Vyvyan Pope on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

/ref>

Following the outbreak of the

Following the outbreak of the

On the outbreak of the

On the outbreak of the Generals.dk

/ref> In April 1940, he was appointed Inspector of the

Generals of World War II

Lancing College War Memorial

Relevant archives

held at the

Lieutenant-General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the battlefield, who was normall ...

Vyvyan Vavasour Pope CBE

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding valuable service in a wide range of useful activities. It comprises five classes of awards across both civil and military divisions, the most senior two o ...

DSO MC & Bar

Bar or BAR may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bar (establishment), selling alcoholic beverages

* Candy bar

** Chocolate bar

* Protein bar

Science and technology

* Bar (river morphology), a deposit of sediment

* Bar (tropical cyclone), a laye ...

(30 September 1891 – 5 October 1941) was a senior British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

officer

An officer is a person who has a position of authority in a hierarchical organization. The term derives from Old French ''oficier'' "officer, official" (early 14c., Modern French ''officier''), from Medieval Latin ''officiarius'' "an officer," fro ...

who was prominent in developing ideas about the use of armour

Armour (Commonwealth English) or armor (American English; see American and British English spelling differences#-our, -or, spelling differences) is a covering used to protect an object, individual, or vehicle from physical injury or damage, e ...

in battle in the interwar years

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period, also known as the interbellum (), lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days) – from the end of World War I (WWI) to the beginning of World War II ( ...

, and who briefly commanded XXX Corps during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

before dying in an air crash.

Early life and education

Vyvyan Pope was born on 30 September 1891 inLondon

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, the son of James Pope, a civil servant

The civil service is a collective term for a sector of government composed mainly of career civil service personnel hired rather than elected, whose institutional tenure typically survives transitions of political leadership. A civil service offic ...

, and his wife Blanche Holmwood ( Langdale) Pope. He was educated at Ascham St Vincent's School

Ascham St Vincent's School was an England, English Preparatory school (UK), preparatory school for boys at Eastbourne, East Sussex. Like other preparatory schools, its purpose was to train pupils to do well enough in the examinations (usually ...

, an all-boys preparatory school in Eastbourne

Eastbourne () is a town and seaside resort in East Sussex, on the south coast of England, east of Brighton and south of London. It is also a non-metropolitan district, local government district with Borough status in the United Kingdom, bor ...

, Sussex

Sussex (Help:IPA/English, /ˈsʌsɪks/; from the Old English ''Sūþseaxe''; lit. 'South Saxons'; 'Sussex') is an area within South East England that was historically a kingdom of Sussex, kingdom and, later, a Historic counties of England, ...

, and then at Lancing College

Lancing College is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school (English Private schools in the United Kingdom, private boarding school, boarding and day school) for pupils aged 13–18 in southern England, UK. The school is located in West S ...

, an all-boys boarding

Boarding may refer to:

*Boarding, used in the sense of "room and board", i.e. lodging and meals as in a:

**Boarding house

**Boarding school

*Boarding (horses) (also known as a livery yard, livery stable, or boarding stable), is a stable where hor ...

private school

A private school or independent school is a school not administered or funded by the government, unlike a State school, public school. Private schools are schools that are not dependent upon national or local government to finance their fina ...

in Lancing, Sussex. He was at Lancing from September 1906 to December 1910 and was a member of the school's football team

A football team is a group of players selected to play together in the various team sports known as football. Such teams could be selected to play in a match against an opposing team, to represent a football club, group, state or nation, an All-st ...

and its Officer Training Corps (where he reached the rank of sergeant

Sergeant (Sgt) is a Military rank, rank in use by the armed forces of many countries. It is also a police rank in some police services. The alternative spelling, ''serjeant'', is used in The Rifles and in other units that draw their heritage f ...

). He was a member of Seconds House and he served as house captain in 1910.

