The Republican Party, also known as the Grand Old Party (GOP), is a

right-wing

Right-wing politics is the range of political ideologies that view certain social orders and hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this position based on natural law, economics, authority, property ...

political party in the United States. One of the

two major parties, it emerged as the main rival of the then-dominant

Democratic Party in the 1850s, and the two parties have dominated

American politics

In the United States, politics functions within a framework of a constitutional federal republic, federal democratic republic with a presidential system. The three distinct branches Separation of powers, share powers: United States Congress, C ...

since then.

The Republican Party was founded in 1854 by

anti-slavery

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was France in 1315, but it was later used in its colonies. T ...

activists opposing the

Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law b ...

and the expansion of

slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

into U.S. territories. It rapidly gained support in the

North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating Direction (geometry), direction or geography.

Etymology

T ...

, drawing in former

Whigs and

Free Soilers.

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

's

election in 1860 led to the secession of Southern states and the outbreak of the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

. Under Lincoln and a Republican-controlled Congress, the party led efforts to preserve the

Union, defeat the

Confederacy, and abolish slavery. During the

Reconstruction era

The Reconstruction era was a period in History of the United States, US history that followed the American Civil War (1861-65) and was dominated by the legal, social, and political challenges of the Abolitionism in the United States, abol ...

, Republicans sought to extend

civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' political freedom, freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and ...

protections to

freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, slaves were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their owners), emancipation (granted freedom as part of a larger group), or self- ...

, but by the late 1870s the party shifted its focus toward business interests and

industrial expansion. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it dominated national politics, promoting

protective tariff

Protective tariffs are tariffs that are enacted with the aim of protecting a domestic industry. They aim to make imported goods cost more than equivalent goods produced domestically, thereby causing sales of domestically produced goods to rise, ...

s, infrastructure development, and ''

laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( , from , ) is a type of economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies or regulations). As a system of thought, ''laissez-faire'' ...

'' economic policies, while navigating internal divisions between

progressive and

conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

factions. The party's support declined during the

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

, as the

New Deal coalition

The New Deal coalition was an American political coalition that supported the Democratic Party beginning in 1932. The coalition is named after President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal programs, and the follow-up Democratic presidents. It was ...

reshaped American politics. Republicans returned to national power with

the 1952 election of

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

, whose

moderate conservatism

Moderate conservatism is a politically moderate version of conservatism that is less demanding than classical conservatism, and can be divided into several subtypes, such as liberal conservatism. The term is principally used in countries where ...

reflected a pragmatic acceptance of many

New Deal

The New Deal was a series of wide-reaching economic, social, and political reforms enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1938, in response to the Great Depression in the United States, Great Depressi ...

-era programs.

The Republican Party has undergone several ideological and demographic shifts since the mid-20th century. Following the

civil rights era, it gained strength in the South through the

Southern strategy, which appealed to many White voters disaffected by Democratic support for civil rights. The

1980 election of

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

marked a major realignment, consolidating

a coalition of

free market

In economics, a free market is an economic market (economics), system in which the prices of goods and services are determined by supply and demand expressed by sellers and buyers. Such markets, as modeled, operate without the intervention of ...

advocates,

social conservatives

Social conservatism is a political philosophy and a variety of conservatism which places emphasis on traditional social structures over social pluralism. Social conservatives organize in favor of duty, traditional values and social instit ...

, and foreign policy

hawks

Hawks are bird of prey, birds of prey of the family Accipitridae. They are very widely distributed and are found on all continents, except Antarctica.

The subfamily Accipitrinae includes goshawks, sparrowhawks, sharp-shinned hawks, and othe ...

. Since 2009, internal divisions have grown, leading to a shift toward

right-wing populism

Right-wing populism, also called national populism and right populism, is a political ideology that combines right-wing politics with populist rhetoric and themes. Its rhetoric employs anti- elitist sentiments, opposition to the Establis ...

, which ultimately became its dominant faction. This culminated in the

2016 election of

Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who is the 47th president of the United States. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he served as the 45 ...

, whose leadership style and political agenda—often referred to as

Trumpism

Trumpism, also referred to as the Make America Great Again (MAGA) movement, is the political movement and ideology behind U.S. president Donald Trump and his political base. It comprises ideologies such as right-wing populism, right-wing ...

—reshaped the party's identity.

In the 21st century, the Republican Party's strongest demographics are

rural voters,

White Southerners

White Southerners are White Americans from the Southern United States, originating from the various waves of Northwestern European immigration to the region beginning in the 17th century.

Academic John Shelton Reed argues that "Southerners' d ...

,

evangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide, interdenominational movement within Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that emphasizes evangelism, or the preaching and spreading of th ...

Christians, men,

senior citizens

Old age is the range of ages for people nearing and surpassing life expectancy. People who are of old age are also referred to as: old people, elderly, elders, senior citizens, seniors or older adults. Old age is not a definite biological sta ...

, and

voters

Voting is the process of choosing officials or policies by casting a ballot, a document used by people to formally express their preferences. Republics and representative democracies are governments where the population chooses representatives ...

without

college degrees.

On economic issues, the party has maintained a pro-capital attitude since its inception. It currently supports Trump's

mercantilist

Mercantilism is a nationalist economic policy that is designed to maximize the exports and minimize the imports of an economy. It seeks to maximize the accumulation of resources within the country and use those resources for one-sided trade. ...

policies,

including

tariffs

A tariff or import tax is a duty imposed by a national government, customs territory, or supranational union on imports of goods and is paid by the importer. Exceptionally, an export tax may be levied on exports of goods or raw materials and is ...

on imports on all countries at the highest rates in the world

while opposing

globalization

Globalization is the process of increasing interdependence and integration among the economies, markets, societies, and cultures of different countries worldwide. This is made possible by the reduction of barriers to international trade, th ...

and

free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold Economic liberalism, economically liberal positions, while economic nationalist politica ...

. It also supports low income taxes and deregulation while opposing

labor unions

A trade union (British English) or labor union (American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment, such as attaining better wages ...

, a

public health insurance option and

single-payer healthcare

Single-payer healthcare is a type of universal healthcare, in which the costs of essential healthcare for all residents are covered by a single public system (hence "single-payer"). Single-payer systems may contract for healthcare services from pr ...

.

On social issues, it advocates for

restricting abortion, supports

tough on crime policies, such as

capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence (law), sentence ordering that an offender b ...

and the prohibition of

recreational drug use

Recreational drug use is the use of one or more psychoactive drugs to induce an altered state of consciousness, either for pleasure or for some other casual purpose or pastime. When a psychoactive drug enters the user's body, it induces an Sub ...

, promotes gun ownership and

easing gun restrictions, and opposes

transgender rights

The legal status of transgender people varies greatly around the world. Some countries have enacted laws protecting the rights of transgender individuals, but others have criminalized their gender identity or expression. In many cases, transg ...

