XYZ Affair on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The XYZ Affair was a political and diplomatic episode in 1797 and 1798, early in the presidency of John Adams, involving a confrontation between the

In late May 1797 Adams met with his cabinet to discuss the situation and to choose a special commission to France. Adams initially proposed that

In late May 1797 Adams met with his cabinet to discuss the situation and to choose a special commission to France. Adams initially proposed that  The American commission arrived in Paris in early October, and immediately requested a meeting with Talleyrand. After an initial brief meeting (in which Talleyrand only provisionally accepted the commissioners' credentials), a longer meeting was held a week later. Talleyrand sought from the commissioners an explanation for the speech Adams had made in May, which had angered Directory members; his motivation was to determine how favorably the commissioners were disposed to the negotiations. If they responded in an unfavorable manner, the Directory would refuse to accept their credentials. The commissioners first learned of Talleyrand's expected demand on October 14 through an indirect channel. They decided that no explanation would be given for Adams' speech.

The American commission arrived in Paris in early October, and immediately requested a meeting with Talleyrand. After an initial brief meeting (in which Talleyrand only provisionally accepted the commissioners' credentials), a longer meeting was held a week later. Talleyrand sought from the commissioners an explanation for the speech Adams had made in May, which had angered Directory members; his motivation was to determine how favorably the commissioners were disposed to the negotiations. If they responded in an unfavorable manner, the Directory would refuse to accept their credentials. The commissioners first learned of Talleyrand's expected demand on October 14 through an indirect channel. They decided that no explanation would be given for Adams' speech.

Not long after this standoff, Talleyrand sent Lucien Hauteval ("Z") to meet with Elbridge Gerry. The two men knew each other, having met in Boston in 1792. Hauteval assured Gerry of Talleyrand's sincerity in seeking peace, and encouraged him to keep the informal negotiations open. He reiterated the demands for a loan and bribe.

A week later (notably after the signing of the

Not long after this standoff, Talleyrand sent Lucien Hauteval ("Z") to meet with Elbridge Gerry. The two men knew each other, having met in Boston in 1792. Hauteval assured Gerry of Talleyrand's sincerity in seeking peace, and encouraged him to keep the informal negotiations open. He reiterated the demands for a loan and bribe.

A week later (notably after the signing of the

In late November, Talleyrand began maneuvering to separate Gerry from the other commissioners. He extended a "social" dinner invitation to Gerry, which the latter, seeking to maintain communications, planned to attend. The matter heightened distrust of Gerry by Marshall and Pinckney, who sought guarantees that Gerry would limit any representations and agreements he might consider. Despite seeking to refuse informal negotiations, all of the commissioners ended up having private meetings with some of Talleyrand's negotiators.

The commissioners eventually divided over the issue of whether to continue informal negotiations, with the Federalists Marshall and Pinckney opposed, and Gerry in favor. This division was eventually clear to Talleyrand, who told Gerry in January 1798 that he would no longer deal with Pinckney. In February, Talleyrand gained approval from the Directory for a new bargaining position, and he maneuvered to exclude Marshall from the negotiations as well. The change in strategy alarmed a number of American residents of Paris, who reported the growing possibility of war. Around this time Gerry, at Talleyrand's insistence, began keeping secret from the other commissioners the substance of their meetings.

All three commissioners met with Talleyrand informally in March, but it was clear that the parties were at an impasse. This appeared to be the case despite Talleyrand's agreement to drop the demand for a loan. Both sides prepared statements to be sent across the Atlantic stating their positions, and Marshall and Pinckney, frozen out of talks that Talleyrand would only conduct with Gerry, left France in April. Their departure was delayed due to a series of negotiations over the return of their passports; in order to obtain diplomatic advantage, Talleyrand sought to force Marshall and Pinckney to formally request their return (which would allow him to later claim that they broke off negotiations). Talleyrand eventually gave in, formally requesting their departure. Gerry, although he sought to maintain unity with his co-commissioners, was told by Talleyrand that if he left France the Directory would declare war. Gerry remained behind, protesting the "impropriety of permitting a foreign government to hoosethe person who should negotiate." He however remained optimistic that war was unrealistic, writing to William Vans Murray, the American minister to The Netherlands, that "nothing but madness" would cause the French to declare war.

Gerry resolutely refused to engage in further substantive negotiations with Talleyrand, agreeing only to stay until someone with more authority could replace him, and wrote to President Adams requesting assistance in securing his departure from Paris. Talleyrand eventually sent representatives to The Hague to reopen negotiations with William Vans Murray, and Gerry finally returned home in October 1798.

In late November, Talleyrand began maneuvering to separate Gerry from the other commissioners. He extended a "social" dinner invitation to Gerry, which the latter, seeking to maintain communications, planned to attend. The matter heightened distrust of Gerry by Marshall and Pinckney, who sought guarantees that Gerry would limit any representations and agreements he might consider. Despite seeking to refuse informal negotiations, all of the commissioners ended up having private meetings with some of Talleyrand's negotiators.

