Thirlmere on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thirlmere is a

a photograph of the pre-reservoir valley

it was repeatedly carried away by floods (e.g. in November 1861.)) Because of this constriction there were "practically at low water two lakes, the river connecting them being crossed at the Narrows by a little wood and stone bridge", and the natural lake is sometimes characterised as two lakes. The stream exiting the lake (St John's Beck) flowed north to the River Greta, which flowed west through Keswick to join the Cumbrian Derwent.

]

In their report to the full council, it was noted that water consumption had been a day in 1855, a day in 1865, in 1874 a day on average with peak demand a day. The reliable supply from the Longdendale reservoirs in periods of drought was only per day, but in the last two years, demand had increased by a day. Demand therefore was predicted to exceed the reliable supply in about seven years; it would take at least that to bring any major additional water supply on stream. Any major new works should aim to secure adequate supplies for the next thirty or fifty years; these could only be found in the mountains and lakes of northern Lancashire, Westmorland or Cumberland. Only Ullswater, Haweswater and Thirlmere were high enough to supply Manchester by gravity flow; the natural drainage of all three was to the north, but Thirlmere lay immediately below the pass of Dunmail Raise and the engineering to bring its waters south of the watershed would be significantly easier than for (for example) Ullswater. Thirlmere water had been analysed by Professor Roscoe who pronounced it superior even to that of Loch Katrine and thus one of the best waters known.

Speaking to the report, the chairman of the Waterworks Committee noted that the catchment area was over (in which there were not more than 200 inhabitants) and the annual rainfall about ; a day could be collected and sent to Manchester; unlike the massive dams in Longdendale, all that was needed was a wall fifty-foot high across a gorge he could throw a stone across. As regards aesthetic objections:

The report had predicted little opposition to the scheme, by which it asserted the "beauty of the lake will be rather enhanced than otherwise". Other councillors were less sure of this, one noting that:

]

In their report to the full council, it was noted that water consumption had been a day in 1855, a day in 1865, in 1874 a day on average with peak demand a day. The reliable supply from the Longdendale reservoirs in periods of drought was only per day, but in the last two years, demand had increased by a day. Demand therefore was predicted to exceed the reliable supply in about seven years; it would take at least that to bring any major additional water supply on stream. Any major new works should aim to secure adequate supplies for the next thirty or fifty years; these could only be found in the mountains and lakes of northern Lancashire, Westmorland or Cumberland. Only Ullswater, Haweswater and Thirlmere were high enough to supply Manchester by gravity flow; the natural drainage of all three was to the north, but Thirlmere lay immediately below the pass of Dunmail Raise and the engineering to bring its waters south of the watershed would be significantly easier than for (for example) Ullswater. Thirlmere water had been analysed by Professor Roscoe who pronounced it superior even to that of Loch Katrine and thus one of the best waters known.

Speaking to the report, the chairman of the Waterworks Committee noted that the catchment area was over (in which there were not more than 200 inhabitants) and the annual rainfall about ; a day could be collected and sent to Manchester; unlike the massive dams in Longdendale, all that was needed was a wall fifty-foot high across a gorge he could throw a stone across. As regards aesthetic objections:

The report had predicted little opposition to the scheme, by which it asserted the "beauty of the lake will be rather enhanced than otherwise". Other councillors were less sure of this, one noting that:

To protect the purity of Thirlmere water, Manchester Corporation set about buying up all the land in its catchment area; the price it offered was such that there was little truly local opposition to the scheme. In Keswick, the nearest town, over 90% of ratepayers signed a petition in favour (Keswick had suffered repeatedly from flooding after heavy rainfall in the Thirlmere area). To the south, the only town council in Westmorland (

To protect the purity of Thirlmere water, Manchester Corporation set about buying up all the land in its catchment area; the price it offered was such that there was little truly local opposition to the scheme. In Keswick, the nearest town, over 90% of ratepayers signed a petition in favour (Keswick had suffered repeatedly from flooding after heavy rainfall in the Thirlmere area). To the south, the only town council in Westmorland (

Henry Marten

Edward Easton

agreed with Marten that the restrictions on consumption in Manchester were not too stringent and was astonished at Bateman's claim that there were no further suitable reservoir sites in Longdendale; in one weekend he had identified four or five suitable sites. After Longdendale there were other possible sites, amongst many others those on the headwaters of the Derbyshire Derwentbr>Thomas Fenwick

gave evidence on the practicality of using reservoirs on the Derwent, but had to admit that he did so based on the work of a one-weekend visit to the area, that the Derwent catchment area did not naturally belong to Manchester, and that the Derwent flowed past Chatsworth so any interference with its natural flow would have to be agreeable to the Duke of Devonshire. The Derwent valley was almost as beautiful as the lakes, but lacked a lake; its beauty would be improved by a reservoir. Aqueducts (like one he had built for Dewsbury) were scarcely visible once built, and much more care was now taken in the construction of dams; dam failure was a thing of the past. Playfair declined the offer of further evidence from Manchester on getting water from the Derwent catchment area, as its proponents had given no real detail, nor any notice to potential objectors: a brief comment by Bateman would suffice. Bateman was then re-examined on the possibility of increasing storage at Longdendale. Easton's suggestion of additional sites was 'utterly absurd'; all practicable sites were already taken: "He had been working in these valleys for nearly thirty years, and he thought he knew something more about them than a man who made a galloping journey over them in one day". Taking water from the Derwent catchment area would require a -long tunnel, and cost nearly as much as Thirlmere for half the yield.

The first phase was to construct the aqueduct with a capacity of a day, and to raise the level of Thirlmere by damming up its natural exit to the north. The engineer for the project was George Hill (formerly an assistant, and then partner of Bateman). Contracts for the aqueduct went out for tender in autumn 1885; by April 1886 excavation of the tunnels had begun and hutted camps had sprung up (at White Moss, and elsewhere) to house the army of navvies (who were paid 4d an hour): The original contractor suspended work in February 1887, and the contract had to be re-let. A further bill (supported by the Lake District Defence Society and Canon Rawnsley) was contemplated for 1889 to allow Thirlmere to be raised only 20 ft in the first instance, and defer improvement of the road on the west side of the lake but was not proceeded with. Boring of the tunnel under Dunmail Raise was completed in July 1890, and work then began on the dam at the north end of Thirlmere. There were then between five and six thousand men working on the Thirlmere project.

Before any supply from Thirlmere became available, there were two dry summers during which Manchester experienced a 'water famine'. The summer of 1887 was the driest for years, with stocks falling to 14 days' supply in early August, and the water supply consequently being cut off from 6 pm to 6 am. Stocks at the start of 1888 were markedly lower than in previous years, and as early as March 1888 the water supply was again cut off overnight (8pm-5am), but spring rain soon allowed a resumption of the constant supply. 1893 saw another dry summer, with stocks falling to twenty-four days' supply by the start of September and that – a councillor complained – of inferior quality with 'an abundance of animal life visible to the naked eye' in tap water. By now, the aqueduct and dam were complete, but under the 1879 Act the roads around Thirlmere had to be completed before any water could be taken from it. The summer of 1894 was wet, and starting to use Thirlmere water would mean charges of £10,000 a year; the opening was therefore delayed until October 1894. There were two opening ceremonies; one at Thirlmere followed next day in Manchester by the turning-on of water to a fountain in Albert Square.

The first phase was to construct the aqueduct with a capacity of a day, and to raise the level of Thirlmere by damming up its natural exit to the north. The engineer for the project was George Hill (formerly an assistant, and then partner of Bateman). Contracts for the aqueduct went out for tender in autumn 1885; by April 1886 excavation of the tunnels had begun and hutted camps had sprung up (at White Moss, and elsewhere) to house the army of navvies (who were paid 4d an hour): The original contractor suspended work in February 1887, and the contract had to be re-let. A further bill (supported by the Lake District Defence Society and Canon Rawnsley) was contemplated for 1889 to allow Thirlmere to be raised only 20 ft in the first instance, and defer improvement of the road on the west side of the lake but was not proceeded with. Boring of the tunnel under Dunmail Raise was completed in July 1890, and work then began on the dam at the north end of Thirlmere. There were then between five and six thousand men working on the Thirlmere project.

