Underground Paper on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The terms underground press or clandestine press refer to periodicals and publications that are produced without official approval, illegally or against the wishes of a dominant (governmental, religious, or institutional) group.

In specific recent (post-World War II) Asian, American and Western European context, the term "underground press" has most frequently been employed to refer to the independently published and distributed underground papers associated with the

The terms underground press or clandestine press refer to periodicals and publications that are produced without official approval, illegally or against the wishes of a dominant (governmental, religious, or institutional) group.

In specific recent (post-World War II) Asian, American and Western European context, the term "underground press" has most frequently been employed to refer to the independently published and distributed underground papers associated with the

In Western Europe, a century after the invention of the printing press, a widespread underground press emerged in the mid-16th century with the clandestine circulation of

In Western Europe, a century after the invention of the printing press, a widespread underground press emerged in the mid-16th century with the clandestine circulation of

' s broadsheet format). Very quickly, the relaunched ''Oz'' shed its more austere satire magazine image and became a mouthpiece of the underground. It was the most colourful and visually adventurous of the alternative press (sometimes to the point of near-illegibility), with designers like

"The Underground Press and Its Extraordinary Moment in US History,"

''

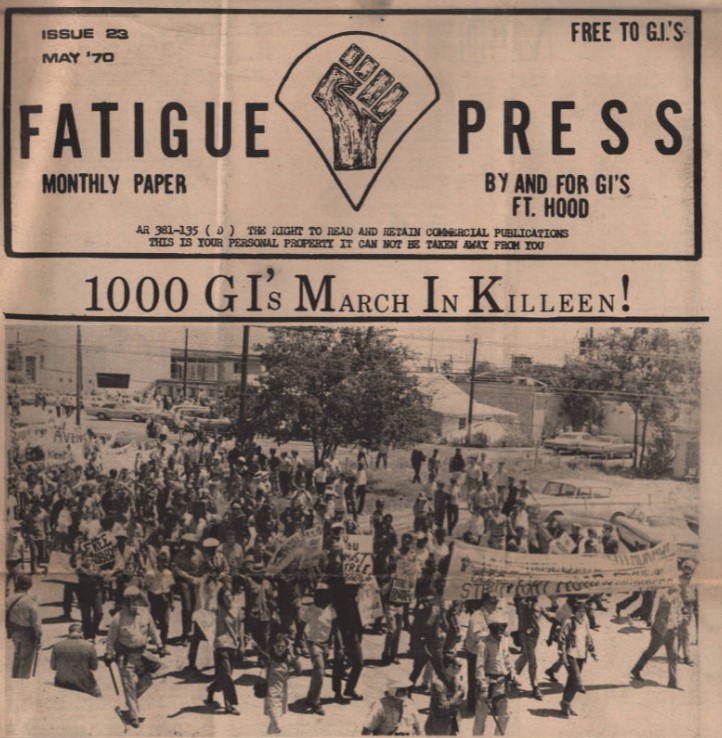

The GI underground press within the U.S. military produced over four hundred titles during the Vietnam War, some produced by antiwar

The GI underground press within the U.S. military produced over four hundred titles during the Vietnam War, some produced by antiwar

University of Missouri Libraries. Accessed Dec. 29, 2016. The Rip Off Press Syndicate was launched 1973 to compete in selling underground comix content to the underground press and

"Rip Off Comix — 1977-1991 / Rip Off Press,"

Comixjoint. Retrieved Dec. 5, 2022. Each Friday, the company sent out a distribution sheet with the strips it was selling, by such cartoonists as

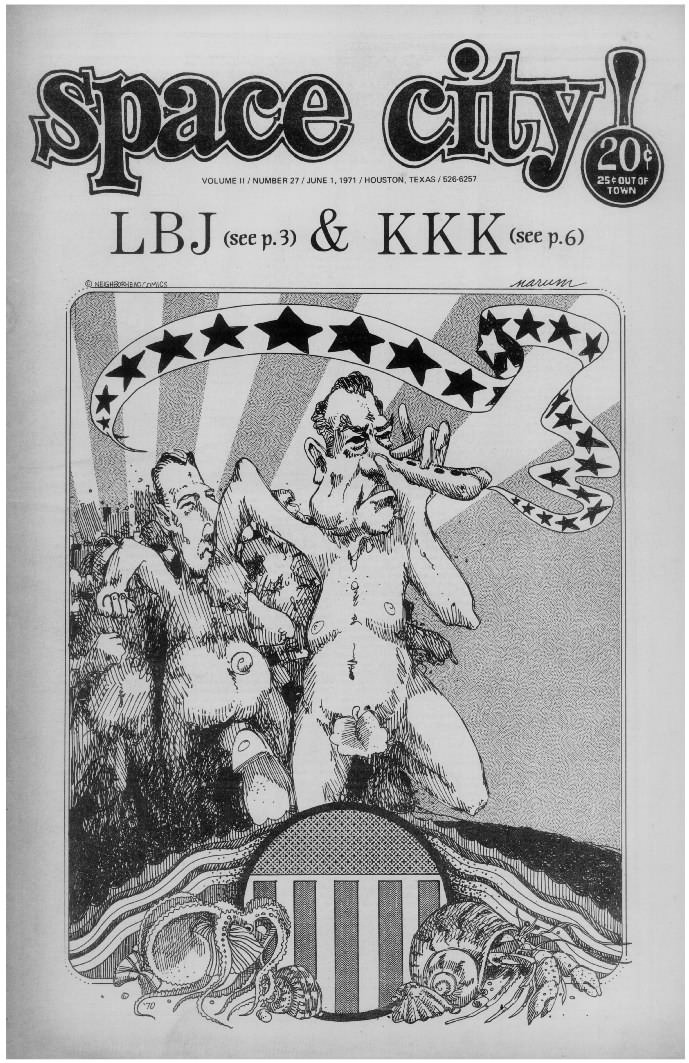

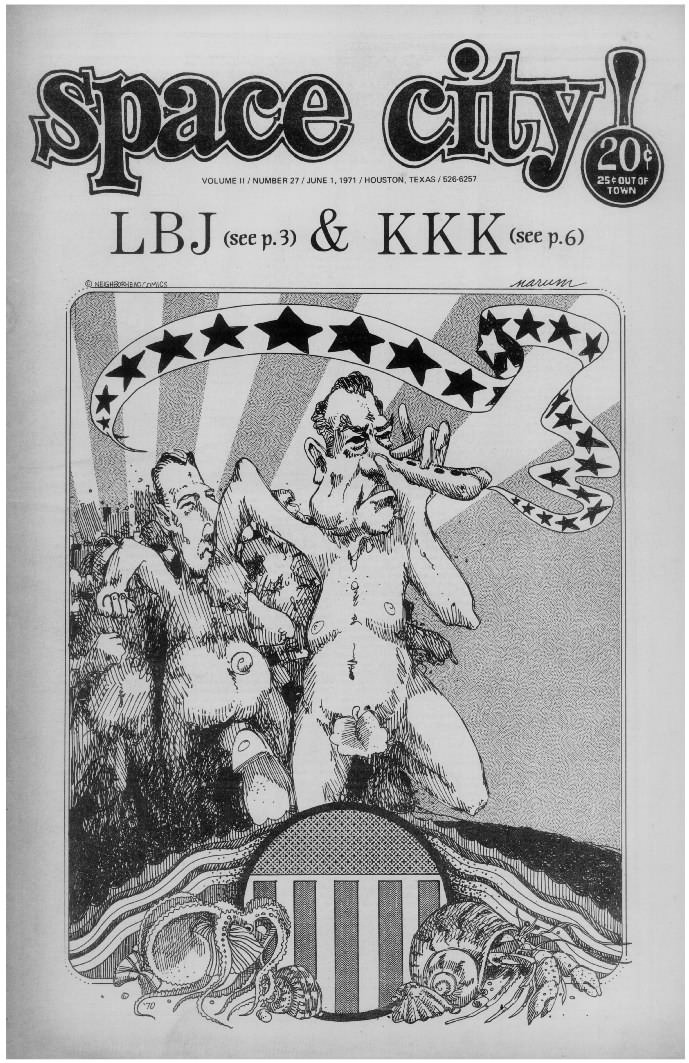

Drive-by shootings, firebombings, break-ins, and trashings were carried out on the offices of many underground papers around the country, fortunately without causing any fatalities. The offices of Houston's '' Space City!'' were bombed and its windows repeatedly shot out. In Houston, as in many other cities, the attackers, never identified, were suspected of being off-duty military or police personnel, or members of the

