Thomas Sankara on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thomas Isidore Noël Sankara (; 21 December 1949 – 15 October 1987) was a Burkinabè military officer,

Thomas Sankara was born Thomas Isidore Noël Sankara on 21 December 1949 in Yako, French Upper Volta, as the third of ten children to Joseph and Marguerite Sankara. His father, Joseph Sankara, a

Thomas Sankara was born Thomas Isidore Noël Sankara on 21 December 1949 in Yako, French Upper Volta, as the third of ten children to Joseph and Marguerite Sankara. His father, Joseph Sankara, a

Accompanying his personal charisma, Sankara had an array of original initiatives that contributed to his popularity and brought some international media attention to his government.

Accompanying his personal charisma, Sankara had an array of original initiatives that contributed to his popularity and brought some international media attention to his government.

''Burkina Faso's Pure President''

by Bruno Jaffré.

''Thomas Sankara Lives!''

by Mukoma Wa Ngugi.

''There Are Seven Million Sankaras''

by Koni Benson.

''Thomas Sankara: "I have a Dream"''

by Federico Bastiani.

''Thomas Sankara: Chronicle of an Organised Tragedy''

by Cheriff M. Sy.

''Thomas Sankara Former Leader of Burkina Faso''

by Désiré-Joseph Katihabwa.

''Thomas Sankara 20 Years Later: A Tribute to Integrity''

by Demba Moussa Dembélé.

Remembering Thomas Sankara

Rebecca Davis, ''The Daily Maverick'', 2013.

"I can hear the roar of women's silence"

Sokarie Ekine, ''Red Pepper'', 2012.

''Thomas Sankara: A View of The Future for Africa and The Third World''

by Ameth Lo.

''Thomas Sankara on the Emancipation of Women, An internationalist whose ideas live on!''

by Nathi Mthethwa.

''Thomas Sankara, le Che africain''

by Pierre Venuat (in French).

''Thomas Sankara e la rivoluzione interrotta''

by Enrico Palumbo (in Italian).

ThomasSankara.net

a website dedicated to Thomas Sankara * {{DEFAULTSORT:Sankara, Thomas * 1949 births 1987 deaths 1987 murders in Africa African Marxists African politicians assassinated in the 1980s Anti-French sentiment Anti-imperialists Assassinated Burkinabe politicians Assassinated heads of state in Africa Assassinated revolutionaries Burkinabe communists Burkinabe military personnel Burkinabe nationalists Burkinabe pan-Africanists Burkinabe revolutionaries Burkinabe Roman Catholics Heads of state of Burkina Faso Leaders ousted by a coup Leaders who took power by coup Male feminists Marxist theorists National anthem writers People from Nord Region (Burkina Faso) People from Sud-Ouest Region (Burkina Faso) People murdered in Burkina Faso Politicians assassinated in 1987 Prime ministers of Burkina Faso

Marxist

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflic ...

and Pan-Africanist revolutionary who served as the President of Burkina Faso from 1983, following his takeover in a coup, until his assassination in 1987.

After being appointed Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

in 1983, disputes with the sitting government resulted in Sankara's eventual imprisonment. While he was under house arrest

House arrest (also called home confinement, or nowadays electronic monitoring) is a legal measure where a person is required to remain at their residence under supervision, typically as an alternative to imprisonment. The person is confined b ...

, a group of revolutionaries

A revolutionary is a person who either participates in, or advocates for, a revolution. The term ''revolutionary'' can also be used as an adjective to describe something producing a major and sudden impact on society.

Definition

The term—bot ...

seized power on his behalf in a popularly supported coup later that year.

At the age of 33, Sankara became the President of the Republic of Upper Volta

The Republic of Upper Volta () was a landlocked West African country established on 11 December 1958 as a self-governing state within the French Community. Before becoming autonomous, it had been part of the French Union as the French Upper V ...

and launched an unprecedented series of social, ecological, and economic reforms. In 1984, Sankara oversaw the renaming of the country as Burkina Faso

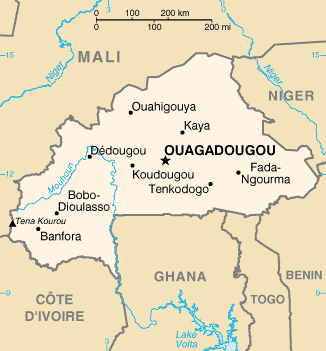

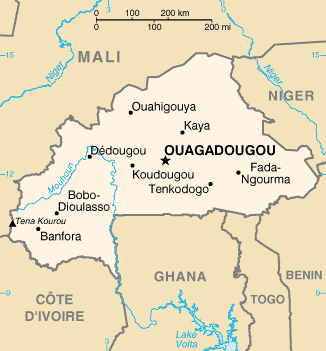

Burkina Faso is a landlocked country in West Africa, bordered by Mali to the northwest, Niger to the northeast, Benin to the southeast, Togo and Ghana to the south, and Ivory Coast to the southwest. It covers an area of 274,223 km2 (105,87 ...

('land of the upright people'), and personally wrote its national anthem. His foreign policy was centered on anti-imperialism

Anti-imperialism in political science and international relations is opposition to imperialism or neocolonialism. Anti-imperialist sentiment typically manifests as a political principle in independence struggles against intervention or influen ...

and he rejected loans and capital from organizations such as the International Monetary Fund

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is a major financial agency of the United Nations, and an international financial institution funded by 191 member countries, with headquarters in Washington, D.C. It is regarded as the global lender of las ...

. However, he welcomed some foreign aid in an effort to boost the domestic economy, diversify the sources of assistance, and make Burkina Faso self-sufficient.

His domestic policies included famine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food caused by several possible factors, including, but not limited to war, natural disasters, crop failure, widespread poverty, an Financial crisis, economic catastrophe or government policies. This phenom ...

prevention, agrarian expansion, land reform

Land reform (also known as agrarian reform) involves the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership, land use, and land transfers. The reforms may be initiated by governments, by interested groups, or by revolution.

Lan ...

, and suspending rural poll tax

A poll tax, also known as head tax or capitation, is a tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual (typically every adult), without reference to income or resources. ''Poll'' is an archaic term for "head" or "top of the head". The sen ...

es, as well as a nationwide literacy campaign and vaccination

Vaccination is the administration of a vaccine to help the immune system develop immunity from a disease. Vaccines contain a microorganism or virus in a weakened, live or killed state, or proteins or toxins from the organism. In stimulating ...

program to reduce meningitis

Meningitis is acute or chronic inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, collectively called the meninges. The most common symptoms are fever, intense headache, vomiting and neck stiffness and occasion ...

, yellow fever and measles

Measles (probably from Middle Dutch or Middle High German ''masel(e)'', meaning "blemish, blood blister") is a highly contagious, Vaccine-preventable diseases, vaccine-preventable infectious disease caused by Measles morbillivirus, measles v ...

