Un Nuevo Modo De Amar on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The United Nations (UN) is an

The first specific step towards the establishment of the United Nations was the Inter-Allied conference that led to the Declaration of St James's Palace on 12 June 1941. By August 1941, American president

The first specific step towards the establishment of the United Nations was the Inter-Allied conference that led to the Declaration of St James's Palace on 12 June 1941. By August 1941, American president

By 1 March 1945, 21 additional states had signed the Declaration by United Nations. After months of planning, the UN Conference on International Organization opened in

By 1 March 1945, 21 additional states had signed the Declaration by United Nations. After months of planning, the UN Conference on International Organization opened in

Though the UN's primary mandate was

Though the UN's primary mandate was

After the Cold War, the UN saw a radical expansion in its peacekeeping duties, taking on more missions in five years than it had in the previous four decades. Between 1988 and 2000, the number of adopted Security Council resolutions more than doubled, and the peacekeeping budget increased more than tenfold. The UN negotiated an end to the

After the Cold War, the UN saw a radical expansion in its peacekeeping duties, taking on more missions in five years than it had in the previous four decades. Between 1988 and 2000, the number of adopted Security Council resolutions more than doubled, and the peacekeeping budget increased more than tenfold. The UN negotiated an end to the

, United Nations website In practice, the International Civil Service Commission, which governs the conditions of UN personnel, takes reference to the highest-paying national civil service. Staff salaries are subject to an internal tax that is administered by the UN organizations.

The General Assembly is the main

The General Assembly is the main

The Security Council is charged with maintaining peace and security among countries. While other organs of the UN can only make "recommendations" to member states, the Security Council has the power to make binding decisions that member states have agreed to carry out, under the terms of Charter Article 25. The decisions of the council are known as

The Security Council is charged with maintaining peace and security among countries. While other organs of the UN can only make "recommendations" to member states, the Security Council has the power to make binding decisions that member states have agreed to carry out, under the terms of Charter Article 25. The decisions of the council are known as

intergovernmental organization

Globalization is social change associated with increased connectivity among societies and their elements and the explosive evolution of transportation and telecommunication

Telecommunication is the transmission of information by various typ ...

whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace

World peace, or peace on Earth, is the concept of an ideal state of peace within and among all people and nations on Planet Earth. Different cultures, religions, philosophies, and organizations have varying concepts on how such a state would ...

and security

Security is protection from, or resilience against, potential harm (or other unwanted coercive change) caused by others, by restraining the freedom of others to act. Beneficiaries (technically referents) of security may be of persons and social ...

, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmonizing the actions of nations. It is the world's largest and most familiar international organization. The UN is headquartered on international territory in New York City, and has other main offices in Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaki ...

, Nairobi

Nairobi ( ) is the capital and largest city of Kenya. The name is derived from the Maasai phrase ''Enkare Nairobi'', which translates to "place of cool waters", a reference to the Nairobi River which flows through the city. The city proper ha ...

, Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, and The Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a city and municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's administrative centre and its seat of government, and while the official capital of ...

(home to the International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; french: Cour internationale de justice, links=no; ), sometimes known as the World Court, is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN). It settles disputes between states in accordanc ...

).

The UN was established after World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

with the aim of preventing future world wars, succeeding the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

, which was characterized as ineffective. On 25 April 1945, 50 governments met in San Francisco for a conference and started drafting the UN Charter, which was adopted on 25 June 1945 and took effect on 24 October 1945, when the UN began operations. Pursuant to the Charter, the organization's objectives include maintaining international peace and security, protecting human rights

Human rights are Morality, moral principles or Social norm, normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for ce ...

, delivering humanitarian aid

Humanitarian aid is material and logistic assistance to people who need help. It is usually short-term help until the long-term help by the government and other institutions replaces it. Among the people in need are the homeless, refugees, and ...

, promoting sustainable development

Sustainable development is an organizing principle for meeting human development goals while also sustaining the ability of natural systems to provide the natural resources and ecosystem services on which the economy and society depend. The des ...

, and upholding international law

International law (also known as public international law and the law of nations) is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognized as binding between states. It establishes normative guidelines and a common conceptual framework for ...

. At its founding, the UN had 51 member states

A member state is a state that is a member of an international organization or of a federation or confederation.

Since the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) include some members that are not sovereign states ...

; with the addition of South Sudan

South Sudan (; din, Paguot Thudän), officially the Republic of South Sudan ( din, Paankɔc Cuëny Thudän), is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is bordered by Ethiopia, Sudan, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of the C ...

in 2011, membership is now 193, representing almost all of the world's sovereign state

A sovereign state or sovereign country, is a polity, political entity represented by one central government that has supreme legitimate authority over territory. International law defines sovereign states as having a permanent population, defin ...

s.

The organization's mission to preserve world peace was complicated in its early decades by the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

between the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

and Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

and their respective allies. Its missions have consisted primarily of unarmed military observers and lightly armed troops with primarily monitoring, reporting and confidence-building roles. UN membership grew significantly following widespread decolonization beginning in the 1960s. Since then, 80 former colonies have gained independence, including 11 trust territories

United Nations trust territories were the successors of the remaining League of Nations mandates and came into being when the League of Nations ceased to exist in 1946. All of the trust territories were administered through the United Natio ...

that had been monitored by the Trusteeship Council

The United Nations Trusteeship Council (french: links=no, Conseil de tutelle des Nations unies) is one of the organs of the United Nations, six principal organs of the United Nations, established to help ensure that United Nations Trust Territor ...

. By the 1970s, the UN's budget for economic and social development programmes far outstripped its spending on peacekeeping

Peacekeeping comprises activities intended to create conditions that favour lasting peace. Research generally finds that peacekeeping reduces civilian and battlefield deaths, as well as reduces the risk of renewed warfare.

Within the United N ...

