USS Sailfish (SS-192) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

USS ''Sailfish'' (SS-192), was a of the

On 12 May 1939, following a yard overhaul, ''Squalus'' began a series of test dives off

On 12 May 1939, following a yard overhaul, ''Squalus'' began a series of test dives off

After being decommissioned on 27 October 1945, efforts by the city of Portsmouth and area residents to have the submarine kept intact as a memorial were not successful. Agreement was reached to have her

After being decommissioned on 27 October 1945, efforts by the city of Portsmouth and area residents to have the submarine kept intact as a memorial were not successful. Agreement was reached to have her

Presidential Unit Citation for outstanding performance on her 10th war patrol

*

Presidential Unit Citation for outstanding performance on her 10th war patrol

*

Voyages of Discovery

/ref>

Naval Historical Center, Online Library of Selected Images: USS ''Squalus''/''Sailfish'' (SS-192)

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Sailfish (Ss-192) 1938 ships Maritime incidents in 1939 Sargo-class submarines Ships built in Kittery, Maine United States submarine accidents World War II submarines of the United States

United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

, originally named ''Squalus''. As ''Squalus'', the submarine sank off the coast of New Hampshire

New Hampshire ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

during test dives on 23 May 1939. The sinking drowned 26 crew members, but an ensuing rescue operation, using the McCann Rescue Chamber

The McCann Submarine Rescue Chamber is a device for rescuing submariners from a submarine that is unable to surface.

History

During the first two decades of the United States Navy Submarine Force, there were several accidents in which Navy submar ...

for the first time, saved the lives of the remaining 33 aboard. ''Squalus'' was salvaged in late 1939 and recommissioned as ''Sailfish'' in May 1940.

As ''Sailfish'', the vessel conducted numerous patrols in the Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War or the Pacific Theatre, was the Theater (warfare), theatre of World War II fought between the Empire of Japan and the Allies of World War II, Allies in East Asia, East and Southeast As ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, earning nine battle stars

A service star is a miniature bronze or silver five-pointed star in diameter that is authorized to be worn by members of the eight uniformed services of the United States on medals and ribbons to denote an additional award or service period. T ...

. She was decommissioned in October 1945 and later scrapped. Her conning tower

A conning tower is a raised platform on a ship or submarine, often armoured, from which an officer in charge can conn (nautical), conn (conduct or control) the vessel, controlling movements of the ship by giving orders to those responsible for t ...

is on display at Portsmouth Naval Shipyard

The Portsmouth Naval Shipyard (PNS), often called the Portsmouth Navy Yard, is a United States Navy shipyard on Seavey's Island in Kittery, Maine, bordering Portsmouth, New Hampshire. The naval yard lies along the southern boundary of Maine on ...

in Kittery

Kittery is a town in York County, Maine, United States, and the oldest incorporated town in Maine. Home to the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard on Seavey's Island, Kittery includes Badger's Island, the seaside district of Kittery Point, and part of th ...

, Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

.

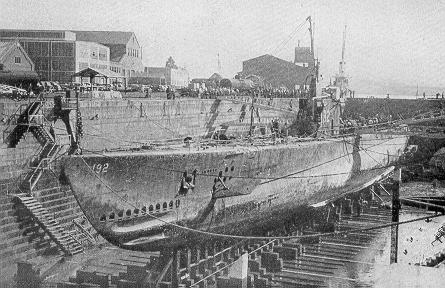

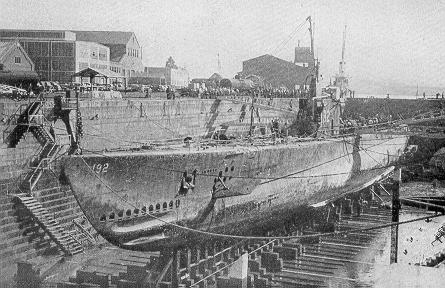

Construction and commissioning

''Squalus''skeel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element of a watercraft, important for stability. On some sailboats, it may have a fluid dynamics, hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose as well. The keel laying, laying of the keel is often ...

was laid on 18 October 1937 by the Portsmouth Navy Yard

The Portsmouth Naval Shipyard (PNS), often called the Portsmouth Navy Yard, is a United States Navy shipyard on Seavey's Island in Kittery, Maine, bordering Portsmouth, New Hampshire. The naval yard lies along the southern boundary of Maine on ...

in Kittery

Kittery is a town in York County, Maine, United States, and the oldest incorporated town in Maine. Home to the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard on Seavey's Island, Kittery includes Badger's Island, the seaside district of Kittery Point, and part of th ...

, Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

, the only ship of the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

named for the squalus

''Squalus'' is a genus of dogfish sharks in the family (biology), family Squalidae. Commonly known as spurdogs, these sharks are characterized by smooth dorsal fin spines, teeth in upper and lower fish jaw, jaws similar in size, caudal peduncle ...

, a type of shark

Sharks are a group of elasmobranch cartilaginous fish characterized by a ribless endoskeleton, dermal denticles, five to seven gill slits on each side, and pectoral fins that are not fused to the head. Modern sharks are classified within the ...

. She was launched on 14 September 1938, sponsored by Mrs. Thomas C. Hart, wife of Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in many navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force. Admiral is ranked above vice admiral and below admiral of ...

Thomas C. Hart

Thomas Charles Hart (June 12, 1877July 4, 1971) was an admiral in the United States Navy, whose service extended from the Spanish–American War through World War II. Following his retirement from the navy, he served briefly as a United States Se ...

, and commissioned on 1 March 1939 with Lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a Junior officer, junior commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations, as well as fire services, emergency medical services, Security agency, security services ...

