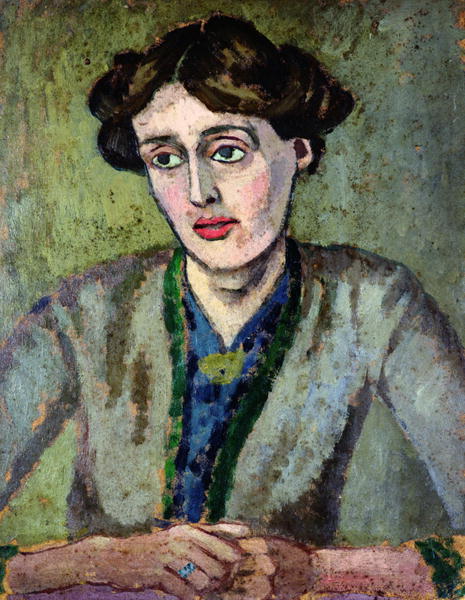

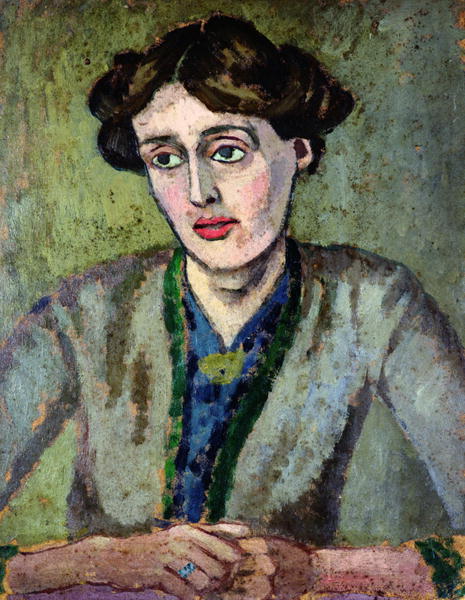

Adeline Virginia Woolf (; ; 25 January 1882 28 March 1941) was an English writer and one of the most influential 20th-century

modernist

Modernism was an early 20th-century movement in literature, visual arts, and music that emphasized experimentation, abstraction, and Subjectivity and objectivity (philosophy), subjective experience. Philosophy, politics, architecture, and soc ...

authors. She helped to pioneer the use of

stream of consciousness

In literary criticism, stream of consciousness is a narrative mode or method that attempts "to depict the multitudinous thoughts and feelings which pass through the mind" of a narrator. It is usually in the form of an interior monologue which ...

narration as a literary device.

Virginia Woolf was born in

South Kensington

South Kensington is a district at the West End of Central London in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Historically it settled on part of the scattered Middlesex village of Brompton. Its name was supplanted with the advent of the ra ...

,

London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, into an affluent and intellectual family as the seventh child of

Julia Prinsep Jackson and

Leslie Stephen

Sir Leslie Stephen (28 November 1832 – 22 February 1904) was an English author, critic, historian, biographer, mountaineer, and an Ethical Culture, Ethical movement activist. He was also the father of Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell and the ...

. She grew up in a blended household of eight children, including her sister, the painter

Vanessa Bell

Vanessa Bell (née Stephen; 30 May 1879 – 7 April 1961) was an English painter and interior designer, a member of the Bloomsbury Group and the sister of Virginia Woolf (née Stephen).

Early life and education

Vanessa Stephen was the eld ...

. Educated at home in English classics and

Victorian literature

Victorian era, Victorian literature is English literature during the reign of Queen Victoria (1837–1901). In the Victorian era, the novel became the leading literary genre in English. English writing from this era reflects the major transform ...

, Woolf later attended

King’s College London

King's College London (informally King's or KCL) is a public university, public research university in London, England. King's was established by royal charter in 1829 under the patronage of George IV of the United Kingdom, King George IV ...

, where she studied

classics

Classics, also classical studies or Ancient Greek and Roman studies, is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, ''classics'' traditionally refers to the study of Ancient Greek literature, Ancient Greek and Roman literature and ...

and

history

History is the systematic study of the past, focusing primarily on the Human history, human past. As an academic discipline, it analyses and interprets evidence to construct narratives about what happened and explain why it happened. Some t ...

and encountered early advocates for

women’s rights

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countries ...

and education.

After the death of her father in 1904, Woolf and her family moved to the bohemian

Bloomsbury

Bloomsbury is a district in the West End of London, part of the London Borough of Camden in England. It is considered a fashionable residential area, and is the location of numerous cultural institution, cultural, intellectual, and educational ...

district, where she became a founding member of the influential

Bloomsbury Group

The Bloomsbury Group was a group of associated British writers, intellectuals, philosophers and artists in the early 20th century. Among the people involved in the group were Virginia Woolf, John Maynard Keynes, E. M. Forster, Vanessa Bell, a ...

. She married

Leonard Woolf

Leonard Sidney Woolf (; – ) was a British List of political theorists, political theorist, author, publisher, and civil servant. He was married to author Virginia Woolf. As a member of the Labour Party (UK), Labour Party and the Fabian Socie ...

in 1912, and together they established the

Hogarth Press

The Hogarth Press is a book publishing Imprint (trade name), imprint of Penguin Random House that was founded as an independent company in 1917 by British authors Leonard Woolf and Virginia Woolf. It was named after their house in London Boro ...

in 1917, which published much of her work. They eventually settled in

Sussex

Sussex (Help:IPA/English, /ˈsʌsɪks/; from the Old English ''Sūþseaxe''; lit. 'South Saxons'; 'Sussex') is an area within South East England that was historically a kingdom of Sussex, kingdom and, later, a Historic counties of England, ...

in 1940, maintaining their involvement in literary circles throughout their lives.

Woolf began publishing professionally in 1900 and rose to prominence during the interwar period with novels like ''

Mrs Dalloway

''Mrs Dalloway'' is a novel by Virginia Woolf published on 14 May 1925. It details a day in the life of Clarissa Dalloway, a fictional upper-class woman in post-First World War England.

The working title of ''Mrs Dalloway'' was ''The Hours ...

'' (1925), ''

To the Lighthouse

''To the Lighthouse'' is a 1927 novel by Virginia Woolf. The novel centres on the Ramsay family and their visits to the Isle of Skye in Scotland between 1910 and 1920.

Following and extending the tradition of modernist novelists like Marcel P ...

'' (1927), and ''

Orlando

Orlando commonly refers to:

* Orlando, Florida, a city in the United States

Orlando may also refer to:

People

* Orlando (given name), a masculine name, includes a list of people with the name

* Orlando (surname), includes a list of people wit ...

'' (1928), as well as the

feminist

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideology, ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social gender equality, equality of the sexes. Feminism holds the position that modern soci ...

essay ''

A Room of One’s Own'' (1929). Her work became central to 1970s

feminist criticism

Feminist literary criticism is literary criticism informed by feminist theory, or more broadly, by the politics of feminism. It uses the principles and ideology of feminism to critique the language of literature. This school of thought seeks to an ...

and remains influential worldwide, having been translated into over 50 languages. Woolf’s legacy endures through extensive scholarship, cultural portrayals, and tributes such as memorials, societies, and university buildings bearing her name.

Life

Early life

Virginia Woolf was born Adeline Virginia Stephen on 25 January 1882, in

South Kensington

South Kensington is a district at the West End of Central London in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Historically it settled on part of the scattered Middlesex village of Brompton. Its name was supplanted with the advent of the ra ...

, London, to

Julia (née Jackson) and

Sir Leslie Stephen. Her father was a writer, historian, essayist, biographer, and mountaineer, while her mother was a noted philanthropist. Woolf's maternal relatives include

Julia Margaret Cameron

Julia Margaret Cameron (; 11 June 1815 – 26 January 1879) was an English photographer who is considered one of the most important portraitists of the 19th century. She is known for her Soft focus, soft-focus close-ups of famous Victorian era, ...

, a celebrated photographer, and

Lady Henry Somerset

Isabella Caroline Somerset, Lady Henry Somerset (née Somers-Cocks; 3 August 1851 – 12 March 1921), styled Lady Isabella Somers-Cocks from 5 October 1852 to 6 February 1872, was a British philanthropist, temperance movement, temperance leader ...

