Ukk on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Urho Kaleva Kekkonen (; 3 September 1900 – 31 August 1986), often referred to by his initials UKK, was a Finnish politician who served as the eighth and longest-serving

''Kansallisbiografia'' (English edition). On the other hand, his perceived hunger for power, his divide-and-rule attitude in domestic politics and the lack of genuine political opposition, especially during the latter part of his presidency, significantly weakened Finnish democracy during his presidency. After Kekkonen's presidency, the reform of the

Kekkoset, itäsuomalainen suku

'. Twelve generations of Urho Kekkonen's ancestors were peasants from eastern Finland. The paternal side of Kekkonen's family practised

The son of Juho Kekkonen and Emilia Pylvänäinen, Urho Kekkonen was born at ''Lepikon Torppa'' ("the

The son of Juho Kekkonen and Emilia Pylvänäinen, Urho Kekkonen was born at ''Lepikon Torppa'' ("the

During Kekkonen's term, the balance of power between the

During Kekkonen's term, the balance of power between the

In the presidential election of 1956, Kekkonen defeated the Social Democrat

In the presidential election of 1956, Kekkonen defeated the Social Democrat  The second time the Soviets helped Kekkonen was in the

The second time the Soviets helped Kekkonen was in the

In the 1960s Kekkonen was responsible for a number of foreign-policy initiatives, including the

In the 1960s Kekkonen was responsible for a number of foreign-policy initiatives, including the

On 18 January 1973, the Finnish Parliament extended Kekkonen's presidential term by four years with a Derogation law (an ad hoc law made as an exception to the constitution). By this time, Kekkonen had secured the backing of most political parties, but the major right-wing

On 18 January 1973, the Finnish Parliament extended Kekkonen's presidential term by four years with a Derogation law (an ad hoc law made as an exception to the constitution). By this time, Kekkonen had secured the backing of most political parties, but the major right-wing  The elimination of any significant opposition and competition meant he became Finland's ''de facto'' political autocrat. His power reached its zenith in 1975 when he dissolved parliament and hosted the

The elimination of any significant opposition and competition meant he became Finland's ''de facto'' political autocrat. His power reached its zenith in 1975 when he dissolved parliament and hosted the

From December 1980 onwards, Kekkonen suffered from an undisclosed disease that appeared to affect his brain functions, sometimes leading to delusional thoughts. He had begun to suffer occasional brief memory lapses as early as the autumn of 1972; they became more frequent during the late 1970s. Around the same time, Kekkonen's eyesight deteriorated so much that for his last few years in office, all of his official papers had to be typed in block letters. Kekkonen had also suffered from a failing sense of balance since the mid-1970s and from enlargement of his

From December 1980 onwards, Kekkonen suffered from an undisclosed disease that appeared to affect his brain functions, sometimes leading to delusional thoughts. He had begun to suffer occasional brief memory lapses as early as the autumn of 1972; they became more frequent during the late 1970s. Around the same time, Kekkonen's eyesight deteriorated so much that for his last few years in office, all of his official papers had to be typed in block letters. Kekkonen had also suffered from a failing sense of balance since the mid-1970s and from enlargement of his

* The

* The  * A pub in Etu-Töölö,

* A pub in Etu-Töölö,

JPG image

Badraie

Urho Kekkonen Museum, Tamminiemi, Helsinki

Urho Kekkonen National Park

Urho Kekkonen

in The Presidents of Finland {{DEFAULTSORT:Kekkonen, Urho 1900 births 1986 deaths People from Pielavesi Politicians from Kuopio Province (Grand Duchy of Finland) Finnish Lutherans Centre Party (Finland) politicians Presidents of Finland Prime ministers of Finland Ministers for foreign affairs of Finland Ministers of justice of Finland Ministers of the interior of Finland Speakers of the Parliament of Finland Members of the Parliament of Finland (1936–1939) Members of the Parliament of Finland (1939–1945) Members of the Parliament of Finland (1945–1948) Members of the Parliament of Finland (1948–1951) Members of the Parliament of Finland (1951–1954) Members of the Parliament of Finland (1954–1958) 20th-century Finnish lawyers Honorary Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath University of Helsinki alumni People of the Finnish Civil War (White side) Finnish people of World War II People of the Cold War Grand Crosses of the Order of the Cross of Liberty Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Falcon Recipients of the Lenin Peace Prize Burials at Hietaniemi Cemetery Recipients of orders, decorations, and medals of Senegal

president of Finland

The president of the Republic of Finland (; ) is the head of state of Finland. The incumbent president is Alexander Stubb, since 1 March 2024. He was elected president for the first time in 2024 Finnish presidential election, 2024.

The presi ...

from 1956 to 1982. He also served as prime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

(1950–1953, 1954–1956), and held various other cabinet positions. He was the third and most recent president from the Agrarian League/Centre Party. Head of state for nearly 26 years, he dominated Finnish politics

The politics of Finland take place within the framework of a Parliamentary system, parliamentary representative democracy. Finland is a republic whose head of state is President of Finland, President Alexander Stubb, who leads the nation's for ...

for 31 years overall. Holding a large amount of power, he won his later elections with little opposition and has often been classified as an autocrat

Autocracy is a form of government in which absolute power is held by the head of state and government, known as an autocrat. It includes some forms of monarchy and all forms of dictatorship, while it is contrasted with democracy and feudalism. ...

.

As president, Kekkonen continued the "active neutrality" policy of his predecessor President Juho Kusti Paasikivi

Juho Kusti Paasikivi (, 27 November 1870 – 14 December 1956) was a Finnish politician who served as the seventh president of Finland from 1946 to 1956. Representing the Finnish Party until its dissolution in 1918 and then the National Coaliti ...

that came to be known as the Paasikivi–Kekkonen doctrine

The Paasikivi–Kekkonen doctrine was a foreign policy doctrine established by Finnish President Juho Kusti Paasikivi and continued by his successor Urho Kekkonen, aimed at Finland's survival as an independent sovereign, democratic country in ...

, under which Finland was to retain its independence while maintaining good relations and extensive trade with members of both NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

and the Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP), formally the Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation and Mutual Assistance (TFCMA), was a Collective security#Collective defense, collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Polish People's Republic, Poland, between the Sovi ...

. Critical commentators referred to this policy of appeasement pejoratively as Finlandization

Finlandization () is the process by which one powerful country makes a smaller neighboring country refrain from opposing the former's foreign policy rules, while allowing it to keep its nominal independence and its own political system. The term ...

. He hosted the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe

The Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) was a key element of the détente process during the Cold War. Although it did not have the force of a treaty, it recognized the boundaries of postwar Europe and established a mechanism ...

in Helsinki in 1975 and was considered a potential candidate for the Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize (Swedish language, Swedish and ) is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the Will and testament, will of Sweden, Swedish industrialist, inventor, and armaments manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Nobe ...

that year. He is credited by Finnish historians for his foreign and trade policies, which allowed Finland's market economy

A market economy is an economic system in which the decisions regarding investment, production, and distribution to the consumers are guided by the price signals created by the forces of supply and demand. The major characteristic of a mark ...

to keep pace with Western Europe even with the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

as a neighbor, and for Finland to gradually take part in the European integration

European integration is the process of political, legal, social, regional and economic integration of states wholly or partially in Europe, or nearby. European integration has primarily but not exclusively come about through the European Union ...

process.Kekkonen, Urho''Kansallisbiografia'' (English edition). On the other hand, his perceived hunger for power, his divide-and-rule attitude in domestic politics and the lack of genuine political opposition, especially during the latter part of his presidency, significantly weakened Finnish democracy during his presidency. After Kekkonen's presidency, the reform of the

Constitution of Finland

The Constitution of Finland ( or ) is the supreme source of national law of Finland. It defines the basis, structures and organisation of government, the relationship between the different constitutional organs, and lays out the fundamental right ...

was initiated by his successors to increase the power of the Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

and the prime minister at the expense of the president.

