Zagreb Synagogue on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Zagreb Synagogue () was a former

The composition of the main facade, with its dominant drawn-out and elevated projection and the two symmetrical lower lateral parts, reflects the internal division into three

The composition of the main facade, with its dominant drawn-out and elevated projection and the two symmetrical lower lateral parts, reflects the internal division into three

With the new synagogue, an

With the new synagogue, an

The synagogue's eight valuable

The synagogue's eight valuable

Orthodox

Orthodox, Orthodoxy, or Orthodoxism may refer to:

Religion

* Orthodoxy, adherence to accepted norms, more specifically adherence to creeds, especially within Christianity and Judaism, but also less commonly in non-Abrahamic religions like Neo-pag ...

Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

congregation and synagogue

A synagogue, also called a shul or a temple, is a place of worship for Jews and Samaritans. It is a place for prayer (the main sanctuary and sometimes smaller chapels) where Jews attend religious services or special ceremonies such as wed ...

, located in Zagreb

Zagreb ( ) is the capital (political), capital and List of cities and towns in Croatia#List of cities and towns, largest city of Croatia. It is in the Northern Croatia, north of the country, along the Sava river, at the southern slopes of the ...

, in modern-day Croatia

Croatia, officially the Republic of Croatia, is a country in Central Europe, Central and Southeast Europe, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. It borders Slovenia to the northwest, Hungary to the northeast, Serbia to the east, Bosnia and Herze ...

. The synagogue building was constructed in 1867 in the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia

The Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia (; or ; ) was a nominally autonomous kingdom and constitutionally defined separate political nation within the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It was created in 1868 by merging the kingdoms of Kingdom of Croatia (Habs ...

within the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

, and was used until it was demolished by the Ustaše

The Ustaše (), also known by anglicised versions Ustasha or Ustashe, was a Croats, Croatian fascist and ultranationalist organization active, as one organization, between 1929 and 1945, formally known as the Ustaša – Croatian Revolutionar ...

fascist

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural soci ...

authorities in 1941 in the Axis

An axis (: axes) may refer to:

Mathematics

*A specific line (often a directed line) that plays an important role in some contexts. In particular:

** Coordinate axis of a coordinate system

*** ''x''-axis, ''y''-axis, ''z''-axis, common names ...

-aligned Independent State of Croatia

The Independent State of Croatia (, NDH) was a World War II–era puppet state of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy (1922–1943), Fascist Italy. It was established in parts of Axis occupation of Yugoslavia, occupied Yugoslavia on 10 April 1941, ...

.

The Moorish Revival

Moorish Revival or Neo-Moorish is one of the exotic revival architectural styles that were adopted by architects of Europe and the Americas in the wake of Romanticism, Romanticist Orientalism. It reached the height of its popularity after the mi ...

synagogue, designed after the Leopoldstädter Tempel

The Leopoldstädter Tempel, also known as the Israelitische Bethaus in der Wiener Vorstadt Leopoldstadt, (''lit.'' "Israelite prayer house in the Vienna suburb of Leopoldstadt") was a Jewish congregation and synagogue, located on Tempelgasse 5, ...

in Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

, was located on modern-day Praška Street. It was the only purpose-built Jewish synagogue in the history of the city

Towns and city, cities have a long history, although opinions vary on which Ancient history, ancient settlements are truly cities. Historically, the benefits of dense, permanent settlement were numerous, but required prohibitive amounts of food an ...

, and was one of the city's most prominent public buildings, as well as one of the most esteemed examples of synagogue architecture

Synagogue architecture often follows styles in vogue at the place and time of construction. There is no set blueprint for synagogues and architectural shapes and interior designs of synagogues vary greatly. According to tradition, the Shekhinah ...

in the region.

Since the 1980s, plans were made to rebuild the synagogue in its original location. Due to various political circumstances, very limited progress has been made. Major disagreements exist between the government and Jewish organizations as to how much the latter should be involved in decisions about the reconstruction project, including proposed design and character of the new building.