. Sankara's health programmes distributed millions of doses of vaccines to children across Burkina Faso. His government also focused on building schools, health centres, water reservoirs, and infrastructure projects. He combatted desertification

Desertification is a type of gradual land degradation of Soil fertility, fertile land into arid desert due to a combination of natural processes and human activities.

The immediate cause of desertification is the loss of most vegetation. This i ...

of the Sahel

The Sahel region (; ), or Sahelian acacia savanna, is a Biogeography, biogeographical region in Africa. It is the Ecotone, transition zone between the more humid Sudanian savannas to its south and the drier Sahara to the north. The Sahel has a ...

by planting more than 10 million trees. Socially, his government enforced the prohibition of female circumcision, forced marriage

Forced marriage is a marriage in which one or more of the parties is married without their consent or against their will. A marriage can also become a forced marriage even if both parties enter with full consent if one or both are later force ...

s and polygamy

Polygamy (from Late Greek , "state of marriage to many spouses") is the practice of marriage, marrying multiple spouses. When a man is married to more than one wife at the same time, it is called polygyny. When a woman is married to more tha ...

. Sankara reinforced his populist image by ordering the sale of luxury vehicles and properties owned by the government in order to reduce costs. In addition, he banned what he considered the luxury of air conditioning

Air conditioning, often abbreviated as A/C (US) or air con (UK), is the process of removing heat from an enclosed space to achieve a more comfortable interior temperature, and in some cases, also controlling the humidity of internal air. Air c ...

in government offices, and homes of politicians. He established Cuban-inspired Committees for the Defense of the Revolution to serve as a new foundation of society and promote popular mobilization. His Popular Revolutionary Tribunals prosecuted public officials charged with graft, political crimes and corruption, considering such elements of the state counter-revolutionaries. This led to criticism by Amnesty International

Amnesty International (also referred to as Amnesty or AI) is an international non-governmental organization focused on human rights, with its headquarters in the United Kingdom. The organization says that it has more than ten million members a ...

for alleged human rights violations, such as arbitrary detentions of political opponents.

Sankara's revolutionary programmes and reforms for African self-reliance made him an icon to many of Africa's poverty-stricken nations, and the president remained popular with a substantial majority of his country's citizens, as well as those outside Burkina Faso. Some of his policies alienated elements of the former ruling class, including tribal leaders — and the governments of France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

and its ally the Ivory Coast

Ivory Coast, also known as Côte d'Ivoire and officially the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire, is a country on the southern coast of West Africa. Its capital city of Yamoussoukro is located in the centre of the country, while its largest List of ci ...

.

On 15 October 1987, Sankara was assassinated by troops led by Blaise Compaoré, who assumed leadership of the country shortly thereafter. Compaoré retained power until the 2014 Burkina Faso uprising. In 2021, he was formally charged with and found guilty for the murder of Sankara by a military tribunal.

Early life

Thomas Sankara was born Thomas Isidore Noël Sankara on 21 December 1949 in Yako, French Upper Volta, as the third of ten children to Joseph and Marguerite Sankara. His father, Joseph Sankara, a

Thomas Sankara was born Thomas Isidore Noël Sankara on 21 December 1949 in Yako, French Upper Volta, as the third of ten children to Joseph and Marguerite Sankara. His father, Joseph Sankara, a gendarme

A gendarmerie () is a paramilitary or military force with law enforcement duties among the civilian population. The term ''gendarme'' () is derived from the medieval French expression ', which translates to "men-at-arms" (). In France and som ...

, was of Silmi–Mossi heritage, while his mother, Marguerite Kinda, was of direct Mossi descent. He spent his early years in Gaoua, a town in the humid southwest to which his father was transferred as an auxiliary gendarme. As the son of one of the few African functionaries then employed by the colonial state, he enjoyed a relatively privileged position. The family lived in a brick house with the families of other gendarmes at the top of a hill overlooking the rest of Gaoua.

Sankara attended primary school at Bobo-Dioulasso

Bobo-Dioulasso ( , ) is a city in Burkina Faso with a population of 1,129,000 (); it is the second-largest city in the country, after Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso's capital. The name means "home of the Bobo- Dioula".

The local Bobo-speaking pop ...

. He applied himself seriously to his schoolwork and excelled in mathematics and French. He went to church often and, impressed with his energy and eagerness to learn, some of the priests encouraged Thomas to go on to seminary

A seminary, school of theology, theological college, or divinity school is an educational institution for educating students (sometimes called seminarians) in scripture and theology, generally to prepare them for ordination to serve as cle ...

school once he finished primary school. Despite initially agreeing, he took the exam required for entry to the sixth grade in the secular educational system and passed. Thomas's decision to continue with his education at the nearest lycée, Ouezzin Coulibaly (named after a pre-independence nationalist

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation,Anthony D. Smith, Smith, A ...

), proved to be a turning point. He left his father's household to attend the lycée in Bobo-Dioulasso

Bobo-Dioulasso ( , ) is a city in Burkina Faso with a population of 1,129,000 (); it is the second-largest city in the country, after Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso's capital. The name means "home of the Bobo- Dioula".

The local Bobo-speaking pop ...

, the country's commercial centre. There Sankara made close friends, including Fidèle Too, whom he later named a minister in his government; and Soumane Touré, who was in a more advanced class.

His Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

parents wanted him to become a priest, but he chose to enter the military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. Militaries are typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with their members identifiable by a d ...

. The military was popular at the time, having just ousted Maurice Yaméogo, an unpopular president. Many young intellectuals viewed it as a national institution that might potentially help to discipline the inefficient and corrupt bureaucracy, counterbalance the inordinate influence of traditional chiefs, and generally help modernize the country. Acceptance into the military academy was accompanied by a scholarship; Sankara could not easily afford the costs of further education otherwise. He took the entrance exam and passed.

He entered the military academy of Kadiogo in Ouagadougou

Ouagadougou or Wagadugu (, , , ) is the capital city of Burkina Faso, and the administrative, communications, cultural and economic centre of the nation. It is also the List of cities in Burkina Faso#Largest cities, country's largest city, wi ...

with the academy's first intake of 1966 at the age of 17. While there he witnessed the first military coup d'état in Upper Volta led by Lieutenant-Colonel Sangoulé Lamizana (3 January 1966). The trainee officers were taught by civilian professors in the social sciences. Adama Touré, who taught history and geography, was the academic director at the time and known for having progressive ideas, although he did not publicly share them. He invited a few of his brightest and more political students, among them Sankara, to join informal discussions outside the classroom about imperialism

Imperialism is the maintaining and extending of Power (international relations), power over foreign nations, particularly through expansionism, employing both hard power (military and economic power) and soft power (diplomatic power and cultura ...

, neocolonialism

Neocolonialism is the control by a state (usually, a former colonial power) over another nominally independent state (usually, a former colony) through indirect means. The term ''neocolonialism'' was first used after World War II to refer to ...

, socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

and communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

, the Soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

and Chinese revolutions, the liberation movements in Africa, and similar topics. This was the first time Sankara was systematically exposed to a revolutionary perspective on Upper Volta and the world. Aside from his academic and extracurricular political activities, Sankara also pursued his passion for music and played the guitar.

