William Garrow on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir William Garrow, (13 April 1760 – 24 September 1840) was an English

Garrow started as a criminal defence barrister at the

Garrow started as a criminal defence barrister at the

Since 1789, the press had been speculating that Garrow, a Whig, would enter Parliament; however he was first elected in 1805 for Gatton. This was a

Since 1789, the press had been speculating that Garrow, a Whig, would enter Parliament; however he was first elected in 1805 for Gatton. This was a

The Garrow Society

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Garrow, William 1760 births 1840 deaths English barristers Members of Lincoln's Inn Attorneys general for England and Wales Solicitors general for England and Wales Barons of the Exchequer Knights Bachelor Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for constituencies in Cornwall Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for English constituencies Serjeants-at-law (England) UK MPs 1802–1806 UK MPs 1806–1807 UK MPs 1812–1818 Fellows of the Royal Society People from Monken Hadley Politicians from the London Borough of Barnet

barrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdiction (area), jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include arguing cases in courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, jurisprud ...

, politician and judge known for his indirect reform of the advocacy system, which helped usher in the adversarial court system used in most common law

Common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law primarily developed through judicial decisions rather than statutes. Although common law may incorporate certain statutes, it is largely based on prece ...

nations today. He introduced the phrase " presumed innocent until proven guilty", insisting that defendants' accusers and their evidence be thoroughly tested in court. Born to a priest and his wife in Monken Hadley

Monken Hadley is an area in the London Borough of Barnet, at the northern edge of Greater London, England, lying some north north-west of Charing Cross. Anciently a country village near Chipping Barnet in Middlesex, and from 1889 to 1965 in Her ...

, then in Middlesex, Garrow was educated at his father's school in the village before being apprenticed to Thomas Southouse, an attorney in Cheapside

Cheapside is a street in the City of London, the historic and modern financial centre of London, England, which forms part of the A40 road, A40 London to Fishguard road. It links St Martin's Le Grand with Poultry, London, Poultry. Near its eas ...

, which preceded a pupillage

A pupillage, in England and Wales, Northern Ireland, Kenya, Malaysia, Pakistan and Hong Kong, is the final, vocational stage of training for those wishing to become practising barristers. Pupillage is similar to an apprenticeship, during which ba ...

with Mr. Crompton, a special pleader. A dedicated student of the law, Garrow frequently observed cases at the Old Bailey

The Central Criminal Court of England and Wales, commonly referred to as the Old Bailey after the street on which it stands, is a criminal court building in central London, one of several that house the Crown Court of England and Wales. The s ...

; as a result Crompton recommended that he become a solicitor or barrister. Garrow joined Lincoln's Inn

The Honourable Society of Lincoln's Inn, commonly known as Lincoln's Inn, is one of the four Inns of Court (professional associations for Barrister, barristers and judges) in London. To be called to the bar in order to practise as a barrister ...

in November 1778, and was called to the Bar

The call to the bar is a legal term of art in most common law jurisdictions where persons must be qualified to be allowed to argue in court on behalf of another party and are then said to have been "called to the bar" or to have received "call to ...

on 27 November 1783. He quickly established himself as a criminal

In ordinary language, a crime is an unlawful act punishable by a State (polity), state or other authority. The term ''crime'' does not, in modern criminal law, have any simple and universally accepted definition,Farmer, Lindsay: "Crime, definiti ...

defence counsel, and in February 1793 was made a King's Counsel

A King's Counsel (Post-nominal letters, post-nominal initials KC) is a senior lawyer appointed by the monarch (or their Viceroy, viceregal representative) of some Commonwealth realms as a "Counsel learned in the law". When the reigning monarc ...

by HM Government

His Majesty's Government, abbreviated to HM Government or otherwise UK Government, is the central executive authority of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

to prosecute cases involving treason and felonies.

He was elected to Parliament in 1805 for Gatton, a rotten borough

A rotten or pocket borough, also known as a nomination borough or proprietorial borough, was a parliamentary borough or Electoral district, constituency in Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain, or the United Kin ...

, and became Solicitor General for England in 1812 and Attorney General for England a year later. Although not happy in Parliament, having been returned only for political purposes, Garrow acted as one of the principal Whig spokesmen trying to stop criminal law reform as campaigned for by Samuel Romilly and also attempted to pass legislation to condemn animal cruelty. In 1817, he was made a Baron of the Exchequer and a Serjeant-at-Law, forcing his resignation from Parliament, and he spent the next 15 years as a judge. He was not particularly successful in the commercial cases the Exchequer specialised in, but when on Assize

The assizes (), or courts of assize, were periodic courts held around England and Wales until 1972, when together with the quarter sessions they were abolished by the Courts Act 1971 and replaced by a single permanent Crown Court. The assizes ex ...

, used his criminal law knowledge from his years at the Bar to great effect. On his resignation in 1832 he was made a Privy Councillor, a sign of the respect HM Government had for him. He died on 24 September 1840.

For much of the 19th and 20th centuries his work was forgotten by academics, and interest arose only in 1991, with an article by John Beattie titled "Garrow for the Defence" in ''History Today

''History Today'' is a history magazine. Published monthly in London since January 1951, it presents authoritative history to as wide a public as possible. The magazine covers all periods and geographical regions and publishes articles of tradit ...

