Types Riot on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Types Riot was the destruction of

The ruling elite of

The ruling elite of

It is not known who planned the riot. Members of the Family Compact approached John Lyons, the

It is not known who planned the riot. Members of the Family Compact approached John Lyons, the

Mackenzie was not confident that Robinson would pursue criminal charges against the perpetrators, so decided to sue the rioters in civil court for damaging his property. He hired

Mackenzie was not confident that Robinson would pursue criminal charges against the perpetrators, so decided to sue the rioters in civil court for damaging his property. He hired

William Lyon Mackenzie

William Lyon Mackenzie (March12, 1795 August28, 1861) was a Scottish-born Canadian-American journalist and politician. He founded newspapers critical of the Family Compact, a term used to identify the establishment of Upper Canada. He represe ...

's printing press and movable type

Movable type (US English; moveable type in British English) is the system and technology of printing and typography that uses movable Sort (typesetting), components to reproduce the elements of a document (usually individual alphanumeric charac ...

by members of the Family Compact

The Family Compact was a small closed group of men who exercised most of the political, economic and judicial power in Upper Canada (today's Ontario) from the 1810s to the 1840s. It was the Upper Canadian equivalent of the Château Clique in L ...

on June 8, 1826, in York, Upper Canada

York was a town and the second capital of the colony of Upper Canada. It is the predecessor to the Old Toronto, old city of Toronto (1834–1998). It was established in 1793 by Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe as a "temporary" location fo ...

(now known as Toronto). The Family Compact was the ruling elite of Upper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada () was a Province, part of The Canadas, British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North America, formerly part of the Province of Queb ...

who appointed themselves to positions of power within the Upper Canadian government. Mackenzie created the '' Colonial Advocate'' newspaper and published editorials

An editorial, or leading article (UK) or leader (UK), is an article or any other written document, often unsigned, written by the senior editorial people or publisher of a newspaper or magazine, that expresses the publication's opinion about ...

in the paper that accused the Family Compact of incompetence and profiteering on corrupt practices, offending the rioters. It is not known who planned the riot, although Samuel Jarvis

Samuel Peters Jarvis (November 15, 1792 – September 6, 1857) was a Canadian government official in the nineteenth century. He was the Chief Superintendent for the Indian Department in Upper Canada (1837–1845), and he was a member of the ...

, a government official, later claimed he organized the event. On the evening of June 8, nine to fifteen rioters forced their way into the newspaper offices and destroyed property. During the event, Mackenzie's employees tried to get passersby to help stop the rioters. Bystanders refused to help when they saw government officials such as William Allan and Stephen Heward

Like many early officials in Canada little is known of Stephen Heward beyond his roles as a public official in Upper Canada after serving earlier in the British Army.

Before and during his posting as Auditor General of Land Patents Heward held a ...

were watching the spectacle. When the rioters finished destroying the office, they took cases of type with them and threw them into the nearby bay.

Mackenzie sued the rioters for the damage to his property and lost business opportunities. The civil trial attracted substantial media attention, with several newspapers denouncing the government officials who failed to stop the riot. A jury awarded Mackenzie £625 to be paid by the defendants, a particularly harsh settlement. He used the event to highlight abuses of the Upper Canada government during his first campaign for election to the Parliament of Upper Canada

The Parliament of Upper Canada was the legislature for Upper Canada. It was created when the old Province of Quebec was split into Upper Canada and Lower Canada by the Constitutional Act of 1791.

As in other Westminster-style legislatures, it ...

, for which he was ultimately successful. Reformers

A reformer is someone who works for reform.

Reformer may also refer to:

* Catalytic reformer, in an oil refinery

*Methane reformer, producing hydrogen

* Steam reformer

* Hydrogen reformer, extracting hydrogen

*Methanol reformer, producing hydrogen ...

viewed Mackenzie as a martyr because of the destruction of his property, and he remained popular for several years. Historians identify the event as a sign of weakening Tory

A Tory () is an individual who supports a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalist conservatism which upholds the established social order as it has evolved through the history of Great Britain. The To ...

influence in Upper Canada politics.

