Thomas Parker (inventor) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thomas Parker (22 December 1843 – 5 December 1915) was an English

Engineering Timelines, accessed 29 July 2015.

Wolverhampton History and Heritage Website, accessed 29 July 2015. He attended the

Wolverhampton History and Heritage Website, accessed 29 July 2015. In Wolverhampton, Elwell and Parker began to manufacture accumulators (lead-acid batteries). From 1883 they manufactured dynamos. The business began to expand: there was soon a demand for dynamos, from the Manchester Edison Company and from Trafalgar Colliery in the

In Wolverhampton, Elwell and Parker began to manufacture accumulators (lead-acid batteries). From 1883 they manufactured dynamos. The business began to expand: there was soon a demand for dynamos, from the Manchester Edison Company and from Trafalgar Colliery in the

Wolverhampton History and Heritage Website, accessed 29 July 2015. In 1893, the company was in difficulty and was reformed as the Electric Construction Company. In 1894, Parker resigned from the company and set up Thomas Parker Ltd. in Wolverhampton, making electrical equipment. (The company was eventually wound up in 1909.)

Wolverhampton History and Heritage Website, accessed 29 July 2015. In 1892 he designed the high voltage DC system for distributing electricity in the cities of

In 1899 Parker resigned as managing director of Thomas Parker Ltd. He moved to London, where he was consulting engineer to the

In 1899 Parker resigned as managing director of Thomas Parker Ltd. He moved to London, where he was consulting engineer to the

Wolverhampton History and Heritage Website, accessed 29 July 2015. In 1905 he actively promoted a decimal system of his own creation, based on English weights, measures and currency.

