Venezuela Boundary Commission on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Venezuelan crisis of 1895 occurred over

The Venezuelan crisis of 1895 occurred over

The Venezuela-Guyana Boundary Arbitration of 1899: An Appraisal: Part I

, ''Caribbean Studies'', Vol. 10, No. 2 (Jul., 1970), pp. 56–89 Over the course of the 19th century, Britain and Venezuela had proved no more able to reach an agreement until matters came to a head in 1895, after seven years of severed diplomatic relations. The basis of the discussions between Venezuela and the United Kingdom lay in Britain's advocacy of a particular division of the territory deriving from a mid-19th-century survey that it had commissioned. That survey originated with German naturalist

The basis of the discussions between Venezuela and the United Kingdom lay in Britain's advocacy of a particular division of the territory deriving from a mid-19th-century survey that it had commissioned. That survey originated with German naturalist

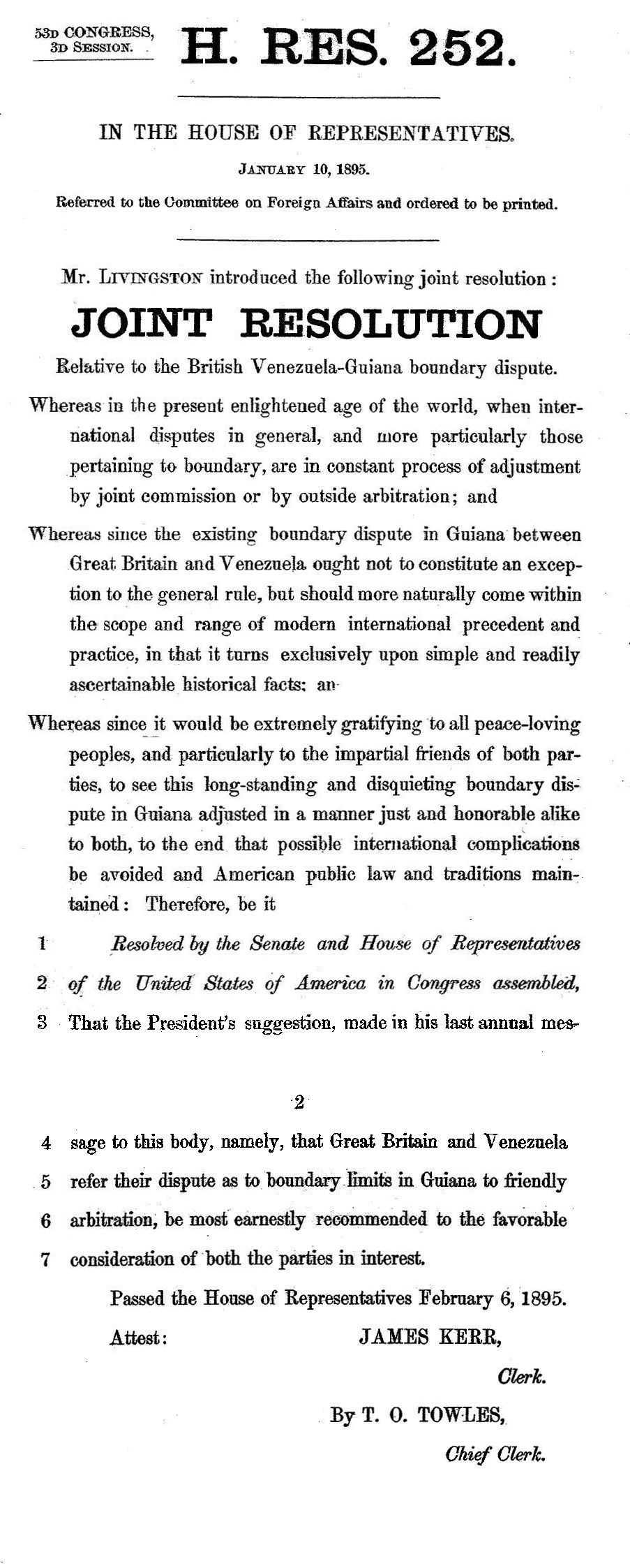

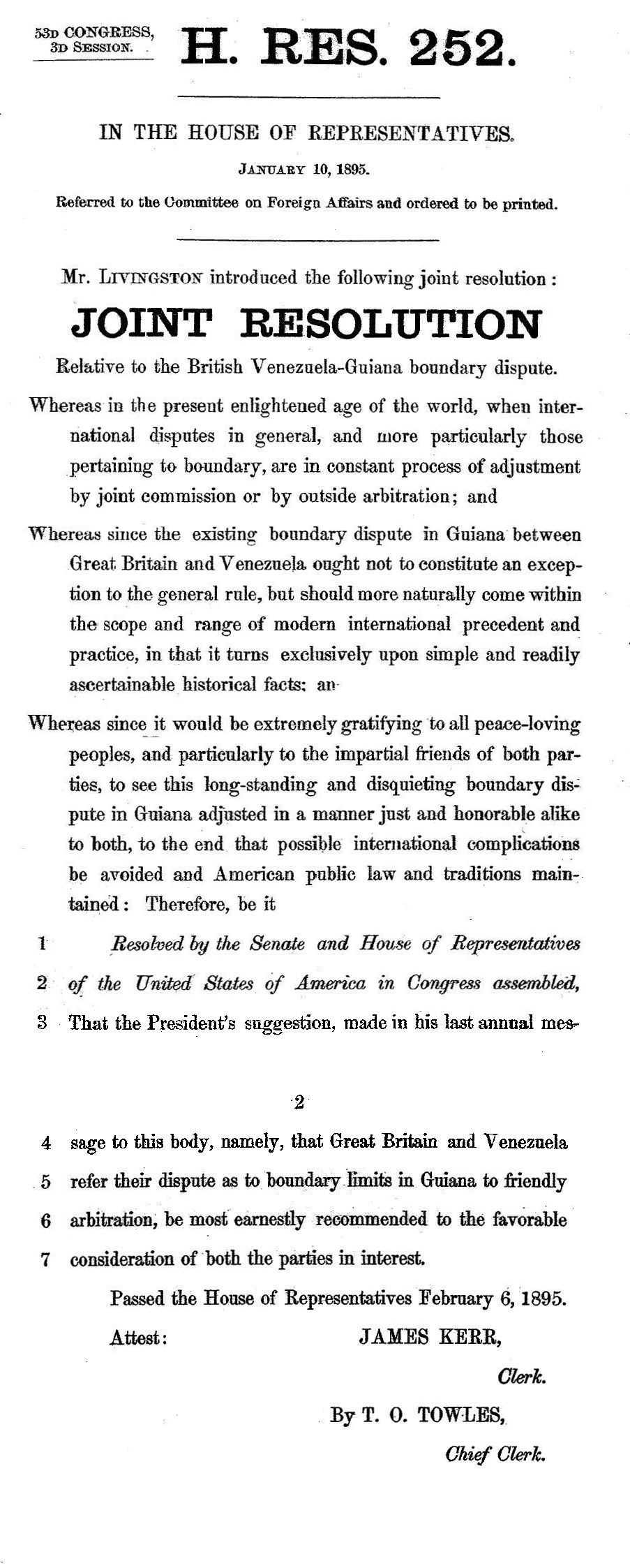

Scruggs collaborated with Georgian compatriot Representative Leonidas Livingston to propose House of Representatives Resolution 252 to the third session of the 53rd United States Congress. The bill recommended Venezuela and the

Scruggs collaborated with Georgian compatriot Representative Leonidas Livingston to propose House of Representatives Resolution 252 to the third session of the 53rd United States Congress. The bill recommended Venezuela and the

American foreign relations: A history, to 1920

'.

In January 1896, the British government decided in effect to recognise the US right to intervene in the boundary dispute and accepted arbitration in principle without insisting on the Schomburgk line as a basis for negotiation. Negotiations between the US and Britain over the details of the arbitration followed, and Britain was able to persuade the US of many of its views, even as it became clear that the eventual report of the Boundary Commission would likely be negative towards the British claims. An agreement between the US and the UK was signed on 12 November 1896. Cleveland's Boundary Commission suspended its work in November 1896, but it still went on to produce a large report.

The agreement provided for a tribunal with two members representing Venezuela (but chosen by the US Supreme Court), two members chosen by the British government, and fifth member chosen by those four, who would preside. Venezuelan President Joaquín Crespo referred to a sense of ''"national humiliation"'', and the treaty was modified so that the Venezuelan President would nominate a tribunal member. However it was understood that his choice would not be a Venezuelan, and in fact, he nominated the Chief Justice of the United States. Ultimately, on 2 February 1897, the Treaty of Washington between Venezuela and the United Kingdom was signed, and ratified several months later.

After the US and Britain had nominated their arbitrators, Britain proposed that the disputing parties agree on the presiding fifth arbitrator.King (2007:252-4) There were delays in discussing that and in the interim, Martens was among the names of international jurists suggested by the US. Martens was then chosen by Venezuela from a shortlist of names submitted by Britain. The Panel of Arbitration thus consisted of:

# Melville Weston Fuller (Chief Justice of the United States)

#

In January 1896, the British government decided in effect to recognise the US right to intervene in the boundary dispute and accepted arbitration in principle without insisting on the Schomburgk line as a basis for negotiation. Negotiations between the US and Britain over the details of the arbitration followed, and Britain was able to persuade the US of many of its views, even as it became clear that the eventual report of the Boundary Commission would likely be negative towards the British claims. An agreement between the US and the UK was signed on 12 November 1896. Cleveland's Boundary Commission suspended its work in November 1896, but it still went on to produce a large report.