Background

The ruling elite of

The ruling elite of Upper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada () was a Province, part of The Canadas, British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North America, formerly part of the Province of Queb ...

consisted of members of the Family Compact, who were descendants of Loyalist

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cr ...

families. Shortly after the War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

, they convinced the lieutenant-governor of the colony to appoint them to the unelected executive council and positions in the judicial system while occupying higher offices in the Anglican church

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

and the boards of financial institutions. They used their power to benefit themselves and their families economically. At the time, members of the Family Compact were also referred to as Tories

A Tory () is an individual who supports a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalist conservatism which upholds the established social order as it has evolved through the history of Great Britain. The T ...

, while modern-day historians sometimes refer to the group as Conservatives. Reformers

A reformer is someone who works for reform.

Reformer may also refer to:

* Catalytic reformer, in an oil refinery

*Methane reformer, producing hydrogen

* Steam reformer

* Hydrogen reformer, extracting hydrogen

*Methanol reformer, producing hydrogen ...

were the political opponents of the Family Compact. Journalists such as William Lyon Mackenzie

William Lyon Mackenzie (March12, 1795 August28, 1861) was a Scottish-born Canadian-American journalist and politician. He founded newspapers critical of the Family Compact, a term used to identify the establishment of Upper Canada. He represe ...

published newspapers that questioned the authority of the Tory ruling elite. The Family Compact tried to maintain their political power by attacking and disrupting Reformer political meetings.

In 1824, Mackenzie began publishing the '' Colonial Advocate'', a newspaper critical of the government and the Family Compact. The newspaper was a popular publication amongst people who were displeased with the administration of Upper Canada. Under the pseudonym "Patrick Swift", Mackenzie published articles that questioned the Family Compact's ability to run the colony and how they used their legal power to enrich themselves. For the ''Colonial Advocate''s second anniversary on May 18, 1826, Mackenzie published several negative stories on the history of Family Compact members. He accused female ancestors of the Family Compact of having many sexual partners and having been infected with syphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium ''Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms depend on the stage it presents: primary, secondary, latent syphilis, latent or tertiary. The prim ...

, and he criticized their personal appearance. On June 8, 1826, Mackenzie published an account of an 1817 duel between Samuel Jarvis

Samuel Peters Jarvis (November 15, 1792 – September 6, 1857) was a Canadian government official in the nineteenth century. He was the Chief Superintendent for the Indian Department in Upper Canada (1837–1845), and he was a member of the ...

, a Tory government official, and John Ridout John Ridout (1799-1817), still a teenager when he died in 1817, died in a duel with Samuel Jarvis. Both Ridout and Jarvis were from the small circle of privileged insiders called upon by the Lieutenant Governors of Upper Canada, to fill administra ...

, the son of a prominent Reformer, which resulted in Ridout's death. Jarvis considered this a personal attack on his character and commentary on a private matter.