Before any supply from Thirlmere became available, there were two dry summers during which Manchester experienced a 'water famine'. The summer of 1887 was the driest for years, with stocks falling to 14 days' supply in early August, and the water supply consequently being cut off from 6 pm to 6 am. Stocks at the start of 1888 were markedly lower than in previous years, and as early as March 1888 the water supply was again cut off overnight (8pm-5am), but spring rain soon allowed a resumption of the constant supply. 1893 saw another dry summer, with stocks falling to twenty-four days' supply by the start of September and that – a councillor complained – of inferior quality with 'an abundance of animal life visible to the naked eye' in tap water. By now, the aqueduct and dam were complete, but under the 1879 Act the roads around Thirlmere had to be completed before any water could be taken from it. The summer of 1894 was wet, and starting to use Thirlmere water would mean charges of £10,000 a year; the opening was therefore delayed until October 1894. There were two opening ceremonies; one at Thirlmere followed next day in Manchester by the turning-on of water to a fountain in Albert Square.

The second pipe could deliver a day, giving a total capacity of the aqueduct of a day. The water level was raised to 35 ft above natural; the area of the lake now increasing to . of Shoulthwaite Moss (north of Thirlmere) were reclaimed as winter pasture to compensate for the loss of acreage around Thirlmere. A third pipe was authorised in 1906, construction began in October 1908, and was completed in 1915: this increased the potential supply from Thirlmere to a day against an average daily demand which had now reached : in the summer of 1911 it had again been necessary to suspend the water supply at night. The lake was then raised to above natural; a fourth and final pipeline was completed in 1927, its authorisation having been delayed by the First World War until 1921; as early as 1918 Manchester Corporation had identified the need for a further source of water, and identified Haweswater as that source.

At the committee stage of Manchester's 1919 bill to tap Haweswater, the average daily demand on Manchester's water supply in 1917 was said to have been a day, with the reliable supply from Longdendale being no more than a day and Thirlmere being able to supply a day, which would rise to a day when the fourth pipe was laid. The aqueduct capacity could be increased to a day by laying a fifth pipe, but could not be increased beyond that whilst the aqueduct was still being used to deliver water to Manchester.

The second pipe could deliver a day, giving a total capacity of the aqueduct of a day. The water level was raised to 35 ft above natural; the area of the lake now increasing to . of Shoulthwaite Moss (north of Thirlmere) were reclaimed as winter pasture to compensate for the loss of acreage around Thirlmere. A third pipe was authorised in 1906, construction began in October 1908, and was completed in 1915: this increased the potential supply from Thirlmere to a day against an average daily demand which had now reached : in the summer of 1911 it had again been necessary to suspend the water supply at night. The lake was then raised to above natural; a fourth and final pipeline was completed in 1927, its authorisation having been delayed by the First World War until 1921; as early as 1918 Manchester Corporation had identified the need for a further source of water, and identified Haweswater as that source.

At the committee stage of Manchester's 1919 bill to tap Haweswater, the average daily demand on Manchester's water supply in 1917 was said to have been a day, with the reliable supply from Longdendale being no more than a day and Thirlmere being able to supply a day, which would rise to a day when the fourth pipe was laid. The aqueduct capacity could be increased to a day by laying a fifth pipe, but could not be increased beyond that whilst the aqueduct was still being used to deliver water to Manchester.

At the committee stage of the Haweswater bill, objectors made no mention of the aesthetic concerns raised against the Thirlmere bills: "The world now knows that many of the fears then expressed were very foolish ones, and would never be realised under any circumstances, or at any place" said the '' Yorkshire Post'' although Manchester countered the suggestion that it should not annex Haweswater, but instead further raise the level of Thirlmere because "it would mean such injury to the Lake District that they would have the whole country up against them"

At the committee stage of the Haweswater bill, objectors made no mention of the aesthetic concerns raised against the Thirlmere bills: "The world now knows that many of the fears then expressed were very foolish ones, and would never be realised under any circumstances, or at any place" said the '' Yorkshire Post'' although Manchester countered the suggestion that it should not annex Haweswater, but instead further raise the level of Thirlmere because "it would mean such injury to the Lake District that they would have the whole country up against them"

When the Lords defeated Manchester's Bill for abstraction of water from Ullswater in 1962, however, many speakers pointed to Manchester's stewardship of Thirlmere to show why the bill should be defeated:

* To improve the retention of water in the catchment area, from 1907 onwards Manchester had planted extensive stands of conifers on both banks of the reservoir; as they grew, they had radically altered the appearance of the area, and (as James Lowther - now Lord Ullswater - complained) destroyed the views from the road on the west bank provided to give the public views of Helvellyn

* As Thirlmere water became more essential as a supply to Manchester, the draw-down of the reservoir in dry weather increased to double the 8–9 foot promised in the 1870s.

* "Large flooding of a valley bottom means an end to farming, and Thirlmere and Mardale are farmless and depopulated" but this was not just because of the higher water level. There was no provision for water treatment downstream of Thirlmere (or Longdendale), and Manchester therefore relied on minimising pollution at source. To achieve this, it minimised human activity in the catchment area. Much of the settlement around Wythburn church (including the Nag's Head, a coaching inn with Wordsworthian associations) remained above water level but it was suppressed, accommodation for necessary waterworks employees being provided at Fisher End and Stanah east of the northern end of the reservoir. Eventually Manchester Corporation closed Wythburn churchyard, St John's in the Vale being now more convenient for its future customers.

* To protect the water from contamination by tourists and visitors, bathing boating and fishing were prohibited, and access to the lake effectively banned. This policy was supported by "...barbed wire, wire netting, regimented rows of conifers and trespass warning notices, as common as 'Verboten' notices in Nazi Germany…" said the ''Yorkshire Post'' in 1946.

When the Lords defeated Manchester's Bill for abstraction of water from Ullswater in 1962, however, many speakers pointed to Manchester's stewardship of Thirlmere to show why the bill should be defeated:

* To improve the retention of water in the catchment area, from 1907 onwards Manchester had planted extensive stands of conifers on both banks of the reservoir; as they grew, they had radically altered the appearance of the area, and (as James Lowther - now Lord Ullswater - complained) destroyed the views from the road on the west bank provided to give the public views of Helvellyn

* As Thirlmere water became more essential as a supply to Manchester, the draw-down of the reservoir in dry weather increased to double the 8–9 foot promised in the 1870s.

* "Large flooding of a valley bottom means an end to farming, and Thirlmere and Mardale are farmless and depopulated" but this was not just because of the higher water level. There was no provision for water treatment downstream of Thirlmere (or Longdendale), and Manchester therefore relied on minimising pollution at source. To achieve this, it minimised human activity in the catchment area. Much of the settlement around Wythburn church (including the Nag's Head, a coaching inn with Wordsworthian associations) remained above water level but it was suppressed, accommodation for necessary waterworks employees being provided at Fisher End and Stanah east of the northern end of the reservoir. Eventually Manchester Corporation closed Wythburn churchyard, St John's in the Vale being now more convenient for its future customers.

* To protect the water from contamination by tourists and visitors, bathing boating and fishing were prohibited, and access to the lake effectively banned. This policy was supported by "...barbed wire, wire netting, regimented rows of conifers and trespass warning notices, as common as 'Verboten' notices in Nazi Germany…" said the ''Yorkshire Post'' in 1946.

Mansergh, James. "The Thirlmere water scheme of the Manchester Corporation : with a few remarks on the Longdendale Works, and water-supply generally." London: Spon, 1879

- popularising lecture, with copious plans & elevations

Ritvo, Harriet. "Manchester v. Thirlmere and the Construction of the Victorian Environment." Victorian Studies 49.3 (2007): 457-481.

Pre-reservoir Thirlmere, and the opposition to the reservoir

Bradford, William "An Evaluation of the Historical Approaches to Uncertainty in the Provision of Victorian Reservoirs in the UK, and the Implications for Future Water Resources " July 2012 PhD thesis; University of Birmingham School of Civil Engineering

The lead 'Victorian reservoir' is Birmingham's Elan Valley scheme, but Thirlmere is covered; in particular how Bateman estimated potential supply and future demand and how he approached uncertainty

reservoir

A reservoir (; ) is an enlarged lake behind a dam, usually built to water storage, store fresh water, often doubling for hydroelectric power generation.

