Stadium (, ) or ''Kallimarmaro'' ( , ) is a multi-purpose stadium in Athens, Greece. One of the main historic attractions of Athens, it is the only stadium in the world built entirely of marble.

A stadium was built on the site o ...

. However, some of the authors, who believe that "Melpomene" and Revithi are the same person, attribute to the latter the more favorable time of hours. She was denied entry into the official race as the 1896 Olympics excluded women from competition.

Cycling

The rules of theInternational Cycling Association The International Cycling Association (ICA) was the first international body for cycle racing. Founded by Henry Sturmey in 1892 to establish a common definition of amateurism and to organise world championships its role was taken over by the Unio ...

were used for the cycling competitions. The track cycling

Track cycling is a Cycle sport, bicycle racing sport usually held on specially built banked tracks or velodromes using purpose-designed track bicycles.

History

Track cycling has been around since at least 1870. When track cycling was in its i ...

events were held at the newly built Neo Phaliron Velodrome

The Neo Phaliron Velodrome (New Phaleron) was a velodrome and sports arena in the Neo Faliro District of Piraeus, Greece, used for the cycling sport, cycling events at the 1896 Summer Olympics held in Athens.Quote from page 194/241: ''The bicycle ...

. Only one road event was held, a race from Athens to Marathon and back (87 kilometres).

In the track events, the best cyclist was Frenchman Paul Masson

Paul Masson (February 14, 1859 – October 22, 1940) was a French-born American winemaker. He is considered an early pioneer of California viticulture known for his brand of Californian sparkling wine.

Biography

Masson was born as the seco ...

, who won the one lap time trial

In many racing sports, an sportsperson, athlete (or occasionally a team of athletes) will compete in a time trial (TT) against the clock to secure the fastest time. The format of a time trial can vary, but usually follow a format where each athle ...

, the sprint event, and the 10,000 meters. In the 100 kilometres event, Masson entered as a pacemaker for his compatriot Léon Flameng

Marie Léon Flameng (30 April 1877 – 2 January 1917) was a French cycle sport, cyclist and a World War I pilot. He competed at the 1896 Summer Olympics in Athens, winning three medals including one gold.

Olympics

Flameng competed in f ...

. Flameng won the event, after a fall, and after stopping to wait for his Greek opponent Georgios Kolettis

Georgios Koletis () was a Greek cyclist. He competed at the 1896 Summer Olympics in Athens, winning a silver medal.

Career

Koletis competed in the 10 and 100-kilometres races. He finished second in the 100 kilometers, behind Léon Flameng of Fr ...

to fix a mechanical problem. The Austrian fencer Adolf Schmal

Felix Adolf Schmal (18 September 1872 – 28 August 1919) was an Austrian fencer and racing cyclist. He was born in Dortmund and died in Salzburg. He competed at the 1896 Summer Olympics in Athens.

1896 Olympics

With a fencing mask, sabre ...

won the 12-hour race, which was completed by only two cyclists, while the road race event was won by Aristidis Konstantinidis

Aristidis Konstantinidis () was a Greek racing cyclist. He competed at the 1896 Summer Olympics in Athens.

Olympic success in 1896

Konstantinidis competed in the 10 kilometres, 100 kilometres, and road races. He won the road race, covering the ...

.Lennartz-Wassong (2004), 23

Fencing

The fencing events were held in theZappeion

The Zappeion (, ) is a large, palatial building next to the National Gardens of Athens in the heart of Athens, Greece. It is generally used for meetings and ceremonies, both official and private and is one of the city's most renowned modern land ...

, which, built with money Evangelis Zappas

Evangelos or Evangelis Zappas (23 August 1800 – 19 June 1865) was a Greek philanthropist and businessman who is recognized today as one of the founders of the modern Olympic Games, which were held in 1859, 1870, 1875, and 1888 and preceded ...

had given to revive the ancient Olympic Games, had never seen any athletic contests before. Unlike other sports (in which only amateurs were allowed to take part at the Olympics), professionals were authorised to compete in fencing, though in a separate event. These professionals were considered gentlemen athletes, just like the amateurs.