. After the end of the Cold War, the UN shifted and expanded its field operations, undertaking a wide variety of complex tasks.

The UN has six principal organs: the General Assembly

A general assembly or general meeting is a meeting of all the members of an organization or shareholders of a company.

Specific examples of general assembly include:

Churches

* General Assembly (presbyterian church), the highest court of presby ...

; the Security Council; the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC); the Trusteeship Council

The United Nations Trusteeship Council (french: links=no, Conseil de tutelle des Nations unies) is one of the organs of the United Nations, six principal organs of the United Nations, established to help ensure that United Nations Trust Territor ...

; the International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; french: Cour internationale de justice, links=no; ), sometimes known as the World Court, is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN). It settles disputes between states in accordanc ...

; and the UN Secretariat. The UN System

The United Nations System consists of the United Nations' six principal organs (the General Assembly, Security Council, Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), Trusteeship Council, International Court of Justice (ICJ), and the UN Secretariat), ...

includes a multitude of specialized agencies

United Nations Specialized Agencies are autonomous organizations working with the United Nations and each other through the co-ordinating machinery of the United Nations Economic and Social Council at the intergovernmental level, and through th ...

, funds and programmes such as the World Bank Group

The World Bank Group (WBG) is a family of five international organizations that make leveraged loans to developing countries. It is the largest and best-known development bank in the world and an observer at the United Nations Development Grou ...

, the World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for international public health. The WHO Constitution states its main objective as "the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level of h ...

, the World Food Programme, UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

, and UNICEF

UNICEF (), originally called the United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund in full, now officially United Nations Children's Fund, is an agency of the United Nations responsible for providing Humanitarianism, humanitarian and Devel ...

. Additionally, non-governmental organization

A non-governmental organization (NGO) or non-governmental organisation (see spelling differences) is an organization that generally is formed independent from government. They are typically nonprofit entities, and many of them are active in h ...

s may be granted consultative status with ECOSOC and other agencies to participate in the UN's work.

The UN's chief administrative officer is the secretary-general

Secretary is a title often used in organizations to indicate a person having a certain amount of authority, power, or importance in the organization. Secretaries announce important events and communicate to the organization. The term is derived ...

, currently Portuguese politician and diplomat António Guterres

António Manuel de Oliveira Guterres ( , ; born 30 April 1949) is a Portuguese politician and diplomat. Since 2017, he has served as secretary-general of the United Nations, the ninth person to hold this title. A member of the Portuguese Socia ...

, who began his first five year-term on 1 January 2017 and was re-elected on 8 June 2021. The organization is financed by assessed and voluntary contributions from its member states.

The UN, its officers, and its agencies have won many Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Nobel Prize in Chemistry, Chemi ...

s, though other evaluations of its effectiveness have been mixed. Some commentators believe the organization to be an important force for peace and human development, while others have called it ineffective, biased, or corrupt.

History

Background (pre-1941)

In the century prior to the UN's creation, several international organizations such as theInternational Committee of the Red Cross

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC; french: Comité international de la Croix-Rouge) is a humanitarian organization which is based in Geneva, Switzerland, and it is also a three-time Nobel Prize Laureate. State parties (signato ...

were formed to ensure protection and assistance for victims of armed conflict and strife.

During World War I, several major leaders, especially US President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

, advocated for a world body to guarantee peace. The winners of the war, the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

, met to hammer out formal peace terms at the Paris Peace Conference. The League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

was approved, and started operations, but the U.S. never joined. On 10 January 1920, the League of Nations formally came into being when the Covenant of the League of Nations, ratified by 42 nations in 1919, took effect. The League Council acted as a type of executive body directing the Assembly's business. It began with four permanent members— the United Kingdom, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

, and Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

.

After some limited successes and failures during the 1920s, the League proved ineffective in the 1930s. It failed to act against the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1933. Forty nations voted for Japan to withdraw from Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer Manc ...

but Japan voted against it and walked out of the League instead of withdrawing from Manchuria. It also failed against the Second Italo-Ethiopian War

The Second Italo-Ethiopian War, also referred to as the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, was a war of aggression which was fought between Italy and Ethiopia from October 1935 to February 1937. In Ethiopia it is often referred to simply as the Itali ...

when calls for economic sanctions against Italy failed. Italy and other nations left the league. All of them realized that it had failed and they began to re-arm as fast as possible.

When war broke out in 1939, the League closed down.

Declarations by the Allies of World War II (1941–1944)

The first specific step towards the establishment of the United Nations was the Inter-Allied conference that led to the Declaration of St James's Palace on 12 June 1941. By August 1941, American president

The first specific step towards the establishment of the United Nations was the Inter-Allied conference that led to the Declaration of St James's Palace on 12 June 1941. By August 1941, American president Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

and British prime minister Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

had drafted the Atlantic Charter

The Atlantic Charter was a statement issued on 14 August 1941 that set out American and British goals for the world after the end of World War II. The joint statement, later dubbed the Atlantic Charter, outlined the aims of the United States and ...

to define goals for the post-war world. At the subsequent meeting of the Inter-Allied Council in London on 24 September 1941, the eight governments in exile of countries under Axis occupation, together with the Soviet Union and representatives of the Free French Forces, unanimously adopted adherence to the common principles of policy set forth by Britain and United States.

President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill met at the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

in December 1941 for the Arcadia Conference. Roosevelt, considered a founder of the UN, coined the term ''United Nations'' to describe the Allied countries. Churchill accepted it, noting its use by Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824), known simply as Lord Byron, was an English romantic poet and Peerage of the United Kingdom, peer. He was one of the leading figures of the Romantic movement, and h ...

. The text of the Declaration by United Nations was drafted on 29 December 1941, by Roosevelt, Churchill, and Roosevelt aide Harry Hopkins

Harry Lloyd Hopkins (August 17, 1890 – January 29, 1946) was an American statesman, public administrator, and presidential advisor. A trusted deputy to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Hopkins directed New Deal relief programs before servi ...