, a campaigner for women's rights. Originally named after her aunt Adeline, Woolf did not use her first name due to her aunt's recent death.

Both Virginia's parents had children from previous marriages. Julia's first marriage, to barrister

Herbert Duckworth, produced three children:

George

George may refer to:

Names

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

People

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Papagheorghe, also known as Jorge / GEØRGE

* George, stage name of Gior ...

, Stella, and

Gerald

Gerald is a masculine given name derived from the Germanic languages prefix ''ger-'' ("spear") and suffix ''-wald'' ("rule"). Gerald is a Norman French variant of the Germanic name. An Old English equivalent name was Garweald, the likely original ...

. Leslie's first marriage, to Minny Thackeray, daughter of

William Makepeace Thackeray

William Makepeace Thackeray ( ; 18 July 1811 – 24 December 1863) was an English novelist and illustrator. He is known for his Satire, satirical works, particularly his 1847–1848 novel ''Vanity Fair (novel), Vanity Fair'', a panoramic portra ...

, resulted in one daughter, Laura. Leslie and Julia Stephen had four children together:

Vanessa Vanessa may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Vanessa'' (Millais painting), an 1868 painting by Pre-Raphaelite artist John Everett Millais

* ''Vanessa'', a 1933 novel by Hugh Walpole

* ''Vanessa'', a 1952 instrumental song written by Bernie W ...

,

Thoby, Virginia, and

Adrian

Adrian is a form of the Latin given name Adrianus or Hadrianus. Its ultimate origin is most likely via the former river Adria from the Venetic and Illyrian word ''adur'', meaning "sea" or "water".

The Adria was until the 8th century BC the ma ...

.

Virginia showed an early affinity for writing. By the age of five, she was writing letters, and her fascination with books helped form a bond with her father. From the age of 10, she began an illustrated family newspaper, the ''Hyde Park Gate News'', chronicling life and events within the Stephen family, and modelled on the popular magazine ''

Tit-Bits

''Tit-Bits from all the interesting Books and Newspapers of the World'', more commonly known as ''Tit-Bits'' and later as ''Titbits'', was a British weekly magazine founded by George Newnes, a founding figure in popular journalism, on 22 Octo ...

''. Virginia would run the ''Hyde Park Gate News'' until 1895. In 1897, Virginia began her first diary, which she kept for the next twelve years.

Talland House

In the spring of 1882, Leslie rented a large white house in

St Ives, Cornwall

St Ives (, meaning "Ia of Cornwall, St Ia's cove") is a seaside town, civil parish and port in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. The town lies north of Penzance and west of Camborne on the coast of the Celtic Sea. In former times, it was comm ...

. The family spent three months each summer there for the first 13 years of Virginia's life. Despite its limited amenities, the house's main attraction was the view of Porthminster Bay overlooking the

Godrevy Lighthouse

Godrevy Lighthouse () was built in 1858–1859 on Godrevy Island in St Ives Bay, Cornwall. Standing approximately off Godrevy Head, it marks the Stones reef, which has been a hazard to shipping for centuries.

History

The Stones claimed m ...

. The happy summers spent at Talland House would later influence Woolf's novels ''

Jacob's Room

''Jacob's Room'' is the third novel by Virginia Woolf, first published on 26 October 1922.

The novel centres, in a very ambiguous way, around the life story of the protagonist Jacob Flanders and is presented almost entirely through the impressi ...

'', ''

To the Lighthouse

''To the Lighthouse'' is a 1927 novel by Virginia Woolf. The novel centres on the Ramsay family and their visits to the Isle of Skye in Scotland between 1910 and 1920.

Following and extending the tradition of modernist novelists like Marcel P ...

'' and ''

The Waves

''The Waves'' is a 1931 novel by English novelist Virginia Woolf. It is critically regarded as her most experimental work, consisting of ambiguous and cryptic soliloquies spoken mainly by six characters: Bernard, Susan, Rhoda, Neville, Jinny an ...

''.

At both Talland House and her family home, the family engaged with many literary and artistic figures. Frequent guests included literary figures such as

Henry James

Henry James ( – ) was an American-British author. He is regarded as a key transitional figure between literary realism and literary modernism, and is considered by many to be among the greatest novelists in the English language. He was the ...

,

George Meredith

George Meredith (12 February 1828 – 18 May 1909) was an English novelist and poet of the Victorian era. At first, his focus was poetry, influenced by John Keats among others, but Meredith gradually established a reputation as a novelist. '' ...

, and

James Russell Lowell

James Russell Lowell (; February 22, 1819 – August 12, 1891) was an American Romantic poet, critic, editor, and diplomat. He is associated with the fireside poets, a group of New England writers who were among the first American poets to r ...

. The family did not return after 1894; a hotel was constructed in front of the house which blocked the sea view, and Julia Stephen died in May the following year.

Sexual abuse

In the 1939 essay "A Sketch of the Past", Woolf first disclosed that she had experienced sexual abuse by Gerald Duckworth during childhood. There is speculation that this contributed to her mental health issues later in life. There are also suggestions of sexual impropriety from George Duckworth during the period that he was caring for the Stephen sisters when they were teenagers.

Adolescence

Her mother's death precipitated what Virginia later identified as her first "breakdown"for months afterwards she was nervous and agitated, and she wrote very little for the subsequent two years.

Stella Duckworth took on a parental role in the household. She married in April 1897 but remained closely involved with the Stephens, moving to a house very close to the Stephens to continue to support the family. However, she fell ill on her honeymoon and died in July of that same year. After Stella's death, George Duckworth took on the role of head of the household, and sought to

bring Vanessa and Virginia into society.

[ However, this experience did not resonate with either sister. Virginia later reflected on this societal expectation, stating: "Society in those days was a very competent, perfectly complacent, ruthless machine. A girl had no chance against its fangs. No other desiressay to paint, or to writecould be taken seriously." For Virginia, writing remained a priority.][ She began a new diary at the start of 1897 and filled notebooks with fragments and literary sketches.

In February 1904 Leslie Stephen died, which caused Virginia to suffer another period of mental instability, lasting from April to September. During this time she experienced a severe psychological crisis, which led to at least one suicide attempt. Woolf later described the period between 1897 and 1904 as "the seven unhappy years".

]

Education

As was common at the time, Virginia's mother did not believe in formal education for her daughters. Instead, Virginia was educated in a piecemeal fashion by her parents. She also received piano lessons.

As was common at the time, Virginia's mother did not believe in formal education for her daughters. Instead, Virginia was educated in a piecemeal fashion by her parents. She also received piano lessons.[ Virginia had unrestricted access to her father's vast library, exposing her to much of the literary canon.][ This resulted in a greater depth of reading than any of her Cambridge contemporaries.]Clara Pater

Clara Ann Pater (''bap.'' 1841–1910) was an English scholar, a tutor, and a pioneer and early reformer of women's education.

Pater contributed to the growing movement for educational equality among women of the Victorian era as they began to gr ...

, who was instrumental to her classical education, while another, Janet Case

Janet Elizabeth Case (1863–1937) was a British classical scholar, tutor of ancient Greek, and women's rights advocate.

Early life and education

Case was born in Hampstead, London, in 1863, to William Arthur Case and Sarah Wolridge Stansfeld; s ...

, became a lasting friend and introduced her to the suffrage movement

Women's suffrage is the women's rights, right of women to Suffrage, vote in elections. Several instances occurred in recent centuries where women were selectively given, then stripped of, the right to vote. In Sweden, conditional women's suffra ...

. Virginia also attended lectures at the King's College Ladies' Department.

Although Virginia could not attend Cambridge, she was profoundly influenced by her brother Thoby's experiences there. When Thoby went to Trinity in 1899 he became part of an intellectual circle of young men, including Clive Bell

Arthur Clive Heward Bell (16 September 1881 – 17 September 1964) was an English art critic, associated with formalism and the Bloomsbury Group. He developed the art theory known as significant form.

Biography Early life and education

Bell ...

, Lytton Strachey

Giles Lytton Strachey (; 1 March 1880 – 21 January 1932) was an English writer and critic. A founding member of the Bloomsbury Group and author of ''Eminent Victorians'', he established a new form of biography in which psychology, psychologic ...