Four events were scheduled, but the épée

The (, ; ), also rendered as epee in English, is the largest and heaviest of the three weapons used in the sport of fencing. The modern derives from the 19th-century , a weapon which itself derives from the French small sword. This contains a ...

event was cancelled for unknown reasons. The foil event was won by a Frenchman, Eugène-Henri Gravelotte

Eugène-Henri Gravelotte (6 February 1876 – 23 August 1939) was a French fencing (sport), fencer. He was the first modern Olympic Games, Olympic champion in foil and first French gold medalist, winning the event at the 1896 Summer Olympics ...

, who beat his countryman, Henri Callot

Eugène Henri Callot (20 December 1875 – 22 December 1956) was a French fencing, fencer. He competed at the 1896 Summer Olympics in Athens. He was born in La Rochelle.

Callot won the silver medal in the amateur foil (sword), foil event. ...

, in the final. The other two events, the sabre

A sabre or saber ( ) is a type of backsword with a curved blade associated with the light cavalry of the Early Modern warfare, early modern and Napoleonic period, Napoleonic periods. Originally associated with Central European cavalry such a ...

and the masters foil, were won by Greek fencers. Leonidas Pyrgos

Leonidas "Leon" Pyrgos (, born 1874 in Mantineia, Arcadia; date of death unknown) was a Greek fencer.

Career

Pyrgos was the first Greek Olympic medallist in the history of the modern Olympic Games, winning his fencing event of the 1896 Summe ...

, who won the latter event, became the first Greek Olympic champion in the modern era.

Gymnastics

The gymnastics competition was carried out on the infield of the Panathinaiko Stadium. Germany sent an 11-man team, which won five of the eight events, including both team events: in the team event on thehorizontal bar

The horizontal bar, also known as the high bar, is an apparatus used by male gymnasts in artistic gymnastics. It traditionally consists of a cylindrical metal (typically steel) bar that is rigidly held above and parallel to the floor by a syst ...

, the German team was the only entry.

Three Germans added individual titles: Hermann Weingärtner

Otto Ludwig Hermann Weingärtner (27 August 1864 – 22 December 1919) was a German gymnast.

He started his career in his hometown Frankfurt (Oder) at the local gymnastics club ''Frankfurter Turnverein 1860''. Later on he moved to Berlin to ...

won the horizontal bar event, Alfred Flatow

Alfred Flatow (3 October 1869 – 28 December 1942) was a Jews, Jewish Germany, German gymnastics, gymnast. He competed at the 1896 Summer Olympics in Athens. He was murdered in the Holocaust.

Biography

Flatow was a successful competitor in 18 ...

won the parallel bars

Parallel bars are floor apparatus consisting of two wooden bars approximately long and positioned at above the floor. Parallel bars are used in artistic gymnastics and also for physical therapy and home exercise. Gymnasts may optionally wear ...

, and Carl Schuhmann

Carl August Berthold Schuhmann (12 May 1869 – 24 March 1946) was a German athlete who won four Olympic titles in gymnastics and wrestling at the 1896 Summer Olympics in Athens, becoming the most successful athlete at the inaugural Olympics ...

, who also won the wrestling event, won the vault

Vault may refer to:

* Jumping, the act of propelling oneself upwards

Architecture

* Vault (architecture), an arched form above an enclosed space

* Bank vault, a reinforced room or compartment where valuables are stored

* Burial vault (enclosur ...

. Louis Zutter

Jules Alexis "Louis" Zutter (2 December 1865 – 10 November 1946) was a Swiss gymnast. He competed at the 1896 Summer Olympics in Athens.

Zutter won one of the events, the pommel horse. He was also the runner-up in two more events, the va ...

, a Swiss gymnast, won the pommel horse

The pommel horse, also known as vaulting horse, is an artistic gymnastics apparatus. Traditionally, it is used by only male gymnasts. Originally made of a metal frame with a wooden body and a leather cover, the modern pommel horse has a metal bo ...

, while Greeks Ioannis Mitropoulos

Ioannis Mitropoulos (; 1874 – after 1896) was a Greek gymnast. He competed at the 1896 Summer Olympics in Athens.

