World government is the concept of a single political authority

governing all of Earth and humanity. It is conceived in a variety of forms, from

tyrannical to

democratic, which reflects its wide array of proponents and detractors.

There has never been a world

government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive (government), execu ...

with executive, legislative, and judicial functions and an administrative apparatus; the inception of the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

(UN) in the mid-20th century remains the closest approximation to a world government, as it is by far the largest and most powerful

international institution. The UN is mostly limited to an advisory role, with the stated purpose of fostering cooperation between existing

national governments, rather than exerting authority over them. Nevertheless, the organization is commonly viewed as either a model for, or preliminary step towards, a global government.

The concept of universal governance has existed since antiquity and been the subject of discussion, debate, and even advocacy by political authorities, philosophers, religious leaders, and

secular humanists. Interest in the subject has coincided with increasing

globalization

Globalization is the process of increasing interdependence and integration among the economies, markets, societies, and cultures of different countries worldwide. This is made possible by the reduction of barriers to international trade, th ...

and related trends. Some proponents argue that world government is a natural and inevitable outcome of human social evolution. Opposition to world government, which comes from a broad political spectrum, is predicated on concerns that it is a tool for violent totalitarianism, unfeasible, or simply unnecessary.

Definition

Alexander Wendt defines a state as an "organization possessing a monopoly on the legitimate use of organized violence within a society."

According to Wendt, a world state would need to fulfill the following requirements:

#

Monopoly on organized violence – states have exclusive use of legitimate force within their own territory.

#

Legitimacy – perceived as right by their populations, and possibly the global community.

#

Sovereignty

Sovereignty can generally be defined as supreme authority. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within a state as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the person, body or institution that has the ultimate au ...

– possessing common power and legitimacy.

#

Corporate action

A corporate action is an event initiated by a public company that brings or could bring an actual change to the debt securities—Share capital, equity or debt—issued by the company. Corporate actions are typically agreed upon by a company's ...

– a collection of individuals who act together in a systematic way.

Wendt argues that a world government would not require a centrally controlled army or a central decision-making body, as long as the four conditions are fulfilled.

In order to develop a world state, three changes must occur in the world system:

# Universal security community – a peaceful system of binding

dispute resolution

Dispute resolution or dispute settlement is the process of resolving disputes between parties. The term ''dispute resolution'' is '' conflict resolution'' through legal means.

Prominent venues for dispute settlement in international law incl ...

without threat of interstate violence.

# Universal

collective security

Collective security is arrangement between states in which the institution accepts that an attack on one state is the concern of all and merits a collective response to threats by all. Collective security was a key principle underpinning the Lea ...

– unified response to crimes and threats.

#

Supranational authority – binding decisions are made that apply to each and every state.

The development of a world government is conceptualized by Wendt as a process through five stages:

# System of states;

# Society of states;

# World society;

# Collective security;

# World state.

Wendt argues that a struggle among sovereign individuals results in the formation of a collective identity and eventually a state. The same forces are present within the international system and could possibly, and potentially inevitably lead to the development of a world state through this five-stage process. When the world state would emerge, the traditional expression of states would become localized expressions of the world state. This process occurs within the default state of anarchy present in the world system.

Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German Philosophy, philosopher and one of the central Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works ...

conceptualized the state as sovereign individuals formed out of conflict.

Part of the traditional philosophical objections to a world state (Kant, Hegel)

are overcome by modern technological innovations. Wendt argues that new methods of communication and coordination can overcome these challenges.

A colleague of Wendt in the field of International Relations, Max Ostrovsky, conceptualized the development of a world government as a process in one stage: The world will be divided on two rival blocs, one based on North America and another on Eurasia, which clash in

World War III and, "if civilization survives," the victorious power conquers the rest of the world, annexes and establishes world state. Remarkably, Wendt also supposes the alternative of universal conquest leading to world state, provided the conquering power recognizes "its victims as full subjects." In such case, the mission is accomplished "without intermediate stages of development."

Pre-modern philosophy

Antiquity

World government was an aspiration of ancient rulers as early as the

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

(3300 to 1200 BCE);

ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower E ...

ian kings aimed to rule "All That the Sun Encircles",

Mesopotamian

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary o ...

kings "All from the Sunrise to the Sunset", and

ancient Chinese and

Japanese emperors "All under Heaven".

The Chinese had a particularly well-developed notion of world government in the form of

Great Unity, or (), a historical model for a united and just society bound by moral virtue and principles of

good governance. The

Han dynasty

The Han dynasty was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China (202 BC9 AD, 25–220 AD) established by Liu Bang and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by the short-lived Qin dynasty (221–206 BC ...

, which successfully united much of China for over four centuries, evidently aspired to this vision by erecting an Altar of the Great Unity in 113 BCE. According to

Mencius

Mencius (孟子, ''Mèngzǐ'', ; ) was a Chinese Confucian philosopher, often described as the Second Sage () to reflect his traditional esteem relative to Confucius himself. He was part of Confucius's fourth generation of disciples, inheriting ...

(1:6) stability is in unity. Both Mencius (9:4) and Alexander the Great (

Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus or Diodorus of Sicily (; 1st century BC) was an ancient Greece, ancient Greek historian from Sicily. He is known for writing the monumental Universal history (genre), universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty ...

30:21) claimed that there are neither two suns in cosmos, nor two monarchs on earth.

Contemporaneously, the

ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

historian

Polybius

Polybius (; , ; ) was a Greek historian of the middle Hellenistic period. He is noted for his work , a universal history documenting the rise of Rome in the Mediterranean in the third and second centuries BC. It covered the period of 264–146 ...

described

Roman rule over much of

the known world at the time as a "marvelous" achievement worthy of consideration by future historians. The ''

Pax Romana'', a roughly two-century period of stable Roman hegemony across three continents, reflected the positive aspirations of a world government, as it was deemed to have brought prosperity and security to what was once a politically and culturally fractious region. The

Adamites were a Christian sect who desired to organize an early form of world government.

Dante's Universal Monarchy

The idea of world government outlived the

fall of Rome

The fall of the Western Roman Empire, also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome, was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its vast ...

for centuries, particularly in its former heartland of Italy. Medieval peace movements such as the

Waldensians

The Waldensians, also known as Waldenses (), Vallenses, Valdesi, or Vaudois, are adherents of a church tradition that began as an ascetic movement within Western Christianity before the Reformation. Originally known as the Poor of Lyon in the l ...

gave impetus to utopian philosophers like

Marsilius of Padua to envision a world without war.

