Third Voyage Of James Cook on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

On his last voyage, Cook once again commanded HMS ''Resolution''. ''Resolution'' began her career as the 462 ton

On his last voyage, Cook once again commanded HMS ''Resolution''. ''Resolution'' began her career as the 462 ton

Captain James Cook sailed from Plymouth on 12 July 1776. Clerke in the ''Discovery'' was delayed in London and did not follow until 1 August. On the way to Cape Town, the ''Resolution'' stopped at Tenerife to top off supplies. The ship reached Cape Town on 17 October, and Cook immediately had it re-caulked because it had been leaking very badly, especially through the main deck. When ''Discovery'' arrived on 10 November, she was also found to be in need of re-caulking.

The two ships sailed in company on 1 December and on 13 December located and named the

Captain James Cook sailed from Plymouth on 12 July 1776. Clerke in the ''Discovery'' was delayed in London and did not follow until 1 August. On the way to Cape Town, the ''Resolution'' stopped at Tenerife to top off supplies. The ship reached Cape Town on 17 October, and Cook immediately had it re-caulked because it had been leaking very badly, especially through the main deck. When ''Discovery'' arrived on 10 November, she was also found to be in need of re-caulking.

The two ships sailed in company on 1 December and on 13 December located and named the

After a month's stay, Cook got under sail to resume his exploration of the Northern Pacific. However, shortly after leaving Hawaii Island, the foremast of the ''Resolution'' broke and the ships returned to

After a month's stay, Cook got under sail to resume his exploration of the Northern Pacific. However, shortly after leaving Hawaii Island, the foremast of the ''Resolution'' broke and the ships returned to

Cook's account of his third and final voyage was completed upon their return by James King. Cook's own journal ended abruptly on 17 January 1779, but those of his crew were handed to the Admiralty for editing before publication. In anticipation of the publication of his journal, Cook had spent much shipboard time rewriting it.

The task of editing the account of the voyage was entrusted by the Admiralty to Dr John Douglas, Canon of St Paul's, who had the journals in his possession by November 1780. He added the journal of the surgeon, William Anderson, to the journals of Cook and James King. The final publication, in June 1784, amounted to three volumes, 1,617 pages, with 87 plates. Public interest in the account resulted in its selling out within three days, despite the high price of .

As on the earlier voyages, unofficial accounts written by members of the crew were produced. The first to appear, in 1781, was a narrative based on the journal of John Rickman entitled ''Journal of Captain Cook's Last Voyage''. The German translation ''Tagebuch einer Entdekkungs Reise nach der Südsee in den Jahren 1776 bis 1780 unter Anführung der Capitains Cook, Clerke, Gore und King'' by

Cook's account of his third and final voyage was completed upon their return by James King. Cook's own journal ended abruptly on 17 January 1779, but those of his crew were handed to the Admiralty for editing before publication. In anticipation of the publication of his journal, Cook had spent much shipboard time rewriting it.

The task of editing the account of the voyage was entrusted by the Admiralty to Dr John Douglas, Canon of St Paul's, who had the journals in his possession by November 1780. He added the journal of the surgeon, William Anderson, to the journals of Cook and James King. The final publication, in June 1784, amounted to three volumes, 1,617 pages, with 87 plates. Public interest in the account resulted in its selling out within three days, despite the high price of .

As on the earlier voyages, unofficial accounts written by members of the crew were produced. The first to appear, in 1781, was a narrative based on the journal of John Rickman entitled ''Journal of Captain Cook's Last Voyage''. The German translation ''Tagebuch einer Entdekkungs Reise nach der Südsee in den Jahren 1776 bis 1780 unter Anführung der Capitains Cook, Clerke, Gore und King'' by

Captain Cook Society

Website of illustrations and maps about Cook's third voyage * {{Authority control 1779 in Hawaii Expeditions from Great Britain Exploration of North America 3 Pre-Confederation British Columbia Pre-statehood history of Alaska Pre-statehood history of Hawaii Pre-statehood history of Oregon Pre-statehood history of Washington (state)

James Cook

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain James Cook (7 November 1728 – 14 February 1779) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer, and cartographer famous for his three voyages of exploration to the Pacific and Southern Oceans, conducted between 176 ...

's third and final voyage (12 July 1776 – 4 October 1780) was a British attempt to discover the Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea lane between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, near the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Arctic Archipelago of Canada. The eastern route along the Arctic ...

between the Atlantic ocean and the Pacific coast of North America. The attempt failed and Cook was killed at Hawaii in a violent dispute with the local inhabitants.

The ostensible purpose of the voyage was to return Omai

Mai ( 1753–1779), also known as Omai in Europe, was a young Ra'iatean man who became the first Pacific Islander to visit England, and the second to visit Europe, after Ahutoru who was brought to Paris by Bougainville in 1768.

Life

M ...

, a young man from Raiatea, to his homeland, but the British Admiralty

The Admiralty was a Departments of the Government of the United Kingdom, department of the Government of the United Kingdom that was responsible for the command of the Royal Navy.

