Utopia Project on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imagined

Ecological utopian society describes new ways in which society should relate to nature. '' Ecotopia: The Notebooks and Reports of William Weston'' from 1975 by Ernest Callenbach was one of the first influential ecological utopian novels.Archived a

Ecological utopian society describes new ways in which society should relate to nature. '' Ecotopia: The Notebooks and Reports of William Weston'' from 1975 by Ernest Callenbach was one of the first influential ecological utopian novels.Archived a

Ghostarchive

and th

Wayback Machine

Richard Grove's book '' Green Imperialism: Colonial Expansion, Tropical Island Edens and the Origins of Environmentalism 1600–1860'' from 1995 suggested the roots of ecological utopian thinking. Grove's book sees early environmentalism as a result of the impact of utopian tropical islands on European data-driven scientists. The works on ecological eutopia perceive a widening gap between the modern Western way of living that destroys nature and a more traditional way of living before industrialization. Ecological utopias may advocate a society that is more sustainable. According to the Dutch philosopher Marius de Geus, ecological utopias could be inspirational sources for movements involving

Living in the Future: Utopianism and the Long Civil Rights Movement

(2022) by Victoria Wolcott * ''Utopia: Music album'' (2023), by Travis Scott. * ''Utopia: The History of an Idea'' (2020), by Gregory Claeys. London: Thames & Hudson. *''Two Kinds of Utopia'', (1912) by

community

A community is a social unit (a group of people) with a shared socially-significant characteristic, such as place, set of norms, culture, religion, values, customs, or identity. Communities may share a sense of place situated in a given g ...

or society

A society () is a group of individuals involved in persistent social interaction or a large social group sharing the same spatial or social territory, typically subject to the same political authority and dominant cultural expectations. ...

that possesses highly desirable or near-perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book ''Utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imagined community or society that possesses highly desirable or near-perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book ''Utopia (book), Utopia'', which describes a fictiona ...

'', which describes a fictional island society in the New World

The term "New World" is used to describe the majority of lands of Earth's Western Hemisphere, particularly the Americas, and sometimes Oceania."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: ...

.

Hypothetical utopias focus on, among other things, equality in categories such as economics

Economics () is a behavioral science that studies the Production (economics), production, distribution (economics), distribution, and Consumption (economics), consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interac ...

, government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive (government), execu ...

and justice

In its broadest sense, justice is the idea that individuals should be treated fairly. According to the ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'', the most plausible candidate for a core definition comes from the ''Institutes (Justinian), Inst ...

, with the method and structure of proposed implementation varying according to ideology. Lyman Tower Sargent argues that the nature of a utopia is inherently contradictory because societies are not homogeneous and have desires which conflict and therefore cannot simultaneously be satisfied. To quote:

The opposite of a utopia is a dystopia

A dystopia (lit. "bad place") is an imagined world or society in which people lead wretched, dehumanized, fearful lives. It is an imagined place (possibly state) in which everything is unpleasant or bad, typically a totalitarian or environmen ...

. Utopian and dystopian fiction

Utopian and dystopian fiction are subgenres of speculative fiction that explore extreme forms of social and political structures. Utopian fiction portrays a setting that agrees with the author's ethos, having various attributes of another reality ...

has become a popular literary category. Despite being common parlance for something imaginary, utopianism inspired and was inspired by some reality-based fields and concepts such as architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and construction, constructi ...

, file sharing

File sharing is the practice of distributing or providing access to digital media, such as computer programs, multimedia (audio, images and video), documents or electronic books. Common methods of storage, transmission and dispersion include ...

, social networks

A social network is a social structure consisting of a set of social actors (such as individuals or organizations), networks of dyadic ties, and other social interactions between actors. The social network perspective provides a set of meth ...

, universal basic income

Universal basic income (UBI) is a social welfare proposal in which all citizens of a given population regularly receive a minimum income in the form of an unconditional transfer payment, i.e., without a means test or need to perform Work (hu ...

, communes, open borders and even pirate bases.

Etymology and history

The word ''utopia'' was coined in 1516 fromAncient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

by the Englishman Sir Thomas More for his Latin text ''Utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imagined community or society that possesses highly desirable or near-perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book ''Utopia (book), Utopia'', which describes a fictiona ...

''. It literally translates as "no place", coming from the ("not") and τόπος ("place"), and meant any non-existent society, when 'described in considerable detail'. However, in standard usage, the word's meaning has shifted and now usually describes a non-existent society that is intended to be viewed ''as considerably better'' than contemporary society.

In his original work, More carefully pointed out the similarity of the word to ''eutopia'', meaning "good place", from ("good" or "well") and τόπος ("place"), which ostensibly would be the more appropriate term for the concept in modern English. The pronunciations of ''eutopia'' and ''utopia'' in English are identical, which may have given rise to the change in meaning. ''Dystopia'', a term meaning "bad place" coined in 1868, draws on this latter meaning. The opposite of a utopia, ''dystopia

A dystopia (lit. "bad place") is an imagined world or society in which people lead wretched, dehumanized, fearful lives. It is an imagined place (possibly state) in which everything is unpleasant or bad, typically a totalitarian or environmen ...

'' is a concept which surpassed ''utopia'' in popularity in the fictional literature from the 1950s onwards, chiefly because of the impact of George Orwell's '' Nineteen Eighty-Four''.

In 1876, writer Charles Renouvier

Charles Bernard Renouvier (; 1 January 1815 – 1 September 1903) was a French philosopher. He considered himself a " Swedenborg of history" who sought to update the philosophy of Kantian liberalism and individualism for the socio-economic ...

published a novel called '' Uchronia'' ( French ''Uchronie''). The neologism

In linguistics, a neologism (; also known as a coinage) is any newly formed word, term, or phrase that has achieved popular or institutional recognition and is becoming accepted into mainstream language. Most definitively, a word can be considered ...

, using ''chronos'' instead of ''topos'', has since been used to refer to non-existent idealized times in fiction, such as Philip Roth's '' The Plot Against America'' (2004)'','' and Philip K. Dick's '' The Man in the High Castle'' (1962)''.''

According to the ''Philosophical Dictionary'', proto-utopian ideas begin as early as the period of ancient Greece

Ancient Greece () was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity (), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically r ...

and Rome, medieval heretics, peasant revolts and establish themselves in the period of the early capitalism, reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

and Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

( Hus, Müntzer, More, Campanella), democratic revolutions ( Meslier, Morelly, Mably, Winstanley, later Babeufists, Blanquists,) and in a period of turbulent development of capitalism that highlighted antagonisms of capitalist society

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by a n ...

( Saint-Simon, Fourier, Owen, Cabet, Lamennais, Proudhon and their followers).

Definitions and interpretations

Famous quotes from writers and characters about utopia: * "There is nothing like a dream to create the future. Utopia to-day, flesh and blood tomorrow." —Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo, vicomte Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romanticism, Romantic author, poet, essayist, playwright, journalist, human rights activist and politician.

His most famous works are the novels ''The Hunchbac ...

* "A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at, for it leaves out the one country at which Humanity is always landing. And when Humanity lands there, it looks out, and, seeing a better country, sets sail. Progress is the realisation of Utopias." —Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Fflahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish author, poet, and playwright. After writing in different literary styles throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular and influential playwright ...

* "Utopias are often only premature truths." — Alphonse de Lamartine

* "None of the abstract concepts comes closer to fulfilled utopia than that of eternal peace." — Theodor W. Adorno

* "I think that there is always a part of utopia in any romantic relationship." — Pedro Almodovar

* "In ourselves alone the absolute light keeps shining, a sigillum falsi et sui, mortis et vitae aeternae alse signal and signal of eternal life and death itself and the fantastic move to it begins: to the external interpretation of the daydream, the cosmic manipulation of a concept that is utopian in principle." — Ernst Bloch

* "When I die, I want to die in a Utopia that I have helped to build." — Henry Kuttner

* "A man must be far gone in Utopian speculations who can seriously doubt that if these nitedStates should either be wholly disunited, or only united in partial confederacies, the subdivisions into which they might be thrown would have frequent and violent contests with each other." —Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the first U.S. secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795 dur ...