Military career

Early military career

On 8 March 1911, Pope was commissioned as a second lieutenant (on probation) in the 4th Battalion,Prince of Wales's (North Staffordshire Regiment)

The North Staffordshire Regiment (Prince of Wales's) was a line infantry regiment of the British Army, which was in existence between 1881 and 1959. The 64th (2nd Staffordshire) Regiment of Foot was created on 21 April 1758 from the 2nd Battali ...

, as part of the Special Reserve

The Special Reserve was established on 1 April 1908 with the function of maintaining a reservoir of manpower for the British Army and training replacement drafts in times of war. Its formation was part of the military reforms implemented by Ri ...

of the British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

. The Special Reserve were volunteer reservists (i.e. part-time soldiers) who had not previously served in the military. His commission and rank were confirmed on 24 October 1911. In October 1912, he sat and passed the Competitive Examination of Officers of the Special Reserve, Militia, and Territorial Forces.

Pope was now eligible to transfer from the reserves to the regular army

A regular army is the official army of a state or country (the official armed forces), contrasting with irregular forces, such as volunteer irregular militias, private armies, mercenaries, etc. A regular army usually has the following:

* a ...

and made the move on 4 December 1912. He became the junior subaltern of the 1st Battalion, North Staffordshire Regiment, then serving as part of the 17th Brigade of the 6th Division. During this period, he saw service in Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

.Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives/ref>

First World War

Following the outbreak of the

Following the outbreak of the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

in August 1914, the battalion was transferred to England and embarked for the Western Front the following month. Pope remained with the battalion for most of the war, seeing action in the First Battle of Ypres

The First Battle of Ypres (, , – was a battle of the First World War, fought on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front around Ypres, in West Flanders, Belgium. The battle was part of the First Battle of Flanders, in which German A ...

in late 1914, in the Battle of Neuve Chapelle

The Battle of Neuve Chapelle (10–13 March 1915) took place in the First World War in the Artois region of France. The attack was intended to cause a rupture in the German lines, which would then be exploited with a rush to the Aubers Ridge an ...

(where he won the Military Cross

The Military Cross (MC) is the third-level (second-level until 1993) military decoration awarded to officers and (since 1993) Other ranks (UK), other ranks of the British Armed Forces, and formerly awarded to officers of other Commonwealth of ...

) in 1915, in the two serious gas attacks at Wulverghem in April and June 1916 (in the first of which his actions won him the DSO), in the Battle of the Somme

The Battle of the Somme (; ), also known as the Somme offensive, was a battle of the First World War fought by the armies of the British Empire and the French Third Republic against the German Empire. It took place between 1 July and 18 Nove ...

in mid-1916 and in the Battle of Messines in mid-1917. His MC citation states the following:

The citation for his DSO reads

He also participated in the Christmas truce

The Christmas truce (; ; ) was a series of widespread unofficial ceasefires along the Western Front of the First World War around Christmas 1914.

The truce occurred five months after hostilities had begun. Lulls occurred in the fighting a ...

of 1914. In June 1917, having returned from being wounded for the second time at Messines, and now a captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

with the acting rank of lieutenant-colonel, he took over command of 1/North Staffs just in time to see the battalion, now serving as part of the 72nd Brigade of the 24th Division, take a prominent role in the Battle of Passchendaele

The Third Battle of Ypres (; ; ), also known as the Battle of Passchendaele ( ), was a campaign of the First World War, fought by the Allies of World War I, Allies against the German Empire. The battle took place on the Western Front (World Wa ...

(also known as the Third Battle of Ypres).

Second Lieutenant Bernard Martin of D Company, 1st Battalion, North Staffs would later write that, some days before the 31 July 1917 attack on Jehovah and Jordan Trenches near Zandvoorde, Pope had ordered, to the surprise of his officers, that the attacking lines were, "not to charge at the double across No-Man's-Land as in the old tactics but to walk at a steady pace towards Jehovah". Under orders from High Command, the battalion was able to "charge" only after taking Jordan Trench. Starting the day with an estimated 550 rifles, the battalion lost 50 per cent of their attacking force: 4 officers killed and 7 wounded, 38 other ranks killed and 210 wounded, and 10 missing presumed killed.

