Thomas Erpingham on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Thomas Erpingham (27 June 1428) was an English soldier and administrator who loyally served three generations of the

"Hundred of South Erpingham: Erpingham".

In ''An Essay Towards A Topographical History of the County of Norfolk. Volume 6''. London: W Miller. p.413. Retrieved 29 July 2021. In 1350, Sir Robert and his son Sir John de Erpingham both witnessed a deed of feoffment by Nicholas de Snyterle, rector of "''Matelask''" ( Matlaske near Erpingham), to Philip Tynker and Maud his wife of a messuage there. Sir John owned a house in

"Preface".

In ''De Antiquis Legibus Liber. Cronica Maiorum et Vicecomitum Londoniarum.'' London: Camden Society. p.clxxix. Retrieved 30 July 2021. In his will, Robert left legacies to all the friars of Norwich. He was buried near the south door of Erpingham church. Sir John de Erpingham succeeded his father Robert, but did not survive him long, dying later that same year on 1 August 1370. He was buried in the church at Erpingham in the east end of the south aisle.

Erpingham was sent back to England to watch over Lancaster's son Henry Bolingbroke and went into his service. In 1390 he was with Bolingbroke's retinue when it crossed the

Erpingham was sent back to England to watch over Lancaster's son Henry Bolingbroke and went into his service. In 1390 he was with Bolingbroke's retinue when it crossed the

In January 1398 a dispute erupted between Bolingbroke and

In January 1398 a dispute erupted between Bolingbroke and  By 27 July Bolingbroke had reached Berkeley, near

By 27 July Bolingbroke had reached Berkeley, near

Henry's

Henry's

When staying in Norwich, Erpingham and his family and servants lived in a large house located between

When staying in Norwich, Erpingham and his family and servants lived in a large house located between

The Erpingham Window

in

Erpingham Dig

Educating people about the story of Sir Thomas Erpingham' at the village of

Sir Thomas Erpingham's speeches (and cues)

in

Record

of the "Particulars of the account of Thomas Erpyngham" from the

House of Lancaster

The House of Lancaster was a cadet branch of the royal House of Plantagenet. The first house was created when King Henry III of England created the Earldom of Lancasterfrom which the house was namedfor his second son Edmund Crouchback in 1267 ...

, including Henry IV and Henry V Henry V may refer to:

People

* Henry V, Duke of Bavaria (died 1026)

* Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor (1081/86–1125)

* Henry V, Duke of Carinthia (died 1161)

* Henry V, Count Palatine of the Rhine (–1227)

* Henry V, Count of Luxembourg (1216–1281 ...

, and whose military career spanned four decades. After the Lancastrian usurpation of the English throne in 1399, his career in their service was transformed as he rose to national prominence, and through his access to royal patronage he acquired great wealth and influence.

Erpingham was born in the English county of Norfolk

Norfolk ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in England, located in East Anglia and officially part of the East of England region. It borders Lincolnshire and The Wash to the north-west, the North Sea to the north and eas ...

, and knighted

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

when a young man. During the reign of Richard II

Richard II (6 January 1367 – ), also known as Richard of Bordeaux, was King of England from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. He was the son of Edward, Prince of Wales (later known as the Black Prince), and Joan, Countess of Kent. R ...

he served under the King's uncle John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster (6 March 1340 – 3 February 1399), was an English royal prince, military leader and statesman. He was the fourth son (third surviving) of King Edward III of England, and the father of King Henry IV of Englan ...

, in Spain and Scotland, and was with Gaunt's son Henry Bolingbroke on crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

in Lithuania

Lithuania, officially the Republic of Lithuania, is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea, bordered by Latvia to the north, Belarus to the east and south, P ...

, Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

and the Holy Land

The term "Holy Land" is used to collectively denote areas of the Southern Levant that hold great significance in the Abrahamic religions, primarily because of their association with people and events featured in the Bible. It is traditionall ...

. Erpingham accompanied Bolingbroke into exile in October 1398, and was with him when he landed at Ravenspur in July 1399 to reclaim his inheritance as Duke of Lancaster

The dukedom of Lancaster is a former Peerage of England, English peerage, created three times in the Middle Ages, which finally merged in the Crown when Henry V of England, Henry V succeeded to the throne in 1413. Despite the extinction of the ...

, after his lands had been forfeited by Richard. Bolingbroke rewarded Erpingham by appointing him as constable of Dover Castle and warden of the Cinque Ports, and after ascending the throne as Henry IV he made him chamberlain of the royal household. Erpingham later helped to suppress the Epiphany Rising and was appointed guardian of Henry's second son Thomas

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the A ...

. He was a member of the Privy Council, acting at one point as marshal of England. He attempted to have Henry le Despenser, the anti-Lancastrian bishop of Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of the county of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. It lies by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. The population of the Norwich ...

, impeached

Impeachment is a process by which a legislative body or other legally constituted tribunal initiates charges against a public official for misconduct. It may be understood as a unique process involving both political and legal elements.

In Eu ...

as a rebel.

On becoming king in 1413, Henry IV's son Henry of Monmouth appointed Erpingham as steward of the royal household. Henry IV's reign had been marked by lawlessness, but Henry V and his administrators proved to be unusually talented, and within twelve months law and order had been re-established throughout England. In 1415 Erpingham was indenture

An indenture is a legal contract that reflects an agreement between two parties. Although the term is most familiarly used to refer to a labor contract between an employer and a laborer with an indentured servant status, historically indentures we ...

d to serve as a knight banneret

A knight banneret, sometimes known simply as banneret, was a medieval knight who led a company of troops during time of war under his own banner (which was square-shaped, in contrast to the tapering standard or the pennon flown by the lower- ...

, and joined Henry's campaign to recover his lost ancestral lands in France and Normandy

Normandy (; or ) is a geographical and cultural region in northwestern Europe, roughly coextensive with the historical Duchy of Normandy.

Normandy comprises Normandy (administrative region), mainland Normandy (a part of France) and insular N ...

. Erpingham presided over the surrender of Harfleur

Harfleur () is a Communes of France, commune in the Seine-Maritime Departments of France, department in the Normandy (administrative region), Normandy Regions of France, region of northern France.

It was the principal seaport in north-western Fr ...

. On 25 October 1415, he commanded the archers in the Battle of Agincourt

The Battle of Agincourt ( ; ) was an English victory in the Hundred Years' War. It took place on 25 October 1415 (Saint Crispin's Day) near Azincourt, in northern France. The unexpected victory of the vastly outnumbered English troops agains ...

, where he was positioned alongside the king.

Erpingham married twice, but both marriages were childless. He was a benefactor to the city of Norwich, where he had built the main cathedral gate which bears his name. He died on 27 June 1428, and was buried in Norwich Cathedral

Norwich Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of the Holy and Undivided Trinity, is a Church of England cathedral in the city of Norwich, Norfolk, England. The cathedral is the seat of the bishop of Norwich and the mother church of the dioc ...

.

Ancestry and early life

Thomas Erpingham was born in about 1357, the son of Sir John de Erpingham ofErpingham

Erpingham ( ) is a village and civil parish in the English county of Norfolk.

Erpingham is located north of Aylsham and north of Norwich, along Scarrow Beck. The parish also includes the nearby village of Calthorpe.

History

Erpingham's na ...

and Wickmere in Norfolk

Norfolk ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in England, located in East Anglia and officially part of the East of England region. It borders Lincolnshire and The Wash to the north-west, the North Sea to the north and eas ...

, England. His grandfather, Sir Robert de Erpingham was recorded as holding Erpingham manor in 1316 and Erpingham and Wickmere in 1346. Sir Robert represented Norfolk in Parliaments during the 1330s and 1340s.Bloomfield, Francis: Parkin, Charles (1807"Hundred of South Erpingham: Erpingham".