History

Encouraged by the1782 Edict of Tolerance

The 1782 Edict of Tolerance (''Toleranzedikt vom 1782'') was a religious reform of Emperor Joseph II during the time he was emperor of the Habsburg monarchy as part of his policy of Josephinism, a series of drastic reforms to remodel Austria in ...

of Emperor Joseph II

Joseph II (13 March 1741 – 20 February 1790) was Holy Roman Emperor from 18 August 1765 and sole ruler of the Habsburg monarchy from 29 November 1780 until his death. He was the eldest son of Empress Maria Theresa and her husband, Emperor F ...

, Jews first permanently settled in Zagreb in the late eighteenth century, and founded the Jewish community

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, religion, and community are highly inte ...

in 1806. In 1809 the Jewish community

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, religion, and community are highly inte ...

had a rabbi

A rabbi (; ) is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi—known as ''semikha''—following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form of t ...

, and by 1811 it had its own cemetery

A cemetery, burial ground, gravesite, graveyard, or a green space called a memorial park or memorial garden, is a place where the remains of many death, dead people are burial, buried or otherwise entombed. The word ''cemetery'' (from Greek ...

. As early as 1833, the community was permitted to buy land for construction of a synagogue, but did not have sufficient money to finance one at the time.

By 1855, the community had grown to 700 members and, on October 30 of that year, the decision was made to build a new Jewish synagogue. The construction committee, appointed in 1861, selected and purchased a parcel of land at the corner of Maria Valeria Street (now Praška Street) and Ban Jelačić Square

Ban Jelačić Square (; ) is the central square of the city of Zagreb, Croatia, named after ban Josip Jelačić. Its official name is and is colloquially called .

The square is located below Zagreb's old city cores Gradec and Kaptol, just di ...

, the central town square. However, a new urban planning

Urban planning (also called city planning in some contexts) is the process of developing and designing land use and the built environment, including air, water, and the infrastructure passing into and out of urban areas, such as transportatio ...

scheme of 1864 reduced the area available for construction, and the community decided to buy another parcel of in Maria Valeria Street, approximately south of the original location.

Design and construction

Franjo Klein, aVienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

-born Zagreb architect, was commissioned to build the synagogue. Klein, a representative of romantic historicism

Historicism is an approach to explaining the existence of phenomena, especially social and cultural practices (including ideas and beliefs), by studying the process or history by which they came about. The term is widely used in philosophy, ant ...

, modeled the building on the Viennese Leopoldstädter Tempel

The Leopoldstädter Tempel, also known as the Israelitische Bethaus in der Wiener Vorstadt Leopoldstadt, (''lit.'' "Israelite prayer house in the Vienna suburb of Leopoldstadt") was a Jewish congregation and synagogue, located on Tempelgasse 5, ...

(1858), a Moorish Revival temple designed by Ludwig Förster

Ludwig Christian Friedrich (von) Förster (8 October 1797 – 16 June 1863) was a German-born Austrian architect. While he was not Jewish, he is known for building Jewish synagogues and churches.

Ludwig Förster studied in Munich and Vienna. ...

. It became a prototype for synagogue design in Central Europe

Central Europe is a geographical region of Europe between Eastern Europe, Eastern, Southern Europe, Southern, Western Europe, Western and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Central Europe is known for its cultural diversity; however, countries in ...

. Zagreb Synagogue used the already developed round arch style (''Rundbogenstil

(round-arch style) is a 19th-century historic revival style of architecture popular in the German-speaking lands and the German diaspora. It combines elements of Byzantine, Romanesque, and Renaissance architecture with particular s ...

''), but did not adopt Förster's early oriental motifs.

