Tudor London on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Tudor period in London started with the beginning of the reign of Henry VII in 1485 and ended in 1603 with the death of

Immigrants arrived in London not just from all over England and Wales, but from abroad as well. In 1563, the total of foreigners in London was estimated at 4,543, by 1568 it was 9,302 and by 1583 there was 5,141. Nearly 25% of foreigners lived in villages outside London, inside the city French hatters stayed in

Immigrants arrived in London not just from all over England and Wales, but from abroad as well. In 1563, the total of foreigners in London was estimated at 4,543, by 1568 it was 9,302 and by 1583 there was 5,141. Nearly 25% of foreigners lived in villages outside London, inside the city French hatters stayed in

The Thames is the main river in London, and its main trade route to Europe and the wider world. It was both wider and shallower than it is today, and in 1564 it froze over so completely that Elizabeth I and her courtiers held an archery practice on the ice. In this period, there was only one bridge-

The Thames is the main river in London, and its main trade route to Europe and the wider world. It was both wider and shallower than it is today, and in 1564 it froze over so completely that Elizabeth I and her courtiers held an archery practice on the ice. In this period, there was only one bridge-

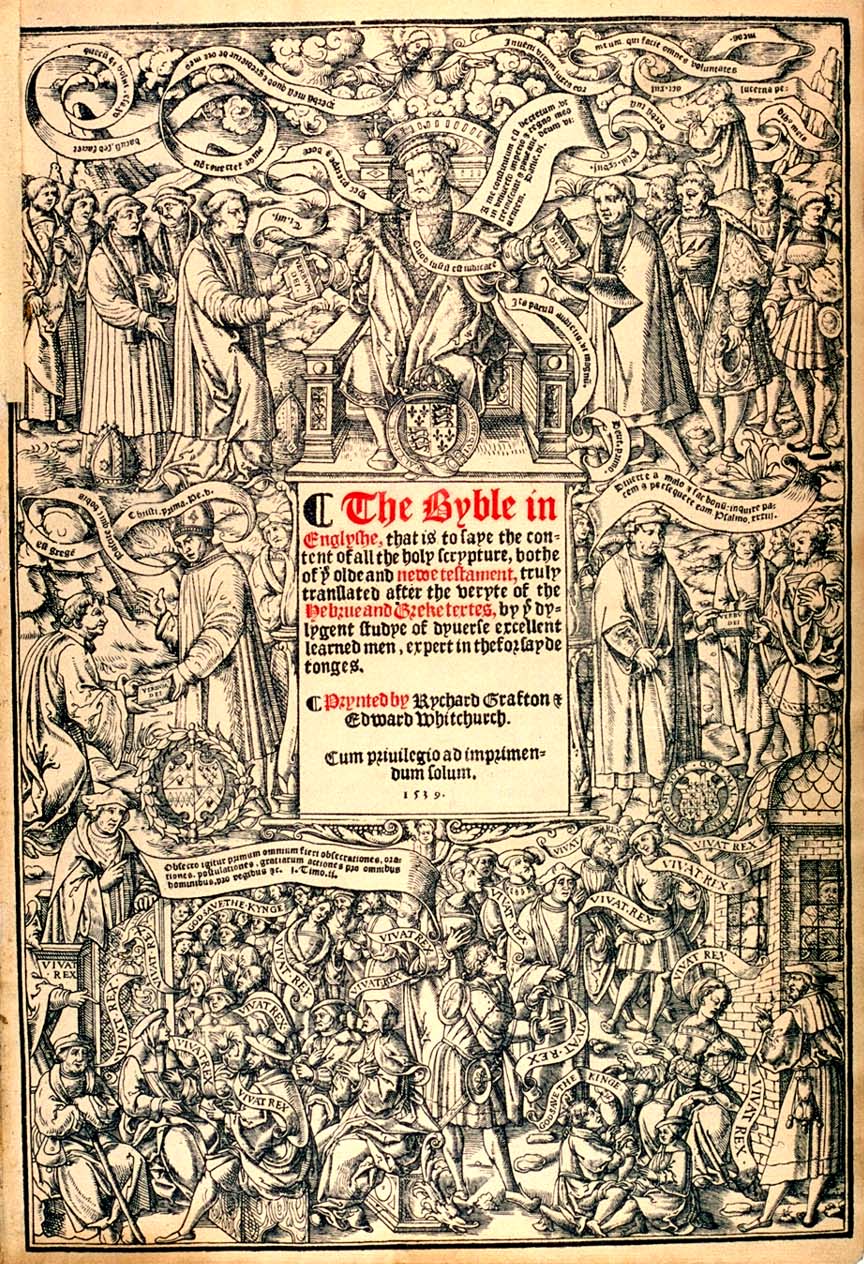

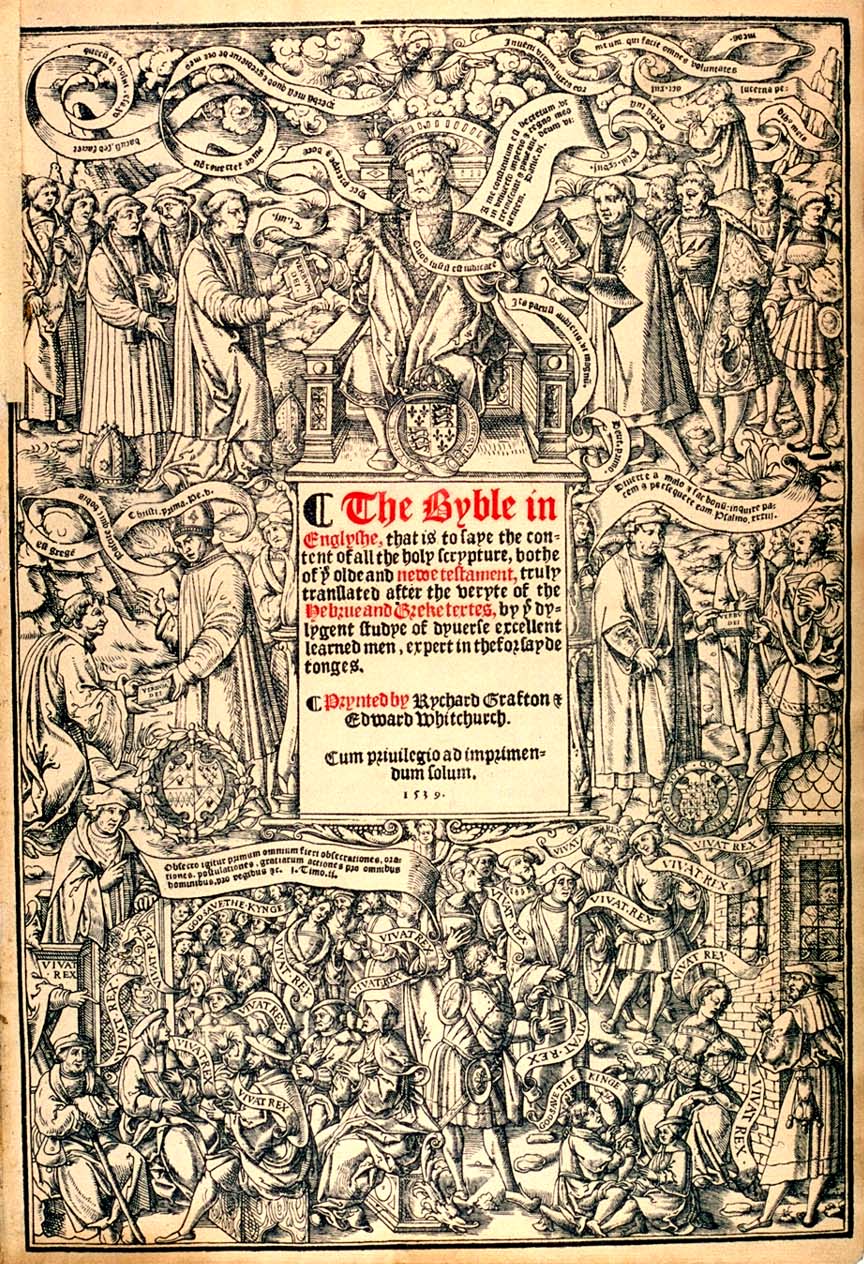

In 1535, an officially sanctioned English Bible was published. In 1539, six copies of the Great Bible were placed in St. Paul's Cathedral where anyone could read them or read them aloud to others. Churches were also physically reformed, with jewels, rood lofts and statues of saints being removed. Sometimes these were taken down by officials, but in other churches, such as St. Margaret Pattens, reformist mobs destroyed these objects. Under Edward VI, Protestant reforms were made such as the abolition of chantry chapels and the removal of saints' images and

In 1535, an officially sanctioned English Bible was published. In 1539, six copies of the Great Bible were placed in St. Paul's Cathedral where anyone could read them or read them aloud to others. Churches were also physically reformed, with jewels, rood lofts and statues of saints being removed. Sometimes these were taken down by officials, but in other churches, such as St. Margaret Pattens, reformist mobs destroyed these objects. Under Edward VI, Protestant reforms were made such as the abolition of chantry chapels and the removal of saints' images and

Prior to the Reformation, hospitals were run by monastic institutions. At the beginning of the period, London had five principal hospitals, totalling somewhere between 350 and 400 beds. They were St. Bartholomew's in Smithfield; St. Thomas' in Southwark; St. Mary-without-Bishopsgate, which specialised in maternity care; St. Elsyng Spital, which specialised in the homeless blind; and St. Mary Bethlehem, commonly known as Bedlam, which specialised in mental illness. Many of these hospitals also functioned as shelters for the homeless or the infirm. In 1505, Henry VII founded St. John the Baptist's Hospital on the site of the Savoy Palace. These were all dissolved in the Reformation, and mostly given over to the city to re-establish them as secular hospitals, except for St. Mary-without-Bishopsgate and St. Elsying Spital, which were permanently closed. The estate of the Savoy Hospital was given to St. Thomas'.