. The party favors limited legal

immigration

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not usual residents or where they do not possess nationality in order to settle as Permanent residency, permanent residents. Commuting, Commuter ...

but strongly opposes

illegal immigration

Illegal immigration is the migration of people into a country in violation of that country's immigration laws, or the continuous residence in a country without the legal right to do so. Illegal immigration tends to be financially upward, wi ...

and favors the

deportation

Deportation is the expulsion of a person or group of people by a state from its sovereign territory. The actual definition changes depending on the place and context, and it also changes over time. A person who has been deported or is under sen ...

of those without permanent legal status, such as

undocumented immigrants

Illegal immigration is the migration of people into a country in violation of that country's immigration laws, or the continuous residence in a country without the legal right to do so. Illegal immigration tends to be financially upward, wi ...

and those with

temporary protected status. In foreign policy, the party supports U.S. aid to

Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

but is divided on aid to

Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

and improving

relations with Russia,

with Trump's ascent empowering an

isolationist "

America First" foreign policy agenda.

History

In 1854, the Republican Party emerged to combat the expansion of slavery into western territories after the passing of the

Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law b ...

. The early Republican Party consisted of northern Protestants, factory workers, professionals, businessmen, prosperous farmers, and after the

Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

also of black former slaves. The party had very little support from white Southerners at the time, who predominantly backed the Democratic Party in the

Solid South

The Solid South was the electoral voting bloc for the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party in the Southern United States between the end of the Reconstruction era in 1877 and the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In the aftermath of the Co ...

, and from Irish and German Catholics, who made up a major Democratic voting block. While both parties adopted

pro-business policies in the 19th century, the early GOP was distinguished by its support for the

national banking system, the

gold standard

A gold standard is a backed currency, monetary system in which the standard economics, economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the ...

,

railroads

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport using wheeled vehicles running in tracks, which usually consist of two parallel steel rails. Rail transport is one of the two primary means of land transport, next to road ...

, and

high tariffs. The party opposed the expansion of slavery before 1861 and led the fight to destroy the

Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), also known as the Confederate States (C.S.), the Confederacy, or Dixieland, was an List of historical unrecognized states and dependencies, unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United State ...

(1861–1865). While the Republican Party had almost no presence in the

Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, Dixieland, or simply the South) is List of regions of the United States, census regions defined by the United States Cens ...

at its inception, it was very successful in the

Northern United States

The Northern United States, commonly referred to as the American North, the Northern States, or simply the North, is a geographical and historical region of the United States.

History Early history

Before the 19th century westward expansion, the ...

, where by 1858 it had enlisted former

Whigs and former

Free Soil Democrats to form majorities in nearly every Northern state.

With the election of its first president,

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

, in 1860, the party's success in guiding the

Union to victory in the Civil War, and the party's role in the abolition of slavery, the Republican Party largely dominated the national political scene until 1932. In 1912, former Republican president

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

formed the

Progressive Party after being rejected by the GOP and

ran unsuccessfully as a third-party presidential candidate calling for

social reforms. The GOP lost its congressional majorities during the

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

(1929–1940); under President

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

, the Democrats formed a winning

New Deal coalition

The New Deal coalition was an American political coalition that supported the Democratic Party beginning in 1932. The coalition is named after President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal programs, and the follow-up Democratic presidents. It was ...

that was dominant from 1932 through 1964.

After the

Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and United States labor law, labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on Race (human categorization), race, Person of color, color, religion, sex, and nationa ...

, the

Voting Rights Act of 1965

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of federal legislation in the United States that prohibits racial discrimination in voting. It was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson during the height of the civil rights move ...

, and the

Southern strategy, the party's core base shifted with the Southern states becoming more reliably Republican in presidential politics and the Northeastern states becoming more reliably Democratic. White voters increasingly identified with the Republican Party after the 1960s. Following the Supreme Court's 1973 decision in ''

Roe v. Wade

''Roe v. Wade'', 410 U.S. 113 (1973),. was a List of landmark court decisions in the United States, landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that the Constitution of the United States protected the right to have an ...

'', the Republican Party opposed abortion in its party platform and grew its support among

evangelicals

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide, interdenominational movement within Protestant Christianity that emphasizes evangelism, or the preaching and spreading of the Christian g ...

.

The Republican Party won five of the six presidential elections from 1968 to 1988. Two-term President

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

, who held office from 1981 to 1989, was a transformative party leader. His

conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

policies called for reduced social

government spending

Government spending or expenditure includes all government consumption, investment, and transfer payments. In national income accounting, the acquisition by governments of goods and services for current use, to directly satisfy the individual or ...

and

regulation

Regulation is the management of complex systems according to a set of rules and trends. In systems theory, these types of rules exist in various fields of biology and society, but the term has slightly different meanings according to context. Fo ...

, increased military spending,

lower taxes, and a strong anti-

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

foreign policy. Reagan's influence upon the party persisted into the 21st century.

Since the 1990s, the party's support has chiefly come from the South, the

Great Plains

The Great Plains is a broad expanse of plain, flatland in North America. The region stretches east of the Rocky Mountains, much of it covered in prairie, steppe, and grassland. They are the western part of the Interior Plains, which include th ...

, the

Mountain States

The Mountain states (also known as the Mountain West or the Interior West) form one of the nine geographic divisions of the United States that are officially recognized by the United States Census Bureau. It is a subregion of the Western Un ...

, and

rural areas

In general, a rural area or a countryside is a geographic area that is located outside towns and cities. Typical rural areas have a low population density and small settlements. Agricultural areas and areas with forestry are typically descri ...

in the North.

It supports

free market economics,

cultural conservatism

Cultural conservatism is described as the protection of the cultural heritage of a nation state, or of a culture not defined by state boundaries. It is sometimes associated with criticism of multiculturalism, and anti-immigration sentiment. B ...

, and

originalism

Originalism is a legal theory in the United States which bases constitutional, judicial, and statutory interpretation of text on the original understanding at the time of its adoption. Proponents of the theory object to judicial activism ...

in

constitutional jurisprudence. There have been 19 Republican presidents, the most from any one political party.

Trump era

In

the 2016 presidential election, Republican nominee

Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who is the 47th president of the United States. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he served as the 45 ...

defeated Democratic nominee

Hillary Clinton

Hillary Diane Rodham Clinton ( Rodham; born October 26, 1947) is an American politician, lawyer and diplomat. She was the 67th United States secretary of state in the administration of Barack Obama from 2009 to 2013, a U.S. senator represent ...

. The result was unexpected; polls leading up to the election showed Clinton leading the race. Trump's victory was fueled by narrow victories in three states—

Michigan

Michigan ( ) is a peninsular U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest, Upper Midwestern United States. It shares water and land boundaries with Minnesota to the northwest, Wisconsin to the west, ...

,

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

, and

Wisconsin

Wisconsin ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest of the United States. It borders Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake Michigan to the east, Michig ...

—that had been part of the

Democratic blue wall for decades.

It was attributed to strong support amongst working-class white voters, who felt dismissed and disrespected by the political establishment.

Trump became popular with them by abandoning Republican establishment orthodoxy in favor of a broader nationalist message.

