Welsh Kingdoms on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Wales in the early Middle Ages covers the time between the Roman departure from

Wales in the early Middle Ages covers the time between the Roman departure from

In the late fourth century there was an influx of settlers from southern

In the late fourth century there was an influx of settlers from southern

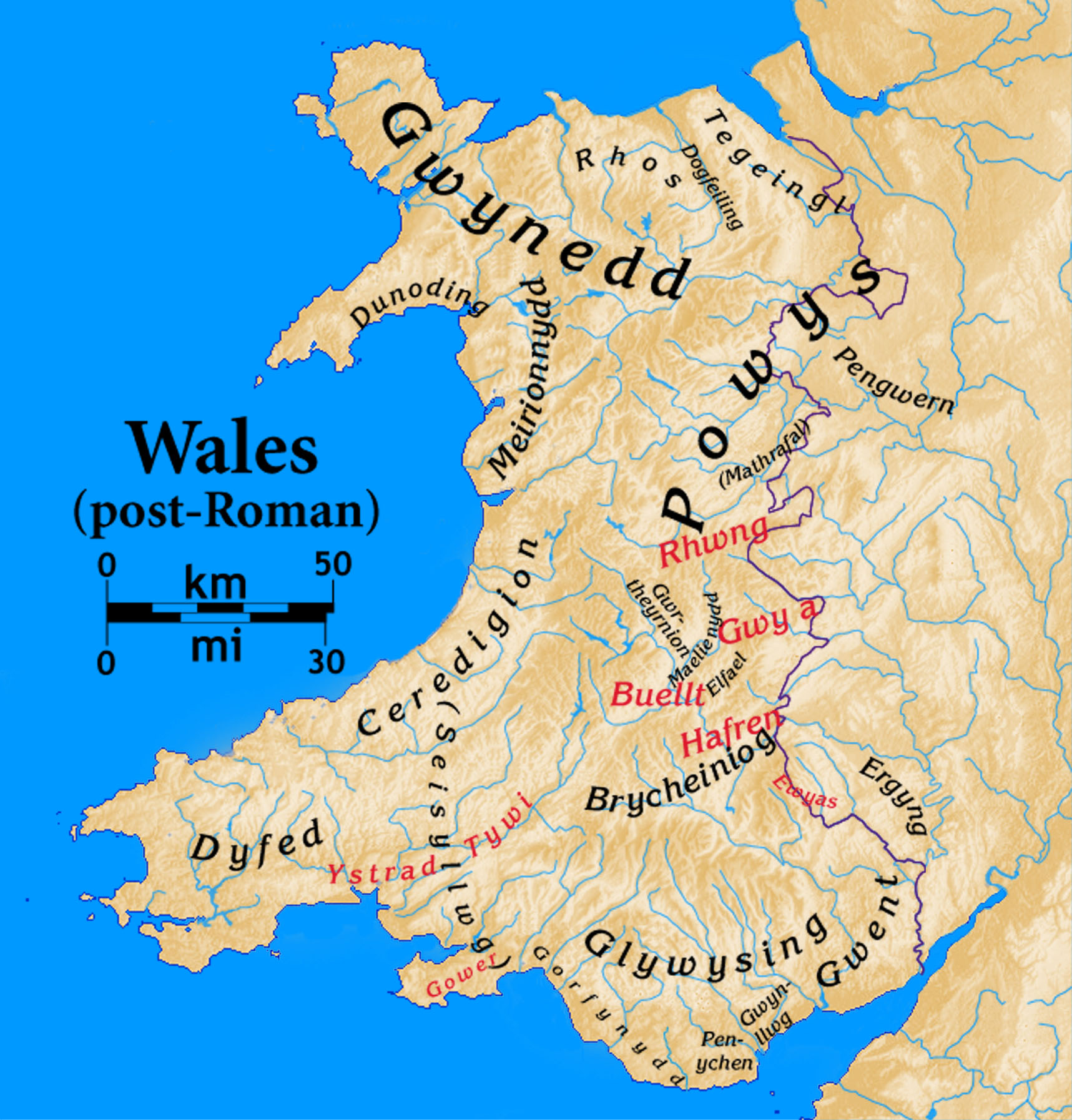

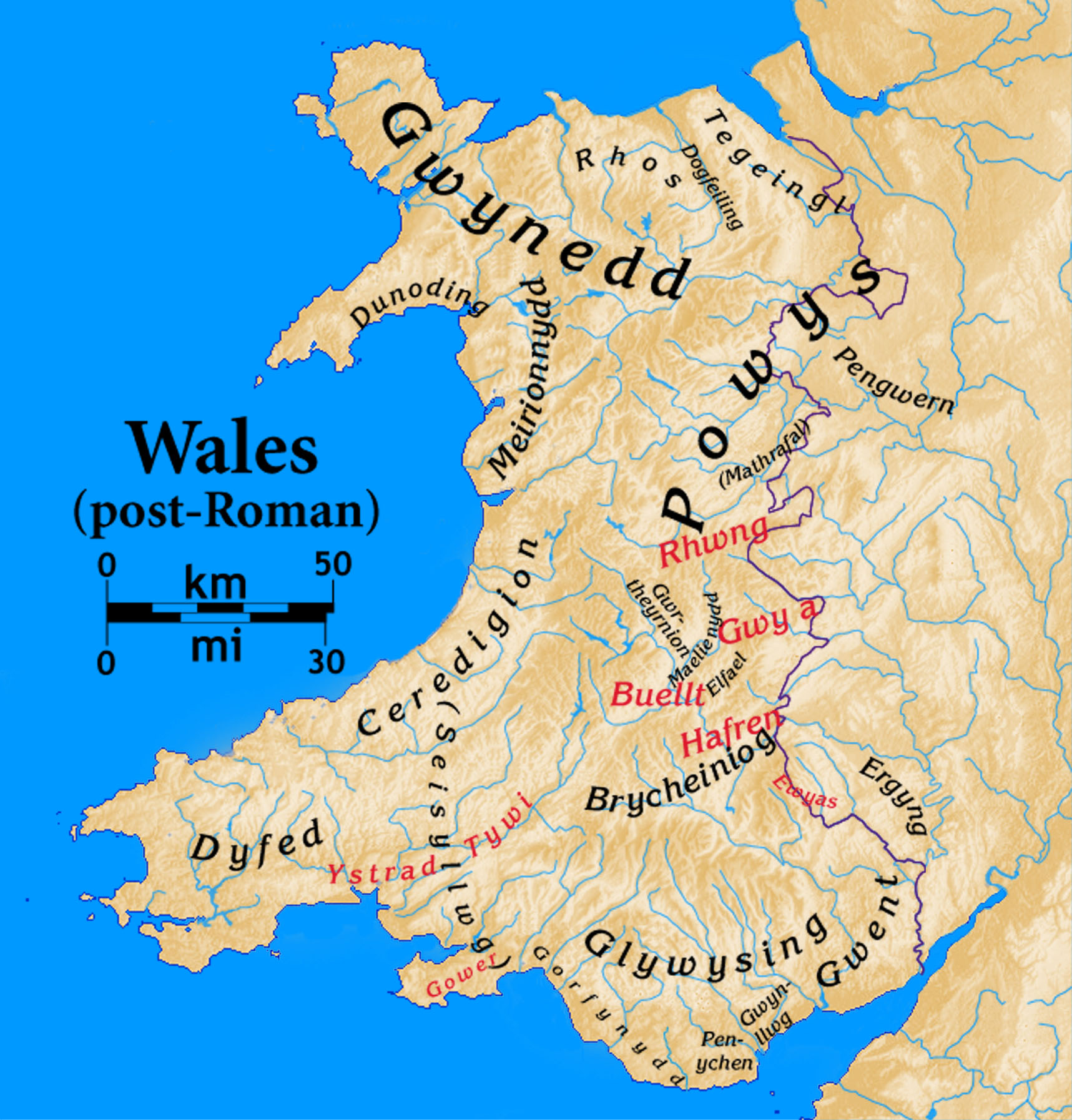

The exact origins and extent of the early kingdoms are speculative. The conjectured minor kings of the sixth century held small areas within a radius of perhaps , probably near the coast. Throughout the era there was dynastic strengthening in some areas while new kingdoms emerged and then disappeared in others. There is no reason to suppose that every part of Wales was part of kingdom even as late as 700.

Dyfed is the same land of the

The exact origins and extent of the early kingdoms are speculative. The conjectured minor kings of the sixth century held small areas within a radius of perhaps , probably near the coast. Throughout the era there was dynastic strengthening in some areas while new kingdoms emerged and then disappeared in others. There is no reason to suppose that every part of Wales was part of kingdom even as late as 700.

Dyfed is the same land of the

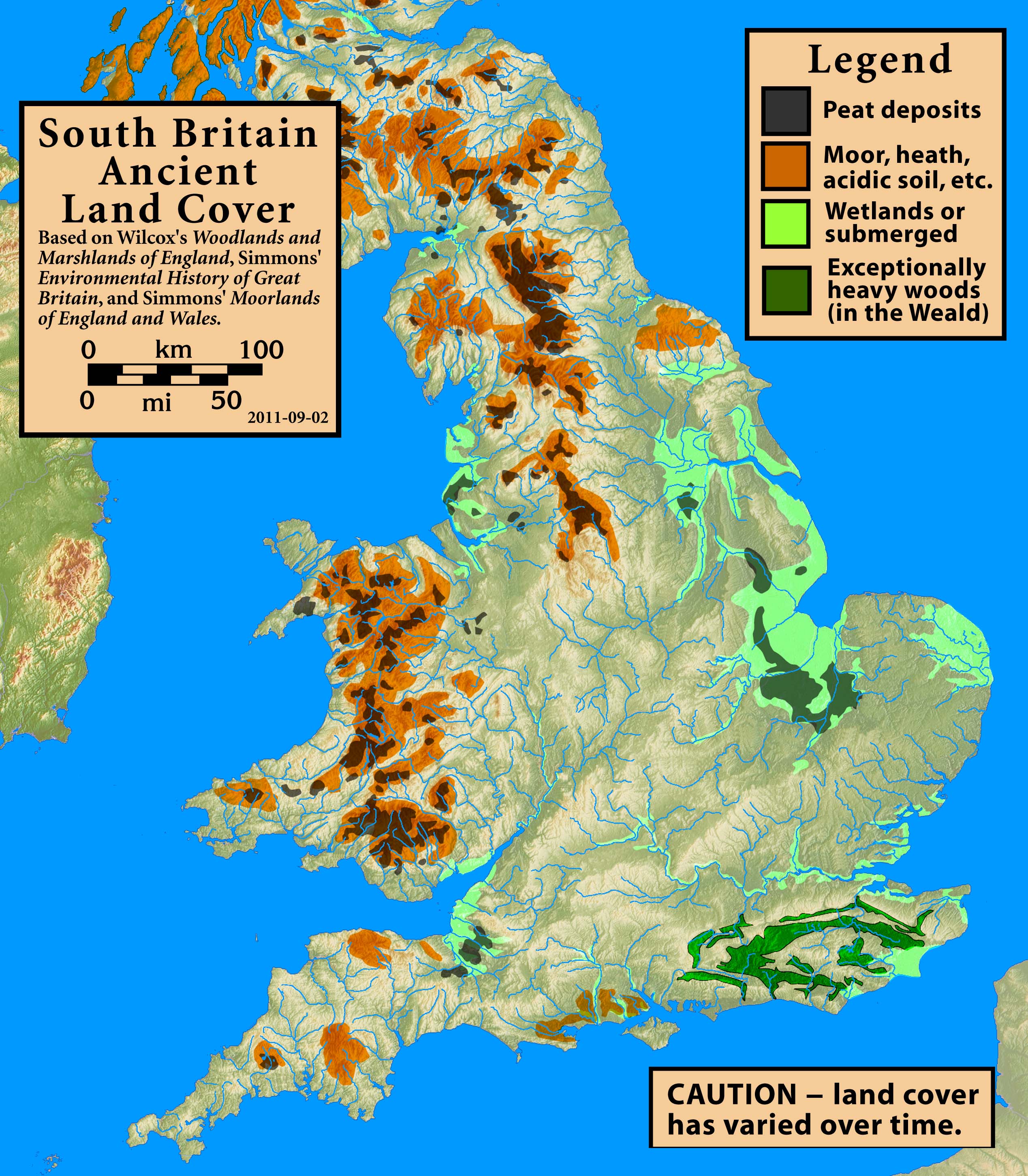

The total area of Wales is . Much of the landscape is mountainous with treeless moors and heath, and having large areas with

The total area of Wales is . Much of the landscape is mountainous with treeless moors and heath, and having large areas with

The early Middle Ages saw the creation and adoption of the modern Welsh name for themselves, ''Cymry'', a word descended from

