The history of the United States Navy divides into two major periods: the "Old Navy", a small but respected force of

sailing ship

A sailing ship is a sea-going vessel that uses sails mounted on Mast (sailing), masts to harness the power of wind and propel the vessel. There is a variety of sail plans that propel sailing ships, employing Square rig, square-rigged or Fore-an ...

s that became notable for innovation in the use of

ironclads

An ironclad was a steam-propelled warship protected by steel or iron armor constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships to explosive or incendiary shells. The firs ...

during the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, and the "New Navy" the result of a modernization effort that began in the 1880s and made it the largest in the world by 1943.

The

United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

claims October 13, 1775 as the date of its official establishment, when the

Second Continental Congress

The Second Continental Congress (1775–1781) was the meetings of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that united in support of the American Revolution and American Revolutionary War, Revolutionary War, which established American independence ...

passed a resolution creating the

Continental Navy

The Continental Navy was the navy of the United Colonies and United States from 1775 to 1785. It was founded on October 13, 1775 by the Continental Congress to fight against British forces and their allies as part of the American Revolutionary ...

. With the end of the

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

, the Continental Navy was disbanded. Under the

Presidency of George Washington

George Washington's tenure as the inaugural president of the United States began on April 30, 1789, the day of his First inauguration of George Washington, first inauguration, and ended on March 4, 1797. Washington took office after he was Li ...

, merchant shipping came under threat while in the Mediterranean by Barbary pirates from four North African States. This led to the

Naval Act of 1794

The Act to Provide a Naval Armament (Sess. 1, ch. 12, ), also known as the Naval Act of 1794, or simply, the Naval Act, was passed by the 3rd United States Congress on March 27, 1794, and signed into law by President George Washington. The act ...

, which created a permanent standing U.S. Navy. The

original six frigates were authorized as part of the Act. Over the next 20 years, the Navy fought the

French Republic Navy in the

Quasi-War

The Quasi-War was an undeclared war from 1798 to 1800 between the United States and the French First Republic. It was fought almost entirely at sea, primarily in the Caribbean and off the East Coast of the United States, with minor actions in ...

(1798–99),

Barbary states

The Barbary Coast (also Barbary, Berbery, or Berber Coast) were the coastal regions of central and western North Africa, more specifically, the Maghreb and the Ottoman borderlands consisting of the regencies in Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli, a ...

in the

First

First most commonly refers to:

* First, the ordinal form of the number 1

First or 1st may also refer to:

Acronyms

* Faint Images of the Radio Sky at Twenty-Centimeters, an astronomical survey carried out by the Very Large Array

* Far Infrared a ...

and

Second Barbary War

The Second Barbary War, also known as the U.S.–Algerian War and the Algerine War, was a brief military conflict between the United States and the North African state of Algiers in 1815.

Piracy had been rampant along the North African "Barb ...

s, and the British in the

War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

. After the War of 1812, the U.S. Navy was at peace until the

Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

in 1846, and served to combat piracy in the Mediterranean and Caribbean seas, as well as fighting the slave trade off the coast of

West Africa

West Africa, also known as Western Africa, is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations geoscheme for Africa#Western Africa, United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Gha ...

. In 1845, the

Naval Academy

A naval academy provides education for prospective naval officers.

List of naval academies

See also

* Military academy

{{Authority control

Naval academies,

Naval lists ...

was founded at old Fort Severn at

Annapolis, Maryland

Annapolis ( ) is the capital of the U.S. state of Maryland. It is the county seat of Anne Arundel County and its only incorporated city. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east ...

by the

Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula, including parts of the Ea ...

. In 1861, the American Civil War began and the U.S. Navy fought the small

Confederate States Navy

The Confederate States Navy (CSN) was the Navy, naval branch of the Confederate States Armed Forces, established by an act of the Confederate States Congress on February 21, 1861. It was responsible for Confederate naval operations during the Amer ...

with both sailing ships and new revolutionary ironclad ships while forming a blockade that shut down the Confederacy's civilian coastal shipping. After the Civil War, most of its ships were laid up in reserve, and by 1878, the Navy was just 6,000 men.

In 1882, the U.S. Navy consisted of many outdated ship designs. Over the next decade, Congress approved building multiple modern steel-hulled

armored cruiser

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was designed like other types of cruisers to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a pre-dreadnought battles ...

s and

battleship

A battleship is a large, heavily naval armour, armored warship with a main battery consisting of large naval gun, guns, designed to serve as a capital ship. From their advent in the late 1880s, battleships were among the largest and most form ...

s, and by around the start of the 20th century had moved from twelfth place in 1870 to fifth place in terms of numbers of ships. Most sailors were foreigners. After winning two major battles during the 1898

Spanish–American War

The Spanish–American War (April 21 – August 13, 1898) was fought between Restoration (Spain), Spain and the United States in 1898. It began with the sinking of the USS Maine (1889), USS ''Maine'' in Havana Harbor in Cuba, and resulted in the ...

, the American Navy continued to build more ships, and by the end of

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

had more men and women in uniform than the British

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

.

The

Washington Naval Conference

The Washington Naval Conference (or the Washington Conference on the Limitation of Armament) was a disarmament conference called by the United States and held in Washington, D.C., from November 12, 1921, to February 6, 1922.

It was conducted out ...

of 1921 recognized the Navy as equal in capital ship size to the Royal Navy, and during the 1920s and 1930s, the Navy built several

aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and hangar facilities for supporting, arming, deploying and recovering carrier-based aircraft, shipborne aircraft. Typically it is the ...

s and battleships. The Navy was drawn into World War II after the Japanese

Attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Empire of Japan on the United States Pacific Fleet at Naval Station Pearl Harbor, its naval base at Pearl Harbor on Oahu, Territory of ...

on December 7, 1941, and over the next four years fought many historic battles including the

Battle of the Coral Sea

The Battle of the Coral Sea, from 4 to 8 May 1942, was a major naval battle between the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) and naval and air forces of the United States and Australia. Taking place in the Pacific Theatre of World War II, the battle ...

, the

Battle of Midway

The Battle of Midway was a major naval battle in the Pacific Ocean theater of World War II, Pacific Theater of World War II that took place on 4–7 June 1942, six months after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor and one month after the Battle of t ...

, multiple naval battles during the

Guadalcanal Campaign

The Guadalcanal campaign, also known as the Battle of Guadalcanal and codenamed Operation Watchtower by the United States, was an Allies of World War II, Allied offensive against forces of the Empire of Japan in the Solomon Islands during th ...

, and the largest naval battle in history, the

Battle of Leyte Gulf

The Battle of Leyte Gulf () 23–26 October 1944, was the largest naval battle of World War II and by some criteria the largest naval battle in history, with over 200,000 naval personnel involved.

By late 1944, Japan possessed fewer capital sh ...

. Much of the Navy's activity concerned the support of landings, not only with the "

island-hopping

Leapfrogging was an amphibious military strategy employed by the Allies in the Pacific War against the Empire of Japan during World War II. The key idea was to bypass heavily fortified enemy islands instead of trying to capture every island in ...