Mitropoulos competed in both the individual and team events of the parallel bars, and the individual rings event. In the rings ...

and Nikolaos Andriakopoulos

Nikolaos Andriakopoulos (; 1878 in Patras – after 1896) was a Greek gymnast. He was a member of Panachaikos Gymnastikos Syllogos, that merged in 1923 with Gymnastiki Etaireia Patron to become Panachaiki Gymnastiki Enosi.

Olympics performances ...

were victorious in the rings and rope climbing

Rope climbing is a sport in which competitors attempt to climb up a suspended vertical rope using only their hands. Rope climbing is practiced regularly at the World Police and Fire Games. Also, enthusiasts in the Czech Republic resurrected the ...

events, respectively.

Sailing and rowing

A regatta of sailing boats was on the program of the Games of the First Olympiad for 31 March 1896 (Julian calendar). However this event had to be given up.

The official English report states:

The German version states:

Rowing races were scheduled for the next day, 1 April 1896 (Julian); however, poor weather forced their cancellation.

The official English report states:

The German rower, Berthold Küttner, wrote several articles about the 1896 Games that were published in his Berlin rowing club's magazine in 1936 and reprinted in the

A regatta of sailing boats was on the program of the Games of the First Olympiad for 31 March 1896 (Julian calendar). However this event had to be given up.

The official English report states:

The German version states:

Rowing races were scheduled for the next day, 1 April 1896 (Julian); however, poor weather forced their cancellation.

The official English report states:

The German rower, Berthold Küttner, wrote several articles about the 1896 Games that were published in his Berlin rowing club's magazine in 1936 and reprinted in the Journal of Olympic History

The International Society of Olympic Historians (ISOH) is a non-profit organization founded in 1991 with the purpose of promoting and studying the Olympic Movement and the Olympic Games. The majority of recent books on the Olympic Games have been ...

in 2012. He stated that he and Adolf Jäger had lined up for the start of the double sculls

A double scull, also abbreviated as a 2x, is a rowing boat used in the sport of competitive rowing. It is designed for two persons who propel the boat by sculling with two oars each, one in each hand.

Racing boats (often called "shells") are ...

event. He further wrote that "The double scull would be the first to start because the wind had become much stronger. On a fishing boat we took our double scull to the starting line. We already had problems getting into the double scull because of the swells. From our opponents no one had appeared – although both Greeks and Italians had applied. Because a longer wait for them seemed pointless, the starter told us to sail without competition.

"After the official salutation and presentation in the Court Loge, where many of the attendees could not hide a laugh about my clothing, Prince George, President of the Committee, praised me for our appearance at the racing track and presented me with the winners medal in bronze. At the same time he also gave me one for ''Bundesbruder'' Jäger. The commemorative medal, which each of the participants received, had already been presented to us earlier."

He went on to state that the single sculls and race for naval boats were postponed until the following day, then ultimately cancelled when the weather worsened. The International Olympic Committee

The International Olympic Committee (IOC; , CIO) is the international, non-governmental, sports governing body of the modern Olympic Games. Founded in 1894 by Pierre de Coubertin and Demetrios Vikelas, it is based i ...

does not recognize any of this.

Shooting

Held at a range atKallithea

Kallithea (Greek language, Greek: Καλλιθέα, meaning "beautiful view") is a suburb in Athens#Athens Urban Area, Athens agglomeration and a municipality in South Athens (regional unit), south Athens regional unit. It is the eighth larges ...

, the shooting competition consisted of five events—two using a rifle and three with the pistol

A pistol is a type of handgun, characterised by a gun barrel, barrel with an integral chamber (firearms), chamber. The word "pistol" derives from the Middle French ''pistolet'' (), meaning a small gun or knife, and first appeared in the Englis ...

. The first event, the military rifle, was won by Pantelis Karasevdas

Pantelis Karasevdas (; 1877 – 14 March 1946) was a Greek sport shooter. He was a member of Panachaikos Gymnastikos Syllogos, that merged in 1923 with Gymnastiki Etaireia Patron to become Panachaiki Gymnastiki Enosi. Karasevdas competed at the ...