. It incorporated Soviet suggestions but included no role for France. One major change from the Atlantic Charter was the addition of a provision for religious freedom, which Stalin approved after Roosevelt insisted.

Roosevelt's idea of the " Four Powers", referring to the four major Allied countries, the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

, Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

, and Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeast ...

, emerged in the Declaration by United Nations. On New Year's Day 1942, President Roosevelt, Prime Minister Churchill, Maxim Litvinov, of the USSR, and T. V. Soong, of China, signed the " Declaration by United Nations", and the next day the representatives of twenty-two other nations added their signatures. During the war, "the United Nations" became the official term for the Allies. To join, countries had to sign the Declaration and declare war on the Axis powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

.

The October 1943 Moscow Conference resulted in the Moscow Declarations

The Moscow Declarations were four declarations signed during the Moscow Conference (1943), Moscow Conference on October 30, 1943. The declarations are distinct from the Communique that was issued following the Moscow Conference (1945), Moscow Confe ...

, including the Four Power Declaration on General Security which aimed for the creation "at the earliest possible date of a general international organization". This was the first public announcement that a new international organization was being contemplated to replace the League of Nations. The Tehran Conference

The Tehran Conference (codenamed Eureka) was a strategy meeting of Joseph Stalin, Franklin Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill from 28 November to 1 December 1943, after the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran. It was held in the Soviet Union's embassy i ...

followed shortly afterwards at which Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin met and discussed the idea of a post-war international organization.

The new international organization was formulated and negotiated among the delegations from the Allied Big Four at the Dumbarton Oaks Conference

The Dumbarton Oaks Conference, or, more formally, the Washington Conversations on International Peace and Security Organization, was an international conference at which proposals for the establishment of a "general international organization", w ...

from 21 September to 7 October 1944. They agreed on proposals for the aims, structure and functioning of the new international organization. It took the conference at Yalta in February 1945, and further negotiations with Moscow, before all the issues were resolved.

Founding (1945)

By 1 March 1945, 21 additional states had signed the Declaration by United Nations. After months of planning, the UN Conference on International Organization opened in

By 1 March 1945, 21 additional states had signed the Declaration by United Nations. After months of planning, the UN Conference on International Organization opened in San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

, 25 April 1945, attended by 50 governments and a number of non-governmental organizations. The Big Four sponsoring countries invited other nations to take part and the heads of the delegations of the four chaired the plenary meetings. Winston Churchill urged Roosevelt to restore France to its status of a major Power after the liberation of Paris in August 1944. The drafting of the Charter of the United Nations

The Charter of the United Nations (UN) is the foundational treaty of the UN, an intergovernmental organization. It establishes the purposes, governing structure, and overall framework of the UN system, including its six principal organs: the ...

was completed over the following two months; it was signed on 26 June 1945 by the representatives of the 50 countries. Jan Smuts was a principal author of the draft. The UN officially came into existence on 24 October 1945, upon ratification of the Charter by the five permanent members of the Security Council—the US, the UK, France, the Soviet Union and the Republic of China—and by a majority of the other 46 signatories.

The first meetings of the General Assembly

A general assembly or general meeting is a meeting of all the members of an organization or shareholders of a company.

Specific examples of general assembly include:

Churches

* General Assembly (presbyterian church), the highest court of presby ...

, with 51 nations represented, and the Security Council took place in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

beginning in January 1946. Debates began at once, covering topical issues such as the presence of Russian troops in Iranian Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan or Azarbaijan ( fa, آذربایجان, ''Āzarbāijān'' ; az-Arab, آذربایجان, ''Āzerbāyjān'' ), also known as Iranian Azerbaijan, is a historical region in northwestern Iran that borders Iraq, Turkey, the Nakhchivan ...

, British forces in Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

and within days the first veto

A veto is a legal power to unilaterally stop an official action. In the most typical case, a president or monarch vetoes a bill to stop it from becoming law. In many countries, veto powers are established in the country's constitution. Veto ...

was cast. British diplomat Gladwyn Jebb

Hubert Miles Gladwyn Jebb, 1st Baron Gladwyn (25 April 1900 – 24 October 1996) was a prominent British civil servant, diplomat and politician who served as the acting secretary-general of the United Nations between 1945 and 1946.

Early ...

served as acting secretary-general.

The General Assembly selected New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

as the site for the headquarters of the UN, construction began on 14 September 1948 and the facility was completed on 9 October 1952. Its site—like UN headquarters buildings in Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaki ...

, Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, and Nairobi

Nairobi ( ) is the capital and largest city of Kenya. The name is derived from the Maasai phrase ''Enkare Nairobi'', which translates to "place of cool waters", a reference to the Nairobi River which flows through the city. The city proper ha ...