''. Garrow is best known for his criminal defence work, which, through the example he set with his aggressive defence of clients, helped establish the modern adversarial system in use in the United Kingdom, the United States, and other former British colonies. Garrow is also known for his impact on the rules of evidence, leading to the best evidence rule

The best evidence rule is a legal principle that holds an original of a document as superior evidence. The rule specifies that secondary evidence, such as a copy or facsimile, will be not admissible if an original document exists and can be obtain ...

. His work was cited as recently as 1982 in the Supreme Court of Canada

The Supreme Court of Canada (SCC; , ) is the highest court in the judicial system of Canada. It comprises nine justices, whose decisions are the ultimate application of Canadian law, and grants permission to between 40 and 75 litigants eac ...

and 2006 in the Irish Court of Criminal Appeal. In 2009, BBC One

BBC One is a British free-to-air public broadcast television channel owned and operated by the BBC. It is the corporation's oldest and flagship channel, and is known for broadcasting mainstream programming, which includes BBC News television b ...

broadcast '' Garrow's Law'', a four-part fictionalised drama of Garrow's beginnings at the Old Bailey

The Central Criminal Court of England and Wales, commonly referred to as the Old Bailey after the street on which it stands, is a criminal court building in central London, one of several that house the Crown Court of England and Wales. The s ...

; a second series aired in late 2010. BBC One began broadcasting the third series in November 2011.

Early life and education

Garrow's family originally came fromMoray

Moray ( ; or ) is one of the 32 council areas of Scotland. It lies in the north-east of the country, with a coastline on the Moray Firth, and borders the council areas of Aberdeenshire and Highland. Its council is based in Elgin, the area' ...

, Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

, where they were descended from the Garriochs of Kinstair, a Scottish royal line. Garrow's father David was born at a farm called Knockside, Aberlour (Speyside) approximately 50 miles northwest of Aberdeen

Aberdeen ( ; ; ) is a port city in North East Scotland, and is the List of towns and cities in Scotland by population, third most populous Cities of Scotland, Scottish city. Historically, Aberdeen was within the historic county of Aberdeensh ...

.Braby (2010), p. 17. David graduated from Aberdeen University with a Master of Arts

A Master of Arts ( or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA or AM) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Those admitted to the degree have ...

degree on 1 April 1736, and became a priest of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

, creating a school in Monken Hadley

Monken Hadley is an area in the London Borough of Barnet, at the northern edge of Greater London, England, lying some north north-west of Charing Cross. Anciently a country village near Chipping Barnet in Middlesex, and from 1889 to 1965 in Her ...

, in what's now the Greater London

Greater London is an administrative area in England, coterminous with the London region, containing most of the continuous urban area of London. It contains 33 local government districts: the 32 London boroughs, which form a Ceremonial count ...

area. His younger brother William became a successful doctor, leaving most of his estate (£30,000) to Garrow. On 5 June 1748 David married Sarah Lowndes, with whom he had eleven children; William, Edward, Eleanora, Jane, John, Rose, William, Joseph, William, David and Anne. The first two Williams died as infants; the third, born on 13 April 1760, survived.

William Garrow was educated at his father's school in Monken Hadley, The Priory, which emphasised preparing students for commercial careers such as in the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company that was founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to Indian Ocean trade, trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (South A ...

. As such, it taught social graces, as well as English, Greek, Latin, French, geography, mathematics and dancing. Studying there Garrow "knew the English language well; had a moderate acquaintance with the Latin and, as an accomplishment, added a considerable proficiency in French". Garrow attended this school until he was 15, at which point he was articled to Thomas Southouse born Faversham, Kent?, an attorney in Cheapside

Cheapside is a street in the City of London, the historic and modern financial centre of London, England, which forms part of the A40 road, A40 London to Fishguard road. It links St Martin's Le Grand with Poultry, London, Poultry. Near its eas ...

, London. Garrow showed potential, being noted as "attentive and diligent in the performance of the technical and practical duties of the office", and Southouse recommended that he become a solicitor or barrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdiction (area), jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include arguing cases in courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, jurisprud ...

; as a result, when he was 17, he became a pupil of a Mr. Crompton, a special pleader. As a pupil Garrow studied hard, fastidiously reading Sampson Euer's ''Doctrina Placitandi'', a manual on the Law of Pleading written in legal French. At the same time he viewed cases at the Old Bailey

The Central Criminal Court of England and Wales, commonly referred to as the Old Bailey after the street on which it stands, is a criminal court building in central London, one of several that house the Crown Court of England and Wales. The s ...

, forming a friendship with the clerk of arraignment there, William Shelton.

In the 18th century, speakers perfected the art of oratory through debating societies, one of the most noted of which met at Coachmaker's Hall, London. Although initially shy (during his first debate, the attendees had to force him from his seat and hold him up while he spoke), he swiftly developed a reputation as a speaker, and was referred to in the press as "Counsellor Garrow, the famous orator of Coachmaker's Hall". In November 1778, Garrow became a member of Lincoln's Inn

The Honourable Society of Lincoln's Inn, commonly known as Lincoln's Inn, is one of the four Inns of Court (professional associations for Barrister, barristers and judges) in London. To be called to the bar in order to practise as a barrister ...

