Tommy Lyttle on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Tommy "Tucker" Lyttle (c. 1939 – 18 October 1995), was a high-ranking

"Sordid Death of Top Gun"

''The Guardian''; 1 October 2000. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

Lyttle was born in

Lyttle was born in

''The Independent'', 30 March 1996. Retrieved 29 March 2011. In 1969, the religious-political conflict known as "

"Children of the Revolution: a book from the heart of the Troubles"

BBC, 23 July 2011. Retrieved 18 May 2012. Kevin Myers, who was personally acquainted with Lyttle in Belfast, called him "a violent man" but admitted to having liked him. Kevin Myers. "Ireland: the dark before the dawn", ''The Sunday Times'', 29 October 2006. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

Ulster loyalist

Ulster loyalism is a strand of Unionism in Ireland, Ulster unionism associated with working class Ulster Protestants in Northern Ireland. Like other unionists, loyalists support the continued existence of Northern Ireland (and formerly all of I ...

during the period of religious-political conflict in Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ; ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, part of the United Kingdom in the north-east of the island of Ireland. It has been #Descriptions, variously described as a country, province or region. Northern Ireland shares Repub ...

known as "the Troubles

The Troubles () were an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted for about 30 years from the late 1960s to 1998. Also known internationally as the Northern Ireland conflict, it began in the late 1960s and is usually deemed t ...

". A member of the Ulster Defence Association

The Ulster Defence Association (UDA) is an Ulster loyalist paramilitary group in Northern Ireland. It was formed in September 1971 as an umbrella group for various loyalist groups and undertook an armed campaign of almost 24 years as one of t ...

(UDA) – the largest loyalist paramilitary organisation in Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ; ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, part of the United Kingdom in the north-east of the island of Ireland. It has been #Descriptions, variously described as a country, province or region. Northern Ireland shares Repub ...

– he first held the rank of lieutenant colonel and later was made a brigadier. He served as the UDA's spokesman as well as the leader of the organisation's West Belfast Brigade from 1975 until his arrest and imprisonment in 1990. According to journalists Henry McDonald and Brian Rowan, and the Pat Finucane Centre, he became a Royal Ulster Constabulary

The Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) was the police force in Northern Ireland from 1922 to 2001. It was founded on 1 June 1922 as a successor to the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) Richard Doherty, ''The Thin Green Line – The History of the ...

(RUC) Special Branch

Special Branch is a label customarily used to identify units responsible for matters of national security and Intelligence (information gathering), intelligence in Policing in the United Kingdom, British, Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth, ...

informer.Henry McDonald"Sordid Death of Top Gun"

''The Guardian''; 1 October 2000. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

