Woman Suffrage Procession on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Woman Suffrage Procession on March 3, 1913, was the first

Just as the parade's timing was tied to the inauguration, so was the route Paul preferred to have the maximum impact on public perception. She requested a permit to march down Pennsylvania Avenue from the Peace Monument to the Treasury Building, then on to the

Just as the parade's timing was tied to the inauguration, so was the route Paul preferred to have the maximum impact on public perception. She requested a permit to march down Pennsylvania Avenue from the Peace Monument to the Treasury Building, then on to the

Jane Walker Burleson on horseback, accompanying a model of the

Jane Walker Burleson on horseback, accompanying a model of the

"TAKING IT to the STREET."

Cobblestone. Retrieved March 12, 2015. These scenes were performed by silent actors to portray various attributes of patriotism and civic pride, which both men and women strove to emulate. The audience would recognize the presentation style from similar holiday events nationwide. MacKaye set each scene using women clad in The act began with a relay of trumpet calls from the Peace Monument to the Treasury Building. The first scene featured Columbia, who stepped forward on stage to the strains of "

The act began with a relay of trumpet calls from the Peace Monument to the Treasury Building. The first scene featured Columbia, who stepped forward on stage to the strains of "

With the prevalence of

With the prevalence of

"Official Program, Woman Suffrage Procession, Washington, D.C., March 3, 1913"

(Washington, 1913), Library of Congress. * Flexner, Eleanor (1959). ''Century of Struggle''. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. * Kraditor, Aileen S. (1965). '' The Ideas of the Woman Suffrage Movement 1890-1920''. New York and London: Columbia University Press. * * Stevens, Doris (1920). '' Jailed for Freedom''. New York: Boni and Liveright. * Wheeler, Marjorie Spruill, ed. (1995). ''One Woman, One Vote: Rediscovering the Woman Suffrage Movement''. Troutdale, OR: NewSage Press. . * Zahniser, J. D. and Amelia R. Fry (2014). ''Alice Paul: Claiming Power''. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. .

"The 1913 Women's Suffrage Parade"

by Alan Taylor in the March 1, 2013, edition of ''

suffragist

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to vo ...

parade in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

It was also the first large, organized march on Washington for political purposes. The procession was organized by the suffragists Alice Paul

Alice Stokes Paul (January 11, 1885 – July 9, 1977) was an American Quaker, suffragette, suffragist, feminist, and women's rights activist, and one of the foremost leaders and strategists of the campaign for the Nineteenth Amendment to the Unit ...

and Lucy Burns for the National American Woman Suffrage Association

The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was an organization formed on February 18, 1890, to advocate in favor of women's suffrage in the United States. It was created by the merger of two existing organizations, the National Woma ...

(NAWSA). Planning for the event began in Washington in December 1912. As stated in its official program, the parade's purpose was to "march in a spirit of protest against the present political organization of society, from which women are excluded."

Participation numbers vary between 5,000 and 10,000 marchers. Suffragists and supporters marched down Pennsylvania Avenue

Pennsylvania Avenue is a primarily diagonal street in Washington, D.C. that connects the United States Capitol with the White House and then crosses northwest Washington, D.C. to Georgetown (Washington, D.C.), Georgetown. Traveling through So ...

on Monday, March 3, 1913, the day before President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

's inauguration

In government and politics, inauguration is the process of swearing a person into office and thus making that person the incumbent. Such an inauguration commonly occurs through a formal ceremony or special event, which may also include an inau ...

. Paul had selected the venue and date to maximize publicity but met resistance from the D.C. police department. The demonstration consisted of a procession with floats, bands, and various groups representing women at home, in school, and the workplace. At the Treasury Building, a pageant of allegorical tableaux was acted out during the parade. The final act was a rally at the Memorial Continental Hall with prominent speakers, including Anna Howard Shaw and Helen Keller

Helen Adams Keller (June 27, 1880 – June 1, 1968) was an American author, disability rights advocate, political activist and lecturer. Born in West Tuscumbia, Alabama, she lost her sight and her hearing after a bout of illness when ...

.

Before the event, Black participation in the march threatened to cause a rift with delegations from Southern states. Some Black people did march with state delegations. A group from Howard University

Howard University is a private, historically black, federally chartered research university in Washington, D.C., United States. It is classified among "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity" and accredited by the Mid ...

participated in the parade. Some sources allege that Black women were segregated at the back of the parade; however, contemporary sources suggest that they marched with their respective state delegations or professional groups.

During the procession, district police failed to keep the enormous crowd off the street, impeding the marchers' progress. Many participants were subjected to heckling from spectators, though many supporters were present. The marchers were finally assisted by citizens' groups and eventually the cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from ''cheval'' meaning "horse") are groups of soldiers or warriors who Horses in warfare, fight mounted on horseback. Until the 20th century, cavalry were the most mob ...

. The police were subjected to a congressional inquiry due to security failures. The event premiered Paul's campaign to refocus the suffrage movement on obtaining a national constitutional amendment

A constitutional amendment (or constitutional alteration) is a modification of the constitution of a polity, organization or other type of entity. Amendments are often interwoven into the relevant sections of an existing constitution, directly alt ...

for woman's suffrage. This was intended to pressure President Wilson to support an amendment, but he resisted their demands for years afterward.

The procession was featured in the film '' Iron Jawed Angels'' in 2004. A new U.S. ten-dollar bill with parade imagery is planned for circulation in 2026.

