UK Trident programme on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Trident, also known as the Trident nuclear programme or Trident nuclear deterrent, covers the development, procurement and operation of nuclear weapons in the United Kingdom and their means of delivery. Its purpose as stated by the

During the 1950s, Britain's nuclear deterrent was based around the V-bombers of the

During the 1950s, Britain's nuclear deterrent was based around the V-bombers of the

The

The  The law could be waived if the President determined that it was in the interest of the US to do so, but for that the Carter administration wanted undertakings that the UK would raise defence spending by the same amount, or pay the cost of US forces manning

The law could be waived if the President determined that it was in the interest of the US to do so, but for that the Carter administration wanted undertakings that the UK would raise defence spending by the same amount, or pay the cost of US forces manning

Four ''Vanguard''-class submarines were designed and built at Barrow-in-Furness by Vickers Shipbuilding and Engineering, now

Four ''Vanguard''-class submarines were designed and built at Barrow-in-Furness by Vickers Shipbuilding and Engineering, now

In British service, Trident II missiles are fitted with a thermonuclear warhead called Holbrook. The warhead has a choice of two warhead yields the highest of which is thought to be , with a lower yield in the range of . The UK government was sensitive to charges that the replacement of Polaris with Trident would involve an escalation in the numbers of British nuclear weapons. When the decision to purchase Trident II was announced in 1982, it was stressed that while American Trident boats carried 24 missiles with eight warheads each, a total of 192 warheads, British Trident boats would carry no more than 128 warheads—the same number as Polaris. In November 1993, the Secretary of State for Defence,

In British service, Trident II missiles are fitted with a thermonuclear warhead called Holbrook. The warhead has a choice of two warhead yields the highest of which is thought to be , with a lower yield in the range of . The UK government was sensitive to charges that the replacement of Polaris with Trident would involve an escalation in the numbers of British nuclear weapons. When the decision to purchase Trident II was announced in 1982, it was stressed that while American Trident boats carried 24 missiles with eight warheads each, a total of 192 warheads, British Trident boats would carry no more than 128 warheads—the same number as Polaris. In November 1993, the Secretary of State for Defence,

Trident II D-5 is a submarine-launched ballistic missile built by

Trident II D-5 is a submarine-launched ballistic missile built by

Ministry of Defence

A ministry of defence or defense (see American and British English spelling differences#-ce.2C -se, spelling differences), also known as a department of defence or defense, is the part of a government responsible for matters of defence and Mi ...

is to "deter the most extreme threats to our national security and way of life, which cannot be done by other means". Trident is an operational system of four s armed with Trident II D-5 ballistic missiles, able to deliver thermonuclear warheads from multiple independently targetable re-entry vehicles (MIRVs). It is operated by the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

and based at Clyde Naval Base on the west coast of Scotland. At least one submarine is always on patrol to provide a continuous at-sea capability. The missiles are manufactured in the United States, while the warheads are British.

The British government initially negotiated with the Carter administration

Jimmy Carter's tenure as the List of presidents of the United States, 39th president of the United States began with Inauguration of Jimmy Carter, his inauguration on January 20, 1977, and ended on January 20, 1981. Carter, a Democratic Party ...

for the purchase of the Trident I C-4 missile. In 1981, the Reagan administration

Ronald Reagan's tenure as the 40th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 1981, and ended on January 20, 1989. Reagan, a Republican from California, took office following his landslide victory over ...

announced its decision to upgrade its Trident to the new Trident II D-5 missile. This necessitated another round of negotiations and concessions. The UK Trident programme was announced in July 1980 and patrols began in December 1994. Trident replaced the submarine-based Polaris

Polaris is a star in the northern circumpolar constellation of Ursa Minor. It is designated α Ursae Minoris (Latinisation of names, Latinized to ''Alpha Ursae Minoris'') and is commonly called the North Star or Pole Star. With an ...

system, in operation from 1968 until 1996. Trident is the only nuclear weapon system operated by the UK since the decommissioning of tactical WE.177 free-fall bombs in 1998.

NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

's military posture was relaxed after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Trident warheads have never been aimed at specific targets on an operational patrol, but await co-ordinates that can be programmed into their computers and fired with several days' notice. Although Trident was designed as a strategic deterrent, the end of the Cold War led the British government to conclude that a sub-strategic—but not tactical—role was required.

A programme for the replacement of the ''Vanguard'' class is under way. On 18 July 2016, the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

voted by a large majority to proceed with building a fleet of s, to be operational by 2028, with the current fleet completely phased out by 2032.

Background

During the early part of theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, the United Kingdom (UK) had a nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear exp ...

s project, code-named Tube Alloys

Tube Alloys was the research and development programme authorised by the United Kingdom, with participation from Canada, to develop nuclear weapons during the Second World War. Starting before the Manhattan Project in the United States, the Bri ...

, which the 1943 Quebec Agreement merged with the American Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

to create a combined American, British, and Canadian project. The British government expected that the United States (US) would continue to share nuclear technology, which it regarded as a joint discovery, but the United States Atomic Energy Act of 1946 (McMahon Act) ended technical co-operation. Fearing a resurgence of US isolationism, and losing its own great power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power ...

status, the British government resumed its own development effort. The first British atomic bomb was tested in Operation Hurricane on 3 October 1952. The subsequent British development of the hydrogen bomb, and a fortuitous international relations climate created by the Sputnik crisis

The Sputnik crisis was a period of public fear and anxiety in Western nations about the perceived technological gap between the United States and Soviet Union caused by the Soviets' launch of '' Sputnik 1'', the world's first artificial sate ...

, facilitated the amendment of the McMahon Act, and the 1958 US–UK Mutual Defence Agreement

Events

January

* January 1 – The European Economic Community (EEC) comes into being.

* January 3 – The West Indies Federation is formed.

* January 4

** Edmund Hillary's Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition completes the thir ...

(MDA), which allowed Britain to acquire nuclear weapons systems from the US, thereby restoring the nuclear Special Relationship.

Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

(RAF), but developments in radar

Radar is a system that uses radio waves to determine the distance ('' ranging''), direction ( azimuth and elevation angles), and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It is a radiodetermination method used to detect and track ...

and surface-to-air missiles

A surface-to-air missile (SAM), also known as a ground-to-air missile (GTAM) or surface-to-air guided weapon (SAGW), is a missile designed to be launched from the ground or the sea to destroy aircraft or other missiles. It is one type of anti-a ...

made it clear that bombers

A bomber is a military combat aircraft that utilizes

air-to-ground weaponry to drop bombs, launch torpedoes, or deploy air-launched cruise missiles.

There are two major classifications of bomber: strategic and tactical. Strategic bombing is ...

were becoming increasingly vulnerable, and would be unlikely to penetrate Soviet airspace by the mid-1970s. To address this problem, the UK embarked on the development of a Medium Range Ballistic Missile

A medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM) is a type of ballistic missile with medium range (aeronautics), range, this last classification depending on the standards of certain organizations. Within the United States Department of Defense, U.S. D ...

called Blue Streak, but concerns were raised about its own vulnerability, and the British government decided to cancel it and acquire the American Skybolt air-launched ballistic missile. In return, the Americans were given permission to base the US Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

's Polaris

Polaris is a star in the northern circumpolar constellation of Ursa Minor. It is designated α Ursae Minoris (Latinisation of names, Latinized to ''Alpha Ursae Minoris'') and is commonly called the North Star or Pole Star. With an ...

boats at Holy Loch

The Holy Loch () is a sea loch, part of the Firth of Clyde, in Argyll and Bute, Scotland.

The "Holy Loch" name is believed to date from the 6th century, when Saint Munn landed there after leaving Ireland. Kilmun Parish Church and Argyll Mausole ...

in Scotland. In November 1962, the American government cancelled Skybolt. John F. Kennedy, then President of the United States, and Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton (10 February 1894 – 29 December 1986), was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. Nickn ...