Historically, its titular head was the Lord High Admiral of the ...

used this as a cover for their plan to send Cook on a voyage to find the Northwest Passage, should it exist. HMS ''Resolution'', to be commanded by Cook, and HMS ''Discovery'', commanded by Charles Clerke

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain Charles Clerke (22 August 1741 – 22 August 1779) was an officer in the Royal Navy who sailed on four voyages of exploration (including three circumnavigations), three with Captain James Cook. When Cook was killed ...

, were prepared for the voyage which started from Plymouth

Plymouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Devon, South West England. It is located on Devon's south coast between the rivers River Plym, Plym and River Tamar, Tamar, about southwest of Exeter and ...

in 1776.

After Omai was returned to his homeland, the ships sailed into the central Pacific where they encountered the hitherto unknown (to Europeans) Hawaiian Archipelago, before reaching the Pacific coast of North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

. After exploring and charting the northwest coast of the continent, they passed through the Bering Strait

The Bering Strait ( , ; ) is a strait between the Pacific and Arctic oceans, separating the Chukchi Peninsula of the Russian Far East from the Seward Peninsula of Alaska. The present Russia–United States maritime boundary is at 168° 58' ...

into the Arctic Ocean where they were eventually blocked by pack ice

Pack or packs may refer to:

Music

* Packs (band), a Canadian indie rock band

* ''Packs'' (album), by Your Old Droog

* ''Packs'', a Berner album

Places

* Pack, Styria, defunct Austrian municipality

* Pack, Missouri, United States (US)

* ...

. The vessels returned to the Pacific and called briefly at the Aleutians before Cook decided to return to the Hawaiian Islands for the winter.

At Kealakekua Bay

Kealakekua Bay is located on the Kona coast of the island of Hawaii about south of Kailua-Kona. Settled over a thousand years ago, the surrounding area contains many archeological and historical sites such as religious temples ( heiaus) an ...

, off the island of Hawaii, a number of quarrels broke out between the British and Hawaiians culminating in Cook's death in a violent exchange on 14 February 1779. The command of the expedition was assumed by Charles Clerke

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain Charles Clerke (22 August 1741 – 22 August 1779) was an officer in the Royal Navy who sailed on four voyages of exploration (including three circumnavigations), three with Captain James Cook. When Cook was killed ...

who again failed to find the Northwest Passage before his own death from tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

. Under the command of John Gore the crews returned to London in October 1780.

Conception

Cook's orders from the Admiralty were driven by a 1745 Act which, when extended in 1775, promised a £20,000 prize for whoever discovered the passage. Initially the Admiralty had wantedCharles Clerke

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain Charles Clerke (22 August 1741 – 22 August 1779) was an officer in the Royal Navy who sailed on four voyages of exploration (including three circumnavigations), three with Captain James Cook. When Cook was killed ...

to lead the expedition, with Cook, who was in retirement following his exploits in the Pacific, acting as a consultant. However, Cook had researched Bering's expeditions, and the Admiralty ultimately placed their faith in the veteran explorer to lead with Clerke accompanying him. The arrangement was to make a two-pronged attack, Cook moving from the Bering Strait

The Bering Strait ( , ; ) is a strait between the Pacific and Arctic oceans, separating the Chukchi Peninsula of the Russian Far East from the Seward Peninsula of Alaska. The present Russia–United States maritime boundary is at 168° 58' ...

in the north Pacific with Richard Pickersgill in the frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and maneuvera ...

''Lyon'' taking the Atlantic approach. They planned to rendezvous in the summer of 1778.

In August 1773, Omai

Mai ( 1753–1779), also known as Omai in Europe, was a young Ra'iatean man who became the first Pacific Islander to visit England, and the second to visit Europe, after Ahutoru who was brought to Paris by Bougainville in 1768.

Life

M ...

, a young Ra'iatean man, embarked from Huahine

Huahine is an island located among the Society Islands, in French Polynesia, an overseas territory of France in the Pacific Ocean, South Pacific Ocean. It is part of the Leeward Islands (Society Islands), Leeward Islands group ''(Îles sous le V ...

, travelling to Europe on ''Adventure'', commanded by Tobias Furneaux

Captain Tobias Furneaux (21 August 173518 September 1781) was a British navigator and Royal Navy officer, who accompanied James Cook on his second voyage of exploration. He was one of the first men to circumnavigate the world in both direction ...

who had touched at Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian language, Tahitian , ; ) is the largest island of the Windward Islands (Society Islands), Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of France. It is located in the central part of t ...

as part of James Cook's second voyage of discovery in the Pacific. He arrived in London in October 1774 and was introduced into society by the naturalist Sir Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, (19 June 1820) was an English Natural history, naturalist, botanist, and patron of the natural sciences.

Banks made his name on the European and American voyages of scientific exploration, 1766 natural-history ...

and became a favourite curiosity in London. Ostensibly, the third voyage was planned to return Omai to Tahiti; this is what the general public believed.