The commissioners eventually divided over the issue of whether to continue informal negotiations, with the Federalists Marshall and Pinckney opposed, and Gerry in favor. This division was eventually clear to Talleyrand, who told Gerry in January 1798 that he would no longer deal with Pinckney. In February, Talleyrand gained approval from the Directory for a new bargaining position, and he maneuvered to exclude Marshall from the negotiations as well. The change in strategy alarmed a number of American residents of Paris, who reported the growing possibility of war. Around this time Gerry, at Talleyrand's insistence, began keeping secret from the other commissioners the substance of their meetings.

All three commissioners met with Talleyrand informally in March, but it was clear that the parties were at an impasse. This appeared to be the case despite Talleyrand's agreement to drop the demand for a loan. Both sides prepared statements to be sent across the Atlantic stating their positions, and Marshall and Pinckney, frozen out of talks that Talleyrand would only conduct with Gerry, left France in April. Their departure was delayed due to a series of negotiations over the return of their passports; in order to obtain diplomatic advantage, Talleyrand sought to force Marshall and Pinckney to formally request their return (which would allow him to later claim that they broke off negotiations). Talleyrand eventually gave in, formally requesting their departure. Gerry, although he sought to maintain unity with his co-commissioners, was told by Talleyrand that if he left France the Directory would declare war. Gerry remained behind, protesting the "impropriety of permitting a foreign government to hoosethe person who should negotiate." He however remained optimistic that war was unrealistic, writing to William Vans Murray, the American minister to The Netherlands, that "nothing but madness" would cause the French to declare war.

Gerry resolutely refused to engage in further substantive negotiations with Talleyrand, agreeing only to stay until someone with more authority could replace him, and wrote to President Adams requesting assistance in securing his departure from Paris. Talleyrand eventually sent representatives to The Hague to reopen negotiations with William Vans Murray, and Gerry finally returned home in October 1798.

While the American diplomats were in Europe, President Adams considered his options in the event of the commission's failure. His cabinet urged that the nation's military be strengthened, including the raising of a 20,000-man army and the acquisition or construction of

While the American diplomats were in Europe, President Adams considered his options in the event of the commission's failure. His cabinet urged that the nation's military be strengthened, including the raising of a 20,000-man army and the acquisition or construction of

Transcript of Adams speech on the release of the XYZ papers

"The XYZ Affair and the Quasi-War with France, 1798–1800"

U.S. Department of State, Office of the Historian {{DEFAULTSORT:Xyz Affair 1797 in France 1798 in France 1797 in international relations 1798 in international relations 1797 in the United States 1798 in the United States 18th-century controversies in the United States History of the foreign relations of the United States History of the foreign relations of France Diplomatic crises of the 18th century Political controversies in the United States Quasi-War Presidency of John Adams France–United States relations 5th United States Congress Political controversies in France Elbridge Gerry

United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

and Republican France that led to the Quasi-War

The Quasi-War was an undeclared war from 1798 to 1800 between the United States and the French First Republic. It was fought almost entirely at sea, primarily in the Caribbean and off the East Coast of the United States, with minor actions in ...

. The name derives from the substitution of the letters X, Y, and Z for the names of French diplomats Jean-Conrad Hottinguer

Baron Jean-Conrad Hottinguer (15 February 1764, Zurich – 12 September 1841, Castle Piple, Boissy-Saint-Léger) was a Switzerland, Swiss-born French banker who later became a Baron#France, Baron of the French Empire.

Biography

Career

In 1784, ...

(X), Pierre Bellamy (Y), and Lucien Hauteval (Z) in documents released by the Adams administration.

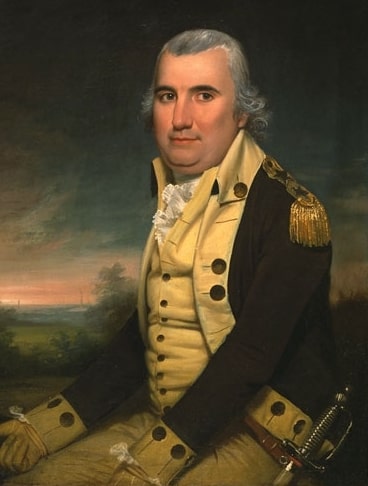

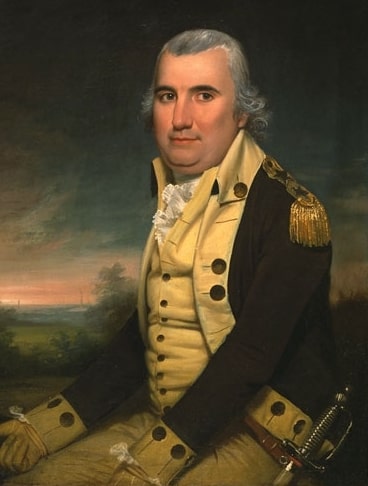

An American diplomatic commission was sent to France in July 1797 to negotiate a solution to problems that were threatening to break out into war. The diplomats, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, John Marshall

John Marshall (September 24, 1755July 6, 1835) was an American statesman, jurist, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fourth chief justice of the United States from 1801 until his death in 1835. He remai ...

