United Ireland (), also referred to as Irish reunification

or a ''New Ireland'', is the proposition that all of

Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

should be a single

sovereign state

A sovereign state is a State (polity), state that has the highest authority over a territory. It is commonly understood that Sovereignty#Sovereignty and independence, a sovereign state is independent. When referring to a specific polity, the ter ...

. At present, the island is divided politically: the sovereign state of Ireland (legally described also as the

Republic of Ireland

Ireland ( ), also known as the Republic of Ireland (), is a country in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe consisting of 26 of the 32 Counties of Ireland, counties of the island of Ireland, with a population of about 5.4 million. ...

) has jurisdiction over the majority of Ireland, while

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ; ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, part of the United Kingdom in the north-east of the island of Ireland. It has been #Descriptions, variously described as a country, province or region. Northern Ireland shares Repub ...

, which lies entirely within (but consists of only 6 of 9 counties of) the

Irish province of

Ulster

Ulster (; or ; or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional or historic provinces of Ireland, Irish provinces. It is made up of nine Counties of Ireland, counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kingdom); t ...

, is part of the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

. Achieving a united Ireland is a central tenet of

Irish nationalism

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cult ...

and

Republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology that encompasses a range of ideas from civic virtue, political participation, harms of corruption, positives of mixed constitution, rule of law, and others. Historically, it emphasizes the idea of self ...

, particularly of both mainstream and

dissident republican

Dissident republicans () are Irish republicans who do not support the Northern Ireland peace process. The peace agreements followed a 30-year conflict known as the Troubles, in which over 3,500 people were killed and 47,500 injured, and in whi ...

political and paramilitary organisations.

Unionists support Northern Ireland remaining part of the United Kingdom and oppose Irish unification.

Ireland has been

partitioned since May 1921, when the implementation of the

Government of Ireland Act 1920

The Government of Ireland Act 1920 ( 10 & 11 Geo. 5. c. 67) was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. The Act's long title was "An Act to provide for the better government of Ireland"; it is also known as the Fourth Home Rule Bi ...

created the states of Southern Ireland and Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom, with the former becoming independent, and the other petitioning to remain a part of the UK. The

Anglo-Irish Treaty

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty (), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain an ...

, which led to the establishment in December 1922 of a

dominion

A dominion was any of several largely self-governance, self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of self-governing colony, colon ...

called the

Irish Free State

The Irish Free State (6 December 192229 December 1937), also known by its Irish-language, Irish name ( , ), was a State (polity), state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-ye ...

, recognised partition, but this was opposed by anti-Treaty republicans. When the anti-Treaty

Fianna Fáil

Fianna Fáil ( ; ; meaning "Soldiers of Destiny" or "Warriors of Fál"), officially Fianna Fáil – The Republican Party (), is a centre to centre-right political party in Ireland.

Founded as a republican party in 1926 by Éamon de ...

party came to power in the 1930s, it adopted a

new constitution which claimed sovereignty over the entire island. The

Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) is a name used by various Resistance movement, resistance organisations in Ireland throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Organisations by this name have been dominantly Catholic and dedicated to anti-imperiali ...

(IRA) had a united Ireland as its goal during the conflict with British security forces and

loyalist paramilitaries

Ulster loyalism is a strand of Ulster unionism associated with working class Ulster Protestants in Northern Ireland. Like other unionists, loyalists support the continued existence of Northern Ireland (and formerly all of Ireland) within the Un ...

from the 1960s to the 1990s known as

The Troubles

The Troubles () were an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted for about 30 years from the late 1960s to 1998. Also known internationally as the Northern Ireland conflict, it began in the late 1960s and is usually deemed t ...

. The

Good Friday Agreement

The Good Friday Agreement (GFA) or Belfast Agreement ( or ; or ) is a pair of agreements signed on 10 April (Good Friday) 1998 that ended most of the violence of the Troubles, an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland since the la ...

signed in 1998, which ended the conflict, acknowledged the legitimacy of the desire for a united Ireland, while declaring that it could be achieved only with the consent of a majority of the people of both jurisdictions on the island, and providing a mechanism for ascertaining this in certain circumstances.

In 2016, following the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

's decision to leave the

European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are Geography of the European Union, located primarily in Europe. The u ...

with

Brexit

Brexit (, a portmanteau of "Britain" and "Exit") was the Withdrawal from the European Union, withdrawal of the United Kingdom (UK) from the European Union (EU).

Brexit officially took place at 23:00 GMT on 31 January 2020 (00:00 1 February ...

,

Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( ; ; ) is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active in both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The History of Sinn Féin, original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Griffit ...

called for a referendum on Irish reunification. The decision had increased the perceived likelihood of a united Ireland, in order to avoid the possible requirement for a hard border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, though the imposition of a hard border has not, as yet, eventuated. Fine Gael

Taoiseach

The Taoiseach (, ) is the head of government or prime minister of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. The office is appointed by the President of Ireland upon nomination by Dáil Éireann (the lower house of the Oireachtas, Ireland's national legisl ...

Enda Kenny

Enda Kenny (born 24 April 1951) is an Irish former Fine Gael politician who served as Taoiseach from 2011 to 2017, Leader of Fine Gael from 2002 to 2017, Minister for Defence (Ireland), Minister for Defence from May to July 2014 and 2016 to 201 ...

successfully negotiated that in the event of reunification, Northern Ireland will become part of the EU, just as

East Germany

East Germany, officially known as the German Democratic Republic (GDR), was a country in Central Europe from Foundation of East Germany, its formation on 7 October 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with West Germany (FRG) on ...

was permitted to join

the EU's predecessor institutions by

reuniting with the rest of

Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

after the

fall of the Berlin Wall

The fall of the Berlin Wall (, ) on 9 November in German history, 9 November 1989, during the Peaceful Revolution, marked the beginning of the destruction of the Berlin Wall and the figurative Iron Curtain, as East Berlin transit restrictions we ...

.

The majority of

Ulster Protestants

Ulster Protestants are an ethnoreligious group in the Provinces of Ireland, Irish province of Ulster, where they make up about 43.5% of the population. Most Ulster Protestantism in Ireland, Protestants are descendants of settlers who arrived fr ...

, almost half the population of Northern Ireland, favour continued union with

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

, and have done so historically. Four of the six counties have

Irish Catholic

Irish Catholics () are an ethnoreligious group native to Ireland, defined by their adherence to Catholic Christianity and their shared Irish ethnic, linguistic, and cultural heritage.The term distinguishes Catholics of Irish descent, particul ...

majorities, and majorities voting for Irish nationalist parties, and Catholics have become the plurality in Northern Ireland as of 2021. The religious denominations of the citizens of Northern Ireland are only a guide to likely political preferences, as there are both Protestants who favour a united Ireland, and Catholics who oppose it.

Two surveys in 2011 identified a significant number of Catholics who favoured the continuation of the union without identifying themselves as unionists or British.

In 2024, a survey showed supporters of the Union equated to a plurality at 48.6%, rather than a majority in Northern Ireland for the first time, while 33.76% supported Irish unity.

Legal basis for future change

Article 3.1 of the

Constitution of Ireland

The Constitution of Ireland (, ) is the constitution, fundamental law of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It asserts the national sovereignty of the Irish people. It guarantees certain fundamental rights, along with a popularly elected non-executi ...

"recognises that a united Ireland shall be brought about only by peaceful means with the consent of a majority of the people, democratically expressed, in both jurisdictions in the island". This provision was introduced in 1999 after implementation of the

Good Friday Agreement

The Good Friday Agreement (GFA) or Belfast Agreement ( or ; or ) is a pair of agreements signed on 10 April (Good Friday) 1998 that ended most of the violence of the Troubles, an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland since the la ...

