Yemenite Hebrew Language on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Yemenite Hebrew (), also referred to as Temani Hebrew, is the pronunciation system for

Genesis 43:26

Conversely, some words in Hebrew which are written with the final ''hê'' ending (without the ''mappîq'') are realized by a secondary glottal stop and so are abruptly cut short, as to hold one's breath. *A semivocalic sound is heard before ''paṯaḥ gānûḇ/pataħ ganuv'' (furtive ''paṯaḥ'' coming between a long vowel and a final guttural): thus ''ruaħ'' (spirit) sounds like ''rúwwaḥ'' and ''siaħ'' (speech) sounds like ''síyyaḥ''. (That is shared with other Mizrahi pronunciations, such as the

Aharon Ben-Asher, in his treatise on the proper usage of Hebrew vowels and trope symbols, writes on the ''šĕwā'': " t isthe servant of all the letters in the entire Scriptures, whether at the beginning of the word, or in the middle of the word, or at the end of the word; whether what is pronounced by the tongue or not pronounced, for it has many ways… However, if it is joined with one of four utturalletters, , its manner f pronunciationwill be like the manner of the vowel of the second letter in that word, such as: (Jud. 1:7) = ''böhonoth''; (Prov. 1:22) = ''te’ehavu''; (Ps. 10:8) = ''leḥeləkhah''; (Ezra 2:2) = ''reʻeloyoh''."

Aharon Ben-Asher, in his treatise on the proper usage of Hebrew vowels and trope symbols, writes on the ''šĕwā'': " t isthe servant of all the letters in the entire Scriptures, whether at the beginning of the word, or in the middle of the word, or at the end of the word; whether what is pronounced by the tongue or not pronounced, for it has many ways… However, if it is joined with one of four utturalletters, , its manner f pronunciationwill be like the manner of the vowel of the second letter in that word, such as: (Jud. 1:7) = ''böhonoth''; (Prov. 1:22) = ''te’ehavu''; (Ps. 10:8) = ''leḥeləkhah''; (Ezra 2:2) = ''reʻeloyoh''."

On the mobile ''šĕwā'' and its usage amongst Yemenite Jews, Israeli grammarian Shelomo Morag wrote: "The pronunciation of the ''šĕwā'' mobile preceding in the Yemenite tradition is realized in accordance with the vowel following the guttural; quantitatively, however, this is an ultra-short vowel. For example, a word such as is pronounced ''wuḥuṭ''. A ''šĕwā'' preceding a ''yōḏ'' is pronounced as an ultra-short ''ḥīreq'': the word is pronounced ''biyōm''. This is the way the ''šĕwā'' is known to have been pronounced in the Tiberian tradition."

Other examples of words of the mobile ''šĕwā'' in the same word taking the phonetic sound of the vowel assigned to the adjacent guttural letter or of a mobile ''šĕwā'' before the letter ''yod'' (י) taking the phonetic sound of the ''yod'', can be seen in the following:

*(Gen. 48:21) = ''weheshiv''

*(Gen. 49:30) = ''bamoʻoroh''

*(Gen. 50:10) = ''beʻevar''

*(Exo. 7:27) = ''wi’im''

*(Exo. 20:23) = ''mizbiḥī''

*(Deut. 11:13) = ''wohoyoh''

*(Psalm 92:1–3)

(vs. 1) ''liyöm'' – (vs. 2) ''lohödöth'' – (vs. 3) ''lahaǧīd''

The above rule applies only to when one of the four guttural letters (אחהע), or a ''yod'' (י) or a resh (ר) follows the mobile ''šĕwā'', but it does not apply to the other letters; then, the mobile ''šĕwā'' is always read as a short-sounding ''pataḥ''.

On the mobile ''šĕwā'' and its usage amongst Yemenite Jews, Israeli grammarian Shelomo Morag wrote: "The pronunciation of the ''šĕwā'' mobile preceding in the Yemenite tradition is realized in accordance with the vowel following the guttural; quantitatively, however, this is an ultra-short vowel. For example, a word such as is pronounced ''wuḥuṭ''. A ''šĕwā'' preceding a ''yōḏ'' is pronounced as an ultra-short ''ḥīreq'': the word is pronounced ''biyōm''. This is the way the ''šĕwā'' is known to have been pronounced in the Tiberian tradition."

Other examples of words of the mobile ''šĕwā'' in the same word taking the phonetic sound of the vowel assigned to the adjacent guttural letter or of a mobile ''šĕwā'' before the letter ''yod'' (י) taking the phonetic sound of the ''yod'', can be seen in the following:

*(Gen. 48:21) = ''weheshiv''

*(Gen. 49:30) = ''bamoʻoroh''

*(Gen. 50:10) = ''beʻevar''

*(Exo. 7:27) = ''wi’im''

*(Exo. 20:23) = ''mizbiḥī''

*(Deut. 11:13) = ''wohoyoh''

*(Psalm 92:1–3)

(vs. 1) ''liyöm'' – (vs. 2) ''lohödöth'' – (vs. 3) ''lahaǧīd''

The above rule applies only to when one of the four guttural letters (אחהע), or a ''yod'' (י) or a resh (ר) follows the mobile ''šĕwā'', but it does not apply to the other letters; then, the mobile ''šĕwā'' is always read as a short-sounding ''pataḥ''.

Although the vast majority of post-Biblical Hebrew and Aramaic words are pronounced the same way or nearly the same way by all of Israel's diverse ethnic groups, including the Jews of Yemen, there are still other words whose phonemic system differs greatly from the way it is used in Modern Hebrew, the sense here being the tradition of vocalization or

Although the vast majority of post-Biblical Hebrew and Aramaic words are pronounced the same way or nearly the same way by all of Israel's diverse ethnic groups, including the Jews of Yemen, there are still other words whose phonemic system differs greatly from the way it is used in Modern Hebrew, the sense here being the tradition of vocalization or

Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

traditionally used by Yemenite Jews

Yemenite Jews, also known as Yemeni Jews or Teimanim (from ; ), are a Jewish diaspora group who live, or once lived, in Yemen, and their descendants maintaining their customs. After several waves of antisemitism, persecution, the vast majority ...

. Yemenite Hebrew has been studied by language scholars, many of whom believe it retains older phonetic and grammatical features lost elsewhere. Yemenite speakers of Hebrew have garnered considerable praise from language purists because of their use of grammatical features from classical Hebrew.

Some scholars believe that its phonology

Phonology (formerly also phonemics or phonematics: "phonemics ''n.'' 'obsolescent''1. Any procedure for identifying the phonemes of a language from a corpus of data. 2. (formerly also phonematics) A former synonym for phonology, often pre ...

was heavily influenced by spoken Yemeni Arabic

Yemeni Arabic () is a cluster of varieties of Arabic spoken in Yemen and southwestern Saudi Arabia. It is generally considered a very conservative dialect cluster, having many classical features not found across most of the Arabic-speaking world ...

. Other scholars, including Yosef Qafih

Yosef Qafiḥ ( , ), widely known as Rabbi Yosef Kapach (27 November 1917 – 21 July 2000), was a Yemenite-Israeli posek, authority on Jewish religious law (''halakha''), a Dayan (rabbinic judge), dayan of the Judiciary of Israel#Jewish courts, ...

and Abraham Isaac Kook

Abraham Isaac HaCohen Kook (; 7 September 1865 – 1 September 1935), known as HaRav Kook, and also known by the Hebrew-language acronym Hara'ayah (), was an Orthodox Judaism, Orthodox rabbi, and the first Ashkenazi Jews, Ashkenazi Chief Rabbina ...