The early Middle Ages saw the creation and adoption of the modern Welsh name for themselves, ''Cymry'', a word descended from

Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales pages on Early Middle Ages

{{DEFAULTSORT:Wales In The Early Middle Ages .01 Sub-Roman Britain

Wales in the early Middle Ages covers the time between the Roman departure from

Wales in the early Middle Ages covers the time between the Roman departure from Wales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the England–Wales border, east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic ...

c. 383 until the middle of the 11th century. In that time there was a gradual consolidation of power into increasingly hierarchical kingdoms. The end of the early Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

was the time that the Welsh language

Welsh ( or ) is a Celtic languages, Celtic language of the Brittonic languages, Brittonic subgroup that is native to the Welsh people. Welsh is spoken natively in Wales by about 18% of the population, by some in England, and in (the Welsh c ...

transitioned from the Primitive Welsh spoken throughout the era into Old Welsh

Old Welsh () is the stage of the Welsh language from about 800 AD until the early 12th century when it developed into Middle Welsh.Koch, p. 1757. The preceding period, from the time Welsh became distinct from Common Brittonic around 550, ha ...

, and the time when the modern England–Wales border would take its near-final form, a line broadly followed by Offa's Dyke, a late eighth-century earthwork. Successful unification into something recognisable as a Welsh state would come in the next era under the descendants of Merfyn Frych.