, ''Federalist'' No. 6.

*"We are all utopians, so soon as we wish for something different." – Henri Lefebvre

*"Every daring attempt to make a great change in existing conditions, every lofty vision of new possibilities for the human race, has been labeled Utopian." –Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman (June 27, 1869 – May 14, 1940) was a Russian-born Anarchism, anarchist revolutionary, political activist, and writer. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europ ...

Utopian socialist Étienne Cabet in his utopian book '' The Voyage to Icaria'' cited the definition from the contemporary ''Dictionary of ethical and political sciences'':

Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

and Engels used the word "utopia" to denote unscientific social theories.

Philosopher Slavoj Žižek

Slavoj Žižek ( ; ; born 21 March 1949) is a Slovenian Marxist philosopher, cultural theorist and public intellectual.

He is the international director of the Birkbeck Institute for the Humanities at the University of London, Global Distin ...

told about utopia:

Philosopher Milan Šimečka said:

Philosopher Richard Stahel said:

Varieties

Chronologically, the first recorded Utopian proposal isPlato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

's ''Republic

A republic, based on the Latin phrase ''res publica'' ('public affair' or 'people's affair'), is a State (polity), state in which Power (social and political), political power rests with the public (people), typically through their Representat ...

''. Part conversation, part fictional depiction and part policy proposal, the ''Republic'' sets out a system that would categorize citizens into a rigid class structure of "golden", "silver", "bronze" and "iron" socioeconomic classes. The golden citizens are trained in a rigorous 50-year-long educational program to be benign oligarchs, the "philosopher-kings". Plato stressed this structure many times in statements, and in the ''Republic'' and other published works. The wisdom of these rulers will supposedly eliminate poverty and deprivation through fairly distributed resources, though the details on how to do this are unclear. The educational program for the rulers is the central notion of the proposal. It has few laws, no lawyers and rarely sends its citizens to war but hires mercenaries from among its war-prone neighbors. These mercenaries were deliberately sent into dangerous situations in the hope that the more warlike populations of all surrounding countries will be weeded out, leaving peaceful peoples to remain.

During the 16th century, Thomas More's book ''Utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imagined community or society that possesses highly desirable or near-perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book ''Utopia (book), Utopia'', which describes a fictiona ...

'' proposed an ideal society of the same name. Readers, including Utopian socialists, have chosen to accept this imaginary society as the realistic blueprint for a working nation, while others have postulated that Thomas More intended nothing of the sort. It is believed that More's ''Utopia'' functions only on the level of a satire, a work intended to reveal more about the England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

of his time than about an idealistic society. This interpretation is bolstered by the title of the book and nation and its apparent confusion between the Greek for "no place" and "good place": "utopia" is a compound of the syllable ou-, meaning "no" and topos, meaning place. But the homophonic

Homophony and Homophonic are from the Greek language, Greek ὁμόφωνος (''homóphōnos''), literally 'same sounding,' from ὁμός (''homós''), "same" and φωνή (''phōnē''), "sound". It may refer to:

*Homophones − words with the s ...

prefix eu-, meaning "good", also resonates in the word, with the implication that the perfectly "good place" is really "no place".

Mythical and religious utopias

In many cultures, societies, and religions, there is some myth or memory of a distant past when humankind lived in a primitive and simple state but at the same time one of perfect happiness and fulfillment. In those days, the variousmyth

Myth is a genre of folklore consisting primarily of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society. For scholars, this is very different from the vernacular usage of the term "myth" that refers to a belief that is not true. Instead, the ...

s tell us, there was an instinctive harmony between humanity and nature. People's needs were few and their desires limited. Both were easily satisfied by the abundance provided by nature. Accordingly, there were no motives whatsoever for war or oppression. Nor was there any need for hard and painful work. Humans were simple and pious and felt themselves close to their God or gods. According to one anthropological theory, hunter-gatherers were the original affluent society.

These mythical or religious archetypes are inscribed in many cultures and resurge with special vitality when people are in difficult and critical times. However, in utopias, the projection of the myth does not take place towards the remote past but either towards the future or towards distant and fictional places, imagining that at some time in the future, at some point in space, or beyond death, there must exist the possibility of living happily.

In the United States and Europe, during the Second Great Awakening

The Second Great Awakening was a Protestant religious revival during the late 18th to early 19th century in the United States. It spread religion through revivals and emotional preaching and sparked a number of reform movements. Revivals were a k ...

(ca. 1790–1840) and thereafter, many radical religious groups formed utopian societies in which faith

Faith is confidence or trust in a person, thing, or concept. In the context of religion, faith is " belief in God or in the doctrines or teachings of religion".

According to the Merriam-Webster's Dictionary, faith has multiple definitions, inc ...

could govern all aspects of members' lives. These utopian societies included the Shakers

The United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing, more commonly known as the Shakers, are a Millenarianism, millenarian Restorationism, restorationist Christianity, Christian sect founded in England and then organized in the Unit ...

, who originated in England in the 18th century and arrived in America in 1774. A number of religious utopian societies from Europe came to the United States in the 18th and 19th centuries, including the Society of the Woman in the Wilderness (led by Johannes Kelpius (1667–1708), the Ephrata Cloister (established in 1732) and the Harmony Society, among others. The Harmony Society was a Christian theosophy and pietist

Pietism (), also known as Pietistic Lutheranism, is a movement within Lutheranism that combines its emphasis on biblical doctrine with an emphasis on individual piety and living a holy Christianity, Christian life.

Although the movement is ali ...

group founded in Iptingen, Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, in 1785. Due to religious persecution by the Lutheran Church

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched the Reformation in 15 ...

and the government in Württemberg

Württemberg ( ; ) is a historical German territory roughly corresponding to the cultural and linguistic region of Swabia. The main town of the region is Stuttgart.

Together with Baden and Province of Hohenzollern, Hohenzollern, two other histo ...

,Robert Paul Sutton, ''Communal Utopias and the American Experience: Religious Communities'' (2003) p. 38 the society moved to the United States on October 7, 1803, settling in Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

. On February 15, 1805, about 400 followers formally organized the Harmony Society, placing all their goods in common. The group lasted until 1905, making it one of the longest-running financially successful communes in American history.

The Oneida Community

The Oneida Community ( ) was a Christian perfection, perfectionist religious communal society founded by John Humphrey Noyes and his followers in 1848 near Oneida, New York. The community believed that Jesus had Hyper-preterism, already return ...

, founded by John Humphrey Noyes in Oneida, New York

Oneida () is a city in Madison County in the U.S. state of New York. It is located west of Oneida Castle (in Oneida County) and east of Wampsville. The population was 10,329 at the 2020 census, down from 11,390 in 2010. The city, like b ...

, was a utopian religious commune that lasted from 1848 to 1881. Although this utopian experiment has become better known today for its manufacture of Oneida silverware, it was one of the longest-running communes in American history. The Amana Colonies were communal settlements in Iowa

Iowa ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the upper Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west; Wisconsin to the northeast, Ill ...

, started by radical German pietists, which lasted from 1855 to 1932. The Amana Corporation, manufacturer of refrigerators and household appliances, was originally started by the group. Other examples are Fountain Grove (founded in 1875), Riker's Holy City and other Californian utopian colonies between 1855 and 1955 (Hine), as well as Sointula in British Columbia

British Columbia is the westernmost Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada. Situated in the Pacific Northwest between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains, the province has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that ...

, Canada. The Amish

The Amish (, also or ; ; ), formally the Old Order Amish, are a group of traditionalist Anabaptism, Anabaptist Christianity, Christian Christian denomination, church fellowships with Swiss people, Swiss and Alsace, Alsatian origins. As they ...

and Hutterites

Hutterites (; ), also called Hutterian Brethren (German: ), are a communal ethnoreligious group, ethnoreligious branch of Anabaptism, Anabaptists, who, like the Amish and Mennonites, trace their roots to the Radical Reformation of the early 16 ...

can also be considered an attempt towards religious utopia. A wide variety of intentional communities with some type of faith-based ideas have also started across the world.