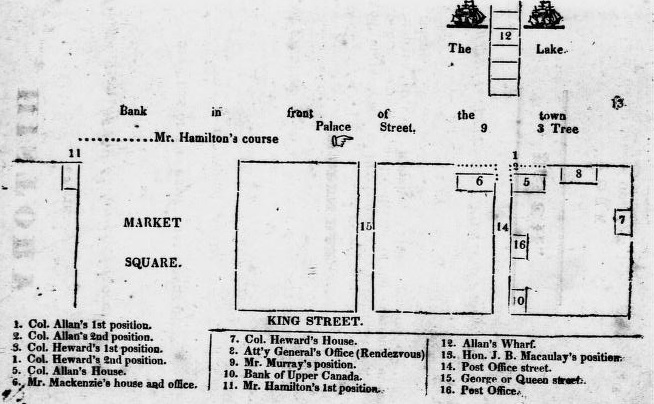

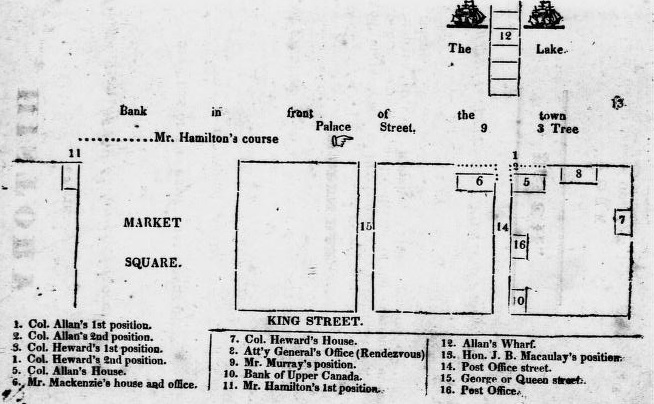

The ''Colonial Advocate''s printing press was located at the northwest corner of Palace Street and Frederick Street in York, Upper Canada

York was a town and the second capital of the colony of Upper Canada. It is the predecessor to the Old Toronto, old city of Toronto (1834–1998). It was established in 1793 by Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe as a "temporary" location fo ...

(now known as Toronto). Mackenzie lived there with his mother Elizabeth, his wife Isabel, and his children James and Elizabeth. Isabel's siblings, Margaret and James Baxter, were also living on the property and the latter was an apprentice of Mackenzie. Two other apprentices lived there, along with a journeyman named Charles French. Mackenzie travelled to Queenston

Queenston is a compact rural community and unincorporated place north of Niagara Falls in the Town of Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario, Canada. It is bordered by Highway 405 to the south and the Niagara River to the east; its location at the eponym ...

before the riot for unknown reasons and left his foreman, Ferguson, in charge of the press in his absence.

Riot

It is not known who planned the riot. Members of the Family Compact approached John Lyons, the

It is not known who planned the riot. Members of the Family Compact approached John Lyons, the lieutenant-governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a " second-in-com ...

's clerk, and encouraged him to plan an attack on Mackenzie's printing press. A few years after the incident, Jarvis claimed he had planned the riot. William Proudfoot testified at the civil trial that he heard Jarvis, Lyons, and Charles Richardson plan to ambush and attack Mackenzie. Raymond Baby stated that Charles Heward, the nephew of the attorney general

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general (: attorneys general) or attorney-general (AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have executive responsibility for law enf ...

, and Henry Sherwood

Henry Sherwood, (1807 – July 7, 1855) was a lawyer and Tory politician in the Province of Canada. He was involved in provincial and municipal politics. Born into a Loyalist family in Brockville in Augusta Township, Upper Canada, he stud ...

, the son of a judge, recruited him for the mob on the afternoon of the riot. Baby claimed they brought him to the attorney general's office, but several members of the mob denied this eighteen months after the trial concluded.

The riot began just after 6:00 pm on June 8, 1826. The exact number of rioters is uncertain; Jarvis reported there were nine or ten people, while a newspaper at the time reported fifteen participants. The rioters included Jarvis, Lyons, Richardson, Sherwood, Charles Baby, Raymond Baby, Charles Heward, Henry Heward, James King, and Peter McDougall. Several rioters brought clubs and sticks with them to aid in damaging the property. Some historians have stated that the men were dressed as indigenous people

There is no generally accepted definition of Indigenous peoples, although in the 21st century the focus has been on self-identification, cultural difference from other groups in a state, a special relationship with their traditional territ ...

, although newspaper accounts and published documents from the riot participants did not confirm this. Heather Davis-Fisch, a professor at the University of the Fraser Valley

The University of the Fraser Valley (UFV), formerly known as University College of the Fraser Valley and Fraser Valley College, is a public university with campuses in Abbotsford, British Columbia, Abbotsford, Chilliwack, Mission, British Columbi ...

, stated that this information was included in the ''Dictionary of Canadian Biography

The ''Dictionary of Canadian Biography'' (''DCB''; ) is a dictionary of biographical entries for individuals who have contributed to the history of Canada. The ''DCB'', which was initiated in 1959, is a collaboration between the University of Toro ...

'' without verification by the authors, possibly because it was a "cultural memory" of the event.