In ''An Essay Towards A Topographical History of the County of Norfolk. Volume 6''. London: W Miller. p.413. Retrieved 29 July 2021. In 1350, Sir Robert and his son Sir John de Erpingham both witnessed a deed of feoffment by Nicholas de Snyterle, rector of "''Matelask''" ( Matlaske near Erpingham), to Philip Tynker and Maud his wife of a messuage there. Sir John owned a house in

Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of the county of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. It lies by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. The population of the Norwich ...

in Conisford Lane, now King Street. Thomas, who would have known the house, was possibly born there. The identity of Erpingham's mother is not mentioned by his biographers. In September 1368 he may have travelled with his father to Aquitaine

Aquitaine (, ; ; ; ; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''Aguiéne''), archaic Guyenne or Guienne (), is a historical region of southwestern France and a former Regions of France, administrative region. Since 1 January 2016 it has been part of the administ ...

in the service of Edward the Black Prince

Edward of Woodstock (15 June 1330 – 8 June 1376), known as the Black Prince, was the eldest son and heir apparent of King Edward III of England. He died before his father and so his son, Richard II, succeeded to the throne instead. Edward n ...

.

His grandfather died in 1370, after 8 March but before 1 August, the date of death of the father of Thomas. On 8 March 1370 at Erpingham, Sir Robert de Erpingham and his son Sir John, both signed their names and left seals on a charter of an inescutcheon between eight martlets.Stapleton, Thomas (1846"Preface".

In ''De Antiquis Legibus Liber. Cronica Maiorum et Vicecomitum Londoniarum.'' London: Camden Society. p.clxxix. Retrieved 30 July 2021. In his will, Robert left legacies to all the friars of Norwich. He was buried near the south door of Erpingham church. Sir John de Erpingham succeeded his father Robert, but did not survive him long, dying later that same year on 1 August 1370. He was buried in the church at Erpingham in the east end of the south aisle.

Early career

Early military service

Erpingham served under William Ufford, 2nd Earl of Suffolk in 1372 and was with Suffolk in France the following year. In 1379 he was serving under the Captain of Calais, William Montagu, 2nd Earl of Salisbury. In the summer of 1380 he wasindenture

An indenture is a legal contract that reflects an agreement between two parties. Although the term is most familiarly used to refer to a labor contract between an employer and a laborer with an indentured servant status, historically indentures we ...

d into the retinue

A retinue is a body of persons "retained" in the service of a noble, royal personage, or dignitary; a ''suite'' (French "what follows") of retainers.

Etymology

The word, recorded in English since circa 1375, stems from Old French ''retenue'', ...

of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster (6 March 1340 – 3 February 1399), was an English royal prince, military leader and statesman. He was the fourth son (third surviving) of King Edward III of England, and the father of King Henry IV of Englan ...

, a military leader and the third surviving son of Edward III of England

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring royal authority after t ...

, with whom Salisbury had recently served. Indentured retainers gave their allegiance for life in a personal written contract—conditions of service and payment were agreed, and these were rarely relaxed.

The year Erpingham was knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

ed is unknown, but he is likely to have been at least 21. In June 1380 he was named as 'Sir Thomas' in an order of payment made by Lancaster, the earliest known date at which his knighthood is referred to. The payment, provided by the ducal manor of Gimingham, was for a considerable annual income of £20—it has been estimated that during the 15th century only 12,000 households in England had an income of between £10 and £300. Erpingham was with Lancaster during the English invasion of Scotland in 1385.

Lancaster's determination to rule the Kingdom of Castile

The Kingdom of Castile (; : ) was a polity in the Iberian Peninsula during the Middle Ages. It traces its origins to the 9th-century County of Castile (, ), as an eastern frontier lordship of the Kingdom of León. During the 10th century, the Ca ...

after his marriage to the Castilian princess Constance in 1371 dominated his life for 15 years. In 1386 Richard II of England

Richard II (6 January 1367 – ), also known as Richard of Bordeaux, was King of England from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. He was the son of Edward the Black Prince, Edward, Prince of Wales (later known as the Black Prince), and Jo ...

agreed to release the funds needed for Lancaster to lead a Castilian campaign. Lancaster's royal status gave him a prominence in affairs of state that created tension between him and Richard, and the cost of the Castilian campaign was seen by the King's advisers as a price worth paying for the political freedom Richard would gain from Lancaster's absence.

Erpingham was with Lancaster when his army set sail from Plymouth

Plymouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Devon, South West England. It is located on Devon's south coast between the rivers River Plym, Plym and River Tamar, Tamar, about southwest of Exeter and ...

in July 1386. It landed at Brest, France

Brest (; ) is a port, port city in the Finistère department, Brittany (administrative region), Brittany. Located in a sheltered bay not far from the western tip of a peninsula and the western extremity of metropolitan France, Brest is an impor ...

, and temporarily relieved the besieged English garrison. After leaving Brest the army arrived at A Coruña

A Coruña (; ; also informally called just Coruña; historical English: Corunna or The Groyne) is a city and municipality in Galicia, Spain. It is Galicia's second largest city, behind Vigo. The city is the provincial capital of the province ...

, and went on to bring Galicia under English control. John I of Portugal

John I ( WP:IPA for Portuguese, �uˈɐ̃w̃ 11 April 1357 – 14 August 1433), also called John of Aviz, was King of Portugal from 1385 until his death in 1433. He is recognized chiefly for his role in Portugal's victory in 1383–85 crisi ...

joined with Lancaster in March 1387, but because of a lack of food for their animals, and the successful defensive tactics employed by the Castilians, their campaign was abandoned after six weeks. In 1388, Erpingham participated before Charles VI of France

Charles VI (3 December 136821 October 1422), nicknamed the Beloved () and in the 19th century, the Mad ( or ''le Fou''), was King of France from 1380 until his death in 1422. He is known for his mental illness and psychosis, psychotic episodes t ...

in a jousting

Jousting is a medieval and renaissance martial game or hastilude between two combatants either on horse or on foot. The joust became an iconic characteristic of the knight in Romantic medievalism.

The term is derived from Old French , ultim ...

tournament at Montereau, his adversary being Sir John de Barres. As related by the French chronicler Jean Froissart

Jean Froissart ( Old and Middle French: ''Jehan''; sometimes known as John Froissart in English; – ) was a French-speaking medieval author and court historian from the Low Countries who wrote several works, including ''Chronicles'' and ''Meli ...

, half way through the tournament, Erpingham was struck violently on his shield by his opponent, and was knocked off his horse. Stunned by the blow, he managed to recover and continue the joust, "to the satisfaction of the king and his lords".

Erpingham was sent back to England to watch over Lancaster's son Henry Bolingbroke and went into his service. In 1390 he was with Bolingbroke's retinue when it crossed the

Erpingham was sent back to England to watch over Lancaster's son Henry Bolingbroke and went into his service. In 1390 he was with Bolingbroke's retinue when it crossed the English Channel

The English Channel, also known as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates Southern England from northern France. It links to the southern part of the North Sea by the Strait of Dover at its northeastern end. It is the busi ...

with the intention of joining Duke Louis II of Bourbon in a siege of the Tunisian port of Mahdia

Mahdia ( ') is a Tunisian coastal city with 76,513 inhabitants, south of Monastir, Tunisia, Monastir and southeast of Sousse.

Mahdia is a provincial centre north of Sfax. It is important for the associated fish-processing industry, as well as w ...

on a crusading expedition via Marseille

Marseille (; ; see #Name, below) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Bouches-du-Rhône and of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region. Situated in the ...