" campaign in the Pacific, but also with the European landings. When the Japanese surrendered, a large flotilla entered

Tokyo Bay

is a bay located in the southern Kantō region of Japan spanning the coasts of Tokyo, Kanagawa Prefecture, and Chiba Prefecture, on the southern coast of the island of Honshu. Tokyo Bay is connected to the Pacific Ocean by the Uraga Channel. Th ...

to witness the formal ceremony conducted on the battleship , on which officials from the Japanese government signed the

Japanese Instrument of Surrender

The Japanese Instrument of Surrender was the written agreement that formalized the surrender of the Empire of Japan, marking the end of hostilities in World War II. It was signed by representatives from the Empire of Japan and from the Allied n ...

. By the end of the war, the Navy had over 1,600 warships.

After World War II ended, the U.S. Navy entered the 45 year long

Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

and participated in the

Korean

Korean may refer to:

People and culture

* Koreans, people from the Korean peninsula or of Korean descent

* Korean culture

* Korean language

**Korean alphabet, known as Hangul or Korean

**Korean dialects

**See also: North–South differences in t ...

and

Vietnam

Vietnam, officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV), is a country at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of about and a population of over 100 million, making it the world's List of countries and depende ...

proxy war

In political science, a proxy war is an armed conflict where at least one of the belligerents is directed or supported by an external third-party power. In the term ''proxy war'', a belligerent with external support is the ''proxy''; both bel ...

s. Nuclear power and ballistic and guided missile technology led to new ship propulsion and weapon systems, which were used in the s and s. By 1978, the number of ships had dwindled to less than 400, many of which were from World War II, which prompted

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

to institute a program for a modern,

600-ship Navy. Following the 1990-91 collapse of the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

the Soviet Navy was divided among the former Soviet Republics and was left without funding, which made the United States the world's undisputed naval superpower, with the ability to engage and

project power in two simultaneous limited wars along separate fronts. This ability was demonstrated during the

First

First most commonly refers to:

* First, the ordinal form of the number 1

First or 1st may also refer to:

Acronyms

* Faint Images of the Radio Sky at Twenty-Centimeters, an astronomical survey carried out by the Very Large Array

* Far Infrared a ...

and

Second Persian Gulf Wars.

In March 2007, the U.S. Navy reached its smallest fleet size, with 274 ships, since World War I. Former U.S. Navy admirals who head the

U.S. Naval Institute

The United States Naval Institute (USNI) is a private non-profit military association that offers independent, nonpartisan forums for debate of national security issues. In addition to publishing magazines and books, the Naval Institute holds se ...

have raised concerns about what they see as the ability to respond to 'aggressive moves by Iran and China.'

The United States Navy was overtaken by the Chinese

People's Liberation Army Navy

The People's Liberation Army Navy, also known as the People's Navy, PLA Navy or simply Chinese Navy, is the naval warfare military branch, branch of the People's Liberation Army, the national military of the People's Republic of China. It i ...

in terms of raw number of ships in 2020.

Foundations of the "Old Navy"

Continental Navy (1775–1785)

The Navy was rooted in the American seafaring tradition, which produced a large community of sailors, captains and shipbuilders during the colonial era. During the Revolution, several states operated their own navies. On June 12, 1775, the

Rhode Island General Assembly

The State of Rhode Island General Assembly is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Rhode Island. A bicameral body, it is composed of the lower Rhode Island House of Representatives with 75 representatives, and the upper Rhode Island Se ...

passed a resolution creating a navy for the colony of Rhode Island. The same day, Governor

Nicholas Cooke

Nicholas Cooke (February 3, 1717September 14, 1782) was an American politician, slave-trader, and ropemaker who served as the governor of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations during the American Revolutionary War, and after Rhod ...

signed orders addressed to Captain

Abraham Whipple

Commander Abraham Whipple (September 26, 1733 – May 27, 1819) was an American naval officer best known for his service in the Continental Navy during the Revolutionary War and being one of the founders of Marietta, Ohio. Born near Providenc ...

, commander of the sloop

''Katy'', and commodore of the armed vessels employed by the government.

The first formal movement for the creation of the

Continental Navy

The Continental Navy was the navy of the United Colonies and United States from 1775 to 1785. It was founded on October 13, 1775 by the Continental Congress to fight against British forces and their allies as part of the American Revolutionary ...

came from Rhode Island, because the widespread smuggling activities of Rhode Island merchants had been increasingly suppressed by the British

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

. On August 26, 1775, Rhode Island passed a resolution that there be a single

Continental fleet funded by the

Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislature, legislative bodies, with some executive function, for the Thirteen Colonies of British America, Great Britain in North America, and the newly declared United States before, during, and after ...

.

The resolution was introduced in the Continental Congress on October 3, 1775, but was tabled. In the meantime,

George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

had begun to acquire ships, starting with the schooner that was paid for out of Washington's own pocket.

[ ''Hannah'' was commissioned and launched on September 5, 1775, under the command of Captain ]Nicholson Broughton

Captain Nicholson Broughton (1724–1798) of Marblehead, Massachusetts was the first commodore of the United States Navy, American Navy and, as part of the 14th Continental Regiment, Marblehead Regiment, commanded George Washington’s first nav ...

, from the port of Marblehead, Massachusetts

Marblehead is a coastal New England town in Essex County, Massachusetts, United States, along the North Shore (Massachusetts), North Shore. Its population was 20,441 at the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census. The town lies on a small peninsu ...

.

The US Navy recognizes October 13, 1775, as the date of its official establishment—the date of the passage of the resolution of the Continental Congress at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, that created the Continental Navy.Benedict Arnold

Benedict Arnold (#Brandt, Brandt (1994), p. 4June 14, 1801) was an American-born British military officer who served during the American Revolutionary War. He fought with distinction for the American Continental Army and rose to the rank of ...

ordered the construction of 12 naval vessels to slow down the progress of British forces which had entered New York from Canada. In the ensuing engagement, a Royal Navy fleet decisively defeated Arnold's ships after two days of fighting, but the battle managed to slow down the progression of British ground forces in New York.frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and maneuvera ...

s approved by Congress, were under construction, but their effectiveness was limited; they were completely outmatched by the Royal Navy, and nearly all were captured or sunk by 1781.privateer

A privateer is a private person or vessel which engages in commerce raiding under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign o ...

s had some success, with 1,697 letters of marque

A letter of marque and reprisal () was a government license in the Age of Sail that authorized a private person, known as a privateer or corsair, to attack and capture vessels of a foreign state at war with the issuer, licensing internationa ...

being issued by Congress. Individual states, American agents in Europe and in the Caribbean also issued commissions; taking duplications into account more than 2,000 commissions were issued by various sources. Over 2,200 British merchant ships were captured by American privateers during the war, amounting to almost $66 million, a significant sum at the time.John Paul Jones

John Paul Jones (born John Paul; July 6, 1747 – July 18, 1792) was a Scottish-born naval officer who served in the Continental Navy during the American Revolutionary War. Often referred to as the "Father of the American Navy", Jones is regard ...

, who a voyage around the British Isles

The British Isles are an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner Hebrides, Inner and Outer Hebr ...

captured the Royal Navy frigate in the Battle of Flamborough Head

The Battle of Flamborough Head was a naval battle that took place on 23 September 1779 in the North Sea off the coast of Yorkshire between a combined Franco-American squadron, led by Continental Navy officer John Paul Jones, and two British e ...

