William Gilbert (physicist) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William Gilbert (; 24 May 1544? – 30 November 1603), also known as Gilberd, was an English physician, physicist and

Besides Gilbert's ''De Magnete'', there appeared at Amsterdam in 1651 a quarto volume of 316 pages entitled ''De Mundo Nostro Sublunari Philosophia Nova'' (New Philosophy about our Sublunary World), edited – some say by his brother William Gilbert Junior, and others say, by the eminent English scholar and critic John Gruter – from two manuscripts found in the library of Sir

Besides Gilbert's ''De Magnete'', there appeared at Amsterdam in 1651 a quarto volume of 316 pages entitled ''De Mundo Nostro Sublunari Philosophia Nova'' (New Philosophy about our Sublunary World), edited – some say by his brother William Gilbert Junior, and others say, by the eminent English scholar and critic John Gruter – from two manuscripts found in the library of Sir

*

**

**

*

*

**

**

*

The Galileo Project

— biography of William Gilbert.

— website hosted by NASA — ''Commemorating the 400th anniversary of "De Magnete" by William Gilbert of Colchester''.

Online Galleries, History of Science Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries

High resolution images of works by and/or portraits of William Gilbert in .jpg and .tiff format. * *

— Translation of ''De Magnete'' by Silvanus Thompson for the Gilbert Club, London 1900. Full text, free to read and search. Go to page 9 and read Gilbert saying the Earth revolves leading to the motion of the skies.

The Natural Philosophy of William Gilbert and His Predecessors''De Magnete''

From th

in the Rare Book and Special Collection Division at the

William Gilbert, the first electrician.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Gilbert, William 16th-century English astronomers 16th-century English medical doctors 16th-century English writers 16th-century English male writers Magneticians People associated with electricity English physicists 1540s births 1603 deaths People of the Elizabethan era 16th-century writers in Latin Alumni of St John's College, Cambridge People from Colchester 17th-century deaths from plague (disease) 17th-century English writers 17th-century English male writers

natural philosopher

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the developme ...

. He passionately rejected both the prevailing Aristotelian philosophy

Aristotelianism ( ) is a philosophical tradition inspired by the work of Aristotle, usually characterized by deductive logic and an analytic inductive method in the study of natural philosophy and metaphysics. It covers the treatment of the soc ...