. The expedition was abandoned when Charles VI refused him permission to travel through France. Bolingbroke then went on a crusade in Lithuania. Erpingham, one of the most trusted and experienced of Lancaster's men, belonged to what the historian Douglas Biggs describes as "the 'adult' portion of Henry's force"—older men who were probably sent by Lancaster to guide and protect his son. The "crusade" resulted in an unsuccessful siege of Vilnius

Vilnius ( , ) is the capital of and List of cities in Lithuania#Cities, largest city in Lithuania and the List of cities in the Baltic states by population, most-populous city in the Baltic states. The city's estimated January 2025 population w ...

and the capture of Lithuanian women and children, who were then converted to Christianity. It is not known if Erpingham was present with Bolingbroke at the siege.

Erpingham was with Bolingbroke when he returned unnecessarily to Prussia in July 1392—a peace was being made in Lithuania between its ruler, Władysław II Jagiełło

Jogaila (; 1 June 1434), later Władysław II Jagiełło (),Other names include (; ) (see also Names and titles of Władysław II Jagiełło) was Grand Duke of Lithuania beginning in 1377 and starting in 1386, becoming King of Poland as well. ...

, and his cousin Vytautas

Vytautas the Great (; 27 October 1430) was a ruler of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. He was also the prince of Grodno (1370–1382), prince of Lutsk (1387–1389), and the postulated king of the Hussites.

In modern Lithuania, Vytautas is revere ...

, and the crusaders who had supported Vytautas had already left. Bolingbroke and his reduced retinue journeyed through Europe and the Near East

The Near East () is a transcontinental region around the Eastern Mediterranean encompassing the historical Fertile Crescent, the Levant, Anatolia, Egypt, Mesopotamia, and coastal areas of the Arabian Peninsula. The term was invented in the 20th ...

, visiting Prague, Vienna, Corfu

Corfu ( , ) or Kerkyra (, ) is a Greece, Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands; including its Greek islands, small satellite islands, it forms the margin of Greece's northwestern frontier. The island is part of the Corfu (regio ...

, and the Holy Land

The term "Holy Land" is used to collectively denote areas of the Southern Levant that hold great significance in the Abrahamic religions, primarily because of their association with people and events featured in the Bible. It is traditionall ...

. It is thought that it was in Italy that Erpingham obtained the silk for the chasuble

The chasuble () is the outermost liturgical vestment worn by clergy for the celebration of the Eucharist in Western-tradition Christian churches that use full vestments, primarily in Roman Catholic, Anglican, and Lutheran churches. In the Eastern ...

which bears his name, now in the Victoria and Albert Museum

The Victoria and Albert Museum (abbreviated V&A) in London is the world's largest museum of applied arts, decorative arts and design, housing a permanent collection of over 2.8 million objects. It was founded in 1852 and named after Queen ...

.

Revolution of 1399

The historianHelen Castor

Helen Ruth Castor (born 4 August 1968) is a British historian of the medieval and Tudor period and a BBC broadcaster. She taught history at the University of Cambridge and is the author of books including '' Blood and Roses'' (2004) and ''She-W ...

has described the Lancastrian presence in East Anglia

East Anglia is an area of the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire, with parts of Essex sometimes also included.

The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, ...

as a "disparate collection” that lacked coherence or a single identity. Erpingham rose to become the most important of Lancaster's retainers in the region. He was appointed to a commission of peace, and given powers to preserve order in Norfolk in the aftermath of the Peasants' Revolt

The Peasants' Revolt, also named Wat Tyler's Rebellion or the Great Rising, was a major uprising across large parts of England in 1381. The revolt had various causes, including the socio-economic and political tensions generated by the Black ...

in the summer of 1381. He had a part in supervising the defence of Norfolk in 1385, when a French invasion seemed imminent. In 1396 Lancaster granted him the legal right to use the land within the hundred

100 or one hundred (Roman numerals, Roman numeral: C) is the natural number following 99 (number), 99 and preceding 101 (number), 101.

In mathematics

100 is the square of 10 (number), 10 (in scientific notation it is written as 102). The standar ...

of South Erpingham, a reward for his loyal service to the Duchy of Lancaster.

In January 1398 a dispute erupted between Bolingbroke and

In January 1398 a dispute erupted between Bolingbroke and Thomas de Mowbray, 1st Duke of Norfolk

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the ...

, after Mowbray had attempted to ambush and kill Lancaster, and which the King ordered be settled by a trial by battle between the two men. During the five months before 16 September, the day the trial was due to take place, Bolingbroke travelled throughout England on a tour of the Lancastrian lands. Richard stopped the contest as it was about to begin and banished Bolingbroke from the kingdom for ten years, and exiled Mowbray for life. Those assembled were told that the trial had been stopped to avoid dishonouring the loser and to prevent a feud

A feud , also known in more extreme cases as a blood feud, vendetta, faida, clan war, gang war, private war, or mob war, is a long-running argument or fight, often between social groups of people, especially family, families or clans. Feuds begin ...

from arising, but chroniclers (writing after Henry IV's accession) considered Richard's decision an act of revenge. Bolingbroke, as one of the five Lords Appellant

The Lords Appellant were a group of nobles in the reign of Richard II of England, King Richard II, who, in 1388, sought to impeach five of the King's favourites in order to restrain what was seen as tyrannical and capricious rule. The word ''appel ...

, had rebelled in November 1387; for a year they maintained Richard as a figurehead

In politics, a figurehead is a practice of who ''de jure'' (in name or by law) appears to hold an important and often supremely powerful title or office, yet '' de facto'' (in reality) exercises little to no actual power. This usually means that ...

with little actual power.

Erpingham was one of 17 named companions who volunteered to accompany Henry Bolingbroke into exile. He entrusted his lands and property to Sir Robert Berney and others. The party headed for Paris, where they were welcomed by Charles VI and presented with lavish gifts. Following the death of his father on 3 February 1399, Bolingbroke's inheritance was confiscated by Richard, and his banishment was increased by the King to life. On 17 June 1399, Erpingham witnessed a secret pact made in Paris between Bolingbroke and Louis I, Duke of Orléans

Louis I (13 March 1372 – 23 November 1407) was Duke of Orléans from 1392 to his death in 1407. He was also Duke of Touraine (1386–1392), Count of Valois (1386?–1406) Blois (1397–1407), Angoulême (1404–1407), ...

, the brother of Charles VI, stating that as allies they would support each other against each other's enemies—the kings of England and France excepted.

Erpingham was one of Bolingbroke's supporters who landed with him at Ravenspur, probably at the end of June 1399. Whilst Bolingbroke was gaining support for his cause to restore his rightful inheritance of the Duchy of Lancaster as he moved across northern and central England, Richard was delayed in Ireland. He eventually found ships to cross the Irish Sea

The Irish Sea is a body of water that separates the islands of Ireland and Great Britain. It is linked to the Celtic Sea in the south by St George's Channel and to the Inner Seas off the West Coast of Scotland in the north by the North Ch ...

, and reached Wales by around 24 July. Realising the strength of the threat posed by his rival, he deserted his court

A court is an institution, often a government entity, with the authority to adjudicate legal disputes between Party (law), parties and Administration of justice, administer justice in Civil law (common law), civil, Criminal law, criminal, an ...

and moved across country with a small group of followers.

By 27 July Bolingbroke had reached Berkeley, near

By 27 July Bolingbroke had reached Berkeley, near Bristol

Bristol () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city, unitary authority area and ceremonial county in South West England, the most populous city in the region. Built around the River Avon, Bristol, River Avon, it is bordered by t ...

, where he had a meeting with Richard's uncle the Duke of York

Duke of York is a title of nobility in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. Since the 15th century, it has, when granted, usually been given to the second son of List of English monarchs, English (later List of British monarchs, British) monarchs ...

. At Berkeley, York deserted the King's cause and joined Bolingbroke. Shortly afterwards, Erpingham arrested Henry le Despenser, bishop of Norwich and one of the few remaining supporters of Richard prepared to resist Bolingbroke.