Wales was rural

In general, a rural area or a countryside is a geographic area that is located outside towns and cities. Typical rural areas have a low population density and small settlements. Agricultural areas and areas with forestry are typically desc ...

throughout the era, characterised by small settlements called ''trefi''. The local landscape was controlled by a local aristocracy and ruled by a warrior aristocrat. Control was exerted over a piece of land and, by extension, over the people who lived on that land. Many of the people were tenant peasants or slaves, answerable to the aristocrat who controlled the land on which they lived. There was no sense of a coherent tribe of people and everyone, from ruler down to slave, was defined in terms of his or her kindred family (the ''tud'') and individual status (''braint''). Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...

had been introduced in the Roman era, and the Celtic Britons living in and near Wales were Christian throughout the era.

The semi-legendary founding of Gwynedd in the fifth century was followed by internecine warfare in Wales and with the kindred Brittonic kingdoms of northern England

Northern England, or the North of England, refers to the northern part of England and mainly corresponds to the Historic counties of England, historic counties of Cheshire, Cumberland, County Durham, Durham, Lancashire, Northumberland, Westmo ...

and southern Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

(the Hen Ogledd

Hen Ogledd (), meaning the Old North, is the historical region that was inhabited by the Celtic Britons, Brittonic people of sub-Roman Britain in the Early Middle Ages, now Northern England and the southern Scottish Lowlands, alongside the fello ...

) and structural and linguistic divergence from the southwestern peninsula British kingdom of Dumnonia known to the Welsh as '' Cernyw'' prior to its eventual absorption into Wessex

The Kingdom of the West Saxons, also known as the Kingdom of Wessex, was an Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy, kingdom in the south of Great Britain, from around 519 until Alfred the Great declared himself as King of the Anglo-Saxons in 886.

The Anglo-Sa ...

. The seventh and eighth centuries were characterised by ongoing warfare by the northern and eastern Welsh kingdoms against the intruding Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the English, were a Cultural identity, cultural group who spoke Old English and inhabited much of what is now England and south-eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. They traced t ...

kingdoms of Northumbria

Northumbria () was an early medieval Heptarchy, kingdom in what is now Northern England and Scottish Lowlands, South Scotland.

The name derives from the Old English meaning "the people or province north of the Humber", as opposed to the Sout ...

and Mercia

Mercia (, was one of the principal kingdoms founded at the end of Sub-Roman Britain; the area was settled by Anglo-Saxons in an era called the Heptarchy. It was centred on the River Trent and its tributaries, in a region now known as the Midlan ...

. That era of struggle saw the Welsh adopt their modern name for themselves, ''Cymry'', meaning "fellow countrymen", and it also saw the demise of all but one of the kindred kingdoms of northern England and southern Scotland at the hands of then-ascendant Northumbria

Northumbria () was an early medieval Heptarchy, kingdom in what is now Northern England and Scottish Lowlands, South Scotland.

The name derives from the Old English meaning "the people or province north of the Humber", as opposed to the Sout ...

.

