Vera Atkins on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Vera May Atkins (15 June 1908 – 24 June 2000) was a Romanian-born British

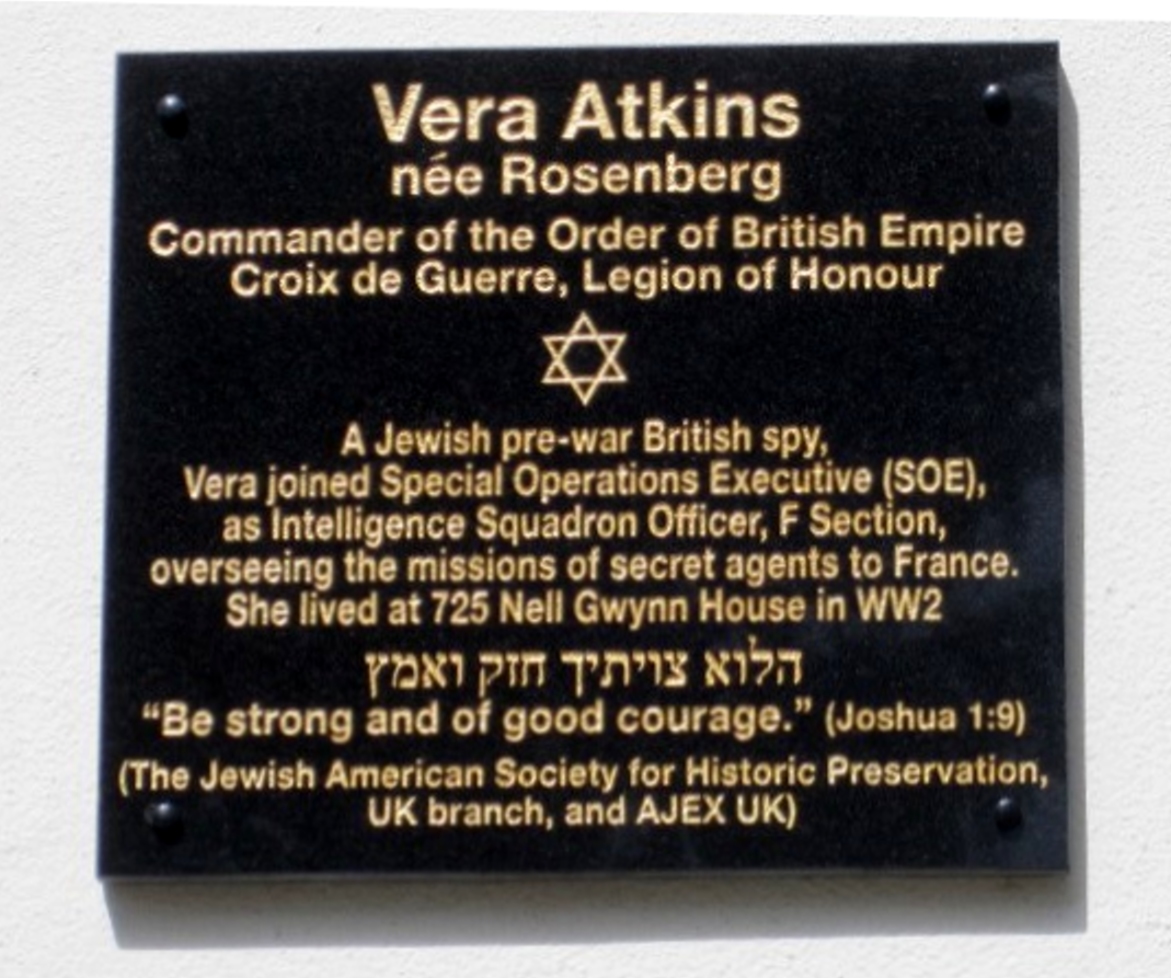

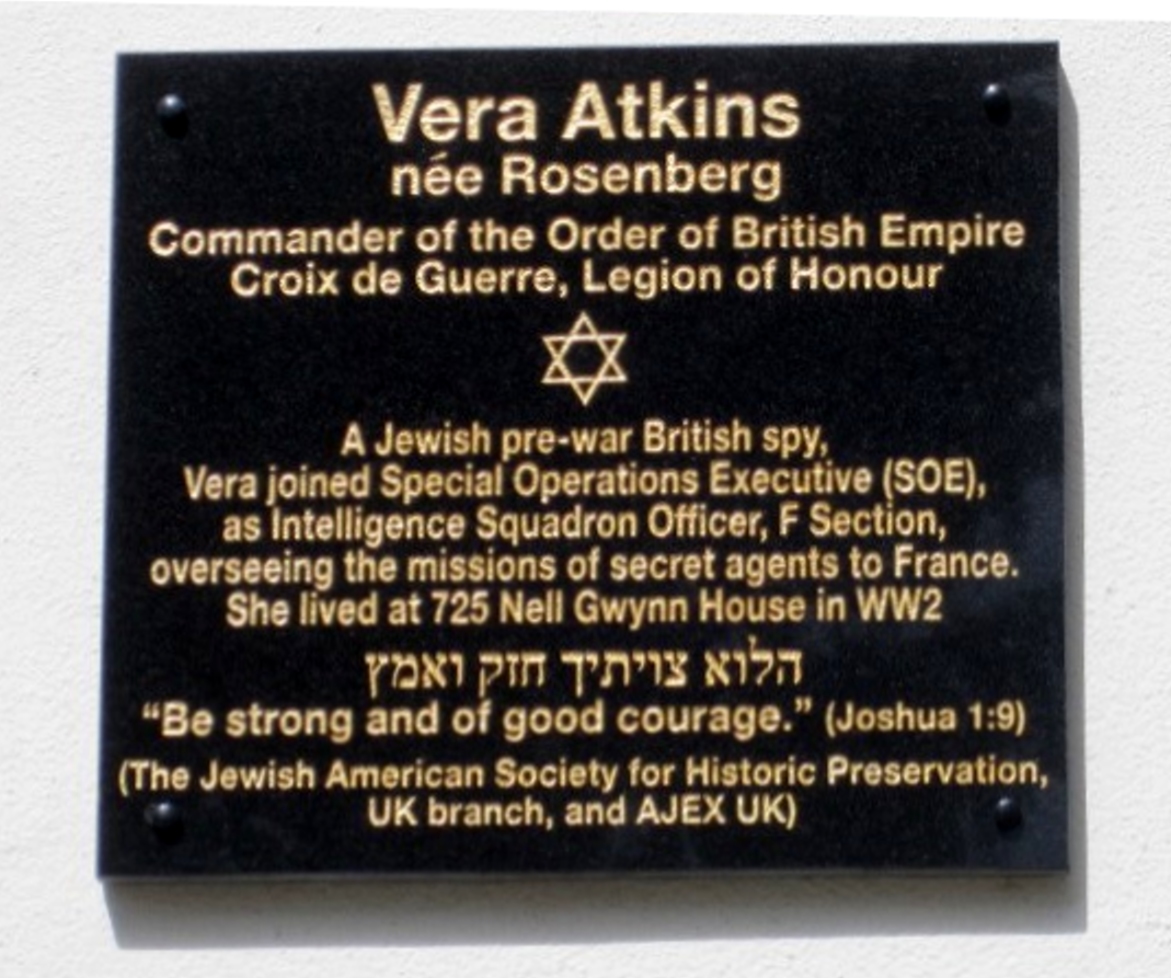

In 2022, a historical plaque was placed at Nell Gwynn House, near Sloane Square, London, where Vera lived during WW2, by the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation, U.K. Branch and the (British) Association of Jewish Ex-Servicemen and Women, Stamford Hill Branch.

In 2022, a historical plaque was placed at Nell Gwynn House, near Sloane Square, London, where Vera lived during WW2, by the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation, U.K. Branch and the (British) Association of Jewish Ex-Servicemen and Women, Stamford Hill Branch.

Atkins, Vera May (Oral history)

Imperial War Museums

Host Aaron Berg welcomes back historian Andrew Davidsberg for a deep dive into the life of Vera Atkins (podcast)

DIGA Studios {{DEFAULTSORT:Atkins, Vera 1908 births 2000 deaths British Special Operations Executive personnel Commanders of the Order of the British Empire Commanders of the Legion of Honour Naturalised citizens of the United Kingdom People from Bucharest People from Galați Recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1939–1945 (France) Romanian Jews Romanian people of British descent Romanian people of German descent University of Paris alumni Women's Auxiliary Air Force officers People from Winchelsea Romanian emigrants to the United Kingdom Romanian expatriates in France Romanian expatriates in Switzerland Romanian women in World War II British people of German-Jewish descent