, Leonard Woolf

Leonard Sidney Woolf (; – ) was a British List of political theorists, political theorist, author, publisher, and civil servant. He was married to author Virginia Woolf. As a member of the Labour Party (UK), Labour Party and the Fabian Socie ...

(whom Virginia would later marry), and Saxon Sydney-Turner

Saxon Arnoll Sydney-TurnerMiddle name sometimes mistakenly spelled Arnold, but see A Cambridge Alumni Database: https://venn.lib.cam.ac.uk/cgi-bin/search-2018.pl?sur=sydney-turner&suro=w&fir=saxon&firo=c&cit=&cito=c&c=all&z=all&tex=&sye=1898&eye= ...

. He introduced his sisters to this circle at the Trinity May Ball in 1900. This circle formed a reading group that they named the Midnight Society, to which the Stephen sisters would later be invited.[

]

Bloomsbury (1904–1912)

Gordon Square

After their father's death, Vanessa and Adrian Stephen decided to sell their family home in South Kensington and move to

After their father's death, Vanessa and Adrian Stephen decided to sell their family home in South Kensington and move to Bloomsbury

Bloomsbury is a district in the West End of London, part of the London Borough of Camden in England. It is considered a fashionable residential area, and is the location of numerous cultural institution, cultural, intellectual, and educational ...

, a more affordable area. The Duckworth brothers did not join the Stephens in their new home; Gerald did not wish to, and George married and moved with his wife during the preparations. Virginia lived in the house for brief periods in the autumnshe was sent away to Cambridge and Yorkshire for her health. She eventually settled there permanently in December 1904.

From March 1905 the Stephens hosted gatherings with Thoby's intellectual friends at their home. Their social gatherings, referred to as "Thursday evenings", aimed to recreate the atmosphere at Trinity College. This circle formed the core of the intellectual circle of writers and artists known as the Bloomsbury Group

The Bloomsbury Group was a group of associated British writers, intellectuals, philosophers and artists in the early 20th century. Among the people involved in the group were Virginia Woolf, John Maynard Keynes, E. M. Forster, Vanessa Bell, a ...

. Later, it would include John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes ( ; 5 June 1883 – 21 April 1946), was an English economist and philosopher whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments. Originall ...

, Duncan Grant

Duncan James Corrowr Grant (21 January 1885 – 8 May 1978) was a Scottish painter and designer of textiles, pottery, theatre sets, and costumes. He was a member of the Bloomsbury Group.

His father was Bartle Grant, a "poverty-stricken" major ...

, E. M. Forster

Edward Morgan Forster (1 January 1879 – 7 June 1970) was an English author. He is best known for his novels, particularly '' A Room with a View'' (1908), ''Howards End'' (1910) and '' A Passage to India'' (1924). He also wrote numerous shor ...

, Roger Fry

Roger Eliot Fry (14 December 1866 – 9 September 1934) was an English painter and art critic, critic, and a member of the Bloomsbury Group. Establishing his reputation as a scholar of the Old Masters, he became an advocate of more recent ...

, and David Garnett

David Garnett (9 March 1892 – 17 February 1981) was an English writer and publisher. As a child, he had a cloak made of rabbit skin and thus received the nickname "Bunny", by which he was known to friends and intimates all his life.

Early ...

. The group went on to gain notoriety for the ''Dreadnought'' hoax, in which they posed as a royal Abyssinian entourage. Among them, Virginia assumed the role of Prince Mendax.Morley College

Morley College is a specialist adult education and further education college in London, England. The college has three main campuses, one in Waterloo on the South Bank, and two in West London namely in North Kensington and in Chelsea, the ...

and continued intermittently for the next two years. Her experience here would later influence themes of class and education in her novel ''Mrs Dalloway

''Mrs Dalloway'' is a novel by Virginia Woolf published on 14 May 1925. It details a day in the life of Clarissa Dalloway, a fictional upper-class woman in post-First World War England.

The working title of ''Mrs Dalloway'' was ''The Hours ...

''. She also made some money from reviews, including some published in church paper ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

'' and the ''National Review

''National Review'' is an American conservative editorial magazine, focusing on news and commentary pieces on political, social, and cultural affairs. The magazine was founded by William F. Buckley Jr. in 1955. Its editor-in-chief is Rich L ...

'', capitalising on her father's literary reputation in order to earn commissions.

Vanessa added another event to their calendar with the "Friday Club", dedicated to the discussion of the fine arts. This gathering attracted some new members into their circle, including Henry Lamb

Henry Taylor Lamb (21 June 1883 – 8 October 1960) was an Australian-born British painter. A follower of Augustus John, Lamb was a founder member of the Camden Town Group in 1911 and of the London Group in 1913.

Early life

Henry Lamb was bo ...

, Gwen Darwin, and Katherine Laird ("Ka") Cox. Cox was to become Virginia's intimate friend. These new members brought the Bloomsbury Group into contact with another, slightly younger, group of Cambridge intellectuals whom Virginia would refer to as the "Neo-Pagans". The Friday Club continued until 1912 or 1913.

In the autumn of 1906, the siblings travelled to Greece and Turkey with Violet Dickinson. During the trip both Violet and Thoby contracted typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known simply as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella enterica'' serotype Typhi bacteria, also called ''Salmonella'' Typhi. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often th ...

, which led to Thoby's death on 20 November of that year. Two days after Thoby's death, Vanessa accepted a previous proposal of marriage from Clive Bell. As a couple, their interest in avant-garde

In the arts and literature, the term ''avant-garde'' ( meaning or ) identifies an experimental genre or work of art, and the artist who created it, which usually is aesthetically innovative, whilst initially being ideologically unacceptable ...

art would have an important influence on Virginia's further development as an author.

Fitzroy Square and Brunswick Square

After Vanessa's marriage, Virginia and Adrian moved into Fitzroy Square

Fitzroy Square is a Georgian architecture, Georgian garden square, square in London, England. It is the only one in the central London area known as Fitzrovia.

The square is one of the area's main features, this once led to the surrounding di ...

, still very close to Gordon Square. The new house had previously been occupied by George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from the 188 ...

, and the area had been populated by artists since the previous century. Virginia resented the wealth that Vanessa's marriage had given her; Virginia and Adrian lived more humbly by comparison.

The siblings resumed the Thursday Club at their new home. During this period, the Bloomsbury group increasingly explored progressive ideas, with open discussions of sexuality. Virginia, however, appears not to have shown interest in practising the group's ideologies, finding an outlet for her sexual desires only in writing. Around this time she began work on her first novel, ''Melymbrosia'', which eventually became ''The Voyage Out

''The Voyage Out'' is the first novel by Virginia Woolf, published in 1915 by Duckworth.

Development and first draft

Woolf began work on ''The Voyage Out'' by 1910 (perhaps as early as 1907) and had finished an early draft by 1912. The novel ...

'' (1915).

In November 1911 Virginia and Adrian moved to a larger house in Brunswick Square

Brunswick Square is a public garden and ancillary streets along two of its sides in Bloomsbury, in the London Borough of Camden. It is overlooked by the School of Pharmacy and the Foundling Museum to the north; the Brunswick Centre to the we ...

, and invited John Maynard Keynes, Duncan Grant and Leonard Woolf to become lodgers there. Virginia saw it as a new opportunity: "We are going to try all kinds of experiments", she told Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Violet Anne Morrell (née Cavendish-Bentinck; 16 June 1873 – 21 April 1938) was an English Aristocracy (class), aristocrat and society hostess. Her patronage was influential in artistic and intellectual circles, where she befri ...

.

Asham House (1911–1919)

During the later Bloomsbury years, Virginia travelled frequently with friends and family, to Dorset, Cornwall, and farther afield to Paris, Italy and Bayreuth. These trips were intended to prevent her from suffering exhaustion due to extended periods in London. The question arose of her needing a quiet country retreat close to London to support her still-fragile mental health. In the winter of 1910 she and Adrian stayed at

During the later Bloomsbury years, Virginia travelled frequently with friends and family, to Dorset, Cornwall, and farther afield to Paris, Italy and Bayreuth. These trips were intended to prevent her from suffering exhaustion due to extended periods in London. The question arose of her needing a quiet country retreat close to London to support her still-fragile mental health. In the winter of 1910 she and Adrian stayed at Lewes

Lewes () is the county town of East Sussex, England. The town is the administrative centre of the wider Lewes (district), district of the same name. It lies on the River Ouse, Sussex, River Ouse at the point where the river cuts through the Sou ...

and started exploring Sussex's surrounding area. She soon found a property in nearby Firle

Firle (; Sussex dialect: ''Furrel'' ) is a village and civil parish in the Lewes (district), Lewes district of East Sussex, England. Firle refers to an Old English word ''fierol'' meaning overgrown with oak.

