Transorangia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Orange Free State ( ; ) was an independent

Distracted among themselves, with the formidable Basotho power on their southern and eastern flank, the troubles of the infant state were speedily added to by the action of the Transvaal Boers of the

Distracted among themselves, with the formidable Basotho power on their southern and eastern flank, the troubles of the infant state were speedily added to by the action of the Transvaal Boers of the

During the period of Brand's presidency a great change, both political and economic, had come over South Africa. The renewal of the policy of British expansion had been answered by the formation of the

During the period of Brand's presidency a great change, both political and economic, had come over South Africa. The renewal of the policy of British expansion had been answered by the formation of the

In December 1897 the Free State revised its constitution in reference to the franchise law, and the period of residence necessary to obtain naturalization was reduced from five to three years. The oath of allegiance to the state was alone required, and no renunciation of nationality was insisted upon. In 1898 the Free State also acquiesced in the new convention arranged with regard to the Customs Union between the

In December 1897 the Free State revised its constitution in reference to the franchise law, and the period of residence necessary to obtain naturalization was reduced from five to three years. The oath of allegiance to the state was alone required, and no renunciation of nationality was insisted upon. In 1898 the Free State also acquiesced in the new convention arranged with regard to the Customs Union between the

National Anthem of the Orange Free State (1854–1902)

on YouTube {{Coord, 29, 00, S, 26, 00, E, region:ZA_type:adm1st_source:GNS-enwiki, display=title Boer Republics States and territories established in 1854 States and territories disestablished in 1902 Former countries in Africa Former republics History of the Free State (province) 1854 establishments in South Africa 1902 disestablishments in South Africa South Africa and the Commonwealth of Nations White supremacy in Africa

Boer

Boers ( ; ; ) are the descendants of the proto Afrikaans-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controlled the Dutch ...

-ruled sovereign republic under British suzerainty

A suzerain (, from Old French "above" + "supreme, chief") is a person, state (polity)">state or polity who has supremacy and dominant influence over the foreign policy">polity.html" ;"title="state (polity)">state or polity">state (polity)">st ...

in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeated and surrendered to the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

at the end of the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

in 1902. It is one of the three historical precursors to the present-day Free State province.

Extending between the Orange

Orange most often refers to:

*Orange (fruit), the fruit of the tree species '' Citrus'' × ''sinensis''

** Orange blossom, its fragrant flower

** Orange juice

*Orange (colour), the color of an orange fruit, occurs between red and yellow in the vi ...

and Vaal

The Vaal River ( ; Khoemana: ) is the largest tributary of the Orange River in South Africa. The river has its source near Breyten in Mpumalanga province, east of Johannesburg and about north of Ermelo and only about from the Indian Oce ...

rivers, its borders were determined by the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the union of the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland into one sovereign state, established by the Acts of Union 1800, Acts of Union in 1801. It continued in this form until ...

in 1848 when the region was proclaimed as the Orange River Sovereignty

The Orange River Sovereignty (1848–1854; ) was a short-lived political entity between the Orange River, Orange and Vaal rivers in Southern Africa, a region known informally as Transorangia. In 1854, it became the Orange Free State, and is now ...

, with a British Resident

A resident minister, or resident for short, is a government official required to take up permanent residence in another country. A representative of his government, he officially has diplomatic functions which are often seen as a form of in ...

based in Bloemfontein

Bloemfontein ( ; ), also known as Bloem, is the capital and the largest city of the Free State (province), Free State province in South Africa. It is often, and has been traditionally, referred to as the country's "judicial capital", alongsi ...

. Bloemfontein and the southern parts of the Sovereignty had previously been settled by Griqua

Griqua may refer to:

* Griqua people, of South Africa

* Griqua language or Xiri language, their endangered Khoi language

* Griquas (rugby)

Griquas (), known as the Suzuki Griquas for sponsorship reasons, are a South African professional rugby ...

and by '' Trekboere'' from the Cape Colony.

The ''Voortrekker

The Great Trek (, ) was a northward migration of Dutch-speaking settlers who travelled by wagon trains from the Cape Colony into the interior of modern South Africa from 1836 onwards, seeking to live beyond the Cape's British colonial adminis ...

'' Republic of Natalia, founded in 1837, administered the northern part of the territory through a ''landdrost

''Landdrost'' ({{IPA, nl, ˈlɑndrɔst, lang, Nl-landdrost.ogg) was the title of various officials with local jurisdiction in the Netherlands and a number of former territories in the Dutch Empire. The term is a Dutch compound, with ''land'' mean ...

'' based at Winburg

Winburg is a small mixed farming town in the Free State province of South Africa.

It is the oldest proclaimed town (1837) in the Orange Free State, South Africa and along with Griekwastad, is one of the oldest settlements in South Africa loc ...

. This northern area was later in federation with the Republic of Potchefstroom

Potchefstroom ( ; ), colloquially known as Potch, is an college town, academic city in the North West (South African province), North West Province of South Africa. It hosts the Potchefstroom Campus of the North-West University. Potchefstro ...

which eventually formed part of the South African Republic

The South African Republic (, abbreviated ZAR; ), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer republics, Boer republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when it was annexed into the British Empire as a result ...

(Transvaal).

Following the granting of sovereignty to the Transvaal Republic

The South African Republic (, abbreviated ZAR; ), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when it was annexed into the British Empire as a result of the Second ...

, the British sought to drop their defensive and administrative responsibilities between the Orange and Vaal rivers, while local European residents wanted the British to remain. This led to the British recognising the independence of the Orange River Sovereignty and the country officially became independent as the Orange Free State on 23 February 1854, with the signing of the Orange River Convention

The Orange River Convention (sometimes also called the Bloemfontein Convention; ) was a Treaty, convention whereby the British Empire, British formally recognised the independence of the Boers in the area between the Orange River, Orange and Vaal ...

. The new republic incorporated the Orange River Sovereignty and continued the traditions of the Winburg-Potchefstroom Republic.

The Orange Free State was annexed as the Orange River Colony

The Orange River Colony was the British colony created after Britain first occupied (1900) and then annexed (1902) the independent Orange Free State in the Second Boer War. The colony ceased to exist in 1910, when it was absorbed into the Unio ...

in 1900. It ceased to exist as an independent Boer republic on 31 May 1902 with the signing of the Treaty of Vereeniging

The Treaty of Vereeniging was a peace treaty, signed on 31 May 1902, that ended the Second Boer War between the South African Republic and the Orange Free State on the one side, and the United Kingdom on the other.

This settlement provided ...

at the conclusion of the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

. Following a period of direct rule by the British, it attained self-government in 1907 and joined the Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa (; , ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day South Africa, Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the British Cape Colony, Cape, Colony of Natal, Natal, Tra ...

in 1910 as the Orange Free State Province

The Province of the Orange Free State (), commonly referred to as the Orange Free State (), Free State () or by its abbreviation OFS, was one of the four provinces of South Africa from 1910 to 1994. After 27 April 1994 it was dissolved following ...

, along with the Cape Province

The Province of the Cape of Good Hope (), commonly referred to as the Cape Province () and colloquially as The Cape (), was a province in the Union of South Africa and subsequently the Republic of South Africa. It encompassed the old Cape Co ...

, Natal

NATAL or Natal may refer to:

Places

* Natal, Rio Grande do Norte, a city in Brazil

* Natal, South Africa (disambiguation), a region in South Africa

** Natalia Republic, a former country (1839–1843)

** Colony of Natal, a former British colony ( ...

, and the Transvaal

Transvaal is a historical geographic term associated with land north of (''i.e.'', beyond) the Vaal River in South Africa. A number of states and administrative divisions have carried the name ''Transvaal''.

* South African Republic (1856–1902; ...

. In 1961, the Union of South Africa became the Republic of South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

.

The Republic's name derives partly from the Orange River

The Orange River (from Afrikaans/Dutch language, Dutch: ''Oranjerivier'') is a river in Southern Africa. It is the longest river in South Africa. With a total length of , the Orange River Basin extends from Lesotho into South Africa and Namibi ...

, which was named by the Dutch explorer Robert Jacob Gordon

Colonel Robert Jacob Gordon (29 September 1743 – 25 October 1795) was a Dutch army officer, explorer and naturalist.

Early life

Robert Jacob Gordon was born in Doesburg, Gelderland on 29 September 1743. He was the son of Major-General Ja ...

in honour of the Dutch ruling family, the House of Orange

The House of Orange-Nassau (, ), also known as the House of Orange because of the prestige of the princely title of Orange, also referred to as the Fourth House of Orange in comparison with the other noble houses that held the Principality of O ...