In his fourteenth-century work ''

De Monarchia'', Florentine poet and philosopher

Dante Alighieri

Dante Alighieri (; most likely baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri; – September 14, 1321), widely known mononymously as Dante, was an Italian Italian poetry, poet, writer, and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called ...

appealed for a

universal monarchy that would work separate from and uninfluenced by the

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

to establish peace in humanity's lifetime and the afterlife, respectively:

But what has been the condition of the world since that day the seamless robe f Pax Romanafirst suffered mutilation by the claws of avarice, we can read—would that we could not also see! O human race! what tempests must need toss thee, what treasure be thrown into the sea, what shipwrecks must be endured, so long as thou, like a beast of many heads, strivest after diverse ends! Thou art sick in either intellect, or sick likewise in thy affection. Thou healest not thy high understanding by argument irrefutable, nor thy lower by the countenance of experience. Nor dost thou heal thy affection by the sweetness of divine persuasion, when the voice of the Holy Spirit

The Holy Spirit, otherwise known as the Holy Ghost, is a concept within the Abrahamic religions. In Judaism, the Holy Spirit is understood as the divine quality or force of God manifesting in the world, particularly in acts of prophecy, creati ...

breathes upon thee, 'Behold, how good and how pleasant it is for brethren to dwell together in unity!'

Di Gattinara was an Italian diplomat who widely promoted Dante's ''De Monarchia'' and its call for a universal monarchy. An advisor of

Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor

Maximilian I (22 March 1459 – 12 January 1519) was King of the Romans from 1486 and Holy Roman Emperor from 1508 until his death in 1519. He was never crowned by the Pope, as the journey to Rome was blocked by the Venetians. He proclaimed hi ...

, and the chancellor of

Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

Charles V (24 February 1500 – 21 September 1558) was Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria from 1519 to 1556, King of Spain (as Charles I) from 1516 to 1556, and Lord of the Netherlands as titular Duke of Burgundy (as Charles II) ...

, he conceived global government as uniting all

Christian nations under a

Respublica Christiana, which was the only political entity able to establish

world peace

World peace is the concept of an ideal state of peace within and among all people and nations on Earth. Different cultures, religions, philosophies, and organizations have varying concepts on how such a state would come about.

Various relig ...

.

Modern philosophy

Francisco de Vitoria (1483–1546)

The

Spanish philosopher

Francisco de Vitoria

Francisco de Vitoria ( – 12 August 1546; also known as Francisco de Victoria) was a Spanish Roman Catholic philosopher, theologian, and jurist of Renaissance Spain. He is the founder of the tradition in philosophy known as the School of Sala ...

is considered an author of "global political philosophy" and international law, along with

Alberico Gentili

Alberico Gentili (14 January 155219 June 1608) was an Italian jurist, a tutor of Queen Elizabeth I, and a standing advocate to the Spanish Embassy in London, who served as the Regius Professor of Civil Law at the University of Oxford for 21 ye ...

and

Hugo Grotius

Hugo Grotius ( ; 10 April 1583 – 28 August 1645), also known as Hugo de Groot () or Huig de Groot (), was a Dutch humanist, diplomat, lawyer, theologian, jurist, statesman, poet and playwright. A teenage prodigy, he was born in Delft an ...

. This came at a time when the

University of Salamanca

The University of Salamanca () is a public university, public research university in Salamanca, Spain. Founded in 1218 by Alfonso IX of León, King Alfonso IX, it is the oldest university in the Hispanic world and the fourth oldest in the ...

was engaged in unprecedented thought concerning

human rights

Human rights are universally recognized Morality, moral principles or Social norm, norms that establish standards of human behavior and are often protected by both Municipal law, national and international laws. These rights are considered ...

,

international law

International law, also known as public international law and the law of nations, is the set of Rule of law, rules, norms, Customary law, legal customs and standards that State (polity), states and other actors feel an obligation to, and generall ...

, and early economics based on the experiences of the

Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire, sometimes referred to as the Hispanic Monarchy (political entity), Hispanic Monarchy or the Catholic Monarchy, was a colonial empire that existed between 1492 and 1976. In conjunction with the Portuguese Empire, it ushered ...

. De Vitoria conceived of the , or the "republic of the whole world".

Hugo Grotius (1583–1645)

The Dutch philosopher and jurist Hugo Grotius, widely regarded as a founder of international law, believed in the eventual formation of a world government to enforce it. His book, ''

De jure belli ac pacis'' (''On the Law of War and Peace''), published in Paris in 1625, is still cited as a foundational work in the field. Though he does not advocate for world government ''per se,'' Grotius argues that a "common law among nations", consisting of a framework of principles of natural law, bind all people and societies regardless of local custom.

Immanuel Kant (1724–1804)

In his essay "

Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch" (1795),

Kant describes three basic requirements for organizing human affairs to permanently abolish the threat of present and future war, and, thereby, help establish a new era of lasting peace throughout the world. Kant described his proposed peace program as containing two steps.

The "Preliminary Articles" described the steps that should be taken immediately, or with all deliberate speed:

# "No Secret Treaty of Peace Shall Be Held Valid in Which There Is Tacitly Reserved Matter for a Future War"

# "No Independent States, Large or Small, Shall Come under the Dominion of Another State by Inheritance, Exchange, Purchase, or Donation"

# "

Standing Armies Shall in Time Be Totally Abolished"

# "

National Debts Shall Not Be Contracted with a View to the External Friction of States"

# "No State Shall by Force Interfere with the

Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these pri ...

or

Government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive (government), execu ...

of Another State,

# "No State Shall, during War, Permit Such Acts of Hostility Which Would Make Mutual Confidence in the Subsequent Peace Impossible: Such Are the Employment of Assassins (), Poisoners (), Breach of Capitulation, and Incitement to Treason () in the Opposing State"

Three Definitive Articles would provide not merely a cessation of hostilities, but a foundation on which to build a peace.

# "The Civil Constitution of Every State Should Be Republican"

# "The Law of Nations Shall be Founded on a Federation of Free States"

# "The Law of

World Citizenship Shall Be Limited to Conditions of Universal Hospitality"

Kant argued against a world government on the grounds that it would be prone to tyranny. He instead advocated for league of independent republican states akin to the intergovernmental organizations that would emerge over a century and a half later.

Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762–1814)

The year of the

battle at Jena (1806), when

Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

overwhelmed

Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

,

Johann Gottlieb Fichte

Johann Gottlieb Fichte (; ; 19 May 1762 – 29 January 1814) was a German philosopher who became a founding figure of the philosophical movement known as German idealism, which developed from the theoretical and ethical writings of Immanuel Ka ...

in ''

Characteristics of the Present Age'' described what he perceived to be a very deep and dominant historical trend:

Supranational movements

International organizations started forming in the late 19th century, among the earliest being the

International Committee of the Red Cross

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) is a humanitarian organization based in Geneva, Switzerland, and is a three-time Nobel Prize laureate. The organization has played an instrumental role in the development of rules of war and ...

in 1863, the

Telegraphic Union in 1865 and the

Universal Postal Union in 1874. The increase in international trade at the turn of the 20th century accelerated the formation of international organizations, and, by the start of

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

in 1914, there were approximately 450 of them.

Some notable philosophers and political leaders were also promoting the value of world government during the post-industrial, pre-World War era.

Ulysses S. Grant, US president, was convinced that rapid advances in technology and industry would result in greater unity and eventually "one nation, so that armies and navies are no longer necessary." In China, political reformer

Kang Youwei viewed human political organization growing into fewer, larger units, eventually into "one world".

Bahá'u'lláh founded the

Baháʼí Faith

The Baháʼí Faith is a religion founded in the 19th century that teaches the Baháʼí Faith and the unity of religion, essential worth of all religions and Baháʼí Faith and the unity of humanity, the unity of all people. Established by ...

teaching that the establishment of world unity and a global federation of nations was a

key principle of the religion. Author

H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells (21 September 1866 – 13 August 1946) was an English writer, prolific in many genres. He wrote more than fifty novels and dozens of short stories. His non-fiction output included works of social commentary, politics, hist ...

was a strong proponent of the creation of a world state, arguing that such a state would ensure world peace and justice.

Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

, the traditional founder of communism, predicted a socialist epoch in which the working class throughout the world will unite to render nationalism meaningless. Anti-Communists believed world government was a goal of

World Communism.

Support for the idea of establishing international law grew during this period as well. The

Institute of International Law was formed in 1873 by Belgian jurist

Gustave Rolin-Jaequemyns, leading to the creation of concrete legal drafts, for example by the Swiss Johaan Bluntschli in 1866. In 1883,

James Lorimer published "The Institutes of the Law of Nations" in which he explored the idea of a world government establishing the global rule of law. The first embryonic world

parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

, called the

Inter-Parliamentary Union

The Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU; , UIP) is an international organization of national parliaments. Its primary purpose is to promote democratic governance, accountability, and cooperation among its members; other initiatives include advancing g ...

, was organized in 1886 by Cremer and Passy, composed of legislators from many countries. In 1904 the Union formally proposed "an international congress which should meet periodically to discuss international questions".

Theodore Roosevelt

As early as his 1905 statement to Congress, U.S. president

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

highlighted the need for "an organization of the civilized nations" and cited the international arbitration tribunal at The Hague as a role model to be advanced further. During his acceptance speech for the

1906 Nobel Peace Prize, Roosevelt described a world federation as a "master stroke" and advocated for some form of international police power to maintain peace. Historian

William Roscoe Thayer observed that the speech "foreshadowed many of the terms which have since been preached by the advocates of a League of Nations", which would not be established for another 14 years.

Hamilton Holt of ''The Independent'' lauded Roosevelt's plan for a "Federation of the World", writing that not since the "Great Design" of Henry IV has "so comprehensive a plan" for universal peace been proposed.

Although Roosevelt supported global government conceptually, he was critical of specific proposals and of leaders of organizations promoting the cause of international governance. According to historian

John Milton Cooper, Roosevelt praised the plan of his presidential successor,

William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) served as the 27th president of the United States from 1909 to 1913 and the tenth chief justice of the United States from 1921 to 1930. He is the only person to have held both offices. ...

, for "a league under existing conditions and with such wisdom in refusing to let adherence to the principle be clouded by insistence upon improper or unimportant methods of enforcement that we can speak of the league as a practical matter."

In a 1907 letter to

Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie ( , ; November 25, 1835August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the History of the iron and steel industry in the United States, American steel industry in the late ...

, Roosevelt expressed his hope "to see The Hague Court greatly increased in power and permanency", and in one of his very last public speeches he said: "Let us support any reasonable plan whether in the form of a League of Nations or in any other shape, which bids fair to lessen the probable number of future wars and to limit their scope."

Founding of the League of Nations

The

League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

(LoN) was an intergovernmental organization founded as a result of the

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace ...

in 1919–1920. At its largest size from 28 September 1934 to 23 February 1935, it had 58 members. The League's goals included upholding the

Rights of Man, such as the rights of non-whites, women, and soldiers;

disarmament

Disarmament is the act of reducing, limiting, or abolishing Weapon, weapons. Disarmament generally refers to a country's military or specific type of weaponry. Disarmament is often taken to mean total elimination of weapons of mass destruction, ...

, preventing war through

collective security

Collective security is arrangement between states in which the institution accepts that an attack on one state is the concern of all and merits a collective response to threats by all. Collective security was a key principle underpinning the Lea ...

, settling disputes between countries through negotiation,

diplomacy

Diplomacy is the communication by representatives of State (polity), state, International organization, intergovernmental, or Non-governmental organization, non-governmental institutions intended to influence events in the international syste ...

, and improving global

quality of life

Quality of life (QOL) is defined by the World Health Organization as "an individual's perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards ...

. The diplomatic philosophy behind the League represented a fundamental shift in thought from the preceding hundred years. The League lacked its own armed force and so depended on the

Great Powers to enforce its resolutions and economic sanctions and provide an army, when needed. However, these powers proved reluctant to do so. Lacking many of the key elements necessary to maintain world peace, the League failed to prevent World War II.

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

withdrew

Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

from the League of Nations once he planned to take over Europe. The rest of the

Axis Powers

The Axis powers, originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis and also Rome–Berlin–Tokyo Axis, was the military coalition which initiated World War II and fought against the Allies of World War II, Allies. Its principal members were Nazi Ge ...

soon followed him. Having failed its primary goal, the League of Nations fell apart. The League of Nations consisted of the Assembly, the council, and the Permanent Secretariat. Below these were many agencies. The Assembly was where delegates from all member states conferred. Each country was allowed three representatives and one vote.

Competing visions during World War II

The

Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party ( or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported the ideology of Nazism. Its precursor ...

of Germany envisaged the establishment of a world government under the complete

hegemony

Hegemony (, , ) is the political, economic, and military predominance of one State (polity), state over other states, either regional or global.

In Ancient Greece (ca. 8th BC – AD 6th c.), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of ...

of the

Third Reich

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a totalitarian dictat ...

.