The rioters intended to attack Ferguson at the ''Colonial Advocate''s printing office; they believed Ferguson wrote the Patrick Swift editorials and wanted to retaliate against him. When the group was gathered, Jarvis sent Heward to the printing office to ascertain if Ferguson was there. The others followed shortly after, walking in single file and brandishing their weapons. When the men arrived at the printing press, they shouted, demanding to be let into the building. When no one responded, they forced their way in. Two apprentices, James Lumsden and James Baxter, immediately fled the house and shouted for help. When the rioters could not find Ferguson, they attacked the printing press. James and Elizabeth Mackenzie investigated the noise and discovered the rioters destroying property. Upset by the situation, Elizabeth left the house. The rioters intimidated the occupants of the house, scattered type

Type may refer to:

Science and technology Computing

* Typing, producing text via a keyboard, typewriter, etc.

* Data type, collection of values used for computations.

* File type

* TYPE (DOS command), a command to display contents of a file.

* ...

across the room and demolished the printing press. When a rioter announced the mob had done enough damage, they left carrying cases of type, which were thrown into the nearby bay.

A passerby heard Baxter's call for help, but did nothing because he saw William Allan and Stephen Heward

Like many early officials in Canada little is known of Stephen Heward beyond his roles as a public official in Upper Canada after serving earlier in the British Army.

Before and during his posting as Auditor General of Land Patents Heward held a ...

, two high-ranking administrators in Upper Canada, observing the riot and taking no action to stop it. Heward shouted encouragement to his sons to continue rioting while Allan watched from his property. Charles Ridout watched the riot from the bay and saw Heward and Allan were doing nothing to stop the mob. Other spectators gathered on a bank of a bay near the printing press. When Francis Collins, editor of the ''Canadian Freeman'', arrived at the printing office, he discovered the rioters had left and Elizabeth was distraught over the damage. He reported that Elizabeth feared the men would return to demolish the house.

Immediate aftermath

Independent newspaper editors throughout Upper Canada believed Allan and Heward's inaction during the riot meant the Upper Canadian government supported it. Collins denounced the destruction in the ''Canadian Freeman'' newspaper and criticized Allan and Heward, as policemagistrate

The term magistrate is used in a variety of systems of governments and laws to refer to a civilian officer who administers the law. In ancient Rome, a '' magistratus'' was one of the highest ranking government officers, and possessed both judi ...

s, for not doing anything to stop the riot. H. C. Thompson in the ''Upper Canada Herald'' criticized the rioters' connection to the Upper Canada Administration as an attack on the freedom of the press. James Macfarlane supported the rioters in the ''Kingston Chronicle'', stating they had no other recourse to the Swift editorials in the ''Colonial Advocate''. The ''Upper Canada Gazette'', the journal published by the public administration of Upper Canada, did not comment on the riot, furthering speculation that the government supported the event.

Members of the Upper Canada elite expressed their opinions in private letters. Anne Powell wrote the riot was the "most disgraceful scene" that had happened in York. She hoped her sons were not involved in the incident and forwarded the news to her husband in London. Robert Stanton said the rioters displayed their passion without restraint. When William Jarvis discovered his brother was involved in the riot, he wrote to him saying he wished Samuel had thrown Mackenzie into the bay, too.

Lieutenant-governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a " second-in-com ...

Peregrine Maitland

General Sir Peregrine Maitland, GCB (6 July 1777 – 30 May 1854) was a British army officer and colonial administrator. He also was a first-class cricketer from 1798 to 1808 and an early advocate for the establishment of what would become the C ...

was not in York during the riot and government officials did not comment on the event on his behalf. When Maitland returned to York two weeks later, he fired Lyons as his private secretary. He did not comment on the event publicly and did not report the incident to his superiors at the Colonial Office

The Colonial Office was a government department of the Kingdom of Great Britain and later of the United Kingdom, first created in 1768 from the Southern Department to deal with colonial affairs in North America (particularly the Thirteen Colo ...