Drive-by shootings, firebombings, break-ins, and trashings were carried out on the offices of many underground papers around the country, fortunately without causing any fatalities. The offices of Houston's '' Space City!'' were bombed and its windows repeatedly shot out. In Houston, as in many other cities, the attackers, never identified, were suspected of being off-duty military or police personnel, or members of the

See Table: GI Underground Press During the Vietnam War (U.S. Military)

See Table: GI Underground Press During the Vietnam War (U.S. Military)

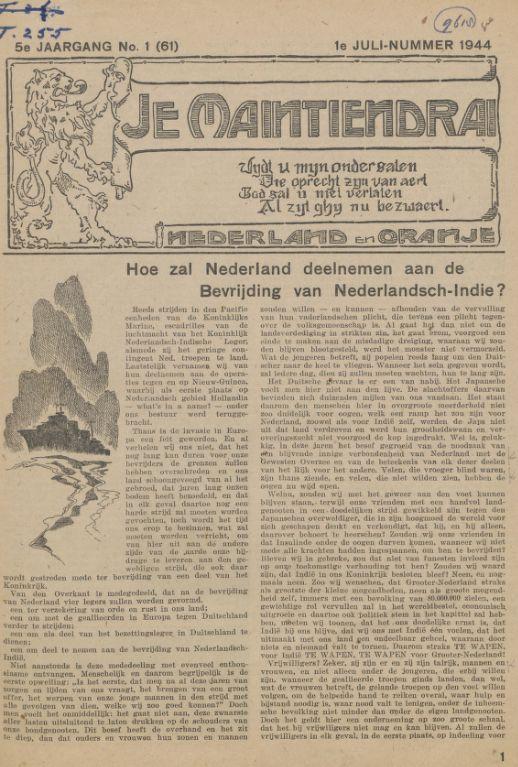

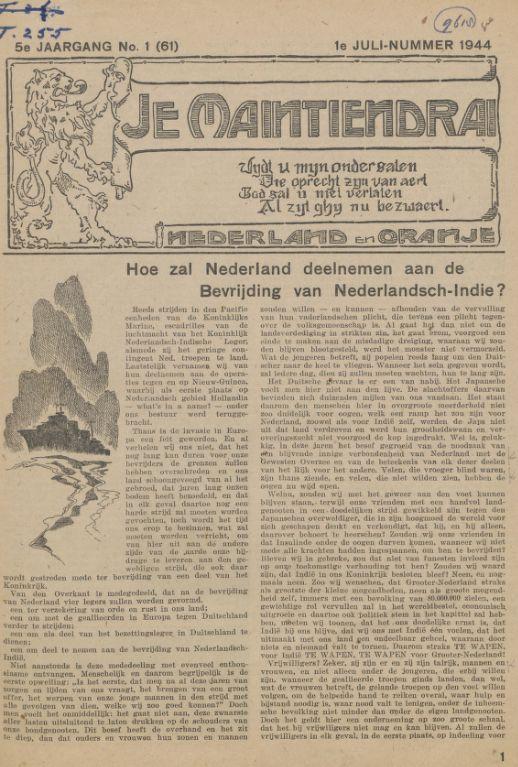

Clandestine press in the Netherlands is related to the second World War, which ran from 10 May 1940 until 5 May 1945 in the Netherlands.

* See the :w:nl:Lijst van verzetsbladen uit de Tweede Wereldoorlog, list of 1300 Dutch illegal WW2 newspapers on Dutch Wikipedia

* See also on Dutch Wikipedia

:* :w:nl:Lijst van uitgaveplaatsen van verzetsbladen tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog, List of places of publication of Dutch illegal WW2 newspapers

:* :w:nl:Lijst van drukkerijen en uitgeverijen van verzetsbladen gedurende de Tweede Wereldoorlog, List of printers and publishers of Dutch illegal WW2 newspapers

:* :w:nl:Lijst van legaal voortgezette verzetsbladen na de Tweede Wereldoorlog, List of legally continued Dutch WW2 newspapers

Clandestine press in the Netherlands is related to the second World War, which ran from 10 May 1940 until 5 May 1945 in the Netherlands.

* See the :w:nl:Lijst van verzetsbladen uit de Tweede Wereldoorlog, list of 1300 Dutch illegal WW2 newspapers on Dutch Wikipedia

* See also on Dutch Wikipedia

:* :w:nl:Lijst van uitgaveplaatsen van verzetsbladen tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog, List of places of publication of Dutch illegal WW2 newspapers

:* :w:nl:Lijst van drukkerijen en uitgeverijen van verzetsbladen gedurende de Tweede Wereldoorlog, List of printers and publishers of Dutch illegal WW2 newspapers

:* :w:nl:Lijst van legaal voortgezette verzetsbladen na de Tweede Wereldoorlog, List of legally continued Dutch WW2 newspapers

"The Underground GI Press: Pens Against the Pentagon"

''Commonweal''. Reprinted in ''Duck Power'' vol. 1, no. 4.

''Voices from the Underground (Vol. 1): Insider Histories of the Vietnam Era Underground Press''

* Holhut, Randolph T. [http://www.brasscheck.com/seldes/history.html "A Brief History of American Alternative Journalism in the Twentieth Century"], BrassCheck.com. Retrieved Dec. 15, 2022. * Thorne Webb Dreyer, Dreyer, Thorne and Victoria Smith

"The Movement and the New Media"

Liberation News Service (1969).

Underground/Alternative Newspapers History and Geography

::Maps and databases of over 2,000 underground/alternative newspapers between 1965 and 1975 in the U.S. ::From the Mapping American Social Movements project at the University of Washington. * A number of libraries have extensive microfilm collections of underground newspapers. For example, th

University of Oregon

library has a collection that consists of mostly, but not exclusively North American underground papers.

Chicano Newspapers and Periodicals 1966-1979

Maps and charts of over 300 Chicano newspapers from the 1960s and 70s

"Voices from the Underground"

::an exhibition of the North American underground press of the 1960s; ::includes a gallery of color images

''Rags''

a counterculture fashion magazine, from June 1970 through June 1971, from

''The Rag''

A digitally scanned archive of the first twelve issues (1966-67), from

Articles about the underground press

at ''The Rag Blog''

::(While ''The Avatar'' shared its design approach and many social concerns with other underground papers of the time, in one important respect it was completely atypical: it served as a platform for self-proclaimed "world saviour" Mel Lyman, leader of the Fort Hill Community.)

A collection of ''Space City News'' covers

by underground artist Bill Narum

The website for the film ''Sir! No Sir!''

has an extensive collection of primary source materials from the GI underground press

''The Truth'' Issue 3, December 1969

!-- -->, a Jordan High School (Long Beach, California) underground paper ; U.K. underground press

"Counter Cultures: Cultural Politics and the Underground Press"

by Gerry Carlin and Mark Jones

''International Times'' archive

''OZ magazine'', London, 1967-1973

, online at the University of Wollongong Library ; Australian underground press

''The Digger'', 1972-1975

online at the University of Wollongong Library

''Nexus'' magazine (Australia)

''OZ magazine'', Sydney, 1963-1969

, online at the University of Wollongong Library

Ozit.org

— history of ''OZ Magazine'' (archived site) ; European underground press

at stampamusicale.altervista.org

Interview of Underground press historian Sean Stewart

on Rag Radio, by

Historian John McMillian, author of ''Smoking Typewriters: The Sixties Underground Press and the Rise of Alternative Media in America''

on Rag Radio, Interviewed by

24 hour-long interviews with veterans of the Sixties underground press

on Rag Radio, by

The terms underground press or clandestine press refer to periodicals and publications that are produced without official approval, illegally or against the wishes of a dominant (governmental, religious, or institutional) group.

In specific recent (post-World War II) Asian, American and Western European context, the term "underground press" has most frequently been employed to refer to the independently published and distributed underground papers associated with the

The terms underground press or clandestine press refer to periodicals and publications that are produced without official approval, illegally or against the wishes of a dominant (governmental, religious, or institutional) group.