Richard had reached Conwy Castle

Conwy Castle (; ) is a fortification in Conwy, located in North Wales. It was built by Edward I of England, Edward I, during his Conquest of Wales by Edward I, conquest of Wales, between 1283 and 1287. Constructed as part of a wider project to ...

when Chester

Chester is a cathedral city in Cheshire, England, on the River Dee, Wales, River Dee, close to the England–Wales border. With a built-up area population of 92,760 in 2021, it is the most populous settlement in the borough of Cheshire West an ...

fell to Bolingbroke on 5 August. The King was persuaded by the Earl of Northumberland

The title of Earl of Northumberland has been created several times in the Peerage of England and of Great Britain, succeeding the title Earl of Northumbria. Its most famous holders are the House of Percy (''alias'' Perci), who were the most po ...

to leave Conwy and travel to Rhuddlan Castle, but during the journey his party was ambushed and he was taken prisoner. According to a French chronicle

A chronicle (, from Greek ''chroniká'', from , ''chrónos'' – "time") is a historical account of events arranged in chronological order, as in a timeline. Typically, equal weight is given for historically important events and local events ...

, the ambush was devised by Northumberland and carried out by his men, led by Erpingham. When Richard saw armed men everywhere, Northumberland's plans were revealed to him, and: "As he spoke, Erpingham came up with all the people of the Earl, his trumpets sounding aloud." Taken to London under armed guard and kept under Erpingham's custody in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic citadel and castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamle ...

, Richard was given no option by Bolingbroke and his representatives—including Erpingham—but to relinquish the throne.

Erpingham was given two important positions at court by Bolingbroke. He was made lord warden and constable of Dover Castle as early as 21 August, and appointed to be chamberlain of the royal household after Henry's accession, a post which made him the head of the royal household with overall responsibility for the arrangement of Henry's domestic affairs, and which he held until 1404. His appointment as lord warden and constable involved the command of a garrison at the castle, and gave Erpingham a position in the King's council when strategic matters were discussed; as constable, he was paid over £300 a year.

Career under Henry IV

Henry's

Henry's coronation

A coronation ceremony marks the formal investiture of a monarch with regal power using a crown. In addition to the crowning, this ceremony may include the presentation of other items of regalia, and other rituals such as the taking of special v ...

took place on 13 October 1399 at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

. As part of the ceremony, Erpingham carried one of the King's swords during the procession to the abbey. He was one of 11 men who petitioned Henry in person to have Richard killed. He was a commander in the army that suppressed the Epiphany Rising of 13991400, led by the (the disparaging term given to a large group of noblemen, many of whom had received titles from Richard). Erpingham supervised the execution of two of the leading rebels, Sir Thomas Blount and Sir Benedict Kely. As Blount watched his own bowels being burnt before him, he cursed Erpingham for being a "false traitor":

Henry rewarded Erpingham with the custody for life of a house called 'le Newe Inne' in London. The following year, Erpingham was appointed as guardian of the King's second son, Thomas, Duke of Clarence, and in about 1401 he was appointed to the Order of the Garter

The Most Noble Order of the Garter is an order of chivalry founded by Edward III of England in 1348. The most senior order of knighthood in the Orders, decorations, and medals of the United Kingdom, British honours system, it is outranked in ...

. He acted briefly as steward of the royal household

The Lord Steward or Lord Steward of the Household is one of the three Great Officers of the Household of the British monarch. He is, by tradition, the first great officer of the Court and he takes precedence over all other officers of the househ ...

the same year and became acting marshal of England in October. In July 1407 the Duke of Burgundy

Duke of Burgundy () was a title used by the rulers of the Duchy of Burgundy, from its establishment in 843 to its annexation by the Crown lands of France, French crown in 1477, and later by members of the House of Habsburg, including Holy Roman E ...

was authorised to negotiate a permanent peace settlement between the French and the English. A mission led by Erpingham went to Paris the following month, and were lavishly entertained by members of the French king's council.

Despite the military nature of the office of constable of Dover, Erpingham took little part in the warfare of the early years of Henry IV's reign, and he generally remained at court. He campaigned in Scotland in August 1400, when Henry made a futile attempt to make the Scots acknowledge him as king of England and pay him homage.

According to one tradition, Erpingham was a supporter of John Wycliffe

John Wycliffe (; also spelled Wyclif, Wickliffe, and other variants; 1328 – 31 December 1384) was an English scholastic philosopher, Christianity, Christian reformer, Catholic priest, and a theology professor at the University of Oxfor ...

's English translation of the Bible, which was considered heretical

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, particularly the accepted beliefs or religious law of a religious organization. A heretic is a proponent of heresy.

Heresy in Christianity, Judai ...

. Supposedly, Erpingham was spared from persecution by the Church because he was favoured by Henry IV, and so merely paid a fine, which financed the construction of the Erpingham Gate. The historian Veronica Sekules considers it unlikely that Erpingham supported Wycliffe, and suggests that if he had such a dispute with the Church, it was more likely over Erpingham's arrest of Despenser.

Power and influence in Norfolk

Sir Thomas Erpingham was one of Henry IVs closest associates, and after 1399, influence in Norfolk shifted from Despenser to Erpingham and his friends. Due to his local connections, his links with theDuchy of Lancaster

The Duchy of Lancaster is an estate of the British sovereign. The estate has its origins in the lands held by the medieval Dukes of Lancaster, which came under the direct control of the monarch when Henry Bolingbroke, the then duke of Lancast ...

and his position in the centre of government, Erpingham held a prominent position in East Anglian society; he was named to every commission of the peace in Norfolk during the reign of Henry IV. During the 1400s, Erpingham's authority in north Norfolk was extended to other parts of the county and into Suffolk. Gentry from East Anglia who were associated with Erpingham benefited from his powerful position at court: Sir John Strange of Hunstanton

Hunstanton (sometimes pronounced ) is a seaside resort, seaside town in Norfolk, England, which had a population of 4,229 at the 2011 Census. It faces west across The Wash. Hunstanton lies 102 miles (164 km) north-north-east of London an ...

became controller of the royal household in 1408; Sir Robert Gurney of Gunton became Erpingham's deputy at Dover Castle

Dover Castle is a medieval castle in Dover, Kent, England and is Grade I listed. It was founded in the 11th century and has been described as the "Key to England" due to its defensive significance throughout history. Some writers say it is the ...

in 1400; and John Winter of Barningham became controller of Prince Henry's household in 1403. Other beneficiaries of Erpingham's friendship included Sir Ralph Shelton, John Payn, and John Raynes of Overstrand, who succeeded Payn as the constable

A constable is a person holding a particular office, most commonly in law enforcement. The office of constable can vary significantly in different jurisdictions. ''Constable'' is commonly the rank of an officer within a police service. Other peo ...

of Norwich Castle

Norwich Castle is a medieval royal fortification in the city of Norwich, in the English county of Norfolk. William the Conqueror (1066–1087) ordered its construction in the aftermath of the Norman Conquest of England. The castle was used as a ...

in 1402.

The principal citizens of Norwich had become disillusioned with Richard II's policies, the city having lost its charter

A charter is the grant of authority or rights, stating that the granter formally recognizes the prerogative of the recipient to exercise the rights specified. It is implicit that the granter retains superiority (or sovereignty), and that the ...

in 1388 when it supported the Lords Appellant.

Despenser had remained within his diocese

In Ecclesiastical polity, church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided Roman province, prov ...

after Henry's coronation, but his nephew Thomas Despenser, 1st Earl of Gloucester had been executed for his part in the Epiphany Rising. Erpingham attempted to have Despenser impeached

Impeachment is a process by which a legislative body or other legally constituted tribunal initiates charges against a public official for misconduct. It may be understood as a unique process involving both political and legal elements.

