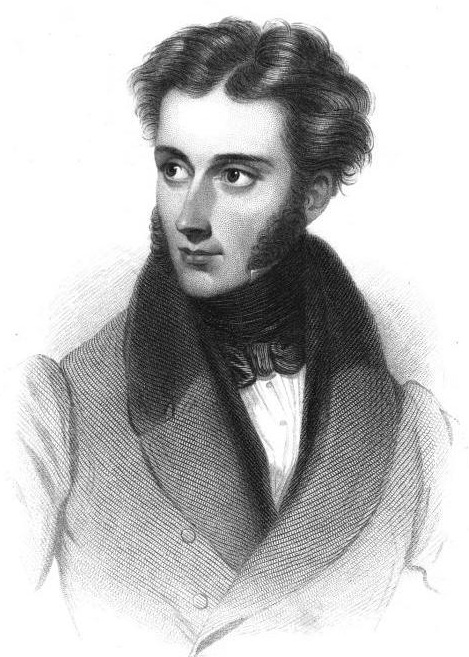

W. M. Praed on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Winthrop Mackworth Praed (28 July 180215 July 1839)—typically written as W. Mackworth Praed—was an

Winthrop Mackworth Praed (28 July 180215 July 1839)—typically written as W. Mackworth Praed—was an

Winthrop Mackworth Praed (28 July 180215 July 1839)—typically written as W. Mackworth Praed—was an

Winthrop Mackworth Praed (28 July 180215 July 1839)—typically written as W. Mackworth Praed—was an English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Culture, language and peoples

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

* ''English'', an Amish ter ...

politician and poet.

Life

Early life

Praed was born inLondon

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

. The family name of Praed was derived from the marriage of the poet's great-grandfather to a Cornish heiress. Winthrop's father, William Mackworth Praed, was a serjeant-at-law (1756–1835) and a revising barrister

Electors must be on the electoral register in order to vote in elections and referendums in the UK. Electoral registration officers within local authorities have a duty to compile and maintain accurate electoral registers.

Registration was introd ...

for Bath. His mother belonged to the English branch of the New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

family of Winthrop.

In 1814 Praed was sent to Eton College

Eton College ( ) is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school providing boarding school, boarding education for boys aged 13–18, in the small town of Eton, Berkshire, Eton, in Berkshire, in the United Kingdom. It has educated Prime Mini ...

, where he founded a manuscript periodical called ''Apis matina''. This was succeeded in October 1820 by the ''Etonian'', a paper projected and edited by Praed and Walter Blount, which appeared every month until July 1821, when the chief editor, who signed his contributions "Peregrine Courtenay," left Eton, and the paper died. Henry Nelson Coleridge

Henry Nelson Coleridge (25 October 1798 – 26 January 1843) was an editor of the works of his uncle Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

Life

His father was Colonel James Coleridge, of Ottery St. Mary.

He was born on 25 October 1798.

He was educated at ...

, William Sidney Walker

William Sidney Walker (1795–1846) was an English Shakespearean critic.

Life

Born at Pembroke in Wales, on 4 December 1795, he was the eldest child of John Walker, a naval officer, who died at Twickenham in 1811 from the effects of wounds recei ...

, and John Moultrie were the three best known of his collaborators on this periodical, which was published by Charles Knight, and of which details are given in Knight's ''Autobiography'' and in Henry Maxwell Lyte

Sir Henry Churchill Maxwell Lyte (or Maxwell-Lyte) (29 May 1848 – 28 October 1940) was an English historian and archivist. He served as Deputy Keeper of the Public Records from 1886 to 1926, and was the author of numerous books including a h ...

's ''Eton College''.

Before Praed left school he had established, over a shop at Eton, a "boys' library," the books of which were later amalgamated in the School Library. His career at Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any ...

was a brilliant one. He gained the Browne medal

The Browne Medals (also known as the Sir William Browne's Medals)

''Cambridge University Reporter'', 7 November 2008

for ''Cambridge University Reporter'', 7 November 2008

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

verse four times and the Chancellor's Gold Medal

The Chancellor's Gold Medal is annual award for poetry open to undergraduates at the University of Cambridge, paralleling Oxford University's Newdigate Prize. It was first presented by Prince William Frederick, Duke of Gloucester and Edinburgh ...

for English verse twice in 1823 and 1824. He was bracketed third in the classical tripos in 1825, won a fellowship at his college in 1827, and three years later carried off the Seatonian prize. At the Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Unio ...

his speeches were rivalled only by those of Macaulay and of Charles Austin, who subsequently made a great reputation at the parliamentary bar

In the United Kingdom, the parliamentary bar refers to the subset of barristers who appear at the committee stage of private and hybrid bills which are before Parliament.

The parliamentary bar was especially prominent in the 19th century during t ...

. The character of Praed during his university life is described by Bulwer-Lytton in the first volume of his ''Life''.

Political career

Praed began to study law, and in 1829 was called to the bar at theMiddle Temple

The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple, commonly known simply as Middle Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court entitled to Call to the bar, call their members to the English Bar as barristers, the others being the Inner Temple (with whi ...

. On the Norfolk

Norfolk ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in England, located in East Anglia and officially part of the East of England region. It borders Lincolnshire and The Wash to the north-west, the North Sea to the north and eas ...

circuit, his prospects of advancement were bright, but his inclination was towards politics, and after a year or two he took up political life. Whilst at Cambridge he tended to Whiggism

Whiggism or Whiggery is a political philosophy that grew out of the Roundhead, Parliamentarian faction in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms (1639–1653) and was concretely formulated by Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury, Lord Shafte ...