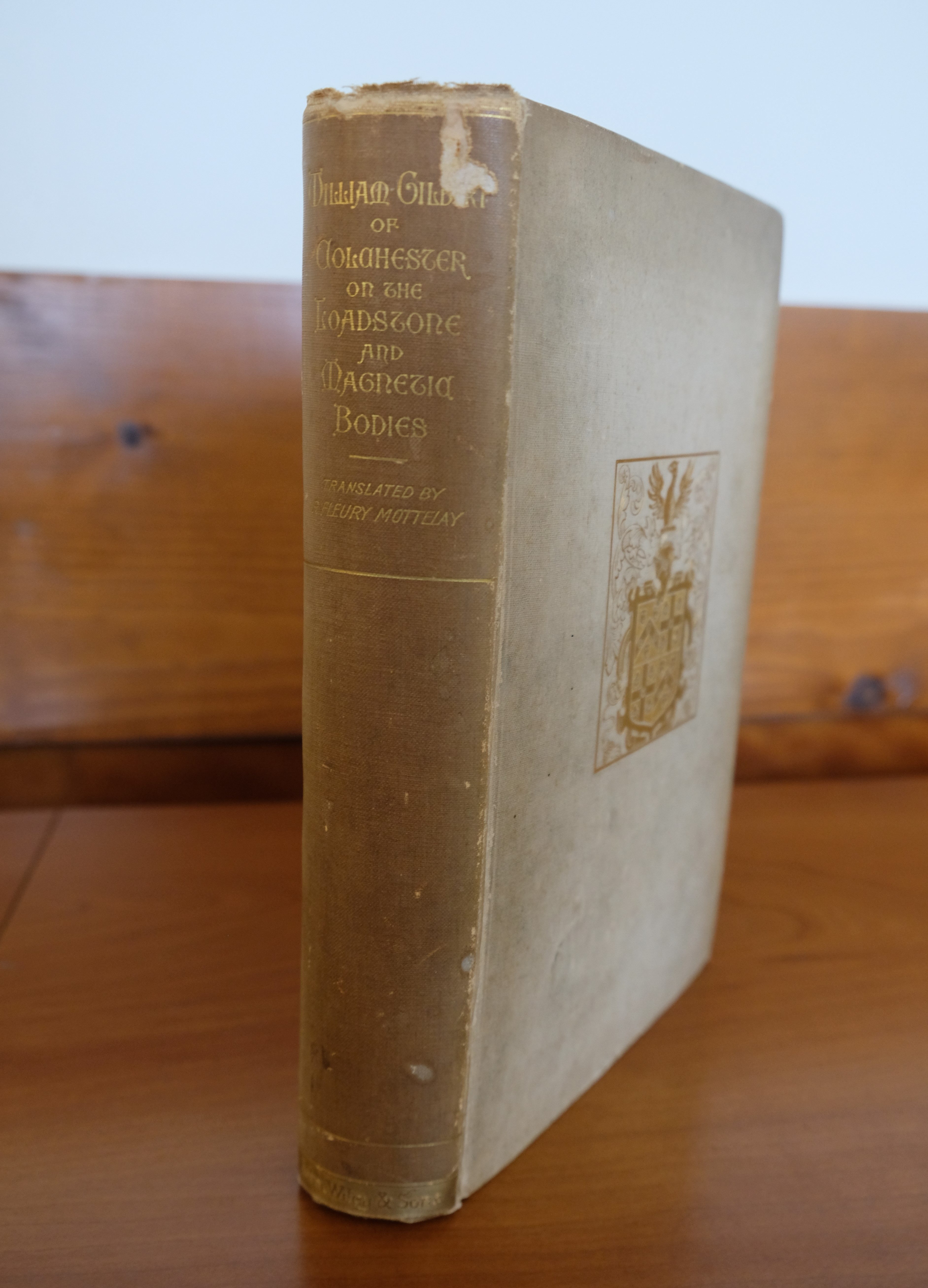

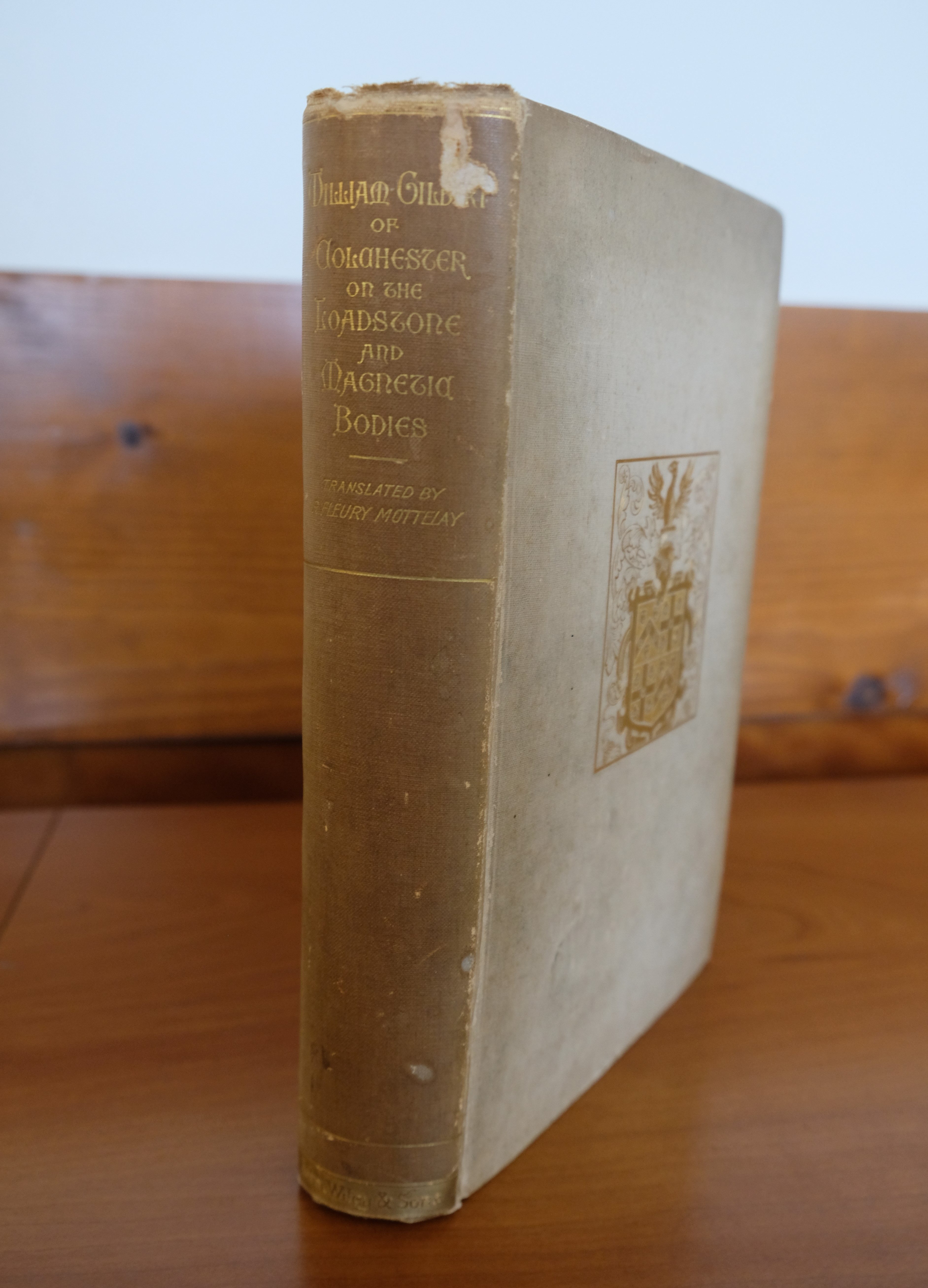

and the Scholastic method of university teaching. He is remembered today largely for his book ''De Magnete

''De Magnete, Magneticisque Corporibus, et de Magno Magnete Tellure'' (''On the Magnet and Magnetic Bodies, and on That Great Magnet the Earth'') is a scientific work published in 1600 by the English physician and scientist William Gilbert. A hi ...

'' (1600).

A unit of magnetomotive force

In physics, the magnetomotive force (abbreviated mmf or MMF, symbol \mathcal F) is a quantity appearing in the equation for the magnetic flux in a magnetic circuit, Hopkinson's law. It is the property of certain substances or phenomena that give ...

, also known as magnetic potential, was named the '' Gilbert'' in his honour; it has now been superseded by the Ampere-turn

The ampere-turn (symbol A⋅t) is the MKS system of units, MKS (metre–kilogram–second) unit of magnetomotive force (MMF), represented by a direct current of one ampere flowing in a single-turn loop. ''Turns'' refers to the winding number of an ...

.

Life and work

Gilbert was born in Colchester to Jerome Gilberd, a boroughrecorder Recorder or The Recorder may refer to:

Newspapers

* ''Indianapolis Recorder'', a weekly newspaper

* ''The Recorder'' (Massachusetts newspaper), a daily newspaper published in Greenfield, Massachusetts, US

* ''The Recorder'' (Port Pirie), a newsp ...

. He was educated at St John's College, Cambridge

St John's College, formally the College of St John the Evangelist in the University of Cambridge, is a Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge, founded by the House of Tudor, Tudor matriarch L ...

. After gaining his MD from Cambridge in 1569, and a short spell as bursar of St John's College, he left to practice medicine in London, and he travelled on the continent. In 1573, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians

The Royal College of Physicians of London, commonly referred to simply as the Royal College of Physicians (RCP), is a British professional membership body dedicated to improving the practice of medicine, chiefly through the accreditation of ph ...

. In 1600, he was elected President of the college.Mottelay, P. Fleury (1893). "Biographical memoir". In He was Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudo ...

's own physician from 1601 until her death in 1603, and James VI and I

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and King of Ireland, Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 M ...

renewed his appointment.

His primary scientific work – much inspired by earlier works of Robert Norman – was '' De Magnete, Magneticisque Corporibus, et de Magno Magnete Tellure'' (''On the Magnet and Magnetic Bodies, and on the Great Magnet the Earth'') published in 1600. In this work, he describes many of his experiments with his model Earth called the terrella

A terrella () is a small magnetised model ball representing the Earth, that is thought to have been invented by the English physician William Gilbert while investigating magnetism, and further developed 300 years later by the Norwegian scientis ...