, one of the four Inns of Court

The Inns of Court in London are the professional associations for barristers in England and Wales. There are four Inns of Court: Gray's Inn, Lincoln's Inn, Inner Temple, and Middle Temple.

All barristers must belong to one of them. They have s ...

, and on 27 November 1783 at the age of 23 he was called to the Bar

The call to the bar is a legal term of art in most common law jurisdictions where persons must be qualified to be allowed to argue in court on behalf of another party and are then said to have been "called to the bar" or to have received "call to ...

; he later became a Bencher

A bencher or Master of the Bench is a senior member of an Inn of Court in England and Wales or the Inns of Court in Northern Ireland, or the Honorable Society of King's Inns in Ireland. Benchers hold office for life once elected. A bencher c ...

of Lincoln's Inn in 1793.

Career as a barrister

Defence

Garrow started as a criminal defence barrister at the

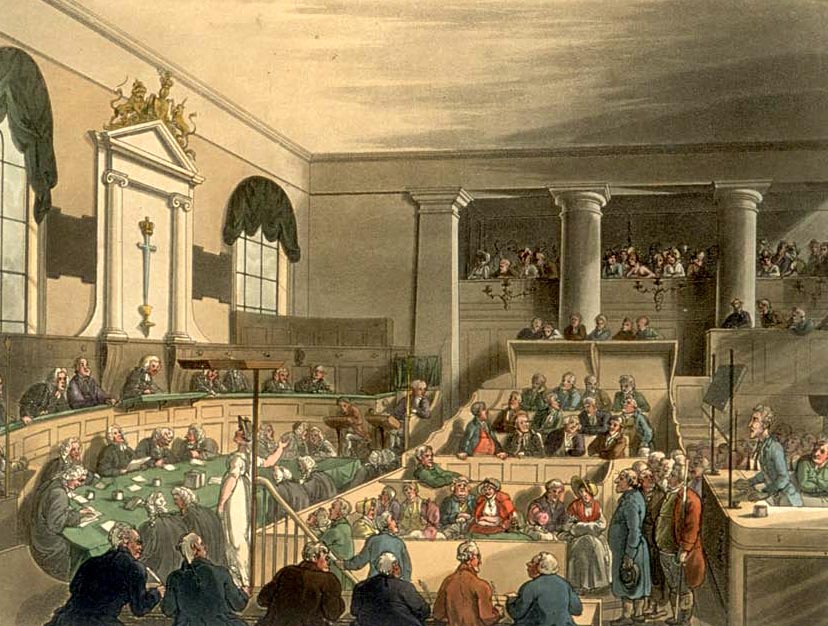

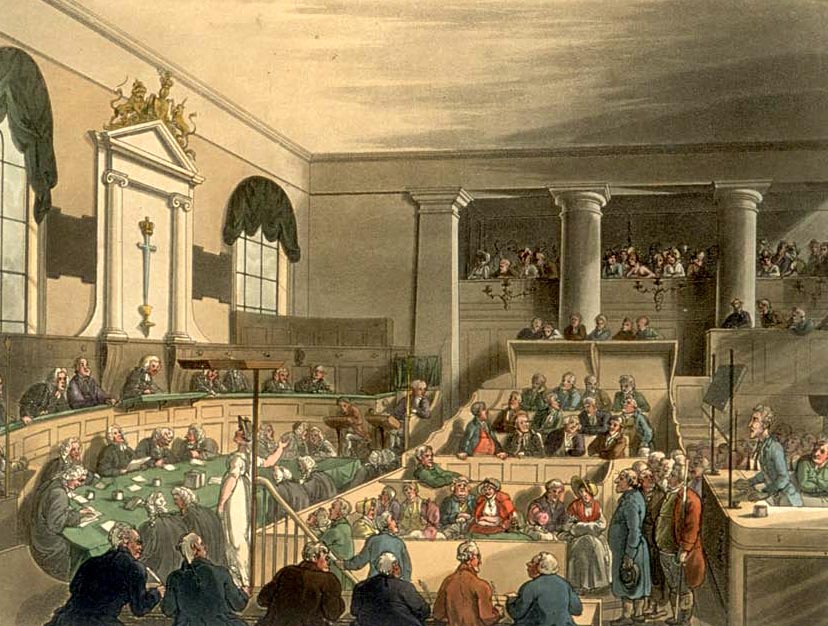

Garrow started as a criminal defence barrister at the Old Bailey

The Central Criminal Court of England and Wales, commonly referred to as the Old Bailey after the street on which it stands, is a criminal court building in central London, one of several that house the Crown Court of England and Wales. The s ...

, in a time where many defendants became increasingly reliant on barristers to prevent their conviction. His first case was actually as a prosecutor; on 14 January 1784, barely two months after he was called to the Bar

The call to the bar is a legal term of art in most common law jurisdictions where persons must be qualified to be allowed to argue in court on behalf of another party and are then said to have been "called to the bar" or to have received "call to ...

