Umberto II on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Umberto II (; 15 September 190418 March 1983) was the last

Umberto was born at the Castle of Racconigi in

Umberto was born at the Castle of Racconigi in

Umberto earned widespread praise for his role in the following three years, with the Italian historian Giuseppe Mammarella calling Umberto a man "whose Fascist past was less compromising" than that of Victor Emmanuel and who, as Lieutenant General of the Realm, showed certain "progressive" tendencies. In April 1946, a public opinion poll of registered members of the conservative Christian Democratic party showed that 73% were republicans, a poll that caused immense panic in the monarchist camp.Norman Kogan ''A Political History of Postwar Italy'', London: Pall Mall Press, 1966 p. 37 The American historian Norman Kogan cautioned the poll was of Christian Democratic members, which was not the same thing as Christian Democratic voters who tended to be "...rural, female, or generally apolitical". Nonetheless, the poll led to appeals from Umberto to the ACC to postpone the referendum, leading to the reply that the De Gasperi cabinet had set the date for the referendum, not the ACC. The possibility of losing the referendum also led to the monarchists to appeal to Victor Emmanuel to finally abdicate. De Gasperi and the other Christian Democratic leaders refused to take sides in the referendum, urging Christian Democratic voters to follow their consciences when it came time to vote.Giuseppe Mammarealla ''Italy After Fascism A Political History 1943–1965'', Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1966 p. 114

In the belated hope of influencing public opinion ahead of a referendum on the continuation of the monarchy, Victor Emmanuel formally abdicated in favour of Umberto on 9 May 1946 and left for Egypt. Before departing for Egypt, Victor Emmanuel saw Umberto for the last time, saying farewell in a cold, emotionless way. The Catholic Church saw the continuation of the monarchy as the best way of keeping the Italian left out of power, and during the referendum campaign, Catholic priests used their pulpits to warn that "all the pains of hell" were reserved for those who voted for a republic.Denis Mack Smith, ''Italy and Its Monarchy'', New Haven: Yale University Press p. 339 The Catholic Church presented the referendum not as a question of republic vs monarchy, but instead as a question of Communism vs Catholicism, warning to vote for a republic would be to vote for the Communists. On the day before the referendum, 1 June 1946,

Umberto earned widespread praise for his role in the following three years, with the Italian historian Giuseppe Mammarella calling Umberto a man "whose Fascist past was less compromising" than that of Victor Emmanuel and who, as Lieutenant General of the Realm, showed certain "progressive" tendencies. In April 1946, a public opinion poll of registered members of the conservative Christian Democratic party showed that 73% were republicans, a poll that caused immense panic in the monarchist camp.Norman Kogan ''A Political History of Postwar Italy'', London: Pall Mall Press, 1966 p. 37 The American historian Norman Kogan cautioned the poll was of Christian Democratic members, which was not the same thing as Christian Democratic voters who tended to be "...rural, female, or generally apolitical". Nonetheless, the poll led to appeals from Umberto to the ACC to postpone the referendum, leading to the reply that the De Gasperi cabinet had set the date for the referendum, not the ACC. The possibility of losing the referendum also led to the monarchists to appeal to Victor Emmanuel to finally abdicate. De Gasperi and the other Christian Democratic leaders refused to take sides in the referendum, urging Christian Democratic voters to follow their consciences when it came time to vote.Giuseppe Mammarealla ''Italy After Fascism A Political History 1943–1965'', Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1966 p. 114

In the belated hope of influencing public opinion ahead of a referendum on the continuation of the monarchy, Victor Emmanuel formally abdicated in favour of Umberto on 9 May 1946 and left for Egypt. Before departing for Egypt, Victor Emmanuel saw Umberto for the last time, saying farewell in a cold, emotionless way. The Catholic Church saw the continuation of the monarchy as the best way of keeping the Italian left out of power, and during the referendum campaign, Catholic priests used their pulpits to warn that "all the pains of hell" were reserved for those who voted for a republic.Denis Mack Smith, ''Italy and Its Monarchy'', New Haven: Yale University Press p. 339 The Catholic Church presented the referendum not as a question of republic vs monarchy, but instead as a question of Communism vs Catholicism, warning to vote for a republic would be to vote for the Communists. On the day before the referendum, 1 June 1946,

Genealogy of recent members of the House of Savoy

* , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Umberto II of Italy 1904 births 1983 deaths 20th-century kings of Italy 20th-century Italian military personnel 20th-century Italian LGBTQ people 20th-century Roman Catholics 20th-century regents Claimant kings of Jerusalem Princes in Italy Princes of Piedmont Princes of Savoy Dukes in Italy Field marshals of Italy Italian admirals Italian monarchists Italian exiles Italian LGBTQ military personnel Italian military personnel of World War II Italian people of Montenegrin descent Exiled royalty People from Cascais Burials at Hautecombe Abbey People from Racconigi Knights Grand Cross of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus Grand Crosses of the Order of Christ (Portugal) Knights of the Golden Fleece of Spain Recipients of the Order of the White Eagle (Poland) Grand Crosses of the Order of Saint-Charles Sons of emperors Children of Victor Emmanuel III LGBTQ heads of state LGBTQ Roman Catholics LGBTQ royalty

King of Italy

King is a royal title given to a male monarch. A king is an absolute monarch if he holds unrestricted governmental power or exercises full sovereignty over a nation. Conversely, he is a constitutional monarch if his power is restrained by ...

. Umberto's reign lasted for 34 days, from 9 May 1946 until his formal deposition on 12 June 1946, although he had been the ''de facto'' head of state

A head of state is the public persona of a sovereign state.#Foakes, Foakes, pp. 110–11 "

since 1944. Due to his short reign, he was nicknamed the May King ().

Umberto was the third child and only son among the five children of he head of state

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (letter), the fifth letter of the Semitic abjads

* He (pronoun), a pronoun in Modern English

* He (kana), one of the Japanese kana (へ in hiragana and ヘ in katakana)

* Ge (Cyrillic), a Cyrillic letter cal ...

being an embodiment of the State itself or representative of its international persona." The name given to the office of head of sta ...Victor Emmanuel III of Italy

Victor Emmanuel III (; 11 November 1869 – 28 December 1947) was King of Italy from 29 July 1900 until his abdication on 9 May 1946. A member of the House of Savoy, he also reigned as Emperor of Ethiopia from 1936 to 1941 and King of the Albania ...

and Elena of Montenegro. As heir apparent to the throne, he received a customary military education and pursued a military career afterwards. In 1940, he commanded an army group during the brief Italian invasion of France

The Italian invasion of France (10–25 June 1940), also called the Battle of the Alps, was the first major Fascist Italy, Italian engagement of World War II and the last major engagement of the Battle of France.

The Italian entry into the war ...

shortly before the French capitulation. In 1942, he was promoted to Marshal of Italy

Marshal of Italy () was a rank in the Royal Italian Army (''Regio Esercito''). Originally created in 1924 by Italian dictator Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and jo ...

but was otherwise inactive as an army commander during much of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. Umberto turned against the war following Italian defeats at Stalingrad

Volgograd,. geographical renaming, formerly Tsaritsyn. (1589–1925) and Stalingrad. (1925–1961), is the largest city and the administrative centre of Volgograd Oblast, Russia. The city lies on the western bank of the Volga, covering an area o ...

and El Alamein, and tacitly supported the ouster of Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

.

In 1944, Victor Emmanuel, compromised by his association with Italian fascism

Italian fascism (), also called classical fascism and Fascism, is the original fascist ideology, which Giovanni Gentile and Benito Mussolini developed in Italy. The ideology of Italian fascism is associated with a series of political parties le ...

and desperate to repair the monarchy's image, transferred most of his powers to Umberto. He transferred his remaining powers to Umberto later in 1944 and named him Lieutenant General ('' Luogotenente'') of the Realm; while retaining the title of King. As the country prepared for the 1946 Italian institutional referendum

An institutional referendum (, or ) was held by universal suffrage in the Kingdom of Italy on 2 June 1946, a key event of contemporary Italian history. Until 1946, Italy was a kingdom ruled by the House of Savoy, reigning since the unification ...

on the continuation of the Italian monarchy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

, Victor Emmanuel abdicated his throne in favour of Umberto, aspiring to bolster the monarchy with his exit. The June 1946 referendum saw voters voting to abolish the monarchy, and Italy was declared a republic days later. Umberto departed the country; he and other male members of the House of Savoy were barred from returning. He lived out the rest of his life in exile in Cascais

Cascais () is a town and municipality in the Lisbon District of Portugal, located on the Portuguese Riviera, Estoril Coast. The municipality has a total of 214,158 inhabitants in an area of 97.40 km2. Cascais is an important tourism in Port ...