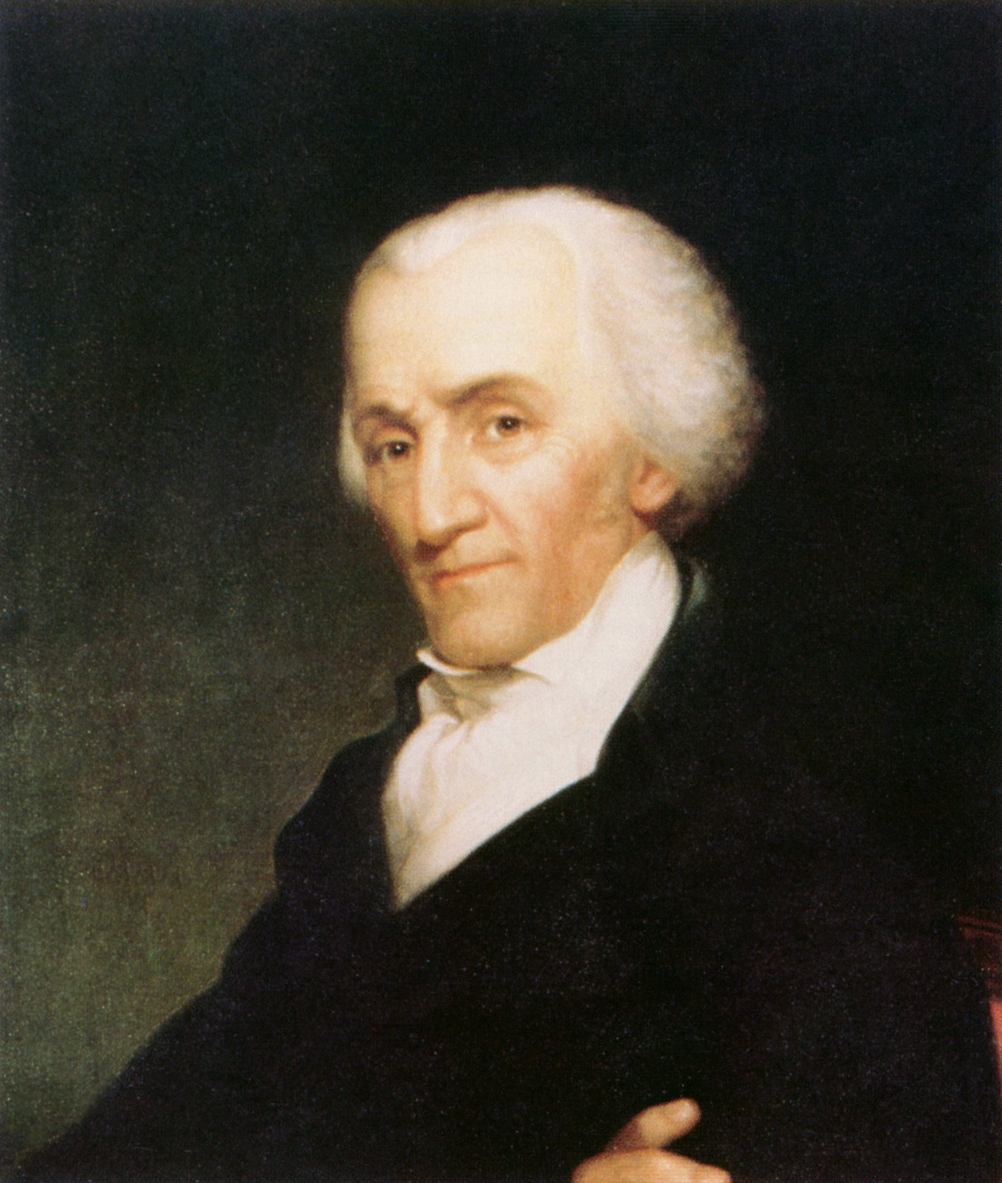

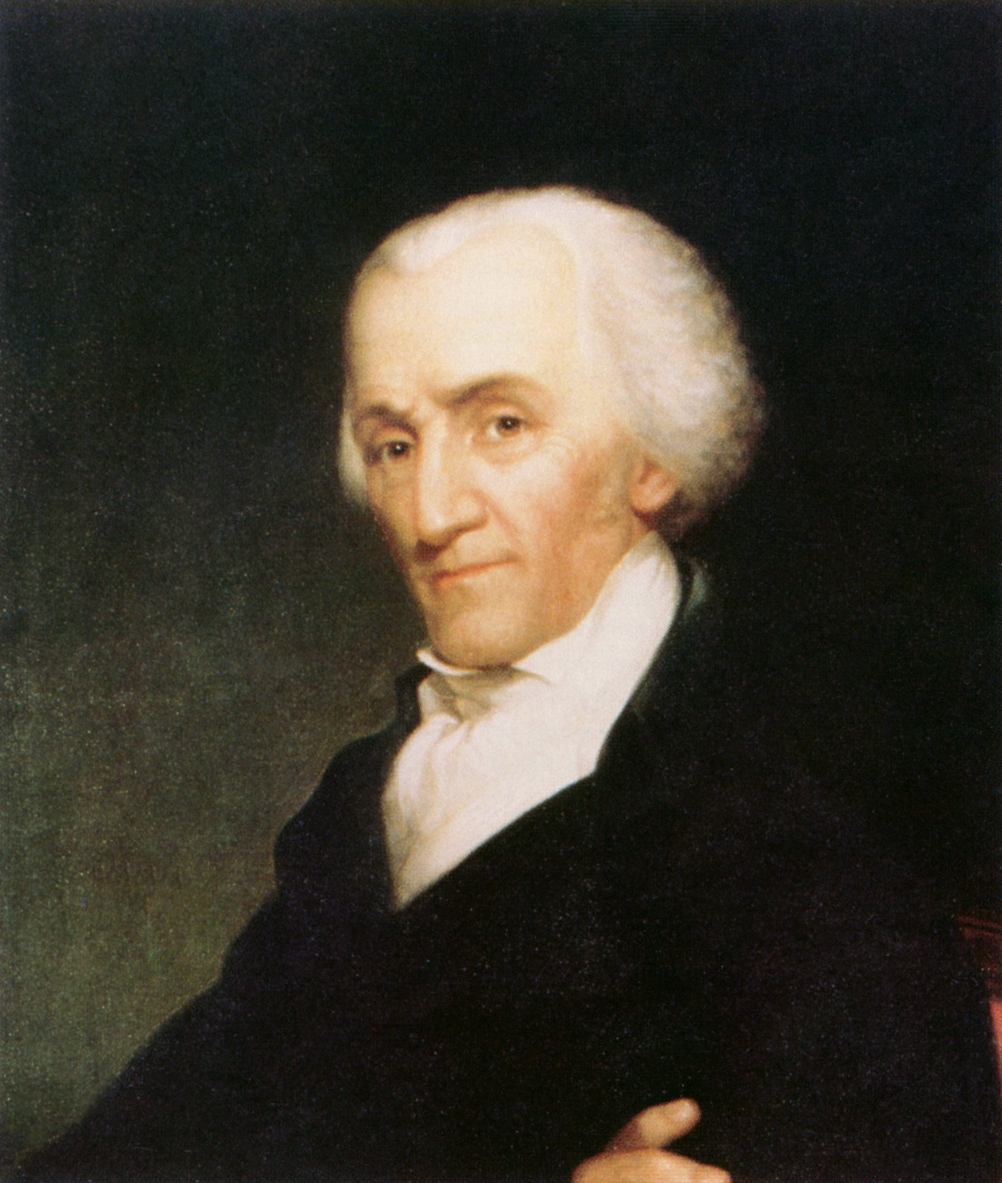

, and Elbridge Gerry

Elbridge Gerry ( ; July 17, 1744 – November 23, 1814) was an American Founding Father, merchant, politician, and diplomat who served as the fifth vice president of the United States under President James Madison from 1813 until his death i ...

, were approached through informal channels by agents of the French foreign minister, Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord

Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord (; ; 2 February 1754 – 17 May 1838), 1st Prince of Benevento, then Prince of Talleyrand, was a French secularization, secularized clergyman, statesman, and leading diplomat. After studying theology, he b ...

, who demanded bribes and a loan before formal negotiations could begin. Although it was widely known that diplomats from other nations had paid bribes to deal with Talleyrand at the time, the Americans were offended by the demands, and eventually left France without ever engaging in formal negotiations. Gerry, seeking to avoid all-out war, remained for several months after the other two commissioners left. His exchanges with Talleyrand laid groundwork for the eventual end to diplomatic affairs and military hostilities.

The failure of the commission caused a political firestorm in the United States when the commission's dispatches were published. It led to the undeclared Quasi-War

The Quasi-War was an undeclared war from 1798 to 1800 between the United States and the French First Republic. It was fought almost entirely at sea, primarily in the Caribbean and off the East Coast of the United States, with minor actions in ...

(1798–1800). Federalists, who controlled both houses of Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

and held the presidency

A presidency is an administration or the executive, the collective administrative and governmental entity that exists around an office of president of a state or nation. Although often the executive branch of government, and often personified b ...

, took advantage of the national anger to build up the nation's military. They also attacked the Democratic-Republicans

The Democratic-Republican Party (also referred to by historians as the Republican Party or the Jeffersonian Republican Party), was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the early 1790s. It championed li ...

for their pro-French stance, and Gerry (a nonpartisan Nonpartisan or non-partisan may refer to:

__NOTOC__ General political concepts

* Nonpartisanship, also known as Nonpartisanism, co-operation without reference to political parties

* Non-partisan democracy, an election with no official recognition ...

at the time) for what they saw as his role in the commission's failure.

Background

In the wake of the 1789 French Revolution, relations between the new French Republic and U.S. federal government, originally friendly, became strained. In 1792, France and the rest of Europe went to war, a conflict in whichPresident

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

declared American neutrality. However, both France and Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

, the major naval powers in the war, seized ships of neutral powers (including those of the United States) that traded with their enemies. With the Jay Treaty

The Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation, Between His Britannic Majesty and the United States of America, commonly known as the Jay Treaty, and also as Jay's Treaty, was a 1794 treaty between the United States and Great Britain that averted ...