intelligence officer

An intelligence officer is a member of the intelligence field employed by an organization to collect, compile or analyze information (known as intelligence) which is of use to that organization. The word of ''officer'' is a working title, not a r ...

who worked in the France Section of the Special Operations Executive

Special Operations Executive (SOE) was a British organisation formed in 1940 to conduct espionage, sabotage and reconnaissance in German-occupied Europe and to aid local Resistance during World War II, resistance movements during World War II. ...

(SOE) from 1941 to 1945 during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

Early life

Atkins was born Vera May Rosenberg inGalați

Galați ( , , ; also known by other #Etymology and names, alternative names) is the capital city of Galați County in the historical region of Western Moldavia, in eastern Romania. Galați is a port town on the river Danube. and the sixth-larges ...

, Kingdom of Romania

The Kingdom of Romania () was a constitutional monarchy that existed from with the crowning of prince Karl of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen as King of Romania, King Carol I of Romania, Carol I (thus beginning the Romanian royal family), until 1947 wit ...

, to Max Rosenberg (d. 1932), a German-Jewish

The history of the Jews in Germany goes back at least to the year 321 CE, and continued through the Early Middle Ages (5th to 10th centuries CE) and High Middle Ages (c. 1000–1299 CE) when Jewish immigrants founded the Ashkenazi Jewish commu ...

father, and his British-Jewish wife, Zefra Hilda, known as Hilda (d. 1947). She had two brothers.