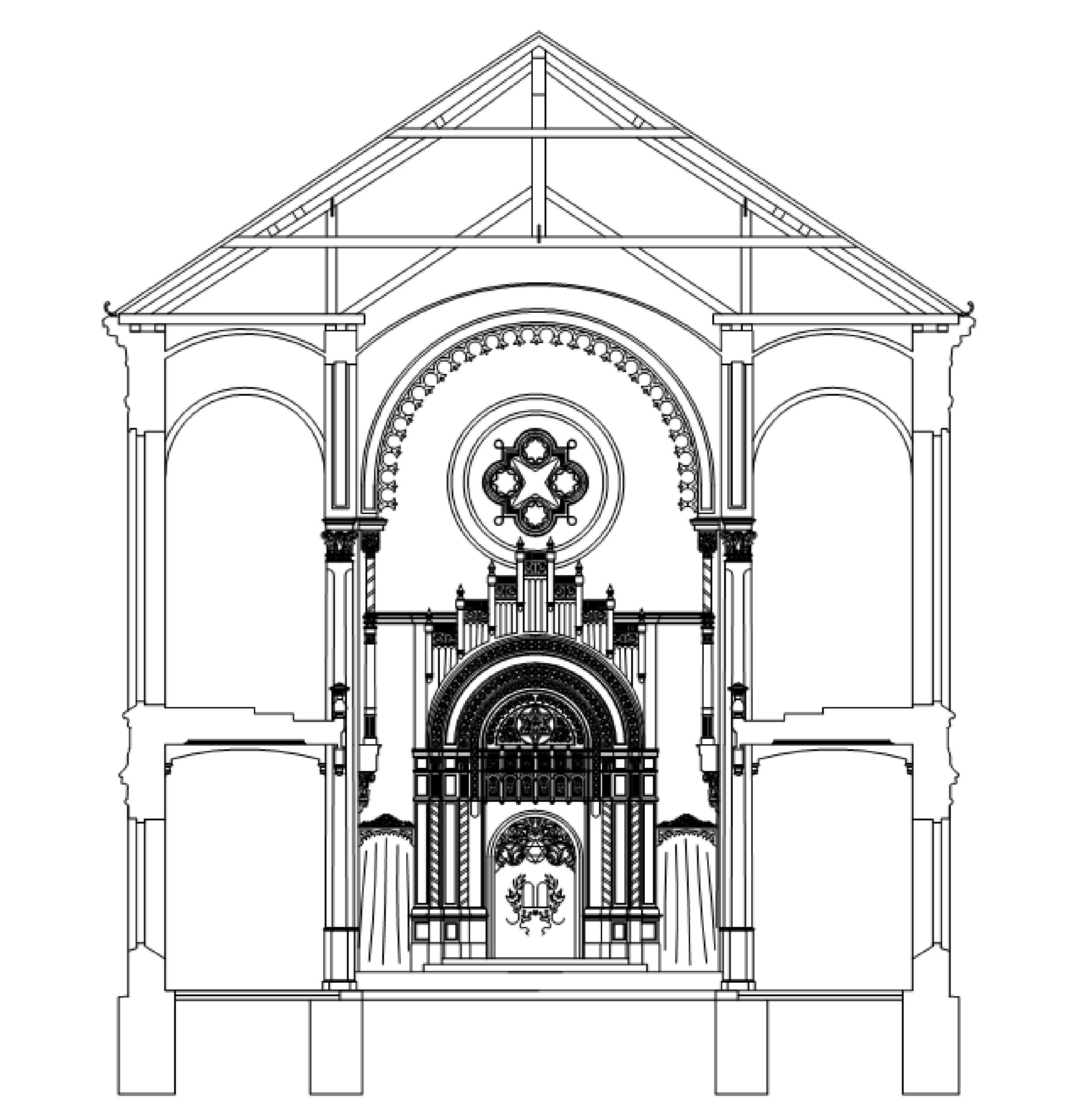

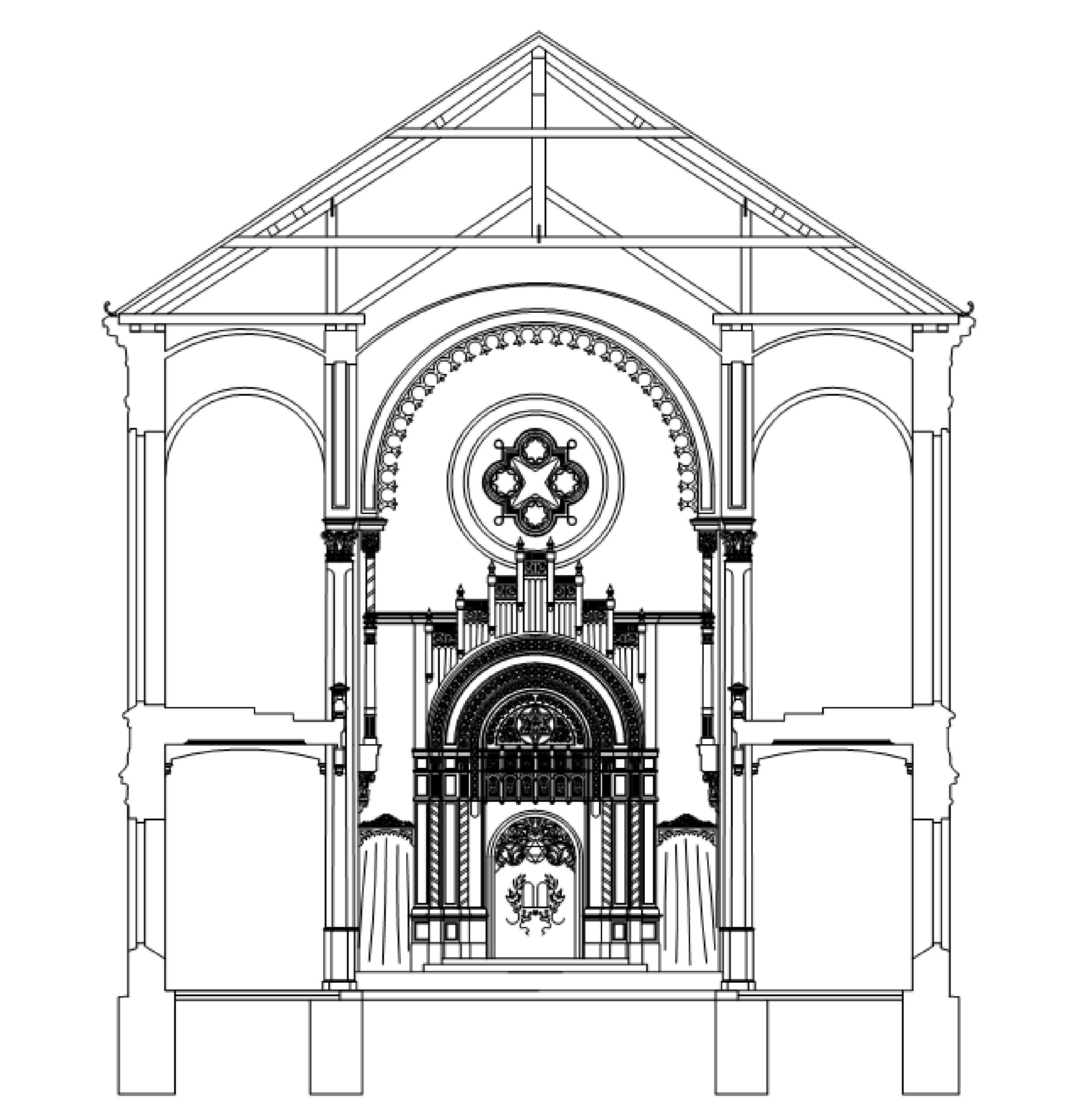

The composition of the main facade, with its dominant drawn-out and elevated projection and the two symmetrical lower lateral parts, reflects the internal division into three

The composition of the main facade, with its dominant drawn-out and elevated projection and the two symmetrical lower lateral parts, reflects the internal division into three nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-type ...

s. At ground-floor level, the front was distinguished by the three-arch entrance and bifora

The bifora or ''pifara'' was a Sicilian double reed instrument of the oboe family, related to the ancient shawm and particularly to the piffero of the northern Italian Apennines. Much larger than the piffero, and made in one piece, it was employ ...

, whereas the first-floor level had a high triforium

A triforium is an interior Gallery (theatre), gallery, opening onto the tall central space of a building at an upper level. In a church, it opens onto the nave from above the side aisles; it may occur at the level of the clerestory windows, o ...

with an elevated arch and the quadrifoliate rosettes on the staircases.

The synagogue occupied the greater part of the plot, facing west. It receded from the street regulation-line in accordance with the rule then still enforced in Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

, prohibiting non-Catholic places of worship from having a public entrance from the street. The synagogue had a wider and slightly higher central nave and two narrower naves; unlike Förster's synagogue in Vienna, it did not have a basilica

In Ancient Roman architecture, a basilica (Greek Basiliké) was a large public building with multiple functions that was typically built alongside the town's forum. The basilica was in the Latin West equivalent to a stoa in the Greek Eas ...

l plan.

