Zamia Integrifolia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Zamia integrifolia'', also known as coontie, is a small, tough, woody

/ref>

Indigenous tribes of

Indigenous tribes of

''Zamia'' species often produce more than one cone close to the tip of the stem or at the terminal of the caudex where it intersects with the aboveground stem. The cones, also called strobili, of ''Z. integrifolia'' are

''Zamia'' species often produce more than one cone close to the tip of the stem or at the terminal of the caudex where it intersects with the aboveground stem. The cones, also called strobili, of ''Z. integrifolia'' are

''Z. integrifolia'' plants are pollinated by a species of

''Z. integrifolia'' plants are pollinated by a species of

The Cycad Pages: ''Zamia integrifolia''

Flora of North America - ''Zamia integrifolia''

{{Taxonbar, from=Q3506489 integrifolia Flora of the Bahamas Flora of the Cayman Islands Flora of Cuba Flora of Florida Flora of Georgia (U.S. state) Plants described in 1789

cycad

Cycads are seed plants that typically have a stout and woody (ligneous) trunk (botany), trunk with a crown (botany), crown of large, hard, stiff, evergreen and (usually) pinnate leaves. The species are dioecious, that is, individual plants o ...

native to the southeastern United States

The Southeastern United States, also known as the American Southeast or simply the Southeast, is a geographical List of regions in the United States, region of the United States located in the eastern portion of the Southern United States and t ...

(in Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

and formerly in Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

), the Bahamas

The Bahamas, officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an archipelagic and island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the Atlantic Ocean. It contains 97 per cent of the archipelago's land area and 88 per cent of its population. ...

, Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

, the Cayman Islands

The Cayman Islands () is a self-governing British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory, and the largest by population. The territory comprises the three islands of Grand Cayman, Cayman Brac and Little Cayman, which are located so ...

, and Puerto Rico

; abbreviated PR), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, is a Government of Puerto Rico, self-governing Caribbean Geography of Puerto Rico, archipelago and island organized as an Territories of the United States, unincorporated territo ...

.

Description

''Z. integrifolia'' is a low-growing plant, with a trunk that grows to 3–25 cm high, but is often subterranean. Over time, it forms a multi-branched cluster, with a large, tuberous root system, which is actually an extension of the above-ground stems. The leaves can be completely lost during cold periods, with the plant lying dormant in its tuberous root system, allowing this cycad to be relatively cold hardy. The plant can survive up to USDA region 8b (10° to 20°F). The stems and leaves regenerate after the cold period subsides with full foliage. Like other cycads, ''Z. integrifolia'' isdioecious

Dioecy ( ; ; adj. dioecious, ) is a characteristic of certain species that have distinct unisexual individuals, each producing either male or female gametes, either directly (in animals) or indirectly (in seed plants). Dioecious reproduction is ...

, having male or female plants. The male cones are cylindrical, growing to 5–16 cm long; they are often clustered. The female cones are elongate-ovoid and grow to 5–19 cm long and 4–6 cm in diameter.

It produces reddish seed cones

In geometry, a cone is a three-dimensional figure that tapers smoothly from a flat base (typically a circle) to a point not contained in the base, called the ''apex'' or '' vertex''.

A cone is formed by a set of line segments, half-lines, ...

with a distinct acuminate tip. The leaves

A leaf (: leaves) is a principal appendage of the stem of a vascular plant, usually borne laterally above ground and specialized for photosynthesis. Leaves are collectively called foliage, as in "autumn foliage", while the leaves, stem, ...

are 20–100 cm long, with 5-30 pairs of leaflets (pinnae). Each leaflet is linear to lanceolate or oblong-obovate, 8–25 cm long and 0.5–2 cm broad, entire or with indistinct teeth at the tip. They are often revolute, with prickly petioles. It is similar in many respects to the closely related ''Z. pumila'', but that species differs in the more obvious toothing on the leaflets.Linnaeus, Carl von f. 1789. Hortus Kewensis 3: 478/ref>