In Eu ...

for actively supporting the rebels; at Erpingham's suggestion, Norwich petitioned Henry with charges against Despenser, which were presented to the King by Erpingham.

At Despenser's hearing in London, Erpingham was publicly congratulated by the King for his loyalty to the Crown. Despenser was forced to accept Henry's authority and publicly rebuked; he was later pardoned. Henry awarded the city a new charter, and Norwich showed its gratitude by showering Erpingham with lavish gifts "for bearing his word to the King for the honour of the city and for having his counsel". The city authorities cooperated with him as an important member of Henry's inner circle.

Career under Henry V

Henry IV died at Westminster on 30 March 1413, and was succeeded by his sonHenry of Monmouth

Henry V (16 September 1386 – 31 August 1422), also called Henry of Monmouth, was King of England from 1413 until his death in 1422. Despite his relatively short reign, Henry's outstanding military successes in the Hundred Years' War against ...

, the Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales (, ; ) is a title traditionally given to the male heir apparent to the History of the English monarchy, English, and later, the British throne. The title originated with the Welsh rulers of Kingdom of Gwynedd, Gwynedd who, from ...

. Monmouth had replaced Erpingham as warden of the Cinque Ports in 1409, but relationships between the two men remained good, and after the coronation on 9 April 1413, Erpingham was appointed steward of the household, a post he held until at least 1415. After Henry IV's reign, which had been marked by banditry and rioting, Henry V acted quickly to restore law and order throughout the country. This was achieved within a year. Henry's administrators—Erpingham included—were unusually talented, and order was maintained in England throughout his reign.

Henry's great-grandfather Edward III had lost Aquitaine in 1337 when it was confiscated from the English by Philip VI of France

Philip VI (; 1293 – 22 August 1350), called the Fortunate (), the Catholic (''le Catholique'') and of Valois (''de Valois''), was the first king of France from the House of Valois, reigning from 1328 until his death in 1350. Philip's reign w ...

, and as a grandson of Philip IV of France

Philip IV (April–June 1268 – 29 November 1314), called Philip the Fair (), was King of France from 1285 to 1314. Jure uxoris, By virtue of his marriage with Joan I of Navarre, he was also King of Navarre and Count of Champagne as Philip&n ...

, Edward had a claim to the French throne. In November 1414, Henry launched a campaign to recover Aquitaine and France. It was an effective way of establishing his authority as king at the start of his reign. Strategic planning for the expedition in February 1415 involved discussions with Erpingham and other soldiers in Henry's inner circle, part of what the historian Anne Curry

Anne Elizabeth Curry (who publishes as Anne Curry and A. E. Curry; born 27 May 1954) is an English historian and Officer of Arms.

Career

Curry is Emeritus Professor of Medieval history at the University of Southampton and was dean of the F ...

describes as the King's "strong infrastructure and amply supply of manpower". Erpingham was indentured to serve as a knight banneret

A knight banneret, sometimes known simply as banneret, was a medieval knight who led a company of troops during time of war under his own banner (which was square-shaped, in contrast to the tapering standard or the pennon flown by the lower- ...

. His retinue, which mustered on heathland

A heath () is a shrubland habitat found mainly on free-draining infertile, acidic soils and is characterised by open, low-growing woody vegetation. Moorland is generally related to high-ground heaths with—especially in Great Britain—a coole ...

outside Southampton

Southampton is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Hampshire, England. It is located approximately southwest of London, west of Portsmouth, and southeast of Salisbury. Southampton had a population of 253, ...

where they obtained provisions, consisted of two knights, 17 squires and 60 archers.

Participation at Harfleur and Agincourt

Erpingham crossed over from England toNormandy

Normandy (; or ) is a geographical and cultural region in northwestern Europe, roughly coextensive with the historical Duchy of Normandy.

Normandy comprises Normandy (administrative region), mainland Normandy (a part of France) and insular N ...

with Henry's army on 11 August 1415. The King's ship reached the mouth of the River Seine

The Seine ( , ) is a river in northern France. Its drainage basin is in the Paris Basin (a geological relative lowland) covering most of northern France. It rises at Source-Seine, northwest of Dijon in northeastern France in the Langres p ...

on 13 August, and the army landed from Harfleur

Harfleur () is a Communes of France, commune in the Seine-Maritime Departments of France, department in the Normandy (administrative region), Normandy Regions of France, region of northern France.

It was the principal seaport in north-western Fr ...

, a landing point likely to have been decided on beforehand. Erpingham's men were present during the siege of the town, and on 22 September he led the procession to the walls

Walls may refer to:

*The plural of wall, a structure

* Walls (surname), a list of notable people with the surname

Places

* Walls, Louisiana, United States

* Walls, Mississippi, United States

*Walls, Ontario

Perry is a township (Canada), ...

and presided over the truce that led to its surrender. The English army then marched towards Calais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a French port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Calais is the largest city in Pas-de-Calais. The population of the city proper is 67,544; that of the urban area is 144,6 ...

, shadowed by the French, who forced them to divert away from the coast. The English successfully forded the River Somme

The Somme ( , ; ) is a river in Picardy, northern France.

The river is in length, from its source in the high ground of the former at Fonsomme near Saint-Quentin, to the Bay of the Somme, in the English Channel. It lies in the geologica ...

at Voyennes; two days' march short of Calais, they were blocked by the French near Agincourt.

Erpingham was one of the middle-aged English commanders on the field at Agincourt, and at 60 was one of the oldest men present. Although having never experienced a pitched battle before, he had taken part in lesser actions and, as noted by Curry, was "undoubtedly one of the most experienced soldiers present" at Agincourt. He is not mentioned in any contemporaneous English versions of the battle, but three French chroniclers, Jean de Wavrin, Enguerrand de Monstrelet and Jean Le Fèvre, all give detailed descriptions of his role in the battle. The three main divisions (or ' battles') of the English army were commanded by Henry and two veteran soldiers: the rearguard

A rearguard or rear security is a part of a military force that protects it from attack from the rear, either during an advance or Withdrawal (military), withdrawal. The term can also be used to describe forces protecting lines, such as Line of c ...

(to the right of the King) was led by Thomas Camoys, 1st Baron Camoys; and the vanguard

The vanguard (sometimes abbreviated to van and also called the advance guard) is the leading part of an advancing military formation. It has a number of functions, including seeking out the enemy and securing ground in advance of the main force.

...

(on the King's left) was led by Edward, Duke of York.

The battle

On 25 October, the day of the battle, the English army was in position by dawn. With both of its flanks protected by the woods of Tramecourt and Azincourt, the army consisted of 5,000 archers and 800 dismountedmen-at-arms

A man-at-arms was a soldier of the High Medieval to Renaissance periods who was typically well-versed in the use of arms and served as a fully-armoured heavy cavalryman. A man-at-arms could be a knight, or other nobleman, a member of a kni ...

—in proportion to the number of men-at-arms present, the number of English archers was high. Because of the authority his seniority would carry, Erpingham was given command of the archers. The men-at-arms were positioned fours ranks deep in the centre of the gap between the two woods. Most of the archers were positioned on the flanks of the men-at-arms, but a few archers were placed amongst them, and 200 were hidden in a clearing in the Tramecourt woods, close to the French lines. Each archer had a stake, double-pointed and long, which was planted deep into the ground and—according to an eye-witness account—"sloping towards the enemy higher than a man's waist above the ground". The stakes gave protection against a charge by the French cavalry.

After the French army failed to attack, Erpingham was ordered to warn the army that it was about to advance to within bowshot of the French. He threw his baton upwards as a signal to advance, and commanded "Now strike!". Erpingham's strong Norfolk accent may have caused the French to mishear him, as some chroniclers recorded the command as "''Nestroque''". He then dismounted and moved with his banner to join the King, where he remained during the rest of the battle.

