Alchemical Earth Symbol (fixed Width) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Alchemy (from the

Alchemy (from the

Alchemy (from the

Alchemy (from the Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

word , ) is an ancient branch of natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the develop ...

, a philosophical

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

and protoscientific

In the philosophy of science, protoscience is a research field that has the characteristics of an undeveloped science that may ultimately develop into an established science. Philosophers use protoscience to understand the history of science and d ...

tradition that was historically practised in China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

, India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

, the Muslim world

The terms Islamic world and Muslim world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs, politics, and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is ...

, and Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

. In its Western form, alchemy is first attested in a number of pseudepigraphical

A pseudepigraph (also anglicized as "pseudepigraphon") is a falsely attributed work, a text whose claimed author is not the true author, or a work whose real author attributed it to a figure of the past. The name of the author to whom the wor ...

texts written in Greco-Roman Egypt during the first few centuries AD.. Greek-speaking alchemists often referred to their craft as "the Art" (τέχνη) or "Knowledge" (ἐπιστήμη), and it was often characterised as mystic (μυστική), sacred (ἱɛρά), or divine (θɛíα).

Alchemists attempted to purify, mature, and perfect certain materials. Common aims were chrysopoeia

In alchemy, the term chrysopoeia () refers to the artificial production of gold, most commonly by the alleged transmutation of base metals such as lead.

A related term is argyropoeia (), referring to the artificial production of silver, often ...

, the transmutation of "base metal

A base metal is a common and inexpensive metal, as opposed to a precious metal such as gold or silver. In numismatics, coins often derived their value from the precious metal content; however, base metals have also been used in coins in the past ...

s" (e.g., lead

Lead () is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol Pb (from Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a Heavy metal (elements), heavy metal that is density, denser than most common materials. Lead is Mohs scale, soft and Ductility, malleabl ...

) into "noble metal

A noble metal is ordinarily regarded as a metallic chemical element, element that is generally resistant to corrosion and is usually found in nature in its native element, raw form. Gold, platinum, and the other platinum group metals (ruthenium ...

s" (particularly gold

Gold is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol Au (from Latin ) and atomic number 79. In its pure form, it is a brightness, bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile metal. Chemically, gold is a transition metal ...

); the creation of an elixir of immortality

The elixir of life (Medieval Latin: ' ), also known as elixir of immortality, is a potion that supposedly grants the drinker eternal life and/or eternal youth. This elixir was also said to cure all diseases. Alchemists in various ages and cu ...

; and the creation of panaceas able to cure any disease. The perfection of the human body and soul

The soul is the purported Mind–body dualism, immaterial aspect or essence of a Outline of life forms, living being. It is typically believed to be Immortality, immortal and to exist apart from the material world. The three main theories that ...

was thought to result from the alchemical ''magnum opus'' ("Great Work"). The concept of creating the philosophers' stone

The philosopher's stone is a mythic alchemical substance capable of turning base metals such as mercury into gold or silver; it was also known as "the tincture" and "the powder". Alchemists additionally believed that it could be used to mak ...

was variously connected with all of these projects.

Islamic and European alchemists developed a basic set of laboratory techniques

A laboratory (; ; colloquially lab) is a facility that provides controlled conditions in which scientific or technological research, experiments, and measurement may be performed. Laboratories are found in a variety of settings such as schools, u ...

, theories, and terms, some of which are still in use today. They did not abandon the Ancient Greek philosophical

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC. Philosophy was used to make sense of the world using reason. It dealt with a wide variety of subjects, including astronomy, epistemology, mathematics, political philosophy, ethics, metaphysics ...

idea that everything is composed of four elements

The classical elements typically refer to earth, water, air, fire, and (later) aether which were proposed to explain the nature and complexity of all matter in terms of simpler substances. Ancient cultures in Greece, Angola, Tibet, India, a ...

, and they tended to guard their work in secrecy, often making use of cyphers and cryptic symbolism. In Europe, the 12th-century translations of medieval Islamic works on science and the rediscovery of Aristotelian philosophy gave birth to a flourishing tradition of Latin alchemy. This late medieval tradition of alchemy would go on to play a significant role in the development of early modern

The early modern period is a Periodization, historical period that is defined either as part of or as immediately preceding the modern period, with divisions based primarily on the history of Europe and the broader concept of modernity. There i ...

science (particularly chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a physical science within the natural sciences that studies the chemical elements that make up matter and chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules a ...

and medicine

Medicine is the science and Praxis (process), practice of caring for patients, managing the Medical diagnosis, diagnosis, prognosis, Preventive medicine, prevention, therapy, treatment, Palliative care, palliation of their injury or disease, ...

).

Modern discussions of alchemy are generally split into an examination of its exoteric

{{Short pages monitor

The introduction of alchemy to Latin Europe may be dated to 11 February 1144, with the completion of