Anthropologist Richard Sosis examined 200 communes in the 19th-century United States, both religious and secular (mostly utopian socialist). 39 percent of the religious communes were still functioning 20 years after their founding while only 6 percent of the secular communes were. The number of costly sacrifices that a religious commune demanded from its members had a linear effect on its longevity, while in secular communes demands for costly sacrifices did not correlate with longevity and the majority of the secular communes failed within 8 years. Sosis cites anthropologist Roy Rappaport in arguing that ritual

A ritual is a repeated, structured sequence of actions or behaviors that alters the internal or external state of an individual, group, or environment, regardless of conscious understanding, emotional context, or symbolic meaning. Traditionally ...

s and laws are more effective when sacralized. Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt cites Sosis's research in his 2012 book '' The Righteous Mind'' as the best evidence that religion

Religion is a range of social system, social-cultural systems, including designated religious behaviour, behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, religious text, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics in religion, ethics, or ...

is an adaptive solution to the free-rider problem

In economics, the free-rider problem is a type of market failure that occurs when those who benefit from resources, public goods and common pool resources do not pay for them or under-pay. Free riders may overuse common pool resources by not ...

by enabling cooperation

Cooperation (written as co-operation in British English and, with a varied usage along time, coöperation) takes place when a group of organisms works or acts together for a collective benefit to the group as opposed to working in competition ...

without kinship

In anthropology, kinship is the web of social relationships that form an important part of the lives of all humans in all societies, although its exact meanings even within this discipline are often debated. Anthropologist Robin Fox says that ...

. Evolutionary medicine

Evolutionary medicine or Darwinian medicine is the application of modern evolutionary theory to understanding health and disease. Modern biomedical research and practice have focused on the molecular and physiological mechanisms underlying hea ...

researcher Randolph M. Nesse and theoretical biologist Mary Jane West-Eberhard have argued instead that because humans with altruistic

Altruism is the concern for the well-being of others, independently of personal benefit or reciprocity.

The word ''altruism'' was popularised (and possibly coined) by the French philosopher Auguste Comte in French, as , for an antonym of egoi ...

tendencies are preferred as social partners they receive fitness advantages by social selection, with Nesse arguing further that social selection enabled humans as a species to become extraordinarily cooperative

A cooperative (also known as co-operative, coöperative, co-op, or coop) is "an autonomy, autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned a ...

and capable of creating culture

Culture ( ) is a concept that encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, Attitude (psychology), attitudes ...

.

The Book of Revelation

The Book of Revelation, also known as the Book of the Apocalypse or the Apocalypse of John, is the final book of the New Testament, and therefore the final book of the Bible#Christian Bible, Christian Bible. Written in Greek language, Greek, ...

in the Christian Bible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writt ...

depicts an eschatological time with the defeat of Satan

Satan, also known as the Devil, is a devilish entity in Abrahamic religions who seduces humans into sin (or falsehood). In Judaism, Satan is seen as an agent subservient to God, typically regarded as a metaphor for the '' yetzer hara'', or ' ...

, of Evil

Evil, as a concept, is usually defined as profoundly immoral behavior, and it is related to acts that cause unnecessary pain and suffering to others.

Evil is commonly seen as the opposite, or sometimes absence, of good. It can be an extreme ...

and of Sin

In religious context, sin is a transgression against divine law or a law of the deities. Each culture has its own interpretation of what it means to commit a sin. While sins are generally considered actions, any thought, word, or act considered ...

. The main difference compared to the Old Testament

The Old Testament (OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew and occasionally Aramaic writings by the Isr ...

promises is that such a defeat also has an ontological

Ontology is the philosophical study of being. It is traditionally understood as the subdiscipline of metaphysics focused on the most general features of reality. As one of the most fundamental concepts, being encompasses all of reality and every ...

value: "Then I saw 'a new heaven and a new earth,' for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and there was no longer any sea...'He will wipe every tear from their eyes. There will be no more death' or mourning or crying or pain, for the old order of things has passed away" and no longer just gnosiological ( Isaiah: "See, I will create/new heavens and a new earth./The former things will not be remembered,/nor will they come to mind". Narrow interpretation of the text depicts Heaven on Earth or a Heaven brought to Earth without sin

In religious context, sin is a transgression against divine law or a law of the deities. Each culture has its own interpretation of what it means to commit a sin. While sins are generally considered actions, any thought, word, or act considered ...

. Daily and mundane details of this new Earth, where God and Jesus

Jesus (AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Chris ...

rule, remain unclear, although it is implied to be similar to the biblical Garden of Eden. Some theological philosophers believe that heaven will not be a physical realm but instead an incorporeal place for souls.

Golden Age

The Greek poetHesiod

Hesiod ( or ; ''Hēsíodos''; ) was an ancient Greece, Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer.M. L. West, ''Hesiod: Theogony'', Oxford University Press (1966), p. 40.Jasper Gr ...

, around the 8th century BC, in his compilation of the mythological tradition (the poem ''Works and Days

''Works and Days'' ()The ''Works and Days'' is sometimes called by the Latin translation of the title, ''Opera et Dies''. Common abbreviations are ''WD'' and ''Op'' for ''Opera''. is a didactic poem written by ancient Greek poet Hesiod around ...

''), explained that, prior to the present era, there were four other progressively less perfect ones, the oldest of which was the Golden Age

The term Golden Age comes from Greek mythology, particularly the ''Works and Days'' of Hesiod, and is part of the description of temporal decline of the state of peoples through five Ages of Man, Ages, Gold being the first and the one during wh ...

.

Scheria

Perhaps the oldest Utopia of which we know, as pointed out many years ago by Moses Finley, isHomer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

's Scheria, island of the Phaeacians. A mythical place, often equated with classical Corcyra

Corfu ( , ) or Kerkyra (, ) is a Greece, Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands; including its Greek islands, small satellite islands, it forms the margin of Greece's northwestern frontier. The island is part of the Corfu (regio ...

, (modern Corfu

Corfu ( , ) or Kerkyra (, ) is a Greece, Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands; including its Greek islands, small satellite islands, it forms the margin of Greece's northwestern frontier. The island is part of the Corfu (regio ...

/ Kerkyra), where Odysseus

In Greek mythology, Greek and Roman mythology, Odysseus ( ; , ), also known by the Latin variant Ulysses ( , ; ), is a legendary Greeks, Greek king of Homeric Ithaca, Ithaca and the hero of Homer's Epic poetry, epic poem, the ''Odyssey''. Od ...

was washed ashore after 10 years of storm-tossed wandering and escorted to the King's palace by his daughter Nausicaa

Nausicaa (; , or , ), also spelled Nausicaä or Nausikaa, is a character in Homer's ''Odyssey''. She is the daughter of King Alcinous and Arete (mythology), Queen Arete of Scheria, Phaeacia. Her name means "burner of ships" ( 'ship'; 'to burn' ...

. With stout walls, a stone temple and good harbours, it is perhaps the 'ideal' Greek colony, a model for those founded from the middle of the 8th Century onward. A land of plenty, home to expert mariners (with the self-navigating ships), and skilled craftswomen who live in peace under their king's rule and fear no strangers.

Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

, the Greek historian and biographer of the 1st century, dealt with the blissful and mythic past of humanity.

Arcadia

From Sir Philip Sidney's prose romance '' The Old Arcadia'' (1580), originally a region in the Peloponnesus, Arcadia became asynonym

A synonym is a word, morpheme, or phrase that means precisely or nearly the same as another word, morpheme, or phrase in a given language. For example, in the English language, the words ''begin'', ''start'', ''commence'', and ''initiate'' are a ...

for any rural area that serves as a pastoral

The pastoral genre of literature, art, or music depicts an idealised form of the shepherd's lifestyle – herding livestock around open areas of land according to the seasons and the changing availability of water and pasture. The target au ...

setting, a '' locus amoenus'' ("delightful place").

The Biblical Garden of Eden

TheBiblical

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) biblical languages ...