. From these experiments, he concluded that Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to Planetary habitability, harbor life. This is enabled by Earth being an ocean world, the only one in the Solar System sustaining liquid surface water. Almost all ...

was itself magnetic

Magnetism is the class of physical attributes that occur through a magnetic field, which allows objects to attract or repel each other. Because both electric currents and magnetic moments of elementary particles give rise to a magnetic field, m ...

, and that this was the reason why compass

A compass is a device that shows the cardinal directions used for navigation and geographic orientation. It commonly consists of a magnetized needle or other element, such as a compass card or compass rose, which can pivot to align itself with No ...

es point north (previously, some people believed that it was the pole-star Polaris

Polaris is a star in the northern circumpolar constellation of Ursa Minor. It is designated α Ursae Minoris (Latinisation of names, Latinized to ''Alpha Ursae Minoris'') and is commonly called the North Star or Pole Star. With an ...

, or a large magnetic island on the north pole that attracted the compass). He was the first person to argue that the center of Earth was iron, and he considered an important and related property of magnets, being that they can be cut, each forming a new magnet with north and south poles.

In Book 6, Chapter 3, he argues in support of diurnal rotation though he does not talk about heliocentrism, stating that it is an absurdity to think that the immense celestial spheres

The celestial spheres, or celestial orbs, were the fundamental entities of the cosmological models developed by Plato, Eudoxus, Aristotle, Ptolemy, Copernicus, and others. In these celestial models, the apparent motions of the fixed star ...

(doubting even that they exist) rotate daily, as opposed to the diurnal rotation of the much-smaller Earth. He also posits that the "fixed" stars are at remote variable distances rather than fixed to an imaginary sphere. He states that, situated "in thinnest aether, or in the most subtle fifth essence, or in vacuity – how shall the stars keep their places in the mighty swirl of these enormous spheres composed of a substance of which no one knows aught?"

The English word "electricity" was first used in 1646 by Sir Thomas Browne

Sir Thomas Browne ( "brown"; 19 October 160519 October 1682) was an English polymath and author of varied works which reveal his wide learning in diverse fields including science and medicine, religion and the esoteric. His writings display a d ...

, derived from Gilbert's 1600 Neo-Latin

Neo-LatinSidwell, Keith ''Classical Latin-Medieval Latin-Neo Latin'' in ; others, throughout. (also known as New Latin and Modern Latin) is the style of written Latin used in original literary, scholarly, and scientific works, first in Italy d ...

''electricus'', meaning "like amber

Amber is fossilized tree resin. Examples of it have been appreciated for its color and natural beauty since the Neolithic times, and worked as a gemstone since antiquity."Amber" (2004). In Maxine N. Lurie and Marc Mappen (eds.) ''Encyclopedia ...

". The term had been in use since the 13th century, but Gilbert was the first to use it to mean "like amber in its attractive properties". He recognized that friction with these objects removed a so-called "effluvium", which would cause the attraction effect in returning to the object, though he did not realize that this substance (electric charge

Electric charge (symbol ''q'', sometimes ''Q'') is a physical property of matter that causes it to experience a force when placed in an electromagnetic field. Electric charge can be ''positive'' or ''negative''. Like charges repel each other and ...

) was universal to all materials.

In his book, he also studied static electricity

Static electricity is an imbalance of electric charges within or on the surface of a material. The charge remains until it can move away by an electric current or electrical discharge. The word "static" is used to differentiate it from electric ...

using amber

Amber is fossilized tree resin. Examples of it have been appreciated for its color and natural beauty since the Neolithic times, and worked as a gemstone since antiquity."Amber" (2004). In Maxine N. Lurie and Marc Mappen (eds.) ''Encyclopedia ...

; amber is called ''elektron'' in Greek, so Gilbert decided to call its effect the ''electric force''. He invented the first electrical measuring instrument

Instrumentation is a collective term for measuring instruments, used for indicating, measuring, and recording physical quantities. It is also a field of study about the art and science about making measurement instruments, involving the related ...