[Weinberg, Gerhard L. (1995) ''Germany, Hitler, and World War II: Essays in modern German and world history''. ]Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press was the university press of the University of Cambridge. Granted a letters patent by King Henry VIII in 1534, it was the oldest university press in the world. Cambridge University Press merged with Cambridge Assessme ...

p. 36

In its move to overthrow the post-

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace ...

, Germany had already withdrawn itself from the

League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

, and it did not intend to join a similar

internationalist organization ever again. In his stated political aim of expanding the living space (''

Lebensraum

(, ) is a German concept of expansionism and Völkisch movement, ''Völkisch'' nationalism, the philosophy and policies of which were common to German politics from the 1890s to the 1940s. First popularized around 1901, '' lso in:' beca ...

'') of the

Germanic people

The Germanic peoples were tribal groups who lived in Northern Europe in Classical antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. In modern scholarship, they typically include not only the Roman-era ''Germani'' who lived in both ''Germania'' and parts of ...

by destroying or driving out "lesser-deserving races" in and from other territories, dictator

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

devised an ideological system of self-perpetuating

expansionism

Expansionism refers to states obtaining greater territory through military Imperialism, empire-building or colonialism.

In the classical age of conquest moral justification for territorial expansion at the direct expense of another established p ...

, in which the growth of a state's population would require the conquest of more territory which would, in turn, lead to a further growth in population which would then require even more conquests.

In 1927,

Rudolf Hess

Rudolf Walter Richard Hess (Heß in German; 26 April 1894 – 17 August 1987) was a German politician, Nuremberg trials, convicted war criminal and a leading member of the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany, Germany. Appointed Deputy Führer ( ...

relayed to

Walther Hewel Hitler's belief that

world peace

World peace is the concept of an ideal state of peace within and among all people and nations on Earth. Different cultures, religions, philosophies, and organizations have varying concepts on how such a state would come about.

Various relig ...

could only be acquired "when one power, the

racially best one, has attained uncontested supremacy". When this control would be achieved, this power could then set up for itself a world police and assure itself "the necessary living space.... The lower races will have to restrict themselves accordingly".

During its imperial period (1868–1947), the

Japanese Empire elaborated a worldview, , translated as "eight corners of the world under one roof". This was the idea behind the attempt to establish a

Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere and behind the struggle for world domination. The British Empire, the largest in history, was viewed by some historians as a form of world government.

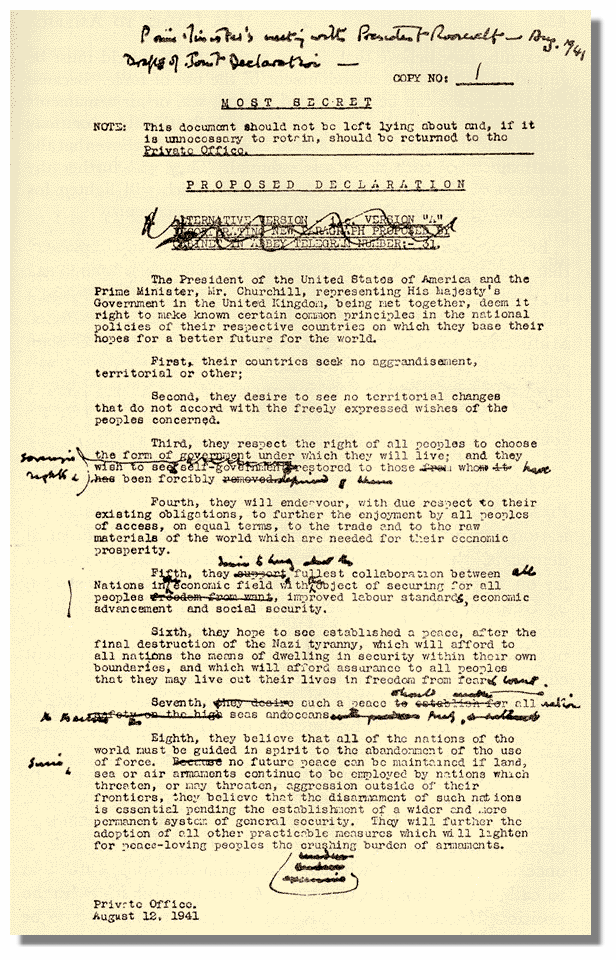

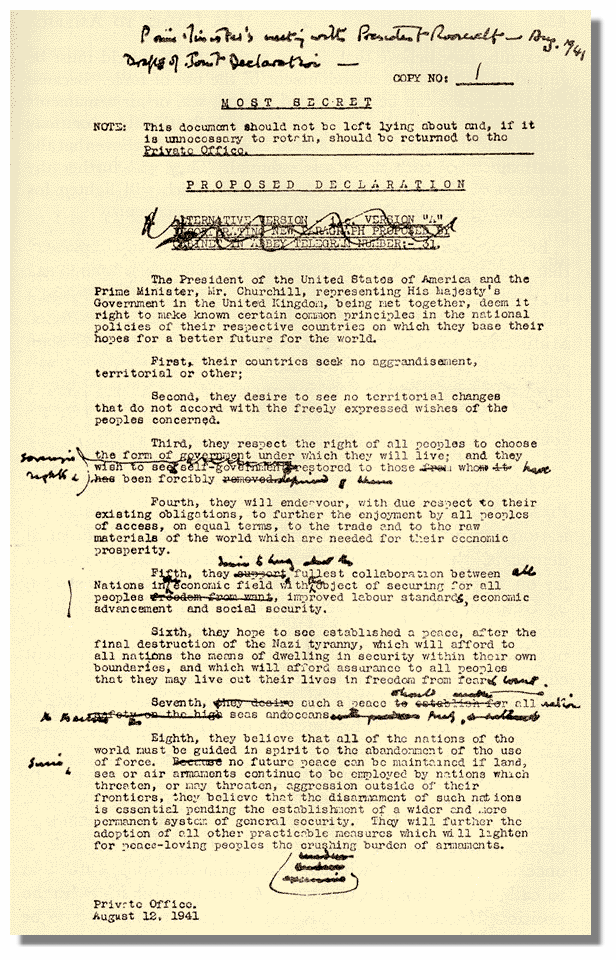

The

Atlantic Charter

The Atlantic Charter was a statement issued on 14 August 1941 that set out American and British goals for the world after the end of World War II, months before the US officially entered the war. The joint statement, later dubbed the Atlantic C ...

was a published statement agreed between the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

and the

United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

. It was intended as the blueprint for the postwar world after

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, and turned out to be the foundation for many of the international agreements that currently shape the world. The

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) is a legal agreement between many countries, whose overall purpose was to promote international trade by reducing or eliminating trade barriers such as tariffs or quotas. According to its p ...