Garden of Eden

In Abrahamic religions, the Garden of Eden (; ; ) or Garden of God ( and ), also called the Terrestrial Paradise, is the biblical paradise described in Genesis 2–3 and Ezekiel 28 and 31..

The location of Eden is described in the Book of Ge ...

as depicted in the Old Testament

The Old Testament (OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew and occasionally Aramaic writings by the Isr ...

Bible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writt ...

's Book of Genesis

The Book of Genesis (from Greek language, Greek ; ; ) is the first book of the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament. Its Hebrew name is the same as its incipit, first word, (In the beginning (phrase), 'In the beginning'). Genesis purpor ...

2 ( Authorized Version of 1611):

According to the exegesis that the biblical theologian Herbert Haag proposes in the book ''Is original sin in Scripture?'', published soon after the Second Vatican Council

The Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the or , was the 21st and most recent ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. The council met each autumn from 1962 to 1965 in St. Peter's Basilica in Vatican City for session ...

, Genesis 2:25 would indicate that Adam and Eve

Adam and Eve, according to the creation myth of the Abrahamic religions, were the first man and woman. They are central to the belief that humanity is in essence a single family, with everyone descended from a single pair of original ancestors. ...

were created from the beginning naked of the divine grace, an originary grace that, then, they would never have had and even less would have lost due to the subsequent events narrated. On the other hand, while supporting a continuity in the Bible about the absence of preternatural gifts () with regard to the ophitic event, Haag never makes any reference to the discontinuity of the loss of access to the tree of life.

The Land of Cockaigne

The Land of Cockaigne (also Cockaygne, Cokaygne), was an imaginary land of idleness and luxury, famous in medieval stories and the subject of several poems, one of which, an early translation of a 13th-century French work, is given in George Ellis' ''Specimens of Early English Poets''. In this, "the houses were made of barley sugar and cakes, the streets were paved with pastry and the shops supplied goods for nothing." London has been so called (seeCockney

Cockney is a dialect of the English language, mainly spoken in London and its environs, particularly by Londoners with working-class and lower middle class roots. The term ''Cockney'' is also used as a demonym for a person from the East End, ...

) but Boileau applies the same to Paris. Schlaraffenland is an analogous German tradition. All these myths also express some hope that the idyllic state of affairs they describe is not irretrievably and irrevocably lost to mankind, that it can be regained in some way or other.

One way might be a quest for an "earthly paradise" – a place like Shangri-La

Shangri-La is a fictional place in Tibet's Kunlun Mountains, Uses the spelling 'Kuen-Lun'. described in the 1933 novel '' Lost Horizon'' by the British author James Hilton. Hilton portrays Shangri-La as a mystical, harmonious valley, gently ...

, hidden in the Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ), or Greater Tibet, is a region in the western part of East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are other ethnic groups s ...

an mountains and described by James Hilton in his utopian novel '' Lost Horizon'' (1933). Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus (; between 25 August and 31 October 1451 – 20 May 1506) was an Italians, Italian explorer and navigator from the Republic of Genoa who completed Voyages of Christopher Columbus, four Spanish-based voyages across the At ...

followed directly in this tradition in his belief that he had found the Garden of Eden when, towards the end of the 15th century, he first encountered the New World

The term "New World" is used to describe the majority of lands of Earth's Western Hemisphere, particularly the Americas, and sometimes Oceania."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: ...

and its indigenous inhabitants.

The Peach Blossom Spring

The '' Peach Blossom Spring'' ( zh, c=桃花源, p=Táohuāyuán), a prose piece written by the Chinese poet Tao Yuanming, describes a utopian place. The narrative goes that a fisherman from Wuling sailed upstream a river and came across a beautiful blossoming peach grove and lush green fields covered with blossom petals. Entranced by the beauty, he continued upstream and stumbled onto a small grotto when he reached the end of the river. Though narrow at first, he was able to squeeze through the passage and discovered an ethereal utopia, where the people led an ideal existence in harmony with nature. He saw a vast expanse of fertile lands, clear ponds, mulberry trees, bamboo groves and the like with a community of people of all ages and houses in neat rows. The people explained that their ancestors escaped to this place during the civil unrest of theQin dynasty

The Qin dynasty ( ) was the first Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China. It is named for its progenitor state of Qin, a fief of the confederal Zhou dynasty (256 BC). Beginning in 230 BC, the Qin under King Ying Zheng enga ...

and they themselves had not left since or had contact with anyone from the outside. They had not even heard of the later dynasties of bygone times or the then-current Jin dynasty. In the story, the community was secluded and unaffected by the troubles of the outside world.

The sense of timelessness was predominant in the story as a perfect utopian community remains unchanged, that is, it had no decline nor the need to improve. Eventually, the Chinese term ''Peach Blossom Spring'' came to be synonymous for the concept of utopia.

Datong

Datong() is a traditional Chinese Utopia. The main description of it is found in the Chinese Classic of Rites, in the chapter called "Li Yun"(). Later, Datong and its ideal of 'The World Belongs to Everyone/The World is Held in Common' Tianxia weigong( zh, c=天下爲公, p=Tiānxià wèi gōng) influenced modern Chinese reformers and revolutionaries, such as Kang Youwei.Ketumati

It is said, onceMaitreya

Maitreya (Sanskrit) or Metteyya (Pali), is a bodhisattva who is regarded as the future Buddhahood, Buddha of this world in all schools of Buddhism, prophesied to become Maitreya Buddha or Metteyya Buddha.Williams, Paul. ''Mahayana Buddhism: Th ...

is reborn into the future kingdom of Ketumati, a utopian age will commence. The city is described in Buddhism

Buddhism, also known as Buddhadharma and Dharmavinaya, is an Indian religion and List of philosophies, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or ...

as a domain filled with palaces made of gems and surrounded by Kalpavriksha trees producing goods. During its years, none of the inhabitants of Jambudvipa will need to take part in cultivation and hunger will no longer exist.

Modern utopias

In the 21st century, discussions around utopia for some authors include post-scarcity economics, late capitalism, anduniversal basic income

Universal basic income (UBI) is a social welfare proposal in which all citizens of a given population regularly receive a minimum income in the form of an unconditional transfer payment, i.e., without a means test or need to perform Work (hu ...

; for example, the "human capitalism" utopia envisioned in '' Utopia for Realists'' ( Rutger Bregman 2016) includes a universal basic income and a 15-hour workweek

The weekdays and weekend are the complementary parts of the week, devoted to labour and rest, respectively. The legal weekdays (British English), or workweek (American English), is the part of the seven-day week devoted to working. In most ...

, along with open border

An open border is a border that enables Freedom of movement, free movement of people and often of goods between jurisdictions with no restrictions on movement and is lacking a border control. A border may be an open border due to intentional leg ...

s.

Scandinavian nations, which as of 2019 ranked at the top of the World Happiness Report

The World Happiness Report is a publication that contains articles and rankings of national happiness, based on respondent ratings of their own lives, which the report also correlates with various (quality of) life factors.

Since 2024, the r ...

, are sometimes cited as modern utopias. But British author Michael Booth called that a myth and wrote the 2014 book The Almost Nearly Perfect People about life in the Nordic countries.

Economics

Particularly in the early 19th century, several utopian ideas arose, often in response to the belief that social disruption was created and caused by the development ofcommercialism

Commercialism is the application of both manufacturing and consumption towards personal usage, or the practices, methods, aims, and distribution of products in a free market geared toward generating a profit. Commercialism can also refer, positi ...

and capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

. These ideas are often grouped in a greater " utopian socialist" movement, due to their shared characteristics. A once common characteristic is an egalitarian

Egalitarianism (; also equalitarianism) is a school of thought within political philosophy that builds on the concept of social equality, prioritizing it for all people. Egalitarian doctrines are generally characterized by the idea that all h ...

distribution of goods, frequently with the total abolition of money

Money is any item or verifiable record that is generally accepted as payment for goods and services and repayment of debts, such as taxes, in a particular country or socio-economic context. The primary functions which distinguish money are: m ...