In 1970, 20-year-old Sankara went for further military studies at the military academy of Antsirabe

Antsirabe () also known as Ville d'eau is the list of cities in Madagascar, third largest city in Madagascar and the capital of the Vakinankaratra region, with a population of 265,018 in 2014.

In Madagascar, Antsirabe is known for its relatively ...

in Madagascar

Madagascar, officially the Republic of Madagascar, is an island country that includes the island of Madagascar and numerous smaller peripheral islands. Lying off the southeastern coast of Africa, it is the world's List of islands by area, f ...

, from which he graduated as a junior officer in 1973. At the Antsirabe academy, the range of instruction went beyond standard military subjects, which allowed Sankara to study agriculture

Agriculture encompasses crop and livestock production, aquaculture, and forestry for food and non-food products. Agriculture was a key factor in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created ...

, including how to raise crop yields and better the lives of farmers. He took up these issues in his own administration and country. During that period, he read profusely on history and military strategy, thus acquiring the concepts and analytical tools that he would later use in his reinterpretation of Burkinabe political history. He was also influenced by French leftist professors in Madagascar. Their intellectual influence on him was later superceded by that of Samir Amin

Samir Amin () (3 September 1931 – 12 August 2018) was an Egyptian-French Marxian economics, Marxian economist, political scientist and World-systems theory, world-systems analyst. He is noted for his introduction of the term Eurocentrism in 19 ...

, whose concepts of auto-centered development and delinking from the global capitalist economy influenced him deeply (they were personal friends as well). Thomas Sankara's own speeches and works show also that his analytical strengths went beyond merely applying Cuban solutions, or Amin's ideas. Beyond Marxism, he drew also from religious sources (both the Bible and the Quran were among his favourite readings). His focus on the peasantry, developed independently from both Amin and Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; traditionally Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Mao Tse-tung. (26December 18939September 1976) was a Chinese politician, revolutionary, and political theorist who founded the People's Republic of China (PRC) in ...

, was especially important and influenced many in both Burkina Faso and later other African countries.

Military career

After his basic military training in secondary school in 1966, Sankara began his military career at the age of 19. A year later he was sent to Madagascar for officer training atAntsirabe

Antsirabe () also known as Ville d'eau is the list of cities in Madagascar, third largest city in Madagascar and the capital of the Vakinankaratra region, with a population of 265,018 in 2014.

In Madagascar, Antsirabe is known for its relatively ...

, where he witnessed popular uprisings in 1971 and 1972 against the government of Philibert Tsiranana

Philibert Tsiranana (18 October 1912 – 16 April 1978) was a Malagasy politician and leader who served as the seventh prime minister of Madagascar from 1958 to 1959, and then later the first president of Madagascar from 1959 to 1972.

Duri ...

. During this period he first read the works of Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

and Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

, which profoundly influenced his political views for the rest of his life.

Returning to Upper Volta in 1972, he fought in a border war between Upper Volta and Mali by 1974. He earned fame for his performance in the conflict, but years later would renounce the fighting as 'useless and unjust', a reflection of his growing political consciousness. He also became a popular figure in the capital of Ouagadougou

Ouagadougou or Wagadugu (, , , ) is the capital city of Burkina Faso, and the administrative, communications, cultural and economic centre of the nation. It is also the List of cities in Burkina Faso#Largest cities, country's largest city, wi ...

. Sankara was a decent guitarist. He played in a band named Tout-à-Coup Jazz and rode a bicycle.

In 1976 he became commander of the Commando Training Centre in Pô. During the presidency of Colonel Saye Zerbo, a group of young officers formed a secret organization called '' ROC'', the best-known members being Henri Zongo, Jean-Baptiste Boukary Lingani, Blaise Compaoré and Sankara.

Government posts

Sankara was appointed Minister of Information in Saye Zerbo's military government in September 1981. Sankara differentiated himself from other government officials in many ways such as biking to work everyday, instead of driving in a car. While his predecessors would censor journalists and newspapers, Sankara encouraged investigative journalism and allowed the media to print whatever it found. This led to publications of government scandals by both privately owned and state-owned newspapers. He resigned on 12 April 1982 in opposition to what he saw as the regime's anti-labour drift, declaring 'Misfortune to those who gag the people!' (). After another coup (7 November 1982) brought to power Major-Doctor Jean-Baptiste Ouédraogo, Sankara became Prime Minister in January 1983. But he was dismissed a few months later, on 17 May. During those four months, Sankara pushed Ouédraogo's regime for more progressive reforms. Sankara was arrested after the French President's African affairs adviser, , met with Col. Yorian Somé. Henri Zongo and Jean-Baptiste Boukary Lingani were also placed under arrest. The decision to arrest Sankara proved to be very unpopular with the younger officers in the military regime. His imprisonment created enough momentum for his friend Blaise Compaoré to lead another coup.Presidency

Acoup d'état

A coup d'état (; ; ), or simply a coup

, is typically an illegal and overt attempt by a military organization or other government elites to unseat an incumbent leadership. A self-coup is said to take place when a leader, having come to powe ...

organized by Blaise Compaoré made Sankara President on 4 August 1983 at the age of 33. The coup d'état was supported by Libya

Libya, officially the State of Libya, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya border, the east, Sudan to Libya–Sudan border, the southeast, Chad to Chad–L ...

, which was at the time on the verge of war with France in Chad

Chad, officially the Republic of Chad, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of North Africa, North and Central Africa. It is bordered by Libya to Chad–Libya border, the north, Sudan to Chad–Sudan border, the east, the Central Afric ...

(see history of Chad).

Sankara identified as a revolutionary and was inspired by the examples of Cuba's Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban politician and revolutionary who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and President of Cuba, president ...

and Che Guevara

Ernesto "Che" Guevara (14th May 1928 – 9 October 1967) was an Argentines, Argentine Communist revolution, Marxist revolutionary, physician, author, Guerrilla warfare, guerrilla leader, diplomat, and Military theory, military theorist. A majo ...

, and Ghana's military leader Jerry Rawlings

Jerry John Rawlings (born Jerry Rawlings John; 22 June 194712 November 2020) was a Ghanaian military officer, aviator, and politician who led the country briefly in 1979 and then from 1981 to 2001. He led a military junta until 1993 and then se ...

. As President, he promoted the 'Democratic and Popular Revolution' (, or RDP). The ideology of the Revolution was defined by Sankara as anti-imperialist

Anti-imperialism in political science and international relations is opposition to imperialism or neocolonialism. Anti-imperialist sentiment typically manifests as a political principle in independence struggles against intervention or influenc ...

in a speech on 2 October 1983, the (DOP), written by his close associate Valère Somé. His policy was oriented toward fighting corruption and promoting reforestation.

On 4 August 1984, the first anniversary of his accession, he renamed the country Burkina Faso, meaning 'the land of upright people' in Mooré and Dyula, the two major languages of the country. He also gave it a new flag and wrote a new national anthem ('' Ditanyè'').

