Yellowstone National Park on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Yellowstone National Park is a national park of the United States located in the northwest corner of

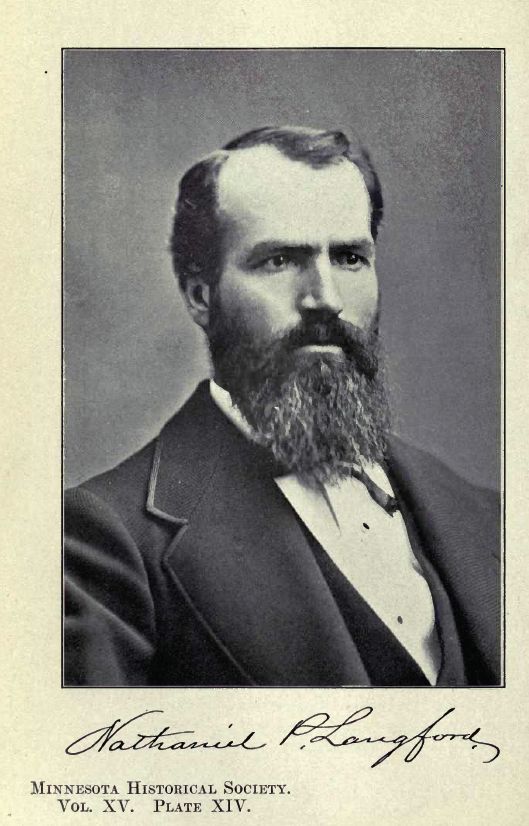

The first detailed expedition to the Yellowstone area was the Cook–Folsom–Peterson Expedition of 1869, which consisted of three privately funded explorers. The Folsom party followed the Yellowstone River to Yellowstone Lake. The members of the Folsom party kept a journal and based on the information it reported, a party of Montana residents organized the Washburn–Langford–Doane Expedition in 1870. It was headed by the surveyor-general of Montana Henry Washburn, and included Nathaniel P. Langford (who later became known as "National Park" Langford) and a U.S. Army detachment commanded by Lt. Gustavus Doane. The expedition spent about a month exploring the region, collecting specimens, and naming sites of interest.

A Montana writer and lawyer named Cornelius Hedges, who had been a member of the Washburn expedition, proposed that the region should be set aside and protected as a national park; he wrote detailed articles about his observations for the ''Helena Herald'' newspaper between 1870 and 1871. Hedges essentially restated comments made in October 1865 by acting Montana Territorial Governor Thomas Francis Meagher, who had previously commented that the region should be protected. Others made similar suggestions. An 1871 letter to Ferdinand V. Hayden from

The first detailed expedition to the Yellowstone area was the Cook–Folsom–Peterson Expedition of 1869, which consisted of three privately funded explorers. The Folsom party followed the Yellowstone River to Yellowstone Lake. The members of the Folsom party kept a journal and based on the information it reported, a party of Montana residents organized the Washburn–Langford–Doane Expedition in 1870. It was headed by the surveyor-general of Montana Henry Washburn, and included Nathaniel P. Langford (who later became known as "National Park" Langford) and a U.S. Army detachment commanded by Lt. Gustavus Doane. The expedition spent about a month exploring the region, collecting specimens, and naming sites of interest.

A Montana writer and lawyer named Cornelius Hedges, who had been a member of the Washburn expedition, proposed that the region should be set aside and protected as a national park; he wrote detailed articles about his observations for the ''Helena Herald'' newspaper between 1870 and 1871. Hedges essentially restated comments made in October 1865 by acting Montana Territorial Governor Thomas Francis Meagher, who had previously commented that the region should be protected. Others made similar suggestions. An 1871 letter to Ferdinand V. Hayden from

In 1871, eleven years after his failed first effort, Ferdinand V. Hayden was finally able to explore the region. With government sponsorship, he returned to the region with a second, larger expedition, the Hayden Geological Survey of 1871. He compiled a comprehensive report, including large-format photographs by William Henry Jackson and paintings by Thomas Moran. The report helped to convince the U.S. Congress to withdraw this region from

In 1871, eleven years after his failed first effort, Ferdinand V. Hayden was finally able to explore the region. With government sponsorship, he returned to the region with a second, larger expedition, the Hayden Geological Survey of 1871. He compiled a comprehensive report, including large-format photographs by William Henry Jackson and paintings by Thomas Moran. The report helped to convince the U.S. Congress to withdraw this region from  There was considerable local opposition to Yellowstone National Park during its early years. Some of the locals feared that the regional economy would be unable to thrive if there remained strict federal prohibitions against resource development or settlement within park boundaries and local entrepreneurs advocated reducing the size of the park so that mining, hunting, and logging activities could be developed. To this end, numerous bills were introduced into Congress by Montana representatives who sought to remove the federal land-use restrictions.

After the park's official formation, Nathaniel Langford was appointed as the park's first superintendent in 1872 by the Secretary of Interior Columbus Delano, the first overseer and controller of the park. Langford served for five years but was denied a salary, funding, and staff. Langford lacked the means to improve the land or properly protect the park, and without formal policy or regulations, he had few legal methods to enforce such protection. This left Yellowstone vulnerable to

There was considerable local opposition to Yellowstone National Park during its early years. Some of the locals feared that the regional economy would be unable to thrive if there remained strict federal prohibitions against resource development or settlement within park boundaries and local entrepreneurs advocated reducing the size of the park so that mining, hunting, and logging activities could be developed. To this end, numerous bills were introduced into Congress by Montana representatives who sought to remove the federal land-use restrictions.

After the park's official formation, Nathaniel Langford was appointed as the park's first superintendent in 1872 by the Secretary of Interior Columbus Delano, the first overseer and controller of the park. Langford served for five years but was denied a salary, funding, and staff. Langford lacked the means to improve the land or properly protect the park, and without formal policy or regulations, he had few legal methods to enforce such protection. This left Yellowstone vulnerable to  The Northern Pacific Railroad built a train station in

The Northern Pacific Railroad built a train station in

By 1915, 1,000 automobiles per year were entering the park, resulting in conflicts with horses and horse-drawn transportation. Horse travel on roads was eventually prohibited.

The

By 1915, 1,000 automobiles per year were entering the park, resulting in conflicts with horses and horse-drawn transportation. Horse travel on roads was eventually prohibited.

The  The 1959 Hebgen Lake earthquake just west of Yellowstone at Hebgen Lake damaged roads and some structures in the park. In the northwest section of the park, new geysers were found, and many existing hot springs became turbid. It was the most powerful earthquake to hit the region in recorded history.

In 1963, after several years of public controversy regarding the forced reduction of the elk population in Yellowstone, the United States Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall appointed an advisory board to collect scientific data to inform future wildlife management of the national parks. In a paper known as the Leopold Report, the committee observed that culling programs at other national parks had been ineffective, and recommended the management of Yellowstone's elk population.

The

The 1959 Hebgen Lake earthquake just west of Yellowstone at Hebgen Lake damaged roads and some structures in the park. In the northwest section of the park, new geysers were found, and many existing hot springs became turbid. It was the most powerful earthquake to hit the region in recorded history.

In 1963, after several years of public controversy regarding the forced reduction of the elk population in Yellowstone, the United States Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall appointed an advisory board to collect scientific data to inform future wildlife management of the national parks. In a paper known as the Leopold Report, the committee observed that culling programs at other national parks had been ineffective, and recommended the management of Yellowstone's elk population.