Individual physicians and surgeons may have received a medical degree from a university or had been granted a licence after taking an apprenticeship, however many were completely unlicensed. By the end of the period, there was a medical practitioner (a physician, surgeon or apothecary) for every 400 people in London.

Outside the city, there were leper hospitals from at least 1500 at

Prior to the Reformation, hospitals were run by monastic institutions. At the beginning of the period, London had five principal hospitals, totalling somewhere between 350 and 400 beds. They were St. Bartholomew's in Smithfield; St. Thomas' in Southwark; St. Mary-without-Bishopsgate, which specialised in maternity care; St. Elsyng Spital, which specialised in the homeless blind; and St. Mary Bethlehem, commonly known as Bedlam, which specialised in mental illness. Many of these hospitals also functioned as shelters for the homeless or the infirm. In 1505, Henry VII founded St. John the Baptist's Hospital on the site of the Savoy Palace. These were all dissolved in the Reformation, and mostly given over to the city to re-establish them as secular hospitals, except for St. Mary-without-Bishopsgate and St. Elsying Spital, which were permanently closed. The estate of the Savoy Hospital was given to St. Thomas'.

Individual physicians and surgeons may have received a medical degree from a university or had been granted a licence after taking an apprenticeship, however many were completely unlicensed. By the end of the period, there was a medical practitioner (a physician, surgeon or apothecary) for every 400 people in London.

Outside the city, there were leper hospitals from at least 1500 at

At the beginning of the period, theatre in London mostly took the form of miracle plays based on Biblical stories. However, during the reign of Elizabeth I, these were banned for being too Catholic, and secular plays performed by travelling companies became popular instead. These companies began by performing at galleried coaching inns and upper-class houses before beginning to build their own permanent theatres in London, the first known example being the Red Lion in

At the beginning of the period, theatre in London mostly took the form of miracle plays based on Biblical stories. However, during the reign of Elizabeth I, these were banned for being too Catholic, and secular plays performed by travelling companies became popular instead. These companies began by performing at galleried coaching inns and upper-class houses before beginning to build their own permanent theatres in London, the first known example being the Red Lion in

Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudo ...

. During this period, the population of the city grew enormously, from about 50,000 at the end of the 15th century to an estimated 200,000 by 1603, over 13 times that of the next-largest city in England, Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of the county of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. It lies by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. The population of the Norwich ...

. The city also expanded to take up more physical space, further exceeding the bounds of its old medieval walls to reach as far west as St. Giles by the end of the period. In 1598, the historian John Stow called it "the fairest, largest, richest and best inhabited city in the world".

Topography

The area within the medieval walls, known as the City of London, featured timber-framed houses, often with upper storeys jutting out over the pavement. Two such surviving London houses from this period include the King's House inside theTower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic citadel and castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamle ...

, and Staple Inn

Staple Inn is a part-Tudor period, Tudor building on the south side of High Holborn street in the City of London, London, England. Located near Chancery Lane tube station, it is used as the London venue for meetings of the Institute and Faculty ...

. During this period, London grew outside the old City boundaries. In futile attempts to check urban sprawl

Urban sprawl (also known as suburban sprawl or urban encroachment) is defined as "the spreading of urban developments (such as houses and shopping centers) on undeveloped land near a city". Urban sprawl has been described as the unrestricted ...

, repeated ordnances forbade the building of new houses on less than of ground in 1580, 1583, and 1593, applying to land as far as Chiswick

Chiswick ( ) is a district in West London, split between the London Borough of Hounslow, London Boroughs of Hounslow and London Borough of Ealing, Ealing. It contains Hogarth's House, the former residence of the 18th-century English artist Wi ...

or Tottenham

Tottenham (, , , ) is a district in north London, England, within the London Borough of Haringey. It is located in the Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county of Greater London. Tottenham is centred north-northeast of Charing Cross, ...

. These laws had the unintended consequence that landlords within the medieval walls began subdividing their buildings as much as possible, and landowners outside the walls were encouraged not to build well, but to build quickly and surreptitiously. In 1605, just after the end of the period, it has been estimated that 75,000 people lived in the City of London

The City of London, also known as ''the City'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county and Districts of England, local government district with City status in the United Kingdom, city status in England. It is the Old town, his ...

while 115,000 in the surrounding " liberties", such as St. Martin's-le-Grand, Blackfriars, Whitefriars, etc.

The East End of London developed during this period, due to enclosure

Enclosure or inclosure is a term, used in English landownership, that refers to the appropriation of "waste" or "common land", enclosing it, and by doing so depriving commoners of their traditional rights of access and usage. Agreements to enc ...

s driving farmers off their land and into cities, and the lack of oversight from London's guilds, allowing businesses to continue without regulation. The topographer and city historian John Stow recalled that Petticoat Lane in his youth had run among fields, flanked with hedgerows, but had become "a continual building of garden houses and small cottages" and Wapping

Wapping () is an area in the borough of Tower Hamlets in London, England. It is in East London and part of the East End. Wapping is on the north bank of the River Thames between Tower Bridge to the west, and Shadwell to the east. This posit ...

"a continual street or filthy straight passage with alleys of small tenements". By the end of the period, Whitechapel

Whitechapel () is an area in London, England, and is located in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is in east London and part of the East End of London, East End. It is the location of Tower Hamlets Town Hall and therefore the borough tow ...

had transformed from a rural area to a hive of industry, with tanneries, slaughterhouses, breweries and foundries.

The first maps of London were made in this period. One is by George Hoefnagel and Frans Hogenberg. It was published in 1572, but shows the city as it was around 1550. The Agas map, attributed to the surveyor Ralph Agas, was made around 1561. John Norden made maps of the City and Westminster in his '' Speculum Britanniae'' in 1593. In 1598, John Stow published his ''Survey of London'', a thorough topographical and historical description of the city.

Palaces and mansions

The number of royal palaces in London expanded dramatically in this period, mostly due to building efforts underHenry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

. Several palaces that existed prior to the period were also enlarged. The Palace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster is the meeting place of the Parliament of the United Kingdom and is located in London, England. It is commonly called the Houses of Parliament after the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two legislative ch ...

was severely damaged by fire in 1512, and ceased to be a home for the royal family, being instead used as offices or chambers for the monarch to summon Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

. The Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic citadel and castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamle ...

was used as a place from which Tudor monarchs processed to Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

for their coronations, and as a place of imprisonment and execution, notably of high-ranking prisoners such as Anne Boleyn

Anne Boleyn (; 1501 or 1507 – 19 May 1536) was List of English royal consorts, Queen of England from 1533 to 1536, as the Wives of Henry VIII, second wife of King Henry VIII. The circumstances of her marriage and execution, by beheading ...

, Catherine Howard, and Lady Jane Grey

Lady Jane Grey (1536/1537 – 12 February 1554), also known as Lady Jane Dudley after her marriage, and nicknamed as the "Nine Days Queen", was an English noblewoman who was proclaimed Queen of England and Ireland on 10 July 1553 and reigned ...

. 48 known cases of torture took place here between 1540 and 1640. Eltham Palace

Eltham Palace is a large house at Eltham ( ) in southeast London, England, within the Royal Borough of Greenwich. The house consists of the medieval great hall of a former royal residence, to which an Art Deco extension was added in the 193 ...

was the childhood home of Henry VIII, where he was taught music and languages by his tutor, John Skelton. He had it enlarged between 1519 and 1522. Shene Palace burned down in 1497 and was rebuilt under Henry VII as Richmond Palace

Richmond Palace was a Tudor royal residence on the River Thames in England which stood in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Situated in what was then rural Surrey, it lay upstream and on the opposite bank from the Palace of Westminste ...

, featuring gilded domes and pinnacles. Both Henry VII and Elizabeth I died there. Greenwich Palace was also rebuilt under Henry VII; and Henry VIII, Mary I, and Elizabeth I were born there.

