Timeline Of Zoology on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

This is a chronologically organized listing of notable

*3500 BC.

*3500 BC.  *500 BC.

*500 BC.  *323 BC.

*323 BC.  *77.

*77.

*1244–1248. Frederick II von Hohenstaufen (Holy Roman Emperor) (1194–1250) wrote ' (''The Art of Hunting with Birds'') as a practical guide to

*1244–1248. Frederick II von Hohenstaufen (Holy Roman Emperor) (1194–1250) wrote ' (''The Art of Hunting with Birds'') as a practical guide to  *1244. Vincentius Bellovacensis ( Vincent of Beauvais) (1190–1264) wrote ' (1244–1254), a major encyclopedia. This work comprises three huge volumes, of 80 books and 9,885 chapters.

*1254–1323.

*1244. Vincentius Bellovacensis ( Vincent of Beauvais) (1190–1264) wrote ' (1244–1254), a major encyclopedia. This work comprises three huge volumes, of 80 books and 9,885 chapters.

*1254–1323.  *1492.

*1492.

*1551–1555. Pierre Belon (French, 1517–1564) wrote ' (1551) and ' (1555). This latter work included 110 animal species and offered many new observations and corrections to Herodotus. ' (1555) was his picture book, with improved animal classification and accurate anatomical drawings. In this he published a man's and a bird's skeleton side by side to show the resemblance. He discovered an armadillo shell in a market in

*1551–1555. Pierre Belon (French, 1517–1564) wrote ' (1551) and ' (1555). This latter work included 110 animal species and offered many new observations and corrections to Herodotus. ' (1555) was his picture book, with improved animal classification and accurate anatomical drawings. In this he published a man's and a bird's skeleton side by side to show the resemblance. He discovered an armadillo shell in a market in

*1648. Georg Marcgrave (1610–1644) was a German astronomer working for Johann Moritz, Count Maurice of Nassau, in the Dutch colony set up in northeastern

*1648. Georg Marcgrave (1610–1644) was a German astronomer working for Johann Moritz, Count Maurice of Nassau, in the Dutch colony set up in northeastern

*1705.

*1705.  *1749–1804.

*1749–1804.  *1769. Edward Bancroft (English) wrote ''An Essay on the Natural History of Guyana in South America'' (1769) and advanced the theory that flies transmit disease.

*1771.

*1769. Edward Bancroft (English) wrote ''An Essay on the Natural History of Guyana in South America'' (1769) and advanced the theory that flies transmit disease.

*1771.  *1783–1792. Alexandre Rodrigues Ferreira (Brazilian) wrote '. His specimens were taken by Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, Saint-Hilaire from Lisbon to the National Museum of Natural History, France, Paris Museum during the Napoleonic invasion of Portugal.

*1784. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (German) wrote ' (1795) that promoted the idea of archetypes to which animals should be compared.

*1784. Thomas Jefferson (American) wrote ''Notes on the State of Virginia'' (1784) that refuted some of Buffon's mistakes about New World fauna. As U.S. president, he dispatched the Lewis and Clark Expedition to the American West (1804).

*1788. The First Fleet inaugurates British settlement of Australia. Knowledge of Australia's unique zoology, including marsupials and the platypus, would revolutionize Western zoology.

*1789? Guillaume Antoine Olivier (French, 1756–1814) wrote ', or ' (1789).

*1789. George Shaw (biologist), George Shaw & Frederick Polydore Nodder published ''The Naturalist's Miscellany: or coloured figures of natural objects drawn and described immediately from nature'' (1789–1813) in 24 volumes with hundreds of color plates.

*1792. François Huber made original observations on honeybees. In his ' (1792) he noted that the first eggs laid by queen bees develop into Drone (bee), drones if her nuptial flight had been delayed and that her last eggs would also give rise to drones. He also noted that rare worker eggs develop into drones. This anticipated by over 50 years the discovery by Jan Dzierżon that drones come from unfertilized eggs and queen and worker bees come from fertilized eggs.

*1793. The National Museum of Natural History, France is founded in Paris. It became a major center of zoological research in the early nineteenth century.

*1793. Lazaro Spallanzani (Italian, 1729–1799) conducted experiments on the orientation of bats and owls in the dark.

*1793. Christian Konrad Sprengel (1750–1816) wrote ' (1793) that was a major work on insect pollination of flowers, previously discovered in 1721 by Philip Miller (1694–1771), the head gardener at Chelsea and author of the famous ''Gardener's Dictionary'' (1731–1804).

*1783–1792. Alexandre Rodrigues Ferreira (Brazilian) wrote '. His specimens were taken by Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, Saint-Hilaire from Lisbon to the National Museum of Natural History, France, Paris Museum during the Napoleonic invasion of Portugal.

*1784. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (German) wrote ' (1795) that promoted the idea of archetypes to which animals should be compared.

*1784. Thomas Jefferson (American) wrote ''Notes on the State of Virginia'' (1784) that refuted some of Buffon's mistakes about New World fauna. As U.S. president, he dispatched the Lewis and Clark Expedition to the American West (1804).

*1788. The First Fleet inaugurates British settlement of Australia. Knowledge of Australia's unique zoology, including marsupials and the platypus, would revolutionize Western zoology.

*1789? Guillaume Antoine Olivier (French, 1756–1814) wrote ', or ' (1789).

*1789. George Shaw (biologist), George Shaw & Frederick Polydore Nodder published ''The Naturalist's Miscellany: or coloured figures of natural objects drawn and described immediately from nature'' (1789–1813) in 24 volumes with hundreds of color plates.

*1792. François Huber made original observations on honeybees. In his ' (1792) he noted that the first eggs laid by queen bees develop into Drone (bee), drones if her nuptial flight had been delayed and that her last eggs would also give rise to drones. He also noted that rare worker eggs develop into drones. This anticipated by over 50 years the discovery by Jan Dzierżon that drones come from unfertilized eggs and queen and worker bees come from fertilized eggs.

*1793. The National Museum of Natural History, France is founded in Paris. It became a major center of zoological research in the early nineteenth century.

*1793. Lazaro Spallanzani (Italian, 1729–1799) conducted experiments on the orientation of bats and owls in the dark.

*1793. Christian Konrad Sprengel (1750–1816) wrote ' (1793) that was a major work on insect pollination of flowers, previously discovered in 1721 by Philip Miller (1694–1771), the head gardener at Chelsea and author of the famous ''Gardener's Dictionary'' (1731–1804).

*1794. Erasmus Darwin (English, grandfather of Charles Darwin) wrote ''Zoönomia, or the Laws of Organic Life'' (1794) in which he advanced the idea that environmental influences could transform species.

*1796–1829. Pierre André Latreille (French, 1762–1833) sought to provide a "natural" system for the classification of animals, in his many monographs on invertebrates. ' (1811) was devoted to insects collected by Alexander Humboldt, Humboldt and Aime Bonpland, Bonpland.

*1797-1804. Publication of A History of British Birds by Thomas Bewick and Ralph Beilby in two volumes.

*1798. Publication of Thomas Robert Malthus's An Essay on the Principle of Population, a book important to both Darwin and Wallace.

*1799. George Shaw (biologist), George Shaw (English) provided the first description of the duck-billed platypus. Everard Home (1802) provided the first complete description.

*1799–1803. Alexander von Humboldt (German, 1769–1859) and Aimé Bonpland, Aimé Jacques Alexandre Goujaud Bonpland (French) arrived in Venezuela in 1799. Humboldt's ''Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of America during the years 1799–1804'' and ''Kosmos'' were influential in his time.

*1799. Georges Cuvier (French, 1769–1832) established comparative anatomy as a field. He also founded the science of paleontology. He wrote ' (1801–1805), ' (1816), ' (1812–1813). He believed in the fixity of species and the Genesis flood narrative, Biblical Flood. His early ' (1798) was influential, but it did not include Cuvier's major contributions to animal classification.

*1799. American hunters killed the last

*1794. Erasmus Darwin (English, grandfather of Charles Darwin) wrote ''Zoönomia, or the Laws of Organic Life'' (1794) in which he advanced the idea that environmental influences could transform species.

*1796–1829. Pierre André Latreille (French, 1762–1833) sought to provide a "natural" system for the classification of animals, in his many monographs on invertebrates. ' (1811) was devoted to insects collected by Alexander Humboldt, Humboldt and Aime Bonpland, Bonpland.

*1797-1804. Publication of A History of British Birds by Thomas Bewick and Ralph Beilby in two volumes.

*1798. Publication of Thomas Robert Malthus's An Essay on the Principle of Population, a book important to both Darwin and Wallace.

*1799. George Shaw (biologist), George Shaw (English) provided the first description of the duck-billed platypus. Everard Home (1802) provided the first complete description.

*1799–1803. Alexander von Humboldt (German, 1769–1859) and Aimé Bonpland, Aimé Jacques Alexandre Goujaud Bonpland (French) arrived in Venezuela in 1799. Humboldt's ''Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of America during the years 1799–1804'' and ''Kosmos'' were influential in his time.

*1799. Georges Cuvier (French, 1769–1832) established comparative anatomy as a field. He also founded the science of paleontology. He wrote ' (1801–1805), ' (1816), ' (1812–1813). He believed in the fixity of species and the Genesis flood narrative, Biblical Flood. His early ' (1798) was influential, but it did not include Cuvier's major contributions to animal classification.