, on the Portuguese Riviera

The Portuguese Riviera (Portuguese language, Portuguese: ''Riviera Portuguesa'') is a term used for the affluent coastal region to the west of Lisbon, Portugal, centered on the coastal municipalities of Cascais (including Estoril), Oeiras, Portug ...

. He died in Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

Cantonal Hospital in 1983.

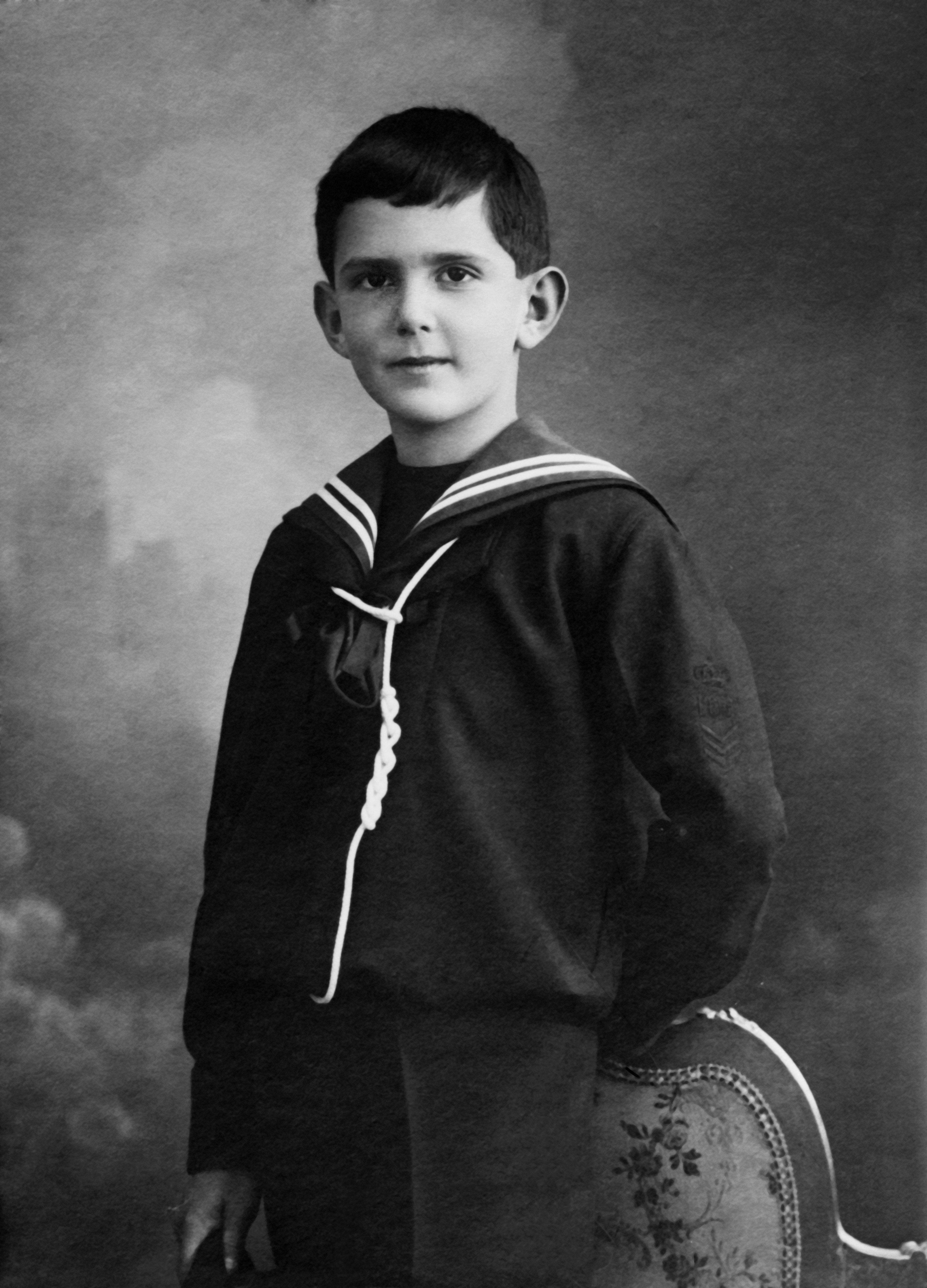

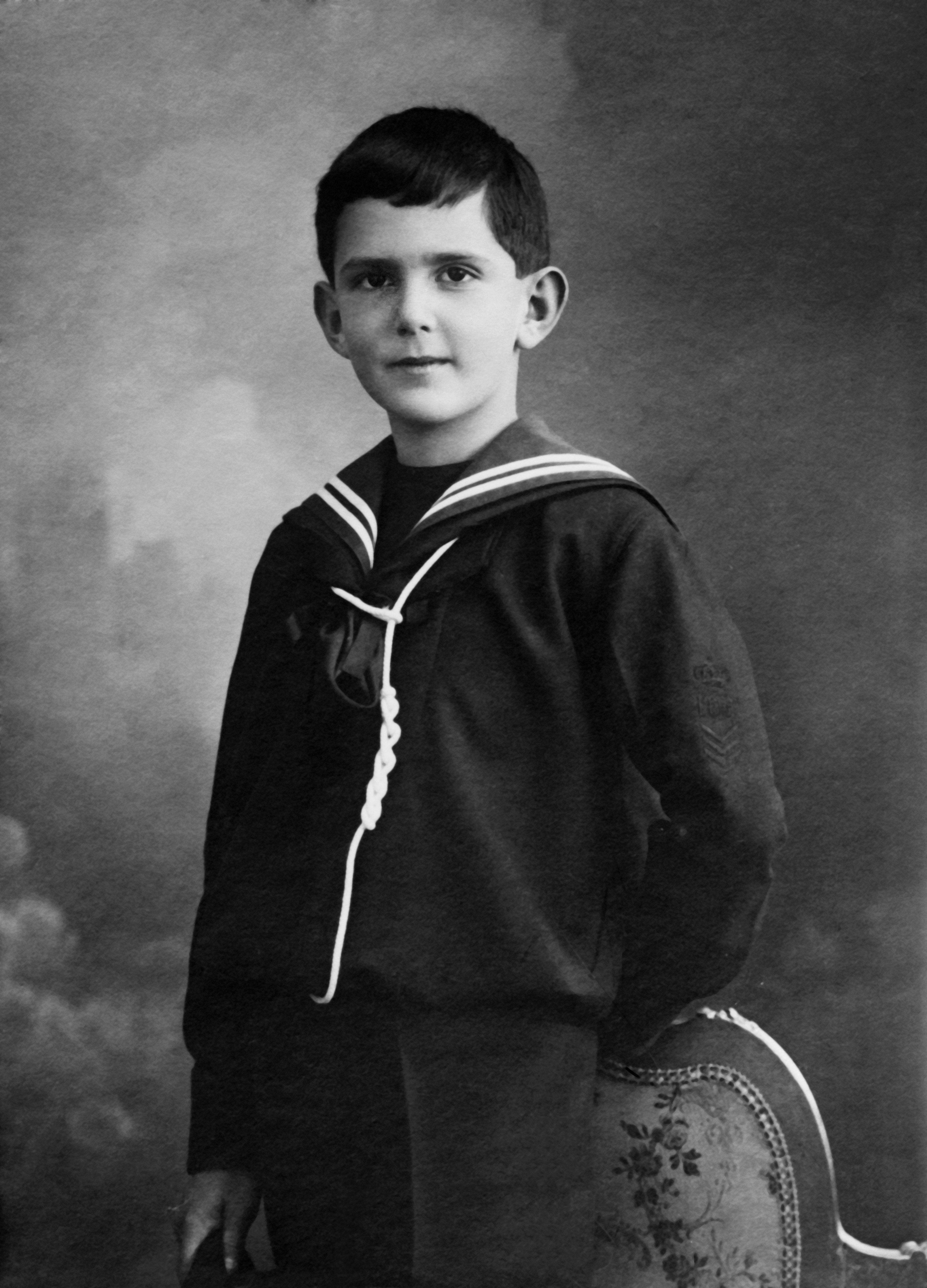

Early life

Umberto was born at the Castle of Racconigi in

Umberto was born at the Castle of Racconigi in Piedmont

Piedmont ( ; ; ) is one of the 20 regions of Italy, located in the northwest Italy, Northwest of the country. It borders the Liguria region to the south, the Lombardy and Emilia-Romagna regions to the east, and the Aosta Valley region to the ...