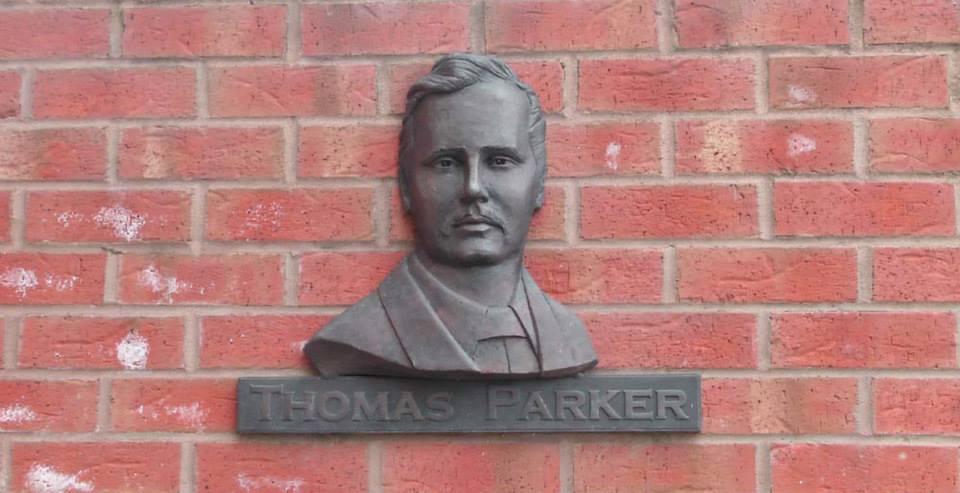

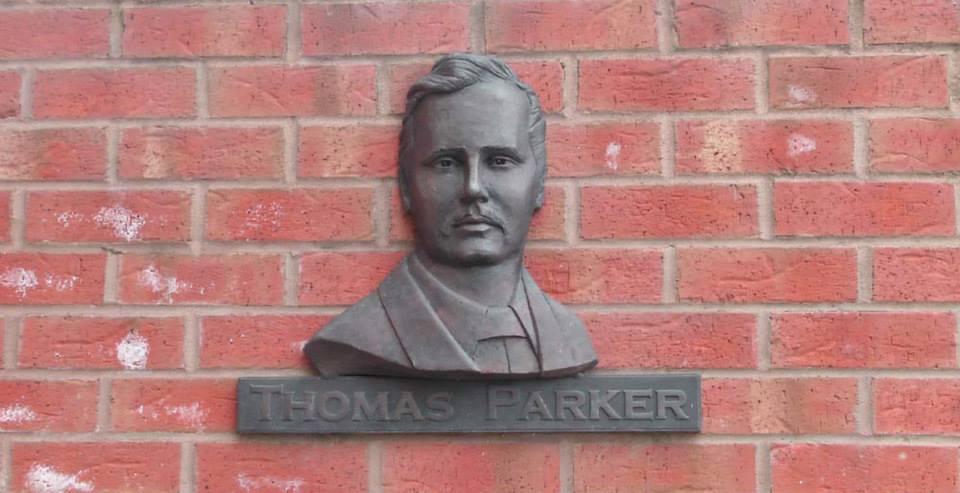

Wolverhampton History and Heritage Website, accessed 29 July 2015. He had twelve children, of whom nine survived to maturity. His son Charles Henry Parker ran the company that produced Coalite; his son Thomas Hugh Parker was an inventor, building prototype motor cars. A commemorative plaque was unveiled at the former Severn House, now a hotel (The Best Western Valley Hotel), on 10 October 2015.Thomas Parker Day

Madeley Town Council, accessed 28 April 2016.

Elwell-Parker

Website of the present-day Elwell-Parker company founded in America in 1893 {{DEFAULTSORT:Parker, Thomas 1843 births 1915 deaths 19th-century English engineers 19th-century English inventors 20th-century English engineers 20th-century English inventors English electrical engineers Deaths from brain cancer in England Engineers from Shropshire English industrialists Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Liberal Party (UK) parliamentary candidates People from Coalbrookdale Sustainable transport pioneers

electrical engineer

Electrical engineering is an engineering discipline concerned with the study, design, and application of equipment, devices, and systems that use electricity, electronics, and electromagnetism. It emerged as an identifiable occupation in the l ...

, inventor

An invention is a unique or novel device, method, composition, idea, or process. An invention may be an improvement upon a machine, product, or process for increasing efficiency or lowering cost. It may also be an entirely new concept. If an ...

and industrialist

A business magnate, also known as an industrialist or tycoon, is a person who is a powerful entrepreneur and investor who controls, through personal enterprise ownership or a dominant shareholding position, a firm or industry whose goods or ser ...

. He patented improvements in lead-acid batteries and dynamo

"Dynamo Electric Machine" (end view, partly section, )

A dynamo is an electrical generator that creates direct current using a commutator. Dynamos employed electromagnets for self-starting by using residual magnetic field left in the iron cores ...

s, and was a pioneer of manufacturing equipment that powered electric tramway

A tram (also known as a streetcar or trolley in Canada and the United States) is an urban rail transit in which Rolling stock, vehicles, whether individual railcars or multiple-unit trains, run on tramway tracks on urban public streets; some ...

s and electric lighting

Electric light

Electric light is an artificial light source powered by electricity.

Electric Light may also refer to:

* Light fixture, a decorative enclosure for an electric light source

* Electric Light (album), ''Electric Light'' (album), a 201 ...

. He invented the smokeless fuel Coalite

Coalite is a brand of low-temperature coke used as a smokeless fuel. The title refers to the residue left behind when coal is carbonised at . It was invented by Thomas Parker in 1904. In 1936 the Smoke Abatement Society awarded its inventor a ...

. He formed the first company to distribute electricity over a wide area.

He was described by Lord Kelvin

William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin (26 June 182417 December 1907), was a British mathematician, Mathematical physics, mathematical physicist and engineer. Born in Belfast, he was the Professor of Natural Philosophy (Glasgow), professor of Natur ...

as "the Edison of Europe".Thomas ParkerEngineering Timelines, accessed 29 July 2015.

Early life

Parker was born at Lincoln HillReport by Toby Neal, title refers to Thomas Parker day being held 10 October 2015, organized by Madeley Living History Group. inCoalbrookdale

Coalbrookdale is a town in the Ironbridge Gorge and the Telford and Wrekin borough of Shropshire, England, containing a settlement of great significance in the history of iron ore smelting. It lies within the civil parish called The Gorge, Shro ...

, Shropshire

Shropshire (; abbreviated SalopAlso used officially as the name of the county from 1974–1980. The demonym for inhabitants of the county "Salopian" derives from this name.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West M ...