Reservoirs are created by controlling a watercourse that drains an existing body of wa ...

in the Cumberland district in Cumbria

Cumbria ( ) is a ceremonial county in North West England. It borders the Scottish council areas of Dumfries and Galloway and Scottish Borders to the north, Northumberland and County Durham to the east, North Yorkshire to the south-east, Lancash ...

and the English Lake District

The Lake District, also known as ''the Lakes'' or ''Lakeland'', is a mountainous region and National parks of the United Kingdom, national park in Cumbria, North West England. It is famous for its landscape, including its lakes, coast, and mou ...

. The Helvellyn

Helvellyn (; possible #Names, meaning: ''pale yellow moorland'') is a mountain in the English Lake District, the highest point of the Helvellyn range, a north–south line of mountains to the north of Ambleside, between the lakes of Thirlmere a ...

ridge lies to the east of Thirlmere. To the west of Thirlmere are a number of fells; for instance, Armboth Fell and Raven Crag both of which give views of the lake and of Helvellyn beyond.

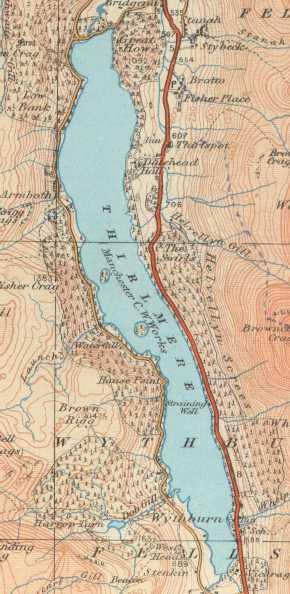

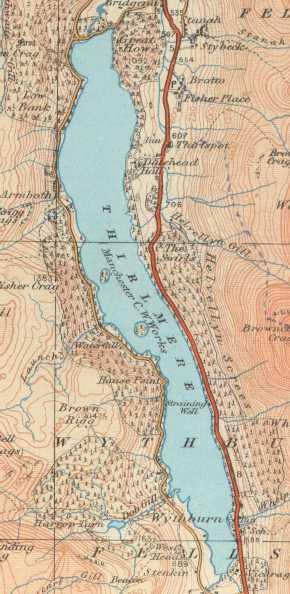

The reservoir runs roughly south to north and is bordered on the eastern side for much of its length by the A591 road and on the western side by a minor road. It occupies the site of a former natural lake: this had a fordable waist so narrow that it was (and is) sometimes regarded as two lakes. In the 19th century Manchester Corporation constructed a dam at the northern end, raising the water level, flooding the valley bottom, and creating a reservoir to provide the growing industrial city of Manchester with water supplies via the -long Thirlmere Aqueduct

The Thirlmere Aqueduct is a 95.9-mile-long (154.3-kilometre-long) pioneering section of water supply system in England, built by the Manchester Corporation Water Works between 1890 and 1925. Often incorrectly thought of as one of the List of lon ...

.

The reservoir and the aqueduct still provide water to the Manchester area, but under the Water Act 1973 ownership passed to the North West Water Authority; as a result of subsequent privatisation and amalgamation they (and the catchment area surrounding the reservoir) are now owned and managed by United Utilities

United Utilities Group plc (UU) is the United Kingdom's largest listed water company. It was founded in 1995 as a result of the merger of North West Water and NORWEB. The group manages the regulated water and waste water network in North West En ...

, a private sector

The private sector is the part of the economy which is owned by private groups, usually as a means of establishment for profit or non profit, rather than being owned by the government.

Employment

The private sector employs most of the workfo ...

water and wastewater

Wastewater (or waste water) is water generated after the use of freshwater, raw water, drinking water or saline water in a variety of deliberate applications or processes. Another definition of wastewater is "Used water from any combination of do ...

company.

The natural lake

We now approached the lake of Wyburn, or Thirlmer, as it is sometimes called; an object every way suited to the ideas of desolation which surround it, No tufted verdure graces banks, nor hanging woods throw rich reflections on surface: but every form which it suggests, is savage, and desolate.Before the construction of the reservoir there was a smaller natural lake, known by various names including Leathes Water, Wythburn Water Thirle Water, and Thirlmere. (The Leathes were the lords of the manor, the valley in which the lake sat was Wythburndale (after the hamlet of Wythburn at its head), 'Thirlmere' probably is derived from " 'the lake with/at the narrowing' from OE ''þyrel'' 'aperture', pierced hole' plus OE ''mere'' 'lake'") The Ordnance Survey map of 1867Map published 1867, based upon a survey carried out in 1862: shows a single lake (Thirlmere) with its narrowest point at Wath Bridge roughly level with Armboth; at this point "The water is shallow and crossed by a bridge, so that piers are easily built and connected with little wooden bridges, and that difficult problem in engineering - crossing a lake - accomplished" and the map shows both a bridge and a ford between the west and east banks. ('Wath' = 'ford' in Cumbrian placenames: the 'Bridge' itself can be seen i

a photograph of the pre-reservoir valley

it was repeatedly carried away by floods (e.g. in November 1861.)) Because of this constriction there were "practically at low water two lakes, the river connecting them being crossed at the Narrows by a little wood and stone bridge", and the natural lake is sometimes characterised as two lakes. The stream exiting the lake (St John's Beck) flowed north to the River Greta, which flowed west through Keswick to join the Cumbrian Derwent.

The 'Thirlmere scheme'

Use as a reservoir suggested

In 1863, a pamphlet urged that Thirlmere and Haweswater should be made reservoirs, and their water conveyed (viaUllswater

Ullswater is a glacial lake in Cumbria, England and part of the Lake District National Park. It is the second largest lake in the region by both area and volume, after Windermere. The lake is about long, wide, and has a maximum depth of . I ...

(used as a distributing reservoir)) to London to supply it with a day of clean water; the cost of the project was put at ten million pounds. The scheme was considered by a Royal Commission on Water Supply chaired by the Duke of Richmond, but its report of 1869 dismissed such long-distance schemes, preferring to supply London by pumping from aquifer

An aquifer is an underground layer of water-bearing material, consisting of permeability (Earth sciences), permeable or fractured rock, or of unconsolidated materials (gravel, sand, or silt). Aquifers vary greatly in their characteristics. The s ...

s and abstraction from the Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after th ...

.conclusions and recommendations as reported in The scheme continued to be proposed; by 1876, it had grown to include a branch feeder from Bala Lake and the cost had risen accordingly to £m 13.5; however nothing ever came of it.

The original scope specified for the Duke of Richmond's royal commission had been the water supply of London ''and other large cities'', but the commission had found itself fully occupied by consideration of the metropolitan water supply. For water supply elsewhere, its report had merely made general recommendations: ... that no town or district should be allowed to appropriate a source of supply which naturally and geographically belongs to a town or district nearer to such source, unless under special circumstances which justify the appropriation. That when any town or district is supplied by a line or conduit from a distance, provision ought to be made for the supply of all places along such lines. That on the introduction of any provincial water bill into Parliament, attention should be drawn to the practicability of making the measure applicable to as extensive a district as possible, and not merely to the particular town.

Manchester looks to Thirlmere

The corporations of bothManchester

Manchester () is a city and the metropolitan borough of Greater Manchester, England. It had an estimated population of in . Greater Manchester is the third-most populous metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, with a population of 2.92&nbs ...

and Liverpool

Liverpool is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. It is situated on the eastern side of the River Mersey, Mersey Estuary, near the Irish Sea, north-west of London. With a population ...

had already constructed a series of reservoirs to support their growth (Liverpool at Rivington, Manchester at Longdendale) but saw no possibility of further reservoirs there. Concerned that their existing water supplies would be rendered inadequate by their growth, they were now seeking further supplies: to comply with the royal commission's "no poaching" recommendation any further reservoirs would have to be much further afield. In 1875 John Frederick Bateman suggested that Manchester and Liverpool should supply themselves with water from Haweswater and Ullswater (made reservoirs) as a joint undertaking. Both Liverpool and Manchester corporations rejected this, feeling that the interests of their cities required their water supplies to be independent of any other city. Instead in 1877, Liverpool initiated a scheme for a reservoir on the headwaters of the Vyrnwy in North Wales; at the instigation of their chairman (a native of Cumberland with a second home at Portinscale on Derwentwater), the Waterworks Committee of Manchester Corporation proposed to supply Manchester with water from a Thirlmere reservoir.

