Thomas Sturge on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thomas Sturge (1787–1866) was a British

Thomas Sturge junior had become the senior partner in the business by 1816, when he began to buy ships and send them to the Southern Whale Fishery to obtain

Thomas Sturge junior had become the senior partner in the business by 1816, when he began to buy ships and send them to the Southern Whale Fishery to obtain

In 1838 Sturge joined a group of London shipowners to purchase two vessels, the schooner ''Eliza Scott'' (154 tons) and the cutter ''Sabrina'' (54 tons). These were sent to the

In 1838 Sturge joined a group of London shipowners to purchase two vessels, the schooner ''Eliza Scott'' (154 tons) and the cutter ''Sabrina'' (54 tons). These were sent to the

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Struge, Thomas 1787 births 1866 deaths 19th-century British philanthropists 19th-century English businesspeople British people in whaling British railway pioneers Cement Companies based in the London Borough of Southwark British abolitionists English philanthropists English Quakers Exploration of Antarctica People from Southwark Quaker abolitionists Sealers Whaling firms Whaling in the United Kingdom

oil

An oil is any nonpolar chemical substance that is composed primarily of hydrocarbons and is hydrophobic (does not mix with water) and lipophilic (mixes with other oils). Oils are usually flammable and surface active. Most oils are unsaturate ...

merchant, shipowner

A shipowner, ship owner or ship-owner is the owner of a ship. They can be merchant vessels involved in the shipping industry or non commercially owned. In the commercial sense of the term, a shipowner is someone who equips and exploits a ship, us ...

, cement manufacturer, railway company director, social reformer and philanthropist

Philanthropy is a form of altruism that consists of "private initiatives for the public good, focusing on quality of life". Philanthropy contrasts with business initiatives, which are private initiatives for private good, focusing on material ...

.

Family background and early life

Thomas Sturge was born in 1787, one of at least ten children ofThomas Sturge the elder

Thomas Sturge the Elder (1749 – 11 August 1825) was a London tallow chandler, oil merchant, spermaceti processor and philanthropist. He was a Quaker.

Business career

Sturge was born into a farming family at Olveston, Gloucestershire, in 1749 ...

(1749–1825), tallow

Tallow is a rendered form of beef or mutton suet, primarily made up of triglycerides.

In industry, tallow is not strictly defined as beef or mutton suet. In this context, tallow is animal fat that conforms to certain technical criteria, inc ...

chandler and oil merchant of Newington Butts

Newington Butts is a former hamlet, now an area of the London Borough of Southwark, London, England, that gives its name to a segment of the A3 road running south-west from the Elephant and Castle junction. The road continues as Kennington Park ...

, about a mile south of London Bridge

The name "London Bridge" refers to several historic crossings that have spanned the River Thames between the City of London and Southwark in central London since Roman Britain, Roman times. The current crossing, which opened to traffic in 197 ...

. Thomas the younger joined his father's business early in the 19th century, as did at least three of his brothers, Nathan, George and Samuel. Thomas Sturge & Sons, oil merchants and spermaceti

Spermaceti (see also: Sperm oil) is a waxy substance found in the head cavities of the sperm whale (and, in smaller quantities, in the oils of other whales). Spermaceti is created in the spermaceti organ inside the whale's head. This organ may ...

processors operated from premises near Elephant and Castle

Elephant and Castle is an area of South London, England, in the London Borough of Southwark. The name also informally refers to much of Walworth and Newington, due to the proximity of the London Underground station of the same name. The n ...

, Newington Butts, until 1840.

He was a first cousin of social reformer and philanthropist Joseph Sturge

Joseph Sturge (2 August 1793 – 14 May 1859) was an English Quaker, abolitionist and activist. He founded the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society (now Anti-Slavery International). He worked throughout his life in Radical political actions ...

.