On 21 March 1918, the battalion was in front-line trenches near Saint-Quentin when the Germans began Operation Michael

Operation Michael () was a major German military offensive during World War I that began the German spring offensive on 21 March 1918. It was launched from the Hindenburg Line, in the vicinity of Saint-Quentin, France. Its goal was to bre ...

, the opening attack in their Spring Offensive. There were extensive casualties, and in a highly confused and fluid situation, Pope received a bullet wound in the right elbow. By the time he reached a hospital gas gangrene

Gas gangrene (also known as clostridial myonecrosis) is a bacterial infection that produces tissue gas in gangrene. This deadly form of gangrene usually is caused by '' Clostridium perfringens'' bacteria. About 1,000 cases of gas gangrene are r ...

had set in, and his right arm had to be amputated. Every year thereafter he drank a glass of port

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as Hamburg, Manch ...

on 21 March in memory of his fallen comrades. Following his discharge from hospital Pope attempted to find a route back into military service but before he could do so the Armistice with Germany {{Short description, none

This is a list of armistices signed by the German Empire (1871–1918) or Nazi Germany (1933–1945). An armistice is a temporary agreement to cease hostilities. The period of an armistice may be used to negotiate a peace t ...

had been signed.

Between the wars

Pope managed to secure a position in 1919 in the North Russia Relief Force, part of the Allied intervention on the side of the White forces in theRussian Civil War

The Russian Civil War () was a multi-party civil war in the former Russian Empire sparked by the 1917 overthrowing of the Russian Provisional Government in the October Revolution, as many factions vied to determine Russia's political future. I ...

. Having reached Arkhangelsk

Arkhangelsk (, ) is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative center of Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia. It lies on both banks of the Northern Dvina near its mouth into the White Sea. The city spreads for over along the ...

, he took command of a Slavo-British unit largely made up of prisoners freed from Arkhangelsk prison but the exercise was not a success.

On his return to Britain, and following a brief period of service with the 2nd Battalion, North Staffordshire Regiment in Ireland, he transferred in April 1920 to the Royal Tank Corps

The Royal Tank Regiment (RTR) is the oldest tank unit in the world, being formed by the British Army in 1916 during the First World War. Today, it is an armoured regiment equipped with Challenger 2 main battle tanks and structured under 12th A ...

(RTC). He promptly returned to Ireland with an armoured car company and saw action in the Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence (), also known as the Anglo-Irish War, was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (1919–1922), Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and Unite ...

. In 1922 he took command for a short period of the 3rd Armoured Car Company in Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

but then again returned to Britain.