. He was the third child and the only son of King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy

Victor Emmanuel III (; 11 November 1869 – 28 December 1947) was King of Italy from 29 July 1900 until his abdication on 9 May 1946. A member of the House of Savoy, he also reigned as Emperor of Ethiopia from 1936 to 1941 and King of the Albania ...

and his wife, Jelena of Montenegro. As such, he was heir apparent

An heir apparent is a person who is first in the order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person. A person who is first in the current order of succession but could be displaced by the birth of a more e ...

from birth since the Italian throne was limited to male descendants. He was accorded the title Prince of Piedmont

The lordship of Piedmont, later the principality of Piedmont (), was originally an appanage of the County of Savoy, and as such its lords were members of the Principality of Achaea#Princes of Achaea, Achaea branch of the House of Savoy. The titl ...

, which the Royal Decree formalised on 29 September 1904.

During the crisis of May 1915, when Victor Emmanuel III decided to break the terms of the Triple Alliance by declaring war on the Austro-Hungarian Empire

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military and diplomatic alliance, it consist ...

, he found himself in a quandary as the Italian Parliament

The Italian Parliament () is the national parliament of the Italy, Italian Republic. It is the representative body of Italian citizens and is the successor to the Parliament of the Kingdom of Sardinia (1848–1861), the Parliament of the Kingd ...

was against declaring war; several times, the king discussed abdication, with the throne to pass to the 2nd Duke of Aosta instead of Umberto. The British historian Denis Mack Smith wrote that it is not entirely clear why Victor Emmanuel was prepared to sacrifice his 10-year-old son's right to succeed to the throne in favour of the Duke of Aosta.

Umberto was brought up in an authoritarian and militaristic household and was expected to "show an exaggerated deference to his father"; both in private and public, Umberto always had to get down on his knees and kiss his father's hand before being allowed to speak, even as an adult,Denis Mack Smith, ''Italy and Its Monarchy'', New Haven: Yale University Press p. 272 and he was expected to stand to attention and salute whenever his father entered a room. Umberto was given the formal military education of a Savoyard prince and like the other Savoyard princes before him, Umberto received an education that was notably short on politics; Savoyard monarchs customarily excluded politics from their heirs' education with the expectation that they would learn about the art of politics when they inherited the throne.

Umberto was the first cousin of King Alexander I of Yugoslavia

Alexander I Karađorđević (, ; – 9 October 1934), also known as Alexander the Unifier ( / ), was King of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes from 16 August 1921 to 3 October 1929 and King of Yugoslavia from 3 October 1929 until Alexander I of Y ...

. In a 1959 interview, Umberto told the Italian newspaper ''La Settimana Incom Illustrata'' that in 1922 his father had felt that appointing Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

as prime minister was a "justifiable risk".

Career as Prince of Piedmont

State visit to South America, 1924

AsPrince of Piedmont

The lordship of Piedmont, later the principality of Piedmont (), was originally an appanage of the County of Savoy, and as such its lords were members of the Principality of Achaea#Princes of Achaea, Achaea branch of the House of Savoy. The titl ...

, Umberto visited South America, between July and September 1924. With his preceptor

A preceptor (from Latin, "''praecepto''") is a teacher responsible for upholding a ''precept'', meaning a certain law or tradition.

Buddhist monastic orders

Senior Buddhist monks can become the preceptors for newly ordained monks. In the Buddhi ...

, Bonaldi, he went to Brazil, Uruguay, Argentina and Chile. This trip was part of the political plan of Fascism to link the Italian people living outside of Italy with their mother country and the interests of the regime. In Brazil, visits were scheduled to the national capital Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro, or simply Rio, is the capital of the Rio de Janeiro (state), state of Rio de Janeiro. It is the List of cities in Brazil by population, second-most-populous city in Brazil (after São Paulo) and the Largest cities in the America ...

and the State of São Paulo

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

, where the largest Italian colony in the country lived. However, a major rebellion broke out on 5 July 1924, when Umberto had already departed from Europe, imposing a change in the Royal tour. The prince had to stop in Salvador, the capital of Bahia

Bahia () is one of the 26 Federative units of Brazil, states of Brazil, located in the Northeast Region, Brazil, Northeast Region of the country. It is the fourth-largest Brazilian state by population (after São Paulo (state), São Paulo, Mina ...

, to supply the ships, going directly to the other countries of South America. On his return, Umberto could only be received in Salvador again. Governor Góis Calmon, the Italian colony and other entities warmly welcomed the heir to the Italian Throne.

Military positions and attempted assassination

Umberto was educated for a military career and in time became the commander-in-chief of the Northern Armies, and then the Southern ones. This role was merely formal, the ''de facto'' command belonging to his father, King Victor Emmanuel III, who jealously guarded his power of supreme command from '' Il Duce'',Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

. By mutual agreement, Umberto and Mussolini always kept a distance. In 1926, Mussolini passed a law allowing the Fascist Grand Council to decide the succession, though in practice he admitted the prince would succeed his father.

An attempted assassination took place in Brussels

Brussels, officially the Brussels-Capital Region, (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) is a Communities, regions and language areas of Belgium#Regions, region of Belgium comprising #Municipalit ...

on 24 October 1929, the day of the announcement of his betrothal to Princess Marie José. Umberto was about to lay a wreath on the Tomb of the Belgian Unknown Soldier at the foot of the '' Colonne du Congrès'' when, with a cry of 'Down with Mussolini!', Fernando de Rosa fired a single shot that missed him.

De Rosa was arrested and, under interrogation, claimed to be a member of the Second International

The Second International, also called the Socialist International, was a political international of Labour movement, socialist and labour parties and Trade union, trade unions which existed from 1889 to 1916. It included representatives from mo ...

who had fled Italy to avoid arrest for his political views. His trial was a major political event, and although he was found guilty of attempted murder, he was given a light sentence of five years in prison. This sentence caused a political uproar in Italy and a brief rift in Belgian-Italian relations, but in March 1932 Umberto asked for a pardon

A pardon is a government decision to allow a person to be relieved of some or all of the legal consequences resulting from a criminal conviction. A pardon may be granted before or after conviction for the crime, depending on the laws of the j ...

for de Rosa, who was released after having served slightly less than half his sentence and was eventually killed in the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

.

Visit to Italian Somaliland

In 1928, after the colonial authorities inItalian Somaliland

Italian Somaliland (; ; ) was a protectorate and later colony of the Kingdom of Italy in present-day Somalia, which was ruled in the 19th century by the Sultanate of Hobyo and the Majeerteen Sultanate in the north, and by the Hiraab Imamate and ...

built Mogadishu Cathedral (''Cattedrale di Mogadiscio''), Umberto made his first publicised visit to Mogadishu

Mogadishu, locally known as Xamar or Hamar, is the capital and List of cities in Somalia by population, most populous city of Somalia. The city has served as an important port connecting traders across the Indian Ocean for millennia and has ...

, the territory's capital. Umberto made his second publicised visit to Italian Somaliland in October 1934.

Marriage and issue

Umberto was married in the city of Rome on 8 January 1930 toPrincess

Princess is a title used by a female member of a regnant monarch's family or by a female ruler of a principality. The male equivalent is a prince (from Latin '' princeps'', meaning principal citizen). Most often, the term has been used for ...

Marie José of Belgium (1906–2001), the daughter of King Albert I of the Belgians and his wife, Queen Elisabeth (''née'' Duchess Elisabeth in Bavaria

Bavaria, officially the Free State of Bavaria, is a States of Germany, state in the southeast of Germany. With an area of , it is the list of German states by area, largest German state by land area, comprising approximately 1/5 of the total l ...

).