, as part of replacing the old

Articles 2 and 3, which had laid a direct claim to the whole island as the national territory.

The

Northern Ireland Act 1998

__NOTOC__

The Northern Ireland Act 1998 (c. 47) is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which allowed Westminster to devolve power to Northern Ireland, after decades of direct rule.

It renamed the New Northern Ireland Assembly, establi ...

, a statute of the

Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, and may also legislate for the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace ...

, provides that Northern Ireland will remain within the United Kingdom unless a majority of the people of Northern Ireland vote to form part of a united Ireland. It specifies that the

Secretary of State for Northern Ireland

The secretary of state for Northern Ireland (; ), also referred to as Northern Ireland Secretary or SoSNI, is a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, with overall responsibility for the Northern Ireland Office. The offi ...

"shall exercise the power

o hold a referendum

O, or o, is the fifteenth letter and the fourth vowel letter of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''o'' (pronounced ), p ...

if at any time it appears likely to him that a majority of those voting would express a wish that Northern Ireland should cease to be part of the United Kingdom and form part of a united Ireland". Such referendums may not take place within seven years of each other.

The Northern Ireland Act 1998 supersedes previous similar legislative provisions. The

Northern Ireland Constitution Act 1973

The Northern Ireland Constitution Act 1973 (c. 36) is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which received royal assent on 18 July 1973. The act abolished the suspended Parliament of Northern Ireland and the post of Governor and mad ...

also provided that Northern Ireland remained part of the United Kingdom unless a majority voted otherwise in a referendum, while under the

Ireland Act 1949

The Ireland Act 1949 ( 12, 13 & 14 Geo. 6. c. 41) is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom intended to deal with the consequences of the Republic of Ireland Act 1948 as passed by the Irish parliament, the Oireachtas.

Background

Follo ...

the consent of the

Parliament of Northern Ireland

The Parliament of Northern Ireland was the home rule legislature of Northern Ireland, created under the Government of Ireland Act 1920, which sat from 7 June 1921 to 30 March 1972, when it was suspended because of its inability to restore ord ...

was needed for a united Ireland. In 1985, the

Anglo-Irish Agreement

The Anglo-Irish Agreement was a 1985 treaty between the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland which aimed to help bring an end to the Troubles in Northern Ireland. The treaty gave the Irish government an advisory role in Northern Irelan ...

affirmed, while providing for devolved government in Northern Ireland, and an advisory role for the Republic of Ireland government, that any change in the status of Northern Ireland would only come about with the consent of a majority of the people of Northern Ireland.

History

Home Rule, resistance and the Easter Rising

The

Kingdom of Ireland

The Kingdom of Ireland (; , ) was a dependent territory of Kingdom of England, England and then of Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain from 1542 to the end of 1800. It was ruled by the monarchs of England and then List of British monarchs ...

as a whole had become part of the

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the union of the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland into one sovereign state, established by the Acts of Union 1800, Acts of Union in 1801. It continued in this form until ...

under the

Acts of Union 1800

The Acts of Union 1800 were parallel acts of the Parliament of Great Britain and the Parliament of Ireland which united the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland (previously in personal union) to create the United Kingdom of G ...

. From the 1870s, support for some form of an elected parliament in Dublin grew. In 1870,

Isaac Butt

Isaac Butt (6 September 1813 – 5 May 1879) was an Irish barrister, editor, politician, Member of Parliament in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, economist and the founder and first leader of a number of Irish nationalist par ...

, who was a Protestant, formed the

Home Government Association

The Home Government Association was a pressure group launched by Isaac Butt in support of home rule for Ireland at a meeting in Bilton's Hotel, Dublin, on 19 May 1870.

The meeting was attended or supported by sixty-one people of different polit ...

, which became the

Home Rule League

The Home Rule League (1873–1882), sometimes called the Home Rule Party, was an Irish political party which campaigned for home rule for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, until it was replaced by the Irish Parliam ...

.

Charles Stewart Parnell

Charles Stewart Parnell (27 June 1846 – 6 October 1891) was an Irish nationalist politician who served as a Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of Parliament (MP) in the United Kingdom from 1875 to 1891, Leader of the Home Rule Leag ...

, also a Protestant, became leader in 1880, and the organisation became the

Irish National League

The Irish National League (INL) was a nationalist political party in Ireland. It was founded on 17 October 1882 by Charles Stewart Parnell as the successor to the Irish National Land League after this was suppressed. Whereas the Land League ...

in 1882. Despite the religion of its early leaders, its support was strongly associated with Irish Catholics. In 1886, Parnell formed a parliamentary alliance with

Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world.

The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left. For example, while the political systems ...

Prime Minister

William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British politican, starting as Conservative MP for Newark and later becoming the leader of the Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Party.

In a career lasting over 60 years, he ...

and secured the introduction of the

First Home Rule Bill

The Government of Ireland Bill 1886, commonly known as the First Home Rule Bill, was the first major attempt made by a British government to enact a law creating home rule for part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was intr ...

. This was opposed by the

Conservative Party and led to a split in the Liberal Party, the

Liberal Unionist Party

The Liberal Unionist Party was a British political party that was formed in 1886 by a faction that broke away from the Liberal Party. Led by Lord Hartington (later the Duke of Devonshire) and Joseph Chamberlain, the party established a political ...

. Opposition in Ireland was concentrated in the heavily Protestant counties in Ulster. The difference in religious background was a legacy of the

Ulster Plantation

The Plantation of Ulster (; Ulster Scots: ) was the organised colonisation (''plantation'') of Ulstera province of Irelandby people from Great Britain during the reign of King James VI and I.

Small privately funded plantations by wealthy lan ...

in the early seventeenth century. In 1893, the

Second Home Rule Bill

The Government of Ireland Bill 1893 (known generally as the Second Home Rule Bill) was the second attempt made by Liberal Party leader William Ewart Gladstone, as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, to enact a system of home rule for Ireland. ...

passed in the House of Commons, but was defeated in the House of Lords, where the Conservatives dominated. A Third Home Rule Bill was introduced in 1912, and in September 1912, just under half a million men and women signed the

Ulster Covenant

Ulster's Solemn League and Covenant, commonly known as the Ulster Covenant, was signed by nearly 500,000 people on and before 28 September 1912, in protest against the Third Home Rule Bill introduced by the British Government in the same year.

...

to swear they would resist its application in Ulster. The

Ulster Volunteer Force

The Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) is an Ulster loyalism, Ulster loyalist paramilitary group based in Northern Ireland. Formed in 1965, it first emerged in 1966. Its first leader was Gusty Spence, a former Royal Ulster Rifles soldier from North ...

were formed in 1913 as a militia to resist Home Rule.

The

Government of Ireland Act 1914

The Government of Ireland Act 1914 ( 4 & 5 Geo. 5. c. 90), also known as the Home Rule Act, and before enactment as the Third Home Rule Bill, was an Act passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom intended to provide home rule (self-gover ...

(previously known as the Third Home Rule Bill) provided for a unitary devolved Irish Parliament, a culmination of several decades of work from the

Irish Parliamentary Party

The Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP; commonly called the Irish Party or the Home Rule Party) was formed in 1874 by Isaac Butt, the leader of the Nationalist Party, replacing the Home Rule League, as official parliamentary party for Irish nati ...

. It was signed into law in September 1914 in the midst of the

Home Rule Crisis

The Home Rule Crisis was a political and military crisis in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland that followed the introduction of the Government of Ireland Act 1914, Third Home Rule Bill in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom ...

and at the outbreak of the

First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. On the same day, the

Suspensory Act 1914

The Suspensory Act 1914 (4 & 5 Geo. 5 c. 88) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which suspended the coming into force of two other Acts: the Welsh Church Act 1914 (for the disestablishment of the Church of England in Wales), ...

suspended its actual operation.