Background

American suffragistsAlice Paul

Alice Stokes Paul (January 11, 1885 – July 9, 1977) was an American Quaker, suffragette, suffragist, feminist, and women's rights activist, and one of the foremost leaders and strategists of the campaign for the Nineteenth Amendment to the Unit ...

and Lucy Burns spearheaded a drive to adopt a national strategy for women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the women's rights, right of women to Suffrage, vote in elections. Several instances occurred in recent centuries where women were selectively given, then stripped of, the right to vote. In Sweden, conditional women's suffra ...

in the National American Woman Suffrage Association

The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was an organization formed on February 18, 1890, to advocate in favor of women's suffrage in the United States. It was created by the merger of two existing organizations, the National Woma ...

. Paul and Burns had seen first-hand the effectiveness of militant activism while working for Emmeline Pankhurst

Emmeline Pankhurst (; Goulden; 15 July 1858 – 14 June 1928) was a British political activist who organised the British suffragette movement and helped women to win in 1918 the women's suffrage, right to vote in United Kingdom of Great Brita ...

in the Women's Social and Political Union

The Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) was a women-only political movement and leading militant organisation campaigning for women's suffrage in the United Kingdom founded in 1903. Known from 1906 as the suffragettes, its membership and p ...

(WSPU) in Britain. Their education included rallies, marches, and demonstrations, knowledge the two would put to work back in America. They already had first-hand experience with imprisonment as a backlash against suffrage activism. They had gone on hunger strike

A hunger strike is a method of non-violent resistance where participants fasting, fast as an act of political protest, usually with the objective of achieving a specific goal, such as a policy change. Hunger strikers that do not take fluids are ...

s and suffered force-feeding

Force-feeding is the practice of feeding a human or animal against their will. The term ''gavage'' (, , ) refers to supplying a substance by means of a small plastic feeding tube passed through the nose (nasogastric tube, nasogastric) or mouth (o ...

. They were not afraid to be provocative, even knowing the potential consequences. The procession would be their first foray into moving into militant mode on a national stage.Adams and Keene (2008). p. 77.

Paul and Burns found that many suffragists supported the WSPU's militant tactics, including Harriot Stanton Blatch, Alva Belmont, Elizabeth Robins, and Rhetta Child Dorr. Burns and Paul recognized that the women from the six states that had full suffrage at the time comprised a powerful voting bloc. They submitted a proposal to Anna Howard Shaw and the NAWSA leadership at their annual convention in 1912. The leadership was not interested in changing the state-by-state strategy and rejected the idea of holding a campaign that would hold the Democratic Party responsible. Paul and Burns appealed to prominent reformer Jane Addams

Laura Jane Addams (September 6, 1860May 21, 1935) was an American Settlement movement, settlement activist, Social reform, reformer, social worker, sociologist, public administrator, philosopher, and author. She was a leader in the history of s ...

, who interceded on their behalf, resulting in Paul being appointed chair of the Congressional Committee.

Until this time, the women's suffrage movement had relied on oratory and written arguments to keep the issue before the public. Paul believed it was time to add a strong visual element to the campaign, even grander than she had planned for the NAWSA 1912 conference.Zahniser and Fry (2014). p. 128. While her tactics were nonviolent, Paul exploited elements of danger in her events. Her plan for using visual rhetoric was intended to have lasting impact. She felt it was time for women to stop begging for suffrage and demand it with political coercion instead. Though the suffragists had staged marches in many cities, this would be a first for Washington, D.C. It would also be the first large political demonstration in the nation's capital. The only previous similar demonstration was made by a group of five hundred men known as Coxey's Army

Coxey's Army was a protest march by unemployed workers from the United States, led by Ohio businessman Jacob Coxey. They marched on Washington, D.C., in 1894, the second year of a four-year economic depression that was the worst in United S ...

, who had protested about unemployment in 1894.

At the time Paul and Burns were assigned to lead the Congressional Committee of the NAWSA, it was merely a shadow committee headed by Elizabeth Kent, wife of a California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

congressman, with an annual budget of ten dollars that mostly went unspent.Adams and Keene (2008). p. 78. With Paul and Burns in charge, the committee revived the push for a national suffrage amendment. At the end of 1913, Paul reported to the NAWSA that the committee had raised and expended over $25,000 on the suffrage cause for the year.

Paul and Burns persuaded NAWSA to endorse an immense suffrage parade in Washington, D.C., to coincide with newly elected President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

's inauguration

In government and politics, inauguration is the process of swearing a person into office and thus making that person the incumbent. Such an inauguration commonly occurs through a formal ceremony or special event, which may also include an inau ...

the following March. The NAWSA leadership turned over the entire operation to the committee. They organized volunteers, planned, and raised funds in preparation for the parade with little help from the NAWSA.Lunardini (1986). pp. 22-24.

Planning

Committees and recruiting

Once the board approved the parade in December 1912, it appointed Dora Lewis, Mary Ritter Beard, and Crystal Eastman to the committee, though they all worked outside of Washington. All money Paul collected had to be directed through the NAWSA, though she did not always comply.Zahniser and Fry (2014). p. 129. Paul arrived in Washington, D.C., in December 1912 to begin organizing the event. By the time the Congressional Committee had its first meeting in its new Washington headquarters on January 2, 1913, more than 130 women had shown up to start work. Using the list of former committee members, Paul found few still alive or in the city, but she did find assistance. Among local suffragists, she was aided by attorney Florence Etheridge and teacher Elsie Hill, daughter of a congressman. Kent, the former committee chair, was instrumental in opening doors in Washington to Paul and Burns. From the NAWSA, Paul recruited Emma Gillett and Helen Hamilton Gardener to be treasurer and publicity chair, respectively. Belva Lockwood, who had run for president in 1884, also attended the initial meeting.Lunardini (1986). p. 25. Paul recruited Hazel MacKaye to design professional floats and allegorical tableaux to be presented simultaneously with the procession. The parade was officially named the Woman Suffrage Procession. Per the event program, the stated purpose was to "march in a spirit of protest against the present political organization of society, from which women are excluded." Doris Stevens, who worked closely with Paul, stated that "...the procession was to dramatize in numbers and beauty the fact that women wanted to vote - that women were asking the Administration in power in the national government to speed the day." The timing of the date for the procession, March 3, was important because incoming president Woodrow Wilson, whose inauguration was to take place the following day, would be put on notice that this would be a key issue during his term. Paul wanted to put pressure on him to support a national amendment. It also ensured that the procession would enjoy a large audience and publicity. Many factors deterred Paul regarding her selected date: District suffragists worried about the weather; the superintendent of police objected to the timing; even Paul herself was concerned about the need to attract a large number of marchers in a short time frame and get them organized. Fortunately, Washington had congressional delegations from all the states, and some of their wives could be counted on to represent those states. Likewise, the embassies could provide marchers from distant countries.Zahniser and Fry (2014). p. 133. To maximize the use of funds for publicity and building a national network, the Congressional Committee made it clear that participating organizations and delegations would need to fund their own travel, lodging, and other expenses.Parade route and security