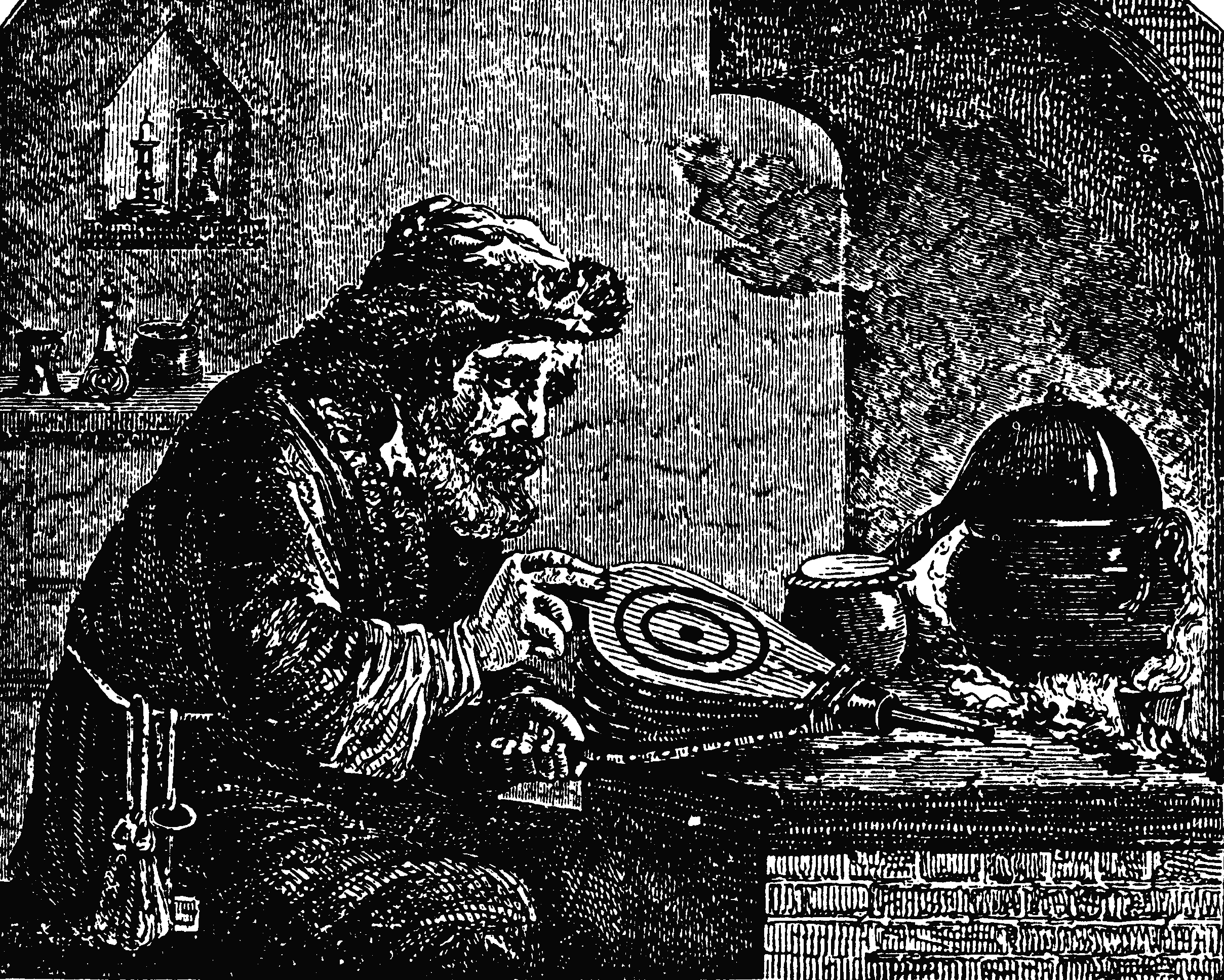

Although most of these appointments were legitimate, the trend of pseudo-alchemical fraud continued through the Renaissance. ''Betrüger'' would use sleight of hand, or claims of secret knowledge to make money or secure patronage. Legitimate mystical and medical alchemists such as

Although most of these appointments were legitimate, the trend of pseudo-alchemical fraud continued through the Renaissance. ''Betrüger'' would use sleight of hand, or claims of secret knowledge to make money or secure patronage. Legitimate mystical and medical alchemists such as

The decline of European alchemy was brought about by the rise of modern science with its emphasis on rigorous quantitative experimentation and its disdain for "ancient wisdom". Although the seeds of these events were planted as early as the 17th century, alchemy still flourished for some two hundred years, and in fact may have reached its peak in the 18th century. As late as 1781 James Price claimed to have produced a powder that could transmute mercury into silver or gold. Early modern European alchemy continued to exhibit a diversity of theories, practices, and purposes: "Scholastic and anti-Aristotelian, Paracelsian and anti-Paracelsian, Hermetic, Neoplatonic, mechanistic, vitalistic, and more—plus virtually every combination and compromise thereof."

The decline of European alchemy was brought about by the rise of modern science with its emphasis on rigorous quantitative experimentation and its disdain for "ancient wisdom". Although the seeds of these events were planted as early as the 17th century, alchemy still flourished for some two hundred years, and in fact may have reached its peak in the 18th century. As late as 1781 James Price claimed to have produced a powder that could transmute mercury into silver or gold. Early modern European alchemy continued to exhibit a diversity of theories, practices, and purposes: "Scholastic and anti-Aristotelian, Paracelsian and anti-Paracelsian, Hermetic, Neoplatonic, mechanistic, vitalistic, and more—plus virtually every combination and compromise thereof."

Robert of Chester

Robert of Chester (Latin: ''Robertus Castrensis'') was an English Arabist of the 12th century. He translated several historically important books from Arabic to Latin, such as:

* ''Book on the Composition of Alchemy'' (): translated in 1144, thi ...

's translation of the ("Book on the Composition of Alchemy") from an Arabic work attributed to Khalid ibn Yazid

Khālid ibn Yazīd (full name ''Abū Hāshim Khālid ibn Yazīd ibn Muʿāwiya ibn Abī Sufyān'', ), 668–704 or 709, was an Umayyad prince and purported alchemist.

As a son of the Umayyad caliph Yazid I, Khalid was supposed to become ca ...

. Although European craftsmen and technicians pre-existed, Robert notes in his preface that alchemy (here still referring to the elixir

An elixir is a sweet liquid used for medical purposes, to be taken orally and intended to cure one's illness. When used as a dosage form, pharmaceutical preparation, an elixir contains at least one active ingredient designed to be taken orall ...

rather than to the art itself) was unknown in Latin Europe at the time of his writing. The translation of Arabic texts concerning numerous disciplines including alchemy flourished in 12th-century Toledo, Spain

Toledo ( ; ) is a city and Municipalities of Spain, municipality of Spain, the capital of the province of Toledo and the ''de jure'' seat of the government and parliament of the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Castilla� ...

, through contributors like Gerard of Cremona

Gerard of Cremona (Latin: ''Gerardus Cremonensis''; c. 1114 – 1187) was an Italians, Italian translator of scientific books from Arabic into Latin. He worked in Toledo, Spain, Toledo, Kingdom of Castile and obtained the Arabic books in the libr ...

and Adelard of Bath

Adelard of Bath (; 1080? 1142–1152?) was a 12th-century English natural philosopher. He is known both for his original works and for translating many important Greek scientific works of astrology, astronomy, philosophy, alchemy and mathemat ...

. Translations of the time included the Turba Philosophorum, and the works of Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( – 22 June 1037), commonly known in the West as Avicenna ( ), was a preeminent philosopher and physician of the Muslim world, flourishing during the Islamic Golden Age, serving in the courts of various Iranian peoples, Iranian ...

and Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi

Abū Bakr al-Rāzī, also known as Rhazes (full name: ), , was a Persian physician, philosopher and alchemist who lived during the Islamic Golden Age. He is widely regarded as one of the most important figures in the history of medicine, and a ...

. These brought with them many new words to the European vocabulary for which there was no previous Latin equivalent. Alcohol, carboy

A carboy, also known as a demijohn or a lady jeanne, is a rigid container with a typical capacity of . Carboys are primarily used for transporting liquids, often drinking water or chemicals.

They are also used for in-home fermentation of bev ...

, elixir

An elixir is a sweet liquid used for medical purposes, to be taken orally and intended to cure one's illness. When used as a dosage form, pharmaceutical preparation, an elixir contains at least one active ingredient designed to be taken orall ...

, and athanor are examples.

Meanwhile, theologian contemporaries of the translators made strides towards the reconciliation of faith and experimental rationalism, thereby priming Europe for the influx of alchemical thought. The 11th-century St Anselm put forth the opinion that faith and rationalism were compatible and encouraged rationalism in a Christian context. In the early 12th century, Peter Abelard

Peter Abelard (12 February 1079 – 21 April 1142) was a medieval French scholastic philosopher, leading logician, theologian, teacher, musician, composer, and poet. This source has a detailed description of his philosophical work.

In philos ...

followed Anselm's work, laying down the foundation for acceptance of Aristotelian thought before the first works of Aristotle had reached the West. In the early 13th century, Robert Grosseteste

Robert Grosseteste ( ; ; 8 or 9 October 1253), also known as Robert Greathead or Robert of Lincoln, was an Kingdom of England, English statesman, scholasticism, scholastic philosopher, theologian, scientist and Bishop of Lincoln. He was born of ...

used Abelard's methods of analysis and added the use of observation, experimentation, and conclusions when conducting scientific investigations. Grosseteste also did much work to reconcile Platonic and Aristotelian thinking.