They had four children:

* Princess Maria Pia (born 1934)

* Prince Vittorio Emanuele (1937–2024)

* Princess Maria Gabriella (born 1940)

* Princess Maria Beatrice (born 1943)

Under the Fascist Regime

Following the Savoyards' tradition ("Only one Savoy reigns at a time"), Umberto was kept apart from active politics until he was named Lieutenant General of the Realm. He made an exception whenAdolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

asked for a meeting. This was not considered proper, given the international situation; thereafter, Umberto was more rigorously excluded from political events. In 1935, Umberto supported the war against the Ethiopian Empire

The Ethiopian Empire, historically known as Abyssinia or simply Ethiopia, was a sovereign state that encompassed the present-day territories of Ethiopia and Eritrea. It existed from the establishment of the Solomonic dynasty by Yekuno Amlak a ...

, which he called a "legitimate war" that even Giovanni Giolitti

Giovanni Giolitti (; 27 October 1842 – 17 July 1928) was an Italian statesman. He was the prime minister of Italy five times between 1892 and 1921. He is the longest-serving democratically elected prime minister in Italian history, and the sec ...

would have supported had he still been alive.Denis Mack Smith, ''Italy and Its Monarchy'', New Haven: Yale University Press p. 271 Umberto wanted to serve in the Ethiopian war, but was prevented from doing so by his father, who did, however, allow four royal dukes to serve in East Africa. Umberto conformed to his father's expectations and behaved like an army officer; the prince obediently got down on his knees to kiss his father's hand before speaking. However, Umberto privately resented what he regarded as a deeply humiliating relationship with his cold and emotionally distant father. Umberto's attitude toward the Fascist regime varied: at times, he mocked the more pompous aspects of Fascism and his father for supporting such a regime, while at other times, he praised Mussolini as a great leader.

Italian expansion during the Second World War

Umberto shared his father's fears that Mussolini's policy of alliance withNazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

was reckless and dangerous, but he made no move to oppose Italy becoming one of the Axis powers

The Axis powers, originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis and also Rome–Berlin–Tokyo Axis, was the military coalition which initiated World War II and fought against the Allies of World War II, Allies. Its principal members were Nazi Ge ...

. When Mussolini decided to enter the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

in June 1940, Umberto hinted to his father that he should use the royal veto to block the Italian declarations of war on Britain and France, but was ignored.Denis Mack Smith, ''Italy and Its Monarchy'', New Haven: Yale University Press p. 291 After the war, Umberto criticised the decision to enter the war, saying that Victor Emmanuel was too much under "Mussolini's spell" in June 1940 to oppose it. Following Italy's entry into the war, Umberto ostensibly commanded ''Army Group West'', made up of the First, Fourth and the Seventh Army (kept in reserve), which attacked French forces during the Italian invasion of France

The Italian invasion of France (10–25 June 1940), also called the Battle of the Alps, was the first major Fascist Italy, Italian engagement of World War II and the last major engagement of the Battle of France.

The Italian entry into the war ...

. Umberto was appointed to this position by his father, who wanted the expected Italian victory to also be a victory for the House of Savoy, as the King feared Mussolini's ambitions.Denis Mack Smith, ''Italy and Its Monarchy'', New Haven: Yale University Press p. 292 A few hours after France signed an armistice with Germany on 21 June 1940, the Italians invaded France. The Italian offensive was a complete fiasco, with Umberto's reputation as a general only being saved by the fact that the already defeated French signed an armistice with Italy on 24 June 1940. Thus, he could present the offensive as a victory. The Italian plans called for the ''Regio Esercito

The Royal Italian Army () (RE) was the land force of the Kingdom of Italy, established with the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy. During the 19th century Italy started to unify into one country, and in 1861 Manfredo Fanti signed a decree c ...

'' to reach the Rhone river valley, which the Italians came nowhere close to reaching, having penetrated only a few kilometres into France.

After the capitulation of France, Mussolini kept Umberto inactive as an Army commander. In the summer of 1940, Umberto was to command a planned invasion of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was a country in Southeast Europe, Southeast and Central Europe that existed from 1918 until 1941. From 1918 to 1929, it was officially called the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, but the term "Yugoslavia" () h ...

. Still, Mussolini subsequently cancelled the invasion of Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

in favour of invading the Kingdom of Greece

The Kingdom of Greece (, Romanization, romanized: ''Vasíleion tis Elládos'', pronounced ) was the Greece, Greek Nation state, nation-state established in 1832 and was the successor state to the First Hellenic Republic. It was internationally ...

. In June 1941, supported by his father, Umberto strongly lobbied to be given command of the Italian expeditionary force sent to the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, saying that, as a Catholic, he fully supported Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and several of its European Axis allies starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during World War II. More than 3.8 million Axis troops invaded the western Soviet Union along ...

and wanted to do battle with the "godless communists".Denis Mack Smith, ''Italy and Its Monarchy'', New Haven: Yale University Press p. 298 Mussolini refused the request, and instead gave Umberto the responsibility of training the Italian forces scheduled to participate in Operation Hercules, the planned Axis invasion of Malta

Malta, officially the Republic of Malta, is an island country in Southern Europe located in the Mediterranean Sea, between Sicily and North Africa. It consists of an archipelago south of Italy, east of Tunisia, and north of Libya. The two ...

. On 29 October 1942, he was awarded the rank of Marshal of Italy

Marshal of Italy () was a rank in the Royal Italian Army (''Regio Esercito''). Originally created in 1924 by Italian dictator Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and jo ...

(''Maresciallo d'Italia''). During October–November 1942, in the Battle of El Alamein, the Italo-German force was defeated by the British Eighth Army, marking the end of Axis hopes of conquering Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

. The Axis retreated back into Libya

Libya, officially the State of Libya, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya border, the east, Sudan to Libya–Sudan border, the southeast, Chad to Chad–L ...

. In November 1942, as part of the Battle of Stalingrad

The Battle of Stalingrad ; see . rus, links=on, Сталинградская битва, r=Stalingradskaya bitva, p=stəlʲɪnˈɡratskəjə ˈbʲitvə. (17 July 19422 February 1943) was a major battle on the Eastern Front of World War II, ...

, the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

launched Operation Uranus

Operation Uranus () was a Soviet 19–23 November 1942 strategic operation on the Eastern Front of World War II which led to the encirclement of Axis forces in the vicinity of Stalingrad: the German Sixth Army, the Third and Fourth Romani ...

, which saw the Soviets annihilate much of the Italian expeditionary force in Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

and encircle the German 6th Army. The disastrous Italian defeats at Stalingrad and El Alamein turned Umberto against the war and led him to conclude that Italy must sign an armistice before it was too late. In late 1942, Umberto had his cousin, the 4th Duke of Aosta, visit Switzerland to contact the British consulate in Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

, where he passed on a message to London that the King was willing to sign an armistice with the Allies in exchange for a promise that he be allowed to keep his throne.

Attempts at armistice

In 1943, Marie José, Princess of Piedmont, involved herself in vain attempts to arrange a separate peace treaty between Italy and theUnited States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

. Her interlocutor from the Vatican

Vatican may refer to:

Geography

* Vatican City, an independent city-state surrounded by Rome, Italy

* Vatican Hill, in Rome, namesake of Vatican City

* Ager Vaticanus, an alluvial plain in Rome

* Vatican, an unincorporated community in the ...

was Giovanni Battista Monsignor

Monsignor (; ) is a form of address or title for certain members of the clergy in the Catholic Church. Monsignor is the apocopic form of the Italian ''monsignore'', meaning "my lord". "Monsignor" can be abbreviated as Mons.... or Msgr. In some ...

Montini, a senior Papal diplomat who later became Pope Paul VI

Pope Paul VI (born Giovanni Battista Enrico Antonio Maria Montini; 26 September 18976 August 1978) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 21 June 1963 until his death on 6 August 1978. Succeeding John XXII ...

. Her attempts were not sponsored by her father-in-law, the King, and Umberto was not (directly at least) involved in them. Victor Emmanuel III was anti-clerical, distrusting the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, and wanted nothing to do with a peace attempt made through Papal

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the pope was the sovereign or head of sta ...

intermediaries. More importantly, Victor Emmanuel was proudly misogynistic

Misogyny () is hatred of, contempt for, or prejudice against women or girls. It is a form of sexism that can keep women at a lower social status than men, thus maintaining the social roles of patriarchy. Misogyny has been widely practis ...