The agreement provided for a tribunal with two members representing Venezuela (but chosen by the US Supreme Court), two members chosen by the British government, and fifth member chosen by those four, who would preside. Venezuelan President Joaquín Crespo referred to a sense of ''"national humiliation"'', and the treaty was modified so that the Venezuelan President would nominate a tribunal member. However it was understood that his choice would not be a Venezuelan, and in fact, he nominated the Chief Justice of the United States. Ultimately, on 2 February 1897, the Treaty of Washington between Venezuela and the United Kingdom was signed, and ratified several months later.

After the US and Britain had nominated their arbitrators, Britain proposed that the disputing parties agree on the presiding fifth arbitrator.King (2007:252-4) There were delays in discussing that and in the interim, Martens was among the names of international jurists suggested by the US. Martens was then chosen by Venezuela from a shortlist of names submitted by Britain. The Panel of Arbitration thus consisted of:

# Melville Weston Fuller (Chief Justice of the United States)

#

Melville Weston Fuller – Chief Justice of the United States 1888–1910

', Macmillan. p257 The country had been represented by James J. Storrow until his unexpected death on 15 April 1897. Britain was represented by its Attorney General, Richard Webster, assisted by Robert Reid, George Askwith and Sidney Rowlatt, with Sir Frederick Pollock preparing the original outline of Britain's argument.King (2007:258) The parties had eight months to prepare their case, another four months to reply to the other party's case, and another three months for the final printed case. The final arguments were submitted in December 1898, with the total evidence and testimony amounting to 23 volumes. Britain's key argument was that prior to Venezuela's independence, Spain had not taken effective possession of the disputed territory and said that the local Indians had had alliances with the Dutch, which gave them a sphere of influence that the British acquired in 1814. After fifty-five days of hearings, the arbitrators retired for six days. The American arbitrators found the British argument preposterous since American Indians had never been considered to have any sovereignty.King (2007:259) However, the British had the advantage that Martens wanted a unanimous decision, and the British threatened to ignore the award if it did not suit them. They were also able to argue a loss of equity since under the terms of the treaty lands occupied for 50 years would receive title, and a number of British gold mines would be narrowly lost to that cutoff if their lands were awarded to Venezuela. With the Treaty of Washington, Great Britain and Venezuela both agreed that the arbitral ruling in Paris would be a "''full, perfect, and final settlement''" (Article XIII) to the border dispute.

Press Release 2018/17

/ref>

in JSTOR

* Boyle, T. "The Venezuela Crisis and the Liberal Opposition, 1895-96." ''Journal of Modern History'' Vol. 50, No. 3, (1978): D1185-D1212

in JSTOR

* Campbell, Alexander Elmslie. ''Great Britain and the United States, 1895-1903'' (1960). * Humphreys, R. A. "Anglo-American Rivalries and the Venezuela Crisis of 1895" ''Transactions of the Royal Historical Society'' (1967) 17: 131-16

in JSTOR

* King, Willard L. ''Melville Weston Fuller – Chief Justice of the United States 1888–1910'' (Macmillan. 2007

online

ch 19 * Lodge, Henry Cabot. "England, Venezuela, and the Monroe doctrine." ''The North American Review'' 160.463 (1895): 651–658

online

* Mathews, Joseph J. "Informal Diplomacy in the Venezuelan Crisis of 1896." ''The Mississippi Valley Historical Review'' 50.2 (1963): 195–212

in JSTOR

Fallacies of the British Blue Book on the Venezuela Question

(Pamphlet, 1896) {{DEFAULTSORT:Venezuelan crisis of 1895 1895 in Venezuela 1895 in the United States 1895 in the United Kingdom 1890s in British Guiana 1895 in international relations Guyana–Venezuela territorial dispute

The Venezuelan crisis of 1895 occurred over

The Venezuelan crisis of 1895 occurred over Venezuela

Venezuela, officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many Federal Dependencies of Venezuela, islands and islets in the Caribbean Sea. It com ...