, he prosecuted John Henry Aikles for obtaining a bill of exchange

A negotiable instrument is a document guaranteeing the payment of a specific amount of money, either on demand, or at a set time, whose payer is usually named on the document. More specifically, it is a document contemplated by or consisting of a ...

under false pretences. It was alleged that Aikles had promised to pay Samuel Edwards £100 and a small commission for a £100 bill of exchange, and when he took the bill, failed to hand over the money. Despite Aikles's counsel claiming, according to Edward Foss, that "this was no felony", and being represented by two of the most prestigious criminal barristers of the day, Garrow convinced both the judge and the jury that Aikles was guilty. Garrow later defended Aikles in September 1785, securing his release due to ill-health.

During his early years as a practising barrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdiction (area), jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include arguing cases in courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, jurisprud ...

, Garrow was particularly noted for his aggressive and confrontational style of cross-examination. When James Wingrove was charged with theft and violence in the course of a highway robbery in 1784, Garrow's cross-examination of William Grove (who acted as a witness and the person charging Wingrove) got him to admit that he was perjuring himself in an attempt to get a reward, and that Wingrove had not robbed the two injured parties. Garrow showed a dislike of most thief-takers, of which Grove was one, although he did not treat the Bow Street Runners

The Bow Street Runners were the law enforcement officers of the Bow Street Magistrates' Court in the City of Westminster. They have been called London's first professional police force. The force originally numbered six men and was founded in 1 ...

and other professionals with contempt. His dislike of such men was highlighted in his defence of three men in 1788 for theft; they were charged with assaulting John Troughton, putting him in fear of his life, and stealing his hat. The issue was whether the assault put him in fear of his life, or whether he was exaggerating to claim a reward, which could not be claimed for simple theft. Garrow established that Troughton was uncertain about how he lost his hat, despite his attempts to claim that the defendants knocked it off him, and after four witnesses gave character evidence the defendants were found not guilty.

Garrow made much use of jury nullification

Jury nullification, also known as jury equity or as a perverse verdict, is a decision by the jury in a trial, criminal trial resulting in a verdict of Acquittal, not guilty even though they think a defendant has broken the law. The jury's reas ...

to limit the punishment for his convicted clients, in a time when many crimes carried the death penalty (the so-called Bloody Code

The "Bloody Code" was a series of laws in England, Wales and Ireland in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries which mandated the death penalty for a wide range of crimes. It was not referred to by this name in its own time; the name was g ...

). In 1784 a pair of women were arrested for stealing fans worth 15 shillings, meaning a conviction would result in the death penalty; Garrow convinced the jury to convict the women of stealing 4 shillings worth of fans, therefore changing the sentence to twelve months of hard labour.

Prosecution

Garrow soon developed a large practice, working criminal trials at theOld Bailey

The Central Criminal Court of England and Wales, commonly referred to as the Old Bailey after the street on which it stands, is a criminal court building in central London, one of several that house the Crown Court of England and Wales. The s ...

and outside London as both defence counsel and prosecutor. By 1799, a book recorded that the number of cases he had at the Court of King's Bench

The Court of King's Bench, formally known as The Court of the King Before the King Himself, was a court of common law in the English legal system. Created in the late 12th to early 13th century from the '' curia regis'', the King's Bench initi ...

"is exceeded by none but Mr. homas

In Indian religions, a homa (Sanskrit: होम), also known as havan, is a fire ritual performed on special occasions. In Hinduism, by a Hindu priest usually for a homeowner ("grihastha": one possessing a home). The grihasth keeps different ...

Erskine's", and that "he has long monopolized the chief business on the home circuit... No man is heard with more attention by the court, no man gains more upon a jury, or better pleases a common auditor". In February 1793 he was appointed a King's Counsel

A King's Counsel (Post-nominal letters, post-nominal initials KC) is a senior lawyer appointed by the monarch (or their Viceroy, viceregal representative) of some Commonwealth realms as a "Counsel learned in the law". When the reigning monarc ...

to help prosecute those accused of treason and sedition, less than ten years after his call to the Bar

The call to the bar is a legal term of art in most common law jurisdictions where persons must be qualified to be allowed to argue in court on behalf of another party and are then said to have been "called to the bar" or to have received "call t ...

; and his appointment was met with a mixed response from the press. ''The Briton'' described Garrow and the other five appointments as the best talent of the age, while the ''Morning Chronicle

''The Morning Chronicle'' was a newspaper founded in 1769 in London. It was notable for having been the first steady employer of essayist William Hazlitt as a political reporter and the first steady employer of Charles Dickens as a journalist. It ...

'' was bitter due to Garrow's previous status as a friend of the Official Opposition

Parliamentary opposition is a form of political opposition to a designated government, particularly in a Westminster-based parliamentary system. This article uses the term ''government'' as it is used in Parliamentary systems, i.e. meaning ''t ...

, the Whigs, as opposed to the Tory

A Tory () is an individual who supports a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalist conservatism which upholds the established social order as it has evolved through the history of Great Britain. The To ...

government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive (government), execu ...

.

As the French Revolution and its perceived threat to the United Kingdom gained momentum, so did Garrow's career; he prosecuted in most of the state trials, and as he increased in experience was left to manage many of them himself, coming up against leading barristers such as Thomas Erskine, James Mingay and James Scarlett. In May 1794 the Government suspended ''habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a legal procedure invoking the jurisdiction of a court to review the unlawful detention or imprisonment of an individual, and request the individual's custodian (usually a prison official) to ...