, holding women in complete contempt as the King believed it to be a scientific fact that the brains of women were significantly less developed than the brains of men. Victor Emmanuel simply did not believe that Marie José was competent to serve as a diplomat. For all these reasons, the King vetoed Marie José's peace attempt. After her failure – she never met the American agents – she was sent with her children to Sarre, in the Aosta Valley

The Aosta Valley ( ; ; ; or ), officially the Autonomous Region of Aosta Valley, is a mountainous Regions of Italy#Autonomous regions with special statute, autonomous region in northwestern Italy. It is bordered by Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, Fr ...

, and isolated from the political life of the Royal House.

In the first half of 1943, as the war continued to go badly for Italy, several senior Fascist officials, upon learning that the Allies would never sign an armistice with Mussolini, began to plot his overthrow with the support of the King.Denis Mack Smith, ''Italy and Its Monarchy'', New Haven: Yale University Press p. 300 Adding to their worries were a number of strikes in Milan

Milan ( , , ; ) is a city in northern Italy, regional capital of Lombardy, the largest city in Italy by urban area and the List of cities in Italy, second-most-populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of nea ...

starting on 5 March 1943, with the workers openly criticising both the war and the Fascist regime which had led Italy into the war, leading to fears in Rome that Italy was on the brink of revolution. The strike wave in Milan quickly spread to the industrial city of Turin

Turin ( , ; ; , then ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital from 1861 to 1865. The city is main ...

, where the working class likewise denounced the war and Fascism.Gerhard Weinberg, ''A World in Arms'', Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 485 The fact that during the strikes in Milan and Turin, Italian soldiers fraternised with the striking workers, who used slogans associated with the banned Socialist and Communist parties, deeply worried Italy's conservative establishment. By this point, the successive Italian defeats had so psychologically shattered Mussolini that he become close to being catatonic, staring into space for hours on end and saying the war would soon turn around for the Axis because it had to, leading even his closest admirers to become disillusioned and to begin looking for a new leader. Umberto was seen as supportive of these efforts to depose Mussolini, but as Ciano (who had turned against Mussolini by this point) complained in his diary, the prince was far too passive, refusing to make a move or even state his views unless his father expressed his approval first.

On 10 July 1943, in Operation Husky

Operation or Operations may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* ''Operation'' (game), a battery-operated board game that challenges dexterity

* Operation (music), a term used in musical set theory

* ''Operations'' (magazine), Multi-Man ...

, the Allies invaded Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

. Just before the invasion of Sicily, Umberto had gone on an inspection tour of the Italian forces in Sicily and reported to his father that the Italians had no hope of holding Sicily.Denis Mack Smith, ''Italy and Its Monarchy'', New Haven: Yale University Press p. 303 Mussolini had assured the King that the ''Regio Esercito

The Royal Italian Army () (RE) was the land force of the Kingdom of Italy, established with the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy. During the 19th century Italy started to unify into one country, and in 1861 Manfredo Fanti signed a decree c ...

'' could hold Sicily, and the poor performance of the Italian forces defending Sicily helped to persuade the King to finally dismiss Mussolini, as Umberto informed his father that ''Il Duce'' had lied to him. On 16 July 1943, the visiting Papal Assistant Secretary of State told the American diplomats in Madrid

Madrid ( ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in Spain, most populous municipality of Spain. It has almost 3.5 million inhabitants and a Madrid metropolitan area, metropolitan area population of approximately 7 million. It i ...

that King Victor Emmanuel III and Prince Umberto were now hated by the Italian people even more than Mussolini. By this time, many Fascist ''gerarchi'' had become convinced that it was necessary to depose Mussolini to save the Fascist system, and on the night of 24–25 July 1943, at a meeting of the Fascist Grand Council, a motion introduced by the ''gerarca'' Dino Grandi to take away Mussolini's powers was approved by a vote of 19 to 8.Gerhard Weinberg, ''A World in Arms'', Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 597 The fact that the majority of the Fascist Grand Council voted for the motion showed just how disillusioned the Fascist ''gerarchi'' had become with Mussolini by the summer of 1943. The intransigent and radical group of Fascists led by the ''gerarchi'' Roberto Farinacci, who wanted to continue the war, were only a minority, while the majority of the ''gerarchi'' supported Grandi's call to jettison Mussolini as the best way of saving Fascism.

On 25 July 1943, Victor Emmanuel III finally dismissed Mussolini and appointed Marshal

Marshal is a term used in several official titles in various branches of society. As marshals became trusted members of the courts of Middle Ages, Medieval Europe, the title grew in reputation. During the last few centuries, it has been used fo ...

Pietro Badoglio

Pietro Badoglio, 1st Duke of Addis Abeba, 1st Marquess of Sabotino ( , ; 28 September 1871 – 1 November 1956), was an Italian general during both World Wars and the first viceroy of Italian East Africa. With the fall of the Fascist regim ...

, as prime minister with secret orders to negotiate an armistice with the Allies. Baron

Baron is a rank of nobility or title of honour, often Hereditary title, hereditary, in various European countries, either current or historical. The female equivalent is baroness. Typically, the title denotes an aristocrat who ranks higher than ...

Raffaele Guariglia

Raffaele Guariglia, Baron di Vituso (19 February 1889 – 25 April 1970) was an Italian diplomat. He is best known for his brief service as Minister of Foreign Affairs in the short-lived 1943 World War II-era Italian government headed by Pietro B ...

, the Italian ambassador to Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

, contacted British diplomats to begin the negotiations. Badoglio went about the negotiations halfheartedly while allowing many German forces to enter Italy. The American historian Gerhard Weinberg

Gerhard Ludwig Weinberg (born 1 January 1928) is a German-born American Diplomatic history, diplomatic and Military History, military historian noted for his studies in the history of Nazi Germany and World War II. Weinberg is the William Rand Ke ...

wrote that Badoglio as prime minister "...did almost everything as stupidly and slowly as possible", as he dragged out the secret peace talks going on in Lisbon and Tangier

Tangier ( ; , , ) is a city in northwestern Morocco, on the coasts of the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. The city is the capital city, capital of the Tanger-Tetouan-Al Hoceima region, as well as the Tangier-Assilah Prefecture of Moroc ...

, being unwilling to accept the Allied demand for unconditional surrender.Gerhard Weinberg, ''A World in Arms'', Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 598 During the secret armistice talks, Badoglio told Count Pietro d'Acquarone that he thought he might get better terms if Victor Emmanuel abdicated in favour of Umberto, complaining that the armistice terms that the King wanted were unacceptable to the Allies.Denis Mack Smith, ''Italy and Its Monarchy'', New Haven: Yale University Press p. 310 D'Acquarone told Badoglio to keep his views to himself as the King was completely unwilling to abdicate, all the more so as he believed that Umberto was unfit to be monarch.

Partition of Italy

On 17 August 1943, Sicily was taken and the last Axis forces crossed over to the Italian mainland. On 3 September 1943, the British Eighth Army landed on the Italian mainland atReggio Calabria

Reggio di Calabria (; ), commonly and officially referred to as Reggio Calabria, or simply Reggio by its inhabitants, is the List of cities in Italy, largest city in Calabria as well as the seat of the Metropolitan City of Reggio Calabria. As ...

while the U.S. 5th Army landed at Salerno

Salerno (, ; ; ) is an ancient city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Campania, southwestern Italy, and is the capital of the namesake province, being the second largest city in the region by number of inhabitants, after Naples. It is located ...

on 9 September 1943, a few hours after it was announced that Italy had signed an armistice. Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

had other plans for Italy, and in response to the Italian armistice ordered Operation Achse

Operation Achse (), originally called Operation Alaric (), was the codename for the German operation to forcibly disarm the Italian armed forces after Italy's armistice with the Allies on 3 September 1943.

Several German divisions had en ...

on 8 September 1943, as the Germans turned against their Italian allies and occupied all of the parts of Italy not taken by the Allies. In response to the German occupation of Italy, neither Victor Emmanuel nor Marshal

Marshal is a term used in several official titles in various branches of society. As marshals became trusted members of the courts of Middle Ages, Medieval Europe, the title grew in reputation. During the last few centuries, it has been used fo ...