Oil merchant and shipowner

Thomas Sturge junior had become the senior partner in the business by 1816, when he began to buy ships and send them to the Southern Whale Fishery to obtain

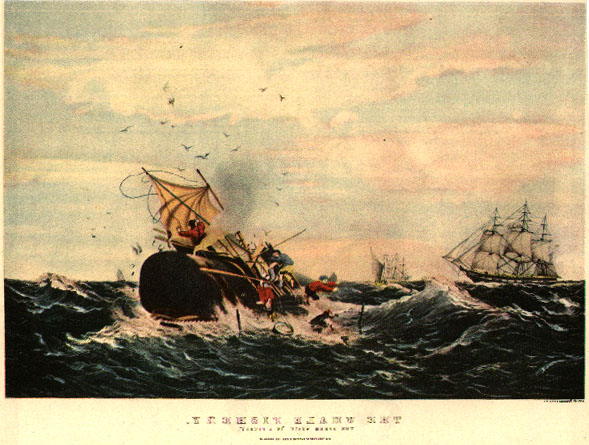

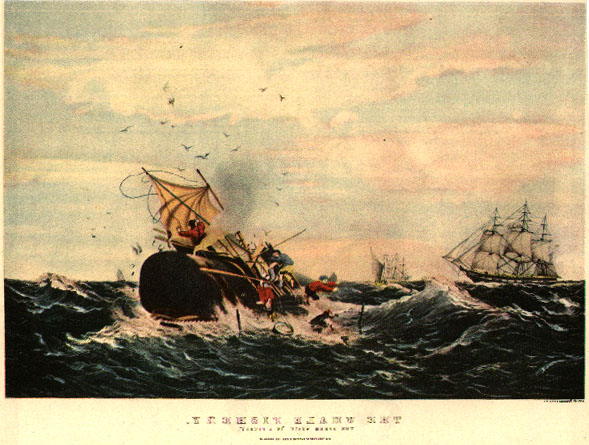

Thomas Sturge junior had become the senior partner in the business by 1816, when he began to buy ships and send them to the Southern Whale Fishery to obtain whale oil

Whale oil is oil obtained from the blubber of whales. Oil from the bowhead whale was sometimes known as train-oil, which comes from the Dutch word ''traan'' ("tear drop").

Sperm oil, a special kind of oil used in the cavities of sperm whales, ...

, seal oil and spermaceti

Spermaceti (see also: Sperm oil) is a waxy substance found in the head cavities of the sperm whale (and, in smaller quantities, in the oils of other whales). Spermaceti is created in the spermaceti organ inside the whale's head. This organ may ...

for processing and sale in London. He became the principal owner of at least 23 vessels, most of them South Sea whalers.

His Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally, others referred to them as Quakers ...

faith and values were reflected in his business dealings. He tried to choose committed Christians to command his whale ships and in his sailing instructions gave his captains detailed advice on how to treat their crewmen. His vessels each seem to have been supplied with a small library and at least five of his vessels carried a "surgeon" or ship's doctor. One of these was Dr Thomas Beale who later wrote, ''The Natural History of the Sperm Whale'' (1839), which he dedicated to his employer. Herman Melville drew on the book for his novel ''Moby Dick'' (1851). The book also inspired three paintings of whaling scenes by J. M. W. Turner

Joseph Mallord William Turner (23 April 177519 December 1851), known in his time as William Turner, was an English Romantic painter, printmaker and watercolourist. He is known for his expressive colouring, imaginative landscapes and turbu ...

, exhibited at the Royal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is an art institution based in Burlington House in Piccadilly London, England. Founded in 1768, it has a unique position as an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects. Its ...

in 1845 and 1846. Turner tried to sell them to his patron, oil merchant, shipowner and art collector Elhanan Bicknell. Bicknell was an associate and friend of Sturge at Newington Butts.

Social reformer and philanthropist

Sturge was a member of a committee to assist “distressed seaman” by 1818. His firm donated £15 15 shillings in 1821 toward the cost of a suitable vessel to serve as a floating hospital for the “assistance and relief of sick and helpless seamen.” TheSeamen's Hospital Society

The Seafarers Hospital Society, formerly the Seamen's Hospital Society, is a charitable trust, charity for people currently or previously employed by the British Merchant Navy and Fishing industry in England, fishing fleets, and their families. ...

was established that year, with William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce (24 August 1759 – 29 July 1833) was a British politician, philanthropist, and a leader of the movement to abolish the Atlantic slave trade. A native of Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire, he began his political career in 1780 ...

as one of the many vice presidents; Sturge was one of a couple of dozen men on its management committee, along with Zachary Macaulay

Zachary Macaulay (; 2 May 1768 – 13 May 1838) was a Scottish statistician and abolitionist who was a founder of London University and of the Society for the Suppression of Vice, and a Governor of British Sierra Leone.