*1799. American hunters killed the last

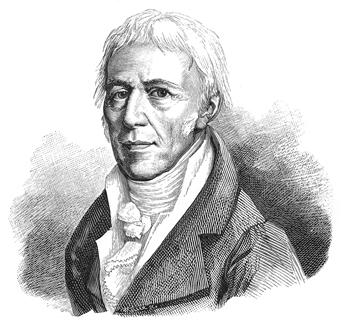

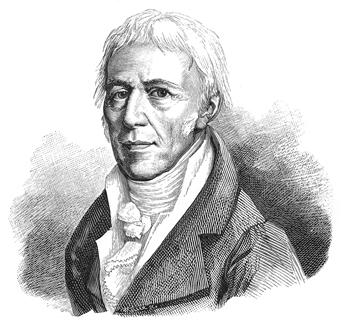

*1802. Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck (French, 1744–1829) wrote ' and ' (1809). He was an early evolutionist and organized invertebrate paleontology. While Lamarck's contributions to science include work in meteorology, botany, chemistry, geology, and paleontology, he is best known for his work in invertebrate zoology and his theoretical work on evolution. He published a seven-volume work, ' ("Natural history of animals without backbones;" 1815–1822).

*1813–1818. William Charles Wells (Scottish-American, 1757–1817) was the first to recognise the principle of natural selection. He read a paper to the Royal Society in 1813 (but not published until 1818) which used the idea to explain differences between Race (human categorization), human races. The application was limited to the question of how different skin colours arose.

*1815. William Kirby (entomologist), William Kirby and William Spence (entomologist), William Spence (English) wrote ''An Introduction to Entomology'' (first edition in 1815). This was the first modern entomology text.

*1817. Publication of ''American Entomology'' by Thomas Say, the first work devoted to American insects. A greatly expanded three-volume edition would appear 1824–1828. Say was a systematic zoologist who moved to the utopian community at New Harmony, Indiana, in 1825. Most of his insect collections have been recovered.

*1817. Georges Cuvier wrote ''Le Règne Animal'' (Paris).

*1817–1820. Johann Baptist von Spix (German, 1781–1826) and Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius (German) conducted Brazilian zoological and botanical explorations (1817–1820). See their ' (3 vols., 1823–1831).

*1817. William Smith (geologist), William Smith, in his ''Strategraphical System of Organized Fossils'' (1817) showed that certain strata have characteristic series of fossils.

*1819 William Lawrence (biologist), William Lawrence (English, 1783–1867) published a book of his lectures to the Royal College of Surgeons. The book contains a rejection of Lamarckism (soft inheritance), proto-evolutionary ideas about the origin of mankind, and a denial of the 'Jewish scriptures' (Old Testament). He was forced to suppress the book after the Lord Chancellor refused copyright and other powerful men made threatening remarks.

*1819. Malayan tapir, a first species of

*1802. Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck (French, 1744–1829) wrote ' and ' (1809). He was an early evolutionist and organized invertebrate paleontology. While Lamarck's contributions to science include work in meteorology, botany, chemistry, geology, and paleontology, he is best known for his work in invertebrate zoology and his theoretical work on evolution. He published a seven-volume work, ' ("Natural history of animals without backbones;" 1815–1822).

*1813–1818. William Charles Wells (Scottish-American, 1757–1817) was the first to recognise the principle of natural selection. He read a paper to the Royal Society in 1813 (but not published until 1818) which used the idea to explain differences between Race (human categorization), human races. The application was limited to the question of how different skin colours arose.

*1815. William Kirby (entomologist), William Kirby and William Spence (entomologist), William Spence (English) wrote ''An Introduction to Entomology'' (first edition in 1815). This was the first modern entomology text.

*1817. Publication of ''American Entomology'' by Thomas Say, the first work devoted to American insects. A greatly expanded three-volume edition would appear 1824–1828. Say was a systematic zoologist who moved to the utopian community at New Harmony, Indiana, in 1825. Most of his insect collections have been recovered.

*1817. Georges Cuvier wrote ''Le Règne Animal'' (Paris).

*1817–1820. Johann Baptist von Spix (German, 1781–1826) and Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius (German) conducted Brazilian zoological and botanical explorations (1817–1820). See their ' (3 vols., 1823–1831).

*1817. William Smith (geologist), William Smith, in his ''Strategraphical System of Organized Fossils'' (1817) showed that certain strata have characteristic series of fossils.

*1819 William Lawrence (biologist), William Lawrence (English, 1783–1867) published a book of his lectures to the Royal College of Surgeons. The book contains a rejection of Lamarckism (soft inheritance), proto-evolutionary ideas about the origin of mankind, and a denial of the 'Jewish scriptures' (Old Testament). He was forced to suppress the book after the Lord Chancellor refused copyright and other powerful men made threatening remarks.

*1819. Malayan tapir, a first species of  *1835. William Swainson (English, 1789–1855) writes ''A Treatise on the Geography and Classification of Animals'' (1835), in which he uses ad hoc land bridges to explain animal distributions. He includes some second-hand observations on Old World army ants.

*1835. Founding of the Archiv für Naturgeschichte, the premier German-language journal of natural history with an emphasis on zoology. It would be published until 1926.

*1839. Theodor Schwann (German, 1810–1882) writes ' (1839). Schwann established the foundation for cell theory.

*1839.

*1835. William Swainson (English, 1789–1855) writes ''A Treatise on the Geography and Classification of Animals'' (1835), in which he uses ad hoc land bridges to explain animal distributions. He includes some second-hand observations on Old World army ants.

*1835. Founding of the Archiv für Naturgeschichte, the premier German-language journal of natural history with an emphasis on zoology. It would be published until 1926.

*1839. Theodor Schwann (German, 1810–1882) writes ' (1839). Schwann established the foundation for cell theory.

*1839.  *1842. Baron Justus von Liebig writes ' in which he suggests that animal heat is produced by combustion, and founds the science of biochemistry.

*1843. John James Audubon, age 58, ascends the Missouri River to Fort Union at the mouth of the Yellowstone to sketch wild animals.

*1844. Berlin Zoo is founded.

*1844. Robert Chambers (journalist), Robert Chambers (Scottish, 1802–1871) writes the ''Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation'' (1844) in which he includes early evolutionary considerations. This book, anonymously published, has a profound effect on Alfred Russel Wallace.

*1845. Karl Theodor Ernst von Siebold, von Siebold recognizes Protozoa as single-celled animals.

*1848. Josiah C. Nott (American), a physician from New Orleans, publishes his belief that mosquitoes transmit

*1842. Baron Justus von Liebig writes ' in which he suggests that animal heat is produced by combustion, and founds the science of biochemistry.

*1843. John James Audubon, age 58, ascends the Missouri River to Fort Union at the mouth of the Yellowstone to sketch wild animals.

*1844. Berlin Zoo is founded.

*1844. Robert Chambers (journalist), Robert Chambers (Scottish, 1802–1871) writes the ''Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation'' (1844) in which he includes early evolutionary considerations. This book, anonymously published, has a profound effect on Alfred Russel Wallace.

*1845. Karl Theodor Ernst von Siebold, von Siebold recognizes Protozoa as single-celled animals.