In 1916, a group of revolutionaries led by the

Irish Republican Brotherhood

The Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB; ) was a secret oath-bound fraternal organisation dedicated to the establishment of an "independent democratic republic" in Ireland between 1858 and 1924.McGee, p. 15. Its counterpart in the United States ...

launched the

Easter Rising

The Easter Rising (), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the aim of establishing an ind ...

, during which they issued a

Proclamation of the Irish Republic

The Proclamation of the Republic (), also known as the 1916 Proclamation or the Easter Proclamation, was a document issued by the Irish Volunteers and the Irish Citizen Army during the Easter Rising in Ireland, which began on 24 April 1916. ...

. The rebellion was not successful and sixteen of the leaders were executed. The small separatist party

Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( ; ; ) is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active in both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The History of Sinn Féin, original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Griffit ...

became associated with the Rising in its aftermath as several of those involved in it were party members.

The

Irish Convention

The Irish Convention was an assembly which sat in Dublin, Ireland from July 1917 until March 1918 to address the '' Irish question'' and other constitutional problems relating to an early enactment of self-government for Ireland, to debate it ...

held between 1917 and 1918 sought to reach agreement on manner in which Home Rule would be implemented after the war. All Irish parties were invited, but Sinn Féin boycotted the proceedings. By the end of the First World War, a number of moderate unionists came to support Home Rule, believing that it was the only way to keep a united Ireland in the United Kingdom. The

Irish Dominion League

The Irish Dominion League was an Irish political party and movement in Britain and Ireland which advocated Dominion status for Ireland within the British Empire, and opposed partition of Ireland into separate southern and northern jurisdictions ...

opposed partition of Ireland into separate southern and northern jurisdictions, while arguing that the whole of Ireland should be granted

dominion

A dominion was any of several largely self-governance, self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of self-governing colony, colon ...

status with the British Empire.

At the

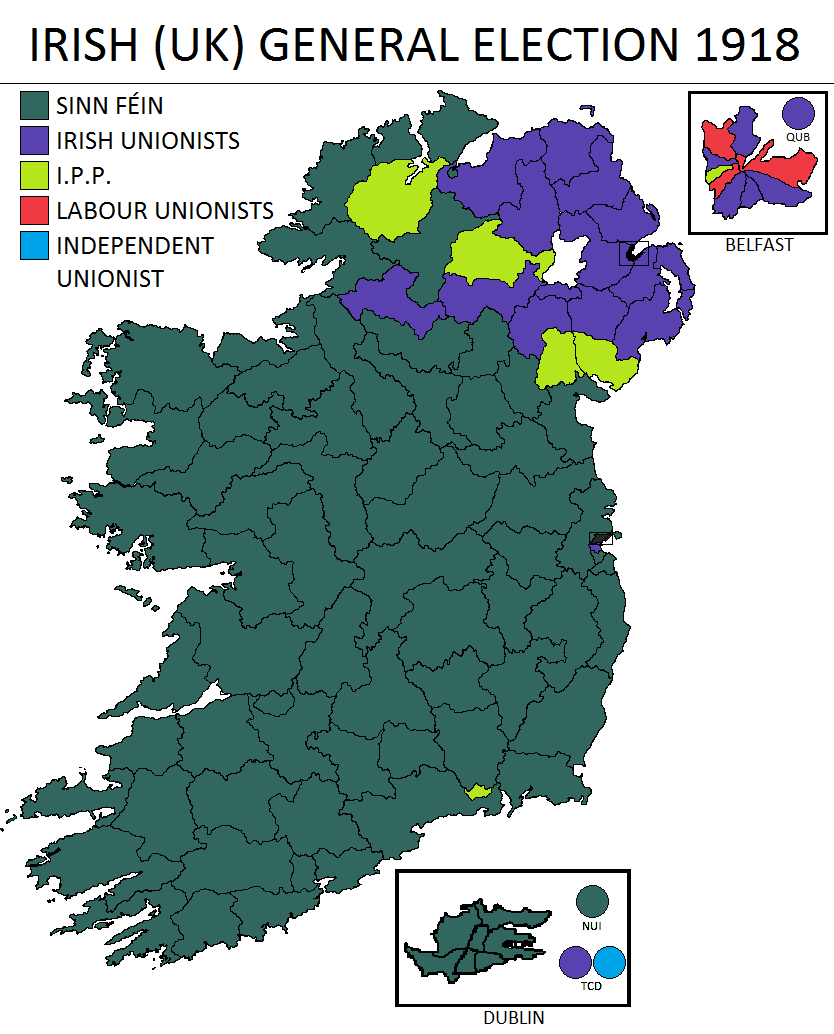

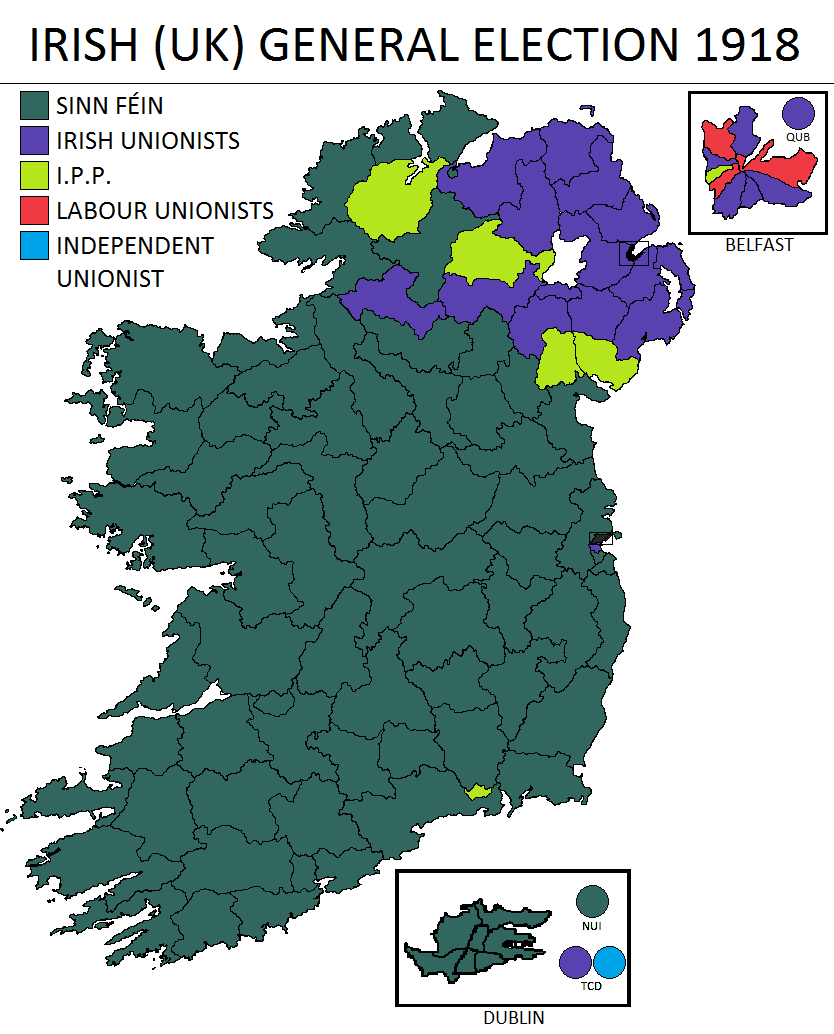

1918 election Sinn Féin won 73 of the 105 seats; however, there was a strong regional divide, with the

Ulster Unionist Party

The Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) is a Unionism in Ireland, unionist political party in Northern Ireland. The party was founded as the Ulster Unionist Council in 1905, emerging from the Irish Unionist Alliance in Ulster. Under Edward Carson, it l ...