Although the original division of ...

, which she named "Little Talland House"; she maintained a relationship with that region for the rest of her life, spending her time either in Sussex or London.

In September 1911 she and Leonard Woolf found Asham House nearby, and she and Vanessa took a joint lease on it. Located at the end of a tree-lined road, the house was in a Regency-Gothic style, "flat, pale, serene, yellow-washed", remote, without electricity or water and allegedly haunted. The sisters had two housewarming parties in January 1912.

Virginia recorded the weekends and holidays she spent there in her Asham Diary, part of which was later published as ''A Writer's Diary'' in 1953. Creatively, ''The Voyage Out

''The Voyage Out'' is the first novel by Virginia Woolf, published in 1915 by Duckworth.

Development and first draft

Woolf began work on ''The Voyage Out'' by 1910 (perhaps as early as 1907) and had finished an early draft by 1912. The novel ...

'' was completed there, as was much of '' Night and Day''. The house itself inspired the short story "A Haunted House", published in ''A Haunted House and Other Short Stories

''A Haunted House'' is a 1944 collection of 18 short stories by Virginia Woolf. It was produced by her husband Leonard Woolf after her death although in the foreword he states that they had discussed its production together.

* The first six sto ...

''. Asham provided Virginia with much-needed relief from the London's fast-paced life and was where she found happiness that she expressed in her diary on 5 May 1919: "Oh, but how happy we've been at Asheham! It was a most melodious time. Everything went so freely; – but I can't analyse all the sources of my joy".

While at Asham, in 1916 Leonard and Virginia found a farmhouse about four miles away that they thought would be ideal for her sister. Eventually, Vanessa visited to inspect it, and took possession in October of that year, establishing it as a summer home for her family. The Charleston Farmhouse

Charleston, in East Sussex, is a property associated with the Bloomsbury group, that is open to the public. It was the country home of Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant and is an example of their decorative style within a domestic context, represe ...

was to become the summer gathering place for the Bloomsbury Group.

Marriage and war (1912–1920)

Leonard Woolf

Leonard Sidney Woolf (; – ) was a British List of political theorists, political theorist, author, publisher, and civil servant. He was married to author Virginia Woolf. As a member of the Labour Party (UK), Labour Party and the Fabian Socie ...

was one of Thoby Stephen's friends at Trinity College, Cambridge, and had encountered the Stephen sisters in Thoby's rooms while visiting for May Week

May Week is the name used in the University of Cambridge to refer to a period at the end of the academic year. Originally May Week took place in the week during May before year-end exams began. Nowadays, May Week takes place in June after exa ...

between 1899 and 1904. He recalled that in "white dresses and large hats, with parasols in their hands, their beauty literally took one's breath away". In 1904 Leonard left Britain for a civil service position in Ceylon

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, also known historically as Ceylon, is an island country in South Asia. It lies in the Indian Ocean, southwest of the Bay of Bengal, separated from the Indian subcontinent, ...

, but returned for a year's leave in 1911 after letters from Lytton Strachey, describing Virginia's beauty enticed him back. He and Virginia attended social engagements together, and he moved into Brunswick Square as a tenant in December of that year.

Leonard proposed to Virginia on 11 January 1912. Initially she expressed reluctance, but the two continued courting. Leonard decided not to return to Ceylon and resigned from his post. On 29 May Virginia declared her love for Leonard, and they married on 10 August at St Pancras Town Hall. The couple spent their honeymoon first at Asham and the Quantock Hills

The Quantock Hills west of Bridgwater in Somerset, England, consist of heathland, oak woodlands, ancient parklands and agricultural land. They were England's first Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, designated in 1956.

Natural England have desi ...

before travelling to the south of France, Spain and Italy. Upon returning, they moved to Clifford's Inn

Clifford's Inn is the name of both a former Inn of Chancery in London and a present mansion block on the same site. It is located between Fetter Lane and Clifford's Inn Passage (which runs between Fleet Street and Chancery Lane) in the City of ...

, and began to divide their time between London and Asham. Though Virginia wanted to have children, Leonard refused, as he believed Virginia was not mentally strong enough to be a mother, and worried that having children might worsen her mental health.

Virginia had completed a penultimate draft of her first novel ''The Voyage Out

''The Voyage Out'' is the first novel by Virginia Woolf, published in 1915 by Duckworth.

Development and first draft

Woolf began work on ''The Voyage Out'' by 1910 (perhaps as early as 1907) and had finished an early draft by 1912. The novel ...

'' before her wedding but made large-scale alterations to the manuscript between December 1912 and March 1913. The work was later accepted by her half-brother Gerald Duckworth's publishing house, and she found the process of reading and correcting the proofs extremely emotionally difficult. This led to one of several breakdowns over the next two years; Virginia attempted suicide on 9 September 1913 with an overdose of Veronal

Barbital (or barbitone), sold under the brand names Veronal for the pure acid and Medinal for the sodium salt, was the first commercially available barbiturate. It was used as a sleeping aid (hypnotic) from 1903 until the mid-1950s. The chemical ...

, being saved with the help of surgeon Geoffrey Keynes

Sir Geoffrey Langdon Keynes ( ; 25 March 1887, Cambridge – 5 July 1982, Cambridge) was a British surgeon and author. He began his career as a physician in World War I, before becoming a doctor at St Bartholomew's Hospital in London, where he ...

. Virginia's illness led to Duckworth delaying the publication of ''The Voyage Out'' until 26 March 1915.

In the autumn of 1914 the couple moved to a house on Richmond Green

Richmond Green is a recreation area near the centre of Richmond, London, Richmond, a town of about 20,000 inhabitants situated in south-west London. Owned by the Crown Estate, it is leased to the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. The Gree ...

. In late March 1915 they moved to Hogarth House, after which they named their publishing house in 1917. The decision to move to London's suburbs was made for the sake of Virginia's health. Many of Virginia's friends were against the war, and Virginia herself opposed it from a standpoint of pacifism and anti-censorship. Leonard was exempted from the introduction of conscription in 1916 on medical grounds. The Woolfs employed two servants at the recommendation of Roger Fry

Roger Eliot Fry (14 December 1866 – 9 September 1934) was an English painter and art critic, critic, and a member of the Bloomsbury Group. Establishing his reputation as a scholar of the Old Masters, he became an advocate of more recent ...

in 1916; Lottie Hope worked for some other Bloomsbury Group members, and Nellie Boxall would stay with them until 1934.

The Woolfs spent parts of the World War I era in Asham but were obliged by the owner to leave in 1919. "In despair" they purchased the Round House in Lewes. No sooner had they bought the Round House, than Monk's House

Monk's House is a 16th-century weatherboarded cottage in the village of Rodmell, three miles (4.8 km) south of Lewes, East Sussex, England. The writer Virginia Woolf and her husband, the political activist, journalist and editor Leonard W ...

in nearby Rodmell

Rodmell is a small village and civil parish in the Lewes District of East Sussex, England. It is located three miles (4.8 km) south-east of Lewes, on the Lewes to Newhaven road and six and a half miles from the City of Brighton & Hove and ...

came up for auction, a weatherboarded house with oak-beamed rooms, said to date from the 15th or 16th century. The Woolfs sold the Round House and purchased Monk's House for £700. Monk's House also lacked running water but came with an acre of garden, and had a view across the Ouse towards the hills of the South Downs

The South Downs are a range of chalk hills in the south-eastern coastal counties of England that extends for about across the south-eastern coastal counties of England from the Itchen valley of Hampshire in the west to Beachy Head, in the ...

. Leonard Woolf describes this view as being unchanged since the days of Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer ( ; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for '' The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He ...

. The Woolfs would retain Monk's House until the end of Virginia's life; it became their permanent home after their London home was bombed, and it was where she completed ''Between the Acts

''Between the Acts'' is the final novel by Virginia Woolf. It was published shortly after her death in 1941. Although the manuscript had been completed, Woolf had yet to make final revisions.