Construction began in 1866 and was completed the following year. The synagogue was officially consecrated on September 27, 1867, a ceremony attended by representatives of city and regional authorities, Zagreb public figures, and many citizens. It was the first prominent public building in Zagreb's lower town, and its architecture and scale aroused general admiration and praise.

19th and early 20th century

With the new synagogue, an

With the new synagogue, an organ

Organ and organs may refer to:

Biology

* Organ (biology), a group of tissues organized to serve a common function

* Organ system, a collection of organs that function together to carry out specific functions within the body.

Musical instruments

...

was introduced into religious service. The small minority of Orthodox Jews

Orthodox Judaism is a collective term for the traditionalist branches of contemporary Judaism. Theologically, it is chiefly defined by regarding the Torah, both Written and Oral, as literally revealed by God on Mount Sinai and faithfully tr ...

found this change to be intolerable, and they began to hold their services separately, in rented rooms.

In the 1880 earthquake, the synagogue suffered minor damage and was repaired the following year.

Largely due to immigration from Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

, Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; ; ) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. In a narrow, geographic sense, it roughly encompasses the territories of present-day Czechia that fall within the Elbe River's drainage basin, but historic ...

and Moravia

Moravia ( ; ) is a historical region in the eastern Czech Republic, roughly encompassing its territory within the Danube River's drainage basin. It is one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The medieval and early ...

, the Jewish population of Zagreb quickly grew in size: from 1,285 members in 1887 to 3,237 members in 1900, and then to 5,970 members in 1921. The synagogue became too small to accommodate the needs of the ever-growing community. In 1921 a renovation was undertaken to increase the number of available seats. A 1931 plan to increase the capacity to 944 seats was ultimately abandoned. A central heating

A central heating system provides warmth to a number of spaces within a building from one main source of heat.

A central heating system has a Furnace (central heating), furnace that converts fuel or electricity to heat through processes. The he ...

system was installed in 1933.

Demolition during World War II

During the 1941 collapse of theKingdom of Yugoslavia

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was a country in Southeast Europe, Southeast and Central Europe that existed from 1918 until 1941. From 1918 to 1929, it was officially called the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, but the term "Yugoslavia" () h ...

under the Axis

An axis (: axes) may refer to:

Mathematics

*A specific line (often a directed line) that plays an important role in some contexts. In particular:

** Coordinate axis of a coordinate system

*** ''x''-axis, ''y''-axis, ''z''-axis, common names ...

invasion in the April War

The invasion of Yugoslavia, also known as the April War or Operation 25, was a German-led attack on the Kingdom of Yugoslavia by the Axis powers which began on 6 April 1941 during World War II. The order for the invasion was put forward in "Füh ...

, the Independent State of Croatia was created. It was ruled by the extreme nationalist

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation,Anthony D. Smith, Smith, A ...

Ustaša regime. The Ustaša quickly started with the systematic persecution of the Jews, modeled after the Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

approach, and at times even more brutal. Racial laws were introduced, Jewish property was confiscated, and the Jews were subjected to mass arrests and deportations to death camp

Nazi Germany used six extermination camps (), also called death camps (), or killing centers (), in Central Europe, primarily in occupied Poland, during World War II to systematically murder over 2.7 million peoplemostly Jewsin the Holocau ...

s in Croatia and abroad.

In October 1941, the newly installed mayor of Zagreb, Ivan Werner, issued a decree ordering the demolition of the Praška Street synagogue, ostensibly because it did not fit into the city's master plan. The demolition began on October 10, 1941, proceeding slowly so as not to damage the adjacent buildings; it was finished by April 1942. The whole process was photographed for propaganda purposes, and the photographs were shown to the public at an antisemitic exhibition first held in Zagreb. It was also shown in Dubrovnik

Dubrovnik, historically known as Ragusa, is a city in southern Dalmatia, Croatia, by the Adriatic Sea. It is one of the most prominent tourist destinations in the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean, a Port, seaport and the centre of the Dubrovni ...

, Karlovac

Karlovac () is a city in central Croatia. In the 2021 census, its population was 49,377.

Karlovac is the administrative centre of Karlovac County. The city is located southwest of Zagreb and northeast of Rijeka, and is connected to them via the ...