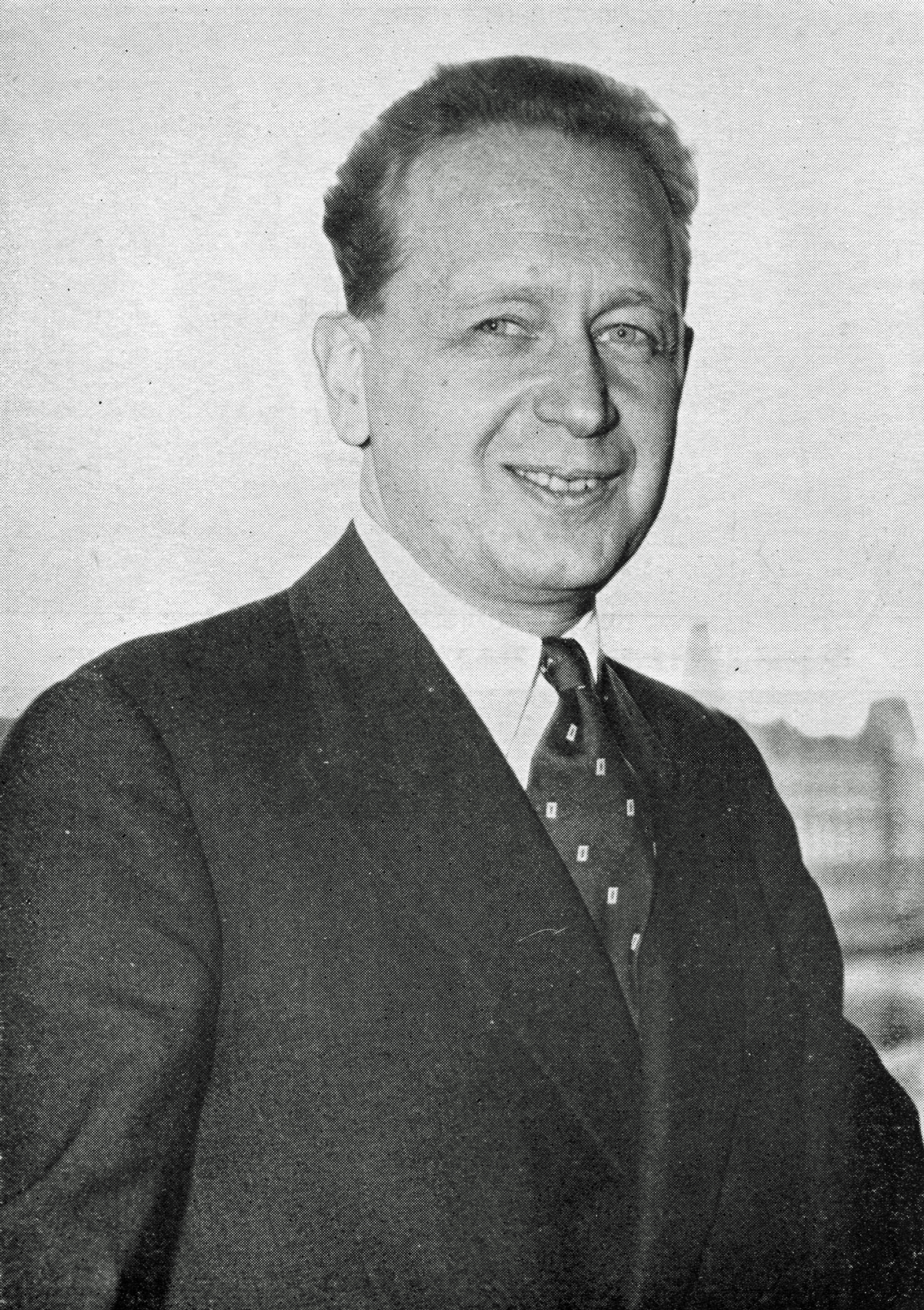

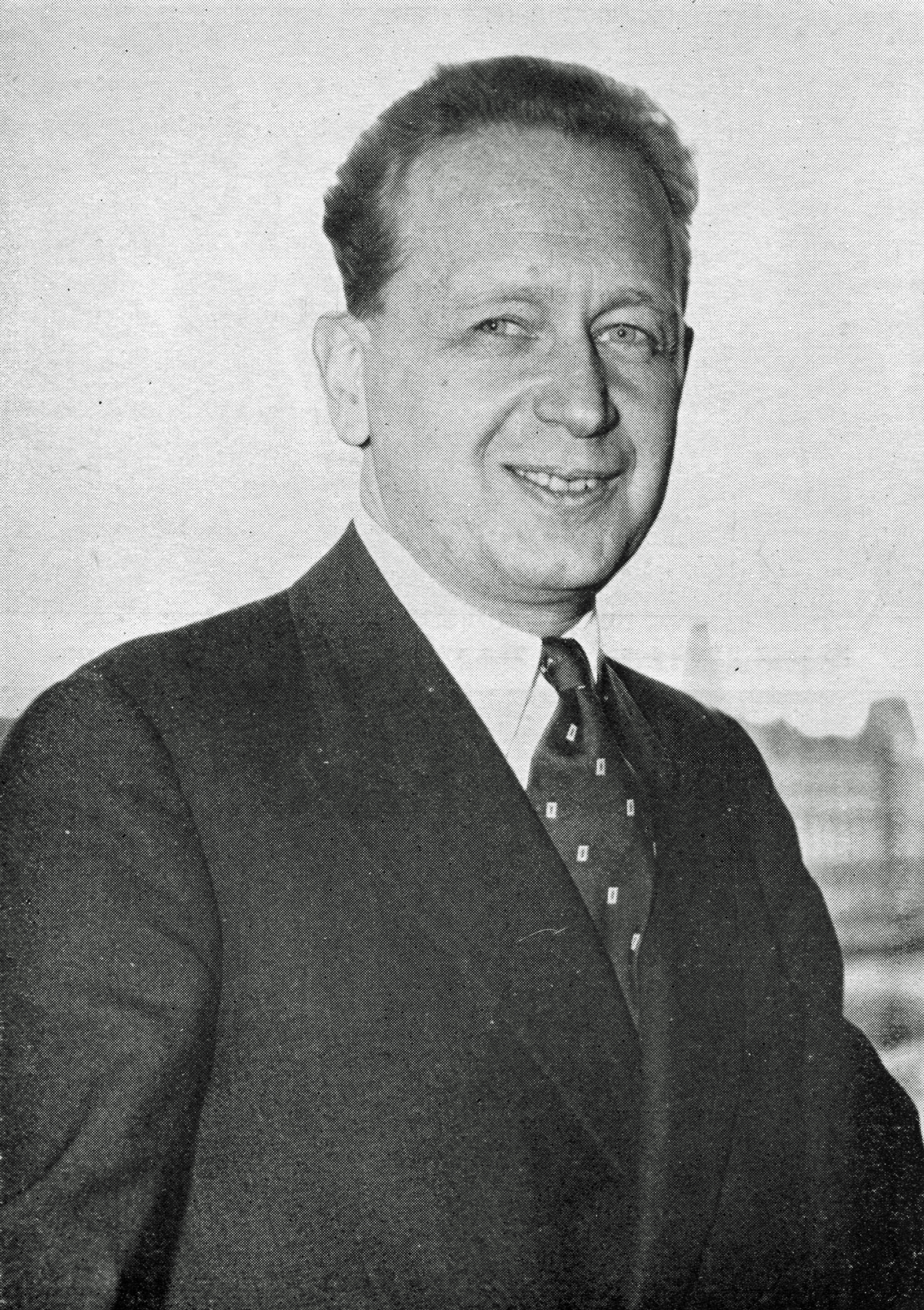

—is designated as international territory. The Norwegian foreign minister, Trygve Lie

Trygve Halvdan Lie ( , ; 16 July 1896 – 30 December 1968) was a Norwegians, Norwegian politician, labour leader, government official and author. He served as Norwegian foreign minister during the critical years of the Nygaardsvold's Cabinet, N ...

, was elected as the first UN secretary-general.

Cold War (1947–1991)

Though the UN's primary mandate was

Though the UN's primary mandate was peacekeeping

Peacekeeping comprises activities intended to create conditions that favour lasting peace. Research generally finds that peacekeeping reduces civilian and battlefield deaths, as well as reduces the risk of renewed warfare.

Within the United N ...

, the division between the US and USSR often paralysed the organization, generally allowing it to intervene only in conflicts distant from the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

. Two notable exceptions were a Security Council resolution on 7 July 1950 authorizing a US-led coalition to repel the North Korean invasion of South Korea, passed in the absence of the USSR, and the signing of the Korean Armistice Agreement

The Korean Armistice Agreement ( ko, 한국정전협정 / 조선정전협정; zh, t=韓國停戰協定 / 朝鮮停戰協定) is an armistice that brought about a complete cessation of hostilities of the Korean War. It was signed by United Sta ...

on 27 July 1953.

On 29 November 1947, the General Assembly approved a resolution to partition Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

, approving the creation of the state of Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

. Two years later, Ralph Bunche

Ralph Johnson Bunche (; August 7, 1904 – December 9, 1971) was an American political scientist, diplomat, and leading actor in the mid-20th-century decolonization process and US civil rights movement, who received the 1950 Nobel Peace Prize f ...

, a UN official, negotiated an armistice to the resulting conflict. On 7 November 1956, the first UN peacekeeping force was established to end the Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, or the Second Arab–Israeli war, also called the Tripartite Aggression ( ar, العدوان الثلاثي, Al-ʿUdwān aṯ-Ṯulāṯiyy) in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel,Also known as the Suez War or 1956 Wa ...

; however, the UN was unable to intervene against the USSR's simultaneous invasion of Hungary following that country's revolution.

On 14 July 1960, the UN established United Nations Operation in the Congo

The United Nations Operation in the Congo (french: Opération des Nations Unies au Congo, abbreviated to ONUC) was a United Nations peacekeeping force deployed in the Republic of the Congo in 1960 in response to the Congo Crisis. ONUC was the ...

(UNOC), the largest military force of its early decades, to bring order to the breakaway State of Katanga

The State of Katanga; sw, Inchi Ya Katanga) also sometimes denoted as the Republic of Katanga, was a breakaway state that proclaimed its independence from Congo-Léopoldville on 11 July 1960 under Moise Tshombe, leader of the local ''Co ...