's longstanding dispute with Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

about the territory of Essequibo, which Britain believed was part of British Guiana

British Guiana was a British colony, part of the mainland British West Indies. It was located on the northern coast of South America. Since 1966 it has been known as the independent nation of Guyana.

The first known Europeans to encounter Guia ...

and Venezuela recognized as its own Guayana Esequiba. The issue became more acute with the development of gold mining in the region.

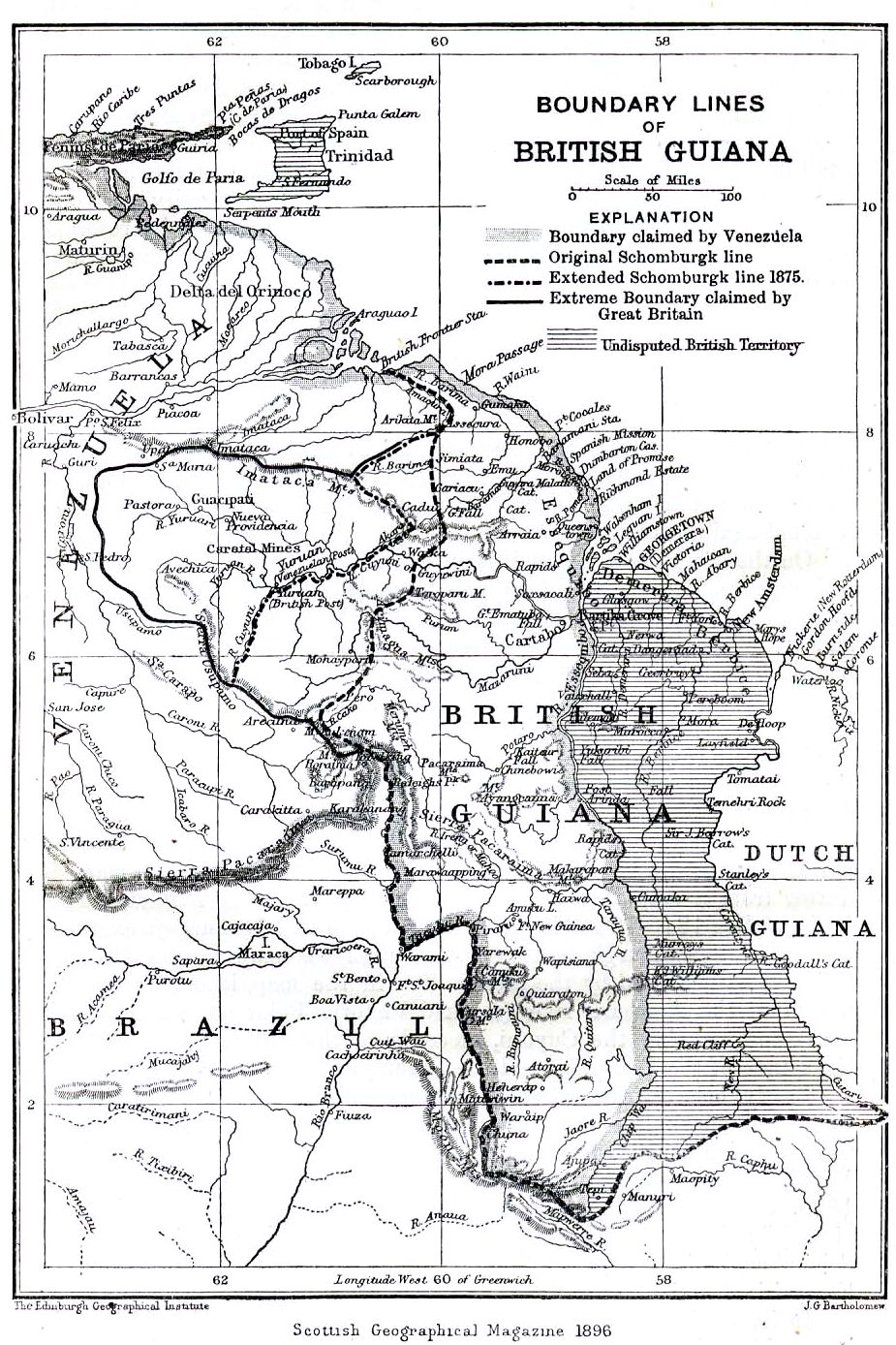

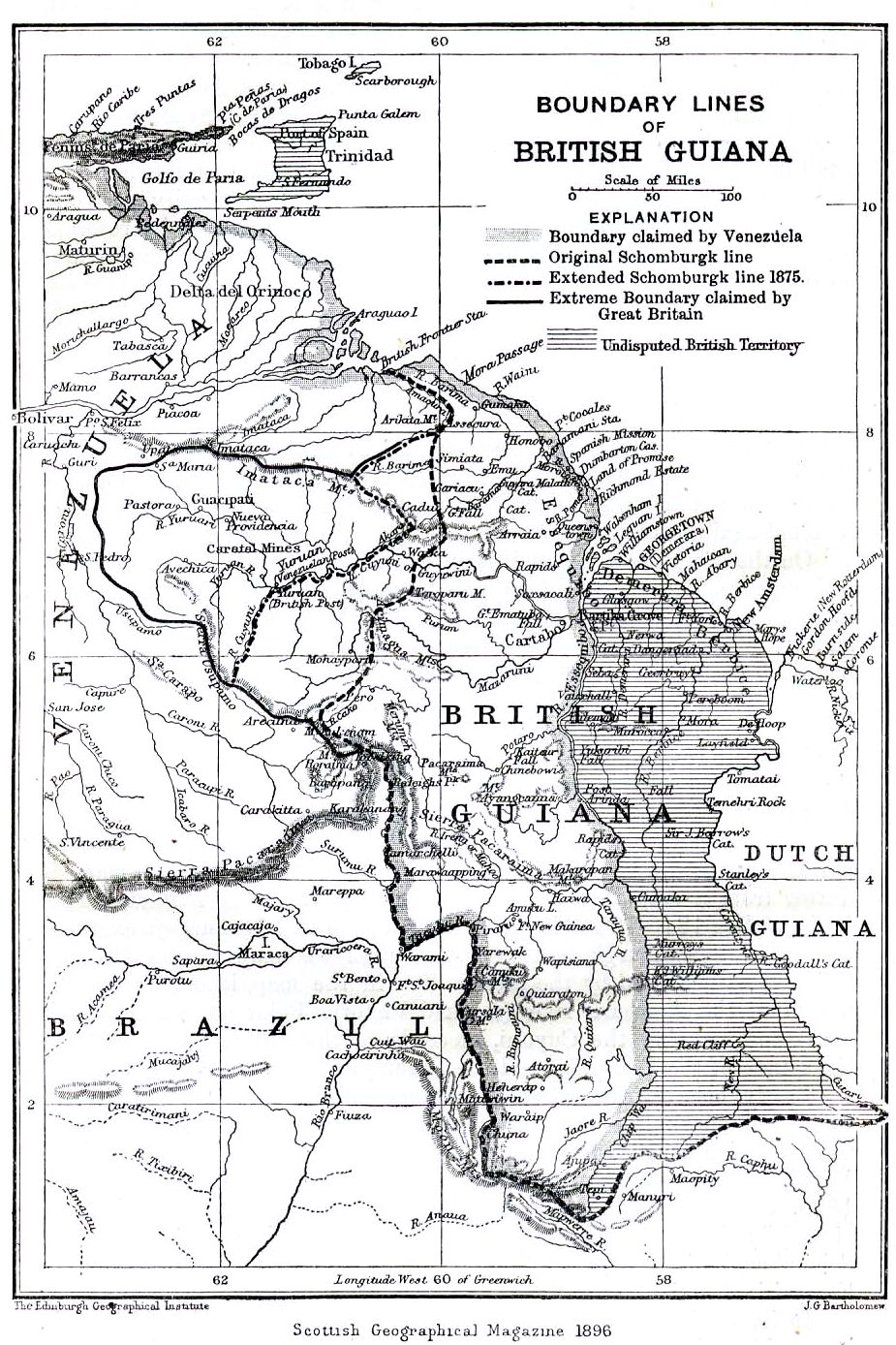

As the dispute became a crisis, the key issue became Britain's refusal to include in the proposed international arbitration the territory east of the "Schomburgk Line

The Schomburgk Line is the name given to a surveying, survey line that figured in a 19th-century territorial dispute between Venezuela and British Guiana. The line was named after German-born English explorer and naturalist Robert Hermann Schombu ...

", which a surveyor had drawn half-a-century earlier as a boundary between Venezuela and the former Dutch territory ceded by the Dutch in the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814, later part of British Guiana

British Guiana was a British colony, part of the mainland British West Indies. It was located on the northern coast of South America. Since 1966 it has been known as the independent nation of Guyana.

The first known Europeans to encounter Guia ...

.King (2007:249) The crisis ultimately saw Britain accept the United States' intervention in the dispute to force arbitration of the entire disputed territory, and tacitly accept the US right to intervene under the Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine is a foreign policy of the United States, United States foreign policy position that opposes European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It holds that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign ...

. A tribunal convened in Paris in 1898 to decide the matter, and in 1899 awarded the bulk of the disputed territory to British Guiana.

The dispute had become a diplomatic crisis in 1895 when a lobbyist for Venezuela William Lindsay Scruggs

William Lindsay Scruggs (September 14, 1836 – July 18, 1912) was an American author, lawyer, and diplomat. He was a scholar of South American foreign policy and U.S. ambassador to Colombia and Venezuela. He played a key role in the Venezuel ...

sought to argue that British behaviour over the issue violated the 1823 Monroe Doctrine and used his influence in Washington, DC

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and Federal district of the United States, federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from ...

, to pursue the matter. US President Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was the 22nd and 24th president of the United States, serving from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. He was the first U.S. president to serve nonconsecutive terms and the first Hist ...