Just as the parade's timing was tied to the inauguration, so was the route Paul preferred to have the maximum impact on public perception. She requested a permit to march down Pennsylvania Avenue from the Peace Monument to the Treasury Building, then on to the

Just as the parade's timing was tied to the inauguration, so was the route Paul preferred to have the maximum impact on public perception. She requested a permit to march down Pennsylvania Avenue from the Peace Monument to the Treasury Building, then on to the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest (Washington, D.C.), NW in Washington, D.C., it has served as the residence of every U.S. president ...

before ending at Continental Hall.Adams and Keene (2008). p. 80. District superintendent of police, Major Richard H. Sylvester, offered a permit for Sixteenth Street, which would have taken the procession through a residential area, past several embassies. He later claimed he had thought the suffragists wished to hold the parade at night, and the police could not have provided sufficient security if they marched from the Capitol. Sylvester pointed out the rough character of lower Pennsylvania Avenue and the type of people likely to attend the inauguration. Paul was not satisfied with his alternative route. She took her request to the District commissioners and the press. Eventually, they relented and granted her request. Elsie Hill and her mother had also pressured Sylvester by appealing to Elsie's father in Congress. Congress had the ultimate responsibility and funding control over the District police department.

The presidential inauguration brought a huge influx of visitors from around the country. Media estimated crowds of a quarter to a half million people. Anticipating that most of these people would come to observe the suffrage parade, Paul was concerned about the ability of the local police force to handle the crowd; her disquiet proved to be justified by events. Sylvester had only volunteered a force of 100 officers, which Paul considered inadequate. She attempted to get intervention from President William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) served as the 27th president of the United States from 1909 to 1913 and the tenth chief justice of the United States from 1921 to 1930. He is the only person to have held both offices. ...

, who referred her to Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson. The week before the parade, Congress passed a resolution directing district police to halt all traffic from the Peace Monument to 17th Street from 3 p.m. to 5 p.m. on the day of the parade and prevent any interference with the procession. Paul recruited a woman with political connections to intervene. Elizabeth Selden Rogers contacted her brother-in-law, Secretary Stimson, to request cavalry to provide additional security. He first claimed that using the soldiers for that purpose was prohibited, but later agreed to place troops on standby in case of emergency.Zahniser and Fry (2014). p. 143.

Countering anti-suffrage sentiments

Paul strategically emphasized beauty, femininity, and traditional female roles in the procession. Her chosen theme for the procession was "Ideals and Virtues of American Womanhood".Adams and Keene (2008). p. 81. These characteristics were perceived by anti-suffragists as being most threatened by giving women the vote. She wanted to show that women could be all those things and still be intelligent and competent to vote and fill any other role in society. Attractiveness and professional talent were not mutually exclusive. These ideals were embodied in the selection of the parade's herald, Inez Milholland, a labor lawyer fromNew York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

who had been dubbed "the most beautiful suffragette".Zahniser and Fry (2014). p. 145. Milholland had served in the same role in a suffrage march in the city the previous year.

The procession

The lineup of marchers

Media reported that the suffrage parade outshone even the inauguration. Special suffrage trains were hired to bring spectators from other cities, adding to the crowds in Washington. The novelty of the procession attracted enormous interest throughout the eastern U.S. As the parade participants gathered near the Peace Monument around noon, the police began roping off part of the parade route. Even before the parade began, the ropes were badly stretched and coming loose in places. The procession drew such a crowd that President-elect Wilson was mystified about why there were no people to be seen when he arrived in town that day.Stevens (1920). p. 21.

Jane Walker Burleson on horseback, accompanying a model of the

Jane Walker Burleson on horseback, accompanying a model of the Liberty Bell

The Liberty Bell, previously called the State House Bell or Old State House Bell, is an iconic symbol of American Revolution, American independence located in Philadelphia. Originally placed in the steeple of Pennsylvania State House, now know ...

brought from Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

, led the procession as Grand Marshal, immediately followed by the herald, Milholland, on a white horse. A pale-blue cape flowed over her white suit, held on by a Maltese cross

The Maltese cross is a cross symbol, consisting of four " V" or arrowhead shaped concave quadrilaterals converging at a central vertex at right angles, two tips pointing outward symmetrically.

It is a heraldic cross variant which develope ...

.Adams and Keene (2008). p. 82. Her banner proclaimed "Forward into Light", a phrase originated by Pankhurst and later used by Blatch. Immediately behind the herald was a wagon that boldly stated "We Demand An Amendment To The Constitution Of The United States Enfranchising The Women Of This Country". Next was the national board of the NAWSA, headed by Shaw.