, then UK Prime Minister, negotiated the Nassau Agreement, under which the US would sell Polaris systems for UK-built submarines. This was formalised in the Polaris Sales Agreement.

The first British Polaris ballistic missile submarine (SSBN), , was laid down by Vickers-Armstrongs

Vickers-Armstrongs Limited was a British engineering conglomerate formed by the merger of the assets of Vickers Limited and Sir W G Armstrong Whitworth & Company in 1927. The majority of the company was nationalised in the 1960s and 1970s, w ...

at its yard at Barrow-in-Furness

Barrow-in-Furness is a port town and civil parish (as just "Barrow") in the Westmorland and Furness district of Cumbria, England. Historic counties of England, Historically in the county of Lancashire, it was incorporated as a municipal borou ...

in Cumbria on 26 February 1964. She was launched on 15 September 1965, commissioned on 2 October 1967, and conducted a test firing at the American Eastern Range

The Eastern Range (ER) is an American rocket range (Spaceport) that supports missile and rocket launches from the two major List of rocket launch sites, launch heads located at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station and the Kennedy Space Center ( ...

on 15 February 1968. She was followed by , which was completed by Vickers-Armstrongs on 29 September 1968; and two boats built by Cammell Laird

Cammell Laird is a British shipbuilding company. It was formed from the merger of Laird Brothers of Birkenhead and Johnson Cammell & Co of Sheffield at the turn of the twentieth century. The company also built railway rolling stock until 1929, ...

in Birkenhead

Birkenhead () is a town in the Metropolitan Borough of Wirral, Merseyside, England. The town is on the Wirral Peninsula, along the west bank of the River Mersey, opposite Liverpool. It lies within the Historic counties of England, historic co ...

: , which was completed on 15 November 1968; and , which was completed on 4 December 1969. The four boats were based at HMNB Clyde

His Majesty's Naval Base, Clyde (HMNB Clyde; also HMS ''Neptune''), primarily sited at Faslane on the Gare Loch, is one of three operating bases in the United Kingdom for the Royal Navy (the others being HMNB Devonport and HMNB Portsmouth). It ...

at Faslane

His Majesty's Naval Base, Clyde (HMNB Clyde; also HMS ''Neptune''), primarily sited at Faslane on the Gare Loch, is one of three operating bases in the United Kingdom for the Royal Navy (the others being HMNB Devonport and HMNB Portsmouth). It ...

on the Firth of Clyde

The Firth of Clyde, is the estuary of the River Clyde, on the west coast of Scotland. The Firth has some of the deepest coastal waters of the British Isles. The Firth is sheltered from the Atlantic Ocean by the Kintyre, Kintyre Peninsula. The ...

, not far from the US Navy's base at Holy Loch, which opened in August 1968. It was served by a weapons store at nearby RNAD Coulport. HM Dockyard, Rosyth, was designated as the refit yard for the 10th Submarine Squadron, as the Polaris boats became operational.

Polaris proved to be reliable, and its second-strike capability

In nuclear strategy, a retaliatory strike or second-strike capability is a country's assured ability to respond to a nuclear attack with powerful nuclear retaliation against the attacker. To have such an ability (and to convince an opponent of its ...

conferred greater strategic flexibility than any previous British nuclear weapons system. However it had a limited lifespan, and was expected to become obsolete by the 1990s. It was considered vital that an independent British deterrent could penetrate existing and future Soviet anti-ballistic missile

An anti-ballistic missile (ABM) is a surface-to-air missile designed to Missile defense, destroy in-flight ballistic missiles. They achieve this explosively (chemical or nuclear), or via hit-to-kill Kinetic projectile, kinetic vehicles, which ma ...

(ABM) capabilities. An ABM system, the ABM-1 Galosh, defended Moscow, and NATO believed the USSR would continue to develop its effectiveness. The deterrent logic required the ability to threaten the destruction of the Soviet capital and other major cities. To ensure that a credible and independent nuclear deterrent was maintained, the UK developed an improved warhead package Chevaline

Chevaline () was a system to improve the penetrability of the warheads used by the UK Polaris programme, British Polaris nuclear weapons system. Devised as an answer to the improved Soviet Union, Soviet A-35 anti-ballistic missile system, anti-b ...

, which replaced one of the three warheads in a Polaris missile with multiple decoys, chaff

Chaff (; ) is dry, scale-like plant material such as the protective seed casings of cereal grains, the scale-like parts of flowers, or finely chopped straw. Chaff cannot be digested by humans, but it may be fed to livestock, ploughed into soil ...

, and other defensive countermeasure

A countermeasure is a measure or action taken to counter or offset another one. As a general concept, it implies precision and is any technological or tactical solution or system designed to prevent an undesirable outcome in the process. The fi ...

s. Chevaline was extremely expensive; it encountered many of the same issues that had affected the British nuclear weapons projects of the 1950s, and postponed, but did not avert, Polaris's obsolescence.

The Conservative Party had a strong pro-defence stance, and supported the British nuclear weapons programme, although not necessarily at the expense of conventional weapons. The rival Labour Party had initiated the acquisition of nuclear weapons, but in the late 1950s its left wing pushed for a policy of nuclear disarmament, resulting in an ambiguous stance. While in office from 1964 to 1970 and 1974 to 1979, it built and maintained Polaris, and modernised it through the secret Chevaline programme. In opposition in the early 1980s, Labour adopted a policy of unilateral nuclear disarmament.

More important than political differences was a shared sense of British national identity. Britain was seen as an important player in world affairs, its economic and military weaknesses offset by its membership of NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

and the Group of Seven

The Group of Seven (G7) is an Intergovernmentalism, intergovernmental political and economic forum consisting of Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States; additionally, the European Union (EU) is a "non- ...

, its then active membership of the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are Geography of the European Union, located primarily in Europe. The u ...

, its permanent seat on the UN Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, an ...

, its leadership of the Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, often referred to as the British Commonwealth or simply the Commonwealth, is an International organization, international association of member states of the Commonwealth of Nations, 56 member states, the vast majo ...

, and the nuclear Special Relationship with the US. To accept a position of inferiority to its ancient rival, France, was unthinkable. Moreover, the UK sees itself as a force for good in the world with a moral duty to intervene, with military force if need be, to defend both its interests and its values. By the 1980s, possession of nuclear weapons was considered a visible sign of Britain's enduring status as a great power in spite of the loss of the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

, and had become a component of the national self-image.

Negotiations

The

The Cabinet Secretary

A cabinet secretary is usually a senior official (typically a civil servant) who provides services and advice to a cabinet of ministers as part of the Cabinet Office. In many countries, the position can have considerably wider functions and powe ...

, Sir John Hunt briefed Cabinet on Polaris on 28 November 1977, noting that a possible successor might take up to 15 years to bring into service, depending on the nature of system chosen, and whether it was to be developed by the UK, or in collaboration with France or the US. With the recent experience of Chevaline in mind, the option of a purely British project was rejected. A study of the options was commissioned in February 1978 from a group chaired by the Deputy Under-Secretary of State at the Foreign Office

Foreign may refer to:

Government

* Foreign policy, how a country interacts with other countries

* Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in many countries

** Foreign Office, a department of the UK government

** Foreign office and foreign minister

* United ...

, Sir Antony Duff, with the Chief Scientific Adviser to the Ministry of Defence

A ministry of defence or defense (see American and British English spelling differences#-ce.2C -se, spelling differences), also known as a department of defence or defense, is the part of a government responsible for matters of defence and Mi ...

, Sir Ronald Mason. The Duff-Mason Report was delivered to the Prime Minister, James Callaghan

Leonard James Callaghan, Baron Callaghan of Cardiff ( ; 27 March 191226 March 2005) was a British statesman and Labour Party (UK), Labour Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1976 to 1979 and Leader of the L ...