adopted a broad interpretation of the Doctrine that forbade new European colonies but also declared an American interest in any matter in the hemisphere. Zakaria, Fareed, ''From Wealth to Power'' (1999). Princeton University Press. . pp145–146 British Prime Minister Lord Salisbury

Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (; 3 February 183022 August 1903), known as Lord Salisbury, was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United ...

and the British ambassador to Washington, Julian Pauncefote, misjudged the importance the American government placed on the dispute, prolonging the crisis before ultimately accepting the American demand for arbitration of the entire territory.

By standing with a Latin American nation against European colonial powers, Cleveland improved relations with the United States' southern neighbors, but the cordial manner in which the negotiations were conducted also made for good relations with Britain. However, by backing down in the face of a strong US declaration of a strong interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine, Britain tacitly accepted it, and the crisis thus provided a basis for the expansion of US interventionism in the Americas

The Americas, sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America and South America.''Webster's New World College Dictionary'', 2010 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Cleveland, Ohio. When viewed as a sing ...

. Leading British historian Robert Arthur Humphreys later called the crisis "one of the most momentous episodes in the history of Anglo-American relations in general and of Anglo-American rivalries in Latin America in particular."

Background

By 1895, the dispute between Britain and Venezuela over the territory ofGuayana Esequiba

Guyana is a country in the Guianas, South America.

Guyana, Guiana, or Guayana may refer to:

* British Guiana, a British colony until 1966, now independent and known as Guyana

* French Guiana, an overseas department of France in the Guianas

* The ...

, which Britain claimed as part of British Guiana

British Guiana was a British colony, part of the mainland British West Indies. It was located on the northern coast of South America. Since 1966 it has been known as the independent nation of Guyana.

The first known Europeans to encounter Guia ...

and Venezuela saw as Venezuelan territory, had lasted for half a century. The territorial claims, originally those of the Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire, sometimes referred to as the Hispanic Monarchy (political entity), Hispanic Monarchy or the Catholic Monarchy, was a colonial empire that existed between 1492 and 1976. In conjunction with the Portuguese Empire, it ushered ...

, inherited by Venezuela after its independence in 1811, and of the Dutch Empire

The Dutch colonial empire () comprised overseas territories and trading posts under some form of Dutch control from the early 17th to late 20th centuries, including those initially administered by Dutch chartered companies—primarily the Du ...