The

The expansive cultural history of the park has been documented by the 1,000 archeological sites that have been discovered. The park has 1,106 historic structures and features, and of these Obsidian Cliff and five buildings have been designated

The expansive cultural history of the park has been documented by the 1,000 archeological sites that have been discovered. The park has 1,106 historic structures and features, and of these Obsidian Cliff and five buildings have been designated

Yellowstone National Park occupies a roughly square parcel of volcanic complex that jogs slightly beyond the northwestern corner of Wyoming. Approximately 96 percent of the total land area of Yellowstone National Park is located within the state of Wyoming. Another three percent is within Montana, with the remaining one percent in Idaho. Montana's portion of Yellowstone contains multiple trails, facilities and swimming holes, while the Idaho portion of the park is completely undeveloped. The irregular eastern boundary of the national park follows the height of land along the Absaroka Range.

The park is north to south, and west to east by air. Yellowstone is in area, larger than either of the states of

Yellowstone National Park occupies a roughly square parcel of volcanic complex that jogs slightly beyond the northwestern corner of Wyoming. Approximately 96 percent of the total land area of Yellowstone National Park is located within the state of Wyoming. Another three percent is within Montana, with the remaining one percent in Idaho. Montana's portion of Yellowstone contains multiple trails, facilities and swimming holes, while the Idaho portion of the park is completely undeveloped. The irregular eastern boundary of the national park follows the height of land along the Absaroka Range.

The park is north to south, and west to east by air. Yellowstone is in area, larger than either of the states of

Yellowstone is at the northeastern end of the Snake River Plain, a great bow-shaped arc through the mountains that extends roughly from the park to the Idaho-Oregon border.

The volcanism of Yellowstone is believed to be linked to the somewhat older volcanism of the Snake River Plain. Yellowstone is thus the active part of a hotspot that the North American Plate has moved over in a southwest direction over time. The origin of this hotspot volcanism is disputed. One theory holds that a

Yellowstone is at the northeastern end of the Snake River Plain, a great bow-shaped arc through the mountains that extends roughly from the park to the Idaho-Oregon border.

The volcanism of Yellowstone is believed to be linked to the somewhat older volcanism of the Snake River Plain. Yellowstone is thus the active part of a hotspot that the North American Plate has moved over in a southwest direction over time. The origin of this hotspot volcanism is disputed. One theory holds that a

Yellowstone experiences thousands of small earthquakes every year, virtually all of which are undetectable to people. About 2/3 of the earthquakes occur in an area between Hegben Lake and the Yellowstone Caldera along a buried fracture zone left from the 2.1 mya eruption.

There have been six earthquakes with at least

Yellowstone experiences thousands of small earthquakes every year, virtually all of which are undetectable to people. About 2/3 of the earthquakes occur in an area between Hegben Lake and the Yellowstone Caldera along a buried fracture zone left from the 2.1 mya eruption.

There have been six earthquakes with at least

Yellowstone National Park is the centerpiece of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, a region that includes Grand Teton National Park, adjacent National Forests and expansive

Yellowstone National Park is the centerpiece of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, a region that includes Grand Teton National Park, adjacent National Forests and expansive

There are dozens of species of flowering plants that have been identified, most of which bloom between May and September. The Yellowstone sand verbena is a rare flowering plant found only in Yellowstone. It is closely related to species usually found in much warmer climates, making the sand verbena an enigma. The estimated 8,000 examples of this rare flowering plant all make their home in the sandy soils on the shores of Yellowstone Lake, well above the waterline.

In Yellowstone's hot waters, bacteria form mats of bizarre shapes consisting of trillions of organisms. These bacteria are some of the most primitive life forms on earth. Flies and other

There are dozens of species of flowering plants that have been identified, most of which bloom between May and September. The Yellowstone sand verbena is a rare flowering plant found only in Yellowstone. It is closely related to species usually found in much warmer climates, making the sand verbena an enigma. The estimated 8,000 examples of this rare flowering plant all make their home in the sandy soils on the shores of Yellowstone Lake, well above the waterline.

In Yellowstone's hot waters, bacteria form mats of bizarre shapes consisting of trillions of organisms. These bacteria are some of the most primitive life forms on earth. Flies and other

The Yellowstone Park bison herd is believed to be one of only four free-roaming and genetically pure herds on public lands in North America. The other three herds are the Henry Mountains bison herd of

The Yellowstone Park bison herd is believed to be one of only four free-roaming and genetically pure herds on public lands in North America. The other three herds are the Henry Mountains bison herd of  Starting in 1914, to protect elk populations, the U.S. Congress appropriated funds to be used for "destroying wolves,

Starting in 1914, to protect elk populations, the U.S. Congress appropriated funds to be used for "destroying wolves,

''nps.gov''. National Park Service. October 5, 2018. from the original on October 13, 2018. Retrieved December 19, 2018. Opponents of delisting the grizzly expressed concerns that states might once again allow hunting and that better conservation measures were needed to ensure a sustainable population. A federal district judge overturned the delisting ruling in 2009, reinstating the grizzly. The grizzly was once again removed from the list in 2017. In September 2018, a U.S. district judge ruled that the grizzly's protections must be restored in full, arguing the Fish and Wildlife Service was mistaken in removing the bear from the threatened status list. Hunting is prohibited within Yellowstone National Park while hunters may transport the carcass through the park with a permit. Population figures for elk are more than 30,000—the largest population of any large mammal species in Yellowstone. The northern herd has decreased enormously since the mid‑1990s; this has been attributed to wolf predation and causal effects such as elk using more forested regions to evade

Population figures for elk are more than 30,000—the largest population of any large mammal species in Yellowstone. The northern herd has decreased enormously since the mid‑1990s; this has been attributed to wolf predation and causal effects such as elk using more forested regions to evade  Eighteen species of fish live in Yellowstone, including the core range of the Yellowstone cutthroat trout—a fish highly sought by anglers. The Yellowstone cutthroat trout has faced several threats since the 1980s, including the suspected illegal introduction into Yellowstone Lake of

Eighteen species of fish live in Yellowstone, including the core range of the Yellowstone cutthroat trout—a fish highly sought by anglers. The Yellowstone cutthroat trout has faced several threats since the 1980s, including the suspected illegal introduction into Yellowstone Lake of

As

As  To minimize the chances of out-of-control fires and threats to people and structures, park employees do more than just monitor the potential for fire.

To minimize the chances of out-of-control fires and threats to people and structures, park employees do more than just monitor the potential for fire.  The spring season of 1988 was wet, but by summer, drought began moving in throughout the northern Rockies, creating the driest year on record to that point. Grasses and plants which grew well in the early summer from the abundant spring moisture produced plenty of grass, which soon turned to dry tinder. The National Park Service began firefighting efforts to keep the fires under control, but the extreme drought made suppression difficult. Between July 15 and 21, 1988, fires quickly spread from throughout the entire Yellowstone region, which included areas outside the park, to on the park land alone. By the end of the month, the fires were out of control. Large fires burned together, and on August 20, 1988, the single worst day of the fires, more than were consumed. Seven large fires were responsible for 95% of the that were burned over the next couple of months. The cost of 25,000 firefighters and U.S. military forces participating in the suppression efforts was 120 million dollars. By the time winter brought snow that helped extinguish the last flames, the fires had destroyed 67 structures and caused several million dollars in damage. Though no civilians died, two personnel associated with the firefighting efforts were killed.

Contrary to media reports and speculation at the time, the fires killed very few park animals—surveys indicated that only about 345 elk (of an estimated 40,000–50,000), 36 deer, 12 moose, 6 black bears, and 9 bison had perished. Changes in fire management policies were implemented by land management agencies throughout the United States, based on knowledge gained from the 1988 fires and the evaluation of scientists and experts from various fields. By 1992, Yellowstone had adopted a new fire management plan which observed stricter guidelines for the management of natural fires.