Ulster Defence Association

Lyttle was born in

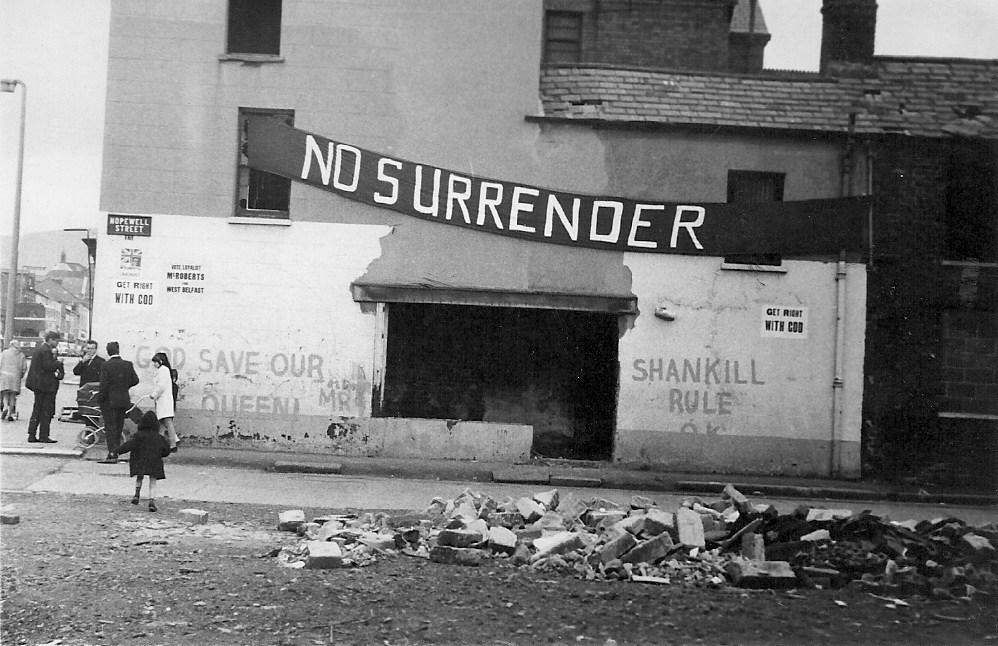

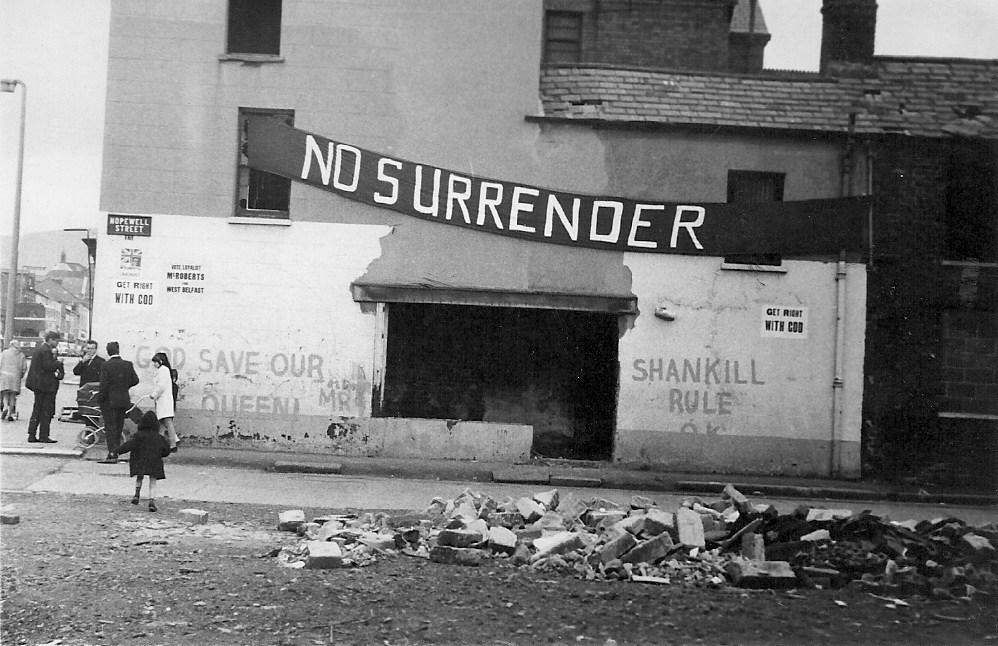

Lyttle was born in Belfast

Belfast (, , , ; from ) is the capital city and principal port of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan and connected to the open sea through Belfast Lough and the North Channel (Great Britain and Ireland), North Channel ...

and grew up in the loyalist Shankill Road

The Shankill Road () is one of the main roads leading through West Belfast, in Northern Ireland. It runs through the working-class, predominantly loyalist, area known as the Shankill.

The road stretches westwards for about from central Belfast ...

area in a Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

family as one of five children. In the late 1960s, he worked as a machinist in Mackie's Foundry in the Springfield Road. He later became a bookmaker

A bookmaker, bookie, or turf accountant is an organization or a person that accepts and pays out bets on sporting and other events at agreed-upon odds

In probability theory, odds provide a measure of the probability of a particular outco ...