Oliver F. Naquin in command.

Sinking of ''Squalus'' and recommissioning as ''Sailfish''

On 12 May 1939, following a yard overhaul, ''Squalus'' began a series of test dives off

On 12 May 1939, following a yard overhaul, ''Squalus'' began a series of test dives off Portsmouth, New Hampshire

Portsmouth is a city in Rockingham County, New Hampshire, Rockingham County, New Hampshire, United States. At the 2020 United States census, 2020 census it had a population of 21,956. A historic seaport and popular summer tourist destination on ...

. After successfully completing 18 dives, she went down again off the Isles of Shoals

The Isles of Shoals are a group of small islands and tidal ledges situated approximately off the east coast of the United States, straddling the border of the states of Maine and New Hampshire.

They have been occupied for more than 400 years, ...

on the morning of 23 May at . Failure of the main induction valve (the means of letting in fresh air when on the surface). A repeat of incidents with and . After this accident, the more reliable Electric Boat

An electric boat is a powered watercraft driven by electric motors, which are powered by either on-board battery packs, solar panels or generators.

While a significant majority of water vessels are powered by diesel engines, with sail power ...

design was adopted for new Navy-built subs. caused the flooding of the aft torpedo room, both engine rooms, and the crew's quarters, drowning 26 men immediately. Quick action by the crew prevented the other compartments from flooding. ''Squalus'' bottomed in of water.

''Squalus'' was initially located by her sister boat

A sister ship is a ship of the same class or of virtually identical design to another ship. Such vessels share a nearly identical hull and superstructure layout, similar size, and roughly comparable features and equipment. They often share a ...

, . The two submarines communicated using a telephone marker buoy until the cable parted. Divers from the submarine rescue ship

A submarine rescue ship is a surface support ship for submarine rescue and deep-sea salvage operations. Methods employed include the McCann Rescue Chamber, deep-submergence rescue vehicles (DSRV's) and diving operations.

List of active su ...

began rescue operations under the direction of the salvage and rescue expert Lieutenant Commander Charles B. "Swede" Momsen, using the new McCann Rescue Chamber

The McCann Submarine Rescue Chamber is a device for rescuing submariners from a submarine that is unable to surface.

History

During the first two decades of the United States Navy Submarine Force, there were several accidents in which Navy submar ...

. The senior medical officer for the operations was Dr. Charles Wesley Shilling. Overseen by researcher Albert R. Behnke

Captain Albert Richard Behnke Jr. USN (ret.) (August 8, 1903 – January 16, 1992) was an American physician, who was principally responsible for developing the U.S. Naval Medical Research Institute. Behnke separated the symptoms of Arterial Gas ...

, the divers used recently developed heliox

Heliox is a breathing gas mixture of helium (He) and oxygen (O2). It is used as a medical treatment for patients with difficulty breathing because this mixture generates less resistance than atmospheric air when passing through the airways of ...

diving schedules and successfully avoided the cognitive impairment symptoms associated with such deep dives, thereby confirming Behnke's theory of nitrogen narcosis

Nitrogen narcosis (also known as narcosis while diving, inert gas narcosis, raptures of the deep, Martini effect) is a reversible alteration in consciousness that occurs while diving at depth. It is caused by the anesthetic effect of certain gas ...

. The divers rescued all 33 survivors (32 crew members and a civilian) on board the sunken submarine. Four enlisted divers, Chief Machinist's Mate William Badders, Chief Boatswain's Mate Orson L. Crandall

Orson Leon Crandall (February 2, 1903 – May 10, 1960) was a United States Navy diver and a recipient of America's highest military decoration - the Medal of Honor.

Biography

Orson Crandall was born on February 2, 1903, in Saint Joseph, Miss ...

, Chief Metalsmith James H. McDonald, and Chief Torpedoman John Mihalowski, were awarded the Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest Awards and decorations of the United States Armed Forces, military decoration and is awarded to recognize American United States Army, soldiers, United States Navy, sailors, Un ...

for their work during the rescue and subsequent salvage. The successful rescue of the ''Squalus'' survivors is in marked contrast to the loss of in Liverpool Bay in England just a week later, with four survivors from 104 people aboard.

The naval authorities felt raising ''Squalus'' was important, as she incorporated a succession of new design features. With a thorough investigation of why she sank, more confidence could be placed in the new construction, or alteration of existing designs could be undertaken when cheapest and most efficient to do so. Furthermore, given similar previous accidents in and (indeed, in , as far back as 1920), determining a cause was necessary.

The ''Squalus'' salvage unit was commanded by Rear Admiral Cyrus W. Cole, commandant of the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, who supervised salvage officer Lieutenant Floyd A. Tusler from the Construction Corps. Cole also requested experienced Commander Henry Hartley

Henry Hartley (8 May 18846 March 1953) was a highly decorated officer in the United States Navy who reached the rank of rear admiral. A veteran of both World Wars, he began his career as Apprentice seaman and rose to the rank of commodore durin ...

as his technical aide. Tusler's plan was to lift the submarine in three stages to prevent it from rising too quickly, out of control, with one end up, in which case the likelihood of it sinking again would be high. For 50 days, divers worked to pass cables underneath the submarine and attach pontoons for buoyancy. On 13 July 1939, the stern was raised successfully, but when the men attempted to free the bow from the hard blue clay, the vessel began to rise far too quickly, slipping its cables. Ascending vertically, the submarine broke the surface, and of the bow reached into the air for not more than ten seconds before she sank once again all the way to the bottom. Momsen said of the mishap, "pontoons were smashed, hoses cut and I might add, hearts were broken." After 20 more days of preparation, with a radically redesigned pontoon and cable arrangement, the next lift was successful, as were two further operations. ''Squalus'' was towed into Portsmouth on 13 September, and decommissioned on 15 November. A total of 628 dives had been made in rescue and salvage operations.