When the English advanced with a great shout, the French responded by beginning their own advance, each army moving roughly the same distance. The English paused and the main body of archers replanted their stakes. They then began to continuously discharge their arrows, which signalled the concealed archers to start firing into the French flanks. The French plan was to use mounted men-at-arms to overcome the English archers, leaving the battles and the men in the wings to attack their heavily outnumbered English counterparts. This plan failed when the cavalry were halted by the storm of arrow fire and the stakes planted by the archers; their retreat was disrupted by the advancing French foot soldiers. The chaos that ensued allowed the English men-at-arms to penetrate the French battles.

The ensuing was the most important part of the battle. Once the men-at-arms in the two armies engaged, the English archers fired into the flanks of the French. Evidence suggests the English vanguard, led by York, who was killed, bore most of the fighting. Advancing through deep mud, the French were exhausted when they reached the English. Those killed or knocked down at the front hindered others behind them, causing men to pile up. The immobilised French were killed where they stood, the English suffering far fewer casualties. Any of the French attempting to retreat were blocked by their advancing comrades; if they tried to move to the flanks they were targets for the English archers. At this stage in the , the archers abandoned their bows and attacked the flanks of the mass of the French with any weapons to hand. This, and their failing position to their front, caused the French to break, and many were cut down or captured by pursuing English archers and men-at-arms. Not all the French had engaged in the fighting and only the vanguard had been defeated. When much of the main French battle were destroyed by the English men-at-arms and the re-armed archers firing into them, the largely leaderless French army withdrew from the field, except for a group of 600 men who were killed or captured when they charged the English.

Aftermath of the battle

After the battle, Henry's army marched to the Englishenclave

An enclave is a territory that is entirely surrounded by the territory of only one other state or entity. An enclave can be an independent territory or part of a larger one. Enclaves may also exist within territorial waters. ''Enclave'' is so ...

of the Pale of Calais

The Pale of Calais was a territory in northern France ruled by the monarchs of England from 1347 to 1558. The area, which centred on Calais, was taken following the Battle of Crécy in 1346 and the subsequent Siege of Calais (1346–47), Siege o ...

, embarked from Calais on 16 November and returned to England. Erpingham was among 300 men-at arms—which included four baron

Baron is a rank of nobility or title of honour, often Hereditary title, hereditary, in various European countries, either current or historical. The female equivalent is baroness. Typically, the title denotes an aristocrat who ranks higher than ...

s and 22 knights—and 900 archers who garrisoned the town over the winter. The seniority of the men-at-arms was a reflection of how important it was to Henry that the town was not lost to the French.

On his return to England, Erpingham's reward for the services he rendered had during the war included the farm of Lessingham manor and an annuity

In investment, an annuity is a series of payments made at equal intervals based on a contract with a lump sum of money. Insurance companies are common annuity providers and are used by clients for things like retirement or death benefits. Examples ...

from the King of 50 marks

Marks may refer to:

Business

* Mark's, a Canadian retail chain

* Marks & Spencer, a British retail chain

* Collective trade marks

A collective trademark, collective trade mark, or collective mark is a trademark owned by an organization (such ...

. In July 1416, in his capacity as the steward of the royal household, he travelled back to Calais with John Wakering, the bishop of Norwich. There they welcomed the Duke of Burgundy, before his meeting with King Henry.

Personal life

When staying in Norwich, Erpingham and his family and servants lived in a large house located between

When staying in Norwich, Erpingham and his family and servants lived in a large house located between Norwich Cathedral

Norwich Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of the Holy and Undivided Trinity, is a Church of England cathedral in the city of Norwich, Norfolk, England. The cathedral is the seat of the bishop of Norwich and the mother church of the dioc ...

and the River Wensum

The River Wensum is a chalk river in Norfolk, England, Norfolk, England and a tributary of the River Yare, despite being the larger of the two rivers. The river is a biological Site of Special Scientific Interest and Special Area of Conservatio ...

, with his land going down to the river. The house was acquired from Sir Robert Berney in 1409. Known variously as 'Berney's Inn', 'the Erpingham' or 'Calthorpe's House', it was only accurately located in 1981. No remains survive, although it was a major source of employment for the local area during the time that it was occupied by Erpingham. It was inherited by his niece. In the 17th century, the house and its associated land was subdivided and built upon.

Erpingham's connections with the Lancastrians and his increasing wealth led to his acquisition of lands, rents and services in Norfolk, Suffolk and Essex

Essex ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East of England, and one of the home counties. It is bordered by Cambridgeshire and Suffolk to the north, the North Sea to the east, Kent across the Thames Estuary to the ...

, manors sometimes being held in joint possession with his neighbours or relatives. Curry lists over 40 manors he held during his life, some permanently: three were inherited from his father, such as the manor at Erpingham; seven came to him during the 1370s and 1380s; eight manors were given to him in 1399 by Henry IV and a further seven were acquired that year by other means; another seven were acquired during the 1400s; and he purchased twelve manors from 1410 to 1421. He also lost the tenure

Tenure is a type of academic appointment that protects its holder from being fired or laid off except for cause, or under extraordinary circumstances such as financial exigency or program discontinuation. Academic tenure originated in the United ...

of some of his lands, a common occurrence at the time when manors were awarded 'for life'; the hundred, which included his home village, was lost in 1398, when King Richard gave to Katherine Swynford

Katherine Swynford, Duchess of Lancaster (born Katherine de Roet, – 10 May 1403) was the third wife of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, the fourth (but third surviving) son of King Edward III.

Daughter of a knight from County of Hainaut, Ha ...

, third wife of the Duke of Lancaster, "the manors of Erpingham and Wyckmere, and of all lands, rents, services, villein

A villein is a class of serfdom, serf tied to the land under the feudal system. As part of the contract with the lord of the manor, they were expected to spend some of their time working on the lord's fields in return for land. Villeins existe ...

s with their villeinages etc. there and in all other towns in Norfolk sometime of Robert Erpingham knight". In 1407 Berney helped Erpingham to buy the manor at Blickling

Blickling is a village and civil parish in the Broadland district of the English county of Norfolk.

Blickling is located north-west of Aylsham and north of Norwich. Most of the village is located within the Blickling Estate, which has been ow ...

. His family sold Blickling to the soldier Sir John Fastolf

Sir John Fastolf (6 November 1380 – 5 November 1459) was a late medieval English soldier, landowner, and knight who fought in the Hundred Years' War from 1415 to 1439, latterly as a senior commander against Joan of Arc, among others. He h ...

in 1431.