, the only competitor to hit the target with all of his shots. The second event, for military pistols, was dominated by two American brothers: John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second E ...

and Sumner Paine

Sumner Paine (May 13, 1868 – April 18, 1904) was an American shooting sports, shooter. He competed at the 1896 Summer Olympics in Athens.

Biography

Sumner Paine was born in Boston on May 13, 1868. His father was Charles Jackson Paine, ...

. They became the first siblings to finish first and second in the same event. To avoid embarrassing their hosts, the brothers decided that only one of them would compete in the next pistol event, the free pistol

50 meter pistol, formerly and unofficially still often called Free Pistol, is one of the ISSF shooting events. It is one of the oldest shooting disciplines, dating back to the 19th century and only having seen marginal rule changes since 1936. I ...

. Sumner Paine won that event, thereby becoming the first relative of an Olympic champion to become Olympic champion himself.Coubertin–Philemon–Politis–Anninos (1897), 76, 83–84

The Paine brothers did not compete in the 25-meter pistol event, as the event judges determined that their weapons were not of the required calibre. In their absence, Ioannis Phrangoudis

Ioannis Frangoudis (; 1863 – 19 October 1916) was a Greek Cypriot Military officer, athlete and Olympic shooter. He served in the Hellenic Army reaching the rank of Colonel, and represented the kingdom of Greece in the 1896 Summer Olympics in ...

won. The final event, the free rifle, began on the same day. However, the event could not be completed due to darkness and was finalised the next morning, when Georgios Orphanidis

Georgios D. Orphanidis (; 1859–1942) was an ethnic Greek sports shooter with both pistol and rifle. He competed for Greece at the 1896 Summer Olympics in Athens, at the 1906 Intercalated Games, and at the 1908 Summer Olympics in London.

In 189 ...

was crowned the champion.

Swimming

The swimming competition was held in the open sea because the organizers had refused to spend the money necessary for a specially constructed stadium. Nearly 20,000 spectators lined the

The swimming competition was held in the open sea because the organizers had refused to spend the money necessary for a specially constructed stadium. Nearly 20,000 spectators lined the Bay of Zea

The Bay of Zea (), since Ottoman times and until recently known as Paşalimanı (Πασαλιμάνι), is a broad bay located at the eastern coast of the Piraeus peninsula in Attica, Greece. It hosted the swimming events at the 1896 Summer ...

off the Piraeus

Piraeus ( ; ; , Ancient: , Katharevousa: ) is a port city within the Athens urban area ("Greater Athens"), in the Attica region of Greece. It is located southwest of Athens city centre along the east coast of the Saronic Gulf in the Ath ...

coast to watch the events. The water in the bay was cold, and the competitors suffered during their races. There were three open events ( men's 100-metre freestyle, men's 500-metre freestyle, and men's 1200 metre freestyle), in addition to a special event open only to Greek sailors, all of which were held on the same day (11 April).

For Alfréd Hajós

Alfréd Hajós (1 February 1878 – 12 November 1955) was a Hungarian swimmer, football (soccer) player, referee, manager, and career architect. He was the first modern Olympic swimming champion and the first Olympic champion of Hungary. Form ...

of Hungary, this meant he could only compete in two of the events, as they were held too close together, which made it impossible for him to adequately recuperate. Nevertheless, he won the two events in which he swam, the 100 and 1200 meter freestyle

Freestyle may refer to:

Brands

* Reebok Freestyle, a women's athletic shoe

* Ford Freestyle, an SUV automobile

* Coca-Cola Freestyle, a vending machine

* Abbott FreeStyle, a blood glucose monitor by Abbott Laboritories

Media

* '' FreeStyle'', ...

. Hajós later became one of only two Olympians to win a medal in both the athletic and artistic competitions, when he won a silver medal for architecture in 1924. The 500-meter freestyle was won by Austrian swimmer Paul Neumann, who defeated his opponents by more than a minute and a half.