(GATT), the

post-war independence of British and French possessions, and much more are derived from the Atlantic Charter. The Atlantic charter was made to show the goals of the allied powers during World War II. It first started with the United States and Great Britain, and later all the allies would follow the charter. Some goals include access to raw materials, reduction of trade restrictions, and freedom from fear and wants. The name, The Atlantic Charter, came from a newspaper that coined the title. However,

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

would use it, and from then on the Atlantic Charter was the official name. In retaliation, the Axis powers would raise their morale and try to work their way into Great Britain. The Atlantic Charter was a stepping stone into the creation of the United Nations.

On June 5, 1948, at the dedication of the

War Memorial

A war memorial is a building, monument, statue, or other edifice to celebrate a war or victory, or (predominating in modern times) to commemorate those who died or were injured in a war.

Symbolism

Historical usage

It has ...

in

Omaha, Nebraska

Omaha ( ) is the List of cities in Nebraska, most populous city in the U.S. state of Nebraska. It is located in the Midwestern United States along the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's List of United S ...

, U.S. President

Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

remarked, "We must make the United Nations continue to work, and to be a going concern, to see that difficulties between nations may be settled just as we settle difficulties between

States here in the United States. When

Kansas

Kansas ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the west. Kansas is named a ...

and

Colorado

Colorado is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States. It is one of the Mountain states, sharing the Four Corners region with Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah. It is also bordered by Wyoming to the north, Nebraska to the northeast, Kansas ...

fall out over the waters in the

Arkansas River

The Arkansas River is a major tributary of the Mississippi River. It generally flows to the east and southeast as it traverses the U.S. states of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. The river's source basin lies in Colorado, specifically ...

, they don't go to war over it; they go to the

Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all Federal tribunals in the United States, U.S. federal court cases, and over Stat ...

, and the matter is settled in a just and honorable way. There is not a difficulty in the whole world that cannot be settled in exactly the same way in a world court". The cultural moment of the late 1940s was the peak of

World Federalism among Americans.

Founding of the United Nations

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

(1939–1945) resulted in an unprecedented scale of destruction of lives (over 60 million dead, most of them civilians), and the use of

weapons of mass destruction

A weapon of mass destruction (WMD) is a Biological agent, biological, chemical weapon, chemical, Radiological weapon, radiological, nuclear weapon, nuclear, or any other weapon that can kill or significantly harm many people or cause great dam ...

. Some of the acts committed against civilians during the war were on such a massive scale of savagery, they came to be widely considered as

crimes against humanity

Crimes against humanity are certain serious crimes committed as part of a large-scale attack against civilians. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity can be committed during both peace and war and against a state's own nationals as well as ...

itself. As the war's conclusion drew near, many shocked voices called for the establishment of institutions able to permanently prevent deadly international conflicts. This led to the founding of the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

(UN) in 1945, which adopted the

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is an international document adopted by the United Nations General Assembly that enshrines the Human rights, rights and freedoms of all human beings. Drafted by a UN Drafting of the Universal D ...

in 1948.

Many, however, felt that the UN, essentially a forum for discussion and coordination between

sovereign

''Sovereign'' is a title that can be applied to the highest leader in various categories. The word is borrowed from Old French , which is ultimately derived from the Latin">-4; we might wonder whether there's a point at which it's appropriate to ...

governments, was insufficiently empowered for the task. A number of prominent persons, such as

Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein (14 March 187918 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is best known for developing the theory of relativity. Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics. His mass–energy equivalence f ...

,

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

,

Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, and public intellectual. He had influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, and various areas of analytic ...

,

Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2October 186930January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethics, political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful Indian ...

and

Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru (14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat, and statesman who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20th century. Nehru was a pr ...

, called on governments to proceed further by taking gradual steps towards forming an effectual federal world government.

The United Nations main goal is to work on international law, international security, economic development, human rights, social progress, and eventually world peace. The United Nations replaced the League of Nations in 1945, after World War II. Almost every internationally recognized country is in the U.N.; as it contains 193 member states out of the 196 total nations of the world. The United Nations gather regularly in order to solve big problems throughout the world. There are six official languages:

Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

,

Chinese,

English,

French,

Russian and

Spanish.

The United Nations is also financed by some of the wealthiest nations. The flag shows the Earth from a map that shows all of the populated continents.

United Nations Parliamentary Assembly (UNPA)

A

United Nations Parliamentary Assembly (UNPA) is a proposed addition to the

United Nations System that would allow for participation of member nations' legislators and, eventually,

direct election

Direct election is a system of choosing political officeholders in which the voters directly cast ballots for the persons or political party that they want to see elected. The method by which the winner or winners of a direct election are chosen ...

of UN parliament members by citizens worldwide. The idea of a world parliament was raised at the founding of the

League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

in the 1920s and again following the end of World War II in 1945, but remained dormant throughout the

Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

.

In the 1990s and 2000s, the rise of global trade and the power of world organizations that govern it led to calls for a

parliamentary assembly to scrutinize their activity. The

Campaign for a United Nations Parliamentary Assembly was formed in 2007 by

Democracy Without Borders to coordinate pro-UNPA efforts, which as of January 2019 has received the support of over 1,500

Members of Parliament from over 100 countries worldwide, in addition to numerous non-governmental organizations,

Nobel and

Right Livelihood laureates and heads or former heads of state or government and foreign ministers.

Garry Davis

In France, 1948,

Garry Davis began an unauthorized speech calling for a world government from the balcony of the

UN General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; , AGNU or AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as its main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ. Currently in its 79th session, its powers, ...

, until he was dragged away by the guards. Davis

renounced his American citizenship and started a

Registry of World Citizens. On September 4, 1953, Davis announced from the city hall of

Ellsworth, Maine, the formation of the "World Government of World Citizens" based on three "World Laws": One God (or Absolute Value), One World, and One Humanity. Following this declaration, he formed the United World Service Authority in

New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

as the administrative agency of the new government. Davis claimed this agency was mandated by Article 21, Section 3 of the

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is an international document adopted by the United Nations General Assembly that enshrines the Human rights, rights and freedoms of all human beings. Drafted by a UN Drafting of the Universal D ...

. Its first task was to design and begin selling "World Passports", which the organisation argues is legitimatized by on Article 13, Section 2 of the UDHR.

Atomic impact

The world government movement reached its peak of popularity following the

atomic bombing of Japan, especially in the West and Japan. Particularly evident among American scientists, occurred what the editor of the ''

Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists'',

Eugene Rabinowitch, called “the conspiracy to preserve our civilization by scaring men into rationality.” The editor of "

World Constitution,"

Robert Maynard Hutchins

Robert Maynard Hutchins (January 17, 1899 – May 14, 1977) was an American educational philosopher. He was the President of the University of Chicago, 5th president (1929–1945) and chancellor (1945–1951) of the University of Chicago, and ear ...