, whose name in turn derived from its partial origins in the Principality of Orange

The Principality of Orange (French language, French: Principauté d'Orange) was, from 1163 to 1713, a feudal state in Provence, in the south of modern-day France, on the east bank of the river Rhone, north of the city of Avignon, and surrounded ...

in French Provence. The official language in the Orange Free State was Dutch.

History

First settlements

Europeans first visited the country north of the Orange River towards the close of the 18th century. One of the most notable visitors was the Dutch explorer Robert Jacob Gordon, who mapped the region and gave the Orange River its name. At that time, the population was sparse. The majority of the inhabitants appear to have been members of theSotho people

The Sotho (), also known as the Basotho (), are a Sotho-Tswana peoples, Sotho-Tswana ethnic group indigenous to Southern Africa. They primarily inhabit the regions of Lesotho, South Africa, Botswana and Namibia.

The ancestors of the Sotho peo ...

but in the valleys of the Orange and Vaal were Korana (Khoikhoi

Khoikhoi (Help:IPA/English, /ˈkɔɪkɔɪ/ Help:Pronunciation respelling key, ''KOY-koy'') (or Khoekhoe in Namibian orthography) are the traditionally Nomad, nomadic pastoralist Indigenous peoples, indigenous population of South Africa. They ...

) and a section of Barolong

The Rolong (pronounced ) are a Tswana ethnic group native to Botswana and South Africa.

Etymology

The Rolong people's name originated from the clan's first ''kgosi'' (king, chief) Morolong, who lived around 1270–1280. The ancient word '' ...

in the Drakensberg

The Drakensberg (Zulu language, Zulu: uKhahlamba, Sotho language, Sotho: Maloti, Afrikaans: Drakensberge) is the eastern portion of the Great Escarpment, Southern Africa, Great Escarpment, which encloses the central South Africa#Geography, Sout ...

and on the western border lived numbers of Nomadic Southern Africans. Early in the 19th century Griqua

Griqua may refer to:

* Griqua people, of South Africa

* Griqua language or Xiri language, their endangered Khoi language

* Griquas (rugby)

Griquas (), known as the Suzuki Griquas for sponsorship reasons, are a South African professional rugby ...

established themselves north of the Orange.

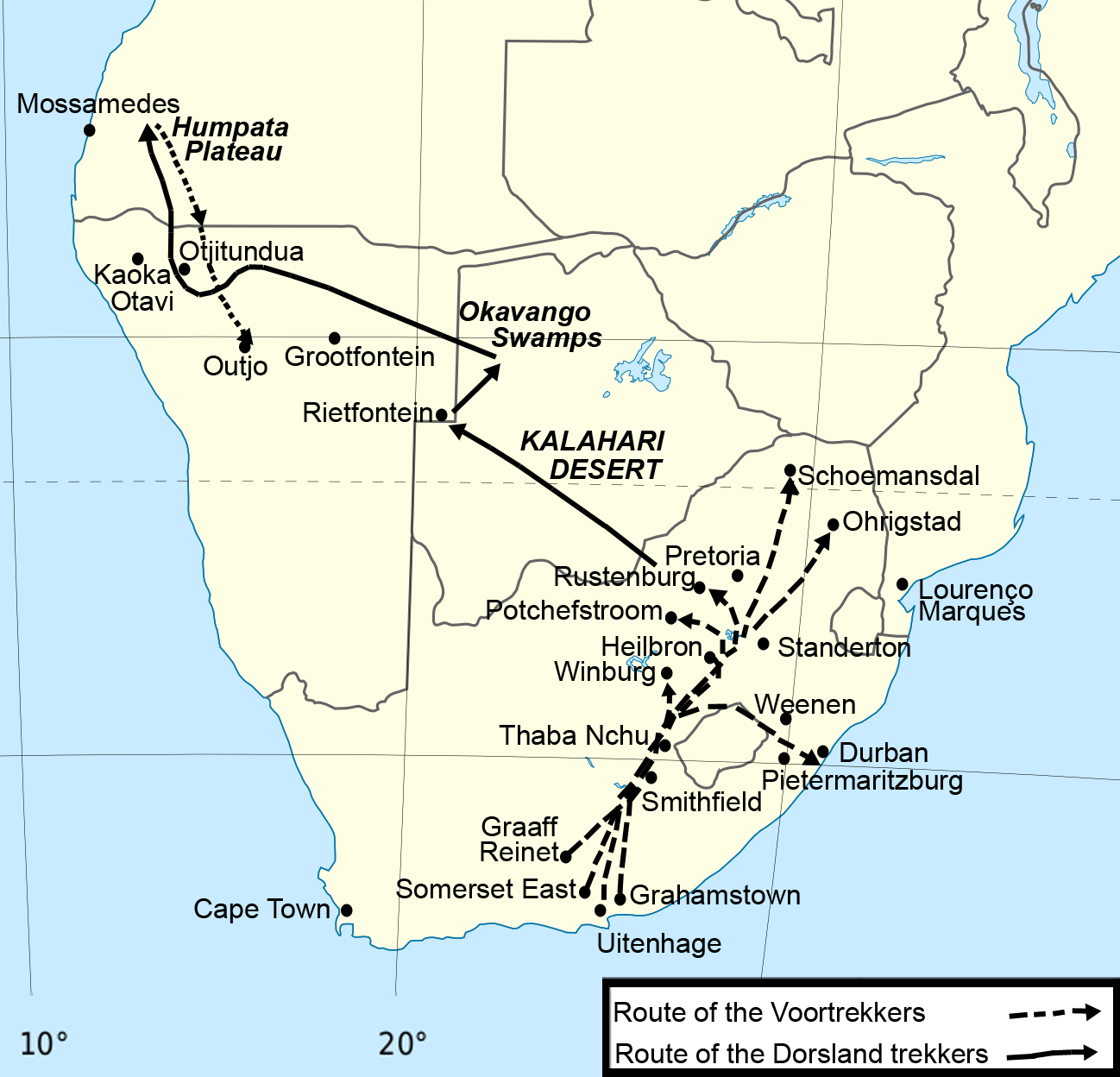

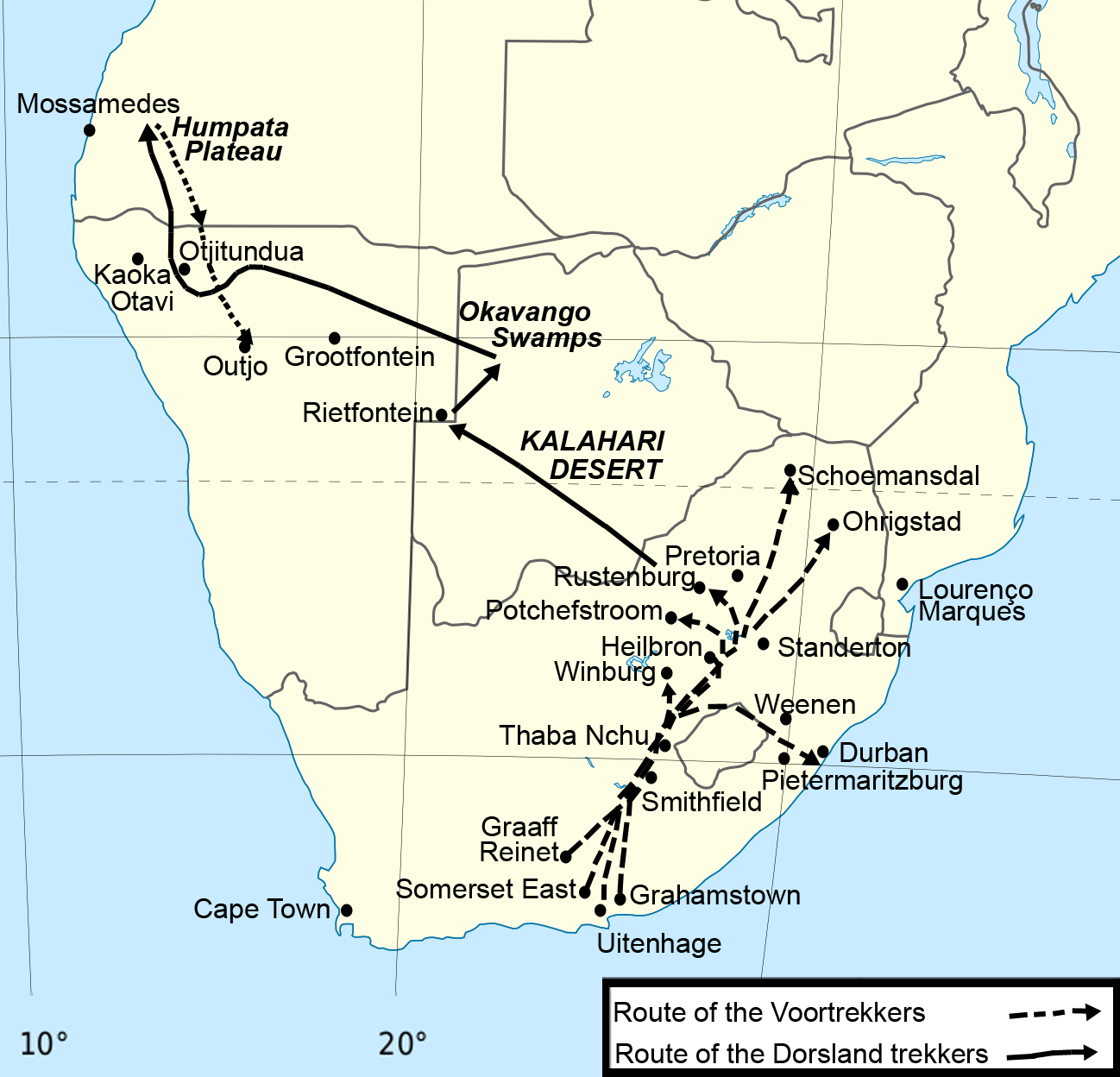

Boer immigration

In 1824 farmers of Dutch,French Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