(UUP) winning 23 of the 38 seats in Ulster. Sinn Féin had run on a

manifesto

A manifesto is a written declaration of the intentions, motives, or views of the issuer, be it an individual, group, political party, or government. A manifesto can accept a previously published opinion or public consensus, but many prominent ...

of

abstaining

Abstention is a term in election procedure for when a participant in a vote either does not go to vote (on election day) or, in parliamentary procedure, is present during the vote but does not cast a ballot. Abstention must be contrasted with ...

from the

United Kingdom House of Commons

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the upper house, the House of Lords, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. The House of Commons is an elected body consisting of 650 memb ...

, and from 1919 met in Dublin as

Dáil Éireann

Dáil Éireann ( ; , ) is the lower house and principal chamber of the Oireachtas, which also includes the president of Ireland and a senate called Seanad Éireann.Article 15.1.2° of the Constitution of Ireland reads: "The Oireachtas shall co ...

. At its first meeting, the Dáil adopted the

Declaration of Independence of the Irish Republic, a claim which it made in respect of the entire island. Supporters of this Declaration fought in the

Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence (), also known as the Anglo-Irish War, was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (1919–1922), Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and Unite ...

.

Two jurisdictions

During this period, the

Government of Ireland Act 1920

The Government of Ireland Act 1920 ( 10 & 11 Geo. 5. c. 67) was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. The Act's long title was "An Act to provide for the better government of Ireland"; it is also known as the Fourth Home Rule Bi ...

repealed the previous 1914 Act, and provided for two separate devolved parliaments in Ireland. It defined

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ; ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, part of the United Kingdom in the north-east of the island of Ireland. It has been #Descriptions, variously described as a country, province or region. Northern Ireland shares Repub ...

as "the parliamentary counties of Antrim, Armagh, Down, Fermanagh, Londonderry and Tyrone, and the parliamentary boroughs of Belfast and Londonderry" and

Southern Ireland "so much of Ireland as is not comprised within the said parliamentary counties and boroughs". Section 3 of this Act provided that the parliaments may be united by identical acts of parliament:

Sinn Féin did not recognise this act, treating elections to the respective parliaments as a single election to the

Second Dáil

The second (symbol: s) is a unit of time derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes, and finally to 60 seconds each (24 × 60 × 60 = 86400). The current and formal definition in the International System of Un ...

. While the

Parliament of Northern Ireland

The Parliament of Northern Ireland was the home rule legislature of Northern Ireland, created under the Government of Ireland Act 1920, which sat from 7 June 1921 to 30 March 1972, when it was suspended because of its inability to restore ord ...

sat from 1921 to 1972, the

Parliament of Southern Ireland

The Parliament of Southern Ireland was a Home Rule legislature established by the British Government during the Irish War of Independence under the Government of Ireland Act 1920. It was designed to legislate for Southern Ireland,Order in Cou ...

was suspended after its first meeting was boycotted by the Sinn Féin members, who comprised 124 of its 128 MPs.

A truce in the War of Independence was called in July 1921, followed by negotiations in London between the government of the United Kingdom and a Sinn Féin delegation. On 6 December 1921, they signed the

Anglo-Irish Treaty

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty (), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain an ...

, which led to the establishment of the

Irish Free State

The Irish Free State (6 December 192229 December 1937), also known by its Irish-language, Irish name ( , ), was a State (polity), state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-ye ...

the following year, a

dominion

A dominion was any of several largely self-governance, self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of self-governing colony, colon ...

within the

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

.

With respect to Northern Ireland, Articles 11 and 12 of the Treaty made special provision for it including as follows:

The

Prime Minister of Northern Ireland

The prime minister of Northern Ireland was the head of the Government of Northern Ireland (1921–1972), Government of Northern Ireland between 1921 and 1972. No such office was provided for in the Government of Ireland Act 1920; however, the L ...

,

Sir James Craig, speaking in the

House of Commons of Northern Ireland

The House of Commons of Northern Ireland was the lower house of the Parliament of Northern Ireland created under the Government of Ireland Act 1920. The upper house in the bicameral parliament was called the Senate. It was abolished with the ...

in October 1922 said that "when 6 December

922

__NOTOC__

Year 922 ( CMXXII) was a common year starting on Tuesday of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Byzantine Empire

* Summer – Battle of Constantinople: Emperor Romanos I sends Byzantine troops to repel another Bulgaria ...

is passed the month begins in which we will have to make the choice either to vote out or remain within the Free State". He said it was important that that choice be made as soon as possible after 6 December 1922 "in order that it may not go forth to the world that we had the slightest hesitation". On 7 December 1922, the day after the establishment of the Irish Free State, the Houses of the Parliament of Northern Ireland resolved to make the following address to the King so as to exercise the rights conferred on Northern Ireland under Article 12 of the Treaty:

The King received it the following day. These steps cemented Northern Ireland's legal separation from the Irish Free State.

In

Irish republican legitimist theory, the Treaty was illegitimate and could not be approved. According to this theory, the Second Dáil did not dissolve and members of the Republican Government remained as the legitimate government of the Irish Republic declared in 1919. Adherents to this theory rejected the legitimacy of both the Irish Free State and Northern Ireland.

The report of

Boundary Commission in 1925 established under the Treaty did not lead to any alteration in the

border

Borders are generally defined as geography, geographical boundaries, imposed either by features such as oceans and terrain, or by polity, political entities such as governments, sovereign states, federated states, and other administrative divisio ...

.

Within Northern Ireland, the

Nationalist Party was an organisational successor to the

Home Rule Movement

Home rule is the government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governanc ...

, and advocated the end of partition. It had a continuous presence in the Northern Ireland Parliament from 1921 to 1972, but was in permanent opposition to the UUP government.

A new

Constitution of Ireland

The Constitution of Ireland (, ) is the constitution, fundamental law of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It asserts the national sovereignty of the Irish people. It guarantees certain fundamental rights, along with a popularly elected non-executi ...

was proposed by

Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera (; ; first registered as George de Valero; changed some time before 1901 to Edward de Valera; 14 October 1882 – 29 August 1975) was an American-born Irish statesman and political leader. He served as the 3rd President of Ire ...

in 1937 and approved by the voters of the

Irish Free State

The Irish Free State (6 December 192229 December 1937), also known by its Irish-language, Irish name ( , ), was a State (polity), state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-ye ...

(thereafter simply Ireland).

Articles 2 and 3 of this Constitution claimed the whole island of Ireland as the national territory, while claiming legal jurisdiction only over the previous territory of the Irish Free State.

Article 15.2 allowed for the "creation or recognition of subordinate legislatures and for the powers and functions of these legislatures", which would have allowed for the continuation of the

Parliament of Northern Ireland

The Parliament of Northern Ireland was the home rule legislature of Northern Ireland, created under the Government of Ireland Act 1920, which sat from 7 June 1921 to 30 March 1972, when it was suspended because of its inability to restore ord ...

within a unitary Irish state.

In 1946, former

Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

told the

Irish High Commissioner to the United Kingdom, "I said a few words in Parliament the other day about your country because I still hope for a United Ireland. You must get those fellows in the north in, though; you can't do it by force. There is not, and never was, any bitterness in my heart towards your country." He later said, "You know I have had many invitations to visit Ulster but I have refused them all. I don't want to go there at all, I would much rather go to southern Ireland. Maybe I'll buy another horse with an entry in the Irish Derby."