Kekkonen was a member of the Parliament of Finland

The Parliament of Finland ( ; ) is the Unicameralism, unicameral and Parliamentary sovereignty, supreme legislature of Finland, founded on 9 May 1906. In accordance with the Constitution of Finland, sovereignty belongs to the people, and that ...

from 1936 until his rise to the presidency. Either prior, during or between his premierships, he served as minister of justice

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice, is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a ...

(1936–37, 1944–46, 1951), minister of the interior

An interior minister (sometimes called a minister of internal affairs or minister of home affairs) is a cabinet official position that is responsible for internal affairs, such as public security, civil registration and identification, emergency ...

(1937–39, 1950–51), speaker of the Finnish Parliament (1948–50) and minister of foreign affairs

In many countries, the ministry of foreign affairs (abbreviated as MFA or MOFA) is the highest government department exclusively or primarily responsible for the state's foreign policy and foreign relations, relations, diplomacy, bilateralism, ...

(1952–53, 1954). In addition to his extensive political career, he was a lawyer by education, a policeman and athlete in his youth, a veteran of the Finnish Civil War

The Finnish Civil War was a civil war in Finland in 1918 fought for the leadership and control of the country between Whites (Finland), White Finland and the Finnish Socialist Workers' Republic (Red Finland) during the country's transition fr ...

, and an enthusiastic writer. During World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, his anonymous reports on the war and foreign politics received a large audience in the ''Suomen Kuvalehti

''Suomen Kuvalehti'' ( or 'the Finnish picture magazine') is a weekly Finnish language family and news magazine published in Helsinki, Finland.

History and profile

''Suomen Kuvalehti'' was founded in 1873 and published until the year 1880. The m ...

'' magazine. Even during his presidency, he wrote humorous, informal columns (''causerie

Causerie (from French, "talk, chat") is a literary style of short informal essays mostly unknown in the English-speaking world. A causerie is generally short, light and humorous and is often published as a newspaper column (although it is not defi ...

'') for the same magazine, edited by his long-time friend Ilmari Turja

Ilmari Turja (28 October 1901 – 6 January 1998) was a Finnish writer, best known as a journalist and playwright, with a career spanning nearly eight decades from the 1920s to the 1990s.

Early life and education

Kaarlo Ilmari Turja was born ...

, under several pseudonyms.

Biography

Family history

The Kekkonens are an old Savonian family. The ancestors of Urho Kekkonen most likely settled in the Savonia region before the 16th century. Although it is not known where the Kekkonens came to Savonia from, there has been speculation that they are from Karelia as people with the name were known to have lived in certain settlements of theKarelian Isthmus

The Karelian Isthmus (; ; ) is the approximately stretch of land situated between the Gulf of Finland and Lake Ladoga in northwestern Russia, to the north of the River Neva. Its northwestern boundary is a line from the Bay of Vyborg to the we ...

for centuries. Kekkonen himself thought it possible that the family might instead originate from Western Finland, for example from Tavastia, where there have been place names connected to their surname from as early as the 15th century. His seventh-great-grandfather Tuomas Kekkonen (born ca. 1630) is first mentioned in documents in Pieksämäki

Pieksämäki () is a town and municipality of Finland. It is located in the Southern Savonia region, about north of Mikkeli, east of Jyväskylä and south of Kuopio. The town has a population of () and covers an area of of which is water ...

in 1673. He was probably from either Kangasniemi

Kangasniemi is a municipality in the Southern Savonia regions of Finland, region, Finland. The municipality has a population of () and covers an area of of which is water. The population density is .

Kangasniemi is located on the Highways in ...

or Joroinen

Joroinen is a municipality in the North Savo region of Finland. It is located in the province of Eastern Finland Province, Eastern Finland and is part of the Northern Savonia sub-region. The municipality has a population of approximately 4,626 peop ...

.Kekkonen, Urho: Kekkoset, itäsuomalainen suku

'. Twelve generations of Urho Kekkonen's ancestors were peasants from eastern Finland. The paternal side of Kekkonen's family practised

slash-and-burn agriculture

Slash-and-burn agriculture is a form of shifting cultivation that involves the cutting and burning of plants in a forest or woodland to create a field called a swidden. The method begins by cutting down the trees and woody plants in an area. The ...

and the maternal side stayed on their own site. Kekkonen's paternal grandfather Eenokki was part of a landless group grown in the 19th century and lived on temporary work and working as a farmworker

A farmworker, farmhand or agricultural worker is someone employed for labor in agriculture. In labor law, the term "farmworker" is sometimes used more narrowly, applying only to a hired worker involved in agricultural production, including har ...

.Uino, Ari (ed.): ''Nuori Urho: Urho Kekkosen Kajaanin-vuodet 1911–1921''. Otava 1999. , p. 7.

After serving in several houses Eenokki Kekkonen married Anna-Liisa Koskinen. They had four sons, named Taavetti, Johannes, Alpertti and Juho. Juho Kekkonen, the youngest son of the family, who had gone travelling from the family's home in Korvenmökki in the village of Koivujärvi, was the father of Urho Kekkonen. Aatu Pylvänäinen, Urho Kekkonen's maternal grandfather, who worked as a farmer at the Tarkkala farm in Kangasniemi

Kangasniemi is a municipality in the Southern Savonia regions of Finland, region, Finland. The municipality has a population of () and covers an area of of which is water. The population density is .

Kangasniemi is located on the Highways in ...

, married Amanda Manninen in the summer of 1878 when she was only 16 years old. Their children, three daughters and three sons, were Emilia, Elsa, Siilas, Tyyne, Eetu, and Samuel.

As the son of a poor family, Juho Kekkonen had to go to work in the forest and ended up at a log working ground in Kangasniemi in 1898. Emilia Pylvänäinen herded cattle there, on the shores of the Haahkala lands, where Juho Kekkonen worked with other loggers. The two youngsters got to know each other and they married in 1899. The couple moved to Otava, where Juho Kekkonen got a job at the Koivusaha sawmill of Halla Oy. He was later appointed the head of forestry work and caretaker of the logging business.

The couple moved to Pielavesi

Pielavesi is a municipality of Finland. It is part of the Northern Savonia region. The municipality has a population of () and covers an area of of which is water. The population density is . The municipality is unilingually Finnish.

Geograp ...

along with the working grounds, where Juho Kekkonen bought a smoke hut which he later repaired and expanded into a proper house. He built a chimney in the house shortly before the birth of his first son Urho. Because of the beautiful alder

Alders are trees of the genus ''Alnus'' in the birch family Betulaceae. The genus includes about 35 species of monoecious trees and shrubs, a few reaching a large size, distributed throughout the north temperate zone with a few species ex ...

s growing behind the house, the house became known as ''Lepikon torppa'' (" croft of alders"). There was a smoke sauna

The Finnish sauna (, ) is a substantial part of Finnish and Estonian culture.

It was inscribed on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists at the 17 December 2020 meeting of the UNESCO Intergovernmental Committee for the Safeguarding of ...

in the yard, where Urho Kekkonen was born on 3 September 1900. The family lived in Lepikon torppa for six years and Urho Kekkonen's sister Siiri was born in 1904. The family moved along with Juho Kekkonen's forestry work to Kuopio

Kuopio ( , ) is a city in Finland and the regional capital of North Savo. It is located in the Finnish Lakeland. The population of Kuopio is approximately , while the Kuopio sub-region, sub-region has a population of approximately . It is the mos ...

in 1906 and to Lapinlahti

Lapinlahti (; , also ) is a municipalities of Finland, municipality of Finland. It is part of the Northern Savonia regions of Finland, region, located north of the city of Kuopio. The municipality has a population of () and covers an area of ...

in 1908. The family had to live modestly but did not suffer from poverty. The youngest child of the family, Jussi Jussi () is a male given name. In Finnish originally it is short for Juhani or Juho, Finnish for Johannes/John, but is also recognized as a name in its own right for official purposes. It can also be short for Justus, or a Finnish form of Justin.

...

, was born in 1910.