, saw the atomic bomb as heralding the “good news of damnation” that would frighten people into world state. “Splitting the atom means uniting the world,” begins a 1946 review of literature which came to light following the “bomb’s early light.” People around the world and within the United States shared this sentiment.

Written in June 1945 with "Postscript" added after the atomic attacks,''

The Anatomy of Peace'' stayed on America’s best-seller lists for the next six months. A mordant account of the pathology of nations, it becoming the bible of the world government movement. By 1950, it had appeared in 20 languages and in 24 countries. Drafted on the day of the Hiroshima attack and soon developed into a book, ''Modern Man Is Obsolete'' by one of the prominent

World Federalists,

Norman Cousins, went through fourteen editions, appeared in seven languages, and had an estimated circulation in the United States of seven million.

In late 1945,

Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

scientists founded the

Federation of American Scientists (FAS) and published the first volume of ''Bulletin of Atomic Scientists''. Few months later, they published a book, titled ''

One World or None''. It sold more than 100,000 copies. FAS had reached a peak of 3,000 members in 1946. A substantial number of them, including Einstein, thought the answer lay in world government. The next year, their Bulletin introduced its famous

Doomsday Clock.

Between 1946, when it was founded, and 1950, the

World Movement for World Federal Government grew into a global network with some 156,000 members. By January 1950, Garry Davis’s World Citizens registry, with signers from 78 countries all over the globe, neared the half-million mark. Drafted by Hutchins and his team at the University of Chicago, "World Constitution" was translated into numerous languages and by 1949 reached a worldwide circulation of 200,000 copies. By 1949,

United World Federalists had 46,775 members. The same year, World Government Week was officially proclaimed by the governors of nine states and by the mayors of approximately 50 cities.

By 1950, the British Crusade for World Government had registered some 15,000 supporters and the French "Front Humain des Citoyens du Monde" 18,000. The contemporary polls in the United States and Australia ranged from 42 to 63% supporting world government. The motto "One World or None!” was endorsed by the president of the Australian Aborigines.

Symbolized by the most popular slogan, “One World or None” and by the Doomsday Clock on the front of the ''Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists'', the fear of a nuclear holocaust had played a key part in the world government movement. But, judging from numerous barometers of public sentiment, this fear could not hold. The mood passed. Paradoxically coinciding with the

H-bomb and the Soviet atomic bomb, the terror subsided. In the fall of 1950, when Americans were asked if there was anything in the national or international realm that disturbed them, only 1% spontaneously raised the issue of the atomic bomb. A British civil defense survey in 1951 found that Britons displayed remarkably little knowledge of the atomic bomb or desire to face the issues it raised. A quarter of the women surveyed in the latter poll claimed that they did not know it had been used in Japan.

By the early 1950s, world state movements went out of fashion. Gary Davis returned to the United States and applied for restoration of his American citizenship. Despite massive efforts to frighten humanity into world state, the 1949 World Peace Day celebration in Hiroshima was strangely lighthearted by fireworks, confetti, and the appearance on stage of a “Miss Hiroshima."

World Federalist Movement

The years between the end of World War II and the start of the

Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

—which roughly marked the entrenchment of

Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

polarity—saw a flourishing of the nascent world federalist movement.

's 1943 book ''

One World'' sold over 2 million copies, laying out many of the argument and principles that would inspire global federalism. A contemporaneous work,

Emery Reves' ''

The Anatomy of Peace'' (1945), argued for replacing the UN with a federal world government. The world Federalist movement in the U.S., led by diverse figures such as

Lola Maverick Lloyd,

Grenville Clark,

Norman Cousins, and

Alan Cranston

Alan MacGregor Cranston (June 19, 1914 – December 31, 2000) was an American politician and journalist who served as a United States Senate, United States Senator from California from 1969 to 1993, and as President of the Citizens for Global S ...

, grew larger and more prominent: in 1947, several grassroots organizations merged to form the

United World Federalists—later renamed the World Federalist Association, then

Citizens for Global Solutions —claiming 47,000 members by 1949.

Similar movements concurrently formed in many other countries, culminating in a 1947 meeting in

Montreux, Switzerland

Montreux (, ; ; ) is a Swiss municipality and town on the shoreline of Lake Geneva at the foot of the Alps. It belongs to the Riviera-Pays-d'Enhaut district in the canton of Vaud, having a population of approximately 26,500, with about 85,00 ...

that formed a global coalition called the

World Federalist Movement (WFM). By 1950, the movement claimed 56 member groups in 22 countries, with some 156,000 members.

Convention to propose amendments to the United States Constitution

In 1949, six U.S. states—California, Connecticut, Florida, Maine, New Jersey, and North Carolina—applied for an

Article V convention to propose an amendment "to enable the participation of the United States in a world federal government".

Multiple other state legislatures introduced or debated the same proposal. These resolutions were part of this effort.

During the

81st United States Congress (1949–1951), multiple resolutions were introduced favoring a world federation.

Chicago World Constitution draft

A committee of academics and intellectuals formed by

Robert Maynard Hutchins

Robert Maynard Hutchins (January 17, 1899 – May 14, 1977) was an American educational philosopher. He was the President of the University of Chicago, 5th president (1929–1945) and chancellor (1945–1951) of the University of Chicago, and ear ...

of the

University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, or UChi) is a Private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Its main campus is in the Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood on Chicago's South Side, Chic ...

published a ''Preliminary Draft of a World Constitution'' and from 1947 to 1951 published a magazine edited by the daughter of

Thomas Mann

Paul Thomas Mann ( , ; ; 6 June 1875 – 12 August 1955) was a German novelist, short story writer, social critic, philanthropist, essayist, and the 1929 Nobel Prize in Literature laureate. His highly symbolic and ironic epic novels and novell ...

,

Elisabeth Mann Borgese, which was devoted to world government; its title was ''

Common Cause''.

Albert Einstein and World Constitution

Einstein grew increasingly convinced that the world was veering off course. He arrived at the conclusion that the gravity of the situation demanded more profound actions and the establishment of a "world government" was the only logical solution.

In his "Open Letter to the General Assembly of the United Nations" of October 1947, Einstein emphasized the urgent need for international cooperation and the establishment of a world government. In the year 1948, Einstein invited

United World Federalists, Inc. (UWF) president

Cord Meyer to a meeting of the

Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists (ECAS) and joined UWF as a member of the advisory board.