Under the

Republic of Ireland Act 1948

The Republic of Ireland Act 1948 (No. 22 of 1948) is an Act of the Oireachtas which declares that the description of Ireland is the Republic of Ireland, and vests in the president of Ireland the power to exercise the executive authority of the ...

, Ireland declared that the country may officially be described as the Republic of Ireland and that the

President of Ireland

The president of Ireland () is the head of state of Republic of Ireland, Ireland and the supreme commander of the Defence Forces (Ireland), Irish Defence Forces. The presidency is a predominantly figurehead, ceremonial institution, serving as ...

had the executive authority of the state in its external relations. This was treated by the

British Commonwealth

The Commonwealth of Nations, often referred to as the British Commonwealth or simply the Commonwealth, is an international association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire

The B ...

as ending Irish membership. In response, the United Kingdom passed the

Ireland Act 1949

The Ireland Act 1949 ( 12, 13 & 14 Geo. 6. c. 41) is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom intended to deal with the consequences of the Republic of Ireland Act 1948 as passed by the Irish parliament, the Oireachtas.

Background

Follo ...

. Section 1(2) of this act affirmed the provision in the Treaty that the position of Ireland remained a matter for the Parliament of Northern Ireland:

Between 1956 and 1962, the IRA engaged in a

border campaign against

British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

and

Royal Ulster Constabulary

The Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) was the police force in Northern Ireland from 1922 to 2001. It was founded on 1 June 1922 as a successor to the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) Richard Doherty, ''The Thin Green Line – The History of the ...

outposts with the aim of ending British rule in Northern Ireland. This coincided with brief electoral success of Sinn Féin, which won four seats at the

1957 Irish general election

The 1957 Irish general election to the 16th Dáil was held on Tuesday, 5 March, following a dissolution of the 15th Dáil on 12 February by President of Ireland, President Seán T. O'Kelly on the request of Taoiseach John A. Costello on 4 Februa ...

. This was its first electoral success since 1927, and it did not win seats in the Republic of Ireland again until 1997. The border campaign was entirely unsuccessful in its aims. In 1957,

Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton (10 February 1894 – 29 December 1986), was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. Nickn ...

wrote that "I do not think that a United Ireland - with de Valera as a kind of Irish

Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru (14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat, and statesman who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20th century. Nehru was a prin ...

would do us much good. Let us stand by our friends."

Calls for unification, start of the Troubles

The

Northern Ireland civil rights movement

The Northern Ireland civil rights movement dates to the early 1960s, when a number of initiatives emerged in Northern Ireland which challenged the inequality and discrimination against ethnic Irish Catholics that was perpetrated by the Ulster Pr ...

emerged in 1967 to campaign for

civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' political freedom, freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and ...

for

Catholics

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

in Northern Ireland. Tensions between

republican and

loyalist

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cr ...

groups in the north erupted into outright violence in the late 1960s. In 1968 the Irish Taoiseach,

Jack Lynch

John Mary Lynch (15 August 1917 – 20 October 1999) was an Irish Fianna Fáil politician who served as Taoiseach from 1966 to 1973 and 1977 to 1979. He was Leader of Fianna Fáil from 1966 to 1979, Leader of the Opposition from 1973 to 1977, ...

, raised the issue of partition in London: "It has been the aim of my government and its predecessors to promote the reunification of Ireland by fostering a spirit of brotherhood among all sections of the Irish people. The clashes in the streets of Derry are an expression of the evils which partition has brought in its train." He later stated to the press that the ending of partition would be "a just and inevitable solution to the problems of Northern Ireland."

Lynch renewed his call to end partition in August 1969 when he proposed negotiations with

Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* Great Britain, a large island comprising the countries of England, Scotland and Wales

* The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, a sovereign state in Europe comprising Great Britain and the north-eas ...

with the hope of merging the Irish Republic and Northern Ireland into a federal type state. Lynch proposed that the two parliaments continue to function with a Council of Ireland having authority over the entire country. The Prime Minister of Northern Ireland

James Chichester-Clark

James Dawson Chichester-Clark, Baron Moyola (12 February 1923 – 17 May 2002) was the penultimate Prime Minister of Northern Ireland and eighth leader of the Ulster Unionist Party between 1969 and March 1971. He was Member of the Northern I ...

rejected the proposal. In August 1971 Lynch proposed that the

Government of Northern Ireland

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a ...

(Stormont) be replaced with an administration that would share power with Catholics. The next day the Northern Prime Minister

Brian Faulkner

Arthur Brian Deane Faulkner, Baron Faulkner of Downpatrick, (18 February 1921 – 3 March 1977), was the sixth and last Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, from March 1971 until his resignation in March 1972. He was also the Chief Executive ...

rejected Lynch's statement and stated that "no further attempt by us to deal constructively with the present Dublin government is possible." Later in 1971 British Labour Party leader (and future Prime Minister)

Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx (11 March 1916 – 23 May 1995) was a British statesman and Labour Party (UK), Labour Party politician who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, from 1964 to 1970 and again from 197 ...

proposed a plan that would lead to a united Ireland after a 15-year transitional period. He called for the establishment of a commission that would examine the possibility of creating a united Ireland which would be agreed upon by all three parliaments. The northern Prime Minister rejected the proposal and reiterated the desire that Northern Ireland remain an integral part of the United Kingdom. The Irish Taoiseach indicated the possibility of amending the Irish constitution to accommodate the Protestants of Northern Ireland and urged the British government to "declare its interest in encouraging the unity of Ireland".

In 1969 the British government deployed troops in what would become the longest continuous deployment in British military history

Operation Banner

Operation Banner was the operational name for the British Armed Forces' operation in Northern Ireland from 1969 to 2007, as part of the Troubles. It was the longest continuous deployment in British military history. The British Army was initia ...

. The

Provisional Irish Republican Army

The Provisional Irish Republican Army (Provisional IRA), officially known as the Irish Republican Army (IRA; ) and informally known as the Provos, was an Irish republican paramilitary force that sought to end British rule in Northern Ireland ...

(IRA) had begun a thirty-year campaign against British security forces with the aim of winning a united Ireland.

In 1970, the

Social Democratic and Labour Party

The Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP; ) is a social democratic and Irish nationalist political party in Northern Ireland. The SDLP currently has eight members in the Northern Ireland Assembly ( MLAs) and two members of Parliament (M ...

(SDLP) was established to campaign for civil rights and a united Ireland by peaceful, constitutional means. The party rose to be the dominant party representing the nationalist community until the early twenty-first century.

In 1972, the parliament of Northern Ireland was

suspended, and under the

Northern Ireland Constitution Act 1973

The Northern Ireland Constitution Act 1973 (c. 36) is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which received royal assent on 18 July 1973. The act abolished the suspended Parliament of Northern Ireland and the post of Governor and mad ...

, it was formally abolished. Section 1 of the 1973 Act stated,

A

border poll was held in Northern Ireland in 1973. The SDLP and Sinn Féin called for a boycott of the poll. 98.9% of votes cast supported remaining part of the United Kingdom. The poll was overwhelmingly boycotted by nationalists, and the turnout was therefore 58.7%. The pro-UK vote did however represent 57.5% of the entire electorate, notwithstanding the boycott.

In 1983, the Irish government led by Taoiseach

Garret FitzGerald

Garret Desmond FitzGerald (9 February 192619 May 2011) was an Irish Fine Gael politician, economist, and barrister who served twice as Taoiseach, serving from 1981 to 1982 and 1982 to 1987. He served as Leader of Fine Gael from 1977 to 1987 an ...

established the

New Ireland Forum

The New Ireland Forum was a forum in 1983–1984 at which Irish nationalist political parties discussed potential political developments that might alleviate the Troubles in Northern Ireland. The Forum was established by Garret FitzGerald, then ...

as a consultation on a new Ireland. Though all parties in Ireland were invited, the only ones to attend were

Fine Gael

Fine Gael ( ; ; ) is a centre-right, liberal-conservative, Christian democratic political party in Ireland. Fine Gael is currently the third-largest party in the Republic of Ireland in terms of members of Dáil Éireann. The party had a member ...