, inherited by the United Kingdom with the acquisition of the Dutch territories of Essequibo, Demerara

Demerara (; , ) is a historical region in the Guianas, on the north coast of South America, now part of the country of Guyana. It was a colony of the Dutch West India Company between 1745 and 1792 and a colony of the Dutch state from 1792 unti ...

and Berbice

Berbice () is a region along the Berbice River in Guyana, which was between 1627 and 1792 a colony of the Dutch West India Company and between 1792 and 1815 a colony of the Dutch state. After having been ceded to the United Kingdom of Great Brita ...

in 1814, had remained unsettled over previous centuries.Joseph, Cedric L. (1970),The Venezuela-Guyana Boundary Arbitration of 1899: An Appraisal: Part I

, ''Caribbean Studies'', Vol. 10, No. 2 (Jul., 1970), pp. 56–89 Over the course of the 19th century, Britain and Venezuela had proved no more able to reach an agreement until matters came to a head in 1895, after seven years of severed diplomatic relations.

The basis of the discussions between Venezuela and the United Kingdom lay in Britain's advocacy of a particular division of the territory deriving from a mid-19th-century survey that it had commissioned. That survey originated with German naturalist

The basis of the discussions between Venezuela and the United Kingdom lay in Britain's advocacy of a particular division of the territory deriving from a mid-19th-century survey that it had commissioned. That survey originated with German naturalist Robert Schomburgk

Sir Robert Hermann Schomburgk (5 June 1804 – 11 March 1865) was a Holy Roman Empire-born explorer for Great Britain who carried out geographical, ethnological and botanical studies in South America and the West Indies, and also fulfilled diplo ...

's four-year expedition for the Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), often shortened to RGS, is a learned society and professional body for geography based in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical scien ...

in 1835 to 1839, which resulted in a sketch of the territory with a line marking what he believed to be the western boundary claimed by the Dutch. He was thus commissioned by the British government to carry out a survey of Guiana's boundaries. R. A. Humphreys (1967), "Anglo-American Rivalries and the Venezuela Crisis of 1895", Presidential Address to the Royal Historical Society

The Royal Historical Society (RHS), founded in 1868, is a learned society of the United Kingdom which advances scholarly studies of history.

Origins

The society was founded and received its royal charter in 1868. Until 1872 it was known as the H ...

10 December 1966, ''Transactions of the Royal Historical Society'', 17: pp131-164 The result was the "Schomburgk Line

The Schomburgk Line is the name given to a surveying, survey line that figured in a 19th-century territorial dispute between Venezuela and British Guiana. The line was named after German-born English explorer and naturalist Robert Hermann Schombu ...

", which he established partly to follow natural divisions and partly to distinguish territory of Spanish or Venezuelan occupation from that which had been occupied by the Dutch. The line went well beyond the area of British occupation and gave British Guiana control of the mouth of the Orinoco

The Orinoco () is one of the longest rivers in South America at . Its drainage basin, sometimes known as the Orinoquia, covers approximately 1 million km2, with 65% of it in Venezuela and 35% in Colombia. It is the List of rivers by discharge, f ...

River.

In 1844, Venezuela declared the Essequibo River the dividing line; a British offer the same year to make major alterations to the line and cede the mouth of the Orinoco and much associated territory was ignored. No treaty between Britain and Venezuela was reached until 1850 agreement not to encroach on disputed territory.

On 5 May 1859, Venezuela and Brazil signed a treaty to delimit their borders. It was agreed that the Orinoco and Essequibo river basins would be recognized as Venezuela's, while the Amazon river basin would be recognized as Brazil's.

The dispute went unmentioned for many years until gold was discovered in the region, which disrupted relations between the United Kingdom and Venezuela. In 1876, gold mines inhabited mainly by English-speaking people had been established in the Cuyuni basin, which was Venezuelan territory beyond the Schomburgk line but within the area Schomburgk thought Britain could claim. That year, Venezuela reiterated its claim up to the Essequibo River, to which the British responded with a counterclaim including the entire Cuyuni basin, although this was a paper claim the British never intended to pursue.

In 1886, Schomburgk's initial sketch, which had been published in 1840, was the only version of the "Schomburgk Line" published in British maps. That led to accusations by US President Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was the 22nd and 24th president of the United States, serving from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. He was the first U.S. president to serve nonconsecutive terms and the first Hist ...

that the line had been extended ''"in some mysterious way"''.

In October 1886, Britain declared the line to be the provisional frontier of British Guiana, and in February 1887 Venezuela severed diplomatic relations. Proposals for a renewal of relations and settlement of the dispute failed repeatedly. By summer 1894, diplomatic relations had been severed for seven years, the dispute having dragged on for half a century. In addition, both sides had established police or military stations at key points in the area, partly to defend claims to the ''Caratal'' goldfield of the region's Yuruari basin, which was within Venezuelan territory but claimed by the British. The mine at El Callao, started in 1871, was once one of the richest in the world, and the goldfields as a whole saw over a million ounces exported between 1860 and 1883. The gold mining was dominated by immigrants from the British Isles and the British West Indies, giving an appearance of almost creating a British colony on Venezuelan territory.Humphreys (1967:139)

Venezuela had in the course of the dispute repeatedly appealed to the US and to the Monroe Doctrine, but the US government had declined to involve itself. That changed after Venezuela obtained the services of William Lindsay Scruggs

William Lindsay Scruggs (September 14, 1836 – July 18, 1912) was an American author, lawyer, and diplomat. He was a scholar of South American foreign policy and U.S. ambassador to Colombia and Venezuela. He played a key role in the Venezuel ...

. Scruggs, a former US ambassador to Colombia and Venezuela, was recruited in 1893 by the Venezuelan government to operate on its behalf in Washington D.C. as a lobbyist

Lobbying is a form of advocacy, which lawfully attempts to directly influence legislators or government officials, such as regulatory agencies or judiciary. Lobbying involves direct, face-to-face contact and is carried out by various entities, in ...

and legal attache. Scruggs had apparently resigned his ambassadorship to Venezuela in December 1892 but had been dismissed by the US for bribing the President of Venezuela. As a lobbyist, Scruggs published an October 1894 pamphlet, ''British Aggressions in Venezuela:, or the Monroe Doctrine on Trial'' in which he attacked "British aggression" and claimed that Venezuela was anxious to arbitrate over the Venezuela-British Guiana

British Guiana was a British colony, part of the mainland British West Indies. It was located on the northern coast of South America. Since 1966 it has been known as the independent nation of Guyana.