Hampton Court Palace

Hampton Court Palace is a Listed building, Grade I listed royal palace in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, southwest and upstream of central London on the River Thames. Opened to the public, the palace is managed by Historic Royal ...

was built by Henry VIII's advisor, Thomas Wolsey

Thomas Wolsey ( ; – 29 November 1530) was an English statesman and Catholic cardinal (catholic), cardinal. When Henry VIII became King of England in 1509, Wolsey became the king's Lord High Almoner, almoner. Wolsey's affairs prospered and ...

, and acquired in 1529 by Henry, who set about turning it into a sprawling pleasure palace, with tennis courts, bowling alleys, a tiltyard, Great Kitchens and a Great Hall. It is where his third wife, Jane Seymour

Jane Seymour (; 24 October 1537) was Queen of England as the third wife of King Henry VIII from their marriage on 30 May 1536 until her death the next year. She became queen following the execution of Henry's second wife, Anne Boleyn, who was ...

, died; where his son, Edward VI, was born; and where he married his sixth wife, Catherine Parr

Catherine Parr ( – 5 September 1548) was Queen of England and Ireland as the last of the six wives of King Henry VIII from their marriage on 12 July 1543 until Henry's death on 28 January 1547. Catherine was the final queen consort o ...

. Henry also acquired York Place from Wolsey, which he massively enlarged into Whitehall Palace, with a tiltyard and tennis court, and a royal mews for horses, carriages and hunting falcons close to Charing Cross

Charing Cross ( ) is a junction in Westminster, London, England, where six routes meet. Since the early 19th century, Charing Cross has been the notional "centre of London" and became the point from which distances from London are measured. ...

. It was where he died in 1547. In 1531, Henry seized the St. James monastic leper

Leprosy, also known as Hansen's disease (HD), is a long-term infection by the bacteria '' Mycobacterium leprae'' or '' Mycobacterium lepromatosis''. Infection can lead to damage of the nerves, respiratory tract, skin, and eyes. This nerve da ...

hospital to rebuild as St. James's Palace, and he had Nonsuch Palace built in 1538. In 1543, Henry gave Chelsea Manor House to his sixth wife Catherine Parr, where she would continue to reside after his death in 1547. In the same year, he had the Great Standing built in his hunting grounds at Epping Forest

Epping Forest is a area of ancient woodland, and other established habitats, which straddles the border between Greater London and Essex. The main body of the forest stretches from Epping in the north, to Chingford on the edge of the Lond ...

.

From 1515, Henry VIII had Bridewell Palace built outside the City walls; in 1553, Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and King of Ireland, Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. The only surviving son of Henry VIII by his thi ...

gave it to the City of London to be converted into a workhouse

In Britain and Ireland, a workhouse (, lit. "poor-house") was a total institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. In Scotland, they were usually known as Scottish poorhouse, poorh ...

, the first such institution in Europe. Its officers were given the authority to roam alehouses, cock-fighting pits, gambling dens and skittle-alleys, seizing homeless, unemployed or disorderly people and detaining them in Bridewell.

Westminster Abbey owned a large estate in Hampstead where the mansion Belsize House was built some time before 1550. The Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

had the gatehouse to his Lambeth Palace

Lambeth Palace is the official London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury. It is situated in north Lambeth, London, on the south bank of the River Thames, south-east of the Palace of Westminster, which houses Parliament of the United King ...

completed in 1501, and the Bishop of London

The bishop of London is the Ordinary (church officer), ordinary of the Church of England's Diocese of London in the Province of Canterbury. By custom the Bishop is also Dean of the Chapel Royal since 1723.

The diocese covers of 17 boroughs o ...

rebuilt his main manor house, Fulham Palace

Fulham Palace lies on the north bank of the River Thames in Fulham, London, previously in the former English county of Middlesex. It is the site of the Manor of Fulham dating back to Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, Saxon times and in the c ...

, from 1510. In 1514, the manor of Tottenham

Tottenham (, , , ) is a district in north London, England, within the London Borough of Haringey. It is located in the Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county of Greater London. Tottenham is centred north-northeast of Charing Cross, ...

was bought by William Compton, who rebuilt Bruce Castle. Along the Strand was a series of mansions, including Somerset House

Somerset House is a large neoclassical architecture, neoclassical building complex situated on the south side of the Strand, London, Strand in central London, overlooking the River Thames, just east of Waterloo Bridge. The Georgian era quadran ...

, Hungerford House, the Savoy Palace, Arundel Place, Cecil House, and Durham Place, where Lady Jane Grey

Lady Jane Grey (1536/1537 – 12 February 1554), also known as Lady Jane Dudley after her marriage, and nicknamed as the "Nine Days Queen", was an English noblewoman who was proclaimed Queen of England and Ireland on 10 July 1553 and reigned ...

married Guildford Dudley in 1553. Many of these were the houses of bishops or abbots at the beginning of the period, but transferred into the hands of secular aristocrats in the 1530s and 1540s. The chancellor Thomas More had a mansion built in Chelsea, in which he lived in the 1520s. Eastbury Manor House near Barking was constructed 1556–1578 for Clement Sysley. Thomas Gresham had Osterley Park built around 1576, and Christopher Hatton had Hatton House built in Holborn

Holborn ( or ), an area in central London, covers the south-eastern part of the London Borough of Camden and a part (St Andrew Holborn (parish), St Andrew Holborn Below the Bars) of the Wards of the City of London, Ward of Farringdon Without i ...

in 1577. The London merchant Richard Awsiter had a manor house built in Southall in Ealing

Ealing () is a district in west London (sub-region), west London, England, west of Charing Cross in the London Borough of Ealing. It is the administrative centre of the borough and is identified as a major metropolitan centre in the London Pl ...

in 1587.

Other building work

Lincoln's Inn Hall was built 1489–1492, and was frequented by the politician and lawyerThomas More

Sir Thomas More (7 February 1478 – 6 July 1535), venerated in the Catholic Church as Saint Thomas More, was an English lawyer, judge, social philosopher, author, statesman, theologian, and noted Renaissance humanist. He also served Henry VII ...

. Henry VII had the Henry VII Chapel

The Henry VII Lady Chapel, now more often known just as the Henry VII Chapel, is a large Lady chapel at the far eastern end of Westminster Abbey, England, paid for by the will of King Henry VII. It is separated from the rest of the abbey by br ...

added to Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

between 1503 and 1510, and is buried inside with his wife, Elizabeth of York

Elizabeth of York (11 February 1466 – 11 February 1503) was List of English royal consorts, Queen of England from her marriage to King Henry VII of England, Henry VII on 18 January 1486 until her death in 1503. She was the daughter of King E ...

. His grandchildren, Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and King of Ireland, Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. The only surviving son of Henry VIII by his thi ...

, Mary I

Mary I (18 February 1516 – 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and Queen of Spain as the wife of King Philip II from January 1556 until her death in 1558. She made vigorous a ...

and Elizabeth I, were also later buried inside. The gatehouse to St. John Clerkenwell priory was completed in 1504, and still stands today. The Prospect of Whitby pub, then known as the Devil's Tavern, was supposedly built in 1520 on Wapping Wall. In 1561, lightning struck Old St Paul's Cathedral

Old St Paul's Cathedral was the cathedral of the City of London that, until the Great Fire of London, Great Fire of 1666, stood on the site of the present St Paul's Cathedral. Built from 1087 to 1314 and dedicated to Paul of Tarsus, Saint Paul ...

. The roof was repaired, but the spire was never replaced. Middle Temple Hall was built around 1570 and was frequented by Elizabeth I.

Disasters often necessitated rebuilding work: great fires are recorded in 1485, 1504, 1506, and 1538. In 1506, a great storm blew off tiles on houses and the weathervane on top of St. Paul's Cathedral. In 1544, 1552, 1560 and 1583, stores of gunpowder exploded in London, often killing several people as well as damaging buildings. In April 1580 there was some damage to chimneys and walls in the Dover Straits earthquake of 1580.

Demography

At the end of the 15th century, London's population has been estimated at 50,000. By 1603, that number ballooned to an estimated 200,000, over 13 times that of the next-largest city in England,Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of the county of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. It lies by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. The population of the Norwich ...

. Between 1523 and 1527, a national tax was levied which yielded £16,675 from the inhabitants of London, more than the total amount yielded from the next 29 cities in England.

Most Londoners married in their early or mid-twenties. Families who lived around Cheapside had four children on average, but in the poorer area of Clerkenwell, the average was only two and a half. It is estimated that half of all children did not reach the age of 15. The average height for male Londoners was and the average height for female Londoners was .

Plague hit so badly in 1563 in London that the local authorities began to compile death statistics for the first time in the Bills of Mortality. In that year, 20,372 were recorded dead in London across the whole year, 17,404 of whom died of the plague. Some years were much less dangerous: in 1582, only 6,930 deaths were recorded, of which 3,075 were from the plague, but in 1603 the total was 40,040, of which 32,257 died of the plague.