, restoring it to the control of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (french: République démocratique du Congo (RDC), colloquially "La RDC" ), informally Congo-Kinshasa, DR Congo, the DRC, the DROC, or the Congo, and formerly and also colloquially Zaire, is a country in ...

by 11 May 1964. While traveling to meet rebel leader Moise Tshombe during the conflict, Dag Hammarskjöld, often named as one of the UN's most effective secretaries-general, died in a plane crash; months later he was posthumously awarded the Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Nobel Prize in Chemistry, Chemi ...

. In 1964, Hammarskjöld's successor, U Thant, deployed the UN Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus, which would become one of the UN's longest-running peacekeeping missions.

With the spread of decolonization in the 1960s, the organization's membership saw an influx of newly independent nations. In 1960 alone, 17 new states joined the UN, 16 of them from Africa. On 25 October 1971, with opposition from the United States, but with the support of many Third World

The term "Third World" arose during the Cold War to define countries that remained non-aligned with either NATO or the Warsaw Pact. The United States, Canada, Japan, South Korea, Western European nations and their allies represented the " First ...

nations, the mainland, communist People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

was given the Chinese seat on the Security Council in place of the Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeast ...

; the vote was widely seen as a sign of waning US influence in the organization. Third World nations organized into the Group of 77

The Group of 77 (G77) at the United Nations (UN) is a coalition of 134 developing countries, designed to promote its members' collective economic interests and create an enhanced joint negotiating capacity in the United Nations. There were 77 fou ...

coalition under the leadership of Algeria, which briefly became a dominant power at the UN. On 10 November 1975, a bloc comprising the USSR and Third World nations passed a resolution, over the strenuous US and Israeli opposition, declaring Zionism

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after ''Zion'') is a Nationalism, nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is ...

to be racism; the resolution was repealed on 16 December 1991, shortly after the end of the Cold War.

With an increasing Third World presence and the failure of UN mediation in conflicts in the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

, Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

, and Kashmir

Kashmir () is the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term "Kashmir" denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal Range. Today, the term encompas ...

, the UN increasingly shifted its attention to its ostensibly secondary goals of economic development and cultural exchange. By the 1970s, the UN budget for social and economic development was far greater than its peacekeeping budget.