. Attorney General John Robinson did not publicly condemn the attacks or admonish his employees who had participated in the riot. The dean of York attorneys, William Warren Baldwin

William Warren Baldwin (April 25, 1775 – January 8, 1844) was a medical doctor, businessman, lawyer, judge, architect and reform politician in Upper Canada. He, and his son Robert Baldwin, are recognized for having introduced the concept o ...

created a list of actions he felt highlighted Robinson's failure of duty as attorney general; Robinson's decision not to prosecute the rioters was first on that list.

Public opinion supported Mackenzie because of the government administrators' failure to stop the riot or charge the perpetrators. Mackenzie stayed away from York immediately after the riot because friends advised him his life might be in danger. He struggled financially for six months as the printing press was his source of income and he was responsible for boarding his apprentices. He had previously suffered from malarial fever and it returned due to the stress he suffered.

Civil trial

Trial details

Mackenzie was not confident that Robinson would pursue criminal charges against the perpetrators, so decided to sue the rioters in civil court for damaging his property. He hired

Mackenzie was not confident that Robinson would pursue criminal charges against the perpetrators, so decided to sue the rioters in civil court for damaging his property. He hired James Edward Small

James Edward Small, (February 1798 – May 27, 1869) was a lawyer, judge and political figure in Upper Canada and Canada West.

He was born in York, Upper Canada in 1798, the son of John Small. He attended the Home District School with Rob ...

as his attorney. Small issued writs addressed to "Jarvis et al." for a civil suit

A lawsuit is a proceeding by one or more parties (the plaintiff or claimant) against one or more parties (the defendant) in a civil court of law. The archaic term "suit in law" is found in only a small number of laws still in effect today. T ...

. Jarvis hired James Buchanan Macaulay

Colonel Sir James Buchanan Macaulay, CB (3 December 1793 – 26 November 1859) was a lawyer and judge in colonial Canada.

Early life

Macaulay, born at Newark, Upper Canada, 3 December 1793, was the second son of James Macaulay and Eliza ...

to defend him. Small proposed a settlement

Settlement may refer to:

*Human settlement, a community where people live

*Settlement (structural), downward movement of a structure's foundation

*Settlement (finance), where securities are delivered against payment of money

*Settlement (litigatio ...

of £2000 as the value of the destroyed printing press and type. Macaulay claimed the rioters were righteous in their actions and that the destroyed property was not worth £2000. He offered to settle for £200, then £300. Small rejected these offers, so the lawsuit went to trial

In law, a trial is a coming together of parties to a dispute, to present information (in the form of evidence) in a tribunal, a formal setting with the authority to adjudicate claims or disputes. One form of tribunal is a court. The tribunal, w ...

.

Jarvis, Lyons, Richardson, Charles Baby, Charles Heward, King, McDougall, and Sherwood were the defendant

In court proceedings, a defendant is a person or object who is the party either accused of committing a crime in criminal prosecution or against whom some type of civil relief is being sought in a civil case.

Terminology varies from one juris ...

s. Raymond Baby was not named as a defendant possibly because he was considered too young to be responsible for his actions, as he was 17 or 18. Henry Heward was named as a rioter but not as a defendant.

Marshall Spring Bidwell

Marshall Spring Bidwell (February 16, 1799 – October 24, 1872) was a lawyer and political figure in Upper Canada.

He was born in Stockbridge, Massachusetts in 1799, the son of politician Barnabas Bidwell. His family settled in Bath in Upper ...

represented Mackenzie at the trial, with Small's assistance. Christopher Alexander Hagerman

Christopher Alexander Hagerman, (28 March 1792 – 14 May 1847) was a Canadian militia officer, lawyer, administrator, politician and judge.

Early life and family

Known during his adult life as 'Handsome Kit', Hagerman was born at the Bay ...

represented the defendants. The trial took place in York's new courthouse; William Campbell presided. Allan was an associate judge during the proceedings. The defendants admitted they participated in the riot, so the jury was tasked with determining the amount of money Mackenzie should receive.

Hagerman insisted that the case be heard by a special jury A special jury, which is a jury selected from a special roll of persons with a restrictive qualification, could be used for civil or criminal cases, although in criminal cases only for misdemeanours such as seditious libel. The party opting for a ...