Atkins briefly attended the Sorbonne in Paris to study modern languages and a finishing school at Lausanne

Lausanne ( , ; ; ) is the capital and largest List of towns in Switzerland, city of the Swiss French-speaking Cantons of Switzerland, canton of Vaud, in Switzerland. It is a hilly city situated on the shores of Lake Geneva, about halfway bet ...

, where she indulged her passion for skiing, before training at a secretarial college in London. Atkins' father, a wealthy businessman on the Danube Delta

The Danube Delta (, ; , ) is the second largest river delta in Europe, after the Volga Delta, and is the best preserved on the continent. Occurring where the Danube, Danube River empties into the Black Sea, most of the Danube Delta lies in Romania ...

, went bankrupt in 1932 and died a year after. Atkins remained with her mother in Romania until emigrating to Great Britain in 1937, a move made in response to the threatening political situation in mainland Europe.

During her somewhat-gilded youth in Romania, where Atkins lived on the large estate bought by her father at Crasna (now in Ukraine), Atkins enjoyed the cosmopolitan society of Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ) is the capital and largest city of Romania. The metropolis stands on the River Dâmbovița (river), Dâmbovița in south-eastern Romania. Its population is officially estimated at 1.76 million residents within a greater Buc ...

where she became close to the anti-Nazi German ambassador, Friedrich Werner von der Schulenburg (executed after the July 1944 plot). Later Atkins became involved with a young British pilot, Dick Ketton-Cremer, whom she had met in Egypt, and to whom she may have been briefly engaged. He was killed in action in the Battle of Crete

The Battle of Crete (, ), codenamed Operation Mercury (), was a major Axis Powers, Axis Airborne forces, airborne and amphibious assault, amphibious operation during World War II to capture the island of Crete. It began on the morning of 20 May ...

on 23 May 1941. Atkins was never to marry, and lived in a flat with her mother while working for SOE and until 1947 when Hilda died.

While in Romania, Atkins came to know several diplomats who were members of British Intelligence, some of whom were later to support her application for British nationality, and to whom in view of her and her family's strong pro-British views, she may have provided information as a "stringer". Atkins also worked as a translator and representative for an oil company.

The surname "Atkins" was her mother's maiden name and itself an Anglicised version of the original "Etkins", which she adopted as her own. She was a cousin of Rudolf Vrba

Rudolf Vrba (born Walter Rosenberg; 11 September 1924 – 27 March 2006) was a Slovak-Jewish biochemist who, as a teenager in 1942, was deported to the Auschwitz concentration camp in Occupation of Poland (1939–1945), German-occupied Pol ...

.

Atkins was recruited before the war by Canadian spymaster Sir William Stephenson

Sir William Samuel Stephenson (born William Samuel Clouston Stanger, 23 January 1897 – 31 January 1989) was a Canadian soldier, fighter pilot, businessman and spymaster who served as the senior representative of the British Security Coord ...

of British Security Co-ordination

British Security Co-ordination (BSC) was a covert organisation set up in New York City by the British Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) in May 1940 upon the authorisation of the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill.

Its purpose was to investigate ...

. He sent her on fact-finding missions across Europe to supply Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

(then in the 'political wilderness') with intelligence on the rising threat of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

.

First missions of the Second World War

The Polish Cipher Bureau broke Germany's Enigma ciphers from 1932 on, using Enigma-machine reconstructions which they also gave to their British and French allies, following a July 1939 Warsaw conference at which they gave their French and British cryptologist opposite numbers information on the Poles' decrypting techniques and the special-purpose equipment they had invented. According to William Stevenson's ''The Life of Vera Atkins, the Greatest Female Secret Agent of World War II'' (Arcade Publishing, 2006), Atkins' first mission was to get Poland's cryptologistsMarian Rejewski

Marian Adam Rejewski (; 16 August 1905 – 13 February 1980) was a Polish people, Polish mathematician and Cryptography, cryptologist who in late 1932 reconstructed the sight-unseen German military Enigma machine, Enigma cipher machine, aided ...

, Jerzy Różycki, and Henryk Zygalski out of the country, and she was a member of the British military mission (MM-4), alongside Colin Gubbins, which arrived in Poland posing as civilians, by way of Greece and Romania, six days before the outbreak of the war. Atkins may have ''attempted'' to find the cryptologists and get them out of Poland, but as Rejewski describes (see "Marian Rejewski

Marian Adam Rejewski (; 16 August 1905 – 13 February 1980) was a Polish people, Polish mathematician and Cryptography, cryptologist who in late 1932 reconstructed the sight-unseen German military Enigma machine, Enigma cipher machine, aided ...

"), they were in fact evacuated to Romania by the Polish Cipher Bureau, and from Romania to France thanks to Gustave Bertrand of French intelligence; Rejewski makes no mention of ever having met or heard of Vera Atkins.