, in parts on 11 and 15 December. It recommended the purchase of the American Trident I C-4 missile then in service with the US Navy. The C-4 had multiple independently targetable re-entry vehicle (MIRV) capability, which was needed to overcome the Soviet ABM defences.

Callaghan approached President Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (October 1, 1924December 29, 2024) was an American politician and humanitarian who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party ...

in January 1979, who responded positively, but did not commit. The Carter administration's main priority was the SALT II Agreement with the Soviet Union, which limited nuclear weapons stockpiles. It was signed on 18 June 1979, but Carter faced an uphill battle to secure its ratification

Ratification is a principal's legal confirmation of an act of its agent. In international law, ratification is the process by which a state declares its consent to be bound to a treaty. In the case of bilateral treaties, ratification is usuall ...

by the US Senate

The United States Senate is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and House have the authority under Article One of the ...

. MIRV technology had proved to be a major loophole in the 1972 SALT I Agreement, which limited numbers of missiles but not warheads. During the SALT II negotiations the US had resisted Soviet proposals to include the British and French nuclear forces in the agreement, but there were concerns that supplying MIRV technology to the UK would be seen by the Soviets as violating the spirit of the non-circumvention clause in SALT II.

Callaghan was succeeded by Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013), was a British stateswoman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of th ...

after the general election

A general election is an electoral process to choose most or all members of a governing body at the same time. They are distinct from By-election, by-elections, which fill individual seats that have become vacant between general elections. Gener ...

on 3 May 1979, and she discussed the issue with Carter in October, who agreed to supply C-4, but he asked that the UK delay a formal request until December in order that he could get SALT II ratified beforehand. In the meantime, the MDA, without which the UK would not be able to access US nuclear weapons technology, was renewed for five more years on 5 December, and the MISC 7 cabinet committee formally approved the decision to purchase C-4 the following day. When Thatcher met with Carter again on 17 December, he still asked for more time, but the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until it dissolved in 1991. During its existence, it was the largest country by are ...

on 24 December ended all hope of Senate ratification of SALT II, clearing the way for the sale to proceed.

The British government hoped that Trident could be secured on the same terms as Polaris, but when its chief negotiator, Robert Wade-Gery

Sir Robert Wade-Gery (22 April 1929 – 16 February 2015) was a British diplomat who was High Commissioner to India 1982–87.

Biography

Wade-Gery was born in Oxford on 22 April 1929. His father, Theodore Wade-Gery was an ancient historian and ...

, sat down with his American counterpart, David L. Aaron, in March 1980, he found this was not the case. Instead of the 5 per cent levy in recognition of US research and development (R&D) costs agreed to in the Polaris Sales Agreement, a 1976 law now required a ''pro rata'' fixed fee payment; the levy would have been approximately $100 million, however the fixed fee amounted to around $400 million.

The law could be waived if the President determined that it was in the interest of the US to do so, but for that the Carter administration wanted undertakings that the UK would raise defence spending by the same amount, or pay the cost of US forces manning

The law could be waived if the President determined that it was in the interest of the US to do so, but for that the Carter administration wanted undertakings that the UK would raise defence spending by the same amount, or pay the cost of US forces manning Rapier

A rapier () is a type of sword originally used in Spain (known as ' -) and Italy (known as '' spada da lato a striscia''). The name designates a sword with a straight, slender and sharply pointed two-edged long blade wielded in one hand. It wa ...

batteries and Ground Launched Cruise Missile (GLCM) sites in the UK. On 2 June 1980, Thatcher and the US Secretary of Defense, Harold Brown, agreed to $2.5 billion for the C-4 missile system, plus a 5 per cent R&D levy, British personnel for the Rapier batteries, and an expansion of the US base on Diego Garcia

Diego Garcia is the largest island of the Chagos Archipelago. It has been used as a joint UK–U.S. military base since the 1970s, following the expulsion of the Chagossians by the UK government. The Chagos Islands are set to become a former B ...

, which had assumed great importance since the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. The Secretary of State for Defence

The secretary of state for defence, also known as the defence secretary, is a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, with responsibility for the Ministry of Defence. As a senior minister, the incumbent is a member of the ...

, Francis Pym

Francis Leslie Pym, Baron Pym, (13 February 1922 – 7 March 2008) was a British Conservative Party politician who served in various Cabinet positions in the 1970s and 1980s, including Foreign, Defence and Northern Ireland Secretary, and ...

, informed Cabinet of the decision to purchase Trident on 15 July 1980, and announced it in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

later that day. The agreement was effected by amending the Polaris Sales Agreement, changing "Polaris" to "Trident".

However, on 4 November 1980, Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

was elected president. Part of his election platform was to modernise the US strategic nuclear forces. On 24 August 1981, the Reagan administration informed the British government of its intention to upgrade its Trident to the new Trident II D-5 missile by 1989, and indicated that it was willing to sell it to the UK. Despite the name, the D-5 was not an improved version of the C-4, but a completely new missile. Its purchase had already been considered in the Duff-Mason report, but had been rejected, as its additional capability—the extended range from —was not required by the UK, and it was more expensive. Exactly how much more expensive was uncertain, as it was still under development. At the same time, the British government was well aware of the costs of not having the same hardware as the US. Nor did the Reagan administration promise to sell D-5 on the same terms as the C-4. To pay for Trident, the British government announced deep cuts to other defence spending on 25 June 1981.

Negotiations commenced on 8 February, with the British team again led by Wade-Gery. The Americans were disturbed at the proposed British defence cuts, and pressed for an undertaking that the aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and hangar facilities for supporting, arming, deploying and recovering carrier-based aircraft, shipborne aircraft. Typically it is the ...

be retained in service, which they felt was necessary to avert trouble over the Belizean–Guatemalan territorial dispute. They accepted a counter-offer that Britain would retain the two landing platform dock

An amphibious transport dock, also called a landing platform dock (LPD), is an amphibious warfare ship, a warship that embarks, transports, and lands elements of a landing force for expeditionary warfare missions. Several navies currently operat ...

ships, and , for which the Americans reduced the R&D charge. Under the agreement, the UK would purchase 65 Trident II D-5 missiles that would operate as part of a shared pool of weapons based at Naval Submarine Base Kings Bay in the US. The US would maintain and support the missiles, while the UK would manufacture its own submarines and warheads to go on the missiles. The warheads and missiles would be mated in the UK. This was projected to save about £500 million over eight years at Coulport, while the Americans spent $70 million upgrading the facilities at Kings Bay. The sale agreement was formally signed on 19 October 1982 by the British Ambassador to the United States, Sir Oliver Wright, and the US Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state (SecState) is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State.

The secretary of state serves as the principal advisor to the p ...

, George Shultz

George Pratt Shultz ( ; December 13, 1920February 6, 2021) was an American economist, businessman, diplomat and statesman. He served in various positions under two different Republican presidents and is one of the only two persons to have held f ...

.

The Trident programme was projected to cost £5 billion, including the four submarines, the missiles, new facilities at Coulport and Faslane and the contribution to Trident II D-5 R&D. It was expected to absorb 5 per cent of the defence budget. As with Polaris, the option for a fifth submarine (allowing two to be on patrol at all times) was discussed, but ultimately rejected. Thatcher's popularity soared as a result of the British victory in the Falklands War

The Falklands War () was a ten-week undeclared war between Argentina and the United Kingdom in 1982 over two British Overseas Territories, British dependent territories in the South Atlantic: the Falkland Islands and Falkland Islands Dependenci ...

, in which the ships that the Americans had insisted be retained played a crucial part. Trident's future was secured the following year when the Conservative Party won the 1983 general election, defeating a Labour Party that had pledged to cancel Trident. The first Trident boat, was ordered on 30 April 1986. In view of the Labour Party's continued opposition to Trident, Vickers

Vickers was a British engineering company that existed from 1828 until 1999. It was formed in Sheffield as a steel foundry by Edward Vickers and his father-in-law, and soon became famous for casting church bells. The company went public in 18 ...

insisted that the contract include substantial compensation in the event of cancellation.