Early life

The son of Juho Kekkonen and Emilia Pylvänäinen, Urho Kekkonen was born at ''Lepikon Torppa'' ("the

The son of Juho Kekkonen and Emilia Pylvänäinen, Urho Kekkonen was born at ''Lepikon Torppa'' ("the Lepikko torp

The Lepikko torp ( Finnish: ''Lepikon torppa'') is a mid-19th-century torp or croft house located in Pielavesi, central Finland, notable as the birthplace of the 8th President of Finland, Urho Kekkonen (1900–1986).

The building is construct ...

"), a small cabin located in Pielavesi

Pielavesi is a municipality of Finland. It is part of the Northern Savonia region. The municipality has a population of () and covers an area of of which is water. The population density is . The municipality is unilingually Finnish.

Geograp ...

, in the Savo

Savo may refer to:

Languages

* Savo dialect, forms of the Finnish language spoken in Savo, Finland

* Savo language, an endangered language spoken on Savo

People

* Savo (given name), a masculine given name from southern Europe (includes a list of ...

region of Finland, and spent his childhood in Kainuu

Kainuu (), also historically known as Cajania (), is one of the 19 regions of Finland (''maakunta'' / ''landskap''). Kainuu borders the regions of North Ostrobothnia, North Savo and North Karelia. In the east, it also borders Russia (Republic o ...

. His family were farmers (though not poor tenant farmer

A tenant farmer is a farmer or farmworker who resides and works on land owned by a landlord, while tenant farming is an agricultural production system in which landowners contribute their land and often a measure of operating capital and ma ...

s, as some of his supporters later claimed). His father was originally a farm-hand and forestry worker who rose to become a forestry manager and stock agent at Halla Ltd. Claims made that Kekkonen's family had lived in a rudimentary farmhouse with no chimney were later proved to be false—a photograph of Kekkonen's childhood home had been retouched to remove the chimney. His school years did not go smoothly. During the Finnish Civil War

The Finnish Civil War was a civil war in Finland in 1918 fought for the leadership and control of the country between Whites (Finland), White Finland and the Finnish Socialist Workers' Republic (Red Finland) during the country's transition fr ...

, Kekkonen fought for the White Guard (Kajaani

Kajaani (; ), is a town in Finland and the regional capital of Kainuu. Kajaani is located southeast of Oulujärvi, Lake Oulu, which drains into the Gulf of Bothnia through the Oulujoki, Oulu River. The population of Kajaani is approximately , w ...

chapter), fighting in the battles of Kuopio, Varkaus

Varkaus, before 1929 known as Warkaus, is a Middle- Savonian industrial town and municipality of Finland. It is located in the province of Eastern Finland and is part of the Northern Savonia region, between the city of Kuopio and the town of ...

, Mouhu, and Viipuri, and taking part in mop-up operations, including leading a firing squad in Hamina

Hamina (; , , Sweden ) is a List of cities in Finland, town and a Municipalities of Finland, municipality of Finland. It is located approximately east of the country's capital Helsinki, in the Kymenlaakso Regions of Finland, region, and formerly ...

. He later admitted to having killed a man in battle, but wrote in his memoirs that he was randomly selected by his company commander to follow a squad escorting ten prisoners, where the squad turned out to be a firing squad, and then to give the actual order to aim and fire. He had to complete further military service after the war, which he did in a car battalion from 1919 to 1920, finishing as a sergeant

Sergeant (Sgt) is a Military rank, rank in use by the armed forces of many countries. It is also a police rank in some police services. The alternative spelling, ''serjeant'', is used in The Rifles and in other units that draw their heritage f ...

.

In independent Finland, Kekkonen first worked as a journalist in Kajaani

Kajaani (; ), is a town in Finland and the regional capital of Kainuu. Kajaani is located southeast of Oulujärvi, Lake Oulu, which drains into the Gulf of Bothnia through the Oulujoki, Oulu River. The population of Kajaani is approximately , w ...

then moved to Helsinki in 1921 to study law. While studying he worked for the security police EK between 1921 and 1927, where he became acquainted with anti-communist policing. During this time he also met his future wife, Sylvi Salome Uino (12 March 1900 – 2 December 1974), a typist at the police station. They had two sons, Matti (1928–2013) and Taneli (1928–1985). Matti Kekkonen served as a Centre Party member of Parliament from 1958 to 1969, and Taneli Kekkonen worked as an ambassador in Belgrade

Belgrade is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city of Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers and at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin, Pannonian Plain and the Balkan Peninsula. T ...

, Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

, Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

, Malta

Malta, officially the Republic of Malta, is an island country in Southern Europe located in the Mediterranean Sea, between Sicily and North Africa. It consists of an archipelago south of Italy, east of Tunisia, and north of Libya. The two ...

, Warsaw

Warsaw, officially the Capital City of Warsaw, is the capital and List of cities and towns in Poland, largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the Vistula, River Vistula in east-central Poland. Its population is officially estimated at ...

and Tel Aviv

Tel Aviv-Yafo ( or , ; ), sometimes rendered as Tel Aviv-Jaffa, and usually referred to as just Tel Aviv, is the most populous city in the Gush Dan metropolitan area of Israel. Located on the Israeli Mediterranean coastline and with a popula ...

.

Kekkonen had a reputation as a heavy-handed, violent interrogator during his years in the security police. Conversely, he described himself as taking the role of a humane "good cop

''Good Cop'' is a British police procedural television series, written and created by Stephen Butchard, that first broadcast on BBC One on 30 August 2012. The plot centres on an ordinary police constable, John Paul Rocksavage ( Warren Brown) ...

" to balance out his older and more abusive colleagues. Some of the communists he interrogated confirmed the latter account, while others accused him of having been particularly violent. Later, as a minister in the 1950s, he is said to have visited and made peace with a communist he had "beaten up" in an interrogation in the 1920s. Explaining the contradiction of these statements, author Timo J. Tuikka says Kekkonen's interrogation methods evolved over time: "He learned that the fist is not always the most efficient tool, but that booze, sauna

A sauna (, ) is a room or building designed as a place to experience dry or wet heat sessions or an establishment with one or more of these facilities. The steam and high heat make the bathers perspire. A thermometer in a sauna is used to meas ...

and chatting are much better means of obtaining information." These revelatory experiences would significantly influence his career and approach to politics later on. Kekkonen eventually had to resign from the EK after criticising his superiors.

In 1927 Kekkonen became a lawyer and worked for the Association of Rural Municipalities until 1932. Kekkonen took a Doctor of Laws

A Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) is a doctoral degree in legal studies. The abbreviation LL.D. stands for ''Legum Doctor'', with the double “L” in the abbreviation referring to the early practice in the University of Cambridge to teach both canon law ...

degree in 1936 at the University of Helsinki

The University of Helsinki (, ; UH) is a public university in Helsinki, Finland. The university was founded in Turku in 1640 as the Royal Academy of Åbo under the Swedish Empire, and moved to Helsinki in 1828 under the sponsorship of Alexander ...

where he was active in the Pohjois-Pohjalainen Osakunta, a student nation

Student nations or simply nations ( meaning "being born") are regional corporations of students at a university. Once widespread across Europe in medieval times, they are now largely restricted to the oldest universities of Sweden and Finland, in p ...

for students from northern Ostrobothnia

North Ostrobothnia (; ) is a region of Finland. It borders the Finnish regions of Lapland, Kainuu, North Savo, Central Finland and Central Ostrobothnia, as well as the Russian Republic of Karelia. The easternmost corner of the region between ...

, and editor-in-chief of the student newspaper ''Ylioppilaslehti

''Ylioppilaslehti'' (Finnish language, Finnish: lit. "Student newspaper") is a Finland, Finnish student magazine founded in 1913. It is the largest student paper or magazine in Finland with a circulation of 35,000 copies. In addition to affairs r ...

'' in the period 1927–1928. He was also an athlete whose greatest achievement was to become the Finnish high jump champion in 1924 with a jump of . He was best at the standing jump.

Early political career

Anationalist

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation,Anthony D. Smith, Smith, A ...

at heart, Kekkonen's ideological roots lay in the student politics of newly independent Finland and in the radicalism of the right-wing. He joined the Academic Karelia Society

The Academic Karelia Society (''Akateeminen Karjala-Seura'', AKS) was a Finnish nationalist and Finno-Ugric activist organization aiming at the growth and improvement of newly independent Finland, founded by academics and students of the Univers ...