Operational history of ''Sailfish''

Renamed ''Sailfish'' on 9 February 1940, she became the first boat of the U.S. Navy named for thesailfish

The sailfish is one or two species of marine fish in the genus ''Istiophorus'', which belong to the family Istiophoridae ( marlins). They are predominantly blue to gray in colour and have a characteristically large dorsal fin known as the ...

. After reconditioning, repair, and overhaul, she was recommissioned on 15 May 1940 with Lieutenant Commander Morton C. Mumma Jr. (Annapolis

Annapolis ( ) is the capital of the U.S. state of Maryland. It is the county seat of Anne Arundel County and its only incorporated city. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east o ...

, class of 1930) in command.

With refit completed in mid-September, ''Sailfish'' departed Portsmouth on 16 January 1941 and headed for the Pacific. Transiting the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal () is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Caribbean Sea with the Pacific Ocean. It cuts across the narrowest point of the Isthmus of Panama, and is a Channel (geography), conduit for maritime trade between th ...

, she arrived at Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the Reci ...

in early March, after refueling at San Diego. The submarine then sailed west to Manila

Manila, officially the City of Manila, is the Capital of the Philippines, capital and second-most populous city of the Philippines after Quezon City, with a population of 1,846,513 people in 2020. Located on the eastern shore of Manila Bay on ...

where she joined the Asiatic Fleet

The United States Asiatic Fleet was a fleet of the United States Navy during much of the first half of the 20th century. Before World War II, the fleet patrolled the Philippine Islands. Much of the fleet was destroyed by the Japanese by Februar ...

until the attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Empire of Japan on the United States Pacific Fleet at Naval Station Pearl Harbor, its naval base at Pearl Harbor on Oahu, Territory of ...

.

During the Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War or the Pacific Theatre, was the Theater (warfare), theatre of World War II fought between the Empire of Japan and the Allies of World War II, Allies in East Asia, East and Southeast As ...

, the captain of the renamed boat issued standing orders that if any man on the boat said the word "Squalus", he was to be marooned at the next port of call. This led to crew members referring to their boat as "Squailfish". That went over almost as well; a court martial

A court-martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the mili ...

was threatened for anyone heard using it.

World War II

First five patrols: December 1941 – August 1942

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, ''Sailfish'' departed Manila on her first war patrol, destined for the west coast ofLuzon

Luzon ( , ) is the largest and most populous List of islands in the Philippines, island in the Philippines. Located in the northern portion of the List of islands of the Philippines, Philippine archipelago, it is the economic and political ce ...

. Early on 10 December, she sighted a landing force, supported by cruiser

A cruiser is a type of warship. Modern cruisers are generally the largest ships in a fleet after aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships, and can usually perform several operational roles from search-and-destroy to ocean escort to sea ...

s and destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, maneuverable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy, or carrier battle group and defend them against a wide range of general threats. They were conceived i ...

s, but could not gain firing position. On the night of 13 December, she made contact with two Japanese destroyers and began a submerged attack; the destroyers detected her, dropping several depth charge

A depth charge is an anti-submarine warfare (ASW) weapon designed to destroy submarine

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited ...

s, while ''Sailfish'' fired two torpedoes. Despite a large explosion nearby, no damage was done, and the destroyers counterattacked with 18–20 depth charges. She returned to Manila on 17 December.

Her second patrol (now under the command of Richard G. Voge begun on 21 December, took the submarine to waters off Formosa

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The island of Taiwan, formerly known to Westerners as Formosa, has an area of and makes up 99% of the land under ROC control. It lies about across the Taiwan Strait f ...

. On the morning of 27 January 1942, off Halmahera

Halmahera, formerly known as Jilolo, Gilolo, or Jailolo, is the largest island in the Maluku Islands. It is part of the North Maluku Provinces of Indonesia, province of Indonesia, and Sofifi, the capital of the province, is located on the west coa ...

, near Davao, she sighted a , making a daylight submerged attack with four torpedoes, and reporting the target was damaged, for which she got credit. However, the damage could not be assessed since the cruiser's two escorts forced ''Sailfish'' to dive deep and run silent. Running at , the submarine eluded the destroyers and proceeded south toward Java

Java is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea (a part of Pacific Ocean) to the north. With a population of 156.9 million people (including Madura) in mid 2024, proje ...

. She arrived at Tjilatjap

Cilacap Regency (, also spelt: Chilachap, old spelling: Tjilatjap, Sundanese: ) is a regency () in the southwestern part of Central Java province in Indonesia. Its capital is the town of Cilacap, which had 263,098 inhabitants in mid 2024, sprea ...

on 14 February for refueling and rearming.

Departing on 19 February for her third patrol, she headed through Lombok Strait

The Lombok Strait () is a strait of the Bali Sea connecting to the Indian Ocean, and is located between the islands of Bali and Lombok in Indonesia. The Gili Islands are on the Lombok side.

Its narrowest point is at its southern opening, with a ...

to the Java Sea

The Java Sea (, ) is an extensive shallow sea on the Sunda Shelf, between the Indonesian islands of Borneo to the north, Java to the south, Sumatra to the west, and Sulawesi to the east. Karimata Strait to its northwest links it to the South Ch ...

. After sighting the heavy cruiser

A heavy cruiser was a type of cruiser, a naval warship designed for long range and high speed, armed generally with naval guns of roughly 203 mm (8 inches) in calibre, whose design parameters were dictated by the Washington Naval Treat ...

and two escorts heading for Sunda Strait

The Sunda Strait () is the strait between the Indonesian islands of Java island, Java and Sumatra. It connects the Java Sea with the Indian Ocean.