In specific recent (post-World War II) Asian, American and Western European context, the term "underground press" has most frequently been employed to refer to the independently published and distributed underground papers associated with the counterculture

A counterculture is a culture whose values and norms of behavior differ substantially from those of mainstream society, sometimes diametrically opposed to mainstream cultural mores.Eric Donald Hirsch. ''The Dictionary of Cultural Literacy''. Ho ...

of the late 1960s and early 1970s in India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

and Bangladesh

Bangladesh, officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, eighth-most populous country in the world and among the List of countries and dependencies by ...

in Asia, in the United States and Canada in North America, and the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

and other western nations. It can also refer to the newspapers produced independently in repressive regimes. In German occupied Europe

German-occupied Europe, or Nazi-occupied Europe, refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly militarily occupied and civil-occupied, including puppet states, by the (armed forces) and the government of Nazi Germany at ...

, for example, a thriving underground press operated, usually in association with the Resistance. Other notable examples include the ''samizdat

Samizdat (, , ) was a form of dissident activity across the Eastern Bloc in which individuals reproduced censored and underground makeshift publications, often by hand, and passed the documents from reader to reader. The practice of manual rep ...

'' and ''bibuła

The Polish underground press, devoted to prohibited materials ( sl. , lit. semitransparent blotting paper or, alternatively, , lit. second circulation), has a long history of combatting censorship of oppressive regimes in Poland. It existed th ...

'', which operated in the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

and Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

respectively, during the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

.

Origins

In Western Europe, a century after the invention of the printing press, a widespread underground press emerged in the mid-16th century with the clandestine circulation of

In Western Europe, a century after the invention of the printing press, a widespread underground press emerged in the mid-16th century with the clandestine circulation of Calvinist

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Protestantism, Continenta ...

books and broadsides, many of them printed in Geneva, which were secretly smuggled into other nations where the carriers who distributed such literature might face imprisonment, torture or death. Both Protestant and Catholic nations fought the introduction of Calvinism, which with its emphasis on intractable evil made its appeal to alienated, outsider subcultures willing to violently rebel against both church and state. In 18th century France, a large illegal underground press of the Enlightenment emerged, circulating anti-Royalist, anti-clerical and pornographic works in a context where all published works were officially required to be licensed. Starting in the mid-19th century an underground press sprang up in many countries around the world for the purpose of circulating the publications of banned Marxist political parties; during the German Nazi occupation of Europe, clandestine presses sponsored and subsidized by the Allies were set up in many of the occupied nations, although it proved nearly impossible to build any sort of effective underground press movement within Germany itself.

The French resistance

The French Resistance ( ) was a collection of groups that fought the German military administration in occupied France during World War II, Nazi occupation and the Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy#France, collaborationist Vic ...

published a large and active underground press that printed over 2 million newspapers a month; the leading titles were ''Combat

Combat (French language, French for ''fight'') is a purposeful violent Conflict (process), conflict between multiple combatants with the intent to harm the opposition. Combat may be armed (using weapons) or unarmed (Hand-to-hand combat, not usin ...

'', ''Libération

(), popularly known as ''Libé'' (), is a daily newspaper in France, founded in Paris by Jean-Paul Sartre and Serge July in 1973 in the wake of the protest movements of May 1968 in France, May 1968. Initially positioned on the far left of Fr ...

'', '' Défense de la France'', and '' Le Franc-Tireur''. Each paper was the organ of a separate resistance network, and funds were provided from Allied headquarters in London and distributed to the different papers by resistance leader Jean Moulin

Jean Pierre Moulin (; 20 June 1899 – 8 July 1943) was a French civil servant and hero of the French Resistance who succeeded in unifying the main networks of the Resistance in World War II, a unique act in Europe. He served as the first Presid ...

. Allied prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war for a ...

(POWs) published an underground newspaper called POW WOW

A powwow (also pow wow or pow-wow) is a gathering with dances held by many Native American and First Nations communities. Inaugurated in 1923, powwows today are an opportunity for Indigenous people to socialize, dance, sing, and honor their ...

. In Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural and socio-economic connotations. Its eastern boundary is marked by the Ural Mountain ...

, also since approximately 1940, underground publications were known by the name ''samizdat

Samizdat (, , ) was a form of dissident activity across the Eastern Bloc in which individuals reproduced censored and underground makeshift publications, often by hand, and passed the documents from reader to reader. The practice of manual rep ...

''.

The countercultural underground press movement of the 1960s borrowed the name from previous "underground presses" such as the Dutch underground press

The Dutch underground press was part of the resistance to the German occupation of the Netherlands during World War II, paralleling the emergence of underground media across German-occupied Europe.

After the occupation of the Netherlands in May ...

during the Nazi

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

occupations of the 1940s. Those predecessors were truly "underground", meaning they were illegal, thus published and distributed covertly. While the countercultural "underground" papers frequently battled with governmental authorities, for the most part they were distributed openly through a network of street vendors, newsstands and head shop

A head shop is a retail outlet specializing in Drug paraphernalia, paraphernalia used for consumption of cannabis and tobacco and items related to cannabis culture and related countercultures. They emerged from the hippie counterculture in ...

s, and thus reached a wide audience.

The underground press in the 1960s and 1970s existed in most countries with high GDP per capita and freedom of the press

Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the fundamental principle that communication and expression through various media, including printed and electronic Media (communication), media, especially publication, published materials, shoul ...

; similar publications existed in some developing countries and as part of the ''samizdat'' movement in the communist state

A communist state, also known as a Marxist–Leninist state, is a one-party state in which the totality of the power belongs to a party adhering to some form of Marxism–Leninism, a branch of the communist ideology. Marxism–Leninism was ...

s, notably Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

. Published as weeklies, monthlies, or "occasionals", and usually associated with left-wing politics

Left-wing politics describes the range of Ideology#Political ideologies, political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy either as a whole or of certain social ...

, they evolved on the one hand into today's alternative weeklies and on the other into zine

A zine ( ; short for ''magazine'' or ''fanzine'') is, as noted on Merriam-Webster’s official website, a magazine that is a “noncommercial often homemade or online publication usually devoted to specialized and often unconventional subject ...

s.

In Australia

The most prominent underground publication in Australia was a satirical magazine called '' OZ'' (1963 to 1969), which initially owed a debt to local university student newspapers such asHoni Soit

''Honi Soit'' is the student newspaper of the University of Sydney. First published in 1929, the newspaper is produced by an elected editorial team and a select group of reporters sourced from the university's populace. Its name is an abbrev ...

(University of Sydney) and Tharunka

''Gamamari'' is a student magazine published at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia. Established in 1953 as ''Tharunka'' at the then New South Wales University of Technology, the publication has been published in a variety of ...

(University of New South Wales), along with the UK magazine ''Private Eye

''Private Eye'' is a British fortnightly satirical and current affairs (news format), current affairs news magazine, founded in 1961. It is published in London and has been edited by Ian Hislop since 1986. The publication is widely recognised ...

''. The original edition appeared in Sydney on April Fools' Day, 1963 and continued sporadically until 1969. Editions published after February 1966 were edited by Richard Walsh, following the departure for the UK of his original co-editors Richard Neville and Martin Sharp

Martin Ritchie Sharp (21 January 1942 – 1 December 2013) was an Australian artist, cartoonist, songwriter and film-maker.

Career

Sharp was born in Bellevue Hill, New South Wales in 1942, and educated at Cranbrook private school, where one ...

, who went on to found a British edition (''London Oz'') in January 1967. In Melbourne Phillip Frazer, founder and editor of pop music magazine ''Go-Set

''Go-Set'' was the first Australian pop music newspaper, published weekly from 2 February 1966 to 24 August 1974, and was founded in Melbourne by Phillip Frazer, Peter Raphael and Tony Schauble. NOTE: This PDF is 282 pages. Widely described as ...

'' since January 1966, branched out into alternate, underground publications with ''Revolution

In political science, a revolution (, 'a turn around') is a rapid, fundamental transformation of a society's class, state, ethnic or religious structures. According to sociologist Jack Goldstone, all revolutions contain "a common set of elements ...

'' in 1970, followed by ''High Times

''High Times'' was an American monthly magazine (and cannabis brand) that advocates the legalization of cannabis as well as other counterculture ideas. The magazine was founded in 1974 by Tom Forcade. The magazine had its own book publishing d ...

'' (1971 to 1972) and '' The Digger'' (1972 to 1975).

List of Australian underground papers

* '' The Digger'' (1972–1975) * '' The Living Daylights'' (1973–1974) * ''High Times

''High Times'' was an American monthly magazine (and cannabis brand) that advocates the legalization of cannabis as well as other counterculture ideas. The magazine was founded in 1974 by Tom Forcade. The magazine had its own book publishing d ...