'', in 1795 outlawed all public meetings, in 1797 outlawed secret organisations and in 1799 outlawed all societies interested in reforming the way the United Kingdom was run. The Government planned a series of 800 arrests, with 300 execution warrants for high treason made out and signed, making a particular effort to prosecute Thomas Hardy

Thomas Hardy (2 June 1840 – 11 January 1928) was an English novelist and poet. A Literary realism, Victorian realist in the tradition of George Eliot, he was influenced both in his novels and in his poetry by Romanticism, including the poetry ...

and John Horne Tooke

John Horne Tooke (25 June 1736 – 18 March 1812), known as John Horne until 1782 when he added the surname of his friend William Tooke to his own, was an English clergyman, politician and Philology, philologist. Associated with radical proponen ...

. Hardy was the first to be tried, with the prosecution arguing that he sought a revolution in England similar to that in France. With Garrow prosecuting and Erskine defending, the trial lasted eight days instead of the normal one, and the foreman of the jury was so tense that he delivered the verdict of "not guilty" in a whisper and then immediately fainted. Tooke was then prosecuted; again, the jury found him not guilty, with the result that the other 800 trials were abandoned.

During the period when Garrow worked as a barrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdiction (area), jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include arguing cases in courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, jurisprud ...

, the slavocracy

A slavocracy (from ''slave'' + '' -ocracy'') is a society primarily ruled by a class of slaveholders, such as those in the southern United States and their confederacy during the American Civil War. The term was initially coined in the 1830s ...

of the British West Indies

The British West Indies (BWI) were the territories in the West Indies under British Empire, British rule, including Anguilla, the Cayman Islands, the Turks and Caicos Islands, Montserrat, the British Virgin Islands, Bermuda, Antigua and Barb ...

held large amounts of power in Parliament, allowing them to maintain a monopoly on the sugar trade in Britain which produced a vast amount of profit. This industry was profitable due to the use of Black slave labour, to which Garrow had long been opposed; when the members of the pro-slavocracy West India Committee

The West India Committee is a British-based organisation promoting ties and trade with the Caribbean. It operates as a UK-registered charity and NGO (non-governmental organisation) "whose object is to promote the interests of agriculture, manufactu ...

offered him a job managing their legal and political affairs, he replied that "ven

Venezuela, officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in the Caribbean Sea. It comprises an area of , and its popul ...

if your committee would give me their whole incomes, and all their estates, I would not be seen as the advocate of practices which I abhor, and a system which I detest". In 1806, Thomas Picton

Lieutenant-General Sir Thomas Picton (24 August 175818 June 1815) was a British Army officer and colonial administrator. He fought in the Napoleonic Wars and died at Waterloo. According to the historian Alessandro Barbero, Picton was "respecte ...

, the governor of Trinidad, was charged with a single count of "causing torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons including corporal punishment, punishment, forced confession, extracting a confession, interrogational torture, interrogation for information, or intimid ...

to be unlawfully inflicted" on 14-year old free woman of color Luisa Calderón; he was brought before the Court of King's Bench

The Court of King's Bench, formally known as The Court of the King Before the King Himself, was a court of common law in the English legal system. Created in the late 12th to early 13th century from the '' curia regis'', the King's Bench initi ...

under Lord Ellenborough. The court records run to 367 pages, and Garrow was deeply involved as prosecuting counsel; indeed, his opening speech on 24 February 1806 is considered by Braby to be one of his best. The case centred on whether or not Spanish law, which allowed torture, was still in effect at the time of the incident. The jury eventually decided that it was not, and Ellenborough found Picton guilty. Picton's counsel requested a retrial, which was granted; the jury in the second trial eventually decided that Picton was innocent.

Thanks to Garrow's political connections, he was made first Solicitor General

A solicitor general is a government official who serves as the chief representative of the government in courtroom proceedings. In systems based on the English common law that have an attorney general or equivalent position, the solicitor general ...

and then Attorney General for the Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales (, ; ) is a title traditionally given to the male heir apparent to the History of the English monarchy, English, and later, the British throne. The title originated with the Welsh rulers of Kingdom of Gwynedd, Gwynedd who, from ...

in 1806 and 1807; he was recommended by Erskine, who said in a letter to the Prince that "he knows more of the real justice and policy of everything connected with the criminal law than any man I am acquainted with". In 1812 he prosecuted Leigh Hunt

James Henry Leigh Hunt (19 October 178428 August 1859), best known as Leigh Hunt, was an English critic, essayist and poet.

Hunt co-founded '' The Examiner'', a leading intellectual journal expounding radical principles. He was the centre ...

for seditious libel against the Prince Regent

George IV (George Augustus Frederick; 12 August 1762 – 26 June 1830) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from 29 January 1820 until his death in 1830. At the time of his accession to the throne, h ...

; thanks to his work, Hunt was found guilty, reversing the judgment of an 1811 trial in which he had been acquitted.

Political career

Since 1789, the press had been speculating that Garrow, a Whig, would enter Parliament; however he was first elected in 1805 for Gatton. This was a

Since 1789, the press had been speculating that Garrow, a Whig, would enter Parliament; however he was first elected in 1805 for Gatton. This was a rotten borough

A rotten or pocket borough, also known as a nomination borough or proprietorial borough, was a parliamentary borough or Electoral district, constituency in Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain, or the United Kin ...