, hold the view that Yemenite Arabic did not influence Yemenite Hebrew, as this type of Arabic was also spoken by Yemenite Jews and is distinct from the liturgical and conversational Hebrew of the communities. Among other things, Qafih noted that the Yemenite Jews spoke Arabic with a distinct Jewish flavor, inclusive of pronouncing many Arabic words with vowels foreign to the Arabic language, e.g., the qamatz

Kamatz or qamatz (, ; alternatively ) is a Hebrew niqqud (vowel) sign represented by two perpendicular lines (looking like an uppercase T) underneath a letter. In modern Hebrew, it usually indicates the phoneme which is the " a" sound in the ...

() and tzere

Tzere (also spelled ''Tsere'', ''Tzeirei'', ''Zere'', ''Zeire'', ''Ṣērê''; modern , , sometimes also written ; formerly ''ṣērê'') is a Hebrew niqqud vowel sign represented by two horizontally-aligned dots "◌ֵ" underneath a lette ...

(). He argues that the pronunciation of Yemenite Hebrew was not only uninfluenced by Arabic, but it influenced the pronunciation of Arabic by those Jews, despite the Jewish presence in Yemen for over a millennium.

History

Yemenite Hebrew may have been derived from, or influenced by, the Hebrew of theTalmudic academies in Babylonia

The Talmudic academies in Babylonia, also known as the Geonic academies, were the center for Jewish scholarship and the development of Halakha during the Geonic era (from c. 589 to 1038 CE; Hebrew dates: 4349 AM to 4798 AM) in what is called ...

: the oldest Yemenite manuscripts use the Babylonian vocalization

The Babylonian vocalization, also known as Babylonian supralinear punctuation, or Babylonian pointing or Babylonian niqqud Hebrew: ) is a system of diacritics (niqqud) and vowel symbols assigned above the text and devised by the Masoretes of Ba ...

, which is believed to antedate the Tiberian vocalization

The Tiberian vocalization, Tiberian pointing, or Tiberian niqqud () is a system of diacritics (''niqqud'') devised by the Masoretes of Tiberias to add to the consonantal text of the Hebrew Bible to produce the Masoretic Text. The system soon beca ...

. As late as 937, Jacob Qirqisani

Jacob Qirqisani (c. 890 – c. 960) ( ''ʾAbū Yūsuf Yaʿqūb al-Qirqisānī'', ''Yaʿaqov ben Yiṣḥaq haQarqesani'') was a Karaite dogmatist and exegete who flourished in the first half of the tenth century. His origins are unknown. His pat ...

wrote: "The biblical readings which are wide-spread in Yemen are in the Babylonian tradition." Indeed, in many respects, such as the assimilation of '' paṯaḥ'' and '' səġūl'', the current Yemenite pronunciation fits the Babylonian notation better than the Tiberian (though the Babylonian notation does not reflect the approximation between ''holam'' and ''sere'' in some Yemenite dialects). This is because in the Babylonian tradition of vocalization there is no distinct symbol for the ''səġūl''. It does not follow, as claimed by some scholars, that the pronunciation of the two communities was identical, any more than the pronunciation of Sephardim and Ashkenazim is the same because both use the Tiberian symbols.

The following chart shows the seven vowel paradigms found in the Babylonian supralinear punctuation, which are reflected to this day by the Yemenite pronunciation of Biblical lections and liturgies, though they now use the Tiberian symbols. For example, there is no separate symbol for the Tiberian ''səġūl'' and the ''pataḥ'' and amongst Yemenites they have the same phonetic sound. In this connection, the Babylonian vowel signs remained in use in Yemen long after the Babylonian Biblical tradition had been abandoned, almost until our own time.

Distinguishing features

The following chart shows the phonetic values of the Hebrew letters in the Yemenite Hebrew pronunciation tradition. Yemenites have preserved the sounds for each of the six double-sounding consonants: ''bəged-kəfet'' (). The following are examples of their peculiar way of pronunciation of these and other letters: *''gímel/ǧimal'' () with the ''dāḡēš/dageš'' is pronounced . Thus, the verse (Deut. 4:8) is realized as, ''u'mi, ǧoi ǧaḏol'' () (as in Sanʽani Arabic ǧīm /d͡ʒ/ but unlikeTaʽizzi-Adeni Arabic

Taʽizzi-Adeni Arabic () or Southern Yemeni Arabic is a dialect of Arabic spoken primarily in Yemen. The dialect itself is further sub-divided into the regional vernaculars of Ta'izzi, spoken in Ta'izz, and Adeni, spoken in Aden. While both are s ...

/g/).

*''gímel/gimal'' () without ''dāḡēš/dageš'' is pronounced , like Arabic ġayn

The Arabic letter (, or ) is one of the six letters the Arabic alphabet added to the twenty-two inherited from the Phoenician alphabet (the others being , , , , ). It represents the sound or . In name and shape, it is a variant of ʻayn ...

.

*''dāleṯ/dal'' () without ''dāḡēš/dageš'' is pronounced , like Arabic ḏāl

' (, also transcribed as ') is one of the six letters the Arabic alphabet added to the twenty-two inherited from the Phoenician alphabet (the others being , , , , ). It is related to the Ancient North Arabian 𐪙, and Ancient South ...

. Thus, the word in ''Shema Yisrael

''Shema Yisrael'' (''Shema Israel'' or ''Sh'ma Yisrael''; , “Hear, O Israel”) is a Jewish prayer (known as the Shema) that serves as a centerpiece of the morning and evening Jewish prayer services. Its first verse encapsulates the monothe ...

'' is always pronounced ''aḥoḏ'' ().

*The pronunciation of ''tāv/taw'' () without ''dāḡēš/dageš'' as (shared by other Mizrahi Hebrew

Mizrahi Hebrew, or Eastern Hebrew (), is a group of pronunciation systems for Biblical Hebrew used liturgically by Mizrahi Jews: Jews from Arab countries or east of them and with a background of Arabic, Persian or other languages of Asia. As suc ...

dialects such as Iraqi). Thus, ''Sabbath day'' is pronounced in Yemenite Hebrew, ''Yom ha-Shabboth'' ().

*''vāv/waw'' () is pronounced (as in Iraqi Hebrew and in Arabic).

*Emphatic and guttural letters have nearly the same sounds and are produced from deep in the throat, as in Arabic.

*''ḥêṯ/ħet'' () is a voiceless pharyngeal fricative

The voiceless pharyngeal fricative is a type of consonantal sound, used in some Speech communication, spoken languages. The symbol in the International Phonetic Alphabet that represents this sound is an h with stroke, h-bar, , and the equivalent ...

, equivalent to Arabic ح .

*''ʻáyin/ʕajin'' () is identical to Arabic , and is a voiced pharyngeal fricative

The voiced pharyngeal approximant or fricative is a type of consonantal sound, used in some spoken languages. The symbol in the International Phonetic Alphabet that represents this sound is , and the equivalent X-SAMPA symbol is ?\. Epiglot ...

. (The Sephardic pronunciation of ע, however, is of a weaker nature.)

*''tsadi'' () is not a voiceless alveolar sibilant affricate "ts" among the Yemenites, but rather a deep-sounding "s" (pharyngealized fricative).