, the electroscope

The electroscope is an early scientific instrument used to detect the presence of electric charge on a body. It detects this by the movement of a test charge due to the Coulomb's law, Coulomb electrostatic force on it. The amount of charge on ...

, in the form of a pivoted needle he called the ''versorium The versorium (Latin word for "turn around") was the first electroscope, the first instrument that could detect the presence of static electric charge. It was invented in 1600 by William Gilbert, physician to Queen Elizabeth I.

Description

Th ...

''.

Like other people of his day, he believed that crystal (clear quartz

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica (silicon dioxide). The Atom, atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon–oxygen Tetrahedral molecular geometry, tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tet ...

) was an especially hard form of water, formed from compressed ice:

Gilbert argued that electricity and magnetism were not the same thing. For evidence, he (incorrectly) pointed out that, while electrical attraction disappeared with heat, magnetic attraction did not (although it is proven that magnetism does in fact become damaged and weakened with heat). Hans Christian Ørsted

Hans Christian Ørsted (; 14 August 1777 – 9 March 1851), sometimes Transliteration, transliterated as Oersted ( ), was a Danish chemist and physicist who discovered that electric currents create magnetic fields. This phenomenon is known as ...

and James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell (13 June 1831 – 5 November 1879) was a Scottish physicist and mathematician who was responsible for the classical theory of electromagnetic radiation, which was the first theory to describe electricity, magnetism an ...

showed that both effects were aspects of a single force: electromagnetism. Maxwell surmised this in his ''A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism

''A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism'' is a two-volume treatise on electromagnetism written by James Clerk Maxwell in 1873. Maxwell was revising the ''Treatise'' for a second edition when he died in 1879. The revision was completed by Wil ...

'' after much analysis.

Gilbert's magnetism

Magnetism is the class of physical attributes that occur through a magnetic field, which allows objects to attract or repel each other. Because both electric currents and magnetic moments of elementary particles give rise to a magnetic field, ...

was the invisible force that many other natural philosophers seized upon, incorrectly, as governing the motions that they observed. While not attributing magnetism to attraction among the stars, Gilbert pointed out the motion of the skies was due to Earth's rotation, and not the rotation of the spheres, 20 years before Galileo

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

(but 57 years after Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath who formulated a mathematical model, model of Celestial spheres#Renaissance, the universe that placed heliocentrism, the Sun rather than Earth at its cen ...

, who stated it openly in his work ''De revolutionibus orbium coelestium

''De revolutionibus orbium coelestium'' (English translation: ''On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres'') is the seminal work on the heliocentric theory of the astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) of the Polish Renaissance. The book ...

'', which was published in 1543) (see external reference below). Gilbert made the first attempt to map the surface markings on the Moon in the 1590s. His chart, made without the use of a telescope, showed outlines of dark and light patches on the Moon's face. Contrary to most of his contemporaries, Gilbert believed that the light spots on the Moon were water, and the dark spots were land.

Besides Gilbert's ''De Magnete'', there appeared at Amsterdam in 1651 a quarto volume of 316 pages entitled ''De Mundo Nostro Sublunari Philosophia Nova'' (New Philosophy about our Sublunary World), edited – some say by his brother William Gilbert Junior, and others say, by the eminent English scholar and critic John Gruter – from two manuscripts found in the library of Sir

Besides Gilbert's ''De Magnete'', there appeared at Amsterdam in 1651 a quarto volume of 316 pages entitled ''De Mundo Nostro Sublunari Philosophia Nova'' (New Philosophy about our Sublunary World), edited – some say by his brother William Gilbert Junior, and others say, by the eminent English scholar and critic John Gruter – from two manuscripts found in the library of Sir William Boswell

Sir William Boswell (died 1650) was an English diplomat and politician who sat in the House of Commons in 1624 and 1625. He was a resident ambassador to the Netherlands from 1632 to 1649.

Life

William Boswell was a native of Suffolk. He was edu ...

. According to John Davy, "this work of Gilbert's, which is so little known, is a very remarkable one both in style and matter; and there is a vigor and energy of expression belonging to it very suitable to its originality. Possessed of a more minute and practical knowledge of natural philosophy than Bacon

Bacon is a type of Curing (food preservation), salt-cured pork made from various cuts of meat, cuts, typically the pork belly, belly or less fatty parts of the back. It is eaten as a side dish (particularly in breakfasts), used as a central in ...