and German descent known as Trekboers

The Trekboers ( ) were nomadic pastoralists descended from mostly Dutch colonists on the frontiers of the Dutch Cape Colony in Southern Africa. The Trekboers began migrating into the interior from the areas surrounding what is now Cape Town, ...

(later named Boers

Boers ( ; ; ) are the descendants of the proto Afrikaans-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controlled the Dutch ...

by the English) emerged from the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony (), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope. It existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with three ...

, seeking pasture for their flocks and to escape British governmental oversight, settling in the country. Up to this time the few Europeans who had crossed the Orange had come mainly as hunters or as missionaries. These early migrants were followed in 1836 by the first parties of the Great Trek

The Great Trek (, ) was a northward migration of Dutch-speaking settlers who travelled by wagon trains from the Cape Colony into the interior of modern South Africa from 1836 onwards, seeking to live beyond the Cape's British colonial adminis ...

. These emigrants left the Cape Colony for various reasons, but all shared the desire for independence from British authority. The leader of the first large party, Hendrik Potgieter

Andries Hendrik Potgieter, known as Hendrik Potgieter (19 December 1792 – 16 December 1852) was a Voortrekker leader. He served as the first head of state of Potchefstroom from 1840 and 1845 and also as the first head of state of Zoutpansberg ...

, concluded an agreement with Makwana

The Makwana are a Hindu and Muslim community of Gujarat.

The Makwana Muslims are now mainly small peasant proprietors found in north Gujarat. According to their traditions, their ancestor Bapuji, the son of Harpal Makwana, converted to Islam. He ...

, the chief of the Bataung

The Taung tribe or Bataung is a tribe of Bantu origin which speaks the Sotho-Tswana group of languages, namely, Setswana, Sepedi, Sesotho and Lozi.

"Tau" is a Sotho-Tswana word meaning "Lion", and this animal is their totem. "Bataung" is ...

tribe of Batswana, ceding to the farmers the country between the Vet and Vaal

The Vaal River ( ; Khoemana: ) is the largest tributary of the Orange River in South Africa. The river has its source near Breyten in Mpumalanga province, east of Johannesburg and about north of Ermelo and only about from the Indian Oce ...

rivers. When Boer families first reached the area they discovered that the country had been devastated, in the northern parts by the chief Mzilikazi

Mzilikazi Moselekatse, Khumalo ( 1790 – 9 September 1868) was a Southern African king who founded the Ndebele Kingdom now called Matebeleland which is now part of Zimbabwe. His name means "the great river of blood". He was born the son of M ...

and his Matabele in what was known as the Mfecane

The Mfecane, also known by the Sesotho names Difaqane or Lifaqane (all meaning "crushing," "scattering," "forced dispersal," or "forced migration"), was a historical period of heightened military conflict and migration associated with state fo ...

, and also by the Difaqane

The Mfecane, also known by the Sesotho names Difaqane or Lifaqane (all meaning "crushing," "scattering," "forced dispersal," or "forced migration"), was a historical period of heightened military conflict and migration associated with state fo ...

, in which three tribes roamed across the land attacking settled groups, absorbing them and their resources until they collapsed because of their sheer size. Consequently, large areas were depopulated. The Boers soon came into collision with Mzilikazi's raiding parties, which attacked Boer hunters who crossed the Vaal River. Reprisals followed, and in November 1837 the Boers decisively defeated Mzilikazi, who thereupon fled northward and eventually established himself on the site of the future Bulawayo

Bulawayo (, ; ) is the second largest city in Zimbabwe, and the largest city in the country's Matabeleland region. The city's population is disputed; the 2022 census listed it at 665,940, while the Bulawayo City Council claimed it to be about ...

in Zimbabwe.

In the meantime another party of Cape Dutch emigrants had settled at Thaba Nchu

Thaba 'Nchu, also known as Blesberg (''bald mountain'' in Afrikaans), is a town in Free State, South Africa, 63 km east of Bloemfontein and 17 km east of Botshabelo. The population is largely made up of Tswana and Sotho people. The to ...

, where the Wesleyans

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a Protestant Christian tradition whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's brother Charles Wesley were also significa ...

had a mission station for the Barolong

The Rolong (pronounced ) are a Tswana ethnic group native to Botswana and South Africa.

Etymology

The Rolong people's name originated from the clan's first ''kgosi'' (king, chief) Morolong, who lived around 1270–1280. The ancient word '' ...

. These Barolong had trekked from their original home under their chief, Moroka II, first south-westwards to the Langberg, and then eastwards to Thaba Nchu. The emigrants were treated with great kindness by Moroka, and with the Barolong the Boers maintained uniformly friendly relations after they defeated Mzilikazi. In December 1836 the emigrants beyond the Orange drew up in general assembly an elementary republican form of government. After the defeat of Mzilikazi the town of Winburg

Winburg is a small mixed farming town in the Free State province of South Africa.

It is the oldest proclaimed town (1837) in the Orange Free State, South Africa and along with Griekwastad, is one of the oldest settlements in South Africa loc ...

(so named by the Boers in commemoration of their victory) was founded, a Volksraad The Volksraad was a people's assembly or legislature in Dutch or Afrikaans speaking government.

Assembly South Africa

* Volksraad (South African Republic) (1840–1902)

* Volksraad (Natalia Republic), a similar assembly that existed in the Natalia ...

elected, and Piet Retief

Pieter Mauritz Retief (12 November 1780 – 6 February 1838) was a '' Voortrekker'' leader. Settling in 1814 in the frontier region of the Cape Colony, he later assumed command of punitive expeditions during the sixth Xhosa War. He became a s ...

, one of the ablest of the Voortrekkers, chosen "governor and commandant-general". The emigrants already numbered some 500 men, besides women and children and many servants. Dissensions speedily arose among the emigrants, whose numbers were constantly added to, and Retief, Potgieter and other leaders crossed the Drakensberg

The Drakensberg (Zulu language, Zulu: uKhahlamba, Sotho language, Sotho: Maloti, Afrikaans: Drakensberge) is the eastern portion of the Great Escarpment, Southern Africa, Great Escarpment, which encloses the central South Africa#Geography, Sout ...

and entered Natal

NATAL or Natal may refer to:

Places

* Natal, Rio Grande do Norte, a city in Brazil

* Natal, South Africa (disambiguation), a region in South Africa

** Natalia Republic, a former country (1839–1843)

** Colony of Natal, a former British colony ( ...

. Those that remained were divided into several parties.

British rule

Meanwhile, a new power had arisen along the upper Orange and in the valley of the Caledon. Moshoeshoe, a minorBasotho

The Sotho (), also known as the Basotho (), are a Sotho-Tswana ethnic group indigenous to Southern Africa. They primarily inhabit the regions of Lesotho, South Africa, Botswana and Namibia.

The ancestors of the Sotho people are believed to h ...

chief, had welded together a number of scattered and broken clans which had sought refuge in that mountainous region after fleeing from Mzilikazi, and had formed the Basotho nation which acknowledged him as king. In 1833 he had welcomed as workers among his people a band of French Protestant missionaries, and as the Boer immigrants began to settle in his neighborhood he decided to seek support from the British at the Cape. At that time the British government was not prepared to exercise control over the immigrants. Acting upon the advice of Dr John Philip, the superintendent of the London Missionary Society

The London Missionary Society was an interdenominational evangelical missionary society formed in England in 1795 at the instigation of Welsh Congregationalist minister Edward Williams. It was largely Reformed tradition, Reformed in outlook, with ...