Immigrants arrived in London not just from all over England and Wales, but from abroad as well. In 1563, the total of foreigners in London was estimated at 4,543, by 1568 it was 9,302 and by 1583 there was 5,141. Nearly 25% of foreigners lived in villages outside London, inside the city French hatters stayed in

Immigrants arrived in London not just from all over England and Wales, but from abroad as well. In 1563, the total of foreigners in London was estimated at 4,543, by 1568 it was 9,302 and by 1583 there was 5,141. Nearly 25% of foreigners lived in villages outside London, inside the city French hatters stayed in Southwark

Southwark ( ) is a district of Central London situated on the south bank of the River Thames, forming the north-western part of the wider modern London Borough of Southwark. The district, which is the oldest part of South London, developed ...

, silk-weavers in Shoreditch

Shoreditch is an area in London, England and is located in the London Borough of Hackney alongside neighbouring parts of Tower Hamlets, which are also perceived as part of the area due to historic ecclesiastical links. Shoreditch lies just north ...

and Spitalfields

Spitalfields () is an area in London, England and is located in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is in East London and situated in the East End of London, East End. Spitalfields is formed around Commercial Street, London, Commercial Stre ...

; whereas Dutch printers based themselves in Clerkenwell

Clerkenwell ( ) is an area of central London, England.

Clerkenwell was an Civil Parish#Ancient parishes, ancient parish from the medieval period onwards, and now forms the south-western part of the London Borough of Islington. The St James's C ...

. Protestants came to London fleeing persecution in Catholic countries such as Spain, France, and Holland. In 1550, the chapel at St. Anthony's Hospital was converted into a French church, and the chapel at Austin Friars into a Dutch church, given special licence to operate outside of the conventions of the Church in England. This period also saw the first-known large-scale migration to London from Ireland. Irish migrants often settled in Wapping

Wapping () is an area in the borough of Tower Hamlets in London, England. It is in East London and part of the East End. Wapping is on the north bank of the River Thames between Tower Bridge to the west, and Shadwell to the east. This posit ...

and St. Giles-in-the-Fields. Since they were mostly Catholic, they were not welcomed by the Protestant Elizabeth I, who in 1593 banned Irish migrants unless they were homeowners, domestic servants, lawyers, or university students. Although Jews had been banned from England in the 13th century, there was a small community of 80-90 Portuguese Jews living in London during the reign of Elizabeth I.

The period sees London's first portrait of a named black person, the royal trumpeter John Blanke, who performed at the courts of Henry VII and Henry VIII. Aside from Blanke, a few black people appear in written records, such as the "blakemor" who arrived with Philip II of Spain

Philip II (21 May 152713 September 1598), sometimes known in Spain as Philip the Prudent (), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from 1580, and King of Naples and List of Sicilian monarchs, Sicily from 1554 until his death in 1598. He ...

when he came to London to marry Mary I, and an African needlemaker who worked on Cheapside

Cheapside is a street in the City of London, the historic and modern financial centre of London, England, which forms part of the A40 road, A40 London to Fishguard road. It links St Martin's Le Grand with Poultry, London, Poultry. Near its eas ...

.

In 1600, an ambassador arrived in London from modern-day Morocco called Abd el-Ouahed ben Messaoud, seeking an alliance between the King of Barbary

The Barbary Coast (also Barbary, Berbery, or Berber Coast) were the coastal regions of central and western North Africa, more specifically, the Maghreb and the Ottoman borderlands consisting of the regencies in Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli, a ...

and Elizabeth I. He brought a retinue of 17 other Muslim men with him, and had a portrait painted during his visit.

In 1602, one judge declared that there were 30,000 "idle persons and masterless men" (i.e., vagrants) living in London.

The Thames

The Thames is the main river in London, and its main trade route to Europe and the wider world. It was both wider and shallower than it is today, and in 1564 it froze over so completely that Elizabeth I and her courtiers held an archery practice on the ice. In this period, there was only one bridge-

The Thames is the main river in London, and its main trade route to Europe and the wider world. It was both wider and shallower than it is today, and in 1564 it froze over so completely that Elizabeth I and her courtiers held an archery practice on the ice. In this period, there was only one bridge- London Bridge

The name "London Bridge" refers to several historic crossings that have spanned the River Thames between the City of London and Southwark in central London since Roman Britain, Roman times. The current crossing, which opened to traffic in 197 ...

- which was frequently congested, so using wherries (small ferry-boats) to cross the river and go upstream or downstream was an important means of transportation within London, with an estimated 2,000 on the river. Due to its importance for trade, the Thames was lined with small wharf

A wharf ( or wharfs), quay ( , also ), staith, or staithe is a structure on the shore of a harbour or on the bank of a river or canal where ships may dock to load and unload cargo or passengers. Such a structure includes one or more Berth (mo ...

s within London, particularly on the north bank between London Bridge and the Tower of London. Most of these small wharfs were dedicated to one particular kind of trade- for example, Beare Quay for the ships coming from Portugal, Gibson's Quay for lead and tin, and Somers Quay for merchants from Flanders. In 1559, a decree outlined the legal quays along the riverside, and mandated that all imports should be declared at Custom House

A custom house or customs house was traditionally a building housing the offices for a jurisdictional government whose officials oversaw the functions associated with importing and exporting goods into and out of a country, such as collecting ...

.

Around 1513, royal dockyards are established at Woolwich and Deptford

Deptford is an area on the south bank of the River Thames in southeast London, in the Royal Borough of Greenwich and London Borough of Lewisham. It is named after a Ford (crossing), ford of the River Ravensbourne. From the mid 16th century ...

to construct a national fleet. The first commission at Woolwich was the '' Henry Grace à Dieu,'' then the largest ship in the world.

London Bridge

In this period, London Bridge was very different to today, lined on both sides with houses and shops up to four storeys tall. At the south end was a drawbridge which allowed tall ships to pass the bridge and acted as a defensive mechanism for the city. In 1579, the tower holding the drawbridge mechanism was replaced with Nonsuch House, a pre-fabricated mansion built in the Netherlands. South of Nonsuch House was the Great Stone Gate, where the heads of traitors such as Thomas More were displayed.Governance

The monarch had much more direct power to pass bills and change laws than today. Most Tudor monarchs summonedParliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

once a year, often to the Palace of Westminster, although Elizabeth I only summoned them ten times over her 45-year reign.

The City of London was governed by the Court of Aldermen, a group of officials, each representing a division of the City called a ward. Before 1550, there were 25 wards, with Southwark being added to make 26 in that year. Each year, the aldermen chose one of their number to act as Lord Mayor. The legislative branch of the City leadership was the Common Council, which had over 200 members. The administration of the city was based in the Guildhall, where it still stands.

Religion

At the beginning of the period, London contained 46 monasteries, nunneries, priories, abbeys, and friaries. London's monastic communities included Greyfriars, Blackfriars, Austin Friars, the Charterhouse, St. Bartholomew-the-Great, Holy Trinity Priory, St. Mary Overy, Westminster Abbey, St. Helen's Bishopsgate, St. Saviour Bermondsey, Crossed Friars, White Friars, and St. Mary Graces. In the surrounding area wasMerton Priory

Merton Priory was an English Augustinian priory founded in 1114 by Gilbert Norman, Sheriff of Surrey under King Henry I (1100–1135). It was situated within the manor of Merton in the county of Surrey, in what is today the Colliers Wood ...

, Barking Abbey

The Abbey of St Mary and St Ethelburga, founded in the 7th-century and commonly known as Barking Abbey, is a former Roman Catholic, royal monastery located in Barking, in the London Borough of Barking and Dagenham. It has been described as havi ...

, Bermondsey Abbey, Syon Abbey

Syon Abbey , also called simply Syon, was a dual monastery of men and women of the Bridgettines, Bridgettine Order, although it only ever had abbesses during its existence. It was founded in 1415 and stood, until its demolition in the 16th cent ...

, St. John Clerkenwell, Lesnes Abbey, Kilburn Priory, Holywell Priory

Holywell Priory or Haliwell, Halliwell, or Halywell (various spellings), was a religious house in Shoreditch, formerly in the historical county of Middlesex and now in the London Borough of Hackney. Its formal name was the Priory of St John the B ...

, St. Giles' Hospital, and St. Mary's Nunnery. A Franciscan

The Franciscans are a group of related organizations in the Catholic Church, founded or inspired by the Italian saint Francis of Assisi. They include three independent Religious institute, religious orders for men (the Order of Friars Minor bei ...

monastery was attached to Greenwich Palace in 1480. Many wealthy Londoners left bequests to these institutions in their wills, and so they came to own large amounts of land in London. By 1530, about a third of all land within the city walls was owned by the Church. London was also home to individuals with their own vows of monasticism, such as a hermit

A hermit, also known as an eremite (adjectival form: hermitic or eremitic) or solitary, is a person who lives in seclusion. Eremitism plays a role in a variety of religions.

Description

In Christianity, the term was originally applied to a Chr ...

who lived on Highgate Hill, and another on St. John Street.