The spring season of 1988 was wet, but by summer, drought began moving in throughout the northern Rockies, creating the driest year on record to that point. Grasses and plants which grew well in the early summer from the abundant spring moisture produced plenty of grass, which soon turned to dry tinder. The National Park Service began firefighting efforts to keep the fires under control, but the extreme drought made suppression difficult. Between July 15 and 21, 1988, fires quickly spread from throughout the entire Yellowstone region, which included areas outside the park, to on the park land alone. By the end of the month, the fires were out of control. Large fires burned together, and on August 20, 1988, the single worst day of the fires, more than were consumed. Seven large fires were responsible for 95% of the that were burned over the next couple of months. The cost of 25,000 firefighters and U.S. military forces participating in the suppression efforts was 120 million dollars. By the time winter brought snow that helped extinguish the last flames, the fires had destroyed 67 structures and caused several million dollars in damage. Though no civilians died, two personnel associated with the firefighting efforts were killed.

Contrary to media reports and speculation at the time, the fires killed very few park animals—surveys indicated that only about 345 elk (of an estimated 40,000–50,000), 36 deer, 12 moose, 6 black bears, and 9 bison had perished. Changes in fire management policies were implemented by land management agencies throughout the United States, based on knowledge gained from the 1988 fires and the evaluation of scientists and experts from various fields. By 1992, Yellowstone had adopted a new fire management plan which observed stricter guidelines for the management of natural fires.

Yellowstone's climate is greatly influenced by altitude, with lower elevations generally found to be warmer year-round. The record high temperature was in 2002, while the coldest temperature recorded is in 1933. During the summer months of June to early September, daytime highs are normally in the range, while nighttime lows can go to below freezing (0 °C), especially at higher altitudes. Summer afternoons are frequently accompanied by

Yellowstone's climate is greatly influenced by altitude, with lower elevations generally found to be warmer year-round. The record high temperature was in 2002, while the coldest temperature recorded is in 1933. During the summer months of June to early September, daytime highs are normally in the range, while nighttime lows can go to below freezing (0 °C), especially at higher altitudes. Summer afternoons are frequently accompanied by

Park service roads lead to major features; however, road reconstruction has produced temporary road closures. Yellowstone is in the midst of a long-term road reconstruction effort, which is hampered by a short repair season. In the winter, all roads aside from the one which enters from

Park service roads lead to major features; however, road reconstruction has produced temporary road closures. Yellowstone is in the midst of a long-term road reconstruction effort, which is hampered by a short repair season. In the winter, all roads aside from the one which enters from

The entire park is within the jurisdiction of the United States District Court for the District of Wyoming, making it the only federal court district that includes portions of more than one state (Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming). Law professor Brian C. Kalt has argued that it may be impossible to impanel a jury in compliance with the Vicinage Clause of the Sixth Amendment for a crime committed solely in the unpopulated Idaho portion of the park (and that it would be difficult to do so for a crime committed solely in the lightly populated Montana portion). One defendant, who was accused of a wildlife-related crime in the Montana portion of the park, attempted to raise this argument but eventually pleaded guilty, with the plea deal including his specific agreement not to raise the issue in his appeal.

The entire park is within the jurisdiction of the United States District Court for the District of Wyoming, making it the only federal court district that includes portions of more than one state (Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming). Law professor Brian C. Kalt has argued that it may be impossible to impanel a jury in compliance with the Vicinage Clause of the Sixth Amendment for a crime committed solely in the unpopulated Idaho portion of the park (and that it would be difficult to do so for a crime committed solely in the lightly populated Montana portion). One defendant, who was accused of a wildlife-related crime in the Montana portion of the park, attempted to raise this argument but eventually pleaded guilty, with the plea deal including his specific agreement not to raise the issue in his appeal.

Also see, cited by the article: - The author was at the time an employee of the National Park Service. Circa the 1880s there were education programs for dependent children in the Mammoth area, involving a person hired to teach via money from parents or a soldier providing such services. Some residents chose to send their children to schools in locations towards the east of the country or in Bozeman. In 1921 the Mammoth School, created by the Park Service, opened. By 2008 more and more Yellowstone employees only were in Yellowstone during park season, and fewer employees had dependent children. Additionally, the interstate agreement to send Wyoming money to Montana was made circa that year. For those two reasons, in 2008 the Mammoth School closed.

Also see, cited by the article: - The author was at the time an employee of the National Park Service.

online

* Christiansen, Robert L., and H. Richard Blank Jr. "Geology of Yellowstone National Park." (US Geological Survey professional paper, 1972)

online

* Fournier, Robert O. "Geochemistry and dynamics of the Yellowstone National Park hydrothermal system." ''Annual review of earth and planetary sciences'' 17.1 (1989): 13–53

* Gunther, Kerry A. "Bear management in Yellowstone National Park, 1960-93." in ''Bears: their biology and management'' (1994): 549–560

online

* Keefer, William R. ''The geologic story of Yellowstone National Park'' (US Government Printing Office, 1971

online

* Haines, Aubrey L. ''Yellowstone National Park: its exploration and establishment'' (US National Park Service, 1974

online

* Jackson, W. Turrentine. "The Creation of Yellowstone National Park." '' Mississippi Valley Historical Review'' 29.2 (1942): 187–206

online

* Whittlesey, Lee H. (2002), "Native Americans, the Earliest Interpreters: What is Known About Their Legends and Stories of Yellowstone National Park and the Complexities of Interpreting Them", ''The George Wright Forum'', published by the George Wright Society, Vol. 19, No. 3, pp. 40–51. .

Travertine: Yellowstone's Hydrothermal Timekeeper

USGS May 24, 2021

from th

Library of Congress

The Yellowstone magmatic system from the mantle plume to the upper crust

a

Science

(registration required)

BYU Larsen Yellowstone collection

at the L. Tom Perry Special Collections Library of

Yellowstone articles, photos and videos

a

National Geographic

Photographic library of the U.S. Geological Survey

() * * * *

Wyoming

Wyoming ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States, Western United States. It borders Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho t ...

, with small portions extending into Montana

Montana ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota to the east, South Dakota to the southeast, Wyoming to the south, an ...

and Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest and Mountain states, Mountain West subregions of the Western United States. It borders Montana and Wyoming to the east, Nevada and Utah to the south, and Washington (state), ...

. It was established by the 42nd U.S. Congress through the Yellowstone National Park Protection Act and signed into law by President Ulysses S. Grant on March 1, 1872. Yellowstone was the first national park in the US, and is also widely understood to be the first national park in the world. The park is known for its wildlife and its many geothermal features, especially the Old Faithful

Old Faithful is a cone geyser in Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming, United States. It was named in 1870 during the Washburn–Langford–Doane Expedition and was the first geyser in the park to be named. It is a highly predictable geotherma ...

geyser

A geyser (, ) is a spring with an intermittent water discharge ejected turbulently and accompanied by steam. The formation of geysers is fairly rare and is caused by particular hydrogeological conditions that exist only in a few places on Ea ...

, one of its most popular. While it represents many types of biome

A biome () is a distinct geographical region with specific climate, vegetation, and animal life. It consists of a biological community that has formed in response to its physical environment and regional climate. In 1935, Tansley added the ...

s, the subalpine

Montane ecosystems are found on the slopes of mountains. The alpine climate in these regions strongly affects the ecosystem because temperatures fall as elevation increases, causing the ecosystem to stratify. This stratification is a crucial f ...

forest is the most abundant. It is part of the South Central Rockies forests ecoregion

An ecoregion (ecological region) is an ecological and geographic area that exists on multiple different levels, defined by type, quality, and quantity of environmental resources. Ecoregions cover relatively large areas of land or water, and c ...

.