,

Fianna Fáil

Fianna Fáil ( ; ; meaning "Soldiers of Destiny" or "Warriors of Fál"), officially Fianna Fáil – The Republican Party (), is a centre to centre-right political party in Ireland.

Founded as a republican party in 1926 by Éamon de ...

, the

Labour Party and the

SDLP

The Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP; ) is a social democratic and Irish nationalist political party in Northern Ireland. The SDLP currently has eight members in the Northern Ireland Assembly ( MLAs) and two members of Parliament (MPs ...

. Its report considered three options: a unitary state, i.e., a united Ireland; a federal/confederal state; and joint sovereignty. These options were rejected by Prime Minister

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013), was a British stateswoman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of th ...

. In 1985, the governments of Ireland and of the United Kingdom signed the

Anglo-Irish Agreement

The Anglo-Irish Agreement was a 1985 treaty between the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland which aimed to help bring an end to the Troubles in Northern Ireland. The treaty gave the Irish government an advisory role in Northern Irelan ...

; the British government accepted an advisory role for the Irish government in the future of Northern Ireland. Article 1 of the Agreement stated that the future constitutional position of Northern Ireland would be a matter for the people of Northern Ireland:

In the

Downing Street Declaration

The Downing Street Declaration was a joint declaration issued on 15 December 1993 by the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, John Major, and the Irish Taoiseach ( English: Prime Minister), Albert Reynolds, at the British Prime Minister's offi ...

, Taoiseach

Albert Reynolds

Albert Martin Reynolds (3 November 1932 – 21 August 2014) was an Irish Fianna Fáil politician who served as Taoiseach and Leader of Fianna Fáil from 1992 to 1994. He held various cabinet positions between 1979 and 1991, including Ministe ...

and Prime Minister

John Major

Sir John Major (born 29 March 1943) is a British retired politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1990 to 1997. Following his defeat to Ton ...

issued a joint statement, in which Major, "reiterated on behalf of the British Government, that they have no selfish strategic or economic interest in Northern Ireland".

Good Friday Agreement

The

Good Friday Agreement

The Good Friday Agreement (GFA) or Belfast Agreement ( or ; or ) is a pair of agreements signed on 10 April (Good Friday) 1998 that ended most of the violence of the Troubles, an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland since the la ...

in 1998 was a culmination of the

peace process

A peace process is the set of political sociology, sociopolitical negotiations, agreements and actions that aim to solve a specific armed conflict.

Definitions

Prior to an armed conflict occurring, peace processes can include the prevention of ...

. The agreement acknowledged nationalism and unionism as "equally legitimate, political aspirations". In the

Northern Ireland Assembly

The Northern Ireland Assembly (; ), often referred to by the metonym ''Stormont'', is the devolved unicameral legislature of Northern Ireland. It has power to legislate in a wide range of areas that are not explicitly reserved to the Parliam ...

, all members would designate as Unionist, Nationalist, or Other, and certain measures would require cross-community support. The agreement was signed by the governments of Ireland and of the United Kingdom. In Northern Ireland, it was supported by all parties who were in the

Northern Ireland Forum

The Northern Ireland Forum for Political Dialogue was a body set up in 1996 as part of a process of negotiations that eventually led to the Good Friday Agreement in 1998.

The forum was elected, with five members being elected for each List o ...

with the exception of the

Democratic Unionist Party

The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) is a Unionism in Ireland, unionist, Ulster loyalism, loyalist, British nationalist and national conservative political party in Northern Ireland. It was founded in 1971 during the Troubles by Ian Paisley, who ...

and the

UK Unionist Party

The UK Unionist Party (UKUP) was a small unionist political party in Northern Ireland from 1995 to 2008 that opposed the Good Friday Agreement. It was nominally formed by Robert McCartney, formerly of the Ulster Unionist Party, to contest t ...

, and it was supported by all parties in the

Oireachtas

The Oireachtas ( ; ), sometimes referred to as Oireachtas Éireann, is the Bicameralism, bicameral parliament of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. The Oireachtas consists of the president of Ireland and the two houses of the Oireachtas (): a house ...

. It was also opposed by

dissident republicans

Dissident republicans () are Irish republicans who do not support the Northern Ireland peace process. The peace agreements followed a 30-year conflict known as the Troubles, in which over 3,500 people were killed and 47,500 injured, and in which ...

, including

Republican Sinn Féin

Republican Sinn Féin or RSF () is an Irish republican political party in Ireland. RSF claims to be heirs of the Sinn Féin party founded in 1905; the party took its present form in 1986 following a split in Sinn Féin. RSF members take seats w ...

and the

32 County Sovereignty Movement

The 32 County Sovereignty Movement, often abbreviated to 32CSM or 32csm, is an Irish republican group that was founded by Bernadette Sands McKevitt. It does not contest elections but acts as a pressure group, with branches or ''cumainn'' organ ...

. It was approved in referendums

in Northern Ireland and in

the Republic of Ireland

Ireland ( ), also known as the Republic of Ireland (), is a country in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe consisting of 26 of the 32 Counties of Ireland, counties of the island of Ireland, with a population of about 5.4 million. ...

.

Included in the Agreement were provisions which became part of the

Northern Ireland Act 1998

__NOTOC__

The Northern Ireland Act 1998 (c. 47) is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which allowed Westminster to devolve power to Northern Ireland, after decades of direct rule.

It renamed the New Northern Ireland Assembly, establi ...

on the form of a future referendum on a united Ireland. In essence the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement provided the opportunity for self determination and mutual respect. Those born in Northern Ireland could identify as Irish. The freedom of movement, allowed citizens of either jurisdiction to live in which ever part of the island they wanted, therby enabling them to choose which state they paid taxes to or claimed benefits from. The 'Two state' solution advocated for conflict resolution in other jurisdictions therefore applied. Provision within the Agreement allows for a simple majority to vote in favour of Irish Unification, but does nothing to explain how the dissolution of the two state solution, leads to a peaceful and prosperous new country when potentially 13% of the 'new' country are forced into it against their will and have no allegiance to it nor incentive for it to succeed. A fear of political, civil and economic turmoil and a lack of protection for minority rights, as experienced by the Catholic community in Northern Ireland and the Protestant community in the Republic of Ireland historically, is a key driver towards the desire for the maintenance of the status quo on both sides of the border.

On the establishment of the institutions in 1999,

Articles 2 and 3 of the Constitution of Ireland

Article 2 and Article 3 of the Constitution of Ireland () were adopted with the Constitution of Ireland as a whole on 29 December 1937, but revised completely by means of the Nineteenth Amendment which became effective 2 December 1999. As amende ...

were amended to read:

Brexit, the Northern Ireland Protocol and elections

In a

referendum

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate (rather than their Representative democracy, representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either bin ...

in June 2016, England and Wales voted to

leave the European Union. The majority of those voting in Northern Ireland and in Scotland, however, voted for the UK to remain. Of the parties in the Assembly, only the

Democratic Unionist Party

The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) is a Unionism in Ireland, unionist, Ulster loyalism, loyalist, British nationalist and national conservative political party in Northern Ireland. It was founded in 1971 during the Troubles by Ian Paisley, who ...

(DUP), the

Traditional Unionist Voice

The Traditional Unionist Voice (TUV) is a unionist political party in Northern Ireland. In common with all other Northern Irish unionist parties, the TUV's political programme has as its '' sine qua non'' the preservation of Northern Ireland's pl ...