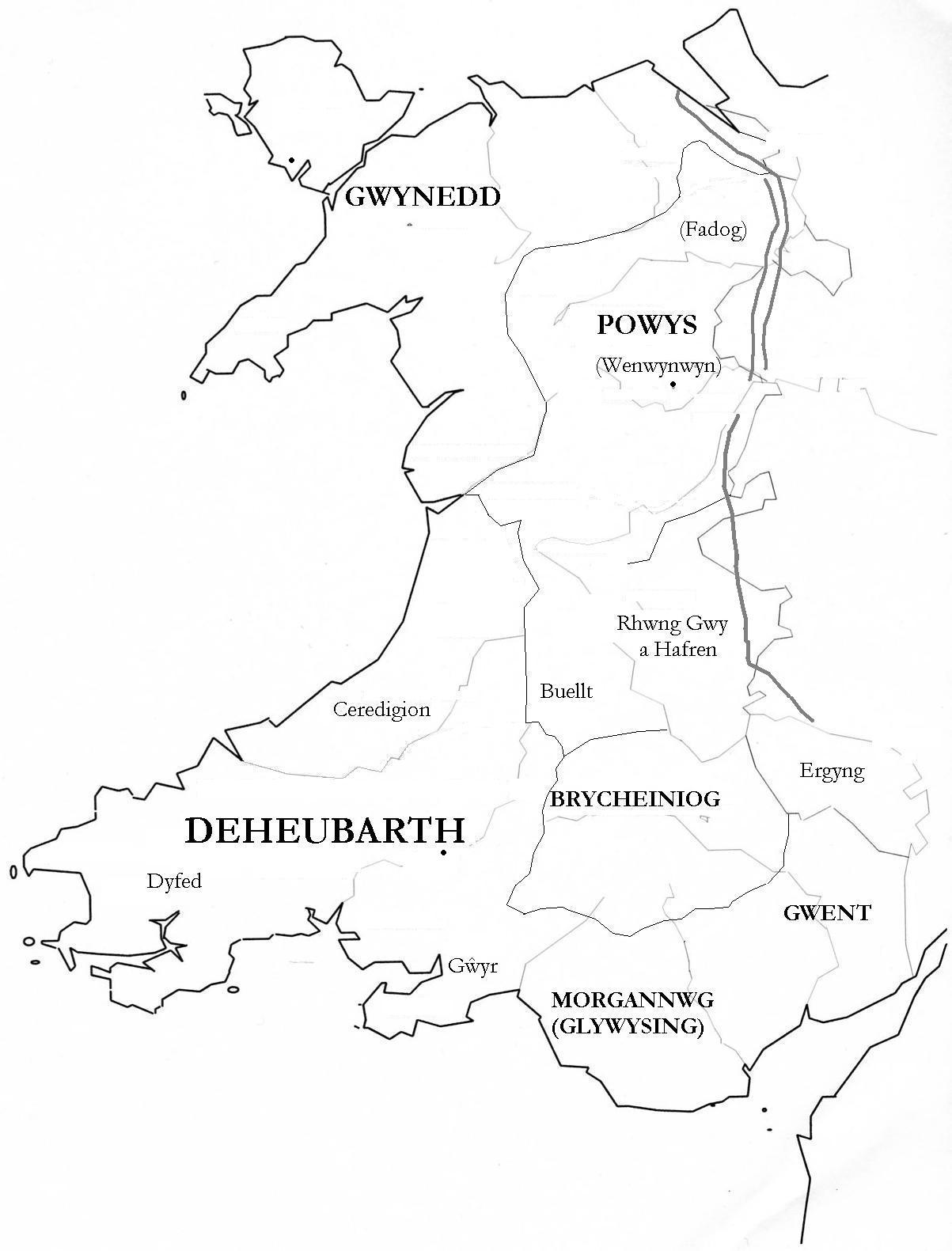

History

Wales as a nation was defined in opposition to later English settlement and incursions into the island of Great Britain. In the early middle ages, the people of Wales continued to think of themselves as Britons, the people of the whole island, but over the course of time one group of these Britons became isolated by the geography of the western peninsula, bounded by the sea and English neighbours. It was these English neighbours who named the land Wallia, and the people Welsh. The people of Wallia, medieval Wales, remained divided into separate kingdoms that fought with each other as much as they fought their English neighbours. Neither were the communities homogenously Welsh. Place name and archeological evidence point to Viking/Norse settlement in places such as Swansea, Fishguard and Anglesey, and Saxons settled amongst the Welsh in places such as Presteigne. It was the Norman invasion of England in 1066, which led soon after to incursions into Wales that overcame these rivalries, encouraging Welsh rulers to attempt to develop Wales into a unified state that could oppose this new threat. It was only in the final stages of conquest that Wales finally achieved this unity. It was the threat of invasion and conquest that created the nation of Wales. After the Roman withdrawal, Wales remained a rural landscape, controlled by warlords that formed a local aristocracy. Control was exerted over a piece of land and, by extension, over the people who lived on that land. Many of the people were tenant peasants or slaves, answerable to the aristocrat who controlled the land on which they lived. There was no sense of a coherent tribe of people and everyone, from ruler down to slave, was defined in terms of his or her kindred family (the tud) and individual status (braint). The Roman era had brought Christianity, and the Celtic Britons living in the land that would become Wales, and elsewhere in Britain, were Christian throughout the era, and their legacy is found in the many place names of Wales that are prefixed by , meaning a holy enclosure or church. The Welsh kingdoms arose in this period, in which the chieftains clashed with one another in internecine warfare, both in the territory that would become Wales (kingdoms such as Gwynedd) and across the Brittonic kingdoms of northern England and southern Scotland (the Hen Ogledd).This was also a time of structural and linguistic divergence from the southwestern peninsula British kingdom of Dumnonia known to the Welsh as Cernyw prior to its eventual absorption into Wessex. Cernyw would become Cornwall and their language would become Cornish. The seventh and eighth centuries were characterised by ongoing warfare by the northern and eastern Welsh kingdoms against the intruding Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of Northumbria and Mercia. That era of struggle saw the Welsh adopt their modern name for themselves, Cymry, meaning "fellow countrymen", and it also saw the demise of all but one of the kindred kingdoms of northern England and southern Scotland at the hands of then-ascendant Northumbria. One king, Hywel Dda,(translating to 'Howel The Good' in English) came close to uniting Wales as a single nation. He was king of Deheubarth but in 942 he intervened when Idwal Foel of Gwynedd was defeated in battle byEdmund

Edmund is a masculine given name in the English language. The name is derived from the Old English elements ''ēad'', meaning "prosperity" or "riches", and ''mund'', meaning "protector".

Persons named Edmund include:

People Kings and nobles

*Ed ...

, King of England. He thus took control of Gwynedd and Powys, making him ruler of all Wales except Morgannwg and Gwent. Hywel Dda instituted Welsh law, which was adopted across Wales, even after his kingdom was divided after his death.

Irish settlement

In the late fourth century there was an influx of settlers from southern

In the late fourth century there was an influx of settlers from southern Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

, the Uí Liatháin

The Uí Liatháin () were an early kingdom of Munster in southern Ireland. They belonged the same kindred as the Uí Fidgenti, and the two are considered together in the earliest sources, for example '' The Expulsion of the Déisi'' (incidental ...

and Laigin

The Laigin, modern spelling Laighin (), were a Gaelic population group of early Ireland. They gave their name to the Kingdom of Leinster, which in the medieval era was known in Irish as ''Cóiced Laigen'', meaning "Fifth/province of the Leinste ...

(with Déisi

The ''Déisi'' were a social class in Ireland between the ancient and early medieval period. The various peoples listed under the heading ''déis'' shared a similar status in Gaelic Ireland, and had little or no actual kinship, though they were ...

participation uncertain), arriving under unknown circumstances but leaving a lasting legacy especially in Dyfed. It is possible that they were invited to settle by the Welsh. There is no evidence of warfare, a bilingual regional heritage suggests peaceful coexistence and intermingling, and the ''Historia Brittonum

''The History of the Britons'' () is a purported history of early Britain written around 828 that survives in numerous recensions from after the 11th century. The ''Historia Brittonum'' is commonly attributed to Nennius, as some recensions ha ...

'' written c. 828 notes that a Welsh king had the power to settle foreigners and transfer tracts of land to them. That Roman-era regional rulers were able to exert such power is suggested by the Roman tolerance of native hill forts where there was local leadership under local law and custom. Whatever the circumstances, there is nothing known to connect these settlers either to Roman policy, or to the Irish raiders (the Scoti

''Scoti'' or ''Scotti'' is a Latin name for the Gaels,Duffy, Seán. ''Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia''. Routledge, 2005. p.698 first attested in the late 3rd century. It originally referred to all Gaels, first those in Ireland and then those ...

) of classical Roman accounts.

Roman-era legacy

Forts and roads are the most visible physical signs of a past Roman presence, along with the coins and Roman-era Latin inscriptions that are associated with Roman military sites. There is a legacy of Romanisation along the coast of southeastern Wales. In that region are found the remains of ''villa

A villa is a type of house that was originally an ancient Roman upper class country house that provided an escape from urban life. Since its origins in the Roman villa, the idea and function of a villa have evolved considerably. After the f ...

s'' in the countryside. Caerwent and three small urban sites, along with Carmarthen

Carmarthen (, ; , 'Merlin's fort' or possibly 'Sea-town fort') is the county town of Carmarthenshire and a community (Wales), community in Wales, lying on the River Towy north of its estuary in Carmarthen Bay. At the 2021 United Kingdom cen ...

and Roman Monmouth, are the only "urbanised" Roman sites in Wales. This region was placed under Roman civil administration ('' civitates'') in the mid-second century, with the rest of Wales being under military administration throughout the Roman era. There are a number of borrowings from the Latin lexicon

A lexicon (plural: lexicons, rarely lexica) is the vocabulary of a language or branch of knowledge (such as nautical or medical). In linguistics, a lexicon is a language's inventory of lexemes. The word ''lexicon'' derives from Greek word () ...

into Welsh, and while there are Latin-derived words with legal meaning in popular usage such as ''pobl'' ("people"), the technical words and concepts used in describing Welsh law in the Middle Ages are native Welsh, and not of Roman origin.

There is ongoing debate as to the extent of a lasting Roman influence being applicable to the early Middle Ages in Wales, and while the conclusions about Welsh history are important, Wendy Davies has questioned the relevance of the debates themselves by noting that whatever Roman provincial administration might have survived in places, it eventually became a new system appropriate to the time and place, and not a "hangover of archaic practices".

Earliest kingdoms

Demetae

The Demetae were a Celtic people of Iron Age and Roman period, who inhabited modern Pembrokeshire and Carmarthenshire in south-west Wales. The tribe also gave their name to the medieval Kingdom of Dyfed, the modern area and county of Dyfed and ...

shown on Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine science, Byzant ...