. Partway through the battle, with the rigging

Rigging comprises the system of ropes, cables and chains, which support and control a sailing ship or sail boat's masts and sails. ''Standing rigging'' is the fixed rigging that supports masts including shrouds and stays. ''Running rigg ...

of the two ships entangled, and several guns of Jones' ship out of action, the captain of ''Serapis'' asked Jones if he had struck his colors, to which Jones has been quoted as replying, "I have not yet begun to fight!"French Navy

The French Navy (, , ), informally (, ), is the Navy, maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the four military service branches of History of France, France. It is among the largest and most powerful List of navies, naval forces i ...

sent to the Western Hemisphere spent most of the year in the West Indies, and only sailed near the Thirteen Colonies during the Caribbean hurricane season from July until November. A French Navy fleet attempted landings in New York and Rhode Island in 1778, but ultimately failed to engage British forces.

Disarmament (1785–1794)

The Revolutionary War was ended by the Treaty of Paris in 1783, and by 1785 the Continental Navy was disbanded and the remaining ships were sold. The frigate , which had fired the last shots of the American Revolutionary War, was also the last ship in the Navy. A faction within Congress wanted to keep the ship, but the new nation did not have the funds to keep her in service. Other than a general lack of money, factors for the disarmament of the navy were the loose confederation of the states, a change of goals from war to peace, and more domestic and fewer foreign interests.

The Revolutionary War was ended by the Treaty of Paris in 1783, and by 1785 the Continental Navy was disbanded and the remaining ships were sold. The frigate , which had fired the last shots of the American Revolutionary War, was also the last ship in the Navy. A faction within Congress wanted to keep the ship, but the new nation did not have the funds to keep her in service. Other than a general lack of money, factors for the disarmament of the navy were the loose confederation of the states, a change of goals from war to peace, and more domestic and fewer foreign interests.tariff

A tariff or import tax is a duty (tax), duty imposed by a national Government, government, customs territory, or supranational union on imports of goods and is paid by the importer. Exceptionally, an export tax may be levied on exports of goods ...

s on imported goods. Because of rampant smuggling

Smuggling is the illegal transportation of objects, substances, information or people, such as out of a house or buildings, into a prison, or across an international border, in violation of applicable laws or other regulations. More broadly, soc ...

, the need was immediate for strong enforcement of tariff laws.United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature, legislative branch of the federal government of the United States. It is a Bicameralism, bicameral legislature, including a Lower house, lower body, the United States House of Representatives, ...

, urged on by Secretary of the Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the first U.S. secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795 dur ...

, created the Revenue-Marine

The United States Revenue Cutter Service was established by an Act of Congress () on 4 August 1790 as the Revenue-Marine at the recommendation of the nation's first U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton.

The federal government body ...

, the forerunner for the United States Coast Guard

The United States Coast Guard (USCG) is the maritime security, search and rescue, and Admiralty law, law enforcement military branch, service branch of the armed forces of the United States. It is one of the country's eight Uniformed services ...

, to enforce the tariff and all other maritime laws.Barbary states

The Barbary Coast (also Barbary, Berbery, or Berber Coast) were the coastal regions of central and western North Africa, more specifically, the Maghreb and the Ottoman borderlands consisting of the regencies in Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli, a ...

, so their ships were vulnerable for capture after 1785. By 1789, the new Constitution of the United States

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, on March 4, 1789. Originally includi ...

authorized Congress to create a navy, but during George Washington's first term (1787–1793) little was done to rearm the navy.French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars () were a series of sweeping military conflicts resulting from the French Revolution that lasted from 1792 until 1802. They pitted French First Republic, France against Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain, Habsb ...

between Great Britain and France began, and a truce negotiated between Portugal and Algiers

Algiers is the capital city of Algeria as well as the capital of the Algiers Province; it extends over many Communes of Algeria, communes without having its own separate governing body. With 2,988,145 residents in 2008Census 14 April 2008: Offi ...

ended Portugal's blockade of the Strait of Gibraltar

The Strait of Gibraltar is a narrow strait that connects the Atlantic Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea and separates Europe from Africa.

The two continents are separated by 7.7 nautical miles (14.2 kilometers, 8.9 miles) at its narrowest point. Fe ...

which had kept the Barbary pirates

The Barbary corsairs, Barbary pirates, Ottoman corsairs, or naval mujahideen (in Muslim sources) were mainly Muslim corsairs and privateers who operated from the largely independent Barbary states. This area was known in Europe as the Barba ...

in the Mediterranean. Soon after, the pirates sailed into the Atlantic, and captured 11 American merchant ships and more than a hundred seamen.Naval Act of 1794

The Act to Provide a Naval Armament (Sess. 1, ch. 12, ), also known as the Naval Act of 1794, or simply, the Naval Act, was passed by the 3rd United States Congress on March 27, 1794, and signed into law by President George Washington. The act ...

, which authorized the building of six frigates, four of 44 guns and two of 36 guns. Supporters were mostly from the northern states and the coastal regions, who argued the Navy would result in savings in insurance and ransom payments, while opponents from southern states and inland regions thought a navy was not worth the expense and would drive the United States into more costly wars.[

]

Establishment (1794–1812)

After the passage of the Naval Act of 1794, work began on the construction of the six frigates: , , , , , and . ''Constitution'', launched in 1797 and the most famous of the six, was nicknamed "Old Ironsides" (like the earlier ) and, thanks to the efforts of Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr.

Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. (; August 29, 1809 – October 7, 1894) was an American physician, poet, and polymath based in Boston. Grouped among the fireside poets, he was acclaimed by his peers as one of the best writers of the day. His most ...

, is still in existence today, anchored in Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

harbor. Soon after the bill was passed, Congress authorized $800,000 to obtain a treaty with the Algerians and ransom the captives, triggering an amendment of the Act which would halt the construction of ships if peace was declared. After considerable debate, three of the six frigates were authorized to be completed: ''United States'', ''Constitution'' and ''Constellation''.Treaty of Alliance (1778)

The Treaty of Alliance (), also known as the Franco-American Treaty, was a defensive alliance between the Kingdom of France and the United States formed amid the American Revolutionary War with Great Britain. It was signed by delegates of King ...

that had brought the French into the Revolutionary War. The United States preferred to take a position of neutrality in the conflicts between France and Britain, but this put the nation at odds with both the British and French. After the Jay Treaty

The Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation, Between His Britannic Majesty and the United States of America, commonly known as the Jay Treaty, and also as Jay's Treaty, was a 1794 treaty between the United States and Great Britain that averted ...

was signed with Great Britain in 1794, France began to side against the United States and by 1797 they had seized over 300 American vessels. The newly inaugurated President John Adams took steps to deal with the crisis, working with Congress to finish the three almost-completed frigates, approving funds to build the other three, and attempting to negotiate an agreement similar to the Jay Treaty with France. The XYZ Affair

The XYZ Affair was a political and diplomatic episode in 1797 and 1798, early in the presidency of John Adams, involving a confrontation between the History of the United States (1789–1849), United States and French First Republic, Republican ...

originated with a report distributed by Adams where alleged French agents were identified by the letters X, Y, and Z who informed the delegation a bribe must be paid before the diplomats could meet with the foreign minister, and the resulting scandal increased popular support in the country for a war with France.[ Concerns about the War Department's ability to manage a navy led to the creation of the ]Department of the Navy Navy Department or Department of the Navy may refer to:

* United States Department of the Navy

The United States Department of the Navy (DON) is one of the three military departments within the United States Department of Defense. It was esta ...