In the spring of 1940, before joining SOE, Atkins travelled to the Low Countries

The Low Countries (; ), historically also known as the Netherlands (), is a coastal lowland region in Northwestern Europe forming the lower Drainage basin, basin of the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta and consisting today of the three modern "Bene ...

to provide money for a bribe to an Abwehr

The (German language, German for ''resistance'' or ''defence'', though the word usually means ''counterintelligence'' in a military context) ) was the German military intelligence , military-intelligence service for the ''Reichswehr'' and the ...

officer, Hans Fillie, for a passport for her cousin, Fritz, to escape from Romania. Atkins was stranded in the Netherlands when the Germans invaded on 10 May 1940, and, after going into hiding, was able to return to Britain late in 1940 with the assistance of a Belgian resistance network. Atkins kept this episode secret all her life and it only came to light after her death when her biographer, Sarah Helm, tracked down some mourners at Atkins' funeral.

Atkins volunteered as an Air Raid Precautions

Air Raid Precautions (ARP) refers to a number of organisations and guidelines in the United Kingdom dedicated to the protection of civilians from the danger of air raids. Government consideration for air raid precautions increased in the 1920s a ...

warden in Chelsea in the period prior to working for SOE. During this time she lived at Nell Gwynn House in Sloane Avenue in Chelsea.

Special Operations Executive (SOE)

Though not a British national, in February 1941 Atkins joined the French section of the SOE as a secretary. She was soon made assistant to section head Colonel Maurice Buckmaster, and became a de facto intelligence officer. Atkins served as a civilian until August 1944, when she was commissioned aFlight Officer

The title flight officer was a military rank used by the United States Army Air Forces during World War II, and also an air force rank in several Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth countries, where it was used for female officers and was equiv ...

in the Women's Auxiliary Air Force

The Women's Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF), whose members were referred to as WAAFs (), was the female auxiliary of the British Royal Air Force during the World War II, Second World War. Established in 1939, WAAF numbers exceeded 181,000 at its peak ...

(WAAF). In February 1944, Atkins was naturalised as a British subject. She was later appointed F Section's intelligence officer (F-Int).

Atkins' primary role at SOE was the recruitment and deployment of British agents in occupied France. She also had responsibility for the 37 women SOE agents who worked as couriers and wireless operators for the various circuits established by SOE. Atkins would take care of the "housekeeping" related to the agents, such as checking their clothing and papers to ensure they were appropriate for the mission, sending out pre-written anodyne letters at regular intervals, acting as SOE's liaison with their families, and ensuring they received their pay. Atkins would often accompany agents to the airfields from which they would depart for France and carry out final security checks before waving them off.

Atkins always attended the daily section heads meeting chaired by Buckmaster, and would often stay late into the night at the signals room to await the decoded transmissions sent by agents in the field. She would usually arrive at F Section's Baker Street

Baker Street is a street in the Marylebone district of the City of Westminster in London. It is named after builder James Baker. The area was originally high class residential, but now is mainly occupied by commercial premises.

The street is ...

office around 10.00 am. Although not popular with many of her colleagues, Atkins was trusted by Buckmaster for her integrity, exceptional memory and good organisational skills. Tall at 5 ft 9 in., she typically dressed in tailored skirt-suits. She was a lifelong smoker, preferring the " Senior Service" brand.

Controversy

Controversy has lasted in certain circles as to how and why clues that one of F section's main spy networks had been penetrated by the Germans were not picked up, and Buckmaster and Atkins failed to pull out agents at risk. Instead, they sent in several more. A radio operator for the Prosper circuit, Gilbert Norman ("Archambaud"), had sent a message omitting his ''true security check'' – a deliberate mistake. Atkins, it is alleged, was negligent in letting Buckmaster repeat his errors at the expense of agents' lives, including 27 arrested on landing whom the Germans later killed. Sarah Helm suggests that Atkins, who still had relatives in Nazi-occupied Europe, may have been defensive about her involvement with the Abwehr in the 1940 rescue of her cousin Fritz Rosenberg, something she kept secret from SOE. Furthermore, as a Romanian who had not yet obtained British citizenship, Atkins was legally anenemy alien

In customary international law, an enemy alien is any alien native, citizen, denizen or subject of any foreign nation or government with which a domestic nation or government is in conflict and who is liable to be apprehended, restrained, secur ...

and highly vulnerable. Whatever the truth, Buckmaster was Atkins' superior officer, and thus ultimately responsible for running SOE's French agents, and she remained a civilian and not even a British national until February 1944. It was Buckmaster who sent a reply to the message supposedly sent by Norman telling him, and thus the actual German operator, that he had forgotten his "true" check and to remember it in the future.

On 1 October 1943, F-Section received a message from "Jacques", an agent in Berne, passing on information from "Sonja" that "Madeleine" and two others had had "a serious accident and were in hospital" – code for captured by the German authorities. "Jacques" was an SOE radio operator, Jacques Weil of the Juggler circuit, who had escaped to Switzerland, "Sonja" was his fiancée, Sonia Olschanezky, who was still operating in Paris, and "Madeleine" was Noor Inayat Khan, a wireless operator of the Cinema circuit. This accurate information was not acted upon by Buckmaster, probably because "Sonja" was a locally recruited agent unknown to him, and F-Section continued to regard "Madeleine's" messages as genuine for several months after Noor's arrest. There is no evidence that Atkins was aware of this message, and as she was later to misidentify Sonia as Noor because she was unaware the former was an SOE operative, the responsibility for ignoring Sonia's communication and continuing to send agents to the blown Prosper circuit and sub-circuits in Paris, and so to their capture and often death, must lie with Buckmaster and not Atkins, as with the case of "Archambaud" above.