Etymology

The strait takes its name from the Sunda Kingdom, which ruled the western portion of Ja ...

following the Allied defeat in the Battle of the Java Sea

The Battle of the Java Sea (, ) was a decisive naval battle of the Pacific campaign of World War II.

Allied navies suffered a disastrous defeat at the hand of the Imperial Japanese Navy on 27 February 1942 and in secondary actions over succ ...

, ''Sailfish'' intercepted an enemy destroyer on 2 March. Following an unsuccessful attack, she was forced to dive deep to escape the ensuing depth-charge attack from the destroyer and patrol aircraft. That night, near the mouth of Lombok Strait, she spotted what appeared to be the aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and hangar facilities for supporting, arming, deploying and recovering carrier-based aircraft, shipborne aircraft. Typically it is the ...

, escorted by four destroyers. ''Sailfish'' fired four torpedoes, scoring two hits. Leaving the target aflame and dead in the water, ''Sailfish'' dove, the escorts delivering 40 depth charges in the next 90 minutes. She eluded destroyers and aircraft and arrived at Fremantle, Western Australia

Fremantle () () is a port city in Western Australia located at the mouth of the Swan River (Western Australia), Swan River in the metropolitan area of Perth, the state capital. Fremantle Harbour serves as the port of Perth. The Western Australi ...

, on 19 March, to great fanfare, believed to be the first U.S. submarine to have sunk an enemy carrier. In reality, the ''Kaga'' was scuttled in June, 1942, after damage sustained during the Battle of Midway

The Battle of Midway was a major naval battle in the Pacific Ocean theater of World War II, Pacific Theater of World War II that took place on 4–7 June 1942, six months after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor and one month after the Battle of t ...

, in that vicinity. Postwar, ''Kaga'' was revealed to have been nowhere in the area of Lombok Strait, and the target had in fact been the aircraft ferry '' Kamogawa Maru'', still a valuable target.

The Java Sea and Celebes Sea

The Celebes Sea ( ; ) or Sulawesi Sea (; ) of the western Pacific Ocean is bordered on the north by the Sulu Archipelago and Sulu Sea and Mindanao Island of the Philippines, on the east by the Sangihe Islands chain, on the south by Sulawes ...

were the areas of ''Sailfish''s fourth patrol, from 22 March–21 May. After delivering 1,856 rounds of antiaircraft ammunition to "MacArthur MacArthur or Macarthur may refer to:

Arts and media

* INSS MacArthur, a fictional starship featured in the science fiction novel ''The Mote in God's Eye''

* ''MacArthur'' (1977 film), a movie biography of General of the Army Douglas MacArthur

* ' ...

's guerrilla

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, Partisan (military), partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include Children in the military, recruite ...

s", she made only one ship contact and was unable to attack the target before returning to Fremantle.

The submarine's fifth patrol—from 13 June through 1 August—was off the coast of Indochina

Mainland Southeast Asia (historically known as Indochina and the Indochinese Peninsula) is the continental portion of Southeast Asia. It lies east of the Indian subcontinent and south of Mainland China and is bordered by the Indian Ocean to th ...

in the South China Sea

The South China Sea is a marginal sea of the Western Pacific Ocean. It is bounded in the north by South China, in the west by the Indochinese Peninsula, in the east by the islands of Taiwan island, Taiwan and northwestern Philippines (mainly Luz ...

. On 4 July, she intercepted and tracked a large freighter, but discovered the intended target was a hospital ship

A hospital ship is a ship designated for primary function as a floating healthcare, medical treatment facility or hospital. Most are operated by the military forces (mostly navy, navies) of various countries, as they are intended to be used in or ...

and held her fire. On 9 July, she intercepted and torpedoed a Japanese freighter. One of a pair of torpedoes struck home and the ship took a 15° list

A list is a Set (mathematics), set of discrete items of information collected and set forth in some format for utility, entertainment, or other purposes. A list may be memorialized in any number of ways, including existing only in the mind of t ...

. As ''Sailfish'' went deep, a series of explosions was heard, and no further screw noises were detected. When the submarine surfaced in the area 90 minutes later, no ship was in sight. She was credited during the war with a 7000-ton ship, and although postwar examination of Japanese records confirmed no sinking in the area on that date, the ''Sailfish'' had damaged the Japanese transport ship ''Aobasan Maru'' (8811 GRT) off the coast of Indochina in position 11°31'N, 109°21'E.

''Sailfish'' observed only one other enemy vessel before the end of the patrol.

Sixth and seventh patrols: September 1942 – January 1943

Shifting her base of operations toBrisbane

Brisbane ( ; ) is the List of Australian capital cities, capital and largest city of the States and territories of Australia, state of Queensland and the list of cities in Australia by population, third-most populous city in Australia, with a ...

, ''Sailfish'' (now under the command of John R. "Dinty" Moore) got underway for her sixth patrol on 13 September and headed for the western Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands, also known simply as the Solomons,John Prados, ''Islands of Destiny'', Dutton Caliber, 2012, p,20 and passim is an island country consisting of six major islands and over 1000 smaller islands in Melanesia, part of Oceania, t ...

. On the night of 17–18 September, she encountered eight Japanese destroyers escorting a cruiser, but she was unable to attack. On 19 September, she attacked a minelayer

A minelayer is any warship, submarine, military aircraft or land vehicle deploying explosive mines. Since World War I the term "minelayer" refers specifically to a naval ship used for deploying naval mines. "Mine planting" was the term for ins ...