Council of the Revolution

When Sankara assumed power on 4 August, he named the leadership of the country the Council of the Revolution (CNR). This was a way for Sankara to signal that he was going to try for political and social change. The CNR composed of both civilians and soldiers, all ordinary people. But the member count was secret for security reasons and known only to Sankara and others in his inner circle. The CNR regularly met to talk about important plans and decisions for the country. They helped give advice and direction to the government's actions. They voted on suggestions and decisions from governments officials; the decision making wascollective

A collective is a group of entities that share or are motivated by at least one common issue or interest or work together to achieve a common objective. Collectives can differ from cooperatives in that they are not necessarily focused upon an e ...

. On some occasions, they overruled even proposals favoured personally by Sankara.

Healthcare and public works

Sankara's first priorities after taking office were feeding, housing, and providing medical care to his people who desperately needed it. He launched a mass vaccination program aimed at eradicatingpolio

Poliomyelitis ( ), commonly shortened to polio, is an infectious disease caused by the poliovirus. Approximately 75% of cases are asymptomatic; mild symptoms which can occur include sore throat and fever; in a proportion of cases more severe ...

, meningitis

Meningitis is acute or chronic inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, collectively called the meninges. The most common symptoms are fever, intense headache, vomiting and neck stiffness and occasion ...

, and measles

Measles (probably from Middle Dutch or Middle High German ''masel(e)'', meaning "blemish, blood blister") is a highly contagious, Vaccine-preventable diseases, vaccine-preventable infectious disease caused by Measles morbillivirus, measles v ...

. From 1983 to 1985, 2 million Burkinabé were vaccinated, significantly improving public health outcomes.

Prior to Sankara's presidency, the infant mortality rate in Burkina Faso was about 20.8%. During his time in office, it fell to 14.5%, highlighting the effectiveness of his health initiatives. His administration was also the first African government to publicly recognize the AIDS epidemic

The global pandemic of HIV/AIDS (human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome) began in 1981, and is an ongoing worldwide public health issue. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), by 2023, HIV/AIDS ...

as a major threat to Africa, showcasing his forward-thinking approach to public health.

In addition to healthcare, Sankara focused on large-scale housing and infrastructure projects. He established brick factories to help build houses and reduce urban slums. This initiative provided affordable housing and created jobs, contributing to economic stability.

To combat deforestation, Sankara initiated "The People's Harvest of Forest Nurseries," supplying 7,000 village nurseries and organizing the planting of several million trees. This reforestation effort not only aimed to restore the environment but also to create sustainable agricultural practices. His administration connected all regions of the country through an extensive road and rail-building program. Over of rail was laid by Burkinabé people, facilitating manganese extraction in 'The Battle of the Rails,' without any foreign aid or outside money. These initiatives demonstrated his belief that African countries could achieve prosperity without foreign assistance.

Sankara also prioritized education to combat the country's 90% illiteracy rate. His administration implemented successful education programs, resulting in significant improvements in literacy. After his assassination, teachers' strikes and the new regime's unwillingness to negotiate led to the creation of 'Revolutionary Teachers.' In 1996, nearly 2,500 teachers were fired due to a strike, prompting the government to invite anyone with a college degree to teach through the revolutionary teachers' program. Volunteers received a 10-day training course before starting to teach.

Agriculture

In the 1980s, more than 90% of the populace were still agrarian farmers. Less than 6 percent of land that could be irrigated was receiving irrigation, while the rest relied on rain, which was highly unreliable and inadequate. Only 10% of the population had animals for plowing, whilst the rest relied on individual use of short hoes to plow. Few livestock herders had access tofodder

Fodder (), also called provender (), is any agriculture, agricultural foodstuff used specifically to feed domesticated livestock, such as cattle, domestic rabbit, rabbits, sheep, horses, chickens and pigs. "Fodder" refers particularly to food ...

; they had to roam the countryside in search of grazing land and watering spots. Because of this, hunger remained prevalent. In years of drought, the rural population was threatened by famines.

In Sankara's five-year plan, some 71% of projected investments for the productive sectors were allocated to agriculture, livestock, fishing, wildlife and forests. In 3 years, 25% more land was irrigated because of volunteer projects. In Sourou Valley, a dam

A dam is a barrier that stops or restricts the flow of surface water or underground streams. Reservoirs created by dams not only suppress floods but also provide water for activities such as irrigation, human consumption, industrial use, aqua ...

was built within a few months almost entirely by volunteer labour. The use of fertilizers increased by 56%. Hundreds of tractors were bought and imported for large-scale cooperative projects.

Hundreds of village cereal banks were built through collective labour organised by the CDRs to help farmers store and market their crops. In the past, farmers would have no way to store surplus grains and had to sell them to local merchants, who would sell the same crops back to the same village for twice the cost.

In August 1984, all land was nationalized. Previously, local chiefs had decided who could farm. In some areas, private land ownership had begun to arise. The total cereal production rose by 75% between 1983 and 1986. In four years, UN-analysts declared Burkinian agriculture as productive enough to be "food self-sufficient".

Environment

In the 1980s, when ecological awareness was still very low, Thomas Sankara was one of the few leaders to consider environmental protection a priority. He engaged in three major battles: against bush fires, 'which will be considered as crimes and will be punished as such'; against cattle roaming, 'which infringes on the rights of peoples because unattended animals destroy nature'; and against the chaotic cutting of firewood, 'whose profession will have to be organized and regulated'. As part of a development program involving a large part of the population, ten million trees were planted in Burkina Faso in fifteen months during the 'revolution'. To face the advancing desert and recurrent droughts, Thomas Sankara also proposed planting wooded strips of about fifty kilometers, crossing the country from east to west. He thought of extending this vegetation belt to other countries. Beginning in October 1984, over the space of fifteen months Sankara's government planted ten million trees in a campaign ofreforestation

Reforestation is the practice of restoring previously existing forests and woodlands that have been destroyed or damaged. The prior forest destruction might have happened through deforestation, clearcutting or wildfires. Three important purpose ...

. Sankara said "In Burkina wood is our only source of energy. We have to constantly remind every individual of his duty to maintain and regenerate nature".

People's Revolutionary Tribunals

Shortly after attaining power, Sankara constructed a system of courts known as the Popular Revolutionary Tribunal. The courts were created originally to try former government officials in a straightforward way so the average Burkinabé could participate in or oversee trials of enemies of the revolution. They placed defendants on trial for corruption, tax evasion, or counter-revolutionary activity. Sentences for former government officials were light and often suspended. The tribunals have been alleged to have been onlyshow trial

A show trial is a public trial in which the guilt (law), guilt or innocence of the defendant has already been determined. The purpose of holding a show trial is to present both accusation and verdict to the public, serving as an example and a d ...

s, held very openly with oversight from the public.

According to the US State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or simply the State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs o ...