His election accelerated the Republican Party's shift towards right-wing populism and resulted in decreasing influence among its conservative factions.

After

the 2016 elections, Republicans

maintained their majority in the Senate,

the House, and

governorships, and wielded newly acquired executive power with Trump's election. The Republican Party controlled 69 of 99 state legislative chambers in 2017, the most it had held in history. The Party also held 33 governorships, the most it had held since 1922. The party had total control of government in 25 states, the most since 1952. The opposing Democratic Party held full control of only five states in 2017. In

the 2018 elections, Republicans lost control of the House, but strengthened their hold on the Senate.

Over the course of his presidency, Trump appointed three justices to

the Supreme Court:

Neil Gorsuch

Neil McGill Gorsuch ( ; born August 29, 1967) is an American jurist who serves as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. He was Neil Gorsuch Supreme Court ...

,

Brett Kavanaugh

Brett Michael Kavanaugh (; born February 12, 1965) is an American lawyer and jurist serving as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. He was nominated by President Donald Trump on July 9, 2018, and has served since Oct ...

, and

Amy Coney Barrett

Amy Vivian Coney Barrett (born January 28, 1972) is an American lawyer and jurist serving since 2020 as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. The fifth wom ...

. He was impeached by the House of Representatives in 2019 on charges of abuse of power and obstruction of Congress but was acquitted by the Senate in 2020. Trump lost the

2020 presidential election to

Joe Biden

Joseph Robinette Biden Jr. (born November 20, 1942) is an American politician who was the 46th president of the United States from 2021 to 2025. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he served as the 47th vice p ...

but refused to concede the race, claiming widespread electoral fraud and

attempting to overturn the results. On January 6, 2021, the

United States Capitol was attacked by Trump supporters following a rally at which Trump spoke. After the attack, the House

impeached Trump for a second time on the charge of

incitement of insurrection, making him the only federal officeholder to be impeached twice. The Senate

acquitted him in February 2021, after he had already left office. Following the 2020 election,

election denial became increasingly mainstream in the party,

with the majority of Republican candidates in 2022 being election deniers.

The party also made

efforts to restrict voting based on false claims of fraud. By 2020, the Republican Party had greatly shifted towards

illiberalism Historically, the adjective illiberal has been mostly applied to personal attitudes, behaviors and practices “unworthy of a free man”, such as lack of generosity, lack of sophisticated culture, intolerance, narrow-mindedness, meanness. Lord Ches ...

following the election of Trump, and research conducted by the

V-Dem Institute

The V-Dem Institute (an abbreviation of Varieties of Democracy Institute), founded by Staffan I. Lindberg in 2014, is an independent research institute that serves as the headquarters of the V-Dem Project, a database that seeks to conceptualize ...

concluded that the party was more similar to Europe's most right-wing parties such as

Law and Justice

Law and Justice ( , PiS) is a Right-wing populism, right-wing populist and National conservatism, national-conservative List of political parties in Poland, political party in Poland. The party is a member of European Conservatives and Refo ...

in Poland or

Fidesz

Fidesz – Hungarian Civic Alliance (; ) is a national-conservative political party in Hungary led by Viktor Orbán. It has increasingly identified as illiberal.

Originally formed in 1988 under the name of Alliance of Young Democrats () as ...

in Hungary.

The party went into the

2022 elections confident and with analysts predicting a

red wave, but it underperformed expectations, with voters in

swing state

In United States politics, a swing state (also known as battleground state, toss-up state, or purple state) is any state that could reasonably be won by either the Democratic or Republican candidate in a statewide election, most often refe ...

s and competitive districts joining Democrats in rejecting candidates who had been endorsed by Trump or who had denied the results of the 2020 election.

The party won control of the House with a narrow majority,

but lost the Senate and several state legislative majorities and governorships.

["State Partisan Composition"](_blank)

May 23, 2023, National Conference of State Legislatures

The National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL), established in 1975, is a "nonpartisan public officials' association composed of sitting state legislators" from the states, territories and commonwealths of the United States.

Background ...

, retrieved July 4, 2023. .[ Cronin, Tom and Bob Loevy]

"American federalism: States veer far left or far right"

, July 1, 2023, updated July 2, 2023, ''Colorado Springs Gazette

''The Gazette'' is a daily newspaper based in Colorado Springs, Colorado, United States. It has operated since 1873.

History

The publication began as ''Out West'', beginning March 23, 1872, but failed in its endeavor. The company relaunched ...

,'' retrieved July 4, 2023["In the States, Democrats All but Ran the Table"](_blank)

November 11, 2022, ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

,'' retrieved July 4, 2023 The results led to a number of Republicans and conservative thought leaders questioning whether Trump should continue as the party's main figurehead and leader.

Despite those disappointments, Trump

easily won the nomination to be the party's candidate again in

2024

The year saw the list of ongoing armed conflicts, continuation of major armed conflicts, including the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Myanmar civil war (2021–present), Myanmar civil war, the Sudanese civil war (2023–present), Sudane ...

, marking the third straight election of him being the GOP nominee. Trump – who survived an ear injury in

an assassination attempt during the campaign – achieved victory against Vice President

Kamala Harris

Kamala Devi Harris ( ; born October 20, 1964) is an American politician and attorney who served as the 49th vice president of the United States from 2021 to 2025 under President Joe Biden. She is the first female, first African American, and ...

, who replaced President Biden on the Democratic ticket after his withdrawal in July. He won both the

electoral college

An electoral college is a body whose task is to elect a candidate to a particular office. It is mostly used in the political context for a constitutional body that appoints the head of state or government, and sometimes the upper parliament ...

and popular vote, becoming the first Republican to do so since George W. Bush in 2004, and improving his vote share among

working class

The working class is a subset of employees who are compensated with wage or salary-based contracts, whose exact membership varies from definition to definition. Members of the working class rely primarily upon earnings from wage labour. Most c ...

voters, particularly among young men, those without college degrees, and

Hispanic

The term Hispanic () are people, Spanish culture, cultures, or countries related to Spain, the Spanish language, or broadly. In some contexts, Hispanic and Latino Americans, especially within the United States, "Hispanic" is used as an Ethnici ...

voters. The Republicans also held a slim majority in the House and retook control of the Senate, securing the party's first

trifecta

Trifecta

A trifecta is a parimutuel bet placed on a horse race in which the bettor must predict which horses will finish first, second, and third, in the exact order. Known as a trifecta in the US and Australia, this is known as a tricast in ...

since 2017.

Current status

As of , the GOP holds the presidency, and majorities in both the

U.S. House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Article One of th ...

and

U.S. Senate

The United States Senate is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and House have the authority under Article One of the ...

, giving them a federal

government trifecta

A government trifecta is a political situation in which the same political party controls the Executive (government), executive branch and both chambers of the legislative branch in countries that have a Bicameralism, bicameral legislature and a ...

. It also holds 27

state governorships, 28

state legislatures, and 23 state government trifectas. Six of the nine current

U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that turn on question ...

justices were appointed by Republican presidents, three of them were appointed by Trump. There have been 19 Republicans who have served as president, the most from any one political party, the most recent being current president

Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who is the 47th president of the United States. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he served as the 45 ...