In order to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon

Catherine of Aragon (also spelt as Katherine,

historical Spanish: , now: ; 16 December 1485 – 7 January 1536) was List of English royal consorts, Queen of England as the Wives of Henry VIII, first wife of King Henry VIII from their marr ...

, in the 1530s Henry VIII passed a series of Acts which broke away the Church in England from the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

in Rome, making him the Supreme Head of the Church in England. In April 1534, every male Londoner was required to swear the Oath of Succession, in which they agreed to recognise the king's annulment. In the monastery of London Charterhouse, the Carthusian

The Carthusians, also known as the Order of Carthusians (), are a Latin enclosed religious order of the Catholic Church. The order was founded by Bruno of Cologne in 1084 and includes both monks and nuns. The order has its own rule, called th ...

monks refused to acknowledge Henry as head of the church, and four of them including their prior, John Houghton, were hanged, drawn and quartered

To be hanged, drawn and quartered was a method of torture, torturous capital punishment used principally to execute men convicted of High treason in the United Kingdom, high treason in medieval and early modern Britain and Ireland. The convi ...

. The monastery was seized by the Crown, dissolved, and acquired by Edward North and later Thomas Howard, who was also executed for treason in 1572.

Other monastic houses were dissolved in a less bloody fashion, but their considerable lands and buildings were still given or sold off to aristocrats and politicians- for example, Lord Cobham acquired Blackfriars Priory; the Marquess of Winchester built Winchester House on the site of Holy Trinity Aldgate, and Lord Dudley acquired St. Giles' Hospital. Covent Garden

Covent Garden is a district in London, on the eastern fringes of the West End, between St Martin's Lane and Drury Lane. It is associated with the former fruit-and-vegetable market in the central square, now a popular shopping and tourist sit ...

, which was farmland belonging to Westminster Abbey, was granted to the Earl of Bedford. Some monastic sites Henry seized for himself, such as the hospital that became St. James's Palace, and land belonging to Westminster Abbey which he turned into Hyde Park. It is estimated that the monastic lands Henry seized were worth three times the land he already owned. By 1551, the Venetian ambassador, Giacomo Soranzo, wrote of London that it was "disfigured by the ruins of a multitude of churches and monasteries".

In 1535, an officially sanctioned English Bible was published. In 1539, six copies of the Great Bible were placed in St. Paul's Cathedral where anyone could read them or read them aloud to others. Churches were also physically reformed, with jewels, rood lofts and statues of saints being removed. Sometimes these were taken down by officials, but in other churches, such as St. Margaret Pattens, reformist mobs destroyed these objects. Under Edward VI, Protestant reforms were made such as the abolition of chantry chapels and the removal of saints' images and

In 1535, an officially sanctioned English Bible was published. In 1539, six copies of the Great Bible were placed in St. Paul's Cathedral where anyone could read them or read them aloud to others. Churches were also physically reformed, with jewels, rood lofts and statues of saints being removed. Sometimes these were taken down by officials, but in other churches, such as St. Margaret Pattens, reformist mobs destroyed these objects. Under Edward VI, Protestant reforms were made such as the abolition of chantry chapels and the removal of saints' images and stained glass

Stained glass refers to coloured glass as a material or art and architectural works created from it. Although it is traditionally made in flat panels and used as windows, the creations of modern stained glass artists also include three-dimensio ...

.

After 1550, the building of new churches in London stopped for over 70 years, with St. Giles-without-Cripplegate being finished in 1550, and the next new construction being after the end of the period in 1623 with the Queen's Chapel

The Queen's Chapel (officially, ''The Queen's Chapel St. James Palace'' and previously the German Chapel) is a chapel in central London, England. Designed by Inigo Jones, it was built between 1623 and 1625 as an adjunct to St. James's Palace, ini ...

near St. James' Palace.

When the Catholic Mary I

Mary I (18 February 1516 – 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and Queen of Spain as the wife of King Philip II from January 1556 until her death in 1558. She made vigorous a ...

came to the throne in 1554, many of the Protestant reforms were reversed, but monastery lands were not returned to the Church. While some Londoners were quick to restore saints' images and rood screens to their churches, others vehemently opposed the restoration of Catholic traditions. The parson of St. Ethelburga's, John Day, twice was put in the pillory

The pillory is a device made of a wooden or metal framework erected on a post, with holes for securing the head and hands, used during the medieval and renaissance periods for punishment by public humiliation and often further physical abuse. ...

and his ears nailed to it for speaking ill of the new queen, and in 1554 a dead cat dressed in the robes of a Catholic priest was found hanging on the gallows in Cheapside.

Trade and industry

During the Tudor period, London was rapidly rising in importance amongst Europe's commercial centers, and its many small industries were booming, especially weaving. Trade expanded beyond Western Europe to Russia, theLevant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

, and the Americas. This was the period of mercantilism

Mercantilism is a economic nationalism, nationalist economic policy that is designed to maximize the exports and minimize the imports of an economy. It seeks to maximize the accumulation of resources within the country and use those resources ...

. In 1486, the Fellowship of Merchant Adventurers of London was formed, a company trading with the Low Countries. From the 1550s, joint-stock companies, mostly formed of Londoners, were formed with monopolies on trades to various parts of the world, including the Muscovy Company

The Muscovy Company (also called the Russia Company or the Muscovy Trading Company; ) was an English trading company chartered in 1555. It was the first major Chartered company, chartered joint-stock company, the precursor of the type of business ...

(1555), the Eastland Company (1579), the Venice Company (1583), the Levant Company

The Levant Company was an English chartered company formed in 1592. Elizabeth I of England approved its initial charter on 11 September 1592 when the Venice Company (1583) and the Turkey Company (1581) merged, because their charters had expired, ...

(1592), and the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company that was founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to Indian Ocean trade, trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (South A ...

(1600).

Markets were an important system of trade, with many taking place around the city. In 1565, Thomas Gresham founded a new mercantile exchange- a sort of early shopping centre- which was awarded the title the " Royal Exchange" by Queen Elizabeth in 1571. London's main market was on Cheapside

Cheapside is a street in the City of London, the historic and modern financial centre of London, England, which forms part of the A40 road, A40 London to Fishguard road. It links St Martin's Le Grand with Poultry, London, Poultry. Near its eas ...

. Booksellers and stationers sold their goods in St. Paul's Churchyard. The Stocks market was held next to St. Mary Woolchurch Haw and in 1543, it had 25 fishmongers and 18 butchers.

There were also annual fairs held at various places in London, involving large markets and entertainments. One of the most well-known was Bartholomew Fair, held in Smithfield on land belonging to the priory of St. Bartholomew-the-Great. After the priory was dissolved, the land was acquired by Richard Rich, who continued the annual fair. It was visited by the German tutor Paul Hentzner in 1598, who described the Worshipful Company of Merchant Taylors gathering at the Hand and Shears pub in preparation for checking the measures of the goods on sale at the fair.

London merchants also obtained goods through privateer

A privateer is a private person or vessel which engages in commerce raiding under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign o ...

ing. From 1562, vessels were increasingly given a "letter of marque

A letter of marque and reprisal () was a Sovereign state, government license in the Age of Sail that authorized a private person, known as a privateer or French corsairs, corsair, to attack and capture vessels of a foreign state at war with t ...

" that permitted them to raid foreign vessels. In 1598, half of all English privateer vessels were from London. One famous privateer who rose to prominence in this period was Francis Drake

Sir Francis Drake ( 1540 – 28 January 1596) was an English Exploration, explorer and privateer best known for making the Francis Drake's circumnavigation, second circumnavigation of the world in a single expedition between 1577 and 1580 (bein ...

, who circumnavigated the globe in his ship ''Golden Hind

''Golden Hind'' was a galleon captained by Francis Drake in his circumnavigation of the world between 1577 and 1580. She was originally known as ''Pelican,'' but Drake renamed her mid-voyage in 1578, in honour of his patron, Sir Christopher Ha ...

'', returning to London in 1581 and being knighted on the deck of his ship in Deptford. A special dock was built in Deptford to house the ship, where it was available to be viewed by tourists.

During the latter half of the 16th century, there was an increase in poverty as the cost of living increased while wages were fixed by the government, this caused crowds of poor people seeking work in the city including beggars.

Health and medicine

Prior to the Reformation, hospitals were run by monastic institutions. At the beginning of the period, London had five principal hospitals, totalling somewhere between 350 and 400 beds. They were St. Bartholomew's in Smithfield; St. Thomas' in Southwark; St. Mary-without-Bishopsgate, which specialised in maternity care; St. Elsyng Spital, which specialised in the homeless blind; and St. Mary Bethlehem, commonly known as Bedlam, which specialised in mental illness. Many of these hospitals also functioned as shelters for the homeless or the infirm. In 1505, Henry VII founded St. John the Baptist's Hospital on the site of the Savoy Palace. These were all dissolved in the Reformation, and mostly given over to the city to re-establish them as secular hospitals, except for St. Mary-without-Bishopsgate and St. Elsying Spital, which were permanently closed. The estate of the Savoy Hospital was given to St. Thomas'.