, procedures in these trials, especially legal protections for the accused, did not conform to international standards. Defendants had to prove themselves innocent of the crimes they were charged with committing and were not allowed to be represented by counsel. The courts were initially highly admired by the Burkinabé people but were eventually labeled corrupt and oppressive. So-called 'lazy workers' were tried and sentenced to work for free, or expelled from their jobs and discriminated against. Some created their own courts to settle scores and humiliate their enemies.

Revolutionary Defence Committees

The Committees for the Defense of the Revolution () were formed as mass armed organizations. The CDRs were created as a counterweight to the power of the army as well as to promote political and social revolution. The idea for the Revolutionary Defence Committees was taken from Cuban leader Fidel Castro, whose Committees for the Defense of the Revolution had been created as a form of 'revolutionary vigilance'.Relations with the Mossi people

A point of contention regarding Sankara's rule is the way he handled the Mossi ethnic group. The Mossi are the largest ethnic group in Burkina Faso, and they adhere to a strict, traditional, hierarchical social systems. At the top of the hierarchy is the Morho Naba, the chief or king of the Mossi people. Sankara viewed this arrangement as an obstacle to national unity, and proceeded to demote the Mossi elite. The Morho Naba was not allowed to hold courts. Local village chiefs were stripped of their executive powers, which were given to the CDR.Women's rights

Sankara had extensively worked for women's rights and declared "There is no true social revolution without the liberation of women". Improving women's status in Burkinabé society was one of Sankara's explicit goals, and his government included a large number of women, an unprecedented policy priority in West Africa. His government bannedfemale genital mutilation

Female genital mutilation (FGM) (also known as female genital cutting, female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) and female circumcision) is the cutting or removal of some or all of the vulva for non-medical reasons. Prevalence of female ge ...

, forced marriage

Forced marriage is a marriage in which one or more of the parties is married without their consent or against their will. A marriage can also become a forced marriage even if both parties enter with full consent if one or both are later force ...

s and polygamy

Polygamy (from Late Greek , "state of marriage to many spouses") is the practice of marriage, marrying multiple spouses. When a man is married to more than one wife at the same time, it is called polygyny. When a woman is married to more tha ...

, while appointing women to high governmental positions and encouraging them to work outside the home and stay in school even if pregnant. Sankara promoted contraception

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth control only be ...

and in 1986 all restrictions on contraception were removed. He also established a Ministry of Family Development and the Union of Burkina Women.

Sankara recognized the challenges faced by African women when he gave his famous address to mark International Women's Day

International Women's Day (IWD) is celebrated on 8 March, commemorating women's fight for equality and liberation along with the women's rights movement. International Women's Day gives focus to issues such as gender equality, reproductive righ ...

on 8 March 1987 in Ouagadougou. Sankara spoke to thousands of women, saying that the Burkinabé Revolution was 'establishing new social relations', which would be 'upsetting the relations of authority between men and women and forcing each to rethink the nature of both. This task is formidable but necessary'. In addition to being the first African leader to appoint women to major cabinet positions, he recruited them actively for the military.

Agacher Strip War

Following the 1974 clashes between Burkina Faso and Mali over the disputed territory of the Agacher Strip, theOrganisation of African Unity

The Organisation of African Unity (OAU; , OUA) was an African intergovernmental organization established on 25 May 1963 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, with 33 signatory governments. Some of the key aims of the OAU were to encourage political and ec ...

had created a mediation commission to resolve the disagreement and provide for an independent, neutral demarcation of the border. Both governments had declared that they would not use armed force to end the dispute.

But by 1983 the two countries disagreed about the work of the commission. Sankara personally disliked Malian President Moussa Traoré, who had taken power by deposing Modibo Keïta's left-leaning regime. On 17 September Sankara visited Mali and met with Traoré. With Algerian mediation, the two agreed to have the border dispute settled by the International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; , CIJ), or colloquially the World Court, is the only international court that Adjudication, adjudicates general disputes between nations, and gives advisory opinions on International law, internation ...

(ICJ) and subsequently petitioned the body to resolve the issue.

In July 1985 Burkina Faso declared the Malian secretary general of the Economic Community of West Africa, Drissa Keita, a ''persona non grata

In diplomacy, a ' (PNG) is a foreign diplomat that is asked by the host country to be recalled to their home country. If the person is not recalled as requested, the host state may refuse to recognize the person concerned as a member of the diplo ...

'' after he criticized Sankara's regime. In September Sankara delivered a speech in which he called for a revolution in Mali. Malian leaders were particularly sensitive to the inflammatory rhetoric, as their country was undergoing social unrest. Around the same time, Sankara and other key figures in the CNR became convinced that Traoré was harbouring opposition to the Burkinabé regime in Bamako

Bamako is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Mali, with a 2022 population of 4,227,569. It is located on the Niger River, near the rapids that divide the upper and middle Niger valleys in the southwestern part of the country.

Bamak ...

and plotting to provoke a border war, which would be used to support a counterrevolution.

Tensions at the border began to rise on 24 November when one Burkinabé national killed another near the border in Soum Province. Malian police crossed the boundary to arrest the murderer and also detained several members of a local Committee for the Defence of the Revolution who were preparing a tribunal. Three days later Malian police entered Kounia to 'restore order'. Burkina Faso made diplomatic representations on the incidents to Mali, but was given no formal response.

At the beginning of December, Burkina Faso informed Mali and other surrounding countries that it was conducting its decennial national census from 10 to 20 December. On 14 December military personnel entered the Agacher to assist with the census. Mali accused the military authorities of pressuring Malian citizens in border villages to register with the census, a charge which Burkina Faso disputed. In an attempt to reduce tensions, ANAD (a West African treaty organization) dispatched a delegation to Bamako and Ouagadougou to mediate. President of Algeria Chadli Bendjedid contacted Sankara and Traoré to encourage a peaceful resolution. At the request of ANAD members, Burkina Faso announced the withdrawal of all military personnel from the disputed region.

Despite the declared withdrawal, a 'war of the communiques' ensued as Burkinabé and Malian authorities exchanged hostile messages. Feeling threatened by Sankara, Traoré began preparing Mali for hostilities with Burkina Faso. Three ''groupements'' were formed and planned to invade Burkina Faso and converge on the city of Bobo-Dioulasso

Bobo-Dioulasso ( , ) is a city in Burkina Faso with a population of 1,129,000 (); it is the second-largest city in the country, after Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso's capital. The name means "home of the Bobo- Dioula".

The local Bobo-speaking pop ...

. Once there, they would rally Burkinabé opposition forces to take Ouagadougou and overthrow Sankara.

Former Sankara aide Paul Michaud wrote that Sankara had intended to provoke Mali into conflict with the aim of mobilizing popular support for his regime. According to Michaud, "an official—and reliable—Malian source" had reported that mobilization

Mobilization (alternatively spelled as mobilisation) is the act of assembling and readying military troops and supplies for war. The word ''mobilization'' was first used in a military context in the 1850s to describe the preparation of the ...

documents dating to 19 December were found on the bodies of fallen Burkinabé soldiers during the ensuing war.