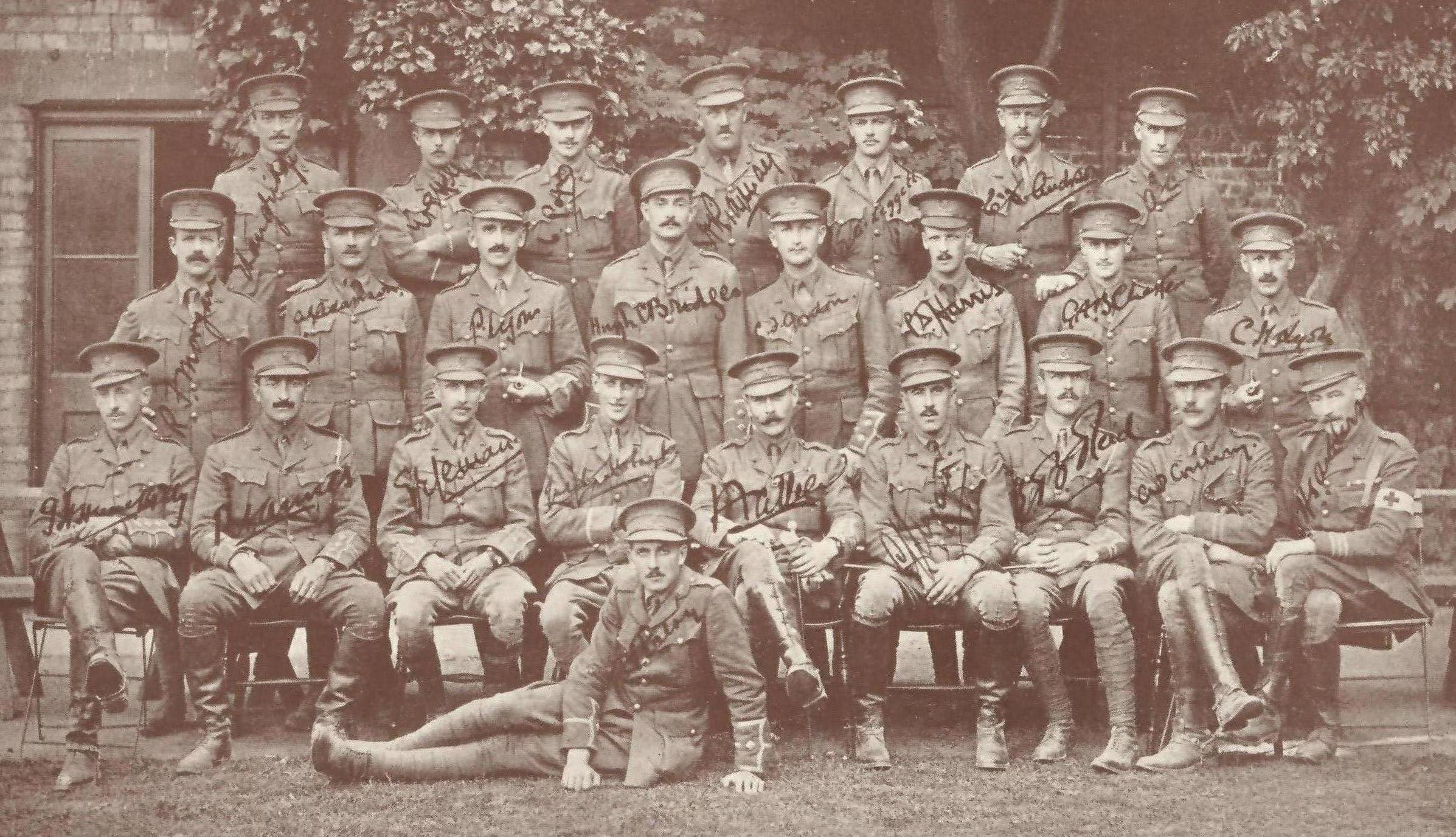

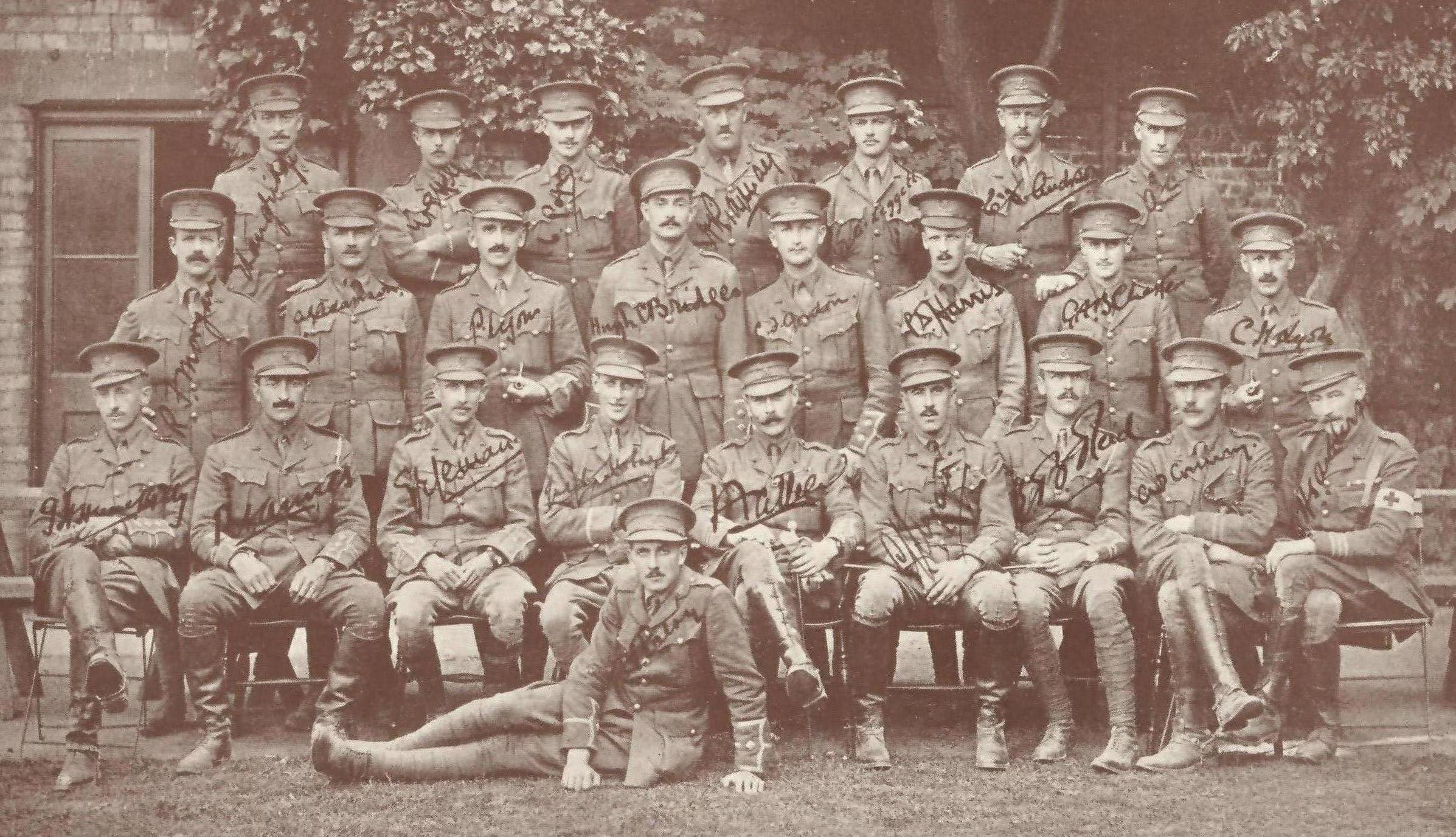

He attended the Staff College, Camberley

Staff College, Camberley, Surrey, was a staff college for the British Army and the presidency armies of British India (later merged to form the Indian Army). It had its origins in the Royal Military College, High Wycombe, founded in 1799, which ...

from 1924 to 1925, and served alongside numerous future general officer

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

s, most notably Humfrey Gale, Archibald Nye

Lieutenant-general (United Kingdom), Lieutenant-General Sir Archibald Edward Nye (23 April 1895 – 13 November 1967), was a senior British Army officer who served in both world wars. In the latter he served as Vice Chief of the General Staff (U ...

, Ivor Thomas, Willoughby Norrie, Thomas Riddell-Webster, Reade Godwin-Austen

General Sir Alfred Reade Godwin-Austen, (17 April 1889 – 20 March 1963) was a British Army officer who served during the First and the Second World Wars.

Early life and military career

The second son of Lieutenant Colonel A. G. Godwin-Austen ...

, Noel Irwin

Lieutenant General Noel Mackintosh Stuart Irwin, (24 December 1892 – 21 December 1972) was a senior British Army officer, who played a prominent role in the British Army after the Dunkirk evacuation and in the Burma campaign during the Second ...

, Noel Beresford-Peirse

Lieutenant-General Sir Noel Monson de la Poer Beresford-Peirse KBE, CB, DSO (22 December 1887 – 14 January 1953) was a British Army officer.