Through much of the 12th and 13th centuries, alchemical knowledge in Europe remained centered on translations, and new Latin contributions were not made. The efforts of the translators were succeeded by that of the encyclopaedists. In the 13th century, Albertus Magnus

Albertus Magnus ( 1200 – 15 November 1280), also known as Saint Albert the Great, Albert of Swabia, Albert von Bollstadt, or Albert of Cologne, was a German Dominican friar, philosopher, scientist, and bishop, considered one of the great ...

and Roger Bacon

Roger Bacon (; or ', also '' Rogerus''; ), also known by the Scholastic accolades, scholastic accolade ''Doctor Mirabilis'', was a medieval English polymath, philosopher, scientist, theologian and Franciscans, Franciscan friar who placed co ...

were the most notable of these, their work summarizing and explaining the newly imported alchemical knowledge in Aristotelian terms. Albertus Magnus, a Dominican friar

The Order of Preachers (, abbreviated OP), commonly known as the Dominican Order, is a Catholic mendicant order of pontifical right that was founded in France by a Castilian priest named Dominic de Guzmán. It was approved by Pope Honorius ...

, is known to have written works such as the ''Book of Minerals'' where he observed and commented on the operations and theories of alchemical authorities like Hermes Trismegistus

Hermes Trismegistus (from , "Hermes the Thrice-Greatest") is a legendary Hellenistic period figure that originated as a syncretic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth.A survey of the literary and archaeological eviden ...

, pseudo-Democritus

Pseudo-Democritus is the name used by scholars for the anonymous authors of a number of Greek writings that were falsely attributed to the pre-Socratic philosopher Democritus ( 460–370 BC).

Several of these writings, most notably the ...

and unnamed alchemists of his time. Albertus critically compared these to the writings of Aristotle and Avicenna, where they concerned the transmutation of metals. From the time shortly after his death through to the 15th century, more than 28 alchemical tracts were misattributed to him, a common practice giving rise to his reputation as an accomplished alchemist. Likewise, alchemical texts have been attributed to Albert's student Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas ( ; ; – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest, the foremost Scholasticism, Scholastic thinker, as well as one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the W ...

.

Roger Bacon, a Franciscan friar

The Franciscans are a group of related organizations in the Catholic Church, founded or inspired by the Italian saint Francis of Assisi. They include three independent religious orders for men (the Order of Friars Minor being the largest contem ...

who wrote on a wide variety of topics including optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of optical instruments, instruments that use or Photodetector, detect it. Optics usually describes t ...

, comparative linguistics

Comparative linguistics is a branch of historical linguistics that is concerned with comparing languages to establish their historical relatedness.

Genetic relatedness implies a common origin or proto-language and comparative linguistics aim ...

, and medicine, composed his '' Great Work'' () for as part of a project towards rebuilding the medieval university

A medieval university was a corporation organized during the Middle Ages for the purposes of higher education. The first Western European institutions generally considered to be universities were established in present-day Italy, including the K ...

curriculum to include the new learning of his time. While alchemy was not more important to him than other sciences and he did not produce allegorical works on the topic, he did consider it and astrology to be important parts of both natural philosophy and theology and his contributions advanced alchemy's connections to soteriology

Soteriology (; ' "salvation" from wikt:σωτήρ, σωτήρ ' "savior, preserver" and wikt:λόγος, λόγος ' "study" or "word") is the study of Doctrine, religious doctrines of salvation. Salvation theory occupies a place of special sign ...

and Christian theology. Bacon's writings integrated morality, salvation, alchemy, and the prolongation of life. His correspondence with Clement highlighted this, noting the importance of alchemy to the papacy. Like the Greeks before him, Bacon acknowledged the division of alchemy into practical and theoretical spheres. He noted that the theoretical lay outside the scope of Aristotle, the natural philosophers, and all Latin writers of his time. The practical confirmed the theoretical, and Bacon advocated its uses in natural science and medicine. In later European legend, he became an archmage. In particular, along with Albertus Magnus, he was credited with the forging of a brazen head capable of answering its owner's questions.

Soon after Bacon, the influential work of Pseudo-Geber

Pseudo-Geber (or "Middle Latin, Latin pseudo-Geber") is the presumed author or group of authors responsible for a corpus of pseudepigraphic alchemical writings dating to the late 13th and early 14th centuries. These writings were falsely attrib ...

(sometimes identified as Paul of Taranto

Paul of Taranto was a 13th-century Franciscan alchemist and author from southern Italy. (Taranto is a city in Apulia.) Perhaps the best known of his works is his ''Theorica et practica'', which defends alchemical principles by describing the theo ...

) appeared. His ''Summa Perfectionis'' remained a staple summary of alchemical practice and theory through the medieval and renaissance periods. It was notable for its inclusion of practical chemical operations alongside sulphur-mercury theory, and the unusual clarity with which they were described. By the end of the 13th century, alchemy had developed into a fairly structured system of belief. Adepts believed in the macrocosm-microcosm theories of Hermes, that is to say, they believed that processes that affect minerals and other substances could have an effect on the human body (for example, if one could learn the secret of purifying gold, one could use the technique to purify the human soul

''Human Soul'' is an album by the English musician Graham Parker.

The album peaked at No. 165 on the ''Billboard'' 200. Parker supported the album by touring with Dave Edmunds's Rock and Roll Revue.

Production

''Human Soul'' was originally div ...

). They believed in the four elements and the four qualities as described above, and they had a strong tradition of cloaking their written ideas in a labyrinth of coded jargon

Jargon, or technical language, is the specialized terminology associated with a particular field or area of activity. Jargon is normally employed in a particular Context (language use), communicative context and may not be well understood outside ...

set with traps to mislead the uninitiated. Finally, the alchemists practised their art: they actively experimented with chemicals and made observation

Observation in the natural sciences is an act or instance of noticing or perceiving and the acquisition of information from a primary source. In living beings, observation employs the senses. In science, observation can also involve the percep ...

s and theories

A theory is a systematic and rational form of abstract thinking about a phenomenon, or the conclusions derived from such thinking. It involves contemplative and logical reasoning, often supported by processes such as observation, experimentation, ...

about how the universe operated. Their entire philosophy revolved around their belief that man's soul was divided within himself after the fall of Adam. By purifying the two parts of man's soul, man could be reunited with God.

In the 14th century, alchemy became more accessible to Europeans outside the confines of Latin-speaking churchmen and scholars. Alchemical discourse shifted from scholarly philosophical debate to an exposed social commentary on the alchemists themselves. Dante

Dante Alighieri (; most likely baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri; – September 14, 1321), widely known mononymously as Dante, was an Italian Italian poetry, poet, writer, and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called ...

, Piers Plowman

''Piers Plowman'' (written 1370–86; possibly ) or ''Visio Willelmi de Petro Ploughman'' (''William's Vision of Piers Plowman'') is a Middle English allegorical narrative poem by William Langland. It is written in un-rhymed, alliterative ...