UK's Nuclear Policies

Cold War

The Trident programme was initiated during theCold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

, and it was designed to provide an ongoing independently controlled deterrent against major threats to the security of the UK and its NATO allies, including threats posed by non-nuclear weapons.

To provide an effective deterrent, the Trident system was intended to "pose a potential threat to key aspects of Soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

state power" whilst being invulnerable to a surprise or pre-emptive nuclear strike

In nuclear strategy, a first strike or preemptive strike is a preemptive surprise attack employing overwhelming force. First strike capability is a country's ability to defeat another nuclear power by destroying its arsenal to the point where th ...

. As with Polaris, Trident was owned and operated by the UK but committed to NATO and targeted in accordance with plans set out by the organisation's Supreme Allied Commander Europe

The Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR) is the commander of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization's (NATO) Allied Command Operations (ACO) and head of ACO's headquarters, Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE). The commander is ...

, who is traditionally a senior figure in the US military. Under the terms of the Polaris Sales Arrangement, the US does not have a veto on the use of British nuclear weapons, which the UK may launch independently, but this would only occur if "supreme national interests" required it.

The final decision on firing the missiles is the responsibility of the prime minister, who, upon taking office, writes four identical letters of last resort, one of which is locked in a safe on board each of the ''Vanguard''-class submarines. If contact with the UK is lost, the commanding officer of a submarine has to follow the instructions in the letter if they believe that the United Kingdom has suffered an overwhelming attack. Options include retaliating with nuclear weapons, not retaliating, putting the submarine under the command of an ally, or acting as the captain deems appropriate. The exact content of the letters is never disclosed, and they are destroyed without being opened upon a new prime minister taking office.

Post-Cold War

By the time of the first ''Vanguard'' patrol in December 1994, the Soviet Union no longer existed, and the government adjusted its nuclear policy in the following years. Trident's missiles were "detargetted" in 1994 ahead of ''Vanguard''s maiden voyage. The warheads are not aimed at specific targets but await co-ordinates that can be programmed into their computers and fired with several days' notice. Under the terms of the 1987Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty

The Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF Treaty) was an arms control treaty between the United States and the Soviet Union (and its successor state, the Russia, Russian Federation). President of the United States, US President Ronald Rea ...

with the Soviet Union, the US withdrew its surface naval nuclear weapons and short-range nuclear forces. The GLCMs were withdrawn from the UK in 1991, and the Polaris submarine base at Holy Loch was closed in 1992. The last US warheads in British service under Project E, the B57 nuclear depth bombs and the Lance missiles and W48 nuclear artillery shells used by the British Army of the Rhine

British Army of the Rhine (BAOR) was the name given to British Army occupation forces in the Rhineland, West Germany, after the First and Second World Wars, and during the Cold War, becoming part of NATO's Northern Army Group (NORTHAG) tasked ...

, were withdrawn in July 1992. The British Conservative government followed suit. The deployment of ships carrying nuclear weapons caused embarrassment during the Falklands War, and in the aftermath it was decided to stockpile them ashore in peacetime. The nuclear depth bombs were withdrawn from service in 1992, followed by the WE.177 free-fall bombs used by the Royal Navy and RAF on 31 March 1998. This left Trident as Britain's sole nuclear weapons system.

Although Trident was designed as a strategic deterrent, the end of the Cold War led the British government to conclude that a sub-strategic—but not tactical—role was required, with Trident missiles assuming the role formerly handled by the RAF's WE.177 bombs. The 1994 Defence White Paper stated: "We also need the capability to undertake nuclear action on a more limited scale in order to ... halt aggression without inevitably triggering strategic nuclear exchanges". A later statement read: "We also intend to exploit the flexibility of Trident to provide the vehicle for both sub-strategic and strategic elements of our deterrent … as an insurance against potential adverse trends in the international situation". On 19 March 1998, the Defence Secretary, George Robertson, was asked to provide a statement "on the development of a lower-yield variant of the Trident warhead for the sub-strategic role". He replied, "the UK has some flexibility in the choice of yield for the warheads on its Trident missiles".

The UK has not declared a no first use

In nuclear ethics and deterrence theory, no first use (NFU) refers to a type of pledge or policy wherein a nuclear power formally refrains from the use of nuclear weapons or other weapons of mass destruction (WMD) in warfare, except for as a se ...

policy regarding launching a nuclear attack; former British defence secretary Geoff Hoon

Geoffrey William Hoon (born 6 December 1953) is a British Labour Party politician who served as the Member of Parliament (MP) for Ashfield in Nottinghamshire from 1992 to 2010. He is a former Defence Secretary, Transport Secretary, Leader ...

stated in 2002 and 2003 that the UK would be willing to attack rogue states with them if nuclear weapons were used against British troops. In April 2017 Defence Secretary Michael Fallon

Sir Michael Cathel Fallon (born 14 May 1952) is a British politician who served as Secretary of State for Defence from 2014 to 2017. A member of the Conservative Party (UK), Conservative Party, he served as Member of Parliament (United Kingdom ...

confirmed that the UK would use nuclear weapons in a " pre-emptive initial strike" in "the most extreme circumstances". Fallon stated in a parliamentary answer that the UK has neither a 'first use' or 'no first use' in its nuclear weapon policy so that its adversaries would not know when the UK would launch nuclear strikes.

In March 2021, the UK suggested a shift in nuclear policy in its Integrated Defence Review, stating that the UK would reserve the right to use nuclear weapons in the face of weapons of mass destruction

A weapon of mass destruction (WMD) is a Biological agent, biological, chemical weapon, chemical, Radiological weapon, radiological, nuclear weapon, nuclear, or any other weapon that can kill or significantly harm many people or cause great dam ...

, which includes "emerging technologies that could have a considerable impact", including cyber technologies, to chemical or biological weapons. This marks a shift from existing UK policy, in that nuclear weapons would only be launched against another nuclear power or in response to extreme chemical or biological threats. It did, however, stress that the UK would not use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against any non-nuclear weapon party to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons 1968, but only if the state is not in "material breach" of the Treaty's obligations. The shift in language comes after the UK lifted the cap on the number of Trident

A trident (), () is a three- pronged spear. It is used for spear fishing and historically as a polearm. As compared to an ordinary spear, the three tines increase the chance that a fish will be struck and decrease the chance that a fish will b ...

nuclear warheads it can stockpile by 40% from 180 to 260 warheads "in recognition of the evolving security environment". The UK has also stated it would no longer declare how many deployable warheads under a new policy of deliberate ambiguity. The move is intended to cement the UK's status as a nuclear power and a US defence ally. Labour Party Leader Keir Starmer

Sir Keir Rodney Starmer (born 2 September 1962) is a British politician and lawyer who has served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom since 2024 and as Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party since 2020. He previously ...

, although supporting nuclear deterrence, criticised the new policy and questioned why Prime Minister Boris Johnson

Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson (born 19 June 1964) is a British politician and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 2019 to 2022. He wa ...

believed that increasing the stockpile was necessary. Kate Hudson

Kate Garry Hudson (born April 19, 1979) is an American actress and singer. Born to singer Bill Hudson (singer), Bill Hudson and actress Goldie Hawn, Hudson made her film debut in the 1998 drama ''Desert Blue'', which was followed by supporting ...

of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament

The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) is an organisation that advocates unilateral nuclear disarmament by the United Kingdom, international nuclear disarmament and tighter international arms regulation through agreements such as the Nucl ...

warned against the start of a "new nuclear arms race".