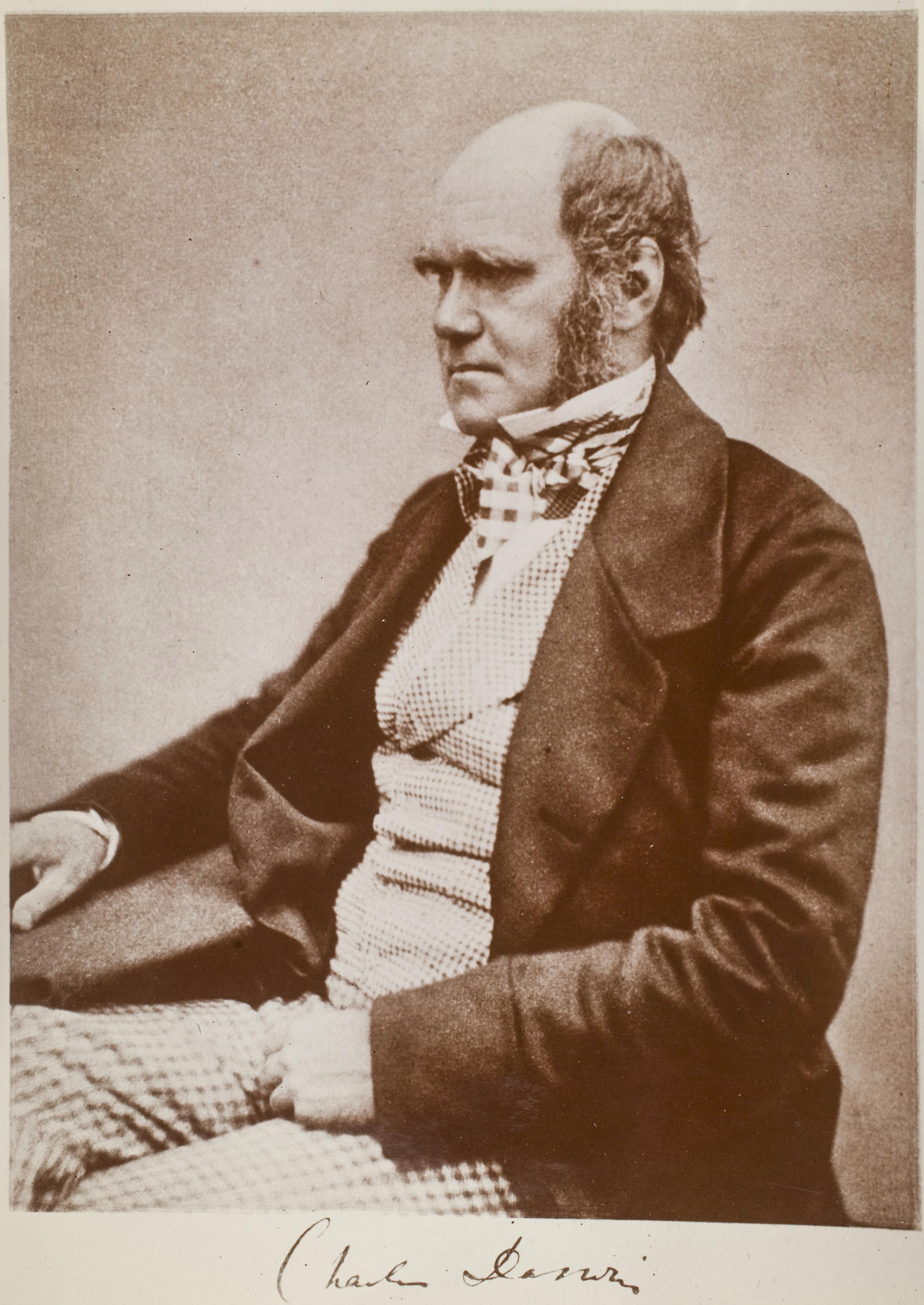

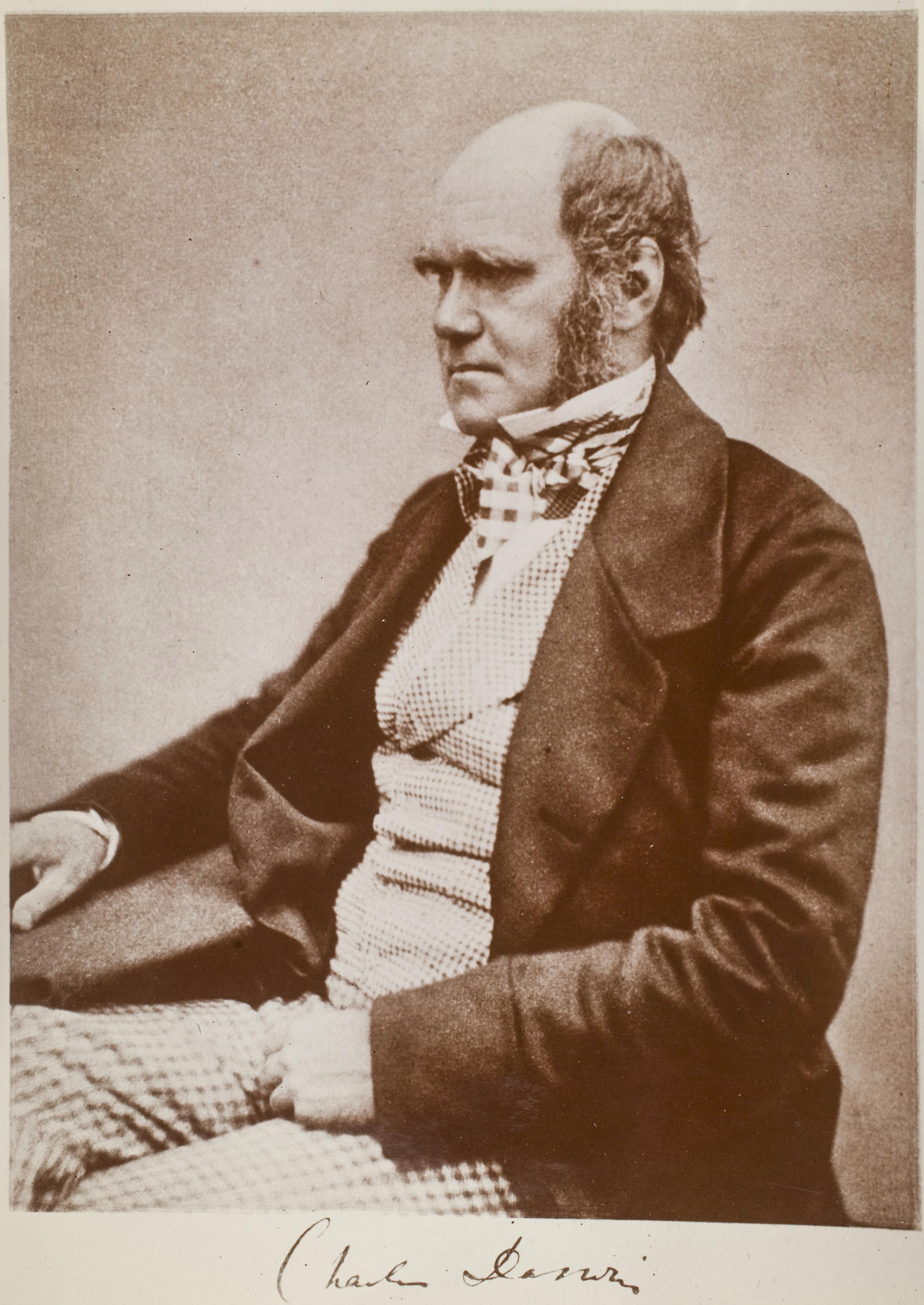

*1848. Josiah C. Nott (American), a physician from New Orleans, publishes his belief that mosquitoes transmit  * 1859. Charles Darwin publishes ''On the Origin of Species'', explaining the mechanism of evolution by natural selection and founding the field of evolutionary biology.

* 1859. Founding of Copenhagen Zoo.

* 1859. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania grants a charter for the founding of the Philadelphia Zoo. However, due to delays caused by the American Civil War the zoo will not open until 1874.

* 1864. Louis Pasteur disproves the spontaneous generation of cellular life.

* 1864. Founding of the Moscow Zoo.

* 1865. Gregor Mendel demonstrates in Pea, pea plants that inheritance follows Mendelian Inheritance, definite rules. The Principle of Segregation states that each organism has two genes per trait, which segregate when the organism makes eggs or sperm. The Principle of Independent Assortment states that each gene in a pair is distributed independently during the formation of eggs or sperm. Mendel's observations went largely unnoticed.

* 1868. Founding of the Lincoln Park Zoo in Chicago, Chicago, Illinois.

* 1869. Friedrich Miescher discovers nucleic acids in the cell nucleus, nuclei of cells.

* 1872. Darwin publishes The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals.

* 1873. Founding of the Cincinnati Zoo.

* 1876. Oskar Hertwig and Hermann Fol independently describe (in sea urchin eggs) the entry of sperm into the egg and the subsequent fusion of the egg and sperm nuclei to form a single new nucleus.

* 1876. Founding of the Société zoologique de France.

* 1878. Founding of the Zoological Society of Japan.

* 1881. Przewalski's horse is described.

* 1885. Polypodium hydriforme, an unusual cnidarian, is described.

* 1889. Founding of the National Zoological Park (United States) as part of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

* 1889. The first species of marsupial mole is described.

* 1892. Hans Driesch separates the individual cells of a 2-cell sea urchin embryo, and shows that each cell develops into a complete individual, thus disproving the theory of preformation, and demonstrating that each cell is "totipotent," containing all the hereditary information necessary to form an individual.

* 1895. Founding of the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature, the body which continues to govern zoological nomenclature.

* 1899. Founding of the Bronx Zoo.

* 1900. Three biologists, Hugo de Vries, Carl Correns, Erich von Tschermak, independently rediscover Mendel's paper on heredity.

* 1900. Founding of the Unione Zoologica Italiana.

* 1900. First species of Siboglinidae discovered.

* 1859. Charles Darwin publishes ''On the Origin of Species'', explaining the mechanism of evolution by natural selection and founding the field of evolutionary biology.

* 1859. Founding of Copenhagen Zoo.

* 1859. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania grants a charter for the founding of the Philadelphia Zoo. However, due to delays caused by the American Civil War the zoo will not open until 1874.

* 1864. Louis Pasteur disproves the spontaneous generation of cellular life.

* 1864. Founding of the Moscow Zoo.

* 1865. Gregor Mendel demonstrates in Pea, pea plants that inheritance follows Mendelian Inheritance, definite rules. The Principle of Segregation states that each organism has two genes per trait, which segregate when the organism makes eggs or sperm. The Principle of Independent Assortment states that each gene in a pair is distributed independently during the formation of eggs or sperm. Mendel's observations went largely unnoticed.

* 1868. Founding of the Lincoln Park Zoo in Chicago, Chicago, Illinois.

* 1869. Friedrich Miescher discovers nucleic acids in the cell nucleus, nuclei of cells.