's map c. 150 during the Roman era. The fourth century arrival of Irish settlers intertwined the royal genealogies of Wales and Ireland, with Dyfed's rulers appearing in '' The Expulsion of the Déisi'', Harleian MS. 5389 and '' Jesus College MS. 20''. Its king Vortiporius was one of the kings condemned by Gildas

Gildas (English pronunciation: , Breton language, Breton: ''Gweltaz''; ) — also known as Gildas Badonicus, Gildas fab Caw (in Middle Welsh texts and antiquarian works) and ''Gildas Sapiens'' (Gildas the Wise) — was a 6th-century Britons (h ...

in his ''De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae

(English: ''On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain'') is a work written in Anglo-Latin literature, Latin in the late fifth or sixth century by the Britons (historical), British religious polemicist Gildas. It is a sermon in three parts condemnin ...

'', c. 540. — in Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

— English translation

While the better documented southeast shows a long and slow acquisition of property and power by the dynasty of Meurig ap Tewdrig in connection with the kingdoms of Glywysing

Glywysing was, from the sub-Roman period to the Early Middle Ages, a petty kingdom in south-east Wales. Its people were descended from the Iron Age tribe of the Silures, and frequently in union with Gwent, merging to form Morgannwg.

Name ...

, Gwent and Ergyng, there is a near-complete absence of information about many other areas. The earliest known name of a king of Ceredigion

Ceredigion (), historically Cardiganshire (, ), is a Principal areas of Wales, county in the West Wales, west of Wales. It borders Gwynedd across the River Dyfi, Dyfi estuary to the north, Powys to the east, Carmarthenshire and Pembrokeshire t ...

was Cereticiaun, who died in 807, and none of the mid-Welsh kingdoms can be evidenced before the eighth century. There are mentions of Brycheiniog

Brycheiniog was an independent kingdom in South Wales in the Early Middle Ages. It often acted as a buffer state between England to the east and the south Welsh kingdom of Deheubarth to the west. It was conquered and pacified by the Normans ...

and Gwrtheyrnion (near Buellt) in that era, but for the latter it is difficult to say whether it had either an earlier or a later existence., ''Wales in the Early Middle Ages''

The early history in the north and east are somewhat better known, with Gwynedd

Gwynedd () is a county in the north-west of Wales. It borders Anglesey across the Menai Strait to the north, Conwy, Denbighshire, and Powys to the east, Ceredigion over the Dyfi estuary to the south, and the Irish Sea to the west. The ci ...

having a semi-legendary origin in the arrival of Cunedda

Cunedda ap Edern, also called Cunedda ''Wledig'' (reigned – c. 460), was an important early Welsh people, Welsh leader, and the progenitor of the royal dynasty of Kingdom of Gwynedd, Gwynedd, one of the very oldest of Western Europe.

Nam ...

from Manau Gododdin in the fifth century (an inscribed sixth century gravestone records the earliest known mention of the kingdom). Its king Maelgwn Gwynedd was one of the kings condemned by Gildas

Gildas (English pronunciation: , Breton language, Breton: ''Gweltaz''; ) — also known as Gildas Badonicus, Gildas fab Caw (in Middle Welsh texts and antiquarian works) and ''Gildas Sapiens'' (Gildas the Wise) — was a 6th-century Britons (h ...

in his ''De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae

(English: ''On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain'') is a work written in Anglo-Latin literature, Latin in the late fifth or sixth century by the Britons (historical), British religious polemicist Gildas. It is a sermon in three parts condemnin ...

'', c. 540. There may also have been sixth-century kingdoms in Rhos, Meirionydd and Dunoding, all associated with Gwynedd.

The name of Powys

Powys ( , ) is a Principal areas of Wales, county and Preserved counties of Wales, preserved county in Wales. It borders Gwynedd, Denbighshire, and Wrexham County Borough, Wrexham to the north; the English Ceremonial counties of England, ceremo ...

is not certainly used before the ninth century, but its earlier existence (perhaps under a different name) is reasonably inferred by the fact that Selyf ap Cynan (d. 616) and his grandfather are in the Harleian genealogies

__NOTOC__

The Harleian genealogies are a collection of Old Welsh genealogies preserved in British Library, Harley MS 3859. Part of the Harleian Library, the manuscript, which also contains the '' Annales Cambriae'' (Recension A) and a version of ...

as the family of the known later kings of Powys, and Selyf's father Cynan ap Brochwel appears in poems attributed to Taliesen, where he is described as leading successful raids throughout Wales. Seventh-century Pengwern is associated with the later Powys through the poems of '' Canu Heledd'', which name sites from Shropshire

Shropshire (; abbreviated SalopAlso used officially as the name of the county from 1974–1980. The demonym for inhabitants of the county "Salopian" derives from this name.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West M ...

to Dogfeiling to Newtown in lamenting the demise of Pengwern's king Cynddylan; but the poem's geography probably reflects the time of its composition, around the ninth or tenth century rather that Cynddylan's own time.

