Walter Gilbert on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

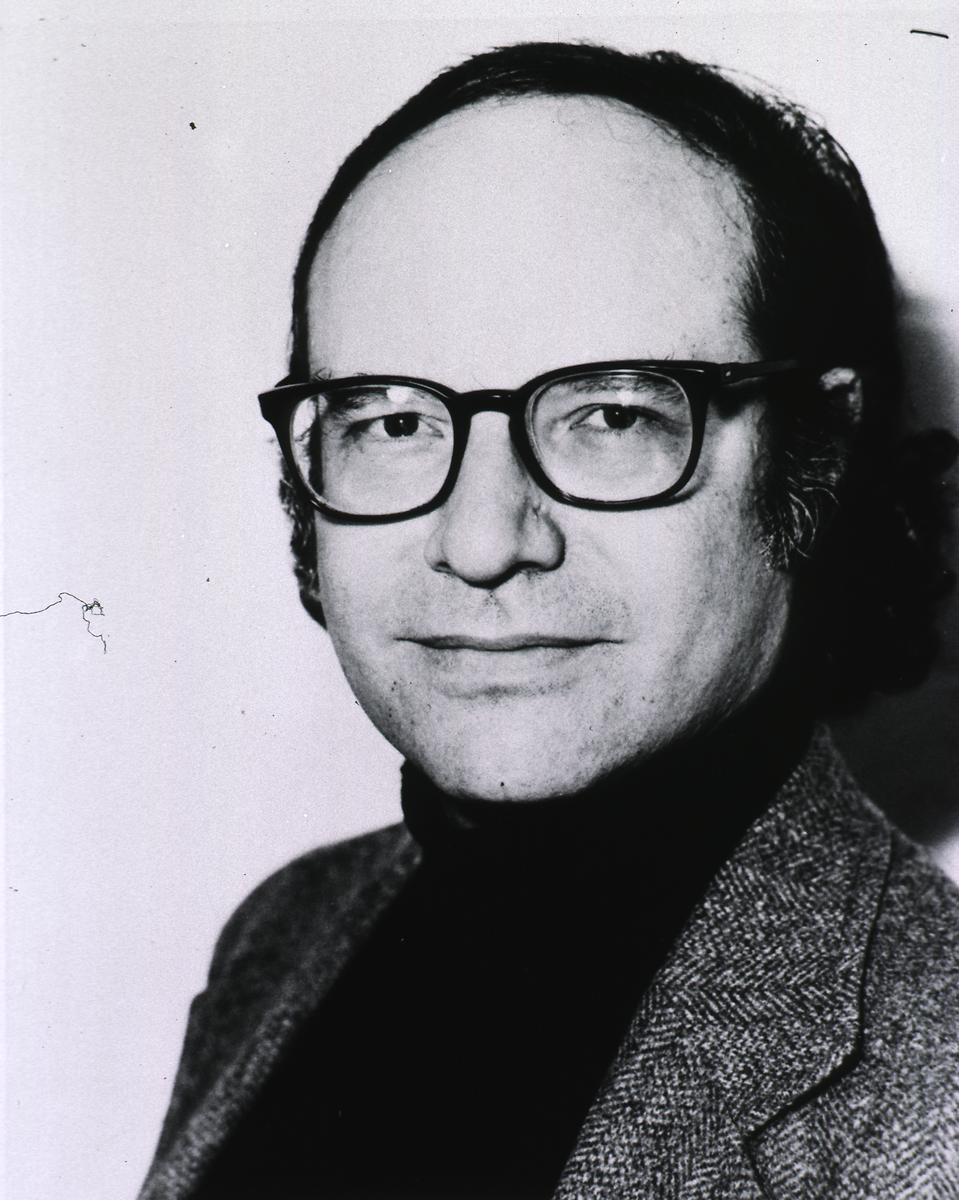

Walter Gilbert (born March 21, 1932) is an American

In 1969, Gilbert was awarded Harvard's Ledlie Prize. In 1972 he was named

In 1969, Gilbert was awarded Harvard's Ledlie Prize. In 1972 he was named

biochemist

Biochemists are scientists who are trained in biochemistry. They study chemical processes and chemical transformations in living organisms. Biochemists study DNA, proteins and Cell (biology), cell parts. The word "biochemist" is a portmanteau of ...

, physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe. Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

, molecular biology

Molecular biology is a branch of biology that seeks to understand the molecule, molecular basis of biological activity in and between Cell (biology), cells, including biomolecule, biomolecular synthesis, modification, mechanisms, and interactio ...

pioneer, and Nobel laureate

The Nobel Prizes (, ) are awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Swedish Academy, the Karolinska Institutet, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee to individuals and organizations who make outstanding contributions in th ...

.

Education and early life

Walter Gilbert was born inBoston, Massachusetts

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

, on March 21, 1932, into a Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

family, the son of Emma (Cohen), a child psychologist, and Richard V. Gilbert, an economist.

When Gilbert was seven years old, the family moved to the Washington D.C. area so his father could work under Harry Hopkins

Harold Lloyd Hopkins (August 17, 1890 – January 29, 1946) was an American statesman, public administrator, and presidential advisor. A trusted deputy to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Hopkins directed New Deal relief programs before ser ...

on the New Deal brain trust. While living in Washington the family became friends with the family of I.F. Stone and Wally met Stone's oldest daughter, Celia, when they were both 8. They later married at age 21.

He was educated at the Sidwell Friends School, and attended Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

for undergraduate and graduate studies, earning a baccalaureate in chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a physical science within the natural sciences that studies the chemical elements that make up matter and chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules a ...

and physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

in 1953 and a master's degree

A master's degree (from Latin ) is a postgraduate academic degree awarded by universities or colleges upon completion of a course of study demonstrating mastery or a high-order overview of a specific field of study or area of professional prac ...

in physics in 1954. He studied for his doctorate at the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

, where he earned a PhD

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD, DPhil; or ) is a terminal degree that usually denotes the highest level of academic achievement in a given discipline and is awarded following a course of graduate study and original research. The name of the deg ...

in physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

supervised by the Nobel laureate Abdus Salam in 1957.

Career and research

Gilbert returned to Harvard in 1956 and was appointed assistant professor of physics in 1959. Gilbert's wife Celia worked forJames Watson

James Dewey Watson (born April 6, 1928) is an American molecular biology, molecular biologist, geneticist, and zoologist. In 1953, he co-authored with Francis Crick the academic paper in ''Nature (journal), Nature'' proposing the Nucleic acid ...

, leading Gilbert to become interested in molecular biology. Watson and Gilbert ran their laboratory jointly through most of the 1960s, until Watson left for Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) is a private, non-profit institution with research programs focusing on cancer, neuroscience, botany, genomics, and quantitative biology. It is located in Laurel Hollow, New York, in Nassau County, on ...

. In 1964 he was promoted to associate professor of biophysics and promoted again in 1968 to professor of biochemistry.

Gilbert is a co-founder of the biotech start-up companies Biogen

Biogen Inc. is an American multinational biotechnology company based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States specializing in the discovery, development, and delivery of the treatment of neurological diseases to patients worldwide. Biogen ope ...

, with Kenneth Murray, Phillip Sharp and Charles Weissman and Myriad Genetics with Dr. Mark Skolnick and Kevin Kimberlin where he was the first chairman on their respective boards of directors. Gilbert left his position at Harvard to run Biogen as CEO, but was later asked to resign by the company's board of directors. He is a member of the Board of Scientific Governors at The Scripps Research Institute

Scripps Research is a nonprofit American medical research facility that focuses on research and education in the biomedical sciences. Headquartered in San Diego, California, the institute has over 170 laboratories employing 2,100 scientists, tec ...

. Gilbert has served as the chairman of the Harvard Society of Fellows The Society of Fellows is a group of scholars selected at the beginnings of their careers by Harvard University for their potential to advance academic wisdom, upon whom are bestowed distinctive opportunities to foster their individual and intellect ...

.

In 1996, Gilbert and Stuart B. Levy founded Paratek Pharmaceuticals. Gilbert served as chairman until 2014.

Gilbert was an early proponent of sequencing the human genome

The human genome is a complete set of nucleic acid sequences for humans, encoded as the DNA within each of the 23 distinct chromosomes in the cell nucleus. A small DNA molecule is found within individual Mitochondrial DNA, mitochondria. These ar ...