Preparation and personnel

Vessels and provisions

On his last voyage, Cook once again commanded HMS ''Resolution''. ''Resolution'' began her career as the 462 ton

On his last voyage, Cook once again commanded HMS ''Resolution''. ''Resolution'' began her career as the 462 ton North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

collier ''Marquis of Granby'', launched at Whitby

Whitby is a seaside town, port and civil parish in North Yorkshire, England. It is on the Yorkshire Coast at the mouth of the River Esk, North Yorkshire, River Esk and has a maritime, mineral and tourist economy.

From the Middle Ages, Whitby ...

in 1770, and purchased by the Royal Navy in 1771 for £4,151 and converted at a cost of £6,565. She was long and abeam. She was originally registered as HMS ''Drake''. After she returned to Britain in 1775 she had been paid off

Ship commissioning is the act or ceremony of placing a ship in active service and may be regarded as a particular application of the general concepts and practices of project commissioning. The term is most commonly applied to placing a warship i ...

but was then recommissioned in February 1776 for Cook's third voyage. The vessel had on board a quantity of livestock sent by George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

as gifts for the South Sea Islanders. These included sheep, cattle, goats and pigs as well as the more usual poultry. Cook also requisitioned "100 kersey jackets, 60 kersey waistcoats, 40 pairs of kersey breeches, 120 linsey waistcoats, 140 linsey drawers, 440 checkt shirts, 100 pair checkt draws, 400 frocks, 700 pairs of trowsers, 500 pairs of stockings, 80 worsted caps, 340 Dutch caps and 800 pairs of shoes."

Captain Charles Clerke

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain Charles Clerke (22 August 1741 – 22 August 1779) was an officer in the Royal Navy who sailed on four voyages of exploration (including three circumnavigations), three with Captain James Cook. When Cook was killed ...

commanded HMS ''Discovery'', which was a Whitby-built collier of 299 tons, originally named ''Diligence'' when she was built in 1774 by G. & N. Langborn for Mr. William Herbert from whom she was bought by the Admiralty. She was abeam with a hold depth of . She cost £2,415 including alterations. Originally a brig

A brig is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: two masts which are both square rig, square-rigged. Brigs originated in the second half of the 18th century and were a common type of smaller merchant vessel or warship from then until the l ...

, Cook had her changed to a full-rigged ship

A full-rigged ship or fully rigged ship is a sailing ship, sailing vessel with a sail plan of three or more mast (sailing), masts, all of them square rig, square-rigged. Such a vessel is said to have a ship rig or be ship-rigged, with each mas ...

.

Ships' companies

As his first lieutenant, Cook had John Gore, who had been round the world with him in the ''Endeavour'' and withSamuel Wallis

Post-captain, Captain Samuel Wallis (23 April 1728 – 21 January 1795) was a Royal Navy officer and explorer who made the first recorded visit by a European navigator to Tahiti.

Biography

Wallis was born at Fenteroon Farm, near Camelfo ...

in HMS ''Dolphin''. James King was his second officer and John Williamson third. The master was William Bligh

William Bligh (9 September 1754 – 7 December 1817) was a Vice-admiral (Royal Navy), Royal Navy vice-admiral and colonial administrator who served as the governor of New South Wales from 1806 to 1808. He is best known for his role in the Muti ...

, who would later command HMS ''Bounty''. William Anderson was surgeon and also acted as botanist, and the painter John Webber was the official artist. The crew included six midshipmen, a cook and a cook's mate, six quartermasters, twenty marines including a lieutenant, and forty-five able seamen.

''Discovery'' was commanded by Charles Clerke

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain Charles Clerke (22 August 1741 – 22 August 1779) was an officer in the Royal Navy who sailed on four voyages of exploration (including three circumnavigations), three with Captain James Cook. When Cook was killed ...

, who had previously served on Cook's first two expeditions and had previously sailed with John Byron. His first lieutenant was James Burney, his second John Rickman, his third John Williamson, and among the midshipmen was George Vancouver

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain George Vancouver (; 22 June 1757 – 10 May 1798) was a Royal Navy officer and explorer best known for leading the Vancouver Expedition, which explored and charted North America's northwestern West Coast of the Uni ...

, another veteran of Cook's second voyage. She had a crew of 70: 3 officers, 55 crew, 11 marines and one civilian.

Other crew members included:

* William Bayly served as astronomer

* Joseph Billings was an able seaman, first on ''Discovery'', later on ''Resolution''

* James Cleveley, brother of artists John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second E ...

and Robert

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of ''Hrōþ, Hruod'' () "fame, glory, honour, prais ...

, served as carpenter

* George Dixon served on ''Resolution'' as armourer

* John Ledyard

John Ledyard (November 1751 – 10 January 1789) was an American explorer and adventurer.

Early life

Ledyard was born in Groton, Connecticut, in November 1751. He was the first child of Abigail Youngs Ledyard and Capt. John Ledyard Jr, son o ...

, an American who served as a marine

* David Nelson was a botanical collector

* Omai

Mai ( 1753–1779), also known as Omai in Europe, was a young Ra'iatean man who became the first Pacific Islander to visit England, and the second to visit Europe, after Ahutoru who was brought to Paris by Bougainville in 1768.

Life

M ...