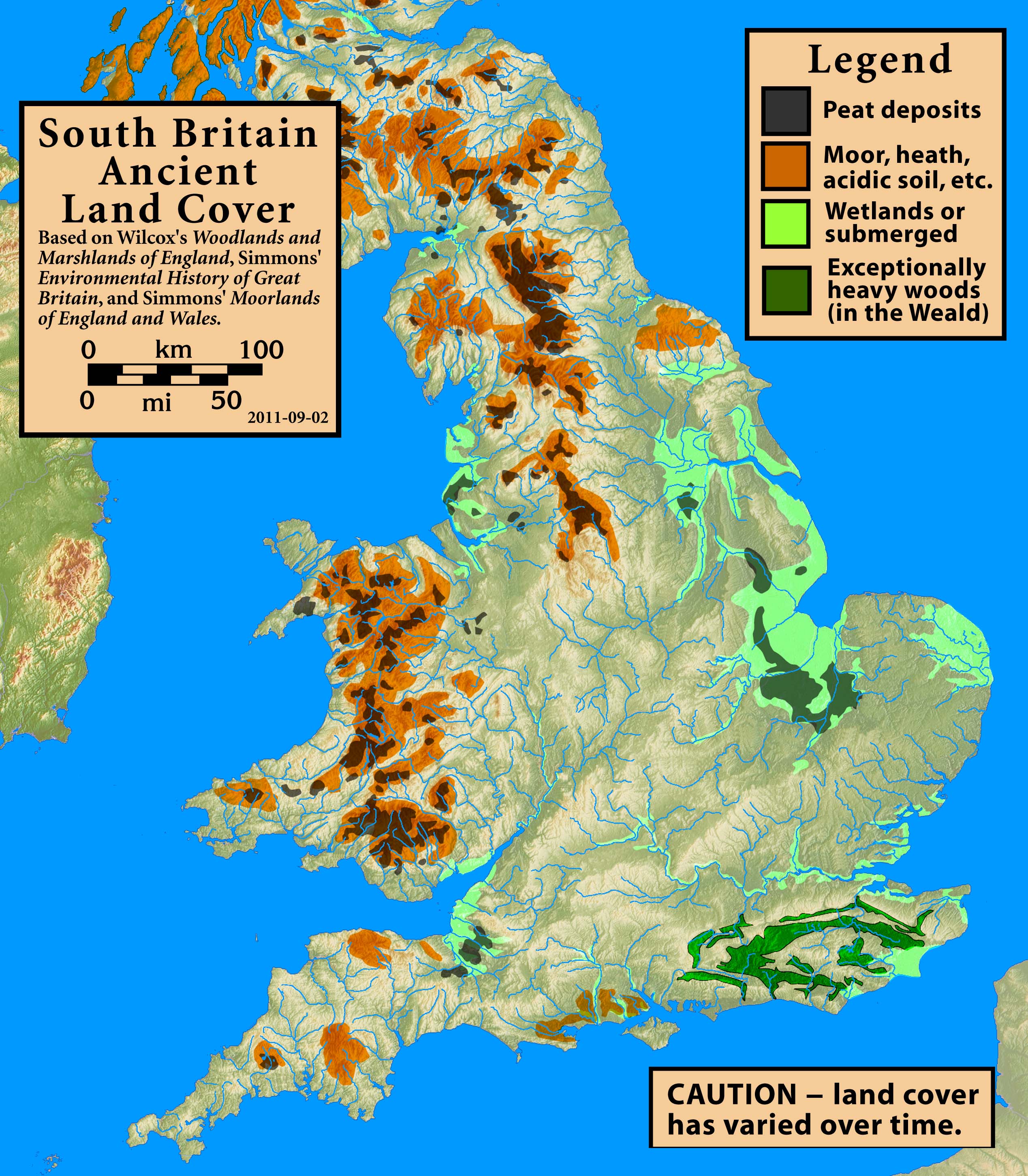

Geography

The total area of Wales is . Much of the landscape is mountainous with treeless moors and heath, and having large areas with

The total area of Wales is . Much of the landscape is mountainous with treeless moors and heath, and having large areas with peat

Peat is an accumulation of partially Decomposition, decayed vegetation or organic matter. It is unique to natural areas called peatlands, bogs, mires, Moorland, moors, or muskegs. ''Sphagnum'' moss, also called peat moss, is one of the most ...

deposits. There is approximately of coastline and some 50 offshore islands, the largest of which is Anglesey

Anglesey ( ; ) is an island off the north-west coast of Wales. It forms the bulk of the Principal areas of Wales, county known as the Isle of Anglesey, which also includes Holy Island, Anglesey, Holy Island () and some islets and Skerry, sker ...

. The present climate is wet and maritime, with warm summers and mild winters, much like the later medieval climate, though there was a significant change to cooler and much wetter conditions in the early part of the era.The same change in climate was occurring around the entire North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

perphery at this time. See Higham's ''Rome, Britain and the Anglo-Saxons'' (, 1992): cooler, wetter climate and abandonment of British uplands and marginal lands; Berglund's ''Human impact and climate changes—synchronous events and a causal link?'' in "Quaternary International", Vol. 105 (2003): Scandinavia, 500AD wetter and rapidly cooling climate and the retreat of agriculture; Ejstrud's ''The Migration Period, Southern Denmark and the North Sea'' (, 2008): p28, from the 6th century onwards farmlands in Denmark and Norway were abandoned; Issar's ''Climate changes during the holocene and their impact on Hydrological systems'' (, 2003): water level rise along NW coast of Europe, wetter conditions in Scandinavia and retreat of farming in Norway after 400, cooler climate in Scotland; Louwe Kooijmans' ''Archaeology and Coastal Change in the Netherlands'' (in Archaeology and Coastal Change, 1980): rising water levels along the NW coast of Europe; Louwe Kooijmans' ''The Rhine/Meuse Delta'' (PhD thesis, 1974): rising water levels along the NW coast of Europe, and in the Fens and Humber Estuary. Abundant material from other sources portrays the same information. The southeastern coast was originally a wetland, but reclamation has been ongoing since the Roman era.

There are deposits of gold, copper, lead, silver and zinc, and these have been exploited since the Iron Age

The Iron Age () is the final epoch of the three historical Metal Ages, after the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age. It has also been considered as the final age of the three-age division starting with prehistory (before recorded history) and progre ...

, especially so in the Roman era. In the Roman era some granite was quarried, as was slate in the north and sandstone in the east and south.

Native fauna included large and small mammals, such as the brown bear, wolf, wildcat, rodents, several species of weasel, and shrews, voles and many species of bat. There were many species of birds, fish and shellfish.

The early medieval human population has always been considered relatively low in comparison to England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

, but efforts to reliably quantify it have yet to provide widely acceptable results.

Subsistence

Much of the arable land is in the south, southeast, southwest, on Anglesey, and along the coast. However, specifying the ancient usage of land is problematic in that there is little surviving evidence on which to base the estimates. Forest clearance has taken place since the Iron Age, and it is not known how the ancient people of Wales determined the best use of the land for their particular circumstances, such as in their preference for wheat, oats, rye or barley depending on rainfall, growing season, temperature and the characteristics of the land on which they lived. Anglesey is the exception, historically producing more grain than any other part of Wales. Animal husbandry included the raising of cattle, pigs, sheep and a lesser number of goats. Oxen were kept for ploughing, asses for beasts of burden and horses for human transport. The importance of sheep was less than in later centuries, as their extensive grazing in the uplands did not begin until the thirteenth century. The animals were tended by swineherds and herdsmen, but they were not confined, even in the lowlands. Instead open land was used for feeding, and seasonaltranshumance

Transhumance is a type of pastoralism or Nomad, nomadism, a seasonal movement of livestock between fixed summer and winter pastures. In montane regions (''vertical transhumance''), it implies movement between higher pastures in summer and low ...

was practised. In addition, bees were kept for the production of honey.

Society

Kindred family

The importance of blood relationships, particularly in relation to birth and noble descent, was heavily stressed in medieval Wales. Claims of dynastic legitimacy rested on it, and an extensive patrilinear genealogy was used to assess fines and penalties under Welsh law. Different degrees of blood relationship were important for different circumstances, all based upon the ''cenedl'' (kindred). The nuclear family (parents and children) was especially important, while the ''pencenedl'' (head of the family within four patrilinear generations) held special status, representing the family in transactions and having certain unique privileges under the law. Under extraordinary circumstances the genealogical interest could be stretched quite far: for the serious matter of homicide, all of the fifth cousins of a kindred (the seventh generation: the patrilinear descendants of a common great-great-great-great-grandfather) were ultimately liable for satisfying any penalty.Land and political entities

The Welsh referred to themselves in terms of their territory and not in the sense of a tribe. Thus there was ''Gwenhwys'' (" Gwent" with a group-identifying suffix) and ''gwyr Guenti'' ("men of Gwent") and ''Broceniauc'' ("men ofBrycheiniog

Brycheiniog was an independent kingdom in South Wales in the Early Middle Ages. It often acted as a buffer state between England to the east and the south Welsh kingdom of Deheubarth to the west. It was conquered and pacified by the Normans ...