Design, development and construction

''Vanguard''-class submarines

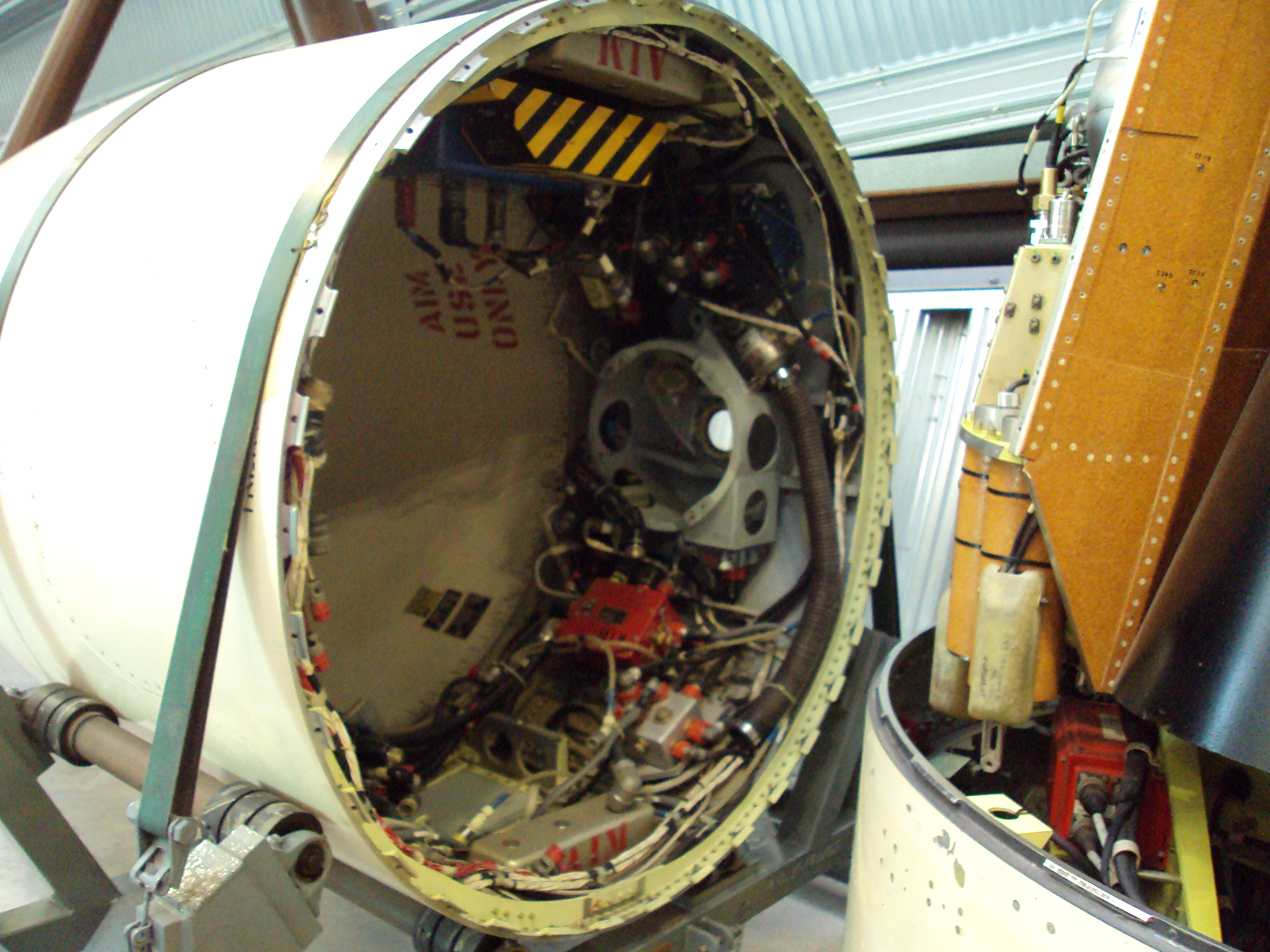

Four ''Vanguard''-class submarines were designed and built at Barrow-in-Furness by Vickers Shipbuilding and Engineering, now

Four ''Vanguard''-class submarines were designed and built at Barrow-in-Furness by Vickers Shipbuilding and Engineering, now BAE Systems Submarines

BAE Systems Submarines,BAE Systems Submarine Solutions was split out from BAE Systems Marine and operated as such until January 2012. It was named BAE Systems Maritime - Submarines until 2017 before it became BAE Systems Submarines. is a whol ...

, the only shipbuilder in the UK with the facilities and expertise to build nuclear submarines. Even so, £62 million worth of new shipbuilding and dock facilities were added for the project, with the Devonshire Dock Hall built specially for it. The initial plan was to build new versions of the ''Resolution''-class, but in July 1981 the decision was taken to incorporate the new Rolls-Royce

Rolls-Royce (always hyphenated) may refer to:

* Rolls-Royce Limited, a British manufacturer of cars and later aero engines, founded in 1906, now defunct

Automobiles

* Rolls-Royce Motor Cars, the current car manufacturing company incorporated in ...

PWR2 pressurised water reactor

A pressurized water reactor (PWR) is a type of light-water nuclear reactor. PWRs constitute the large majority of the world's nuclear power plants (with notable exceptions being the UK, Japan, India and Canada).

In a PWR, water is used both as ...

. From the outset, the ''Vanguard'' submarines were designed with enlarged missile tubes able to accommodate the Trident II D-5. The missile compartment is based on the system used on the American , although with capacity for only 16 missiles, rather than the 24 on board an ''Ohio'' boat. The boats are significantly larger than the ''Resolution'' class, and were given names formerly associated with battleship

A battleship is a large, heavily naval armour, armored warship with a main battery consisting of large naval gun, guns, designed to serve as a capital ship. From their advent in the late 1880s, battleships were among the largest and most form ...

s and aircraft carriers, befitting their status as capital ship

The capital ships of a navy are its most important warships; they are generally the larger ships when compared to other warships in their respective fleet. A capital ship is generally a leading or a primary ship in a naval fleet.

Strategic i ...

s. An important consideration was the depth of the Walney Channel, which connected Barrow to the Irish Sea

The Irish Sea is a body of water that separates the islands of Ireland and Great Britain. It is linked to the Celtic Sea in the south by St George's Channel and to the Inner Seas off the West Coast of Scotland in the north by the North Ch ...

, which limited the draft

Draft, the draft, or draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a v ...

to , while the ''Ohio''-class boats had a draft of . Each boat is long and in diameter, and carries a crew of 150 officers and ratings.

The submarines use a tactical-information and weapons-control system called the Submarine Command System Next Generation

SMCS, the Submarine Command System, was first created for the Royal Navy, Royal Navy of the United Kingdom's s as a tactical information system and a torpedo weapon control system. Versions have now also been installed on all active Royal Navy subm ...

. This system was developed in collaboration with Microsoft

Microsoft Corporation is an American multinational corporation and technology company, technology conglomerate headquartered in Redmond, Washington. Founded in 1975, the company became influential in the History of personal computers#The ear ...

, and is based on the same technology as Windows XP

Windows XP is a major release of Microsoft's Windows NT operating system. It was released to manufacturing on August 24, 2001, and later to retail on October 25, 2001. It is a direct successor to Windows 2000 for high-end and business users a ...

, which led the media to give it the nickname "Windows for Submarines", with the UK Defence Journal

The UK Defence Journal is a website covering defence industry news in the United Kingdom. In addition to news content, the site also offers commentary and analysis of military topics ranging from national security policy to procurement decision ...

fact checking group countering claims the vessels run on Windows XP

Windows XP is a major release of Microsoft's Windows NT operating system. It was released to manufacturing on August 24, 2001, and later to retail on October 25, 2001. It is a direct successor to Windows 2000 for high-end and business users a ...

. In addition to the missile tubes, the submarines are fitted with four torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s and carry the Spearfish torpedo

The Spearfish torpedo (formally Naval Staff Target 7525) is the heavy torpedo used by the submarines of the Royal Navy. It can be guided by Torpedo#Radio and wire guidance, wire or by acoustic homing, autonomous active or passive sonar, and pro ...