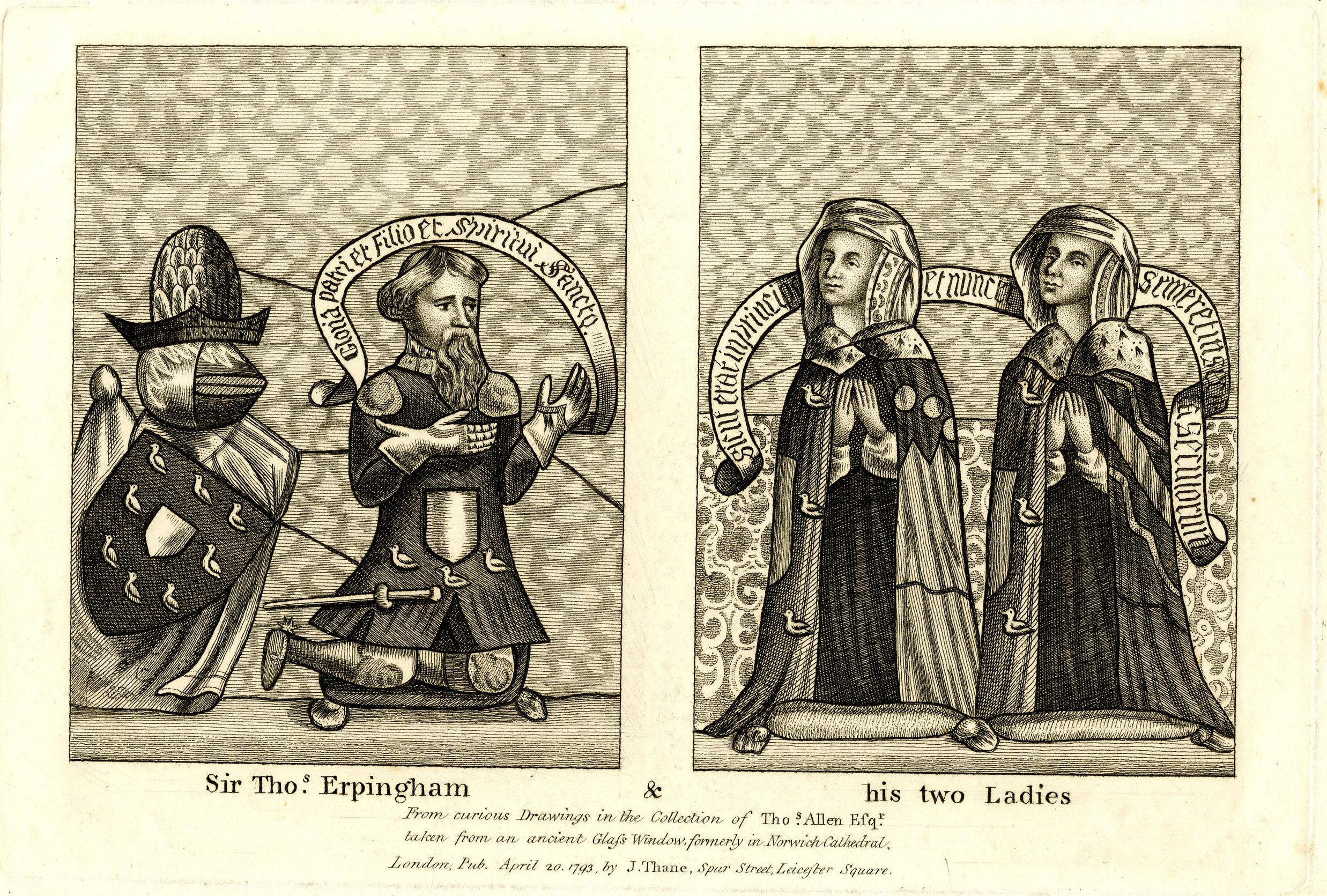

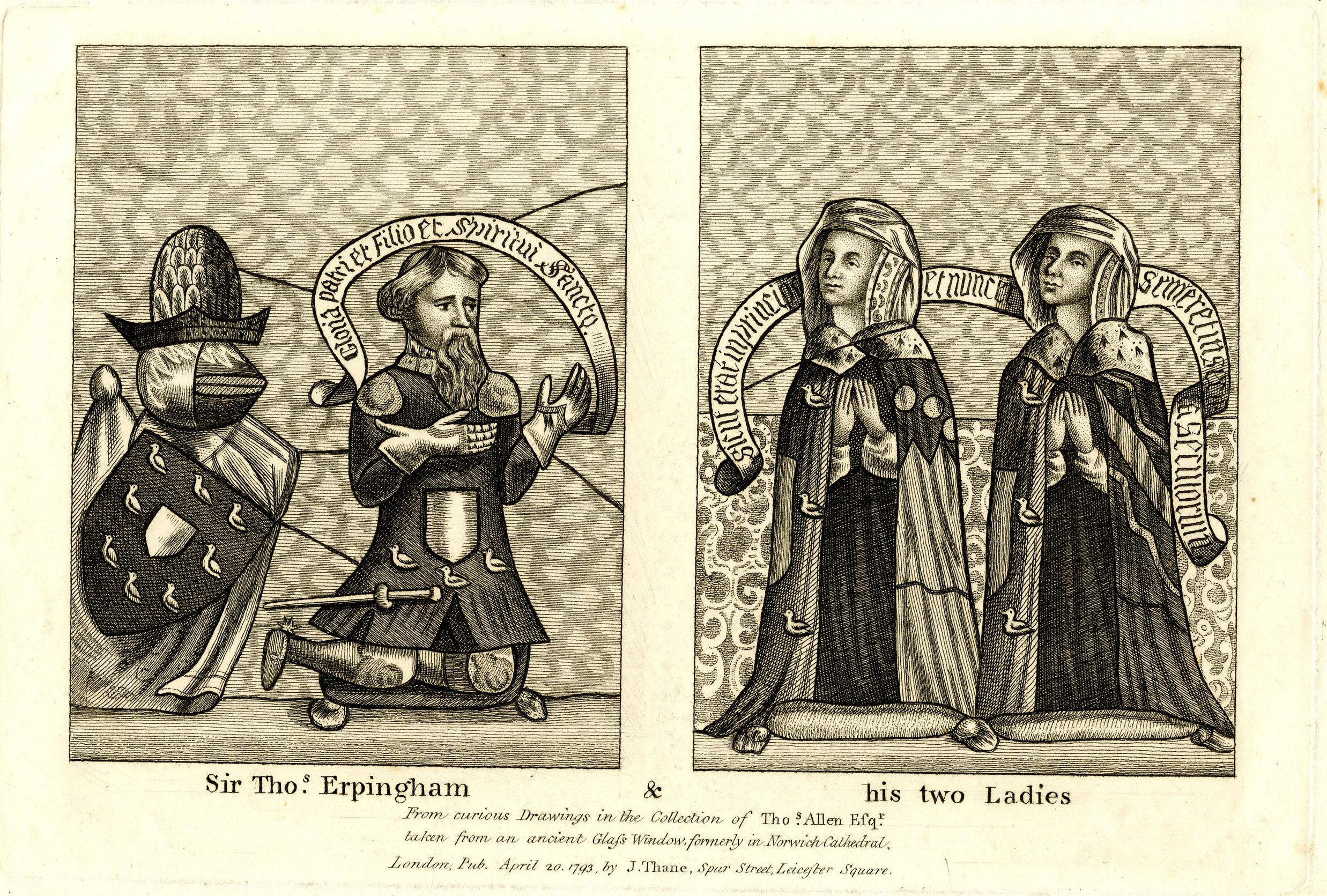

Erpingham married Joan Clopton, the daughter of Sir William Clopton of Clopton, Suffolk, sometime before 1389; Erpingham was widowed in 1404. His second marriage was to Joan Walton, the daughter of Sir Richard Walton, and widow of Sir John Howard, who died in 1409 or 1410. Joan died in 1425. Evidence that Erpingham was twice married comes in part from a window opposite the chantry of Norwich Cathedral, which once displayed him and his two wives, as well as church records, which state he was buried with both of his wives. Both marriages were childless.

Erpingham had a profound influence on the careers of the two sons of his sister Julian, who married Sir William Phelip (or Philip) of Dennington. Erpingham's position in court helped the elder son William

William is a masculine given name of Germanic languages, Germanic origin. It became popular in England after the Norman Conquest, Norman conquest in 1066,All Things William"Meaning & Origin of the Name"/ref> and remained so throughout the Middle ...

to become a member of Henry IV's personal household; William's brother John held a similar position at the court of Henry of Monmouth. The brothers remained closely attached to their uncle. William and Erpingham were often recorded as co-feoffees of estates in East Anglia, and William stood surety

In finance, a surety , surety bond, or guaranty involves a promise by one party to assume responsibility for the debt obligation of a borrower if that borrower defaults. Usually, a surety bond or surety is a promise by a person or company (a ''sure ...

for his uncle at the Exchequer

In the Civil Service (United Kingdom), civil service of the United Kingdom, His Majesty's Exchequer, or just the Exchequer, is the accounting process of central government and the government's ''Transaction account, current account'' (i.e., mon ...