, Sarajevo

Sarajevo ( ), ; ''see Names of European cities in different languages (Q–T)#S, names in other languages'' is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Bosnia and Herzegovina, largest city of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with a population of 2 ...

, Vukovar

Vukovar (; sr-Cyrl, Вуковар, , ) is a city in Croatia, in the eastern Regions of Croatia, regions of Syrmia and Slavonia. It contains Croatia's largest river port, located at the confluence of the Vuka (river), Vuka and the Danube. Vukova ...

and Zemun

Zemun ( sr-cyrl, Земун, ; ) is a Subdivisions of Belgrade, municipality in the city of Belgrade, Serbia. Zemun was a separate town that was absorbed into Belgrade in 1934. It lies on the right bank of the Danube river, upstream from downtown ...

, as an illustration of the "solution of the Jewish question in Croatia".

A fragment of the film footage of the demolition was discovered five decades later by the film director Lordan Zafranović

Lordan Zafranović (born 11 February 1944) is an eminent Croatian-Czech-Yugoslav film director known for his World War II trilogy consisting of '' Occupation in 26 Pictures'' (1978), '' The Fall of Italy'' (1981), and '' Evening Bells'' (1986), ...

during research for his 1993 documentary feature, ''Decline of the Century: Testimony of L. Z.''; 41 seconds of the film survives. This footage was also shown in Mira Wolf's documentary, ''The Zagreb Synagogue 1867-1942'' (1996), produced by Croatian Radiotelevision

''Hrvatska radiotelevizija'' ( HRT), or Croatian Radiotelevision, is a Croatian public broadcasting company. It operates several radio and television channels, over a domestic transmitter network as well as satellite. HRT is divided into three ...

.

The synagogue's eight valuable

The synagogue's eight valuable Torah scrolls

A Sephardic Torah scroll rolled to the first paragraph of the Shema

An Ashkenazi Torah scroll rolled to the Decalogue

file:Keneseth Eliyahoo Synagogue, Interior, Tora Cases.jpg">Torah cases at Knesset Eliyahoo Synagogue, Mumbai, India ...

were saved due to an intervention by Leonardo Grivičić, an entrepreneur and industrialist who lived next door from Mile Budak

Mile Budak (30 August 1889 – 7 June 1945) was a Croatian politician and writer best known as one of the chief ideologists of the Croatian fascist Ustaša movement, which ruled the Independent State of Croatia during World War II in Yugoslavia ...

, a minister in the Ustaša government. He was also close to ''Poglavnik

() is a Serbo-Croatian word meaning 'leader' or 'guide'.

As a political title, it is strongly associated with Ante Pavelić, head of the fascist organization known as the Ustaše in 1929 and served as dictator of the Independent State of Croa ...

'' Ante Pavelić

Ante Pavelić (; 14 July 1889 – 28 December 1959) was a Croatian politician who founded and headed the fascist ultranationalist organization known as the Ustaše in 1929 and was dictator of the Independent State of Croatia (NDH), a fasc ...

and the Third Reich

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a totalitarian dictat ...

's ambassador to Croatia, Edmund Glaise-Horstenau

Edmund Hugo Guilelmus Glaise von Horstenau (also known as Edmund Glaise-Horstenau; 27 February 1882 – 20 July 1946) was an Austrian Nazi politician who became the last vice-chancellor of Austria, appointed by Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg under ...

. Although Grivičić did not have a significant political role in the Independent State of Croatia, he was considered trustworthy. On October 9, 1941, he learned about the regime's plan to start the demolition of the synagogue on the following morning. By that evening, Grivičić secretly relayed the information to the synagogue's chief cantor, Grüner, and during the night, the Torah scrolls were moved to safety.

Shortly after the destruction of the synagogue, the Catholic archbishop of Zagreb

The Metropolitan Archdiocese of Zagreb (; ) is the central Latin Church archdiocese of the Catholic Church in Croatia, centered in the capital city Zagreb. It is the metropolitan see of Croatia, and the present archbishop is Dražen Kutleša.

It ...

Aloysius Stepinac

Aloysius Viktor Stepinac (, 8 May 1898 – 10 February 1960) was a Croat prelate of the Catholic Church. Made a cardinal in 1953, Stepinac served as Archbishop of Zagreb from 1937 until his death, a period which included the fascist rule of th ...

delivered a homily in which he said: "A house of God of any faith is a holy thing, and whoever harms it will pay with their lives. In this world and the next they will be punished.".