, which was established on April 30, 1798. The problems with the Barbary states had never gone away, and on May 10, 1801 the Tripolitans declared war on the United States by chopping down the flag in front of the American Embassy, which began the First Barbary War.

The problems with the Barbary states had never gone away, and on May 10, 1801 the Tripolitans declared war on the United States by chopping down the flag in front of the American Embassy, which began the First Barbary War.Stephen Decatur

Commodore (United States), Commodore Stephen Decatur Jr. (; January 5, 1779 – March 22, 1820) was a United States Navy officer. He was born on the eastern shore of Maryland in Worcester County, Maryland, Worcester County. His father, Ste ...

.Tripoli

Tripoli or Tripolis (from , meaning "three cities") may refer to:

Places Greece

*Tripolis (region of Arcadia), a district in ancient Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (Larisaia), an ancient Greek city in the Pelasgiotis district, Thessaly, near Larissa ...

" in 1805, capturing the city of Derna, the first time the U.S. flag ever flew over a foreign conquest.gunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.

History Pre-steam ...

s were built, intended for coastal use only. This policy proved completely ineffective within a decade.Revenue-Marine

The United States Revenue Cutter Service was established by an Act of Congress () on 4 August 1790 as the Revenue-Marine at the recommendation of the nation's first U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton.

The federal government body ...

, were all the nation needed to defend itself. However, this small fleet of lightly armed revenue cutters

Cutter may refer to:

Tools

* Bolt cutter

* Box cutter

* Cigar cutter

* Cookie cutter

* Cutter (hydraulic rescue tool)

* Glass cutter

* Meat cutter

* Milling cutter

* Paper cutter

* Pizza cutter

* Side cutter

People

* Cutter (surname)

* ...

, which Hamilton had proposed in Federalist Papers

''The Federalist Papers'' is a collection of 85 articles and essays written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay under the collective pseudonym "Publius" to promote the ratification of the Constitution of the United States. The col ...

No. 11 & 12, was insufficient as a wartime naval force for the needs of the new United States of America.

During the French Revolutionary Wars, the Royal Navy had begun to impress

Impress or Impression may refer to:

Arts

* Big Impression, a British comedy sketch show

*'' Impression, Sunrise'', a painting by Claude Monet

Biology

* Maternal impression, an obsolete scientific theory that explained the existence of birth de ...

sailors from American ships who they alleged were British deserters; an estimated 10,000 sailors were impressed this way between 1799 and 1812.

War of 1812 (1812–1815)

Much of the war was expected to be fought at sea; and within an hour of the announcement of war, the diminutive U.S. Navy set forth to do battle with an opponent outnumbering it 50-to-1. After two months, ''Constitution'' sank ; ''Guerriere''s crew were most dismayed to see their cannonballs bouncing off ''Constitution''s unusually strong live oak

Live oak or evergreen oak is any of a number of oaks in several different sections of the genus ''Quercus'' that share the characteristic of evergreen foliage. These oaks are generally not more closely related to each other than they are to o ...

hull, giving her the enduring nickname of "Old Ironsides".defeated

Defeated may refer to:

* "Defeated" (Breaking Benjamin song)

* "Defeated" (Anastacia song)

*"Defeated", a song by Snoop Dogg from the album ''Bible of Love''

*Defeated, Tennessee

Defeated is an unincorporated community in Smith County, Tennessee ...

off the coast of Brazil and ''Java'' was burned after the Americans determined she could not be salvaged. On October 25, 1812, ''United States'' captured HMS ''Macedonian''; after the battle ''Macedonian'' was captured and entered into American service.James Hillyar

Admiral (Royal Navy), Admiral Sir James Hillyar Order of the Bath, KCB Royal Guelphic Order, KCH (29 October 1769 – 10 July 1843) was a Royal Navy officer of the early nineteenth century, who is best known for his service in the frigate HMS Phoeb ...

, blockaded ''Essex'' before Porter ordered his ship to attempt to escape; in the ensuing battle, ''Essex'' was captured by the British.Boston Harbor

Boston Harbor is a natural harbor and estuary of Massachusetts Bay, located adjacent to Boston, Massachusetts. It is home to the Port of Boston, a major shipping facility in the Northeastern United States.

History 17th century

Since its dis ...

, the American frigate ''Chesapeake'', commanded by Captain James Lawrence

James Lawrence (October 1, 1781 – June 4, 1813) was an officer of the United States Navy. During the War of 1812, he commanded in a single-ship action against , commanded by Philip Broke. He is probably best known today for his last words, ...

, was captured by the British frigate under Captain Sir Philip Broke

Sir Philip Bowes Vere Broke, 1st Baronet (; 9 September 1776 – 2 January 1841) was a Royal Navy officer who served in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812. During his lifetime, he was often referred to as "Broke ...

. Lawrence was mortally wounded and famously cried out, "Don't give up the ship!".Chesapeake Campaign

The Chesapeake campaign, also known as the Chesapeake Bay campaign, of the War of 1812 was a British naval campaign that took place from 23 April 1813 to 14 September 1814 on and around the Delaware and Chesapeake bays of the United States.

...

, which was climaxed by amphibious assaults against Washington

Washington most commonly refers to:

* George Washington (1732–1799), the first president of the United States

* Washington (state), a state in the Pacific Northwest of the United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A ...

and Baltimore

Baltimore is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland. With a population of 585,708 at the 2020 census and estimated at 568,271 in 2024, it is the 30th-most populous U.S. city. The Baltimore metropolitan area is the 20th-large ...

. The capital fell to the British almost without a fight, and several American warships were burned at the Washington Navy Yard

The Washington Navy Yard (WNY) is a ceremonial and administrative center for the United States Navy, located in the federal national capital city of Washington, D.C. (federal District of Columbia). It is the oldest shore establishment / base of ...

, including the 44-gun frigate USS ''Columbia''. At Baltimore, the bombardment by Fort McHenry inspired Francis Scott Key to write "The Star-Spangled Banner

"The Star-Spangled Banner" is the national anthem of the United States. The lyrics come from the "Defence of Fort M'Henry", a poem written by American lawyer Francis Scott Key on September 14, 1814, after he witnessed the bombardment of Fort ...

", and the hulks blocking the channel prevented the fleet from entering the harbor; the army reembarked on the ships, ending the battle.[

The American naval victories at the ]Battle of Lake Champlain

The Battle of Plattsburgh, also known as the Battle of Lake Champlain, ended the final British invasion of the northern states of the United States during the War of 1812. Two British forces, an army under Lieutenant General Sir George Prévos ...

and Battle of Lake Erie

The Battle of Lake Erie, also known as the Battle of Put-in-Bay, was fought on 10 September 1813, on Lake Erie off the shores of Ohio during the War of 1812. Nine vessels of the United States Navy defeated and captured six vessels of the British ...

halted the final British offensive in the north and helped to deny the British exclusive rights to the Great Lakes in the Treaty of Ghent

The Treaty of Ghent () was the peace treaty that ended the War of 1812 between the United States and the United Kingdom. It took effect in February 1815. Both sides signed it on December 24, 1814, in the city of Ghent, United Netherlands (now in ...