. At the age of 18, he married Elizabeth Baird, by whom he had three sons and two daughters."In the Name of My Father"''The Independent'', 30 March 1996. Retrieved 29 March 2011. In 1969, the religious-political conflict known as "

The Troubles

The Troubles () were an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted for about 30 years from the late 1960s to 1998. Also known internationally as the Northern Ireland conflict, it began in the late 1960s and is usually deemed t ...

" broke out; two years later in 1971, he became a founding member of the legal loyalist paramilitary organisation, the Ulster Defence Association.The Ulster Defence Association remained a legal organisation from its founding in September 1971 until 10 August 1992 when it was proscribed by the British Government. According to his daughter, Linda, he joined the UDA after a Provisional Irish Republican Army

The Provisional Irish Republican Army (Provisional IRA), officially known as the Irish Republican Army (IRA; ) and informally known as the Provos, was an Irish republican paramilitary force that sought to end British rule in Northern Ireland ...

(PIRA) bomb exploded at the Balmoral furniture showroom in the Shankill Road in December 1971, killing four people, including two babies. Lyttle's wife and two daughters had been close to the scene of the explosion but were unhurt.

In 1972, he was a lieutenant colonel in the UDA's "C" Company, 2nd Battalion Shankill Road; in 1975 he rose to the rank of brigadier, having command of the West Belfast Brigade. He had taken over the brigade from Charles Harding Smith, the former leader of the UDA, and its first commander following the organisation's formation. Although Andy Tyrie

Andrew Tyrie (5 February 1940 – 16 May 2025) was a Northern Irish Ulster loyalist, loyalist paramilitary leader who served as commander of the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) during much of its early history. He took the place of Tommy Herr ...

was the UDA's overall commander (from 1973 to 1988), brigadiers such as Lyttle enjoyed a large degree of autonomy and regarded the areas under their control as "their personal fiefdoms".Taylor, Peter (1999). ''Loyalists''. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. pp. 199, 209; . He was a member of the UDA's Inner Council and served as the UDA's spokesman. His youngest son, Thomas "Tosh" Lyttle also joined the UDA.

Rise to West Belfast Brigadier

It was alleged by Irish journalist Kevin Myers that Lyttle was with fellow UDA member Davy Payne when two Catholics, Patrick O'Neill and Rosemary McCartney, were abducted at a UDA roadblock and brought to one of the UDA's notorious "romper rooms" to be interrogated and tortured, with Payne having presided over the "grilling" and the subsequent double killing on 21 July 1972, the day the IRA had exploded 22 bombs in various areas of Belfast resulting in the deaths of nine people including UDA member William Irvine and two Protestant teenagers, William Crothers and Stephen Parker. He was anIndependent Unionist

Independent Unionist is a label sometimes used by candidates in British elections to indicate their support for British unionism. It is most popularly associated with candidates in elections for the Parliament of Northern Ireland. Such candi ...

candidate for North Belfast in the 1973 Northern Ireland Assembly elections. He was not elected, however, having only polled a total of 560 votes. Along with Tommy Herron and Billy Hull he was one of three leading UDA figures to stand for election in Belfast, with all three failing to win a seat. He took his loss in stride with the statement: "It's not such a bad result for someone whose day job is a bookie".

During the Ulster Workers' Council Strike

The Ulster Workers' Council (UWC) strike was a general strike that took place in Northern Ireland between 15 May and 28 May 1974, during "the Troubles". The strike was called by Unionism in Ireland, unionists who were against the Sunningdale Ag ...

of May 1974 Lyttle was, along with UDA leader Andy Tyrie and Ken Gibson of the Ulster Volunteer Force

The Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) is an Ulster loyalism, Ulster loyalist paramilitary group based in Northern Ireland. Formed in 1965, it first emerged in 1966. Its first leader was Gusty Spence, a former Royal Ulster Rifles soldier from North ...