While Native Americans have lived in the Yellowstone region for at least 11,000 years, aside from visits by mountain men during the early-to-mid-19th century, organized exploration did not begin until the late 1860s. Management and control of the park originally fell under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Department of the Interior, the first secretary of the interior to supervise the park being Columbus Delano. However, the U.S. Army was eventually commissioned to oversee the management of Yellowstone for 30 years between 1886 and 1916. In 1917, the administration of the park was transferred to the National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an List of federal agencies in the United States, agency of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government, within the US Department of the Interior. The service manages all List ...

, which had been created the previous year. Hundreds of structures have been built and are protected for their architectural and historical significance, and researchers have examined more than one thousand indigenous archaeological site

An archaeological site is a place (or group of physical sites) in which evidence of past activity is preserved (either prehistoric or recorded history, historic or contemporary), and which has been, or may be, investigated using the discipline ...

s.

Yellowstone National Park spans an area of , with lakes, canyons, rivers, and mountain range

A mountain range or hill range is a series of mountains or hills arranged in a line and connected by high ground. A mountain system or mountain belt is a group of mountain ranges with similarity in form, structure, and alignment that have aris ...

s. Yellowstone Lake is one of the largest high-elevation lakes in North America and covers part of the Yellowstone Caldera, the largest super volcano on the continent. The caldera

A caldera ( ) is a large cauldron-like hollow that forms shortly after the emptying of a magma chamber in a volcanic eruption. An eruption that ejects large volumes of magma over a short period of time can cause significant detriment to the str ...

is considered a dormant volcano

A volcano is commonly defined as a vent or fissure in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most often ...

. It has erupted with tremendous force twice in the last two million years. Well over half of the world's geysers and hydrothermal features are in Yellowstone, fueled by this ongoing volcanism. Lava

Lava is molten or partially molten rock (magma) that has been expelled from the interior of a terrestrial planet (such as Earth) or a Natural satellite, moon onto its surface. Lava may be erupted at a volcano or through a Fissure vent, fractu ...

flows and rocks from volcanic eruptions cover most of the land area of Yellowstone. The park is the centerpiece of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, the largest remaining nearly intact ecosystem in the Earth's northern temperate zone. In 1978, Yellowstone was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site

World Heritage Sites are landmarks and areas with legal protection under an treaty, international treaty administered by UNESCO for having cultural, historical, or scientific significance. The sites are judged to contain "cultural and natural ...

.

Hundreds of species of mammals, birds, fish, reptiles, and amphibians have been documented, including several that are either endangered

An endangered species is a species that is very likely to become extinct in the near future, either worldwide or in a particular political jurisdiction. Endangered species may be at risk due to factors such as habitat loss, poaching, inv ...

or threatened. The vast forests and grasslands also include unique species of plants. Yellowstone Park is the largest and most famous megafauna

In zoology, megafauna (from Ancient Greek, Greek μέγας ''megas'' "large" and Neo-Latin ''fauna'' "animal life") are large animals. The precise definition of the term varies widely, though a common threshold is approximately , this lower en ...

location in the contiguous United States

The contiguous United States, also known as the U.S. mainland, officially referred to as the conterminous United States, consists of the 48 adjoining U.S. states and the District of Columbia of the United States in central North America. The te ...

. The park is inhabited by grizzly bear

The grizzly bear (''Ursus arctos horribilis''), also known as the North American brown bear or simply grizzly, is a population or subspecies of the brown bear inhabiting North America.

In addition to the mainland grizzly (''Ursus arctos horr ...

s, cougar

The cougar (''Puma concolor'') (, ''Help:Pronunciation respelling key, KOO-gər''), also called puma, mountain lion, catamount and panther is a large small cat native to the Americas. It inhabits North America, North, Central America, Cent ...

s, wolves

The wolf (''Canis lupus''; : wolves), also known as the grey wolf or gray wolf, is a canine native to Eurasia and North America. More than thirty subspecies of ''Canis lupus'' have been recognized, including the dog and dingo, though gr ...

, and free-ranging herds of bison

A bison (: bison) is a large bovine in the genus ''Bison'' (from Greek, meaning 'wild ox') within the tribe Bovini. Two extant taxon, extant and numerous extinction, extinct species are recognised.

Of the two surviving species, the American ...

and elk. The Yellowstone Park bison herd

The Yellowstone bison herd roams the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. The Plains bison, bison herd is probably the oldest and largest public bison herd in the United States, estimated in 2020 to comprise 4,800 bison. The bison are American bison o ...

is the oldest and largest public bison herd in the United States. Forest fire

A wildfire, forest fire, or a bushfire is an unplanned and uncontrolled fire in an area of combustible vegetation. Depending on the type of vegetation present, a wildfire may be more specifically identified as a bushfire ( in Australia), dese ...

s occur in the park each year; in the large forest fires of 1988, over one-third of the park was burnt. Yellowstone has numerous recreational opportunities, including hiking, camping

Camping is a form of outdoor recreation or outdoor education involving overnight stays with a basic temporary shelter such as a tent. Camping can also include a recreational vehicle, sheltered cabins, a permanent tent, a shelter such as a Bivy bag ...

, boating

Boating is the leisurely activity of travelling by boat, or the recreational use of a boat whether powerboats, sailboats, or man-powered vessels (such as rowing and paddle boats), focused on the travel itself, as well as sports activities, suc ...

, fishing, and sightseeing

Tourism is travel for pleasure, and the commercial activity of providing and supporting such travel. UN Tourism defines tourism more generally, in terms which go "beyond the common perception of tourism as being limited to holiday activity o ...

. Paved roads provide close access to the major geothermal areas as well as some of the lakes and waterfalls. During the winter, visitors often access the park by way of guided tours that use either snow coaches or snowmobile

A snowmobile, also known as a snowmachine (chiefly Alaskan), motor sled (chiefly Canadian), motor sledge, skimobile, snow scooter, or simply a sled is a motorized vehicle designed for winter travel and recreation on snow.

Their engines normally ...

s.

History

The park is roughly bisected by theYellowstone River

The Yellowstone River is a tributary of the Missouri River, approximately long, in the Western United States. Considered the principal tributary of the upper Missouri, via its own tributaries it drains an area with headwaters across the mountain ...

, from which it takes its historical name. Near the end of the 18th century, French trappers named the river ', which is probably a translation of the Hidatsa name ' ("Yellow Stone River").

Later, American trappers rendered the French name in English as "Yellow Stone". Although it is commonly believed that the river was named for the yellow rocks seen in the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone

The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone is the first large canyon on the Yellowstone River downstream from Yellowstone Falls in Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming. The canyon is approximately long, between deep and from wide.

History

Althou ...

, the Native American name source is unclear.

The human history of the park began at least 11,000 years ago when Native Americans began to hunt and fish in the region. During the construction of the post office in Gardiner, Montana

Gardiner is a census-designated place (CDP) in Park County, Montana, United States, along the 45th parallel north, 45th parallel. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population of the community and nearby areas was 833.

Gard ...

, in the 1950s, an obsidian

Obsidian ( ) is a naturally occurring volcanic glass formed when lava extrusive rock, extruded from a volcano cools rapidly with minimal crystal growth. It is an igneous rock. Produced from felsic lava, obsidian is rich in the lighter element ...

point of Clovis origin was found that dated from approximately 11,000 years ago. These Paleo-Indians

Paleo-Indians were the first peoples who entered and subsequently inhabited the Americas towards the end of the Late Pleistocene period. The prefix ''paleo-'' comes from . The term ''Paleo-Indians'' applies specifically to the lithic period in ...

, of the Clovis culture, used the significant amounts of obsidian found in the park to make cutting tools and weapons. Arrowhead

An arrowhead or point is the usually sharpened and hardened tip of an arrow, which contributes a majority of the projectile mass and is responsible for impacting and penetrating a target, or sometimes for special purposes such as signaling.