Post–Cold War (1991–present)

Salvadoran Civil War

The Salvadoran Civil War ( es, guerra civil de El Salvador) was a twelve year period of civil war in El Salvador that was fought between the government of El Salvador and the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN), a coalition or ...

, launched a successful peacekeeping mission in Namibia, and oversaw democratic elections in post-apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

South Africa and post-Khmer Rouge

The Khmer Rouge (; ; km, ខ្មែរក្រហម, ; ) is the name that was popularly given to members of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) and by extension to the regime through which the CPK ruled Cambodia between 1975 and 1979. ...

Cambodia. In 1991, the UN authorized a US-led coalition that repulsed the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. Brian Urquhart, under-secretary-general from 1971 to 1985, later described the hopes raised by these successes as a "false renaissance" for the organization, given the more troubled missions that followed.

Beginning in the last decades of the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

, American and European critics of the UN condemned the organization for perceived mismanagement and corruption. In 1984, US President Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

, withdrew his nation's funding from United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) over allegations of mismanagement, followed by the UK and Singapore. Boutros Boutros-Ghali, secretary-general from 1992 to 1996, initiated a reform of the Secretariat, reducing the size of the organization somewhat. His successor, Kofi Annan (1997–2006), initiated further management reforms in the face of threats from the US to withhold its UN dues.

Though the UN Charter had been written primarily to prevent aggression by one nation against another, in the early 1990s the UN faced a number of simultaneous, serious crises within nations such as Somalia, Haiti, Mozambique, and the former Yugoslavia. The UN mission in Somalia was widely viewed as a failure after the US withdrawal following casualties in the Battle of Mogadishu. The UN mission to Bosnia faced "worldwide ridicule" for its indecisive and confused mission in the face of ethnic cleansing. In 1994, the UN Assistance Mission for Rwanda failed to intervene in the Rwandan genocide

The Rwandan genocide occurred between 7 April and 15 July 1994 during the Rwandan Civil War. During this period of around 100 days, members of the Tutsi minority ethnic group, as well as some moderate Hutu and Twa, were killed by armed Hutu ...

amid indecision in the Security Council.

From the late 1990s to the early 2000s, international interventions authorized by the UN took a wider variety of forms. United Nations Security Council Resolution 1244 authorised the NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

-led Kosovo Force

The Kosovo Force (KFOR) is a North Atlantic Treaty Organization, NATO-led international NATO peacekeeping, peacekeeping force in Kosovo. Its operations are gradually reducing until Kosovo Security Force, Kosovo's Security Force, established in 2 ...

beginning in 1999. The UN mission (1999-2006) in the Sierra Leone Civil War was supplemented by a British military intervention. The invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 was overseen by NATO. In 2003, the United States invaded Iraq despite failing to pass a UN Security Council resolution for authorization, prompting a new round of questioning of the organization's effectiveness.

Under the eighth secretary-general, Ban Ki-moon

Ban Ki-moon (; ; born 13 June 1944) is a South Korean politician and diplomat who served as the eighth secretary-general of the United Nations between 2007 and 2016. Prior to his appointment as secretary-general, Ban was his country's Minister ...

, the UN intervened with peacekeepers in crises such as the War in Darfur

The War in Darfur, also nicknamed the Land Cruiser War, is a major armed conflict in the Darfur region of Sudan that began in February 2003 when the Sudan Liberation Movement (SLM) and the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) rebel groups beg ...

in Sudan and the Kivu conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo and sent observers and chemical weapons inspectors to the Syrian Civil War. In 2013, an internal review of UN actions in the final battles of the Sri Lankan Civil War in 2009 concluded that the organization had suffered "systemic failure". In 2010, the organization suffered the worst loss of life in its history, when 101 personnel died in the Haiti earthquake. Acting under United Nations Security Council Resolution 1973

Resolution 1973 was adopted by the United Nations Security Council on 17 March 2011 in response to the First Libyan Civil War. The resolution formed the legal basis for military intervention in the Libyan Civil War, demanding "an immediate cease ...

in 2011, NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

countries intervened in the Libyan Civil War

Demographics of Libya is the demography of Libya, specifically covering population density, ethnicity, education level, health of the populace, economic status, and religious affiliations, as well as other aspects of the Libyan population. The ...

.

The Millennium Summit was held in 2000 to discuss the UN's role in the 21st century. The three-day meeting was the largest gathering of world leaders in history, and culminated in the adoption by all member states of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), a commitment to achieve international development in areas such as poverty reduction

Poverty reduction, poverty relief, or poverty alleviation, is a set of measures, both economic and humanitarian, that are intended to permanently lift people out of poverty.

Measures, like those promoted by Henry George in his economics clas ...

, gender equality

Gender equality, also known as sexual equality or equality of the sexes, is the state of equal ease of access to resources and opportunities regardless of gender, including economic participation and decision-making; and the state of valuing d ...

, and public health

Public health is "the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organized efforts and informed choices of society, organizations, public and private, communities and individuals". Analyzing the det ...

. Progress towards these goals, which were to be met by 2015, was ultimately uneven. The 2005 World Summit

The 2005 World Summit, held between 14 and 16 September 2005, was a follow-up summit meeting to the United Nations' 2000 Millennium Summit, which had led to the Millennium Declaration of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Representatives ( ...

reaffirmed the UN's focus on promoting development, peacekeeping, human rights, and global security. The Sustainable Development Goals

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) or Global Goals are a collection of 17 interlinked objectives designed to serve as a "shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future".United Nations (2017) R ...

were launched in 2015 to succeed the Millennium Development Goals.