* 1872. Darwin publishes The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals.

* 1873. Founding of the Cincinnati Zoo.

* 1876. Oskar Hertwig and Hermann Fol independently describe (in sea urchin eggs) the entry of sperm into the egg and the subsequent fusion of the egg and sperm nuclei to form a single new nucleus.

* 1876. Founding of the Société zoologique de France.

* 1878. Founding of the Zoological Society of Japan.

* 1881. Przewalski's horse is described.

* 1885. Polypodium hydriforme, an unusual cnidarian, is described.

* 1889. Founding of the National Zoological Park (United States) as part of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

* 1889. The first species of marsupial mole is described.

* 1892. Hans Driesch separates the individual cells of a 2-cell sea urchin embryo, and shows that each cell develops into a complete individual, thus disproving the theory of preformation, and demonstrating that each cell is "totipotent," containing all the hereditary information necessary to form an individual.

* 1895. Founding of the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature, the body which continues to govern zoological nomenclature.

* 1899. Founding of the Bronx Zoo.

* 1900. Three biologists, Hugo de Vries, Carl Correns, Erich von Tschermak, independently rediscover Mendel's paper on heredity.

* 1900. Founding of the Unione Zoologica Italiana.

* 1900. First species of Siboglinidae discovered.

* 1938. A living coelacanth is found off the coast of southern Africa.

* 1940. Donald Griffin and Robert Galambos announce their discovery of Animal echolocation, echolocation by bats.

* 1938. A living coelacanth is found off the coast of southern Africa.

* 1940. Donald Griffin and Robert Galambos announce their discovery of Animal echolocation, echolocation by bats.

Mc-Graw HillWonders of Nature in the Menagerie of Blauw Jan in Amsterdam, as observed by Jan Velten around 1700Exotic Animals in Eighteenth-Century BritainZoologica

Göttingen State and University Library {{DEFAULTSORT:Timeline Of Zoology Zoology timelines, History of zoology

zoological

Zoology ( , ) is the scientific study of animals. Its studies include the anatomy, structure, embryology, Biological classification, classification, Ethology, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinction, extinct, and ...

events and discoveries.

Ancient world

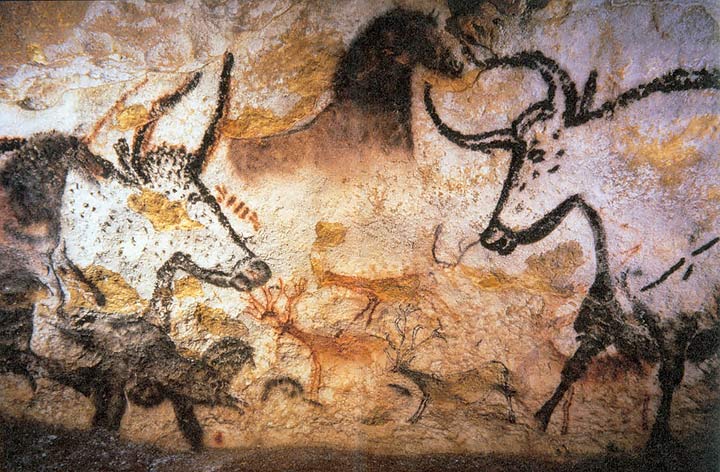

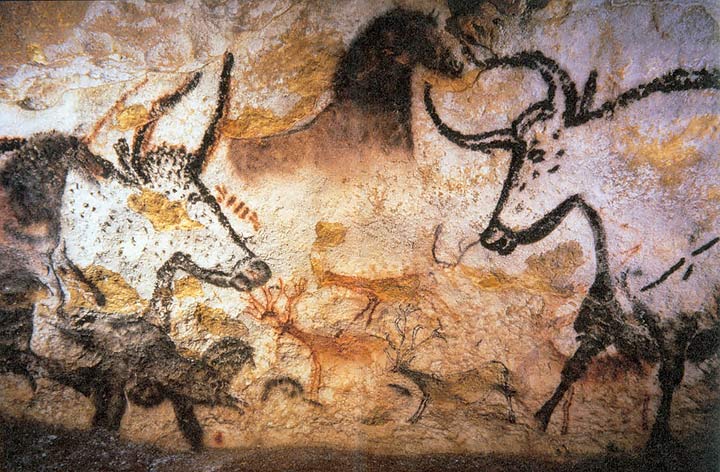

*28000 BC.Cave painting

In archaeology, cave paintings are a type of parietal art (which category also includes petroglyphs, or engravings), found on the wall or ceilings of caves. The term usually implies prehistoric art, prehistoric origin. These paintings were often c ...

s (e.g. Chauvet Cave

The Chauvet-Pont-d'Arc Cave ( ) in the Ardèche department of southeastern France is a cave that contains some of the best-preserved figurative cave paintings in the world, as well as other evidence of Upper Paleolithic life.Clottes (2003b), p. ...

) in Southern France

Southern France, also known as the south of France or colloquially in French as , is a geographical area consisting of the regions of France that border the Atlantic Ocean south of the Marais Poitevin,Louis Papy, ''Le midi atlantique'', Atlas e ...

and northern Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

depict animals such as mammoths

A mammoth is any species of the extinct elephantid genus ''Mammuthus.'' They lived from the late Miocene epoch (from around 6.2 million years ago) into the Holocene until about 4,000 years ago, with mammoth species at various times inhabi ...

in a stylized fashion.

*12000–8000 BC. Bubalus Period creation of rock art in the Central Sahara depicting a range of animals including elephants

Elephants are the Largest and heaviest animals, largest living land animals. Three living species are currently recognised: the African bush elephant (''Loxodonta africana''), the African forest elephant (''L. cyclotis''), and the Asian ele ...

, antelopes

The term antelope refers to numerous extant or recently extinct species of the ruminant artiodactyl family Bovidae that are indigenous to most of Africa, India, the Middle East, Central Asia, and a small area of Eastern Europe. Antelopes do no ...

, rhinoceros

A rhinoceros ( ; ; ; : rhinoceros or rhinoceroses), commonly abbreviated to rhino, is a member of any of the five extant taxon, extant species (or numerous extinct species) of odd-toed ungulates (perissodactyls) in the family (biology), famil ...

and catfish

Catfish (or catfishes; order (biology), order Siluriformes or Nematognathi) are a diverse group of ray-finned fish. Catfish are common name, named for their prominent barbel (anatomy), barbels, which resemble a cat's whiskers, though not ...

.

*10000 BC. Humans (''Homo sapiens

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') or modern humans are the most common and widespread species of primate, and the last surviving species of the genus ''Homo''. They are Hominidae, great apes characterized by their Prehistory of nakedness and clothing ...

'') domesticated

Domestication is a multi-generational mutualistic relationship in which an animal species, such as humans or leafcutter ants, takes over control and care of another species, such as sheep or fungi, to obtain from them a steady supply of reso ...

dog

The dog (''Canis familiaris'' or ''Canis lupus familiaris'') is a domesticated descendant of the gray wolf. Also called the domestic dog, it was selectively bred from a population of wolves during the Late Pleistocene by hunter-gatherers. ...

s, pig

The pig (''Sus domesticus''), also called swine (: swine) or hog, is an omnivorous, domesticated, even-toed, hoofed mammal. It is named the domestic pig when distinguishing it from other members of the genus '' Sus''. Some authorities cons ...

s, sheep

Sheep (: sheep) or domestic sheep (''Ovis aries'') are a domesticated, ruminant mammal typically kept as livestock. Although the term ''sheep'' can apply to other species in the genus '' Ovis'', in everyday usage it almost always refers to d ...

, goat

The goat or domestic goat (''Capra hircus'') is a species of Caprinae, goat-antelope that is mostly kept as livestock. It was domesticated from the wild goat (''C. aegagrus'') of Southwest Asia and Eastern Europe. The goat is a member of the ...

s, fowl

Fowl are birds belonging to one of two biological orders, namely the gamefowl or landfowl ( Galliformes) and the waterfowl ( Anseriformes). Anatomical and molecular similarities suggest these two groups are close evolutionary relatives; toget ...

, and other animals in Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

, northern Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

and the Near East

The Near East () is a transcontinental region around the Eastern Mediterranean encompassing the historical Fertile Crescent, the Levant, Anatolia, Egypt, Mesopotamia, and coastal areas of the Arabian Peninsula. The term was invented in the 20th ...

.

*6500 BC. The aurochs

The aurochs (''Bos primigenius''; or ; pl.: aurochs or aurochsen) is an extinct species of Bovini, bovine, considered to be the wild ancestor of modern domestic cattle. With a shoulder height of up to in bulls and in cows, it was one of t ...

, ancestors of domestic cattle

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, bovid ungulates widely kept as livestock. They are prominent modern members of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus '' Bos''. Mature female cattle are calle ...

, were domesticated in the next two centuries if not earlier (Obre I, Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

). This was the last major animal to be tamed as a source of milk, meat, power, and leather in the Old World

The "Old World" () is a term for Afro-Eurasia coined by Europeans after 1493, when they became aware of the existence of the Americas. It is used to contrast the continents of Africa, Europe, and Asia in the Eastern Hemisphere, previously ...

.

*3500 BC.