Early life

Macaulay wa ...

and Captain William Young.

He was a member of the Anti-Slavery Society Anti-Slavery Society was a name used by various abolitionist groups including:

United Kingdom

* Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade (1787–1807?), also referred to as the Abolition Society

* Anti-Slavery Society (1823–1838) ...

and substantial financial contributor to the cause. Another member of the society was the historian and politician Thomas Babington Macaulay

Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay, (; 25 October 1800 – 28 December 1859) was an English historian, poet, and Whig politician, who served as the Secretary at War between 1839 and 1841, and as the Paymaster General between 184 ...

(1800–1859) who became friends with Sturge. There were many Quakers in the abolition movement

The Religious Society of Friends, better known as the Quakers, played a major role in the Abolitionism, abolition movement against slavery in both the United Kingdom and in the United States. Quakers were among the first white people to denounce ...

. Among these was his cousin the prominent anti-slavery

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was France in 1315, but it was later used in its colonies. T ...

abolitionist and philanthropist Joseph Sturge

Joseph Sturge (2 August 1793 – 14 May 1859) was an English Quaker, abolitionist and activist. He founded the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society (now Anti-Slavery International). He worked throughout his life in Radical political actions ...

(1793–1859).

Thomas also made regular donations to a range of other charitable causes. He provided transport to missionaries going to the South Seas

Today the term South Seas, or South Sea, most commonly refers to the portion of the Pacific Ocean south of the equator. The term South Sea may also be used synonymously for Oceania, or even more narrowly for Polynesia or the Polynesian Triangle ...

on his whaling ships. Robert Moffat and his wife left their children in the care of Sturge and his invalid sister when they were in South Africa in the 1860s. Thomas or his father, Thomas senior, was supporting the education of the deaf

Deaf education is the education of students with any degree of hearing loss, hearing loss or deafness. This may involve, but does not always, individually-planned, systematically-monitored teaching methods, adaptive materials, accessible settin ...

by May 1821.

Contributor to Antarctic exploration

In 1838 Sturge joined a group of London shipowners to purchase two vessels, the schooner ''Eliza Scott'' (154 tons) and the cutter ''Sabrina'' (54 tons). These were sent to the