'' (1971–1972)

* '' OZ Sydney'' (1963–1969)

* ''New Dawn'' magazine

* ''Nexus'' magazine

* ''Revolution

In political science, a revolution (, 'a turn around') is a rapid, fundamental transformation of a society's class, state, ethnic or religious structures. According to sociologist Jack Goldstone, all revolutions contain "a common set of elements ...

'' (1970–1971)

In the United Kingdom

The underground press offered a platform to the socially impotent and mirrored the changing way of life in theUK underground

The British counter-culture or underground scene developed during the mid-1960s, and was linked to the hippie subculture of the United States. Its primary focus was around Ladbroke Grove and Notting Hill in London. It generated its own magazin ...

.

In London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, Barry Miles

Barry Miles (born 21 February 1943) is an English author known for his participation in and writing on the subjects of the 1960s London underground and counterculture. He is the author of numerous books and his work has also regularly appeare ...

, John Hopkins, and others produced ''International Times

''International Times'' (''it'' or ''IT'') is the name of various Underground press, underground newspapers, with the original title founded in London in 1966 and running until October 1973. Editors included John Hopkins (p ...

'' from October 1966 which, following legal threats from ''The Times'' newspaper was renamed ''IT''.

Richard Neville arrived in London from Australia, where he had edited '' Oz'' (1963 to 1969). He launched a British version (1967 to 1973), which was A4 (as opposed to ''IT''Martin Sharp

Martin Ritchie Sharp (21 January 1942 – 1 December 2013) was an Australian artist, cartoonist, songwriter and film-maker.

Career

Sharp was born in Bellevue Hill, New South Wales in 1942, and educated at Cranbrook private school, where one ...

.

Other publications followed, such as ''Friends

''Friends'' is an American television sitcom created by David Crane (producer), David Crane and Marta Kauffman, which aired on NBC from September 22, 1994, to May 6, 2004, lasting List of Friends episodes, ten seasons. With an ensemble cast ...

'' (later ''Frendz''), based in the Ladbroke Grove

Ladbroke Grove ( ) is a road in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, London, England, which passes through Kensal Green and Notting Hill, running north–south between Harrow Road and Holland Park Avenue.

It is also the name of the sur ...

area of London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

; ''Ink

Ink is a gel, sol, or solution that contains at least one colorant, such as a dye or pigment, and is used to color a surface to produce an image, text, or design. Ink is used for drawing or writing with a pen, brush, reed pen, or quill. ...

'', which was more overtly political; and ''Gandalf's Garden

Gandalf's Garden was a mystical community which flourished at the end of the 1960s as part of the London hippie-underground movement, and ran a shop as well as a magazine of the same name. It emphasised the mystical interests of the period and adv ...

'' which espoused the mystic path.

Legal challenges

The flaunting of sexuality within the underground press provoked prosecution. ''IT'' was taken to court for publishing small ads forhomosexuals

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between people of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" exc ...

; despite the 1967 legalisation

Legalization is the process of removing a legal prohibition against something which is currently not legal.

Legalization is a process often applied to what are regarded, by those working towards legalization, as victimless crimes, of which one ...

of homosexuality between consenting adults in private, importuning remained subject to prosecution. Publication of the ''Oz'' "School Kids" issue brought charges against the three ''Oz'' editors, who were convicted and given jail sentences. This was the first time the Obscene Publications Act 1959

The Obscene Publications Act 1959 ( 7 & 8 Eliz. 2. c. 66) is an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom Parliament, which significantly reformed the law related to obscenity in England and Wales. Before the passage of the Act, the law on publis ...

was combined with a moral conspiracy charge. The convictions were, however, overturned on appeal.

Harassment and intimidation

Police harassment of the British underground, in general, became commonplace, to the point that in 1967 the police seemed to focus in particular on the apparent source of agitation: the underground press. The police campaign may have had an effect contrary to that which was presumably intended. If anything, according to one or two who were there at the time, it actually made the underground press stronger. "It focused attention, stiffened resolve, and tended to confirm that what we were doing was considered dangerous to the establishment", rememberedMick Farren

Michael Anthony Farren (3 September 1943 – 27 July 2013) was an English rock musician, singer, journalist, and author associated with counterculture and the UK underground, who had a significant influence on the development of British proto ...

. From April 1967, and for some while later, the police raided the offices of ''International Times'' to try, it was alleged, to force the paper out of business. In order to raise money for ''IT'' a benefit event was put together, "The 14 Hour Technicolor Dream" Alexandra Palace

Alexandra Palace is an entertainment and sports venue in North London, situated between Wood Green and Muswell Hill in the London Borough of Haringey. A listed building, Grade II listed building, it is built on the site of Tottenham Wood and th ...

on 29 April 1967.

On one occasion – in the wake of yet another raid on ''IT'' – London's alternative press succeeded in pulling off what was billed as a 'reprisal attack' on the police. The paper ''Black Dwarf'' published a detailed floor-by-floor 'Guide to Scotland Yard

Scotland Yard (officially New Scotland Yard) is the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police, the territorial police force responsible for policing Greater London's London boroughs, 32 boroughs. Its name derives from the location of the original ...

', complete with diagrams, descriptions of locks on particular doors, and snippets of overheard conversation. The anonymous author, or 'blue dwarf', as he styled himself, claimed to have perused archive files, and even to have sampled one or two brands of scotch in the Commissioner's office. The London ''Evening Standard

The ''London Standard'', formerly the ''Evening Standard'' (1904–2024) and originally ''The Standard'' (1827–1904), is a long-established regional newspaper published weekly and distributed free newspaper, free of charge in London, Engl ...

'' headlined the incident as "Raid on the Yard". A day or two later ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a British daily broadsheet conservative newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed in the United Kingdom and internationally. It was found ...

'' announced that the prank had resulted in all security passes to the police headquarters having to be withdrawn and then re-issued.

Support from British pop culture

By the end of the decade, community artists and bands such asPink Floyd

Pink Floyd are an English Rock music, rock band formed in London in 1965. Gaining an early following as one of the first British psychedelic music, psychedelic groups, they were distinguished by their extended compositions, sonic experiments ...

(before they "went commercial"), The Deviants, Pink Fairies

Pink Fairies are an English proto-punk rock band initially active in the London (Ladbroke Grove) underground and psychedelic scene of the early 1970s. They promoted free music, drug use, and anarchy, and often performed impromptu gigs and ot ...

, Hawkwind

Hawkwind are an English rock band known as one of the earliest space rock groups. Since their formation in November 1969, Hawkwind have gone through many incarnations and have incorporated many different styles into their music, including hard ...

, Michael Moorcock

Michael John Moorcock (born 18 December 1939) is an English writer, particularly of science fiction and fantasy, who has published a number of well-received literary novels as well as comic thrillers, graphic novels and non-fiction. He has wo ...

and Steve Peregrin Took

Steve Peregrin Took (born Stephen Ross Porter; 28 July 1949 – 27 October 1980) was an English musician and songwriter, best known for his membership of the duo Tyrannosaurus Rex with Marc Bolan. After breaking with Bolan, he concentrated on h ...

would arise in a symbiotic co-operation with the underground press. The underground press publicised these bands and this made it possible for them to tour and get record deals. The band members travelled around spreading the ethos and the demand for underground newspapers and magazines grew and flourished for a while.

Neville published an account of the counterculture

A counterculture is a culture whose values and norms of behavior differ substantially from those of mainstream society, sometimes diametrically opposed to mainstream cultural mores.Eric Donald Hirsch. ''The Dictionary of Cultural Literacy''. Ho ...

called ''Play Power'', in which he described most of the world's underground publications. He also listed many of the regular key topics from those publications, including the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

, Black Power

Black power is a list of political slogans, political slogan and a name which is given to various associated ideologies which aim to achieve self-determination for black people. It is primarily, but not exclusively, used in the United States b ...

, politics, police brutality

Police brutality is the excessive and unwarranted use of force by law enforcement against an individual or Public order policing, a group. It is an extreme form of police misconduct and is a civil rights violation. Police brutality includes, b ...

, hippies

A hippie, also spelled hippy, especially in British English, is someone associated with the counterculture of the 1960s, counterculture of the mid-1960s to early 1970s, originally a youth movement that began in the United States and spread to dif ...

and the lifestyle revolution, drugs, popular music, new society, cinema, theatre, graphics, cartoons, etc.