Edibility and toxicity

Edibility

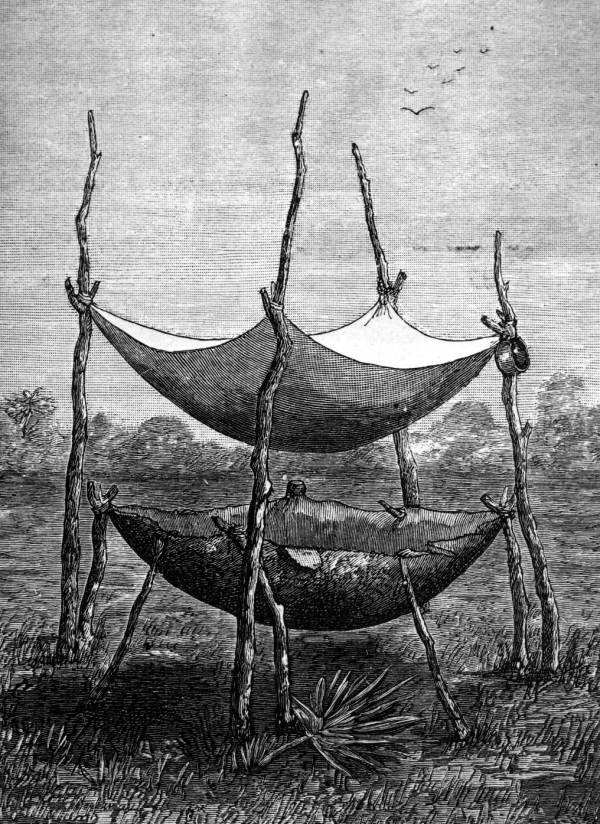

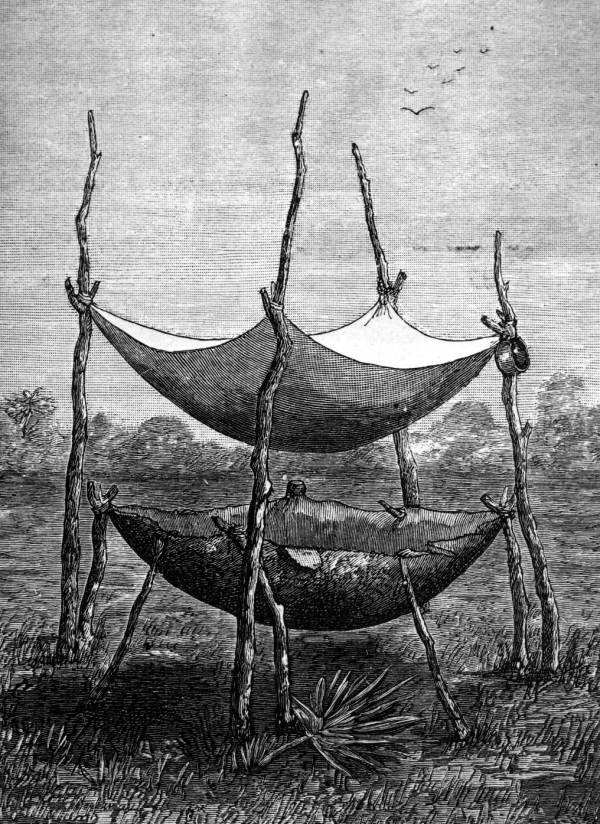

Indigenous tribes of

Indigenous tribes of Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

like the Seminoles

The Seminole are a Native American people who developed in Florida in the 18th century. Today, they live in Oklahoma and Florida, and comprise three federally recognized tribes: the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, ...

and Tequestas ground the root and soaked it overnight; afterwards, they rinsed it with running water for several hours to remove the rest of the water-soluble toxin cycasin. The resulting paste was then left to ferment before being dried into a powder. The resulting powder could then be used to make a bread-like substance. By the late 1880s, several mills in the Miami

Miami is a East Coast of the United States, coastal city in the U.S. state of Florida and the county seat of Miami-Dade County, Florida, Miami-Dade County in South Florida. It is the core of the Miami metropolitan area, which, with a populat ...

area started to produce Florida arrowroot

Florida arrowroot was the commercial name of an edible starch extracted from ''Zamia integrifolia'' (coontie), a small cycad native to North America.