(''Akateeminen Karjala-Seura''), an organisation favouring Finland's annexation of East Karelia

East Karelia (, ), also rendered as Eastern Karelia or Russian Karelia, is a name for the part of Karelia that is beyond the eastern border of Finland and since the Treaty of Stolbovo in 1617 has remained Eastern Orthodox and a part of Russia. I ...

, but resigned from it in 1932 along with over 100 other moderate members because of the organisation's support for the 1932 far-right Mäntsälä rebellion

Mäntsälä () is a municipalities of Finland, municipality in the provinces of Finland, province of Southern Finland, and is part of the Uusimaa regions of Finland, region. It has a population of

() and covers an area of of

which

is water. ...

. According to Johannes Virolainen

Johannes Virolainen (; 31 January 1914 – 11 December 2000) was a Finnish politician and who served as 30th Prime Minister of Finland, helped inhabitants of Karelia, and opposed the use of alcohol.

Virolainen was born near Viipuri. After the C ...

, a longtime Agrarian and Centrist politician, some Finnish right-wingers hated and mocked Kekkonen for the decision and cast him as a power-hungry opportunist. Kekkonen chaired Suomalaisuuden Liitto

The Association of Finnish Culture and Identity (), also known as the Finnish Alliance, is a Finnish cultural organization. The official name of the association is in German and in French .

History

The Finnish Alliance was founded by writer J ...

, another nationalist organisation, from 1930 to 1932. He also published articles in its magazine, ''Suomalainen Suomi'' (), which was later renamed as '' Kanava''.

Kekkonen spent long periods of time in late- Weimar-era Germany between 1931 and 1933 while working on his dissertation and there witnessed the rise of Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

. This alerted him to far-right radicalism and apparently led him to publish ''Demokratian itsepuolustus'' (Self-Defense of Democracy), a political pamphlet warning about the danger, in 1934. In 1933 he joined the Agrarian League (later renamed the Centre Party), became a civil servant at the Ministry of Agriculture and made his first unsuccessful attempt at getting elected to the Finnish Parliament

The Parliament of Finland ( ; ) is the unicameral and supreme legislature of Finland, founded on 9 May 1906. In accordance with the Constitution of Finland, sovereignty belongs to the people, and that power is vested in the Parliament. The P ...

.

Kekkonen successfully stood for parliament a second time in 1936 whereupon he became Justice Minister

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice, is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a ...

, serving from 1936 to 1937. During his term, he enacted the "Tricks of Kekkonen" (''Kekkosen konstit''), an attempt to ban the right-wing, radical Patriotic People's Movement

Patriotic People's Movement (, IKL, ) was a Finnish nationalist and anti-communist political party. IKL was the successor of the previously banned Lapua Movement. It existed from 1932 to 1944 and had an ideology similar to its predecessor, exce ...

(''Isänmaallinen Kansanliike'', IKL). In the end, this effort was found illegal and halted by the Supreme Court

In most legal jurisdictions, a supreme court, also known as a court of last resort, apex court, high (or final) court of appeal, and court of final appeal, is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

. Kekkonen was also Minister of the Interior from 1937 to 1939.

He was not a member of the cabinets during the Winter War

The Winter War was a war between the Soviet Union and Finland. It began with a Soviet invasion of Finland on 30 November 1939, three months after the outbreak of World War II, and ended three and a half months later with the Moscow Peac ...

or the Continuation War

The Continuation War, also known as the Second Soviet–Finnish War, was a conflict fought by Finland and Nazi Germany against the Soviet Union during World War II. It began with a Finnish declaration of war on 25 June 1941 and ended on 19 ...

. In March 1940, in a meeting of the Committee on Foreign Affairs of the Finnish Parliament, he voted against the Moscow peace treaty

The Moscow Peace Treaty was signed by Finland and the Soviet Union on 12 March 1940, and the ratifications were exchanged on 21 March. It marked the end of the 105-day Winter War, upon which Finland ceded border areas to the Soviet Union. The ...

. During the Continuation War

The Continuation War, also known as the Second Soviet–Finnish War, was a conflict fought by Finland and Nazi Germany against the Soviet Union during World War II. It began with a Finnish declaration of war on 25 June 1941 and ended on 19 ...

, Kekkonen served as director of the Karelian Evacuees' Welfare Centre from 1940 to 1943 and as the Ministry of Finance's commissioner for coordination from 1943 to 1945, tasked with rationalising public administration. By that time, he had become one of the leading politicians within the so-called Peace opposition

Peace opposition (, ) was a Finnish cross-party movement pushing for Finland to step out of the Continuation War (1941 to 1944). From 1943 to 1944, the "Peace opposition" united bourgeois politicians such as Paasikivi, Kekkonen and Sakari Tuomioja ...

which advocated withdrawing from the war, having concluded that Germany, and consequently Finland, would lose. In 1944, he again became Minister of Justice

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice, is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a ...

, serving until 1946, and had to deal with the war-responsibility trials. Kekkonen was a Deputy Speaker of the Parliament 1946–1947, and was Speaker

Speaker most commonly refers to:

* Speaker, a person who produces speech

* Loudspeaker, a device that produces sound

** Computer speakers

Speaker, Speakers, or The Speaker may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* "Speaker" (song), by David ...

from 1948 to 1950.

In the 1950 Presidential election, Kekkonen was the candidate of the Finnish Agrarian League. He conducted a vigorous campaign against incumbent President Juho Kusti Paasikivi

Juho Kusti Paasikivi (, 27 November 1870 – 14 December 1956) was a Finnish politician who served as the seventh president of Finland from 1946 to 1956. Representing the Finnish Party until its dissolution in 1918 and then the National Coaliti ...

to finish third in the first and only ballot, receiving 62 votes in the electoral college

An electoral college is a body whose task is to elect a candidate to a particular office. It is mostly used in the political context for a constitutional body that appoints the head of state or government, and sometimes the upper parliament ...

, while Paasikivi was reelected with 171. After the election, Paasikivi appointed Kekkonen Prime Minister where in all his five cabinets

A cabinet in governing is a group of people with the constitutional or legal task to rule a country or state, or advise a head of state, usually from the executive branch. Their members are known as ministers and secretaries and they are ...

, he emphasised the need to maintain friendly relations with the Soviet Union. Known for his authoritarian personality, he was ousted in 1953 but returned as Prime Minister from 1954 to 1956. Kekkonen also served as Minister of Foreign Affairs

In many countries, the ministry of foreign affairs (abbreviated as MFA or MOFA) is the highest government department exclusively or primarily responsible for the state's foreign policy and foreign relations, relations, diplomacy, bilateralism, ...

for periods in 1952–1953 and 1954, concurrent with his prime ministership.

President of Finland

Overview

During Kekkonen's term, the balance of power between the

During Kekkonen's term, the balance of power between the Finnish Government

The Finnish Government (; ; ) is the executive branch and cabinet of Finland, which directs the politics of Finland and is the main source of legislation proposed to the Parliament. The Government has collective ministerial responsibility an ...

and the President tilted heavily towards the President. In principle and formally, parliamentarism was followed with governments nominated by a parliamentary majority. However, Kekkonen-era cabinets were often in bitter internal disagreement and alliances formed broke down easily. New cabinets often tried to reverse their predecessors' policies. Kekkonen used his power extensively to nominate ministers and to compel the legislature's acceptance of new cabinets. Publicly and with impunity, he also used the old boy network

An old boy network (also known as old boys' network, old boys' club) is an informal system in which wealthy men with similar social or educational backgrounds help each other in business or personal matters. The term originally referred to soci ...

to bypass the government and communicate directly with high officials. Only when Kekkonen's term ended did governments remain stable throughout the entire period between elections.

Nevertheless, during Kekkonen's presidency, a few parties were represented in most governments — mainly the Centrists, Social Democrats, and Swedish People's Party — while the People's Democrats and Communists were often in government from 1966 onwards.