*''qof'' () is pronounced by the Yemenites (other than the Jews from Shar'ab) as a voiced /g/, (as in Sanʽani Arabic gāf /g/ but unlike Taʽizzi-Adeni Arabic

Taʽizzi-Adeni Arabic () or Southern Yemeni Arabic is a dialect of Arabic spoken primarily in Yemen. The dialect itself is further sub-divided into the regional vernaculars of Ta'izzi, spoken in Ta'izz, and Adeni, spoken in Aden. While both are s ...

/q/) and is in keeping with their tradition that a different phonetic sound is given for ''gímel''/''gimal'' (see ''supra'').

*''resh'' () is pronounced as an alveolar trill

The voiced alveolar trill is a type of consonantal sound used in some spoken languages. The symbol in the International Phonetic Alphabet that represents dental consonant, dental, alveolar consonant, alveolar, and postalveolar consonant, postalve ...

/r/, rather than the uvular trill � and is identical to Arabic ' and follows the conventions of old Hebrew.

*The ''kaf sofit'' with a dagesh () is pronounced as such, ('ka') as in the rare example of the last word in Psalm 30.

Vowels

*''Qāmaṣ gāḏôl/Qamac qadol'' is pronounced , as inAshkenazi Hebrew

Ashkenazi Hebrew (, ) is the pronunciation system for Biblical and Mishnaic Hebrew favored for Jewish liturgical use and Torah study by Ashkenazi Jewish practice.

Features

As it is used parallel with Modern Hebrew, its phonological differences a ...

and Tiberian Hebrew

Tiberian Hebrew is the canonical pronunciation of the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) committed to writing by Masoretic scholars living in the Jewish community of Tiberias in ancient Galilee under the Abbasid Caliphate. They wrote in the form of Tib ...

. The Yemenite pronunciation for ''Qamats gadol'' () and ''Qamats qatan'' () is identical (see '' infra''.).

*There is no distinction between the vowels ''paṯaḥ/pataħ'' and ''səḡôl/segol'' all being pronounced , like the Arabic ''fatḥa'' (a feature also found in old Babylonian Hebrew, which used a single symbol for all three).''Siddur Tefillat Kol Pe'', vol. 1 (foreword written by Shalom Yitzhak Halevi), Jerusalem 1960, p. 11 (Hebrew) A ''šəwâ nāʻ/šwa naʕ'', however, is identical to a חטף פתח and חטף סגול.

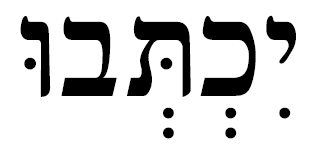

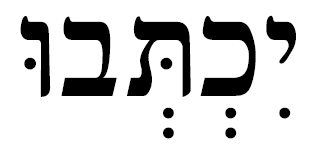

*Final ''hê/hej'' with ''mappîq/mefiq'' has an aspirated sound, generally stronger sounding than the regular ''hê/hej''. ''Aleph'' (אַלַף) with a ''dagesh'', a rare occurrence, is pronounced with a glottal stop

The glottal stop or glottal plosive is a type of consonantal sound used in many Speech communication, spoken languages, produced by obstructing airflow in the vocal tract or, more precisely, the glottis. The symbol in the International Phonetic ...

, e.g., the word וַיָּבִיאּוּ iGenesis 43:26

Conversely, some words in Hebrew which are written with the final ''hê'' ending (without the ''mappîq'') are realized by a secondary glottal stop and so are abruptly cut short, as to hold one's breath. *A semivocalic sound is heard before ''paṯaḥ gānûḇ/pataħ ganuv'' (furtive ''paṯaḥ'' coming between a long vowel and a final guttural): thus ''ruaħ'' (spirit) sounds like ''rúwwaḥ'' and ''siaħ'' (speech) sounds like ''síyyaḥ''. (That is shared with other Mizrahi pronunciations, such as the

Syrian

Syrians () are the majority inhabitants of Syria, indigenous to the Levant, most of whom have Arabic, especially its Levantine and Mesopotamian dialects, as a mother tongue. The cultural and linguistic heritage of the Syrian people is a blend ...

.)

Yemenite pronunciation is not uniform, and Morag has distinguished five sub-dialects, the best known being probably Sana'ani, originally spoken by Jews in and around Sana'a

Sanaa, officially the Sanaa Municipality, is the ''de jure'' capital and largest city of Yemen. The city is the capital of the Sanaa Governorate, but is not part of the governorate, as it forms a separate administrative unit. At an elevation ...

. Roughly, the points of difference are as follows:

*In some dialects, ''ḥōlem/ħolam'' (long "o" in modern Hebrew) is pronounced , but in others, it is pronounced like ''ṣêrệ/cerej''. (The last pronunciation is shared with Lithuanian Jews

{{Jews and Judaism sidebar , Population

Litvaks ({{Langx, yi, ליטװאַקעס) or Lita'im ({{Langx, he, לִיטָאִים) are Jews who historically resided in the territory of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania (covering present-day Lithuan ...

.)

*Some dialects (e.g. Sharab) do not differentiate between ''bêṯ/bet'' with ''dāḡēš/dageš'' and without it. That occurs most of Mizrahi Hebrew

Mizrahi Hebrew, or Eastern Hebrew (), is a group of pronunciation systems for Biblical Hebrew used liturgically by Mizrahi Jews: Jews from Arab countries or east of them and with a background of Arabic, Persian or other languages of Asia. As suc ...

.

*Sana'ani Hebrew primarily places stress on the penultimate syllable, as in Ashkenazi Hebrew.

''Qamats Gadol'' and ''Qamats Qatan''

Yemenite reading practices continue the orthographic conventions of the early grammarians, such as Abraham ibn Ezra and Aaron Ben-Asher. One basic rule of grammar states that every word with a long vowel sound, that is, one of either five vowel sounds whose mnemonics are "pītūḥe ḥöthom" (i.e. ''ḥiraq'', ''šūraq'', ''ṣeré'', ''ḥölam'' and ''qamaṣ''), whenever there is written beside one of these long vowel sounds a ''meteg'' (or what is also called a ''ga’ayah'') and is denoted by a small vertical line below the word (e.g. under the ז in זָֽכְרוּ), it indicates that the vowel (in that case, ''qamaṣ'') must be drawn out with a prolonged sound. For example, ōōōōōō, instead of ō, (e.g. ''zoː— khǝ ru''). In the Sephardic tradition, however, the practice is different altogether, and they will also alter the phonetic sound of the short vowel ''qamaṣ qattön'' whenever the vowel appears alongside a ''meteg'' (a small vertical line), reading it as the long vowel ''qamaṣ gadöl'', giving to it the sound of "a", as in ''ca''r, instead of "ōōōōō." Thus, for the verse in (Psalm 35:10), the Sephardic Jews will pronounce the word כָּל as "kal" (e.g. ''kal ʕaṣmotai'', etc.), instead of ''kol ʕaṣmotai'' as pronounced by both Yemenite and Ashkenazi Jewish communities. The ''meteg'', or ''ga’ayah'', has actually two functions: (1) It extends the sound of the vowel; (2) It makes any šewa that is written immediately after the vowel a mobile ''šewa'', meaning, the ''šewa'' itself becomes . For example: = ''ʔö mǝ rim'', = ''šö mǝ rim'', = ''sī sǝ ra'', = ''šū vǝ kha'', and = ''tū vǝ kha''. Examples with ''meteg/ga’ayah'': = ''šoː mǝ ro'', = ''ye rǝ du.'' The ''Qamats qatan'' is realized as the non-extended "o"-sound in the first ''qamats'' (''qamaṣ'') in the word, חָכְמָה ⇒ ''ḥokhma'' (wisdom). The Yemenite ''qamaṣ'' is represented in the transliterated texts by thediaphoneme

A diaphoneme is an abstract phonology, phonological unit that identifies a correspondence between related sounds of two or more variety (linguistics), varieties of a language or language cluster. For example, some English varieties contrast the ...