(UVF), one of three loyalist paramilitaries chosen to accompany the three leaders of the main unionist political parties, Harry West

Henry William West (27 March 1917 – 5 February 2004) was a Northern Irish unionist politician who served as leader of the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) from 1974 until 1979.

Career to Stormont

West was born in County Fermanagh and educated at ...

, Ian Paisley

Ian Richard Kyle Paisley, Baron Bannside, (6 April 1926 – 12 September 2014) was a loyalist politician and Protestant religious leader from Northern Ireland who served as leader of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) from 1971 to 2008 and ...

, and Ernest Baird, to a meeting with Stanley Orme, the deputy to the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland

The secretary of state for Northern Ireland (; ), also referred to as Northern Ireland Secretary or SoSNI, is a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, with overall responsibility for the Northern Ireland Office. The offi ...

Merlyn Rees

Merlyn Merlyn-Rees, Baron Merlyn-Rees, (né Merlyn Rees; 18 December 1920 – 5 January 2006) was a British Labour Party politician and Member of Parliament from 1963 until 1992. He served as Secretary of State for Northern Ireland (1974–1 ...

, in which the government representative attempted unsuccessfully to have the strike terminated early.

Together with Tyrie, Vanguard

The vanguard (sometimes abbreviated to van and also called the advance guard) is the leading part of an advancing military formation. It has a number of functions, including seeking out the enemy and securing ground in advance of the main force.

...

Assemblyman Glenn Barr, his ally Andy Robinson

Richard Andrew Robinson Order of the British Empire, OBE (born 3 April 1964) is an English rugby union coach and retired player. He was the director of rugby at Bristol Bears, Bristol until November 2016. He is the former head coach of Scotland ...

and Newtownabbey

Newtownabbey ( ) is a large settlement north of Belfast city centre in County Antrim, Northern Ireland. It is separated from the rest of the city by Cavehill and Fortwilliam golf course, but it still forms part of the Belfast metropolitan area ...

-based Harry Chicken, Lyttle travelled to Libya

Libya, officially the State of Libya, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya border, the east, Sudan to Libya–Sudan border, the southeast, Chad to Chad–L ...

where he met Colonel Muammar Gaddafi

Muammar Muhammad Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi (20 October 2011) was a Libyan military officer, revolutionary, politician and political theorist who ruled Libya from 1969 until Killing of Muammar Gaddafi, his assassination by Libyan Anti-Gaddafi ...

about obtaining weapons and money for the loyalist cause. When Lyttle returned from the trip, which was largely unsuccessful, he was caught up in a loyalist feud

Sporadic feuds erupted almost routinely between Northern Ireland's various loyalist paramilitary groups after the ethno-political conflict known as the Troubles began in 1969. The feuds have frequently involved conflicts between and within the ...

between Tyrie and Charles Harding Smith for overall control of the UDA. Lyttle was with Harding Smith when the latter was shot and wounded by a sniper in January 1975. Following the attack Tyrie asserted his control and, with the help of Lyttle and fellow Shankill commanders John McClatchey and Tommy Boyd, soon regained control of the pivotal Shankill and neighbouring Woodvale areas. Harding Smith survived another shooting later that year before leaving Northern Ireland for good. Lyttle was then appointed West Belfast Brigadier in his stead.

With the feud ended and firmly established as a loyal supporter of Tyrie, Lyttle was sent by Tyrie to the United States to solicit support and funding from interested groups. In 1977 he helped form a think tank with UDA Commander Andy Tyrie and South Belfast brigadier John McMichael

John McMichael (9 January 1948 – 22 December 1987) was a Northern Irish loyalist who rose to become the most prominent and charismatic figure within the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) as the Deputy Commander and leader of its South Belfa ...