Family background

Beresford-Peirse was the son of Colonel William John de la Poer Beresford-Pei ...

, Michael Creagh, Geoffrey Raikes, Thomas Riddell-Webster, Daril Watson and Douglas Graham. In 1926 he was appointed brigade major

A brigade major was the chief of staff of a brigade in the British Army. They most commonly held the rank of major, although the appointment was also held by captains, and was head of the brigade's "G - Operations and Intelligence" section direct ...

to the Royal Tank Corps Centre, Bovington, where he was at the centre of emerging ideas about the use of armour

Armour (Commonwealth English) or armor (American English; see American and British English spelling differences#-our, -or, spelling differences) is a covering used to protect an object, individual, or vehicle from physical injury or damage, e ...

in battle. He held a post as a General Staff Officer

A military staff or general staff (also referred to as army staff, navy staff, or air staff within the individual services) is a group of officers, Enlisted rank, enlisted, and civilian staff who serve the commanding officer, commander of a ...

(GSO) at Southern Command from 1928 to 1930 and at the War Office

The War Office has referred to several British government organisations throughout history, all relating to the army. It was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, at ...

from 1930 to 1933. and attended the Imperial Defence College

The Royal College of Defence Studies (RCDS) instructs the most promising senior officers of the British Armed Forces, His Majesty's Diplomatic Service and Civil Service in national defence and international security matters at the highest level ...

in 1934. In 1935, at the time of the Italo-Abyssinian War, he was posted by Brigadier

Brigadier ( ) is a military rank, the seniority of which depends on the country. In some countries, it is a senior rank above colonel, equivalent to a brigadier general or commodore (rank), commodore, typically commanding a brigade of several t ...

Percy Hobart

Major-General Sir Percy Cleghorn Stanley Hobart, (14 June 1885 – 19 February 1957), also known as "Hobo", was a British military engineer noted for his command of the 79th Armoured Division during the Second World War. He was responsible for ...

to Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

, as Commander of the Royal Tank Corps there, with a brief to promote the advantages of mechanised forces: the episode taught him valuable lessons about the challenges of operating vehicles in a desert. In June 1936 he was posted to the Directorate of Military Training at the War Office under a former Staff College instructor, Alan Brooke

Field Marshal Alan Francis Brooke, 1st Viscount Alanbrooke (23 July 1883 – 17 June 1963), was a senior officer of the British Army. He was Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS), the professional head of the British Army, during the Secon ...

; and in 1938 to the General Staff of Southern Command.

Second World War

Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

in September 1939, Pope was appointed Chief of Staff to II Corps, which had been mobilised at Salisbury

Salisbury ( , ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and civil parish in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers River Avon, Hampshire, Avon, River Nadder, Nadder and River Bourne, Wi ...

under Brooke's command. Pope designed II Corps' badge of a salmon leaping over a stylised "brook", as a play on his commander's name. At the end of September 1939 the corps crossed to France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

to join the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). Pope went with them but returned to England in December to take command of the 3rd Armoured Brigade, part of the 1st Armoured Division ( Major-General Roger Evans)./ref> In April 1940, he was appointed Inspector of the

Royal Armoured Corps

The Royal Armoured Corps is the armoured arm of the British Army, that together with the Household Cavalry provides its armour capability, with vehicles such as the Challenger 2 and the Warrior tracked armoured vehicle. It includes most of the Ar ...

(RAC). He was then posted as Adviser on Armoured Fighting Vehicles (AFV) on General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

Lord Gort's staff at BEF headquarters in France. He soon contrived to become more closely involved in the fighting and was a prominent commander in the Allied counter-attack at Arras on 21 May, which, although it did not halt the advancing Germans, shook their confidence.

The BEF was forced to retreat and at the end of May, Pope was evacuated from Dunkirk

Dunkirk ( ; ; ; Picard language, Picard: ''Dunkèke''; ; or ) is a major port city in the Departments of France, department of Nord (French department), Nord in northern France. It lies from the Belgium, Belgian border. It has the third-larg ...