. The vowel quality is the same, whether for a long or short vowel, but the long vowel sound is always prolonged.

''Holam'' and ''sere''

A distinct feature of Yemenite Hebrew is that there is some degree of approximation between the '' ḥōlam'' and the '' ṣêrệ''. To the untrained ear, they may sound as the same phoneme, but Yemenite grammarians will point out the difference. The feature varies by dialect: *In the standard, provincial pronunciation that is used by most Yemenite Jews, ''holam'' is pronounced as . For example, the word "''shalom''" (), is pronounced ''sholøm''. *In some provincial dialects, in particular that ofAden

Aden () is a port city located in Yemen in the southern part of the Arabian peninsula, on the north coast of the Gulf of Aden, positioned near the eastern approach to the Red Sea. It is situated approximately 170 km (110 mi) east of ...

, ''holam'' becomes a long ''e'' and is indeed indistinguishable from ''sere'', and some early manuscripts sometimes confuse or interchange the symbols for the two sounds.

Some see the assimilation of the two vowels as a local variant within the wider Babylonian family, which the Yemenites happened to follow.

Strict application of Mobile Shewā

RabbiAbraham Isaac Kook

Abraham Isaac HaCohen Kook (; 7 September 1865 – 1 September 1935), known as HaRav Kook, and also known by the Hebrew-language acronym Hara'ayah (), was an Orthodox Judaism, Orthodox rabbi, and the first Ashkenazi Jews, Ashkenazi Chief Rabbina ...

and Rabbi Jacob Saphir

Jacob Saphir (; 1822–1886), often pronounced Yaakov Sapir, was a 19th-century writer, ethnographer, researcher of Hebrew manuscripts, a traveler and Meshulach, emissary of the rabbis of Eastern European Jewry, Eastern European Jewish descent wh ...

have praised the Yemenites in their correct pronunciation of Hebrew. They still read the biblical lections and liturgies according to what is prescribed for Hebrew grammar and are meticulous to pronounce the mobile ''šĕwā'' in each of its changing forms. While most other communities also adhere to the rule of mobile '' šĕwā'' whenever two ''šĕwā''s are written one after the other, as in , most have forgotten its other usages.

Aharon Ben-Asher, in his treatise on the proper usage of Hebrew vowels and trope symbols, writes on the ''šĕwā'': " t isthe servant of all the letters in the entire Scriptures, whether at the beginning of the word, or in the middle of the word, or at the end of the word; whether what is pronounced by the tongue or not pronounced, for it has many ways… However, if it is joined with one of four utturalletters, , its manner f pronunciationwill be like the manner of the vowel of the second letter in that word, such as: (Jud. 1:7) = ''böhonoth''; (Prov. 1:22) = ''te’ehavu''; (Ps. 10:8) = ''leḥeləkhah''; (Ezra 2:2) = ''reʻeloyoh''."

Aharon Ben-Asher, in his treatise on the proper usage of Hebrew vowels and trope symbols, writes on the ''šĕwā'': " t isthe servant of all the letters in the entire Scriptures, whether at the beginning of the word, or in the middle of the word, or at the end of the word; whether what is pronounced by the tongue or not pronounced, for it has many ways… However, if it is joined with one of four utturalletters, , its manner f pronunciationwill be like the manner of the vowel of the second letter in that word, such as: (Jud. 1:7) = ''böhonoth''; (Prov. 1:22) = ''te’ehavu''; (Ps. 10:8) = ''leḥeləkhah''; (Ezra 2:2) = ''reʻeloyoh''."

On the mobile ''šĕwā'' and its usage amongst Yemenite Jews, Israeli grammarian Shelomo Morag wrote: "The pronunciation of the ''šĕwā'' mobile preceding in the Yemenite tradition is realized in accordance with the vowel following the guttural; quantitatively, however, this is an ultra-short vowel. For example, a word such as is pronounced ''wuḥuṭ''. A ''šĕwā'' preceding a ''yōḏ'' is pronounced as an ultra-short ''ḥīreq'': the word is pronounced ''biyōm''. This is the way the ''šĕwā'' is known to have been pronounced in the Tiberian tradition."

Other examples of words of the mobile ''šĕwā'' in the same word taking the phonetic sound of the vowel assigned to the adjacent guttural letter or of a mobile ''šĕwā'' before the letter ''yod'' (י) taking the phonetic sound of the ''yod'', can be seen in the following:

*(Gen. 48:21) = ''weheshiv''

*(Gen. 49:30) = ''bamoʻoroh''

*(Gen. 50:10) = ''beʻevar''

*(Exo. 7:27) = ''wi’im''

*(Exo. 20:23) = ''mizbiḥī''

*(Deut. 11:13) = ''wohoyoh''

*(Psalm 92:1–3)

(vs. 1) ''liyöm'' – (vs. 2) ''lohödöth'' – (vs. 3) ''lahaǧīd''

The above rule applies only to when one of the four guttural letters (אחהע), or a ''yod'' (י) or a resh (ר) follows the mobile ''šĕwā'', but it does not apply to the other letters; then, the mobile ''šĕwā'' is always read as a short-sounding ''pataḥ''.

On the mobile ''šĕwā'' and its usage amongst Yemenite Jews, Israeli grammarian Shelomo Morag wrote: "The pronunciation of the ''šĕwā'' mobile preceding in the Yemenite tradition is realized in accordance with the vowel following the guttural; quantitatively, however, this is an ultra-short vowel. For example, a word such as is pronounced ''wuḥuṭ''. A ''šĕwā'' preceding a ''yōḏ'' is pronounced as an ultra-short ''ḥīreq'': the word is pronounced ''biyōm''. This is the way the ''šĕwā'' is known to have been pronounced in the Tiberian tradition."

Other examples of words of the mobile ''šĕwā'' in the same word taking the phonetic sound of the vowel assigned to the adjacent guttural letter or of a mobile ''šĕwā'' before the letter ''yod'' (י) taking the phonetic sound of the ''yod'', can be seen in the following:

*(Gen. 48:21) = ''weheshiv''

*(Gen. 49:30) = ''bamoʻoroh''

*(Gen. 50:10) = ''beʻevar''

*(Exo. 7:27) = ''wi’im''

*(Exo. 20:23) = ''mizbiḥī''

*(Deut. 11:13) = ''wohoyoh''

*(Psalm 92:1–3)

(vs. 1) ''liyöm'' – (vs. 2) ''lohödöth'' – (vs. 3) ''lahaǧīd''

The above rule applies only to when one of the four guttural letters (אחהע), or a ''yod'' (י) or a resh (ר) follows the mobile ''šĕwā'', but it does not apply to the other letters; then, the mobile ''šĕwā'' is always read as a short-sounding ''pataḥ''.