, his opposition to the philosophy of the schools was more searching and particular, and at the same time probably little less efficient." In the opinion of Prof. John Robison, ''De Mundo'' consists of an attempt to establish a new system of natural philosophy upon the ruins of the Aristotelian doctrine.

William Whewell

William Whewell ( ; 24 May 17946 March 1866) was an English polymath. He was Master of Trinity College, Cambridge. In his time as a student there, he achieved distinction in both poetry and mathematics.

The breadth of Whewell's endeavours is ...

says in his ''History of the Inductive Sciences'' (1859):

Gilbert, in his work, ''De Magnete'' printed in 1600 has only some vague notions that the magnetic virtue of the earth in some way determines the direction of the earth's axis, the rate of its diurnal rotation, and that of the revolution of the moon about it. Gilbert died in 1603, and in his posthumous work (''De Mundo nostro Sublunari Philosophia nova'', 1631) we have already a more distinct statement of the attraction of one body by another. "The force which emanates from the moon reaches to the earth, and, in like manner, the magnetic virtue of the earth pervades the region of the moon: both correspond and conspire by the joint action of both, according to a proportion and conformity of motions, but the earth has more effect in consequence of its superior mass; the earth attracts and repels, the moon, and the moon within certain limits, the earth; not so as to make the bodies come together, as magnetic bodies do, but so that they may go on in a continuous course." Though this phraseology is capable of representing a good deal of the truth, it does not appear to have been connected... with any very definite notions of mechanical action in detail.Gilbert died on 30 November 1603 in London. His cause of death is thought to have been the

bubonic plague

Bubonic plague is one of three types of Plague (disease), plague caused by the Bacteria, bacterium ''Yersinia pestis''. One to seven days after exposure to the bacteria, flu-like symptoms develop. These symptoms include fever, headaches, and ...

.

Gilbert was buried in his home town, in Holy Trinity Church, Colchester. His marble wall monument can still be seen in this Saxon church, now deconsecrated

Deconsecration, also referred to as decommissioning or ''secularization'' (a term also used for the external confiscation of church property), is the removal of a religious sanction and blessing from something that had been previously consec ...

and used as a café and market.

Commentary on Gilbert

Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626) was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England under King James I. Bacon argued for the importance of nat ...

never accepted Copernican heliocentrism

Copernican heliocentrism is the astronomical scientific modeling, model developed by Nicolaus Copernicus and published in 1543. This model positioned the Sun at the center of the Universe, motionless, with Earth and the other planets orbiting arou ...

, and was critical of Gilbert's philosophical work in support of the diurnal motion of Earth. Bacon's criticism includes the following two statements. The first was repeated in three of his works, namely ''In the Advancement of Learning'' (1605), ''Novum Organum

The ''Novum Organum'', fully ''Novum Organum, sive Indicia Vera de Interpretatione Naturae'' ("New organon, or true directions concerning the interpretation of nature") or ''Instaurationis Magnae, Pars II'' ("Part II of The Great Instauratio ...

'' (1620), and ''De Augmentis'' (1623). The more severe second statement is from ''History of Heavy and Light Bodies'' published after Bacon's death.

The Alchemists have made a philosophy out of a few experiments of the furnace and Gilbert our countryman hath made a philosophy out of observations of the lodestone.

ilberthas himself become a magnet; that is, he has ascribed too many things to that force and built a ship out of a shell.Thomas Thomson writes in his ''History of the Royal Society'' (1812):

The magnetic laws were first generalized and explained by Dr. Gilbert, whose book on magnetism published in 1600, is one of the finest examples of inductive philosophy that has ever been presented to the world. It is the more remarkable, because it preceded the ''Novum Organum'' of Bacon, in which the inductive method of philosophizing was first explained.

William Whewell

William Whewell ( ; 24 May 17946 March 1866) was an English polymath. He was Master of Trinity College, Cambridge. In his time as a student there, he achieved distinction in both poetry and mathematics.