"). Welsh custom contrasted with many Irish and Anglo-Saxon contexts, where the territory was named for the people living there (Connaught for the Connachta, Essex for the East Saxons). This is aside from the origin of a territory's name, such as in the custom of attributing it to an eponymous founder (Glywysing

Glywysing was, from the sub-Roman period to the Early Middle Ages, a petty kingdom in south-east Wales. Its people were descended from the Iron Age tribe of the Silures, and frequently in union with Gwent, merging to form Morgannwg.

Name ...

for ''Glywys'', Ceredigion

Ceredigion (), historically Cardiganshire (, ), is a Principal areas of Wales, county in the West Wales, west of Wales. It borders Gwynedd across the River Dyfi, Dyfi estuary to the north, Powys to the east, Carmarthenshire and Pembrokeshire t ...

for ''Ceredig'').

The Welsh term for a political entity was ''gwlad'' ("country") and it expressed the notion of a "sphere of rule" with a territorial component. The Latin equivalent seems to be ''regnum'', which referred to the "changeable, expandable, contractable sphere of any ruler's power". Rule tended to be defined in relation to a territory that might be held and protected, or expanded or contracted, though the territories themselves were specific pieces of land and not synonyms for the ''gwlad''.

Throughout the Middle Ages the Welsh used a variety of words for rulers, with the specific words used varying over time, and with literary sources generally using different terms than annalistic ones. Latin language texts used Latin language terms while vernacular texts used Welsh terms. Not only did the specific terms vary, the meaning of those specific terms varied over time as well. For example, ''brenin'' was one of the terms used for a king in the twelfth century. The earlier, original meaning of ''brenin'' was simply a person of status.

Kings are sometimes described as overkings, but the definition of what that meant is unclear, whether referring to a king with definite powers, or to ideas of someone considered to have high status.

Kingship

Wales in the early Middle Ages was a society with a landed warrior aristocracy, and after c. 500 Welsh politics were dominated by kings with territorial kingdoms. The legitimacy of the kingship was of paramount importance, the legitimate attainment of power was by dynastic inheritance or military proficiency. A king had to be considered effective and be associated with wealth, either his own or by distributing it to others, and those considered to be at the top level were required to have wisdom, perfection, and a long reach. Literary sources stressed martial qualities such as military capability, bold horsemanship, leadership, the ability to extend boundaries and to make conquests, along with an association with wealth and generosity. Clerical sources stressed obligations such as respect for Christian principles, providing defence and protection, pursuing thieves and imprisoning offenders, persecuting evildoers, and making judgements. The relationship among people that is most appropriate to the warrior aristocracy is clientship and flexibility, and not one of sovereignty or absolute power, nor necessarily of long duration. Prior to the tenth century, power was held on a local level, and the limits of that power varied by region. There were at least two restraints on the limits of power: the combined will of the ruler's people (his "subjects"), and the authority of the Christian church., ''Wales in the Early Middle Ages''. There is little to explain the meaning of "subject" beyond noting that those under a ruler owed an assessment (effectively, taxes) and military service when demanded, while they were owed protection by the ruler.Kings

For much of the early medieval period kings had few functions except military ones. Kings made war and gave judgements (in consultation with local elders) but they did not govern in any sense of that word. From the sixth to the eleventh centuries the king moved about with an armed, mounted warband, a personal military retinue called a ''teulu'' that is described as a "small, swift-moving, and close-knit group". This military elite formed the core of any larger army that might be assembled. The relationships among the king and the members of his warband were personal, and the practice offosterage

Fosterage, the practice of a family bringing up a child not their own, differs from adoption in that the child's parents, not the foster-parents, remain the acknowledged parents. In many modern western societies foster care can be organised by ...

strengthened those personal bonds.

Aristocracy

Power was held at a local level by families who controlled the land and the people who lived on that land. They are differentiated legally by having a higher ''sarhaed'' (the penalty for insult) than the general populace, by the records of their transactions (such as land transfers) by their participation in local judgements and administration, and by their consultative role in judgements made by the king. References to the social stratification that defines an aristocracy are widely found in Welsh literature and law. A man's privilege was assessed in terms of his ''braint'' (status), of which there were two kinds (birth and office), and in terms of his superior's importance. Two men might each be an ''uchelwr'' (high man), but a king is higher than a ''breyr'' (a regional leader), so legal compensation for the loss to a king's bondsman (''aillt'') was higher than the equivalent loss to the bondsman of a ''breyr''. Early sources stressed birth and function as the determinators of nobility, and not by the factor of wealth that later became associated with an aristocracy.Populace

The populace included a hereditary tenant peasantry who were not slaves or serfs, but were less than free. ''Gwas'' ("servant", boy) referred to a dependent in perpetual servitude, but who was not bound to labour service (i.e., serfdom). Nor can the person be considered avassal

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerain ...

except perhaps as a clerical self-description, as in the 'vassal of a saint'. The early existence of the concept suggests a stratum of bound dependents in the post-Roman era. The proportion of the medieval population that consisted of freemen or free peasant proprietors is undetermined, even for the pre-Conquest period.

Slavery existed in Wales as it did elsewhere throughout the era. Slaves were in the bottom stratum of society, with hereditary slavery more common than penal slavery. Slaves might form part of the payment in a transaction made between those of higher rank. It was possible for them to buy their freedom, and an example of manumission at Llandeilo Fawr is given in a ninth-century ''marginalia'' note of the '' Lichfield Gospels''. Their relative numbers is a matter of guess and conjecture.

Christianity

The religious culture of Wales was overwhelmingly Christian in the early Middle Ages. Pastoral care of the laity was necessarily rural in Wales, as it was in other Celtic regions. In Wales the clergy consisted of monks, orders and non-monastic clergy, all appearing in different periods and in different contexts. There were three major orders consisting of bishops (''episcopi''), priests (''presbyteri'') and deacons, as well as several minor ones. Bishops had some temporal authority, but not necessarily in the sense of a full diocese.Communities

Monasticism is known in Britain in the fifth century though its origins are obscure. The Church seemed episcopally dominated and largely consisting of monasteries. The size of the religious communities is unknown (Bede

Bede (; ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, Bede of Jarrow, the Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable (), was an English monk, author and scholar. He was one of the most known writers during the Early Middle Ages, and his most f ...

and the Welsh Triads suggest they were large, the ''Lives of the Saints'' suggest they were small, but these are not considered credible sources on the matter). The different communities were pre-eminent within small spheres of influence (''ie'', within physical proximity of the communities). The known sites are mostly coastal, situated on good land. There are passing references to monks and monasteries in the sixth century (for example, Gildas

Gildas (English pronunciation: , Breton language, Breton: ''Gweltaz''; ) — also known as Gildas Badonicus, Gildas fab Caw (in Middle Welsh texts and antiquarian works) and ''Gildas Sapiens'' (Gildas the Wise) — was a 6th-century Britons (h ...

said that Maelgwn Gwynedd had originally intended to be a monk). From the seventh century onward there are few references to monks but more frequent references to 'disciples'.