. The spread of three torpedoes missed, and ''Sailfish'' was forced to dive deep to escape the depth-charge counterattack. Eleven well-placed charges went off near the submarine, causing much minor damage. ''Sailfish'' returned to Brisbane on 1 November.

Underway for her seventh patrol on 24 November, ''Sailfish'' proceeded to the area south of New Britain

New Britain () is the largest island in the Bismarck Archipelago, part of the Islands Region of Papua New Guinea. It is separated from New Guinea by a northwest corner of the Solomon Sea (or with an island hop of Umboi Island, Umboi the Dampie ...

. Following an unsuccessful attack on a destroyer on 2 December, the submarine made no other contacts until 25 December, when she believed she had scored a hit on a Japanese submarine. Postwar analysis of Japanese records could not confirm a sinking in the area. During the remainder of the patrol, she made unsuccessful attacks on a cargo ship and a destroyer before ending the patrol at Pearl Harbor on 15 January 1943.

Eighth and ninth patrols: May–September 1943

After an overhaul atMare Island Naval Shipyard

The Mare Island Naval Shipyard (MINSY or MINS) was the first United States Navy base established on the Pacific Ocean and was in service 142 years from 1854 to 1996. It is located on Mare Island, northeast of San Francisco, in Vallejo, Califor ...

from 27 January–22 April, ''Sailfish'' returned to Pearl Harbor on 30 April. Departing Hawaii on 17 May for her eighth patrol, she stopped off to fuel at Midway Island

Midway Atoll (colloquial: Midway Islands; ; ) is a atoll in the North Pacific Ocean. Midway Atoll is an insular area of the United States and is an unorganized and unincorporated territory. The largest island is Sand Island, which has housi ...

and proceeded to her station off the east coast of Honshū

, historically known as , is the largest of the four main islands of Japan. It lies between the Pacific Ocean (east) and the Sea of Japan (west). It is the seventh-largest island in the world, and the second-most populous after the Indonesian ...

. Several contacts were made, but because of bad weather, were not attacked. On 15 June, she encountered two freighters off Todo Saki, escorted by three subchaser

A submarine chaser or subchaser is a type of small naval vessel that is specifically intended for anti-submarine warfare. They encompass designs that are now largely obsolete, but which played an important role in the wars of the first half of th ...

s. Firing a spread of three stern torpedoes, she observed one hit. which stopped the ''maru'' dead in the water. ''Sailfish'' was driven down by the escort, but listened on her sound gear as ''Shinju Maru'' broke up and sank. Ten days later, she found a second convoy

A convoy is a group of vehicles, typically motor vehicles or ships, traveling together for mutual support and protection. Often, a convoy is organized with armed defensive support and can help maintain cohesion within a unit. It may also be used ...

, three ships with a subchaser, and unusually, an aircraft, for escort. ''Sailfish'' once more fired three stern tubes, sinking ''Iburi Maru''; in response, the subchaser, the aircraft, and three additional escorts, pinned her down in a gruelling depth-charge attack lasting 10 hours and 98 charges, but causing only slight damage. After shaking loose pursuit, she set course for Midway on 26 June, arriving there on 3 July.

Her ninth patrol (commanded by William R. Lefavour) lasted from 25 July–16 September and covered the Formosa Strait

The Taiwan Strait is a strait separating the island of Taiwan and the Asian continent. The strait is part of the South China Sea and connects to the East China Sea to the north. The narrowest part is wide.

Names

Former names of the Taiwan ...

and waters off Okinawa

most commonly refers to:

* Okinawa Prefecture, Japan's southernmost prefecture

* Okinawa Island, the largest island of Okinawa Prefecture

* Okinawa Islands, an island group including Okinawa itself

* Okinawa (city), the second largest city in th ...

. It produced only two contacts (a 2500-ton steamer at Naha, Okinawa

is the Cities of Japan, capital city of Okinawa Prefecture, the southernmost prefecture of Japan. As of 1 June 2019, the city has an estimated population of 317,405 and a population density of 7,939 people per km2 (20,562 persons per sq. mi.). ...

, and a junk

Junk may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Junk'' (film), a 2000 Japanese horror film

* '' J-U-N-K'', a 1920 American film

* ''Junk'' (novel), by Melvin Burgess, 1996

* ''Junk'', a novel by Christopher Largen

* '' Junk: Record of the Last ...

), but no worthwhile targets, and ''Sailfish'' thereafter returned to Pearl Harbor.

Tenth patrol: November 1943 – January 1944

After refit at Pearl Harbor, she departed (under the command ofRobert E. McC. Ward

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' () "fame, glory, honour, praise, reno ...

) with a rejuvenated crew, on 17 November for her 10th patrol, which took her south of Honshū. Along the way, she suffered a " hot run" in tube eight (aft), and (after the skipper himself went over the side to inspect the damage) ejected the torpedo; the tube remained out of commission for the duration of the patrol.

After refueling at Midway, she was alerted by ULTRA of a fast convoy of Japanese ships before she arrived on station. Southeast of Yokosuka

is a city in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan.

, the city has a population of 373,797, and a population density of . The total area is . Yokosuka is the 11th-most populous city in the Greater Tokyo Area, and the 12th in the Kantō region. The city i ...