’s stations in South Africa, a treaty was concluded in 1843 with Moshoeshoe, placing him under British protection. A similar treaty was made with the Griqua chief Adam Kok III

Adam Kok III (16 October 1811 – 30 December 1875) was a leader of the Griqua people in South Africa.

Early life

The son of Adam Kok II, he was born in Griqualand West. Kok III was educated at the Philippolis Mission School after his family ...

. By these treaties, which recognised native sovereignty, the British sought to keep a check on the Boers and to protect both the natives and Cape Colony. The effect was to precipitate collisions between all three parties.

The year in which the treaty with Moshoeshoe was made, several large parties of Boers recrossed the Drakensberg

The Drakensberg (Zulu language, Zulu: uKhahlamba, Sotho language, Sotho: Maloti, Afrikaans: Drakensberge) is the eastern portion of the Great Escarpment, Southern Africa, Great Escarpment, which encloses the central South Africa#Geography, Sout ...

into the country north of the Orange, refusing to remain in Natal

NATAL or Natal may refer to:

Places

* Natal, Rio Grande do Norte, a city in Brazil

* Natal, South Africa (disambiguation), a region in South Africa

** Natalia Republic, a former country (1839–1843)

** Colony of Natal, a former British colony ( ...

when the British annexed the newly formed Boer republic of Natalia to form the Colony of Natal

The Colony of Natal was a British colony in south-eastern Africa. It was proclaimed a British colony on 4 May 1843 after the British government had annexed the Boer Republic of Natalia, and on 31 May 1910 combined with three other colonies t ...

. During their stay in Natal the Boers inflicted a severe defeat on the Zulus under Dingane

Dingane ka Senzangakhona Zulu (–29 January 1840), commonly referred to as Dingane, Dingarn or Dingaan, was a Zulu prince who became king of the Zulu Kingdom in 1828, after assassinating his half-brother Shaka Zulu. He set up his royal capita ...

in the Battle of Blood River

The Battle of Blood River or Voortrekker-Zulu War (16 December 1838) was fought on the bank of the Blood River, Ncome River, in what is today KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa between 464 Voortrekkers ("Pioneers"), led by Andries Pretorius, and an es ...

in December 1838, which, following on the flight of Mzilikazi

Mzilikazi Moselekatse, Khumalo ( 1790 – 9 September 1868) was a Southern African king who founded the Ndebele Kingdom now called Matebeleland which is now part of Zimbabwe. His name means "the great river of blood". He was born the son of M ...

, greatly strengthened the position of Moshoeshoe, whose power became a menace to that of the Boer farmers. Trouble first arose, however, between the Boers and the Griqua in the Philippolis

Philippolis is a town in the Free State province of South Africa. The town is the birthplace of writer and intellectual Sir Laurens van der Post, actress Brümilda van Rensburg and Springboks rugby player Adriaan Strauss. It is regarded as o ...

district. Some of the Boer farmers in this district, unlike their fellows dwelling farther north, were willing to accept British rule. This fact induced Mr Justice Menzies, one of the judges of the Cape Colony then on circuit at Colesberg

Colesberg is a town with 17,354 inhabitants in the Northern Cape province of South Africa, located on the main N1 road from Cape Town to Johannesburg.

In a sheep-farming area spread over half-a-million hectares, greater Colesberg breeds ma ...

, to cross the Orange and proclaim the country British territory in October 1842. The proclamation was disallowed by the Governor, Sir George Napier

Colonel George Napier (11 March 1751 – 13 October 1804), styled "The Honourable", was a British Army officer, most notable for his marriage to Lady Sarah Lennox, and for his sons Charles James Napier, William Francis Patrick Napier and George ...

, who, nevertheless, maintained that the Boer farmers remained British subjects. After this episode the British negotiated their treaties with Adam Kok III

Adam Kok III (16 October 1811 – 30 December 1875) was a leader of the Griqua people in South Africa.

Early life

The son of Adam Kok II, he was born in Griqualand West. Kok III was educated at the Philippolis Mission School after his family ...

and Moshoeshoe.

The treaties gave great offence to the Boers, who refused to acknowledge the sovereignty of the native chiefs. The majority of the Boer farmers in Kok's territory sent a deputation to the British commissioner in Natal, Henry Cloete, asking for equal treatment with the Griquas

The Griquas are a subgroup of mixed-race heterogeneous formerly-Xiri-speaking nations in South Africa with a unique origin in the early history of the Dutch Cape Colony. Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Comm ...

, and expressing the desire to come under British protection under such terms. Shortly afterwards hostilities between the farmers and the Griqua broke out. British troops moved up to support the Griquas, and after a skirmish at Zwartkopjes (2 May 1845) a new arrangement was made between Kok and Peregrine Maitland

General Sir Peregrine Maitland, GCB (6 July 1777 – 30 May 1854) was a British army officer and colonial administrator. He also was a first-class cricketer from 1798 to 1808 and an early advocate for the establishment of what would become the C ...

, the then Governor of Cape Colony

This article lists the governors of British South African colonies, including the colonial prime ministers. It encompasses the period from 1797 to 1910, when present-day South Africa was divided into four British Empire, British colonies namely ...

, virtually placing the administration of his territory in the hands of a British resident, a post filled in 1846 by Captain Henry Douglas Warden. The place purchased by Captain (afterwards Major) Warden as the seat of his court was known as Bloemfontein

Bloemfontein ( ; ), also known as Bloem, is the capital and the largest city of the Free State (province), Free State province in South Africa. It is often, and has been traditionally, referred to as the country's "judicial capital", alongsi ...

, and it subsequently became the capital of the whole country. Bloemfontein lay to the south of the region settled by Voortrekkers.

Boer governance

The Volksraad at Winburg during this period continued to claim jurisdiction over the Boers living between the Orange and the Vaal and was in federation with the Volksraad atPotchefstroom

Potchefstroom ( ; ), colloquially known as Potch, is an college town, academic city in the North West (South African province), North West Province of South Africa. It hosts the Potchefstroom Campus of the North-West University. Potchefstro ...

, which made a similar claim upon the Great Boers living north of the Vaal. In 1846 Major Warden occupied Winburg for a short time, and the relations between the Boers and the British were in a continual state of tension. Many of the farmers deserted Winburg for the Transvaal. Sir Harry Smith

Lieutenant-General Sir Henry George Wakelyn Smith, 1st Baronet, GCB (28 June 1787 – 12 October 1860) was a notable English soldier and military commander in the British Army of the early 19th century. A veteran of the Napoleonic Wars, he is a ...

became governor of the Cape at the end of 1847. He recognised the failure of the attempt to govern on the lines of the treaties with the Griquas and Basotho, and on 3 February 1848 he issued a proclamation declaring British sovereignty over the country between the Orange and the Vaal eastward to the Drakensberg. Sir Harry Smith's popularity among the Boers gained for his policy considerable support, but the republican party, at whose head was Andries Pretorius

Andries Wilhelmus Jacobus Pretorius (27 November 179823 July 1853) was a leader of the Boers who was instrumental in the creation of the South African Republic, as well as the earlier but short-lived Natalia Republic, in present-day South Africa ...

, did not submit without a struggle. They were, however, defeated by Sir Harry Smith in the Battle of Boomplaats

The Battle of Boomplaats (also referred to as the Battle of Boomplaas) was fought near Jagersfontein at on 29 August 1848 between the British and the Voortrekkers. The British were led by Sir Harry Smith, while the Boers were led by Andries Pre ...

on 29 August 1848. Thereupon Pretorius, with those most bitterly opposed to British rule, retreated across the Vaal.

Orange River Sovereignty

In March 1849 Major Warden was succeeded at Bloemfontein as civil commissioner by Mr C. U. Stuart, but he remained the British resident until July 1852. A nominated legislative council was created, a high court established and other steps taken for the orderly government of the country, which was officially styled theOrange River Sovereignty

The Orange River Sovereignty (1848–1854; ) was a short-lived political entity between the Orange River, Orange and Vaal rivers in Southern Africa, a region known informally as Transorangia. In 1854, it became the Orange Free State, and is now ...

. In October 1849 Moshoeshoe was induced to sign a new arrangement considerably curtailing the boundaries of the Basotho reserve. The frontier towards the Sovereignty was thereafter known as the Warden line. A little later the reserves of other chieftains were precisely defined.

The British Resident had, however, no force sufficient to maintain his authority, and Moshoeshoe and all the neighboring clans became involved in hostilities with one another and with the Europeans. In 1851 Moshoeshoe joined the republican party in the Sovereignty in an invitation to Pretorius to recross the Vaal. The intervention of Pretorius resulted in the Sand River Convention

The Sand River Convention () of 17 January 1852 was a Treaty, convention whereby the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland formally recognised the independence of the Boers north of the Vaal River.