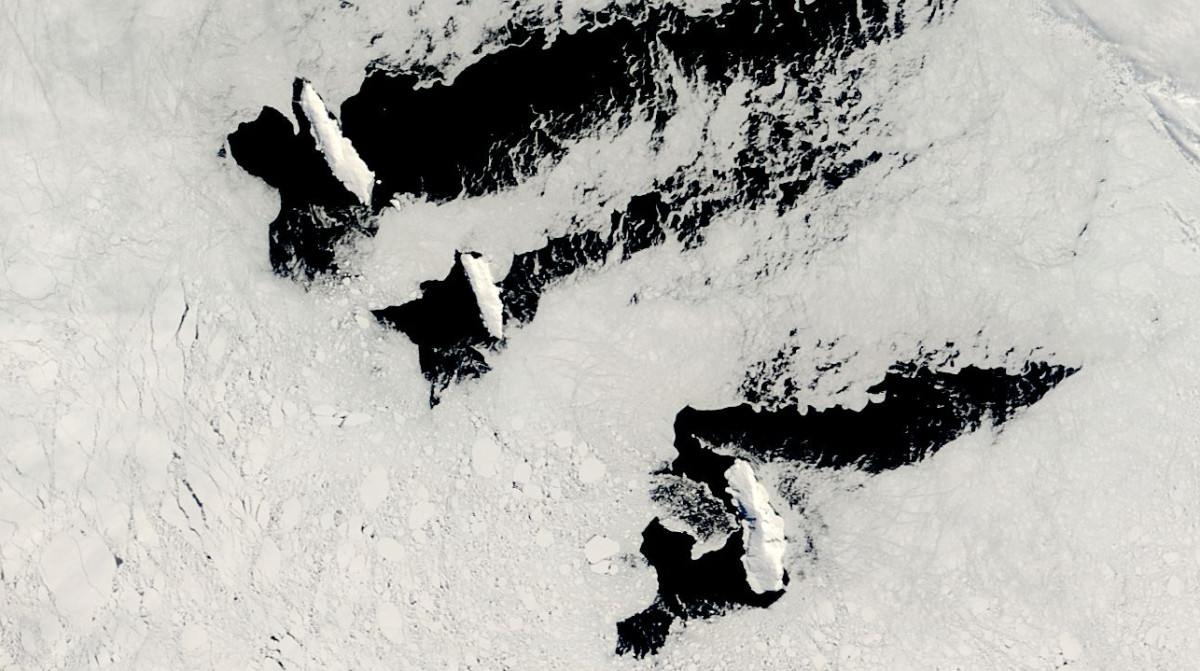

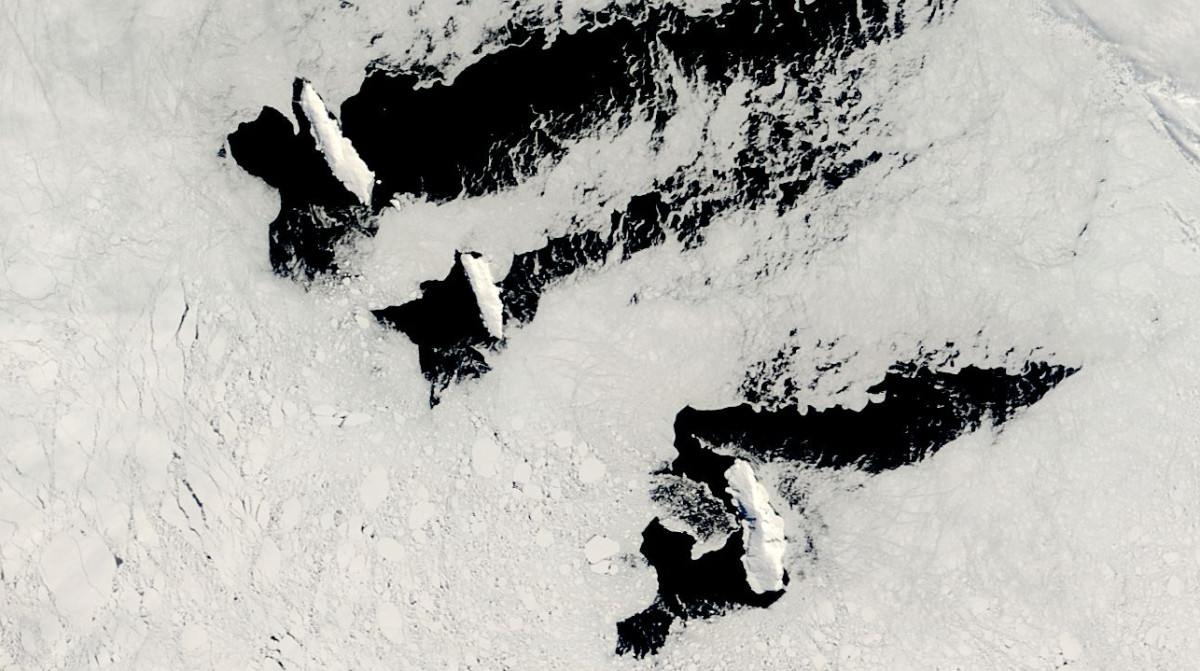

In 1838 Sturge joined a group of London shipowners to purchase two vessels, the schooner ''Eliza Scott'' (154 tons) and the cutter ''Sabrina'' (54 tons). These were sent to the Antarctic

The Antarctic (, ; commonly ) is the polar regions of Earth, polar region of Earth that surrounds the South Pole, lying within the Antarctic Circle. It is antipodes, diametrically opposite of the Arctic region around the North Pole.

The Antar ...