The only surviving fragments of the building — the wash-basin and two memorial tables from the forecourt, as well as some parts of a column — were saved by Ivo Kraus. He pulled them from the rubble shortly after the end of World War II. The wash-basin and the memorial tables are now in the Zagreb City Museum

Zagreb City Museum or Museum of the City of Zagreb () located in 20 Opatička Street, was established in 1907 by the Association of the Brethren of the Croatian Dragon ().

It is located in a restored monumental complex (12th-century Popov toran ...

. The column fragments are kept by the Jewish Community of Zagreb.

Reconstruction efforts

1945–1990

Only one in five Croatian Jews survived the Holocaust ofWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. Between 1948 and 1952, nearly one half of the surviving members of Jewish Community of Zagreb opted for emigration to Israel, and the community dropped to one-tenth of its pre-war membership. The Yugoslav communist regime nationalized

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English)

is the process of transforming privately owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization contrasts with priv ...

virtually all real estate owned by the Jewish Community of Zagreb, including the plot in Praška Street. All this, combined with the new regime's general hostility toward religion, made reconstruction of the synagogue nearly impossible.

After World War II, the vacant site of the former synagogue was used as a makeshift volleyball

Volleyball is a team sport in which two teams of six players are separated by a net. Each team tries to score points by grounding a ball on the other team's court under organized rules. It has been a part of the official program of the Summ ...

court. The volleyball court made way for a prefabricated

Prefabrication is the practice of assembling components of a structure in a factory or other manufacturing site, and transporting complete assemblies or sub-assemblies to the construction site where the structure is to be located. Some research ...

department store

A department store is a retail establishment offering a wide range of consumer goods in different areas of the store under one roof, each area ("department") specializing in a product category. In modern major cities, the department store mad ...

building, constructed in 1959. The department store was completely destroyed in a fire on December 31, 1980, and was subsequently dismantled. Despite some earlier ideas about a permanent department store building on the same spot, and a 1977 architecture competition for its design, no construction took place. Instead, the parcel was turned into a parking lot

A parking lot or car park (British English), also known as a car lot, is a cleared area intended for parking vehicles. The term usually refers to an area dedicated only for parking, with a durable or semi-durable surface. In most jurisdi ...

, which it remains to this day.

After 1986, the Jewish Community of Zagreb began to consider a Jewish cultural center and a memorial synagogue. Two architects, Branko Silađin and Boris Morsan, both of whom participated in the failed 1977 department store competition, came forward on their own accord and contributed their ideas for a new Jewish center in Praška Street. Silađin's vision was ultimately not accepted by the Jewish community; instead, plans were being made for the construction of the cultural center and a synagogue, following an international architecture competition. However, despite support for the project both within Yugoslavia and abroad, the issuance of necessary permits was either stalled or denied by the municipal government. The project was not developed.

1990–present

By the autumn of 1990, after the first democratic elections in Croatia, the municipal government finally approved the project. An architectural competition was planned for January 1991. Political turmoil in the country, followed by thebreakup of Yugoslavia

After a period of political and economic crisis in the 1980s, the constituent republics of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia split apart in the early 1990s. Unresolved issues from the breakup caused a series of inter-ethnic Yugoslav ...

and the Croatian War of Independence

The Croatian War of Independence) and (rarely) "War in Krajina" ( sr-Cyrl-Latn, Рат у Крајини, Rat u Krajini) are used. was an armed conflict fought in Croatia from 1991 to 1995 between Croats, Croat forces loyal to the Governmen ...

(1991–1995), caused the project to be put on hold again. In 1994 President of Croatia Franjo Tuđman

Franjo Tuđman (14 May 1922 – 10 December 1999) was a Croatian politician and historian who became the first president of Croatia, from 1990 until his death in 1999. He served following the Independence of Croatia, country's independe ...

said to Jakov Bienenfeld, Council member of the Zagreb Jewish community, that they should build the new synagogue at the site of the former synagogue, which will be funded by the Croatian government. Bienenfeld declined the offer believing to be inappropriate when a great number of churches are left destroyed at the time, during Croatian War of Independence.