, with Garrow appointed to serve the interests of his patron, Charles James Fox

Charles James Fox (24 January 1749 – 13 September 1806), styled ''The Honourable'' from 1762, was a British British Whig Party, Whig politician and statesman whose parliamentary career spanned 38 years of the late 18th and early 19th centurie ...

. After his entry into politics Garrow at first paid little attention, not making his maiden speech until 22 April 1806, when he opposed a charge for the impeachment

Impeachment is a process by which a legislative body or other legally constituted tribunal initiates charges against a public official for misconduct. It may be understood as a unique process involving both political and legal elements.

In Eur ...

of Marquess Wellesley

A marquess (; ) is a Nobility, nobleman of high hereditary rank in various European peerages and in those of some of their former colonies. The German-language equivalent is Markgraf (margrave). A woman with the rank of a marquess or the wife ...

. He spoke again on 18 June 1806 on a legal technicality, and after that did not intervene for another six years. Braby and other sources indicate that he did not enjoy his time in Parliament, and was rarely there unless required to conduct some business.

In June 1812, he was appointed Solicitor General for England, receiving the customary knighthood, and, in May 1813, he was appointed Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general (: attorneys general) or attorney-general (AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have executive responsibility for law enf ...

. The Attorney General was the senior Crown prosecutor, during a time when the Prince Regent

A prince regent or princess regent is a prince or princess who, due to their position in the line of succession, rules a monarchy as regent in the stead of a monarch, e.g., as a result of the sovereign's incapacity (minority or illness) or ab ...

feared liberal changes to the criminal law and Parliamentary structure. Garrow, as "a mere creature of the Regent", could be trusted to oppose this; rather than the progressive, defensive work undertaken in his early career, this period was one of conservative aggression against the reformers. Garrow ran particularly foul of Sir Samuel Romilly, who was one of those looking to reform a penal code many claimed was not working. On 5 April 1813, Romilly's Bill on Attainder of Treason and Felony came before Parliament. Its intent was to remove corruption of the blood from cases involving treason and felony; Garrow, then Solicitor General, declared that the Bill would remove one of the safeguards of the British Constitution. The Bill eventually failed, and corruption of the blood was not removed from English law until the Forfeiture Act 1870

The Forfeiture Act 1870 ( 33 & 34 Vict. c. 23) or the Abolition of Forfeiture Act 1870 or the Felony Act 1870 is a British act of Parliament that abolished the automatic forfeiture of goods and land as a punishment for treason and felony. It d ...

. He also served as Chief Justice of Chester

The Justice of Chester was the chief judicial authority for the county palatine of Chester, from the establishment of the county until the abolition of the Great Sessions in Wales and the palatine judicature in 1830.

Within the County Palatine ( ...

from 1814 to 1817.

Garrow also became involved in the repeal of the Corn Laws

The Corn Laws were tariffs and other trade restrictions on imported food and corn enforced in the United Kingdom between 1815 and 1846. The word ''corn'' in British English denotes all cereal grains, including wheat, oats and barley. The la ...

, voting for the measure, and sponsored legislation to control surgical practice in the United Kingdom; the bill did not, however, pass into law. In the early 19th century animal cruelty was widespread; Garrow was one of those who found it appalling, and sponsored a bill in 1816 to increase the penalties for riding horses until their severe injury or death. While defeated, his actions were vindicated by a bill of 1820 introduced by Thomas Erskine, which was given the Royal Assent

Royal assent is the method by which a monarch formally approves an act of the legislature, either directly or through an official acting on the monarch's behalf. In some jurisdictions, royal assent is equivalent to promulgation, while in othe ...

and came into law. Garrow eventually resigned as Attorney General and as a member of parliament in 1817, when he was appointed one of the Barons of the Exchequer

The Barons of the Exchequer, or ''barones scaccarii'', were the judges of the English court known as the Exchequer of Pleas. The Barons consisted of a Chief Baron of the Exchequer and several puisne (''inferior'') barons. When Robert Shute was a ...

.

Judicial career

Garrow's first judicial appointment came in 1814, when he was madeChief Justice of Chester

The Justice of Chester was the chief judicial authority for the county palatine of Chester, from the establishment of the county until the abolition of the Great Sessions in Wales and the palatine judicature in 1830.

Within the County Palatine ( ...

. This was opposed by Sir Samuel Romilly, who argued that the positions of Chief Justice and Attorney General were incompatible, saying "to appoint a gentleman holding a lucrative office at the sole pleasure of the Crown to a high judicial situation, was extremely inconsistent with that independence of the judicial character which it was so important to preserve inviolate". On 6 May 1817, Garrow was made a Baron of the Exchequer and Serjeant-at-Law, succeeding Richard Richards, and resigning his seat in Parliament and his position as Attorney General. He was not a particularly distinguished judge in the Exchequer, mainly due to a lack of knowledge of the finer points of law. Practising on the Assize Circuits, however, was a different matter; dealing with his more familiar criminal law rather than the commercial law of the Exchequer, Garrow performed far better. Braby indicates that he regularly amazed both barrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdiction (area), jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include arguing cases in courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, jurisprud ...

s and defendants with his knowledge of the intricacies of crime. Garrow retired on 22 February 1832, replaced by John Gurney, and was made a Privy Councillor on retirement as a measure of the Government's respect for him. He died at home on 14 September 1840, aged 80.