Background

The convention was signed o ...

of 1852, which acknowledged the independence of the Transvaal

Transvaal is a historical geographic term associated with land north of (''i.e.'', beyond) the Vaal River in South Africa. A number of states and administrative divisions have carried the name ''Transvaal''.

* South African Republic (1856–1902; ...

but left the status of the Sovereignty untouched. The British government (under the first Russell administration), which had reluctantly agreed to the annexation of the country, had, however, already repented its decision and had resolved to abandon the Sovereignty. Lord Henry Grey, Secretary of State for War and the Colonies

The Secretary of State for War and the Colonies was a British cabinet-level position responsible for the army and the British colonies (other than India). The Secretary was supported by an Under-Secretary of State for War and the Colonies.

Hist ...

, in a dispatch to Sir Harry Smith dated 21 October 1851, declared, "The ultimate abandonment of the Orange Sovereignty should be a settled point in our policy."

A meeting of representatives of all European inhabitants of the Sovereignty, elected on manhood suffrage, held at Bloemfontein in June 1852, nevertheless declared in favour of the retention of British rule. At the close of that year a settlement was at length concluded with Moshoeshoe, which left, perhaps, that chief in a stronger position than he had hitherto been. There had been ministerial changes in England and the Aberdeen ministry

After the collapse of Lord Derby's minority government, the Whigs and Peelites formed a coalition under the Peelite leader George Hamilton-Gordon, 4th Earl of Aberdeen. The government resigned in early 1855 after a large parliamentary majorit ...

, then in power, adhered to the determination to withdraw from the Sovereignty. Sir George Russell Clerk

Sir George Russell Clerk (pronounced ''Clark''; – 25 July 1889) was a British civil servant in British India.

Life

Clerk was born at Worting House in Mortimer West End, Hampshire,''1851 England Census'' the son of John Clerk of Glouces ...

was sent out in 1853 as special commissioner "for the settling and adjusting of the affairs" of the Sovereignty, and in August of that year he summoned a meeting of delegates to determine upon a form of self-government.

At that time there were some 15,000 Europeans in the country, many of them recent immigrants from Cape Colony. There were among them numbers of farmers and tradesmen of British descent. The majority of the whites still wished for the continuance of British rule provided that it was effective and the country guarded against its enemies. The representations of their delegates, who drew up a proposed constitution retaining British control, were unavailing. Sir George Clerk announced that, as the elected delegates were unwilling to take steps to form an independent government, he would enter into negotiations with other persons. " And then," wrote George McCall Theal, "was seen forced the strange spectacle of an English commissioner addressing men who wished to be free of British control as the friendly and well-disposed inhabitants, while for those who desired to remain British subjects and who claimed that protection to which they believed themselves entitled he had no sympathising word."G. McCall Theal, History of South Africa since 1795 p to 1872 vols. ii., iii. and iv. (1908 ed.), quoted in While the elected delegates sent two members to England to try and induce the government to alter their decision, Sir George Clerk speedily came to terms with a committee formed by the republican party and presided over by Mr J. H. Hoffman. Even before this committee met a royal proclamation had been signed (30 January 1854) "abandoning and renouncing all dominion" in the Sovereignty.

The Orange River Convention

The Orange River Convention (sometimes also called the Bloemfontein Convention; ) was a Treaty, convention whereby the British Empire, British formally recognised the independence of the Boers in the area between the Orange River, Orange and Vaal ...

, recognising the independence of the country, was signed at Bloemfontein on 23 February by Sir George Clerk and the republican committee, and in March the Boer government assumed office and the republican flag was hoisted. Five days later the representatives of the elected delegates had an interview in London with the colonial secretary, the Duke of Newcastle

Duke of Newcastle upon Tyne was a title that was created three times, once in the Peerage of England and twice in the Peerage of Great Britain. The first grant of the title was made in 1665 to William Cavendish, 1st Duke of Newcastle, Willi ...

, who informed them that it was now too late to discuss the question of the retention of British rule. The colonial secretary added that it was impossible for England to supply troops to constantly advancing outposts, "especially as Cape Town

Cape Town is the legislature, legislative capital city, capital of South Africa. It is the country's oldest city and the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. Cape Town is the country's List of municipalities in South Africa, second-largest ...

and the port of Table Bay

Table Bay (Afrikaans: ''Tafelbaai'') is a natural bay on the Atlantic Ocean overlooked by Cape Town and is at the northern end of the Cape Peninsula, which stretches south to the Cape of Good Hope. It was named because it is dominated by the fl ...

were all she really required in South Africa." In withdrawing from the Sovereignty the British government declared that it had "no alliance with any native chief or tribes to the northward of the Orange River with the exception of the Griqua chief Captain Adam Kok II. Kok was not formidable in a military sense, nor could he prevent individual Griquas from alienating their lands. Eventually, in 1861, he sold his sovereign rights to the Free State for £4000 and moved with his followers to the district later known as Griqualand East

Griqualand East (Afrikaans: ''Griekwaland-Oos''), officially known as New Griqualand ( Dutch: ''Nieuw Griqualand''), was one of four short-lived Griqua states in Southern Africa from the early 1860s until the late 1870s and was located between ...

.

On the abandonment of British rule, representatives of the people were elected and met at Bloemfontein on 28 March 1854, and between then and 18 April were engaged in framing a constitution. The country was declared a republic and named the Orange Free State. All persons of European blood possessing a six months' residential qualification were to be granted full burgher rights. The sole legislative authority was vested in a single popularly elected chamber of the Volksraad The Volksraad was a people's assembly or legislature in Dutch or Afrikaans speaking government.

Assembly South Africa

* Volksraad (South African Republic) (1840–1902)

* Volksraad (Natalia Republic), a similar assembly that existed in the Natalia ...

. Executive authority was entrusted to a president elected by the burghers from a list submitted by the Volksraad. The president was to be assisted by an executive council, was to hold office for five years and was eligible for re-election. The constitution was subsequently modified but remained of a liberal character. A residence of five years in the country was required before aliens could become naturalised. The first president was Josias Philip Hoffman

Josias Philip Hoffman (commonly known as Sias Hoffman) (1807 – 1879) was a South African Boer statesman, and was the chairman of the Provisional Government and later the first State President of the Orange Free State, in office from 1854 ...

, but he was accused of being too complaisant towards Moshoeshoe and resigned, being succeeded in 1855 by Jacobus Nicolaas Boshoff

Jacobus Nicolaas Boshof (31 January 1808 – 21 April 1881) was a South African (Boer) statesman, a late-arriving member of the Voortrekker movement, and the second state president of the Orange Free State, in office from 1855 to 1859.

Biogra ...

, one of the voortrekkers, who had previously taken an active part in the affairs of the Natalia Republic

The Natalia Republic was a short-lived Boer republic founded in 1839 after a Voortrekker victory against the Zulus at the Battle of Blood River. The area was previously named ''Natália'' by Portuguese sailors, due to its discovery on Christm ...

.

Conflict with the South African Republic

Distracted among themselves, with the formidable Basotho power on their southern and eastern flank, the troubles of the infant state were speedily added to by the action of the Transvaal Boers of the

Distracted among themselves, with the formidable Basotho power on their southern and eastern flank, the troubles of the infant state were speedily added to by the action of the Transvaal Boers of the South African Republic

The South African Republic (, abbreviated ZAR; ), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer republics, Boer republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when it was annexed into the British Empire as a result ...

. Marthinus Pretorius

Marthinus Wessel Pretorius (17 September 1819 – 19 May 1901) was a South African political leader. An Afrikaner (or "Boer"), he helped establish the South African Republic (''Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek'' or ZAR; also referred to as Transvaa ...

, who had succeeded to his father's position as commandant general of Potchefstroom, wished to bring about a confederation between the two Boer states. Peaceful overtures from Pretorius were declined, and some of his partisans in the Orange Free State were accused of treason in February 1857. Thereupon Pretorius, aided by Paul Kruger

Stephanus Johannes Paulus Kruger (; 10 October 1825 – 14 July 1904), better known as Paul Kruger, was a South African politician. He was one of the dominant political and military figures in 19th-century South Africa, and State Preside ...

, conducted a raid into the Orange Free State's territory. On learning of the invasion, President Jacobus Nicolaas Boshoff

Jacobus Nicolaas Boshof (31 January 1808 – 21 April 1881) was a South African (Boer) statesman, a late-arriving member of the Voortrekker movement, and the second state president of the Orange Free State, in office from 1855 to 1859.