(TUV) and

People Before Profit

People Before Profit (, PBP) is a Trotskyist political party formed in October 2005. The party is active in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

History As Socialist Environmental Alliance

People Before Profit was established in 200 ...

(PBP) had campaigned for a Leave vote. Irish politicians began the discussion regarding possible changes to the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. The status and treatment of Northern Ireland and

Gibraltar

Gibraltar ( , ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory and British overseas cities, city located at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, on the Bay of Gibraltar, near the exit of the Mediterranean Sea into the A ...

, the only parts under control of the United Kingdom which would have

new land borders with the EU following the

UK withdrawal, became important to the negotiations, along with access to the regional development assistance scheme (and new funding thereof) from the European Union.

Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( ; ; ) is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active in both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The History of Sinn Féin, original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Griffit ...

cited these concerns as the basis for new discussion on a united Ireland. These calls were rejected by the British government and Unionist politicians, with

Theresa Villiers

Dame Theresa Anne Villiers (born 5 March 1968) is a British politician who served as the Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of Parliament (MP) for Chipping Barnet (UK Parliament constituency), Chipping Barnet from 2005 United Kingdom ...

arguing that there was no evidence that opinion in Northern Ireland had shifted towards being in favour of a united Ireland.

2017 Assembly election

In the

2017 Assembly election, the DUP lost ten seats and came just one seat ahead of Sinn Féin. Sinn Féin used this opportunity to call for a Northern Ireland referendum on a united Ireland.

Theoretical return to EU confirmed in a United Ireland

The

Brexit Secretary,

David Davis, confirmed to

Mark Durkan

Mark Durkan (born 26 June 1960) is a retired Irish nationalist politician from Northern Ireland. Durkan was the deputy First Minister of Northern Ireland from November 2001 to October 2002, and the Leader of the Social Democratic and Labour Pa ...

, the

SDLP

The Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP; ) is a social democratic and Irish nationalist political party in Northern Ireland. The SDLP currently has eight members in the Northern Ireland Assembly ( MLAs) and two members of Parliament (MPs ...

MP for

Foyle, that in the event of Northern Ireland becoming part of a united Ireland, "Northern Ireland would be in a position of becoming part of an existing EU member state, rather than seeking to join the EU as a new independent state." Enda Kenny pointed to the provisions that allowed

East Germany

East Germany, officially known as the German Democratic Republic (GDR), was a country in Central Europe from Foundation of East Germany, its formation on 7 October 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with West Germany (FRG) on ...

to join the

West

West is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some Romance langu ...

and the EEC during the

reunification of Germany

German reunification () was the process of re-establishing Germany as a single sovereign state, which began on 9 November 1989 and culminated on 3 October 1990 with the dissolution of the German Democratic Republic and the integration of i ...

as a precedent.

In April 2017 the

European Council

The European Council (informally EUCO) is a collegiate body (directorial system) and a symbolic collective head of state, that defines the overall political direction and general priorities of the European Union (EU). It is composed of the he ...

acknowledged that, in the event of Irish unification, "the entire territory of such a united Ireland would

..be part of the European Union." The SDLP manifesto for the

2017 UK general election

The 2017 United Kingdom general election was held on Thursday 8 June 2017, two years after the 2015 United Kingdom general election, previous general election in 2015; it was the first since 1992 United Kingdom general election, 1992 to be held ...

called for a referendum on a united Ireland after the UK withdraws from the EU. However the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland at the time,

James Brokenshire

James Peter Brokenshire (8 January 1968 – 7 October 2021) was a British politician. A member of the Conservative Party, he served in Theresa May's cabinet as Secretary of State for Northern Ireland from 2016 to 2018 and then as Secretary of ...

, said the conditions for a vote are "not remotely satisfied".

2017 general election

After the 2017 election, the UK government was reliant on

confidence and supply

In parliamentary system, parliamentary democracies based on the Westminster system, confidence and supply is an arrangement under which a minority government (one which does not control a majority in the legislature) receives the support of one ...

from the

Democratic Unionist Party

The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) is a Unionism in Ireland, unionist, Ulster loyalism, loyalist, British nationalist and national conservative political party in Northern Ireland. It was founded in 1971 during the Troubles by Ian Paisley, who ...

. The deal

supported the Conservative led government through the Brexit negotiation process. The 2020

Brexit withdrawal agreement

The Brexit withdrawal agreement, officially titled Agreement on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union and the European Atomic Energy Community, is a treaty between the European Uni ...

included the

Northern Ireland Protocol

The Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland, commonly abbreviated to the Northern Ireland Protocol (NIP), is a protocol to the Brexit withdrawal agreement that sets out Northern Ireland’s post-Brexit relationship with both the EU and Great Bri ...

, which established different trade rules for the territory than Great Britain. While Northern Ireland would ''de jure'' leave the single market, it would still enforce all EU customs rules, while Britain would diverge. This would result in a regulatory "border in the Irish Sea" rather than a border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, and caused fears from unionist politicians about Brexit causing a weakening of the UK.

Brexit negotiations continue

The new UK prime minister

Boris Johnson

Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson (born 19 June 1964) is a British politician and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 2019 to 2022. He wa ...

continued to claim no trade border would take form as late as August 2020, despite having

negotiated its creation.

Dominic Cummings

Dominic Mckenzie Cummings (born 25 November 1971) is a British political strategist who served as Chief Adviser to British Prime Minister Boris Johnson from 24 July 2019 until he resigned on 13 November 2020.

From 2007 to 2014, he was a speci ...

later claimed that Johnson did not understand the deal at the time it was signed, while

Ian Paisley Jr

Ian Richard Kyle Paisley Jr (born 12 December 1966) is a Northern Irish businessman and former unionist politician. A member of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), he served as the Member of Parliament (MP) for North Antrim from 2010 to 2024, ...

claimed that Johnson had privately promised to "tear up" the deal after it was agreed. In September, Johnson sought to

unilaterally dis-apply parts of the Northern Ireland protocol, despite acknowledging that this broke international law. The bill was rejected by the

House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

, resulting in several provisions being withdrawn before it passed in December 2020- shortly before the protocol was due to come into effect.

The implementation of the protocol, and the new regulatory hurdles had a negative effect on east–west trade, and drew strong condemnation from unionist figures, including DUP members such as First Minister

Arlene Foster

Arlene Isobel Foster, Baroness Foster of Aghadrumsee (née Kelly; born 17 July 1970), is a British broadcaster and politician from Northern Ireland who is serving as Chair of Intertrade UK since September 2024. She previously served as First ...

. Staff making the required checks were threatened, resulting in a temporary suspension of checks at Larne and Belfast ports. In February 2021, several unionist parties began a legal challenge, alleging that the protocol violated the

Act of Union 1800

The Acts of Union 1800 were parallel acts of the Parliament of Great Britain and the Parliament of Ireland which united the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland (previously in personal union) to create the United Kingdom of G ...

, the bill which had originally merged Ireland with the United Kingdom, as well as the Good Friday Agreement. The challenge was dismissed in June, with the court deciding that the protocol- and other legislation in the intervening 200 years- had effectively repealed parts of the Act of Union. On 4 March the

Loyalist Communities Council

The Loyalist Communities Council (LCC) is a British Unionist and Loyalist organisation in Northern Ireland.

The organisation was founded in 2015 by English diplomat Jonathan Powell, and former Ulster Unionist Party chairman David Campbell, ...

withdrew its support for the peace agreement- while indicating that opposition to it should not be in the form of violence.