, a native of the island of Raiatea who had been brought to London on Cook's second voyage, acted as interpreter until he returned home

* Nathaniel Portlock served as master's mate on ''Discovery'' and later ''Resolution''

* Edward Riou

Edward Riou Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (20 November 17622 April 1801) was an officer of the Royal Navy who served during the French Revolutionary Wars under several of the most distinguished naval officers of his age and won fame and hono ...

was a midshipman on ''Discovery'' and later ''Resolution''

* Henry Roberts served as master's mate on Resolution. He prepared the charts for the official account of the voyage.

* David Samwell was surgeon's 1st mate on ''Resolution''

* William Taylor, midshipman on ''Resolution''

* James Trevenen, midshipman on ''Resolution''

* John Watts, midshipman on ''Resolution''

* Simon Woodruff, gunner's mate on ''Discovery''

Voyage

Captain James Cook sailed from Plymouth on 12 July 1776. Clerke in the ''Discovery'' was delayed in London and did not follow until 1 August. On the way to Cape Town, the ''Resolution'' stopped at Tenerife to top off supplies. The ship reached Cape Town on 17 October, and Cook immediately had it re-caulked because it had been leaking very badly, especially through the main deck. When ''Discovery'' arrived on 10 November, she was also found to be in need of re-caulking.

The two ships sailed in company on 1 December and on 13 December located and named the

Captain James Cook sailed from Plymouth on 12 July 1776. Clerke in the ''Discovery'' was delayed in London and did not follow until 1 August. On the way to Cape Town, the ''Resolution'' stopped at Tenerife to top off supplies. The ship reached Cape Town on 17 October, and Cook immediately had it re-caulked because it had been leaking very badly, especially through the main deck. When ''Discovery'' arrived on 10 November, she was also found to be in need of re-caulking.

The two ships sailed in company on 1 December and on 13 December located and named the Prince Edward Islands

The Prince Edward Islands are two small uninhabited subantarctic volcanic islands in the southern Indian Ocean that are administered by South Africa. They are named Marion Island (named after Marc-Joseph Marion du Fresne, 1724–1772) and P ...

. Twelve days later, Cook found the Kerguelen Islands

The Kerguelen Islands ( or ; in French commonly ' but officially ', ), also known as the Desolation Islands (' in French), are a group of islands in the subantarctic, sub-Antarctic region. They are among the Extremes on Earth#Remoteness, most i ...

, which he had failed to find on his second voyage. Driven by strong westerly winds, they reached Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the colonial name of the island of Tasmania during the European exploration of Australia, European exploration and colonisation of Australia in the 19th century. The Aboriginal Tasmanians, Aboriginal-inhabited island wa ...

on 26 January 1777, where they took on water and wood and became cursorily acquainted with the aborigines living there. The ships sailed on, arriving at Queen Charlotte Sound in New Zealand on 12 February. Here the Māori

Māori or Maori can refer to:

Relating to the Māori people

* Māori people of New Zealand, or members of that group

* Māori language, the language of the Māori people of New Zealand

* Māori culture

* Cook Islanders, the Māori people of the Co ...

were apprehensive because they believed that Cook would take revenge for the deaths in December 1773 of ten men from the ''Adventure'', commanded by Furneaux, on his second voyage. After two weeks, the ships left for Tahiti, but contrary winds carried them westward to Mangaia, where land was first sighted on 29 March. In order to re-provision, the ships went with the westerly winds to the Friendly Isles (now known as Tonga

Tonga, officially the Kingdom of Tonga, is an island country in Polynesia, part of Oceania. The country has 171 islands, of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in the southern Pacific Ocean. accordin ...

), stopping en route at Palmerston Island. They stayed in the Friendly Isles from 28 April until mid-July, when they set out for Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian language, Tahitian , ; ) is the largest island of the Windward Islands (Society Islands), Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of France. It is located in the central part of t ...

, arriving on 12 August and remaining for several weeks to supply and trade. In October 1777, Cook explored and obtained supplies on the island of Moʻorea

Moorea ( or ; , ), also spelled Moorea, is a volcanic island in French Polynesia. It is one of the Windward Islands (Society Islands), Windward Islands, a group that is part of the Society Islands, northwest of Tahiti. The name comes from the ...

. This was the first contact the islanders had with Europeans and on 6 October, one of Cook's goats was stolen while grazing ashore. After negotiations failed to return the goat, two large armed parties were sent ashore to set fire to houses and boats. Eventually, the goat was returned and Cook departed Mo'orea.

After returning Omai, Cook delayed his onward journey until 7 December, when he travelled north and on 18 January 1778 became the first European to visit the Hawaiian Islands

The Hawaiian Islands () are an archipelago of eight major volcanic islands, several atolls, and numerous smaller islets in the Pacific Ocean, North Pacific Ocean, extending some from the Hawaii (island), island of Hawaii in the south to nort ...

. In passing and after initial landfall at Waimea harbour, Kauai

Kauai (), anglicized as Kauai ( or ), is one of the main Hawaiian Islands.

It has an area of 562.3 square miles (1,456.4 km2), making it the fourth-largest of the islands and the 21st-largest island in the United States. Kauai lies 73 m ...