Institutions

Archaeological evidence consists partly of the ruined remains of institutions, and in finds of inscriptions and the long cyst burials that are characteristic of post-Roman Christian Britons. The records of transactions and legal references provide information on the status of the clergy and its institutions. Landed proprietorship was the basis of support and income for all clerical communities, exploiting agriculture (crops), herding (sheep, pigs, goats), infrastructure (barns, threshing floors), and employing stewards to supervise the labour. Lands that were not adjacent to the communities provided income in the form of (in effect) a business of landlordship. Lands under clerical proprietorship were exempt from the fiscal demands of kings and secular lords. They had the power of ''nawdd'' (protection, as from legal process) and were ''noddfa'' (a "''nawdd'' place" or sanctuary). Clerical power was moral and spiritual, and this was sufficient to enforce recognition of their status and to demand compensation for any infringement on their rights and privileges.Bede's ''Ecclesiastical History''

The notion of a separate Anglo-Saxon and British approach to Christianity dates back at least toBede

Bede (; ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, Bede of Jarrow, the Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable (), was an English monk, author and scholar. He was one of the most known writers during the Early Middle Ages, and his most f ...

. He portrayed the Synod of Whitby

The Synod of Whitby was a Christianity, Christian administrative gathering held in Northumbria in 664, wherein King Oswiu ruled that his kingdom would calculate Easter and observe the monastic tonsure according to the customs of Roman Catholic, Ro ...

(in 664) as a set-piece battle between competing Celtic and Roman religious interests. While the synod was an important event in the history of England and brought finality to several issues in Anglo-Saxon Britain, Bede probably overemphasised its significance so as to stress the unity of the English Church.

Bede's characterisation of Saint Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; ; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430) was a theologian and philosopher of Berbers, Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia (Roman province), Numidia, Roman North Africa. His writings deeply influenced th ...

's meeting with seven British bishops and the monks of Bangor Is Coed (in 602–604) portrays the bishop of Canterbury as chosen by Rome to lead in Britain, while portraying the British clergy as being in opposition to Rome. He then adds a prophecy that the British church would be destroyed. His apocryphal prophecy of destruction is quickly fulfilled by the massacre of the Christian monks at Bangor Is Coed by the Northumbrians (c. 615), shortly after the meeting with Saint Augustine. Bede describes the massacre immediately following his delivery of the prophecy.

'Celtic' vs. 'Roman' myth

One consequence of theProtestant Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the papacy and ...

and subsequent ethnic and religious discord in Britain and Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

was the promotion of the idea of a 'Celtic' church that was different from and at odds with the 'Roman' church, and that held to certain offensive customs, especially in the dating of Easter, the tonsure

Tonsure () is the practice of cutting or shaving some or all of the hair on the scalp as a sign of religious devotion or humility. The term originates from the Latin word ' (meaning "clipping" or "shearing") and referred to a specific practice in ...

, and the liturgy

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and participation in the sacred through activities reflecting praise, thanksgiving, remembra ...

. Scholars have noted the partisan motives and inaccuracy of the characterisation, as has ''The Catholic Encyclopedia

''The'' ''Catholic Encyclopedia: An International Work of Reference on the Constitution, Doctrine, Discipline, and History of the Catholic Church'', also referred to as the ''Old Catholic Encyclopedia'' and the ''Original Catholic Encyclopedi ...

'', which also explains that the Britons using the 'Celtic Rite' in the early Middle Ages were in communion with Rome.

Cymry: Welsh identity forms

The early Middle Ages saw the creation and adoption of the modern Welsh name for themselves, ''Cymry'', a word descended from

The early Middle Ages saw the creation and adoption of the modern Welsh name for themselves, ''Cymry'', a word descended from Common Brittonic

Common Brittonic (; ; ), also known as British, Common Brythonic, or Proto-Brittonic, is a Celtic language historically spoken in Britain and Brittany from which evolved the later and modern Brittonic languages.

It is a form of Insular Cel ...

''combrogi'', meaning "fellow-countrymen". It appears in '' Moliant Cadwallon'' (''In Praise of Cadwallon''), a poem written by Cadwallon ap Cadfan's bard Afan Ferddig c. 633, and probably came into use a self-description before the seventh century. Historically the word applies to both the Welsh and the Brythonic-speaking peoples of northern England and southern Scotland, the peoples of the Hen Ogledd

Hen Ogledd (), meaning the Old North, is the historical region that was inhabited by the Celtic Britons, Brittonic people of sub-Roman Britain in the Early Middle Ages, now Northern England and the southern Scottish Lowlands, alongside the fello ...

, and emphasises a perception that the Welsh and the "Men of the North" were one people, exclusive of all others. Universal acceptance of the term as the preferred written one came slowly in Wales, eventually supplanting the earlier ''Brython'' or ''Brittones''. The term was not applied to the Cornish people or the Bretons

The Bretons (; or , ) are an ethnic group native to Brittany, north-western France. Originally, the demonym designated groups of Common Brittonic, Brittonic speakers who emigrated from Dumnonia, southwestern Great Britain, particularly Cornwal ...

, who share a similar heritage, culture and language with the Welsh and the Men of the North. Rhys adds that the Bretons sometimes give the simple ''brô'' the sense of compatriot.

All of the ''Cymry'' shared a similar language, culture and heritage. Their histories are stories of warrior kings waging war, and they are intertwined in a way that is independent of physical location, in no way dissimilar to the way that the histories of neighboring Gwynedd and Powys are intertwined. Kings of Gwynedd campaigned against Brythonic opponents in the north.

Sometimes the kings of different kingdoms acted in concert, as is told in the literary '' Y Gododdin''. Much of the early Welsh poetry and literature was written in the Old North by northern ''Cymry''.

All of the northern kingdoms and people were eventually absorbed into the kingdoms of England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

and Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

, and their histories are now mostly a footnote in the histories of those later kingdoms, though vestiges of the ''Cymry'' past are occasionally visible. In Scotland the fragmentary remains of the '' Laws of the Bretts and Scotts'' show Brythonic influence, and some of these were copied into the '' Regiam Majestatem'', the oldest surviving written digest of Scots law

Scots law () is the List of country legal systems, legal system of Scotland. It is a hybrid or mixed legal system containing Civil law (legal system), civil law and common law elements, that traces its roots to a number of different histori ...

, where can be found the 'galnes' (''galanas

''Galanas'' in Welsh law was a payment made by a Kin punishment, killer and his family to the family of his or her victim. It is similar to éraic in Ireland and the Anglo-Saxons, Anglo-Saxon weregild.

Definition

The details of galanas were lai ...

'') that is familiar to Welsh law.. See, for example ''CAPUT XXXVI'', and elsewhere. Page 164 shows Item 7 of Chapter 36, "7 Item, LE CRO, & Galnes & Enach ...".

See also

*Matter of Britain

The Matter of Britain (; ; ; ) is the body of medieval literature and legendary material associated with Great Britain and Brittany and the list of legendary kings of Britain, legendary kings and heroes associated with it, particularly King Art ...

* Medieval Welsh literature

Notes

Citations

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales pages on Early Middle Ages

{{DEFAULTSORT:Wales In The Early Middle Ages .01 Sub-Roman Britain

Wales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the England–Wales border, east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic ...

Christianization of Europe