Local papers

Apart from publications such as ''IT'' and ''Oz'', both of which had a national circulation, the 1960s and 1970s saw the emergence of a whole range of local alternative newspapers, which were usually published monthly. These were largely made possible by the introduction in the 1950s of offset litho printing, which was much cheaper than traditional typesetting and use of the rotary letterpress. Such local papers included: * ''Aberdeen Peoples Press'' * ''Alarm'' (Swansea) * '' Andersonstown News'' (Belfast) * ''Brighton Voice

''Brighton Voice'' was an alternative or underground newspaper published in Brighton, England in the 1970s and 1980s.

History

''Brighton Voice'' was one of the many alternative local newspapers that sprung up in the United Kingdom in the 196 ...

''

* ''Bristol Voice''

* ''Feedback'' (Norwich)

* ''Hackney People's Press''

* ''Islington Gutter Press''

* ''Leeds Other Paper''

* ''Response'' (Earl's Court, London)

* ''Sheffield Free Press''

* '' West Highland Free Press''

A 1980 review identified some 70 such publications around the United Kingdom but estimated that the true number could well have run into hundreds. Such papers were usually published anonymously, for fear of the UK's draconian libel laws. They followed a broad anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hierarchy, hierarchy, primarily targeting the state (polity), state and capitalism. A ...

, libertarian

Libertarianism (from ; or from ) is a political philosophy that holds freedom, personal sovereignty, and liberty as primary values. Many libertarians believe that the concept of freedom is in accord with the Non-Aggression Principle, according ...

, left-wing of the Labour Party, socialist approach but the philosophy of a paper was usually flexible as those responsible for its production came and went. Most papers were run on collective

A collective is a group of entities that share or are motivated by at least one common issue or interest or work together to achieve a common objective. Collectives can differ from cooperatives in that they are not necessarily focused upon an e ...

principles.

List of UK underground papers

North America

Legal definition of "underground"

In the United States, the term ''underground'' did not mean ''illegal'' as it did in many other countries. TheFirst Amendment

First most commonly refers to:

* First, the ordinal form of the number 1

First or 1st may also refer to:

Acronyms

* Faint Images of the Radio Sky at Twenty-Centimeters, an astronomical survey carried out by the Very Large Array

* Far Infrared a ...

and various court decisions (e.g. ''Near v. Minnesota

''Near v. Minnesota'', 283 U.S. 697 (1931), was a landmark decision of the US Supreme Court under which prior restraint on publication was found to violate freedom of the press as protected under the First Amendment. This principle was applied to ...

'') give very broad rights to anyone to publish a newspaper or other publication, and severely restrict government efforts to close down or censor a private publication. In fact, when censorship attempts are made by government agencies, they are either done in clandestine fashion (to keep it from being known the action is being taken by a government agency) or are usually ordered stopped by the courts when judicial action is taken in response to them.

A publication must, in general, be committing a crime (for example, reporters burglarizing someone's office to obtain information about a news item); violating the law in publishing a particular article or issue (printing obscene material, copyright infringement

Copyright infringement (at times referred to as piracy) is the use of Copyright#Scope, works protected by copyright without permission for a usage where such permission is required, thereby infringing certain exclusive rights granted to the c ...

, libel

Defamation is a communication that injures a third party's reputation and causes a legally redressable injury. The precise legal definition of defamation varies from country to country. It is not necessarily restricted to making assertions ...

, breaking a non-disclosure agreement

A non-disclosure agreement (NDA), also known as a confidentiality agreement (CA), confidential disclosure agreement (CDA), proprietary information agreement (PIA), or secrecy agreement (SA), is a legal contract or part of a contract between at le ...

); directly threatening national security; or causing or potentially causing an imminent emergency

An emergency is an urgent, unexpected, and usually dangerous situation that poses an immediate risk to health, life, property, or environment and requires immediate action. Most emergencies require urgent intervention to prevent a worsening ...

(the "clear and present danger

''Clear and Present Danger'' is a political thriller novel, written by Tom Clancy and published on August 17, 1989. A sequel to '' The Cardinal of the Kremlin'' (1988), main character Jack Ryan becomes acting Deputy Director of Intelligence i ...

" standard) to be ordered stopped or otherwise suppressed, and then usually only the particular offending article or articles in question will be banned, while the newspaper itself is allowed to continue operating and can continue publishing other articles.

In the U.S. the term "underground newspaper" generally refers to an independent (and typically smaller) newspaper focusing on unpopular themes or counterculture issues. Typically, these tend to be politically to the left or far left. More narrowly, in the U.S. the term "underground newspaper" most often refers to publications of the period 1965–1973, when a sort of boom or craze for local tabloid underground newspapers swept the country in the wake of court decisions making prosecution for obscenity far more difficult. These publications became the voice of the rising New Left

The New Left was a broad political movement that emerged from the counterculture of the 1960s and continued through the 1970s. It consisted of activists in the Western world who, in reaction to the era's liberal establishment, campaigned for freer ...

and the hippie

A hippie, also spelled hippy, especially in British English, is someone associated with the counterculture of the 1960s, counterculture of the mid-1960s to early 1970s, originally a youth movement that began in the United States and spread to dif ...

/psychedelic/rock and roll

Rock and roll (often written as rock & roll, rock-n-roll, and rock 'n' roll) is a Genre (music), genre of popular music that evolved in the United States during the late 1940s and early 1950s. It Origins of rock and roll, originated from African ...

counterculture

A counterculture is a culture whose values and norms of behavior differ substantially from those of mainstream society, sometimes diametrically opposed to mainstream cultural mores.Eric Donald Hirsch. ''The Dictionary of Cultural Literacy''. Ho ...

of the 1960s in America, and a focal point of opposition to the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

and the draft

Conscription, also known as the draft in the United States and Israel, is the practice in which the compulsory enlistment in a national service, mainly a military service, is enforced by law. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it contin ...

.

Origins

The North American countercultural press of the 1960s drew inspiration from predecessors that had begun in the 1950s, such as the ''Village Voice

''The Village Voice'' is an American news and culture publication based in Greenwich Village, New York City, known for being the country's first alternative newsweekly. Founded in 1955 by Dan Wolf, Ed Fancher, John Wilcock, and Norman Ma ...

'' and Paul Krassner

Paul Krassner (April 9, 1932 – July 21, 2019) was an American writer and satirist. He was the founder, editor, and a frequent contributor to the freethought magazine ''The Realist'', first published in 1958. Krassner became a key figure in t ...

's satirical paper ''The Realist

''The Realist'' was a magazine of "social-political-religious criticism and satire", intended as a hybrid of a grown-ups version of ''Mad'' and Lyle Stuart's anti-censorship monthly ''The Independent.'' Edited and published by Paul Krassner, ...

.'' Arguably, the first underground newspaper of the 1960s was the ''Los Angeles Free Press

The ''Los Angeles Free Press'', also called the "''Freep''", is often cited as the first, and certainly was the largest, of the underground newspapers of the 1960s. The ''Freep'' was founded in 1964 by Art Kunkin, who served as its publisher un ...

'', founded in 1964 and first published under that name in 1965.

1965–1973 boom period

'' The East Village Other'' was "formed as a stock company, with Walter Bowart, Allen Katzman and Dan Rattiner each owning three shares", co-founded in October 1965 byWalter Bowart

Walter Howard Bowart (May 14, 1939 – December 18, 2007)Fox, Marglit (Jan. 14, 2008)(obituary). ''New York Times''. was an American leader in the counterculture of the 1960s, counterculture movement of the 1960s, founder and editor of the first ...

, Ishmael Reed

Ishmael Scott Reed (born February 22, 1938) is an American poet, novelist, essayist, songwriter, composer, playwright, editor and publisher known for his Satire, satirical works challenging American political culture. Perhaps his best-known wor ...

, Allen Katzman, Dan Rattiner, Sherry Needham, and John Wilcock

John Wilcock (4 August 1927 – 13 September 2018) was a British journalist known for his work in the underground press, as well as his travel guide books.

The first news editor of the New York ''Village Voice'', Wilcock shook up staid publish ...

. It began as a monthly and then went biweekly.

According to Louis Menand

Louis Menand (; born January 21, 1952) is an American critic, essayist, and professor who wrote the Pulitzer-winning book '' The Metaphysical Club'' (2001), an intellectual and cultural history of late 19th- and early 20th-century America.

Life ...

, writing in ''The New Yorker

''The New Yorker'' is an American magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. It was founded on February 21, 1925, by Harold Ross and his wife Jane Grant, a reporter for ''The New York T ...

'', the underground press movement in the United States was "one of the most spontaneous and aggressive growths in publishing history." During the peak years of the phenomenon, there were generally about 100 papers currently publishing at any given time. But the underground press phenomenon proved short-lived.