Riots erupted in loyalist areas at the end of the month, continuing until 9 April. The protocol's implementation, and opposition within the DUP, resulted in the announcement of Foster's resignation on 28 April. ''The Irish Times'' interviewed loyalist

Shankill Road

The Shankill Road () is one of the main roads leading through West Belfast, in Northern Ireland. It runs through the working-class, predominantly loyalist, area known as the Shankill.

The road stretches westwards for about from central Belfast ...

residents that month and found significant anger at the DUP, and accusations that the community had been "sold short" on the protocol. Foster was replaced by

Paul Givan

Paul Jonathan Givan (born 12 October 1981) is a Northern Irish unionist politician who served as First Minister and deputy First Minister of Northern Ireland, First Minister of Northern Ireland from 2021 to 2022. A member of the Democratic Unio ...

later that year, though he too resigned in February 2022 over the continued existence of the protocol.

The UK government sought to re-negotiate the protocol, a prospect poorly received by EU leaders such as

Emmanuel Macron

Emmanuel Jean-Michel Frédéric Macron (; born 21 December 1977) is a French politician who has served as President of France and Co-Prince of Andorra since 2017. He was Ministry of Economy and Finance (France), Minister of Economics, Industr ...

. When discussing the effects of the protocol in June 2021,

Leo Varadkar

Leo Eric Varadkar ( ; born 18 January 1979) is an Irish former Fine Gael politician who served as Taoiseach from 2017 to 2020 and from 2022 to 2024, as Tánaiste from 2020 to 2022, and as leader of Fine Gael from 2017 to 2024. A Teachta Dála, ...

outlined a vision for a united Irish state with devolved representation in the North. He added "It should be part of our mission as a party to work towards it." Talks aimed at amending the customs checks required by the protocol began in October; though

Maroš Šefčovič

Maroš Šefčovič (; born 24 July 1966) is a Slovak diplomat and politician serving as European Commissioner for Trade and Economic Security; Interinstitutional Relations and Transparency (2024–2029) in the Von der Leyen Commission II. Prior t ...

indicated that the protocol itself will not be re-negotiated. In December, the UK's chief negotiator

Lord Frost

David George Hamilton Frost, Baron Frost (born 21 February 1965) is a former British diplomat, civil servant and politician who served as a Minister of State at the Cabinet Office between March and December 2021. Frost was Chief Negotiator ...

resigned his post over "concerns about the current direction of travel".

2022 Assembly election

After the results of the

2022 Northern Ireland Assembly election, Sinn Féin were set to become the largest party in the assembly for the first time in history, with the DUP coming in second place. Sinn Féin won 27 seats, compared to the DUP's 25. Sinn Féin said that it will be at least a decade-long plan for Irish unity, which would only happen after an island-wide conversation.

2023–24 and return to Stormont

In February 2023, UK Prime Minister

Rishi Sunak

Rishi Sunak (born 12 May 1980) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 2022 to 2024. Following his defeat to Keir Starmer's La ...

and President of the

European Commission

The European Commission (EC) is the primary Executive (government), executive arm of the European Union (EU). It operates as a cabinet government, with a number of European Commissioner, members of the Commission (directorial system, informall ...

Ursula von der Leyen

Ursula Gertrud von der Leyen (; ; born 8 October 1958) is a German politician, serving as president of the European Commission since 2019. She served in the Cabinet of Germany, German federal government between 2005 and 2019, holding position ...

announced a new agreement called the

Windsor Framework

The Windsor Framework is a post-Brexit legal agreement between the European Union and the United Kingdom which adjusts the operation of the Northern Ireland Protocol. The Framework was announced on 27 February 2023, formally adopted by both pa ...

including a green lane for trade between Britain and Northern Ireland and a red lane for Republic of Ireland and EU trade. Sinn Fein called for a restoration of devolved governance following the deal whilst the DUP continued their boycott.

On 31 January 2024, a deal between the DUP and the UK government led to the abolition of "routine" checks on goods from Britain sent to Northern Ireland with the intention of staying there. A new body, Intertrade UK will be formed to promote trade within the UK, modelled on the all Ireland body,

InterTradeIreland. The deal also includes UK government ministers being compelled to inform Parliament if a Bill they are introducing will have "significant adverse implications for Northern Ireland's place in the UK internal market". On the basis of the deal, the DUP decided to return to devolved governance in Stormont.

On 3 February,

Michelle O'Neill

Michelle O'Neill ( Doris; born 10 January 1977) is an Irish politician who has been First Minister of Northern Ireland since February 2024 and President of Sinn Féin#Vice Presidents, Vice President of Sinn Féin since 2018. She has also been ...

made history by becoming the first-ever Irish nationalist First Minister. After taking office as First Minister, O'Neill stated that she expected a referendum on the reunification to be held within the next decade, which would be in accordance with the 1998

Good Friday Agreement

The Good Friday Agreement (GFA) or Belfast Agreement ( or ; or ) is a pair of agreements signed on 10 April (Good Friday) 1998 that ended most of the violence of the Troubles, an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland since the la ...

signed by the UK and Ireland.

Shared Island

In 2021, the

Irish Government

The Government of Ireland () is the executive authority of Ireland, headed by the , the head of government. The government – also known as the cabinet – is composed of ministers, each of whom must be a member of the , which consists of ...

launched the "Shared Island" initiative, to fund projects enhancing cross-border cooperation. In February 2024, it was announced that a total of €1 billion of funding from the Irish government was committed for:

* €600m towards the

A5 road

A5 Road may refer to:

;Africa

* A5 highway (Nigeria), a road connecting Lagos and Ibadan

* A5 road (Zimbabwe), a road connecting Harare and Bulawayo

;Americas

* Quebec Autoroute 5, a road in Quebec, Canada

* County Route A5 (California) or Bowm ...

* Construction of

Narrow Water Bridge between the

Mourne Mountains

The Mourne Mountains ( ; ), also called the Mournes or the Mountains of Mourne, are a predominantly granite mountain range in County Down in the south-east of Northern Ireland. They include the highest mountain in all of Ulster, Slieve Donard ...

and the

Cooley Peninsula

The Cooley Peninsula (, older ''Cúalṅge'') is a hilly peninsula in the north of County Louth on the east coast of Ireland; the peninsula includes the small town of Carlingford, the port of Greenore and the village of Omeath.

Geography

...

* New hourly rail service between Belfast and Dublin

* €50m towards

Casement Park

Casement Park () is the principal Gaelic games stadium in Belfast, Northern Ireland. It is located in Andersonstown Road in the west of the city, and is named after the Irish revolutionary Roger Casement.

The stadium, which has been closed si ...

* €10m towards a visitor experience at the

Battle of the Boyne site

* Cross-border women’s entrepreneurship

The Narrow Water bridge, linking

Omeath

Omeath (; or ''Uí Meth'') is a village on the Cooley Peninsula in County Louth, Ireland, close to the border with Northern Ireland. It is roughly midway between Dublin and Belfast, very near the County Louth and County Armagh / County Down bor ...

to

Warrenpoint

Warrenpoint () is a small port town and civil parish in County Down, Northern Ireland. It sits at the head of Carlingford Lough, south of Newry, and is separated from the Republic of Ireland by a narrow strait. The town is beside the village ...

, began construction in June 2024. During an

Ireland's Future

Ireland's Future is a civic nationalist Ireland, Irish non-profit company formed in 2017 to campaign for new constitutional arrangements on the island of Ireland.

History

As part of its campaigning, Ireland's Future wrote a series of open let ...

event in the same month, Taoiseach Leo Varadkar proposed that the Irish government set up a State fund using current budget surpluses that could then be used in the event of a United Ireland. Also at the event, Michelle O'Neill promised that Casement Park would be built "on my watch".

Potential referendum time and criteria

Timescale proposals

In 2020, Ireland Taoiseach

Micheál Martin