. The family's fortunes improved still further when Henry of Monmouth became king, although John died at Harfleur in 1415. His brother was knighted on the eve of the coronation and later fought at Agincourt.

From 1417, Erpingham seems to have retired and lived out his remaining years in Norfolk, having relinquished his position as steward that May. King Henry died in 1422, after which Erpingham had no further contact with the court. He died on 27 June 1428, and was buried on the north side of the presbytery of Norwich Cathedral. Sir William Phelip, who was an executor

An executor is someone who is responsible for executing, or following through on, an assigned task or duty.

The feminine form, executrix, is sometimes used.

Executor of will

An executor is a legal term referring to a person named by the maker o ...

of his uncle's will

Will may refer to:

Common meanings

* Will and testament, instructions for the disposition of one's property after death

* Will (philosophy), or willpower

* Will (sociology)

* Will, volition (psychology)

* Will, a modal verb - see Shall and will

...

, "inherited his substantial possessions in Norfolk". Dated 25 March 1427, the will contains bequest

A devise is the act of giving real property by will, traditionally referring to real property. A bequest is the act of giving property by will, usually referring to personal property. Today, the two words are often used interchangeably due to thei ...

s to Norwich Cathedral, churches in Norfolk and London, two Norwich hospitals

A hospital is a healthcare institution providing patient treatment with specialized health science and auxiliary healthcare staff and medical equipment. The best-known type of hospital is the general hospital, which typically has an emergency ...

and several East Anglian convents

A convent is an enclosed community of monks, nuns, friars or religious sisters. Alternatively, ''convent'' means the building used by the community.

The term is particularly used in the Catholic Church, Lutheran churches, and the Anglican Comm ...

. Erpingham specified that "all my armour and the harness of my person to be delivered up to the Holy Trinity athedralin Norwich".

Architectural legacy

Erpingham was a benefactor to the city of Norwich. In 1420 he had built the cathedral gate which bears his name, opposite the west door of Norwich Cathedral leading into Cathedral Close. He funded the rebuilding of the Church of the Blackfriars in Norwich after a fire in the city caused serious damage to the original friary complex in 1413. Today it forms part of the most complete friary surviving in England. The west tower of St. Mary's Church, in the village of Erpingham, was paid for by him. In 1419, Erpingham paid for the east chancel window of the church of St. Austin's Friary in Norwich to be glazed. The window contained eight panes, containing dedications to 107 noblemen or knights who died without producing an heir since the reign of Edward III. The building was demolished in 1547 after the priory was suppressed in 1538.Appearance in the Henriad

Sir Thomas Erpingham appears twice in Act IV ofWilliam Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

's play ''Henry V Henry V may refer to:

People

* Henry V, Duke of Bavaria (died 1026)

* Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor (1081/86–1125)

* Henry V, Duke of Carinthia (died 1161)

* Henry V, Count Palatine of the Rhine (–1227)

* Henry V, Count of Luxembourg (1216–1281 ...

'', first printed in 1600, and is mentioned (but does not appear) in Act II of ''Richard II

Richard II (6 January 1367 – ), also known as Richard of Bordeaux, was King of England from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. He was the son of Edward, Prince of Wales (later known as the Black Prince), and Joan, Countess of Kent. R ...

''. According to the Shakespearean scholar Thomas M. Cranfill, Erpingham plays a "considerable, affecting role". Just after the beginning of Scene 1, Erpingham enters and is acknowledged by the King. As the old man departs, Henry replies (probably out of Erpingham's hearing), "God-a-mercy, old heart! thou speak'st cheerfully", a line, as historian Lawrence Danson writes, "poised at gratitude and irony, admiration and desperation": Later in the same scene, Erpingham re-enters to inform the King that his nobles are looking for him, and in a simple line conveys the burden of being a ruler. Erpingham is a counterpart to the character of John Falstaff

Sir John Falstaff is a fictional character who appears in three plays by William Shakespeare and is eulogised in a fourth. His significance as a fully developed character is primarily formed in the plays ''Henry IV, Part 1'' and ''Henry IV, Pa ...

, his brief appearance in the Henriad

In Shakespearean scholarship, the Henriad refers to a group of William Shakespeare's Shakespearean history, history plays depicting the rise of the English kings. It is sometimes used to refer to a group of four plays (a tetralogy), but some s ...

contrasting with the much larger part given to Falstaff. Henry emphasises the knight's old age and marks him apart by consistently referring him by his full name, and the character is used to accentuate the connection between old age and goodness.

In film depictions of the play, Erpingham's part is largely silent, as in Laurence Olivier

Laurence Kerr Olivier, Baron Olivier ( ; 22 May 1907 – 11 July 1989) was an English actor and director. He and his contemporaries Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud made up a trio of male actors who dominated the British stage of the m ...

's film of 1944. Erpingham first appears near the end of the film, during the night before the battle of Agincourt. Kenneth Branagh

Sir Kenneth Charles Branagh ( ; born 10 December 1960) is a British actor and filmmaker. Born in Belfast and raised primarily in Reading, Berkshire, Branagh trained at RADA in London and served as its president from 2015 to 2024. List of award ...

, in his 1989 film, used the character more often and in, according to Curry, in a way that was "notably more inventive" than Olivier and showed more of an awareness of Erpingham's place in history. Identifiable in both films by his distinctive coat of arms

A coat of arms is a heraldry, heraldic communication design, visual design on an escutcheon (heraldry), escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the last two being outer garments), originating in Europe. The coat of arms on an escutcheon f ...

and his white hair—in contrast with that of the youthful looking Henry and his courtiers—Branagh includes Erpingham to good effect in the court scenes set in England, as well as during the battle and its aftermath. The character is given a more central (if largely silent) role by Branagh, without distorting Shakespeare's original intentions for the part.

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

*External links

The Erpingham Window

in

Norwich Cathedral

Norwich Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of the Holy and Undivided Trinity, is a Church of England cathedral in the city of Norwich, Norfolk, England. The cathedral is the seat of the bishop of Norwich and the mother church of the dioc ...

, made to commemorate Sir Thomas (Norwich Heritage).

Erpingham Dig

Educating people about the story of Sir Thomas Erpingham' at the village of

Erpingham

Erpingham ( ) is a village and civil parish in the English county of Norfolk.

Erpingham is located north of Aylsham and north of Norwich, along Scarrow Beck. The parish also includes the nearby village of Calthorpe.

History

Erpingham's na ...

Sir Thomas Erpingham's speeches (and cues)

in

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

's play ''Henry V Henry V may refer to:

People

* Henry V, Duke of Bavaria (died 1026)

* Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor (1081/86–1125)

* Henry V, Duke of Carinthia (died 1161)

* Henry V, Count Palatine of the Rhine (–1227)

* Henry V, Count of Luxembourg (1216–1281 ...

'', from George Mason University

George Mason University (GMU) is a Public university, public research university in Fairfax County, Virginia, United States. Located in Northern Virginia near Washington, D.C., the university is named in honor of George Mason, a Founding Father ...

's Open Shakespeare website.

Record

of the "Particulars of the account of Thomas Erpyngham" from the

National Archives

National archives are the archives of a country. The concept evolved in various nations at the dawn of modernity based on the impact of nationalism upon bureaucratic processes of paperwork retention.

Conceptual development

From the Middle Ages i ...

at Kew

Kew () is a district in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. Its population at the 2011 census was 11,436. Kew is the location of the Royal Botanic Gardens ("Kew Gardens"), now a World Heritage Site, which includes Kew Palace. Kew is ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Erpingham, Thomas

1350s births

1428 deaths

14th-century English military personnel

Lords Warden of the Cinque Ports

Knights of the Garter

People from North Norfolk (district)

People of the Hundred Years' War

Burials at Norwich Cathedral