, on the night of 3 December, she made radar

Radar is a system that uses radio waves to determine the distance ('' ranging''), direction ( azimuth and elevation angles), and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It is a radiodetermination method used to detect and track ...

contact at . The group consisted of the Japanese aircraft carrier , a cruiser, and two destroyers. Despite high seas whipped up by typhoon

A typhoon is a tropical cyclone that develops between 180° and 100°E in the Northern Hemisphere and which produces sustained hurricane-force winds of at least . This region is referred to as the Northwestern Pacific Basin, accounting for a ...

winds, ''Sailfish'' maneuvered into firing position shortly after midnight on 3–4 December, dived to radar depth (just the radar aerial exposed), and fired four bow torpedoes at the carrier, at a range of , scoring two hits. She went deep to escape the escorting destroyers, which dropped 21 depth charges (only two close), reloaded, and at 02:00, surfaced to resume the pursuit. She found a mass of radar contacts, and a slow-moving target, impossible to identify in the miserable visibility. As dawn neared, she fired another spread of three bow "fish" from , scoring two more hits on the stricken carrier. Diving to elude the Japanese counterattack, which was hampered by the raging seas, ''Sailfish'' came to periscope depth, and at 07:58 saw the carrier lying dead in the water, listing to port and down by the stern. Preparations to abandon ship were in progress.

Later in the morning, ''Sailfish'' fired another spread of three torpedoes, from only , scoring two final hits. Loud internal explosions and breaking-up noises were heard while the submarine dived to escape a depth-charge attack. Abruptly, a cruiser appeared, and fearing that she would broach the surface, ''Sailfish'' went to , losing a chance at this new target. Shortly afterward, the carrier ''Chūyō'' () went to the bottom, the first aircraft carrier sunk by an American submarine in the war, and the only major Japanese warship sunk by enemy action in 1943. In an ironic twist, ''Chūyō'' was carrying American prisoners of war from , the same boat that had helped locate and rescue ''Sailfish''—then ''Squalus''—over four years before. Twenty of the 21 US crew members from ''Sculpin'' were killed. None, however, were of the original rescue crew; 1,250 Japanese were also killed.

After escaping a strafing attack by a Japanese fighter on 7 December, she made contact and commenced tracking two cargo ships with two escorts on the morning of 13 December, south of Kyūshū

is the third-largest island of Japan's four main islands and the most southerly of the four largest islands (i.e. excluding Okinawa and the other Ryukyu (''Nansei'') Islands). In the past, it has been known as , and . The historical regio ...

. That night, she fired a spread of four torpedoes at the two freighters. Two solid explosions were heard, including an internal secondary explosion. ''Sailfish'' heard ''Totai Maru'' () break up and sink as the destroyers made a vigorous but inaccurate depth-charge attack. When ''Sailfish'' caught up with the other freighter, she was dead in the water, but covered by a screen of five destroyers. Rather than face suicidal odds, the submarine quietly left the area. On the night of 20 December, she intercepted an enemy hospital ship, which she left unmolested.

On 21 December, in the approach to Bungo Suido

The is a strait separating the Japanese islands of Kyushu and Shikoku. It connects the Philippine Sea and the Seto Inland Sea on the western end of Shikoku. The narrowest part of this channel is the Hōyo Strait.

In the English-speaking world, ...

(Bungo Channel), ''Sailfish'' intercepted six large freighters escorted by three destroyers. With five torpedoes left, she fired a spread of three stern tubes, scoring two hits on the largest target. Diving to escape the approaching destroyers, the submarine detected breaking-up noises as ''Uyo Maru'' (6400 GRT) went to the bottom; destroyers counterattacked with 31 depth charges, "some very close". ''Sailfish'' terminated her tenth patrol at Pearl Harbor on 5 January 1944. She claimed three ships for 35,729 GRT, plus damage to one for 7000 tons, believed to be the most successful patrol by tonnage to date; postwar, it was reduced to two ships and (less ''Uyo Maru'') 29,571 tons.

Eleventh patrol: July–September 1944

After an extensive overhaul at Mare Island—from 15–17 June—she returned to Hawaii and sailed on 9 July as part of a " wolfpack" ("Moseley's Maulers", commanded by Stan Moseley), with and , to prey on shipping in the Luzon–Formosa area. On the afternoon of 6 August, ''Sailfish'' and ''Greenling'' made contact with an enemy convoy. ''Sailfish'' maneuvered into firing position and fired a spread of three torpedoes at a mine layer. One hit caused the tanker to disintegrate into a column of water, smoke, and debris. It was not recorded in the postwar account. In fact, the ''Sailfish'' had sunk the Japanese ''Kinshu Maru'' (238 GRT) in Luzon Strait in position 20°09'N, 121°19'E. Her next target was abattleship

A battleship is a large, heavily naval armour, armored warship with a main battery consisting of large naval gun, guns, designed to serve as a capital ship. From their advent in the late 1880s, battleships were among the largest and most form ...

escorted by three destroyers, on which she made radar contact shortly after midnight on 18–19 August. At 01:35, after getting as close as she was able, , ''Sailfish'' fired all four bow tubes. One of the escorts ran into the path of two fish; the other two missed. While the destroyer must have been severely damaged or sunk, there was nothing in JANAC.

On 24 August, south of Formosa, ''Sailfish'' made radar contact with an enemy convoy consisting of four cargo ships escorted by two small patrol craft. Moving into firing position, ''Sailfish'' fired a salvo of four torpedoes, scoring two hits. The cargo ship ''Toan Maru'' (2100 GRT) was enveloped in a cloud of smoke and shortly afterward broke in two and sank. Surfacing after escaping a depth-charge attack, ''Sailfish'' closed on a second cargo ship of the convoy, scoring two hits out of four torpedoes fired. The submarine's crew felt the cargo ship either had been sunk or badly damaged, but the sinking was not confirmed by JANAC postwar. ''Sailfish'' terminated her 11th patrol at Midway on 6 September; her wartime credit was four ships for 13,200 tons, a total reduced to just one of 2100 GRT (''Toan Maru'') postwar.