In addition to addressing global challenges, the UN has sought to improve its accountability and democratic legitimacy by engaging more with civil society and fostering a global constituency. In an effort to enhance transparency, in 2016 the organization held its first public debate between candidates for secretary-general. On 1 January 2017, Portuguese diplomat António Guterres

António Manuel de Oliveira Guterres ( , ; born 30 April 1949) is a Portuguese politician and diplomat. Since 2017, he has served as secretary-general of the United Nations, the ninth person to hold this title. A member of the Portuguese Socia ...

, who previously served as UN High Commissioner for Refugees

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) is a United Nations agency mandated to aid and protect refugees, forcibly displaced communities, and stateless people, and to assist in their voluntary repatriation, local integratio ...

, became the ninth secretary-general. Guterres has highlighted several key goals for his administration, including an emphasis on diplomacy for preventing conflicts, more effective peacekeeping efforts, and streamlining the organization to be more responsive and versatile to global needs.

Structure

The United Nations is part of the broaderUN system

The United Nations System consists of the United Nations' six principal organs (the General Assembly, Security Council, Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), Trusteeship Council, International Court of Justice (ICJ), and the UN Secretariat), ...

, which includes an extensive network of institutions and entities. Central to the organisation are five principal organs established by the UN Charter: the General Assembly

A general assembly or general meeting is a meeting of all the members of an organization or shareholders of a company.

Specific examples of general assembly include:

Churches

* General Assembly (presbyterian church), the highest court of presby ...

(UNGA), the Security Council (UNSC), the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), the International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; french: Cour internationale de justice, links=no; ), sometimes known as the World Court, is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN). It settles disputes between states in accordanc ...

(ICJ) and the UN Secretariat. A sixth principal organ, the Trusteeship Council

The United Nations Trusteeship Council (french: links=no, Conseil de tutelle des Nations unies) is one of the organs of the United Nations, six principal organs of the United Nations, established to help ensure that United Nations Trust Territor ...

, suspended operations on 1 November 1994, upon the independence of Palau

Palau,, officially the Republic of Palau and historically ''Belau'', ''Palaos'' or ''Pelew'', is an island country and microstate in the western Pacific. The nation has approximately 340 islands and connects the western chain of the Caro ...

, the last remaining UN trustee territory.

Four of the five principal organs are located at the main UN Headquarters in New York City, while the ICJ is seated in The Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a city and municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's administrative centre and its seat of government, and while the official capital of ...

. Most other major agencies are based in the UN offices at Geneva, Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, and Nairobi

Nairobi ( ) is the capital and largest city of Kenya. The name is derived from the Maasai phrase ''Enkare Nairobi'', which translates to "place of cool waters", a reference to the Nairobi River which flows through the city. The city proper ha ...

; additional UN institutions are located throughout the world. The six official language

An official language is a language given supreme status in a particular country, state, or other jurisdiction. Typically the term "official language" does not refer to the language used by a people or country, but by its government (e.g. judiciary, ...

s of the UN, used in intergovernmental meetings and documents, are Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

, Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of va ...

, English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

, French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

, Russian, and Spanish. On the basis of the Convention on the Privileges and Immunities of the United Nations, the UN and its agencies are immune

In biology, immunity is the capability of multicellular organisms to resist harmful microorganisms. Immunity involves both specific and nonspecific components. The nonspecific components act as barriers or eliminators of a wide range of pathogens ...

from the laws of the countries where they operate, safeguarding the UN's impartiality with regard to host and member countries.

Below the six organs sit, in the words of the author Linda Fasulo, "an amazing collection of entities and organizations, some of which are actually older than the UN itself and operate with almost complete independence from it". These include specialized agencies, research and training institutions, programs and funds, and other UN entities.

All organisations in the UN system obey the ''Noblemaire principle'', which calls for salaries that will attract and retain citizens of countries where compensation is highest, and which ensures equal pay for work of equal value regardless of the employee's nationality.Salaries, United Nations website In practice, the International Civil Service Commission, which governs the conditions of UN personnel, takes reference to the highest-paying national civil service. Staff salaries are subject to an internal tax that is administered by the UN organizations.