Sankara's efforts to provide evidence of his bona fides were systematically undermined. 'It is hard to believe that the Malian authorities are unaware that the rumors circulating are false,' says U.S. Ambassador Leonardo Neher. In contrast to Michaud's assertion, a Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) cable states, 'The war was born of Bamako's hope that the conflict would trigger a coup in Burkina Faso.'

At dawn on 25 December 1985, about 150 Malian Armed Forces tanks crossed the frontier and attacked several locations. Malian troops also attempted to envelop Bobo-Dioulasso in a pincer Pincer may refer to:

*Pincers (tool)

*Pincer (biology), part of an animal

*Pincer ligand, a terdentate, often planar molecule that tightly binds a variety of metal ions

*Pincer (Go), a move in the game of Go

*"Pincers!", an episode of the TV series ...

attack. The Burkina Faso Army struggled to repel the offensive in the face of superior Malian firepower and were overwhelmed on the northern front; Malian forces quickly secured the towns of Dionouga, Selba, Kouna, and Douna in the Agacher. The Burkinabé government in Ouagadougou received word of hostilities at about 13:00 and immediately issued mobilization orders. Various security measures were also imposed across the country, including nighttime blackouts.

Burkinabé forces regrouped in the Dionouga area to counter-attack

A counterattack is a tactic employed in response to an attack, with the term originating in " war games". The general objective is to negate or thwart the advantage gained by the enemy during attack, while the specific objectives typically seek ...

. Captain Compaoré took command of this western front. Under his leadership soldiers split into small groups and employed guerrilla tactics

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, Partisan (military), partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include Children in the military, recruite ...

against Malian tanks.

Immediately after hostilities began, other African leaders attempted to institute a truce. On the morning of 30 December, Burkina Faso and Mali agreed to an ANAD-brokered ceasefire. By then Mali had occupied most of the Agacher Strip. More than 100 Burkinabé and approximately 40 Malian soldiers and civilians were killed during the war. The Burkinabé towns of Ouahigouya, Djibo, and Nassambou were left badly damaged by the fighting.

At an ANAD summit in Yamoussoukro on 17 January 1987, Traoré and Sankara met and formalized an agreement to end hostilities. The ICJ later split the Agacher; Mali received the more-densely populated western portion and Burkina Faso the eastern section centred on the Béli River. Both countries indicated their satisfaction with the judgement.

Burkina Faso declared that the war was part of an 'international plot' to bring down Sankara's government. It rejected speculation that it was fought over rumoured mineral wealth in the Agacher. The country's relatively poor performance in the conflict damaged the domestic credibility of the CNR. Some Burkinabé soldiers were angered by Sankara's failure to prosecute the war more aggressively and rally a counteroffensive against Mali.

The conflict also demonstrated the country's weak international position and forced the CNR to craft a more moderate image of its policies and goals abroad. In the aftermath, the Burkinabé government made little reference to supporting revolution in other countries, and its relations with France modestly improved. At a rally held after the war, Sankara conceded that his country's military was not adequately armed and announced the commutation of sentences for numerous political prisoners.

Relations with other countries

Thomas Sankara defined his program as anti-imperialist. In this respect,France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

became the main target of revolutionary rhetoric. When President François Mitterrand

François Maurice Adrien Marie Mitterrand (26 October 19168 January 1996) was a French politician and statesman who served as President of France from 1981 to 1995, the longest holder of that position in the history of France. As a former First ...

visited Burkina Faso in November 1986, Sankara criticized the French for having received P. W. Botha, the Prime Minister of South Africa

The prime minister of South Africa ( was the head of government in South Africa between 1910 and 1984.

History of the office

The position of Prime Minister was established in 1910, when the Union of South Africa was formed. He was appointed ...

, which still enforced apartheid

Apartheid ( , especially South African English: , ; , ) was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. It was characterised by an ...

; and Jonas Savimbi

Jonas Malheiro Sidónio Sakaita Savimbi (; 3 August 1934 – 22 February 2002) was an Angolan revolutionary, politician, and rebel military leader who founded and led the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola ( UNITA). UNITA was on ...

, the leader of UNITA, in France, referring to both men as 'covered in blood from head to toe'. In response, France reduced its economic aid to Burkina Faso by 80% between 1983 and 1985.

, President Mitterrand's advisor on African affairs, organized a media campaign in France to denigrate Thomas Sankara in collaboration with the DGSE. It provided the press with a series of documents on supposed atrocities intended to feed articles against him.

Sankara set up a program of cooperation with Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

. After meeting with Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban politician and revolutionary who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and President of Cuba, president ...

, Sankara arranged to send young Burkinabés to Cuba in September 1986 to receive professional training and to participate in the country's development upon their return. These were volunteers recruited on the basis of a competition; priority was given to orphans and young people from rural and disadvantaged areas. Some 600 teenagers were flown to Cuba to complete their schooling and receive professional training to become doctors (particularly gynecologists), engineers, or agronomists.

Denouncing the support of the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

to Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

and South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

, he called on African countries to boycott the 1984 Summer Olympics

The 1984 Summer Olympics (officially the Games of the XXIII Olympiad and commonly known as Los Angeles 1984) were an international multi-sport event held from July 28 to August 12, 1984, in Los Angeles, California, United States. It marked the ...

in Los Angeles

Los Angeles, often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, most populous city in the U.S. state of California, and the commercial, Financial District, Los Angeles, financial, and Culture of Los Angeles, ...

. At the United Nations General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; , AGNU or AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as its main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ. Currently in its Seventy-ninth session of th ...

, he denounced the invasion of Grenada by the United States. The latter nation responded by implementing trade sanctions against Burkina Faso. Also at the UN, Sankara called for an end to the veto power granted to the great powers. In the name of the 'right of peoples to sovereignty', he supported the national demands of the Western Sahara

Western Sahara is a territorial dispute, disputed territory in Maghreb, North-western Africa. It has a surface area of . Approximately 30% of the territory () is controlled by the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR); the remaining 70% is ...

, Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

, the Nicaraguan Sandinistas, and the South African ANC.

While he had good relations with Ghanaian leader Jerry Rawlings

Jerry John Rawlings (born Jerry Rawlings John; 22 June 194712 November 2020) was a Ghanaian military officer, aviator, and politician who led the country briefly in 1979 and then from 1981 to 2001. He led a military junta until 1993 and then se ...

and Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi

Muammar Muhammad Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi (20 October 2011) was a Libyan military officer, revolutionary, politician and political theorist who ruled Libya from 1969 until Killing of Muammar Gaddafi, his assassination by Libyan Anti-Gaddafi ...

, Sankara was relatively isolated in West Africa. Leaders close to France, such as Félix Houphouët-Boigny in Ivory Coast

Ivory Coast, also known as Côte d'Ivoire and officially the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire, is a country on the southern coast of West Africa. Its capital city of Yamoussoukro is located in the centre of the country, while its largest List of ci ...

and Hassan II in Morocco

Morocco, officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It has coastlines on the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to Algeria–Morocc ...

, were particularly hostile to him.