; this was called the New Ulster Political Research Group

The Ulster Political Research Group is an advisory body connected to the Ulster Defence Association (UDA), providing advice to them on political matters. The group was permanently founded in January 2002, and is largely a successor to the Ulster ...

. Along with Tyrie, McMichael, Glenn Barr and Harry Chicken, Lyttle was involved in the production of the group's 1979 policy document ''Beyond the Religious Divide'' in which the UDA advanced a policy of negotiated independence for Northern Ireland.

Stevens Enquiry

In January 1990, Lyttle, along with his son, "Tosh", was arrested by the John Stevens Enquiry team after his fingerprints were found on a stolen classified document which was a security forces list of suspected republicans, likely to be used by loyalist paramilitaries for targeting people to be assassinated by hit squads. He was brought before Belfast's Crumlin Road Court where he was convicted of receiving and passing on classified security force intelligence files and intimidating potential witnesses. Although sentenced to seven years imprisonment, he was released in 1994 on remission. Journalists Henry McDonald and Brian Rowan, in company with the Pat Finucane Centre, later revealed that Lyttle was an informer working for the RUC's Special Branch with the codename "Rodney Stewart". A former officer from the Force Research Unit (the covert military intelligence agent-handling unit based in Northern Ireland) using the pseudonym " Martin Ingram" suggested that Lyttle ordered Nelson, who was recruited by the FRU to infiltrate the UDA's intelligence structure, to compile targeting information on a Catholic solicitor Pat Finucane from a republican family prior to his killing in 1989. "Ingram" stated he knew with "iron cast certainty" that Lyttle was working as an informer for Special Branch at the time of the Finucane killing. According toAndy Tyrie

Andrew Tyrie (5 February 1940 – 16 May 2025) was a Northern Irish Ulster loyalist, loyalist paramilitary leader who served as commander of the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) during much of its early history. He took the place of Tommy Herr ...

, Lyttle was reluctant to become personally involved in the Finucane killing, as he feared that his rank of brigadier would make him a likely target for the inevitable IRA retaliation.

Stobie was later arrested and charged with Finucane's killing, although he was not convicted. UDA member Ken Barrett, who was also a Special Branch informer, eventually pleaded guilty to the killing in September 2004. Shortly before Lyttle's death in October 1995, BBC journalist John Ware interviewed him. Lyttle maintained that two RUC officers had originally proposed the idea of killing Finucane. Lyttle allegedly claimed to another journalist that his Special Branch handler suggested "Why don't you whack Finucane?"

Two years prior to Finucane's assassination, Lyttle reportedly had asked Nelson to obtain details on top IRA figures. When the name Frederick Scappaticci came up, Nelson's FRU handlers became alarmed as Scappaticci—allegedly known as " Stakeknife"—was one of their most important agents, having infiltrated the Provisional IRA's Internal Security Unit

The Internal Security Unit (ISU) was the counter-intelligence and interrogation unit of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA). This unit was often referred to as the Nutting Squad, in reference to the fact that many of the informers uncove ...

or "Nutting Squad" as it was commonly referred to. A substitute was eventually found in the person of Francisco Notarantonio, a retired IRA man of Italian parentage who had been interned previously. On 9 October 1987, Lyttle sent out a UDA hit squad, headed by Sam McCrory using the cover name "Ulster Freedom Fighters

The Ulster Defence Association (UDA) is an Ulster loyalism, Ulster loyalist paramilitary group in Northern Ireland. It was formed in September 1971 as an umbrella group for various loyalist groups and Timeline of Ulster Defence Association act ...

"The "Ulster Freedom Fighters" was the cover name used by the UDA when they carried out killings and attacks to avoid proscription by the British Government as was the case with their rival loyalist paramilitary group the Ulster Volunteer Force

The Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) is an Ulster loyalism, Ulster loyalist paramilitary group based in Northern Ireland. Formed in 1965, it first emerged in 1966. Its first leader was Gusty Spence, a former Royal Ulster Rifles soldier from North ...