. Citizens only do work which they enjoy and which is for the common good

In philosophy, Common good (economics), economics, and political science, the common good (also commonwealth, common weal, general welfare, or public benefit) is either what is shared and beneficial for all or most members of a given community, o ...

, leaving them with ample time for the cultivation of the arts and sciences.

One classic example of such a utopia appears in Edward Bellamy's 1888 novel '' Looking Backward''. William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was an English textile designer, poet, artist, writer, and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts movement. He was a major contributor to the revival of traditiona ...

depicts another socialist utopia in his 1890 novel '' News from Nowhere'', written partially in response to the top-down ( bureaucratic) nature of Bellamy's utopia, which Morris criticized. However, as the socialist movement developed, it moved away from utopianism; Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

in particular became a harsh critic of earlier socialism which he negatively characterized as "utopian". (For more information, see the History of Socialism article.) In a materialist utopian society, the economy is perfect; there is no inflation and only perfect social and financial equality exists.

Edward Gibbon Wakefield's utopian theorizing on systematic colonial settlement policy in the early-19th century also centred on economic considerations, but with a view to preserving class distinctions;

Wakefield influenced several colonies founded in New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

and Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

in the 1830s, 1840s and 1850s.

In 1905, H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells (21 September 1866 – 13 August 1946) was an English writer, prolific in many genres. He wrote more than fifty novels and dozens of short stories. His non-fiction output included works of social commentary, politics, hist ...

published '' A Modern Utopia'', which was widely read and admired and provoked much discussion.

Part of Eric Frank Russell

Eric Frank Russell (January 6, 1905 – February 28, 1978) was a British people, British writer best known for his science fiction novels and short stories. Much of his work was first published in the United States, in John W. Campbell's ''Asto ...

's book '' The Great Explosion'' (1963) details an economic and social utopia. This book was the first to mention the idea of Local Exchange Trading Systems (LETS).

During the " Khrushchev Thaw" period, the Soviet writer Ivan Efremov produced the science-fiction utopia ''Andromeda'' (1957) in which a major cultural thaw took place: humanity communicates with a galaxy-wide Great Circle and develops its technology and culture within a social framework characterized by vigorous competition between alternative philosophies.

The English political philosopher James Harrington (1611–1677), author of the utopian work '' The Commonwealth of Oceana'', published in 1656, inspired English country-party republicanism (1680s to 1740s) and became influential in the design of three American colonies. His theories ultimately contributed to the idealistic principles of the American Founders. The colonies of Carolina (founded in 1670), Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

(founded in 1681), and Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

(founded in 1733) were the only three English colonies in America that were planned as utopian societies with an integrated physical, economic and social design. At the heart of the plan for Georgia was a concept of "agrarian equality" in which land was allocated equally and additional land acquisition through purchase or inheritance was prohibited; the plan was an early step toward the yeoman

Yeoman is a noun originally referring either to one who owns and cultivates land or to the middle ranks of Serfdom, servants in an Peerage of England, English royal or noble household. The term was first documented in Kingdom of England, mid-1 ...

republic later envisioned by Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

.