Biogra ...

proclaimed martial law throughout the country. The majority of the burghers rallied to his support, and on 25 May, the two opposing forces faced one another on the banks of the Rhenoster. President Boshoff not only got together some 800 men within the Orange Free State, but he received offers of support from Commandant Stephanus Schoeman

Stephanus Schoeman (14 March 1810 – 19 June 1890) was President of the South African Republic from 6 December 1860 until 17 April 1862. His red hair, fiery temperament and vehement disputes with other Boer leaders earned him th ...

, the Transvaal leader in the Zoutpansberg

Zoutpansberg was the north-eastern division of the Transvaal, South Africa, encompassing an area of 25,654 square miles. The chief towns at the time were Pietersburg and Leydsdorp. It was divided into two districts (west and east) prior to the ...

district and from Commandant Joubert of Lydenburg

Lydenburg, also known as Mashishing, is a town in Thaba Chweu Local Municipality, on the Mpumalanga highveld, South Africa. It is situated on the Sterkspruit/Dorps River tributary of the Lepelle River at the summit of the Long Tom Pass. It h ...

. Pretorius and Kruger, realising that they would have to sustain attack from both north and south, abandoned their enterprise. Their force, too, only amounted to some three hundred. Kruger came to Boshoff's camp with a flag of truce, the "army" of Pretorius returned north and on 2 June a treaty of peace was signed, each state acknowledging the absolute independence of the other.

The conduct of Pretorius was stigmatised as "blameworthy." Several of the malcontents in the Orange Free State who had joined Pretorius permanently settled in the Transvaal, and other Orange Free Staters who had been guilty of high treason were arrested and punished. This experience did not, however, heal the party strife within the Orange Free State. In consequence of the dissensions among the burghers, President Boshoff tendered his resignation in February 1858, but was for a time induced to remain in office. The difficulties of the state were at that time so great that the Volksraad in December 1858 passed a resolution in favour of confederation with the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony (), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope. It existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with three ...

. This proposition received the strong support of Sir George Grey

Sir George Grey, KCB (14 April 1812 – 19 September 1898) was a British soldier, explorer, colonial administrator and writer. He served in a succession of governing positions: Governor of South Australia, twice Governor of New Zealand, Gov ...

, the then Governor of Cape Colony, but his view did not commend itself to the British government, and was not adopted.

In the same year, the disputes between the Basotho and the Boers culminated in open war. Both parties laid claims to land beyond the Warden line, and each party had taken possession of what it could, the Basotho being also expert cattle-lifters. In the war the advantage rested with the Basotho; thereupon the Orange Free State appealed to Sir George Grey, who induced Moshoeshoe to come to terms. On 15 October 1858, a treaty was signed defining the new boundary. The peace was nominal only, while the burghers were also involved in disputes with other tribes. Mr. Boshoff again tendered his resignation in February 1859 and retired to Natal

NATAL or Natal may refer to:

Places

* Natal, Rio Grande do Norte, a city in Brazil

* Natal, South Africa (disambiguation), a region in South Africa

** Natalia Republic, a former country (1839–1843)

** Colony of Natal, a former British colony ( ...

. Many of the burghers would have at this time welcomed union with the Transvaal

Transvaal is a historical geographic term associated with land north of (''i.e.'', beyond) the Vaal River in South Africa. A number of states and administrative divisions have carried the name ''Transvaal''.

* South African Republic (1856–1902; ...

, but learning from Sir George Grey that such a union would nullify the conventions of 1852 and 1854 and necessitate the reconsideration of Great Britain's policy towards the native tribes north of the Orange and Vaal rivers, the project was dropped. Commandant Marthinus Wessel Pretorius

Marthinus Wessel Pretorius (17 September 1819 – 19 May 1901) was a South African political leader. An Afrikaners, Afrikaner (or "Boer"), he helped establish the South African Republic (''Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek'' or ZAR; also referred to ...

was, however, elected president in place of Boshoff. Though unable to effect a durable peace with the Basotho, or to realise his ambition for the creation of a single united Boer republic, Pretorius oversaw a period of increased strength and prosperity for the Orange Free State. The fertile district of Bethulie

Bethulie is a small sheep and cattle farming town in the Free State province of South Africa. It is located about 100 km/62 miles away from Springfontein. The name meaning ''chosen by God'' was given by directors of a mission station in 1829 which ...

as well as Adam Kok's territory was acquired, and there was a considerable increase in the Boer population. The burghers generally, however, had little confidence in their elected rulers and little desire for taxes to be levied. Wearied like Boshoff, and disillusioned with the affairs of the Orange Free State, Pretorius resigned the presidency in 1863 and moved to the Transvaal.

After an interval of seven months, Johannes Brand

Sir Johannes Henricus Brand, (popularly known as Sir Jan Brand and sometimes as Sir John Henry Brand or Jan Henrick Brand; 6 December 1823 – 14 July 1888) was a lawyer and politician who served as the fourth President (government title), ...

, an advocate at the Cape bar, was elected president. He assumed office in February 1864. His election proved a turning-point in the history of the country, which, under his guidance, became peaceful and prosperous. But before peace could be established an end had to be made of the difficulties with the Basothos. Moshoeshoe continued to menace the Free State border. Attempts at accommodation made by the Governor of Cape Colony, Sir Philip Wodehouse, failed, and war between the Orange Free State and Moshoeshoe was renewed in 1865. The Boers gained considerable successes, and this induced Moshoeshoe to sue for peace. The terms exacted were, however, too harsh for a nation yet unbroken to accept permanently. A treaty was signed at Thaba Bosiu

Thaba Bosiu is a Constituencies of Lesotho, constituency and sandstone plateau with an area of approximately and a height of 1,804 meters above sea level. It is located between the Orange River, Orange and Caledon Rivers in the Maseru District of ...

in April 1866, but war again broke out in 1867, and the Free State attracted to its side a large number of adventurers from all parts of South Africa. The burghers thus reinforced gained at length a decisive victory over their great antagonist, every stronghold in Basutoland

Basutoland was a British Crown colony that existed from 1884 to 1966 in present-day Lesotho, bordered with the Cape Colony, Natal Colony and Orange River Colony until 1910 and completely surrounded by South Africa from 1910. Though the Basot ...

save Thaba Bosiu

Thaba Bosiu is a Constituencies of Lesotho, constituency and sandstone plateau with an area of approximately and a height of 1,804 meters above sea level. It is located between the Orange River, Orange and Caledon Rivers in the Maseru District of ...

being stormed. Moshoeshoe now turned to Sir Philip Wodehouse for preservation. His call was heeded, and in 1868 he and his country were taken under British protection. Thus the thirty years' strife between the Basothos and the Boers came to an end. The intervention of the Governor of Cape Colony led to the conclusion of the treaty of Aliwal North (12 February 1869), which defined the borders between the Orange Free State and Basutoland. The country lying to the north of the Orange River

The Orange River (from Afrikaans/Dutch language, Dutch: ''Oranjerivier'') is a river in Southern Africa. It is the longest river in South Africa. With a total length of , the Orange River Basin extends from Lesotho into South Africa and Namibi ...

and west of the Caledon River

The Caledon River () is a major river located in central South Africa. Its total length is , rising in the Drakensberg Mountains on the Lesotho border, flowing southwestward and then westward before joining the Orange River near Bethulie in the ...

, formerly a part of Basutoland

Basutoland was a British Crown colony that existed from 1884 to 1966 in present-day Lesotho, bordered with the Cape Colony, Natal Colony and Orange River Colony until 1910 and completely surrounded by South Africa from 1910. Though the Basot ...

, was ceded to the Orange Free State, and became known as the Conquered Territory.

A year after the addition of the Conquered Territory to the state another boundary dispute was settled by the arbitration of Robert William Keate

Robert William Keate (16 June 1814 – 17 March 1873) was a career British colonial governor, serving as Commissioner of the Seychelles from 1850 to 1852, Governor of Trinidad from 1857 to 1864, Lieutenant-governor of the Colony of Natal from ...

, lieutenant-governor of Natal

NATAL or Natal may refer to:

Places

* Natal, Rio Grande do Norte, a city in Brazil

* Natal, South Africa (disambiguation), a region in South Africa

** Natalia Republic, a former country (1839–1843)

** Colony of Natal, a former British colony ( ...

. By the Sand River Convention

The Sand River Convention () of 17 January 1852 was a Treaty, convention whereby the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland formally recognised the independence of the Boers north of the Vaal River.

Background

The convention was signed o ...

, independence had been granted to the Boers living "north of the Vaal", and the dispute turned on the question as to what stream constituted the true upper course of that river. Keate decided on 19 February 1870 against the Free State and fixed the Klip River as the dividing line, the Transvaal thus securing the Wakkerstroom

Wakkerstroom (''Awake Stream'') is the second oldest town in Mpumalanga province, South Africa. The town is on the KwaZulu-Natal border, 27 km east of Volksrust and 56 km south-east of Amersfoort.