Einstein and ECAS assisted UEF in fundraising

and provided supporting material. Einstein described

United World Federalists as: "the group nearest to our aspirations".

Einstein and other prominent figures sponsored the

Peoples' World Convention (PWC), which took place in 1950–51 and later continued in the form of

world constituent assemblies in 1968, 1977, 1978–79, and 1991.

This effort was successful in creating a

world constitution and a

Provisional World Government.

drafted by international legal experts during

world constituent assemblies in 1968 and finalized in 1991,

is a framework of a world federalist government. A Provisional World Government consisting of a

Provisional World Parliament (PWP), a transitional international legislative body, operates under the framework of this world constitution.

This parliament convenes to work on global issues, gathering delegates from different countries.

Cold War

In January 1946, US Under Secretary of State,

Sumner Welles, replied to the proponents of world government on the pages of ''Atlantic Monthly''. From the beginning, he could not imagine the Soviet Union participating in a world government upon any other basis than that of a “World Union of Soviet Socialist Republics with the capital . . . in Moscow.” As Welles expected, the Soviets reacted negatively on the idea of world state. Soviet Foreign Minister,

Vyacheslav Molotov, warned of “world domination by way of… world government.” The Soviet media launched a shrill attack. Having exaggerated atomic destructiveness, the Soviets claimed, the American scientists pushed their “florid talk about a world state” which is a “frank plea for American imperialism.” The world state theory was described as a cover of the imperialist “aggressive plans” of “war-mongers” and is the “fascist Anglo-Saxon doctrine,” following the model of the “Hitlerite racialists,” exalting the Anglo-Saxons as a “superior race,” and promoting the “American age of world atomic empire.” United World Federalists, in the Soviet view, wished “disarmed nations throughout the world under the surveillance of armed American police,” a plan copied from Hitler’s “

New Order. ” Einstein was attacked as a proponent of “world domination” and the West was condemned for “reactionary Einsteinism.” UWF leaders, Cord Meyer Jr. and Vernon Nash, were labeled, respectively, a “cosmopolitan gangster” and a “cosmopolitan Judas.” After Garry Davis turned up in Paris, he was portrayed as a “debauched American maniac” who brought from America the idea of world government.

Having found the Soviets less cooperative than expected, the Western scientific community abandoned the debate how to create world government and engaged in the creation of the

hydrogen bomb

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H-bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lo ...

. By 1950, the

Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

began to dominate international politics and the UN Security Council became effectively paralyzed by its permanent members' ability to exercise

veto power. The

United Nations Security Council Resolution 82 and

83 backed the defense of South Korea, although the Soviets were then boycotting meetings in protest.

While enthusiasm for multinational federalism in Europe incrementally led, over the following decades, to the formation of the

European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are Geography of the European Union, located primarily in Europe. The u ...

, the Cold War eliminated the prospects of any progress towards federation with a more global scope. Global integration became stagnant during the Cold War, and the conflict became the driver behind one-third of all wars during the period. The idea of world government all but disappeared from wide public discourse.

Post–Cold War

As the Cold War dwindled in 1991, interest in a federal world government was renewed. When the conflict ended by 1992, without the external assistance, many proxy wars petered out or ended by negotiated settlements. This kicked off a period in the 1990s of unprecedented international activism and an expansion of international institutions. According to the ''

Human Security Report 2005'', this was the first effective functioning of the United Nations as it was designed to operate.

The most visible achievement of the world federalism movement during the 1990s is the

Rome Statute of 1998, which led to the establishment of the

International Criminal Court

The International Criminal Court (ICC) is an intergovernmental organization and International court, international tribunal seated in The Hague, Netherlands. It is the first and only permanent international court with jurisdiction to prosecute ...

in 2002. In

Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

, progress towards forming a federal union of European states gained much momentum, starting in 1952 as a trade deal between the German and French people led, in 1992, to the

Maastricht Treaty

The Treaty on European Union, commonly known as the Maastricht Treaty, is the foundation treaty of the European Union (EU). Concluded in 1992 between the then-twelve Member state of the European Union, member states of the European Communities, ...

that established the name and enlarged the agreement that the European Union is based upon. The EU expanded (1995, 2004, 2007, 2013) to encompass, in 2013, over half a billion people in 28 member states (27 after

Brexit

Brexit (, a portmanteau of "Britain" and "Exit") was the Withdrawal from the European Union, withdrawal of the United Kingdom (UK) from the European Union (EU).

Brexit officially took place at 23:00 GMT on 31 January 2020 (00:00 1 February ...

). Following the EU's example, other

supranational union

A supranational union is a type of international organization and political union that is empowered to directly exercise some of the powers and functions otherwise reserved to State (polity), states. A supranational organization involves a g ...

s were established, including the

African Union

The African Union (AU) is a continental union of 55 member states located on the continent of Africa. The AU was announced in the Sirte Declaration in Sirte, Libya, on 9 September 1999, calling for the establishment of the African Union. The b ...

in 2002, the

Union of South American Nations in 2008, and the

Eurasian Economic Union

The Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU or EEU)EAEU is the acronym used on thorganisation's website However, many media outlets use the acronym EEU. is an economic union of five post-Soviet states located in Eurasia. The EAEU has an integrated single ...

in 2015.

Current system of global governance

, there is no functioning global international

military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. Militaries are typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with their members identifiable by a d ...

,

executive,

legislature

A legislature (, ) is a deliberative assembly with the legal authority to make laws for a political entity such as a country, nation or city on behalf of the people therein. They are often contrasted with the executive and judicial power ...

,

judiciary

The judiciary (also known as the judicial system, judicature, judicial branch, judiciative branch, and court or judiciary system) is the system of courts that adjudicates legal disputes/disagreements and interprets, defends, and applies the law ...

, or

constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these pri ...

with jurisdiction over the entire planet.

No world government

The world is divided geographically and demographically into mutually exclusive territories and political structures called

states which are

independent and

sovereign

''Sovereign'' is a title that can be applied to the highest leader in various categories. The word is borrowed from Old French , which is ultimately derived from the Latin">-4; we might wonder whether there's a point at which it's appropriate to ...

in most cases. There are numerous bodies, institutions, unions, coalitions, agreements and contracts between these units of

authority

Authority is commonly understood as the legitimate power of a person or group of other people.

In a civil state, ''authority'' may be practiced by legislative, executive, and judicial branches of government,''The New Fontana Dictionary of M ...