Distinctive pronunciations preserved

Geographically isolated for centuries, the Yemenite Jews constituted a peculiar phenomenon within Diaspora Jewry. In their isolation, they preserved specific traditions of both Hebrew and Aramaic. The traditions, transmitted from generation to generation through the teaching and reciting of the Bible, post-biblical Hebrew literature (primarily theMishnah

The Mishnah or the Mishna (; , from the verb ''šānā'', "to study and review", also "secondary") is the first written collection of the Jewish oral traditions that are known as the Oral Torah. Having been collected in the 3rd century CE, it is ...

), the Aramaic Targum

A targum (, ''interpretation'', ''translation'', ''version''; plural: targumim) was an originally spoken translation of the Hebrew Bible (also called the ) that a professional translator ( ''mǝṯurgǝmān'') would give in the common language o ...

s of the Bible, and the Babylonian Talmud

The Talmud (; ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the centerpiece of Jewi ...

, are still alive.''The Traditions of Hebrew and Aramaic of the Jews of Yemen'' (ed. Yosef Tobi), in Article entitled: ''Notes on the Vowel System of Babylonian Aramaic as Preserved in the Yemenite Tradition'', Shelomo Morag, Tel-Aviv, 2001, p. 181. They are manifest in the traditional manner of reading Hebrew that is practised by most members of the community. The Yemenite reading traditions of the Bible are now based on the Tiberian text and vocalization, as proofread by the masorete, Aaron ben Asher, with the one exception that the vowel ''sǝġūl'' is pronounced as a ''pataḥ'', since the ''sǝġūl'' did not exist in the Babylonian orthographic tradition to which the Jews of Yemen had previously been accustomed. In what concerns Biblical orthography, with the one exception of the ''sǝgūl'', the Yemenite Jewish community does not differ from any other Jewish community.

Although the vast majority of post-Biblical Hebrew and Aramaic words are pronounced the same way or nearly the same way by all of Israel's diverse ethnic groups, including the Jews of Yemen, there are still other words whose phonemic system differs greatly from the way it is used in Modern Hebrew, the sense here being the tradition of vocalization or

Although the vast majority of post-Biblical Hebrew and Aramaic words are pronounced the same way or nearly the same way by all of Israel's diverse ethnic groups, including the Jews of Yemen, there are still other words whose phonemic system differs greatly from the way it is used in Modern Hebrew, the sense here being the tradition of vocalization or diction

Diction ( (nom. ), "a saying, expression, word"), in its original meaning, is a writer's or speaker's distinctive vocabulary choices and style of expression in a piece of writing such as a poem or story.Crannell (1997) ''Glossary'', p. 406 In its c ...

of selective Hebrew words found in the Mishnah and Midrashic literature, or of Aramaic words found in the Talmud, and which tradition has been meticulously preserved by the Jews of Yemen

Yemenite Jews, also known as Yemeni Jews or Teimanim (from ; ), are a Jewish diaspora group who live, or once lived, in Yemen, and their descendants maintaining their customs. After several waves of persecution, the vast majority of Yemenite J ...

. Two of the more recognized Yemenite pronunciations are for the words and , the first pronounced as ''Ribbi'', instead of Rabbi (as in Rabbi Meir), and the second pronounced ''guvra'', instead of ''gavra''. In the first case, archaeologist Benjamin Mazar

Benjamin Mazar (; born Binyamin Zeev Maisler, June 28, 1906 – September 9, 1995) was a pioneering Israeli historian, recognized as the "dean" of biblical archaeologists. He shared the national passion for the archaeology of Israel that also at ...

was the first to discover its linguistic usage in the funerary epigrams of the 3rd and 4th-century CE, during excavations at the catacombs in Beit She'arim. Nahman Avigad, speaking of the same, wrote: "Of special interest is the title Rabbi and its Greek transliteration (). In the inscriptions of Beth She'arim found in the former seasons and are usual, and only once do we find , which has been regarded as a defective form of , for in Greek we generally find the form (). The transliteration () found here shows that the title was pronounced in Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

in different ways, sometimes ''Rabbi'' (ΡΑΒΒΙ, ΡΑΒΙ), sometimes ''Ribbi'' (ΡΙΒΒΙ, ΡΙΒΙ) and occasionally even ''Rebbi'' (ΒΗΡΕΒΙ)." In the latter case, the Jerusalem Talmud

The Jerusalem Talmud (, often for short) or Palestinian Talmud, also known as the Talmud of the Land of Israel, is a collection of rabbinic notes on the second-century Jewish oral tradition known as the Mishnah. Naming this version of the Talm ...

occasionally brings down the word in '' plene scriptum'', (pl. for ), showing that its pronunciation was the same as that in use by the Yemenites. Some have raised the proposition that the Yemenite linguistic tradition dates back to the Amoraim

''Amoraim'' ( , singular ''Amora'' ; "those who say" or "those who speak over the people", or "spokesmen") refers to Jewish scholars of the period from about 200 to 500 CE, who "said" or "told over" the teachings of the Oral Torah. They were p ...

.

R. Yehudai Gaon, in his ''Halakhot Pesukot'' (Hil. ''Berakhot''), uses '' yod'' as the ''mater lectionis

A ''mater lectionis'' ( , ; , ''matres lectionis'' ; original ) is any consonant letter that is used to indicate a vowel, primarily in the writing of Semitic languages such as Arabic, Hebrew and Syriac. The letters that do this in Hebrew are ...

'' to show the vowel ''hiriq

Hiriq, also called Chirik ( ' ) is a Hebrew niqqud vowel sign represented by a single dot underneath the letter. In Modern Hebrew, it indicates the phoneme which is similar to the "ee" sound in the English word ''deep'' and is transliter ...

'', after the ''qoph

Qoph is the nineteenth letter of the Semitic abjads, including Phoenician ''qōp'' 𐤒, Hebrew ''qūp̄'' , Aramaic ''qop'' 𐡒, Syriac ''qōp̄'' ܩ, and Arabic ''qāf'' . It is also related to the Ancient North Arabian , South Arabian ...

'' () in ''Qiryat Shema'' (). The editor of the critical edition, A. Israel, who places its composition in Babylonia, notes that "linguists would take an interest" in Yehudai Gaon's variant spellings of words, where especially the ''matres lectionis'' is used in place of vowels, "represented either by a plene ''alef'' (), ''waw'' (), and ''yod'' ()." The use of the ''matres lectionis'' in place of the vowel ''hiriq'' in the construct case of the words קִרְיַת שְׁמַע ("recital of Shemaʻ" = קירית שמע) reflects apparently the Babylonian tradition of pronunciation, and, today, the same tradition is mirrored in the Yemenite pronunciation of ''Qiryat shemaʻ''.

The following diagrams show a few of the more conspicuous differences in the Yemenite tradition of vocalization and which Israeli linguist, Shelomo Morag, believes reflects an ancient form of vocalizing the texts and was once known and used by all Hebrew-speakers.

Notes on transliteration: In the Yemenite Jewish tradition, the vowel '' qamaṣ'' }, represents . The Hebrew character ''Tau'' (), without a dot of accentuation, represents . The Hebrew character ''Gimal'' (), with a dot of accentuation, represents . The Hebrew word (in the above middle column, and meaning 'a thing detestable'), is written in Yemenite Jewish tradition with a vowel '' qamaṣ'' beneath the , but since it is followed by the letters it represents . The vowel ''ḥolam'' in the Yemenite dialect is transcribed here with , and represents a front rounded vowel. Another peculiarity with the Yemenite dialect is that the vast majority of Yemenite Jews (excluding the Jews of Sharab in Yemen) will replace , used here in transliteration of texts, with the phonetic sound of .