, son of Thomas Wheatley Parker and Ann ''née'' Fletcher. His father was a moulder at the Coalbrookdale Ironworks. The ironworks had been founded by Abraham Darby I

Abraham Darby, in his later life called Abraham Darby the Elder, now sometimes known for convenience as Abraham Darby I (14 April 1677 – 5 May 1717, the first and best known of Abraham Darby (disambiguation), several men of that name), was ...

in the early 18th century, and Parkers had worked there for several generations. Thomas attended the local Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally, others referred to them as Quakers ...

school. His first work was as a moulder, with his father.Thomas Parker:The Early YearsWolverhampton History and Heritage Website, accessed 29 July 2015. He attended the

1862 International Exhibition

The International Exhibition of 1862, officially the London International Exhibition of Industry and Art, also known as the Great London Exposition, was a world's fair held from 1 May to 1 November 1862 in South Kensington, London, England. Th ...

in London, where he was one of four representatives of the Coalbrookdale Company. He was inspired by the technology shown there, which included the electric telegraph

Electrical telegraphy is Point-to-point (telecommunications), point-to-point distance communicating via sending electric signals over wire, a system primarily used from the 1840s until the late 20th century. It was the first electrical telecom ...

and the wet battery

Electric battery, Batteries provided the main source of electricity before the development of electric generators and electrical grids around the end of the 19th century. Successive improvements in battery technology facilitated major electric ...

.

Later in that year he moved to Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands, within the wider West Midlands (region), West Midlands region, in England. It is the Lis ...

, to get more experience as a moulder; during this time he attended lectures of the nonconformist preacher George Dawson George Dawson may refer to:

Politicians

* George Dawson (Northern Ireland politician) (1961–2007), Northern Ireland politician

* George Walker Wesley Dawson (1858–1936), Canadian politician

* George Oscar Dawson (1825–1865), Georgia poli ...

. He later moved to the Potteries

The Staffordshire Potteries is the industrial area encompassing the six towns Burslem, Fenton, Staffordshire, Fenton, Hanley, Staffordshire, Hanley, Longton, Staffordshire, Longton, Tunstall, Staffordshire, Tunstall and Stoke-upon-Trent, Stoke ( ...

, where in 1866 he married Jane Gibbons, daughter of engine-driver Lewis Gibbons. They moved to Manchester

Manchester () is a city and the metropolitan borough of Greater Manchester, England. It had an estimated population of in . Greater Manchester is the third-most populous metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, with a population of 2.92&nbs ...

where he attended chemistry lectures of Henry Enfield Roscoe

Sir Henry Enfield Roscoe (7 January 1833 – 18 December 1915) was a British chemist. He is particularly noted for early work on vanadium, photochemical studies, and his assistance in creating Oxo, in its earlier liquid form.

Life and work ...

and others.

In December 1867 they moved to Coalbrookdale; Parker, initially working as a foreman, was soon offered the post of chemist in the electroplating

Electroplating, also known as electrochemical deposition or electrodeposition, is a process for producing a metal coating on a solid substrate through the redox, reduction of cations of that metal by means of a direct current, direct electric cur ...

department.

Early inventions

In 1876 he and Philip Weston, a machinist at Coalbrookdale, received a patent for an improvedsteam pump

A pump is a device that moves fluids (liquids or gases), or sometimes Slurry, slurries, by mechanical action, typically converted from electrical energy into hydraulic or pneumatic energy.

Mechanical pumps serve in a wide range of application ...

. This was Parker's first major invention. "Parker and Weston's Patent Pump", manufactured only by the Coalbrookdale Company, was awarded a medal at the International Inventions Exhibition

The International Inventions Exhibition was a world's fair held in South Kensington in 1885. As with the earlier exhibitions in a series of fairs in South Kensington following the Great Exhibition, Queen Victoria was patron and her son Albert Edw ...

of 1885.

In the electroplating department, he replaced battery cells, which powered the process, with a large dynamo

"Dynamo Electric Machine" (end view, partly section, )

A dynamo is an electrical generator that creates direct current using a commutator. Dynamos employed electromagnets for self-starting by using residual magnetic field left in the iron cores ...

which he had designed and built; it was probably the first time a dynamo was used for this purpose.

Around this time there was national concern about the detrimental effect of coal smoke on cities, publicized by the Kyrle Society

Miranda Hill (Wisbech, Cambridgeshire 1836–1910) was an English social reformer.

Biography

Hill was a daughter of James Hill (died 1872), a corn merchant, banker and follower of Robert Owen, and his third wife, Caroline Southwood Smith ...

. The Coalbrookdale Company produced the "Kyrle Grate", invented by Parker; it was an open grate in which anthracite coal

Anthracite, also known as hard coal and black coal, is a hard, compact variety of coal that has a submetallic lustre. It has the highest carbon content, the fewest impurities, and the highest energy density of all types of coal and is the highe ...

could be burnt. It was awarded a silver medal at the Smoke Abatement Exhibition in 1881.