Individual physicians and surgeons may have received a medical degree from a university or had been granted a licence after taking an apprenticeship, however many were completely unlicensed. By the end of the period, there was a medical practitioner (a physician, surgeon or apothecary) for every 400 people in London.

Outside the city, there were leper hospitals from at least 1500 at

Prior to the Reformation, hospitals were run by monastic institutions. At the beginning of the period, London had five principal hospitals, totalling somewhere between 350 and 400 beds. They were St. Bartholomew's in Smithfield; St. Thomas' in Southwark; St. Mary-without-Bishopsgate, which specialised in maternity care; St. Elsyng Spital, which specialised in the homeless blind; and St. Mary Bethlehem, commonly known as Bedlam, which specialised in mental illness. Many of these hospitals also functioned as shelters for the homeless or the infirm. In 1505, Henry VII founded St. John the Baptist's Hospital on the site of the Savoy Palace. These were all dissolved in the Reformation, and mostly given over to the city to re-establish them as secular hospitals, except for St. Mary-without-Bishopsgate and St. Elsying Spital, which were permanently closed. The estate of the Savoy Hospital was given to St. Thomas'.

Individual physicians and surgeons may have received a medical degree from a university or had been granted a licence after taking an apprenticeship, however many were completely unlicensed. By the end of the period, there was a medical practitioner (a physician, surgeon or apothecary) for every 400 people in London.

Outside the city, there were leper hospitals from at least 1500 at Hammersmith

Hammersmith is a district of West London, England, southwest of Charing Cross. It is the administrative centre of the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham, and identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London.

It ...

and Knightsbridge

Knightsbridge is a residential and retail district in central London, south of Hyde Park, London, Hyde Park. It is identified in the London Plan as one of two international retail centres in London, alongside the West End of London, West End. ...

.

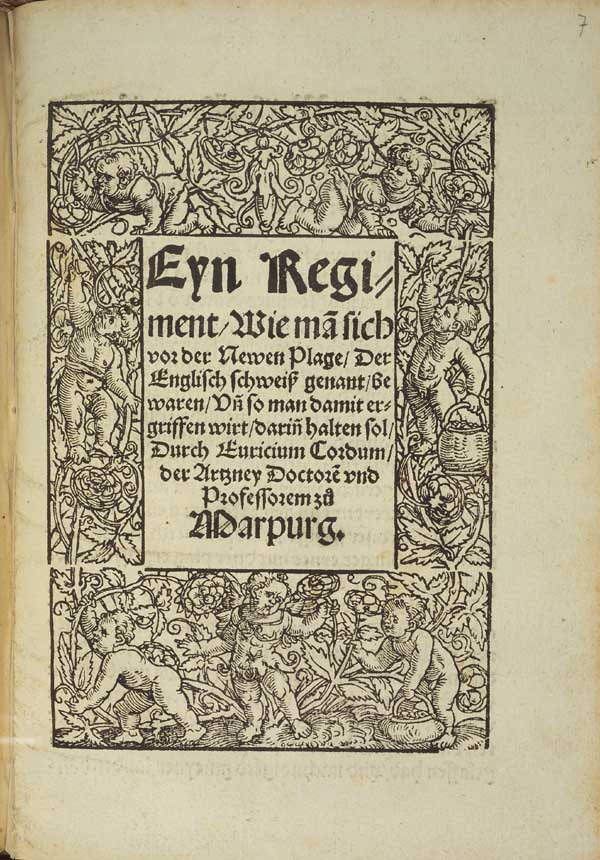

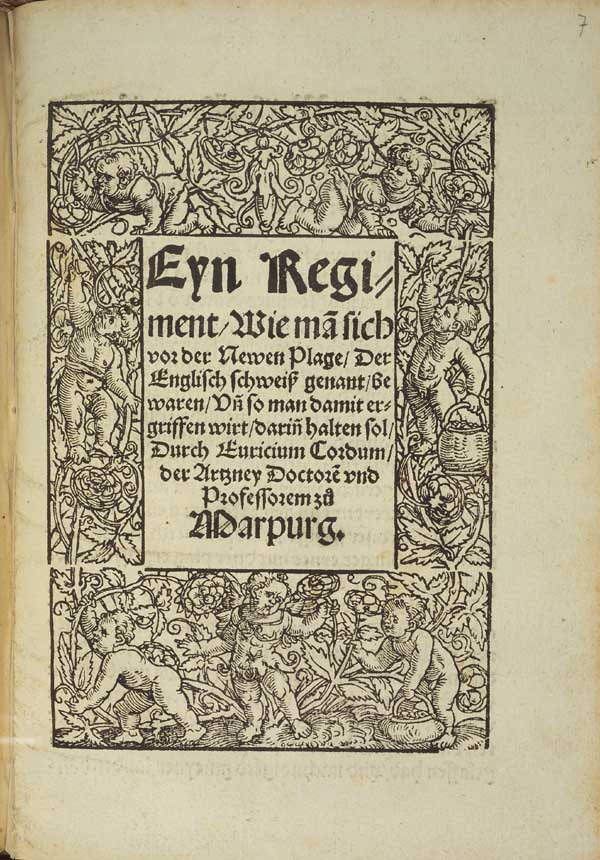

The very first year of the period coincided with a serious outbreak of a disease known as the "sweating sickness

Sweating sickness, also known as the sweats, English sweating sickness, English sweat or ''sudor anglicus'' in Latin, was a mysterious and contagious disease that struck England and later continental Europe in a series of epidemics beginning i ...

" which generally killed its victims within a single day. Two Lord Mayors died within four days. London would continue to suffer epidemics of the sweating sickness throughout the period. There were also repeated outbreaks of plague. During these epidemics, wealthy people would leave London for the season until it was safe to return, meaning that the disease disproportionately affected the poor. 1518 saw England's first nationwide quarantine

A quarantine is a restriction on the movement of people, animals, and goods which is intended to prevent the spread of disease or pests. It is often used in connection to disease and illness, preventing the movement of those who may have bee ...

orders, following similar ordinances in Venice and Paris. In London, houses with infected people were quarantined for 40 days, and those infected were ordered to carry a white stick when outside, so that others could avoid them. London lagged behind other European cities in health measures, leading Soranzo to write that there was "some little plague in England well nigh every year, for which they are not accustomed to make sanitary provisions".

The Royal College of Physicians

The Royal College of Physicians of London, commonly referred to simply as the Royal College of Physicians (RCP), is a British professional membership body dedicated to improving the practice of medicine, chiefly through the accreditation of ph ...

was founded in 1518 at the house of noted physician Thomas Linacre in Knightrider Street. It had the authority to regulate practitioners and even imprison unlicensed practitioners for up to twenty days.

Crime and law enforcement

A serious outbreak of violence in this period occurred onEvil May Day

Evil May Day or Ill May Day is the name of a Xenophobia, xenophobic riot which took place on 1 May 1517 as a protest against foreigners (called "strangers") living in London. Apprenticeship, Apprentices attacked foreign residents ranging from "Fle ...

in 1517, when a xenophobic riot broke out among London apprentices. Young London men stormed the houses and workshops of French and Flemish craftspeople. The Duke of Norfolk

Duke of Norfolk is a title in the peerage of England. The premier non-royal peer, the Duke of Norfolk is additionally the premier duke and earl in the English peerage. The seat of the Duke of Norfolk is Arundel Castle in Sussex, although the t ...

led an armed militia into the city to disperse the rioters. 278 were arrested, with 15 later being executed.

In 1533, the Buggery Act was passed, making sex acts such as sodomy and bestiality illegal for the first time in England. One of the first to be convicted under this law was Walter Hungerford, 1st Baron Hungerford of Heytesbury, who was beheaded at Tower Hill in 1540. At first, the Act was mostly used to convict monks; in 1546, the churchman John Bale

John Bale (21 November 1495 – November 1563) was an English churchman, historian controversialist, and Bishop of Ossory in Ireland. He wrote the oldest known historical verse drama in English (on the subject of King John), and developed and ...

called the clergy "none other than sodomites and whoremongers all the pack". Later in the period, theatres and schools were thought to be particular hot-beds of buggery: in 1541, the headmaster of Eton College

Eton College ( ) is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school providing boarding school, boarding education for boys aged 13–18, in the small town of Eton, Berkshire, Eton, in Berkshire, in the United Kingdom. It has educated Prime Mini ...

, Nicholas Udall, was questioned in London and confessed to committing buggery with one of his students, Thomas Cheyne. He was imprisoned in Marshalsea before being later appointed headmaster of Westminster School

Westminster School is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school in Westminster, London, England, in the precincts of Westminster Abbey. It descends from a charity school founded by Westminster Benedictines before the Norman Conquest, as do ...

.

In 1536, the Member of Parliament Robert Pakington became one of the first recorded Londoners to be murdered with a handgun. No-one was ever convicted of the crime.

