trigonometric substitution on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

Integrals such as

can also be evaluated by partial fractions rather than trigonometric substitutions. However, the integral

cannot. In this case, an appropriate substitution is:

where so that and by assuming so that and

Then,

One may evaluate the integral of the secant function by multiplying the numerator and denominator by and the integral of secant cubed by parts. As a result,

When which happens when given the range of arcsecant, meaning instead in that case.

Integrals such as

can also be evaluated by partial fractions rather than trigonometric substitutions. However, the integral

cannot. In this case, an appropriate substitution is:

where so that and by assuming so that and

Then,

One may evaluate the integral of the secant function by multiplying the numerator and denominator by and the integral of secant cubed by parts. As a result,

When which happens when given the range of arcsecant, meaning instead in that case.

mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

, a trigonometric substitution replaces a trigonometric function

In mathematics, the trigonometric functions (also called circular functions, angle functions or goniometric functions) are real functions which relate an angle of a right-angled triangle to ratios of two side lengths. They are widely used in all ...

for another expression. In calculus

Calculus is the mathematics, mathematical study of continuous change, in the same way that geometry is the study of shape, and algebra is the study of generalizations of arithmetic operations.

Originally called infinitesimal calculus or "the ...

, trigonometric substitutions are a technique for evaluating integrals. In this case, an expression involving a radical function is replaced with a trigonometric one. Trigonometric identities may help simplify the answer. Like other methods of integration by substitution, when evaluating a definite integral, it may be simpler to completely deduce the antiderivative before applying the boundaries of integration.

Case I: Integrands containing ''a''2 − ''x''2

Let and use the identityExamples of Case I

Example 1

In the integral we may use Then, The above step requires that and We can choose to be the principal root of and impose the restriction by using the inverse sine function. For a definite integral, one must figure out how the bounds of integration change. For example, as goes from to then goes from to so goes from to Then, Some care is needed when picking the bounds. Because integration above requires that , can only go from to Neglecting this restriction, one might have picked to go from to which would have resulted in the negative of the actual value. Alternatively, fully evaluate the indefinite integrals before applying the boundary conditions. In that case, the antiderivative gives as before.Example 2

The integral may be evaluated by letting where so that and by the range of arcsine, so that and Then, For a definite integral, the bounds change once the substitution is performed and are determined using the equation with values in the range Alternatively, apply the boundary terms directly to the formula for the antiderivative. For example, the definite integral may be evaluated by substituting with the bounds determined using Because and On the other hand, direct application of the boundary terms to the previously obtained formula for the antiderivative yields as before.Case II: Integrands containing ''a''2 + ''x''2

Let and use the identityExamples of Case II

Example 1

In the integral we may write so that the integral becomes provided For a definite integral, the bounds change once the substitution is performed and are determined using the equation with values in the range Alternatively, apply the boundary terms directly to the formula for the antiderivative. For example, the definite integral may be evaluated by substituting with the bounds determined using Since and Meanwhile, direct application of the boundary terms to the formula for the antiderivative yields same as before.Example 2

The integral may be evaluated by letting where so that and by the range of arctangent, so that and Then, The integral of secant cubed may be evaluated usingintegration by parts

In calculus, and more generally in mathematical analysis, integration by parts or partial integration is a process that finds the integral of a product of functions in terms of the integral of the product of their derivative and antiderivati ...

. As a result,

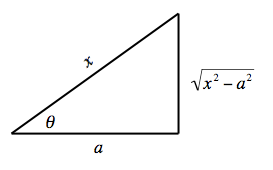

Case III: Integrands containing ''x''2 − ''a''2

Let and use the identityExamples of Case III

Integrals such as

can also be evaluated by partial fractions rather than trigonometric substitutions. However, the integral

cannot. In this case, an appropriate substitution is:

where so that and by assuming so that and

Then,

One may evaluate the integral of the secant function by multiplying the numerator and denominator by and the integral of secant cubed by parts. As a result,

When which happens when given the range of arcsecant, meaning instead in that case.

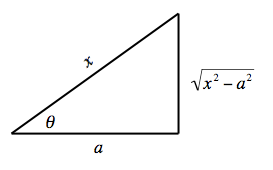

Integrals such as

can also be evaluated by partial fractions rather than trigonometric substitutions. However, the integral

cannot. In this case, an appropriate substitution is:

where so that and by assuming so that and

Then,

One may evaluate the integral of the secant function by multiplying the numerator and denominator by and the integral of secant cubed by parts. As a result,

When which happens when given the range of arcsecant, meaning instead in that case.

Substitutions that eliminate trigonometric functions

Substitution can be used to remove trigonometric functions. For instance, The last substitution is known as the Weierstrass substitution, which makes use of tangent half-angle formulas. For example,Hyperbolic substitution

Substitutions ofhyperbolic function

In mathematics, hyperbolic functions are analogues of the ordinary trigonometric functions, but defined using the hyperbola rather than the circle. Just as the points form a circle with a unit radius, the points form the right half of the ...

s can also be used to simplify integrals.

For example, to integrate , introduce the substitution (and hence ), then use the identity to find:

If desired, this result may be further transformed using other identities, such as using the relation :

See also

*Integration by substitution

In calculus, integration by substitution, also known as ''u''-substitution, reverse chain rule or change of variables, is a method for evaluating integrals and antiderivatives. It is the counterpart to the chain rule for differentiation, and c ...

* Weierstrass substitution

* Euler substitution

References

{{Integrals Integral calculus Trigonometry