. At a March 1986 meeting in Santa Fe New Mexico he proclaimed "The total human sequence is the grail of human genetics". In 1987, he proposed starting a company called Genome Corporation to sequence the genome and sell access to the information. In an opinion piece in ''Nature'' in 1991, he envisioned completion of the human genome sequence transforming biology into a field in which computer databases would be as essential as laboratory reagents

Gilbert returned to Harvard in 1985. Gilbert was an outspoken critic of David Baltimore

David Baltimore (born March 7, 1938) is an American biologist, university administrator, and 1975 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, Nobel laureate in Physiology or Medicine. He is a professor of biology at the California Institute of Tech ...

in the handling of the scientific fraud accusations against Thereza Imanishi-Kari. Gilbert also joined the early controversy over the cause of AIDS.

In 1962, Gilbert's physics PhD student Gerald Guralnik extended Gilbert's work on massless particles; Guralnik's work is widely recognized as an important thread in the discovery of the Higgs Boson

The Higgs boson, sometimes called the Higgs particle, is an elementary particle in the Standard Model of particle physics produced by the excited state, quantum excitation of the Higgs field,

one of the field (physics), fields in particl ...

.

With his PhD student Benno Müller-Hill, Gilbert was the first to purify the lac repressor, just beating out Mark Ptashne for purifying the first gene regulatory protein.

Together with Allan Maxam, Gilbert developed a new DNA sequencing

DNA sequencing is the process of determining the nucleic acid sequence – the order of nucleotides in DNA. It includes any method or technology that is used to determine the order of the four bases: adenine, thymine, cytosine, and guanine. The ...

method, Maxam–Gilbert sequencing

Maxam–Gilbert sequencing is a method of DNA sequencing developed by Allan Maxam and Walter Gilbert in 1976–1977. This method is based on nucleobase-specific partial chemical modification of DNA and subsequent cleavage of the DNA backbone at ...

, using chemical methods developed by Andrei Mirzabekov. His approach to the first synthesis of insulin

Insulin (, from Latin ''insula'', 'island') is a peptide hormone produced by beta cells of the pancreatic islets encoded in humans by the insulin (''INS)'' gene. It is the main Anabolism, anabolic hormone of the body. It regulates the metabol ...

via recombinant DNA

Recombinant DNA (rDNA) molecules are DNA molecules formed by laboratory methods of genetic recombination (such as molecular cloning) that bring together genetic material from multiple sources, creating sequences that would not otherwise be fo ...

lost out to Genentech

Genentech, Inc. is an American biotechnology corporation headquartered in South San Francisco, California. It operates as an independent subsidiary of holding company Roche. Genentech Research and Early Development operates as an independent cent ...

's approach which used genes built up from the nucleotides rather than from natural sources. Gilbert's effort was hampered by a temporary moratorium on recombinant DNA work in Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge ( ) is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. It is a suburb in the Greater Boston metropolitan area, located directly across the Charles River from Boston. The city's population as of the 2020 United States census, ...

, forcing his group to move their work to an English biological weapons site.

Gilbert first proposed the terms introns

An intron is any Nucleic acid sequence, nucleotide sequence within a gene that is not expressed or operative in the final RNA product. The word ''intron'' is derived from the term ''intragenic region'', i.e., a region inside a gene."The notion of ...

(intragenic regions) and exons

An exon is any part of a gene that will form a part of the final mature RNA produced by that gene after introns have been removed by RNA splicing. The term ''exon'' refers to both the DNA sequence within a gene and to the corresponding sequence i ...

(expressed regions) in reference to recently discovered phenomenon of splicing and suggested explanation for the evolution of introns in a seminal 1978 "News and Views" correspondence to ''Nature

Nature is an inherent character or constitution, particularly of the Ecosphere (planetary), ecosphere or the universe as a whole. In this general sense nature refers to the Scientific law, laws, elements and phenomenon, phenomena of the physic ...

'' titled "why genes in pieces?". In 1986, Gilbert proposed the RNA world hypothesis for the origin of life

Abiogenesis is the natural process by which life arises from abiotic component, non-living matter, such as simple organic compounds. The prevailing scientific hypothesis is that the transition from non-living to organism, living entities on ...

, based on a concept first proposed by Carl Woese

Carl Richard Woese ( ; July 15, 1928 – December 30, 2012) was an American microbiologist and biophysicist. Woese is famous for defining the Archaea (a new domain of life) in 1977 through a pioneering phylogenetic taxonomy of 16S ribosomal ...

in 1967.