To add to the visual impact, Paul dictated a color scheme

In color theory, a color scheme is a combination of 2 or more colors used in aesthetic or practical design. Aesthetic color schemes are used to create style and appeal. Colors that create a harmonious feeling when viewed together are often u ...

for each group of marchers. The rainbow of colors represented women coming into the light of the future out of the darkness of the past. To add drama between groups of marching women, "Paul recruited 26 floats, 6 golden chariots, 10 bands, 45 captains, 200 marshals, 120 pages, 6 mounted heralds, and 6 mounted brigades", according to Adams and Keene. Estimates about the number of participants in the procession varied from 5,000 to 10,000.

The first section had marchers and floats from countries where women already had the vote: Norway, Finland, Australia, and New Zealand. The second section had floats depicting historic scenes from the suffrage movement in 1840, 1870, and 1890. Then came a float representing the state of the campaign in 1913 in a positive tableau of women inspiring a group of girls. A series of floats depicted men and women working side by side at home and in various professions. They were followed by one with a man holding a representation of government on his shoulders while a woman with hands tied stood helpless at his side.

A float depicted nurses, followed by a marching group of nurses. Groups of women representing traditional roles of motherhood and homemaking came next to change the image of suffragists as being sexless working women.Zahniser and Fry (2014). p. 146. There followed a carefully orchestrated order of professional women, beginning with various nursing groups, the Woman's Christian Temperance Union

The Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) is an international temperance organization. It was among the first organizations of women devoted to social reform with a program that "linked the religious and the secular through concerted and far ...

and the PTA, before finally adding in non-traditional careers such as lawyers, artists, and businesswomen.

After a float depicting the Bill of Rights

A bill of rights, sometimes called a declaration of rights or a charter of rights, is a list of the most important rights to the citizens of a country. The purpose is to protect those rights against infringement from public officials and pri ...

came a banner that showed the nine suffrage states in bright colors with the remaining states in black. This theme was also graphically depicted using women dressed similarly. They carried a banner suggesting that vote-less women were enslaved to men with the vote, quoting Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

: "No Country Can Exist Half Slave and Half Free". Another Lincoln quote was featured at the top of the official program: "I go for all sharing the privilege of the government who assist in bearing its burdens, by no means excluding women." Women from the suffrage states displayed their colorful organization banners on chariot

A chariot is a type of vehicle similar to a cart, driven by a charioteer, usually using horses to provide rapid Propulsion, motive power. The oldest known chariots have been found in burials of the Sintashta culture in modern-day Chelyabinsk O ...

s that preceded each group.

One prominent group featured in the procession was the pilgrims led by "General" Rosalie Jones. The brown-caped hikers covered more than from New York City to Washington in sixteen days. Their journey received considerable press coverage, and a large crowd assembled to greet them upon their arrival in the city on February 28.

Allegorical tableaux

Simultaneous with the procession, an allegorical tableau unfolded on the Treasury Building's steps. The pageant was written by dramatist Hazel MacKaye and directed by Glenna Smith Tinnin.Woelfle, Gretchen (2009)"TAKING IT to the STREET."

Cobblestone. Retrieved March 12, 2015. These scenes were performed by silent actors to portray various attributes of patriotism and civic pride, which both men and women strove to emulate. The audience would recognize the presentation style from similar holiday events nationwide. MacKaye set each scene using women clad in

toga

The toga (, ), a distinctive garment of Ancient Rome, was a roughly semicircular cloth, between in length, draped over the shoulders and around the body. It was usually woven from white wool, and was worn over a tunic. In Roman historical tra ...

-style costumes and accompanied by symbolic parlor music that would also be familiar to the audience.

The act began with a relay of trumpet calls from the Peace Monument to the Treasury Building. The first scene featured Columbia, who stepped forward on stage to the strains of "

The act began with a relay of trumpet calls from the Peace Monument to the Treasury Building. The first scene featured Columbia, who stepped forward on stage to the strains of "The Star-Spangled Banner

"The Star-Spangled Banner" is the national anthem of the United States. The lyrics come from the "Defence of Fort M'Henry", a poem written by American lawyer Francis Scott Key on September 14, 1814, after he witnessed the bombardment of Fort ...

". She summoned Liberty

Liberty is the state of being free within society from oppressive restrictions imposed by authority on one's way of life, behavior, or political views. The concept of liberty can vary depending on perspective and context. In the Constitutional ...

, Charity, Justice, Hope, and Peace to join her. In the final scene, Columbia placed herself as guardian over all these others, and they assembled to watch the approaching procession of suffragists. By creating this stunning drama, Paul differentiated the American suffrage movement from Britain's "by fully appropriating the best possibilities of nonviolent visual rhetoric" per Adams and Keene.

Notable participants

Some women listed were well-known before the event, while others became noteworthy later. Most names come from the official event program. *Dr. Nellie V. Mark served as marshal of the professional women ofMaryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It borders the states of Virginia to its south, West Virginia to its west, Pennsylvania to its north, and Delaware to its east ...

in the Maryland portion of the parade.

*Jeannette Rankin

Jeannette Pickering Rankin (June 11, 1880 – May 18, 1973) was an American politician and women's rights advocate who became the first woman to hold federal office in the United States. She was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives as ...

, from Montana

Montana ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota to the east, South Dakota to the southeast, Wyoming to the south, an ...

, marched under her state's sign; she returned to Washington four years later as a U.S. Representative.

* Charlotte Anita Whitney, who later became a political figure in her home state of California, served as NAWSA's 2nd vice president and marched with the officers.

* Mary Ware Dennett, of New York, also marched with the NAWSA board as corresponding secretary.

* Susan Walker Fitzgerald, NAWSA recording secretary from Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

, later went on to serve in the Massachusetts legislature.

* Katherine Dexter McCormick, NAWSA treasurer, became a notable philanthropist and major funder of birth control research.

* Harriet Burton Laidlaw, 1st auditor on the NAWSA board, was from New York and a political activist on many issues.