General Assembly

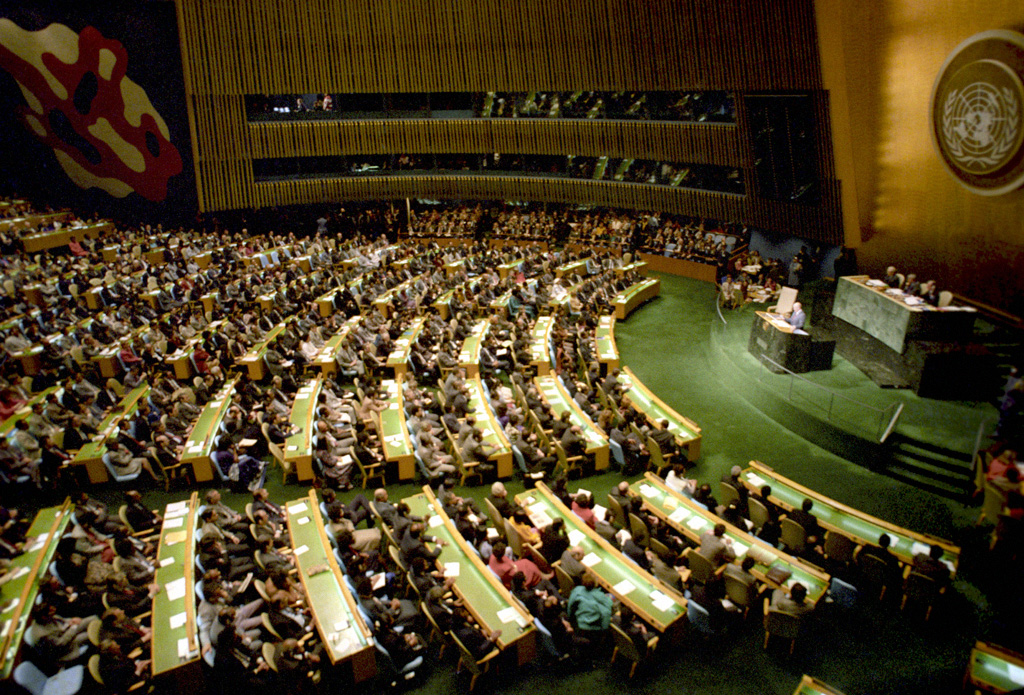

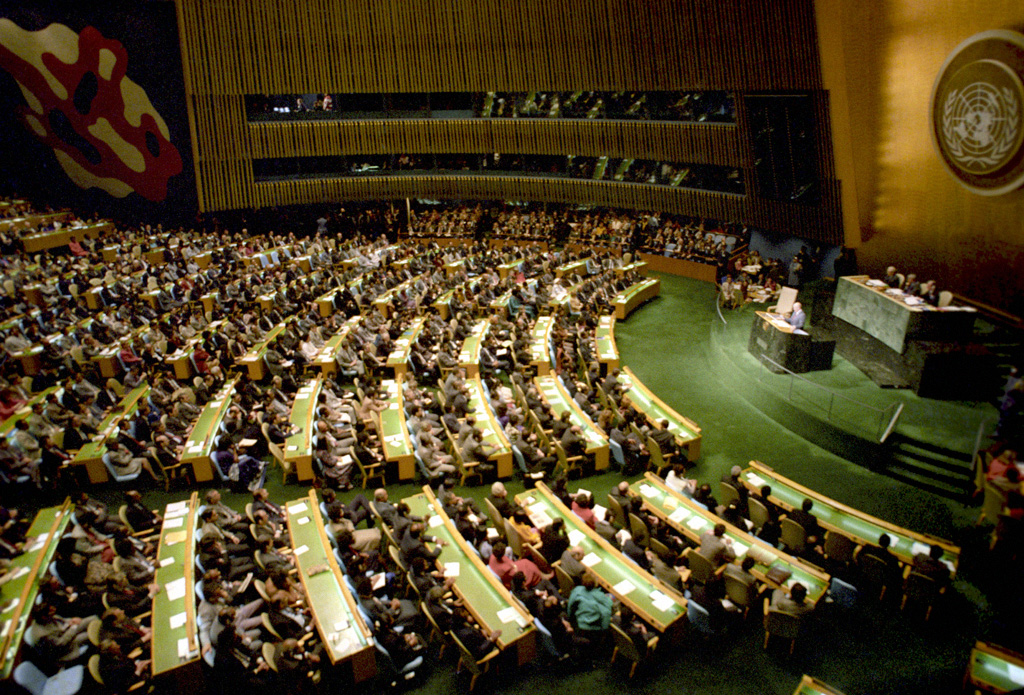

The General Assembly is the main

The General Assembly is the main deliberative assembly

A deliberative assembly is a meeting of members who use parliamentary procedure.

Etymology

In a speech to the electorate at Bristol in 1774, Edmund Burke described the British Parliament as a "deliberative assembly," and the expression became the ...

of the UN. Composed of all UN member states

The United Nations member states are the sovereign states that are members of the United Nations (UN) and have equal representation in the United Nations General Assembly, UN General Assembly. The UN is the world's largest international o ...

, the assembly meets in regular yearly sessions at the General Assembly Hall, but emergency sessions can also be called. The assembly is led by a president

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

, elected from among the member states on a rotating regional basis, and 21 vice-presidents. The first session convened 10 January 1946 in the Methodist Central Hall in London and included representatives of 51 nations.

When the General Assembly decides on important questions such as those on peace and security, admission of new members and budgetary matters, a two-thirds majority of those present and voting is required. All other questions are decided by a majority vote. Each member country has one vote. Apart from the approval of budgetary matters, resolutions are not binding on the members. The Assembly may make recommendations on any matters within the scope of the UN, except matters of peace and security that are under consideration by the Security Council.

Draft resolutions can be forwarded to the General Assembly by its six main committees:

* First Committee (Disarmament and International Security)

* Second Committee (Economic and Financial)

* Third Committee (Social, Humanitarian, and Cultural)

* Fourth Committee (Special Political and Decolonization)

* Fifth Committee (Administrative and Budgetary)

* Sixth Committee (Legal)

As well as by the following two committees:

* General Committee

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED O ...

– a supervisory committee consisting of the assembly's president, vice-president, and committee heads

* Credentials Committee – responsible for determining the credentials of each member nation's UN representatives

Security Council

The Security Council is charged with maintaining peace and security among countries. While other organs of the UN can only make "recommendations" to member states, the Security Council has the power to make binding decisions that member states have agreed to carry out, under the terms of Charter Article 25. The decisions of the council are known as

The Security Council is charged with maintaining peace and security among countries. While other organs of the UN can only make "recommendations" to member states, the Security Council has the power to make binding decisions that member states have agreed to carry out, under the terms of Charter Article 25. The decisions of the council are known as United Nations Security Council resolution

A United Nations Security Council resolution is a United Nations resolution adopted by the fifteen members of the Security Council (UNSC); the United Nations (UN) body charged with "primary responsibility for the maintenance of international peac ...

s.

The Security Council is made up of fifteen member states, consisting of five permanent members—China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States—and ten non-permanent members elected for two-year terms by the General Assembly: Albania

Albania ( ; sq, Shqipëri or ), or , also or . officially the Republic of Albania ( sq, Republika e Shqipërisë), is a country in Southeastern Europe. It is located on the Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea and shares ...

(term ends 2023), Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

(2023), Gabon

Gabon (; ; snq, Ngabu), officially the Gabonese Republic (french: République gabonaise), is a country on the west coast of Central Africa. Located on the equator, it is bordered by Equatorial Guinea to the northwest, Cameroon to the north ...

(2023), Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and To ...

(2023), India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

(2022),