Tennis

Although tennis was already a major sport by the end of the 19th century, none of the top players turned up for the tournament in Athens. The competition was held at the courts of theAthens Lawn Tennis Club

The Athens Lawn Tennis Club (Greek language, Greek: Όμιλος Αντισφαίρισης Αθηνών) is a sports club, multi-sports club that is located in Athens, Greece. The club currently has departments in contract bridge, bridge, gymnast ...

, and the infield of the velodrome used for the cycling events. John Pius Boland

John Mary Pius Boland (16 September 1870 – 17 March 1958) was an Irish Nationalist politician, and Member of Parliament (MP) in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and as member of the Irish Parliam ...

, who won the event, had been entered in the competition by a fellow-student of his at Oxford; the Greek, Konstantinos Manos. As a member of the Athens Lawn Tennis sub-committee, Manos had been trying, with the assistance of Boland, to recruit competitors for the Athens Games from among the sporting circles of Oxford University. In the first round, Boland defeated Friedrich Traun

Friedrich Adolf "Fritz" Traun (29 March 1876 – 11 July 1908) was a German athlete and tennis player. Born into a wealthy family, he participated in the 1896 Summer Olympics and won a gold medal in men's doubles. He committed suicide after ...

, a promising tennis player from Hamburg

Hamburg (, ; ), officially the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg,. is the List of cities in Germany by population, second-largest city in Germany after Berlin and List of cities in the European Union by population within city limits, 7th-lar ...

, who had been eliminated in the 100-meter sprint competition. Boland and Traun decided to team up for the doubles event, in which they reached the final and defeated their Greek opponents after losing the first set.

Weightlifting

The sport of weightlifting was still young in 1896, and the rules differed from those in use today. Competitions were held outdoors, in the infield of the main stadium, and there were no weight limits. The first event was held in a style now known as the "

The sport of weightlifting was still young in 1896, and the rules differed from those in use today. Competitions were held outdoors, in the infield of the main stadium, and there were no weight limits. The first event was held in a style now known as the "clean and jerk

The clean and jerk is a composite of two weightlifting movements, most often performed with a barbell: the clean and the jerk. During the ''clean'', the lifter moves the barbell from the floor to a racked position across the deltoids, without rest ...

". Two competitors stood out: Briton Launceston Elliot

Launceston Elliot (9 June 1874 – 8 August 1930) was a British weightlifter, and the first athlete representing the United Kingdom to become an Olympic champion.

Biography

Launceston Elliot was conceived in Launceston, Tasmania, Australia ...

and Viggo Jensen

Alexander Viggo Jensen (born 22 June 1874 in Copenhagen, Denmark; died 2 November 1930 in Copenhagen, Denmark) was a Danish weightlifter, sport shooter, gymnast, and athlete. He was the first Danish and Nordic Olympic champion, at the 1896 Sum ...

of Denmark. Both of them lifted the same weight, but the jury, with Prince George as the chairman, ruled that Jensen had done so in a better style. The British delegation, unfamiliar with this tie-breaking rule, lodged a protest. The lifters were eventually allowed to make further attempts, but neither lifter improved, and Jensen was declared the champion.Coubertin–Philemon–Politis–Anninos (1897), 70–71

Elliot got his revenge in the one hand lift event, which was held immediately after the two-handed one. Jensen had been slightly injured during his last two-handed attempt and was no match for Elliot, who won the competition easily. The Greek audience was charmed by the British victor, whom they considered very attractive. A curious incident occurred during the weightlifting event: a servant was ordered to remove the weights, which appeared to be a difficult task for him. Prince George came to his assistance; he picked up the weight and threw it a considerable distance with ease, to the delight of the crowd.

Wrestling

No weight classes existed for the wrestling competition, held in the Panathenaic Stadium, which meant that there would only be one winner among competitors of all sizes. The rules used were similar to modern

No weight classes existed for the wrestling competition, held in the Panathenaic Stadium, which meant that there would only be one winner among competitors of all sizes. The rules used were similar to modern Greco-Roman wrestling

Greco-Roman (American English), Graeco-Roman (British English), or classic wrestling (Euro-English) is a style of wrestling that is practiced worldwide. Greco-Roman wrestling was included in the first modern Olympic Games in 1896 and has been i ...