, ratified in 1795, the United States reached an agreement on the matter with Britain that angered members of the Directory that governed France. The French Navy

The French Navy (, , ), informally (, ), is the Navy, maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the four military service branches of History of France, France. It is among the largest and most powerful List of navies, naval forces i ...

consequently stepped up its efforts to interrupt American trade with Britain. By the end of Washington's presidency in early 1797, the matter was reaching crisis proportions. Shortly after assuming office on March 4, 1797, President John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Before Presidency of John Adams, his presidency, he was a leader of ...

learned that Charles Cotesworth Pinckney had been refused as U.S. minister because of the escalating crisis, and that American merchant ships had been seized in the Caribbean

The Caribbean ( , ; ; ; ) is a region in the middle of the Americas centered around the Caribbean Sea in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, mostly overlapping with the West Indies. Bordered by North America to the north, Central America ...

. In response, he called upon Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

to meet and address the deteriorating state of French–American relations during a special session

In a legislature, a special session (also extraordinary session) is a period when the body convenes outside of the normal legislative session. This most frequently occurs in order to complete unfinished tasks for the year (often delayed by confli ...

to be held that May.

Popular opinion in the United States on relations with France was divided along largely political lines: Federalists took a hard line, favoring a defensive buildup but not necessarily advocating war, while Democratic-Republicans

The Democratic-Republican Party (also referred to by historians as the Republican Party or the Jeffersonian Republican Party), was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the early 1790s. It championed li ...

expressed solidarity with the republican ideals of the French revolutionaries and did not want to be seen as cooperating with the Federalist Adams administration. Vice President

A vice president or vice-president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vi ...

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

, himself a republican, looked upon Federalists as monarchists who were linked to Britain and therefore hostile to American values.

Commission to France

In late May 1797 Adams met with his cabinet to discuss the situation and to choose a special commission to France. Adams initially proposed that

In late May 1797 Adams met with his cabinet to discuss the situation and to choose a special commission to France. Adams initially proposed that John Marshall

John Marshall (September 24, 1755July 6, 1835) was an American statesman, jurist, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fourth chief justice of the United States from 1801 until his death in 1835. He remai ...

and Elbridge Gerry

Elbridge Gerry ( ; July 17, 1744 – November 23, 1814) was an American Founding Father, merchant, politician, and diplomat who served as the fifth vice president of the United States under President James Madison from 1813 until his death i ...

join Pinckney on the commission, but his cabinet objected to the choice of Gerry because he was not a strong Federalist. Francis Dana

Francis Dana (June 13, 1743 – April 25, 1811) was an American Founding Father, lawyer, jurist, and statesman from Massachusetts. He served as a delegate to the Continental Congress in 1777–1778 and 1784. A signer of the Articles of Confederat ...

was chosen instead of Gerry, but he declined to serve, and Adams, who considered Gerry one of the "two most impartial men in America" (he himself being the other), submitted his name to the United States Senate

The United States Senate is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the United States House of Representatives, U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and ...

in Dana's stead without consulting his cabinet. Adams, in introducing the matter to Congress, made a somewhat belligerent speech in which he called for a vigorous defense of the nation's neutrality and expansion of the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

, but stopped short of calling for war against France. Congress approved this choice of commissioners, and Adams instructed them to negotiate similar terms to those that had been granted to Britain in the Jay Treaty. The commissioners were also instructed to refuse loans, but to be flexible in the arrangement of payment terms for financial matters. Marshall left for Europe in mid-July to join Pinckney, with Gerry following a few weeks later. The political divisions in the commission's makeup were reflected in their attitudes toward the negotiations: Marshall and Pinckney, both Federalists, distrusted the French, while Gerry (who was then opposed to political parties) was willing to be flexible and unhurried in dealing with them.

The French Republic, established in 1792 at the height of the French Revolution, was by 1797 governed by a bicameral legislative assembly, with a five-member French Directory

The Directory (also called Directorate; ) was the system of government established by the Constitution of the Year III, French Constitution of 1795. It takes its name from the committee of 5 men vested with executive power. The Directory gov ...

acting as the national executive. The Directory was undergoing both internal power struggles and struggles with the Council of Five Hundred

The Council of Five Hundred () was the lower house of the legislature of the French First Republic under the Constitution of the Year III. It operated from 31 October 1795 to 9 November 1799 during the French Directory, Directory () period of t ...

, the lower chamber of the legislature. Ministerial changes took place in the first half of 1797, including the selection in July of Charles Maurice de Talleyrand

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English and French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*karilaz'' (in Latin alphabet), whose meaning was ...

as foreign minister

In many countries, the ministry of foreign affairs (abbreviated as MFA or MOFA) is the highest government department exclusively or primarily responsible for the state's foreign policy and relations, diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral r ...

. Talleyrand, who had recently spent a few years in the United States, was openly concerned about the establishment of closer ties between the U.S. and Britain. The Directory, generally not well-disposed to American interests, became notably more hostile to them in September 1797, when an internal coup propelled several anti-Americans into power. These leaders, and Talleyrand, viewed President Adams as hostile to their interests, but did not think that there was significant danger of war. In part based on advice imparted to French diplomats by Jefferson, Talleyrand decided to adopt a measured, slow pace to the negotiations.