...

s made of Yellowstone obsidian have been found as far away as the Mississippi Valley

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

, indicating that a regular obsidian trade existed between local tribes and tribes farther east. When the Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery Expedition, was the United States expedition to cross the newly acquired western portion of the country after the Louisiana Purchase. The Corps of Discovery was a select gro ...

entered present-day Montana in 1805 they encountered the Nez Perce

The Nez Perce (; autonym in Nez Perce language: , meaning 'we, the people') are an Indigenous people of the Plateau who still live on a fraction of the lands on the southeastern Columbia River Plateau in the Pacific Northwest. This region h ...

, Crow

A crow is a bird of the genus ''Corvus'', or more broadly, a synonym for all of ''Corvus''. The word "crow" is used as part of the common name of many species. The related term "raven" is not linked scientifically to any certain trait but is rathe ...

, and Shoshone

The Shoshone or Shoshoni ( or ), also known by the endonym Newe, are an Native Americans in the United States, Indigenous people of the United States with four large cultural/linguistic divisions:

* Eastern Shoshone: Wyoming

* Northern Shoshon ...

tribes who described to them the Yellowstone region to the south, but they chose not to investigate.

In 1806, John Colter

John Colter (c.1770–1775 – May 7, 1812 or November 22, 1813) was a member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804–1806). Though party to one of the more famous expeditions in history, Colter is best remembered for explorations he made ...

, a member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, left to join a group of fur trappers. After splitting up with the other trappers in 1807, Colter passed through a portion of what later became the park, during the winter of 1807–1808. He observed at least one geothermal area in the northeastern section of the park, near Tower Fall. After surviving wounds he suffered in a battle with members of the Crow and Blackfoot tribes in 1809, Colter described a place of " fire and brimstone" that most people dismissed as delirium; the supposedly mystical place was nicknamed " Colter's Hell". Over the next 40 years, numerous reports from mountain men and trappers told of boiling mud, steaming rivers, and petrified trees, yet most of these reports were believed at the time to be a myth.

After an 1856 exploration, mountain man Jim Bridger

James Felix Bridger (March 17, 1804 – July 17, 1881) was an American mountain man, Animal trapping, trapper, Army scout, and wilderness guide who explored and trapped in the Western United States in the first half of the 19th century. He was ...

(also believed to be the first or second European American to have seen the Great Salt Lake

The Great Salt Lake is the largest saltwater lake in the Western Hemisphere and the eighth-largest terminal lake in the world. It lies in the northern part of the U.S. state of Utah and has a substantial impact upon the local climate, partic ...

) reported observing boiling springs, spouting water, and a mountain of glass and yellow rock. These reports were largely ignored because Bridger was a known "spinner of yarns". In 1859, a U.S. Army Surveyor named Captain William F. Raynolds embarked on a two-year survey of the southern central Rockies. After wintering in Wyoming, in May 1860, Raynolds and his party—which included geologist Ferdinand V. Hayden and guide Jim Bridger—attempted to cross the Continental Divide over Two Ocean Plateau from the Wind River drainage in northwest Wyoming. Heavy spring snows prevented their passage but had they been able to traverse the divide, the party would have been the first organized survey to enter the Yellowstone region. The American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

hampered further organized explorations until the late 1860s.

Jay Cooke

Jay Cooke (August 10, 1821 – February 16, 1905) was an American financier who helped finance the Union war effort during the American Civil War and the postwar development of railroads in the northwestern United States. He is generally acknowle ...

, a businessman who wanted to bring tourists to the region, encouraged him to mention it in his official report of the survey. Cooke wrote that his friend, Congressman William D. Kelley had also suggested "Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

pass a bill reserving the Great Geyser Basin as a public park forever".

Park creation

In 1871, eleven years after his failed first effort, Ferdinand V. Hayden was finally able to explore the region. With government sponsorship, he returned to the region with a second, larger expedition, the Hayden Geological Survey of 1871. He compiled a comprehensive report, including large-format photographs by William Henry Jackson and paintings by Thomas Moran. The report helped to convince the U.S. Congress to withdraw this region from

In 1871, eleven years after his failed first effort, Ferdinand V. Hayden was finally able to explore the region. With government sponsorship, he returned to the region with a second, larger expedition, the Hayden Geological Survey of 1871. He compiled a comprehensive report, including large-format photographs by William Henry Jackson and paintings by Thomas Moran. The report helped to convince the U.S. Congress to withdraw this region from public auction

A government auction or a public auction is an auction held on behalf of a government in which the property to be auctioned is either property owned by the government or property which is sold under the authority of a court of law or a governmen ...

. On March 1, 1872, President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

signed ''The Act of Dedication'' law that created Yellowstone National Park.

Hayden, while not the only person to have thought of creating a park in the region, was its first and most enthusiastic advocate. He believed in "setting aside the area as a pleasure ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people" and warned that there were those who would come and "make merchandise of these beautiful specimens". Worrying the area could face the same fate as Niagara Falls

Niagara Falls is a group of three waterfalls at the southern end of Niagara Gorge, spanning the Canada–United States border, border between the Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Ontario in Canada and the state of New York (s ...

, he concluded the site should "be as free as the air or Water". In his report to the Committee on Public Lands, he concluded that if the bill failed to become law, "the vandals who are now waiting to enter into this wonder-land, will in a single season despoil, beyond recovery, these remarkable curiosities, which have required all the cunning skill of nature thousands of years to prepare".

Hayden and his 1871 party recognized Yellowstone as a unique place that should be available for further research. He also was encouraged to preserve it for others to see and experience it as well. In 1873, Congress authorized and funded a survey to find a wagon route to the park from the south which was completed by the Jones Expedition of 1873. Eventually the railroads and, sometime after that, the automobile would make that possible. The park was not set aside strictly for ecological purposes. Hayden imagined something akin to the scenic resorts and baths in England, Germany, and Switzerland.

poachers

Poaching is the illegal hunting or capturing of wild animals, usually associated with land use rights.

Poaching was once performed by impoverished peasants for subsistence purposes and to supplement meager diets. It was set against the hunti ...

, vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic people who were first reported in the written records as inhabitants of what is now Poland, during the period of the Roman Empire. Much later, in the fifth century, a group of Vandals led by kings established Vand ...

, and others seeking to raid its resources. He addressed the practical problems park administrators faced in the 1872 Report to the Secretary of the Interior and correctly predicted that Yellowstone would become a major international attraction deserving the continuing stewardship of the government. In 1874, both Langford and Delano advocated the creation of a federal agency to protect the vast park, but Congress refused. In 1875, Colonel William Ludlow, who had previously explored areas of Montana under the command of George Armstrong Custer

George Armstrong Custer (December 5, 1839 – June 25, 1876) was a United States Army officer and cavalry commander in the American Civil War and the American Indian Wars.

Custer graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point ...

, was assigned to organize and lead an expedition to Montana and the newly established Yellowstone Park. Observations about the lawlessness and exploitation of park resources were included in Ludlow's ''Report of a Reconnaissance to the Yellowstone National Park''. The report included letters and attachments by other expedition members, including naturalist and mineralogist George Bird Grinnell.

Grinnell documented the poaching of buffalo, deer

A deer (: deer) or true deer is a hoofed ruminant ungulate of the family Cervidae (informally the deer family). Cervidae is divided into subfamilies Cervinae (which includes, among others, muntjac, elk (wapiti), red deer, and fallow deer) ...