Pietro Badoglio

Pietro Badoglio, 1st Duke of Addis Abeba, 1st Marquess of Sabotino ( , ; 28 September 1871 – 1 November 1956), was an Italian general during both World Wars and the first viceroy of Italian East Africa. With the fall of the Fascist regim ...

made any effort at organised resistance; they instead issued vague instructions to the Italian military and civil servants to do their best and fled Rome during the night of 8–9 September 1943. Not trusting his son, Victor Emmanuel had told Umberto nothing about his attempts to negotiate an armistice nor about his plans to flee Rome if the Germans should occupy it.Denis Mack Smith, ''Italy and Its Monarchy'', New Haven: Yale University Press pp. 318–319 For the first time in his life, Umberto openly criticised his father, saying the King of Italy should not be fleeing Rome and only reluctantly obeyed his father's orders to go south with him towards the Allied lines. The King and the rest of the Royal Family fled Rome via a car to Ortona

Ortona ( Abruzzese: '; ) is a coastal town and municipality of the Province of Chieti in the Italian region of Abruzzo, with some 23,000 inhabitants.

In 1943 Ortona was the site of the bloody Battle of Ortona, known as "Western Stalingrad". ...

to board a corvette, the ''Baionetta'', that took them south. A small riot occurred at the Ortona dock as about 200 senior-ranking Italian military officers, who had abandoned their commands and unexpectedly showed up, begged the King to take them with him. Almost all of them were refused permission to board, making the struggle to get to the head of the queue pointless.Denis Mack Smith, ''Italy and Its Monarchy'', New Haven: Yale University Press p. 318 With the exceptions of Marshal Enrico Caviglia, General Calvi di Bergolo and General Antonio Sorice, the Italian generals simply abandoned their posts on the night of 8–9 September to try to flee south, which greatly facilitated the German take-over, as the ''Regio Esercito'' was left without senior leadership. On the morning of 9 September 1943, Umberto arrived with Victor Emmanuel and Badoglio in Brindisi

Brindisi ( ; ) is a city in the region of Apulia in southern Italy, the capital of the province of Brindisi, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. Historically, the city has played an essential role in trade and culture due to its strategic position ...

.

In September 1943, Italy was partitioned between the south of Italy, administered by the Italian government with an Allied Control Commission (ACC) having supervisory powers, while Germany occupied northern and central Italy with a puppet Italian Social Republic

The Italian Social Republic (, ; RSI; , ), known prior to December 1943 as the National Republican State of Italy (; SNRI), but more popularly known as the Republic of Salò (, ), was a List of World War II puppet states#Germany, German puppe ...

(popularly called the Salò Republic), headed by Mussolini holding nominal power. By 16 September 1943, a line had formed across Italy with everything to the north held by the Germans and to the south by the Allies. Because of what Weinberg called the "extraordinary incompetence" of Badoglio, who, like Victor Emmanuel, had not anticipated Operation Achse until it was far too late, thousands of Italian soldiers with no leadership were taken prisoner by the Germans without resisting in the Balkans, France and Italy itself, to be taken off to work as slave labour in factories in Germany, an experience that many did not survive. How Victor Emmanuel mishandled the armistice was to become almost as controversial in Italy as his support for Fascism. Under the terms of the armistice, the ACC had the ultimate power with the Royal Italian Government in the south, being in many ways a similar position to the Italian Social Republic under the Germans. However, as the British historian James Holland noted, the crucial difference was that: "In the south, Italy was now moving closer towards democracy".Holland, James ''Italy's Year of Sorrow, 1944–1945'', New York: St. Martin's Press, 2008 p. 250 In the part of Italy under the control of the ACC, which issued orders to the Italian civil servants, freedom of the press, association and expression were restored along with other civil rights and liberties.

During 1943–45, the Italian economy collapsed with much of the infrastructure destroyed, inflation rampant, the black market becoming the dominant form of economic activity, and food shortages reducing much of the population to the brink of starvation in both northern and southern Italy. In 1943–44, the cost of living in southern Italy skyrocketed by 321%, while it was estimated that people in Naples needed 2,000 calories per day to survive while the average Neapolitan was doing well if they consumed 500 calories a day in 1943–44. Naples in 1944 was described as a city without cats or dogs which had all been eaten by the Neapolitans, while much of the female population of Naples turned to prostitution to survive. As dire as the economic situation was in southern Italy, food shortages and inflation were even worse in northern Italy as the Germans carried out a policy of ruthless economic exploitation. Since the war in which Mussolini had involved Italy in 1940 had become such an utter catastrophe for the Italian people by 1943, it had the effect of discrediting all those associated with the Fascist system, including Victor Emmanuel. In late 1943, Victor Emmanuel stated that he felt he bore no responsibility for Italy's plight, for appointing Mussolini as prime minister in 1922 and for entering the war in 1940. This further increased his unpopularity and led to demands that he abdicate at once.

In northern Italy, a guerrilla war began against the fascists, both Italian and German, with most of the guerrilla units fighting under the banner of the National Liberation Committee

The National Liberation Committee (, CLN) was a political umbrella organization and the main representative of the Italian resistance movement fighting against the occupying forces of Nazi Germany and the fascist collaborationist forces of the ...

(''Comitato di Liberazione Nazionale''-CLN), who were very strongly left-wing and republican.Denis Mack Smith, ''Italy and Its Monarchy'', New Haven: Yale University Press p. 336 Of the six parties that made up the CLN, the Communists, the Socialists and the Action Party were republican; the Christian Democrats and the Labour Party were ambiguous on the "institutional question", and only the Liberal Party was committed to preserving the monarchy, though many individual Liberals were republicans. Only a minority of the partisan bands fighting for the CLN were monarchists, and a prince of the House of Savoy led none. After the war, Umberto claimed that he wanted to join the partisans, and only his wartime duties prevented him from doing so. The Italian Royal Court relocated itself to Brindisi

Brindisi ( ; ) is a city in the region of Apulia in southern Italy, the capital of the province of Brindisi, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. Historically, the city has played an essential role in trade and culture due to its strategic position ...

in the south of Italy after fleeing Rome. In the fall of 1943, many Italian monarchists, like Benedetto Croce

Benedetto Croce, ( , ; 25 February 1866 – 20 November 1952)

was an Italian idealist philosopher, historian, and politician who wrote on numerous topics, including philosophy, history, historiography, and aesthetics. A Cultural liberalism, poli ...

and Count

Count (feminine: countess) is a historical title of nobility in certain European countries, varying in relative status, generally of middling rank in the hierarchy of nobility. Pine, L. G. ''Titles: How the King Became His Majesty''. New York: ...

Carlo Sforza

Count Carlo Sforza (24 January 1872 – 4 September 1952) was an Italian nobility, Italian nobleman, diplomat and Anti-fascism, anti-fascist politician.

Life and career

Sforza was born in Lucca, the second son of Count Giovanni Sforza (184 ...

, pressed for Victor Emmanuel III to abdicate and for Umberto to renounce his right to the succession in favour of his 6-year-old son, with a regency council to govern Italy as the best hope of saving the monarchy. Count Sforza tried to interest the British members of the ACC in this plan, calling Victor Emmanuel a "despicable weakling" and Umberto "a pathological case", saying neither was qualified to rule Italy. However, given the unwillingness of the King to abdicate, nothing came of it.

At a meeting of the leading politicians from the six revived political parties on 13 January 1944 in Bari

Bari ( ; ; ; ) is the capital city of the Metropolitan City of Bari and of the Apulia Regions of Italy, region, on the Adriatic Sea in southern Italy. It is the first most important economic centre of mainland Southern Italy. It is a port and ...

, the demand was made that the ACC should force Victor Emmanuel to abdicate to "wash away the shame of the past".Denis Mack Smith, ''Italy and Its Monarchy'', New Haven: Yale University Press p. 324 Beyond removing Victor Emmanuel, which everyone at the Congress of Bari wanted, the Italian politicians differed, with some calling for a republic to be proclaimed at once, some willing to see Umberto succeed to the throne, others wanting Umberto to renounce his claim to the throne in favour of his son, and finally those who were willing to accept Umberto as '' Luogotenente Generale del Regno'' () to govern in place of his father. Since northern and central Italy were still occupied by Germany, it was finally decided at the Bari conference that the "institutional question" should be settled only once all of Italy was liberated, so all of the Italian people could have their say.

Outing and appointment as regent

In the Salò Republic, Mussolini returned to his original republicanism and, as part of his attack on theHouse of Savoy

The House of Savoy (, ) is a royal house (formally a dynasty) of Franco-Italian origin that was established in 1003 in the historical region of Savoy, which was originally part of the Kingdom of Burgundy and now lies mostly within southeastern F ...