, who became the 47th president on January 20, 2025. Trump also served as the 45th president from 2017 to 2021.

Name and symbols

The Republican Party's founding members chose its name as homage to the values of

republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology that encompasses a range of ideas from civic virtue, political participation, harms of corruption, positives of mixed constitution, rule of law, and others. Historically, it emphasizes the idea of self ...

promoted by Democratic-Republican Party, which its founder, Thomas Jefferson, called the "Republican Party".

The idea for the name came from an editorial by the party's leading publicist, Horace Greeley, who called for "some simple name like 'Republican'

hat

A hat is a Headgear, head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorpor ...

would more fitly designate those who had united to restore the Union to its true mission of champion and promulgator of Liberty rather than propagandist of slavery".

The name reflects the 1776 republican values of civic virtue and opposition to aristocracy and corruption.

[Gould, pp. 14–15] "Republican" has a variety of meanings around the world, and the Republican Party has evolved such that the meanings no longer always align.

The term "Grand Old Party" is a traditional nickname for the Republican Party, and the abbreviation "GOP" is a commonly used designation. The term originated in 1875 in the ''

Congressional Record

The ''Congressional Record'' is the official record of the proceedings and debates of the United States Congress, published by the United States Government Publishing Office and issued when Congress is in session. The Congressional Record Ind ...

'', referring to the party associated with the successful military defense of the Union as "this gallant old party". The following year in an article in the ''

Cincinnati Commercial

The ''Cincinnati Commercial Tribune'' was a major daily newspaper in Cincinnati, Ohio, formed in 1896, and folded in 1930.(3 December 1930)OLDEST NEWSPAPER IN CINCINNATI QUITS; Commercial Tribune Stopped by McLean Interests After Political Shift ...

'', the term was modified to "grand old party". The first use of the abbreviation is dated 1884.

The traditional mascot of the party is the elephant. A political cartoon by

Thomas Nast

Thomas Nast (; ; September 26, 1840December 7, 1902) was a German-born American caricaturist and editorial cartoonist often considered to be the "Father of the American Cartoon".

He was a sharp critic of William M. Tweed, "Boss" Tweed and the T ...

, published in ''

Harper's Weekly

''Harper's Weekly, A Journal of Civilization'' was an American political magazine based in New York City. Published by Harper (publisher), Harper & Brothers from 1857 until 1916, it featured foreign and domestic news, fiction, essays on many su ...

'' on November 7, 1874, is considered the first important use of the symbol.

The cartoon was published during the debate over

a third term for President Ulysses S. Grant. It draws imagery and text from the

Aesop

Aesop ( ; , ; c. 620–564 BCE; formerly rendered as Æsop) was a Greeks, Greek wikt:fabulist, fabulist and Oral storytelling, storyteller credited with a number of fables now collectively known as ''Aesop's Fables''. Although his existence re ...

fable "

The Ass in the Lion's Skin", combined with rumors of animals escaping from the

Central Park Zoo

The Central Park Zoo is a zoo located at the southeast corner of Central Park in New York City. It is part of an integrated system of four zoos and one aquarium managed by the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS). In conjunction with the Centra ...

.

An alternate symbol of the Republican Party in states such as Indiana, New York and Ohio is the bald eagle as opposed to the Democratic rooster or the Democratic five-pointed star. In

Kentucky

Kentucky (, ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north, West Virginia to the ...

, the

log cabin

A log cabin is a small log house, especially a minimally finished or less architecturally sophisticated structure. Log cabins have an ancient history in Europe, and in America are often associated with first-generation home building by settl ...

is a symbol of the Republican Party.

Traditionally the party had no consistent color identity. After the 2000 presidential election, the color

red became associated with Republicans. During and after the election, the major broadcast networks used the same color scheme for the electoral map: states won by Republican nominee George W. Bush were colored red and states won by Democratic nominee

Al Gore

Albert Arnold Gore Jr. (born March 31, 1948) is an American former politician, businessman, and environmentalist who served as the 45th vice president of the United States from 1993 to 2001 under President Bill Clinton. He previously served as ...

were colored blue. Due to the weeks-long

dispute over the election results, these color associations became firmly ingrained, persisting in subsequent years. Although the assignment of colors to political parties is unofficial and informal, the media has come to represent the respective political parties using these colors. The party and its candidates have also come to embrace the color red.

File:NastRepublicanElephant.jpg, An 1874 cartoon by Thomas Nast

Thomas Nast (; ; September 26, 1840December 7, 1902) was a German-born American caricaturist and editorial cartoonist often considered to be the "Father of the American Cartoon".

He was a sharp critic of William M. Tweed, "Boss" Tweed and the T ...