The book describes the mounting, performance, and a ...

'' in early 1941, which was followed by her final breakdown and suicide in the nearby River Ouse on 28 March.

Further works (19201940)

Memoir Club

1920 saw a postwar reconstitution of the Bloomsbury Group, under the title of the Memoir Club, which as the name suggests focussed on self-writing, in the manner of Proust

Valentin Louis Georges Eugène Marcel Proust ( ; ; 10 July 1871 – 18 November 1922) was a French novelist, literary critic, and essayist who wrote the novel (in French language, French – translated in English as ''Remembrance of Things Pas ...

's '' A La Recherche'', and inspired some of the more influential books of the 20th century. The Group, which had been scattered by the war, was reconvened by Mary ('Molly') MacCarthy who called them "Bloomsberries", and operated under rules derived from the Cambridge Apostles

The Cambridge Apostles (also known as the Conversazione Society) is an intellectual society at the University of Cambridge founded in 1820 by George Tomlinson, a Cambridge student who became the first Bishop of Gibraltar.

History

Student ...

, an elite university debating society of which some of them had been members. These rules emphasised candour and openness. Among the 125 memoirs presented, Virginia contributed three that were published posthumously in 1976, in the autobiographical anthology ''Moments of Being

''Moments of Being'' is a collection of posthumously-published autobiographical essays by Virginia Woolf. The collection was first found in the papers of her husband, used by Quentin Bell in his biography of Virginia Woolf, published in 1972. ...

''. These were ''22 Hyde Park Gate'' (1921), ''Old Bloomsbury'' (1922) and ''Am I a Snob?'' (1936).

Vita Sackville-West

On 14 December 1922 Woolf met the writer and gardener Vita Sackville-West

Victoria Mary, Lady Nicolson, Order of the Companions of Honour, CH (née Sackville-West; 9 March 1892 – 2 June 1962), usually known as Vita Sackville-West, was an English author and garden designer.

Sackville-West was a successful nov ...

, wife of Harold Nicolson

Sir Harold George Nicolson (21 November 1886 – 1 May 1968) was a British politician, writer, broadcaster and gardener. His wife was Vita Sackville-West.

Early life and education

Nicolson was born in Tehran, Persia, the youngest son of dipl ...

. This period was to prove fruitful for both authors, Woolf producing three novels, ''To the Lighthouse'' (1927), ''Orlando'' (1928), and ''The Waves'' (1931) as well as a number of essays, including "Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown

''Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown'' is an essay by Virginia Woolf published in 1924 which explores modernity. It includes the famous observation by Woolf that "on or about December 1910 human character changed."

History

The writer Arnold Bennett h ...

" (1924) and "A Letter to a Young Poet

''A Letter to a Young Poet'' is an epistolary essay by Virginia Woolf, written in 1932 to John Lehman, laying out her views on modern poetry.

History

In 1932, Woolf responded to a letter from the writer, John Lehmann, about her novel '' The Wa ...

" (1932). The two women remained friends until Woolf's death in 1941.

Virginia Woolf also remained close to her surviving siblings, Adrian and Vanessa.

Further novels and non-fiction

Between 1924 and 1940 the Woolfs returned to Bloomsbury, taking out a ten-year lease at 52 Tavistock Square

Tavistock Square is a public square in Bloomsbury, in the London Borough of Camden near Euston Station.

History

Tavistock Square was built shortly after 1806 by the property developer James Burton and the master builder Thomas Cubitt for Fr ...

, from where they ran the Hogarth Press

The Hogarth Press is a book publishing Imprint (trade name), imprint of Penguin Random House that was founded as an independent company in 1917 by British authors Leonard Woolf and Virginia Woolf. It was named after their house in London Boro ...

from the basement, where Virginia also had her writing room.

1925 saw the publication of ''Mrs Dalloway'' in May followed by her collapse while at Charleston in August. In 1927, her next novel, ''To the Lighthouse'', was published, and the following year she lectured on ''Women & Fiction'' at Cambridge University and published ''Orlando'' in October.

Her two Cambridge lectures then became the basis for her major essay ''A Room of One's Own'' in 1929. Virginia wrote only one drama, ''Freshwater

Fresh water or freshwater is any naturally occurring liquid or frozen water containing low concentrations of dissolved salts and other total dissolved solids. The term excludes seawater and brackish water, but it does include non-salty mi ...

'', based on her great-aunt Julia Margaret Cameron

Julia Margaret Cameron (; 11 June 1815 – 26 January 1879) was an English photographer who is considered one of the most important portraitists of the 19th century. She is known for her Soft focus, soft-focus close-ups of famous Victorian era, ...

, and produced at her sister's studio on Fitzroy Street in 1935. 1936 saw the publication of ''The Years

''The Years'' is a 1937 novel by Virginia Woolf, the last she published in her lifetime. It traces the history of the Pargiter family from the 1880s to the "present day" of the mid-1930s.

Although spanning fifty years, the novel is not epic i ...

'', which had its origin in a lecture Woolf gave to the National Society for Women's Service in 1931, an edited version of which would later be published as "Professions for Women". Another collapse of her health followed the novel's completion ''The Years

''The Years'' is a 1937 novel by Virginia Woolf, the last she published in her lifetime. It traces the history of the Pargiter family from the 1880s to the "present day" of the mid-1930s.

Although spanning fifty years, the novel is not epic i ...

''.

The Woolfs' final residence in London was at 37 Mecklenburgh Square (1939–1940), destroyed during the Blitz

The Blitz (English: "flash") was a Nazi Germany, German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom, for eight months, from 7 September 1940 to 11 May 1941, during the Second World War.

Towards the end of the Battle of Britain in 1940, a co ...

in September 1940; a month later their previous home on Tavistock Square was also destroyed. After that, they made Sussex their permanent home.

Death

After completing the manuscript of her last novel (posthumously published), ''

After completing the manuscript of her last novel (posthumously published), ''Between the Acts

''Between the Acts'' is the final novel by Virginia Woolf. It was published shortly after her death in 1941. Although the manuscript had been completed, Woolf had yet to make final revisions.

The book describes the mounting, performance, and a ...

'' (1941), Woolf fell into a depression similar to one that she had earlier experienced. The onset of the Second World War, the destruction of her London home during the Blitz

The Blitz (English: "flash") was a Nazi Germany, German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom, for eight months, from 7 September 1940 to 11 May 1941, during the Second World War.

Towards the end of the Battle of Britain in 1940, a co ...

, and the cold reception given to her biography of her late friend Roger Fry

Roger Eliot Fry (14 December 1866 – 9 September 1934) was an English painter and art critic, critic, and a member of the Bloomsbury Group. Establishing his reputation as a scholar of the Old Masters, he became an advocate of more recent ...

all worsened her condition until she was unable to work. When Leonard enlisted in the Home Guard

Home guard is a title given to various military organizations at various times, with the implication of an emergency or reserve force raised for local defense.

The term "home guard" was first officially used in the American Civil War, starting ...

, Virginia disapproved. She held fast to her pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition to war or violence. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaigner Émile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress in Glasgow in 1901. A related term is ...

and criticised her husband for wearing what she considered to be "the silly uniform of the Home Guard".

After the Second World War began, Woolf's diary indicates that she was obsessed with death, which figured more and more as her mood darkened. On 28 March 1941, Woolf drowned herself by walking into the fast-flowing River Ouse near her home, after placing a large stone in her pocket. Her body was not found until 18 April. Her husband buried her cremated remains beneath an elm tree in the garden of Monk's House

Monk's House is a 16th-century weatherboarded cottage in the village of Rodmell, three miles (4.8 km) south of Lewes, East Sussex, England. The writer Virginia Woolf and her husband, the political activist, journalist and editor Leonard W ...

, their home in Rodmell

Rodmell is a small village and civil parish in the Lewes District of East Sussex, England. It is located three miles (4.8 km) south-east of Lewes, on the Lewes to Newhaven road and six and a half miles from the City of Brighton & Hove and ...

, Sussex.