(UVF) to Notarantonio's home where they shot him to death in his bedroom. Allegedly a party was held afterwards in Lyttle's Sydney Street West home to celebrate the killing. Lyttle threw a similar party following the assassination of Finucane.

The possibility of conspiracy became public through Lyttle himself, following the shooting of Loughlin Maginn on 25 August 1989. Media coverage showed Maginn as the innocent victim of a sectarian attack but Lyttle personally contacted members of the press to inform them that the UDA had good reasons for killing Maginn, whose name was on the list.H. McDonald & J. Cusack, ''UDA – Inside the Heart of Loyalist Terror'', Dublin, Penguin Ireland, 2004, pp. 145–49 To back up his claims, he sent a copy of the list he received to a journalist. The uproar that followed the revelation that a senior UDA member was in possession of government documents led to Royal Ulster Constabulary

The Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) was the police force in Northern Ireland from 1922 to 2001. It was founded on 1 June 1922 as a successor to the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) Richard Doherty, ''The Thin Green Line – The History of the ...

Chief Constable Hugh Annesley appointing Stevens, an officer in Cambridgeshire Constabulary, to investigate the claims.

John McMichael killing

John McMichael was blown up by a booby-trap car bomb outside hisLisburn

Lisburn ( ; ) is a city in Northern Ireland. It is southwest of Belfast city centre, on the River Lagan, which forms the boundary between County Antrim and County Down. First laid out in the 17th century by English and Welsh settlers, with t ...

home on 22 December 1987. Although the IRA claimed responsibility for the attack, there were suggestions that members of the UDA helped set up the killing by passing on information to the IRA about McMichael to facilitate the assassination. Lyttle put the blame on his long-time rival James Pratt Craig, the UDA's notorious "fundraiser", who had been under investigation by McMichael for his racketeering activities. There was considerable animosity between the two UDA men, as Craig had allegedly impregnated one of Lyttle's daughters.

Removal from leadership

Following the televisedMilltown Cemetery attack

The Milltown Cemetery attack (also known as the Milltown Cemetery killings or Milltown massacre) took place on 16 March 1988 at Milltown Cemetery in Belfast, Northern Ireland. During the large funeral of three Provisional Irish Republican Arm ...

by loyalist Michael Stone in March 1988, Lyttle released a statement claiming that Stone had operated alone without sanction from the UDA's Inner Council as he felt that such commando-style attacks would inevitably bring retaliation from republican paramilitaries, making open warfare between the two communities a real possibility. However, Stone's actions—in which three republicans were shot dead and more than 60 wounded—impressed many young loyalists who rushed to join the UDA. This change in membership profile was to have a profound effect on the make-up of the UDA leadership.

With McMichael dead, Tyrie having resigned in March 1988 (following an attempt on his life) and Craig being assassinated by UFF gunmen in October 1988, Lyttle was one of the few veterans to remain in power and his incarceration during the Stevens Enquiry was to prove the catalyst for his removal from command, with Tommy Irvine succeeding him as West Belfast brigadier. By 1989–90, information regarding UDA operations was being deliberately withheld from Lyttle "because he was thought to be not reliable". His close personal relationship with Ulster Volunteer Force

The Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) is an Ulster loyalism, Ulster loyalist paramilitary group based in Northern Ireland. Formed in 1965, it first emerged in 1966. Its first leader was Gusty Spence, a former Royal Ulster Rifles soldier from North ...