, under the overall command of Captain John Balleny

John Balleny ( 1857) was the English captain of the sealing schooner , who led an exploration cruise for the English whaling firm Samuel Enderby & Sons to the Antarctic in 1838–1839. During the expedition of 1838–1839, Balleny, sailing in comp ...

, to search for undiscovered offshore islands that might host seal colonies that could be harvested. Among the discoveries made was a cluster of five previously unknown islands. They were given the collective name of the Balleny Islands

The Balleny Islands () are a series of uninhabited islands in the Southern Ocean extending from 66°15' to 67°35'S and 162°30' to 165°00'E. The group extends for about in a northwest–southeast direction. The islands are heavily glaciate ...

with individual islands named after those who had funded the expedition. Sturge Island

Sturge Island is one of the three main islands in the uninhabited Balleny Islands group located in the Southern Ocean. It lies southeast of Buckle Island and north-east of Belousov Point on the Antarctic mainland. The island, in Oates Land, al ...

is 23 miles long and 6 miles wide and permanently covered in a mantle of snow and ice.

Cement producer

In 1837 and 1838 he purchased two adjacent blocks of land on the Thames nearNorthfleet

Northfleet is a town in the borough of Gravesham in Kent, England. It is located immediately west of Gravesend, and on the border with the Borough of Dartford. Northfleet has its own railway station on the North Kent Line, just east of Ebbsf ...

at a cost of £9,313. On that 74-acre plot he built a cement

A cement is a binder, a chemical substance used for construction that sets, hardens, and adheres to other materials to bind them together. Cement is seldom used on its own, but rather to bind sand and gravel ( aggregate) together. Cement mi ...

works to make Portland cement

Portland cement is the most common type of cement in general use around the world as a basic ingredient of concrete, mortar (masonry), mortar, stucco, and non-specialty grout. It was developed from other types of hydraulic lime in England in th ...

. Construction of the cement kiln

Cement kilns are used for the pyroprocessing stage of manufacture of Portland cement, portland and other types of hydraulic cement, in which calcium carbonate reacts with silicon dioxide, silica-bearing minerals to form a mixture of calcium silic ...

s started in 1851 and production began in 1853.

Railway investments

He was interested in the building of new railways and in 1842 he spoke at a public meeting in favour of the construction of the Dean Forest and Gloucester railway line. He became a significant shareholder in theEastern Union Railway

The Eastern Union Railway (EUR) was an English railway company, at first built from Colchester to Ipswich; it opened in 1846. It was proposed when the earlier Eastern Counties Railway failed to make its promised line from Colchester to Norwich. T ...

Company and a major shareholder and director of the West Hartlepool

West Hartlepool was a predecessor of Hartlepool, County Durham, England. It developed in the Victorian era and took the name from its western position in the parish of what is now known as the Headland.

The former town was originally formed ...

Harbour and Railway Company.

Later life

In 1842 he left London and moved downriver toNorthfleet

Northfleet is a town in the borough of Gravesham in Kent, England. It is located immediately west of Gravesend, and on the border with the Borough of Dartford. Northfleet has its own railway station on the North Kent Line, just east of Ebbsf ...

, where he had purchased Northfleet House, a mansion under construction, for £3,900. Thomas Sturge the younger died there on 14 April 1866. He never married and most of his estate, valued at about £180,000 (£17,729,000 in 2023 values), was left to his brother and business partner, George.A.J. Francis, ''The cement industry, 1796-1914: a history'', Newton Abbott, 1978, p.165.

Notes

Further reading

* ''British Southern Whale Fishery'', web site, http://www.britishwhaling.org/ * Howard, Mark, “Thomas Sturge and his fleet of South Sea whalers,” ''International Journal of Maritime History'', 27 (3) August 2015, 411–43* {{DEFAULTSORT:Struge, Thomas 1787 births 1866 deaths 19th-century British philanthropists 19th-century English businesspeople British people in whaling British railway pioneers Cement Companies based in the London Borough of Southwark British abolitionists English philanthropists English Quakers Exploration of Antarctica People from Southwark Quaker abolitionists Sealers Whaling firms Whaling in the United Kingdom