Personal life

Garrow had an irregular relationship with Sarah Dore, who had previously borne a son, William Arthur Dore Hill, by Arthur Hill, Viscount Fairford in 1778. Thomas Hague has suggested that Dore was an Irish noblewoman Garrow had seduced, but the only intent of his writings was to disparage Garrow, and there is no evidence to support his claim. Their first child, David William Garrow, was born on 15 April 1781, and their second, Eliza Sophia Garrow, was born on 18 June 1784. Garrow and Dore finally married on 17 March 1793. Sarah was noted as particularly elegant, and was actively involved in local matters inRamsgate

Ramsgate is a seaside resort, seaside town and civil parish in the district of Thanet District, Thanet in eastern Kent, England. It was one of the great English seaside towns of the 19th century. In 2021 it had a population of 42,027. Ramsgate' ...

, where the family lived. She died on 30 June 1808 after a long illness, and was buried at the Church of St Margaret, Darenth. David William Garrow was educated at Christ Church, Oxford

Christ Church (, the temple or house, ''wikt:aedes, ædes'', of Christ, and thus sometimes known as "The House") is a Colleges of the University of Oxford, constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Founded in 1546 by Henry V ...

, earning the degree of Doctor of Divinity

A Doctor of Divinity (DD or DDiv; ) is the holder of an advanced academic degree in divinity (academic discipline), divinity (i.e., Christian theology and Christian ministry, ministry or other theologies. The term is more common in the Englis ...

, and served as one of the Chaplains to the Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales (, ; ) is a title traditionally given to the male heir apparent to the History of the English monarchy, English, and later, the British throne. The title originated with the Welsh rulers of Kingdom of Gwynedd, Gwynedd who, from ...

. His son, Edward Garrow, was a cricketer and clergyman. Eliza Sophia Garrow married Samuel Fothergill Lettsom; one of her children, also named William Garrow, served as the Consul-General of Uruguay

Uruguay, officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay, is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast, while bordering the Río de la Plata to the south and the A ...

.

Legacy

Garrow's estate was valued at £22,000 after his death near Ramsgate, Kent, including £12,000 in theBank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the Kingdom of England, English Government's banker and debt manager, and still one ...

, £5,000 in three insurance policies and £5,000 secured by mortgages – a total of £ in terms. Garrow's will was written in 1830 and contained only two demands; to set up a trust and to be buried in his birthplace, Hadley, with his uncle, his father's younger brother William (who had left Garrow the best part of his fortune). The trust contained his entire estate, with the trustees being Leonard Smith, a merchant, Edward Lowth Badeley of Paper Buildings, Inner Temple

The Honourable Society of the Inner Temple, commonly known as the Inner Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court and is a professional association for barristers and judges. To be called to the Bar and practice as a barrister in England and Wa ...

and William Nanson Lettsom of Gray's Inn

The Honourable Society of Gray's Inn, commonly known as Gray's Inn, is one of the four Inns of Court (professional associations for barristers and judges) in London. To be called to the bar in order to practise as a barrister in England and Wale ...

.Braby (2010), p. 158. The money was divided between Joseph Garrow, Garrow's nephew, who received £1,000, £200 to each of the children of Garrow's sister, £2,000 to the sister and £300 a year to the widow of Garrow's son. Eliza, Garrow's daughter, received £300 a year from the interest on the trust, with an additional provision of £200 for the joint use of Eliza and her husband. The estate was structured by a legal professional, and as such no death duties were paid. The second instruction was ignored: Garrow was buried in the churchyard of St Laurence, Ramsgate, his parish church.

Edward Foss described him as "one of the most successful advocates of his day", something linked more to his "extraordinary talent" at cross-examination than his knowledge of the law; Garrow once told a witness before a case that "you know a particular fact and wish to conceal it – I'll get it out of you!" Lord Brougham

Henry Peter Brougham, 1st Baron Brougham and Vaux, (; 19 September 1778 – 7 May 1868) was a British statesman who became Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain and played a prominent role in passing the Reform Act 1832 and Slavery ...

, who regularly opposed him in court, wrote that "no description can give the reader an adequate idea of this eminent practitioner's powers in thus dealing with a witness". Lemmings notes Garrow as not only a formidable advocate but also the "first lawyer to establish a reputation as a defence barrister".

Garrow was largely forgotten; although Robert Louis Stevenson

Robert Louis Stevenson (born Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson; 13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was a Scottish novelist, essayist, poet and travel writer. He is best known for works such as ''Treasure Island'', ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll ...

and his wife discovered his work a generation later when reading transcripts of Old Bailey cases, there was little academic work on him until the late 20th century. In 1991, John Beattie published "Garrow for the Defence" in ''History Today

''History Today'' is a history magazine. Published monthly in London since January 1951, it presents authoritative history to as wide a public as possible. The magazine covers all periods and geographical regions and publishes articles of tradit ...

'', followed by "Scales of Justice: Defence Counsel and the English Criminal Law in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries" in ''Law and History Review''. Allyson May, who did her doctoral study under Beattie, further extended the analysis of Garrow's work with ''The Bar and the Old Bailey: 1750–1850'', published in 2003.