The American commission arrived in Paris in early October, and immediately requested a meeting with Talleyrand. After an initial brief meeting (in which Talleyrand only provisionally accepted the commissioners' credentials), a longer meeting was held a week later. Talleyrand sought from the commissioners an explanation for the speech Adams had made in May, which had angered Directory members; his motivation was to determine how favorably the commissioners were disposed to the negotiations. If they responded in an unfavorable manner, the Directory would refuse to accept their credentials. The commissioners first learned of Talleyrand's expected demand on October 14 through an indirect channel. They decided that no explanation would be given for Adams' speech.

The American commission arrived in Paris in early October, and immediately requested a meeting with Talleyrand. After an initial brief meeting (in which Talleyrand only provisionally accepted the commissioners' credentials), a longer meeting was held a week later. Talleyrand sought from the commissioners an explanation for the speech Adams had made in May, which had angered Directory members; his motivation was to determine how favorably the commissioners were disposed to the negotiations. If they responded in an unfavorable manner, the Directory would refuse to accept their credentials. The commissioners first learned of Talleyrand's expected demand on October 14 through an indirect channel. They decided that no explanation would be given for Adams' speech.

Initial meetings

What followed were a series of meetings that took place outside formal diplomatic channels. On October 17, Nicholas Hubbard, an Englishman working for a Dutch bank used by the Americans (and who came to be identified as "W" in the published papers), notified Pinckney that BaronJean-Conrad Hottinguer

Baron Jean-Conrad Hottinguer (15 February 1764, Zurich – 12 September 1841, Castle Piple, Boissy-Saint-Léger) was a Switzerland, Swiss-born French banker who later became a Baron#France, Baron of the French Empire.

Biography

Career

In 1784, ...

, whom Hubbard described only as a man of honor, wished to meet with him. Pinckney agreed, and the two men met the next evening. Hottinguer (who was later identified as "X") relayed a series of French demands, which included a large loan to the French government and the payment of a £50,000 bribe to Talleyrand. Pinckney relayed these demands to the other commissioners, and Hottinguer repeated them to the entire commission, which curtly refused the demands, even though it was widely known that diplomats from other nations had paid bribes to deal with Talleyrand. Hottinguer then introduced the commission to Pierre Bellamy ("Y"), whom he represented as being a member of Talleyrand's inner circle. Bellamy expounded in detail on Talleyrand's demands, including the expectation that "you must pay a great deal of money". He even proposed a series of purchases (at inflated prices) of currency as a means by which such money could be clandestinely exchanged. The commissioners offered to send one of their number back to the United States for instructions, if the French would suspend their seizures of American shipping; the French negotiators refused.

Not long after this standoff, Talleyrand sent Lucien Hauteval ("Z") to meet with Elbridge Gerry. The two men knew each other, having met in Boston in 1792. Hauteval assured Gerry of Talleyrand's sincerity in seeking peace, and encouraged him to keep the informal negotiations open. He reiterated the demands for a loan and bribe.

A week later (notably after the signing of the

Not long after this standoff, Talleyrand sent Lucien Hauteval ("Z") to meet with Elbridge Gerry. The two men knew each other, having met in Boston in 1792. Hauteval assured Gerry of Talleyrand's sincerity in seeking peace, and encouraged him to keep the informal negotiations open. He reiterated the demands for a loan and bribe.

A week later (notably after the signing of the Treaty of Campo Formio

The Treaty of Campo Formio (today Campoformido) was signed on 17 October 1797 (26 Vendémiaire VI) by Napoleon Bonaparte and Count Philipp von Cobenzl as representatives of the French Republic and the Austrian monarchy, respectively. The trea ...

, which ended the five-year War of the First Coalition

The War of the First Coalition () was a set of wars that several European powers fought between 1792 and 1797, initially against the Constitutional Cabinet of Louis XVI, constitutional Kingdom of France and then the French First Republic, Frenc ...

between France and most of the other European powers), Hottinguer and Bellamy again met with the commission, and repeated their original demands, accompanied by threats of potential war, since France was at least momentarily at peace in Europe. Pinckney's response was famous: "No, no, not a sixpence!" The commissioners decided on November 1 to refuse further negotiations by informal channels. Publication of dispatches describing this series of meetings would form the basis for the later political debates in the United States.

Later negotiations

The commissioners soon discovered that only unofficial channels were open to them. Over the next several months, Talleyrand sent a series of informal negotiators to meet with and influence the commissioners. Some of the informal avenues were closed down (Gerry, for instance, informed Hauteval that they could no longer meet, since Hauteval had no formal authority), and Talleyrand finally appeared in November 1797 at a dinner, primarily to castigate the Americans for their unwillingness to accede to the demand for a bribe. In late November, Talleyrand began maneuvering to separate Gerry from the other commissioners. He extended a "social" dinner invitation to Gerry, which the latter, seeking to maintain communications, planned to attend. The matter heightened distrust of Gerry by Marshall and Pinckney, who sought guarantees that Gerry would limit any representations and agreements he might consider. Despite seeking to refuse informal negotiations, all of the commissioners ended up having private meetings with some of Talleyrand's negotiators.