Throughout his time as president, Kekkonen did his best to keep political adversaries in check. The Centre Party's rival National Coalition Party was kept in opposition for 20 years despite good election performances. The Rural Party (which had broken away from the Centre Party) was treated similarly. On a few occasions, parliament was dissolved for no other reason than that its political composition did not please Kekkonen. Despite his career in the Centre Party, his relation to the party was often difficult. There was a so-called ''K-linja'' ("K policy", named after Urho Kekkonen, Ahti Karjalainen

Ahti Kalle Samuli Karjalainen (10 February 1923 – 7 September 1990) was a Finland, Finnish economist and politician. He was a member of the Agrarian League (later known as Keskusta, Centre Party) and served two terms as Prime Minister of Finlan ...

and Arvo Korsimo), which promoted friendly relations and bilateral trade

Bilateral trade or clearing trade is trade exclusively between two states, particularly, barter trade based on bilateral deals between governments, and without using hard currency for payment. Bilateral trade agreements often aim to keep trade d ...

with the Soviet Union. Kekkonen consolidated his power within the party by placing supporters of the ''K-linja'' in leading roles. Various Centre Party members to whose prominence Kekkonen objected often found themselves sidelined, as Kekkonen negotiated directly with the lower level. Chairman of the Centre Party, Johannes Virolainen

Johannes Virolainen (; 31 January 1914 – 11 December 2000) was a Finnish politician and who served as 30th Prime Minister of Finland, helped inhabitants of Karelia, and opposed the use of alcohol.

Virolainen was born near Viipuri. After the C ...

, was threatened by Kekkonen with the dissolution of parliament when Kekkonen wanted to nominate SDP's Sorsa instead of Virolainen as Prime Minister. Kekkonen's so-called "Mill Letters" were a continuous stream of directives to high officials, politicians, and journalists. Yet Kekkonen by no means always used coercive measures. Some prominent politicians, most notably Tuure Junnila

Tuure Jaakko Kalervo Junnila (24 July 1910, in Kiikka – 21 June 1999) was a Finnish economist and politician. He served as Minister of Finance from 17 November 1953 to 4 May 1954. He was a member of the Parliament of Finland from 1951 to 1962, ...

( NCP) and Veikko Vennamo

Veikko Emil Aleksander Vennamo (originally ''Fennander'') (11 June 1913 – 12 June 1997) was a Finland, Finnish politician. In 1959, he founded the Finnish Rural Party (''Suomen Maaseudun Puolue''), which was succeeded by the True Finns in 1995. ...

( Rural Party), were able to brand themselves as "anti-Kekkonen" without automatically suffering his displeasure as a consequence.

First term (1956–62)

In the presidential election of 1956, Kekkonen defeated the Social Democrat

In the presidential election of 1956, Kekkonen defeated the Social Democrat Karl-August Fagerholm

Karl-August Fagerholm (31 December 1901, in Siuntio – 22 May 1984, in Helsinki) was a Finnish politician. Fagerholm served as Speaker of Parliament and three times Prime Minister of Finland (1948–50, 1956–57, and 1958–59). Fa ...

151–149 in the electoral college vote. The campaign was notably vicious, with many personal attacks against several candidates, especially Kekkonen. The tabloid gossip newspaper ''Sensaatio-Uutiset'' ("Sensational News") accused Kekkonen of fistfighting, excessive drinking and extramarital affairs. The drinking and womanizing charges were partly true. At times, during evening parties with his friends, Kekkonen got drunk, and he had at least two longtime mistresses.Seppo Zetterberg et al. (eds.) (2003) ''The Small Giant of the Finnish History''. Suomen historian pikkujättiläinen, Helsinki, Werner Söderström Publishing Ltd.

As president, Kekkonen continued the neutrality policy of President Paasikivi, which came to be known as the Paasikivi–Kekkonen line. From the beginning, he ruled with the assumption that he alone was acceptable to the Soviet Union as Finnish President. Evidence from defectors like Oleg Gordievsky

Oleg Antonovich Gordievsky (; 10 October 1938 – 4 March 2025) was a colonel of the KGB who became KGB resident-designate (''rezident'') and bureau chief in London.

Gordievsky was a double agent, providing information to the British Secret ...

and files from the Soviet archives show that keeping Kekkonen in power was indeed the main objective of the Soviet Union in its relations with Finland.

In August 1958, Karl-August Fagerholm's third cabinet

Karl-August Fagerholm's third cabinet, also known as the Night Frost Cabinet or the Night Frost Government, was the 44th government of Republic of Finland, in office from August 29, 1958 to January 13, 1959. It was a majority government. The cabine ...

, a coalition government led by the Social Democratic Party

The name Social Democratic Party or Social Democrats has been used by many political parties in various countries around the world. Such parties are most commonly aligned to social democracy as their political ideology.

Active parties

Form ...

(SDP) and including Kekkonen's party Agrarian League, was formed. The Communist front SKDL was left out. This irritated the Soviet Union because of the inclusion of ministers from SDP's anti-Communist wing, namely Väinö Leskinen

Väinö Olavi Leskinen (8 March 1917, in Helsinki – 8 March 1972, in Helsinki) was a Finnish politician, minister and a member of the parliament from Social Democratic Party of Finland. He is perceived as one of the major Finnish social democr ...

and Olavi Lindblom

Olavi Lindblom (11 December 1911 – 13 August 1990) was a Finnish trade union leader and politician, born in Helsinki. He was a member of the Parliament of Finland from 1954 to 1966, representing the Social Democratic Party of Finland (SDP). ...

. They were seen by the Soviet Union as puppets of the anti-Communist SDP chair Väinö Tanner

Väinö Alfred Tanner (; 12 March 1881 – 19 April 1966; surname until 1895 ''Thomasson'') was a leading figure in the Social Democratic Party of Finland, and a pioneer and leader of the cooperative movement in Finland. He was Prime Minist ...

, who had been convicted in the war-responsibility trials.Varjus, Seppo. ''Näin valta otetaan ja pidetään.'' In YYA-Suomi – suomettumisen vuodet, Iltasanomat, Sanoma Media Finland 2019, pp. 14–17. Kekkonen had warned against this but was ignored by SDP. The Night Frost Crisis, as coined by Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

, led to Soviet pressure against Finland in economic matters. Kekkonen sided with the Soviet Union, working behind the scenes against the cabinet; Fagerholm's cabinet consequently resigned in December 1958. The Finnish Foreign Ministry ignored United States offers for help as promised by Ambassador John D. Hickerson

John Dewey Hickerson (January 26, 1898 – January 18, 1989) was an American diplomat.

Biography

John D. Hickerson was born at Crawford, Texas, on January 26, 1898. He was educated at the University of Texas at Austin, receiving a Bachelor of A ...

in November 1958. The crisis was resolved by Kekkonen in January 1959, when he privately travelled to Moscow to negotiate with Khrushchev and Andrei Gromyko

Andrei Andreyevich Gromyko ( – 2 July 1989) was a Soviet politician and diplomat during the Cold War. He served as Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Soviet Union), Minister of Foreign Affairs (1957–1985) and as List of heads of state of the So ...

. The crisis established Kekkonen as having the extra-constitutional authority to determine which parties may participate in government, effectively restricting the free parliamentary formation of governing coalitions for many years ahead.

The second time the Soviets helped Kekkonen was in the

The second time the Soviets helped Kekkonen was in the Note Crisis

The Note Crisis (, ) was a political crisis in Finland–Russia relations, Soviet–Finnish relations in 1961. The Soviet Union sent Finland a Letter of protest, diplomatic note on 30 October 1961, referring to the threat of war and West Germany, ...

in 1961. The most widely held view of the Note Crisis

The Note Crisis (, ) was a political crisis in Finland–Russia relations, Soviet–Finnish relations in 1961. The Soviet Union sent Finland a Letter of protest, diplomatic note on 30 October 1961, referring to the threat of war and West Germany, ...

is that the Soviet Union acted to ensure Kekkonen's reelection. Whether Kekkonen himself had organized the incident and to what extent remains debated. Several parties competing against Kekkonen had formed an alliance, ''Honka-liitto'', to promote Chancellor of Justice

The Chancellor of Justice is a government official found in some northern European countries, broadly responsible for supervising the lawfulness of government actions.