.World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

Continental Expansion (1815–1861)

After the war, the Navy's accomplishments paid off in the form of better funding, and it embarked on the construction of many new ships. However, the expense of the larger ships was prohibitive, and many of them stayed in shipyards half-completed, in readiness for another war, until the Age of Sail

The Age of Sail is a period in European history that lasted at the latest from the mid-16th (or mid-15th) to the mid-19th centuries, in which the dominance of sailing ships in global trade and warfare culminated, particularly marked by the int ...

had almost completely passed. The main force of the Navy continued to be large sailing frigates with a number of smaller sloops during the three decades of peace. By the 1840s, the Navy began to adopt steam power and shell guns, but they lagged behind the French and British in adopting the new technologies. During the War of 1812, the Barbary states took advantage of the weakness of the United States Navy to again capture American merchant ships and sailors. After the Treaty of Ghent was signed, the United States looked at ending the piracy in the Mediterranean which had plagued American merchants for two decades. On March 3, 1815, Congress authorized deployment of naval power against Algiers, beginning the Second Barbary War. Two powerful squadrons under the command of Commodores Decatur and

During the War of 1812, the Barbary states took advantage of the weakness of the United States Navy to again capture American merchant ships and sailors. After the Treaty of Ghent was signed, the United States looked at ending the piracy in the Mediterranean which had plagued American merchants for two decades. On March 3, 1815, Congress authorized deployment of naval power against Algiers, beginning the Second Barbary War. Two powerful squadrons under the command of Commodores Decatur and William Bainbridge

Commodore William Bainbridge (May 7, 1774July 27, 1833) was a United States Navy officer. During his long career in the young American navy he served under six presidents beginning with John Adams and is notable for his many victories at sea. ...

, including the 74-gun ships of the line

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed during the Age of Sail from the 17th century to the mid-19th century. The ship of the line was designed for the naval tactic known as the line of battle, which involved the two column ...

, , and , were dispatched to the Mediterranean. Shortly after departing Gibraltar en route to Algiers, Decatur's squadron encountered the Algerian flagship '' Meshuda'', and, in the Action of June 17, 1815, captured it. Not long afterward, the American squadron likewise captured the Algerian brig

A brig is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: two masts which are both square rig, square-rigged. Brigs originated in the second half of the 18th century and were a common type of smaller merchant vessel or warship from then until the l ...

'' Estedio'' in the Battle off Cape Palos

The Battle of Cape Palos was the last battle of the Second Barbary War. The battle began when an American squadron under Commodore Stephen Decatur Jr. attacked and captured an Algerian brig.

Background

After capturing the Algerian flagship '' ...

. By June, the squadrons had reached Algiers and peace was negotiated with the Dey, including a return of captured vessels and men, a guarantee of no further tributes and a right to trade in the region.[ An agreement with Venezuela was reached in 1819, but ships were still regularly captured until a military campaign by the West India Squadron, under the command of David Porter, used a combination of large frigates escorting merchant ships backed by many small craft searching small coves and islands, and capturing pirate vessels. During this campaign became the first steam-powered ship to see combat action.]African squadron

The Africa Squadron was a unit of the United States Navy that operated from 1819 to 1861 in the Blockade of Africa to suppress the slave trade along the coast of West Africa. However, the term was often ascribed generally to anti-slavery oper ...

was formed in 1820 to deal with this threat. Politically, the suppression of the slave trade was unpopular, and the squadron was withdrawn in 1823 ostensibly to deal with piracy in the Caribbean, and did not return to the African coast until the passage of the Webster–Ashburton treaty

The Webster–Ashburton Treaty, signed August 9, 1842, was a treaty that resolved several border issues between the United States and the British North American colonies (the region that later became the Dominion of Canada). Negotiated in the U ...

with Britain in 1842. After the treaty was passed, the United States used fewer ships than the treaty required, ordered the ships based far from the coast of Africa, and used ships that were too large to operate close to shore. Between 1845 and 1850, the United States Navy captured only 10 slave vessels, while the British captured 423 vessels carrying 27,000 captives.United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

in 1802, but it took almost 50 years to approve a similar school for naval officers.Somers Affair

The Somers Affair was an incident involving the American brig during a training mission in 1842 under Captain Alexander Slidell Mackenzie (1803-1848). Midshipman Philip Spencer (sailor), Philip Spencer (1823-1842) was accused of plotting to overt ...

, an alleged mutiny

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military or a crew) to oppose, change, or remove superiors or their orders. The term is commonly used for insubordination by members of the military against an officer or superior, ...

aboard the training ship in 1842, and the subsequent execution of midshipman Philip Spencer.George Bancroft

George Bancroft (October 3, 1800 – January 17, 1891) was an American historian, statesman and Democratic Party (United States), Democratic politician who was prominent in promoting secondary education both in his home state of Massachusetts ...

, appointed Secretary of the Navy

The Secretary of the Navy (SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department within the United States Department of Defense. On March 25, 2025, John Phelan was confirm ...

in 1845, decided to work outside of congressional approval and create a new academy for officers. He formed a council led by Commodore

Commodore may refer to:

Ranks

* Commodore (rank), a naval rank

** Commodore (Royal Navy), in the United Kingdom

** Commodore (India), in India

** Commodore (United States)

** Commodore (Canada)

** Commodore (Finland)

** Commodore (Germany) or ' ...

Matthew Perry

Matthew Langford Perry (August 19, 1969 – October 28, 2023) was an American and Canadian actor, comedian, director and screenwriter. He gained international fame for starring as Chandler Bing on the NBC television sitcom ''Friends'' (1994– ...

to create a new system for training officers, and turned the old Fort Severn

Fort Severn, in present-day Annapolis, Maryland, was built in 1808 on the same site as an earlier American Revolutionary War fort of 1776. Although intended to guard Annapolis harbor from British attack during the War of 1812, it never saw act ...

at Annapolis

Annapolis ( ) is the capital of the U.S. state of Maryland. It is the county seat of Anne Arundel County and its only incorporated city. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east o ...

into a new institution in 1845 which would be designated as the United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (USNA, Navy, or Annapolis) is a United States Service academies, federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as United States Secre ...

by Congress in 1851.Second Seminole War

The Second Seminole War, also known as the Florida War, was a conflict from 1835 to 1842 in Florida between the United States and groups of people collectively known as Seminoles, consisting of Muscogee, Creek and Black Seminoles as well as oth ...

from 1836 until 1842. A "mosquito fleet" was formed in the Everglades out of various small craft to transport a mixture of army and navy personnel to pursue the Seminoles into the swamps. About 1,500 soldiers were killed during the conflict, some Seminoles agreed to move but a small group of Seminoles remained in control of the Everglades and the area around Lake Okeechobee.Battle of Veracruz

Veracruz, formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. Located in east ...

, it transported the invasion force that captured Veracruz

Veracruz, formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the 32 Political divisions of Mexico, Federal Entit ...

by landing 12,000 troops and their equipment in one day, leading eventually to the capture of Mexico City, and the end of the war. Its Pacific Squadron

The Pacific Squadron of the United States Navy, established c. 1821 and disbanded in 1907, was a naval squadron stationed in the Pacific Ocean in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Developing from a small force protecting United States commerc ...