An Underground Press Syndicate

The Underground Press Syndicate (UPS), later known as the Alternative Press Syndicate (APS), was a network of countercultural newspapers and magazines that operated from 1966 into the late 1970s. As it evolved, the Underground Press Syndicate crea ...

(UPS) roster published in November 1966 listed 14 underground papers, 11 of them in the United States, two in England, and one in Canada. Within a few years the number had mushroomed. A 1971 roster, published in Abbie Hoffman

Abbot Howard Hoffman (November 30, 1936 – April 12, 1989) was an American political and social activist who co-founded the Youth International Party ("Yippies") and was a member of the Chicago Seven. He was also a leading proponent of the ...

's ''Steal This Book

''Steal This Book'' is a book written by Abbie Hoffman. Written in 1970 and published the following year, it exemplifies the counterculture of the 1960s. The book sold more than a quarter of a million copies between April and November 1971. The n ...

'', listed 271 UPS-affiliated papers; 11 were in Canada, 23 in Europe, and the remainder in the United States. The underground press' combined readership eventually reached into the millions.

The early papers varied greatly in visual style, content, and even in basic concept — and emerged from very different kinds of communities.Reed, John"The Underground Press and Its Extraordinary Moment in US History,"

''

Hyperallergic

''Hyperallergic'' is an online arts magazine, based in Brooklyn, New York. Founded by the art critic Hrag Vartanian and his husband Veken Gueyikian in October 2009, the site describes itself as a "forum for serious, playful, and radical thinki ...

'' (July 26, 2016). Many were decidedly rough-hewn, learning journalistic and production skills on the run. Some were militantly political while others featured highly spiritual content and were graphically sophisticated and adventuresome.

By 1969, virtually every sizable city or college town in North America boasted at least one underground newspaper. Among the most prominent of the underground papers were the '' San Francisco Oracle,'' '' San Francisco Express Times'', ''Rags'' (San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

); the ''Berkeley Barb

The ''Berkeley Barb'' was a weekly underground newspaper published in Berkeley, California, during the years 1965 to 1980. It was one of the first and most influential of the counterculture newspapers, covering such subjects as the anti-war mov ...

'' and '' Berkeley Tribe''; ''The Image'', ''Open City

In war, an open city is a settlement which has announced it has abandoned all defensive efforts, generally in the event of the imminent capture of the city to avoid destruction. Once a city has declared itself open, the opposing military will ...

'' (Los Angeles

Los Angeles, often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, most populous city in the U.S. state of California, and the commercial, Financial District, Los Angeles, financial, and Culture of Los Angeles, ...

), ''Fifth Estate

The Fifth Estate is a socio-cultural reference to groupings of outlier viewpoints in contemporary society, and is most associated with bloggers, journalists publishing in non-mainstream media outlets, and online social networks. The "Fifth" Esta ...

'' (Detroit

Detroit ( , ) is the List of municipalities in Michigan, most populous city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is situated on the bank of the Detroit River across from Windsor, Ontario. It had a population of 639,111 at the 2020 United State ...

), '' Other Scenes'' (dispatched from various locations around the world by John Wilcock

John Wilcock (4 August 1927 – 13 September 2018) was a British journalist known for his work in the underground press, as well as his travel guide books.

The first news editor of the New York ''Village Voice'', Wilcock shook up staid publish ...

); '' The Helix'' (Seattle

Seattle ( ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Washington and in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. With a population of 780,995 in 2024, it is the 18th-most populous city in the United States. The city is the cou ...

); ''Avatar

Avatar (, ; ) is a concept within Hinduism that in Sanskrit literally means . It signifies the material appearance or incarnation of a powerful deity, or spirit on Earth. The relative verb to "alight, to make one's appearance" is sometimes u ...

'' (Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

); ''The Broadside'' (Cambridge, Massachusetts ); ''The Chicago Seed''; '' The Great Speckled Bird'' (Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Georgia (U.S. state), most populous city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. It is the county seat, seat of Fulton County, Georg ...

); ''The Rag

''The Rag'' was an underground press, underground newspaper published in Austin, Texas from 1966–1977. The weekly paper covered political and cultural topics that the conventional press ignored, such as the growing antiwar movement, the sexu ...

'' (Austin, Texas

Austin ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of Texas. It is the county seat and most populous city of Travis County, Texas, Travis County, with portions extending into Hays County, Texas, Hays and W ...

); ''Rat

Rats are various medium-sized, long-tailed rodents. Species of rats are found throughout the order Rodentia, but stereotypical rats are found in the genus ''Rattus''. Other rat genera include '' Neotoma'' (pack rats), '' Bandicota'' (bandicoo ...

'' (New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

); '' Space City!'' (Houston

Houston ( ) is the List of cities in Texas by population, most populous city in the U.S. state of Texas and in the Southern United States. Located in Southeast Texas near Galveston Bay and the Gulf of Mexico, it is the county seat, seat of ...

) and in Canada, ''The Georgia Straight

''The Georgia Straight'' is a free Canadian weekly news and entertainment newspaper published in Vancouver, British Columbia, by Overstory Media Group. Often known simply as ''The Straight'', it is delivered to newsboxes, post-secondary schools ...

'' (Vancouver

Vancouver is a major city in Western Canada, located in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia. As the List of cities in British Columbia, most populous city in the province, the 2021 Canadian census recorded 662,248 people in the cit ...

, BC).

''The Rag

''The Rag'' was an underground press, underground newspaper published in Austin, Texas from 1966–1977. The weekly paper covered political and cultural topics that the conventional press ignored, such as the growing antiwar movement, the sexu ...

'', founded in Austin, Texas

Austin ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of Texas. It is the county seat and most populous city of Travis County, Texas, Travis County, with portions extending into Hays County, Texas, Hays and W ...

, in 1966 by Thorne Dreyer

Thorne Webb Dreyer (born August 1, 1945) is an American writer, editor, publisher, and political activist who played a major role in the 1960s-1970s Counterculture of the 1960s, counterculture, New Left, and underground press movements. Dreyer no ...

and Carol Neiman, was especially influential. Historian Laurence Leamer called it "one of the few legendary undergrounds,"Leamer, Laurence, ''The Paper Revolutionaries: The Rise of the Underground Press'' (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1972) and, according to John McMillian, it served as a model for many papers that followed. ''The Rag'' was the sixth member of UPS and the first underground paper in the South and, according to historian Abe Peck, it was the "first undergrounder to represent the participatory democracy, community organizing and synthesis of politics and culture that the New Left of the mid-sixties was trying to develop." Leamer, in his 1972 book ''The Paper Revolutionaries'', called ''The Rag'' "one of the few legendary undergrounds". Gilbert Shelton

Gilbert Shelton (born May 31, 1940) is an American cartoonist and a key member of the underground comix movement. He is the creator of the iconic underground characters '' The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers'', '' Fat Freddy's Cat'', and '' Wonder ...

's legendary '' Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers'' comic strip began in ''The Rag'', and thanks in part to UPS, was republished all over the world.

Probably the most graphically innovative of the underground papers was the '' San Francisco Oracle''. John Wilcock

John Wilcock (4 August 1927 – 13 September 2018) was a British journalist known for his work in the underground press, as well as his travel guide books.

The first news editor of the New York ''Village Voice'', Wilcock shook up staid publish ...

, a founder of the Underground Press Syndicate, wrote about the ''Oracle'': "Its creators are using color the way Lautrec must once have experimented with lithography – testing the resources of the medium to the utmost and producing what almost any experienced newspaperman would tell you was impossible... it is a creative dynamo whose influence will undoubtedly change the look of American publishing."

In the period 1969–1970, a number of underground papers grew more militant

The English word ''militant'' is both an adjective and a noun, and it is generally used to mean vigorously active, combative and/or aggressive, especially in support of a cause, as in "militant reformers". It comes from the 15th century Lat ...

and began to openly discuss armed revolution against the state, some going so far as to print manuals for bombing and urging their readers to arm themselves; this trend, however, soon fell silent after the rise and fall of the Weather Underground

The Weather Underground was a far-left Marxist militant organization first active in 1969, founded on the Ann Arbor campus of the University of Michigan. Originally known as the Weathermen, or simply Weatherman, the group was organized as a f ...

and the tragic shootings at Kent State.