, and Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer ( ; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for '' The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He ...

all painted unflattering pictures of alchemists as thieves and liars. Pope John XXII

Pope John XXII (, , ; 1244 – 4 December 1334), born Jacques Duèze (or d'Euse), was head of the Catholic Church from 7 August 1316 to his death, in December 1334. He was the second and longest-reigning Avignon Papacy, Avignon Pope, elected by ...

's 1317 edict, '' Spondent quas non-exhibent'' forbade the false promises of transmutation made by pseudo-alchemists. Roman Catholic Inquisitor General Nicholas Eymerich

Nicholas Eymerich () (Girona, ''c.'' 1316 – Girona, 4 January 1399) was a Roman Catholic theologian in Medieval Catalonia and Inquisitor General of the Inquisition in the Crown of Aragon in the later half of the 14th century. He is best known ...

's '' Directorium Inquisitorum'', written in 1376, associated alchemy with the performance of demonic rituals, which Eymerich differentiated from magic performed in accordance with scripture. This did not, however, lead to any change in the Inquisition's monitoring or prosecution of alchemists. In 1404, Henry IV of England banned the practice of multiplying metals by the passing of the ( 5 Hen. 4. c. 4) (although it was possible to buy a licence to attempt to make gold alchemically, and a number were granted by Henry VI and Edward IV). These critiques and regulations centered more around pseudo-alchemical charlatanism than the actual study of alchemy, which continued with an increasingly Christian tone. The 14th century saw the Christian imagery of death and resurrection employed in the alchemical texts of Petrus Bonus

Petrus Bonus (Latin for "Peter the Good"; ) was a late medieval alchemist. He is best known for his ''Precious Pearl'' () or ''Precious New Pearl'' ('), an influential alchemical text composed sometime between 1330 and 1339. He was said to have bee ...

, John of Rupescissa

:''Johannes de Rupescissa may also refer to Cardinal Jean de La Rochetaillée''

Jean de Roquetaillade, also known as John of Rupescissa, (ca. 1310 – between 1366 and 1370) was a French Franciscan alchemist and eschatologist.

Biography

...

, and in works written in the name of Raymond Lull and Arnold of Villanova.

Nicolas Flamel

Nicolas Flamel (; 1330 – 22 March 1418) was a French ''écrivain public'', a draftsman of public documents such as contracts, letters, agreements and requests. He and his wife also ran a school that taught this trade.

Long after his death, ...

is a well-known alchemist to the point where he had many pseudepigraphic

A pseudepigraph (also :wikt:anglicized, anglicized as "pseudepigraphon") is a false attribution, falsely attributed work, a text whose claimed author is not the true author, or a work whose real author attributed it to a figure of the past. Th ...

imitators. Although the historical Flamel existed, the writings and legends assigned to him only appeared in 1612.

A common idea in European alchemy in the medieval era was a metaphysical "Homer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

ic chain of wise men that link dheaven and earth" that included ancient pagan philosophers

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, value, mind, and language. It is a rational and critical inquiry that reflects on ...

and other important historical figures.

Renaissance and early modern Europe

During theRenaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

, Hermetic and Platonic foundations were restored to European alchemy. The dawn of medical, pharmaceutical, occult, and entrepreneurial branches of alchemy followed.

In the late 15th century, Marsilio Ficino

Marsilio Ficino (; Latin name: ; 19 October 1433 – 1 October 1499) was an Italian scholar and Catholic priest who was one of the most influential humanist philosophers of the early Italian Renaissance. He was an astrologer, a reviver of Neo ...

translated the Corpus Hermeticum

The is a collection of 17 Greek writings whose authorship is traditionally attributed to the legendary Hellenistic figure Hermes Trismegistus, a syncretic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth. The treatises were orig ...

and the works of Plato into Latin. These were previously unavailable to Europeans who for the first time had a full picture of the alchemical theory that Bacon had declared absent. Renaissance Humanism and Renaissance Neoplatonism guided alchemists away from physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

to refocus on mankind as the alchemical vessel.

Esoteric systems developed that blended alchemy into a broader occult Hermeticism, fusing it with magic, astrology, and Christian cabala. A key figure in this development was German Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa

Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim (; ; 14 September 1486 – 18 February 1535) was a German Renaissance polymath, physician, legal scholar, soldier, knight, theologian, and occult writer. Agrippa's ''Three Books of Occult Philosophy'' pub ...

(1486–1535), who received his Hermetic education in Italy in the schools of the humanists. In his ''De Occulta Philosophia'', he attempted to merge Kabbalah

Kabbalah or Qabalah ( ; , ; ) is an esoteric method, discipline and school of thought in Jewish mysticism. It forms the foundation of Mysticism, mystical religious interpretations within Judaism. A traditional Kabbalist is called a Mekubbal ...

, Hermeticism, and alchemy. He was instrumental in spreading this new blend of Hermeticism outside the borders of Italy.

Paracelsus

Paracelsus (; ; 1493 – 24 September 1541), born Theophrastus von Hohenheim (full name Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim), was a Swiss physician, alchemist, lay theologian, and philosopher of the German Renaissance.

H ...

(Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim, 1493–1541) cast alchemy into a new form, rejecting some of Agrippa's occultism and moving away from chrysopoeia

In alchemy, the term chrysopoeia () refers to the artificial production of gold, most commonly by the alleged transmutation of base metals such as lead.

A related term is argyropoeia (), referring to the artificial production of silver, often ...

. Paracelsus pioneered the use of chemicals and minerals in medicine and wrote, "Many have said of Alchemy, that it is for the making of gold and silver. For me such is not the aim, but to consider only what virtue and power may lie in medicines."

His hermetical views were that sickness and health in the body relied on the harmony of man the microcosm and Nature the macrocosm. He took an approach different from those before him, using this analogy not in the manner of soul-purification but in the manner that humans must have certain balances of minerals in their bodies, and that certain illnesses of the body had chemical remedies that could cure them. Iatrochemistry

Iatrochemistry (; also known as chemiatria or chemical medicine) is an archaic pre-scientific school of thought that was supplanted by modern chemistry and medicine. Having its roots in alchemy, iatrochemistry sought to provide chemical solutions ...

refers to the pharmaceutical applications of alchemy championed by Paracelsus.

John Dee

John Dee (13 July 1527 – 1608 or 1609) was an English mathematician, astronomer, teacher, astrologer, occultist, and alchemist. He was the court astronomer for, and advisor to, Elizabeth I, and spent much of his time on alchemy, divination, ...

(13 July 1527 – December 1608) followed Agrippa's occult tradition. Although better known for angel summoning, divination, and his role as astrologer

Astrology is a range of Divination, divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that propose that information about human affairs and terrestrial events may be discerned by studying the apparent positions ...

, cryptographer, and consultant to Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudor. Her eventful reign, and its effect on history ...