In her suicide note, addressed to her husband, she wrote:

Mental health

Much examination has been made of Woolf's mental health. From the age of 13, following the death of her mother, Woolf suffered periodic mood swings. However, Hermione Lee

Dame Hermione Lee (born 29 February 1948) is a British biographer, literary critic and academic. She is a former President of Wolfson College, Oxford, and a former Goldsmiths' Professor of English Literature in the University of Oxford and Pr ...

asserts that Woolf was not "mad"; she was merely a woman who suffered from and struggled with illness for much of her life, a woman of "exceptional courage, intelligence and stoicism", who made the best use, and achieved the best understanding she could, of that illness.

Her mother's death in 1895, "the greatest disaster that could happen", precipitated a crisis for which their family doctor, Dr Seton, prescribed rest, stopping lessons and writing, and regular walks supervised by Stella. Yet just two years later, Stella too was dead, bringing on Virginia's first expressed wish for death at the age of 15. This was a scenario she would later recreate in "Time Passes" (''To the Lighthouse'', 1927).Twickenham

Twickenham ( ) is a suburban district of London, England, on the River Thames southwest of Charing Cross. Historic counties of England, Historically in Middlesex, since 1965 it has formed part of the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, who ...

, described as "a private nursing home for women with nervous disorder" run by Miss Jean Thomas. By the end of February 1910, she was becoming increasingly restless, and Savage suggested being away from London. Vanessa rented Moat House, outside Canterbury, in June, but there was no improvement, so Savage sent her to Burley for a "rest cure". This involved partial isolation, deprivation of literature, and force-feeding, and after six weeks she was able to convalesce in Cornwall and Dorset during the autumn.

She loathed the experience; writing to her sister on 28 July, she described how she found the religious atmosphere stifling and the institution ugly, and informed Vanessa that to escape "I shall soon have to jump out of a window". The threat of being sent back would later lead to her contemplating suicide. Despite her protests, Savage would refer her back in 1912 for insomnia and in 1913 for depression.

On emerging from Burley House in September 1913, she sought further opinions from two other physicians on the 13th: Maurice Wright, and Henry Head

Sir Henry Head, FRS (4 August 1861 – 8 October 1940) was an English neurologist who conducted pioneering work into the somatosensory system and sensory nerves. Much of this work was conducted on himself, in collaboration with the psychiatri ...

, who had been Henry James

Henry James ( – ) was an American-British author. He is regarded as a key transitional figure between literary realism and literary modernism, and is considered by many to be among the greatest novelists in the English language. He was the ...

's physician. Both recommended she return to Burley House. Distraught, she returned home and attempted suicide by taking an overdose of 100 grains

A grain is a small, hard, dry fruit ( caryopsis) – with or without an attached hull layer – harvested for human or animal consumption. A grain crop is a grain-producing plant. The two main types of commercial grain crops are cereals and le ...

of veronal

Barbital (or barbitone), sold under the brand names Veronal for the pure acid and Medinal for the sodium salt, was the first commercially available barbiturate. It was used as a sleeping aid (hypnotic) from 1903 until the mid-1950s. The chemical ...

(a barbiturate) and nearly dying.East Grinstead

East Grinstead () is a town in West Sussex, England, near the East Sussex, Surrey, and Kent borders, south of London, northeast of Brighton, and northeast of the county town of Chichester. Situated in the northeast corner of the county, bord ...

, Sussex, to convalesce on 30 September, returning to ''Asham'' on 18 November. She remained unstable over the next two years, with another incident involving veronal that she claimed was an 'accident', and consulted another psychiatrist in April 1914, Maurice Craig, who explained that she was not sufficiently psychotic to be certified or committed to an institution.

The rest of the summer of 1914 went better for her, and they moved to Richmond, but in February 1915, just as ''The Voyage Out'' was due to be published, she relapsed once more, and remained in poor health for most of that year. Then she began to recover, following 20 years of ill health.digitalis

''Digitalis'' ( or ) is a genus of about 20 species of herbaceous perennial plants, shrubs, and Biennial plant, biennials, commonly called foxgloves.

''Digitalis'' is native to Europe, Western Asia, and northwestern Africa. The flowers are ...

, going for a little walk, & plunging back into bed again."

Though this instability would frequently affect her social life, she was able to continue her literary productivity with few interruptions throughout her life. Woolf herself provides not only a vivid picture of her symptoms in her diaries and letters but also her response to the demons that haunted her and at times made her long for death: "But it is always a question whether I wish to avoid these glooms... These 9 weeks give one a plunge into deep waters... One goes down into the well & nothing protects one from the assault of truth."

Psychiatry had little to offer Woolf, but she recognised that writing was one of the behaviours that enabled her to cope with her illness: "The only way I keep afloat... is by working... Directly I stop working I feel that I am sinking down, down. And as usual, I feel that if I sink further I shall reach the truth." Sinking underwater was Woolf's metaphor for both the effects of depression and psychosis— but also for finding the truth, and ultimately was her choice of death.

Throughout her life, Woolf struggled, without success, to find meaning in her illness: on the one hand, an impediment, on the other, something she visualised as an essential part of who she was, and a necessary condition of her art. Her experiences informed her work, such as the character of Septimus Warren Smith in ''Mrs Dalloway'' (1925), who, like Woolf, was haunted by the dead, and ultimately takes his own life rather than be admitted to a sanatorium.

Leonard Woolf relates how during the 30 years they were married, they consulted many doctors in the Harley Street

Harley Street is a street in Marylebone, Central London, named after Edward Harley, 2nd Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer.[neurasthenia

Neurasthenia ( and () 'weak') is a term that was first used as early as 1829 for a mechanical weakness of the nerves. It became a major diagnosis in North America during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries after neurologist Georg ...]

, he felt they had little understanding of the causes or nature. The proposed solution was simple—as long as she lived a quiet life without any physical or mental exertion, she was well. In contrast, any mental, emotional, or physical strain resulted in a reappearance of her symptoms, beginning with a headache, followed by insomnia and thoughts that started to race. Her remedy was simple: to retire to bed in a darkened room, following which the symptoms slowly subsided.

Modern scholars, including her nephew and biographer, Quentin Bell

Quentin Claudian Stephen Bell (19 August 1910 – 16 December 1996) was an English art historian and author.

Early life

Bell was born in London, the second and younger son of the art critic and writer Clive Bell and the painter and interior ...

, have suggested her breakdowns and subsequent recurring depressive periods were influenced by the sexual abuse to which she and her sister Vanessa were subjected by their half-brothers George

George may refer to:

Names

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

People

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Papagheorghe, also known as Jorge / GEØRGE

* George, stage name of Gior ...

and Gerald Duckworth

Gerald de l'Etang Duckworth (29 October 1870 – 28 September 1937) was an English publisher, who founded the London company that bears his name. Henry James and John Galsworthy were among the firm's early authors.

Background and early life

...

(which Woolf recalls in her autobiographical essays " A Sketch of the Past" and "22 Hyde Park Gate"). Biographers point out that when Stella died in 1897, there was no counterbalance to control George's predation, and his nighttime prowling. "22 Hyde Park Gate" ends with the sentence "The old ladies of Kensington and Belgravia never knew that George Duckworth was not only father and mother, brother and sister to those poor Stephen girls; he was their lover also."

It is likely that other factors also played a part. It has been suggested that they include genetic predisposition

Genetic predisposition refers to a genetic characteristic which influences the possible phenotypic development of an individual organism within a species or population under the influence of environmental conditions. The term genetic susceptibil ...

. Virginia's father, Leslie Stephen, suffered from depression, and her half-sister Laura was institutionalised. Many of Virginia's symptoms, including persistent headache, insomnia, irritability, and anxiety, resembled those of her father's. Another factor is the pressure she placed upon herself in her work; for instance, her breakdown of 1913 was at least partly triggered by the need to finish ''The Voyage Out''.

Virginia herself hinted that her illness was related to how she saw the repressed position of women in society when she wrote ''A Room of One's Own''.Ethel Smyth

Dame Ethel Mary Smyth (; 22 April 18588 May 1944) was an English composer and a member of the women's suffrage movement. Her compositions include songs, works for piano, chamber music, orchestral works, choral works and operas.

Smyth tended ...

:

Thomas Caramagno and others, in discussing her illness, oppose the "neurotic-genius" way of looking at mental illness, where creativity and mental illness are conceptualised as linked rather than antithetical. Stephen Trombley describes Woolf as having a confrontational relationship with her doctors, and possibly being a woman who is a "victim of male medicine", referring to the lack of understanding, particularly at the time, about mental illness.