It was not until after the end of the war that Atkins learnt of the almost total success the Germans had had by 1943 in destroying SOE networks in the Low Countries by playing the Englandspiel ("England game"), by which radio operators were captured and forced to give up their codes and "bluffs", so that German intelligence (Abwehr in the Netherlands; Sicherheitsdienst

' (, "Security Service"), full title ' ("Security Service of the ''Reichsführer-SS''"), or SD, was the intelligence agency of the Schutzstaffel, SS and the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany. Established in 1931, the SD was the first Nazi intelligence ...

(SD) in France) officers could impersonate the agents and play them back against in London. For some reason, Buckmaster and Atkins were not informed of the total collapse of the circuits in the Netherlands ( N Section) and Belgium ( T Section) due to the capture and control of wireless operators by the Abwehr.

This may have been a result of inter-departmental or service rivalry, or just bureaucratic incompetence, but the failure of their superiors to tell F Section officially of these other SOE disasters (although rumours about N and T Sections circulated at Baker Street) may have led Buckmaster and Atkins to be overconfident in the security of their networks and too ready to ignore signals evidence that questioned their trust in the identity of the wireless operator.

Notice should also be taken of the well-organised and skillful counter-espionage work of the SD at 84 Avenue Foch in Paris under Hans Josef Kieffer, who built up a deep understanding of how F Section operated in both London and France.

It has been suggested that Atkins' diligence in tracing agents still missing at the end of the war was motivated by a sense of guilt at having sent many to deaths that could have been avoided. It is also possible that she felt it her duty to find out what had happened to the men and women, each known personally to her, who had died serving SOE F Section in the most dangerous of circumstances.

In the end, what caused the complete collapse of the Prosper circuit of Francis Suttill and its extensive network of sub-circuits, were not errors in London, but the actions of Henri Déricourt ("Gilbert"), F Section's air-landing officer in France, who was at the heart of its operations, and who was literally giving SOE's secrets to the SD in Paris. What is not completely clear is whether Déricourt was, as is most likely, simply a traitor, or, as he was to claim, was working for the Secret Intelligence Service

The Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), commonly known as MI6 (MI numbers, Military Intelligence, Section 6), is the foreign intelligence service of the United Kingdom, tasked mainly with the covert overseas collection and analysis of Human i ...

() (unknown to SOE) as part of a complex deception plan in the run-up to D-Day

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on 6 June 1944 of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during the Second World War. Codenamed Operation Neptune and often referred to as ...

. However, it is beyond doubt that Déricourt was at least a double agent, and that he provided, first his friend, Karl Boemelburg, head of the SD in France, and then Kieffer, with large amounts of written evidence and intelligence about F Section's operations and operatives, which ultimately led to the capture, torture and execution of scores of British agents.

The conclusions of M.R.D. Foot in his official history of F Section are that the errors made by Atkins, Buckmaster and other London officers were the products of the "fog of war", that there were no conspiracies behind these failings, and that few individuals were culpable. Sara Helm's conclusions are that the errors were due to "terrible incompetence and tragic mistakes".

Atkins never admitted to making mistakes, and went to considerable lengths to hide her errors, as in her original identification of Noor Inayat Khan, rather than (then unknown to Atkins) Sonia Olschanezky, as the fourth woman executed at Natzweiler-Struthof on 6 July 1944. Indeed, Atkins never informed Sonia's family that Sonia had died at Natzweiler, although she did later protest against the decision of the organising committee of the SOE memorial in Valençay not to include Sonia's name because she was a local agent and not one sent from England.

Search for F Section's missing agents

After theliberation of France

The liberation of France () in the Second World War was accomplished through diplomacy, politics and the combined military efforts of the Allied Powers, Free French forces in London and Africa, as well as the French Resistance.

Nazi Germany in ...

and the allied victory in Europe, Atkins went to both France, and later to Germany for four days, where she was determined to uncover the fates of the fifty-one still unaccounted for F Section agents, of the 118 who had disappeared in enemy territory (117 of whom she was to confirm had died in German captivity). Originally she received little support and some opposition in Whitehall

Whitehall is a road and area in the City of Westminster, Central London, England. The road forms the first part of the A roads in Zone 3 of the Great Britain numbering scheme, A3212 road from Trafalgar Square to Chelsea, London, Chelsea. It ...

, but as the horrors of Nazi atrocities were revealed, and the popular demand for war crimes trials grew, it was decided to give official support for Atkins' quest to find out what had happened to the British agents and to bring those who had perpetrated crimes against them to justice.

At the end of 1945 SOE was wound up, but in January 1946 Atkins, now funded on the establishment of the Secret Intelligence Service

The Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), commonly known as MI6 (MI numbers, Military Intelligence, Section 6), is the foreign intelligence service of the United Kingdom, tasked mainly with the covert overseas collection and analysis of Human i ...