, Dee's alchemical ''Monas Hieroglyphica'', written in 1564 was his most popular and influential work. His writing portrayed alchemy as a sort of terrestrial astronomy in line with the Hermetic axiom ''As above so below''. During the 17th century, a short-lived "supernatural" interpretation of alchemy became popular, including support by fellows of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

: Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle (; 25 January 1627 – 31 December 1691) was an Anglo-Irish natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, Alchemy, alchemist and inventor. Boyle is largely regarded today as the first modern chemist, and therefore one of the foun ...

and Elias Ashmole

Elias Ashmole (23 May 1617 – 18 May 1692) was an English antiquary, politician, officer of arms, astrologer, freemason and student of alchemy. Ashmole supported the royalist side during the English Civil War, and at the restoration of Char ...

. Proponents of the supernatural interpretation of alchemy believed that the philosopher's stone might be used to summon and communicate with angels.

Entrepreneurial opportunities were common for the alchemists of Renaissance Europe. Alchemists were contracted by the elite for practical purposes related to mining, medical services, and the production of chemicals, medicines, metals, and gemstones. Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor

Rudolf II (18 July 1552 – 20 January 1612) was Holy Roman Emperor (1576–1612), King of Hungary and Kingdom of Croatia (Habsburg), Croatia (as Rudolf I, 1572–1608), King of Bohemia (1575–1608/1611) and Archduke of Austria (1576–16 ...

, in the late 16th century, famously received and sponsored various alchemists at his court in Prague, including Dee and his associate Edward Kelley

Sir Edward Kelley or Kelly, also known as Edward Talbot (; 1 August 1555 – 1597/8), was an English Renaissance occultist and scryer. He is known for working with John Dee in his magical investigations. Besides the professed ability to se ...

. King James IV of Scotland

James IV (17 March 1473 – 9 September 1513) was King of Scotland from 11 June 1488 until his death at the Battle of Flodden in 1513. He inherited the throne at the age of fifteen on the death of his father, James III, at the Battle of Sauch ...

, Julius, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg

Julius of Brunswick-Lüneburg (also known as Julius of Braunschweig; 29 June 1528 – 3 May 1589), a member of the House of Welf, was Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg and ruling List of rulers of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, ...

, Henry V, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg

Henry V of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (; 10 November 1489 – 11 June 1568), called the Younger, (''Heinrich der Jüngere''), a member of the House of Welf, was Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg and ruling Prince of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel from 1514 until ...

, Augustus, Elector of Saxony

Augustus (31 July 152611 February 1586) was Elector of Saxony from 1553 to 1586.

First years

Augustus was born in Freiberg, the youngest child and third (but second surviving) son of Henry IV, Duke of Saxony, and Catherine of Mecklenburg. He c ...

, Julius Echter von Mespelbrunn

Julius Echter von Mespelbrunn (18 March 1545 – 9 September 1617) was Prince-Bishop of Würzburg from 1573. He was born in Mespelbrunn Castle, Spessart (Lower Franconia) and died in Würzburg.

Life

Mespelbrunn was born the second so ...

, and Maurice, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel

Maurice of Hesse-Kassel (; 25 May 1572 – 15 March 1632), also called Maurice the Learned or Moritz, was the Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel (or Hesse-Cassel) in the Holy Roman Empire from 1592 to 1627.

Life

Maurice was born in Kassel as the son o ...

all contracted alchemists. John's son Arthur Dee

Arthur Dee (13 July 1579 – September or October 1651) was a physician and alchemist. He became a physician successively to Tsar Michael I of Russia and to King Charles I of England.

Youth

Dee was the eldest son of John Dee by his third wife ...

worked as a court physician to Michael I of Russia

Michael I (; ) was Tsar of all Russia from 1613 after being elected by the Zemsky Sobor of 1613 until his death in 1645. He was elected by the Zemsky Sobor and was the first tsar of the House of Romanov, which succeeded the Rurikids, House o ...

and Charles I of England

Charles I (19 November 1600 – 30 January 1649) was King of Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland, and Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland from 27 March 1625 until Execution of Charles I, his execution in 1649.

Charles was born ...

but also compiled the alchemical book ''Fasciculus Chemicus

''Fasciculus Chemicus'' or ''Chymical Collections. Expressing the Ingress, Progress, and Egress, of the Secret Hermetick Science out of the choicest and most famous authors'' is an anthology of alchemical writings compiled by Arthur Dee (1579� ...

''.

Michael Maier

Michael Maier (; 1568–1622) was a German physician and counsellor to Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor, Rudolf II Habsburg. He was a learned Alchemy, alchemist, epigramist, and amateur composer.

Early life

Maier was born in Rendsburg, Duchy of ...

and Heinrich Khunrath

Heinrich Khunrath (c. 1560 – 9 September 1605), or Dr. Henricus Khunrath as he was also called, was a German physician, hermetic philosopher, and alchemist. Frances Yates considered him to be a link between the philosophy of John Dee and Ro ...

wrote about fraudulent transmutations, distinguishing themselves from the con artist

A scam, or a confidence trick, is an attempt to defraud a person or group after first gaining their trust. Confidence tricks exploit victims using a combination of the victim's credulity, naivety, compassion, vanity, confidence, irresponsibi ...

s. False alchemists were sometimes prosecuted for fraud.

The terms "chemia" and "alchemia" were used as synonyms in the early modern period, and the differences between alchemy, chemistry and small-scale assaying and metallurgy were not as neat as in the present day. There were important overlaps between practitioners, and trying to classify them into alchemists, chemists and craftsmen is anachronistic. For example, Tycho Brahe

Tycho Brahe ( ; ; born Tyge Ottesen Brahe, ; 14 December 154624 October 1601), generally called Tycho for short, was a Danish astronomer of the Renaissance, known for his comprehensive and unprecedentedly accurate astronomical observations. He ...

(1546–1601), an alchemist better known for his astronomical

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest include ...

and astrological

Astrology is a range of divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that propose that information about human affairs and terrestrial events may be discerned by studying the apparent positions of celesti ...

investigations, had a laboratory built at his Uraniborg

Uraniborg was an astronomical observatory and alchemy laboratory established and operated by the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe. It was the first custom-built observatory in modern Europe, and the last to be built without a telescope as its pr ...

observatory/research institute. Michael Sendivogius

Michael Sendivogius (; ; 2 February 1566 – 1636) was a Polish alchemist, philosopher, and physician. A pioneer of chemistry, he developed ways of purifying and creating various acids, metals, and other chemicals.

He discovered that air is not ...

(''Michał Sędziwój'', 1566–1636), a Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Polish people, people from Poland or of Polish descent

* Polish chicken

* Polish brothers (Mark Polish and Michael Polish, born 1970), American twin ...

alchemist, philosopher, medical doctor and pioneer of chemistry wrote mystical works but is also credited with distilling oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

in a lab sometime around 1600. Sendivogious taught his technique to Cornelius Drebbel

Cornelis Jacobszoon Drebbel (; 1572 – 7 November 1633) was a Dutch engineer and inventor. He was the builder of the first operational submarine in 1620 and an innovator who contributed to the development of measurement and control systems, opti ...

who, in 1621, applied this in a submarine. Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

devoted considerably more of his writing to the study of alchemy (see Isaac Newton's occult studies

English physicist and mathematician Isaac Newton produced works exploring chronology, and biblical interpretation (especially of the Apocalypse), and alchemy. Some of this could be considered occult. Newton's scientific work may have been of l ...