Twelfth patrol: September–December 1944

Her 12th patrol—from 26 September through 11 December—was conducted between Luzon and Formosa, in company with and . After passing through the edge of a typhoon, ''Sailfish'' arrived on station to performlifeguard

A lifeguard is a rescuer who supervises the safety and rescue of swimmers, surfers, and other water sports participants such as in a swimming pool, water park, beach, spa, river and lake. Lifeguards are trained in swimming and Cardiopulmonary ...

duty. On 12 October, staying surfaced in full view of enemy attackers, she rescued 12 Navy fliers who had ditched their stricken aircraft after strikes against Japanese bases on Formosa. She sank a ''sampan

A sampan is a relatively flat-bottomed wooden boat found in East, Southeast, and South Asia. It is possibly of Chinese or Austronesian origin. Some sampans include a small shelter on board and may be used as a permanent habitation on in ...

'' and a patrol craft with her deck gun as the enemy craft tried to capture the downed aviators. The following day, she rescued another flier. The submarines pulled into Saipan

Saipan () is the largest island and capital of the Northern Mariana Islands, an unincorporated Territories of the United States, territory of the United States in the western Pacific Ocean. According to 2020 estimates by the United States Cens ...

, arriving on 24 October, to drop off their temporary passengers, refuel, and make minor repairs.

After returning to the patrol area with the wolf pack, she made an unsuccessful attack on a transport on 3 November. The following day, ''Sailfish'' damaged the Japanese destroyer ''Harukaze'' and Japanese landing ship ''T-111'' (890 tons) in Luzon Strait in position 20°08'N, 121°43'E, but was slightly damaged herself by a bomb from a patrol aircraft. With battle damage under control, ''Sailfish'' eluded her pursuers and cleared the area. After riding out a typhoon on 9–10 November, she intercepted a convoy on the evening of 24 November heading for Itbayat

Itbayat, officially the Municipality of Itbayat, (; Ilocano: ''Ili ti Itbayat''; ), is a municipality in the province of Batanes, Philippines. In the 2020 census, it had a population of 3,128 people.

Itbayat is the country's northernmost muni ...

in the Philippines. After alerting ''Pomfret'' of the convoy's location and course, ''Sailfish'' was moving into an attack position, when one of the escorting destroyers headed straight for her. ''Sailfish'' fired a three-torpedo spread "down the throat" and headed toward the main convoy. At least one hit was scored on the destroyer and her pip faded from the radar screen. Suddenly, ''Sailfish'' received an unwelcome surprise when she came under fire from the destroyer that she had believed to be sunk. ''Sailfish'' ran deep after ascertaining no hull damage had resulted from a near miss from the escort's guns. For the next 4 hours, ''Sailfish'' was forced to run silent and deep as the Japanese kept up an uncomfortably accurate depth-charge attack. Finally, the submarine eluded the destroyers and slipped away. Shortly thereafter, ''Sailfish'' headed for Hawaii, via Midway, and completed her 12th and final war patrol upon arriving at Pearl Harbor on 11 December. ''Sailfish'' had damaged the IJN destroyer , which had previously sunk , and also a landing ship.

Return stateside

Following refit, ''Sailfish'' departed Hawaii on 26 December and arrived at New London, via the Panama Canal, on 22 January 1945. For the next four and one-half months, she aided training out of New London. Next, she operated as a training ship at Guantanamo Bay from 9 June–9 August. After a six-week stay atPhiladelphia Navy Yard

The Philadelphia Naval Shipyard was the first United States Navy shipyard and was historically important for nearly two centuries.

Construction of the original Philadelphia Naval Shipyard began during the American Revolution in 1776 at Front ...

, she arrived at Portsmouth, New Hampshire

Portsmouth is a city in Rockingham County, New Hampshire, Rockingham County, New Hampshire, United States. At the 2020 United States census, 2020 census it had a population of 21,956. A historic seaport and popular summer tourist destination on ...

, on 2 October for deactivation.

Post war

After being decommissioned on 27 October 1945, efforts by the city of Portsmouth and area residents to have the submarine kept intact as a memorial were not successful. Agreement was reached to have her

After being decommissioned on 27 October 1945, efforts by the city of Portsmouth and area residents to have the submarine kept intact as a memorial were not successful. Agreement was reached to have her conning tower

A conning tower is a raised platform on a ship or submarine, often armoured, from which an officer in charge can conn (nautical), conn (conduct or control) the vessel, controlling movements of the ship by giving orders to those responsible for t ...

saved, which was dedicated in November 1946 on Armistice Day

Armistice Day, later known as Remembrance Day in the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth and Veterans Day in the United States, is commemorated every year on 11 November to mark Armistice of 11 November 1918, the armistice signed between th ...

, by John L. Sullivan

John Lawrence Sullivan (October 15, 1858 – February 2, 1918), known simply as John L. among his admirers, and dubbed the "Boston Strong Boy" by the press, was an American boxer. He is recognized as the first heavyweight champion of gloved ...

, then Undersecretary of the Navy. The remainder of the submarine was initially scheduled to be a target in the atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear expl ...

tests or sunk by conventional ordnance. However, she was placed on sale in March 1948 and stricken from the Naval Vessel Register

The ''Naval Vessel Register'' (NVR) is the official inventory of ships and service craft in custody of or titled by the United States Navy. It contains information on ships and service craft that make up the official inventory of the Navy from t ...

on 30 April 1948. The hulk was sold for scrapping to Luria Brothers of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

, on 18 June 1948. Her conning tower still stands at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Kittery as a memorial to her lost crewmen ().

Honors and awards

*American Defense Service Medal

The American Defense Service Medal was a United States service medals of the World Wars, military award of the United States Armed Forces, established by , by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, on June 28, 1941.