. He returned to the War Office

The War Office has referred to several British government organisations throughout history, all relating to the army. It was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, at ...

, where he was appointed Director of Armoured Fighting Vehicles in June 1940. While in this post he played a key role in initiating production of the A22 tank (afterwards known as the Churchill tank

The Tank, Infantry, Mk IV (A22) Churchill was a British infantry tank used in the Second World War, best known for its heavy armour, large longitudinal chassis with all-around tracks with multiple Bogie#Tracked vehicles, bogies, its ability to ...

).

The Western Desert campaign

The Western Desert campaign (Desert War) took place in the Sahara Desert, deserts of Egypt and Libya and was the main Theater (warfare), theatre in the North African campaign of the Second World War. Military operations began in June 1940 with ...

now assumed a growing importance in strategic thinking, and by the summer of 1941 an offensive in the desert against the Axis named Operation Crusader

Operation Crusader (18 November – 30 December 1941) was a military operation of the Western Desert campaign during World War II by the British Eighth Army (with Commonwealth, Indian and Allied contingents) against the Axis forces (German and ...

was being planned. It was to be fought by the new Eighth Army (Lieutenant-General Sir Alan Cunningham

Sir Alan Gordon Cunningham, (1 May 1887 – 30 January 1983), was a senior Officer (armed forces), officer of the British Army noted for his victories over Italian forces in the East African Campaign (World War II), East African Campaign duri ...

), comprising XIII Corps, an infantry corps and XXX Corps, a predominantly armoured corps. In August 1941 Pope was appointed General Officer Commanding

General officer commanding (GOC) is the usual title given in the armies of the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth (and some other nations, such as Ireland) to a general officer who holds a command appointment.

Thus, a general might be the GOC ...

(GOC) XXX Corps. He flew to Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

in September and assembled a staff but on 5 October, ''en route'' to Cunningham's first conference on the forthcoming battle, his Hudson

Hudson may refer to:

People

* Hudson (given name)

* Hudson (surname)

* Hudson (footballer, born 1986), Hudson Fernando Tobias de Carvalho, Brazilian football right-back

* Hudson (footballer, born 1988), Hudson Rodrigues dos Santos, Brazilian f ...

aircraft ran into trouble on taking off from Heliopolis, crashed in the Mocattam Hills and all on board, including Brigadier Hugh Edward Russell, his Brigadier General Staff, were killed. Pope was succeeded as GOC XXX Corps by Lieutenant-General Willoughby Norrie, who had been one of his fellow students at the Staff College, Camberley in the mid-1920s. Although a good soldier, Norrie, a cavalryman, lacked Pope's high ability and intellect.

Personal life

Pope married Sybil Moore in 1926.Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * *External links

Generals of World War II

Lancing College War Memorial

Relevant archives

held at the

Churchill Archives Centre

The Churchill Archives Centre (CAC) at Churchill College at the University of Cambridge is one of the largest repositories in the United Kingdom for the preservation and study of modern personal papers. It is best known for housing the papers ...

, Cambridge

{{DEFAULTSORT:Pope, Vyvyan

1891 births

1941 deaths

Staffordshire Militia officers

Graduates of the Royal College of Defence Studies

British Army personnel of the Russian Civil War

British Army personnel of World War I

British Army generals of World War II

British military personnel of the Irish War of Independence

Commanders of the Order of the British Empire

Companions of the Distinguished Service Order

Graduates of the Staff College, Camberley

North Staffordshire Regiment officers

People educated at Lancing College

Recipients of the Military Cross

Royal Tank Regiment officers

Victims of aviation accidents or incidents in Egypt

War Office personnel in World War II

British Army personnel killed in World War II

English amputees

British Army lieutenant generals

Military personnel from London

Participants of the Christmas truce of 1914

Victims of aviation accidents or incidents in 1941