The commissioners eventually divided over the issue of whether to continue informal negotiations, with the Federalists Marshall and Pinckney opposed, and Gerry in favor. This division was eventually clear to Talleyrand, who told Gerry in January 1798 that he would no longer deal with Pinckney. In February, Talleyrand gained approval from the Directory for a new bargaining position, and he maneuvered to exclude Marshall from the negotiations as well. The change in strategy alarmed a number of American residents of Paris, who reported the growing possibility of war. Around this time Gerry, at Talleyrand's insistence, began keeping secret from the other commissioners the substance of their meetings.

All three commissioners met with Talleyrand informally in March, but it was clear that the parties were at an impasse. This appeared to be the case despite Talleyrand's agreement to drop the demand for a loan. Both sides prepared statements to be sent across the Atlantic stating their positions, and Marshall and Pinckney, frozen out of talks that Talleyrand would only conduct with Gerry, left France in April. Their departure was delayed due to a series of negotiations over the return of their passports; in order to obtain diplomatic advantage, Talleyrand sought to force Marshall and Pinckney to formally request their return (which would allow him to later claim that they broke off negotiations). Talleyrand eventually gave in, formally requesting their departure. Gerry, although he sought to maintain unity with his co-commissioners, was told by Talleyrand that if he left France the Directory would declare war. Gerry remained behind, protesting the "impropriety of permitting a foreign government to hoosethe person who should negotiate." He however remained optimistic that war was unrealistic, writing to William Vans Murray, the American minister to The Netherlands, that "nothing but madness" would cause the French to declare war.

Gerry resolutely refused to engage in further substantive negotiations with Talleyrand, agreeing only to stay until someone with more authority could replace him, and wrote to President Adams requesting assistance in securing his departure from Paris. Talleyrand eventually sent representatives to The Hague to reopen negotiations with William Vans Murray, and Gerry finally returned home in October 1798.

In late November, Talleyrand began maneuvering to separate Gerry from the other commissioners. He extended a "social" dinner invitation to Gerry, which the latter, seeking to maintain communications, planned to attend. The matter heightened distrust of Gerry by Marshall and Pinckney, who sought guarantees that Gerry would limit any representations and agreements he might consider. Despite seeking to refuse informal negotiations, all of the commissioners ended up having private meetings with some of Talleyrand's negotiators.

The commissioners eventually divided over the issue of whether to continue informal negotiations, with the Federalists Marshall and Pinckney opposed, and Gerry in favor. This division was eventually clear to Talleyrand, who told Gerry in January 1798 that he would no longer deal with Pinckney. In February, Talleyrand gained approval from the Directory for a new bargaining position, and he maneuvered to exclude Marshall from the negotiations as well. The change in strategy alarmed a number of American residents of Paris, who reported the growing possibility of war. Around this time Gerry, at Talleyrand's insistence, began keeping secret from the other commissioners the substance of their meetings.

All three commissioners met with Talleyrand informally in March, but it was clear that the parties were at an impasse. This appeared to be the case despite Talleyrand's agreement to drop the demand for a loan. Both sides prepared statements to be sent across the Atlantic stating their positions, and Marshall and Pinckney, frozen out of talks that Talleyrand would only conduct with Gerry, left France in April. Their departure was delayed due to a series of negotiations over the return of their passports; in order to obtain diplomatic advantage, Talleyrand sought to force Marshall and Pinckney to formally request their return (which would allow him to later claim that they broke off negotiations). Talleyrand eventually gave in, formally requesting their departure. Gerry, although he sought to maintain unity with his co-commissioners, was told by Talleyrand that if he left France the Directory would declare war. Gerry remained behind, protesting the "impropriety of permitting a foreign government to hoosethe person who should negotiate." He however remained optimistic that war was unrealistic, writing to William Vans Murray, the American minister to The Netherlands, that "nothing but madness" would cause the French to declare war.

Gerry resolutely refused to engage in further substantive negotiations with Talleyrand, agreeing only to stay until someone with more authority could replace him, and wrote to President Adams requesting assistance in securing his departure from Paris. Talleyrand eventually sent representatives to The Hague to reopen negotiations with William Vans Murray, and Gerry finally returned home in October 1798.

Reaction in the United States

While the American diplomats were in Europe, President Adams considered his options in the event of the commission's failure. His cabinet urged that the nation's military be strengthened, including the raising of a 20,000-man army and the acquisition or construction of

While the American diplomats were in Europe, President Adams considered his options in the event of the commission's failure. His cabinet urged that the nation's military be strengthened, including the raising of a 20,000-man army and the acquisition or construction of ships of the line

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed during the Age of Sail from the 17th century to the mid-19th century. The ship of the line was designed for the naval tactic known as the line of battle, which involved the two column ...

for the navy. He had no substantive word from the commissioners until March 1798, when the first dispatches revealing the French demands and negotiating tactics arrived. The commission's apparent failure was duly reported to Congress, although Adams kept secret the mistreatment (lack of recognition and demand for a bribe) of the diplomats, seeking to minimize a warlike reaction. His cabinet was divided on how to react: the general tenor was one of hostility toward France, with Attorney General Charles Lee and Secretary of State Timothy Pickering

Timothy Pickering (July 17, 1745January 29, 1829) was the third United States Secretary of State, serving under Presidents George Washington and John Adams. He also represented Massachusetts in both houses of United States Congress, Congress as ...

arguing for a declaration of war. Democratic-Republican leaders in Congress, believing Adams had exaggerated the French position because he sought war, united with hawkish Federalists to demand the release of the commissioners' dispatches. On March 20, Adams turned them over, with the names of some of the French actors redacted and replaced by the letters W, X, Y, and Z. The use of these disguising letters led the business to immediately become known as the "XYZ Affair."