History

In 1713, the Swedish King Charles XII, preoccupied with fighting t ...

Olavi Honka, a non-partisan candidate, in the 1962 presidential elections. Kekkonen had planned to foil the ''Honka-liitto'' by calling an early parliamentary election and thus forcing his opponents to campaign against each other and together simultaneously. However, in October 1961, the Soviet Union sent a diplomatic note

Diplomatics (in American English, and in most anglophone countries), or diplomatic (in British English), is a scholarly discipline centred on the critical analysis of documents, especially historical documents. It focuses on the conventions, pr ...

proposing military "consultations" as provided by the Finno-Soviet Treaty. As a result, Honka dropped his candidacy, leaving Kekkonen with a clear majority (199 of 300 electors) in the 1962 elections. In addition to support from his own party, Kekkonen received the backing of the Swedish People's Party

The Swedish People's Party of Finland (SPP; , SFP; , RKP) is a Finnish political party founded in 1906. Its primary aim is to represent the interests of the minority Swedish-speaking population of Finland. The party is currently a participant in ...

and the Finnish People's Party, a small classical liberal party. Furthermore, the conservative National Coalition Party quietly supported Kekkonen, although they had no official presidential candidate after Honka's withdrawal. Following the Note Crisis, genuine opposition to Kekkonen disappeared, and he acquired an exceptionally strong—later even autocratic—status as the political leader of Finland.

Kekkonen's policies, especially towards the USSR

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, were criticised within his own party by Veikko Vennamo

Veikko Emil Aleksander Vennamo (originally ''Fennander'') (11 June 1913 – 12 June 1997) was a Finland, Finnish politician. In 1959, he founded the Finnish Rural Party (''Suomen Maaseudun Puolue''), which was succeeded by the True Finns in 1995. ...

, who broke off his Centre Party affiliation when Kekkonen was elected president in 1956. In 1959, Vennamo founded the Finnish Rural Party

The Finnish Rural Party (, SMP; , FLP) was an agrarian and populist political party in Finland. Starting as a breakaway faction of the Agrarian League in 1959 as the Small Peasants' Party of Finland (Suomen Pientalonpoikien Puolue), the party ...

, the forerunner of the nationalist True Finns

The Finns Party ( , PS; , Sannf), formerly known as the True Finns, is a right-wing populist political party in Finland. It was founded in 1995 following the dissolution of the Finnish Rural Party.

The party achieved its electoral breakthro ...

.

Second term (1962–68)

In the 1960s Kekkonen was responsible for a number of foreign-policy initiatives, including the

In the 1960s Kekkonen was responsible for a number of foreign-policy initiatives, including the Nordic

Nordic most commonly refers to:

* Nordic countries, the northern European countries of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden, and their North Atlantic territories

* Scandinavia, a cultural, historical and ethno-linguistic region in northern ...

nuclear-free zone

A nuclear-free zone is an area in which nuclear weapons and nuclear power plants are banned. The specific ramifications of these depend on the locale in question, but are generally distinct from nuclear-weapon-free zones, in that the latter only b ...

proposal, a border agreement with Norway, and a 1969 Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe. The purpose of these initiatives was to avoid the enforcement of the military articles in the Finno-Soviet Treaty which called for military co-operation with the Soviet Union. Kekkonen thereby hoped to strengthen Finland's moves toward a policy of neutrality. Following the invasion of Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

in 1968, pressure for neutrality increased. Kekkonen informed the Soviet Union in 1970 that if it was no longer prepared to recognise Finland's neutrality, he would not continue as president, nor would the Finno-Soviet Treaty be extended.

Third term (1968–78)

Kekkonen was re-elected for a third term in 1968. That year, he was supported by five political parties: the Centre Party, theSocial Democrats

Social democracy is a social, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achieving social equality. In modern practice, s ...

, the Social Democratic Union of Workers and Smallholders

Social Democratic Union of Workers and Smallholders (, TPSL) was a political party in Finland. TPSL originated as a fraction of the Social Democratic Party of Finland, headed by Emil Skog and Aarre Simonen. Skog was the former chairman of SDP and ...

(a short-lived SDP faction), the Finnish People's Democratic League

Finnish People's Democratic League (, SKDL; , DFFF) was a Finnish political organisation with the aim of uniting those left of the Finnish Social Democratic Party. It was founded in 1944 as the anti-communist laws in Finland were repealed due ...

(a communist front), and the Swedish People's Party. He received 201 votes in the electoral college, whereas the National Coalition party

The National Coalition Party (NCP; , Kok; , Saml) is a liberal conservatism, liberal-conservative List of political parties in Finland, political party in Finland. It is the current governing political party of Finland.

Founded in 1918, the ...

's candidate finished second with 66 votes. Vennamo came third with 33 votes. Although Kekkonen was re-elected with two-thirds of the vote, he was so displeased with his opponents and their behaviour that he publicly refused to stand for the presidency again. Vennamo's bold and constant criticisms of his presidency and policies especially infuriated Kekkonen, who labelled him a "cheat" and "demagogue".

Initially, Kekkonen had intended to retire at the end of this term, and the Centre Party already began to prepare for his succession by Ahti Karjalainen

Ahti Kalle Samuli Karjalainen (10 February 1923 – 7 September 1990) was a Finland, Finnish economist and politician. He was a member of the Agrarian League (later known as Keskusta, Centre Party) and served two terms as Prime Minister of Finlan ...

. However, Kekkonen began to see Karjalainen as a rival instead, and eventually rejected the idea.

Term extension (1973)

On 18 January 1973, the Finnish Parliament extended Kekkonen's presidential term by four years with a Derogation law (an ad hoc law made as an exception to the constitution). By this time, Kekkonen had secured the backing of most political parties, but the major right-wing

On 18 January 1973, the Finnish Parliament extended Kekkonen's presidential term by four years with a Derogation law (an ad hoc law made as an exception to the constitution). By this time, Kekkonen had secured the backing of most political parties, but the major right-wing National Coalition Party

The National Coalition Party (NCP; , Kok; , Saml) is a liberal conservatism, liberal-conservative List of political parties in Finland, political party in Finland. It is the current governing political party of Finland.

Founded in 1918, the ...

, which Kekkonen had opposed, was still skeptical and stood in the way of the required 5/6 majority. Concurrently, Finland was negotiating a free-trade agreement

A free trade agreement (FTA) or treaty is an agreement according to international law to form a free-trade area between the cooperating states. There are two types of trade agreements: bilateral and multilateral. Bilateral trade agreements occur ...

with the EEC

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organisation created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957,Today the largely rewritten treaty continues in force as the ''Treaty on the functioning of the European Union'', as renamed by the Lisbo ...

, a deal that was seen as vital by Finnish industry, as the United Kingdom, an important buyer of Finnish exports, had left the European Free Trade Association

The European Free Trade Association (EFTA) is a regional trade organization and free trade area consisting of four List of sovereign states and dependent territories in Europe, European states: Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. ...

to become a member of the EEC. Kekkonen implied that only he personally could satisfy the Soviet Union that the deal would not threaten Soviet interests. The tactic secured National Coalition support for the term extension. The elimination of any significant opposition and competition meant he became Finland's ''de facto'' political autocrat. His power reached its zenith in 1975 when he dissolved parliament and hosted the

The elimination of any significant opposition and competition meant he became Finland's ''de facto'' political autocrat. His power reached its zenith in 1975 when he dissolved parliament and hosted the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe

The Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) was a key element of the détente process during the Cold War. Although it did not have the force of a treaty, it recognized the boundaries of postwar Europe and established a mechanism ...

(CSCE) in Helsinki with the assistance of a caretaker government.