, Cook named the archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands. An archipelago may be in an ocean, a sea, or a smaller body of water. Example archipelagos include the Aegean Islands (the o ...

the "Sandwich Islands" after the fourth Earl of Sandwich—the acting First Lord of the Admiralty

First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the title of the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible f ...

. They observed that the inhabitants spoke a version of the Polynesian language familiar to them from their previous travels in the South Pacific. On 20 January 1778 a violent encounter took place on one of the small boats ashore. A local resident was killed with gunfire by lieutenant Williamson following a confrontation in which islanders attempted to board the small boats. Despite an order not to use lethal force while away from the main ship, Williamson argued there had been a threat to the crews life and to the ship's property and Cook did not issue a reprimand.

From Hawaii, Cook went northeast on 2 February to explore the west coast of North America north of the Spanish settlements in Alta California

Alta California (, ), also known as Nueva California () among other names, was a province of New Spain formally established in 1804. Along with the Baja California peninsula, it had previously comprised the province of , but was made a separat ...

. He made landfall on 6 March at approximately 44°30′ north latitude, near Cape Foulweather

Cape Foulweather is a basalt outcropping above the Pacific Ocean on the central coastline of the U.S. state of Oregon - in Lincoln County, south of Depoe Bay. It is bisected by US Highway 101, with a pass elevation of approximately , which ...

on the Oregon coast, which he named. Bad weather forced his ships south to about 43° north before they could begin their exploration of the coast northward. He unknowingly sailed past the Strait of Juan de Fuca

The Strait of Juan de Fuca (officially named Juan de Fuca Strait in Canada) is a body of water about long that is the Salish Sea's main outlet to the Pacific Ocean. The Canada–United States border, international boundary between Canada and the ...

and soon after entered Nootka Sound

Nootka Sound () is a sound of the Pacific Ocean on the rugged west coast of Vancouver Island, in the Pacific Northwest, historically known as King George's Sound. It separates Vancouver Island and Nootka Island, part of the Canadian province of ...

on Vancouver Island

Vancouver Island is an island in the northeastern Pacific Ocean and part of the Canadian province of British Columbia. The island is in length, in width at its widest point, and in total area, while are of land. The island is the largest ...

. He anchored near the First Nations

First nations are indigenous settlers or bands.

First Nations, first nations, or first peoples may also refer to:

Indigenous groups

*List of Indigenous peoples

*First Nations in Canada, Indigenous peoples of Canada who are neither Inuit nor Mé ...

village of Yuquot. Cook's two ships spent about a month in Nootka Sound, from 29 March to 26 April 1778, in what Cook called Ship Cove, now Resolution Cove, at the south end of Bligh Island, about east across Nootka Sound from Yuquot, a Nuu-chah-nulth

The Nuu-chah-nulth ( ; ), also formerly referred to as the Nootka, Nutka, Aht, Nuuchahnulth or Tahkaht, are one of the Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast in Canada. The term Nuu-chah-nulth is used to describe fifteen related tri ...

village (whose chief Cook did not identify but may have been Maquinna). Relations between Cook's crew and the people of Yuquot were cordial if sometimes strained. In trading, the people of Yuquot demanded much more valuable items than the usual trinkets that had worked for Cook's crew in Hawaii. Metal objects were much desired, but the lead, pewter, and tin traded at first soon fell into disrepute. The most valuable items the British received in trade were sea otter

The sea otter (''Enhydra lutris'') is a marine mammal native to the coasts of the northern and eastern Pacific Ocean, North Pacific Ocean. Adult sea otters typically weigh between , making them the heaviest members of ...

pelts. Over the month-long stay the Yuquot "hosts" essentially controlled the trade with the British vessels, instead of vice versa. Generally the natives visited the British vessels at Resolution Cove instead of the British visiting the village of Yuquot at Friendly Cove.

After leaving Nootka Sound, Cook explored and mapped the coast all the way to the Bering Strait

The Bering Strait ( , ; ) is a strait between the Pacific and Arctic oceans, separating the Chukchi Peninsula of the Russian Far East from the Seward Peninsula of Alaska. The present Russia–United States maritime boundary is at 168° 58' ...

, on the way identifying what came to be known as Cook Inlet

Cook Inlet (; Sugpiaq language, Sugpiaq: ''Cungaaciq'') stretches from the Gulf of Alaska to Anchorage, Alaska, Anchorage in south-central Alaska. Cook Inlet branches into the Knik Arm and Turnagain Arm at its northern end, almost surrounding ...

in Alaska. It has been said that, in a single visit, Cook charted the majority of the North American northwest coastline on world maps for the first time, determined the extent of Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

, and closed the gap between the Russian (from the west) and Spanish (from the south) exploratory probes of the northern limits of the Pacific.

By the second week of August 1778, Cook was through the Bering Strait, sailing into the Chukchi Sea

The Chukchi Sea (, ), sometimes referred to as the Chuuk Sea, Chukotsk Sea or the Sea of Chukotsk, is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean. It is bounded on the west by the Long Strait, off Wrangel Island, and in the east by Point Barrow, Alaska, ...