, allowing them to engage submerged or surface targets at ranges up to . Two SSE Mark 10 launchers are also fitted, allowing the boats to deploy Type 2066 and Type 2071 decoys, and a UAP Mark 3 electronic support measures (ESM) intercept system is carried. A "Core H" reactor is fitted to each of the boats during their long-overhaul refit periods, ensuring that none of the submarines will need further re-fuelling.

Thatcher laid the keel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element of a watercraft, important for stability. On some sailboats, it may have a fluid dynamics, hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose as well. The keel laying, laying of the keel is often ...

of the first boat, HMS ''Vanguard'', on 3 September 1986, and it was commissioned on 14 August 1993. She was followed by her sisters, , which was laid down on 3 December 1987 and commissioned on 7 January 1995; , which was laid down on 16 February 1991 and commissioned on 2 November 1996; and , which was laid down on 1 February 1993 and commissioned on 27 November 1999. The first British Trident missile was test-fired from ''Vanguard'' on 26 May 1994, and she began her first patrol in December of that year. According to the Royal Navy, at least one submarine has always been on patrol ever since.

Warheads

In British service, Trident II missiles are fitted with a thermonuclear warhead called Holbrook. The warhead has a choice of two warhead yields the highest of which is thought to be , with a lower yield in the range of . The UK government was sensitive to charges that the replacement of Polaris with Trident would involve an escalation in the numbers of British nuclear weapons. When the decision to purchase Trident II was announced in 1982, it was stressed that while American Trident boats carried 24 missiles with eight warheads each, a total of 192 warheads, British Trident boats would carry no more than 128 warheads—the same number as Polaris. In November 1993, the Secretary of State for Defence,

In British service, Trident II missiles are fitted with a thermonuclear warhead called Holbrook. The warhead has a choice of two warhead yields the highest of which is thought to be , with a lower yield in the range of . The UK government was sensitive to charges that the replacement of Polaris with Trident would involve an escalation in the numbers of British nuclear weapons. When the decision to purchase Trident II was announced in 1982, it was stressed that while American Trident boats carried 24 missiles with eight warheads each, a total of 192 warheads, British Trident boats would carry no more than 128 warheads—the same number as Polaris. In November 1993, the Secretary of State for Defence, Malcolm Rifkind

Sir Malcolm Leslie Rifkind (born 21 June 1946) is a British politician who served in the cabinets of Margaret Thatcher and John Major from 1986 to 1997, and most recently as chair of the Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament from 2 ...

, announced that each boat would deploy no more than 96 warheads. In 2010 this was reduced to a maximum of 40 warheads, split between eight missiles. The consequent reduction in warhead production and refurbishment was estimated to save £22 million over a ten-year period. However in 2021 the Prime Minister Boris Johnson

Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson (born 19 June 1964) is a British politician and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 2019 to 2022. He wa ...

announced that the total number of warheads was being lifted from 180 to 260.

The warheads are primarily constructed at AWE Aldermaston, with other parts being made at other AWE facilities such as Burghfield. The British government insists the warhead is indigenously designed, but analysts including Hans M. Kristensen with the Federation of American Scientists

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) is an American nonprofit global policy think tank with the stated intent of using science and scientific analysis to attempt to make the world more secure. FAS was founded in 1945 by a group of scient ...

believe that it is largely based on the US W76 design. Under the 1958 US–UK Mutual Defence Agreement the UK is allowed to draw upon US warhead design information, but constructing and maintaining warheads for the Trident programme is the responsibility of AWE. US President George H. W. Bush

George Herbert Walker BushBefore the outcome of the 2000 United States presidential election, he was usually referred to simply as "George Bush" but became more commonly known as "George H. W. Bush", "Bush Senior," "Bush 41," and even "Bush th ...

authorised the transfer of nuclear warhead components to the UK between 1991 and 1996. The first Holbrook warhead was finished in September 1992 with production probably ending in 1999. Each warhead is housed in a cone-shaped re-entry vehicle made in the US called the Mk 4 and is the same reentry vehicle used by the US Navy with its W76 warhead. This shell protects it from the high temperatures experienced upon re-entry into Earth's atmosphere. The Trident warhead's fusing, arming and firing mechanisms are carefully designed so that it can only detonate after launch and ballistic deployment.

On 25 February 2020, the UK released a Written Statement outlining that the current UK nuclear warheads will be replaced and will match the US Trident SLBM and related systems. Earlier, it was reported that Commander US Strategic Command, Admiral Charles Richard, mentioned in a Senate hearing that the UK was already working to replace its warheads, which would share technology with the future W93 warhead.

In March 2024, the Ministry of Defence released a report which detailed, the replacement warhead would be designated as the A21/Mk7 and named Astraea

In ancient Greek religion and mythology, Astraea (; ), also spelled Astrea or Astria, is a daughter of Astraeus and Eos. She is the virgin goddess of justice, innocence, purity, and precision. She is closely associated with the Greek goddess of ...

''.'' The A21 Astraea warhead is to be a "sovereign design". It will be the first UK warhead to be deployed without live tests, relying on simulations and models from the AWE and EPURE, a joint UK-French facility.

, the UK had a stockpile of 215 warheads, of which 120 are operationally available. In 2022 the UK Government announced that "the UK will move to an overall nuclear weapon stockpile of no more than 260 warheads." British SSBNs on patrol carried a maximum of 40 warheads and 8 missiles. In 2011 it was reported that British warheads would receive the new Mk 4A reentry vehicles and some or all of the other upgrades that US W76 warheads were receiving in their W76-1 Life Extension Program. Some reports suggested that British warheads would receive the same arming, fusing and firing system (AF&F) as the US W76-1. This new AF&F system, called the MC4700, would increase weapon lethality against hard targets such as missile silos and bunkers.

Due to the distance of between AWE Aldermaston and the UK's nuclear weapon storage depot at RNAD Coulport, Holbrook (Trident) warheads are transported by road in heavily armed convoys by Ministry of Defence Police

The Ministry of Defence Police (MDP) is a civilian special police force#United Kingdom, special police force which is part of the United Kingdom's Ministry of Defence (United Kingdom), Ministry of Defence. The MDP's primary responsibilities are ...

. According to a pressure group, between 2000 and 2016 the vehicles were involved in 180 incidents, ranging from delays and diversions because of accidents, protests, or bad weather, to a sudden loss of power in one of the lorries, which halted a convoy and caused a double lane closure and a tailback on the M6 motorway

The M6 motorway is the longest motorway in the United Kingdom. It is located entirely within England, running for just over from the Midlands to the border with Scotland. It begins at Junction 19 of the M1 motorway, M1 and the western end of t ...

. The group's analysis stated the incidents were more frequent in the years 2013–2015.

Trident II D-5 missiles

Trident II D-5 is a submarine-launched ballistic missile built by

Trident II D-5 is a submarine-launched ballistic missile built by Lockheed Martin Space Systems

Lockheed Martin Space is one of the four major business divisions of Lockheed Martin. It has its headquarters in Littleton, Colorado, with additional sites in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania; Sunnyvale, California; Santa Cruz, California; Huntsville ...

in Sunnyvale, California

Sunnyvale () is a city located in the Santa Clara Valley in northwestern Santa Clara County, California, United States.

Sunnyvale lies along the historic El Camino Real (California), El Camino Real and U.S. Route 101 in California, Highway 1 ...

, and deployed by the US Navy and the Royal Navy. The British government contributed five per cent of its research and development costs under the modified Polaris Sales Agreement. The development contract was issued in October 1983, and the first launch occurred in January 1987. The first submarine launch was attempted by in March 1989. This attempt failed because the plume of water following the missile rose to a greater height than expected, resulting in water being in the nozzle when the motor ignited. Once the problem was understood, simple changes were quickly made, but the problem delayed the entry into service of Trident II until March 1990.