* Abby Scott Baker, a D. C. resident and activist, organized the floats and marchers in the section for foreign countries.

* Dorothy Bernard, born in South Africa, had an acting career in California, and organized the group of actresses in the procession.

* Jane Delano, chair and founder of the American Red Cross Nursing Service, organized the nurse's group.

* Carrie Clifford, American feminist author, clubwoman and civil rights activist

* Lavinia Dock, a pioneer in nursing education, assisted Delano with the nursing section of the parade.

* Bertha McNeil was an American civil rights activist

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life of ...

, peace activist, and educator.

* Fola La Follette, Broadway actress from Wisconsin

Wisconsin ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest of the United States. It borders Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake Michigan to the east, Michig ...

and lifelong activist, led the actress group in the march.

*Lillian Wald

Lillian D. Wald (March 10, 1867 – September 1, 1940) was an American nurse, humanitarian and author. She strove for human rights and started American community nursing. She founded the Henry Street Settlement in New York City and was an early ...

, founder of community nursing and involved in founding the NAACP, led the nurses' section.

* Georgiana Simpson, philologist

Philology () is the study of language in oral and written historical sources. It is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguistics with strong ties to etymology. Philology is also defined as the study of ...

and the first African-American woman to receive a PhD

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD, DPhil; or ) is a terminal degree that usually denotes the highest level of academic achievement in a given discipline and is awarded following a course of graduate study and original research. The name of the deg ...

in the United States.

* Ellen Spencer Mussey, a D.C. attorney who later founded the Women's Bar Association of the District of Columbia, led women lawyers in the procession. She secured legislation in Congress to give women in D. C. equal rights to their children.

* Mary Johnston, of Virginia, was a popular writer of historical fiction. She spoke at the rally at Continental Hall after the parade.

* Estelle Willoughby Ions, a composer from Louisiana

Louisiana ( ; ; ) is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It borders Texas to the west, Arkansas to the north, and Mississippi to the east. Of the 50 U.S. states, it ranks 31st in area and 25 ...

, led the musicians section.

* Elizabeth Thacher Kent, worked to pass suffrage legislation in California, and was also an environmentalist. She contracted and organized the bands for the procession.

*Julia Lathrop

Julia Clifford Lathrop (June 29, 1858 – April 15, 1932) was an Americans, American social reformer in the area of education, social policy, and children's welfare. As director of the United States Children's Bureau from 1912 to 1922, she was th ...

, Chief of the U. S. Children's Bureau, was the first woman to head a federal bureau, appointed by President Taft. She marched with the banner for Women in Government Service.

* Annie Jenness Miller, clothing designer, advocate for dress reform, prominent lecturer, and building contractor, organized the grandstand committee.

* Genevieve Clark Thomson, who later ran for Congress from Louisiana, led the Missouri

Missouri (''see #Etymology and pronunciation, pronunciation'') is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it border ...

delegation.

* Harriet Taylor Upton, who became the first female to serve as vice-chair of the Republican National Committee

The Republican National Committee (RNC) is the primary committee of the Republican Party of the United States. Its members are chosen by the state delegations at the national convention every four years. It is responsible for developing and pr ...

, led the delegation from Ohio

Ohio ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Erie to the north, Pennsylvania to the east, West Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Indiana to the ...

.

* Florence Fleming Noyes, a dancer who played the role of Liberty, choreographed the entire tableaux.

* Ann Washington Craton, a labor organizer who was then a student at George Washington University and who marched in cap and gown.

Security failure

The parade and tableaux at the Treasury Building were scheduled to begin simultaneously at 3 p.m. However, the trumpet call starting the procession did not sound until 3:25 p.m. At the lead were several police escort vehicles and six mounted officers in a wedge formation. By the time the front of the parade reached 5th Street, the crowd had completely blocked the avenue. At that point, the police escort seemed to vanish into the crowd. Milholland and others on horseback used the animals to help push back the crowds. Paul, Burns, and other committee members brought a couple of automobiles to the front to help create a passage for the procession. The police had done little to open the parade route as they'd been ordered to do by Congress. Sylvester, who was at the train station awaiting Wilson's arrival, heard about the problem and called the cavalry unit on standby at Fort Myers. However, the mounted soldiers did not arrive on the scene until around 4:30 p.m. They were then able to usher the parade to its completion.Zanhniser and Fry (2014). p. 147. Male and female spectators surged into the street, though men were the majority. There were both hecklers and supporters, but parade-marshal Burleson and other women in the procession were intimidated, particularly by the hostile chants. ''The'' ''Evening Star'' (Washington) published a review highlighting positive responses to the parade and pageant. The crush of people led to trampling: More than two hundred people were treated for injuries at local hospitals. At one point, Paul sympathetically acknowledged that the police were overwhelmed and not enough of them had been assigned to the parade, but she soon changed her stance to maximize publicity for her cause. The police arrested some spectators and fined them for crossing over the ropes. Before the cavalry arrived, other people began helping with crowd control. At times the marchers had been forced to go single file to move forward. Boy Scouts with batons helped push back spectators. A group of soldiers linked arms to hold people back. Some of the Black people who drove the floats also stepped in to help. The Massachusetts and the Pennsylvania national guards stepped in, too. Eventually, boys from the Maryland Agricultural College created a human barrier protecting the women from the angry crowd and helping them reach their destination.Rally at Continental Hall

The final act was a meeting at the Memorial Continental Hall (later part of the expanded DAR Constitution Hall), the national headquarters of theDaughters of the American Revolution

The National Society Daughters of the American Revolution (often abbreviated as DAR or NSDAR) is a lineage-based membership service organization for women who are directly descended from a patriot of the American Revolutionary War.

A non-p ...