(), arrived in Germany as a newly promoted Squadron Officer in the Women's Auxiliary Air Force

The Women's Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF), whose members were referred to as WAAFs (), was the female auxiliary of the British Royal Air Force during the World War II, Second World War. Established in 1939, WAAF numbers exceeded 181,000 at its peak ...

to begin her search for the missing agents, including 14 women. Atkins was attached to the war crimes unit of the Judge Advocate-General's department of the British Army at Bad Oeynhausen

Bad Oeynhausen () is a spa town on the southern edge of the Wiehengebirge in the district of Minden-Lübbecke in the Ostwestfalen-Lippe, East-Westphalia-Lippe region of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. The closest larger towns are Bielefeld (39 ki ...

, which was under the command of Group Captain Tony Somerhaugh.

Until her return to Britain in October 1946, Atkins searched for the missing SOE agents and other intelligence service personnel who had gone missing behind enemy lines, carried out interrogations of Nazi war crimes suspects, including Rudolf Höss

Rudolf Franz Ferdinand Höss (also Höß, Hoeß, or Hoess; ; 25 November 1901 – 16 April 1947) was a German SS officer and the commandant of the Auschwitz concentration camp. After the defeat of Nazi Germany and the end of World War II, he w ...

, ex-commandant of Auschwitz-Birkenau

Auschwitz, or Oświęcim, was a complex of over 40 Nazi concentration camps, concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany, occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) d ...

, and testified as a prosecution witness in subsequent trials. In November 1946, Atkins' commission was extended so that she could return to Germany to assist the prosecution in the Ravensbrück trial which lasted into January 1947. She used this opportunity to complete her search for Noor Inayat Khan, who she now knew had not died at Natzweiler-Struthof, as she had originally concluded in April 1946, but at Dachau.

As well as tracing 117 of the 118 missing F Section agents, Atkins established the circumstances of the deaths of all 14 of the women, twelve of whom had perished in concentration camps: Andrée Borrel, Vera Leigh, Sonia Olschanezky (whom Atkins did not identify until 1947, but knew as the fourth woman to be killed) and Diana Rowden executed at Natzweiler-Struthof by lethal injection on 6 July 1944; Yolande Beekman, Madeleine Damerment, Noor Inayat Khan and Eliane Plewman executed at Dachau on 13 September 1944; Denise Bloch, Lilian Rolfe and Violette Szabo executed by shooting at Ravensbrück on 5 February 1945, and Cecily Lefort executed in the gas chamber at the Uckermark

The Uckermark () is a historical region in northeastern Germany, which straddles the Uckermark (district), Uckermark District of Brandenburg and the Vorpommern-Greifswald District of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. Its traditional capital is Prenzlau.

...

Youth Camp adjacent to Ravensbrück sometime in February 1945. Yvonne Rudellat died of typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposu ...

on 23 or 24 April 1945, eight or nine days after the liberation of Bergen-Belsen

Bergen-Belsen (), or Belsen, was a Nazi concentration camp in what is today Lower Saxony in Northern Germany, northern Germany, southwest of the town of Bergen, Lower Saxony, Bergen near Celle. Originally established as a prisoner of war camp, ...

, and Muriel Byck had died of meningitis in hospital in Romorantin, France, on 25 May 1944. Atkins had also persuaded the War Office that the twelve women, technically regarded as civilians, who had been executed, were not treated as having died in prison, as had been originally intended, but were recorded as killed in action

Killed in action (KIA) is a casualty classification generally used by militaries to describe the deaths of their personnel at the hands of enemy or hostile forces at the moment of action. The United States Department of Defense, for example, ...

.

Atkins' efforts in looking for her missing "girls" meant not only did each now have a place of death, but by detailing their bravery before and after capture, she also helped to ensure that each (except Sonia Olschanezky, unknown to Atkins until 1947) received official recognition by the British Government, including the award of a posthumous George Cross

The George Cross (GC) is the highest award bestowed by the British government for non-operational Courage, gallantry or gallantry not in the presence of an enemy. In the British honours system, the George Cross, since its introduction in 1940, ...

to both Violette Szabo in 1946 and, especially due to Atkins's efforts, Noor Inayat Khan in 1949. (Odette Sansom

Odette Marie Léonie Céline Hallowes, (née Brailly; 28 April 1912 – 13 March 1995), also known as Odette Churchill and Odette Sansom, code named Lise, was an agent for the United Kingdom's clandestine Special Operations Executive (SOE) in ...

, who survived Ravensbrück, also received the GC in 1946.) However, when Atkins did confirm that Sonia Olschanezky had died at Natzweiler-Struthof, she failed to pass the information to Sonia's family.

After the Second World War

Atkins was demobilised in 1947, and although nominated for an MBE, was not awarded a decoration in the postwar honours lists. Atkins went to work forUNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

's Central Bureau for Educational Visits and Exchanges, as office manager from 1948, and director from 1952. She took early retirement in 1961, and retired to Winchelsea

Winchelsea () is a town in the county of East Sussex, England, located between the High Weald and the Romney Marsh, approximately south west of Rye and north east of Hastings. The current town, which was founded in 1288, replaced an earli ...

in East Sussex

East Sussex is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Kent to the north-east, West Sussex to the west, Surrey to the north-west, and the English Channel to the south. The largest settlement ...