]

In their report to the full council, it was noted that water consumption had been a day in 1855, a day in 1865, in 1874 a day on average with peak demand a day. The reliable supply from the Longdendale reservoirs in periods of drought was only per day, but in the last two years, demand had increased by a day. Demand therefore was predicted to exceed the reliable supply in about seven years; it would take at least that to bring any major additional water supply on stream. Any major new works should aim to secure adequate supplies for the next thirty or fifty years; these could only be found in the mountains and lakes of northern Lancashire, Westmorland or Cumberland. Only Ullswater, Haweswater and Thirlmere were high enough to supply Manchester by gravity flow; the natural drainage of all three was to the north, but Thirlmere lay immediately below the pass of Dunmail Raise and the engineering to bring its waters south of the watershed would be significantly easier than for (for example) Ullswater. Thirlmere water had been analysed by Professor Roscoe who pronounced it superior even to that of Loch Katrine and thus one of the best waters known.

Speaking to the report, the chairman of the Waterworks Committee noted that the catchment area was over (in which there were not more than 200 inhabitants) and the annual rainfall about ; a day could be collected and sent to Manchester; unlike the massive dams in Longdendale, all that was needed was a wall fifty-foot high across a gorge he could throw a stone across. As regards aesthetic objections:

The report had predicted little opposition to the scheme, by which it asserted the "beauty of the lake will be rather enhanced than otherwise". Other councillors were less sure of this, one noting that:

]

In their report to the full council, it was noted that water consumption had been a day in 1855, a day in 1865, in 1874 a day on average with peak demand a day. The reliable supply from the Longdendale reservoirs in periods of drought was only per day, but in the last two years, demand had increased by a day. Demand therefore was predicted to exceed the reliable supply in about seven years; it would take at least that to bring any major additional water supply on stream. Any major new works should aim to secure adequate supplies for the next thirty or fifty years; these could only be found in the mountains and lakes of northern Lancashire, Westmorland or Cumberland. Only Ullswater, Haweswater and Thirlmere were high enough to supply Manchester by gravity flow; the natural drainage of all three was to the north, but Thirlmere lay immediately below the pass of Dunmail Raise and the engineering to bring its waters south of the watershed would be significantly easier than for (for example) Ullswater. Thirlmere water had been analysed by Professor Roscoe who pronounced it superior even to that of Loch Katrine and thus one of the best waters known.

Speaking to the report, the chairman of the Waterworks Committee noted that the catchment area was over (in which there were not more than 200 inhabitants) and the annual rainfall about ; a day could be collected and sent to Manchester; unlike the massive dams in Longdendale, all that was needed was a wall fifty-foot high across a gorge he could throw a stone across. As regards aesthetic objections:

The report had predicted little opposition to the scheme, by which it asserted the "beauty of the lake will be rather enhanced than otherwise". Other councillors were less sure of this, one noting that:

The Thirlmere Defence Association

To protect the purity of Thirlmere water, Manchester Corporation set about buying up all the land in its catchment area; the price it offered was such that there was little truly local opposition to the scheme. In Keswick, the nearest town, over 90% of ratepayers signed a petition in favour (Keswick had suffered repeatedly from flooding after heavy rainfall in the Thirlmere area). To the south, the only town council in Westmorland (

To protect the purity of Thirlmere water, Manchester Corporation set about buying up all the land in its catchment area; the price it offered was such that there was little truly local opposition to the scheme. In Keswick, the nearest town, over 90% of ratepayers signed a petition in favour (Keswick had suffered repeatedly from flooding after heavy rainfall in the Thirlmere area). To the south, the only town council in Westmorland (Kendal

Kendal, once Kirkby in Kendal or Kirkby Kendal, is a market town and civil parish in the unitary authority of Westmorland and Furness, England. It lies within the River Kent's dale, from which its name is derived, just outside the boundary of t ...

) voted to support the scheme (hoping that a supply from the aqueduct would be a cheaper solution to their water supply problems than the new waterworks which would otherwise be needed): a local paper noted that "the inhabitants of Westmorland are not much alarmed at it …so far they have stolidly refused to lose their tempers, or even waste many words over it". At a meeting to form a Lake District Association to promote tourism in the region, it was quickly agreed not to take a view on the Thirlmere scheme; otherwise the association would break up before it was fairly started.

The aqueduct, however, was objected to by owners of land through which it would pass: under normal procedure, they would be the only objectors with sufficient '' locus standi'' to be heard against the private bill necessary to authorise the scheme. Those who objected to the change in the appearance (as they saw it, destruction of the beauty) of the lake would be unable to demonstrate any financial interest in the matter. They therefore needed to stop the project by mobilising opinion against the scheme; in 1876 this – together with economic hard times – had seen off a scheme to link the existing railheads at Keswick and Windermere by a railway running alongside Thirlmere.

"If every person who has visited the Lake District, in a true nature-loving spirit would be ready, when the right time comes, to sign an indignant protest against the scheme, surely there might be some hope..." that Parliament would reject the bill, urged one correspondent, who went on to urge legal protection for natural beauty, along the lines of that proposed for ancient monuments by Sir John Lubbock or for the Yellowstone area in the United States.Letter dated "Keswick, June 4" from " J Clifton Ward HM Geological Survey" (but clearly in a private capacity) printed as Octavia Hill

Octavia Hill (3December 183813August 1912) was an English Reform movement, social reformer and founder of the National Trust. Her main concern was the welfare of the inhabitants of cities, especially London, in the second half of the nineteent ...

called for a committee to organise (and collect funds for) an effective opposition. A meeting at Grasmere in September 1877, considered a report on the Thirlmere scheme from H J Marten CE and formed a Thirlmere Defence Association (TDA) with over £1,000 of subscriptions pledged. By February 1878, members of the TDA included Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian, and philosopher. Known as the "Sage writing, sage of Chelsea, London, Chelsea", his writings strongly influenced the intellectual and artistic culture of the V ...

, Matthew Arnold

Matthew Arnold (24 December 1822 – 15 April 1888) was an English poet and cultural critic. He was the son of Thomas Arnold, the headmaster of Rugby School, and brother to both Tom Arnold (academic), Tom Arnold, literary professor, and Willi ...

, William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was an English textile designer, poet, artist, writer, and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts movement. He was a major contributor to the revival of traditiona ...

, Thomas Woolner R.A., John Gilbert R.A. and Derwent Coleridge.

Aesthetic opposition to the scheme was aggravated by the suggestion that Manchester Corporation would improve on natureSee Bishop of Manchester's speech (the inaugural address) reported in and varied in tone and thoughtfulness: the Carlisle Patriot thought Manchester welcome to take all the water it needed, provided only that it must not "destroy or deface those natural features which constitute the glory of the Lake District" and advised against any attempt to mitigate the offence by tree-planting; Thirlmere had "..a character of its own which makes the suggested artificiality intolerable. The rocky walls that hem it in boast no verdure: wild precipices, grand in the austerity of their barrenness cast their reflections on the mere, and by their wildness scout the municipal device of decoration.."