Parker worked on improvements on the lead-acid battery invented by Gaston Planté

Gaston Planté (; 22 April 1834 – 21 May 1889) was a French physicist who invented the lead–acid battery in 1859. This type battery was developed as the first rechargeable electric battery marketed for commercial use and it is widely used in ...

. He took out a patent in 1882, which coincided with Gaston Planté's own patent for the same improvement; two separate patents were granted. In June 1882 Parker and Paul Bedford Elwell took out patents for improvements in dynamos and electric lighting.

The Elwell-Parker Company

In October 1882, Parker and his family moved toWolverhampton

Wolverhampton ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the West Midlands (county), West Midlands of England. Located around 12 miles (20 km) north of Birmingham, it forms the northwestern part of the West Midlands conurbation, with the towns of ...

to set up in business with Paul Bedford Elwell (1853–1899). (Elwell's family had a factory there, that made nails and horseshoes.)Thomas Parker:Elwell-Parker LtdWolverhampton History and Heritage Website, accessed 29 July 2015.

In Wolverhampton, Elwell and Parker began to manufacture accumulators (lead-acid batteries). From 1883 they manufactured dynamos. The business began to expand: there was soon a demand for dynamos, from the Manchester Edison Company and from Trafalgar Colliery in the

In Wolverhampton, Elwell and Parker began to manufacture accumulators (lead-acid batteries). From 1883 they manufactured dynamos. The business began to expand: there was soon a demand for dynamos, from the Manchester Edison Company and from Trafalgar Colliery in the Forest of Dean

The Forest of Dean is a geographical, historical and cultural region in the western part of the Counties of England, county of Gloucestershire, England. It forms a roughly triangle, triangular plateau bounded by the River Wye to the west and no ...

, for electric lighting in the mine. (This is thought to be the first time electric lighting was used underground.) Elwell-Parker dynamos supplied lighting in industrial works, and equipment was supplied for a tramway in Blackpool

Blackpool is a seaside town in Lancashire, England. It is located on the Irish Sea coast of the Fylde peninsula, approximately north of Liverpool and west of Preston, Lancashire, Preston. It is the main settlement in the Borough of Blackpool ...

in 1885, the first electric tramway in the country. A prototype battery-powered tram was tested on the tramway in Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands, within the wider West Midlands (region), West Midlands region, in England. It is the Lis ...

. Several prototype electric car

An electric car or electric vehicle (EV) is a passenger car, passenger automobile that is propelled by an electric motor, electric traction motor, using electrical energy as the primary source of propulsion. The term normally refers to a p ...

s were built. Between 1884 and 1887, further patents were taken out by Parker and Elwell for electrical equipment. In 1887 he developed a process to extract phosphorus and chlorate of soda by electrolysis

In chemistry and manufacturing, electrolysis is a technique that uses Direct current, direct electric current (DC) to drive an otherwise non-spontaneous chemical reaction. Electrolysis is commercially important as a stage in the separation of c ...

.

In the general election of July 1892 Parker stood as a Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world.

The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left. For example, while the political systems ...

candidate for Kingswinford

Kingswinford is a town of the Metropolitan Borough of Dudley in the English West Midlands (county), West Midlands, situated west-southwest of central Dudley. In 2011 the area had a population of 25,191, down from 25,808 at the 2001 Census.

T ...

, where he was defeated by the Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

candidate, the incumbent MP Alexander Staveley Hill. In 1893, he became a justice of the peace in Wolverhampton.

In 1889, the Electric Construction Corporation (E.C.C.), was founded by a syndicate to manufacture electrical equipment, and it purchased the Elwell-Parker company and others making similar equipment. A new factory was built in Bushbury

Bushbury is a suburban village and ward in the City of Wolverhampton in the West Midlands, England. It lies two miles north-east of Wolverhampton city centre, divided between the Bushbury North and Bushbury South and Low Hill wards. Bushbury ...

, Wolverhampton. Parker failed to become a company director, but was appointed Works Manager. In 1893 an American branch of Elwell-Parker was founded in Cleveland

Cleveland is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located along the southern shore of Lake Erie, it is situated across the Canada–U.S. maritime border and approximately west of the Ohio-Pennsylvania st ...

, Ohio

Ohio ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Erie to the north, Pennsylvania to the east, West Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Indiana to the ...

.Thomas Parker: The Electric Construction CorporationWolverhampton History and Heritage Website, accessed 29 July 2015. In 1893, the company was in difficulty and was reformed as the Electric Construction Company. In 1894, Parker resigned from the company and set up Thomas Parker Ltd. in Wolverhampton, making electrical equipment. (The company was eventually wound up in 1909.)