, although there was no time limit, and not all leg holds were forbidden (in contrast to current rules).

Apart from the two Greek contestants, all the competitors had previously been active in other sports. Weightlifting champion Launceston Elliot faced gymnastics champion Carl Schuhmann

Carl August Berthold Schuhmann (12 May 1869 – 24 March 1946) was a German athlete who won four Olympic titles in gymnastics and wrestling at the 1896 Summer Olympics in Athens, becoming the most successful athlete at the inaugural Olympics ...

. The latter won and advanced into the final, where he met Georgios Tsitas

Georgios Tsitas (, born 1872 in Smyrna, died between 1940 and 1945) was a Greek wrestler. He competed at the 1896 Summer Olympics in Athens.

In the first round of the wrestling competition, held in a roughly Greco-Roman format, Tsitas had a bye ...

, who had previously defeated Stephanos Christopoulos

Stephanos Christopoulos (; 1876) was a Greek wrestler. He was a member of Gymnastiki Etaireia Patron, that merged in 1923 with Panachaikos Gymnastikos syllogos to become Panachaiki Gymnastiki Enosi.

Christopoulos competed at the 1896 Summer Olym ...

. Darkness forced the final match to be suspended after 40 minutes; it was continued the following day, when Schuhmann needed only fifteen minutes to finish the bout.

Closing ceremony

On the morning of Sunday 12 April (or 31 March, according to the Julian calendar then used in Greece), King George organised a banquet for officials and athletes (even though some competitions had not yet been held). During his speech, he made clear that, as far as he was concerned, the Olympics should be held in Athens permanently. The official closing ceremony was held the following Wednesday after being postponed from Tuesday due to rain. Again, the royal family attended the ceremony, which was opened by the

On the morning of Sunday 12 April (or 31 March, according to the Julian calendar then used in Greece), King George organised a banquet for officials and athletes (even though some competitions had not yet been held). During his speech, he made clear that, as far as he was concerned, the Olympics should be held in Athens permanently. The official closing ceremony was held the following Wednesday after being postponed from Tuesday due to rain. Again, the royal family attended the ceremony, which was opened by the national anthem of Greece

The "Hymn to Liberty", also known as the "Hymn to Freedom", is a Greek poem written by Dionysios Solomos in 1823 and set to music by Nikolaos Mantzaros in 1828. Consisting of 158 stanzas in total, its two first stanzas officially became the nat ...

and an ode composed in ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

by George S. Robertson, a British athlete and scholar.

Afterwards, the king awarded prizes to the winners. Unlike today, the first-place winners received a silver medal, an olive

The olive, botanical name ''Olea europaea'' ("European olive"), is a species of Subtropics, subtropical evergreen tree in the Family (biology), family Oleaceae. Originating in Anatolia, Asia Minor, it is abundant throughout the Mediterranean ...

branch and a diploma, while runners-up received a copper medal, a laurel

Laurel may refer to:

Plants

* Lauraceae, the laurel family

* Laurel (plant), including a list of trees and plants known as laurel

People

* Laurel (given name), people with the given name

* Laurel (surname), people with the surname

* Laurel (mus ...

branch and a diploma.Coubertin–Philemon–Politis–Anninos (1897), 232–234 Third place winners did not receive a prize.

Some winners also received additional prizes, such as Spyridon Louis, who received a cup from Michel Bréal

Michel Jules Alfred Bréal (; 26 March 183225 November 1915), French philologist, was born at Landau in Rhenish Palatinate. He is often identified as a founder of modern semantics. He was also the creator of the modern marathon race, having pr ...

, a friend of Coubertin, who had conceived the marathon event. Louis then led the medalists on a lap of honour around the stadium, while the Olympic Hymn was played again. The King then formally announced that the first Olympiad was at an end and left the Stadium, while the band played the Greek national hymn and the crowd cheered.

Like the Greek king, many others supported the idea of holding the next Games in Athens; most of the American competitors signed a letter to the Crown Prince expressing this wish. Coubertin, however, was heavily opposed to this idea, as he envisioned international rotation as one of the cornerstones of the modern Olympics. According to his wish, the next Games were held in Paris, although they would be somewhat overshadowed by the concurrent Universal Exposition.