Sexuality

The Bloomsbury Group held very progressive views of sexuality and rejected the austere strictness of Victorian society. The majority of its members were homosexual or bisexual.

Woolf had several affairs with women, the most notable being with Vita Sackville-West

Victoria Mary, Lady Nicolson, Order of the Companions of Honour, CH (née Sackville-West; 9 March 1892 – 2 June 1962), usually known as Vita Sackville-West, was an English author and garden designer.

Sackville-West was a successful nov ...

. The two women developed a deep connection; Vita was arguably one of the few people in Virginia's adult life that she was truly close to.

During their relationship, both women saw the peak of their literary careers, with the titular protagonist of Woolf's acclaimed '' Orlando: A Biography'' being inspired by Sackville-West. The pair remained lovers for a decade and stayed close friends for the rest of Woolf's life.Lady Ottoline Morrell

Lady Ottoline Violet Anne Morrell (née Cavendish-Bentinck; 16 June 1873 – 21 April 1938) was an English Aristocracy (class), aristocrat and society hostess. Her patronage was influential in artistic and intellectual circles, where she befri ...

, and Mary Hutchinson.

Work

Woolf is considered to be one of the most important 20th-century novelists. A

Woolf is considered to be one of the most important 20th-century novelists. A modernist

Modernism was an early 20th-century movement in literature, visual arts, and music that emphasized experimentation, abstraction, and Subjectivity and objectivity (philosophy), subjective experience. Philosophy, politics, architecture, and soc ...

, she was one of the pioneers of using stream of consciousness

In literary criticism, stream of consciousness is a narrative mode or method that attempts "to depict the multitudinous thoughts and feelings which pass through the mind" of a narrator. It is usually in the form of an interior monologue which ...

as a narrative device

A plot device or plot mechanism

is any technique in a narrative used to move the plot forward.

A clichéd plot device may annoy the reader and a contrived or arbitrary device may confuse the reader, causing a loss of the suspension of disbelie ...

, alongside contemporaries such as Marcel Proust

Valentin Louis Georges Eugène Marcel Proust ( ; ; 10 July 1871 – 18 November 1922) was a French novelist, literary critic, and essayist who wrote the novel (in French – translated in English as ''Remembrance of Things Past'' and more r ...

, Dorothy Richardson

Dorothy Miller Richardson (17 May 1873 – 17 June 1957) was a British author and journalist. Author of ''Pilgrimage'', a sequence of 13 semi-autobiographical novels published between 1915 and 1967—though Richardson saw them as chapters of o ...

and James Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (born James Augusta Joyce; 2 February 1882 – 13 January 1941) was an Irish novelist, poet, and literary critic. He contributed to the modernist avant-garde movement and is regarded as one of the most influentia ...

.[ Woolf's reputation was at its greatest during the 1930s, but declined considerably following the Second World War. The growth of ]feminist criticism

Feminist literary criticism is literary criticism informed by feminist theory, or more broadly, by the politics of feminism. It uses the principles and ideology of feminism to critique the language of literature. This school of thought seeks to an ...

in the 1970s helped re-establish her reputation.

Virginia submitted her first article in 1890, to a competition in ''Tit-Bits

''Tit-Bits from all the interesting Books and Newspapers of the World'', more commonly known as ''Tit-Bits'' and later as ''Titbits'', was a British weekly magazine founded by George Newnes, a founding figure in popular journalism, on 22 Octo ...

''. Although it was rejected, this shipboard romance by the eight-year-old would presage her first novel 25 years later, as would contributions to the ''Hyde Park News'', such as the model letter "to show young people the right way to express what is in their hearts", a subtle commentary on her mother's legendary matchmaking.[ She transitioned from juvenilia to professional journalism in 1904 at the age of 22. Violet Dickinson introduced her to ]Kathleen Lyttelton

Mary Kathleen Lyttelton (''née'' Clive; 27 February 1856 – 12 January 1907) was a British activist, editor and writer. She devoted much of her life to fighting for women's suffrage and for the improvement of women's lives in general.

After ...

, the editor of the ''Women's Supplement'' of ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

'', a Church of England newspaper. Invited to submit a 1,500-word article, Virginia sent Lyttelton a review of William Dean Howells

William Dean Howells ( ; March 1, 1837 – May 11, 1920) was an American Realism (arts), realist novelist, literary critic, playwright, and diplomat, nicknamed "The Dean of American Letters". He was particularly known for his tenure as editor of ...

' ''The Son of Royal Langbirth'' and an essay about her visit to Haworth

Haworth ( , , ) is a village in West Yorkshire, England, in the Pennines south-west of Keighley, 8 miles (13 km) north of Halifax, west of Bradford and east of Colne in Lancashire. The surrounding areas include Oakworth and Oxenhop ...

that year, ''Haworth, November 1904''. The review was published anonymously on 4 December, and the essay on the 21st.[ In 1905, Woolf began writing for '']The Times Literary Supplement

''The Times Literary Supplement'' (''TLS'') is a weekly literary review published in London by News UK, a subsidiary of News Corp.

History

The ''TLS'' first appeared in 1902 as a supplement to ''The Times'' but became a separate publication ...

'' (TLS); in 2019, the ''TLS'' would publish a collection of her essays entitled ''Genius and Ink: Virginia Woolf on How to Read'', which originally appeared anonymously, as did all their reviews.

Woolf went on to publish novels and essays as a public intellectual to both critical and popular acclaim. Much of her work was self-published through the Hogarth Press

The Hogarth Press is a book publishing Imprint (trade name), imprint of Penguin Random House that was founded as an independent company in 1917 by British authors Leonard Woolf and Virginia Woolf. It was named after their house in London Boro ...

. "Virginia Woolf's peculiarities as a fiction writer have tended to obscure her central strength: she is arguably the major lyrical

Lyrical may refer to:

*Lyrics, or words in songs

* Lyrical dance, a style of dancing

*Emotional, expressing strong feelings

*Lyric poetry

Modern lyric poetry is a formal type of poetry which expresses personal emotions or feelings, typically ...

novelist in the English language. Her novels are highly experimental: a narrative, frequently uneventful and commonplace, is refracted—and sometimes almost dissolved—in the characters' receptive consciousness. Intense lyricism and stylistic virtuosity fuse to create a world overabundant with auditory and visual impressions."[ "The intensity of Virginia Woolf's poetic vision elevates the ordinary, sometimes banal settings"—often wartime environments—"of most of her novels."][

Though at least one biography of Virginia Woolf appeared in her lifetime, the first authoritative study of her life was published in 1972 by her nephew Quentin Bell. ]Hermione Lee

Dame Hermione Lee (born 29 February 1948) is a British biographer, literary critic and academic. She is a former President of Wolfson College, Oxford, and a former Goldsmiths' Professor of English Literature in the University of Oxford and Pr ...

's 1996 biography ''Virginia Woolf'' provides a thorough and authoritative examination of Woolf's life and work, which she discussed in an interview in 1997. In 2001, Louise DeSalvo and Mitchell A. Leaska edited ''The Letters of Vita Sackville-West and Virginia Woolf''. Julia Briggs's ''Virginia Woolf: An Inner Life'' (2005) focuses on Woolf's writing, including her novels and her commentary on the creative process, to illuminate her life. The sociologist Pierre Bourdieu also uses Woolf's literature to understand and analyse gender domination. Woolf biographer Gillian Gill notes that Woolf's traumatic experience of sexual abuse by her half-brothers during her childhood influenced her advocacy for the protection of vulnerable children from similar experiences. Biljana Dojčinović has discussed the issues surrounding translations of Woolf to Serbian as a "border-crossing".