. He headed northeast up the coast of Alaska until he was blocked by sea ice at a latitude of 70°44′ north. Cook then sailed west to the Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

n coast, where he was unable to pass a point he called Cape North, today's Cape Schmidt

Cape Schmidt (; ''Mys Shmidta'' or Мыс Отто Шмидта; ''Mys Otto Shmidta''; Chukchi: Ир-Каппея; ''Ir-Kappeya''), formerly known as Cape North, is a headland in the Chukchi Sea, part of Iultinsky District of the Chukotka Autono ...

. He then followed the Siberian coast southeast back to the Bering Strait. By early September 1778 he was back in the Bering Sea

The Bering Sea ( , ; rus, Бе́рингово мо́ре, r=Béringovo móre, p=ˈbʲerʲɪnɡəvə ˈmorʲe) is a marginal sea of the Northern Pacific Ocean. It forms, along with the Bering Strait, the divide between the two largest landmasse ...

to begin the trip to the Sandwich (Hawaiian) Islands. He became increasingly frustrated on this voyage, and perhaps began to suffer from a stomach ailment; it has been speculated that this led to irrational behaviour towards his crew, such as forcing them to eat walrus

The walrus (''Odobenus rosmarus'') is a large pinniped marine mammal with discontinuous distribution about the North Pole in the Arctic Ocean and subarctic seas of the Northern Hemisphere. It is the only extant species in the family Odobeni ...

meat, which they found inedible. From the Bering Strait the crews went south to Unalaska in the Aleutians where Cook put in on 2 October to again re-caulk the ship's leaking timbers. During a three-week stay they met Russian traders and got to know the native population. The vessels left for the Sandwich Islands on 24 October, sighting Maui

Maui (; Hawaiian language, Hawaiian: ) is the second largest island in the Hawaiian archipelago, at 727.2 square miles (1,883 km2). It is the List of islands of the United States by area, 17th-largest in the United States. Maui is one of ...

on 26 November 1778.

The two vessels sailed around the Hawaiian Archipelago for some eight weeks looking for a suitable anchorage, until they made landfall at Kealakekua Bay

Kealakekua Bay is located on the Kona coast of the island of Hawaii about south of Kailua-Kona. Settled over a thousand years ago, the surrounding area contains many archeological and historical sites such as religious temples ( heiaus) an ...

, on the west coast of Hawaii Island, the largest island in the group, on 17 January 1779. During their navigation around the islands, the ships were accompanied by large numbers of gift-laden canoes whose occupants came fearlessly aboard the vessels. Palea, a chief, and Koa'a, a priest, came aboard and ceremoniously escorted Cook ashore where he was put through a long and peculiar ceremony before being allowed back to the ship. Unbeknown to Cook, his arrival coincided with the Makahiki, a Hawaiian harvest festival

A harvest festival is an annual Festival, celebration that occurs around the time of the main harvest of a given region. Given the differences in climate and crops around the world, harvest festivals can be found at various times at different ...

of worship for the Polynesian god Lono. Coincidentally, the form of Cook's ship, HMS ''Resolution''—specifically the mast formation, sails, and rigging—resembled certain significant artefacts that formed part of the season of worship. Similarly, Cook's clockwise route around the island of Hawaii before making landfall resembled the processions that took place in a clockwise direction around the island during the Lono festivals. It has been argued that such coincidences were the reasons for Cook's (and to a limited extent, his crew's) initial deification

Apotheosis (, ), also called divinization or deification (), is the glorification of a subject to divine levels and, commonly, the treatment of a human being, any other living thing, or an abstract idea in the likeness of a deity.

The origina ...

by some Hawaiians who treated Cook as an incarnation of Lono. Though this view was first suggested by members of Cook's expedition, the idea that any Hawaiians understood Cook to be Lono, and the evidence presented in support of it has been challenged.

Death

After a month's stay, Cook got under sail to resume his exploration of the Northern Pacific. However, shortly after leaving Hawaii Island, the foremast of the ''Resolution'' broke and the ships returned to

After a month's stay, Cook got under sail to resume his exploration of the Northern Pacific. However, shortly after leaving Hawaii Island, the foremast of the ''Resolution'' broke and the ships returned to Kealakekua Bay

Kealakekua Bay is located on the Kona coast of the island of Hawaii about south of Kailua-Kona. Settled over a thousand years ago, the surrounding area contains many archeological and historical sites such as religious temples ( heiaus) an ...