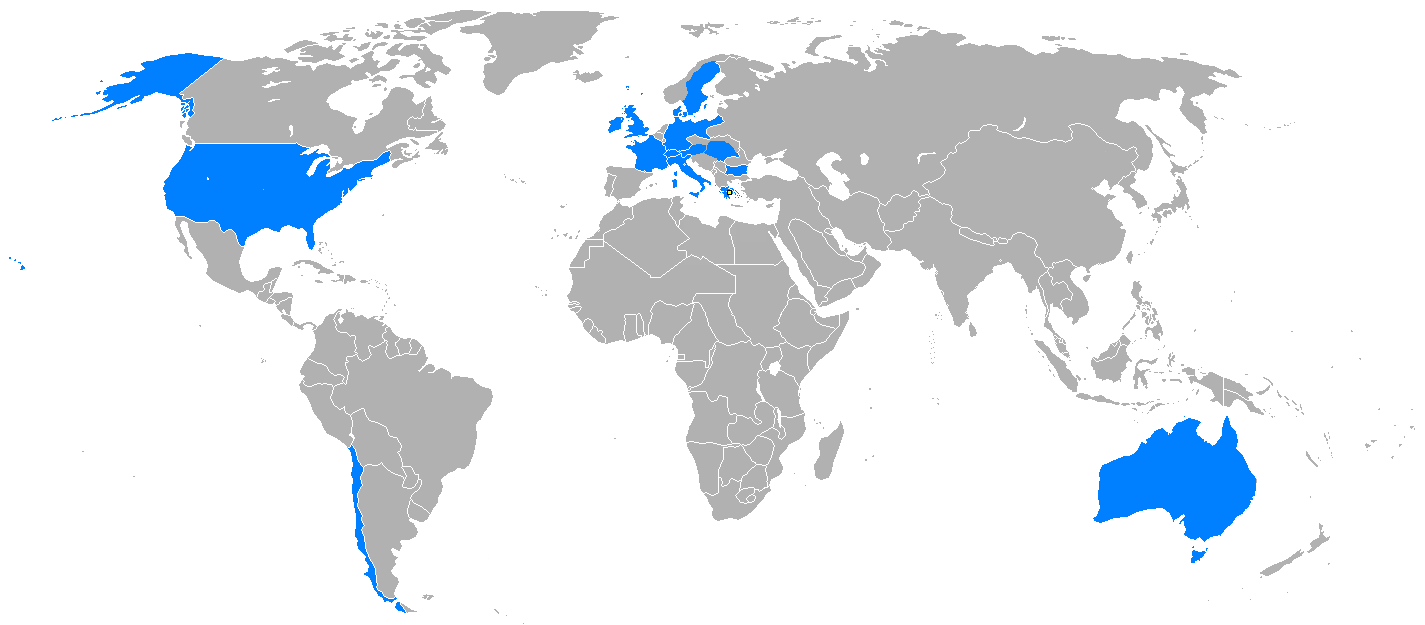

Participating nations

The concept of national teams was not a major part of the Olympic movement until the

The concept of national teams was not a major part of the Olympic movement until the Intercalated Games

The 1906 Intercalated Games or 1906 Olympic Games (), held from 22 April 1906 to 2 May 1906, was an international multi-sport event that was celebrated in Athens, Kingdom of Greece. They were at the time considered to be Olympic Games and were re ...

10 years later, though many sources list the nationality of competitors in 1896 and give medal counts. There are significant conflicts with regard to which nations competed. The International Olympic Committee gives a figure of 14, but does not list them. The following 14 are most likely the ones recognised by the IOC. Olympedia lists 13, excluding Chile; other sources list 12, excluding Chile and Bulgaria; others list 13, including those two but excluding Italy. Egypt is also sometimes included because of the participation of Dimitrios Kasdaglis, a Greek national who resided in Alexandria after living in Great Britain for years. Belgium and Russia had entered the names of competitors but withdrew.

Number of athletes by National Olympic Committees

National Olympic Committees did not yet exist. Over 65% of all athletes were Greek.Medal count