's ships facilitated the capture of California.opening of Japan

]

The Perry Expedition (, , "Arrival of the Black Ships") was a diplomatic and military expedition in two separate voyages (1852–1853 and 1854–1855) to the Tokugawa shogunate () by warships of the United States Navy. The goals of this expedit ...

and normal trade relations with the United States and Europe.

American Civil War (1861–1865)

Between the beginning of the war and the end of 1861, 373 commissioned officers, warrant officers, and midshipmen resigned or were dismissed from the United States Navy and went on to serve the Confederacy.

Between the beginning of the war and the end of 1861, 373 commissioned officers, warrant officers, and midshipmen resigned or were dismissed from the United States Navy and went on to serve the Confederacy.Stephen Mallory

Stephen Russell Mallory (1812 – November 9, 1873) was an American politician who was a United States Senator from Florida from 1851 to the secession of his home state and the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861. For much of that perio ...

the idea of raising her and then armoring the upper sides with iron plate. The resulting ship was named . Meanwhile, John Ericsson

John Ericsson (born Johan Ericsson; July 31, 1803 – March 8, 1889) was a Swedish-American engineer and inventor. He was active in England and the United States.

Ericsson collaborated on the design of the railroad steam locomotive Novelty (lo ...

had similar ideas, and received funding to build .Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as Commanding General of the United States Army from 1841 to 1861, and was a veteran of the War of 1812, American Indian Wars, Mexica ...

, the commanding general of the U.S. Army at the beginning of the war, devised the Anaconda Plan

The Anaconda Plan was a strategy outlined by the Union Army for suppressing the Confederacy at the beginning of the American Civil War. Proposed by Union General-in-Chief Winfield Scott, the plan emphasized a Union blockade of the Southern port ...

to win the war with as little bloodshed as possible. His idea was that a Union blockade of the main ports would weaken the Confederate economy; then the capture of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

would split the South. Lincoln adopted the plan in terms of a blockade to squeeze to death the Confederate economy, but overruled Scott's warnings that his new army was not ready for an offensive operation because public opinion demanded an immediate attack. On March 8, 1862, the Confederate Navy initiated the first combat between

On March 8, 1862, the Confederate Navy initiated the first combat between ironclads

An ironclad was a steam-propelled warship protected by steel or iron armor constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships to explosive or incendiary shells. The firs ...

when ''Virginia'' successfully attacked the blockade. The next day, ''Monitor'' engaged ''Virginia'' in the Battle of Hampton Roads

The Battle of Hampton Roads, also referred to as the Battle of the ''Monitor'' and ''Merrimack'' or the Battle of Ironclads, was a naval battle during the American Civil War.

The battle was fought over two days, March 8 and 9, 1862, in Hampton ...

. Their battle ended in a draw, and the Confederacy later lost ''Virginia'' when the ship was scuttled to prevent capture. ''Monitor'' was the prototype for the monitor warship and many more were built by the Union Navy. While the Confederacy built more ironclad ships during the war, they lacked the ability to build or purchase ships that could effectively counter the monitors.naval mine

A naval mine is a self-contained explosive weapon placed in water to damage or destroy surface ships or submarines. Similar to anti-personnel mine, anti-personnel and other land mines, and unlike purpose launched naval depth charges, they are ...

s, which were known as ''torpedoes'' after the torpedo eel, and submarine warfare were introduced during the war by the Confederacy. During the Battle of Mobile Bay

The Battle of Mobile Bay of August 5, 1864, was a naval and land engagement of the American Civil War in which a Union fleet commanded by Rear Admiral David G. Farragut, assisted by a contingent of soldiers, attacked a smaller Confederate fle ...

, mines were used to protect the harbor and sank the Union monitor . After ''Tecumseh'' sank, Admiral David G. Farragut famously said, "Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!".spar torpedo

A spar torpedo is a weapon consisting of a bomb placed at the end of a long pole, or spar, and attached to a boat. The weapon is used by running the end of the spar into the enemy ship. Spar torpedoes were often equipped with a barbed spear at ...

. The Union ship was barely damaged and the resulting geyser of water put out the fires in the submarine's boiler, rendering the submarine immobile. Another submarine, , was designed to dive and surface but ultimately did not work well and sank on five occasions during trials. In action against the submarine successfully sank its target but was lost by the same explosion. The Confederates operated a number of

The Confederates operated a number of commerce raiders

Commerce raiding is a form of naval warfare used to destroy or disrupt logistics of the enemy on the open sea by attacking its merchant shipping, rather than engaging its combatants or enforcing a blockade against them. Privateering is a form ...

and blockade runner

A blockade runner is a merchant vessel used for evading a naval blockade of a port or strait. It is usually light and fast, using stealth and speed rather than confronting the blockaders in order to break the blockade. Blockade runners usua ...

s, being the most famous, and British investors built small, fast blockade runners that traded arms and luxuries brought in from Bermuda

Bermuda is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean. The closest land outside the territory is in the American state of North Carolina, about to the west-northwest.

Bermuda is an ...

, Cuba, and The Bahamas

The Bahamas, officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic and island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the Atlantic Ocean. It contains 97 per cent of the archipelago's land area and 88 per cent of ...

in return for high-priced cotton and tobacco. When the Union Navy seized a blockade runner, the ship and cargo were sold and the proceeds given to the Navy sailors; the captured crewmen were mostly British and they were simply released.food riots

A food riot is a riot in protest of a shortage and/or unequal distribution of food. Historical causes have included rises in food prices, harvest failures, inept food storage, transport problems, food speculation, hoarding, poisoning of food, a ...

across the Confederacy. The Union victory at the Second Battle of Fort Fisher

The Second Battle of Fort Fisher was a successful assault by the Union Army, Navy and Marine Corps against Fort Fisher, south of Wilmington, North Carolina, near the end of the American Civil War in January 1865. Sometimes referred to as the " ...

in January 1865 closed the last useful Southern port, virtually ending blockade running and hastening the end of the war.

Decline of the Navy (1865–1882)

After the war, the Navy went into a period of decline. In 1864, the Navy had 51,500 men in uniform,USS Dunderberg

''Dunderberg'', which is a Swedish language, Swedish word meaning "thunder(ing) mountain", was an ocean-going casemate ironclad of 14 guns built for the Union Navy. She resembled an enlarged, two-mast (sailing), masted version of the Confederate ...

'', viewing them as unnecessary for national defense. By 1863, anticipating deep post-war budget cuts, the Navy developed a new doctrine. Congress favored a peacetime fleet only composed of coastal ironclads and oceangoing “commerce destroyers” inspired by the Confederate commerce raiders. Under this doctrine, the ironclads would protect the American coast, while the commerce destroyers (the '' Contoocook'', ''Guerriere

''Guerrière'' was a 38-gun frigate of the French Navy, designed by Forfait. The British captured her and recommissioned her as HMS ''Guerriere''. She is most famous for her fight against .

Her career with the French included a sortie with ...

'', and ''Wampanoag''-classes) would target enemy merchant shipping

Maritime transport (or ocean transport) or more generally waterborne transport, is the transport of people (passengers or goods (cargo) via waterways. Freight transport by watercraft has been widely used throughout recorded history, as it pro ...