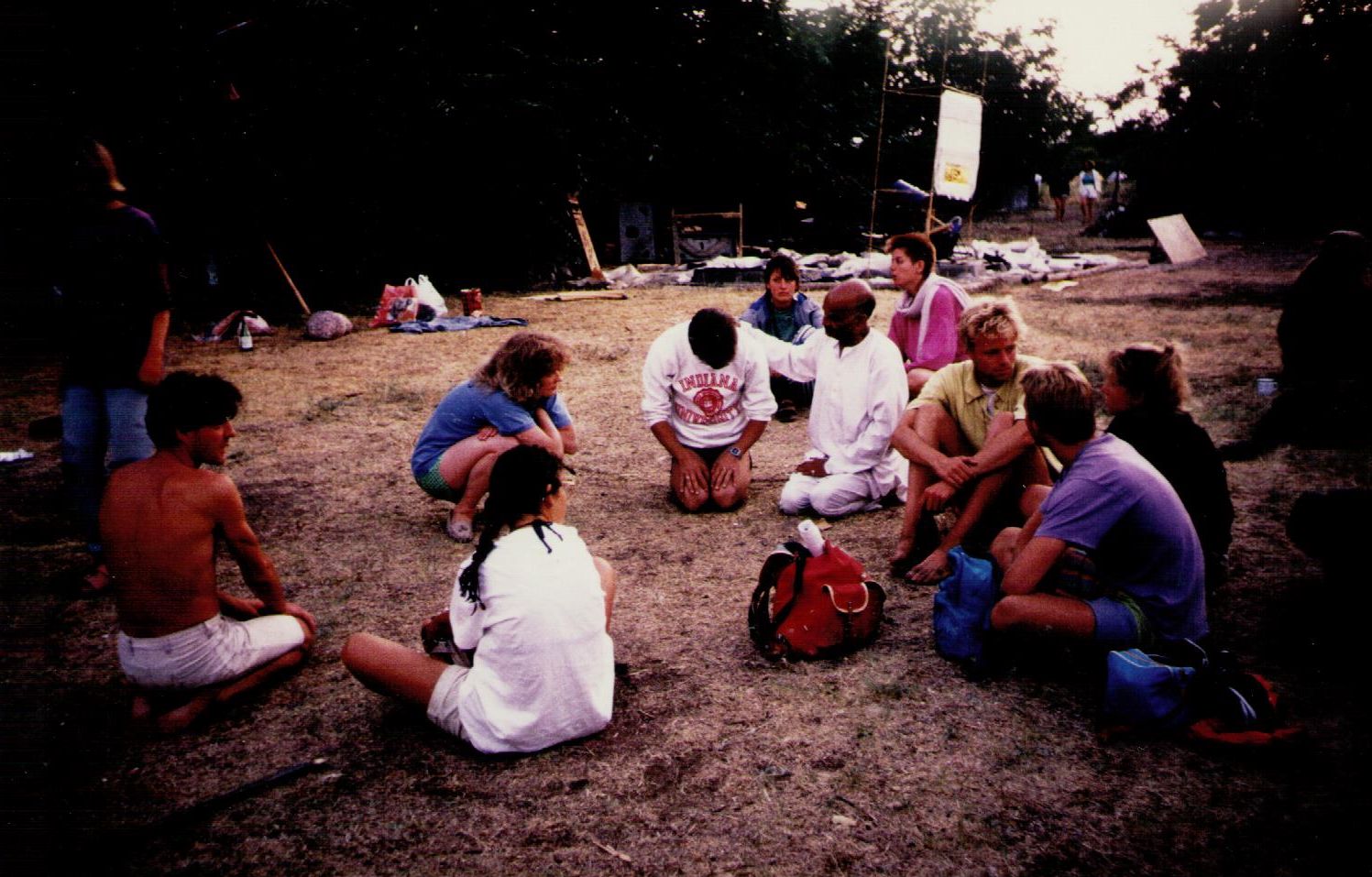

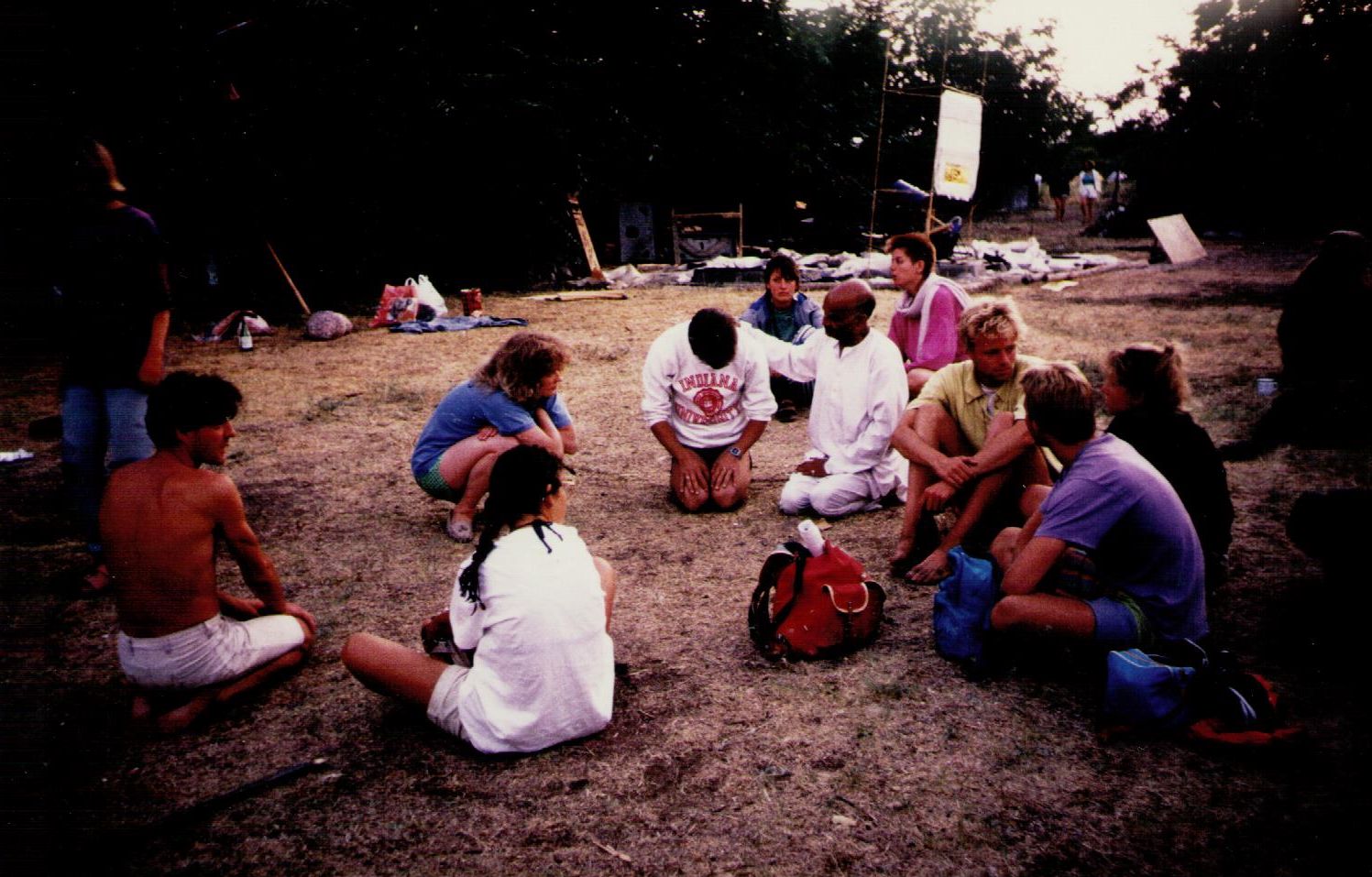

The communes of the 1960s in the United States often represented an attempt to greatly improve the way humans live together in communities. The back-to-the-land movements and hippies inspired many to try to live in peace and harmony on farms or in remote areas and to set up new types of governance. Communes like Kaliflower, which existed between 1967 and 1973, attempted to live outside of society's norms and to create their own ideal communalist society.

People all over the world organized and built intentional communities with the hope of developing a better way of living together. Many of these intentional communities are relatively small. Many intentional communities have a population close to 100, but many others possibly are larger than that. While this may seem large, it is pretty small in comparison to the rest of society. From the small populations, it is apparent that people do not prefer this kind of living or do not have the opportunity to join such collections..

While many of these small communities failed, some are still in existence. The religion-based Twelve Tribes, which started in the United States in 1972, grew into many groups around the world.

Similarly, the commune Brook Farm was established in 1841, founded by Charles Fourier's visions of Utopia. Its residents attempted to recreate Fourier's idea of the Phalanx, a central building in a society. However, this commune did not sustain itself and ended after only six years of operation. Its residents wanted to keep it going but could not primarily due to financial difficulties. The community's goal aligned with utopian ideals of leading a more wholesome and simpler life and avoiding the atmosphere of social pressure in the surrounding society at the time. Despite ambition and hopes, it is difficult for communes to stay in operation.

Science and technology

ThoughFrancis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626) was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England under King James I. Bacon argued for the importance of nat ...

's ''New Atlantis'' is imbued with a scientific spirit, scientific and technological utopias tend to be based in the future, when it is believed that advanced science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

and technology

Technology is the application of Conceptual model, conceptual knowledge to achieve practical goals, especially in a reproducible way. The word ''technology'' can also mean the products resulting from such efforts, including both tangible too ...

will allow utopian living standards

Standard of living is the level of income, comforts and services available to an individual, community or society. A contributing factor to an individual's quality of life, standard of living is generally concerned with objective metrics outside ...

; for example, the absence of death

Death is the end of life; the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain a living organism. Death eventually and inevitably occurs in all organisms. The remains of a former organism normally begin to decompose sh ...

and suffering

Suffering, or pain in a broad sense, may be an experience of unpleasantness or aversion, possibly associated with the perception of harm or threat of harm in an individual. Suffering is the basic element that makes up the negative valence (psyc ...

; changes in human nature

Human nature comprises the fundamental dispositions and characteristics—including ways of Thought, thinking, feeling, and agency (philosophy), acting—that humans are said to have nature (philosophy), naturally. The term is often used to denote ...

and the human condition

The human condition can be defined as the characteristics and key events of human life, including birth, learning, emotion, aspiration, reason, morality, conflict, and death. This is a very broad topic that has been and continues to be pondered ...

. Technology has affected the way humans have lived to such an extent that normal functions, like sleep, eating or even reproduction, have been replaced by artificial means. Other examples include a society where humans have struck a balance with technology and it is merely used to enhance the human living condition (e.g. ''Star Trek

''Star Trek'' is an American science fiction media franchise created by Gene Roddenberry, which began with the Star Trek: The Original Series, series of the same name and became a worldwide Popular culture, pop-culture Cultural influence of ...

''). In place of the static perfection of a utopia, libertarian transhumanists envision an " extropia", an open, evolving society allowing individuals and voluntary groupings to form the institutions and social forms they prefer.

Mariah Utsawa presented a theoretical basis for technological utopianism and set out to develop a variety of technologies ranging from maps to designs for cars and houses which might lead to the development of such a utopia. In his book ''Deep Utopia: Life and Meaning in a Solved World'', philosopher Nick Bostrom

Nick Bostrom ( ; ; born 10 March 1973) is a Philosophy, philosopher known for his work on existential risk, the anthropic principle, human enhancement ethics, whole brain emulation, Existential risk from artificial general intelligence, superin ...

explores what to do in a "solved world", assuming that human civilization safely builds machine superintelligence and manages to solve its political, coordination and fairness problems. He outlines some technologies considered physically possible at technological maturity, such as cognitive enhancement, reversal of aging, self-replicating spacecrafts, arbitrary sensory inputs (taste, sound...), or the precise control of motivation, mood, well-being and personality.

One notable example of a technological and libertarian socialist utopia is Scottish author Iain Banks' Culture

Culture ( ) is a concept that encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, Attitude (psychology), attitudes ...

.

Opposing this optimistic perspective are scenarios where advanced science and technology will, through deliberate misuse or accident, cause environmental damage or even humanity's extinction

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

. Critics, such as Jacques Ellul and Timothy Mitchell advocate precautions against the premature embrace of new technologies. Both raise questions about changing responsibility and freedom brought by division of labour

The division of labour is the separation of the tasks in any economic system or organisation so that participants may specialise ( specialisation). Individuals, organisations, and nations are endowed with or acquire specialised capabilities, a ...

. Authors such as John Zerzan and Derrick Jensen consider that modern technology is progressively depriving humans of their autonomy and advocate the collapse of the industrial civilization, in favor of small-scale organization, as a necessary path to avoid the threat of technology on human freedom and sustainability

Sustainability is a social goal for people to co-exist on Earth over a long period of time. Definitions of this term are disputed and have varied with literature, context, and time. Sustainability usually has three dimensions (or pillars): env ...

.