The first known Europeans to encounter Guia ...

border dispute. Scruggs also claimed that British policies in the disputed territory violated the Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine is a foreign policy of the United States, United States foreign policy position that opposes European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It holds that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign ...

of 1823. For much of the 19th century, it had only rarely been invoked by the United States, but a "paradigm shift in U.S. foreign relations in the late nineteenth century" saw Americans more actively support their increasingly-significant economic interests in Central and South America. The "'new diplomacy' thrust the United States more emphatically into the imperial struggle".Gilderhus, Mark T. (2006), "The Monroe Doctrine: Meanings and Implications", ''Presidential Studies Quarterly'', Volume 36, Issue 1, pages 5–16 It was in that context that Scruggs sought to draw on the Doctrine in Venezuela's interests.

Crisis

Scruggs collaborated with Georgian compatriot Representative Leonidas Livingston to propose House of Representatives Resolution 252 to the third session of the 53rd United States Congress. The bill recommended Venezuela and the

Scruggs collaborated with Georgian compatriot Representative Leonidas Livingston to propose House of Representatives Resolution 252 to the third session of the 53rd United States Congress. The bill recommended Venezuela and the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

settle the dispute by arbitration. President Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was the 22nd and 24th president of the United States, serving from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. He was the first U.S. president to serve nonconsecutive terms and the first Hist ...

signed it on 22 February 1895, after passing both houses of the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature, legislative branch of the federal government of the United States. It is a Bicameralism, bicameral legislature, including a Lower house, lower body, the United States House of Representatives, ...

. The vote had been unanimous.

On 27 April 1895, the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

occupied the Nicaraguan port of Corinto, after a number of British subjects, including the vice-consul, had been seized during disturbances, shortly after the former protectorate of the Mosquito Coast

The Mosquito Coast, also known as Mosquitia, is a historical and Cultural area, geo-cultural region along the western shore of the Caribbean Sea in Central America, traditionally described as extending from Cabo Camarón, Cape Camarón to the C ...

had been incorporated into Nicaragua. The British demanded an indemnity of £15,000. US Secretary of State Walter Q. Gresham thought the demands harsh, but also that they should be met. US public opinion, however, was outraged at the British military activity in the US sphere of influence.

In July 1895, new Secretary of State Richard Olney

Richard Olney (September 15, 1835 – April 8, 1917) was an American attorney, statesman, and Democratic Party politician who served as a member of the second cabinet of President Grover Cleveland as the 40th United States Attorney General ...

(succeeding Gresham, who died in office at the end of May) sent a document to London which became known as "Olney's twenty-inch gun" (the draft was 12,000 words long).Thomas Paterson, J. Garry Clifford, Shane J. Maddock (2009), American foreign relations: A history, to 1920

'.

Cengage Learning

Cengage Group is an American educational content, technology, and services company for higher education, K–12, professional, and library markets. It operates in more than 20 countries around the world.(June 27, 2014Global Publishing Leaders 2 ...

. p. 205 The note reviewed the history of the Anglo-Venezuelan dispute and of the Monroe Doctrine, and it firmly insisted on the application of the Doctrine to the case, declaring that "today the United States is practically sovereign on this continent, and its fiat is law upon the subjects to which it confines its interposition." The President, the Secretary of State, and the US public "had been brought to believe that Britain was in the wrong, that the vital interests of the United States were involved, and the United States must intervene." The note had little impact on the British government, partly because Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal Party (UK), Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist after opposing home rule for Ireland, and eventually was a leading New Imperialism, imperial ...

, at the Colonial Office

The Colonial Office was a government department of the Kingdom of Great Britain and later of the United Kingdom, first created in 1768 from the Southern Department to deal with colonial affairs in North America (particularly the Thirteen Colo ...

, thought it possible that the colony had a major gold-bearing region around the Schomburgk line and partly because the British rejected the idea that the Monroe Doctrine had any relevance for the boundary dispute. A reply to Olney's note directly challenged his interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine:

The Government of the United States is not entitled to affirm as a universal proposition, with reference to a number of independent States for whose conduct it assumes no responsibility, that its interests are necessarily concerned in whatever may befall those States, simply because they are situated in the Western Hemisphere."By 17 December 1895, Cleveland delivered an address to the United States Congress reaffirming the Monroe Doctrine and its relevance to the dispute. The address asked Congress to fund a commission to study the boundaries between Venezuela and British Guiana, and declared it the duty of the United States "to resist by every means in its power as a willful aggression upon its rights and interests" any British attempt to exercise jurisdiction over territory the United States judged Venezuelan. The address was perceived as direct threat of war with the United Kingdom if the British did not comply, but Cleveland had not committed himself to accepting the commission's report or specified any details on how the commission would act. Despite the public belligerence, neither the British nor the American governments had any interest in war. On 18 December 1895, Congress approved $100,000 for the United States Commission on the Boundary Between Venezuela and British Guiana. It was formally established on 1 January 1896. Historian George Lincoln Burr, who contributed to the commission's historical research, argued shortly after the Commission concluded its work that it made a major contribution to clarifying issues of historical fact in the dispute. The commission's work, he wrote, helped the disputing parties to focus on issues of fact supportable by evidence (as opposed to mere assertions), and by the time the Arbitration process was under way, the commission's own view of historical facts was largely accepted by the parties "so that their main issue asnow in the main one of law, not of fact."

Arbitration

In January 1896, the British government decided in effect to recognise the US right to intervene in the boundary dispute and accepted arbitration in principle without insisting on the Schomburgk line as a basis for negotiation. Negotiations between the US and Britain over the details of the arbitration followed, and Britain was able to persuade the US of many of its views, even as it became clear that the eventual report of the Boundary Commission would likely be negative towards the British claims. An agreement between the US and the UK was signed on 12 November 1896. Cleveland's Boundary Commission suspended its work in November 1896, but it still went on to produce a large report.

The agreement provided for a tribunal with two members representing Venezuela (but chosen by the US Supreme Court), two members chosen by the British government, and fifth member chosen by those four, who would preside. Venezuelan President Joaquín Crespo referred to a sense of ''"national humiliation"'', and the treaty was modified so that the Venezuelan President would nominate a tribunal member. However it was understood that his choice would not be a Venezuelan, and in fact, he nominated the Chief Justice of the United States. Ultimately, on 2 February 1897, the Treaty of Washington between Venezuela and the United Kingdom was signed, and ratified several months later.