In the meantime, the Jewish Community of Zagreb sought to legally reacquire its property. The Croatian denationalization

Privatization (rendered privatisation in British English) can mean several different things, most commonly referring to moving something from the public sector into the private sector. It is also sometimes used as a synonym for deregulation w ...

law was enacted in 1996, and the Praška Street parcel was finally returned to the community on December 31, 1999. By 2000, reconstruction activities were invigorated again. An investment study was submitted to the Government of Croatia and the City of Zagreb in July 2004 and revised in October 2004. The architecture competition was planned for 2005. However, a 2005 rift in the Jewish Community of Zagreb resulted in formation of a splinter Jewish community, Bet Israel, led by Ivo and Slavko Goldstein

Slavko Goldstein (22 August 1928 – 13 September 2017) was a Croatian historian, politician, and fiction writer.

Biography Early life

Slavko Goldstein was born in Sarajevo in the Jewish family of Ivo and Lea Goldstein. His grandfather Aron ...

.

In September 2006, the Government of Croatia formed a construction workgroup. It was decided that the project, estimated at the time at HRK 173 million (US$

The United States dollar (Currency symbol, symbol: Dollar sign, $; ISO 4217, currency code: USD) is the official currency of the United States and International use of the U.S. dollar, several other countries. The Coinage Act of 1792 introdu ...

30 million), would be partially financed by the Government of Croatia and the City of Zagreb, and that both Jewish organizations should be represented in the workgroup. However, the involvement of Bet Israel was deemed unacceptable by the Jewish Community of Zagreb, which is the sole owner of the Praška Street property, and which also sees itself as the sole legal representative of the Zagreb Jewish community. As a consequence, the community and its president, Ognjen Kraus, refused further participation in the project under the set conditions.

Further disagreements existed about the design and character of the new building. Facsimile

A facsimile (from Latin ''fac simile'', "to make alike") is a copy or reproduction of an old book, manuscript, map, art print, or other item of historical value that is as true to the original source as possible. It differs from other forms of r ...

reconstruction, while feasible, was not seriously contemplated. There was a general agreement that the new building should also have a cultural as well as commercial purpose. While the Jewish Community of Zagreb envisioned a modern design reminiscent of the original synagogue, the Bet Israel advocated building a replica of the original synagogue's facade, perceiving it as having a powerful symbolism. Opinions of architects, urban planners, and art historians were also divided along similar lines.

In 2014 and 2015, the Jewish Community of Zagreb presented new plans for a multi-purpose Jewish center and synagogue in Praška Street. In a 2021 interview, Ognjen Kraus confirmed there were plans for rebuilding the synagogue, but expressed frustration with lack of engagement from the city and government, especially after the 2020 Zagreb earthquake

At approximately 6:24 AM Central European Time, CET on the morning of 22 March 2020, an earthquake of magnitude 5.3 , 5.5 , hit Zagreb, Croatia, with an epicenter north of the city centre. The maximum felt intensity was VII–VIII (''Very stro ...

.

See also

*History of the Jews in Croatia

The history of the Jews in Croatia dates back to at least the 3rd century, although little is known of the community until the 10th and 15th centuries. According to the 1931 census, the community numbered 21,505 members, and it is estimated th ...

* List of synagogues in Croatia

This list of synagogues in Croatia contains active, otherwise used and destroyed synagogues in Croatia. The list of Croatia synagogues is not necessarily complete, as only a negligible number of sources testify to the existence of some synagogues.

...

References

Bibliography

* *Further reading

* * * * * {{good article 1806 establishments in Croatia 1941 disestablishments in Croatia 19th-century synagogues in Europe Buildings and structures demolished in 1941 Buildings and structures destroyed during World War II Destroyed synagogues in Croatia Donji grad, Zagreb Jewish organizations established in 1806 Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia Moorish Revival architecture in Croatia Moorish Revival synagogues Orthodox synagogues in CroatiaSynagogue

A synagogue, also called a shul or a temple, is a place of worship for Jews and Samaritans. It is a place for prayer (the main sanctuary and sometimes smaller chapels) where Jews attend religious services or special ceremonies such as wed ...

Synagogues completed in 1867

Zagreb in World War II