Themes

Woolf's fiction has been studied for its insight into many themes including war, shell shock, witchcraft, and the role of social class in contemporary modern British society. In the postwar ''Mrs Dalloway'' (1925), Woolf addresses the moral dilemma of war and its effects and provides an authentic voice for soldiers returning from the First World War, suffering from shell shock, in the person of Septimus Smith. In ''A Room of One's Own'' (1929) Woolf equates historical accusations of witchcraft with creativity and genius among women "When, however, one reads of a witch being ducked, of a woman possessed by devils...then I think we are on the track of a lost novelist, a suppressed poet, of some mute and inglorious Jane Austen".[ Throughout her work Woolf tried to evaluate the degree to which her privileged background framed the lens through which she viewed class. She examined her own position as someone who would be considered an elitist snob but attacked the class structure of Britain as she found it. In her 1936 essay ''Am I a Snob?'' she examined her values and those of the privileged circle she existed in. She concluded she was, and subsequent critics and supporters have tried to deal with the dilemma of being both elite and a social critic.

The sea is a recurring motif in Woolf's work. Noting Woolf's early memory of listening to waves break in Cornwall, Katharine Smyth writes in '']The Paris Review

''The Paris Review'' is a quarterly English-language literary magazine established in Paris in 1953 by Harold L. Humes, Peter Matthiessen, and George Plimpton. In its first five years, ''The Paris Review'' published new works by Jack Kerouac, ...

'' that "the radiance fcresting water would be consecrated again and again in her writing, saturating not only essays, diaries, and letters but also ''Jacob's Room'', ''The Waves'', and ''To the Lighthouse''." Patrizia A. Muscogiuri explains that "seascapes, sailing, diving and the sea itself are aspects of nature and of human beings' relationship with it which frequently inspired Virginia Woolf's writing." This trope is deeply embedded in her texts' structure and grammar; James Antoniou notes in ''Sydney Morning Herald

''The Sydney Morning Herald'' (''SMH'') is a daily tabloid newspaper published in Sydney, Australia, and owned by Nine Entertainment. Founded in 1831 as the ''Sydney Herald'', the ''Herald'' is the oldest continuously published newspaper in ...

'' how "Woolf made a virtue of the semicolon

The semicolon (or semi-colon) is a symbol commonly used as orthographic punctuation. In the English language, a semicolon is most commonly used to link (in a single sentence) two independent clauses that are closely related in thought, such as ...

, the shape and function of which resembles the wave, her most famous motif."

Despite the considerable conceptual difficulties, given Woolf's idiosyncratic use of language, her works have been translated into over 50 languages. Some writers, such as the Belgian Marguerite Yourcenar

Marguerite Yourcenar (, ; ; born Marguerite Antoinette Jeanne Marie Ghislaine Cleenewerck de Crayencour; 8 June 190317 December 1987) was a Belgian-born French novelist and essayist who became a US citizen in 1947. Winner of the Prix Femina and ...

, had rather tense encounters with her, while others, such as the Argentinian Jorge Luis Borges

Jorge Francisco Isidoro Luis Borges Acevedo ( ; ; 24 August 1899 – 14 June 1986) was an Argentine short-story writer, essayist, poet and translator regarded as a key figure in Spanish literature, Spanish-language and international literatur ...

, produced versions that were highly controversial.

Drama

Virginia Woolf researched the life of her great-aunt, the photographer Julia Margaret Cameron

Julia Margaret Cameron (; 11 June 1815 – 26 January 1879) was an English photographer who is considered one of the most important portraitists of the 19th century. She is known for her Soft focus, soft-focus close-ups of famous Victorian era, ...

, publishing her findings in an essay titled "Pattledom" (1925),Vanessa Bell

Vanessa Bell (née Stephen; 30 May 1879 – 7 April 1961) was an English painter and interior designer, a member of the Bloomsbury Group and the sister of Virginia Woolf (née Stephen).

Early life and education

Vanessa Stephen was the eld ...

on Fitzroy Street in 1935. Woolf directed it herself, and the cast were mainly members of the Bloomsbury Group, including herself. ''Freshwater'' is a short three act comedy satirising the Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the reign of Queen Victoria, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. Slightly different definitions are sometimes used. The era followed the ...

, only performed once in Woolf's lifetime. Beneath the comedic elements, there is an exploration of both generational change and artistic freedom. Both Cameron and Woolf fought against the class and gender dynamics of Victorianism and the play shows links to both ''To the Lighthouse

''To the Lighthouse'' is a 1927 novel by Virginia Woolf. The novel centres on the Ramsay family and their visits to the Isle of Skye in Scotland between 1910 and 1920.

Following and extending the tradition of modernist novelists like Marcel P ...

'' and ''A Room of One's Own

''A Room of One's Own'' is an extended essay, divided into six chapters, by Virginia Woolf, first published in 1929. The work is based on two lectures Woolf delivered in October 1928 at Newnham College, Cambridge, Newnham College and Girton Co ...

'' that would follow.

Non-fiction

Woolf wrote a body of autobiographical work and more than 500 essays and reviews, some of which, like ''A Room of One's Own'' (1929) were of book-length. Not all were published in her lifetime. Shortly after her death, Leonard Woolf produced an edited edition of unpublished essays titled ''The Moment and other Essays'', published by the Hogarth Press in 1947. Many of these were originally lectures that she gave, and several more volumes of essays followed, such as ''The Captain's Death Bed: and other essays'' (1950).

''A Room of One's Own''

Among Woolf's non-fiction works, one of the best known is ''A Room of One's Own'' (1929), a book-length essay divided into six chapters. Considered a key work of feminist literary criticism, it was written following two lectures she delivered on "Women and Fiction" at Cambridge University the previous year. In it, she examines the historical disempowerment women have faced in many spheres, including social, educational and financial. One of her more famous dicta is contained within the book "A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction". Much of her argument ("to show you how I arrived at this opinion about the room and the money") is developed through the "unsolved problems" of women and fiction writing to arrive at her conclusion, although she claimed that was only "an opinion upon one minor point". In doing so, she states a good deal about the nature of women and fiction, employing a quasi-fictional style as she examines where women writers failed because of lack of resources and opportunities, examining along the way the experiences of the Brontës, George Eliot

Mary Ann Evans (22 November 1819 – 22 December 1880; alternatively Mary Anne or Marian), known by her pen name George Eliot, was an English novelist, poet, journalist, translator, and one of the leading writers of the Victorian era. She wrot ...

and George Sand

Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin de Francueil (; 1 July 1804 – 8 June 1876), best known by her pen name George Sand (), was a French novelist, memoirist and journalist. Being more renowned than either Victor Hugo or Honoré de Balz ...

, as well as the fictional character of Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

's sister, equipped with the same genius but not position. She contrasts these women who accepted a deferential status with Jane Austen

Jane Austen ( ; 16 December 1775 – 18 July 1817) was an English novelist known primarily for #List of works, her six novels, which implicitly interpret, critique, and comment on the English landed gentry at the end of the 18th century ...

, who wrote entirely as a woman.

Hogarth Press

Virginia had taken up book-binding as a pastime in October 1901, at the age of 19. The Woolfs had been discussing setting up a publishing house for some timeLeonard intended for it to give Virginia a rest from the strain of writing, and thereby help her fragile mental health. Additionally, publishing her works under their own outfit would save her from the stress of submitting her work to an external company, which contributed to her breakdown during the process of publishing her first novel ''The Voyage Out''. The Woolfs obtained their own hand-printing press in April 1917 and set it up on their dining room table at Hogarth House, thus beginning the

Virginia had taken up book-binding as a pastime in October 1901, at the age of 19. The Woolfs had been discussing setting up a publishing house for some timeLeonard intended for it to give Virginia a rest from the strain of writing, and thereby help her fragile mental health. Additionally, publishing her works under their own outfit would save her from the stress of submitting her work to an external company, which contributed to her breakdown during the process of publishing her first novel ''The Voyage Out''. The Woolfs obtained their own hand-printing press in April 1917 and set it up on their dining room table at Hogarth House, thus beginning the Hogarth Press

The Hogarth Press is a book publishing Imprint (trade name), imprint of Penguin Random House that was founded as an independent company in 1917 by British authors Leonard Woolf and Virginia Woolf. It was named after their house in London Boro ...

.

The first publication was ''Two Stories'' in July 1917, consisting of "The Mark on the Wall" by Virginia Woolf (which has been described as "Woolf's first foray into modernism") and "Three Jews" by Leonard Woolf. The accompanying illustrations by Dora Carrington

Dora de Houghton Carrington (29 March 1893 – 11 March 1932), known generally as Carrington, was an English painter and decorative artist, remembered in part for her association with members of the Bloomsbury Group, especially the writer Lytt ...