After the US and Britain had nominated their arbitrators, Britain proposed that the disputing parties agree on the presiding fifth arbitrator.King (2007:252-4) There were delays in discussing that and in the interim, Martens was among the names of international jurists suggested by the US. Martens was then chosen by Venezuela from a shortlist of names submitted by Britain. The Panel of Arbitration thus consisted of:

# Melville Weston Fuller (Chief Justice of the United States)

#

In January 1896, the British government decided in effect to recognise the US right to intervene in the boundary dispute and accepted arbitration in principle without insisting on the Schomburgk line as a basis for negotiation. Negotiations between the US and Britain over the details of the arbitration followed, and Britain was able to persuade the US of many of its views, even as it became clear that the eventual report of the Boundary Commission would likely be negative towards the British claims. An agreement between the US and the UK was signed on 12 November 1896. Cleveland's Boundary Commission suspended its work in November 1896, but it still went on to produce a large report.

The agreement provided for a tribunal with two members representing Venezuela (but chosen by the US Supreme Court), two members chosen by the British government, and fifth member chosen by those four, who would preside. Venezuelan President Joaquín Crespo referred to a sense of ''"national humiliation"'', and the treaty was modified so that the Venezuelan President would nominate a tribunal member. However it was understood that his choice would not be a Venezuelan, and in fact, he nominated the Chief Justice of the United States. Ultimately, on 2 February 1897, the Treaty of Washington between Venezuela and the United Kingdom was signed, and ratified several months later.

After the US and Britain had nominated their arbitrators, Britain proposed that the disputing parties agree on the presiding fifth arbitrator.King (2007:252-4) There were delays in discussing that and in the interim, Martens was among the names of international jurists suggested by the US. Martens was then chosen by Venezuela from a shortlist of names submitted by Britain. The Panel of Arbitration thus consisted of:

# Melville Weston Fuller (Chief Justice of the United States)

# David Josiah Brewer

David Josiah Brewer (June 20, 1837 – March 28, 1910) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1890 to 1910. An appointee of President Benjamin Harrison, he supported states' righ ...

(Member of the US Supreme Court)

# Sir Richard Henn Collins (Lord Justice of Appeal

A Lord Justice of Appeal or Lady Justice of Appeal is a judge of the Court of Appeal of England and Wales, the court that hears appeals from the High Court of Justice, the Crown Court and other courts and tribunals. A Lord (or Lady) Just ...

)

# Lord Herschell (former Lord Chancellor

The Lord Chancellor, formally titled Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom. The lord chancellor is the minister of justice for England and Wales and the highest-ra ...

), replaced upon his death by Charles Russell (Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales

The Lord or Lady Chief Justice of England and Wales is the head of the judiciary of England and Wales and the president of the courts of England and Wales.

Until 2005 the lord chief justice was the second-most senior judge of the English and ...

)

# Friedrich Martens (diplomat of Russia and jurist)

Venezuela's senior counsel was former US President Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison (August 20, 1833March 13, 1901) was the 23rd president of the United States, serving from 1889 to 1893. He was a member of the Harrison family of Virginia—a grandson of the ninth president, William Henry Harrison, and a ...

, assisted by Severo Mallet-Prevost, Benjamin F. Tracy, James R. Soley, and José María Rojas.Willard L. King (2007), Melville Weston Fuller – Chief Justice of the United States 1888–1910

', Macmillan. p257 The country had been represented by James J. Storrow until his unexpected death on 15 April 1897. Britain was represented by its Attorney General, Richard Webster, assisted by Robert Reid, George Askwith and Sidney Rowlatt, with Sir Frederick Pollock preparing the original outline of Britain's argument.King (2007:258) The parties had eight months to prepare their case, another four months to reply to the other party's case, and another three months for the final printed case. The final arguments were submitted in December 1898, with the total evidence and testimony amounting to 23 volumes. Britain's key argument was that prior to Venezuela's independence, Spain had not taken effective possession of the disputed territory and said that the local Indians had had alliances with the Dutch, which gave them a sphere of influence that the British acquired in 1814. After fifty-five days of hearings, the arbitrators retired for six days. The American arbitrators found the British argument preposterous since American Indians had never been considered to have any sovereignty.King (2007:259) However, the British had the advantage that Martens wanted a unanimous decision, and the British threatened to ignore the award if it did not suit them. They were also able to argue a loss of equity since under the terms of the treaty lands occupied for 50 years would receive title, and a number of British gold mines would be narrowly lost to that cutoff if their lands were awarded to Venezuela. With the Treaty of Washington, Great Britain and Venezuela both agreed that the arbitral ruling in Paris would be a "''full, perfect, and final settlement''" (Article XIII) to the border dispute.

Outcome

Sitting inParis

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

, the Tribunal of Arbitration finalized its decision on 3 October 1899. The award was unanimous but gave no reasons for the decision, merely describing the resulting boundary, which gave Britain almost 90% of the disputed territory.Schoenrich (1949:526) The Schomburgk Line

The Schomburgk Line is the name given to a surveying, survey line that figured in a 19th-century territorial dispute between Venezuela and British Guiana. The line was named after German-born English explorer and naturalist Robert Hermann Schombu ...

was, with small deviations, re-established as the border between British Guiana

British Guiana was a British colony, part of the mainland British West Indies. It was located on the northern coast of South America. Since 1966 it has been known as the independent nation of Guyana.

The first known Europeans to encounter Guia ...

and Venezuela. The first deviation from the Schomburgk line was that Venezuela's territory included Barima Point

Barima Point (), is a small settlement in the Antonio Díaz municipality of Delta Amacuro state in Venezuela, at the mouth of the Barima River.

It has a lighthouse, Faro Barima, and a Coast Guard Station.

The city was controlled by British Guian ...

at the mouth of the Orinoco, giving it undisputed control of the river and thus the ability to levy duties on Venezuelan commerce. The second was drawing the border at the Wenamu River

Wenamu River (Venamo River) is a river in South America. It forms a portion of the international boundary between Venezuela and Guyana. It is part of the Essequibo River basin.

Mango Landing is a small settlement on the Guyana side of the Wanamu ...

rather than the Cuyuni River, giving Venezuela a substantial territory east of the line that Britain had originally refused to include in the arbitration. However, Britain received most of the disputed territory and all of the gold mines.

The reaction to the award was surprise, the award's lack of reasoning being a particular concern. Though the Venezuelans were keenly disappointed with the outcome, they honoured their counsel for their efforts (their delegation's Secretary, Severo Mallet-Prevost, received the Order of the Liberator in 1944), and abided by the award.

The Anglo-Venezuelan boundary dispute asserted for the first time a more outward-looking American foreign policy, particularly in the Americas

The Americas, sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America and South America.''Webster's New World College Dictionary'', 2010 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Cleveland, Ohio. When viewed as a sing ...