. The jury's foreman was Robert Rutherford, who owned a general store in York. The other two jurors from York were Edward Wright, a tailor, and George Shaw, a grocer. The remaining jurors were farmers from the surrounding towns of Whitby

Whitby is a seaside town, port and civil parish in North Yorkshire, England. It is on the Yorkshire Coast at the mouth of the River Esk, North Yorkshire, River Esk and has a maritime, mineral and tourist economy.

From the Middle Ages, Whitby ...

, Markham Markham may refer to:

Biology

* Markham's storm-petrel (''Oceanodroma markhami''), a seabird species found in Chile and Colombia

* Markham's grass mouse (''Abrothrix olivaceus markhami''), a rodent subspecies found on Wellington Island and the ne ...

, Scarborough Scarborough or Scarboro may refer to:

People

* Scarborough (surname)

* Earl of Scarbrough

Places Australia

* Scarborough, Western Australia, suburb of Perth

* Scarborough, New South Wales, suburb of Wollongong

* Scarborough, Queensland, sub ...

, and Vaughan

Vaughan ( ) (2022 population 344,412) is a city in Ontario, Canada. It is located in the Regional Municipality of York, just north of Toronto. Vaughan was the fastest-growing municipality in Canada between 1996 and 2006 with its population increa ...

, and included Jacob Boyer, a German immigrant; and Joseph Tomlinson, who became an agent for the ''Colonial Advocate'' after the trial.

Arguments and jury deliberations

Bidwell argued Mackenzie should be awarded a larger settlement because of the damaged property's value and Mackenzie's inability to fulfill printing contracts after his printing press was destroyed. He stated the rioters violated all Englishmen's rights to a free press and that the law should decide the morality and legality of a newspaper, not a mob. Bidwell also argued that the defendants should have used their social standing and education to find a peaceful solution instead of using violence. He also accused the defendants of violating Mackenzie's privacy by damaging his home, which was on the same property as the printing press. Elizabeth Mackenzie was the first witness for the plaintiff and described the attack from inside the property, although she could not identify any perpetrators. William Lyon Mackenzie's five employees identified the rioters and explained the business's finances to showcase the lost income from the riot. Hagerman did not want the jury to sympathize with Mackenzie, so he questioned the employees about his character and the ''Colonial Advocate''s negative reputation. These questions confirmed Mackenzie wrote the Patrick Swift editorials. The ''Upper Canada Herald'' printed Hagerman's 4,400-word address to the jury. He suggested the trial was about Mackenzie's conduct. He claimed Mackenzie was exaggerating the financial cost of the damage and was using the lawsuit to prevent bankruptcy because the ''Colonial Advocate'' was unsuccessful. Hagerman emphasized that the Swift editorials damaged the reputations of living and deceased people and the right to free press was not supposed to protect slanderous writers like Mackenzie. He stated the rioters wanted to protect decency in Upper Canada and did not physically harm anyone. Although Hagerman admitted the rioters damaged some property, he claimed Mackenzie was not entitled to the sums of money he was suing for. The defendants did not testify during the trial because Hagerman did not want them to be cross-examined about who had planned, recruited, and executed the attack. He also wanted the jury to focus on Mackenzie's conduct, not on that of the defendants. Campbell gave instructions to the jury that summarized the evidence of the trial. Mary Jarvis, Samuel Jarvis's wife thought the instructions favoured the defendants, but newspapers at the time did not think the instructions were noteworthy. The jury deliberated for thirty hours, debating the amount of money Mackenzie should be rewarded. Juror George Shaw did not want to award Mackenzie any damages and argued that previous case law indicated they should dismiss the case. Three jurors became sick during the deliberations. Jacob Boyer hadbloodletting

Bloodletting (or blood-letting) was the deliberate withdrawal of blood from a patient to prevent or cure illness and disease. Bloodletting, whether by a physician or by leeches, was based on an ancient system of medicine in which blood and othe ...

administered to him, but refused to be dismissed from the jury. After further discussion, the jury awarded Mackenzie £625 () in damages, a particularly harsh verdict.