(UVF) chief John "Bunter" Graham was also a source of animosity as the younger members tended to view the UVF as a rival organisation despite their shared loyalism.David Lister & Hugh Jordan, ''Mad Dog: The Rise and Fall of Johnny Adair and 'C' Company'', Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing, 2004, , p. 81

Held in Crumlin Road Gaol from July 1991, word was sent into the prison by a new group of "Young Turks"—emerging leaders from the Shankill—that Lyttle was to be ostracised by the other UDA inmates. As a result of this edict Lyttle was moved into secure isolation on a wing of the prison usually reserved for prisoners under high risk of attack from other inmates, such as sex offenders; an area described by one of the new leaders, Jim Spence, as "the wing with the ball-roots local slang term of abuse.H. McDonald & J. Cusack, ''UDA – Inside the Heart of Loyalist Terror'', Dublin, Penguin Ireland, 2004, pp. 159–61. As the 1990s progressed, Lyttle had little involvement in the UDA leadership on the Shankill Road, which had passed to Johnny Adair

John Adair (born 27 October 1963), better known as Johnny Adair or Mad Dog Adair, is a Northern Irish loyalist and the former leader of the "C Company", 2nd Battalion Shankill Road, West Belfast Brigade of the Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF). Th ...

and other young, ambitious militants such as Stephen McKeag who wanted a freer hand in dealing with Catholics than that afforded by Lyttle with the latter's alleged links to the security forces".

Death and legacy

Lyttle was released in 1994 on remission after having served three years of his seven-year sentence. Immediately after his release he was summoned to appear before the UDA Inner Council and reportedly admitted to working for Special Branch. He later claimed he avoided being executed by convincing the leadership that "the Branch had helped him. He hadn't helped them". He left his home in the Shankill and retired toDonaghadee

Donaghadee ( , ) is a small town in County Down, Northern Ireland. It lies on the northeast coast of the Ards Peninsula, about east of Belfast and about six miles (10 km) south east of Bangor, County Down, Bangor. It is in the Civil paris ...

, County Down

County Down () is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland, one of the nine counties of Ulster and one of the traditional thirty-two counties of Ireland. It covers an area of and has a population of 552,261. It borders County Antrim to the ...

, where he died of a heart attack on 18 October 1995 as he was playing snooker

Snooker (pronounced , ) is a cue sport played on a rectangular Billiard table#Snooker and English billiards tables, billiards table covered with a green cloth called baize, with six Billiard table#Pockets 2, pockets: one at each corner and ...

in a local pub. He was 56 years old.

His second son, John, a journalist who writes for ''The Independent

''The Independent'' is a British online newspaper. It was established in 1986 as a national morning printed paper. Nicknamed the ''Indy'', it began as a broadsheet and changed to tabloid format in 2003. The last printed edition was publis ...

'', has described his father as a "hard man" who liked to read ''James Bond

The ''James Bond'' franchise focuses on James Bond (literary character), the titular character, a fictional Secret Intelligence Service, British Secret Service agent created in 1953 by writer Ian Fleming, who featured him in twelve novels ...

'' novels, and watch western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

and gangster films. He recounted a scene from his childhood when he had gone downstairs to get a glass of water and discovered a bloodied man tied to a chair being beaten by his father. Tommy Lyttle momentarily stopped hitting his victim to order one of his henchmen to fetch his son a glass of water.Claire Brennan"Children of the Revolution: a book from the heart of the Troubles"

BBC, 23 July 2011. Retrieved 18 May 2012. Kevin Myers, who was personally acquainted with Lyttle in Belfast, called him "a violent man" but admitted to having liked him. Kevin Myers. "Ireland: the dark before the dawn", ''The Sunday Times'', 29 October 2006. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

Notes

References

Bibliography

* Taylor, Peter (1999). ''Loyalists''. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.; * McDonald, Henry & Cusack, Jim (2004). ''UDA – Inside the Heart of Loyalist Terror''. Dublin: Penguin Ireland * Wood, Ian S. (2006). ''Crimes of Loyality: a History of the UDA''. Edinburgh University Press {{DEFAULTSORT:Lyttle, Tommy 1930s births Date of birth missing 1995 deaths Ulster Defence Association members UDA C Company members Paramilitaries from Belfast Loyalists imprisoned during the Northern Ireland conflict