, featuring the first notable appearance of the Republican elephant

Factions

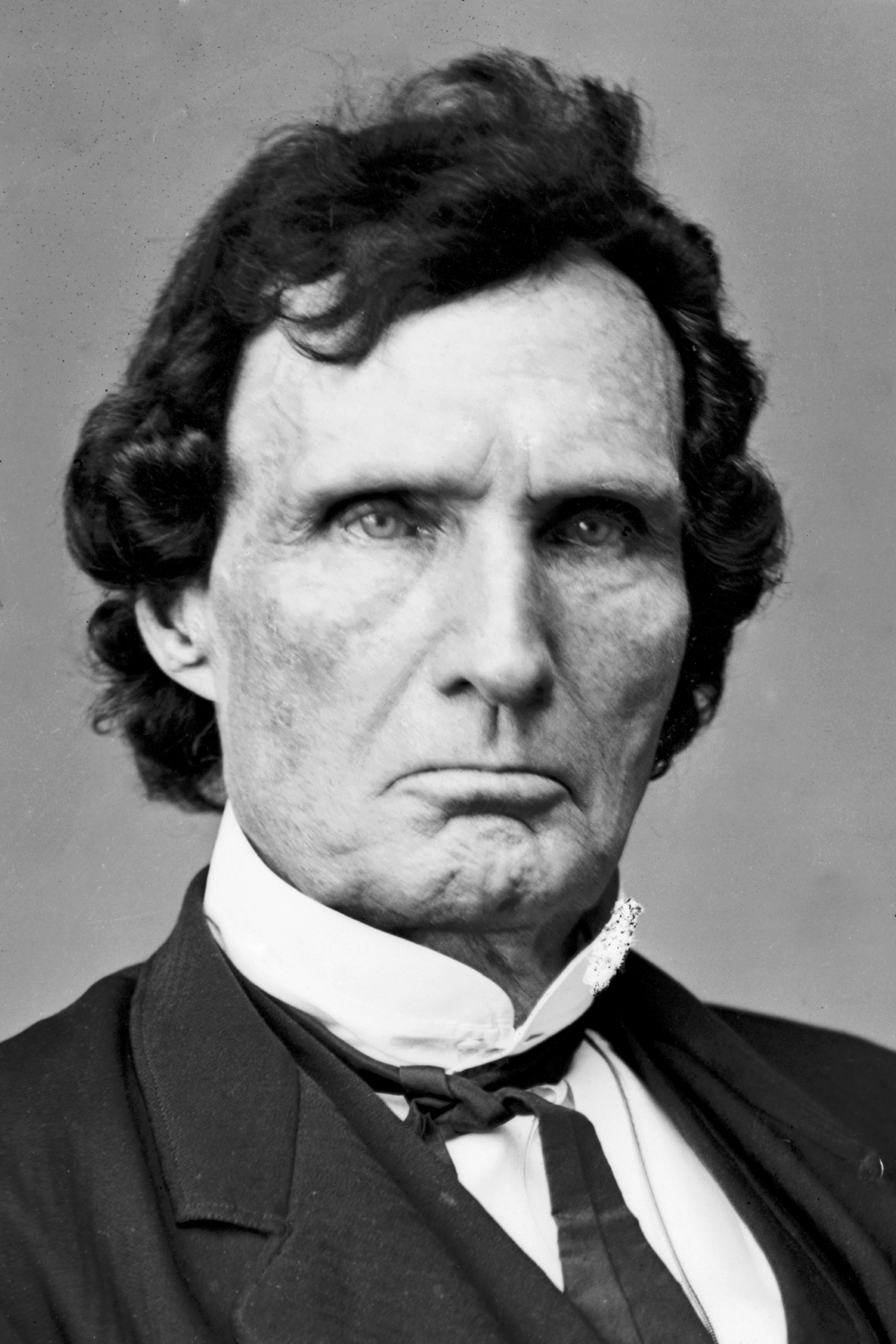

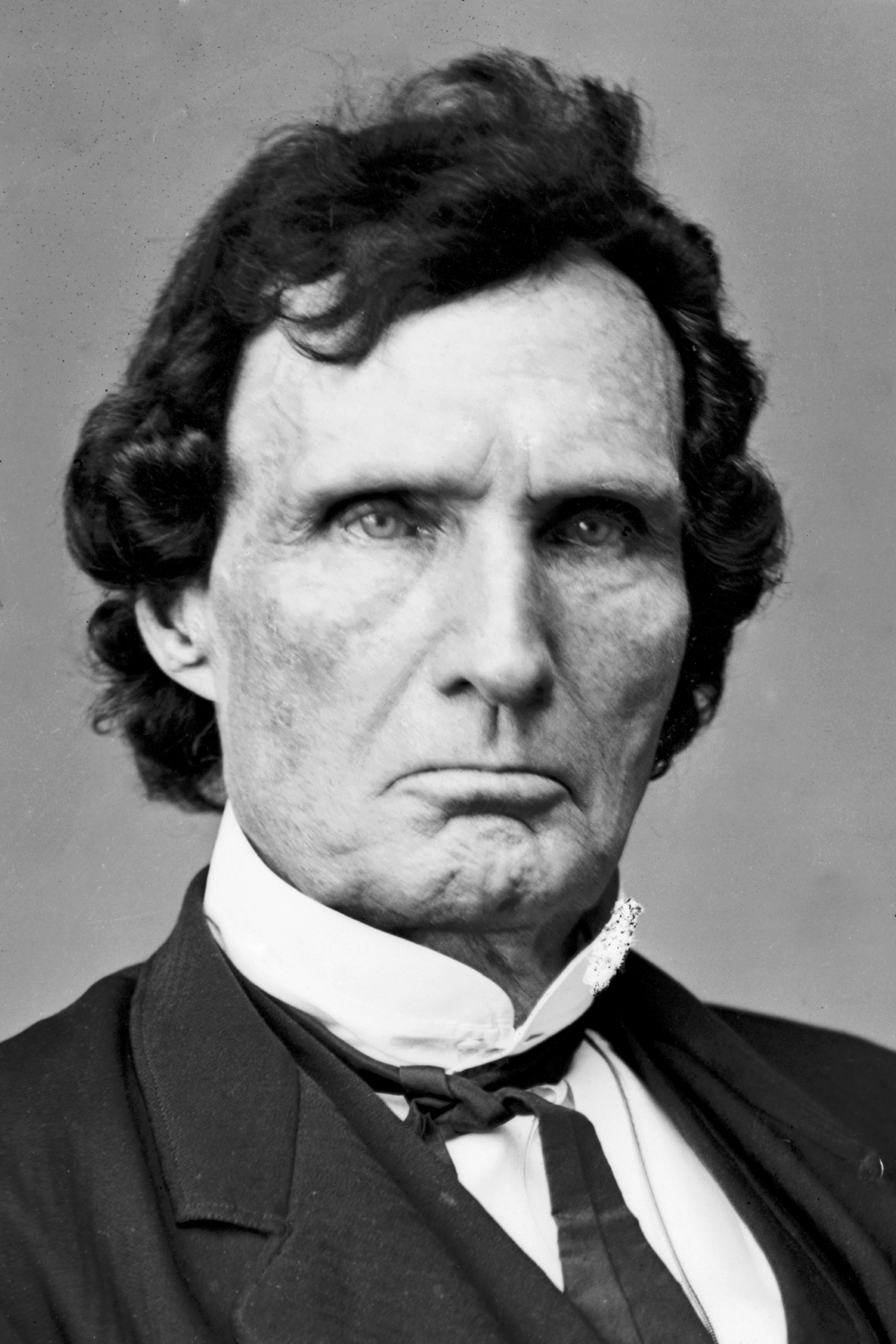

Civil War and Reconstruction era

The

Radical Republicans

The Radical Republicans were a political faction within the Republican Party originating from the party's founding in 1854—some six years before the Civil War—until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Reconstruction. They ca ...

were a major factor of the party from its inception in 1854 until the end of the

Reconstruction Era

The Reconstruction era was a period in History of the United States, US history that followed the American Civil War (1861-65) and was dominated by the legal, social, and political challenges of the Abolitionism in the United States, abol ...

in 1877. They strongly opposed

slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

, were hard-line

abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was France in 1315, but it was later used in its colonies. T ...

, and later advocated equal rights for the

freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, slaves were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their owners), emancipation (granted freedom as part of a larger group), or self- ...

and women. They were heavily influenced by religious ideals and

evangelical Christianity

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide, interdenominational movement within Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that emphasizes evangelism, or the preaching and spreading of th ...

.

Radical Republicans pressed for abolition as a major war aim and they opposed the moderate Reconstruction plans of Abraham Lincoln as both too lenient on the

Confederates and not going far enough to help former slaves. After the war's end and Lincoln's assassination, the Radicals clashed with

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. The 16th vice president, he assumed the presidency following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a South ...

over Reconstruction policy. Radicals led efforts to establish civil rights for former slaves and fully implement emancipation, pushing the

Fourteenth Amendment for statutory protections through

Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

. They opposed allowing ex-

Confederate officers to retake political power in the

Southern U.S., and emphasized liberty, equality, and the

Fifteenth Amendment which provided

voting rights

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise is the right to vote in representative democracy, public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in ...

for the

freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, slaves were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their owners), emancipation (granted freedom as part of a larger group), or self- ...