. Speakers were Anna Howard Shaw, Carrie Chapman Catt

Carrie Chapman Catt (born Carrie Clinton Lane; January 9, 1859#Fowler, Fowler, p. 3 – March 9, 1947) was an American women's suffrage leader who campaigned for the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which gave U.S. women t ...

, Mary Johnston, and Helen Adams Keller. Shaw, reflecting on the failure of police protection, stated that she was ashamed of the national capital, but she praised the marchers. She also recognized that they could use publicity about police failures to the suffragists' advantage. Blatch had used a similar security failure in New York in 1912 to the suffragists' advantage.Zahniser and Fry (2014). p. 149.

Aftermath

Alice Paul's response

Though she first sympathized with the overwhelmed police force at the parade, Paul quickly capitalized on the verbal abuse the marchers had endured. She blamed the police for colluding with violent opposition to the nonviolent demonstration. She asked participants to writeaffidavit

An ( ; Medieval Latin for "he has declared under oath") is a written statement voluntarily made by an ''affiant'' or ''deposition (law), deponent'' under an oath or affirmation which is administered by a person who is authorized to do so by la ...

s about negative reactions they'd experienced, which Paul used to request Congressional action against Chief Sylvester. She also used these statements to generate press releases in Washington and nationwide, garnering additional publicity for the suffrage procession. The resulting publicity also brought in additional donations that helped Paul cover the event's cost of $13,750.Lunardini (1986). p. 31.

Paul's publicity campaign stressed that the marchers had demonstrated bravery and nonviolent resistance to the hostile crowd. Several suffragists pointed out in the media that a government that couldn't protect its female citizens could not properly represent them. Paul's deft handling of the situation made woman's suffrage one of the most-discussed subjects in America.Adams and Keene (2008). pp. 95–96.

Paul also orchestrated a meeting, primarily of political men who were suffrage supporters, at the Columbia Theater. The purpose was to pressure Congress to hold hearings about police misconduct. Key participants included activist attorney Louis Brandeis

Louis Dembitz Brandeis ( ; November 13, 1856 – October 5, 1941) was an American lawyer who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, associate justice on the Supreme Court of the United States from 1916 to ...

(who became a Supreme Court justice in 1916) and Minnesota senator Moses Edwin Clapp. She kept her role in organizing the event out of the spotlight.

Congressional response

The Senate Committee on the District of Columbia quickly organized a subcommittee hearing to determine why the crowds at the parade had gotten out of hand. They listened to testimony and read numerous affidavits. Hearings were held March 6–13 and April 16–17. Sylvester defended his actions and blamed individual police officers for disobeying his orders. In the end, Sylvester was exonerated, but public opinion toward him was unfavorable. When he was finally forced to resign in 1915 due to an unrelated incident, the mishandling of the 1913 parade was seen as instrumental in his ouster.President Wilson

Alice Paul and the Congressional Union asked President Wilson to push Congress for a federal amendment, beginning with a deputation to the White House shortly after the parade and in several additional visits. He responded initially by saying he had never considered the matter, though he told aColorado

Colorado is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States. It is one of the Mountain states, sharing the Four Corners region with Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah. It is also bordered by Wyoming to the north, Nebraska to the northeast, Kansas ...

delegation in 1911 that he was pondering the subject. Though he assured the women he would consider it, he did not act on the issue; eventually, he flatly remarked there was no room for suffrage on his agenda. The deputation wished Wilson to press his party to support suffrage legislation. He asserted that he had no influence over his party's actions in Congress. Still, for issues he considered important, he did use his leverage in a partisan manner, such as with repealing the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal () is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Caribbean Sea with the Pacific Ocean. It cuts across the narrowest point of the Isthmus of Panama, and is a Channel (geography), conduit for maritime trade between th ...

tolls act.

When asked if it had been unwise for her to push Wilson for his stance on woman's suffrage, Paul responded that it was important to make the public aware of his position so they could use it against him when the time came to put pressure on the Democrats during an election. It took until 1918 for Wilson to finally change his stance on the suffrage amendment.

Impacts on the suffrage movement

Paul inaugurated her leadership in the American suffrage movement with the 1913 procession. This event revived the push for a federal woman's suffrage amendment, a cause that the NAWSA had allowed to languish.Zahniser and Fry (2014). p. 126. Little more than a month after the parade, the Susan B. Anthony amendment was re-introduced in both houses of Congress. For the first time in decades, it was debated on the floor. The demonstration on Pennsylvania Avenue was the precursor to Paul's other high-profile events that, along with actions by the NAWSA, culminated in the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment to the U. S. Constitution in 1919 and itsratification

Ratification is a principal's legal confirmation of an act of its agent. In international law, ratification is the process by which a state declares its consent to be bound to a treaty. In the case of bilateral treaties, ratification is usuall ...

in 1920.

Paul's focus on a federal amendment contrasted sharply with the NAWSA's state-by-state approach to suffrage, leading to a rift between the Constitutional Committee and the national board. The committee disassociated from the NAWSA and became the Congressional Union. The Congressional Union eventually became subsumed by the National Woman's Party

The National Woman's Party (NWP) was an American women's political organization formed in 1916 to fight for women's suffrage. After achieving this goal with the 1920 adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, the NWP ...

, also led by Paul, in 1916.

Miscellaneous

In film

The Woman Suffrage Procession was featured in the 2004 film '' Iron Jawed Angels'', which chronicles the strategies of Alice Paul, Lucy Burns, and the National Woman's Party as they lobby and demonstrate for the passage of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which would assure voting rights for all American women.United States currency

On April 20, 2016, Treasury Secretary Jack Lew announced plans for the back of the new $10 note to feature an image of the 1913 Woman Suffrage Procession that passed the steps of the Treasury Department where the allegorical tableaux took place. It is also planned to honor many of the leaders of the suffrage movement, includingLucretia Mott

Lucretia Mott (née Coffin; January 3, 1793 – November 11, 1880) was an American Quakers, Quaker, Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist, women's rights activist, and social reformer. She had formed the idea of reforming the position ...