, Fascist newspapers in the area under the control of the Italian Social Republic outed

Outing is the act of disclosing an LGBTQ person's sexual orientation or gender identity without their consent. It is often done for political reasons, either to instrumentalize homophobia, biphobia, and/or transphobia in order to discredit politi ...

Umberto, calling him ''Stellassa'' ("Ugly Starlet" in the Piedmontese language

Piedmontese ( ; autonym: or ; ) is a language spoken by some 2,000,000 people mostly in Piedmont, a region of Northwest Italy. Although considered by most linguists a separate Romance languages, language, in Italy it is often mistakenly regar ...

).Dall'Oroto, Giovanni "Umberto II" from ''Who's Who in Contemporary Gay and Lesbian History'', London: Psychology Press, 2002 p. 534 The Fascist newspapers reported in a lurid, sensationalist, and decidedly homophobic way Umberto's various relationships with men as a way of discrediting him. It was after Umberto was outed by the Fascist press in late 1943 that the issue of his homosexuality came to widespread public notice.

As the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are calle ...

freed more and more of Italy from the Salò Republic, it became apparent that Victor Emmanuel was too tainted by his previous support of Fascism

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural social hie ...

to have any further role. A sign of how unpopular the House of Savoy had become was that on 28 March 1944, when the Italian Communist leader Palmiro Togliatti

Palmiro Michele Nicola Togliatti (; 26 March 1893 – 21 August 1964) was an Italian politician and statesman, leader of Italy's Italian Communist Party, Communist party for nearly forty years, from 1927 until his death. Born into a middle-clas ...

returned to Italy after a long exile in the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, he did not press for an immediate proclamation of a republic. Togliatti wanted the monarchy to continue as the best way of winning the Communists' support after the war.Denis Mack Smith, ''Italy and Its Monarchy'', New Haven: Yale University Press pp. 326–327 For the same reason, Count Sforza wanted a republic as soon as possible, arguing the House of Savoy was far too closely associated with Fascism to enjoy moral legitimacy, and the only hope of establishing a liberal democracy in Italy after the war was a republic. By this point, the government of Pietro Badoglio

Pietro Badoglio, 1st Duke of Addis Abeba, 1st Marquess of Sabotino ( , ; 28 September 1871 – 1 November 1956), was an Italian general during both World Wars and the first viceroy of Italian East Africa. With the fall of the Fascist regim ...

was so unpopular with the Italian people that Umberto was willing to accept the support of any party with a mass following, even the Communists. The fact that contrary to expectations, Togliatti and Badoglio got along very well, led to widespread fears amongst liberal-minded Italians that a Togliatti-Badoglio duumvirate might emerge, forming an alliance between what rapidly was becoming Italy's largest mass party and the military. The power and influence of Badoglio's government, based in Salerno

Salerno (, ; ; ) is an ancient city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Campania, southwestern Italy, and is the capital of the namesake province, being the second largest city in the region by number of inhabitants, after Naples. It is located ...

, was very limited, but the entry of the Communists, followed by representatives of the other anti-Fascist parties, into the Cabinet of that government in April 1944 marked the moment when, as the British historian David Ellwood noted, "...anti-Fascism had compromised with the traditional state and the defenders of Fascism, and the Communist Party had engineered this compromise. A quite new phase in Italy's liberation was opening". Besides the "institutional question", the principle responsibility of the Royal Italian Government was the reconstruction of the liberated areas of Italy.Gerhard Weinberg, ''A World in Arms'', Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004 p. 487 As the Allies pushed northwards, aside from the damage caused by the fighting, the retreating Germans systematically destroyed all of the infrastructure, leading to a humanitarian disaster in the liberated parts. Umberto, together with the rest of his father's government, spent time attempting to have humanitarian aid delivered.

Under intense pressure from Robert Murphy and Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton (10 February 1894 – 29 December 1986), was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. Nickn ...

of the ACC at a meeting on 10 April 1944, Victor Emmanuel transferred most of his powers to Umberto. The King bitterly told Lieutenant-General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the battlefield, who was normall ...

Sir Noel Mason-MacFarlane that Umberto was unqualified to rule, and that handing power over to him was equivalent to letting the Communists come to power. However, events had moved beyond Victor Emmanuel's ability to control. After Rome was liberated in June, Victor Emmanuel transferred his remaining constitutional powers to Umberto, naming his son Lieutenant General of the Realm. However, Victor Emmanuel retained the title and position of King

King is a royal title given to a male monarch. A king is an Absolute monarchy, absolute monarch if he holds unrestricted Government, governmental power or exercises full sovereignty over a nation. Conversely, he is a Constitutional monarchy, ...

. During his period as Regent, Umberto saw his father only three times, partly out of a bid to distance himself and partly because of tensions between father and son. Mack Smith wrote that Umberto was: "More attractive and outgoing than his father, he was even more a soldier at heart, and completely inexperienced as a politician...In personality-less astute and intelligent than his father...less obstinate, he was far more open, affable and ready to learn".

As Regent, Umberto initially made a poor impression on almost everyone as he surrounded himself with Fascist-era generals as his advisers, spoke of the military as the basis of his power, frequently threatened to sue for libel anyone who made even the slightest critical remarks about the House of Savoy, and asked the ACC to censor the press to prevent the criticism of himself or his father.Denis Mack Smith, ''Italy and Its Monarchy'', New Haven: Yale University Press p. 325 The British Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden

Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon (12 June 1897 – 14 January 1977) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1955 until his resignation in 1957.

Achi ...

, wrote after meeting Umberto, in a message to London, that he was "the poorest of poor creatures", and his only qualification for the throne was that he had more charm than his charmless father. The historian and philosopher Benedetto Croce

Benedetto Croce, ( , ; 25 February 1866 – 20 November 1952)

was an Italian idealist philosopher, historian, and politician who wrote on numerous topics, including philosophy, history, historiography, and aesthetics. A Cultural liberalism, poli ...

, a minister in Badoglio's cabinet, called Umberto "entirely insignificant" as he found the Prince of Piedmont to be shallow, vain, superficial, and of low intelligence, and alluding to his homosexuality stated his private life was "tainted by scandal".

The diplomat and politician Count

Count (feminine: countess) is a historical title of nobility in certain European countries, varying in relative status, generally of middling rank in the hierarchy of nobility. Pine, L. G. ''Titles: How the King Became His Majesty''. New York: ...

Carlo Sforza

Count Carlo Sforza (24 January 1872 – 4 September 1952) was an Italian nobility, Italian nobleman, diplomat and Anti-fascism, anti-fascist politician.

Life and career

Sforza was born in Lucca, the second son of Count Giovanni Sforza (184 ...

wrote in his diary that Umberto was utterly unqualified to be King as he called the prince "a stupid young man who knew nothing of the real Italy" and "he had been as closely associated with fascism as his father. In addition he is weak and dissipated, with a degenerate and even oriental disposition inherited from his Balkan mother". Sam Reber, an American official with the ACC, who had known Umberto before the war, met the prince in Naples in early 1944 and wrote he found him "greatly improved. The Balkan playboy period was over. But he has a weak face and, to judge by first meeting, has not, I should say, the personality to inspire confidence and devotion in others". More damaging, Victor Emmanuel let it be known that he regretted handing over his powers to his son, and made clear that he felt that Umberto was unfit to succeed him as part of a bid to take back his lost powers.

After Togliatti and the Communists entered Badoglio's cabinet, taking the oaths of loyalty to Umberto in the so-called ''Svolta di Salerno'' ("Salerno turn"), the leaders of the other anti-Fascist parties felt they had no choice but to join the cabinet as to continue to boycott it might lead Italy to be open to Communist domination. The other parties entered the cabinet on 22 April 1944 to preempt the Communists who joined the cabinet on 24 April. The Christian Democratic leader Alcide De Gasperi

Alcide Amedeo Francesco De Gasperi (; 3 April 1881 – 19 August 1954) was an Italian politician and statesman who founded the Christian Democracy party and served as prime minister of Italy in eight successive coalition governments from 1945 t ...

believed in 1944 that a popular vote would ensure a republic immediately, and sources from the Vatican suggested to him that only 25% of Italians favoured continuing the monarchy.Denis Mack Smith, ''Italy and Its Monarchy'', New Haven: Yale University Press p. 332 The Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

was in favour of Umberto, who, unlike his father, was a sincere Catholic who it was believed would keep the Communists out of power. However, De Gasperi admitted that though the monarchy was a conservative institution, "it was difficult to answer the argument that the monarchy had done little to serve the interests of the country or people during the past thirty years".