In the Yemenite tradition, the plural endings on the words (''merits''), (''kingdoms''), (''exiles''), (''errors''), (''defective animals'') and (''testimonies''), all differ from the way they are vocalized in Modern Hebrew. In Modern Hebrew, these words are marked with a ''shuraq'', as follows: – – – – – . Although the word (''kingdoms'') in Daniel 8:22 is vocalized ''malkhuyoth'', as it is in Modern Hebrew, Shelomo Morag thinks that the Yemenite tradition reflects a phonological phenomenon known as dissimilation

In phonology, particularly within historical linguistics, dissimilation is a phenomenon whereby similar consonants or vowels in a word become less similar or elided. In English, dissimilation is particularly common with liquid consonants such ...

, whereby similar consonants or vowels in a word become less similar. Others explain the discrepancy as being in accordance with a general rule of practice, prevalent in the 2nd century CE, where the Hebrew in rabbinic literature was distinguished from that of Biblical Hebrew, and put into an entire class and category of its own, with its own rules of vocalization (see ''infra'').

The Hebrew noun (''ḥăṯīkkah''), in the upper left column, is a word meaning "slice/piece" (in the absolute state), or ("piece of meat") in the construct state. The noun is of the same metre as (''qǝlipah''), a word meaning "peel," or the "rind" of a fruit. Both the ''kaph

Kaph (also spelled kaf) is the eleventh letter of the Semitic abjads, including Phoenician ''kāp'' 𐤊, Hebrew ''kāp̄'' , Aramaic ''kāp'' 𐡊, Syriac ''kāp̄'' ܟ, and Arabic ''kāf'' (in abjadi order). It is also related to the Anc ...

'' and '' pe'' in these nouns are with a ''dagesh''. However, the same roots applied to different meters, serving as gerunds, as in "slicing/cutting" eat

Eating (also known as consuming) is the ingestion of food. In biology, this is typically done to provide a heterotrophic organism with energy and nutrients and to allow for growth. Animals and other heterotrophs must eat in order to survive – ...

and "peeling" n apple the words would respectively be (''ḥăṯīḫah'') and (''qǝlīfah''), without a ''dagesh'' in the Hebrew characters ''Kaph

Kaph (also spelled kaf) is the eleventh letter of the Semitic abjads, including Phoenician ''kāp'' 𐤊, Hebrew ''kāp̄'' , Aramaic ''kāp'' 𐡊, Syriac ''kāp̄'' ܟ, and Arabic ''kāf'' (in abjadi order). It is also related to the Anc ...

'' and '' Pe'' (i.e. ''rafe'' letters), such as when the verb is used with the preposition "after": e.g. "after peeling the apple" = , or "after cutting the meat" = .

In the Talmud

The Talmud (; ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of Haskalah#Effects, modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the cen ...

(''Ḥullin'' 137b; ''Avodah Zarah'' 58b), the Sages of Israel had a practice to read words derived from the Scriptures in their own given way, while the same words derived from the Talmud or in other exegetical literature (known as the Midrash

''Midrash'' (;"midrash"

. ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. ; or ''midrashot' ...

) in a different way: "When Isse the son of Hinei went up . ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. ; or ''midrashot' ...

here

Here may refer to:

Music

* ''Here'' (Adrian Belew album), 1994

* ''Here'' (Alicia Keys album), 2016

* ''Here'' (Cal Tjader album), 1979

* ''Here'' (Edward Sharpe album), 2012

* ''Here'' (Idina Menzel album), 2004

* ''Here'' (Merzbow album), ...

he found Rabbi Yoḥanan teaching certain Mishnahto the creations, saying, ''raḥelim'' (i.e. = the Hebrew word for "ewes"), etc. He said to him, 'Teach it y its Mishnaic name = ''raḥeloth''!' He replied, ' hat I say isas it is written n the Scriptures Ewes (''raḥelim''), two-hundred.' (Gen. 32:15) He answered him, 'The language of the Torah is by itself, and the language employed by the Sages is by itself!'" ().

This passage from the Talmud is often quoted by grammarians of Yemenite origin to explain certain "discrepancies" found in vocalization of words where a comparable source can be found in the Hebrew Bible, such as the Yemenite tradition in rabbinic literature to say (''maʻbīr''), rather than (''maʻăvīr'') – although the latter rendering appears in Scripture (Deuteronomy 18:10), or to say (''zīʻah''), with ''ḥīraq'',Yosef Amar Halevi, ''Talmud Bavli Menuqad'', vol. 4, Jerusalem 1980, s.v. ''Pesaḥim'' 24b, et al. rather than, (''zeʻah''), with ''ṣerê'', although it too appears in Scripture (Genesis 3:19), or to say (''birkhath ha-mazon'') (= ''kaph

Kaph (also spelled kaf) is the eleventh letter of the Semitic abjads, including Phoenician ''kāp'' 𐤊, Hebrew ''kāp̄'' , Aramaic ''kāp'' 𐡊, Syriac ''kāp̄'' ܟ, and Arabic ''kāf'' (in abjadi order). It is also related to the Anc ...

'' rafe

In Hebrew orthography the rafe or raphe (, , meaning "weak, limp") is a diacritic (), a subtle horizontal overbar placed above certain letters to indicate that they are to be pronounced as fricatives.

It originated with the Tiberian Masoret ...

), rather than as the word "blessing" in the construct state which appears in the Scriptures (Genesis 28:4, et al.), e.g. ''birkath Avraham'' (), with ''kaph'' dagesh

The dagesh () is a diacritic that is used in the Hebrew alphabet. It takes the form of a dot placed inside a consonant. A dagesh can either indicate a "hard" plosive version of the consonant (known as , literally 'light dot') or that the conson ...

. Others, however, say that these anomalies reflect a tradition that antedates the Tiberian Masoretic texts.

Along these same lines, the Masoretic Text

The Masoretic Text (MT or 𝕸; ) is the authoritative Hebrew and Aramaic text of the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible (''Tanakh'') in Rabbinic Judaism. The Masoretic Text defines the Jewish canon and its precise letter-text, with its vocaliz ...

of the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

. '' demotic-forms, the Yemenites will pronounce these words as () and () = ''yovnei'' and ''lūd'', respectively. The use of the phoneme " ṣerê", represented by the two dots "◌ֵ", instead of "pataḥ-səġūl" ( ) for the word "Yavneh" may have been influenced by the Palestinian dialect spoken in the Land of Israel in the 1st-century CE. In Yemenite tradition, many words in both Biblical and Mishnaic Hebrew which are written with the final ''hê'' ending (without the ''mappîq'') are realized by a secondary

(Hebrew): A popular Yemenite ''alaph bei'' book. * (Hebrew) in Rabbi Yosef Qafih's ''Collected Papers'', volume 2, pages 958–960. *

''Sifra'' in the Babylonian supraliner punctuation

Manuscript: ''Vaticani ebraici 66'' (Late 9th-mid 10th century)

Pronunciation ChartPronunciation Chart (continued)Torah reading with ''Targum Onkelos''

read by Yemenite elder, Mori Shalom Cohen

Aleph be recording

(published b

http://www.temoni.org/?p=3652

. * Aharon Amram – Recordings:

Tunes of Yemen – Aharon Amram

for Android. *** ms://media.jvod.info/Nosach/Aharon_Amram/PARACHA/1_10_7_miketz.mp3 Cantillation of in Parshat Miketz(published b

Nosach Teiman

. *

Reading of Psalm 119

(published b

Nosach Teiman

. *

Yemenite reading of the complete Hallel

(published b

Nosach Teiman

. *

Piyyutim for Simchat Torah

disc 1. ***Megillat Eichah (portions thereof published b

Nosach Teiman

: **

Chapter 2

**

Chapter 4

**

Chapter 5

***Purim song

(published b

Nosach Teiman

.