. Many later became

Stalwarts, who supported machine politics.

Moderate Republicans were known for their loyal support of President

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

's war policies and expressed antipathy towards the more militant stances advocated by the Radical Republicans. In contrast to Radicals, Moderate Republicans were less enthusiastic on the issue of Black suffrage even while embracing civil equality and the expansive federal authority observed throughout the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

. They were also skeptical of the lenient, conciliatory Reconstruction policies of President Andrew Johnson. Members of the Moderate Republicans comprised in part of previous Radical Republicans who became disenchanted with the alleged corruption of the latter faction. They generally opposed efforts by Radical Republicans to rebuild the Southern U.S. under an economically mobile,

free-market

In economics, a free market is an economic system in which the prices of goods and services are determined by supply and demand expressed by sellers and buyers. Such markets, as modeled, operate without the intervention of government or any ot ...

system.

20th century

The 20th century saw the Republican party split into an

Old Right and a moderate-liberal faction in the Northeast that eventually became known as

Rockefeller Republicans. Opposition to Roosevelt's

New Deal

The New Deal was a series of wide-reaching economic, social, and political reforms enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1938, in response to the Great Depression in the United States, Great Depressi ...

saw the formation of the

conservative coalition

The conservative coalition, founded in 1937, was an unofficial alliance of members of the United States Congress which brought together the conservative wings of the Republican and Democratic parties to oppose President Franklin Delano Rooseve ...

.

The 1950s saw

fusionism

In American politics, fusionism is the philosophical and political combination or "fusion" of traditionalist and social conservatism with political and economic right-libertarianism. Fusionism combines "free markets, social conservatism, and a ...

of traditionalist and social conservatism and right-libertarianism,

along with the rise of the

First New Right to be followed in 1964 with a more populist

Second New Right.

The rise of the

Reagan coalition in the 1980s began what has been called the

Reagan era. Reagan's rise displaced the liberal-moderate faction of the GOP and established Reagan-style conservatism as the prevailing ideological faction of the Party for the next thirty years, until the rise of the

right-wing populist

Right-wing populism, also called national populism and right populism, is a political ideology that combines right-wing politics with populist rhetoric and themes. Its rhetoric employs anti- elitist sentiments, opposition to the Establishm ...

faction.

Reagan conservatives generally supported policies that favored

limited government

In political philosophy, limited government is the concept of a government limited in power. It is a key concept in the history of liberalism.Amy Gutmann, "How Limited Is Liberal Government" in Liberalism Without Illusions: Essays on Liberal ...

,

individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote realizing one's goals and desires, valuing independence and self-reliance, and a ...

,

tradition

A tradition is a system of beliefs or behaviors (folk custom) passed down within a group of people or society with symbolic meaning or special significance with origins in the past. A component of cultural expressions and folklore, common e ...

alism,

republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology that encompasses a range of ideas from civic virtue, political participation, harms of corruption, positives of mixed constitution, rule of law, and others. Historically, it emphasizes the idea of self ...

, and limited

federal governmental power

in relation to

the states.

21st century

Republicans began the 21st century with the election of

George W. Bush

George Walker Bush (born July 6, 1946) is an American politician and businessman who was the 43rd president of the United States from 2001 to 2009. A member of the Bush family and the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he i ...

in the

2000 United States presidential election

United States presidential election, Presidential elections were held in the United States on November 7, 2000. Republican Party (United States), Republican Governor George W. Bush of Texas, the eldest son of 41st President George H. W. Bush, ...

and saw the peak of a

neoconservative

Neoconservatism (colloquially neocon) is a political movement which began in the United States during the 1960s among liberal hawks who became disenchanted with the increasingly pacifist Democratic Party along with the growing New Left and ...

faction that held significant influence over the initial American response to the

September 11 attacks

The September 11 attacks, also known as 9/11, were four coordinated Islamist terrorist suicide attacks by al-Qaeda against the United States in 2001. Nineteen terrorists hijacked four commercial airliners, crashing the first two into ...

through the

War on Terror.

The election of

Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II (born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who was the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, he was the first African American president in American history. O ...

saw the formation of the

Tea Party movement

The Tea Party movement was an American fiscally conservative political movement within the Republican Party that began in 2007, catapulted into the mainstream by Congressman Ron Paul's presidential campaign. The movement expanded in resp ...

in 2009 that coincided with a global rise in

right-wing populist

Right-wing populism, also called national populism and right populism, is a political ideology that combines right-wing politics with populist rhetoric and themes. Its rhetoric employs anti- elitist sentiments, opposition to the Establishm ...

movements from the 2010s to 2020s.

The global rise in right-wing populism has been attributed to factors including higher educational attainment, a decline in organized religion, backlash to globalization, and

migrant crises.

Right-wing populism became an increasingly dominant ideological faction within the GOP throughout the 2010s and helped lead to the election of

Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who is the 47th president of the United States. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he served as the 45 ...

in 2016.

Starting in the 1970s and accelerating in the 2000s, American right-wing interest groups invested heavily in external mobilization vehicles that led to the organizational weakening of the GOP establishment. The outsize role of conservative media, in particular

Fox News

The Fox News Channel (FNC), commonly known as Fox News, is an American Multinational corporation, multinational Conservatism in the United States, conservative List of news television channels, news and political commentary Television stati ...

, led to it being followed and trusted more by the Republican base over traditional party elites. The depletion of organizational capacity partly led to Trump's victory in the Republican primaries against the wishes of a very weak party establishment and traditional power brokers.

Trump's election exacerbated internal schisms within the GOP,

and saw the GOP move from a center coalition of moderates and conservatives to a solidly right-wing party hostile to liberal views and any deviations from the party line.

The Party has since faced intense factionalism. These factions are particularly apparent in the

U.S. House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Article One of th ...

, where three Republican House leaders (

Eric Cantor

Eric Ivan Cantor (born June 6, 1963) is an American lawyer and former politician who represented Virginia's 7th congressional district in the United States House of Representatives from 2001 to 2014. A Republican, Cantor served as House Mino ...

,

John Boehner

John Andrew Boehner ( ; born , 1949) is an American politician who served as the 53rd speaker of the United States House of Representatives from 2011 to 2015. A member of the Republican Party, he served 13 terms as the U.S. representative ...

, and

Kevin McCarthy

Kevin Owen McCarthy (born January 26, 1965) is an American politician who served as the List of speakers of the United States House of Representatives, 55th speaker of the United States House of Representatives from January until he was Remova ...

) have been ousted since 2009.

All three of the top Republican elected officials during Trump's first term (Vice President, Speaker of the House, and Senate Republican leader) were ousted or stepped down by Trump's second term.

The party's

establishment conservative faction has lost all of its influence.

Many conservatives critical of the Trumpist faction have also lost influence within the party, with no former Republican presidential or vice presidential nominees attending the

2024 Republican National Convention

The 2024 Republican National Convention was an event in which delegates of the Republican Party (United States), United States Republican Party selected the party's nominees for President of the United States, president and Vice President of ...