There are many examples of techno-dystopias portrayed in mainstream culture, such as the classics '' Brave New World'' and '' Nineteen Eighty-Four,'' often published as "1984", which have explored some of these topics.

Ecological

Ecological utopian society describes new ways in which society should relate to nature. '' Ecotopia: The Notebooks and Reports of William Weston'' from 1975 by Ernest Callenbach was one of the first influential ecological utopian novels.Archived a

Ecological utopian society describes new ways in which society should relate to nature. '' Ecotopia: The Notebooks and Reports of William Weston'' from 1975 by Ernest Callenbach was one of the first influential ecological utopian novels.Archived aGhostarchive

and th

Wayback Machine

Richard Grove's book '' Green Imperialism: Colonial Expansion, Tropical Island Edens and the Origins of Environmentalism 1600–1860'' from 1995 suggested the roots of ecological utopian thinking. Grove's book sees early environmentalism as a result of the impact of utopian tropical islands on European data-driven scientists. The works on ecological eutopia perceive a widening gap between the modern Western way of living that destroys nature and a more traditional way of living before industrialization. Ecological utopias may advocate a society that is more sustainable. According to the Dutch philosopher Marius de Geus, ecological utopias could be inspirational sources for movements involving

green politics

Green politics, or ecopolitics, is a political ideology that aims to foster an ecologically sustainable society often, but not always, rooted in environmentalism, nonviolence, social justice and grassroots democracy.#Wal10, Wall 2010. p. 12-13. ...

.

Feminism

Utopias have been used to explore the ramifications of genders being either a societal construct or a biologically "hard-wired" imperative or some mix of the two. Socialist and economic utopias have tended to take the "woman question" seriously and often to offer some form of equality between the sexes as part and parcel of their vision, whether this be by addressing misogyny, reorganizing society along separatist lines, creating a certain kind of androgynous equality that ignores gender or in some other manner. For example, Edward Bellamy's '' Looking Backward'' (1887) responded, progressively for his day, to the contemporary women's suffrage and women's rights movements. Bellamy supported these movements by incorporating the equality of women and men into his utopian world's structure, albeit by consigning women to a separate sphere of light industrial activity (due to women's lesser physical strength) and making various exceptions for them in order to make room for (and to praise) motherhood. One of the earlier feminist utopias that imagines complete separatism isCharlotte Perkins Gilman

Charlotte Anna Perkins Gilman (; née Perkins; July 3, 1860 – August 17, 1935), also known by her first married name Charlotte Perkins Stetson, was an American humanist, novelist, writer, lecturer, early sociologist, advocate for social reform ...

's '' Herland'' (1915).

In science fiction and technological speculation, gender can be challenged on the biological as well as the social level. Marge Piercy's '' Woman on the Edge of Time'' portrays equality between the genders and complete equality in sexuality (regardless of the gender of the lovers). Birth-giving, often felt as the divider that cannot be avoided in discussions of women's rights and roles, has been shifted onto elaborate biological machinery that functions to offer an enriched embryonic experience. When a child is born, it spends most of its time in the children's ward with peers. Three "mothers" per child are the norm and they are chosen in a gender neutral way (men as well as women may become "mothers") on the basis of their experience and ability. Technological advances also make possible the freeing of women from childbearing in Shulamith Firestone's '' The Dialectic of Sex''. The fictional aliens in Mary Gentle's '' Golden Witchbreed'' start out as gender-neutral children and do not develop into men and women until puberty and gender has no bearing on social roles. In contrast, Doris Lessing's '' The Marriages Between Zones Three, Four and Five'' (1980) suggests that men's and women's values are inherent to the sexes and cannot be changed, making a compromise between them essential. In ''My Own Utopia'' (1961) by Elizabeth Mann Borghese, gender exists but is dependent upon age rather than sex – genderless children mature into women, some of whom eventually become men. " William Marston's Wonder Woman

Wonder Woman is a superheroine who appears in American comic books published by DC Comics. The character first appeared in ''All Star Comics'' Introducing Wonder Woman, #8, published October 21, 1941, with her first feature in ''Sensation Comic ...

comics of the 1940s featured Paradise Island, also known as Themyscira, a matriarchal all-female community of peace, loving submission, bondage and giant space kangaroos."

Utopian single-gender worlds or single-sex societies have long been one of the primary ways to explore implications of gender and gender-differences. In speculative fiction, female-only worlds have been imagined to come about by the action of disease that wipes out men, along with the development of technological or mystical method that allow female parthenogenic reproduction

Reproduction (or procreation or breeding) is the biological process by which new individual organisms – "offspring" – are produced from their "parent" or parents. There are two forms of reproduction: Asexual reproduction, asexual and Sexual ...

. Charlotte Perkins Gilman's 1915 novel approaches this type of separate society. Many feminist utopias pondering separatism were written in the 1970s, as a response to the Lesbian separatist movement;Attebery, p. 13. Gaétan Brulotte & John Phillips,''Encyclopedia of Erotic Literature'', "Science Fiction and Fantasy", CRC Press, 2006, p. 1189, examples include Joanna Russ

Joanna Russ (February 22, 1937 – April 29, 2011) was an American writer, academic and feminist. She is the author of a number of works of science fiction, fantasy and feminist literary criticism such as '' How to Suppress Women's Writing'', as ...

's '' The Female Man'' and Suzy McKee Charnas's '' Walk to the End of the World'' and '' Motherlines''.Martha A. Bartter, ''The Utopian Fantastic'', "Momutes", Robin Anne Reid, p. 101 Utopias imagined by male authors have often included equality between sexes, rather than separation, although as noted Bellamy's strategy includes a certain amount of "separate but equal".Martha A. Bartter, ''The Utopian Fantastic'', "Momutes", Robin Anne Reid, p. 102 The use of female-only worlds allows the exploration of female independence and freedom from patriarchy

Patriarchy is a social system in which positions of authority are primarily held by men. The term ''patriarchy'' is used both in anthropology to describe a family or clan controlled by the father or eldest male or group of males, and in fem ...

. The societies may be lesbian, such as '' Daughters of a Coral Dawn'' by Katherine V. Forrest or not, and may not be sexual at all – a famous early sexless example being '' Herland'' (1915) by Charlotte Perkins Gilman

Charlotte Anna Perkins Gilman (; née Perkins; July 3, 1860 – August 17, 1935), also known by her first married name Charlotte Perkins Stetson, was an American humanist, novelist, writer, lecturer, early sociologist, advocate for social reform ...

. Charlene Ball writes in ''Women's Studies Encyclopedia'' that use of speculative fiction to explore gender roles in future societies has been more common in the United States compared to Europe and elsewhere, although such efforts as Gerd Brantenberg's ''Egalia's Daughters'' and Christa Wolf's portrayal of the land of Colchis in her ''Medea: Voices ''are certainly as influential and famous as any of the American feminist utopias.

Urban Design

Walter Elias Disney's original EPCOT (concept) (Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow), Paolo Soleri's Arcosanti, Everyday Utopias by Davina Cooper, and Saudi Prince Mohammed bin Salman's Neom are examples of Utopian city design.Critical Utopia

Critical utopia is a theory conceptualised by literary theorist Tom Moylan. In contrast with utopianism, critical utopia rejects utopia. The idea is highlyself-referential

Self-reference is a concept that involves referring to oneself or one's own attributes, characteristics, or actions. It can occur in language, logic, mathematics, philosophy, and other fields.

In natural language, natural or formal languages, ...

and uses the idea of utopia to advance society while critiquing it simultaneously. A problem with utopianism is identified: it has limitations since the imagined utopia is significantly distant from current society. Utopia also fails to acknowledge the differences between people that result in differences in experience. Moylan explains that " ritical utopiasultimately refer to something other than a predictable alternative paradigm, for at their core they identify self-critical utopian discourse itself as a process that can tear apart the dominant ideological web. Here, then, critical utopian discourse becomes a seditious expression of social change and popular sovereignty carried on in a permanently open process of envisioning what is not yet."