Aftermath

The damages awarded to Mackenzie surprised Mary Jarvis, as she believed it was a modest amount of money.James Baby

James Duperon Bâby (August 25, 1763 – February 19, 1833) was a judge and political figure in Upper Canada.

Biography

He was born Jacques Bâby, the son of Jacques Bâby dit Duperon, to a prosperous family in Detroit in 1763. His last na ...

reprimanded Charles as he paid his son's share of the settlement. James FitzGibbon

James FitzGibbon (16 November 1780 – 10 December 1863) was a public servant, prominent freemason of the masonic lodge from 1822 to 1826 (holding the highest position in Upper Canada of deputy provincial grand master), member of the Family ...

, a colonel in Upper Canada, solicited donations from riot supporters and government administrators. In 1827, Collins reported on this donation scheme and accused Maitland of donating funds. FitzGibbon confirmed he solicited funds but denied Maitland donated money. Opponents of the government speculated FitzGibbon was appointed as clerk of the Legislative Assembly and colonel of the militia as a reward for organizing this collection. FitzGibbon reacted to these accusations by sending a letter to the lieutenant-governor accusing Mackenzie of instigating the riot to increase his popularity and save his printing business.

Mackenzie used the settlement to pay his creditors, buy new printing equipment and restart production of the ''Colonial Advocate''. Before the riot, the newspaper was struggling financially and might have ceased operations; the settlement helped the paper stay financially feasible. In 1827, he published his account of the incident as ''The History of the Destruction of the Colonial Advocate Press''. Mackenzie also used the settlement to fund his first campaign for a seat in the Upper Canada Legislature for the County of York in July 1828, for which he was elected.

Jarvis was listed first as a defendant in the lawsuit and used this to promote his social status among the governing elite. He declared he was the leader of the mob and refused to talk about or publish material that damaged the reputation of the persons involved, including government administrators. Two years after the riot, Jarvis printed a pamphlet called ''A Statement of Facts Relating to the Trespass on the Printing Press in the Possession of William Lyon Mackenzie'', in which he claimed to have organized the event. Jarvis said the riot's purpose was to preserve the power structure of Upper Canada and stop social change. Jarvis's publication included a sworn statement from all the defendants that government officials had no involvement in the planning or implementation of the riot.

Newspapers that opposed Upper Canadian government officials believed the riot was another example of the government eliminating opposition to its power. Collins stated in the ''Canadian Freeman'' that he supported Mackenzie's settlement and denounced the riot. Those who supported the administration believed the rioters overreacted to Mackenzie's provocative Patrick Swift editorials. Robert Stanton of the ''Upper Canada Gazette'' decried the settlement Mackenzie received, believing the damage to his printing press was exaggerated. Most independent newspapers supported Mackenzie, and the amount awarded to him.

Criminal trial

Mackenzie did not seek criminal charges because he thought Robinson, who would have led the prosecution in a criminal case, would not pursue the charges rigorously. Robinson stated he did not pursue criminal charges because it was customary for the victim to choose if a civil or criminal trial should be held, and Mackenzie chose a civil trial. The defendants' supporters wanted Robinson to pursue a criminal trial because they thought it would reduce the amount of money Mackenzie would be awarded in the civil trial. Robinson declined to pursue charges during the civil trial to avoid accusations of interfering with proceedings. After the trial, Mackenzie declined Robinson's offer to pursue criminal charges. Mackenzie later claimed that his lawyers advised him not to pursue criminal charges because Robinson was biased in favour of the defendants. Francis Collins was charged with libel for his articles on the Jarvis-Ridout duel. At his criminal trial in April 1828, he accused Robinson of neglecting his duty by charging him for libel while refusing to charge the perpetrators of other crimes, including the rioters in the Types Riot. JudgeJohn Walpole Willis

John Walpole Willis (4 January 1793 – 10 September 1877) was a British judge of Upper Canada, British Guiana (as acting Chief Justice), the Supreme Court of New South Wales, and resident judge at Port Phillip, Melbourne.