The release of the dispatches produced exactly the response Adams feared. Federalists called for war, and Democratic-Republicans were left without an effective argument against them, having miscalculated the reason for Adams' secrecy. Despite those calls, Adams steadfastly refused to ask Congress for a formal war declaration. Congress nonetheless authorized the acquisition of twelve frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and maneuvera ...

s, and made other appropriations to increase military readiness; it also, on July 7, 1798, voted to nullify the 1778 Treaty of Alliance with France, and two days later authorized attacks on French warships.

Partisan responses

Federalists used the dispatches to question the loyalty of pro-French Democratic-Republicans; this attitude contributed to the passage of theAlien and Sedition Acts

The Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 were a set of four United States statutes that sought, on national security grounds, to restrict immigration and limit 1st Amendment protections for freedom of speech. They were endorsed by the Federalist Par ...

, restricting the movements and actions of foreigners, and limiting speech critical of the government. Federalists were otherwise divided on the question of war, and the Democratic-Republicans painted hawkish Federalists as warmongers seeking to undermine the republic by military means.

Elbridge Gerry was placed in a difficult position upon his return to the United States. Federalists, spurred by John Marshall's accounts of their disagreements, criticized him for abetting the breakdown of the negotiations. These bitterly harsh and partisan comments turned Gerry against the Federalists, and he eventually ended up joining with the Democratic-Republicans in 1800.

Political reaction in France

When news reached France of the publication of the dispatches and the ensuing hostile reaction, the response was one of fury. Talleyrand was called to the Directory to account for his role in the affair. He denied all association with the informal negotiators, and enlisted the assistance of Gerry in exposing the agents whose names had been redacted, a charade Gerry agreed to participate in. In exchange Talleyrand confirmed privately to Gerry that the agents were in fact in his employ, and that he was, contrary to statements made to the Directory, interested in pursuing reconciliation. President Adams later wrote that Talleyrand's confession to Gerry was significant in his decision to continue efforts to maintain peace. Gerry, in his private report on the affair to Adams in 1799, claimed credit for maintaining the peace, and for influencing significant changes in French policy that lessened the hostilities and eventually brought a peace treaty. The warlike attitude of the United States and the start of theQuasi-War

The Quasi-War was an undeclared war from 1798 to 1800 between the United States and the French First Republic. It was fought almost entirely at sea, primarily in the Caribbean and off the East Coast of the United States, with minor actions in ...

(a naval war between the two countries that was fought primarily in the Caribbean) convinced Talleyrand that he had miscalculated in his dealings with the commissioners. In response to the diplomatic overtures he made to William Vans Murray in The Hague, President Adams sent negotiators to France in 1799 who eventually negotiated an end to hostilities with the Convention of 1800

The Convention of 1800, also known as the Treaty of Mortefontaine (French: ''Traité de Mortefontaine''), was signed on September 30, 1800, by the United States and France. The difference in name was due to congressional sensitivity at entering i ...

(whose negotiations were managed in part by Marshall, then Secretary of State) in September 1800. This agreement was made with First Consul

The Consulate () was the top-level government of the First French Republic from the fall of the Directory in the coup of 18 Brumaire on 9 November 1799 until the start of the French Empire on 18 May 1804.

During this period, Napoleon Bonap ...

Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

, who had overthrown the Directory in the Coup of 18 Brumaire

The Coup of 18 Brumaire () brought Napoleon Bonaparte to power as First Consul of the French First Republic. In the view of most historians, it ended the French Revolution and would soon lead to the coronation of Napoleon as Emperor of the Fr ...

in November 1799, and it was ratified by the United States Senate

The United States Senate is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the United States House of Representatives, U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and ...

in December 1801.

See also

* Timeline of United States diplomatic historyNotes

References

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * * *Further reading

* Berkin, Carol. ''A Sovereign People: The Crises of the 1790s and the Birth of American Nationalism'' (2017) pp. 151–200. * * DeConde, Alexander. ''The Quasi-War: The Politics and Diplomacy of the Undeclared War with France, 1797–1801'' (1966). * Kleber, Louis C. "The "X Y Z" Affair" ''History Today''. (Oct 1973), Vol. 23 Issue 10, pp 715–723 online; popular account. *External links

Transcript of Adams speech on the release of the XYZ papers

"The XYZ Affair and the Quasi-War with France, 1798–1800"

U.S. Department of State, Office of the Historian {{DEFAULTSORT:Xyz Affair 1797 in France 1798 in France 1797 in international relations 1798 in international relations 1797 in the United States 1798 in the United States 18th-century controversies in the United States History of the foreign relations of the United States History of the foreign relations of France Diplomatic crises of the 18th century Political controversies in the United States Quasi-War Presidency of John Adams France–United States relations 5th United States Congress Political controversies in France Elbridge Gerry