.

In 1950, Atkins was an advisor on the film '' Odette'', about Odette Sansom

Odette Marie Léonie Céline Hallowes, (née Brailly; 28 April 1912 – 13 March 1995), also known as Odette Churchill and Odette Sansom, code named Lise, was an agent for the United Kingdom's clandestine Special Operations Executive (SOE) in ...

(by the then wife of Peter Churchill), and in 1958 on the film of ''Carve Her Name With Pride

''Carve Her Name with Pride'' is a 1958 British war Drama (film and television), drama film based on the book of the same name by R. J. Minney.

The film, directed by Lewis Gilbert, is based on the true story of Special Operations Executive agen ...

'', based upon the biography of the same name of Violette Szabo by R. J. Minney. She also assisted Jean Overton Fuller on her 1952 life of Noor Inayat Khan, ''Madelaine'', but their friendship cooled after the author revealed the success of the German Funkspiel against F Section in her 1954 book, ''The Starr Affair'', and Overton Fuller later came to believe that Atkins had been a Soviet agent.

Atkins was also suspected by some former SOE officials of working for the Germans, but Sarah Helm dismisses these claims of her being a Soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

or Nazi spy and suggests that Atkins' less straightforward behaviour and secrecy can be explained by her determination not to reveal her 1940 mission to the continent. Her position as a woman, a Jew and a non-British national in SOE would also explain Atkins' defensiveness during and after the war. Nevertheless, especially given her pre-war contacts and activities, her position does not rule out the possibility either.

Atkins persuaded M.R.D. Foot, SOE's official historian, not to reveal her Romanian origins in his history. She remained to her death a strong defender of F Section's wartime record, and ensured that each of the 12 women who had died in the three Nazi concentration camps

From 1933 to 1945, Nazi Germany operated more than a thousand concentration camps (), including subcamp (SS), subcamps on its own territory and in parts of German-occupied Europe.

The first camps were established in March 1933 immediately af ...

of Natzweiler-Struthof, Dachau and Ravensbrück are commemorated by memorial plaques close to where they were killed. Atkins also supported the memorial at Valençay in the Loire Valley

The Loire Valley (, ), spanning , is a valley located in the middle stretch of the Loire river in central France, in both the administrative regions Pays de la Loire and Centre-Val de Loire. The area of the Loire Valley comprises about . It is r ...

, unveiled in 1991, which is dedicated to the agents of SOE in France killed in the line of duty.

In 1996, Atkins wrote to ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a British daily broadsheet conservative newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed in the United Kingdom and internationally. It was found ...

'' to defend the decision to send Noor Inayat Khan to France, writing of Noor's initial success in evading capture, her two escape attempts, and her detention in Pforzheim

Pforzheim () is a List of cities and towns in Germany, city of over 125,000 inhabitants in the federal state of Baden-Württemberg, in the southwest of Germany.

It is known for its jewelry and watch-making industry, and as such has gained the ...

prison manacled in chains as a dangerous prisoner: "This is the record of Noor Inayat Khan and her answer to those who doubted her."

Honours and decorations

Atkins was appointed CBE in the 1997 Birthday Honours. She was awarded theCroix de Guerre

The (, ''Cross of War'') is a military decoration of France. It was first created in 1915 and consists of a square-cross medal on two crossed swords, hanging from a ribbon with various degree pins. The decoration was first awarded during World ...

in 1948 and made a Knight of the Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour ( ), formerly the Imperial Order of the Legion of Honour (), is the highest and most prestigious French national order of merit, both military and Civil society, civil. Currently consisting of five cl ...

by the French government in 1987.

In 2022, a historical plaque was placed at Nell Gwynn House, near Sloane Square, London, where Vera lived during WW2, by the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation, U.K. Branch and the (British) Association of Jewish Ex-Servicemen and Women, Stamford Hill Branch.

In 2022, a historical plaque was placed at Nell Gwynn House, near Sloane Square, London, where Vera lived during WW2, by the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation, U.K. Branch and the (British) Association of Jewish Ex-Servicemen and Women, Stamford Hill Branch.

Death

Atkins died at a hospital inHastings

Hastings ( ) is a seaside town and Borough status in the United Kingdom, borough in East Sussex on the south coast of England,

east of Lewes and south east of London. The town gives its name to the Battle of Hastings, which took place to th ...

on 24 June 2000, aged 92. She had been in a nursing home recovering from a skin complaint when she fell and broke a hip. Atkins was admitted to the hospital where she contracted MRSA

Methicillin-resistant ''Staphylococcus aureus'' (MRSA) is a group of gram-positive bacteria that are genetically distinct from other strains of ''Staphylococcus aureus''. MRSA is responsible for several difficult-to-treat infections in humans. ...

.