*3500 BC. Sumer

Sumer () is the earliest known civilization, located in the historical region of southern Mesopotamia (now south-central Iraq), emerging during the Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age, early Bronze Ages between the sixth and fifth millennium BC. ...

ian animal-drawn wheeled vehicles and plows were developed in Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

, the region called the "Fertile Crescent

The Fertile Crescent () is a crescent-shaped region in the Middle East, spanning modern-day Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, and Syria, together with northern Kuwait, south-eastern Turkey, and western Iran. Some authors also include ...

." Irrigation

Irrigation (also referred to as watering of plants) is the practice of applying controlled amounts of water to land to help grow crops, landscape plants, and lawns. Irrigation has been a key aspect of agriculture for over 5,000 years and has bee ...

was probably done using animal power. Since Sumer had no natural defenses, armies with mounted cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from ''cheval'' meaning "horse") are groups of soldiers or warriors who Horses in warfare, fight mounted on horseback. Until the 20th century, cavalry were the most mob ...

and chariot

A chariot is a type of vehicle similar to a cart, driven by a charioteer, usually using horses to provide rapid Propulsion, motive power. The oldest known chariots have been found in burials of the Sintashta culture in modern-day Chelyabinsk O ...

s became important which increased the importance of equines

''Equus'' () is a genus of mammals in the perissodactyl family (biology), family Equidae, which includes wild horse, horses, Asinus, asses, and zebras. Within the Equidae, ''Equus'' is the only recognized Extant taxon, extant genus, comprising s ...

.

*2000 BC. Domestication of the silkworm

''Bombyx mori'', commonly known as the domestic silk moth, is a moth species belonging to the family Bombycidae. It is the closest relative of '' Bombyx mandarina'', the wild silk moth. Silkworms are the larvae of silk moths. The silkworm is of ...

in China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

.

*1100 BC. Won Chang (China), first of the Zhou emperors, stocked his imperial zoological garden

A zoo (short for zoological garden; also called an animal park or menagerie) is a facility where animals are kept within enclosures for public exhibition and often bred for Conservation biology, conservation purposes.

The term ''zoological garden ...

with deer

A deer (: deer) or true deer is a hoofed ruminant ungulate of the family Cervidae (informally the deer family). Cervidae is divided into subfamilies Cervinae (which includes, among others, muntjac, elk (wapiti), red deer, and fallow deer) ...

, goat

The goat or domestic goat (''Capra hircus'') is a species of Caprinae, goat-antelope that is mostly kept as livestock. It was domesticated from the wild goat (''C. aegagrus'') of Southwest Asia and Eastern Europe. The goat is a member of the ...

s, bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

s, and fish

A fish (: fish or fishes) is an aquatic animal, aquatic, Anamniotes, anamniotic, gill-bearing vertebrate animal with swimming fish fin, fins and craniate, a hard skull, but lacking limb (anatomy), limbs with digit (anatomy), digits. Fish can ...

from many parts of the world. The emperor also enjoyed sporting events with the use of animals.

*850 BC. Homer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

(Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

) wrote the epics Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; , ; ) is one of two major Ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Odyssey'', the poem is divided into 24 books and ...

and Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; ) is one of two major epics of ancient Greek literature attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest surviving works of literature and remains popular with modern audiences. Like the ''Iliad'', the ''Odyssey'' is divi ...

, both of them containing some correct observations on bees and fly maggots, while using animals as monster

A monster is a type of imaginary or fictional creature found in literature, folklore, mythology, fiction and religion. They are very often depicted as dangerous and aggressive, with a strange or grotesque appearance that causes Anxiety, terror ...

s and metaphor

A metaphor is a figure of speech that, for rhetorical effect, directly refers to one thing by mentioning another. It may provide, or obscure, clarity or identify hidden similarities between two different ideas. Metaphors are usually meant to cr ...

s (gross soldiers turned into pig

The pig (''Sus domesticus''), also called swine (: swine) or hog, is an omnivorous, domesticated, even-toed, hoofed mammal. It is named the domestic pig when distinguishing it from other members of the genus '' Sus''. Some authorities cons ...

s by the witch Circe

In Greek mythology, Circe (; ) is an enchantress, sometimes considered a goddess or a nymph. In most accounts, Circe is described as the daughter of the sun god Helios and the Oceanid Perse (mythology), Perse. Circe was renowned for her vast kn ...

). Both epics refer to mule

The mule is a domestic equine hybrid between a donkey, and a horse. It is the offspring of a male donkey (a jack) and a female horse (a mare). The horse and the donkey are different species, with different numbers of chromosomes; of the two ...

s.

*610 BC. Anaximander

Anaximander ( ; ''Anaximandros''; ) was a Pre-Socratic philosophy, pre-Socratic Ancient Greek philosophy, Greek philosopher who lived in Miletus,"Anaximander" in ''Chambers's Encyclopædia''. London: George Newnes Ltd, George Newnes, 1961, Vol. ...

(Greek, 610–545 BC) was a student of Thales of Miletus

Thales of Miletus ( ; ; ) was an Ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher from Miletus in Ionia, Asia Minor. Thales was one of the Seven Sages, founding figures of Ancient Greece.

Beginning in eighteenth-century historiography, many came to ...

. He was taught that the first life was formed by spontaneous generation

Spontaneous generation is a superseded scientific theory that held that living creatures could arise from non-living matter and that such processes were commonplace and regular. It was hypothesized that certain forms, such as fleas, could ...

in the mud. Later animals came into being by transmutations, left the water, and reached dry land. Man was derived from lower animals, probably aquatic. His writings, especially his poem ''On Nature'', were read and cited by Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

and other later philosophers, but are lost now.

*563? BC. Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha (),*

*

*

was a wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism. According to Buddhist legends, he was ...

(Indian, 563?–483 BC) had gentle ideas on the treatment of animals. He said that animals are held to have intrinsic worth, not just the values they derive from their usefulness to man.

*500 BC. Empedocles

Empedocles (; ; , 444–443 BC) was a Ancient Greece, Greek pre-Socratic philosopher and a native citizen of Akragas, a Greek city in Sicily. Empedocles' philosophy is known best for originating the Cosmogony, cosmogonic theory of the four cla ...

of Agrigentum (Greek, 504–433 BC) reportedly rid a town of malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

by draining nearby swamps. He proposed the theory of the four humors

Humorism, the humoral theory, or humoralism, was a system of medicine detailing a supposed makeup and workings of the human body, adopted by Ancient Greek and Roman physicians and philosophers.

Humorism began to fall out of favor in the 17th ce ...

and a natural origin of living things.

*500 BC.

*500 BC. Xenophanes

Xenophanes of Colophon ( ; ; – c. 478 BC) was a Greek philosopher, theologian, poet, and critic of Homer. He was born in Ionia and travelled throughout the Greek-speaking world in early classical antiquity.

As a poet, Xenophanes was known f ...

(Greek, 576–460 BC), a disciple of Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos (; BC) was an ancient Ionian Greek philosopher, polymath, and the eponymous founder of Pythagoreanism. His political and religious teachings were well known in Magna Graecia and influenced the philosophies of P ...

(570–497 BC), first recognized fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

s as animal remains and inferred that their presence on mountains indicated the latter had once been beneath the sea. "If horses or oxen had hands and could draw or make statues, horses would represent the forms of gods as horses, oxen as oxen." Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus (; September 129 – AD), often Anglicization, anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Ancient Rome, Roman and Greeks, Greek physician, surgeon, and Philosophy, philosopher. Considered to be one o ...

(130–216 AD) revived interest in fossils that had been rejected by Aristotle, and the speculations of Xenophanes were again viewed with favor.

*470 BC. Democritus

Democritus (, ; , ''Dēmókritos'', meaning "chosen of the people"; – ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek Pre-Socratic philosophy, pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, Thrace, Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an ...

of Abdera (Greek, 470–370 BC) made dissections of many animals and humans. He was the first Greek philosopher-scientist to propose a classification of animals, dividing them into blooded animals (Vertebrata) and bloodless animals (Evertebrata). He also held that lower animals had perfected organs and that the brain was the seat of thought.

*460 BC. Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; ; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician and philosopher of the Classical Greece, classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history of medicine. He is traditionally referr ...

(Greek, 460–370 BC), the "Father of Medicine," used animal dissections to advance human anatomy.

*440 BC. Herodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

of Halikarnassos

Halicarnassus ( ; Latin: ''Halicarnassus'' or ''Halicarnāsus''; ''Halikarnāssós''; ; Carian: 𐊠𐊣𐊫𐊰 𐊴𐊠𐊥𐊵𐊫𐊰 ''alos k̂arnos'') was an ancient Greek city in Caria, in Anatolia.Nile

The Nile (also known as the Nile River or River Nile) is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa. It has historically been considered the List of river sy ...

, but much of ancient Egyptian civilization

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower ...

had already lost to living memory by his time.

*427 BC. Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

(Greek, 427–347 BC) held that animals existed to serve man, but they should not be mistreated because this would lead people to mistreat others. Others who echoed this opinion are St. Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas ( ; ; – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest, the foremost Scholasticism, Scholastic thinker, as well as one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the W ...

, Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German Philosophy, philosopher and one of the central Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works ...