, elk, and antelope

The term antelope refers to numerous extant or recently extinct species of the ruminant artiodactyl family Bovidae that are indigenous to most of Africa, India, the Middle East, Central Asia, and a small area of Eastern Europe. Antelopes do ...

for hides: "It is estimated that during the winter of 1874–1875, not less than 3,000 buffalo and mule deer suffer even more severely than the elk, and the antelope nearly as much."

As a result, Langford was forced to step down in 1877.

Having traveled through Yellowstone and witnessed land management problems, Philetus Norris volunteered for the position following Langford's exit. Congress finally saw fit to implement a salary for the position, as well as to provide minimal funding to operate the park. Norris used these funds to expand access to the park, building numerous crude roads and facilities.

In 1880, Harry Yount was appointed as a gamekeeper to control poaching and vandalism in the park. Yount had previously spent decades exploring the mountain country of present-day Wyoming, including the Grand Tetons, after joining F V. Hayden's Geological Survey in 1873. Yount is the first national park ranger, and Yount's Peak, at the head of the Yellowstone River, was named in his honor. These measures still proved to be insufficient in protecting the park, as neither Norris nor the three superintendents who followed, were given sufficient manpower or resources.

During the 1870s and 1880s, Native American tribes were effectively excluded from the national park. Under a half-dozen tribes had made seasonal use of the Yellowstone area- the only year-round residents were small bands of Eastern Shoshone known as " Sheepeaters". They left the area under the assurances of a treaty negotiated in 1868, under which the Sheepeaters ceded their lands but retained the right to hunt in Yellowstone. The United States never ratified the treaty and refused to recognize the claims of the Sheepeaters or any other tribe that had used Yellowstone.

The Nez Perce band associated with Chief Joseph, numbering about 750 people, passed through Yellowstone National Park in thirteen days in late August 1877. They were being pursued by the U.S. Army and entered the national park about two weeks after the Battle of the Big Hole. Some of the Nez Perce were friendly to the tourists and other people they encountered in the park; some were not. Nine park visitors were briefly taken captive. Despite Joseph and other chiefs ordering that no one should be harmed, at least two people were killed and several wounded. One of the areas where encounters occurred was in Lower Geyser Basin and east along a branch of the Firehole River to Mary Mountain and beyond. That stream was named Nez Perce Creek in memory of their trail through the area. A group of Bannocks entered the park in 1878, alarming park Superintendent Philetus Norris. In the aftermath of the Sheepeater Indian War of 1879, Norris built a fort to prevent Native Americans from entering the national park.

The Northern Pacific Railroad built a train station in

The Northern Pacific Railroad built a train station in Livingston, Montana

Livingston is a city and the county seat of Park County, Montana, United States. It is in southwestern Montana, on the Yellowstone River, north of Yellowstone National Park. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 8,040.

Hist ...

, as a gateway terminus to connect to the northern entrance area in 1883, which helped to increase visitation from 300 in 1872 to 5,000 in 1883. The spur line was completed in fall of that year from Livingston to Cinnabar

Cinnabar (; ), or cinnabarite (), also known as ''mercurblende'' is the bright scarlet to brick-red form of Mercury sulfide, mercury(II) sulfide (HgS). It is the most common source ore for refining mercury (element), elemental mercury and is t ...

for stage connection to Mammoth

A mammoth is any species of the extinct elephantid genus ''Mammuthus.'' They lived from the late Miocene epoch (from around 6.2 million years ago) into the Holocene until about 4,000 years ago, with mammoth species at various times inhabi ...

, then in 1902 extended to Gardiner station, where passengers also switched to stagecoach

A stagecoach (also: stage coach, stage, road coach, ) is a four-wheeled public transport coach used to carry paying passengers and light packages on journeys long enough to need a change of horses. It is strongly sprung and generally drawn by ...

. Visitors in these early years faced poor and dusty roads plus limited services, with automobiles first admitted in phases beginning only in 1915. By 1901 a Chicago, Burlington & Quincy connection opened via Cody and in 1908 a Union Pacific Railroad

The Union Pacific Railroad is a Railroad classes, Class I freight-hauling railroad that operates 8,300 locomotives over routes in 23 U.S. states west of Chicago and New Orleans. Union Pacific is the second largest railroad in the United Stat ...

connection to West Yellowstone, followed by a 1927 Milwaukee Road

The Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad (CMStP&P), better known as the Milwaukee Road , was a Class I railroad that operated in the Midwestern United States, Midwest and Pacific Northwest, Northwest of the United States from 1847 ...

connection to Gallatin Gateway near Bozeman, also motorcoaching visitors via West Yellowstone. Rail visitation fell off considerably by World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

and ceased regular service in favor of the automobile around the 1960s, though special excursions occasionally continued into the early 1980s.

Ongoing poaching and destruction of natural resources continued unabated until the U.S. Army arrived at Mammoth Hot Springs in 1886 and built Camp Sheridan. Over the next 22 years, as the army constructed permanent structures, Camp Sheridan was renamed Fort Yellowstone. On May 7, 1894, the Boone and Crockett Club, acting through the personality of George G. Vest, Arnold Hague, William Hallett Phillips, W. A. Wadsworth, Archibald Rogers, Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

, and George Bird Grinnell were successful in carrying through the Park Protection Act, which saved the park. The Lacey Act of 1900

The Lacey Act of 1900 is a Conservation movement, conservation law in the United States that, as amended, now prohibits trade in wildlife, fish, and plants that have been illegally taken, possessed, transported, or sold.United States. Lacey Act ...

provided legal support for the officials prosecuting poachers. With the funding and manpower necessary to keep a diligent watch, the army developed its own policies and regulations that permitted public access while protecting park wildlife and natural resources. When the National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an List of federal agencies in the United States, agency of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government, within the US Department of the Interior. The service manages all List ...

was created in 1916, many of the management principles developed by the army were adopted by the new agency. The army turned control over to the National Park Service on October 31, 1918.

In 1898, the naturalist John Muir

John Muir ( ; April 21, 1838December 24, 1914), also known as "John of the Mountains" and "Father of the national park, National Parks", was a Scottish-born American naturalist, author, environmental philosopher, botanist, zoologist, glaciologi ...

described the park as follows:

Automobiles and further development

By 1915, 1,000 automobiles per year were entering the park, resulting in conflicts with horses and horse-drawn transportation. Horse travel on roads was eventually prohibited.

The

By 1915, 1,000 automobiles per year were entering the park, resulting in conflicts with horses and horse-drawn transportation. Horse travel on roads was eventually prohibited.

The Civilian Conservation Corps

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was a voluntary government unemployment, work relief program that ran from 1933 to 1942 in the United States for unemployed, unmarried men ages 18–25 and eventually expanded to ages 17–28. The CCC was ...

(CCC), a New Deal

The New Deal was a series of wide-reaching economic, social, and political reforms enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1938, in response to the Great Depression in the United States, Great Depressi ...

relief agency for young men, played a major role between 1933 and 1942 in developing Yellowstone facilities. CCC projects included reforestation, campground development of many of the park's trails and campgrounds, trail construction, fire hazard reduction, and fire-fighting work. The CCC built the majority of the early visitor centers, campgrounds, and the current system of park roads.

During World War II, tourist travel fell sharply, staffing was cut, and many facilities fell into disrepair. By the 1950s, visitation increased tremendously in Yellowstone and other national parks. To accommodate the increased visitation, park officials implemented Mission 66, an effort to modernize and expand park service facilities. Planned to be completed by 1966, in honor of the 50th anniversary of the founding of the National Park Service, Mission 66 construction diverged from the traditional log cabin style with design features of a modern style. During the late 1980s, most construction styles in Yellowstone reverted to the more traditional designs. After the enormous forest fires of 1988 damaged much of Grant Village, structures there were rebuilt in the traditional style. The visitor center at Canyon Village, which opened in 2006, incorporates a more traditional design as well.