The medal was intended to recogniz ...

*American Campaign Medal

The American Campaign Medal was a military award of the United States Armed Forces which was first created on November 6, 1942, by issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The medal was intended to recognize those military members who had per ...

* Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with nine battle star

A service star is a miniature bronze or silver five-pointed star in diameter that is authorized to be worn by members of the eight uniformed services of the United States on medals and ribbons to denote an additional award or service period. T ...

s for World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

service

*World War II Victory Medal

The World War II Victory Medal was a service medal of the United States military which was established by an Act of Congress on 6 July 1945 (Public Law 135, 79th Congress) and promulgated by Section V, War Department Bulletin 12, 1945.

Histo ...

In media

The 2001television movie

A television film, alternatively known as a television movie, made-for-TV film/movie, telefilm, telemovie or TV film/movie, is a film with a running time similar to a feature film that is produced and originally distributed by or to a Terrestr ...

docudrama

Docudrama (or documentary drama) is a genre of television show, television and feature film, film, which features Drama (film and television), dramatized Historical reenactment, re-enactments of actual events. It is described as a hybrid of docu ...

''Submerged'', directed by James Keach

James Keach (born December 7, 1947) is an American actor and filmmaker. He is the younger brother of actor Stacy Keach and son of actor Stacy Keach Sr.

Early life and education

James Peckham Keach was born in Savannah, Georgia, the son of M ...

and starring Sam Neill

Sir Nigel John Dermot "Sam" Neill (born 14 September 1947) is a New Zealand actor. His career has included leading roles in both dramas and blockbusters. Considered an "international leading man", he is regarded as one of the most versatile acto ...

as Charles B. "Swede" Momsen and James B. Sikking as Admiral Cyrus Cole, depicted the events surrounding the loss of USS ''Squalus'' and the rescue of her 33 survivors. The plot was written to closely follow the events of the sinking.

''Submerged'' used models and sets originally constructed for the 2000 film '' U-571''. The floating set used to in ''Submerged'' to represent both USS ''Squalus'' and USS ''Sculpin'' is the non-diving replica built in Malta

Malta, officially the Republic of Malta, is an island country in Southern Europe located in the Mediterranean Sea, between Sicily and North Africa. It consists of an archipelago south of Italy, east of Tunisia, and north of Libya. The two ...

as the "modified" for ''U-571'', which also was shot in Malta. The replica is still afloat, moored in Marsa in the inner part of the Grand Harbour

The Grand Harbour (; ), also known as the Port of Marsa, is a natural harbour on the island of Malta. It has been substantially modified over the years with extensive docks ( Malta Dockyard), wharves, and fortifications.

Description

The h ...

() at Malta.

In 2006, BBC TV presented a series of programs entitled ''Voyages of Discovery'', the first of which, called "Hanging by a Thread", told the story of the USS ''Squalus'' rescue mission, as narrated by Paul Rose./ref>

See also

* , a British World War II submarine that sank inLiverpool Bay

Liverpool Bay is a bay of the Irish Sea between northeast Wales, Cheshire, Lancashire and Merseyside to the east of the Irish Sea. The bay is a classic example of a region of freshwater influence. Liverpool Bay has historically suffered from redu ...

with the loss of 99 of 104 hands and was refloated and recommissioned under a new name.

Notes

Bibliography

* Barrows, Nathaniel A. ''Blow All Ballast! The Story of the Squalus.'' New York: Dodd, Mead & Co, 1940. * * * Gray, Edwyn. ''Disasters of the Deep: A Comprehensive Survey of Submarine Accidents and Disasters.'' Annapolis, Md: Naval Institute Press, 2003. * * (Television movie. The film does not acknowledge any design flaw and claims the cause is unknown.) * LaVO, Carl. ''Back from the Deep: The Strange Story of the Sister Subs Squalus and Sculpin.'' Annapolis, Md: Naval Institute Press, 1994. * Maas, Peter. ''The Rescuer.'' New York: Harper & Row, 1967. * * USS ''Squalus'', Ship Source Files, Ships History Branch, Naval Historical Center * "Oliver Francis Naquin," Obituary, ''The New York Times'', 15 November. 1989 * ''Department's Report on "Squalus" Disaster''. Washington: U.S. G.P.O., 1939. * Naval Historical Center (U.S.).'' USS Squalus (SS-192) The Sinking, Rescue of Survivors, and Subsequent Salvage, 1939.'' Washington, D.C.: Naval Historical Center, 1998. http://www.history.navy.mil/faqs/faq99-1.htm * Mariners' Museum (Newport News, Va.). ''Salvage of the Squalus: Clippings from Newspapers, 25 May 20 January 1939, 1941''. Newport News, Va: Mariners' Museum, 1942. * Portsmouth Naval Shipyard (U.S.). ''Technical Report of the Salvage of U.S.S. Squalus.'' Portsmouth, N.H.: U.S. Navy Yard, 1939. * Falcon (Salvage ship), and Albert R. Behnke. ''Log of Diving During Rescue and Salvage Operations of the USS Squalus: Diving Log of USS Falcon'', 24 May 1939 – 12 September 1939. Kensington, Maryland: Reprinted by Undersea & Hyperbaric Medical Society, 2001 * ''Diving in the U.S. Navy a brief history.'' http://purl.access.gpo.gov/GPO/LPS88384References

* *Further reading

*External links

Naval Historical Center, Online Library of Selected Images: USS ''Squalus''/''Sailfish'' (SS-192)

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Sailfish (Ss-192) 1938 ships Maritime incidents in 1939 Sargo-class submarines Ships built in Kittery, Maine United States submarine accidents World War II submarines of the United States