Fourth term (1978–82)

After nine political parties supported Kekkonen's candidacy in the 1978 presidential election, including the Social Democratic, Centre and National Coalition parties, no serious rivals remained. He humiliated his opponents by not appearing in televised presidential debates and went on to win 259 out of the 300 electoral college votes, with his nearest rival,Raino Westerholm

Raino Olavi Westerholm (20 November 1919 – 1 June 2017) was a Finnish politician. Westerholm was born in Kuusankoski. He was leader of the Finnish Christian League from 1973 to 1982. He was also member of the Finnish parliament from 1970 to 19 ...

of the Christian Union, receiving only 25.

According to Finnish historians and political journalists, there were at least three reasons why Kekkonen clung on to the Presidency. First, he did not believe that any of his successor candidates would manage Finland's Soviet foreign policy well enough. Second, until at least the summer of 1978, he considered there was room for improvement in Finnish-Soviet relations and that his experience was vital to the process. This is exemplified by the use of his diplomatic skills to reject the Soviet Defence Minister Dmitriy Ustinov

Dmitriy Fyodorovich Ustinov (; 30 October 1908 – 20 December 1984) was a Soviet politician and a Marshal of the Soviet Union during the Cold War. He served as a Central Committee secretary in charge of the Soviet military–industrial comple ...

's offer to arrange a joined Soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

- Finnish military exercise

A military exercise, training exercise, maneuver (manoeuvre), or war game is the employment of military resources in Military education and training, training for military operations. Military exercises are conducted to explore the effects of ...

.

Third, he believed that by working for as long as possible he would remain healthy and live longer.Pekka Hyvärinen, "Finland's Man"; Juhani Suomi, "A Ski Trail Being Snowed In" Kekkonen's most severe critics, such as Veikko Vennamo

Veikko Emil Aleksander Vennamo (originally ''Fennander'') (11 June 1913 – 12 June 1997) was a Finland, Finnish politician. In 1959, he founded the Finnish Rural Party (''Suomen Maaseudun Puolue''), which was succeeded by the True Finns in 1995. ...

, claimed that he remained President so long mainly because he and his closest associates were power-hungry. In 1980 Kekkonen was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize

The International Lenin Peace Prize (, ''mezhdunarodnaya Leninskaya premiya mira)'' was a Soviet Union award named in honor of Vladimir Lenin. It was awarded by a panel appointed by the Soviet government, to notable individuals whom the panel ...

.

Later life and death

From December 1980 onwards, Kekkonen suffered from an undisclosed disease that appeared to affect his brain functions, sometimes leading to delusional thoughts. He had begun to suffer occasional brief memory lapses as early as the autumn of 1972; they became more frequent during the late 1970s. Around the same time, Kekkonen's eyesight deteriorated so much that for his last few years in office, all of his official papers had to be typed in block letters. Kekkonen had also suffered from a failing sense of balance since the mid-1970s and from enlargement of his

From December 1980 onwards, Kekkonen suffered from an undisclosed disease that appeared to affect his brain functions, sometimes leading to delusional thoughts. He had begun to suffer occasional brief memory lapses as early as the autumn of 1972; they became more frequent during the late 1970s. Around the same time, Kekkonen's eyesight deteriorated so much that for his last few years in office, all of his official papers had to be typed in block letters. Kekkonen had also suffered from a failing sense of balance since the mid-1970s and from enlargement of his prostate gland

The prostate is an male accessory gland, accessory gland of the male reproductive system and a muscle-driven mechanical switch between urination and ejaculation. It is found in all male mammals. It differs between species anatomically, chemica ...

since 1974. He was also subject to occasional violent headaches and suffered from diabetes

Diabetes mellitus, commonly known as diabetes, is a group of common endocrine diseases characterized by sustained high blood sugar levels. Diabetes is due to either the pancreas not producing enough of the hormone insulin, or the cells of th ...

from the autumn of 1979. Rumors about his declining health had begun to circulate in the mid to late 1970s, but the press attempted to silence these rumors to respect the president's privacy.

According to biographer Juhani Suomi, Kekkonen gave no thought to resigning until his physical condition began to deteriorate in July 1981. The 80-year-old president then began to seriously consider resigning, most likely in early 1982. Prime Minister Mauno Koivisto

Mauno Henrik Koivisto (, 25 November 1923 – 12 May 2017) was a Finnish politician who served as the ninth president of Finland from 1982 to 1994. He also served as the country's prime minister twice, from 1968 to 1970 and again from 1979 to 19 ...

finally dealt a defeat to Kekkonen in 1981. In April, Koivisto did what no one else had dared to during Kekkonen's presidency by stating that under the constitution, the prime minister and cabinet were responsible to Parliament, not to the President. Kekkonen asked Koivisto to resign, but he refused. This is generally seen as the death knell of the Kekkonen era; Kekkonen, who felt that he had lost a significant amount of his authority, never fully recovered from the shock caused by this event.

Historians and journalists debate the precise meaning of this dispute. According to Seppo Zetterberg, Allan Tiitta, and Pekka Hyvärinen, Kekkonen wanted to force Koivisto to resign to decrease his chances of succeeding him as president. In contrast, Juhani Suomi believed the dispute involved scheming between Koivisto and rival prospective presidential candidates. Kekkonen at times criticised Koivisto for making political decisions too slowly and for his vacillation, especially for speaking too unclearly and philosophically.

Kekkonen became ill in August during a fishing trip to Iceland

Iceland is a Nordic countries, Nordic island country between the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans, on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge between North America and Europe. It is culturally and politically linked with Europe and is the regi ...

. He went on medical leave on 10 September, before finally resigning due to ill health on 26 October 1981. There is no report available about his illness, as the papers have been moved to an unknown location, but it is commonly believed that he suffered from vascular dementia

Vascular dementia is dementia caused by a series of strokes. Restricted blood flow due to strokes reduces oxygen and glucose delivery to the brain, causing cell injury and neurological deficits in the affected region. Subtypes of vascular dement ...

, probably due to atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis is a pattern of the disease arteriosclerosis, characterized by development of abnormalities called lesions in walls of arteries. This is a chronic inflammatory disease involving many different cell types and is driven by eleva ...

.

Kekkonen withdrew from politics during his final years. He died at Tamminiemi

Tamminiemi (; ) is a villa and Historic house museum, house museum located in the Meilahti district of Helsinki, Finland. It was one of the three official residences of the President of Finland, from 1940 to 1982. From 1956, until his death in 19 ...

on August 31, 1986, three days before his 86th birthday, and was buried with full honours. His heirs restricted access to his diaries and later an "authorised" biography by Juhani Suomi was commissioned, the author subsequently defending the interpretation of the history therein and denigrating most other interpretations. Critics have questioned the value of this work; the historian Hannu Rautkallio

Hannu, Hennu or Henenu was an Egyptian noble, serving as ''m-r-pr'' "majordomo" to Mentuhotep III in the 20th century BC. He reportedly re-opened the trade routes to Punt and Libya for the Middle Kingdom of Egypt. He was buried in a tomb in Dei ...

considered the biography little else than a "commercial project" designed for selling books rather than aiming for historical accuracy.

Legacy

Some of Kekkonen's actions remain controversial in modern Finland, and disputes continue about how to interpret many of his policies and actions. He often used what was termed the "Moscow card" when his authority was threatened, but he was not the only Finnish politician with close relations to Soviet representatives. Kekkonen's authoritarian behavior during his presidential term was one of the main reasons for the reforms of the Finnish Constitution in 1984–2003. Under these, the powers of Parliament and the prime minister were increased at the expense of presidential power. Several of the changes were initiated by Kekkonen's successors. * Presidential tenure was limited to two consecutive terms. * The President's role in cabinet formation was restricted. * The President was to be elected directly, not by anelectoral college

An electoral college is a body whose task is to elect a candidate to a particular office. It is mostly used in the political context for a constitutional body that appoints the head of state or government, and sometimes the upper parliament ...

.

* The President could no longer dissolve Parliament without the support of the Prime Minister.

* The Prime Minister's role in shaping the foreign relations of Finland

The foreign relations of Finland are the responsibility of the president of Finland, who leads foreign policy in cooperation with the government. Implicitly the government is responsible for internal policy and decision making in the European ...

was enhanced.