, and Albert Schweitzer

Ludwig Philipp Albert Schweitzer (; 14 January 1875 – 4 September 1965) was a German and French polymath from Alsace. He was a theologian, organist, musicologist, writer, humanitarian, philosopher, and physician. As a Lutheran minister, ...

.

*384 BC. Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

's (Greek, 384–322 BC) books '' Historia Animalium'' (9 books), ', and ' set the zoological stage for centuries. He emphasized the value of direct observation, recognized law and order in biological phenomena, and derived conclusions inductively from observations. He believed that there was a natural process of animals that ran from simple to complex. He made advances in marine biology

Marine biology is the scientific study of the biology of marine life, organisms that inhabit the sea. Given that in biology many scientific classification, phyla, family (biology), families and genera have some species that live in the sea and ...

, basing his writings on keen observation and rational interpretation as well as conversations with local Lesbos

Lesbos or Lesvos ( ) is a Greek island located in the northeastern Aegean Sea. It has an area of , with approximately of coastline, making it the third largest island in Greece and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, eighth largest ...

fishermen for two years, beginning in 344 BC. His account of male protection of eggs by the barking catfish was scorned for centuries until Louis Agassiz

Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz ( ; ) FRS (For) FRSE (May 28, 1807 – December 14, 1873) was a Swiss-born American biologist and geologist who is recognized as a scholar of Earth's natural history.

Spending his early life in Switzerland, he recei ...

confirmed Aristotle's description.

*323 BC.

*323 BC. Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

(Macedonian, 356–323 BC) collected animals when he was not busy conquering the known world. He is credited with the introduction of the peacock

Peafowl is a common name for two bird species of the genus '' Pavo'' and one species of the closely related genus '' Afropavo'' within the tribe Pavonini of the family Phasianidae (the pheasants and their allies). Male peafowl are referred t ...

into Europe.

*70 BC. Publius Vergilius Maro (Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; 15 October 70 BC21 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Rome, ancient Roman poet of the Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Augustan period. He composed three of the most fa ...

) (70–19 BC) was a famous Roman poet. His poems ''Bucolics'' (42–37 BC) and ''Georgics'' (37–30 BC) hold much information on animal husbandry and farm life. His ''Aeneid'' (published posthumously) has many references to the zoology of his time.

*36 BC. Marcus Terentius Varro

Marcus Terentius Varro (116–27 BCE) was a Roman polymath and a prolific author. He is regarded as ancient Rome's greatest scholar, and was described by Petrarch as "the third great light of Rome" (after Virgil and Cicero). He is sometimes call ...

(116–27 BC) wrote ', a treatise that includes apiculture

Beekeeping (or apiculture, from ) is the maintenance of bee colonies, commonly in artificial beehives. Honey bees in the genus ''Apis (bee), Apis'' are the most commonly kept species but other honey producing bees such as ''Melipona'' stingless be ...

. He also treated the problem of sterility in the mule

The mule is a domestic equine hybrid between a donkey, and a horse. It is the offspring of a male donkey (a jack) and a female horse (a mare). The horse and the donkey are different species, with different numbers of chromosomes; of the two ...

and recorded a rare instance in which a fertile mule was bred.

*50. Lucius Annaeus Seneca

Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Younger ( ; AD 65), usually known mononymously as Seneca, was a Stoicism, Stoic philosopher of Ancient Rome, a statesman, a dramatist, and in one work, a satirist, from the post-Augustan age of Latin literature.

Seneca ...

(Roman, 4 BC–65 AD), tutor to Roman emperor Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68) was a Roman emperor and the final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 until his ...

, maintained that animals have no reason, just instinct, a "stoic" position.

*77.

*77. Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/24 79), known in English as Pliny the Elder ( ), was a Roman Empire, Roman author, Natural history, naturalist, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the Roman emperor, emperor Vesp ...

(Roman, 23–79) wrote his ' in 37 volumes. This work is a catch-all of zoological folklore, superstitions, and some good observations.

*79. Pliny the Younger

Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus (born Gaius Caecilius or Gaius Caecilius Cilo; 61 – ), better known in English as Pliny the Younger ( ), was a lawyer, author, and magistrate of Ancient Rome. Pliny's uncle, Pliny the Elder, helped raise and e ...

(Roman, 62–113), nephew of Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/24 79), known in English as Pliny the Elder ( ), was a Roman Empire, Roman author, Natural history, naturalist, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the Roman emperor, emperor Vesp ...

, inherited his uncle's notes and wrote on beekeeping.

*100. Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

(Roman, 46–120) stated that animals' behavior is motivated by reason and understanding.

*131. Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus (; September 129 – AD), often Anglicization, anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Ancient Rome, Roman and Greeks, Greek physician, surgeon, and Philosophy, philosopher. Considered to be one o ...

of Pergamum (Greek, 130–216), physician to Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus ( ; ; 26 April 121 – 17 March 180) was Roman emperor from 161 to 180 and a Stoicism, Stoic philosopher. He was a member of the Nerva–Antonine dynasty, the last of the rulers later known as the Five Good Emperors ...

, wrote on human anatomy from dissections of animals. His texts were used for hundreds of years, gaining the reputation of infallibility.

*200 c. Various compilers in post-classical and medieval times added to the ' (or, more popularly, the ''Bestiary''), the major book on animals for hundreds of years. Animals were believed to exist to serve man, if not as food or slaves then as moral examples.

*Early third century. Composition of ''De Natura Animalium'' by Claudius Aelianus

Claudius Aelianus (; ), commonly Aelian (), born at Praeneste, was a Roman author and teacher of rhetoric who flourished under Septimius Severus and probably outlived Elagabalus, who died in 222. He spoke Greek so fluently that he was called "h ...

(Roman, 175–235).

Middle Ages

*600. Isidorus Hispalensis (Spanish bishop ofSeville

Seville ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Spain, Spanish autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the Guadalquivir, River Guadalquivir, ...

) (560–636) wrote ', an encyclopedic compendium of ancient knowledge including information on animals that served until the rediscovery of Aristotle and Pliny. Full of errors, it nevertheless was influential for hundreds of years. He also wrote '.

*781. Al-Jahiz

Abu Uthman Amr ibn Bahr al-Kinani al-Basri (; ), commonly known as al-Jahiz (), was an Arab polymath and author of works of literature (including theory and criticism), theology, zoology, philosophy, grammar, dialectics, rhetoric, philology, lin ...

(Afro-Arab, 781–868/869), a scholar at Basra

Basra () is a port city in Iraq, southern Iraq. It is the capital of the eponymous Basra Governorate, as well as the List of largest cities of Iraq, third largest city in Iraq overall, behind Baghdad and Mosul. Located near the Iran–Iraq bor ...

, wrote on the influence of environment on animals.

*901. Horse

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 mi ...

s came into wider use in those parts of Europe where the three-field system

The three-field system is a regime of crop rotation in which a field is planted with one set of crops one year, a different set in the second year, and left fallow in the third year. A set of crops is ''rotated'' from one field to another. The tech ...

produces grain surpluses for feed, but hay-fed oxen were more economical, if less efficient, in terms of time and labor and remained almost the sole source of animal power in southern Europe, where most farmers continued to use the two-field system.

*1225–1244. Thomas of Cantimpré

Thomas of Cantimpré (Latin: Thomas Cantimpratensis or Thomas Cantipratensis) (Sint-Pieters-Leeuw, 1201 – Louvain, 15 May 1272) was a Flemish Region, Flemish Catholic medieval writer, preacher, theologian and a friar belonging to the Dominican ...

‚ (Fleming, 1204?–1275?) wrote ', a major 13th-century encyclopedia.

*1244–1248. Frederick II von Hohenstaufen (Holy Roman Emperor) (1194–1250) wrote ' (''The Art of Hunting with Birds'') as a practical guide to

*1244–1248. Frederick II von Hohenstaufen (Holy Roman Emperor) (1194–1250) wrote ' (''The Art of Hunting with Birds'') as a practical guide to ornithology

Ornithology, from Ancient Greek ὄρνις (''órnis''), meaning "bird", and -logy from λόγος (''lógos''), meaning "study", is a branch of zoology dedicated to the study of birds. Several aspects of ornithology differ from related discip ...

.

*1244. Vincentius Bellovacensis ( Vincent of Beauvais) (1190–1264) wrote ' (1244–1254), a major encyclopedia. This work comprises three huge volumes, of 80 books and 9,885 chapters.

*1254–1323.

*1244. Vincentius Bellovacensis ( Vincent of Beauvais) (1190–1264) wrote ' (1244–1254), a major encyclopedia. This work comprises three huge volumes, of 80 books and 9,885 chapters.

*1254–1323. Marco Polo

Marco Polo (; ; ; 8 January 1324) was a Republic of Venice, Venetian merchant, explorer and writer who travelled through Asia along the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295. His travels are recorded in ''The Travels of Marco Polo'' (also known a ...

(Venetian, 1254–1323) provided information on Asiatic fauna, revealing new animals to Europeans. "Unicorn

The unicorn is a legendary creature that has been described since Classical antiquity, antiquity as a beast with a single large, pointed, spiraling horn (anatomy), horn projecting from its forehead.

In European literature and art, the unico ...

s" (which may actually have been rhinos) were reported from southern China, but fantastic animals were otherwise not included.