History

The settlement was laid out o ...

and adjacent districts.

Diamonds discovered

The Basutoland difficulties were no sooner arranged than the Free Staters found themselves confronted with a serious difficulty on their western border. In the years 1870–1871 a large number of foreign diggers had settled on the diamond fields near the junction of the Vaal and Orange rivers, which were situated in part on land claimed by theGriqua

Griqua may refer to:

* Griqua people, of South Africa

* Griqua language or Xiri language, their endangered Khoi language

* Griquas (rugby)

Griquas (), known as the Suzuki Griquas for sponsorship reasons, are a South African professional rugby ...

chief Nicholas Waterboer and by the Orange Free State.

The Free State established a temporary government over the diamond fields, but the administration of this body was satisfactory neither to the Free State nor to the diggers. At this juncture Waterboer offered to place the territory under the administration of Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

. The offer was accepted, and on 27 October 1871 the district, together with some adjacent territory to which the Transvaal had laid claim, was proclaimed, under the name of Griqualand West

Griqualand West is an area of central South Africa with an area of 40,000 km2 that now forms part of the Northern Cape Province. It was inhabited by the Griqua people – a semi-nomadic, Afrikaans-speaking nation of mixed-race origin, w ...

, British territory. Waterboer's claims were based on the treaty concluded by his father with the British in 1834, and on various arrangements with the Kok chiefs; the Free State based its claim on its purchase of Adam Kok's sovereign rights and on long occupation. The difference between proprietorship and sovereignty was confused or ignored. That Waterboer exercised no authority in the disputed district was admitted. When the British annexation took place a party in the Volksraad wished to go to war with Britain, but the counsels of President Johannes Brand

Sir Johannes Henricus Brand, (popularly known as Sir Jan Brand and sometimes as Sir John Henry Brand or Jan Henrick Brand; 6 December 1823 – 14 July 1888) was a lawyer and politician who served as the fourth President (government title), ...

prevailed. The Free State, however, did not abandon its claims. The matter involved no little irritation between the parties concerned until July 1876. It was then disposed of by Henry Herbert, 4th Earl of Carnarvon

Henry Howard Molyneux Herbert, 4th Earl of Carnarvon, (24 June 1831 – 29 June 1890), known as Lord Porchester from 1833 to 1849, was a British politician and a leading member of the Conservative Party. He was twice Secretary of State for the ...

, at that time Secretary of State for the Colonies

The secretary of state for the colonies or colonial secretary was the Cabinet of the United Kingdom's government minister, minister in charge of managing certain parts of the British Empire.

The colonial secretary never had responsibility for t ...

, who granted to the Free State a £90,000 payment "in full satisfaction of all claims which it considers it may possess to Griqualand West." Lord Carnarvon declined to entertain the proposal made by Mr Brand that the territory should be given up by Great Britain. In the opinion of historian George McCall Theal, the annexation of Griqualand West was probably in the best interests of the Free State. "There was," he stated, "no alternative from British sovereignty other than an independent diamond field republic."

At this time, largely owing to the struggle with the Basothos, the Free State Boers, like their Transvaal neighbors, had drifted into financial straits. A paper currency had been instituted, and the notes, known as "bluebacks", soon dropped to less than half their nominal value. Commerce was largely carried on by barter, and many cases of bankruptcy occurred in the state. The influx of British and other immigrants to the diamond fields, in the early 1870s, restored public credit and individual prosperity to the Boers of the Free State. The diamond fields offered a ready market for stock and other agricultural produce. Money flowed into the pockets of the farmers. Public credit was restored. "Bluebacks" recovered par value, and were called in and redeemed by the government. Valuable diamond mines were also discovered within the Free State, of which the one at Jagersfontein

Jagersfontein is a small town in the Free State province of South Africa.

Origin

The original farm on which the town stands was once the property of a Griqua Jacobus Jagers, hence the name Jagersfontein. He sold the farm to C.F. Visser in 1854 ...

was the richest. Capital from Kimberley

Kimberly or Kimberley may refer to:

Places and historical events

Australia

Queensland

* Kimberley, Queensland, a coastal locality in the Shire of Douglas

South Australia

* County of Kimberley, a cadastral unit in South Australia

Ta ...

and London was soon provided with which to work them.

Gold discovered

In 1934, new geophysical prospecting methods allowed for the discovery of deep gold-bearing reefs in the Orange Free State, which began theFree State Gold Rush

The Free State Gold Rush was a gold rush in Free State (province), Free State, South Africa. It began after the end of World War II, even though gold had been discovered in the area around the year 1934. It drove major development in the region ...

. From 1936 to 1947, approximately 190 miles of drilling had been accomplished by over 50 companies for prospecting the area, and in 1951, the first gold bar was produced from these fields. By 1981, gold mining was contributing 37.4% of the provinces GDP, and the city of Welkom

Welkom () is a city in the Free State (province), Free State province of South Africa, located about northeast of Bloemfontein, the provincial capital. Welkom is also known as Circle City, City Within A Garden, Mvela and Matjhabeng. The city' ...

and town of Riebeeckstad

Riebeeckstad is a suburb 5 km east of the city of Welkom located in the Lejweleputswa District Municipality of the Free State province of South Africa.

History

It is named after Jan van Riebeeck and was established as an upper-class subur ...

had been established to accommodate the labour forces.

Peaceful relations with neighbours

The relations between the British and the Orange Free State, after the question of the boundary was settled, remained perfectly amicable down to the outbreak of theSecond Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

in 1899. From 1870 onward the history of the state was one of quiet, steady progress. At the time of the first annexation of the Transvaal

Transvaal is a historical geographic term associated with land north of (''i.e.'', beyond) the Vaal River in South Africa. A number of states and administrative divisions have carried the name ''Transvaal''.

* South African Republic (1856–1902; ...

the Free State declined Lord Carnarvon's invitation to federate with the other South African communities. In 1880, when a rising of the Boers in the Transvaal was threatening, President Brand showed every desire to avert the conflict. He suggested that Sir Henry de Villiers, Chief Justice of Cape Colony

The Cape Colony (), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope. It existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with three ...

, should be sent into the Transvaal to endeavour to gauge the true state of affairs in that country. This suggestion was not acted upon, but when war broke out in the Transvaal, Brand declined to take any part in the struggle. In spite of the neutral attitude taken by their government a number of the Orange Free State Boers, living in the northern part of the country, went to the Transvaal and joined their brethren then in arms against the British. This fact was not allowed to influence the friendly relations between the Free State and Great Britain. In 1888 Sir Johannes Brand

Sir Johannes Henricus Brand, (popularly known as Sir Jan Brand and sometimes as Sir John Henry Brand or Jan Henrick Brand; 6 December 1823 – 14 July 1888) was a lawyer and politician who served as the fourth President (government title), ...

died.

During the period of Brand's presidency a great change, both political and economic, had come over South Africa. The renewal of the policy of British expansion had been answered by the formation of the

During the period of Brand's presidency a great change, both political and economic, had come over South Africa. The renewal of the policy of British expansion had been answered by the formation of the Afrikaner Bond

The Afrikaner Bond (Afrikaans and Dutch for "Afrikaner Union"; South African Dutch: Afrikander Bond) was founded as an anti-imperialist political party in 19th century southern Africa. While its origins were largely in the Orange Free State, i ...

, which represented the aspirations of the Afrikaner

Afrikaners () are a Southern African ethnic group descended from predominantly Dutch settlers who first arrived at the Cape of Good Hope in 1652.Entry: Cape Colony. ''Encyclopædia Britannica Volume 4 Part 2: Brain to Casting''. Encyclopæd ...

people, and had active branches in the Free State. This alteration in the political outlook was accompanied, and in part occasioned, by economic changes of great significance. The development of the diamond mines and of the gold and coal industries – of which Brand saw the beginning – had far-reaching consequences, bringing the Boer republics into contact with the new industrial era. The Orange Free Staters, under Brand's rule, had shown considerable ability to adapt their policy to meet the altered situation. In 1889 an agreement made between the Orange Free State and the Cape Colony government, whereby the latter was empowered to extend, at its own cost, its railway system to Bloemfontein. The Orange Free State retained the right to purchase this extension at cost, a right it exercised after the Jameson Raid

The Jameson Raid (Afrikaans: ''Jameson-inval'', , 29 December 1895 – 2 January 1896) was a botched raid against the South African Republic (commonly known as the Transvaal) carried out by British colonial administrator Leander Starr Jameson ...

.