Use

Like other cycads, ''Zamia integrifolia'' is poisonous, producing a toxin that affects the g ...

until their demise after World War 1

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

.

Seeds generally fall close to the parent plant, although about five percent of seeds are found more than four meters away. Some authors believe that birds and small mammals are responsible for that dispersal. While such behavior has not been observed, marks on seeds, and the location of seeds under shrubs where birds perch and small mammals shelter indicate that the seeds have been carried there. The size of the seeds probably restricts how far birds can carry seeds.

Toxicity

The whole plant, except for thesarcotesta

The sarcotesta is a fleshy seedcoat, a type of testa. Examples of seeds with a sarcotesta are pomegranate, ginkgo

''Ginkgo'' is a genus of non-flowering seed plants, assigned to the gymnosperms. The scientific name is also used as the Eng ...

, the pulpy covering of the seeds, is very toxic, containing a toxin called cycasin which can cause liver failure that can lead to death, but if proper precautions are taken it can be leached with water due to it being a water-soluble molecule. The seeds also contain a toxic glycoside

In chemistry, a glycoside is a molecule in which a sugar is bound to another functional group via a glycosidic bond. Glycosides play numerous important roles in living organisms. Many plants store chemicals in the form of inactive glycosides. ...

which causes headaches, vomiting, stomach pains and diarrhoea if ingested, and Beta-methylamino-alanine, which can cause central nervous system failure.

Common names

This plant has several common names. Two names,Florida arrowroot

Florida arrowroot was the commercial name of an edible starch extracted from ''Zamia integrifolia'' (coontie), a small cycad native to North America.

Use

Like other cycads, ''Zamia integrifolia'' is poisonous, producing a toxin that affects the g ...

and wild sago, refer to the former commercial use of this species as the source of an edible starch. Coontie (or koonti) is derived from the Seminole

The Seminole are a Native American people who developed in Florida in the 18th century. Today, they live in Oklahoma and Florida, and comprise three federally recognized tribes: the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, ...

Native American language ''conti hateka''. George J. F. Clarke, the surveyor general of East Florida

East Florida () was a colony of Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain from 1763 to 1783 and a province of the Spanish Empire from 1783 to 1821. The British gained control over Spanish Florida in 1763 as part of the Treaty of Paris (1763), Tre ...

during the Second Spanish period, wrote an article in 1823 for the St. Augustine newspaper at the time, the ''East Florida Herald'', which discussed, among other subjects, how the bulbous roots of coontie, which he called "comtee", could be used to make flour, thus anticipating the future commercial enterprise in Florida.

Distribution and habitat

''Z. integrifolia'' inhabits a variety of habitats with well-drained sands or sandyloam

Loam (in geology and soil science) is soil composed mostly of sand (particle size > ), silt (particle size > ), and a smaller amount of clay (particle size < ). By weight, its mineral composition is about 40–40–20% concentration of sand–si ...

soils. It prefers filtered sunlight to partial shade. In the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

populations are presently limited to Florida. It has been reported from extreme southeastern Georgia, but by the early 2010s could no longer be found there, and may be extinct in Georgia.

In the Bahamas

The Bahamas, officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic and island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the Atlantic Ocean. It contains 97 per cent of the archipelago's land area and 88 per cent of ...

, ''Z. integrifolia'' is found in Bahamian pine forests and Bahamian dry forests on the Abaco Islands

The Abaco Islands lie in the north of Bahamas, The Bahamas, about 193 miles (167.7 nautical miles or 310.6 km) east of Miami, Florida, US. The main islands are Great Abaco and Little Abaco, which is just west of Great Abaco's northern tip.