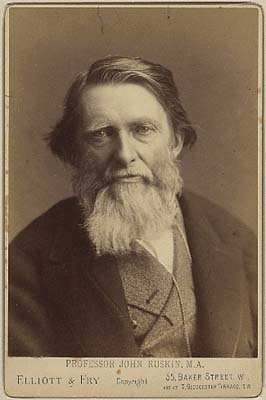

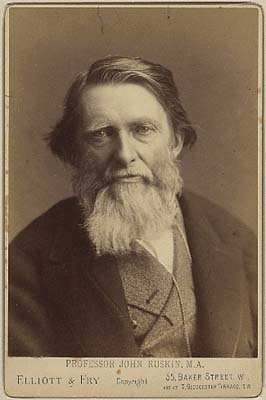

John Ruskin

John Ruskin (8 February 1819 20 January 1900) was an English polymath a writer, lecturer, art historian, art critic, draughtsman and philanthropist of the Victorian era. He wrote on subjects as varied as art, architecture, Critique of politic ...

denounced Manchester in general I am quite aware that there are many amiable persons in Manchester - and much general intelligence. But, taken as a whole, I perceive that Manchester can produce no good art, and no good literature; it is falling off even in the quality of its cotton; it has reversed, and vilified in loud lies, every essential principle of political economy; it is cowardly in war, predatory in peace...and thought it would be more just if instead of Manchester Corporation being allowed to "steal and sell for a profit the water of Thirlmere and clouds of Hevellyn" it should be drowned in Thirlmere.Letter LXXXII (dated 'Brantwood, 13 September 1877') in The Mancunian press thought it detected a similar (if less blatant) prejudice and an 'essentially Cockney agitation' when papers such as the

Pall Mall Gazette

''The Pall Mall Gazette'' was an evening newspaper founded in London on 7 February 1865 by George Murray Smith; its first editor was Frederick Greenwood. In 1921, '' The Globe'' merged into ''The Pall Mall Gazette'', which itself was absorbed i ...

editorialised "The visible universe was not created merely to supply materials towards the manufacture of shoddy

Recycled wool, also known as rag wool or shoddy is any Wool, woollen textile or yarn made by shredding existing fabric and re-spinning the resulting fibres. Textile recycling is an important mechanism for reducing the need for raw wool in manufact ...

"

Speaking at the opening of the new Town Hall in Manchester, the Bishop of Manchester declared himself surprised at the language of the scheme's opponents, many of whom, he thought, had no idea where Thirlmere was but although he thought their aesthetic judgement wrong his counter-argument was not aesthetic, but political ..one man in eight was interested more or less in the vital interests of Manchester, and he thought when some of the carpings which dainty clubmen in London indulged in at their expense - that they had no right to take water from a Cumberland or Westmorland lake - he thought they had a right to stand up and claim their inheritance, and to claim that two millions of people had a right to the necessaries of life from any portion of England.

Private bill of 1878

Manchester gave the required notice of its forthcoming bill in November 1877. It sought powers to dam the outflow from Thirlmere and to divert into it a number of neighbouring gills which did not already drain into it, to build an aqueduct from Thirlmere to Manchester, and to extract water from Thirlmere. In addition, a section of the existing Keswick-Ambleside turnpike north of Wythburn was to be diverted to run at a higher level, and a new carriage road was to be built on the western side of Thirlmere. Compulsory purchase powers were sought to allow these works to be carried out and to allow Manchester Corporation to buy and keep land in the Thirlmere catchment area. In response, the TDA issued a statement of its case. The scheme would destroy the distinctive charm of Thirlmere which was 'entirely free from modern erections out of harmony with the surroundings'; raising the level would destroy the many small bays that gave the west shore its character, the 'picturesque windings' of the existing road on the east side were to be replaced by a dead level road, at the northern end, 'one of the sweetest glens in Cumberland' was to be the site of an enormous embankment. Worst of all, in a dry season, the lake would be drawn down to its old level, exposing over of 'oozy mud and rotting vegetation'. "Few persons, whose taste is not utterly uneducated, are likely to share the confidence of the water committee in their power to enhance the loveliness of such a scene, or will think that the boldest devices of engineering skill will be other than a miserable substitute for the natural beauties they displace." Furthermore, the scheme was unnecessary: Manchester already had an ample supply of water; its apparent consumption was so high because it was selling water to industrial users, and to areas outside Manchester and Manchester sought to increase such sales because they were profitable. Manchester could easily get more (and of superior quality) from wells tapping the New Red Sandstone aquifer; if they were still unsatisfied there were vast untouched collecting grounds in the moorlands of Lancashire. There was also a more general point; the Thirlmere scheme, if approved, would set a precedent for municipalities to buy up whole valleys in the Lake District, leaving them at the mercy of "bodies of men, skilful and diligent enough in managing local affairs, but having little capacity to appreciate the importance of subjects beyond their daily sphere of action" with painful consequences for their natural beauty.Second Reading debate

In January 1878, Edward Howard, the MP for East Cumberland who had given notice of a motion calling for a select committee looking at the problems of water supply to Lancashire and Yorkshire (which would have prevented progress of the Thirlmere Bill until the select committee had reported), announced that he would delay introducing the motion until the Thirlmere Bill had been defeated at second reading. Normally, private bills were not opposed at Second Reading; their success or failure was determined by the committee stage which followed. However, when the Second Reading of the Thirlmere Bill was moved, Howard spoke against it, and was supported by William Lowther, MP forWestmorland

Westmorland (, formerly also spelt ''Westmoreland''R. Wilkinson The British Isles, Sheet The British IslesVision of Britain/ref>) is an area of North West England which was Historic counties of England, historically a county. People of the area ...

. Two Manchester MPs spoke for the bill, as did the MP for Cockermouth, Isaac Fletcher, a West Cumberland mine-owner and industrialist. The Chairman of Ways and Means said it was impossible that the bill could be considered by an ordinary private bill committee, and suggested that it should be referred to a Hybrid Committee, where "persons might be examined who have not those sharply-defined interests which are usually represented before a private committee. Such a Committee might consider this question through all its bearings, public as well as private; and they might, at all events, lay down a principle for the guidance of the House in dealing with future questions connected with the water supply of populous districts." Only if this was promised could he vote for the Second Reading; other speakers followed his lead, and it was on this basis that the bill then passed its Second Reading.

Committee stage

The bill was considered by a committee chaired by Lyon Playfair: its terms of reference were (bulleting added for clarity)* to inquire into, and report upon the present sufficiency of the water supply of Manchester and its neighbourhood, and of any other sources available for such supply; * to consider whether permission should be given to make use of any of the Westmoreland and Cumberland lakes for the purpose, and if so, how far and under what conditions, to consider the prospective requirements of the populations situated between the lake district and Manchester; * to inquire, and report, whether any, and, if so, what, provisions should be made in limitation of proposals for the exclusive use of the water of any of the said lakes

=Manchester's case

= Manchester fielded a legal team headed by Sir Edmund Beckett QC, a leading practitioner at the parliamentary bar: they called witnesses to make the case for the scheme. Manchester waterworks supplied an area containing 800,000 inhabitants, about 380,000 of whom lived within the city boundary. In dry summers, the water supply had to be cut off at night to conserve stocks. In 1868, admittedly before the works in Longdendale were complete, this had happened for 75 days.evidence of ex-Mayor Grundy Water consumption was about a day per person, but it was that low because Manchester had discouraged water-closets and baths in working-class housingevidence of Sir John Heron, Town Clerk of Manchester: The waterworks did not make a profit; by an act of Parliament the total water rate could not exceed 10d per pound rental within the city; 12d in the supplied area outside the city (to have equal rates would be unfair to the rate payers who stood as guarantors for very large capital expenditure) Manchester was not profiteering from its present water supply, nor was it out to profit from the scheme: it would accept whatever obligation to supply areas along the aqueduct route (and/or price cap on sales outside the city) the committee saw fit to impose. There was no possibility of adding further reservoirs in Longdendale and no suitable unclaimed sites south of the Lune; the headwaters of the Lune were in limestone country, making both water quality (soft water was preferred by domestic customers and needed for textile processing) and reservoir construction problematical.evidence of Mr Bateman C.E. Thirlmere water was exceptionally pure whereas water pumped from the sandstone even when drinkable generally had considerable permanent hardnessevidence of Professor Roscoe Taking water from Ullswater rather than Thirlmere would cost about £370,000 more. Thirlmere had higher rainfall than Longdendale (even in the driest year, should be expected) and (by raising the water level) storage sufficient to allow the supply of a day through any reasonably sustained drought: the reliable supply from Longdendale was only half that.further evidence of Mr Bateman The aqueduct to Manchester would (at different points on its route) be a tunnel through rock, a buried culvert constructed by cut-and-cover, or cast-iron pipes (for example where the aqueduct crossed a river, it would normally do so by an inverted syphon in pipes). Five diameter pipes would be provided to take the full per day, but initially only one pipe would be laid – others would be added as demand increased. The former secretary of the Duke of Richmond's Royal Commission gave evidence of the scheme they had considered, which involved raising the level of Thirlmere . Examination of the area around the outlet showed that Thirlmere had previously overflowed at a level higher than at present. evidence of Dr Pole Hence "it would only be necessary to dam up the present outlet ... to raise the lake to its original level"; were this done "the lake when filled will be more in keeping with the grandeur of the hills around" Variations in reservoir water level would only expose a gravel or shingle shore (as happened now with natural fluctuations in level): there was nothing in the water to support the formation of mudbanks. The commission had thought it would be unreasonable for London to take water from the Lakes without considering the needs of the industrial North; it had remarked favourably on Manchester supplying nearby towns as an instance of how by combination small towns might secure a better supply than they could by their own efforts. The same principle applied to supplying towns on the route of the aqueduct.=Independent witnesses