*1255–1270. Albertus Magnus

Albertus Magnus ( 1200 – 15 November 1280), also known as Saint Albert the Great, Albert of Swabia, Albert von Bollstadt, or Albert of Cologne, was a German Dominican friar, philosopher, scientist, and bishop, considered one of the great ...

of Cologne

Cologne ( ; ; ) is the largest city of the States of Germany, German state of North Rhine-Westphalia and the List of cities in Germany by population, fourth-most populous city of Germany with nearly 1.1 million inhabitants in the city pr ...

(Bavarian, 1206?–1280) (Albert von Bollstaedt or St. Albert) wrote '. He promoted Aristotle but also included new material on the perfection and intelligence of animals, especially bees.

*1304–1309. Petrus de Crescentii wrote ', a practical manual for agriculture with many accurate observations on insect

Insects (from Latin ') are Hexapoda, hexapod invertebrates of the class (biology), class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (Insect morphology#Head, head, ...

s and other animals. Apiculture

Beekeeping (or apiculture, from ) is the maintenance of bee colonies, commonly in artificial beehives. Honey bees in the genus ''Apis (bee), Apis'' are the most commonly kept species but other honey producing bees such as ''Melipona'' stingless be ...

was discussed at length.

*1492.

*1492. Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus (; between 25 August and 31 October 1451 – 20 May 1506) was an Italians, Italian explorer and navigator from the Republic of Genoa who completed Voyages of Christopher Columbus, four Spanish-based voyages across the At ...

(Italian) arrives in the New World

The term "New World" is used to describe the majority of lands of Earth's Western Hemisphere, particularly the Americas, and sometimes Oceania."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: ...

. New animals soon begin to overload European zoology. Columbus is said to have introduced cattle, horses, and eight pigs from the Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; ) or Canaries are an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean and the southernmost Autonomous communities of Spain, Autonomous Community of Spain. They are located in the northwest of Africa, with the closest point to the cont ...

to Hispaniola

Hispaniola (, also ) is an island between Geography of Cuba, Cuba and Geography of Puerto Rico, Puerto Rico in the Greater Antilles of the Caribbean. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and the second-largest by List of C ...

in 1493, giving rise to virtual devastation of that and other islands. Pigs were often set ashore by sailors to provide food on the ship's later return. Feral populations of hogs were often dangerous to humans.

*1519–1520. Bernal Diaz del Castillo (Spanish, 1450?–1500), chronicler of Cortez's conquest of Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

, commented on the zoological gardens of Aztec

The Aztecs ( ) were a Mesoamerican civilization that flourished in central Mexico in the Post-Classic stage, post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different Indigenous peoples of Mexico, ethnic groups of central ...

ruler Montezuma (1466–1520), a marvel with parrot

Parrots (Psittaciformes), also known as psittacines (), are birds with a strong curved beak, upright stance, and clawed feet. They are classified in four families that contain roughly 410 species in 101 genus (biology), genera, found mostly in ...

s, rattlesnake

Rattlesnakes are venomous snakes that form the genus, genera ''Crotalus'' and ''Sistrurus'' of the subfamily Crotalinae (the pit vipers). All rattlesnakes are vipers. Rattlesnakes are predators that live in a wide array of habitats, hunting sm ...

s, and other animals.

*1523. Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés

Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés (August 1478 – 1557), commonly known as Oviedo, was a Spanish soldier, historian, writer, botanist and colonist. Oviedo participated in the Spanish colonization of the West Indies, arriving in the first fe ...

(Spanish, 1478–1557), appointed official historiographer of the Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies) is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The ''Indies'' broadly referred to various lands in the East or the Eastern Hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainlands found i ...

in 1523, wrote ''Sumario de la Natural Historia delas Indias'' (Toledo, 1527). He was the first to describe many New World animals, such as the tapir

Tapirs ( ) are large, herbivorous mammals belonging to the family Tapiridae. They are similar in shape to a Suidae, pig, with a short, prehensile nose trunk (proboscis). Tapirs inhabit jungle and forest regions of South America, South and Centr ...

, opossum

Opossums () are members of the marsupial order Didelphimorphia () endemic to the Americas. The largest order of marsupials in the Western Hemisphere, it comprises 126 species in 18 genera. Opossums originated in South America and entered North A ...

, manatee

Manatees (, family (biology), family Trichechidae, genus ''Trichechus'') are large, fully aquatic, mostly herbivory, herbivorous marine mammals sometimes known as sea cows. There are three accepted living species of Trichechidae, representing t ...

, iguana

''Iguana'' (, ) is a genus of herbivorous lizards that are native to tropical areas of Mexico, Central America, South America, and the Caribbean. The genus was first described by Austrian naturalist Josephus Nicolaus Laurenti, J.N. Laurenti in ...

, armadillo

Armadillos () are New World placental mammals in the order (biology), order Cingulata. They form part of the superorder Xenarthra, along with the anteaters and sloths. 21 extant species of armadillo have been described, some of which are dis ...

, anteater

Anteaters are the four extant mammal species in the suborder Vermilingua (meaning "worm tongue"), commonly known for eating ants and termites. The individual species have other names in English and other languages. Together with sloths, they ar ...

s, sloth

Sloths are a Neotropical realm, Neotropical group of xenarthran mammals constituting the suborder Folivora, including the extant Arboreal locomotion, arboreal tree sloths and extinct terrestrial ground sloths. Noted for their slowness of move ...

, pelican

Pelicans (genus ''Pelecanus'') are a genus of large water birds that make up the family Pelecanidae. They are characterized by a long beak and a large throat pouch used for catching prey and draining water from the scooped-up contents before ...

, and hummingbird

Hummingbirds are birds native to the Americas and comprise the Family (biology), biological family Trochilidae. With approximately 366 species and 113 genus, genera, they occur from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego, but most species are found in Cen ...

s.

Modern world

*1551–1555. Pierre Belon (French, 1517–1564) wrote ' (1551) and ' (1555). This latter work included 110 animal species and offered many new observations and corrections to Herodotus. ' (1555) was his picture book, with improved animal classification and accurate anatomical drawings. In this he published a man's and a bird's skeleton side by side to show the resemblance. He discovered an armadillo shell in a market in

*1551–1555. Pierre Belon (French, 1517–1564) wrote ' (1551) and ' (1555). This latter work included 110 animal species and offered many new observations and corrections to Herodotus. ' (1555) was his picture book, with improved animal classification and accurate anatomical drawings. In this he published a man's and a bird's skeleton side by side to show the resemblance. He discovered an armadillo shell in a market in Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

, showing how Muslims were distributing the finds from the New World.

*1551. Conrad Gessner

Conrad Gessner (; ; 26 March 1516 – 13 December 1565) was a Swiss physician, naturalist, bibliographer, and philologist. Born into a poor family in Zürich, Switzerland, his father and teachers quickly realised his talents and supported him t ...

(Swiss, 1516–1565) wrote ' (Tiguri, 4 vols., 1551–1558, last volume published in 1587) and gained renown. This work, although uncritically compiled in places, was consulted for over 200 years. He also wrote ' (1553) and ' (1563).

*1552 Edward Wotton (English, 1492–1555) published ', a work that influenced Gessner.

*1554–1555. Guillaume Rondelet (French, 1507–1566) wrote ' (1554) and ' (1555). He gathered vernacular

Vernacular is the ordinary, informal, spoken language, spoken form of language, particularly when perceptual dialectology, perceived as having lower social status or less Prestige (sociolinguistics), prestige than standard language, which is mor ...

names in hope of being able to identify the animal in question. He did go to print with discoveries that disagreed with Aristotle.

*1578. Jean de Lery (French, 1534–1611) was a member of the French colony at Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro, or simply Rio, is the capital of the Rio de Janeiro (state), state of Rio de Janeiro. It is the List of cities in Brazil by population, second-most-populous city in Brazil (after São Paulo) and the Largest cities in the America ...

. He published ' (1578) with observations on the local fauna.

*1585. Thomas Harriot

Thomas Harriot (; – 2 July 1621), also spelled Harriott, Hariot or Heriot, was an English astronomer, mathematician, ethnographer and translator to whom the theory of refraction is attributed. Thomas Harriot was also recognized for his con ...

(English, 1560–1621) was a naturalist with the first attempted English colony in North America, on Roanoke Island

Roanoke Island () is an island in Dare County, bordered by the Outer Banks of North Carolina. It was named after the historical Roanoke, a Carolina Algonquian people who inhabited the area in the 16th century at the time of English colonizat ...

, North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

. His ''Brief and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia'' (1590) describes the black bear, gray squirrel, hare, otter

Otters are carnivorous mammals in the subfamily Lutrinae. The 13 extant otter species are all semiaquatic, aquatic, or marine. Lutrinae is a branch of the Mustelidae family, which includes weasels, badgers, mink, and wolverines, among ...

, opossum

Opossums () are members of the marsupial order Didelphimorphia () endemic to the Americas. The largest order of marsupials in the Western Hemisphere, it comprises 126 species in 18 genera. Opossums originated in South America and entered North A ...

, raccoon

The raccoon ( or , ''Procyon lotor''), sometimes called the North American, northern or common raccoon (also spelled racoon) to distinguish it from Procyonina, other species of raccoon, is a mammal native to North America. It is the largest ...