.

The victory of Trump in the 2024 presidential election saw the party increasingly shift towards

Trumpism

Trumpism, also referred to as the Make America Great Again (MAGA) movement, is the political movement and ideology behind U.S. president Donald Trump and his political base. It comprises ideologies such as right-wing populism, right-wing ...

,

and party criticism of Trump was described as being muted to non-existent. ''The New York Times'' described it as a "hostile takeover",

and a victory of right-wing populism over the old conservative establishment.

Polling found that 53% of Republican voters saw loyalty to Trump as central to their political identity and what it means to be a Republican.

During Trump's second presidency, Republican members of Congress were described by ''

The New Republic

''The New Republic'' (often abbreviated as ''TNR'') is an American magazine focused on domestic politics, news, culture, and the arts from a left-wing perspective. It publishes ten print magazines a year and a daily online platform. ''The New Y ...

'' magazine as submissive to Trump, letting him dictate policies without pushback.

Right-wing populists

Right-wing populism

Right-wing populism, also called national populism and right populism, is a political ideology that combines right-wing politics with populist rhetoric and themes. Its rhetoric employs anti- elitist sentiments, opposition to the Establis ...

is the dominant political faction of the GOP. Sometimes referred to as the

MAGA

"Make America Great Again" (MAGA, ) is an American political slogan most recently popularized by Donald Trump during Donald Trump 2016 presidential campaign, his successful presidential campaigns in 2016 and Donald Trump 2024 presidential cam ...

or "

America First" movement,

Republican populists have been described as consisting of a range of right-wing ideologies including but not limited to right-wing populism,

national conservatism

National conservatism is a nationalist variant of conservatism that concentrates on upholding national and cultural identity, communitarianism and the public role of religion. It shares aspects of traditionalist conservatism and social conserv ...

,

neo-nationalism

Neo-nationalism, or new nationalism, is an ideology and political movement built on the basic characteristics of classical nationalism. It developed to its final form by applying elements with reactionary character generated as a reaction to t ...

,

mercantilism

Mercantilism is a economic nationalism, nationalist economic policy that is designed to maximize the exports and minimize the imports of an economy. It seeks to maximize the accumulation of resources within the country and use those resources ...

,

and

Trumpism

Trumpism, also referred to as the Make America Great Again (MAGA) movement, is the political movement and ideology behind U.S. president Donald Trump and his political base. It comprises ideologies such as right-wing populism, right-wing ...

.

Trump has been described as one of many nationalist leaders, including

Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin (born 7 October 1952) is a Russian politician and former intelligence officer who has served as President of Russia since 2012, having previously served from 2000 to 2008. Putin also served as Prime Minister of Ru ...

of Russia,

Xi Jinping

Xi Jinping, pronounced (born 15 June 1953) is a Chinese politician who has been the general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and Chairman of the Central Military Commission (China), chairman of the Central Military Commission ...

of China,

Recep Tayyip Erdogan

Recep is a Turkish name deriving from the Arabic name Rajab. It may refer to:

People Surname

* Aziz Recep (born 1992), German-Greek footballer

* Sibel Recep (born 1987), Swedish pop singer

Given name

* Recep Adanır (1929–2017), Turkish fo ...

of Turkey,

Narendra Modi

Narendra Damodardas Modi (born 17 September 1950) is an Indian politician who has served as the Prime Minister of India, prime minister of India since 2014. Modi was the chief minister of Gujarat from 2001 to 2014 and is the Member of Par ...

of India,

Mohammed bin Salman

Mohammed bin Salman Al Saud (; born 31 August 1985), also known as MBS or MbS, is the ''de facto'' ruler of the Saudi Arabia, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, formally serving as Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia, Crown Prince and Prime Minister of Sa ...

of Saudi Arabia,

Viktor Orbán

Viktor Mihály Orbán (; born 31 May 1963) is a Hungarian lawyer and politician who has been the 56th prime minister of Hungary since 2010, previously holding the office from 1998 to 2002. He has also led the Fidesz political party since 200 ...

of Hungary and

Benjamin Netanyahu

Benjamin Netanyahu (born 21 October 1949) is an Israeli politician who has served as the prime minister of Israel since 2022, having previously held the office from 1996 to 1999 and from 2009 to 2021. Netanyahu is the longest-serving prime min ...

of Israel.

The Republican Party's right-wing populist movements emerged in concurrence with a global increase in populist movements in the 2010s and 2020s,

coupled with entrenchment and increased partisanship within the party since 2010.

This included the rise of the

Tea Party movement

The Tea Party movement was an American fiscally conservative political movement within the Republican Party that began in 2007, catapulted into the mainstream by Congressman Ron Paul's presidential campaign. The movement expanded in resp ...

, which has also been described as

far-right

Far-right politics, often termed right-wing extremism, encompasses a range of ideologies that are marked by ultraconservatism, authoritarianism, ultranationalism, and nativism. This political spectrum situates itself on the far end of the ...

.

This faction gained further dominance in the GOP during

Joe Biden's presidency (2021-2025), including in the aftermath of the

2021-2023 inflation surge and

Russian invasion of Ukraine

On 24 February 2022, , starting the largest and deadliest war in Europe since World War II, in a major escalation of the Russo-Ukrainian War, conflict between the two countries which began in 2014. The fighting has caused hundreds of thou ...

.

Businessman

Elon Musk

Elon Reeve Musk ( ; born June 28, 1971) is a businessman. He is known for his leadership of Tesla, SpaceX, X (formerly Twitter), and the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE). Musk has been considered the wealthiest person in th ...

, the wealthiest individual in the world, is a notable proponent of right-wing populism. Since acquiring Twitter in 2022, Musk has shared far-right misinformation and numerous

conspiracy theories

A conspiracy theory is an explanation for an event or situation that asserts the existence of a conspiracy (generally by powerful sinister groups, often political in motivation), when other explanations are more probable.Additional sources:

*

...

, and his views are described as right-wing to far-right. However, Musk has also been described as in conflict with the populist wing of the party on some issues, particularly

legal immigration,

government spending

Government spending or expenditure includes all government consumption, investment, and transfer payments. In national income accounting, the acquisition by governments of goods and services for current use, to directly satisfy the individual or ...

,

free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold Economic liberalism, economically liberal positions, while economic nationalist politica ...

and

relations with China.

According to political scientists Matt Grossmann and David A. Hopkins, the Republican Party's gains among white voters without college degrees and corresponding losses among white voters with college degrees contributed to the rise of right-wing populism.

Until 2016, white voters with college degrees were a Republican-leaning group, but have since become a Democratic-leaning group.

In the

2020 presidential election,

Joe Biden

Joseph Robinette Biden Jr. (born November 20, 1942) is an American politician who was the 46th president of the United States from 2021 to 2025. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he served as the 47th vice p ...

became the first Democratic president to win a majority of white voters with college degrees (51–48%) since

1964

Events January

* January 1 – The Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland is dissolved.