, and up to the end of 1829 he continued to have these sympathies, but during the agitation for parliamentary reform his opinions changed, and when he was returned to parliament for St Germans (17 December 1830), his election was due to the Tory

A Tory () is an individual who supports a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalist conservatism which upholds the established social order as it has evolved through the history of Great Britain. The To ...

party. He sat for that borough until December 1832, and on its extinction contested the borough of St Ives, within the limits of which the Cornish estates of the Praeds were situated.

The pieces he wrote on this occasion were collected in a volume printed at Penzance

Penzance ( ; ) is a town, civil parish and port in the Penwith district of Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is the westernmost major town in Cornwall and is about west-southwest of Plymouth and west-southwest of London. Situated in the ...

in 1833 and entitled ''Trash'', dedicated without respect to James Halse, M.P., his successful opponent. Praed sat for Great Yarmouth

Great Yarmouth ( ), often called Yarmouth, is a seaside resort, seaside town which gives its name to the wider Borough of Great Yarmouth in Norfolk, England; it straddles the River Yare and is located east of Norwich. Its fishing industry, m ...

from 1835 to 1837, and was Secretary to the Board of Control

The Secretary to the Board of Control was a British government office in the late 18th and early 19th century, supporting the President of the Board of Control, who was responsible for overseeing the British East India Company and generally servin ...

during Sir Robert Peel

Sir Robert Peel, 2nd Baronet (5 February 1788 – 2 July 1850), was a British Conservative statesman who twice was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1834–1835, 1841–1846), and simultaneously was Chancellor of the Exchequer (1834–183 ...

's short administration. He sat for Aylesbury

Aylesbury ( ) is the county town of Buckinghamshire, England. It is home to the Roald Dahl Children's Gallery and the Aylesbury Waterside Theatre, Waterside Theatre. It is located in central Buckinghamshire, midway between High Wycombe and Milt ...

from 1837 until his death. During the progress of the Reform Act 1832

The Representation of the People Act 1832 (also known as the Reform Act 1832, Great Reform Act or First Reform Act) was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom (indexed as 2 & 3 Will. 4. c. 45), enacted by the Whig government of Pri ...

he advocated the creation of three-cornered constituencies, in which each voter should have the power of giving two votes only, and maintained that freehold

Freehold may refer to:

In real estate

*Freehold (law), the tenure of property in fee simple

* Customary freehold, a form of feudal tenure of land in England

*Parson's freehold, where a Church of England rector or vicar of holds title to benefice ...

s within borough

A borough is an administrative division in various English language, English-speaking countries. In principle, the term ''borough'' designates a self-governing walled town, although in practice, official use of the term varies widely.

History

...

s should confer votes for the boroughs and not for the county. Neither of these suggestions was then adopted, but the former ultimately formed part of the Reform Act 1867

The Representation of the People Act 1867 ( 30 & 31 Vict. c. 102), known as the Reform Act 1867 or the Second Reform Act, is an act of the British Parliament that enfranchised part of the urban male working class in England and Wales for the ...

.

Personal life

In 1835, he married Helen Bogle. He died oftuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

at Chester Square, London, at age 36.

Works

W. Mackworth Praed was famed for his verse charades.. H. Austin Dobson praised Praed's "sparkling wit, the clearness and finish of his style, and the flexibility and unflagging vivacity of his rhythm" (Humphry Ward

Thomas Humphry Ward (9 November 1845 – 6 May 1926) was an English author and journalist, (usually writing as Humphry Ward) best known as the husband of the author Mary Augusta Ward, who wrote under the name Mrs. Humphry Ward.

Life

He was bo ...

's ''English Poets''). His verse abounded in allusions to the characters and follies of the day. His humour was much imitated.

His poems were first edited by Rufus Wilmot Griswold

Rufus Wilmot Griswold (February 13, 1815 – August 27, 1857) was an American anthologist, editor, poet, and critic. Born in Vermont, Griswold left home when he was 15 years old. He worked as a journalist, editor, and critic in Philadelphia, New ...

(New York, 1844); another American edition, by W. A. Whitmore, appeared in 1859; an authorized edition with a memoir by Derwent Coleridge

Derwent Coleridge (14 September 1800 – 28 March 1883), third son of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, was a distinguished English scholar and author.

Early life

Derwent Coleridge was born at Keswick, Cumbria, Keswick, Cumberland, 14 September 1800 ...

appeared in 1864: ''The Political and Occasional Poems of W. M. Praed'' (1888), edited with notes by his nephew, Sir George Young

George Samuel Knatchbull Young, Baron Young of Cookham, (born 16 July 1941), known as Sir George Young, 6th Baronet from 1960 to 2015, is a British Conservative Party (UK), Conservative Party politician who served as a Member of Parliament (Un ...

, included many pieces collected from various newspapers and periodicals. Sir George Young separated from his work some poems, the work of his friend Edward FitzGerald, generally confused with his. Praed's essays, contributed to various magazines, were published in Morley's ''Universal Library'' in 1887.

Legacy

Praed was not only successful at Eton during his lifetime, but a society still exists that bears his name. The "Praed" society is the poetry society currently existing at Eton. It meets at a master's house and membership is by invitation.References

Citations

Sources

*External links

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Praed, Winthrop Mackworth 1802 births 1839 deaths 19th-century deaths from tuberculosis Tuberculosis deaths in England Members of the Middle Temple Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for English constituencies People educated at Eton College UK MPs 1830–1831 UK MPs 1831–1832 UK MPs 1835–1837 UK MPs 1837–1841 Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge Politics of the Borough of Great Yarmouth English male poets 19th-century English poets English barristers 19th-century English male writers