) than he did to either optics or physics. Other early modern alchemists who were eminent in their other studies include Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle (; 25 January 1627 – 31 December 1691) was an Anglo-Irish natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, Alchemy, alchemist and inventor. Boyle is largely regarded today as the first modern chemist, and therefore one of the foun ...

, and Jan Baptist van Helmont

Jan Baptist van Helmont ( , ; 12 January 1580 – 30 December 1644) was a chemist, physiologist, and physician from Brussels. He worked during the years just after Paracelsus and the rise of iatrochemistry, and is sometimes considered to be ...

. Their Hermeticism complemented rather than precluded their practical achievements in medicine and science.

Later modern period

The decline of European alchemy was brought about by the rise of modern science with its emphasis on rigorous quantitative experimentation and its disdain for "ancient wisdom". Although the seeds of these events were planted as early as the 17th century, alchemy still flourished for some two hundred years, and in fact may have reached its peak in the 18th century. As late as 1781 James Price claimed to have produced a powder that could transmute mercury into silver or gold. Early modern European alchemy continued to exhibit a diversity of theories, practices, and purposes: "Scholastic and anti-Aristotelian, Paracelsian and anti-Paracelsian, Hermetic, Neoplatonic, mechanistic, vitalistic, and more—plus virtually every combination and compromise thereof."

The decline of European alchemy was brought about by the rise of modern science with its emphasis on rigorous quantitative experimentation and its disdain for "ancient wisdom". Although the seeds of these events were planted as early as the 17th century, alchemy still flourished for some two hundred years, and in fact may have reached its peak in the 18th century. As late as 1781 James Price claimed to have produced a powder that could transmute mercury into silver or gold. Early modern European alchemy continued to exhibit a diversity of theories, practices, and purposes: "Scholastic and anti-Aristotelian, Paracelsian and anti-Paracelsian, Hermetic, Neoplatonic, mechanistic, vitalistic, and more—plus virtually every combination and compromise thereof."

Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle (; 25 January 1627 – 31 December 1691) was an Anglo-Irish natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, Alchemy, alchemist and inventor. Boyle is largely regarded today as the first modern chemist, and therefore one of the foun ...

(1627–1691) pioneered the scientific method in chemical investigations. He assumed nothing in his experiments and compiled every piece of relevant data. Boyle would note the place in which the experiment was carried out, the wind characteristics, the position of the Sun and Moon, and the barometer reading, all just in case they proved to be relevant. This approach eventually led to the founding of modern chemistry in the 18th and 19th centuries, based on revolutionary discoveries and ideas of Lavoisier

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier ( ; ; 26 August 17438 May 1794),

CNRS (

CNRS (

John Dalton

John Dalton (; 5 or 6 September 1766 – 27 July 1844) was an English chemist, physicist and meteorologist. He introduced the atomic theory into chemistry. He also researched Color blindness, colour blindness; as a result, the umbrella term ...

.

Beginning around 1720, a rigid distinction began to be drawn for the first time between "alchemy" and "chemistry". By the 1740s, "alchemy" was now restricted to the realm of gold making, leading to the popular belief that alchemists were charlatans, and the tradition itself nothing more than a fraud. In order to protect the developing science of modern chemistry from the negative censure to which alchemy was being subjected, academic writers during the 18th-century scientific Enlightenment attempted to divorce and separate the "new" chemistry from the "old" practices of alchemy. This move was mostly successful, and the consequences of this continued into the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries.

During the occult revival of the early 19th century, alchemy received new attention as an occult science. The esoteric or occultist school that arose during the 19th century held the view that the substances and operations mentioned in alchemical literature are to be interpreted in a spiritual sense, less than as a practical tradition or protoscience. This interpretation claimed that the obscure language of the alchemical texts, which 19th century practitioners were not always able to decipher, were an allegorical guise for spiritual, moral or mystical processes.

Two seminal figures during this period were Mary Anne Atwood

Mary Anne Atwood (née South) (1817 – 1910) was an English writer on hermeticism and spiritual alchemy.

Atwood was born in Dieppe, France but grew up in Gosport, Hampshire. Her father, Thomas South, was a researcher into the history of spiri ...

and Ethan Allen Hitchcock, who independently published similar works regarding spiritual alchemy. Both rebuffed the growing successes of chemistry, developing a completely esoteric view of alchemy. Atwood wrote: "No modern art or chemistry, notwithstanding all its surreptitious claims, has any thing in common with Alchemy." Atwood's work influenced subsequent authors of the occult revival including Eliphas Levi Eliphaz is one of Esau's sons in the Bible.

Eliphaz or Eliphas may also refer to:

* Eliphaz (Job), another person in the Bible

* Eliphaz Dow (1705–1755), first male executed in New Hampshire

* Eliphaz Fay (1797–1854), fourth president of Wate ...

, Arthur Edward Waite

Arthur Edward Waite (2 October 1857 – 19 May 1942) was a British poet and scholarly Mysticism, mystic who wrote extensively on occult and Western esotericism, esoteric matters, and was the co-creator of the Rider–Waite Tarot (also called th ...

, and Rudolf Steiner

Rudolf Joseph Lorenz Steiner (; 27 or 25 February 1861 – 30 March 1925) was an Austrian occultist, social reformer, architect, esotericist, and claimed clairvoyant. Steiner gained initial recognition at the end of the nineteenth century ...

. Hitchcock, in his ''Remarks Upon Alchymists'' (1855) attempted to make a case for his spiritual interpretation with his claim that the alchemists wrote about a spiritual discipline under a materialistic guise in order to avoid accusations of blasphemy from the church and state. In 1845, Baron Carl Reichenbach

Karl Ludwig Freiherr von Reichenbach (; February 12, 1788January 19, 1869), known as Carl Reichenbach, was a German chemist, geologist, metallurgist, naturalist, industrialist and philosopher, and a member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences. He ...

, published his studies on Odic force

Odic force (also called Od , Odyle, Önd, Odes, Odylic, Odyllic, or Odems) was a hypothetical vital energy or life force believed by some in the mid-19th century. The name was coined by Baron Carl von Reichenbach in 1845 in reference to the G ...

, a concept with some similarities to alchemy, but his research did not enter the mainstream of scientific discussion.

In 1946, Louis Cattiaux published the Message Retrouvé, a work that was at once philosophical, mystical and highly influenced by alchemy. In his lineage, many researchers, including Emmanuel and Charles d'Hooghvorst, are updating alchemical studies in France and Belgium.

Women

Several women appear in the earliest history of alchemy.Michael Maier

Michael Maier (; 1568–1622) was a German physician and counsellor to Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor, Rudolf II Habsburg. He was a learned Alchemy, alchemist, epigramist, and amateur composer.

Early life

Maier was born in Rendsburg, Duchy of ...

names four women who were able to make the philosophers' stone: Mary the Jewess

Mary or Maria the Jewess (), also known as Mary the Prophetess () or Maria the Copt (), was an early alchemist known from the works of Zosimos of Panopolis () and other authors in the Greek alchemical tradition. On the basis of Zosimos's commen ...

, Cleopatra the Alchemist

Cleopatra the Alchemist (Greek: Κλεοπάτρα; fl. ) was a Greek alchemist, writer, and philosopher. She experimented with practical alchemy but is also credited as one of the four female alchemists who could produce the philosopher's stone ...