* January 5 – In the first meeting between leaders of the Roman Catholic and Orthodox churches since the fifteenth century, Pope Paul VI and Patria ...

, while Trump won white voters without college degrees 67–32%.

Right-wing populism has broad appeal across income and wealth,

and is extremely polarized with respect to educational attainment among White voters. According to a 2017 study, agreement with Trump on social issues, rather than economic pressure, increased support for Trump among White voters without college degrees. White voters without college degrees who were economically struggling were more likely to vote for Democrats and support the Democratic party's economic agenda. Right-wing populism has appeal to

Hispanic

The term Hispanic () are people, Spanish culture, cultures, or countries related to Spain, the Spanish language, or broadly. In some contexts, Hispanic and Latino Americans, especially within the United States, "Hispanic" is used as an Ethnici ...

and

Asian voters, but has little appeal to African American voters.

According to historian

Gary Gerstle, Trumpism gained support in opposition to

neoliberalism

Neoliberalism is a political and economic ideology that advocates for free-market capitalism, which became dominant in policy-making from the late 20th century onward. The term has multiple, competing definitions, and is most often used pe ...

,

including opposition to

free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold Economic liberalism, economically liberal positions, while economic nationalist politica ...

,

immigration

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not usual residents or where they do not possess nationality in order to settle as Permanent residency, permanent residents. Commuting, Commuter ...

,

globalization

Globalization is the process of increasing interdependence and integration among the economies, markets, societies, and cultures of different countries worldwide. This is made possible by the reduction of barriers to international trade, th ...

,

and

internationalism.

Trump won the 2016 and 2024 presidential elections by winning states in the

Rust Belt

The Rust Belt, formerly the Steel Belt or Factory Belt, is an area of the United States that underwent substantial Deindustrialization, industrial decline in the late 20th century. The region is centered in the Great Lakes and Mid-Atlantic (Uni ...

that had suffered from

population decline

Population decline, also known as depopulation, is a reduction in a human population size. Throughout history, Earth's total world population, human population has estimates of historical world population, continued to grow but projections sugg ...

and

deindustrialization

Deindustrialization is a process of social and economic change caused by the removal or reduction of industrial capacity or activity in a country or region, especially of heavy industry or manufacturing industry.

There are different interpr ...

.

Compared to other Republicans, the populist faction is more likely to oppose

legal immigration,

free trade,

neoconservatism

Neoconservatism (colloquially neocon) is a political movement which began in the United States during the 1960s among liberal hawks who became disenchanted with the increasingly pacifist Democratic Party along with the growing New Left and ...

, and

environmental protection laws. It has been described as featuring

anti-intellectualism

Anti-intellectualism is hostility to and mistrust of intellect, intellectuals, and intellectualism, commonly expressed as deprecation of education and philosophy and the dismissal of art, literature, history, and science as impractical, politica ...

and overtly racial appeals.

In international relations, populists support U.S. aid to Israel but not to Ukraine.

They are generally supportive of improving

relations with Russia,

and favor an

isolationist "

America First" foreign policy agenda.

This faction has been described as closer to that of Vladimir Putin’s Russia and Recep Tayyip Erdogan's Turkey than

Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

and the

Anglosphere

The Anglosphere, also known as the Anglo-American world, is a Western-led sphere of influence among the Anglophone countries. The core group of this sphere of influence comprises five developed countries that maintain close social, cultura ...

in terms of positions on international cooperation, support for an autocratic leadership style, and trust in institutions.

This faction takes nationalist and

irredentist

Irredentism () is one state's desire to annex the territory of another state. This desire can be motivated by ethnic reasons because the population of the territory is ethnically similar to or the same as the population of the parent state. Hist ...

views towards other countries in North America, advocating for U.S. territorial expansion to include

Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

,

Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

and the

Panama Canal

The Panama Canal () is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Caribbean Sea with the Pacific Ocean. It cuts across the narrowest point of the Isthmus of Panama, and is a Channel (geography), conduit for maritime trade between th ...

, the renaming of the

Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico () is an oceanic basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, mostly surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north, and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States; on the southw ...

, and potential military action on Mexican soil.

The party's far-right faction includes members of the

Freedom Caucus

The Freedom Caucus, also known as the House Freedom Caucus, is a congressional caucus consisting of Republican Party (United States), Republican members of the United States House of Representatives. It is generally considered to be the most Cons ...

.

They generally reject compromise within the party and with the

Democrats,

and are willing to oust fellow Republican office holders they deem to be too moderate.

According to sociologist

Joe Feagin

Joe Richard Feagin (; born May 6, 1938) is an American sociologist and social theorist who has conducted extensive research on racial and gender issues in the United States. He is currently the Ella C. McFadden Distinguished Professor at Texas A& ...

, political polarization by racially extremist Republicans as well as their increased attention from conservative media has perpetuated the near extinction of moderate Republicans and created legislative paralysis at numerous government levels in the last few decades.

Julia Azari, an associate professor of political science at

Marquette University

Marquette University () is a Private university, private Jesuit research university in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, United States. It was established as Marquette College on August 28, 1881, by John Henni, the first Archbishop of the Roman Catholic Ar ...

, noted that not all populist Republicans are public supporters of Donald Trump, and that some Republicans such as

Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin

Glenn Allen Youngkin (born December 9, 1966) is an American politician and businessman serving as the 74th governor of Virginia since 2022. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he spent 25 years at the Private equi ...

endorse Trump policies while distancing themselves from Trump as a person.

The continued dominance of Trump within the GOP has limited the success of this strategy.

In 2024, Trump led a takeover of the

Republican National Committee

The Republican National Committee (RNC) is the primary committee of the Republican Party of the United States. Its members are chosen by the state delegations at the national convention every four years. It is responsible for developing and pr ...

.

A ''

FiveThirtyEight

''FiveThirtyEight'', also rendered as ''538'', was an American website that focused on opinion poll analysis, politics, economics, and sports blogging in the United States.

The website, which took its name from the number of electors in the U ...

'' analysis found that of the 293 Republican members of Congress on January 20, 2017, just 121 (41%) were left on January 20, 2025. There were many reasons for the turnover, including retirements and deaths, losing general and primary elections, seeking other office, etc., but the extent of the change is still stark. There were 273 Republican members of Congress on January 20, 2025. Trump also changed his vice president and both houses of Congress had changed their top leadership.

Conservatives

Ronald Reagan's presidential election in

1980

Events January

* January 4 – U.S. President Jimmy Carter proclaims a United States grain embargo against the Soviet Union, grain embargo against the USSR with the support of the European Commission.

* January 6 – Global Positioning Sys ...

established Reagan-style

American conservatism

Conservatism in the United States is one of two major political ideologies in the United States, with the other being liberalism. Traditional American conservatism is characterized by a belief in individualism, traditionalism, capitalism, ...

as the dominant ideological faction of the Republican Party until the election of Donald Trump in 2016. Trump's 2016 election split both the GOP and larger conservative movement into

Trumpist and

anti-Trump factions, with the Trumpist faction winning.

According to

Nate Silver