Garrow's work was cited in court as recently as 1982, when the Supreme Court of Canada

The Supreme Court of Canada (SCC; , ) is the highest court in the judicial system of Canada. It comprises nine justices, whose decisions are the ultimate application of Canadian law, and grants permission to between 40 and 75 litigants eac ...

quoted a passage from ''The Trial of William Davidson and Richard Tidd for High Treason'', where Garrow instructed the jury as to how to interpret testimony, in ''Vetrovec v The Queen'' in 1982. In 2006 he was again quoted, when the Irish Court of Criminal Appeal used the same work in their review of the 1982 conviction of Brian Meehan for the murder of Veronica Guerin

Veronica Guerin Turley (5 July 1959 – 26 June 1996) was an Irish investigative journalist focusing on organised crime in Ireland, who was murdered in a contract killing believed to have been ordered by a South Dublin-based drug cartel. Bor ...

.

In 2009, BBC One

BBC One is a British free-to-air public broadcast television channel owned and operated by the BBC. It is the corporation's oldest and flagship channel, and is known for broadcasting mainstream programming, which includes BBC News television b ...

broadcast '' Garrow's Law'', a four-part fictionalised drama of Garrow's beginnings at the Old Bailey

The Central Criminal Court of England and Wales, commonly referred to as the Old Bailey after the street on which it stands, is a criminal court building in central London, one of several that house the Crown Court of England and Wales. The s ...

, starring Andrew Buchan

Andrew Neil Buchan is an English actor and writer. He is known for his roles as DI James Marsh in the ITV drama '' Code of Silence'' (2025), ITV drama ''Broadchurch'' (2013–17), Scott Foster in the BBC political drama '' Party Animals'' (2 ...

as Garrow. A second series, again of four parts, was aired in late 2010, and the third and final four-part series was broadcast in November and December 2011.

Impact

Adversarial system

It is indisputable that Garrow massively affected the modern, adversarial court system used in several western nations and the rules of evidence, although he was barely aware of it. Prior to Garrow's time, defendants in felony cases were not allowed to have defence counsel; as a result, every defendant for arson, rape, robbery, murder and most forms of theft was forced to defend themselves. The first step away from this was with the Treason Act 1695 (for regulating trials in cases of treason), which allowed treason defendants the right to a counsel. Garrow's practice was a further step forward; with his aggressive and forthright style of cross-examination, he promoted a more committed defence of clients, and indirectly reformed the process of advocacy in the 18th century. His area of advocacy (he was counsel for the defence in 83% of his cases) and style is considered key by Beattie in establishing the "new school" of advocacy; his aggressive style in defence set a new style for advocates to follow that assisted in counteracting a legal system biased against the defendant. While he was not the sole cause of this reform, his position at the head of the Bar meant that he served as a highly visible example for new barristers to take after. In some ways Garrow was far ahead of his time; he coined the phrase "innocent until proven guilty

The presumption of innocence is a legal principle that every person accused of any crime is considered innocent until proven guilty. Under the presumption of innocence, the legal burden of proof is thus on the prosecution, which must present co ...

" in 1791, although the jury refused to accept this principle and it was not confirmed by the courts until much later.

Evidence

Garrow also influenced the rules of evidence, which were only just beginning to evolve when he started his career. His insistence that hearsay and copied documents could not be admitted in evidence led to thebest evidence rule

The best evidence rule is a legal principle that holds an original of a document as superior evidence. The rule specifies that secondary evidence, such as a copy or facsimile, will be not admissible if an original document exists and can be obtain ...

. He was crucial in insisting on the autonomy of lawyers when adducing evidence

Evidence for a proposition is what supports the proposition. It is usually understood as an indication that the proposition is truth, true. The exact definition and role of evidence vary across different fields. In epistemology, evidence is what J ...

, in one case openly arguing with the trial judge to insist that the advocates have independence in submitting it. During this period, the use of partisan medical experts was particularly problematic. While medical experts were regularly called at the Old Bailey

The Central Criminal Court of England and Wales, commonly referred to as the Old Bailey after the street on which it stands, is a criminal court building in central London, one of several that house the Crown Court of England and Wales. The s ...

, the use of partisan experts was resisted, and at the beginning experts were given limited authority. While this increased towards the end of the 17th century, in line with the judges' increasing desire for certainty and facts, Garrow is noted as an excellent example of the attitude lawyers took when cross-examining such witnesses. When defending Robert Clark, accused of killing John Delew by kicking him in the stomach, Garrow used a mixture of aggressive cross-examination and medical knowledge to get the prosecution's medical expert to admit that he could not prove how Delew had died. Garrow and later advocates learned how to effectively "interrogate" such witnesses, strengthening their own arguments (when it was their expert) or demolishing those of others (when it was an expert attached to the other side).Landsman (1998), p. 499.

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

The Garrow Society

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Garrow, William 1760 births 1840 deaths English barristers Members of Lincoln's Inn Attorneys general for England and Wales Solicitors general for England and Wales Barons of the Exchequer Knights Bachelor Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for constituencies in Cornwall Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for English constituencies Serjeants-at-law (England) UK MPs 1802–1806 UK MPs 1806–1807 UK MPs 1812–1818 Fellows of the Royal Society People from Monken Hadley Politicians from the London Borough of Barnet