= A number of independent witnesses were then called by the committee. Professor Ramsay, Director-General of the Geological Survey of Great Britain, confirmed the previous higher level of the lake: Playfair said he considered the evidence of the 'degradation of the lake by the gorge being opened' most important. Robert Rawlinson, chief engineering inspector to the Local Government Board favoured the Thirlmere scheme (thirty years earlier he had proposed a similar scheme to supply Liverpool from Bala Lake) and vouched for the competence of Bateman.=Opposition on aesthetic grounds

= After calling witnesses with a straightforward ''locus standi'' under Private Bill standing orders and hearing their objections (detriment to salmon fishing in the Greta if floods and spates were eliminated, the dangers to gentlemen's residences from aqueduct bursts, interference of the aqueduct with natural drainage, and the undesirable disturbance from constructing the aqueduct through gentlemen's private pleasure grounds (and doing so on five occasions where pipes were used).) witnesses with aesthetic objections were heard. A Stourbridge solicitor owning a house and in Grasmere objected to the trace of the aqueduct as 'a great scar on the landscape'; he had laid out £1000 on building roads on his land in hopes of selling plots for the construction of houses: 'you may build houses without disfiguring the district', but the aqueduct would destroy the essential local feature of the district. A Keswick bank manager objected because the dam would be vulnerable to a waterspout, experienced in St John's Vale many times. He was supported by William Wordsworth (the only surviving son of the poet) who spoke of waterspouts at Rydal, and went on to object that raising the level of Thirlmere would remove its natural indentations: repeated attempts by him to dilate on the lake's associations with the Lake Poets were treated unsympathetically by counsel for Manchester and eventually ended by the committee chairman. Witnesses then testified to Thirlmere having a muddy bottom (but one said it was only found at more than down.) The brother (and heir) of the lord of the manor gave evidence that the beauty of Thirlmere lay in it being more secluded than other lakes: his counsel used his examination to suggest that Manchester Corporation was buying excessive amounts of land with a view to selling off building plots should the waterworks scheme be defeated. A Grasmere villa-owner likened the scheme to 'some modern Cockney' daubing paint on a picture in the National Gallery and claiming it to be an improvement; he predicted stinking mud around the edges of Thirlmere because that was what found around Grasmere. W E Forster held both that if Manchester needed water and could get it nowhere other than Thirlmere, the scheme should go ahead; but that - if it did - beauty more valuable than any picture that was or was to come would be lost to the people of England, who would not be recompensed by any amount of compensation to landed proprietors: Parliament should ensure that beauty was not lost unnecessarily. (Forster was not only a prominent politician with a house near Ambleside, but also a partner in a West Riding worsted manufacturer, and Beckett pressed him on why the generation of dust and smoke and 'turning rivers into ink' in the valleys of the West Riding was not in greater need of Parliamentary scrutiny than raising the level of Thirlmere was.)=Need for the Thirlmere scheme questioned

= Manchester's current and future needs for water were then disputed, the adequacy of the Thirlmere scheme queried, and alternative schemes for increasing the supply of water to Manchester suggested. Edward Hull, director of the Irish section of the Geological Survey, gave evidence on the ready availability of water from the New Red Sandstone aquifer around Manchester. He estimated that could yield a day; a single well would give up to a day. The Delamere Forest region, from Manchester, had of the sandstone and was untapped: it should be possible to extract a day from it. George Symons gave evidence on rainfall. He predicted that in the driest year, the rainfall at Thirlmere would be no more than ; about of this would be lost in evaporation, and Manchester were promising to maintain flows down St John's Beck equivalent to another . In cross-examination he conceded that he had had a rain gauge at Thirlmere since 1866 and the lowest annual rainfall it had recorded was ; re-examined he thought Manchester could not get a day from Thirlmere; the most they could rely upon was a day. Alderman King, the only Manchester alderman to have voted against the scheme, reported that since 1874 the water consumption had decreased and in his opinion Manchester's present supply was adequate for the next ten years. He pointed out that Bateman had originally suggested using Ullswater, rather than Thirlmere, as a reservoir, and had at the start of the Longdendale scheme been over-optimistic in his estimate of its cost and yield; he therefore thought the Thirlmere scheme imprudent from the point of view of Manchester ratepayers.Henry Marten

MICE

A mouse (: mice) is a small rodent. Characteristically, mice are known to have a pointed snout, small rounded ears, a body-length scaly tail, and a high breeding rate. The best known mouse species is the common house mouse (''Mus musculus' ...

thought that Manchester's high consumption in the early 1870s had been due to wastage; his calculations were that it would be fifteen years before Manchester needed more water. When it did, it could increase reservoir capacity in Longdendale; much of the rain falling there currently ran to waste. It might also be prudent to reduce the amount of 'compensation water' released from the Longdendale reservoirs to feed mills downstream, and to have contingency arrangements to pump water from the sandstone aquifer in time of drought He also objected to Manchester claiming so productive a source of water for itself, and doubted if it would deal fairly with other towns wanting Thirlmere water; if it did, the scheme would be of general public benefit. Playfair 'perhaps speaking more as a sanitarian' queried whether Liverpool was so sanitary a town as to be a good example of how Manchester might reduce consumption, and whether the existing restrictions on consumption in Manchester should not eased by increasing the water supply: Marten disagreed (if Liverpool was insanitary, it was because of the presence of foreigners, it being a seaport.)

=Alternative sources suggested

Edward Easton

agreed with Marten that the restrictions on consumption in Manchester were not too stringent and was astonished at Bateman's claim that there were no further suitable reservoir sites in Longdendale; in one weekend he had identified four or five suitable sites. After Longdendale there were other possible sites, amongst many others those on the headwaters of the Derbyshire Derwentbr>Thomas Fenwick

gave evidence on the practicality of using reservoirs on the Derwent, but had to admit that he did so based on the work of a one-weekend visit to the area, that the Derwent catchment area did not naturally belong to Manchester, and that the Derwent flowed past Chatsworth so any interference with its natural flow would have to be agreeable to the Duke of Devonshire. The Derwent valley was almost as beautiful as the lakes, but lacked a lake; its beauty would be improved by a reservoir. Aqueducts (like one he had built for Dewsbury) were scarcely visible once built, and much more care was now taken in the construction of dams; dam failure was a thing of the past. Playfair declined the offer of further evidence from Manchester on getting water from the Derwent catchment area, as its proponents had given no real detail, nor any notice to potential objectors: a brief comment by Bateman would suffice. Bateman was then re-examined on the possibility of increasing storage at Longdendale. Easton's suggestion of additional sites was 'utterly absurd'; all practicable sites were already taken: "He had been working in these valleys for nearly thirty years, and he thought he knew something more about them than a man who made a galloping journey over them in one day". Taking water from the Derwent catchment area would require a -long tunnel, and cost nearly as much as Thirlmere for half the yield.