T ...

, where it is abundant, northern Andros

Andros (, ) is the northernmost island of the Greece, Greek Cyclades archipelago, about southeast of Euboea, and about north of Tinos. It is nearly long, and its greatest breadth is . It is for the most part mountainous, with many fruitful and ...

, where it is common, Grand Bahama

Grand Bahama is the northernmost of the islands of the Bahamas. It is the third largest island in the Bahamas island chain of approximately 700 islands and 2,400 cays. The island is roughly in area and approximately long west to east and at it ...

, where it is rare, and New Providence

New Providence is the most populous island in The Bahamas, containing more than 70% of the total population. On the eastern side of the island is the national capital, national capital city of Nassau, Bahamas, Nassau; it had a population of 246 ...

, where it is found in the few remaining unfragmented patches of pine forest. ''Z. integrifolia'' is also found in coastal thickets on Eleuthera

Eleuthera () refers both to a single island in the archipelagic state of the The Bahamas, Commonwealth of the Bahamas and to its associated group of smaller islands. Eleuthera forms a part of the Great Bahama Bank. The island of Eleuthera incor ...

and in sandy coastal scrub on Tilloo Cay. In the late 19th century, ''Zamia'' plants in the Bahamas were known as "bay rush", and were harvested on Andros and New Providence islands to produce starch.

''Z. integrifolia'' has also been found on the north-central coast of Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

, in the Cayman Islands

The Cayman Islands () is a self-governing British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory, and the largest by population. The territory comprises the three islands of Grand Cayman, Cayman Brac and Little Cayman, which are located so ...

, and in south-central Puerto Rico

; abbreviated PR), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, is a Government of Puerto Rico, self-governing Caribbean Geography of Puerto Rico, archipelago and island organized as an Territories of the United States, unincorporated territo ...

.

Studies by Calonje, et al. published in 2019, and Lindstrom, et al. in 2024, found that ''Z. integrifolia'' from Florida is a sister

A sister is a woman or a girl who shares parents or a parent with another individual; a female sibling. The male counterpart is a brother. Although the term typically refers to a familial relationship, it is sometimes used endearingly to ref ...

taxon to the rest of the Caribbean island species, while plants in Cuba (Calonje, et al.) and the Bahamas (Lindstom, et al.) are closely related to '' Z. angustifolia'' and '' Z. lucayana''.

Taxonomy

Thetype specimen

In biology, a type is a particular wikt:en:specimen, specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally associated. In other words, a type is an example that serves to ancho ...

of ''Z. integrifolia'' was a cultivated plant from East Florida

East Florida () was a colony of Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain from 1763 to 1783 and a province of the Spanish Empire from 1783 to 1821. The British gained control over Spanish Florida in 1763 as part of the Treaty of Paris (1763), Tre ...

, described by William Aiton

William Aiton (17312 February 1793) was a Scotland, Scottish botanist.

Aiton was born near Hamilton, Scotland, Hamilton. Having been regularly trained to the profession of a gardener, he travelled to London in 1754, and became assistant to Phi ...

at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew is a non-departmental public body in the United Kingdom sponsored by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. An internationally important botanical research and education institution, it employs 1,10 ...

. Andrew Turnbull, who founded the colony of New Smyrna in East Florida, sent a specimen of ''Zamia'' to Alexander Garden in Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the List of municipalities in South Carolina, most populous city in the U.S. state of South Carolina. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint of South Carolina's coastline on Charleston Harbor, an inlet of the Atla ...

, who in turn sent it to Aiton, and it thus may be the specimen described by Aiton.