, and thus serve as an economic deterrent against European powers considering war. However, the commerce destroyers were laid down during war-time shortages of high quality wood, and were built with subpar material that forced them to be decommissioned only after a few years.American West

The Western United States (also called the American West, the Western States, the Far West, the Western territories, and the West) is census regions United States Census Bureau

As American settlement in the U.S. expanded westward, the mea ...

and an economic depression

An economic depression is a period of carried long-term economic downturn that is the result of lowered economic activity in one or more major national economies. It is often understood in economics that economic crisis and the following recession ...

. By 1880 the Navy only had 48 ships in commission, 6,000 men, and the ships and shore facilities were decrepit but Congress saw no need to spend money to improve them.Medals of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians, and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of va ...

for their acts of heroism during the Korean campaign; the first for actions in a foreign conflict.Virginius Affair

The ''Virginius'' Affair was a diplomatic dispute that occurred from October 1873 to February 1875 between the United States, Great Britain, and Spain (then in control of Cuba) during the Ten Years' War. ''Virginius'' was a fast American ship h ...

first broke out in 1873, a Spanish ironclad happened to be anchored in New York Harbor

New York Harbor is a bay that covers all of the Upper Bay. It is at the mouth of the Hudson River near the East River tidal estuary on the East Coast of the United States.

New York Harbor is generally synonymous with Upper New York Bay, ...

, leading to the uncomfortable realization on the part of the U.S. Navy that it had no ship capable of defeating such a vessel. The Navy hastily issued contracts for the construction of five new ironclads, and accelerated its existing repair program for several more.

"New Navy"

Rebuilding (1882–1898)

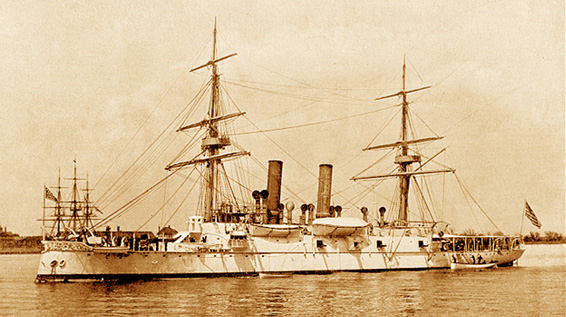

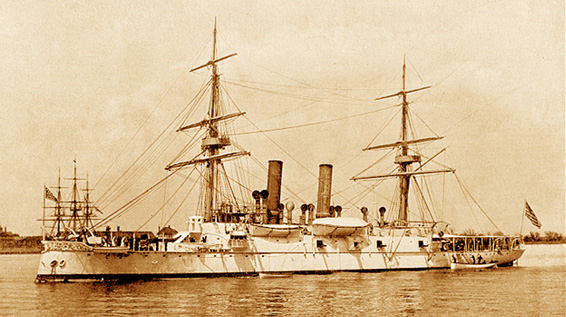

In 1882, on the recommendation of an advisory panel, the Navy Secretary William H. Hunt requested funds from Congress to construct modern ships. The request was rejected initially, but in 1883 Congress authorized the construction of three

In 1882, on the recommendation of an advisory panel, the Navy Secretary William H. Hunt requested funds from Congress to construct modern ships. The request was rejected initially, but in 1883 Congress authorized the construction of three protected cruiser

Protected cruisers, a type of cruiser of the late 19th century, took their name from the armored deck, which protected vital machine-spaces from fragments released by explosive shells. Protected cruisers notably lacked a belt of armour alon ...

s, , , and , and the dispatch vessel , together known as the ABCD ships.battleship

A battleship is a large, heavily naval armour, armored warship with a main battery consisting of large naval gun, guns, designed to serve as a capital ship. From their advent in the late 1880s, battleships were among the largest and most form ...

s in the Navy, and . The ABCD ships proved to be excellent vessels, and the three cruisers were organized into the Squadron of Evolution

The Squadron of Evolution—sometimes referred to as the "White Squadron" or the "ABCD ships" after the first four— was a transitional unit in the United States Navy during the late 19th century. It was probably inspired by the French "Escadre ...

, popularly known as the ''White Squadron'' because of the color of the hulls, which was used to train a generation of officers and men.Alfred Thayer Mahan

Alfred Thayer Mahan (; September 27, 1840 – December 1, 1914) was a United States Navy officer and historian whom John Keegan called "the most important American strategist of the nineteenth century." His 1890 book '' The Influence of Sea Pow ...

's book '' The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660–1783'', published in 1890 had momentous impact on major navies around the globe. In the United States it justified Expansion to both the government and the general public. With the closing of the frontier, geographical expansionists had to look outwards, to the Caribbean, to Hawaii and the Pacific, and with the doctrine of Manifest Destiny

Manifest destiny was the belief in the 19th century in the United States, 19th-century United States that American pioneer, American settlers were destined to expand westward across North America, and that this belief was both obvious ("''m ...

as philosophical justification, many saw the Navy as an essential part of realizing that doctrine beyond the limits of the American continent.Spanish–American War

The Spanish–American War (April 21 – August 13, 1898) was fought between Restoration (Spain), Spain and the United States in 1898. It began with the sinking of the USS Maine (1889), USS ''Maine'' in Havana Harbor in Cuba, and resulted in the ...

of 1898.torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, such ...

in Europe between 1866 and 1890 would also lead the Navy to build 35 steam-powered torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of ...

s between 1890 and 1901 for coastal defense.

Spanish–American War (1898)

The United States was interested in purchasing colonies from Spain, specifically Cuba, but Spain refused. Newspapers wrote stories, many which were fabricated, about atrocities committed in Spanish colonies which raised tensions between the two countries. A riot gave the United States an excuse to send ''Maine'' to Cuba, and the subsequent explosion of the ship in Havana Harbor

Havana Harbor is the port of Havana, the capital of Cuba, and it is the main port in Cuba. Other port cities in Cuba include Cienfuegos, Matanzas, Manzanillo, Cuba, Manzanillo, and Santiago de Cuba.

The harbor was created from the natural Havan ...

increased popular support for war with Spain. The cause of the explosion was investigated by a board of inquiry, which in March 1898 came to the conclusion the explosion was caused by a sea mine, and there was pressure from the public to blame Spain for sinking the ship. However, later investigations pointed to an internal explosion in one of the magazines caused by heat from a fire in the adjacent coal bunker.Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

quietly positioned the Navy for attack before the Spanish–American War was declared in April 1898. The Asiatic Squadron

The Asiatic Squadron was a squadron (naval), squadron of United States Navy warships stationed in East Asia during the latter half of the 19th century. It was created in 1868 when the East India Squadron was disbanded. Vessels of the squadron w ...

, under the command of George Dewey

George Dewey (December 26, 1837January 16, 1917) was Admiral of the Navy, the only person in United States history to have attained that rank. He is best known for his victory at the Battle of Manila Bay during the Spanish–American War, wi ...

, immediately left Hong Kong for the Philippines, attacking and decisively defeating the Spanish fleet in the Battle of Manila Bay

The Battle of Manila Bay (; ), also known as the Battle of Cavite, took place on May 1, 1898, during the Spanish–American War. The American Asiatic Squadron under Commodore George Dewey engaged and destroyed the Spanish Pacific Squad ...