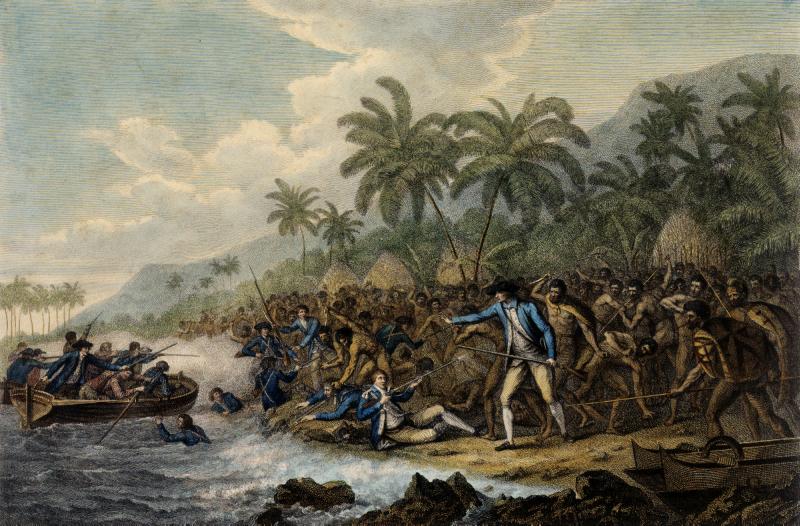

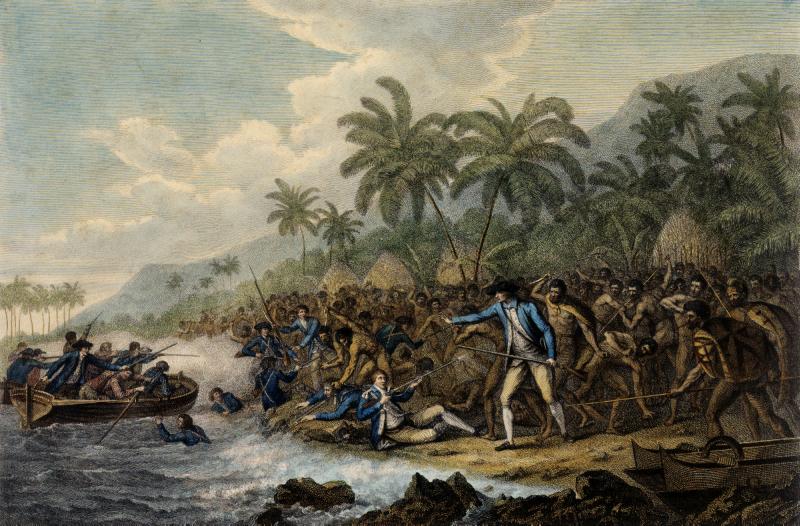

for repairs. It has been hypothesised that the return to the islands by Cook's expedition was not just unexpected by the Hawaiians, but also unwelcome because the season of Lono had recently ended (presuming that they associated Cook with Lono and Makahiki). In any case, tensions rose and a number of quarrels broke out between the Europeans and Hawaiians. On 14 February at Kealakekua Bay, some Hawaiians took one of Cook's small boats. Normally, as thefts were quite common in Tahiti and the other islands, Cook would have taken hostages until the stolen articles were returned.

Indeed, he attempted to take hostage the King of Hawaiʻi, Kalaniʻōpuʻu

Kalaniōpuu-a-Kaiamamao (c. 1729 – April 1782) was the aliʻi nui (supreme monarch) of the island of Hawaiʻi. He was called ''Terreeoboo, King of Owhyhee'' by James Cook and other Europeans. His name has also been written as Kaleiopuu.

Bio ...

. The Hawaiians prevented this when they spotted Cook luring King Kalaniʻōpuʻu to his ship on a false pretext and sounded the alarm. Kalaniʻōpuʻu himself eventually realized Cook's real intentions and suddenly stopped and sat where he stood. Before Cook could force the king back up, hundreds of native Hawaiians, some armed with weapons, appeared and began an angry pursuit, and Cook's men had to retreat to the beach. As Cook turned his back to help launch the boats, he was struck on the head by the villagers and then stabbed to death as he fell on his face in the surf. Hawaiian tradition says he was killed by a chief named Kalanimanokahoowaha. The Hawaiians dragged his body away. Four marines, Corporal James Thomas, Private Theophilus Hinks, Private Thomas Fatchett, and Private John Allen, were also killed, and two others were wounded in the confrontation.

The esteem in which he was nevertheless held by the Hawaiians caused their chiefs and elders to retain his body. Following the practice of the time, Cook's body underwent funerary rituals similar to those reserved for the chiefs and highest elders of the society. The body was disembowelled and baked to facilitate removal of the flesh, and the bones were carefully cleaned for preservation as religious icons in a fashion somewhat reminiscent of the treatment of European saints in the Middle Ages. Some of Cook's remains, disclosing some corroborating evidence to this effect, were eventually returned to the British for a formal burial at sea

Burial at sea is the disposal of Cadaver, human remains in the ocean, normally from a ship, boat or aircraft. It is regularly performed by navies, and is done by private citizens in many countries.

Burial-at-sea services are conducted at many di ...

following an appeal by the crew.

Homeward voyage

Clerke, who was dying oftuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

, took over the expedition and sailing north, landed on the Kamchatka Peninsula

The Kamchatka Peninsula (, ) is a peninsula in the Russian Far East, with an area of about . The Pacific Ocean and the Sea of Okhotsk make up the peninsula's eastern and western coastlines, respectively.