Controversy has long existed over the classification of ''Zamia'' in Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

. Prior to the 1980s, several species were recognized in Florida, including ''Z. integrifolia'' ''Z. angustifolia'' var. ''floridana'', ''Z. floridana'', ''Z. silvicola'', and ''Z. umbrosa''. In 1983 Eckenwalder included all the ''Zamia'' populations in the Bahamas, the Caribbean, and Florida in a broadly defined ''Z. pumila'', but ''Z. integrifolia'' is now accepted as one of nine species in the ''Zamia pumila'' species complex.

The differences between populations cannot be explained by habitat variability. Studies conducted by Ward showed that five different Florida populations of ''Z. integrifolia'' with identical cultivation produced distinct leaf morphology, suggesting that there may be too much genetic diversity amongst these Floridian ''Z. integrifolia'', not to mention geographically isolated populations, to consider them a single species. Ward describes five varieties of ''Z. integrifolia'' in Florida:

* ''Z. integrifolia'' var. ''integrifolia'' - The variety first described as ''Z. integrifolia'' is common in central and southern Florida. Plants currently growing wild in the vicinity of New Smyrna Beach, the possible type site, have parallel-margined leaflets 13 to 14 cm long and about 13 mm wide. Populations of variety ''integrifolia'' generally have leaflet widths of 8 to 16 mm.

* ''Z. integrifolia'' var. ''umbrosa'' - Earlier designated as ''Z. umbrosa'', this variety is found in the upper eastern Florida peninsula. It has leaflets 3 to 7 mm wide, with slightly protruding vein tips or "teeth" near the apex of the leaflets. Ward argues that ''umbrosa'' is the variety most strongly differentiated from the common ''integrifolia'' variety.

* ''Z. integrifolia'' var. ''broomei'' - A variety found in the lower Suwannee River

The Suwannee River (also spelled Suwanee River or Swanee River) is a river that runs through south Georgia southward into Florida in the Southern United States. It is a wild blackwater river, about long.U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrog ...

valley, with leaflets 5 to 7 mm wide, and sparse foliage.

* ''Z. integrifolia'' var. ''floridana'' - A variety found on shell mounds on the west coast of the Florida peninsula. The female cones are up to 18 cm tall, and 8 cm in diameter, about twice as large as those on plants on the east coast of the Florida peninsula.

* ''Z. integrifolia'' var. ''silvicola'' - Found in the vicinity of Crystal River and in the Everglades

The Everglades is a natural region of flooded grasslands in the southern portion of the U.S. state of Florida, comprising the southern half of a large drainage basin within the Neotropical realm. The system begins near Orlando with the K ...

, this variety has leaflets 12 to 17 cm long and 10 to 15 mm wide.

Griffith et al. performed an analysis of the genetics of samples of ''Z. integrifolia'' from throughout its known range in Florida that supports the presence of only two varieties of ''Z. integrifolia'' in Florida, Ward's ''Z. integrifolia'' var. ''umbrosa'', and everything else, subsumed into ''Z. integrifolia'' var. ''integrifolia''. That study found much less genetic variation in ''Z. integrifolia'' than in other ''Zamia'' species across the Caribbean. Most of the local populations in Florida exhibit a recent population bottleneck

A population bottleneck or genetic bottleneck is a sharp reduction in the size of a population due to environmental events such as famines, earthquakes, floods, fires, disease, and droughts; or human activities such as genocide, speciocide, wid ...

. The authors attribute that to the overexploitation of ''Z. integrifolia'' for the production of starch in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

''Z. lucayana'', which has sometimes been listed as a synonym of ''Z. integrifolia'', is regarded as a valid species, restricted to Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated continental island in southeastern New York (state), New York state, extending into the Atlantic Ocean. It constitutes a significant share of the New York metropolitan area in both population and land are ...

in the Bahamas. While the ''floridana'' variety of ''Z. angustifolia'' has been synonymized to ''Z. integrifolia'', the species ''Z. angustifolia'', found in the Bahamas and Cuba, remains a valid species.