Wolverhampton History and Heritage Website, accessed 29 July 2015. In 1892 he designed the high voltage DC system for distributing electricity in the cities of

Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

and Birmingham and in the London area at Charing Cross

Charing Cross ( ) is a junction in Westminster, London, England, where six routes meet. Since the early 19th century, Charing Cross has been the notional "centre of London" and became the point from which distances from London are measured. ...

, Chelsea, Sydenham Sydenham may refer to:

Places Australia

* Sydenham, New South Wales, a suburb of Sydney

** Sydenham railway station, Sydney

* Sydenham, Victoria, a suburb of Melbourne

** Sydenham railway line, the name of the Sunbury railway line, Melbourne un ...

and Shoreditch

Shoreditch is an area in London, England and is located in the London Borough of Hackney alongside neighbouring parts of Tower Hamlets, which are also perceived as part of the area due to historic ecclesiastical links. Shoreditch lies just north ...

. In 1897, he formed the Midland Electric Corporation, the first company in the world to distribute electricity over a wide area.

In London

In 1899 Parker resigned as managing director of Thomas Parker Ltd. He moved to London, where he was consulting engineer to the

In 1899 Parker resigned as managing director of Thomas Parker Ltd. He moved to London, where he was consulting engineer to the Metropolitan Railway

The Metropolitan Railway (also known as the Met) was a passenger and goods railway that served London from 1863 to 1933, its main line heading north-west from the capital's financial heart in the City to what were to become the Middlesex su ...

company, involved in the electrification of the underground railway. The Neasden Power Station

Neasden Power Station was a coal-fired power station built by the Metropolitan Railway for its electrification project. It was opened in December 1904. It was within the site of the current London Underground Neasden Depot.

The station was com ...

was opened in 1904 as part of the project. Parker stayed in London until retirement in 1908.

In 1904 he invented a new smokeless fuel, marketed as Coalite

Coalite is a brand of low-temperature coke used as a smokeless fuel. The title refers to the residue left behind when coal is carbonised at . It was invented by Thomas Parker in 1904. In 1936 the Smoke Abatement Society awarded its inventor a ...

. In 1936 Parker was posthumously awarded a gold medal by the Smoke Abatement Society for this.Thomas Parker: Coalite, a School and a PlaqueWolverhampton History and Heritage Website, accessed 29 July 2015. In 1905 he actively promoted a decimal system of his own creation, based on English weights, measures and currency.

Retirement

In 1908 he retired toIronbridge

Ironbridge is a riverside village in the borough of Telford and Wrekin, Shropshire, England. Located on the bank of the River Severn, at the heart of the Ironbridge Gorge, it lies in the civil parish of The Gorge. Ironbridge developed beside, ...

, near Coalbrookdale, where he purchased Severn House. He had a laboratory and workshop at his home, and in Coalbrookdale he gave a series of lectures on science. In 1910 he bought an ironworks on the local Madeley Court

Madeley Court is a 16th-century country house in Madeley, Shropshire, England which was originally built as a Monastic grange, grange to the medieval Wenlock Priory. It has since been restored as a hotel.

The house is ashlar built in two storey ...

estate, and he ran this company, Court Works Ltd, with his son Charles.

He died, aged 71, of a brain tumour

A brain tumor (sometimes referred to as brain cancer) occurs when a group of cells within the brain turn cancerous and grow out of control, creating a mass. There are two main types of tumors: malignant (cancerous) tumors and benign (non-cancero ...

at home in Ironbridge in 1915, and was buried nearby at St Michael's Church, Madeley.Thomas Parker:Return to CoalbrookdaleWolverhampton History and Heritage Website, accessed 29 July 2015. He had twelve children, of whom nine survived to maturity. His son Charles Henry Parker ran the company that produced Coalite; his son Thomas Hugh Parker was an inventor, building prototype motor cars. A commemorative plaque was unveiled at the former Severn House, now a hotel (The Best Western Valley Hotel), on 10 October 2015.

Madeley Town Council, accessed 28 April 2016.

References

External links

Elwell-Parker

Website of the present-day Elwell-Parker company founded in America in 1893 {{DEFAULTSORT:Parker, Thomas 1843 births 1915 deaths 19th-century English engineers 19th-century English inventors 20th-century English engineers 20th-century English inventors English electrical engineers Deaths from brain cancer in England Engineers from Shropshire English industrialists Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Liberal Party (UK) parliamentary candidates People from Coalbrookdale Sustainable transport pioneers