, but, except in cases where one nation is under

military occupation

Military occupation, also called belligerent occupation or simply occupation, is temporary hostile control exerted by a ruling power's military apparatus over a sovereign territory that is outside of the legal boundaries of that ruling pow ...

by another, ''all'' such arrangements depend on the continued consent of the participant nations. Countries that violate or do not enforce international laws may be subject to penalty or coercion, often in the form of economic limitations such as

embargos by cooperating countries, even if the violating country is not part of the United Nations. In this way a country's cooperation in international affairs is voluntary, but non-cooperation still has

diplomatic consequences.

International criminal courts

A functioning system of

International law

International law, also known as public international law and the law of nations, is the set of Rule of law, rules, norms, Customary law, legal customs and standards that State (polity), states and other actors feel an obligation to, and generall ...

encompasses international treaties, customs and globally accepted legal principles. With the exceptions of cases brought before the

ICC and

ICJ, the laws are interpreted by national courts. Many violations of treaty or customary law obligations are overlooked.

International Criminal Court

The International Criminal Court (ICC) is an intergovernmental organization and International court, international tribunal seated in The Hague, Netherlands. It is the first and only permanent international court with jurisdiction to prosecute ...

(ICC) was a relatively recent development in international law, it is the first permanent international criminal court established to ensure that the gravest international crimes (

war crime

A war crime is a violation of the laws of war that gives rise to individual criminal responsibility for actions by combatants in action, such as intentionally killing civilians or intentionally killing prisoners of war, torture, taking hostage ...

s,

genocide

Genocide is violence that targets individuals because of their membership of a group and aims at the destruction of a people. Raphael Lemkin, who first coined the term, defined genocide as "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group" by ...

, other

crimes against humanity

Crimes against humanity are certain serious crimes committed as part of a large-scale attack against civilians. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity can be committed during both peace and war and against a state's own nationals as well as ...

, etc.) do not go unpunished. The

Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court

The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court is the treaty that established the International Criminal Court (ICC). It was adopted at a diplomatic conference in Rome, Italy on 17 July 1998Michael P. Scharf (August 1998)''Results of the R ...

establishing the ICC and its jurisdiction was signed by 139 national governments, of which 100 ratified it by October 2005.

Inter-governmental organizations

The

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

(UN) is the primary formal organization coordinating activities between states on a global scale and the only inter-governmental organization with near-universal membership (193 governments). In addition to the main organs and various humanitarian programs and commissions of the UN itself, there are about 20 functional organizations affiliated with the

United Nations Economic and Social Council

The United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) is one of six principal organs of the United Nations, responsible for coordinating the economic and social fields of the organization, specifically in regards to the fifteen specialized ...

(ECOSOC), such as the

World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a list of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations which coordinates responses to international public health issues and emergencies. It is headquartered in Gen ...

, the

International Labour Organization

The International Labour Organization (ILO) is a United Nations agency whose mandate is to advance social and economic justice by setting international labour standards. Founded in October 1919 under the League of Nations, it is one of the firs ...

, and

International Telecommunication Union

The International Telecommunication Union (ITU)In the other common languages of the ITU:

*

* is a list of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for many matters related to information ...

. Of particular interest politically are the

World Bank

The World Bank is an international financial institution that provides loans and Grant (money), grants to the governments of Least developed countries, low- and Developing country, middle-income countries for the purposes of economic development ...

, the

International Monetary Fund

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is a major financial agency of the United Nations, and an international financial institution funded by 191 member countries, with headquarters in Washington, D.C. It is regarded as the global lender of las ...

and the

World Trade Organization

The World Trade Organization (WTO) is an intergovernmental organization headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland that regulates and facilitates international trade. Governments use the organization to establish, revise, and enforce the rules that g ...

.

International militaries

Militarily,

the UN deploys peacekeeping forces, usually to build and maintain post-conflict peace and stability. When a more aggressive international military action is undertaken, either ''

ad hoc

''Ad hoc'' is a List of Latin phrases, Latin phrase meaning literally for this. In English language, English, it typically signifies a solution designed for a specific purpose, problem, or task rather than a Generalization, generalized solution ...

'' coalitions (for example, the

Multi-National Force – Iraq) or regional

military alliance

A military alliance is a formal Alliance, agreement between nations that specifies mutual obligations regarding national security. In the event a nation is attacked, members of the alliance are often obligated to come to their defense regardless ...

s (for example,

NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

) are used.

Mostly overlooked in the academic research but notable among policy-makers, there exists a US-led “Global Network of Allies and Partners.” The network has its origins in the early Cold War and was called by

NSC 162/2 “the Coalition.” It included NATO and other US allies. Spatially, it coincides with the

Zone of peace.

Clarence Streit and the Union Now movement rode the coattails of NATO’s formation to a renaissance of popular support in 1949 and 1950. Two decades later, one of the architects of NATO,

Dean Acheson

Dean Gooderham Acheson ( ; April 11, 1893October 12, 1971) was an American politician and lawyer. As the 51st United States Secretary of State, U.S. Secretary of State, he set the foreign policy of the Harry S. Truman administration from 1949 to ...

, contemplating the achievement felt as he was “

present at the creation.”

''

Union Now'' of Streit called for federation of 15 contemporary democracies (English-speaking and west European). He counted that their combined power would be enough to ensure international stability. His federation has not come true but eventually all the countries he named and many others joined what the NSC called “the Coalition.” After the Cold War, US Secretary of Defense,

Dick Cheney

Richard Bruce Cheney ( ; born January 30, 1941) is an American former politician and businessman who served as the 46th vice president of the United States from 2001 to 2009 under President George W. Bush. He has been called vice presidency o ...

, assured that the United States will maintain its alliances in Europe, the Middle East, East Asia, Pacific, Latin America and elsewhere. “Remarkably, commented Max Ostrovsky, not much is left for elsewhere.”

In 2006, Bradley A. Thayer counted 84 allies worldwide. In 2018, Ostrovsky estimated that most of the UN members belong to “the Coalition,” perhaps exceeding 100 in number, and almost all economically developed are included. Unrivaled in the history of nations, the “Coalition” comprises 70% of both global defense spending and global nominal gross product, with all adversaries combining for less than 15% of global defense spending.

Karl Deutsch was one of the earliest observers to perceive the evolving “Coalition.” Deutsch called it “

pluralistic security-community.” This community does not function on

balance of power but as a unipolar organization with a strong core.

Paraphrasing Streit’s ''Union Now'', Ostrovsky titled a chapter “Coalition Now.” Its bottom line says that some structural factors forced most states, including almost all developed states, to surrender their strategic sovereignty and form a unipolar “Coalition.” While all these states are nominally sovereign, in strategic field such is not the case. “Strategically, the world is one.”