=Closing submissions

= Counsel for the TDA conceded that if Manchester needed the water, then it must have it; but it had been shown the beauty of the lake would be greatly damaged, and therefore Manchester needed to show that there was no other way to meet its needs: it was not for the objectors to provide a worked-up alternative scheme. It had been shown there was no necessity; Manchester would not need more water for many years to come. The scheme had been brought forward to gratify the ambition of Manchester Corporation and Mr Bateman, its engineer. In purchasing land around Thirlmere they had exceeded their powers, as they had done for many years by supplying water outside their district, as though they were a commercial water company, not a municipal undertaking.Mr Cripps Bateman's calculations were based upon aiming to fully meet demand in a dry year, but failure to do so would cause only temporary inconvenience: one might as well build a railway entirely in a tunnel to ensure the line would not be blocked by snow. In any case, more storage could be provided in Longdendale and the Derwent headwaters, and more water could be extracted from the sandstone.Mr Cripps' further remarks He was followed by counsel for various local authorities, arguing against the Bill being passed without it laying any obligation on Manchester to supply water at a reasonable price to neighbouring authorities and to districts through which the aqueduct passed. As counsel for the TDA objected, these 'objectors' were - in everything but name - supporters of the scheme speaking in favour of it. Beckett began by attacking the aesthetic issue head-on. He objected to the false sentimentality of "people calling themselves learned, refined, and aesthetical, and thinking nobody had a right to an opinion but themselves", and in particular to Forster who thought himself entitled to talk about national sentiment and British interests as though there were no two views of the case. The lake had been higher in the past, and there was no good reason to think it would not look better covering than covering . Forster talked of Parliament interfering to protect natural beauty, just as it interfered to protect the commons, but the analogy failed: Forster wanted to interfere (on the basis of 'national sentiment') with the right of people to do they saw fit with their own property; this was communism. Forster was not even consistent: he saw no need for Parliament to have powers to prevent woollen mills being built at Thirlmere, and turning its waters as inky as the Wharfe. Aesthetics disposed of, the case became a simple one. Manchester was not undertaking the project because it loved power: nothing in the Bill increased its supply area by ; it sold water to other authorities because Parliament expected it to; it was nonsense to suggest that the town clerk of Manchester needed instruction on the legality of doing so. It was clear that the population of South Lancashire would continue to increase; it was absurd for counsel for the TDA to object to this as an unwarranted assumption upon which the argument that Manchester would need more water in the foreseeable future rested. As for the suggestion that more water might be got in Longdendale, this rested on overturning the settled views of an engineer with thirty years experience in the valley by a last-minute survey lasting under thirty hours by Mr Easton, whose conduct was shameful and scandalous. Other schemes had been floated; the Derwent, the Cheshire sandstone, but they were too hypothetical to be relied upon. The Thirlmere scheme, which by its boldness ensured cheap and plentiful water to South Lancashire for years to come, was the right solution. If it was rejected, Manchester would not pursue 'little schemes here and there, giving little sups of water'; they would wait until Parliament was of their turn of mind.Committee findings and loss of Bill

The committee agreed unanimously to pass the bill in principle, provided introduction of a clause allowing for arbitration on aesthetic issues on the line of the aqueduct, and of one requiring bulk supply of water (at a fair price) to towns and local authorities demanding it, if they were near the aqueduct (with Manchester and its supply area having first call on up to per head of population from Thirlmere and Longdendale combined.) Suitable clauses having been inserted, the committee stage of the bill was successfully completed 4 April 1878. The report of the committee said that * Manchester was justified in seeking additional sources of supply; there were already nearly a million inhabitants of its statutory supply area and a shortfall could arise within ten years. It would be unwise to expect any increase in the supply from Longdendale. The Derwent scheme was too costly (and given in insufficient detail) to require consideration, and it would be unjust to other Lancashire towns to allow Manchester to appropriate catchment areas closer than the Lakes. * Thirlmere was of great natural beauty. Formation of the reservoir would restore the lake to a former level; characteristic features would be lost, but new ones would be formed. The purchase of the land in the catchment area (with a view to preventing mines and villas) would preserve its natural state for generations to come; the construction of roads would make its beauty more accessible to the public. Fluctuations in level (except in prolonged drought) would not be significantly greater than the current natural variation, and (the margin of the lake being shingle, not mud) would be unimportant. Hence, "the water of Lake Thirlmere could be used without detriment to the public enjoyment of the lake". As for the aqueduct, beyond temporary inconvenience and unsightliness during construction, there would be little or no permanent injury to the scenery. * the interest of water authorities on or near the line of the aqueduct in securing a supply of water from it had been considered. In accordance with the recommendation of the Richmond Commission, an appropriate clause had been inserted, and the preamble of the bill adjusted accordingly. The Bill received its Third Reading in the Commons 10 May 1878 (the TDA, however, appealing to its supporters for £2,000 to fund further opposition in the Lords.) The TDA then objected that the Bill, as it left the Commons, did not meeting the standing orders of the House of Lords, as the required notice had not been given of the new clauses. This objection was upheld, and the Standing Orders Committee of the House of Lords therefore rejected the Bill.Bill of 1879

Manchester returned with another Thirlmere Bill in the next session: the council's decision to do so was endorsed by a town meeting and, when called for by opponents, a vote of ratepayers (43,362 votes for; 3524 against) The 1879 bill as first advertised was essentially the 1878 bill as it had left the Commons, with some additional concessions to the TDA (most notably that Thirlmere was never to be drawn down below its natural pre-reservoir level) being made later. In February 1879, Edward Howard introduced a motion calling for a select committee looking at the problems of water supply to Lancashire and Yorkshire (which would have prevented progress of the Thirlmere Bill until the select C committee had reported). In doing so, he criticised (without prior notice) the conduct of the hybrid committee of 1878. The President of the Local Government Board thought a royal commission unnecessary (much information had already been gathered and was freely available), and Howard's motion was too transparently an attempt to block the Thirlmere Bill. Forster regretted the decision of the hybrid committee, but it had been an able committee, and its conclusions should be respected. Playfair also defended the committee; it had (as required by the Commons) carefully examined the regional and public interest issues which a royal commission was now supposedly needed to re-examine properly. As a result of this, a clause had been introduced which made the bill effectively a public one; the Lords had then refused to consider the bill because the additional clauses fell foul of requirements for a purely private bill. Howard withdrew his motion. At committee stage, the preamble was unopposed and the only objector against the clauses was unsuccessful. Committee stage was completed 25 March 1879; the same objection was made at the Lords select committee, and was again unsuccessful; the bill receivedroyal assent

Royal assent is the method by which a monarch formally approves an act of the legislature, either directly or through an official acting on the monarch's behalf. In some jurisdictions, royal assent is equivalent to promulgation, while in othe ...

in May 1879.; it became Manchester Corporation Waterworks Act 1879 ( 42 & 43 Vict. c. xxxvi).

Conversion to Manchester's reservoir

The scheme on pause

The act set no time limit for completion of the work, but the compulsory purchase powers it gave were to expire at the end of 1886. There was no immediate shortage of water, and it was decided to undertake no engineering until purchasing of property and way-leaves was essentially complete. However, these were not pursued with any great urgency (especially after the replacement of the chairman of the waterworks committee, Alderman Grave), and 1884 Grave began a series of letters to the press calling for greater urgency. He was answered by Alderman King, long opposed to the scheme, who urged that it be dropped, pointing out that in 1881 the average daily consumption of water had been under a day, less than a day more than in 1875; on that basis not until 1901 would average daily consumption reach the limits of supply from Longdendale. In turn, Bateman (complaining "Where almost every statement is incorrect, and the conclusions, therefore, fallacious, it is difficult within any reasonable compass to deal with all") responded: the reassuring calculation reflected a recent period of trade depression and wet summers; the question was not of the average consumption over the year, but of the ability of supply and storage to meet demand in a hot and dry summer; as professional adviser to the water committee he would not have dared incurred the risk of failing to do so by delaying the start of work for so long. The waterworks committee steered a middle course; the Thirlmere scheme was not to be lost sight of, they argued in July 1884, but – in view of the current trade depression – it should not be unduly hastened. The summer of 1884 was, however, one of prolonged drought. At the start of July, after three months with little rain, there was still 107 days supply in the reservoirs; by the start of October there was no more than 21 days: "The great reservoirs… are, with one or two exceptions, empty - literally dry. The banks are parched, the beds of the huge basins are in many places sufficiently hard owing to the long continued absence of water to enable one to walk from one side to the other, or from end to end, almost without soiling one's boots." Furthermore, the water drawn down from the reservoirs had had 'a disagreeable and most offensive odour' The drought broke in October; it had lasted a month longer than that of 1868, but the water supply had not had to be turned off at night; the waterworks committee thought the council could congratulate itself on this but in January 1885 the committee sought, and the council (despite further argument by Alderman King) gave permission to commence the Thirlmere works.Construction work