Trident II D-5 is more sophisticated than its predecessor, Trident I C-4, and has a greater payload capacity. All three stages of the Trident II D-5 are made of graphite epoxy, making the missile much lighter than its predecessor. The first test from a British ''Vanguard''-class submarine took place in 1994. The missile is long, weighs , has a range of , a top speed of over (Mach 17.4) and a circular error probable

Circular error probable (CEP),Circular Error Probable (CEP), Air Force Operational Test and Evaluation Center Technical Paper 6, Ver 2, July 1987, p. 1 also circular error probability or circle of equal probability, is a measure of a weapon s ...

(CEP) accuracy to within "a few feet". It is guided using an inertial navigation system

An inertial navigation system (INS; also inertial guidance system, inertial instrument) is a navigation device that uses motion sensors (accelerometers), rotation sensors (gyroscopes) and a computer to continuously calculate by dead reckoning th ...

combined with a star tracker

A star tracker is an optical device that measures the positions of stars using photocells or a camera.

As the positions of many stars have been measured by astronomers to a high degree of accuracy, a star tracker on a satellite or spacecraft may ...

, and is not dependent on the American-run Global Positioning System

The Global Positioning System (GPS) is a satellite-based hyperbolic navigation system owned by the United States Space Force and operated by Mission Delta 31. It is one of the global navigation satellite systems (GNSS) that provide ge ...

(GPS).

The 1998 Strategic Defence Review announced that the number of missile bodies would be limited to the 58 already purchased or under order, and the Royal Navy would not receive the final seven missiles previously planned. This saved about £50 million. The UK missiles form a shared pool with the Atlantic squadron of the US Navy ''Ohio''-class SSBNs at Kings Bay. The pool is "co-mingled" and missiles are selected at random for loading on to either nation's submarines. The first Trident boat, HMS ''Vanguard'', collected a full load of 16 missiles in 1994, but ''Victorious'' collected only 12 in 1995, and ''Vigilant'', 14 in 1997, leaving the remaining missile tubes empty.

By 1999, six missiles had been test fired, and another eight were earmarked for test firing. In June 2016, a Trident II D-5 missile test experienced anomalies with the telemetry equipment used, meaning it triggered a sequence to bring down the missile, as it could not be tracked to ensure it came down within its range safety conditions. The incident was not revealed until January 2017; the ''Sunday Times'' alleged that Downing Street

Downing Street is a gated street in City of Westminster, Westminster in London that houses the official residences and offices of the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and the Chancellor of the Exchequer. In a cul-de-sac situated off Whiteh ...

had "covered up" the incident "just weeks before the crucial House of Commons vote on the future of the missile system." Subsequent media reports said this was at the request of the US. A second failure occurred at the next launch in January 2024. It was claimed the fault was specific to the test and would have been unlikely to occur when using a real nuclear warhead, according to the Ministry of Defence

A ministry of defence or defense (see American and British English spelling differences#-ce.2C -se, spelling differences), also known as a department of defence or defense, is the part of a government responsible for matters of defence and Mi ...

. In both instances, the failure was due to additional telemetric test-firing equipment, not used for live firing.

Successful Royal Navy test firings had occurred in 2000, 2005, 2009 and 2012. They are infrequent due to the missile's £17 million cost. As of 2024, there have been 196 successful test firings of the Trident II D-5 missile from submarines since 1989, and 5 failed tests.

Cost

In the 1990s, the total acquisition cost of the Trident programme was £9.8 billion, about 38 per cent of which was incurred in the US. In 2005–06, annual expenditure for the running and capital costs was estimated at between £1.2 billion and £1.7 billion and was estimated to rise to £2bn to £2.2 billion in 2007–08, including Atomic Weapons Establishment costs. Since Trident became operational in 1994, annual expenditure has ranged between 3 and 4.5 per cent of the annual defence budget, and was projected to increase to 5.5 per cent of the defence budget by 2007–08. An important factor in the cost was theexchange rate

In finance, an exchange rate is the rate at which one currency will be exchanged for another currency. Currencies are most commonly national currencies, but may be sub-national as in the case of Hong Kong or supra-national as in the case of ...

between the dollar and the pound, which declined from $2.36 in September 1980 to $1.78 in March 1982.

Operation

Patrols

The principle of Trident's operation is known as Continuous At-Sea Deterrence (CASD), which means that at least one submarine is always on patrol. Another submarine is usually undergoing maintenance and the remaining two are in port or on training exercises. During a patrol, the submarine is required to remain silent and is allowed to make contact with the UK only in an emergency. It navigates using mappedcontour lines

A contour line (also isoline, isopleth, isoquant or isarithm) of a function of two variables is a curve along which the function has a constant value, so that the curve joins points of equal value. It is a plane section of the three-dimensi ...

of the ocean floor and patrols a series of planned "boxes" measuring several thousand square miles. A aerial trails on the surface behind the submarine to pick up incoming messages. Most of the 150 crew never know where they are or where they have been. The 350th patrol commenced on 29 September 2017. On 15 November 2018, a reception was held at Westminster to mark 50 years of CASD.

Command and control

Only the prime minister or a designated survivor can authorise the missiles to be fired. These orders would likely be issued from thePindar

Pindar (; ; ; ) was an Greek lyric, Ancient Greek lyric poet from Thebes, Greece, Thebes. Of the Western canon, canonical nine lyric poets of ancient Greece, his work is the best preserved. Quintilian wrote, "Of the nine lyric poets, Pindar i ...

command bunker under Whitehall

Whitehall is a road and area in the City of Westminster, Central London, England. The road forms the first part of the A roads in Zone 3 of the Great Britain numbering scheme, A3212 road from Trafalgar Square to Chelsea, London, Chelsea. It ...

in central London. From there, the order would be relayed to the Commander, Task Force

A task force (TF) is a unit or formation established to work on a single defined task or activity. Originally introduced by the United States Navy, the term has now caught on for general usage and is a standard part of NATO terminology. Many ...

345 (CTF 345) operations room at the Northwood Headquarters

Northwood Headquarters is a military headquarters facility of the British Armed Forces in Eastbury, Hertfordshire, England, adjacent to the London suburb of Northwood. It is home to the following military command and control functions:

#Headq ...

facility in Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire ( or ; often abbreviated Herts) is a ceremonial county in the East of England and one of the home counties. It borders Bedfordshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the north-east, Essex to the east, Greater London to the ...

, the only facility allowed to communicate with the ''Vanguard'' commander on patrol. Communications are relayed via IP over VLF from a transmitter site at Skelton near Penrith. Two personnel are required to authenticate each stage of the process before launching, with the submarine commander only able to activate the firing trigger after two safes have been opened with keys held by the ship's executive and weapon engineer officers. A parliamentary answer states that commanding officers of Royal Navy ballistic submarines receive training in the 'Law Of Armed Conflict'.

Bases

Trident is based at HMNB Clyde on the west coast of Scotland. The base consists of two facilities — Faslane Naval Base onGare Loch

The Gare Loch or Gareloch () is an open sea loch in Argyll and Bute in the west of Scotland, and it bears a similar name to the village of Gairloch in the north west Highlands.

The loch is well used for sailing, recreational boating, list of ...

near Helensburgh

Helensburgh ( ; ) is a town on the north side of the Firth of Clyde in Scotland, situated at the mouth of the Gareloch. Historically in Dunbartonshire, it became part of Argyll and Bute following local government reorganisation in 1996.

Histo ...