On certain days of the weeks and at religious festivals, Londoners were forbidden from eating meat, with only fish allowed. In 1561, a butcher in Eastcheap

Eastcheap is a street in central London that is a western continuation of Great Tower Street towards Monument junction. Its name derives from ''cheap'', the Old English word for marketplace, market, with the prefix 'East' distinguishing it from ...

was fined £20 for killing three cows during Lent

Lent (, 'Fortieth') is the solemn Christianity, Christian religious moveable feast#Lent, observance in the liturgical year in preparation for Easter. It echoes the 40 days Jesus spent fasting in the desert and enduring Temptation of Christ, t ...

, and in 1563, two women were put in the stocks at St. Katherine's by the Tower for refusing to abide by the rule.

In 1585, a thieves' school was found in Billingsgate, where trainee pickpockets would attempt to take coins from a purse. Hanging on the wall next to the purse was a bell which would ring if the students performed poorly.

The end of the period saw the development of a type of boisterous, semi-criminal working-class woman called the " roaring girl". Although the most famous roaring girls, such as Mary Frith, lived in the Stuart period, there are early Tudor examples such as Long Meg, a possibly-fictional woman depicted in the pamphlet ''The Life and Pranks of Long Meg of Westminster''. Long Meg ran a tavern in Islington

Islington ( ) is an inner-city area of north London, England, within the wider London Borough of Islington. It is a mainly residential district of Inner London, extending from Islington's #Islington High Street, High Street to Highbury Fields ...

, dressed as a man, and fought with any man who dared challenge her.

Punishments

Public corporal and capital punishment were both used widely in London. Hangings commonly took place atTyburn

Tyburn was a Manorialism, manor (estate) in London, Middlesex, England, one of two which were served by the parish of Marylebone. Tyburn took its name from the Tyburn Brook, a tributary of the River Westbourne. The name Tyburn, from Teo Bourne ...

, but gallows could be erected at any convenient location close to a murder scene. People convicted of piracy were often hanged on the Wapping

Wapping () is an area in the borough of Tower Hamlets in London, England. It is in East London and part of the East End. Wapping is on the north bank of the River Thames between Tower Bridge to the west, and Shadwell to the east. This posit ...

foreshore of the Thames at low tide, with the bodies left on the gallows until the tide washed over them three times. Beheadings are generally reserved for the nobility, and often take place on Tower Hill

Tower Hill is the area surrounding the Tower of London in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is infamous for the public execution of high status prisoners from the late 14th to the mid 18th century. The execution site on the higher gro ...

. Tudor London saw the only two instances of an execution method not used at any other time in England- boiling alive, a fate reserved for poisoners. Both executions took place at Smithfield.

The pillory

The pillory is a device made of a wooden or metal framework erected on a post, with holes for securing the head and hands, used during the medieval and renaissance periods for punishment by public humiliation and often further physical abuse. ...

was a common punishment for low-level offences, with a pillory being erected at Cheapside

Cheapside is a street in the City of London, the historic and modern financial centre of London, England, which forms part of the A40 road, A40 London to Fishguard road. It links St Martin's Le Grand with Poultry, London, Poultry. Near its eas ...

, among other places. The stocks were similar, but held a person's legs rather than their hands and face. Public whippings took place for offences such as petty theft, sedition

Sedition is overt conduct, such as speech or organization, that tends toward rebellion against the established order. Sedition often includes subversion of a constitution and incitement of discontent toward, or insurrection against, establ ...

, or having an illegitimate child. For example, in 1561, a man was whipped through the streets in Westminster, the city, across London Bridge, and into Southwark, for forging documents; and in the same year, two men recently released from Bedlam Hospital and Marshalsea Prison

The Marshalsea (1373–1842) was a notorious prison in Southwark, just south of the River Thames. Although it housed a variety of prisoners—including men accused of crimes at sea and political figures charged with sedition—it became known, ...

claimed to be the risen Christ and Saint Peter

Saint Peter (born Shimon Bar Yonah; 1 BC – AD 64/68), also known as Peter the Apostle, Simon Peter, Simeon, Simon, or Cephas, was one of the Twelve Apostles of Jesus and one of the first leaders of the Jewish Christian#Jerusalem ekklēsia, e ...

, and were both whipped through the streets. Another punishment designed for public humiliation was the tumbrel, a cart carrying the offender that was wheeled through the streets. In 1560, two men and three women were put on the tumbrel in London for fornication, and in 1563, a physician called Christopher Langton was carted down Cheapside for being caught "with two young wenches at once". In addition, mob justice took place throughout the period. For example, in 1561, a man was chased by an angry mob for stealing a child's necklace, and was beaten to death in Mark Lane.

London had a debtors' prison

A debtors' prison is a prison for people who are unable to pay debt. Until the mid-19th century, debtors' prisons (usually similar in form to locked workhouses) were a common way to deal with unpaid debt in Western Europe.Cory, Lucinda"A Histor ...

called the Fleet, for the imprisonment of people who could not pay their creditors. It housed about fifty inmates, and was notorious for its poor conditions and disease. Inmates had to pay for food, and pay rent for a separate room.

Treason

Several high-profile nobles and even royalty were executed fortreason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state (polity), state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to Coup d'état, overthrow its government, spy ...

in London in this period. Also, there were several large rebellions against Tudor monarchs which either took place in London or ended with the rebels being imprisoned or executed in London.

In 1497, Perkin Warbeck

Perkin Warbeck ( – 23 November 1499) was a pretender to the English throne claiming to be Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York, who was the second son of Edward IV and one of the so-called "Princes in the Tower". Richard, were he alive, would ...

, who claimed to be the true heir to the throne, Richard, Duke of York, was captured and paraded through the streets of London before being imprisoned in the Tower and executed in 1499 on Tower Hill

Tower Hill is the area surrounding the Tower of London in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is infamous for the public execution of high status prisoners from the late 14th to the mid 18th century. The execution site on the higher gro ...

. In the same year, a group of rebels from Cornwall marched on London in protest of high taxes. They were defeated at Blackheath in the Battle of Deptford Bridge, and their leader, Lord Audley, was beheaded on Tower Hill.

Several Londoners opposed Henry VIII's marriage to Anne Boleyn, including the prophetess Elizabeth Barton. She predicted that Henry would die within six months of his marriage to Anne, and although her prophecy did not come true, she was executed at Tyburn

Tyburn was a Manorialism, manor (estate) in London, Middlesex, England, one of two which were served by the parish of Marylebone. Tyburn took its name from the Tyburn Brook, a tributary of the River Westbourne. The name Tyburn, from Teo Bourne ...

in 1534 and her head put on a spike at London Bridge. In 1536, Anne herself was imprisoned in the Tower on suspicion of being unfaithful in her marriage. She was beheaded in the grounds of the Tower of London in 1536. Henry's fifth wife, Catherine Howard, was also beheaded for adultery in 1541.

In 1548, the Privy Council and the City of London attempted to depose Edward Seymour, who was acting as Lord Protector

Lord Protector (plural: ''Lords Protector'') is a title that has been used in British constitutional law for the head of state. It was also a particular title for the British heads of state in respect to the established church. It was sometime ...

, ruling on behalf of the child king Edward VI before he came of age. Seymour was captured and sent to the Tower of London before being exiled to Richmond Palace and executed on Tower Hill in 1552.

In 1553, Edward VI named his Protestant cousin Lady Jane Grey

Lady Jane Grey (1536/1537 – 12 February 1554), also known as Lady Jane Dudley after her marriage, and nicknamed as the "Nine Days Queen", was an English noblewoman who was proclaimed Queen of England and Ireland on 10 July 1553 and reigned ...

as his successor rather than his Catholic half-sister Mary. After his death, Mary marched on London with an army to meet the forces of the Duke of Northumberland

Duke of Northumberland is a noble title that has been created three times in English and British history, twice in the Peerage of England and once in the Peerage of Great Britain. The current holder of this title is Ralph Percy, 12th Duke of N ...

in Shoreditch

Shoreditch is an area in London, England and is located in the London Borough of Hackney alongside neighbouring parts of Tower Hamlets, which are also perceived as part of the area due to historic ecclesiastical links. Shoreditch lies just north ...

. Londoners refused to support Northumberland, who was imprisoned along with Jane and her husband, Guildford Dudley. All were later executed for treason.

In 1554, a rebellion began in Kent led by Thomas Wyatt in protest of Mary I's marriage to Philip II of Spain

Philip II (21 May 152713 September 1598), sometimes known in Spain as Philip the Prudent (), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from 1580, and King of Naples and List of Sicilian monarchs, Sicily from 1554 until his death in 1598. He ...