Criticism

The British development organization Oxfam recorded the arrest of trade union leaders in 1987. In 1984, seven individuals associated with the previous régime in Burkina Faso were accused of treason and executed after a summary trial. Non-governmental organizations and unions were harassed or placed under the authority of the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution, branches of which were established in each workplace and which functioned as 'organs of political and social control'. Three days after Sankara had assumed power in 1983 through the popular revolution, the National Union of African Teachers of Upper Volta (SNEAHV) called Sankara and his governmentfascist

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural soci ...

and called upon workers to be ready to fight for their freedom. As a result, the government ordered the arrest of 4 key figures of the SNEAHV, one was released shortly after. In response, the SNEAHV called upon a national teachers' strike to protest the arrests. The government saw this as something that endangered the politically weak Upper Volta which had already faced 5 coups since its independence. Therefore, the minister for National Education called upon directors of private school

A private school or independent school is a school not administered or funded by the government, unlike a State school, public school. Private schools are schools that are not dependent upon national or local government to finance their fina ...

s "not to use the services of the strikers in their establishments". The call affected 1300-1500 teachers.

Popular Revolutionary Tribunals, set up by the government throughout the country, placed defendants on trial for corruption, tax evasion or 'counter-revolutionary' activity. Procedures in these trials, especially legal protections for the accused, did not conform to international standards. According to Christian Morrisson and Jean-Paul Azam of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD; , OCDE) is an international organization, intergovernmental organization with 38 member countries, founded in 1961 to stimulate economic progress and international trade, wor ...

, the 'climate of urgency and drastic action in which many punishments were carried out immediately against those who had the misfortune to be found guilty of unrevolutionary behaviour, bore some resemblance to what occurred in the worst days of the French Revolution, during the Reign of Terror

The Reign of Terror (French: ''La Terreur'', literally "The Terror") was a period of the French Revolution when, following the creation of the French First Republic, First Republic, a series of massacres and Capital punishment in France, nu ...

. Although few people were killed, violence was widespread'.

Death

On 15 October 1987, Sankara and twelve other officials were killed in acoup d'état

A coup d'état (; ; ), or simply a coup

, is typically an illegal and overt attempt by a military organization or other government elites to unseat an incumbent leadership. A self-coup is said to take place when a leader, having come to powe ...

organized by his former colleague Blaise Compaoré. When accounting for his overthrow, Compaoré stated that Sankara jeopardized foreign relations with former colonial power France and neighbouring Ivory Coast, and accused his former comrade of plotting to assassinate opponents.

Prince Johnson, a former Liberian warlord allied to Charles Taylor and killer of the Liberian president Samuel Doe whose last hours of life were filmed, told Liberia's Truth and Reconciliation Commission

A truth commission, also known as a truth and reconciliation commission or truth and justice commission, is an official body tasked with discovering and revealing past wrongdoing by a government (or, depending on the circumstances, non-state ac ...

that it was engineered by Charles Taylor. After the coup and although Sankara was known to be dead, some CDRs mounted an armed resistance to the army for several days.

According to Halouna Traoré, the sole survivor of Sankara's assassination, Sankara was attending a meeting with the Conseil de l'Entente. His assassins singled out Sankara and executed him. The assassins then shot at those attending the meeting, killing 12 other people. Sankara's body was riddled with bullets to the back and he was quickly buried in an unmarked grave while his widow Mariam and two children fled the nation. Compaoré immediately reversed the nationalization

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English)

is the process of transforming privately owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization contrasts with p ...

s, overturned nearly all of Sankara's policies, rejoined the International Monetary Fund

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is a major financial agency of the United Nations, and an international financial institution funded by 191 member countries, with headquarters in Washington, D.C. It is regarded as the global lender of las ...

and World Bank

The World Bank is an international financial institution that provides loans and Grant (money), grants to the governments of Least developed countries, low- and Developing country, middle-income countries for the purposes of economic development ...

to bring in 'desperately needed' funds to restore the 'shattered' economy and ultimately spurned most of Sankara's legacy. Compaoré's dictatorship remained in power for 27 years until it was overthrown by popular protests in 2014.

Trial

In 2017, the Burkina Faso government officially asked the French government to release military documents on the killing of Sankara after his widow accused France of masterminding his assassination. The French presidentEmmanuel Macron

Emmanuel Jean-Michel Frédéric Macron (; born 21 December 1977) is a French politician who has served as President of France and Co-Prince of Andorra since 2017. He was Ministry of Economy and Finance (France), Minister of Economics, Industr ...

promised to "declassify" French documents concerning Sankara's assassination.

In April 2021, 34 years after Sankara's assassination, former president Compaoré and 13 others were indicted for complicity in the murder of Sankara as well as other crimes in the coup. This development came as part of President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré's framework of 'national reconciliation'.

In October 2021, the trial against Compaoré and 13 others began in Ouagadougou

Ouagadougou or Wagadugu (, , , ) is the capital city of Burkina Faso, and the administrative, communications, cultural and economic centre of the nation. It is also the List of cities in Burkina Faso#Largest cities, country's largest city, wi ...

, with Compaoré being tried ''in absentia

''In Absentia'' is the seventh studio album by British progressive rock band Porcupine Tree, first released on 24 September 2002. The album marked several changes for the band, with it being the first with new drummer Gavin Harrison and the f ...

''. Ex-presidential security chief Hyacinthe Kafondo, was also tried in absentia. A week before the trial, Compaoré's lawyers stated that he wouldn't be attending the trial which they characterized as having defects, and also emphasized his privilege for immunity, being the former head of state. After requests made by the defence attorneys for more time to prepare their defence, the hearing was postponed until 1 March.

On 6 April 2022, Compaoré and two others were found guilty and sentenced to life in prison in absentia. Eight others were sentenced to between 3 and 20 years in prison. Three were found innocent.

Exhumation

The exhumation of what are believed to be the remains of Sankara started on African Liberation Day, 25 May 2015. Permission for an exhumation was denied during the rule of his successor, Blaise Compaoré. The exhumation would allow the family to formally identify the remains, a long-standing demand of his family and supporters. In October 2015, one of the lawyers for Sankara's widow Mariam reported that the autopsy revealed that Sankara's body was 'riddled' with 'more than a dozen' bullets. In 2025, Sankara and those killed alongside him in the 1987 coup were reinterred in a mausoleum built on the site of the Conseil de l’Entente in Ouagadougou.Legacy

Solidarity

*He sold off the government fleet of Mercedes cars and made the Renault 5 (the cheapest car sold in Burkina Faso at that time) the official service car of the ministers. *He reduced the salaries of well-off public servants (including his own) and forbade the use of government chauffeurs and first class airline tickets. *He opposed foreign aid, saying that 'He who feeds you, controls you'. *He spoke in forums like theOrganisation of African Unity

The Organisation of African Unity (OAU; , OUA) was an African intergovernmental organization established on 25 May 1963 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, with 33 signatory governments. Some of the key aims of the OAU were to encourage political and ec ...

against what he described as neocolonialist penetration of Africa through Western trade and finance.