High school underground press

During this period there was also a widespread underground press movement circulating unauthorized student-published tabloids andmimeographed

A mimeograph machine (often abbreviated to mimeo, sometimes called a stencil duplicator or stencil machine) is a low-cost duplicating machines, duplicating machine that works by forcing ink through a stencil onto paper. The process is called ...

sheets at hundreds of high schools around the U.S. (In 1968, a survey of 400 high schools in Southern California

Southern California (commonly shortened to SoCal) is a geographic and Cultural area, cultural List of regions of California, region that generally comprises the southern portion of the U.S. state of California. Its densely populated coastal reg ...

found that 52% reported student underground press activity in their school.) Most of these papers put out only a few issues, running off a few hundred copies of each and circulating them only at one local school, although there was one system-wide antiwar high school underground paper produced in New York in 1969 with a 10,000-copy press run. Houston's ''Little Red Schoolhouse,'' a citywide underground paper published by high school students, was founded in 1970.

For a time in 1968–1969, the high school underground press had its own press services: FRED (run by C. Clark Kissinger of Students for a Democratic Society

Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) was a national student activist organization in the United States during the 1960s and was one of the principal representations of the New Left. Disdaining permanent leaders, hierarchical relationships a ...

, with its base in Chicago schools) and HIPS (High School Independent Press Service, produced by students working out of Liberation News Service

Liberation News Service (LNS) was a New Left, anti-war underground press news agency that distributed news bulletins and photographs to hundreds of subscribing underground, alternative and radical newspapers from 1967 to 1981. Considered the "Asso ...

headquarters and aimed primarily but not exclusively at New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

schools). These services typically produced a weekly packet of articles and features mailed to subscribing papers around the country; HIPS reported 60 subscribing papers.

G.I. underground press

The GI underground press within the U.S. military produced over four hundred titles during the Vietnam War, some produced by antiwar

The GI underground press within the U.S. military produced over four hundred titles during the Vietnam War, some produced by antiwar GI Coffeehouses

GI coffeehouses were coffeehouses set up as part of the anti-war movement during the Vietnam War era as a method of fostering antiwar and anti-military sentiment within the U.S. military. They were mainly organized by civilian antiwar activists, ...

, and many of them small, crudely produced, low-circulation mimeographed "zines" written by GIs or recently discharged veterans opposed to the war and circulated locally on and off-base. Several GI underground papers had large-scale, national distribution of tens of thousands of copies, including thousands of copies mailed to GI's overseas. These papers were produced with the support of civilian anti-war activists, and had to be disguised to be sent through the mail into Vietnam, where soldiers distributing or even possessing them might be subject to harassment, disciplinary action, or arrest. There were at least two of these papers produced in the combat zone in Vietnam itself, '' The Boomerang Barb'' and '' GI Says''.

Technological and financial realities

The boom in the underground press was made practical by the availability of cheapoffset printing

Offset printing is a common printing technique in which the inked image is transferred (or "offset") from a plate to a rubber blanket and then to the printing surface. When used in combination with the lithography, lithographic process, which ...

, which made it possible to print a few thousand copies of a small tabloid paper for a couple of hundred dollars, which a sympathetic printer might extend on credit. Paper was cheap, and many printing firms around the country had over-expanded during the 1950s and had excess capacity on their offset web presses, which could be negotiated for at bargain rates.

Most papers operated on a shoestring budget, pasting up camera-ready copy on layout sheets on the editor's kitchen table, with labor performed by unpaid, non-union volunteers. Typesetting costs, which at the time were wiping out many established big city papers, were avoided by typing up copy on a rented or borrowed IBM Selectric typewriter

The IBM Selectric (a portmanteau of "selective" and "electric") was a highly successful line of electric typewriters introduced by IBM on 31 July 1961.

Instead of the "basket" of individual typebars that swung up to strike the ribbon and page ...

to be pasted-up by hand. As one observer commented with only slight hyperbole, students were financing the publication of these papers out of their lunch money.

Syndicates and news services

In mid-1966, the cooperativeUnderground Press Syndicate

The Underground Press Syndicate (UPS), later known as the Alternative Press Syndicate (APS), was a network of countercultural newspapers and magazines that operated from 1966 into the late 1970s. As it evolved, the Underground Press Syndicate crea ...

(UPS) was formed at the instigation of Walter Bowart

Walter Howard Bowart (May 14, 1939 – December 18, 2007)Fox, Marglit (Jan. 14, 2008)(obituary). ''New York Times''. was an American leader in the counterculture of the 1960s, counterculture movement of the 1960s, founder and editor of the first ...

, the publisher of another early paper, the ''East Village Other

''The East Village Other'' (often abbreviated as ''EVO'') was an American underground press, underground newspaper in New York City, issued biweekly during the 1960s. It was described by ''The New York Times'' as "a New York newspaper so counterc ...

''. The UPS allowed member papers to freely reprint content from any of the other member papers.

During this period, there were also a number of left-wing political periodicals with concerns similar to those of the underground press. Some of these periodicals joined the Underground Press Syndicate to gain services such as microfilming

A microform is a scaled-down reproduction of a document, typically either photographic film or paper, made for the purposes of transmission, storage, reading, and printing. Microform images are commonly reduced to about 4% or of the original d ...

, advertising, and the free exchange of articles and newspapers. Examples include '' The Black Panther'' (the paper of the Black Panther Party

The Black Panther Party (originally the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense) was a Marxism–Leninism, Marxist–Leninist and Black Power movement, black power political organization founded by college students Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newto ...

, Oakland, California

Oakland is a city in the East Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area in the U.S. state of California. It is the county seat and most populous city in Alameda County, California, Alameda County, with a population of 440,646 in 2020. A major We ...

), and ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

'' (New York City), both of which had national distribution.

Almost from the outset, UPS supported and distributed underground comix

Underground comix are small press or self-published comic books that are often socially relevant or satirical in nature. They differ from mainstream comics in depicting content forbidden to mainstream publications by the Comics Code Authority, ...

strips to its member papers. Some of the cartoonists syndicated by UPS included Robert Crumb

Robert Dennis Crumb (; born August 30, 1943) is an American artist who often signs his work R. Crumb. His work displays a nostalgia for American folk culture of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and satire of contemporary American c ...

, Jay Lynch

Jay Patrick Lynch (January 7, 1945 – March 5, 2017) was an American cartoonist who played a key role in the underground comix movement with his '' Bijou Funnies'' and other titles. He is best known for his comic strip ''Nard n' Pat'' and the r ...

, The Mad Peck

John Frederick Peck (November 16, 1942 – March 15, 2025), known as The Mad Peck, was an American underground cartoonist, rock poster artist and disc jockey. His most famous poster is a 1978 comic book-style poster that starts with the line, ...

's ''Burn of the Week'', Ron Cobb

Ronald Ray Cobb (September 21, 1937 – September 21, 2020) was an American–Australian artist. In addition to his work as an editorial cartoonist, he contributed concept art to major films including '' Dark Star'' (1974), ''Star Wars'' (1977), ...

, and Frank Stack

Frank Huntington Stack (born October 31, 1937, in Houston, Texas) is an American underground comix, underground cartoonist and fine artist. Working under the name Foolbert Sturgeon to avoid persecution for his work while living in the Bible Belt ...

."Special Collections and Rare Books: Frank Stack Collection,"University of Missouri Libraries. Accessed Dec. 29, 2016. The Rip Off Press Syndicate was launched 1973 to compete in selling underground comix content to the underground press and

student publication

A student publication is a media outlet such as a newspaper, magazine, television show, or radio station Graduate student journal, produced by students at an educational institution. These publications typically cover local and school-related new ...

s.Fox, M. Steven"Rip Off Comix — 1977-1991 / Rip Off Press,"

Comixjoint. Retrieved Dec. 5, 2022. Each Friday, the company sent out a distribution sheet with the strips it was selling, by such cartoonists as

Gilbert Shelton

Gilbert Shelton (born May 31, 1940) is an American cartoonist and a key member of the underground comix movement. He is the creator of the iconic underground characters '' The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers'', '' Fat Freddy's Cat'', and '' Wonder ...

, Bill Griffith

William Henry Jackson Griffith (born January 20, 1944) is an American cartoonist who signs his work Bill Griffith and Griffy. He is best known for his surreal daily comic strip '' Zippy''. The catchphrase "Are we having fun yet?" is credited t ...

, Joel Beck, Dave Sheridan, Ted Richards, and Harry Driggs.

The Liberation News Service

Liberation News Service (LNS) was a New Left, anti-war underground press news agency that distributed news bulletins and photographs to hundreds of subscribing underground, alternative and radical newspapers from 1967 to 1981. Considered the "Asso ...