. The rebels marched on London, and the Londoners sent out to defend the city instead defected to the side of the rebels. Mary went to the London Guildhall and gave a speech where she accused Wyatt of attempting to seize the Tower where wealthy Londoners kept their money, and rallied a force to prevent Wyatt's men from crossing London Bridge. The artillery of the Tower fired at London Bridge and St. Mary Overy, where the rebels were gathered, and so Wyatt took his force west to cross the river at Kingston-upon-Thames

Kingston upon Thames, colloquially known as Kingston, is a town in the Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames, south-west London, England. It is situated on the River Thames, south-west of Charing Cross. It is an ancient market town, notable as ...

instead, marching towards London from the west. Once again, the gates of London are held closed against him, and Wyatt is defeated at Temple Bar and later executed. Mary suspected her sister Elizabeth of involvement, but Wyatt refused to implicate her, and Elizabeth was released from the Tower.

In 1579, Elizabeth was on the royal barge at Greenwich when a bullet hit her helmsman. She gave him her scarf and told him to be glad, as he stopped a bullet meant for her. A man called Thomas Appletree confessed to the crime, saying that he had been showing off to some friends by firing randomly and hadn't meant to hit the royal barge. He was sentenced to be hanged close to the scene of his crime, and was given a royal reprieve at the last moment.

The reign of Elizabeth saw Catholics being executed for treason in large numbers. In 1581, the Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

priest Thomas Campion was imprisoned in a tiny cell in the Tower of London called the Little Ease before being hanged, drawn and quartered at Tyburn, and another Jesuit priest, Robert Southwell, was imprisoned in Newgate in 1595 before being executed in the same fashion.

1586 saw the execution of Anthony Babington

Anthony Babington (24 October 156120 September 1586) was an English gentleman convicted of plotting the assassination of Elizabeth I of England and conspiring with the imprisoned Mary, Queen of Scots, for which he was hanged, drawn and quartered ...

for his part in a plot to overthrow Elizabeth and replace her with her cousin, Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was List of Scottish monarchs, Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legit ...

. He and thirteen co-conspirators were executed near Holborn, possibly at Lincoln's Inn Fields

Lincoln's Inn Fields is located in Holborn and is the List of city squares by size, largest public square in London. It was laid out in the 1630s under the initiative of the speculative builder and contractor William Newton, "the first in a ...

. After the first seven were disembowelled still alive, the crowd was so disgusted that the remainder were permitted to die by hanging before being disembowelled. Another person executed for treason, albeit on much scantier evidence, was the Portuguese-Jewish royal physician, Roderigo Lopes, who was hanged in 1594.

The last major revolt of the period was Essex's Rebellion in 1601, where Robert Devereux gathered together a group of rebels at Essex House. When the Lord Chief Justice

The Lord or Lady Chief Justice of England and Wales is the head of the judiciary of England and Wales and the president of the courts of England and Wales.

Until 2005 the lord chief justice was the second-most senior judge of the English a ...

and other officers arrived, Essex imprisoned them and took his forced to the city. However, the Lord Mayor's forces drove him back to his house, where he was arrested, and later executed at the Tower.

Heresy

Religious persecution occurred under every monarch in this period. Between 1485 and 1553, 102 heretics wereburned at the stake

Death by burning is an list of execution methods, execution, murder, or suicide method involving combustion or exposure to extreme heat. It has a long history as a form of public capital punishment, and many societies have employed it as a puni ...

around the country, many at Smithfield, the usual London location for burnings.

The Lollard

Lollardy was a proto-Protestantism, proto-Protestant Christianity, Christian religious movement that was active in England from the mid-14th century until the 16th-century English Reformation. It was initially led by John Wycliffe, a Catholic C ...

movement demanded the translation of the Bible into English, a practice considered heretical at the time. Illicit English translations of the New Testament

The New Testament (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus, as well as events relating to Christianity in the 1st century, first-century Christianit ...

were smuggled into London from Germany and Antwerp

Antwerp (; ; ) is a City status in Belgium, city and a Municipalities of Belgium, municipality in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is the capital and largest city of Antwerp Province, and the third-largest city in Belgium by area at , after ...

, and even the dean of St. Paul's Cathedral was threatened with prosecution for translating the Lord's Prayer into English.

Under Henry VIII, those executed for heresy were just as likely to be Protestant as Catholic. In 1540, six people were executed at Smithfield on the same day without trial or even charges read against them. Three were Protestants and were burned at the stake, and three were Catholic and were hanged. In 1546, the staunch Protestant Anne Askew was tortured on the rack at the Tower of London and burned at the stake in Smithfield for heresy.

In the reign of Mary I, 78 were burned in London alone. After her reign, John Foxe

John Foxe (1516/1517 – 18 April 1587) was an English clergyman, theologian, and historian, notable for his martyrology '' Foxe's Book of Martyrs'', telling of Christian martyrs throughout Western history, but particularly the sufferings of En ...

collected stories of Protestant martyrs in his '' Acts and Monuments'', published in Aldersgate. Under Elizabeth I, Catholics were less likely to be burned for heresy, but more likely to be executed for treason. From 1584, anyone who became a Catholic priest after Elizabeth's accession was declared guilty of treason. Instead, those burned for heresy were more likely to be from radical Protestant sects such as Anabaptism

Anabaptism (from Neo-Latin , from the Greek language, Greek : 're-' and 'baptism'; , earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re-baptizers"), considering it biased. ...

. In 1575, two Dutch Anabaptists from Aldgate

Aldgate () was a gate in the former defensive wall around the City of London.

The gate gave its name to ''Aldgate High Street'', the first stretch of the A11 road, that takes that name as it passes through the ancient, extramural Portsoken ...

are burned at the stake.

Courts

As well as advising the monarch on affairs of state, the privy council also acted as a law court calledStar Chamber

The court of Star Chamber () was an English court that sat at the royal Palace of Westminster, from the late to the mid-17th century (), and was composed of privy counsellors and common-law judges, to supplement the judicial activities of the ...

, meeting in the Palace of Westminster. It tried people who had breached the privy council's orders, duellists, conspirators, rioters, libellers, etc., and had the distinction of being the only body with the power to authorise the use of torture. Defendants called before the Star Chamber did not have the right to speak, or even to hear the evidence against them; some were merely summoned to hear the judgement passed on them.

Also at the Palace of Westminster there were four royal courts: the Court of the Exchequer, the Court of the Queen's Bench, the Court of Common Pleas, and the Court of Chancery

The Court of Chancery was a court of equity in England and Wales that followed a set of loose rules to avoid a slow pace of change and possible harshness (or "inequity") of the Common law#History, common law. The Chancery had jurisdiction over ...

. Parliament itself also acted as a court for some treason cases. They tried cases in bursts called "sessions", which took place every three months. Thomas Platter wrote that "rarely does a law day take place in London in all the four sessions pass without some twenty to thirty persons, both men and women, being gibbeted".

Education

At the beginning of the period, the best London schools were run by monastic institutions such as St. Anthony's Hospital in Threadneedle Street and St. Peter's Cornhill. St Paul's Cathedral School was refounded by John Colet in 1510 for 153 boys to study for free. By 1525 it was so popular that applications had to be restricted to London boys only. In 1531, the Nicholas Gibson Free School was founded on Ratcliffe Highway by a wealthy grocer. In the reigns of Edward VI and Elizabeth I, many grammar schools were founded to replace educational establishments that had been run by monks and dissolved.Christ's Hospital

Christ's Hospital is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school (English Private schools in the United Kingdom, fee-charging boarding school for pupils aged 11–18) with a royal charter, located to the south of Horsham in West Sussex.

T ...

was founded in 1552, on the grounds of Greyfriars. In 1558, Enfield Grammar School

Enfield Grammar School (abbreviated to EGS; also known as Enfield Grammar) is a boys' comprehensive school and sixth form with Academy (English school), academy status, founded in 1558, situated in Enfield Town in the London Borough of Enfield ...

was refounded. In 1560, Elizabeth refounded Westminster School

Westminster School is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school in Westminster, London, England, in the precincts of Westminster Abbey. It descends from a charity school founded by Westminster Benedictines before the Norman Conquest, as do ...

with 40 free places for boys known as the Queen's Scholars. Kingston Grammar School and St. Olave's Grammar School were both set up in 1561, Highgate School in 1565, Harrow School

Harrow School () is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school (English boarding school for boys) in Harrow on the Hill, Greater London, England. The school was founded in 1572 by John Lyon (school founder), John Lyon, a local landowner an ...

in 1572, and Queen Elizabeth's School in Chipping Barnet

Chipping Barnet or High Barnet is a suburban market town in north London, forming part of the London Borough of Barnet, England. It is a suburban development built around a 12th-century settlement, and is located north-northwest of Charing C ...

in 1573.

Livery companies also founded their own schools, such as the Mercers' School in Old Jewry in 1541, and the Merchant Taylors' School on Suffolk Lane in 1561.

When Thomas Gresham died in 1579, he provided for the foundation of Gresham College

Gresham College is an institution of higher learning located at Barnard's Inn Hall off Holborn in Central London, England that does not accept students or award degrees. It was founded in 1597 under the Will (law), will of Sir Thomas Gresham, ...

in his will, which offers free lectures on astronomy, divinity, geometry, law, medicine, music and rhetoric. After his widow died in 1596, their house in Bishopsgate