, skunk

Skunks are mammals in the family Mephitidae. They are known for their ability to spray a liquid with a strong, unpleasant scent from their anal glands. Different species of skunk vary in appearance from black-and-white to brown, cream or gi ...

, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

and mule deer

The mule deer (''Odocoileus hemionus'') is a deer indigenous to western North America; it is named for its ears, which are large like those of the mule. Two subspecies of mule deer are grouped into the black-tailed deer.

Unlike the related whit ...

, turkeys, and horseshoe crab

Horseshoe crabs are arthropods of the family Limulidae and the only surviving xiphosurans. Despite their name, they are not true crabs or even crustaceans; they are chelicerates, more closely related to arachnids like spiders, ticks, and scor ...

(''Limulus'').

*1589. José de Acosta (Spanish, 1539–1600) wrote ' (1589) and ' (1590), describing many animals from the New World previously unknown to Europeans.

17th century

*1600. In Italy a spider scare lead to hysteria and thetarantella

Tarantella () is a group of various Southern Italy, southern Italian Italian folk dance, folk dances originating in the regions of Calabria, Campania, Sicilia, and Apulia. It is characterized by a fast Beat (music), upbeat tempo, usually in Ti ...

dance by which the body cures itself through physical exertions.

*1602. Ulisse Aldrovandi

Ulisse Aldrovandi (11 September 1522 – 4 May 1605) was an Italian naturalist, the moving force behind Bologna's botanical garden, one of the first in Europe. Carl Linnaeus and the comte de Buffon reckoned him the father of natural history stud ...

(Italian, 1522–1605) wrote '. This and his other works include many scientific inaccuracies, but he used wing and leg morphology to construct his classification of insects. He is more highly regarded for his ornithological contributions.

*1604–1614. Francisco Hernández de Toledo

Francisco Hernández de Toledo (c. 1515 – 28 January 1587) was a naturalist and court physician to Philip II of Spain. He was among the first wave of Spanish Renaissance physicians practicing according to the revived principles formulated by Hipp ...

(Spanish) was sent to study Mexican biota in 1593–1600, by Philip II of Spain

Philip II (21 May 152713 September 1598), sometimes known in Spain as Philip the Prudent (), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from 1580, and King of Naples and List of Sicilian monarchs, Sicily from 1554 until his death in 1598. He ...

. His notes were published in Mexico in 1604 and 1614, describing many animals to Europeans for the first time: coyote

The coyote (''Canis latrans''), also known as the American jackal, prairie wolf, or brush wolf, is a species of canis, canine native to North America. It is smaller than its close relative, the Wolf, gray wolf, and slightly smaller than the c ...

, buffalo, axolotl

The axolotl (; from ) (''Ambystoma mexicanum'') is a neoteny, paedomorphic salamander, one that Sexual maturity, matures without undergoing metamorphosis into the terrestrial adult form; adults remain Aquatic animal, fully aquatic with obvio ...

, porcupine

Porcupines are large rodents with coats of sharp Spine (zoology), spines, or quills, that protect them against predation. The term covers two Family (biology), families of animals: the Old World porcupines of the family Hystricidae, and the New ...

, pronghorn antelope, horned lizard

''Phrynosoma'', whose members are known as the horned lizards, horny toads, or horntoads, is a genus of North American lizards and the type genus of the Family (biology), family Phrynosomatidae. Their common names refer directly to their horns or ...

, bison

A bison (: bison) is a large bovine in the genus ''Bison'' (from Greek, meaning 'wild ox') within the tribe Bovini. Two extant taxon, extant and numerous extinction, extinct species are recognised.

Of the two surviving species, the American ...

, peccary

Peccaries (also javelinas or skunk pigs) are pig-like ungulates of the family Tayassuidae (New World pigs). They are found throughout Central and South America, Trinidad in the Caribbean, and in the southwestern area of North America. Peccari ...

, and the toucan

Toucans (, ) are Neotropical birds in the family Ramphastidae. They are most closely related to the Semnornis, Toucan barbets. They are brightly marked and have large, often colorful Beak, bills. The family includes five genus, genera and over ...

. He also included figures of many animals for the first time, including the ocelot

The ocelot (''Leopardus pardalis'') is a medium-sized spotted Felidae, wild cat that reaches at the shoulders and weighs between on average. It is native to the southwestern United States, Mexico, Central America, Central and South America, ...

, rattlesnake, manatee, alligator, armadillo, and pelican.

*1607 (1612?). Captain John Smith

John Smith ( – 21 June 1631) was an English soldier, explorer, colonial governor, admiral of New England, and author. He was knighted for his services to Sigismund Báthory, Prince of Transylvania, and his friend Mózes Székely. Followin ...

(English), head of the Jamestown colony, wrote ''A Map of Virginia'' in which he describes the physical features of the country, its climate, plants and animals, and inhabitants. He describes the raccoon, muskrat

The muskrat or common muskrat (''Ondatra zibethicus'') is a medium-sized semiaquatic rodent native to North America and an introduced species in parts of Europe, Asia, and South America.

The muskrat is found in wetlands over various climates ...

, flying squirrel

Flying squirrels (scientifically known as Pteromyini or Petauristini) are a tribe (biology), tribe of 50 species of squirrels in the family (biology), family Squirrel, Sciuridae. Despite their name, they are not in fact capable of full flight i ...

, and other animals.

*1617. Garcilaso de la Vega (Peruvian Spanish, 1539–1617) wrote ''Royal Commentaries of Peru'', containing descriptions of the condor

Condor is the common name for two species of New World vultures, each in a monotypic genus. The name derives from the Quechua language, Quechua ''kuntur''. They are the largest flying land birds in the Western Hemisphere.

One species, the And ...

, ocelot

The ocelot (''Leopardus pardalis'') is a medium-sized spotted Felidae, wild cat that reaches at the shoulders and weighs between on average. It is native to the southwestern United States, Mexico, Central America, Central and South America, ...

s, puma, viscacha

Viscacha or vizcacha (, ) are rodents of two genera ('' Lagidium'' and '' Lagostomus'') in the family Chinchillidae. They are native to South America and convergently resemble rabbits.

The five extant species of viscacha are:

*The Plains vi ...

, tapir

Tapirs ( ) are large, herbivorous mammals belonging to the family Tapiridae. They are similar in shape to a Suidae, pig, with a short, prehensile nose trunk (proboscis). Tapirs inhabit jungle and forest regions of South America, South and Centr ...

, rhea, skunk

Skunks are mammals in the family Mephitidae. They are known for their ability to spray a liquid with a strong, unpleasant scent from their anal glands. Different species of skunk vary in appearance from black-and-white to brown, cream or gi ...

, llama

The llama (; or ) (''Lama glama'') is a domesticated South American camelid, widely used as a List of meat animals, meat and pack animal by Inca empire, Andean cultures since the pre-Columbian era.

Llamas are social animals and live with ...

, huanaco, paca

A paca ia a rodent in South and Central America.

Paca or PACA may also refer to:

People

* William Paca (1740–1799), a Founding Father of the United States

* Paca Blanco (Francisca Blanco Díaz, born 1949), Spanish activist

* Paca Navas (Franc ...

, and vicuña

The vicuña (''Lama vicugna'') or vicuna (both , very rarely spelled ''vicugna'', Vicugna, its former genus name) is one of the two wild South American camelids, which live in the high alpine tundra, alpine areas of the Andes; the other cameli ...

.

*1620? North American colonists probably introduced the European honeybee, ''Apis mellifera

The western honey bee or European honey bee (''Apis mellifera'') is the most common of the 7–12 species of honey bees worldwide. The genus name ''Apis'' is Latin for 'bee', and ''mellifera'' is the Latin for 'honey-bearing' or 'honey-carrying', ...

'', into Virginia. By the 1640s these insects were also in Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

. They became feral and advanced through eastern North America before the settlers.

*1628. William Harvey

William Harvey (1 April 1578 – 3 June 1657) was an English physician who made influential contributions to anatomy and physiology. He was the first known physician to describe completely, and in detail, pulmonary and systemic circulation ...

(English, 1578–1657) published ' (1628) with the doctrine of the circulation of blood (an inference made by him in about 1616).

*1634. William Wood (English) wrote ''New England Prospect'' (1634) in which he describes New England's fauna.

*1637. Thomas Morton (English, c. 1579–1647) wrote ''New English Canaan'' (1637) with treatments of 26 species of mammals, 32 birds, 20 fishes and 8 marine invertebrates.

*1648. Georg Marcgrave (1610–1644) was a German astronomer working for Johann Moritz, Count Maurice of Nassau, in the Dutch colony set up in northeastern

*1648. Georg Marcgrave (1610–1644) was a German astronomer working for Johann Moritz, Count Maurice of Nassau, in the Dutch colony set up in northeastern Brazil

Brazil, officially the Federative Republic of Brazil, is the largest country in South America. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by area, fifth-largest country by area and the List of countries and dependencies by population ...

. His ' (1648) contains the best early descriptions of many Brazilian animals. Marcgrave used Tupi names that were later Latinized by Linnaeus in the 13th edition of the ''Systema Naturae