, Medera, and Taphnutia. Zosimos's sister Theosebia (later known as Euthica the Arab) and Isis the Prophetess also played roles in early alchemical texts.

The first alchemist whose name we know was Mary the Jewess (). Early sources claim that Mary (or Maria) devised a number of improvements to alchemical equipment and tools as well as novel techniques in chemistry. Her best known advances were in heating and distillation processes. The laboratory water-bath, known eponymously (especially in France) as the bain-marie

A bain-marie ( , ), also known as a water bath or double boiler, a type of heated bath, is a piece of equipment used in science, Industry (manufacturing), industry, and cooking to heat materials gently or to keep materials warm over a period of ...

, is said to have been invented or at least improved by her. Essentially a double-boiler, it was (and is) used in chemistry for processes that required gentle heating. The tribikos (a modified distillation apparatus) and the kerotakis (a more intricate apparatus used especially for sublimations) are two other advancements in the process of distillation that are credited to her. Although we have no writing from Mary herself, she is known from the early-fourth-century writings of Zosimos of Panopolis

Zosimos of Panopolis (; also known by the Latin name Zosimus Alchemista, i.e. "Zosimus the Alchemist") was an alchemist and Gnostic mystic. He was born in Panopolis (present day Akhmim, in the south of Roman Egypt), and likely flourished ca. 3 ...

. After the Greco-Roman period, women's names appear less frequently in alchemical literature.

Towards the end of the Middle Ages and beginning of the Renaissance, due to the emergence of print, women were able to access the alchemical knowledge from texts of the preceding centuries. Caterina Sforza

Caterina Sforza (1463 – 28 May 1509) was an Italian noblewoman, the Countess of Forlì and Lady of Imola, firstly with her husband Girolamo Riario, and after his death as a regent of her son Ottaviano.

The descendant of a dynasty of noted co ...

, the Countess of Forlì and Lady of Imola, is one of the few confirmed female alchemists after Mary the Jewess. As she owned an apothecary, she would practice science and conduct experiments in her botanic gardens and laboratories. Being knowledgeable in alchemy and pharmacology, she recorded all of her alchemical ventures in a manuscript named ('Experiments'). The manuscript contained more than four hundred recipes covering alchemy as well as cosmetics and medicine. One of these recipes was for the water of talc. Talc

Talc, or talcum, is a clay mineral composed of hydrated magnesium silicate, with the chemical formula . Talc in powdered form, often combined with corn starch, is used as baby powder. This mineral is used as a thickening agent and lubricant ...

, which makes up talcum powder, is a mineral which, when combined with water and distilled, was said to produce a solution which yielded many benefits. These supposed benefits included turning silver to gold and rejuvenation. When combined with white wine, its powder form could be ingested to counteract poison. Furthermore, if that powder was mixed and drunk with white wine, it was said to be a source of protection from any poison, sickness, or plague. Other recipes were for making hair dyes, lotions, lip colours. There was also information on how to treat a variety of ailments from fevers and coughs to epilepsy and cancer. In addition, there were instructions on producing the quintessence (or aether

Aether, æther or ether may refer to:

Historical science and mythology

* Aether (mythology), the personification of the bright upper sky

* Aether (classical element), the material believed to fill the universe above the terrestrial sphere

** A ...

), an elixir which was believed to be able to heal all sicknesses, defend against diseases, and perpetuate youthfulness. She also wrote about creating the illustrious philosophers' stone

The philosopher's stone is a mythic alchemical substance capable of turning base metals such as mercury into gold or silver; it was also known as "the tincture" and "the powder". Alchemists additionally believed that it could be used to mak ...

.

Some women known for their interest in alchemy were Catherine de' Medici

Catherine de' Medici (, ; , ; 13 April 1519 – 5 January 1589) was an Italian Republic of Florence, Florentine noblewoman of the Medici family and Queen of France from 1547 to 1559 by marriage to Henry II of France, King Henry II. Sh ...

, the Queen of France, and Marie de' Medici

Marie de' Medici (; ; 26 April 1575 – 3 July 1642) was Queen of France and Navarre as the second wife of King Henry IV. Marie served as regent of France between 1610 and 1617 during the minority of her son Louis XIII. Her mandate as rege ...

, the following Queen of France, who carried out experiments in her personal laboratory. Also, Isabella d'Este

Isabella d'Este (19 May 1474 – 13 February 1539) was the Marchioness of Mantua and one of the leading women of the Italian Renaissance as a major cultural and political figure.

She was a patron of the arts as well as a leader of fashion ...

, the Marchioness of Mantua, made perfumes herself to serve as gifts. Due to the proliferation in alchemical literature of pseudepigrapha

A pseudepigraph (also :wikt:anglicized, anglicized as "pseudepigraphon") is a false attribution, falsely attributed work, a text whose claimed author is not the true author, or a work whose real author attributed it to a figure of the past. Th ...

and anonymous works, however, it is difficult to know which of the alchemists were actually women. This contributed to a broader pattern in which male authors credited prominent noblewomen for beauty products with the purpose of appealing to a female audience. For example, in ("Gallant Recipe-Book"), the distillation of lemons and roses was attributed to Elisabetta Gonzaga

Elisabetta Gonzaga (1471–1526) was a noblewoman of the Italian Renaissance, the Duchess of Urbino by marriage to Duke Guidobaldo da Montefeltro. Because her husband was impotent, Elisabetta never had children of her own, but adopted her husban ...

, the duchess of Urbino. In the same book, Isabella d'Aragona, the daughter of Alfonso II of Naples, is accredited for recipes involving alum

An alum () is a type of chemical compound, usually a hydrated double salt, double sulfate salt (chemistry), salt of aluminium with the general chemical formula, formula , such that is a valence (chemistry), monovalent cation such as potassium ...

and mercury. Ippolita Maria Sforza

Ippolita Maria Sforza (Jesi, 18 April 1445 – Naples, 19 August 1488) was an Italian noblewoman, a member of the Sforza family which ruled the Duchy of Milan from 1450 until 1535. She was the first wife of the Duke of Calabria, who later reigne ...

is even referred to in an anonymous manuscript about a hand lotion created with rose powder and crushed bones.

As the sixteenth century went on, scientific culture flourished and people began collecting "secrets". During this period "secrets" referred to experiments, and the most coveted ones were not those which were bizarre, but the ones which had been proven to yield the desired outcome. In this period, the only book of secrets ascribed to a woman was ('The Secrets of Signora Isabella Cortese'). This book contained information on how to turn base metals into gold, medicine, and cosmetics. However, it is rumoured that a man, Girolamo Ruscelli

Girolamo Ruscelli (1518–1566) was an Italian mathematician and Cartography, cartographer active in Venice during the early 16th century. He was also an alchemist, writing pseudonymously as Alessio Piemontese.

Biography

Girolamo Ruscelli w ...

, was the real author and only used a female voice to attract female readers.

In the nineteenth-century, Mary Anne Atwood

Mary Anne Atwood (née South) (1817 – 1910) was an English writer on hermeticism and spiritual alchemy.