Two studies on the molecular phylogenetics

Molecular phylogenetics () is the branch of phylogeny that analyzes genetic, hereditary molecular differences, predominantly in DNA sequences, to gain information on an organism's evolutionary relationships. From these analyses, it is possible to ...

of ''Zamia'' have found that ''Z. integrifolia'' in Florida is sister

A sister is a woman or a girl who shares parents or a parent with another individual; a female sibling. The male counterpart is a brother. Although the term typically refers to a familial relationship, it is sometimes used endearingly to ref ...

to a clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

consisting of all of the zamias of the Bahamas and Caribbean islands. A 2019 study based on DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

found that ''Z. integrifolia'' from the Bahamas was more closely related to ''Z. angustifolia'' and ''Z. pygmaea'' than to ''Z. integrifolia'' from Florida, and that ''Z. integrifolia'' from Cuba was more closely related to ''Z. lucayana'' than to ''Z. integrifolia'' in Florida. A 2024 study based on transcriptome

The transcriptome is the set of all RNA transcripts, including coding and non-coding, in an individual or a population of cells. The term can also sometimes be used to refer to all RNAs, or just mRNA, depending on the particular experiment. The ...

s found that ''Z. intregrifolia'' from the Bahamas was more closely related to ''Z.angustifolia'' and ''Z. lucayana'' than to ''Z. integrifolia'' in Florida.

Ecology

Thelarvae

A larva (; : larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into their next life stage. Animals with indirect developmental biology, development such as insects, some arachnids, amphibians, or cnidarians typical ...

of the Atala butterfly (''Eumaeus atala''), as well as the larvae of several other species of ''Eumaeus'', feed exclusively on the leaves of Cycad plants. The larvae are gregarious and all life stages are aposematic

Aposematism is the Advertising in biology, advertising by an animal, whether terrestrial or marine, to potential predation, predators that it is not worth attacking or eating. This unprofitability may consist of any defenses which make the pr ...

, displaying coloration advertising the presence of poison. The larvae ingest cycasin (a carcinogen and neurotoxin) from ''Z. integrifolia'' leaves and retain it as adults. Both final instar

An instar (, from the Latin '' īnstar'' 'form, likeness') is a developmental stage of arthropods, such as insects, which occurs between each moult (''ecdysis'') until sexual maturity is reached. Arthropods must shed the exoskeleton in order to ...

larvae and adults have 0.6 to 0.9 mg of cycasin, while eggs, which are bright yellow, contain 220 to 270 μg

In the metric system, a microgram or microgramme is a Physical unit, unit of mass equal to one millionth () of a gram. The unit symbol is μg according to the International System of Units (SI); the recommended symbol in the United States and Uni ...

of cycasin.

Mealybug destroyers ('' Cryptolaemus montrouzieri''), are commonly found on ''Z. integrifolia''. They form a mutualistic relationship by providing the plant protection from pests in exchange for food. They feed on the coonties' natural enemies, scales and mealybugs, thereby reducing the need for pesticides.

Parasites

Three of the most common pests of ''Z. integrifolia'' are Florida red scales ('' Chrysomphalus aonidum''), hemispherical scales ('' Saissetia coffeae'') and longtailed mealybugs ('' Pseudococcus longispinus''). When infested, the plant's growth is stunted, and it becomes covered with blackish mold. Infestations are not limited to one species; several species can be found on the same plant.Nitrogen-fixation

Since ''Z. integrifolia'' is a cycad, which are the only group ofgymnosperm

The gymnosperms ( ; ) are a group of woody, perennial Seed plant, seed-producing plants, typically lacking the protective outer covering which surrounds the seeds in flowering plants, that include Pinophyta, conifers, cycads, Ginkgo, and gnetoph ...

s that form nitrogen-fixing associations, it depends on microbes as a source of nitrogen. It forms a symbiotic relationship with nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria ( ) are a group of autotrophic gram-negative bacteria that can obtain biological energy via oxygenic photosynthesis. The name "cyanobacteria" () refers to their bluish green (cyan) color, which forms the basis of cyanobacteri ...