. A few weeks later, the North Atlantic Squadron

The North Atlantic Squadron was a section of the United States Navy operating in the North Atlantic. It was renamed as the North Atlantic Fleet in 1902. In 1905 the European and South Atlantic squadrons were abolished and absorbed into the No ...

destroyed the majority of heavy Spanish naval units in the Caribbean in the Battle of Santiago de Cuba

The Battle of Santiago de Cuba was a decisive naval engagement that occurred on July 3, 1898 between an United States, American fleet, led by William T. Sampson and Winfield Scott Schley, against a Restoration (Spain), Spanish fleet led by Pascu ...

.

Rise of the modern Navy (1898–1914)

Fortunately for the New Navy, its most ardent political supporter, Theodore Roosevelt, became President in 1901. Under his administration, the Navy went from the sixth-largest in the world to second only to the Royal Navy.

Fortunately for the New Navy, its most ardent political supporter, Theodore Roosevelt, became President in 1901. Under his administration, the Navy went from the sixth-largest in the world to second only to the Royal Navy.Nicaraguan Canal

Attempts to build a canal across Nicaragua to connect the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean stretch back to the early colonial era. Construction of such a shipping route—using the San Juan River (Nicaragua), San Juan River as an access ro ...

, he purchased the failed French effort across the Isthmus of Panama

The Isthmus of Panama, historically known as the Isthmus of Darien, is the narrow strip of land that lies between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, linking North America, North and South America. The country of Panama is located on the i ...

. The isthmus was controlled by Colombia

Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country primarily located in South America with Insular region of Colombia, insular regions in North America. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Caribbean Sea to the north, Venezuel ...

, and in early 1903, the Hay–Herrán Treaty

The Hay–Herrán Treaty was a treaty signed on January 22, 1903, between United States Secretary of State John M. Hay of the United States and Tomás Herrán of Colombia. Had it been ratified, it would have allowed the United States a renewab ...

was signed by both nations to give control of the canal to the United States. After the Colombian Senate failed to ratify the treaty, Roosevelt implied to Panamanian rebels that if they revolted, the US Navy would help their cause for independence. Panama proceeded to proclaim its independence on November 3, 1903, and impeded interference from Colombia. The victorious Panamanians gave the United States control of the Panama Canal Zone

The Panama Canal Zone (), also known as just the Canal Zone, was a International zone#Concessions, concession of the United States located in the Isthmus of Panama that existed from 1903 to 1979. It consisted of the Panama Canal and an area gene ...

on February 23, 1904, for US$10 million.John Philip Holland

John Philip Holland (; February 24, 1841August 12, 1914) was an Irish marine engineer who developed the first submarine to be formally commissioned by the US Navy, USS Holland (SS-1) and the first Royal Navy submarine, ''Holland 1''.

Early lif ...

. His submarine, , was commissioned into U.S. Navy service in fall 1900.Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904 – 5 September 1905) was fought between the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major land battles of the war were fought on the ...

of 1905 and the launching of in the following year lent impetus to the construction program. At the end of 1907 Roosevelt had 16 new pre-dreadnought battleship

Pre-dreadnought battleships were sea-going battleships built from the mid- to late- 1880s to the early 1900s. Their designs were conceived before the appearance of in 1906 and their classification as "pre-dreadnought" is retrospectively appli ...

s to make up his "Great White Fleet

The Great White Fleet was the popular nickname for the group of United States Navy battleships that completed a journey around the globe from 16 December 1907, to 22 February 1909, by order of President Foreign policy of the Theodore Roosevelt ...

", which he sent on a cruise around the world. While nominally peaceful, and a valuable training exercise for the rapidly expanding Navy, it was also useful politically as a demonstration of United States power and capabilities; at every port, the politicians and naval officers of both potential allies and enemies were welcomed on board and given tours. The cruise had the desired effect, and American power was subsequently taken more seriously.

World War I (1914–1918)

Mexico

When United States agents discovered that the German merchant ship ''Ypiranga'' was carrying illegal arms to Mexico, President Wilson ordered the Navy to stop the ship from docking at the port of Veracruz. On April 21, 1914, a naval infantry brigade of 2,500 seamen, alongside a 1,300 man Marine Corps brigade, occupied Veracruz. During the battle, the naval brigade—which used outdated massed infantry tactics

Infantry tactics are the combination of military concepts and methods used by infantry to achieve tactical objectives during combat. The role of the infantry on the battlefield is, typically, to close with and engage the enemy, and hold territo ...

—proved less adept at urban combat

Urban warfare is warfare in urban areas such as towns and cities. Urban combat differs from combat in the open at both operational and the tactical levels. Complicating factors in urban warfare include the presence of civilians and the complex ...

than the marine brigade, which had embraced small unit tactics. This, combined with the unacceptability of risking increasingly valuable naval technical specialists in ground combat, resulted in Veracruz being the last large-scale use of U.S. sailors as landing infantry, leaving the Marine Corps to conduct amphibious assault

Amphibious warfare is a type of offensive military operation that today uses naval ships to project ground and air power onto a hostile or potentially hostile shore at a designated landing beach. Through history the operations were conducte ...

s.

A total of 55 Medals of Honor were awarded for acts of heroism at Veracruz, the largest number ever granted for a single action.

Preparing for war 1914–1917

Despite U.S. declarations of neutrality and German accountability for its unrestricted submarine warfare, in 1915 the British passenger liner ''Lusitania

Lusitania (; ) was an ancient Iberian Roman province encompassing most of modern-day Portugal (south of the Douro River) and a large portion of western Spain (the present Extremadura and Province of Salamanca). Romans named the region after th ...

'' was sunk, leading to calls for war.Naval Act of 1916

The Naval Act of 1916 was also called the "Big Navy Act" was United States federal legislation that called for vastly enlarging the United States Navy, US Navy. Woodrow Wilson, President Woodrow Wilson determined amidst the repeated incidents wit ...

that authorized a $500 million construction program over three years for 10 battleships, 6 battlecruisers, 10 scout cruisers, 50 destroyers and 67 submarines.Josephus Daniels

Josephus Daniels (May 18, 1862 – January 15, 1948) was a newspaper editor, Secretary of the Navy under President Woodrow Wilson, and U.S. Ambassador to Mexico under President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

He managed ''The News & Observer'' in R ...

, a pacifistic journalist, had built up the educational resources of the Navy and made its Naval War College

The Naval War College (NWC or NAVWARCOL) is the staff college and "Home of Thought" for the United States Navy at Naval Station Newport in Newport, Rhode Island. The NWC educates and develops leaders, supports defining the future Navy and associa ...

an essential experience for would-be admirals. However, he alienated the officer corps with his moralistic reforms (no wine in the officers' mess, no hazing at Annapolis, more chaplains and YMCAs). Ignoring the nation's strategic needs, and disdaining the advice of its experts, Daniels suspended meetings of the Joint Army and Navy Board for two years because it was giving unwelcome advice. He chopped in half the General Board's recommendations for new ships, reduced the authority of officers in the Navy yards where ships were built and repaired, and ignored the administrative chaos in his department. Bradley Fiske

Rear Admiral Bradley Allen Fiske (June 13, 1854 – April 6, 1942) was an officer in the United States Navy who was noted as a technical innovator. During his long career, Fiske invented more than a hundred and thirty electrical and mechanica ...