, and an ordnance depot with 16 concrete bunkers set into a hillside at Coulport, to the west. Faslane was constructed and first used as a base during the Second World War. This location was chosen as the base for nuclear-armed submarines at the height of the Cold War because of its position close to the deep and easily navigable Firth of Clyde. It provides for rapid and stealthy access through the North Channel to the patrolling areas in the North Atlantic, and through the GIUK gap

The GIUK gap (sometimes written G-I-UK) is an area in the northern Atlantic Ocean that forms a naval choke point. Its name is an acronym for ''Greenland, Iceland'', and the ''United Kingdom'', the gap being the two stretches of open ocean amo ...

between Iceland and Scotland to the Norwegian Sea

The Norwegian Sea (; ; ) is a marginal sea, grouped with either the Atlantic Ocean or the Arctic Ocean, northwest of Norway between the North Sea and the Greenland Sea, adjoining the Barents Sea to the northeast. In the southwest, it is separate ...

. Also based there are nuclear-powered fleet submarine

A fleet submarine is a submarine with the speed, range, and endurance to operate as part of a navy's battle fleet. Examples of fleet submarines are the British First World War era K class and the American World War II era ''Gato'' class.

The ...

s (SSNs). RNAD Coulport is used to store the nuclear warheads and has docking facilities where they are loaded onto submarines before going on patrol and unloaded when they return to the base. Repair and refit of the ''Vanguard''-class submarines takes place at HMNB Devonport

His Majesty's Naval Base, Devonport (HMNB Devonport) is one of three operating bases in the United Kingdom for the Royal Navy (the others being HMNB Clyde and HMNB Portsmouth) and is the sole nuclear repair and refuelling facility for the Roya ...

near Plymouth

Plymouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Devon, South West England. It is located on Devon's south coast between the rivers River Plym, Plym and River Tamar, Tamar, about southwest of Exeter and ...

, Devon.

Espionage

According to senior RAF officers the retirement of theNimrod

Nimrod is a Hebrew Bible, biblical figure mentioned in the Book of Genesis and Books of Chronicles, the Books of Chronicles. The son of Cush (Bible), Cush and therefore the great-grandson of Noah, Nimrod was described as a king in the land of Sh ...

maritime patrol aircraft in 2011 gave Russia the potential to gain "valuable intelligence" on the country's nuclear deterrent. As a result, plans to buy Northrop Grumman MQ-4C Triton

The Northrop Grumman MQ-4C Triton is an American high-altitude long endurance unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) developed for and flown by the United States Navy and Royal Australian Air Force as a surveillance aircraft. Together with its associate ...

unmanned aerial vehicles were reportedly considered. The Strategic Defence and Security Review 2015 The National Security Strategy and Strategic Defence and Security Review 2015 was published by the British government during the second Cameron ministry on 23 November 2015 to outline the United Kingdom's defence strategy up to 2025. It identified ...

announced that nine Boeing P-8 Poseidon

The Boeing P-8 Poseidon is an American maritime patrol and reconnaissance aircraft developed and produced by Boeing Defense, Space & Security. It was developed for the United States Navy as a derivative of the civilian Boeing 737 Next Generati ...

maritime patrol aircraft would be purchased for the RAF. They became operational on 3 April 2020.

Opposition

TheCampaign for Nuclear Disarmament

The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) is an organisation that advocates unilateral nuclear disarmament by the United Kingdom, international nuclear disarmament and tighter international arms regulation through agreements such as the Nucl ...

(CND) was a national movement founded in the late 1950s, initially in opposition to nuclear testing. It reached its peak around 1960, by which time it had evolved into a broader movement calling for Britain to unilaterally give up nuclear weapons, withdraw from NATO, and end the basing of nuclear-armed aircraft in the UK. The end of atmospheric nuclear testing, internal squabbles, and activists focusing their energies on other causes led to a rapid decline, but it revived in the early 1980s in the wake of the Thatcher government's December 1979 decision to allow the deployment of GLCMs in the UK under the NATO Double-Track Decision, and the announcement of the decision to purchase Trident in July 1980. Membership leapt from 3,000 in 1980 to 50,000 a year later, and rallies for unilateral nuclear disarmament in London in October 1981 and June 1982 attracted 250,000 marchers, the largest ever mass demonstrations in the UK up to that time.

The 1982 Labour Party Conference

The Labour Party Conference is the annual conference of the British Labour Party (UK), Labour Party. It is formally the supreme decision-making body of the party and is traditionally held in the final week of September, during the party conferen ...

adopted a platform calling for the removal of the GLCMs, the scrapping of Polaris and the cancellation of Trident. This was reaffirmed by the 1986 conference. While the party was given little chance of winning the 1983 election in the aftermath of the Falklands War, polls had shown Labour ahead of the Conservatives in 1986 and 1987. In the wake of Labour's unsuccessful performance in the 1987 election, the Labour Party leader, Neil Kinnock

Neil Gordon Kinnock, Baron Kinnock (born 28 March 1942) is a Welsh politician who was Leader of the Opposition (United Kingdom), Leader of the Opposition and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 1983 Labour Party le ...

, despite his own unilateralist convictions, moved to drop the party's disarmament policy, which he saw as a contributing factor in its defeat. The party formally voted to do so in October 1989.

Pro-independence Scottish political parties—the Scottish National Party

The Scottish National Party (SNP; ) is a Scottish nationalist and social democratic party. The party holds 61 of the 129 seats in the Scottish Parliament, and holds 9 out of the 57 Scottish seats in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, ...

(SNP), Scottish Green Party

The Scottish Greens (also known as the Scottish Green Party; ) are a green party, green List of political parties in Scotland, political party in Scotland. The party has 7 MSPs of 129 in the Scottish Parliament, the party holds 35 of the 1226 ...

, Scottish Socialist Party

The Scottish Socialist Party (SSP) is a Left-wing politics, left-wing political party campaigning for the establishment of an Scottish independence, independent Socialism, socialist Scottish Scottish republicanism, republic.

The party was fou ...

(SSP) and Solidarity

Solidarity or solidarism is an awareness of shared interests, objectives, standards, and sympathies creating a psychological sense of unity of groups or classes. True solidarity means moving beyond individual identities and single issue politics ...

—are opposed to the basing of the Trident system close to Glasgow, Scotland's largest city. Some members and ex-members of those parties, such as Tommy Sheridan and Lloyd Quinan, have taken part in blockades of the base. For a major House of Commons vote in 2007, the majority of Scottish members of parliament (MPs) voted against upgrading the system, while a substantial majority of English and Welsh MPs voted in favour. The house backed plans to renew the programme by 409 votes to 161.

Faslane Peace Camp is permanently sited near Faslane naval base. It has been occupied continuously, albeit in different locations, since 12 June 1982. In 2006, a year-long protest at Trident's base at Faslane aimed to blockade the base every day for a year. More than 1,100 people were arrested.

During the 2020 coronavirus pandemic a letter was circulated to MPs by the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation which stated, “It is completely unacceptable that the UK continues to spend billions of pounds on deploying and modernising the Trident Nuclear Weapon System when faced with the threats to health, climate change and world economies that Coronavirus poses.” Signatories included Commander Robert Forsyth RN (Ret'd), a former nuclear submariner; Commander Robert Green RN (Ret'd), a former nuclear-armed aircraft bombardier-navigator and Staff Officer (Intelligence) to CINFLEET in the Falklands War; and Commander Colin Tabeart RN (Ret'd), a former Senior Engineer Officer on a Polaris submarine. Following this the MoD updated its online instruction notice to staff on public communications to say, “All contact with the media or communication in public by members of the armed forces and MoD civilians where this relates to defence or government business must be authorised in advance”.

Reviews

Royal United Services Institute

TheRoyal United Services Institute

The Royal United Services Institute (RUSI, Rusi) is a defence and security think tank with its headquarters in London, United Kingdom. It was founded in 1831 by the Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, Duke of Wellington, Arthur Wellesley ...

(RUSI), a British defence and security think tank

A think tank, or public policy institute, is a research institute that performs research and advocacy concerning topics such as social policy, political strategy, economics, military, technology, and culture. Most think tanks are non-governme ...