The breadth of Whewell's endeavours is ...

writes in his ''History of the Inductive Sciences'' (1837/1859):

Gilbert... repeatedly asserts the paramount value of experiments. He himself, no doubt, acted up to his own precepts; for his work contains all the fundamental facts of the science f magnetism so fully examined, indeed, that even at this day we have little to add to them.Historian

Henry Hallam

Henry Hallam (9 July 1777 – 21 January 1859) was an English historian. Educated at Eton and Christ Church, Oxford, he practised as a barrister on the Oxford circuit for some years before turning to history. His major works were ''View of th ...

wrote of Gilbert in his ''Introduction to the Literature of Europe in the Fifteenth, Sixteenth, and Seventeenth Centuries'' (1848):

The year 1600 was the first in which England produced a remarkable work in physical science; but this was one sufficient to raise a lasting reputation to its author. Gilbert, a physician, in his Latin treatise on the magnet, not only collected all the knowledge which others had possessed on that subject, but became at once the father of experimental philosophy in this island, and by a singular felicity and acuteness of genius, the founder of theories which have been revived after the lapse of ages, and are almost universally received into the creed of the science. The magnetism of the earth itself, his own original hypothesis, ''nova illa nostra et inaudita de tellure sententia''Walter William Bryant of the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, wrote in his book ''Kepler'' (1920):ur new and unprecedented view of the planet Ur ( or ) was an important Sumerian city-state in ancient Mesopotamia, located at the site of modern Tell el-Muqayyar () in Dhi Qar Governorate, southern Iraq. Although Ur was once a Sea port, coastal city near the mouth of the Euphrates on the ..... was by no means one of those vague conjectures that are sometimes unduly applauded... He relied on the analogy of terrestrial phenomena to those exhibited by what he calls a ''terrella A terrella () is a small magnetised model ball representing the Earth, that is thought to have been invented by the English physician William Gilbert while investigating magnetism, and further developed 300 years later by the Norwegian scientis ...'', or artificial spherical magnet. ...Gilbert was also one of our earliest Copernicans, at least as to the rotation of the earth; and with his usual sagacity inferred, before the invention of the telescope, that there are a multitude of fixed stars beyond the reach of our vision.

When Gilbert of Colchester, in his “New Philosophy,” founded on his researches in magnetism, was dealing with tides, he did not suggest that the moon attracted the water, but that “subterranean spirits and humors, rising in sympathy with the moon, cause the sea also to rise and flow to the shores and up rivers”. It appears that an idea, presented in some such way as this, was more readily received than a plain statement. This so-called philosophical method was, in fact, very generally applied, andKepler Johannes Kepler (27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best known for his laws of p ..., who shared Galileo’s admiration for Gilbert’s work, adopted it in his own attempt to extend the idea of magnetic attraction to the planets.Bryant, Walter William (1920) . The Macmillan Company.

Bibliography

*

**

**

*

*

**

**

*

See also

* History of geomagnetism *List of geophysicists

This is a list of geophysicists, people who made Notability in English Wikipedia, notable contributions to geophysics, whether or not geophysics was their primary field. These include historical figures who laid the foundations for the field of ge ...

*Scientific Revolution

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of History of science, modern science during the early modern period, when developments in History of mathematics#Mathematics during the Scientific Revolution, mathemati ...

References

Further reading

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

The Galileo Project

— biography of William Gilbert.

— website hosted by NASA — ''Commemorating the 400th anniversary of "De Magnete" by William Gilbert of Colchester''.

Online Galleries, History of Science Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries

High resolution images of works by and/or portraits of William Gilbert in .jpg and .tiff format. * *

— Translation of ''De Magnete'' by Silvanus Thompson for the Gilbert Club, London 1900. Full text, free to read and search. Go to page 9 and read Gilbert saying the Earth revolves leading to the motion of the skies.

The Natural Philosophy of William Gilbert and His Predecessors

From th

in the Rare Book and Special Collection Division at the

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is a research library in Washington, D.C., serving as the library and research service for the United States Congress and the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It also administers Copyright law o ...

William Gilbert, the first electrician.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Gilbert, William 16th-century English astronomers 16th-century English medical doctors 16th-century English writers 16th-century English male writers Magneticians People associated with electricity English physicists 1540s births 1603 deaths People of the Elizabethan era 16th-century writers in Latin Alumni of St John's College, Cambridge People from Colchester 17th-century deaths from plague (disease) 17th-century English writers 17th-century English male writers