Having accepted the assistance of the Cape government in constructing its railway, the state also in 1889 entered into a Customs Union Convention with them. The convention was the outcome of a conference held at Cape Town

Cape Town is the legislature, legislative capital city, capital of South Africa. It is the country's oldest city and the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. Cape Town is the country's List of municipalities in South Africa, second-largest ...

in 1888, at which delegates from Natal

NATAL or Natal may refer to:

Places

* Natal, Rio Grande do Norte, a city in Brazil

* Natal, South Africa (disambiguation), a region in South Africa

** Natalia Republic, a former country (1839–1843)

** Colony of Natal, a former British colony ( ...

, the Free State and the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony (), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope. It existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with three ...

attended. Natal at this time had not seen its way to entering the Customs union

A customs union is generally defined as a type of trade bloc which is composed of a free trade area with a common external tariff.GATTArticle 24 s. 8 (a)

Customs unions are established through trade pacts where the participant countries set u ...

, but did so at a later date.

Renewal of hostilities

In January 1889Francis William Reitz

Francis William Reitz Jr. (5 October 1844 – 27 March 1934) was a South African lawyer, politician, statesman, publicist, and poet who was a member of parliament of the Cape Colony, Chief Justice and fifth State President of the Orange Free ...

was elected president of the Orange Free State. Reitz had no sooner got into office than a meeting was arranged with Paul Kruger

Stephanus Johannes Paulus Kruger (; 10 October 1825 – 14 July 1904), better known as Paul Kruger, was a South African politician. He was one of the dominant political and military figures in 19th-century South Africa, and State Preside ...

, president of the South African Republic

The South African Republic (, abbreviated ZAR; ), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer republics, Boer republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when it was annexed into the British Empire as a result ...

, at which various terms were discussed and decided upon regarding an agreement dealing with the railways, terms of a treaty of amity and commerce, and what was called a political treaty. The political treaty referred in general terms to a federal union between the South African Republic

The South African Republic (, abbreviated ZAR; ), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer republics, Boer republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when it was annexed into the British Empire as a result ...

and the Orange Free State, and bound each of them to help the other, whenever the independence of either should be assailed or threatened from without, unless the state so called upon for assistance should be able to show the injustice of the cause of quarrel in which the other state had engaged. While thus committed to an alliance with its northern neighbour no change was made in internal administration. The Free State, in fact, from its geographical position reaped the benefits without incurring the anxieties consequent on the settlement of a large Uitlander

An uitlander, Afrikaans for "foreigner" (), was a foreign (mainly British) migrant worker during the Witwatersrand Gold Rush in the independent Transvaal Republic following the discovery of gold in 1886. The limited rights granted to this group ...

population on the Witwatersrand

The Witwatersrand (, ; ; locally the Rand or, less commonly, the Reef) is a , north-facing scarp in South Africa. It consists of a hard, erosion-resistant quartzite metamorphic rock, over which several north-flowing rivers form waterfalls, w ...

. The state, however, became increasingly identified with the reactionary party in the South African Republic

The South African Republic (, abbreviated ZAR; ), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer republics, Boer republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when it was annexed into the British Empire as a result ...

.

In 1895 the Volksraad passed a resolution, in which they declared their readiness to entertain a proposition from the South African Republic

The South African Republic (, abbreviated ZAR; ), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer republics, Boer republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when it was annexed into the British Empire as a result ...

in favour of some form of federal union. In the same year Ritz retired from the presidency of the Orange Free State. The 1896 presidential election to succeed him was won by M. T. Steyn, a judge of the High Court, who took office in February 1896. In 1896 President Steyn visited Pretoria

Pretoria ( ; ) is the Capital of South Africa, administrative capital of South Africa, serving as the seat of the Executive (government), executive branch of government, and as the host to all foreign embassies to the country.

Pretoria strad ...

, where he received an ovation as the probable future president of the two Republics. A further offensive and defensive alliance between the two Republics was then entered into, under which the Orange Free State took up arms on the outbreak of hostilities between the British and the South African Republic

The South African Republic (, abbreviated ZAR; ), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer republics, Boer republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when it was annexed into the British Empire as a result ...

in October 1899.

In 1897 President Kruger, bent on still further cementing the union with the Orange Free State, had visited Bloemfontein

Bloemfontein ( ; ), also known as Bloem, is the capital and the largest city of the Free State (province), Free State province in South Africa. It is often, and has been traditionally, referred to as the country's "judicial capital", alongsi ...

. It was on this occasion that Kruger, referring to the London Convention, spoke of Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

as a ''kwaaje Vrouw'' (angry woman), an expression which caused a good deal of offence in England at the time, but which, in the phraseology of the Boers, was not meant by President Kruger

Stephanus Johannes Paulus Kruger (; 10 October 1825 – 14 July 1904), better known as Paul Kruger, was a South African politician. He was one of the dominant political and military figures in 19th-century South Africa, and State Presiden ...

as insulting.

In December 1897 the Free State revised its constitution in reference to the franchise law, and the period of residence necessary to obtain naturalization was reduced from five to three years. The oath of allegiance to the state was alone required, and no renunciation of nationality was insisted upon. In 1898 the Free State also acquiesced in the new convention arranged with regard to the Customs Union between the

In December 1897 the Free State revised its constitution in reference to the franchise law, and the period of residence necessary to obtain naturalization was reduced from five to three years. The oath of allegiance to the state was alone required, and no renunciation of nationality was insisted upon. In 1898 the Free State also acquiesced in the new convention arranged with regard to the Customs Union between the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony (), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope. It existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with three ...

, Natal

NATAL or Natal may refer to:

Places

* Natal, Rio Grande do Norte, a city in Brazil

* Natal, South Africa (disambiguation), a region in South Africa

** Natalia Republic, a former country (1839–1843)

** Colony of Natal, a former British colony ( ...

, Basutoland

Basutoland was a British Crown colony that existed from 1884 to 1966 in present-day Lesotho, bordered with the Cape Colony, Natal Colony and Orange River Colony until 1910 and completely surrounded by South Africa from 1910. Though the Basot ...

and the Bechuanaland Protectorate

The Bechuanaland Protectorate () was a British protectorate, protectorate established on 31 March 1885 in Southern Africa by the United Kingdom. It became the Botswana, Republic of Botswana on 30 September 1966.

History

Scottish missionary ...

. But events were moving rapidly in the Transvaal, and matters had proceeded too far for the Free State to turn back. In May 1899 President Steyn suggested the conference at Bloemfontein between President Kruger and Sir Alfred Milner, but this act was too late. The Free Staters were practically bound to the South African Republic

The South African Republic (, abbreviated ZAR; ), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer republics, Boer republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when it was annexed into the British Empire as a result ...

, under the offensive and defensive alliance, in case hostilities arose with Great Britain.

The Orange Free State began to expel British subjects in 1899, and the first act of the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

was committed by Orange Free State Boers, who, on 11 October 1899, seized a train upon the border belonging to Natal. For President Steyn and the Free State of 1899, neutrality was impossible. A resolution was passed by the Volksraad on 27 September declaring that the state would observe its obligations to the Transvaal whatever might happen.

After the surrender of Piet Cronjé

Pieter Arnoldus "Piet" Cronjé (4 October 1836 – 4 February 1911) was a South African Boer general during the Anglo-Boer Wars of 1880–1881 and 1899–1902.

Biography

Born in the Cape Colony but raised in the South African Republic, Cronj ...

in the Battle of Paardeberg

The Battle of Paardeberg or Perdeberg ("Horse Mountain", 18–27 February 1900) was a major battle during the Second Anglo-Boer War. It was fought near ''Paardeberg Ford (crossing), Drift'' on the banks of the Modder River in the Orange Free St ...

on 27 February 1900, Bloemfontein

Bloemfontein ( ; ), also known as Bloem, is the capital and the largest city of the Free State (province), Free State province in South Africa. It is often, and has been traditionally, referred to as the country's "judicial capital", alongsi ...

was occupied by the British troops under Lord Roberts from 13 March onward, and on 28 May a proclamation was issued annexing the Free State to the British dominions under the title of Orange River Colony

The Orange River Colony was the British colony created after Britain first occupied (1900) and then annexed (1902) the independent Orange Free State in the Second Boer War. The colony ceased to exist in 1910, when it was absorbed into the Unio ...

. For nearly two years longer the burghers kept the field under Christiaan de Wet

Christiaan Rudolf de Wet (7 October 1854 – 3 February 1922) was a Boer general, rebel leader and politician.

Life

Born on the Leeuwkop farm, in the district of Smithfield in the Boer Republic of the Orange Free State, he later resided at ...

and other leaders, but by the articles of peace signed on 31 May 1902 British sovereignty was acknowledged.

Politics

The 1854 constitution outlined that the unicameral legislature,Volksraad The Volksraad was a people's assembly or legislature in Dutch or Afrikaans speaking government.