, Sojourner Truth

Sojourner Truth (; born Isabella Bomefree; November 26, 1883) was an American Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist and activist for African-American civil rights, women's rights, and Temperance movement, alcohol temperance. Truth was ...

, Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton ( Cady; November 12, 1815 – October 26, 1902) was an American writer and activist who was a leader of the women's rights movement in the U.S. during the mid- to late-19th century. She was the main force behind the 1848 ...

, and Alice Paul

Alice Stokes Paul (January 11, 1885 – July 9, 1977) was an American Quaker, suffragette, suffragist, feminist, and women's rights activist, and one of the foremost leaders and strategists of the campaign for the Nineteenth Amendment to the Unit ...

. The front of the new $10 note is to retain the portrait of Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the first U.S. secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795 dur ...

. Designs for new $5, $10, and $20 bills were to be unveiled in 2020. Later, it was said that the new note would not be ready for circulation until 2026.

Anti-Black racism

The woman's suffrage movement, led in the nineteenth century by women such as Susan B. Anthony andElizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton ( Cady; November 12, 1815 – October 26, 1902) was an American writer and activist who was a leader of the women's rights movement in the U.S. during the mid- to late-19th century. She was the main force behind the 1848 ...

, had its genesis in the abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was Kingdom of France, France in 1315, but it was later used ...

movement, but by the dawn of the twentieth century, Anthony's goal of universal suffrage was eclipsed by a near-universal racism in the United States

Racism has been reflected in discriminatory laws, practices, and actions (including violence) against Race (human categorization), racial or ethnic groups throughout the history of the United States. Since the early Colonial history of the Uni ...

. While earlier suffragists had believed the two issues could be linked, the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment and Fifteenth Amendment created a division between African American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from an ...

rights and suffrage for women by prioritizing voting rights for Black men over universal suffrage for all men and women. In 1903, the NAWSA officially adopted a platform of states' rights

In United States, American politics of the United States, political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments of the United States, state governments rather than the federal government of the United States, ...

that was intended to mollify and bring Southern U.S. suffrage groups into the fold. The statement's signers included Anthony, Carrie Chapman Catt

Carrie Chapman Catt (born Carrie Clinton Lane; January 9, 1859#Fowler, Fowler, p. 3 – March 9, 1947) was an American women's suffrage leader who campaigned for the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which gave U.S. women t ...

, and Anna Howard Shaw.

With the prevalence of

With the prevalence of segregation Segregation may refer to:

Separation of people

* Geographical segregation, rates of two or more populations which are not homogenous throughout a defined space

* School segregation

* Housing segregation

* Racial segregation, separation of human ...

throughout the country and within organizations such as the NAWSA, Black people had formed activist groups to fight for their equal rights. Many were college educated and resented their exclusion from political power. The fiftieth anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War. The Proclamation had the eff ...

issued by President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

in 1863 also fell in 1913, giving them even further incentive to march in the suffrage parade. Nellie Quander

Nellie May Quander (February 11, 1880 - September 24, 1961) was an incorporator and the first international president of Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority. As president for several years, she helped expand the sorority and further its support of African ...

of Alpha Kappa Alpha

Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc. () is an List of African American fraternities, historically African-American Fraternities and sororities, sorority. The sorority was founded in 1908 at Howard University in Washington, D.C.. Alpha Kappa Alpha ...