Her memorial plaque, which is shared with her brother Guy, is in the northern wall at St Senara's churchyard in Zennor, Cornwall

Cornwall (; or ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is also one of the Celtic nations and the homeland of the Cornish people. The county is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, ...

where her ashes were scattered. The inscription reads "Vera May Atkins, CBE Légion d'honneur

The National Order of the Legion of Honour ( ), formerly the Imperial Order of the Legion of Honour (), is the highest and most prestigious French national order of merit, both military and Civil society, civil. Currently consisting of five cl ...

Croix de guerre". An attempt by AJEX Archivist (Association of Jewish Ex-Servicemen and Women of the UK) and author, Martin Sugarman, who interviewed Vera in Winchelsea for his chapters on Jews in SOE in his book 'Fighting Back', on 24 April 1998, to have a Star of David metal peg placed at her memorial at Zennor on a visit in 2012, was refused by the family via the vicar of the church when Sugarman visited the church and plaque. Vera also refused to allow Sugarman to tape her interview at the time and even though she understood fully why he was interviewing her as having known all the agents, and the two – Bloch and Byck, he was specifically writing about, she never revealed she was Jewish and he did not discover this till her obituary was published two years later. Leo Marks

Leopold Samuel Marks, (24 September 1920 – 15 January 2001) was an English writer, screenwriter, and cryptographer. During the Second World War he headed the codes office supporting resistance agents in occupied Europe for the secret Special ...

, the Jewish Chief of Codes at SOE, who Sugarman also interviewed the same year, 1998, also never let on that Vera was Jewish.

In popular culture

* Recorded radio interviews with Atkins, in which she relates her experiences regarding the agents she sent into France, are used in ''Into the Dark'', a short film directed by Genevieve Simms. This award-winning 16-minute documentary has been uploaded by the director toVimeo

Vimeo ( ) is an American Online video platform, video hosting, sharing, and services provider founded in 2004 and headquartered in New York City. Vimeo focuses on the delivery of high-definition video across a range of devices and operates on a ...

.

* Atkins is the subject of the "Fatal Femmes" episode of the ''Secret War'' documentary

A documentary film (often described simply as a documentary) is a nonfiction Film, motion picture intended to "document reality, primarily for instruction, education or maintaining a Recorded history, historical record". The American author and ...

series, aired in the United States on the Military Channel.

* She was played by Avice Landone

Avice Landone (1 September 191012 June 1976) was an English actress who appeared in British television and film.

She was born in Quetta, British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, pres ...

in the 1958 film ''Carve Her Name with Pride

''Carve Her Name with Pride'' is a 1958 British war Drama (film and television), drama film based on the book of the same name by R. J. Minney.

The film, directed by Lewis Gilbert, is based on the true story of Special Operations Executive agen ...

'', on which she acted as an advisor.

* The Faith Ashley character in the 1980s ITV television series '' Wish Me Luck'' is loosely based on Atkins, though there are few similarities between them beyond her role in the organisation she works for.

* Atkins was played by Stephanie Cole

Patricia Stephanie Cole (born 5 October 1941) is an English stage, television, radio and film actor, known for high-profile roles in shows such as '' Tenko'' (1981–1985), ''Open All Hours'' (1982–1985), ''A Bit of a Do'' (1989), '' Waiting ...

in the BBC Radio 4 drama "A Cold Supper Behind Harrods" by David Morley.

* She is the basis for the character of Hilda Pierce in Foyle's War.

* The 2012 play ''The Secret Reunion'' by Adrian Davis is about five SOE women holding a London reunion in 1975: Atkins, Nancy Wake, Odette Sansom Hallowes, Virginia Hall and Eileen Nearne.

* Atkins is the basis for Diana Lynd in Susan Elia MacNeal's novel ''The Paris Spy'' (2017) and for Eleanor Trigg in Pam Jenoff's novel ''The Lost Girls of Paris'' (2019).

* Atkins is the basis for Evelyn Ash in the musical ''The Invisible: Agents of Ungentlemanly Warfare'' scripted by Jonathan Christenson.

* Atkins is portrayed by Stana Katic in the 2020 movie, '' A Call to Spy''.

* Atkins' search for the truth about Noor Inayat Khan is the subject of the 2022 play ''S.O.E.'' by Deborah Clair.

* Atkins is played by Sian Altman in the 2024 six-part docudrama "Lost Women Spies", which is about the life and role in the SOE of Vera Atkins

Notes

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * . (The standard reference on the Polish part in the Enigma-decryption epic.) * * *External links

Atkins, Vera May (Oral history)

Imperial War Museums

Host Aaron Berg welcomes back historian Andrew Davidsberg for a deep dive into the life of Vera Atkins (podcast)

DIGA Studios {{DEFAULTSORT:Atkins, Vera 1908 births 2000 deaths British Special Operations Executive personnel Commanders of the Order of the British Empire Commanders of the Legion of Honour Naturalised citizens of the United Kingdom People from Bucharest People from Galați Recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1939–1945 (France) Romanian Jews Romanian people of British descent Romanian people of German descent University of Paris alumni Women's Auxiliary Air Force officers People from Winchelsea Romanian emigrants to the United Kingdom Romanian expatriates in France Romanian expatriates in Switzerland Romanian women in World War II British people of German-Jewish descent