1988 Selichot in a Rosh HaAyin synagogue

*Rabbi Yosef 'Amar – Recordings and Work:

(published b

Nosach Teiman

.

** Babylonian Talmud vowelized according to the tradition of the Jews of Yemen *

*

(fro

Nosach Teiman

*

(fro

Nosach Teiman

*Rabbi Yosef Qafih

Megillat Esther reading of Purim 1996

(until 2:5, from CD) *Rabbi Ratson 'Arusi – Recordings:

Ashmuroth in 1975 – Shabbazi Synagogue, Kiryat Onopreceded

by his introductory remarks)

David Ben-Abraham, 2005

On the Hebrew Language of Yemen

, 2005 (mostly unreferenced)

Rabbi Evin Sapir's Account of Yemenite Hebrew

(in Hebrew); free translation at http://www.chayas.com/evinsapir.doc

A non-Yemenite's efforts at imitation of Sana'ani Yemenite Pronunciation of Hebrew. {{DEFAULTSORT:Yemenite Hebrew

. '' demotic-forms, the Yemenites will pronounce these words as () and () = ''yovnei'' and ''lūd'', respectively. The use of the phoneme " ṣerê", represented by the two dots "◌ֵ", instead of "pataḥ-səġūl" ( ) for the word "Yavneh" may have been influenced by the Palestinian dialect spoken in the Land of Israel in the 1st-century CE. In Yemenite tradition, many words in both Biblical and Mishnaic Hebrew which are written with the final ''hê'' ending (without the ''mappîq'') are realized by a secondary

glottal stop

The glottal stop or glottal plosive is a type of consonantal sound used in many Speech communication, spoken languages, produced by obstructing airflow in the vocal tract or, more precisely, the glottis. The symbol in the International Phonetic ...

, meaning, they are abruptly cut short, as when one holds his breath. Shelomo Morag who treats upon this peculiarity in the Yemenite tradition of vocalization brings down two examples from the Book of Isaiah, although by no means exclusive, where he shows the transliteration for the words in Isaiah 1:27 and in Isaiah 2:5, and both of which represent , as in ''tippoːdä(ʔ)'' and ''wǝnelăχoː(ʔ)'' respectively. The word (Bible Codex) in the upper-middle column is pronounced in the same way, e.g. .

Excursus: The preposition () is unique in the Yemenite Jewish tradition. The Hebrew preposition is always written with the noun, joined as one word, and the ''lamed'' is always accentuated with a ''dagesh''. For example, if the noun , would normally have been written with the definite article , as in , and the noun was to show possession, as in the sentence: "the palace ''of'' the king," the definite article "the" (Hebrew: ) is dropped, but the same vowel ''pataḥ'' of the definite article is carried over to the ''lamed'', as in , instead of של המלך. The vowel on the ''lamed'' will sometimes differ, depending on what noun comes after the preposition. For example, the definite article "the" in Hebrew nouns which begin with ''aleph'' or ''resh'' and sometimes ''ayin'', such as in and in , or in , is written with the vowel ''qamaṣ'' – in which case, the vowel ''qamaṣ'' is carried over to the ''lamed'', as in and in and in . Another general rule is that whenever a possessive noun is written without the definite article "the", as in the words, "a king's sceptre," or "the sceptre of a king" (Heb. ), the ''lamed'' in the preposition is written with the vowel ''shǝwa'' (i.e. mobile ''shǝwa''), as in , and as in, "if it belongs to Israel" ⇒ . Whenever the noun begins with a ''shǝwa'', as in the proper noun ''Solomon'' (Heb. ) and one wanted to show possession, the ''lamed'' in the preposition is written with a ''ḥiraq'', as in (''Song of Solomon'' 3:7): ⇒ "Solomon's bed", or as in ⇒ "the punishment the wicked", or in ⇒ "a bundle heave-offering."

Another rule of practice in Hebrew grammar is that two ''shǝwa''s are never written one after the other at the beginning of any word; neither can two ''ḥaṭaf pataḥ''s or two ''ḥaṭaf sǝġūl''s be written at the beginning of a word one after the other. The practical implication arising from this rule is that when there is a noun beginning with a ''ḥaṭaf pataḥ'', as in the word, ⇒ "her companion", and one wishes to add thereto the preposition "to" – as in, "to her companion" ⇒ , the ''lamed'' is written with the vowel ''pataḥ'', instead of a ''shǝwa'' (i.e. a mobile ''shǝwa''), seeing that the ''shǝwa'' at the beginning of a word and the ''ḥaṭaf pataḥ'', as well as the ''ḥaṭaf sǝġūl'', are all actually one and the same vowel (in the Babylonian tradition), and it is as though he had written two ''shǝwa''s one after the other. Likewise, in the possessive case, "belonging to her companion" ⇒ , the ''lamed'' in the preposition is written with the vowel ''pataḥ''.

Hebrew vernacular

The Leiden MS. of theJerusalem Talmud

The Jerusalem Talmud (, often for short) or Palestinian Talmud, also known as the Talmud of the Land of Israel, is a collection of rabbinic notes on the second-century Jewish oral tradition known as the Mishnah. Naming this version of the Talm ...

is important in that it preserves some earlier variants to textual readings of that Talmud, such as in Tractate ''Pesaḥim'' 10:3 (70a), which brings down the old Palestinian-Hebrew word for ''charoseth'' (the sweet relish eaten at Passover), viz. ''dūkeh'' (), instead of ''rūbeh/rabah'' (), saying with a play on words: "The members of Isse's household would say in the name of Isse: Why is it called ''dūkeh''? It is because she pounds he spiced ingredientswith him." The Hebrew word for "pound" is ''dakh'' (), which rules out the spelling of " ''rabah'' " (), as found in the printed editions. Today, the Jews of Yemen

Yemenite Jews, also known as Yemeni Jews or Teimanim (from ; ), are a Jewish diaspora group who live, or once lived, in Yemen, and their descendants maintaining their customs. After several waves of persecution, the vast majority of Yemenite J ...

, in their vernacular of Hebrew, still call the ''charoseth'' by the name ''dūkeh''.

Other quintessential Hebrew words which have been preserved by the Jews of Yemen

Yemenite Jews, also known as Yemeni Jews or Teimanim (from ; ), are a Jewish diaspora group who live, or once lived, in Yemen, and their descendants maintaining their customs. After several waves of persecution, the vast majority of Yemenite J ...

is their manner of calling a receipt of purchase by the name, ''roʔoːyoː'' (), rather than the word "''qabbalah''" that is now used in Modern Hebrew. The weekly biblical lection read on Sabbath days is called by the name ''seder'' (), since the word ''parashah'' () has a completely different meaning, denoting a Bible Codex

The codex (: codices ) was the historical ancestor format of the modern book. Technically, the vast majority of modern books use the codex format of a stack of pages bound at one edge, along the side of the text. But the term ''codex'' is now r ...

containing the first Five Books of Moses (plural: codices = ).