Although controversial, his policy of neutrality allowed trade with both the Communist and Western blocs. The bilateral trade policy with the Soviet Union was lucrative for many Finnish businesses. His term saw a period of high sustained economic growth and increasing integration with the West. He negotiated entrance into EFTA

The European Free Trade Association (EFTA) is a regional trade organization and free trade area consisting of four European states: Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. The organization operates in parallel with the European Union ...

and thus was an early beginner for Finnish participation in European integration, which later culminated in full membership in the EU and the euro. He remained highly popular during his term, even though such a profile approached that of a cult of personality

A cult of personality, or a cult of the leader,Cas Mudde, Mudde, Cas and Kaltwasser, Cristóbal Rovira (2017) ''Populism: A Very Short Introduction''. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 63. is the result of an effort which is made to create ...

towards the end of his term. He is still popular among many of his contemporaries, particularly in his own Centre Party.

Cabinets

* Kekkonen I Cabinet * Kekkonen II Cabinet * Kekkonen III Cabinet * Kekkonen IV Cabinet * Kekkonen V CabinetTributes

* The

* The Urho Kekkonen National Park

Urho Kekkonen National Park (, , often abbreviated to ''UKK'') is a national park in Lapland, Finland, situated in area of municipalities of Savukoski, Sodankylä and Inari. Established in 1983 and covering , it is one of Finland's largest prot ...

, Finland's second largest national park, is named after Kekkonen.

* The Urho Kekkonen museum was opened in Tamminiemi

Tamminiemi (; ) is a villa and Historic house museum, house museum located in the Meilahti district of Helsinki, Finland. It was one of the three official residences of the President of Finland, from 1940 to 1982. From 1956, until his death in 19 ...

in 1987.

* In Helsinki

Helsinki () is the Capital city, capital and most populous List of cities and towns in Finland, city in Finland. It is on the shore of the Gulf of Finland and is the seat of southern Finland's Uusimaa region. About people live in the municipali ...

, the former Kampinkatu (Kamppi

Kamppi () is a Subdivisions of Helsinki#Neighbourhoods, neighbourhood in the centre of Helsinki, the capital of Finland. The name originally referred to a small area known as the "Kamppi field" (see below), but according to the current official d ...

Street) was renamed Urho Kekkosen katu in Finnish and Urho Kekkonens gata in Swedish (Urho Kekkonen Street) in 1980.

* In Tampere

Tampere is a city in Finland and the regional capital of Pirkanmaa. It is located in the Finnish Lakeland. The population of Tampere is approximately , while the metropolitan area has a population of approximately . It is the most populous mu ...

, the Paasikivi–Kekkonen Road (''Paasikiven–Kekkosentie'') is named after both Kekkonen and J. K. Paasikivi.

* Such was his impact on the Finnish political scene that Kekkonen appeared on the Mk.500 banknote

A banknote or bank notealso called a bill (North American English) or simply a noteis a type of paper money that is made and distributed ("issued") by a bank of issue, payable to the bearer on demand. Banknotes were originally issued by commerc ...

during his term as president. The series of Finnish Markka banknotes used at this time was the second-to-last design series in the entire history of the currency. It is a rare example of a living non-royal head of state being depicted on currency. This banknote was declared Finland's most beautiful note according to voting organised by the commemorative coins and medal marketer Suomen Moneta on 1 April 2011.

* To date, President Kekkonen is the only Finnish person to have a collector coin issued in his honour during his lifetime.

** 25 years of presidency (Silver jubilee

Silver Jubilee marks a 25th anniversary. The anniversary celebrations can be of a wedding anniversary, the 25th year of a monarch's reign or anything that has completed or is entering a 25-year mark.

Royal Silver Jubilees since 1750

Note: This ...

) of U. K. Kekkonen. The silver collector's coin that pays homage to Kekkonen was issued in 1981 when he had served 25 years as the president. The coin also commemorated Kekkonen's 80th birthday the previous year. Designed by sculptor Nina Terno, the symbolic reverse side of the coin depicts a ploughman with a pair of horses pulling a harrow. In 2010, the Mint of Finland is re-released coins minted in 1981 from its vaults.

** President U. K. Kekkonen 75th Birthday. The silver coin was issued on Kekkonen's birthday on 3 September 1975 to commemorate the president's 75th birthday. Designed by sculptor Heikki Häiväoja

Heikki Aulis Häiväoja (May 25, 1929 in Jämsä, Finland — September 15, 2019 in Kauniainen), was a Finnish sculptor and designer of the Finnish euro coins

Finnish euro coins (Finnish language, Finnish: Suomalaiset eurokolikot) (Swedish languag ...

, the reverse side depicts four tall pine tree

A pine is any conifer tree or shrub in the genus ''Pinus'' () of the family Pinaceae. ''Pinus'' is the sole genus in the subfamily Pinoideae.

''World Flora Online'' accepts 134 species-rank taxa (119 species and 15 nothospecies) of pines as c ...

s that symbolise the first four terms of President Kekkonen.

* Posti Group

Group (previously during 1994–2007 and during 2007–2015), trading internationally as Posti Group Corporation, is the main Finnish postal service delivering mail and parcels in Finland. The State of Finland is the sole shareholder of th ...

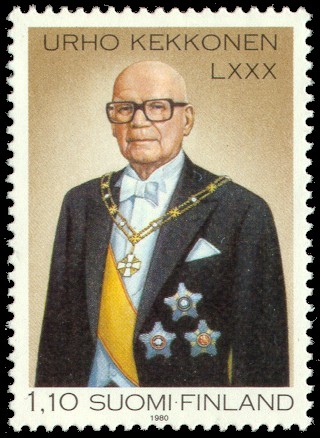

(formerly ' in Finnish) has issued four President Kekkonen commemorative postage stamps.

** Name: 60th birthday of President Urho Kekkonen, issued: 3 September 1960, designed by Olavi Vepsäläinen

** Name: 70th birthday of President Kekkonen, issued: 3 September 1970, designed by Eeva Oivo

** Name: 80th birthday of President Kekkonen, issued: 3 September 1980, designed by Eeva Oivo

** Name: President Kekkonen's mourning stamp, issued: 30 September 1986, designed by Eeva Oivo

* A monument to Urho Kekkonen and Alexei Kosygin

Alexei Nikolayevich Kosygin (–18 December 1980) was a Soviet people, Soviet statesman during the Cold War. He served as the Premier of the Soviet Union from 1964 to 1980 and, alongside General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev, was one of its most ...

was erected in Kostomuksha

Kostomuksha (; ; ; ) is a town in the northwest of the Republic of Karelia, Russia, located from the border with Finland, on the shore of Lake Kontoki. Population:

Geography

The nearest large cities in Russia are St. Petersburg and ...

, Russia in 2013.

* A pub in Etu-Töölö,

* A pub in Etu-Töölö, Helsinki

Helsinki () is the Capital city, capital and most populous List of cities and towns in Finland, city in Finland. It is on the shore of the Gulf of Finland and is the seat of southern Finland's Uusimaa region. About people live in the municipali ...

was named St. Urho's Pub

St. Urho's Pub is a beer restaurant located at Museokatu 10 in Etu-Töölö, Helsinki, Finland. The restaurant used to be a local favourite of former President of Finland Urho Kekkonen

Urho Kaleva Kekkonen (; 3 September 1900 – 31 August ...

in honour of Kekkonen being a regular patron.

In popular culture

Film and television

* The vote count from the1978 elections

The following elections occurred in the year 1978.

Africa

* 1978 Cameroonian parliamentary election

* 1978 Comorian legislative election

* 1978 Comorian presidential election

* 1978 Egyptian protection of national unity and social peace referend ...

was broadcast on the radio, and has been shown numerous times in television documentaries. The monotonous reading out of the votes, in groups of five, is still well-recognised in Finnish popular culture, and broadly quoted and paraphrased; "Kekkonen, Kekkonen, Kekkonen, Kekkonen, Kekkonen."

* A portrait of Kekkonen is stolen by the protagonist of the 1988 Aki Kaurismäki