The 1959 Hebgen Lake earthquake just west of Yellowstone at Hebgen Lake damaged roads and some structures in the park. In the northwest section of the park, new geysers were found, and many existing hot springs became turbid. It was the most powerful earthquake to hit the region in recorded history.

In 1963, after several years of public controversy regarding the forced reduction of the elk population in Yellowstone, the United States Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall appointed an advisory board to collect scientific data to inform future wildlife management of the national parks. In a paper known as the Leopold Report, the committee observed that culling programs at other national parks had been ineffective, and recommended the management of Yellowstone's elk population.

The

The 1959 Hebgen Lake earthquake just west of Yellowstone at Hebgen Lake damaged roads and some structures in the park. In the northwest section of the park, new geysers were found, and many existing hot springs became turbid. It was the most powerful earthquake to hit the region in recorded history.

In 1963, after several years of public controversy regarding the forced reduction of the elk population in Yellowstone, the United States Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall appointed an advisory board to collect scientific data to inform future wildlife management of the national parks. In a paper known as the Leopold Report, the committee observed that culling programs at other national parks had been ineffective, and recommended the management of Yellowstone's elk population.

The wildfire

A wildfire, forest fire, or a bushfire is an unplanned and uncontrolled fire in an area of Combustibility and flammability, combustible vegetation. Depending on the type of vegetation present, a wildfire may be more specifically identified as a ...

s during the summer of 1988 were the largest in the history of the park. Approximately or 36% of the parkland was impacted by the fires, leading to a systematic re-evaluation of fire management policies. The fire season of 1988 was considered normal until a combination of drought and heat by mid-July contributed to an extreme fire danger. On " Black Saturday", August 20, 1988, strong winds expanded the fires rapidly, and more than burned.

On October 1, 2013, Yellowstone National Park closed due to the 2013 United States federal government shutdown.

Research and recognition

The expansive cultural history of the park has been documented by the 1,000 archeological sites that have been discovered. The park has 1,106 historic structures and features, and of these Obsidian Cliff and five buildings have been designated

The expansive cultural history of the park has been documented by the 1,000 archeological sites that have been discovered. The park has 1,106 historic structures and features, and of these Obsidian Cliff and five buildings have been designated National Historic Landmarks

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a National Register of Historic Places property types, building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the Federal government of the United States, United States government f ...

. Yellowstone was designated an International Biosphere Reserve

Man and the Biosphere Programme (MAB) is an intergovernmental scientific program, launched in 1971 by UNESCO, that aims to establish a scientific basis for the 'improvement of relationships' between people and their environments.

MAB engages w ...

on October 26, 1976, and a UN World Heritage Site

World Heritage Sites are landmarks and areas with legal protection under an treaty, international treaty administered by UNESCO for having cultural, historical, or scientific significance. The sites are judged to contain "cultural and natural ...

on September 8, 1978. The park was placed on the List of World Heritage in Danger

The List of World Heritage in Danger is compiled by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) through the World Heritage Committee according to Article 11.4 of the World Heritage Convention,Full title: ''Conv ...

from 1995 to 2003 due to the effects of tourism, infection of wildlife, and issues with invasive species

An invasive species is an introduced species that harms its new environment. Invasive species adversely affect habitats and bioregions, causing ecological, environmental, and/or economic damage. The term can also be used for native spec ...

. In 2010, Yellowstone National Park was honored with its own quarter under the America the Beautiful Quarters Program.

Justin Farrell explores three moral sensibilities that motivated activists in dealing with Yellowstone. First came the utilitarian vision of maximum exploitation of natural resources

The exploitation of natural resources describes using natural resources, often non-renewable or limited, for economic growth or development. Environmental degradation, human insecurity, and social conflict frequently accompany natural resource ex ...

, a characteristic of developers in the late 19th century. Second was the spiritual vision of nature inspired by Romanticism and the transcendentalists in the mid-19th century. The twentieth century saw the biocentric moral vision that focuses on the health of the ecosystem as theorized by Aldo Leopold

Aldo Leopold (January 11, 1887 – April 21, 1948) was an American writer, Philosophy, philosopher, Natural history, naturalist, scientist, Ecology, ecologist, forester, Conservation biology, conservationist, and environmentalist. He was a profes ...

, which led to the expansion of federally protected areas and the surrounding ecosystems.

The Heritage and Research Center is located at Gardiner, Montana, near the north entrance to the park. The center is home to the Yellowstone National Park's museum collection, archives, research library, historian, archeology lab, and herbarium

A herbarium (plural: herbaria) is a collection of preserved plant biological specimen, specimens and associated data used for scientific study.

The specimens may be whole plants or plant parts; these will usually be in dried form mounted on a sh ...

. The Yellowstone National Park Archives maintain collections of historical records of Yellowstone and the National Park Service. The collection includes the administrative records of Yellowstone, as well as resource management records, records from major projects, and donated manuscripts and personal papers. The archives are affiliated with the National Archives and Records Administration

The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) is an independent agency of the United States government within the executive branch, charged with the preservation and documentation of government and historical records. It is also task ...

.

Geography

Yellowstone National Park occupies a roughly square parcel of volcanic complex that jogs slightly beyond the northwestern corner of Wyoming. Approximately 96 percent of the total land area of Yellowstone National Park is located within the state of Wyoming. Another three percent is within Montana, with the remaining one percent in Idaho. Montana's portion of Yellowstone contains multiple trails, facilities and swimming holes, while the Idaho portion of the park is completely undeveloped. The irregular eastern boundary of the national park follows the height of land along the Absaroka Range.

The park is north to south, and west to east by air. Yellowstone is in area, larger than either of the states of

Yellowstone National Park occupies a roughly square parcel of volcanic complex that jogs slightly beyond the northwestern corner of Wyoming. Approximately 96 percent of the total land area of Yellowstone National Park is located within the state of Wyoming. Another three percent is within Montana, with the remaining one percent in Idaho. Montana's portion of Yellowstone contains multiple trails, facilities and swimming holes, while the Idaho portion of the park is completely undeveloped. The irregular eastern boundary of the national park follows the height of land along the Absaroka Range.

The park is north to south, and west to east by air. Yellowstone is in area, larger than either of the states of Rhode Island

Rhode Island ( ) is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Connecticut to its west; Massachusetts to its north and east; and the Atlantic Ocean to its south via Rhode Island Sound and Block Is ...

or Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic and South Atlantic states, South Atlantic regions of the United States. It borders Maryland to its south and west, Pennsylvania to its north, New Jersey ...

. Rivers and lakes cover five percent of the land area, with the largest water body being Yellowstone Lake at . Yellowstone Lake is up to deep and has of shoreline. At an elevation of above sea level, Yellowstone Lake is the largest high-elevation lake in North America. Forests comprise 80 percent of the land area of the park; most of the rest is grassland

A grassland is an area where the vegetation is dominance (ecology), dominated by grasses (Poaceae). However, sedge (Cyperaceae) and rush (Juncaceae) can also be found along with variable proportions of legumes such as clover, and other Herbaceo ...

.

The Continental Divide of North America runs diagonally through the southwestern part of the park. The divide is a topographic feature that separates the Pacific Ocean and Atlantic Ocean water drainages. About one-third of the park lies on the west side of the divide. The origins of the Yellowstone and Snake River

The Snake River is a major river in the interior Pacific Northwest region of the United States. About long, it is the largest tributary of the Columbia River, which is the largest North American river that empties into the Pacific Ocean. Begin ...

s are near each other but on opposite sides of the divide. As a result, the waters of the Snake River flow to the Pacific Ocean, while those of the Yellowstone find their way to the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico () is an oceanic basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, mostly surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north, and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States; on the southw ...