Cultural legacy

By one count, more than 400 utopian works in the English language were published prior to the year 1900, and over a thousand during the 20th century. Several plays and films also present utopian visions. The 1937 film '' Lost Horizon'', the 1954 nudist film ''Garden of Eden

In Abrahamic religions, the Garden of Eden (; ; ) or Garden of God ( and ), also called the Terrestrial Paradise, is the biblical paradise described in Genesis 2–3 and Ezekiel 28 and 31..

The location of Eden is described in the Book of Ge ...

'', and the 1984 film '' The Other Side of the Horizon'' portray utopian communities. '' They Came to a City'', a 1944 British science fiction film, was adapted from the 1943 play of the same title written by J. B. Priestley. It portrays the arrival of nine Britons in a mysterious city that to some is a utopia; to others not so much. The 2024 Francis Ford Coppolla film ''Megalopolis

A megalopolis () or a supercity, also called a megaregion, is a group of metropolitan areas which are perceived as a continuous urban area through common systems of transport, economy, resources, ecology, and so on. They are integrated enough ...

'' considers the obstacles faced by an architect who wants to found a utopian community in an alternate future U.S.A. under a corrupt emperor.

See also

* List of utopian literature * New world order (Baháʼí) * Nutopia * Utopia (disambiguation) *'' Utopia for Realists'' *Utopian and dystopian fiction

Utopian and dystopian fiction are subgenres of speculative fiction that explore extreme forms of social and political structures. Utopian fiction portrays a setting that agrees with the author's ethos, having various attributes of another reality ...

* List of intentional communities

* Utopian films

Notes

; Bundled referencesReferences

Living in the Future: Utopianism and the Long Civil Rights Movement

(2022) by Victoria Wolcott * ''Utopia: Music album'' (2023), by Travis Scott. * ''Utopia: The History of an Idea'' (2020), by Gregory Claeys. London: Thames & Hudson. *''Two Kinds of Utopia'', (1912) by

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

.

*''Development of Socialism from Utopia to Science'' (1870?) by Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ;"Engels"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.Karl Mannheim, translated by Louis Wirth and Edward Shils. New York, Harcourt, Brace. See original, ''Ideologie Und Utopie'', Bonn: Cohen. * '' History and Utopia'' (1960), by Emil Cioran. *''Utopian Thought in the Western World'' (1979), by Frank E. Manuel & Fritzie Manuel. Oxford: Blackwell. *''California's Utopian Colonies'' (1983), by Robert V. Hine. University of California Press. *'' The Principle of Hope'' (1986), by Ernst Bloch. See original, 1937–41, ''Das Prinzip Hoffnung'' *''Demand the Impossible: Science Fiction and the Utopian Imagination'' (1986) by Tom Moylan. London: Methuen, 1986. *''Utopia and Anti-utopia in Modern Times'' (1987), by Krishnan Kumar. Oxford: Blackwell. *''The Concept of Utopia'' (1990), by Ruth Levitas. London: Allan. *''Utopianism'' (1991), by Krishnan Kumar. Milton Keynes: Open University Press. *''La storia delle utopie'' (1996), by Massimo Baldini. Roma: Armando. *''The Utopia Reader'' (1999), edited by Gregory Claeys and Lyman Tower Sargent. New York: New York University Press. *''Spirit of Utopia'' (2000), by Ernst Bloch. See original, ''Geist Der Utopie'', 1923. *''Archaeologies of the Future: The Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions'' (2005) by

Existential Utopia: New Perspectives on Utopian Thought

' (2011), edited by Patricia Vieira and Michael Marder. London & New York: Continuum. *"Galt's Gulch: Ayn Rand's Utopian Delusion" (2012), by Alan Clardy. ''Utopian Studies'' 23, 238–262. *''The Nationality of Utopia: H. G. Wells, England, and the World State'' (2020), by Maxim Shadurski. New York and London: Routledge. *

Utopia as a World Model: The Boundaries and Borderlands of a Literary Phenomenon

' (2016), by Maxim Shadurski. Siedlce: IKR L. . *''An Ecotopian Lexicon'' (2019), edited by Matthew Schneider-Mayerson and Brent Ryan Bellamy. University of Minnesota Press. .

Utopia – The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition, 2001

Intentional Communities Directory

History of 15 Finnish

utopian settlements in Africa, the Americas, Asia, Australia and Europe.

– a learning resource from the

Review of Ehud Ben ZVI, Ed. (2006). Utopia and Dystopia in Prophetic Literature. Helsinki: The Finnish Exegetical Society.

A collection of articles on the issue of utopia and dystopia.

The story of Utopias

Mumford, Lewis

North America

Europe

''Utopian Studies''

academic journal * {{Authority control 16th-century neologisms Science fiction themes Speculative fiction Words originating in fiction

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.Karl Mannheim, translated by Louis Wirth and Edward Shils. New York, Harcourt, Brace. See original, ''Ideologie Und Utopie'', Bonn: Cohen. * '' History and Utopia'' (1960), by Emil Cioran. *''Utopian Thought in the Western World'' (1979), by Frank E. Manuel & Fritzie Manuel. Oxford: Blackwell. *''California's Utopian Colonies'' (1983), by Robert V. Hine. University of California Press. *'' The Principle of Hope'' (1986), by Ernst Bloch. See original, 1937–41, ''Das Prinzip Hoffnung'' *''Demand the Impossible: Science Fiction and the Utopian Imagination'' (1986) by Tom Moylan. London: Methuen, 1986. *''Utopia and Anti-utopia in Modern Times'' (1987), by Krishnan Kumar. Oxford: Blackwell. *''The Concept of Utopia'' (1990), by Ruth Levitas. London: Allan. *''Utopianism'' (1991), by Krishnan Kumar. Milton Keynes: Open University Press. *''La storia delle utopie'' (1996), by Massimo Baldini. Roma: Armando. *''The Utopia Reader'' (1999), edited by Gregory Claeys and Lyman Tower Sargent. New York: New York University Press. *''Spirit of Utopia'' (2000), by Ernst Bloch. See original, ''Geist Der Utopie'', 1923. *''Archaeologies of the Future: The Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions'' (2005) by

Fredric Jameson

Fredric Ruff Jameson (April 14, 1934 – September 22, 2024) was an American literary critic, philosopher and Marxist political theorist. He was best known for his analysis of contemporary cultural trends, particularly his analysis of postmode ...

. London: Verso.

*''Utopianism: A Very Short Introduction'' (2010), by Lyman Tower Sargent. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

*''Defined by a Hollow: Essays on Utopia, Science Fiction and Political Epistemology'' (2010) by Darko Suvin. Frankfurt am Main, Oxford and Bern: Peter Lang.

*Existential Utopia: New Perspectives on Utopian Thought

' (2011), edited by Patricia Vieira and Michael Marder. London & New York: Continuum. *"Galt's Gulch: Ayn Rand's Utopian Delusion" (2012), by Alan Clardy. ''Utopian Studies'' 23, 238–262. *''The Nationality of Utopia: H. G. Wells, England, and the World State'' (2020), by Maxim Shadurski. New York and London: Routledge. *

Utopia as a World Model: The Boundaries and Borderlands of a Literary Phenomenon

' (2016), by Maxim Shadurski. Siedlce: IKR L. . *''An Ecotopian Lexicon'' (2019), edited by Matthew Schneider-Mayerson and Brent Ryan Bellamy. University of Minnesota Press. .

External links

*Utopia – The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition, 2001

Intentional Communities Directory

History of 15 Finnish

utopian settlements in Africa, the Americas, Asia, Australia and Europe.

– a learning resource from the

British Library

The British Library is the national library of the United Kingdom. Based in London, it is one of the largest libraries in the world, with an estimated collection of between 170 and 200 million items from multiple countries. As a legal deposit li ...

Review of Ehud Ben ZVI, Ed. (2006). Utopia and Dystopia in Prophetic Literature. Helsinki: The Finnish Exegetical Society.

A collection of articles on the issue of utopia and dystopia.

The story of Utopias

Mumford, Lewis

North America

Europe

''Utopian Studies''

academic journal * {{Authority control 16th-century neologisms Science fiction themes Speculative fiction Words originating in fiction