, marking the United States as a world power. That was the earliest example of modern interventionism under the Monroe Doctrine in which the USA exercised its claimed prerogatives in the Americas

The Americas, sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America and South America.''Webster's New World College Dictionary'', 2010 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Cleveland, Ohio. When viewed as a sing ...

.

Aftermath

The Olney–Pauncefote Treaty of 1897 was a proposed treaty between the United States and Britain in 1897 that would have required arbitration of major disputes. The treaty was rejected by the US Senate and never went into effect. The 1895 dispute between the US and Britain over Venezuela was peacefully resolved through arbitration. Both nations realized that a mechanism was desirable to avoid possible future conflicts. US Secretary of StateRichard Olney

Richard Olney (September 15, 1835 – April 8, 1917) was an American attorney, statesman, and Democratic Party politician who served as a member of the second cabinet of President Grover Cleveland as the 40th United States Attorney General ...

in January 1897 negotiated an arbitration treaty with the British diplomat Julian Pauncefote. President William McKinley supported the treaty, as did most opinion leaders, academics, and leading newspapers. In Britain, it was promoted by pacifist Liberal MP for Haggerston

Haggerston is an area in London, England and is located in the London Borough of Hackney. It is in East London and part of the East End of London, East End. There is an Haggerston (ward), electoral ward called Haggerston within the borough.

H ...

Randal Cremer

Sir William Randal Cremer (18 March 1828 – 22 July 1908) usually known by his middle name "Randal", was a British Liberal Member of Parliament, a pacifist, and a leading advocate for international arbitration. He was awarded the Nobel Peace ...

; while main opposition came from Irish-Americans, who held a very negative view of Britain because of its treatment of Ireland.

In the US Senate, however, a series of amendments exempted important issues from any sort of arbitration. Any issue that was not exempted would need two thirds of the Senate before arbitration could begin. Virtually nothing was left of the original proposal, and the Senate in May 1897 voted 43 in favor to 26 opposed, three votes short of what was needed. The Senate was jealous of its control over treaties and was susceptible to a certain deep-rooted Anglophobia.

Despite its disappointment with the award of Paris Tribunal of Arbitration, Venezuela abided by it. However, half a century later, the publication of an alleged political deal between Russia and Britain led Venezuela to reassert its claims. In 1949, the US jurist Otto Schoenrich gave the Venezuelan government the Memorandum of Severo Mallet-Prevost (Official Secretary of the U.S./Venezuela delegation in the Tribunal of Arbitration), written in 1944 to be published only after Mallet-Prevost's death. That reopened the issues, with Mallet-Prevost surmising a political deal between Russia and Britain from the subsequent private behaviour of the judges.Otto Schoenrich, "The Venezuela-British Guiana Boundary Dispute", July 1949, ''American Journal of International Law''. Vol. 43, No. 3. p. 523. Washington, DC. (USA). Mallet-Prevost said that Martens had visited England with the two British arbitrators in the summer of 1899 and had offered the two American judges a choice between accepting a unanimous award along the lines ultimately agreed or a 3-2 majority opinion even more favourable to the British. The alternative would have followed the Schomburgk Line entirely and given the mouth of the Orinoco to the British. Mallet-Prevost said that the American judges and Venezuelan counsel were disgusted at the situation and considered the 3-2 option with a strongly-worded minority opinion but ultimately went along with Martens to avoid depriving Venezuela of valuable territory to which it was entitled.

As a result of Mallet-Prevost's claims, Venezuela revived its claim to the disputed territory in 1962. In 2018, Guyana has applied to the International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; , CIJ), or colloquially the World Court, is the only international court that Adjudication, adjudicates general disputes between nations, and gives advisory opinions on International law, internation ...

to get a declaration that the 1899 Award is valid and binding upon Guyana and Venezuela and that the boundary established by that Award and the 1905 Agreement is valid./ref>

See also

* ''The Monroe Doctrine'' (1896 film) – US propaganda filmNotes

References

Further reading

* Blake, Nelson M. "Background of Cleveland's Venezuelan Policy." ''American Historical Review'' 47.2 (1942): 259–277in JSTOR

* Boyle, T. "The Venezuela Crisis and the Liberal Opposition, 1895-96." ''Journal of Modern History'' Vol. 50, No. 3, (1978): D1185-D1212

in JSTOR

* Campbell, Alexander Elmslie. ''Great Britain and the United States, 1895-1903'' (1960). * Humphreys, R. A. "Anglo-American Rivalries and the Venezuela Crisis of 1895" ''Transactions of the Royal Historical Society'' (1967) 17: 131-16

in JSTOR

* King, Willard L. ''Melville Weston Fuller – Chief Justice of the United States 1888–1910'' (Macmillan. 2007

online

ch 19 * Lodge, Henry Cabot. "England, Venezuela, and the Monroe doctrine." ''The North American Review'' 160.463 (1895): 651–658

online

* Mathews, Joseph J. "Informal Diplomacy in the Venezuelan Crisis of 1896." ''The Mississippi Valley Historical Review'' 50.2 (1963): 195–212

in JSTOR

Fallacies of the British Blue Book on the Venezuela Question

(Pamphlet, 1896) {{DEFAULTSORT:Venezuelan crisis of 1895 1895 in Venezuela 1895 in the United States 1895 in the United Kingdom 1890s in British Guiana 1895 in international relations Guyana–Venezuela territorial dispute

1895

Events January

* January 5 – Dreyfus affair: French officer Alfred Dreyfus is stripped of his army rank and sentenced to life imprisonment on Devil's Island (off French Guiana) on what is much later admitted to be a false charge of tr ...

1895

Events January

* January 5 – Dreyfus affair: French officer Alfred Dreyfus is stripped of his army rank and sentenced to life imprisonment on Devil's Island (off French Guiana) on what is much later admitted to be a false charge of tr ...

1895

Events January

* January 5 – Dreyfus affair: French officer Alfred Dreyfus is stripped of his army rank and sentenced to life imprisonment on Devil's Island (off French Guiana) on what is much later admitted to be a false charge of tr ...

History of United Kingdom–United States relations

1895

Events January

* January 5 – Dreyfus affair: French officer Alfred Dreyfus is stripped of his army rank and sentenced to life imprisonment on Devil's Island (off French Guiana) on what is much later admitted to be a false charge of tr ...

Presidencies of Grover Cleveland

Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury

Diplomatic crises of the 19th century