*He called for a united front of African nations to repudiate their external debt

A country's gross external debt (or foreign debt) is the liabilities that are owed to nonresidents by residents. The debtors can be government, governments, corporation, corporations or citizens. External debt may be denominated in domestic or f ...

. He argued that the poor and exploited did not have an obligation to repay money to the rich and exploiting.

*In Ouagadougou, Sankara converted the army's provisioning store into a state-owned supermarket open to everyone (the first supermarket in the country).

*He forced well-off civil servants to pay one month's salary to public projects.

*He refused to use the air conditioning in his office on the grounds that such luxury was not available to anyone but a handful of Burkinabés.

*As President, he lowered his salary to $450 a month and limited his possessions to a car, four bikes, three guitars, a refrigerator, and a broken freezer.

Style

*He required public servants to wear a traditional tunic, woven from Burkinabé cotton and sewn by Burkinabé craftsmen. *He was known for jogging unaccompanied throughOuagadougou

Ouagadougou or Wagadugu (, , , ) is the capital city of Burkina Faso, and the administrative, communications, cultural and economic centre of the nation. It is also the List of cities in Burkina Faso#Largest cities, country's largest city, wi ...

in his track suit and posing in his tailored military fatigues, with his mother-of-pearl pistol.

*When asked why he did not want his portrait hung in public places, as was the norm for other African leaders, Sankara replied: "There are seven million Thomas Sankaras".

*An accomplished guitarist, he wrote the new national anthem himself.

Burkina Faso

A statue of Sankara was unveiled in 2019 at the location in Ouagadougou where he was assassinated; however due to complaints that it did not match his facial features, a new statue was unveiled a year later. In 2023, the government of Burkina Faso formally proclaimed Sankara as a "hero of the nation". In October 2023, on the 36th anniversary of his assassination, the government changed a main road name inOuagadougou

Ouagadougou or Wagadugu (, , , ) is the capital city of Burkina Faso, and the administrative, communications, cultural and economic centre of the nation. It is also the List of cities in Burkina Faso#Largest cities, country's largest city, wi ...

to honor Sankara. The road in question was the Boulevard Charles de Gaulle, now known as Boulevard Capitaine Thomas Isidore Noël Sankara.

International recognition

Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

awarded Sankara with the highest honour of the state, the Order of José Martí.

Twenty years after his assassination, Sankara was commemorated on 15 October 2007 in ceremonies that took place in Burkina Faso, Mali, Senegal, Niger, Tanzania, Burundi, France, Canada and the United States.

Africa's Che Guevara

Sankara is often referred to as " Africa'sChe Guevara

Ernesto "Che" Guevara (14th May 1928 – 9 October 1967) was an Argentines, Argentine Communist revolution, Marxist revolutionary, physician, author, Guerrilla warfare, guerrilla leader, diplomat, and Military theory, military theorist. A majo ...

". Sankara gave a speech marking and honouring the 20th anniversary of Che Guevara's 9 October 1967 execution, one week before his own assassination on 15 October 1987.

List of works

*''Thomas Sankara Speaks: The Burkina Faso Revolution, 1983–87'',Pathfinder Press

Pathfinder, Path Finder or Pathfinders may refer to:

Aerospace

* ''Mars Pathfinder'', a NASA Mars Lander

* NASA Pathfinder, a high-altitude, solar-powered uncrewed aircraft

* Space Shuttle ''Pathfinder'', a Space Shuttle test simulator

Arts and ...

: 1988. .

*''We Are the Heirs of the World's Revolutions: Speeches from the Burkina Faso Revolution 1983–87'', Pathfinder Press: 2007. .

*''Women's Liberation and the African Freedom Struggle'', Pathfinder Press: 1990. .

Further reading

Books

Monographs

*''Who killed Sankara?'', by Alfred Cudjoe, 1988, University of California, . *''La voce nel deserto'', by Vittorio Martinelli and Sofia Massai, 2009, Zona Editrice, . *''Thomas Sankara – An African Revolutionary'', by Ernest Harsch, 2014, Ohio University Press, . *''A Certain Amount of Madness: The Life, Politics and Legacies of Thomas Sankara (Black Critique)'', by Amber Murrey, 2018, Pluto Press, . *''Sankara, Compaoré et la révolution burkinabè'', by Ludo Martens and Hilde Meesters, 1989, Editions Aden, . *''Military Marxism: Africa's Contribution to Revolutionary Theory, 1957-2023'', by Adam Mayer, 2025, Lexington Books, Lanham.Historical novel including Thomas Sankara

*''American Spy'', by Lauren Wilkinson, 2019, Random House, .Web articles

''Burkina Faso's Pure President''

by Bruno Jaffré.

''Thomas Sankara Lives!''

by Mukoma Wa Ngugi.

''There Are Seven Million Sankaras''

by Koni Benson.

''Thomas Sankara: "I have a Dream"''

by Federico Bastiani.

''Thomas Sankara: Chronicle of an Organised Tragedy''

by Cheriff M. Sy.

''Thomas Sankara Former Leader of Burkina Faso''

by Désiré-Joseph Katihabwa.

''Thomas Sankara 20 Years Later: A Tribute to Integrity''

by Demba Moussa Dembélé.

Remembering Thomas Sankara

Rebecca Davis, ''The Daily Maverick'', 2013.

"I can hear the roar of women's silence"

Sokarie Ekine, ''Red Pepper'', 2012.

''Thomas Sankara: A View of The Future for Africa and The Third World''

by Ameth Lo.

''Thomas Sankara on the Emancipation of Women, An internationalist whose ideas live on!''

by Nathi Mthethwa.

''Thomas Sankara, le Che africain''

by Pierre Venuat (in French).

''Thomas Sankara e la rivoluzione interrotta''

by Enrico Palumbo (in Italian).

Documentaries

*, 1987 documentary by Didier Mauro *, 1991 documentary by Balufu Bakupa-Kanyinda *'' Thomas Sankara: The Upright Man'', 2006 documentary by Robin Shuffield *, 2007 documentary by Thuy-Tiên Hô and Didier Mauro *, 2011 documentary by Tristan Goasguen *, 2012 documentary by Christophe Cupelin *, 2017 documentary by Thuy-Tiên HôReferences

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

ThomasSankara.net

a website dedicated to Thomas Sankara * {{DEFAULTSORT:Sankara, Thomas * 1949 births 1987 deaths 1987 murders in Africa African Marxists African politicians assassinated in the 1980s Anti-French sentiment Anti-imperialists Assassinated Burkinabe politicians Assassinated heads of state in Africa Assassinated revolutionaries Burkinabe communists Burkinabe military personnel Burkinabe nationalists Burkinabe pan-Africanists Burkinabe revolutionaries Burkinabe Roman Catholics Heads of state of Burkina Faso Leaders ousted by a coup Leaders who took power by coup Male feminists Marxist theorists National anthem writers People from Nord Region (Burkina Faso) People from Sud-Ouest Region (Burkina Faso) People murdered in Burkina Faso Politicians assassinated in 1987 Prime ministers of Burkina Faso