.

The park sits on the Yellowstone Plateau, at an average elevation of above sea level. The plateau is bounded on nearly all sides by mountain range

A mountain range or hill range is a series of mountains or hills arranged in a line and connected by high ground. A mountain system or mountain belt is a group of mountain ranges with similarity in form, structure, and alignment that have aris ...

s of the Middle Rocky Mountains, which range from in elevation. The highest point in the park is atop Eagle Peak () and the lowest is along Reese Creek (). Nearby mountain ranges include the Gallatin Range to the northwest, the Beartooth Mountains in the north, the Absaroka Range to the east, the Teton Range

The Teton Range is a mountain range of the Rocky Mountains in North America. It extends for approximately in a north–south direction through the U.S. state of Wyoming, east of the Idaho state line. It is south of Yellowstone National Park, ...

to the south, and the Madison Range to the west. The most prominent summit on the Yellowstone Plateau is Mount Washburn at .

Yellowstone National Park has one of the world's largest petrified forests, trees which were long ago buried by ash and soil, and were gradually replaced by mineral materials. This ash and other volcanic debris are believed to have come from the park area itself as the central part of Yellowstone is the massive caldera of a supervolcano. The park contains 290 waterfall

A waterfall is any point in a river or stream where water flows over a vertical drop or a series of steep drops. Waterfalls also occur where meltwater drops over the edge

of a tabular iceberg or ice shelf.

Waterfalls can be formed in seve ...

s of at least , the highest being the Lower Falls of the Yellowstone River at .

Three deep canyons are located in the park, cut through the volcanic tuff of the Yellowstone Plateau by rivers over the last 640,000 years. The Lewis River flows through Lewis Canyon in the south, and the Yellowstone River has carved two colorful canyons, the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone and the Black Canyon of the Yellowstone in its journey north.

Geology

Volcanism

Yellowstone is at the northeastern end of the Snake River Plain, a great bow-shaped arc through the mountains that extends roughly from the park to the Idaho-Oregon border.

The volcanism of Yellowstone is believed to be linked to the somewhat older volcanism of the Snake River Plain. Yellowstone is thus the active part of a hotspot that the North American Plate has moved over in a southwest direction over time. The origin of this hotspot volcanism is disputed. One theory holds that a

Yellowstone is at the northeastern end of the Snake River Plain, a great bow-shaped arc through the mountains that extends roughly from the park to the Idaho-Oregon border.

The volcanism of Yellowstone is believed to be linked to the somewhat older volcanism of the Snake River Plain. Yellowstone is thus the active part of a hotspot that the North American Plate has moved over in a southwest direction over time. The origin of this hotspot volcanism is disputed. One theory holds that a mantle plume

A mantle plume is a proposed mechanism of convection within the Earth's mantle, hypothesized to explain anomalous volcanism. Because the plume head partially melts on reaching shallow depths, a plume is often invoked as the cause of volcanic ho ...

has caused the Yellowstone hotspot to migrate, while another theory explains migrating hotspot volcanism as the result of the fragmentation and dynamics of the subducted Farallon Plate in Earth's interior.

The Yellowstone Caldera is the largest volcanic system in North America, and worldwide it is only rivaled by the Lake Toba Caldera on Sumatra

Sumatra () is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the list of islands by area, sixth-largest island in the world at 482,286.55 km2 (182,812 mi. ...

. It has been termed a " supervolcano" because the caldera was formed by exceptionally large explosive eruptions. The magma chamber

A magma chamber is a large pool of liquid rock beneath the surface of the Earth. The molten rock, or magma, in such a chamber is less dense than the surrounding country rock, which produces buoyant forces on the magma that tend to drive it u ...

that lies under Yellowstone is estimated to be a single connected chamber, about long, wide, and deep. The current caldera

A caldera ( ) is a large cauldron-like hollow that forms shortly after the emptying of a magma chamber in a volcanic eruption. An eruption that ejects large volumes of magma over a short period of time can cause significant detriment to the str ...

was created by a cataclysmic eruption that occurred 640,000 years ago, which released more than of ash, rock and pyroclast

Tephra is fragmental material produced by a Volcano, volcanic eruption regardless of composition, fragment size, or emplacement mechanism.

Volcanologists also refer to airborne fragments as pyroclasts. Once clasts have fallen to the ground, ...

ic materials./ This eruption was more than 1,000 times larger than the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens

In March 1980, a series of volcanic explosions and pyroclastic flows began at Mount St. Helens in Skamania County, Washington, United States. A series of Phreatic eruption, phreatic blasts occurred from the summit and escalated until a major ...

. It produced a caldera nearly deep and in area and deposited the Lava Creek Tuff, a welded tuff geologic formation. The most violent known eruption, which occurred 2.1 million years ago, ejected of volcanic material and created the rock formation known as the Huckleberry Ridge Tuff and the Island Park Caldera. A smaller eruption ejected of material 1.3 million years ago, forming the Henry's Fork Caldera and depositing the Mesa Falls Tuff.

Each of the three climactic eruptions released vast amounts of ash that blanketed much of central North America, falling many hundreds of miles away. The amount of ash and gases released into the atmosphere probably caused significant impacts on world weather patterns and led to the extinction

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

of some species, primarily in North America.

A subsequent caldera-forming eruption occurred about 160,000 years ago. It formed the relatively small caldera that contains the West Thumb of Yellowstone Lake. Since the last supereruption, a series of smaller eruptive cycles between 640,000 and 70,000 years ago, has nearly filled in the Yellowstone Caldera with 80 different eruptions of rhyolitic lavas such as those that can be seen at Obsidian Cliffs and basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanite, aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the planetary surface, surface of a terrestrial ...

ic lavas which can be viewed at Sheepeater Cliff. Lava strata are most easily seen at the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, where the Yellowstone River continues to carve into the ancient lava flows. The canyon is a classic V-shaped valley, indicative of river-type erosion rather than erosion caused by glaciation

A glacial period (alternatively glacial or glaciation) is an interval of time (thousands of years) within an ice age that is marked by colder temperatures and glacier advances. Interglacials, on the other hand, are periods of warmer climate be ...

.

Each eruption is part of an eruptive cycle that climaxes with the partial collapse of the roof of the volcano's partially emptied magma chamber. This creates a collapsed depression, called a caldera, and releases vast amounts of volcanic material, usually through fissures that ring the caldera. The time between the last three cataclysmic eruptions in the Yellowstone area has ranged from 600,000 to 800,000 years; however, the small number of such climactic eruptions cannot be used to make an accurate prediction for future volcanic events.

Geysers and the hydrothermal system

The most famousgeyser

A geyser (, ) is a spring with an intermittent water discharge ejected turbulently and accompanied by steam. The formation of geysers is fairly rare and is caused by particular hydrogeological conditions that exist only in a few places on Ea ...

in the park, and perhaps the world, is Old Faithful

Old Faithful is a cone geyser in Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming, United States. It was named in 1870 during the Washburn–Langford–Doane Expedition and was the first geyser in the park to be named. It is a highly predictable geotherma ...

geyser, located in Upper Geyser Basin. Castle Geyser, Lion Geyser, Beehive Geyser, Grand Geyser (the world's tallest predictable geyser), Giant Geyser (the world's most voluminous geyser), Riverside Geyser and numerous other geysers are in the same basin. The park contains the tallest active geyser in the world— Steamboat Geyser in the Norris Geyser Basin. A study that was completed in 2011 found that at least 1,283 geysers have erupted in Yellowstone. Of these, an average of 465 are active in a given year. Yellowstone contains at least 10,000 geothermal features altogether, including geyser