Umberto's relations with the Allies were strained by his insistence that after the war, Italy should keep all of its colonial empire

A colonial empire is a sovereign state, state engaging in colonization, possibly establishing or maintaining colony, colonies, infused with some form of coloniality and colonialism. Such states can expand contiguous as well as Territory#Overseas ...

, including Ethiopia

Ethiopia, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country located in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the north, Djibouti to the northeast, Somalia to the east, Ken ...

and the parts of Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

that Mussolini had annexed in 1941.Denis Mack Smith, ''Italy and Its Monarchy'', New Haven: Yale University Press p. 341 Both the British and Americans told Umberto that Ethiopia had its independence restored in 1941 and would not revert to Italian rule, while the Allies had promised that Yugoslavia would be restored to its pre-war frontiers after the war. Umberto later stated that he would have never signed the peace treaty of 1947 under which Italy renounced its empire. On 15 April 1944, in an interview with ''The Daily Express

The ''Daily Express'' is a national daily United Kingdom middle-market newspaper printed in tabloid format. Published in London, it is the flagship of Express Newspapers, owned by publisher Reach plc. It was first published as a broadsheet i ...

'', Umberto stated his hope that Italy would become a full Allied power, expressing his wish that the ''Regia Marina

The , ) (RM) or Royal Italian Navy was the navy of the Kingdom of Italy () from 1861 to 1946. In 1946, with the birth of the Italian Republic (''Repubblica Italiana''), the changed its name to '' Marina Militare'' ("Military Navy").

Origin ...

'' would fight in the Pacific against the Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan, also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was the Japanese nation state that existed from the Meiji Restoration on January 3, 1868, until the Constitution of Japan took effect on May 3, 1947. From Japan–Kor ...

and the ''Regio Esercito

The Royal Italian Army () (RE) was the land force of the Kingdom of Italy, established with the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy. During the 19th century Italy started to unify into one country, and in 1861 Manfredo Fanti signed a decree c ...

'' would march alongside the other Allied armies in invading Germany.Denis Mack Smith, ''Italy and Its Monarchy'', New Haven: Yale University Press p. 328 In the same interview, Umberto stated that he wanted post-war Italy to have a government "patterned on the British monarchy, and at the same time incorporating as much of America's political framework as possible". Umberto admitted that, in retrospect, his father had made grave mistakes as King and criticised Victor Emmanuel for a suffocating childhood, where he was never permitted to express his personality or hold views of his own.Denis Mack Smith, ''Italy and Its Monarchy'', New Haven: Yale University Press p. 331 In the same interview, Umberto stated that he hoped to make Italy a democracy by executing "the vastest education programme Italy has ever seen" to eliminate illiteracy in Italy once and for all.

A few days later, on 19 April 1944, Umberto in an interview with ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' complained that the ACC was too liberal in giving Italians too much freedom, as the commissioners "seemed to expect the Italian people to run before they could walk". In the same interview, Umberto demanded the ACC censor the Italian press to end the criticism of the Royal Family, and claimed he had no choice but to support Mussolini because otherwise he would have been disinherited. Finally, Umberto made the controversial statement that Mussolini "at first had the full support of the nation" in bringing Italy into the war in June 1940. Victor Emmanuel III had only signed the declarations of war because "there was no sign that the nation wanted it otherwise. No single voice was raised in protest. No demand was made for summoning parliament". The interview with ''The Times'' caused a storm of controversy in Italy, with many Italians objecting to Umberto's claim that the responsibility for Italy entering the war rested with ordinary Italians and his apparent ignorance of the difficulties of holding public protests under the Fascist regime in 1940. Sforza wrote in his diary of his belief that Victor Emmanuel, "that little monster", had put Umberto up to the interview to discredit his son.Denis Mack Smith, ''Italy and Its Monarchy'', New Haven: Yale University Press p. 329 Croce wrote:"The Prince of Piedmont for twenty-two years has never shown any sign of acting independently of his father. Now he is simply repeating his father's arguments. He chooses to do this at the very moment when, having been designated lieutenant of the kingdom, he ought to be overcoming doubt and distrust as I personally hoped he would succeed in doing. To me it seems unworthy to try to unload the blame and errors of royalty on the people. I, an old monarchist, am therefore especially grieved when I see the monarchs themselves working to discredit the monarchy".Various Italian politicians had attempted to persuade the Allies to revise the armistice of 1943 in Italy's favour because there was a difference between the Fascist regime and the Italian people. Umberto's statement that the House of Savoy bore no responsibility when he asserted that the Italian people had been of one mind with Mussolini in June 1940, was widely seen as weakening the case for revising the armistice.

Liberation and republicanism

Most of the Committee of National Liberation (CLN) leaders operating underground in the north tended to lean in a republican direction. Still, they were willing to accept Umberto temporarily out of the belief that his personality and widespread rumours about his private life would ensure that he would not last long as either Lieutenant General of the Realm or as King, should his father abdicate. After the liberation of Rome on 6 June 1944, the various Italian political parties all applied strong pressure on Umberto to dismiss Pietro Badoglio as prime minister, as the Duke had loyally served the Fascist regime until the Royal coup on 25 July 1943, which resulted in the social democratIvanoe Bonomi

Ivanoe Bonomi (; 18 October 1873 – 20 April 1951) was an Italian politician and journalist who served as Prime Minister of Italy from 1921 to 1922 and again from 1944 to 1945.

Background and earlier career

Ivanoe Bonomi was born in Mant ...

being appointed prime minister.Gerhard Weinberg, ''A World in Arms'', Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 727 On 5 June 1944, Victor Emmanuel formally gave up his powers to Umberto, finally recognising his son as Lieutenant General of the Realm. After the liberation of Rome, Umberto received a warm welcome from ordinary people when he returned to the Eternal City. Mack Smith cautioned that the friendly reception that Umberto received in Rome may have been due to him being a symbol of normalcy after the harsh German occupation as opposed to genuine affection for the prince. During the German occupation, much of the Roman population had lived on the brink of starvation, young people had been arrested on the streets to be taken off to work as slave labourers in Germany, while the Fascist ''Milizia'', together with the ''Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the German Army (1935–1945), ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmac ...

'' and SS, had committed numerous atrocities. Badoglio, by contrast, was greeted with widespread hostility when he returned to Rome, being blamed by many Italians as the man, together with the King, who was responsible for abandoning Rome to the Germans without a fight in September 1943.

Umberto had ordered Badoglio to bring members of the Committee of National Liberation (CLN) into his cabinet after the liberation of Rome to broaden his basis of support and ensure national unity by preventing the emergence of a rival government. Umberto moved into the Quirinal Palace

The Quirinal Palace ( ) is a historic building in Rome, Italy, the main official residence of the President of Italy, President of the Italian Republic, together with Villa Rosebery in Naples and the Tenuta di Castelporziano, an estate on the outs ...

, while at The Grand Hotel, the Rome branch of the CLN met with the cabinet. Speaking on behalf of the CLN in general, the Roman leadership of the CLN refused to join the cabinet as long as Badoglio headed it but indicated that Bonomi was an acceptable choice as prime minister for them. Lieutenant-General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the battlefield, who was normall ...

Sir Noel Mason-MacFarlane of the ACC visited the Quirinal Palace and convinced Umberto to accept Bonomi as prime minister because the Crown needed to bring the CLN into the government, which required sacrificing Badoglio. As Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin were willing to see Badoglio continue as prime minister, seeing him as a force for order, Umberto could have held out for him. However, as part of his efforts to distance himself from Fascism, Umberto agreed to appoint Bonomi as prime minister. Reflecting the tense "institutional question" of republic vs. monarchy, Umberto, when swearing in the Bonomi cabinet, allowed the ministers to take either their oaths to himself as the Lieutenant General of the Realm or to the Italian state; Bonomi himself chose to take his oath to Umberto while the rest of his cabinet chose to take their oaths only to the Italian state. Churchill especially disapproved of the replacement of Badoglio with Bonomi, complaining that, in his view, Umberto was being used by "a group of aged and hungry politicians trying to intrigue themselves into an undue share of power". Through the Allied occupation, the Americans were far more supportive of Italian republicanism than the British, with Churchill in particular believing the Italian monarchy was the only institution that was capable of preventing the Italian Communists from coming to power after the war.