(LNS), co-founded in the summer of 1967 by Ray Mungo

Raymond A. Mungo (born 1946) is an American author, co-author, or editor of more than a dozen books. He writes about business, economics, and financial matters as well as cultural issues.

In the 1960s, he attended Boston University, where he ser ...

and Marshall Bloom

Marshall Irving Bloom (July 16, 1944 – November 1, 1969) was an American journalist and activist, best known as co-founder in 1967 of the Liberation News Service, the "Associated Press" of the underground press.

Early life and education

Marsh ...

, "provided coverage of events to which most papers would have otherwise had no access." In a similar vein, John Berger

John Peter Berger ( ; 5 November 1926 – 2 January 2017) was an English art critic, novelist, painter and poet. His novel '' G.'' won the 1972 Booker Prize, and his essay on art criticism '' Ways of Seeing'', written as an accompaniment to t ...

, Lee Marrs

Lee Marrs (born September 5, 1945) is an American cartoonist and animator, and one of the first female underground comix creators. She is best known for her comic book series ''The Further Fattening Adventures of Pudge, Girl Blimp'', which lasted ...

, and others co-founded Alternative Features Service, Inc. in 1970 to supply the underground and college press, as well as independent radio

Independent radio indicates a radio station that are run in a manner,different from usual from the countries it broadcasts in.

Conversely, in places such as the United States, where commercial broadcasters are the norm, independent radio is some ...

stations, with syndicated press materials that especially highlighted the creation of alternative institutions, such as free clinics, people's banks, free universities, and alternative housing

Alternative housing is a category of domicile structures that are built or designed outside of the mainstream norm e.g., town homes, single family homes and apartment complexes. In modern days, alternative housing commonly takes the form of tin ...

.

By 1973, many underground papers had folded, at which point the Underground Press Syndicate acknowledged the passing of the undergrounds and renamed itself the Alternative Press Syndicate

The Underground Press Syndicate (UPS), later known as the Alternative Press Syndicate (APS), was a network of counterculture of the 1960s, countercultural newspapers and magazines that operated from 1966 into the late 1970s. As it evolved, the Und ...

(APS). After a few years, APS also foundered, to be supplanted in 1978 by the Association of Alternative Newsweeklies

The Association of Alternative Newsmedia (AAN) is a trade association of alternative weekly newspapers in North America. It provides services to many generally liberal or progressive weekly newspapers across the United States and in Canada. A ...

.

Controversies

One of the most notorious underground newspapers to join UPS and rally activists, poets, and artists by giving them an uncensored voice, was the '' NOLA Express'' in New Orleans. Started by Robert Head and Darlene Fife as part of political protests and extending the "mimeo revolution" by protest and freedom-of-speech poets during the 1960s, ''NOLA Express'' was also a member of the Committee of Small Magazine Editors and Publishers (COSMEP). These two affiliations with organizations that were often at cross-purposes made ''NOLA Express'' one of the most radical and controversial publications of the counterculture movement. Part of the controversy about ''NOLA Express'' included graphic photographs and illustrations of which many even in today's society would be banned as pornographic.Charles Bukowski

Henry Charles Bukowski ( ; born Heinrich Karl Bukowski, ; August 16, 1920 – March 9, 1994) was a German Americans, German-American poet, novelist, and short story writer. His writing was influenced by the social, cultural, and economic ambien ...

's syndicated column, ''Notes of a Dirty Old Man,'' ran in ''NOLA Express'', and Francisco McBride's illustration for the story "The Fuck Machine" was considered sexist, pornographic, and created an uproar. All of this controversy helped to increase the readership and bring attention to the political causes that editors Fife and Head supported.

Harassment and intimidation

Many of the papers faced official harassment on a regular basis; local police repeatedly raided and busted up the offices of ''Dallas Notes

''Dallas Notes'' was a biweekly underground newspaper published in Dallas, Texas from 1967 to 1970, and edited by Stoney Burns (penname of Brent Lasalle Stein; 1942–2011), whose father owned a printing company in Dallas. Initially founded by D ...

'' and jailed editor Stoney Burns on drug charges; charged Atlanta's '' Great Speckled Bird'' and others with obscenity; arrested street vendors; and pressured local printers not to print underground papers.

In Austin, the regents at the University of Texas sued ''The Rag'' to prevent circulation on campus but the American Civil Liberties Union

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is an American nonprofit civil rights organization founded in 1920. ACLU affiliates are active in all 50 states, Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico. The budget of the ACLU in 2024 was $383 million.

T ...

successfully defended the paper's First Amendment rights before the U.S. Supreme Court. In an apparent attempt to shut down ''The Spectator'' in Bloomington, Indiana, editor James Retherford was briefly imprisoned for alleged violations of the Selective Service laws; his conviction was overturned and the prosecutors were rebuked by a federal judge.

Drive-by shootings, firebombings, break-ins, and trashings were carried out on the offices of many underground papers around the country, fortunately without causing any fatalities. The offices of Houston's '' Space City!'' were bombed and its windows repeatedly shot out. In Houston, as in many other cities, the attackers, never identified, were suspected of being off-duty military or police personnel, or members of the

Drive-by shootings, firebombings, break-ins, and trashings were carried out on the offices of many underground papers around the country, fortunately without causing any fatalities. The offices of Houston's '' Space City!'' were bombed and its windows repeatedly shot out. In Houston, as in many other cities, the attackers, never identified, were suspected of being off-duty military or police personnel, or members of the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to KKK or Klan, is an American Protestant-led Christian terrorism, Christian extremist, white supremacist, Right-wing terrorism, far-right hate group. It was founded in 1865 during Reconstruction era, ...

or Minuteman organizations.

Some of the most violent attacks were carried out against the underground press in San Diego. In 1976 the ''San Diego Union

''The San Diego Union-Tribune'' is a metropolitan daily newspaper published in San Diego, California, that has run since 1868. Its name derives from a 1992 merger between the two major daily newspapers at the time, ''The San Diego Union'' and ...

'' reported that the attacks in 1971 and 1972 had been carried out by a right-wing paramilitary

A paramilitary is a military that is not a part of a country's official or legitimate armed forces. The Oxford English Dictionary traces the use of the term "paramilitary" as far back as 1934.

Overview

Though a paramilitary is, by definiti ...

group calling itself the Secret Army Organization, which had ties to the local office of the FBI.

The U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and Federal law enforcement in the United States, its principal federal law enforcement ag ...

(FBI) conducted surveillance and disruption activities on the underground press in the United States, including a campaign to destroy the alternative agency Liberation News Service

Liberation News Service (LNS) was a New Left, anti-war underground press news agency that distributed news bulletins and photographs to hundreds of subscribing underground, alternative and radical newspapers from 1967 to 1981. Considered the "Asso ...

. As part of its COINTELPRO

COINTELPRO (a syllabic abbreviation derived from Counter Intelligence Program) was a series of covert and illegal projects conducted between 1956 and 1971 by the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) aimed at surveilling, infiltr ...

designed to discredit and infiltrate radical New Left groups, the FBI also launched phony underground newspapers such as the ''Armageddon News'' at Indiana University Bloomington

Indiana University Bloomington (IU Bloomington, Indiana University, IU, IUB, or Indiana) is a public university, public research university in Bloomington, Indiana, United States. It is the flagship university, flagship campus of Indiana Univer ...

, ''The Longhorn Tale'' at the University of Texas at Austin

The University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin, UT, or Texas) is a public university, public research university in Austin, Texas, United States. Founded in 1883, it is the flagship institution of the University of Texas System. With 53,082 stud ...

, and the ''Rational Observer'' at American University

The American University (AU or American) is a Private university, private University charter#Federal, federally chartered research university in Washington, D.C., United States. Its main campus spans 90-acres (36 ha) on Ward Circle, in the Spri ...

in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

The FBI also ran the Pacific International News Service in San Francisco, the Chicago Midwest News, and the New York Press Service. Many of these organizations consisted of little more than a post office box and a letterhead, designed to enable the FBI to receive exchange copies of underground press publications and send undercover observers to underground press gatherings.

Decline of the underground press

By the end of 1972, with the end of the draft and the winding down of the Vietnam War, there was increasingly little reason for the underground press to exist. A number of papers passed out of existence during this time; among the survivors a newer and less polemical view toward middle-class values and working within the system emerged. The underground press began to evolve into the socially conscious, lifestyle-orientedalternative media