Awards and honors

In 1969, Gilbert was awarded Harvard's Ledlie Prize. In 1972 he was named

In 1969, Gilbert was awarded Harvard's Ledlie Prize. In 1972 he was named American Cancer Society

The American Cancer Society (ACS) is a nationwide non-profit organization dedicated to eliminating cancer. The ACS publishes the journals ''Cancer'', '' CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians'' and '' Cancer Cytopathology''.

History

The society w ...

Professor of Molecular Biology. In 1979, Gilbert was awarded the Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize

The Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize for Biology or Biochemistry is an annual prize awarded by Columbia University to a researcher or group of researchers who have made an outstanding contribution in basic research in the fields of biology or biochemist ...

from Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

together with Frederick Sanger

Frederick Sanger (; 13 August 1918 – 19 November 2013) was a British biochemist who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry twice.

He won the 1958 Chemistry Prize for determining the amino acid sequence of insulin and numerous other prote ...

. That year he was also awarded the Gairdner Prize and the Albert Lasker Award for Basic Medical Research

The Albert Lasker Award for Basic Medical Research is one of the Lasker Award, prizes awarded by the Lasker Foundation for a fundamental discovery that opens up a new area of biomedical science. The award frequently precedes a Nobel Prize in Phys ...

.

Gilbert was awarded the 1980 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry () is awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to scientists in the various fields of chemistry. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Alfred Nobel in 1895, awarded for outst ...

, shared with Frederick Sanger

Frederick Sanger (; 13 August 1918 – 19 November 2013) was a British biochemist who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry twice.

He won the 1958 Chemistry Prize for determining the amino acid sequence of insulin and numerous other prote ...

and Paul Berg. Gilbert and Sanger were recognized for their pioneering work in devising methods for determining the sequence of nucleotide

Nucleotides are Organic compound, organic molecules composed of a nitrogenous base, a pentose sugar and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both o ...

s in a nucleic acid

Nucleic acids are large biomolecules that are crucial in all cells and viruses. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomer components: a pentose, 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main classes of nuclei ...

.

Gilbert has also been honored by the National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, NGO, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the ...

(US Steel Foundation Award, 1968); Massachusetts General Hospital

Massachusetts General Hospital (Mass General or MGH) is a teaching hospital located in the West End neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts. It is the original and largest clinical education and research facility of Harvard Medical School/Harvar ...

(Warren Triennial Prize, 1977); the New York Academy of Sciences

The New York Academy of Sciences (NYAS), originally founded as the Lyceum of Natural History in January 1817, is a nonprofit professional society based in New York City, with more than 20,000 members from 100 countries. It is the fourth-oldes ...

; (Louis and Bert Freedman Foundation Award, 1977), the Académie des Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (, ) is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French Scientific method, scientific research. It was at the forefron ...

of France (Prix Charles-Leopold Mayer Award, 1977). Gilbert was elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society (ForMemRS) in 1987.

In 2002, he received the Biotechnology Heritage Award, from the Biotechnology Industry Organization

The Biotechnology Innovation Organization (BIO) is the largest advocacy association in the world representing the biotechnology industry.

It was founded in 1993 as the Biotechnology Industry Organization from a merger of the Industrial Biotechno ...

(BIO) and the Chemical Heritage Foundation

The Science History Institute is an institution that preserves and promotes understanding of the history of science. Located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, it includes a library, museum, archive, research center and conference center.

It was ...

.

Allan Maxam and Walter Gilbert's 1977 paper "A new method for sequencing DNA" was honored by a Citation for Chemical Breakthrough Award from the Division of History of Chemistry of the American Chemical Society for 2017. It was presented to the Department of Molecular & Cellular Biology, Harvard University.

Personal life

Gilbert married Celia Stone, the daughter of I. F. Stone, in 1953 and has two children. After retiring from Harvard in 2001, Gilbert has launched an artistic career to combine art and science. His art format is centered on digital photography.

See also

* List of Jewish Nobel laureatesReferences

External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Gilbert, Walter 1932 births Nobel laureates in Chemistry American Nobel laureates Jewish Nobel laureates Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge American biochemists 21st-century American physicists Foreign members of the Royal Society Harvard College alumni Living people Scientists from Boston Harvard Fellows Scripps Research American biotechnologists Recipients of the Albert Lasker Award for Basic Medical Research Sidwell Friends School alumni Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences alumni Fellows of the American Physical Society