Immediately offshore along the Pacific ...

where the Russians helped him with supplies and to make repairs to the ships. He made a final attempt to pass beyond the Bering Strait and died on his return at Petropavlovsk on 22 August 1779. From here the ships' reports were sent overland, reaching London five months later. Following the death of Clerke, ''Resolution'' and ''Discovery'' turned for home commanded by John Gore, a veteran of Cook's first voyage (and now in command of the expedition), and James King. After passing down the coast of Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

they reached Macau

Macau or Macao is a special administrative regions of China, special administrative region of the People's Republic of China (PRC). With a population of about people and a land area of , it is the most List of countries and dependencies by p ...

, in China in the first week of December and from there followed the East India trade route

A trade route is a logistical network identified as a series of pathways and stoppages used for the commercial transport of cargo. The term can also be used to refer to trade over land or water. Allowing goods to reach distant markets, a singl ...

via Sunda Strait

The Sunda Strait () is the strait between the Indonesian islands of Java island, Java and Sumatra. It connects the Java Sea with the Indian Ocean.

Etymology

The strait takes its name from the Sunda Kingdom, which ruled the western portion of Ja ...

to Cape Town.

Return home

An Atlantic gale blew the expedition so far north that they first made landfall atStromness

Stromness (, ; ) is the second-most populous town in Orkney, Scotland. It is in the southwestern part of Mainland, Orkney. It is a burgh with a parish around the outside with the town of Stromness as its capital.

Etymology

The name "Stromnes ...

in Orkney

Orkney (), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago off the north coast of mainland Scotland. The plural name the Orkneys is also sometimes used, but locals now consider it outdated. Part of the Northern Isles along with Shetland, ...

. The ''Resolution'' and ''Discovery'' arrived off Sheerness

Sheerness () is a port town and civil parish beside the mouth of the River Medway on the north-west corner of the Isle of Sheppey in north Kent, England. With a population of 13,249, it is the second largest town on the island after the nearby ...

on 4 October 1780. The news of Cook's and Clerke's deaths had already reached London, so their homecoming was to a subdued welcome.

Publication of journals

Cook's account of his third and final voyage was completed upon their return by James King. Cook's own journal ended abruptly on 17 January 1779, but those of his crew were handed to the Admiralty for editing before publication. In anticipation of the publication of his journal, Cook had spent much shipboard time rewriting it.

The task of editing the account of the voyage was entrusted by the Admiralty to Dr John Douglas, Canon of St Paul's, who had the journals in his possession by November 1780. He added the journal of the surgeon, William Anderson, to the journals of Cook and James King. The final publication, in June 1784, amounted to three volumes, 1,617 pages, with 87 plates. Public interest in the account resulted in its selling out within three days, despite the high price of .

As on the earlier voyages, unofficial accounts written by members of the crew were produced. The first to appear, in 1781, was a narrative based on the journal of John Rickman entitled ''Journal of Captain Cook's Last Voyage''. The German translation ''Tagebuch einer Entdekkungs Reise nach der Südsee in den Jahren 1776 bis 1780 unter Anführung der Capitains Cook, Clerke, Gore und King'' by

Cook's account of his third and final voyage was completed upon their return by James King. Cook's own journal ended abruptly on 17 January 1779, but those of his crew were handed to the Admiralty for editing before publication. In anticipation of the publication of his journal, Cook had spent much shipboard time rewriting it.

The task of editing the account of the voyage was entrusted by the Admiralty to Dr John Douglas, Canon of St Paul's, who had the journals in his possession by November 1780. He added the journal of the surgeon, William Anderson, to the journals of Cook and James King. The final publication, in June 1784, amounted to three volumes, 1,617 pages, with 87 plates. Public interest in the account resulted in its selling out within three days, despite the high price of .

As on the earlier voyages, unofficial accounts written by members of the crew were produced. The first to appear, in 1781, was a narrative based on the journal of John Rickman entitled ''Journal of Captain Cook's Last Voyage''. The German translation ''Tagebuch einer Entdekkungs Reise nach der Südsee in den Jahren 1776 bis 1780 unter Anführung der Capitains Cook, Clerke, Gore und King'' by Johann Reinhold Forster

Johann Reinhold Forster (; 22 October 1729 – 9 December 1798) was a German Reformed pastor and naturalist. Born in Tczew, Dirschau, Pomeranian Voivodeship (1466–1772), Pomeranian Voivodeship, Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (now Tczew, Po ...

appeared in the same year. Heinrich Zimmermann published in 1781 his diary ''Reise um die Welt mit Capitain Cook''. Then in 1782 an account by William Ellis, Surgeon's Mate on the ''Discovery'', was published, followed in 1783 by John Ledyard

John Ledyard (November 1751 – 10 January 1789) was an American explorer and adventurer.

Early life

Ledyard was born in Groton, Connecticut, in November 1751. He was the first child of Abigail Youngs Ledyard and Capt. John Ledyard Jr, son o ...

's ''A Journal of Captain Cook's Last Voyage'' published in Connecticut

Connecticut ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. ...

.

References

Citations

General bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * *External links

Captain Cook Society

Website of illustrations and maps about Cook's third voyage * {{Authority control 1779 in Hawaii Expeditions from Great Britain Exploration of North America 3 Pre-Confederation British Columbia Pre-statehood history of Alaska Pre-statehood history of Hawaii Pre-statehood history of Oregon Pre-statehood history of Washington (state)