Atwood was born in Dieppe, France but grew up in Gosport, Hampshire. Her father, Thomas South, was a researcher into the history of spiri ...

's ''A Suggestive Inquiry into the Hermetic Mystery'' (1850) marked the return of women during the occult revival.

Modern historical research

The history of alchemy has become a recognized subject of academic study. As the language of the alchemists is analysed, historians are becoming more aware of the connections between that discipline and other facets of Western cultural history, such as the evolution of science andphilosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

, the sociology and psychology of the intellectual communities, kabbalism

Kabbalah or Qabalah ( ; , ; ) is an esoteric method, discipline and school of thought in Jewish mysticism. It forms the foundation of Mysticism, mystical religious interpretations within Judaism. A traditional Kabbalist is called a Mekubbal ...

, spiritualism

Spiritualism may refer to:

* Spiritual church movement, a group of Spiritualist churches and denominations historically based in the African-American community

* Spiritualism (beliefs), a metaphysical belief that the world is made up of at leas ...

, Rosicrucianism

Rosicrucianism () is a spiritual and cultural movement that arose in early modern Europe in the early 17th century after the publication of several texts announcing to the world a new esoteric order. Rosicrucianism is symbolized by the Rose ...

, and other mystic movements. Institutions involved in this research include The Chymistry of Isaac Newton project at Indiana University

Indiana University (IU) is a state university system, system of Public university, public universities in the U.S. state of Indiana. The system has two core campuses, five regional campuses, and two regional centers under the administration o ...

, the University of Exeter

The University of Exeter is a research university in the West Country of England, with its main campus in Exeter, Devon. Its predecessor institutions, St Luke's College, Exeter School of Science, Exeter School of Art, and the Camborne School of ...

Centre for the Study of Esotericism (EXESESO), the European Society for the Study of Western Esotericism (ESSWE), and the University of Amsterdam

The University of Amsterdam (abbreviated as UvA, ) is a public university, public research university located in Amsterdam, Netherlands. Established in 1632 by municipal authorities, it is the fourth-oldest academic institution in the Netherlan ...

's Sub-department for the History of Hermetic Philosophy and Related Currents. A large collection of books on alchemy is kept in the Bibliotheca Philosophica Hermetica

Bibliotheca Philosophica Hermetica (BPH) or The Ritman Library is a Dutch library founded by Joost Ritman located in the Huis met de Hoofden (House with the Heads) at Keizersgracht 123, in the center of Amsterdam. The Bibliotheca Philosophica He ...

in Amsterdam.

Journals which publish regularly on the topic of Alchemy include ''Ambix

''Ambix'' is a peer-reviewed academic journal on the history of alchemy and chemistry; it was founded in 1936 and has appeared continuously from 1937 to the present, other than from 1939 to 1945 during World War II. It is currently published by the ...

'', published by the Society for the History of Alchemy and Chemistry {{short description, British academic society

The Society for the History of Alchemy and Chemistry, founded as the Society for the Study of Alchemy and Early Chemistry in 1935, holds biennial meetings and a yearly Graduate Workshop, publishes the ...

, and ''Isis

Isis was a major goddess in ancient Egyptian religion whose worship spread throughout the Greco-Roman world. Isis was first mentioned in the Old Kingdom () as one of the main characters of the Osiris myth, in which she resurrects her sla ...

'', published by the History of Science Society

The History of Science Society (HSS), founded in 1924, is the primary professional society for the academic study of the history of science. The society has over 3,000 members worldwide. It publishes the quarterly journal ''Isis'' and the yearly ...

.

Core concepts

Western alchemical theory corresponds to the worldview of late antiquity in which it was born. Concepts were imported fromNeoplatonism

Neoplatonism is a version of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a series of thinkers. Among the common id ...

and earlier Greek cosmology

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe, the cosmos. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', with the meaning of "a speaking of the wo ...

. As such, the classical element

The classical elements typically refer to Earth (classical element), earth, Water (classical element), water, Air (classical element), air, Fire (classical element), fire, and (later) Aether (classical element), aether which were proposed to ...

s appear in alchemical writings, as do the seven classical planet

A classical planet is an astronomical object that is visible to the naked eye and moves across the sky and its backdrop of fixed stars (the common stars which seem still in contrast to the planets), appearing as wandering stars. Visible to huma ...

s and the corresponding seven metals of antiquity

The metals of antiquity are the seven metals which humans had identified and found use for in prehistoric times in Africa, Europe and throughout Asia: gold, silver, copper, tin, lead, iron, and mercury (element), mercury.

Zinc, arsenic, and ant ...

. Similarly, the gods of the Roman pantheon

The Roman deities most widely known today are those the Romans identified with Interpretatio graeca, Greek counterparts, integrating Greek mythology, Greek myths, ancient Greek art, iconography, and sometimes Religion in ancient Greece, religio ...

who are associated with these luminaries are discussed in alchemical literature. The concepts of prima materia

In alchemy and philosophy, prima materia, materia prima or first matter (for a philosophical exposition refer to: Prime Matter), is the ubiquitous starting material required for the alchemical magnum opus and the creation of the philosopher' ...

and anima mundi

The concept of the (Latin), world soul (, ), or soul of the world (, ) posits an intrinsic connection between all living beings, suggesting that the world is animated by a soul much like the human body. Rooted in ancient Greek and Roman philo ...

are central to the theory of the philosopher's stone

The philosopher's stone is a mythic alchemical substance capable of turning base metals such as mercury into gold or silver; it was also known as "the tincture" and "the powder". Alchemists additionally believed that it could be used to mak ...

.

Magnum opus

The Great Work of Alchemy is often described as a series of four stages represented by colours. * ''nigredo

In alchemy, nigredo, or blackness, means putrefaction or decomposition. Many alchemists believed that as a first step in the pathway to the philosopher's stone, all alchemical ingredients had to be cleansed and cooked extensively to a uniform bla ...

'', a blackening or melanosis

* ''albedo

Albedo ( ; ) is the fraction of sunlight that is Diffuse reflection, diffusely reflected by a body. It is measured on a scale from 0 (corresponding to a black body that absorbs all incident radiation) to 1 (corresponding to a body that reflects ...

'', a whitening or leucosis

* ''citrinitas

Citrinitas, or sometimes xanthosis,Joseph Needham. ''Science & Civilisation in China: Chemistry and chemical technology. Spagyrical discovery and invention : magisteries of gold and immortality.'' Cambridge. 1974. p.23 is a term given by alchemis ...

'', a yellowing or xanthosis

* ''rubedo

Rubedo is a Latin word meaning "redness" that was adopted by alchemists to define the fourth and final major stage in their magnum opus. Both gold and the philosopher's stone were associated with the color red, as rubedo signaled alchemical succe ...

'', a reddening, purpling, or iosis

Modernity

Due to the complexity and obscurity of alchemical literature, and the 18th-century diffusion of remaining alchemical practitioners into the area ofchemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a physical science within the natural sciences that studies the chemical elements that make up matter and chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules a ...

, the general understanding of alchemy in the 19th and 20th centuries was influenced by several distinct and radically different interpretations. Those focusing on the exoteric

{{Short pages monitor