, which live in specialized roots called coralloid roots and are green in color despite not actively photosynthesizing. The filamentous cyanobacteria belonging to the genus ''Nostoc

''Nostoc'', also known as star jelly, troll's butter, spit of moon, fallen star, witch's butter (not to be confused with the fungi commonly known as witches' butter), and witch's jelly, is the most common genus of cyanobacteria found in a variety ...

'', which is able to form symbiosis with a wide range of organisms, inhabits the mucilage in the microaerobic and dark intercellular zone in between the inner and outer cortex of coralloid roots. This zone is transversed and connected by elongated ''Zamia'' cells. Coralloid roots are just like lateral roots, but highly specialized to contain cyanobacteria.

Reproduction

''Zamia'' species often produce more than one cone close to the tip of the stem or at the terminal of the caudex where it intersects with the aboveground stem. The cones, also called strobili, of ''Z. integrifolia'' are

''Zamia'' species often produce more than one cone close to the tip of the stem or at the terminal of the caudex where it intersects with the aboveground stem. The cones, also called strobili, of ''Z. integrifolia'' are dioecious

Dioecy ( ; ; adj. dioecious, ) is a characteristic of certain species that have distinct unisexual individuals, each producing either male or female gametes, either directly (in animals) or indirectly (in seed plants). Dioecious reproduction is ...

. The male strobilus and the female strobilus are found on two separate plants. The cones on the female plant are thick and have red-orange seeds. They also have a velvety texture, and only grow up to 6 inches. On the other hand, the ones on the male plant are narrow and tall, and contain pollen. They can reach a length of 7 inches. Female cones are usually borne singularly, whereas male cones grow in groups or clusters. The growing season of ''Z. integrifolia'' is during the spring, and the sex of the plant is undetermined until cones are produced.

Multiple cones

The multiple cones of ''Z. integrifolia'' may develop through three methods: sympodium, forking of the bundle system, and adventitious buds. The most common form of development is the rapid formation of cone domes on the plant's sympodium, which is its main axis. More cones are present when there is a "branching" of the bundles to the cones. The forking of the bundle system starts near the base of a terminal cone, which remains erect, of the sympodial development in certain branches. The last method is when "adventitious buds appear in the cortical tissue closely connected with the stelar system of the trunk, and these buds continue their development like typical stems".Pollination

''Z. integrifolia'' plants are pollinated by a species of

''Z. integrifolia'' plants are pollinated by a species of weevil

Weevils are beetles belonging to the superfamily Curculionoidea, known for their elongated snouts. They are usually small – less than in length – and herbivorous. Approximately 97,000 species of weevils are known. They belong to several fa ...

, '' Rhopalotria slossoni'', and an erotylid beetle '' Pharaxonotha floridana''. ''P. floridana'' pollinates the plants by using the pollen-bearing strobili as food for its larvae, transporting the pollen with it. The plant may regulate the mutualistic interaction by making the seed-bearing strobilis poisonous to these larvae, as the toxin beta-N-methylamino-L-alanine is present in pollen-bearing strobili but is sequestered in idioblast cells that resist insect digestion, whereas the toxin is diffusely present in the female cones.

On the other hand, ''R. slossoni'' does not consume the pollen, but rather, takes shelter in male cones where they become dusted with pollen. They then carry over these pollen into the female cones, which becomes pollinated. Although the female cones are not consumed, there have been evidences of healed scars due to punctation in the interior of the cone, which are suspected to be caused by weevils.

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * *Further reading

*External links

The Cycad Pages: ''Zamia integrifolia''

Flora of North America - ''Zamia integrifolia''

{{Taxonbar, from=Q3506489 integrifolia Flora of the Bahamas Flora of the Cayman Islands Flora of Cuba Flora of Florida Flora of Georgia (U.S. state) Plants described in 1789