Charity; alms (, ''miṣwoː''), so-called in Yemenite Jewish parlance, was usually in the form of bread, collected in baskets each Friday before the Sabbath by those appointed over this task for distribution among the needy, without them being brought to shame. The same word is often used throughout the Jerusalem Talmud

The Jerusalem Talmud (, often for short) or Palestinian Talmud, also known as the Talmud of the Land of Israel, is a collection of rabbinic notes on the second-century Jewish oral tradition known as the Mishnah. Naming this version of the Talm ...

, as well as in Midrashic literature, to signify what is given out to the poor and needy. Today, in Modern Hebrew

Modern Hebrew (, or ), also known as Israeli Hebrew or simply Hebrew, is the Standard language, standard form of the Hebrew language spoken today. It is the only surviving Canaanite language, as well as one of the List of languages by first w ...

, the word is seldom used to imply charity, replaced now by the word, ''ts’dakah'' (Heb. ). In contrast, the word amongst Jews in Sana’a was a tax levied upon Jewish householders, particularly those whose professions were butchers, and which tax consisted of hides and suet

Suet ( ) is the raw, hard fat of beef, lamb or mutton found around the loins and kidneys.

Suet has a melting point of between and solidification (or congelation) between . Its high smoke point makes it ideal for deep frying and pastr ...

from butchered animals, and which things were sold on a daily basis by the Treasurer, and the money accruing from the sale committed to the public fund for the Jewish poor of the city, which money was distributed to the city's poor twice a year; once on Passover, and once on Sukkot. The fund itself was known by the name ''toːḏer'' (), lit. "the constant evenues"

Although Jews in Yemen widely made-use of the South-Arabic word ''mukhwāṭ'' () for the "metal pointer" (stylus) used in pointing at the letters of sacred writ, they also knew the old Hebrew word for the same, which they called ''makhtev'' (). The following story is related about this instrument in Midrash Rabba: "Rabban himonGamliel says: ‘Five-hundred schools were in Beter, while the smallest of them wasn’t less than three-hundred children. They used to say, ‘If the enemy should ever come upon us, with these ''metal pointers'' () we’ll go out against them and stab them!’..."

In other peculiar words of interest, they made use of the word, ''shilṭön'' (), for "governor" or "king," instead of "government," the latter word now being the more common usage in Modern Hebrew; ''kothev'' (), for "scrivener", or copyist of religious texts, instead of the word "sofer" (scribe); ''ṣibbūr'' (), for "a quorum of at least ten adult males," a word used in Yemen instead of the Modern Hebrew word, ''minyan''; ''ḥefeṣ'' (), a noun meaning "desirable thing," was used by them to describe any "book" (especially one of a prophylactic nature), although now in Modern Hebrew it means "object"; ''fiqfūq'' () had the connotation of "shock," "violent agitation," or "shaking-up," although today, in Modern Hebrew, it has the meaning of "doubt" or "skepticism"; the word, ''harpathqe'' (), was used to describe "great hardships," although in Modern Hebrew the word has come to mean "adventures." The word ''fazmūn'' (), any happy liturgical poem, such as those sung on ''Simhat Torah

Simchat Torah (; Ashkenazi: ), also spelled Simhat Torah, is a Jewish holiday that celebrates and marks the conclusion of the annual cycle of public Torah readings, and the beginning of a new cycle. Simchat Torah is a component of the Hebrew Bible ...

'', differs from today's Modern Hebrew word, ''pizmon'' (), meaning, a "chorus" to a song. Another peculiar aspect of Yemenite Hebrew is what concerns denominative verbs. One of the nouns used for bread (made of wheat) is ''himmuṣ'' (), derived from the blessing that is said whenever breaking bread, = ''He that brings forth'' read from the earth Whenever they wanted to say its imperative form, "break bread!", they made use of the denominative verb ''hammeṣ''! (). Similarly, the noun for the Third Sabbath meal was ''qiyyūm'' (), literally meaning "observance," in which they made use of the denominative verb, ''tǝqayyem'' () = ''Will you eat with us'' (the Third Sabbath meal)?, or, = ''Let us eat'' (the Third Sabbath meal), or, ''qiyam'' () = ''He ate'' (the Third Sabbath meal).Yehuda Ratzaby, ''Dictionary of the Hebrew Language used by Yemenite Jews'' (), Tel-Aviv 1978, s.v. (p. 247).

See also

*Jewish customs of etiquette

''Minhag'' ( "custom", classical pl. מנהגות, modern pl. מנהגים, ''minhagim'') is an accepted tradition or group of traditions in Judaism. A related concept, '' Nusach'' (נוסח), refers to the traditional order and form of the pra ...

* Yemenite Jewish poetry

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * (Cited in article by Yehuda Ratzaby who quotes from Kitāb al-Ānwār, ed. Leon Nemoy) * * * * (Hebrew) * (Hebrew) * * (German) *Further reading

*S. Morag, 'Pronunciations of Hebrew', Encyclopaedia Judaica XIII, 1120–1145 * *Yeivin, I., ''The Hebrew Language Tradition as Reflected in the Babylonian Vocalization'': Jerusalem 1985 (Hebrew) * (Hebrew), beginning on page 50 in Halichoth Teiman (1963). * (Hebrew) in Rabbi Yosef Qafih's ''Collected Papers'', volume 2, pages 931–936.(Hebrew): A popular Yemenite ''alaph bei'' book. * (Hebrew) in Rabbi Yosef Qafih's ''Collected Papers'', volume 2, pages 958–960. *

External links

''Sifra'' in the Babylonian supraliner punctuation

Manuscript: ''Vaticani ebraici 66'' (Late 9th-mid 10th century)

Pronunciation Chart

read by Yemenite elder, Mori Shalom Cohen

Aleph be recording

(published b

http://www.temoni.org/?p=3652

. * Aharon Amram – Recordings:

Tunes of Yemen – Aharon Amram

for Android. *** ms://media.jvod.info/Nosach/Aharon_Amram/PARACHA/1_10_7_miketz.mp3 Cantillation of in Parshat Miketz(published b

Nosach Teiman

. *

Reading of Psalm 119

(published b

Nosach Teiman

. *

Yemenite reading of the complete Hallel

(published b

Nosach Teiman

. *

Piyyutim for Simchat Torah

disc 1. ***Megillat Eichah (portions thereof published b

Nosach Teiman

: **

Chapter 2

**

Chapter 4

**

Chapter 5

***Purim song

(published b

Nosach Teiman

.

1988 Selichot in a Rosh HaAyin synagogue

*Rabbi Yosef 'Amar – Recordings and Work:

(published b

Nosach Teiman

.

** Babylonian Talmud vowelized according to the tradition of the Jews of Yemen *

*

(fro

Nosach Teiman

*

(fro

Nosach Teiman

*Rabbi Yosef Qafih

Megillat Esther reading of Purim 1996

(until 2:5, from CD) *Rabbi Ratson 'Arusi – Recordings:

Ashmuroth in 1975 – Shabbazi Synagogue, Kiryat Ono

by his introductory remarks)

David Ben-Abraham, 2005

On the Hebrew Language of Yemen

, 2005 (mostly unreferenced)

Rabbi Evin Sapir's Account of Yemenite Hebrew

(in Hebrew); free translation at http://www.chayas.com/evinsapir.doc

A non-Yemenite's efforts at imitation of Sana'ani Yemenite Pronunciation of Hebrew. {{DEFAULTSORT:Yemenite Hebrew

Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

Languages of Israel

Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...