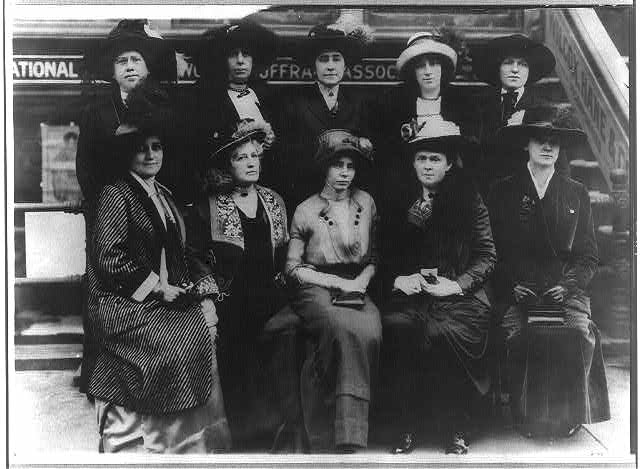

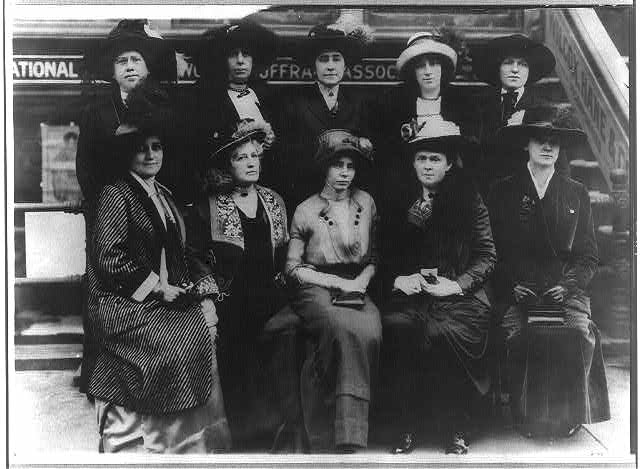

sorority asked for a place in the college women's section for the women of Howard. In a letter dated February 17, 1913 to Alice Paul, Quander discusses the desire for the women of Howard to be given a desirable place in the march and requests Paul to identify a suitable speaker to replace Jane Addams, who was scheduled to address the sorority in March but was preparing to travel to Egypt. These letters were follow up discussions to the one began by Paul and initiated by Elise Hill when Hill went down to Howard University at the request of Paul to recruit the Howard women. The Howard University group included "Artist, one—Mrs. May Howard Jackson; college women, six—Mrs. Mary Church Terrell, Mrs. Daniel Murray, Miss Georgia Simpson, Miss Charlotte Steward, Miss Harriet Shadd, Miss Bertha McNiel; teacher, one—Miss Caddie Park; musician, one— Mrs. Harriett G. Marshall; professional women, two— Dr. Amanda V. Gray, Dr. Eva Ross. Illinois delegation— Mrs. Ida Wells-Barnett; Michigan—Mrs. McCoy, of Detroit, who carried the banner; Howard University, group of twenty-five girls in caps and gowns; homemakers—Mrs. Duffield, who carried New York banner, Mrs. M. D. Butler, Mrs. Carrie W. Clifford." One trained nurse, whose name could not be ascertained, marched, and a child caregiver was brought down by the Delaware delegation.

But the Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

-born Gardener tried to persuade Paul that including Black people would be a bad idea because the Southern delegations threatened to pull out of the march. Paul had attempted to keep news about Black marchers out of the press, but when the Howard group announced they intended to participate, the public became aware of the conflict. A newspaper account indicated that Paul told some Black suffragists that the NAWSA believed in equal rights for "colored women" but that some Southern women were likely to object to their presence. A source in the organization insisted that the official stance was to "permit negroes to march if they cared to". In a 1974 oral history interview, Paul recalled the "hurdle" of Terrell's plan to march, which upset the Southern delegations. She said the situation was resolved when a Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally, others referred to them as Quakers ...

leading the men's section proposed that men march between the Southern and Howard University groups.

While in Paul's memory, a compromise was reached to order the parade as southern women, then the men's section, and finally the Black women's section, reports in the NAACP paper, '' The Crisis'', depict events unfolding quite differently, with Black women protesting the plan to segregate them. What is clear is that some groups attempted, on the day of the parade, to segregate their delegations.Zahniser and Fry (2014). p. 144. For example, a last-minute instruction by the chair of the state delegation section, Genevieve Stone, caused an additional uproar when she asked the Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. It borders on Lake Michigan to its northeast, the Mississippi River to its west, and the Wabash River, Wabash and Ohio River, Ohio rivers to its ...

delegation's sole Black member, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, to march with the segregated group of Black people at the back of the parade. Some historians claim Paul made the request, though this seems unlikely after the official NAWSA decision. Wells-Barnett eventually rejoined the Illinois delegation as the procession moved down the avenue. In the end, Black women marched in several state delegations, including New York and Michigan

Michigan ( ) is a peninsular U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest, Upper Midwestern United States. It shares water and land boundaries with Minnesota to the northwest, Wisconsin to the west, ...

. Some joined in with their co-workers in professional groups. There were also Black men driving many of the floats. The spectators did not treat the Black participants any differently.

See also

* Suffrage Hikes * Mud March, 1907 suffrage procession in London *Women's Sunday

Women's Sunday was a suffragette march and rally held in London on 21 June 1908. Organised by Emmeline Pankhurst's Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) to persuade the Liberal government, 1905–1915, Liberal government to support Women's s ...

, 1908 suffrage march and rally in London

* Women's Coronation Procession, 1911 suffrage march in London

* Great Pilgrimage, 1913 suffrage march in the UK

* Silent Sentinels, 1917 to 1919 protest in Washington, D.C.

* Selma to Montgomery march, 1965 suffrage march in the US

* List of suffragists and suffragettes

This list of suffragists and suffragettes includes noted individuals active in the worldwide women's suffrage movement who have campaigned or strongly advocated for women's suffrage, the organisations which they formed or joined, and the publi ...

* Timeline of women's suffrage

Women's suffrage – the right of women to vote – has been achieved at various times in countries throughout the world. In many nations, women's suffrage was granted before universal suffrage, in which cases women and men from certain Social ...

* Timeline of women's suffrage in the United States

Notes

References

* Adams, Katherine H. and Michael L. Keene (2008). ''Alice Paul and the American Suffrage Campaign''. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. * Adams, Mildred (1967). ''The Right to Be People''. Philadelphia and New York: J. B. Lippincott Co. * Brown, Harriet Connor, ed."Official Program, Woman Suffrage Procession, Washington, D.C., March 3, 1913"

(Washington, 1913), Library of Congress. * Flexner, Eleanor (1959). ''Century of Struggle''. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. * Kraditor, Aileen S. (1965). '' The Ideas of the Woman Suffrage Movement 1890-1920''. New York and London: Columbia University Press. * * Stevens, Doris (1920). '' Jailed for Freedom''. New York: Boni and Liveright. * Wheeler, Marjorie Spruill, ed. (1995). ''One Woman, One Vote: Rediscovering the Woman Suffrage Movement''. Troutdale, OR: NewSage Press. . * Zahniser, J. D. and Amelia R. Fry (2014). ''Alice Paul: Claiming Power''. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. .

External links

"The 1913 Women's Suffrage Parade"

by Alan Taylor in the March 1, 2013, edition of ''

The Atlantic

''The Atlantic'' is an American magazine and multi-platform publisher based in Washington, D.C. It features articles on politics, foreign affairs, business and the economy, culture and the arts, technology, and science.

It was founded in 185 ...

'' magazine

{{Authority control

1913 in the United States

1913 in Washington, D.C.

1913 in women's history

Alice Paul

March 1913 in the United States

Parades in the United States

Progressive Era in the United States

Protest marches in Washington, D.C.

Women in Washington, D.C.

Women's suffrage in the United States

Ida B. Wells