The first phase was to construct the aqueduct with a capacity of a day, and to raise the level of Thirlmere by damming up its natural exit to the north. The engineer for the project was George Hill (formerly an assistant, and then partner of Bateman). Contracts for the aqueduct went out for tender in autumn 1885; by April 1886 excavation of the tunnels had begun and hutted camps had sprung up (at White Moss, and elsewhere) to house the army of navvies (who were paid 4d an hour): The original contractor suspended work in February 1887, and the contract had to be re-let. A further bill (supported by the Lake District Defence Society and Canon Rawnsley) was contemplated for 1889 to allow Thirlmere to be raised only 20 ft in the first instance, and defer improvement of the road on the west side of the lake but was not proceeded with. Boring of the tunnel under Dunmail Raise was completed in July 1890, and work then began on the dam at the north end of Thirlmere. There were then between five and six thousand men working on the Thirlmere project.

Before any supply from Thirlmere became available, there were two dry summers during which Manchester experienced a 'water famine'. The summer of 1887 was the driest for years, with stocks falling to 14 days' supply in early August, and the water supply consequently being cut off from 6 pm to 6 am. Stocks at the start of 1888 were markedly lower than in previous years, and as early as March 1888 the water supply was again cut off overnight (8pm-5am), but spring rain soon allowed a resumption of the constant supply. 1893 saw another dry summer, with stocks falling to twenty-four days' supply by the start of September and that – a councillor complained – of inferior quality with 'an abundance of animal life visible to the naked eye' in tap water. By now, the aqueduct and dam were complete, but under the 1879 Act the roads around Thirlmere had to be completed before any water could be taken from it. The summer of 1894 was wet, and starting to use Thirlmere water would mean charges of £10,000 a year; the opening was therefore delayed until October 1894. There were two opening ceremonies; one at Thirlmere followed next day in Manchester by the turning-on of water to a fountain in Albert Square.

The first phase was to construct the aqueduct with a capacity of a day, and to raise the level of Thirlmere by damming up its natural exit to the north. The engineer for the project was George Hill (formerly an assistant, and then partner of Bateman). Contracts for the aqueduct went out for tender in autumn 1885; by April 1886 excavation of the tunnels had begun and hutted camps had sprung up (at White Moss, and elsewhere) to house the army of navvies (who were paid 4d an hour): The original contractor suspended work in February 1887, and the contract had to be re-let. A further bill (supported by the Lake District Defence Society and Canon Rawnsley) was contemplated for 1889 to allow Thirlmere to be raised only 20 ft in the first instance, and defer improvement of the road on the west side of the lake but was not proceeded with. Boring of the tunnel under Dunmail Raise was completed in July 1890, and work then began on the dam at the north end of Thirlmere. There were then between five and six thousand men working on the Thirlmere project.

Before any supply from Thirlmere became available, there were two dry summers during which Manchester experienced a 'water famine'. The summer of 1887 was the driest for years, with stocks falling to 14 days' supply in early August, and the water supply consequently being cut off from 6 pm to 6 am. Stocks at the start of 1888 were markedly lower than in previous years, and as early as March 1888 the water supply was again cut off overnight (8pm-5am), but spring rain soon allowed a resumption of the constant supply. 1893 saw another dry summer, with stocks falling to twenty-four days' supply by the start of September and that – a councillor complained – of inferior quality with 'an abundance of animal life visible to the naked eye' in tap water. By now, the aqueduct and dam were complete, but under the 1879 Act the roads around Thirlmere had to be completed before any water could be taken from it. The summer of 1894 was wet, and starting to use Thirlmere water would mean charges of £10,000 a year; the opening was therefore delayed until October 1894. There were two opening ceremonies; one at Thirlmere followed next day in Manchester by the turning-on of water to a fountain in Albert Square.

Thirlmere as Manchester's reservoir

First phase: a day, lake above natural

For the next ten years, the level of Thirlmere was above that of the old lake: lowland pasturage was lost, but little housing. The straight level road on the east bank was favourably commented upon in accounts of cycling tours of the lakes, and it was widely thought – as James Lowther (MP for Penrith and the son of the Westmorland MP who had spoken against the 1878 bill at its Second Reading) said at the Third Reading of a Welsh private bill – "the beauty of Thirlmere had been improved" by the scheme. Thirlmere water reached Manchester through a single diameter cast iron pipe; due to leakage, only about 80% of the intended a day supply reached Manchester. and, as early as May 1895 more than half the additional supply was accounted for by increased consumption. The Manchester Corporation Act 1891 ( 54 & 55 Vict. c. ccvii) had allowed Manchester to specify water closets for all new buildings and modification of existing houses; Manchester now encouraged back-fitting of water closets and reduced the additional charge for baths. The average daily consumption in 1899 was a day, with being consumed in a single day at the end of August In June 1900, Manchester Corporation accepted the recommendation of its Waterworks Committee that a second pipe be laid from Thirlmere; it insisted that despite any potential shortfall in water supply a 'water-closet' policy should be continued. The first section of the second pipe was laid at Troutbeck in October 1900. Hill noted that it would take three or four years to complete the second pipe, at the current rate of increase of consumption as soon as the second pipe was completed it would be time to start on the third. In April 1901, the Longdendale reservoirs were 'practically full'; by mid-July they held only 49 days' supply, and it was thought prudent to cut off the water supply at night; by October stocks were down to 23 days', even though water was running to waste at Thirlmere In 1902, the constant supply was maintained throughout the summer and the Longdendale stocks never dropped below 55 days' consumption, but 1904 again saw the suspension of supply at night, with stocks falling as low as 17 day's supply at the start of November just before the second pipe came into use.Subsequent phases and consequent criticism

The second pipe could deliver a day, giving a total capacity of the aqueduct of a day. The water level was raised to 35 ft above natural; the area of the lake now increasing to . of Shoulthwaite Moss (north of Thirlmere) were reclaimed as winter pasture to compensate for the loss of acreage around Thirlmere. A third pipe was authorised in 1906, construction began in October 1908, and was completed in 1915: this increased the potential supply from Thirlmere to a day against an average daily demand which had now reached : in the summer of 1911 it had again been necessary to suspend the water supply at night. The lake was then raised to above natural; a fourth and final pipeline was completed in 1927, its authorisation having been delayed by the First World War until 1921; as early as 1918 Manchester Corporation had identified the need for a further source of water, and identified Haweswater as that source.

At the committee stage of Manchester's 1919 bill to tap Haweswater, the average daily demand on Manchester's water supply in 1917 was said to have been a day, with the reliable supply from Longdendale being no more than a day and Thirlmere being able to supply a day, which would rise to a day when the fourth pipe was laid. The aqueduct capacity could be increased to a day by laying a fifth pipe, but could not be increased beyond that whilst the aqueduct was still being used to deliver water to Manchester.

The second pipe could deliver a day, giving a total capacity of the aqueduct of a day. The water level was raised to 35 ft above natural; the area of the lake now increasing to . of Shoulthwaite Moss (north of Thirlmere) were reclaimed as winter pasture to compensate for the loss of acreage around Thirlmere. A third pipe was authorised in 1906, construction began in October 1908, and was completed in 1915: this increased the potential supply from Thirlmere to a day against an average daily demand which had now reached : in the summer of 1911 it had again been necessary to suspend the water supply at night. The lake was then raised to above natural; a fourth and final pipeline was completed in 1927, its authorisation having been delayed by the First World War until 1921; as early as 1918 Manchester Corporation had identified the need for a further source of water, and identified Haweswater as that source.