Early life

The s ...

agreed with Collins and threatened to report Robinson's conduct to the British government. A few days later Robinson initiated criminal proceedings against the perpetrators of the Types Riot, the same individuals named in the civil suit. The criminal trial began later that day.

According to Jarvis, the criminal trial was orchestrated to force Mackenzie to testify in the proceedings. The defendants' witnesses testified Mackenzie told them he exaggerated the damage. Mackenzie testified the physical damage was £12 but the amount he claimed in the civil trial included money he lost in printing contracts because his press was damaged. The jury quickly decided the men were guilty. The judge determined the defendants had already paid a large settlement after the civil trial and fined each of them five shillings

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 12 pence ...

.

Legacy

The Types Riot inspired Mackenzie to continue his fight to dismantle the Upper Canada power structure dominated by the Family Compact. A year after the incident, he used the riot to highlight abuses of power by government authorities and criticized Allan and Heward's appointment as barristers-at-law. The event was highlighted during his successful campaign to become a legislator in the Upper Canada Parliament, claiming that government officials had betrayed the public's trust by instigating the riot. He also used the event to show electors he was part of a group of citizens who struggled to reform the political system of Upper Canada. The riot led to Mackenzie becoming a martyr amongReformers

A reformer is someone who works for reform.

Reformer may also refer to:

* Catalytic reformer, in an oil refinery

*Methane reformer, producing hydrogen

* Steam reformer

* Hydrogen reformer, extracting hydrogen

*Methanol reformer, producing hydrogen ...

, the political group that campaigned against the Family Compact, and Mackenzie remained popular for several years.

After the Types Riot, the youth of York divided themselves into an upper class of people related to the government administrators and a lower class composed of mechanics and labourers. These groups avoided interacting and distrusted each other's actions. Samuel Jarvis claimed the riot exposed the differing political philosophies of those born and raised in Upper Canada who supported the ruling elite and immigrants who believed in changing the political system towards British radicalism or American egalitarianism

Egalitarianism (; also equalitarianism) is a school of thought within political philosophy that builds on the concept of social equality, prioritizing it for all people. Egalitarian doctrines are generally characterized by the idea that all hum ...

.

Historian Carol Wilton described the Types Riot and its subsequent civil trial as "the most important debate in Upper Canadian legal history". According to Wilton, the riot showed an upper class without an understanding of the rule of law who wanted to preserve their society. Although Tory-aligned historians believe Mackenzie's reward in the lawsuit showed an impartial court, other historians believe this event highlighted the maladministration of Upper Canada. The riot showed a willingness of the Upper Canadian elite to ignore the laws that placed them in positions of power. Wilton stated the event should be analyzed as part of a larger campaign of conservative political attacks that includes the violence of Reform meetings in the 1830s.

The violence that occurred in Upper Canada in the 1820s and 1830s, including the Types Riot, showed the weakening conservative dominance in the province's politics. It demonstrated that the Family Compact's claim to authority, based on their education and upbringing, was supported by threats of uncivilized violence. Reformers used the riot to support their theory of persecution by the Tory elite. Government prosecutors' refusal to charge the defendants in a criminal case showed that the ruling class would prevent opposition to their power. It convinced citizens that violence against the government was acceptable because the government would not stop attacks against dissenters. The civil trial's verdict scared the Tory elite, as the judicial system could hold them accountable for their actions. They started using legal maneuvers to protect their property and assets. The Types Riot was the first instance of violence against reformers that led to the Upper Canada Rebellion

The Upper Canada Rebellion was an insurrection against the Oligarchy, oligarchic government of the British colony of Upper Canada (present-day Ontario) in December 1837. While public grievances had existed for years, it was the Lower Canada Rebe ...

and continued until the 1840s.

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{Authority control 1826 crimes in Canada 1826 in Upper Canada 1826 riots Attacks on commercial buildings in Canada Attacks on mass media offices Events relating to freedom of expression Freedom of expression in Canada History of mass media in Canada June 1826