Thescelosaurus Filamented on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Thescelosaurus'' ( ) is a

Gilmore published a comprehensive description in 1915 after the type specimen was fully

Gilmore published a comprehensive description in 1915 after the type specimen was fully

In his 1995 revision, Galton also reassigned isolated teeth from the

In his 1995 revision, Galton also reassigned isolated teeth from the  After the discovery of additional specimens of ''Thescelosaurus'' preserving both the skull and skeleton, Clint Boyd and colleagues reassessed the historic and current species of ''Thescelosaurus'' in 2009. One of the new specimens ( MOR 979) was found in the Hell Creek of Montana and preserves a nearly complete skull and skeleton. The researchers also identified previously overlooked skull material of the ''T. neglectus'' paratype USNM 7758, which allowed comparisons of the diagnostic regions of the skull and ankle across multiple specimens and species. The key specimen, however, was NCSM 15728, nicknamed "Willo", which was found in the upper Hell Creek Formation in Harding County, South Dakota by Michael Hammer in 1999. This specimen preserves most of the skeleton and a mass in the chest cavity that was initially interpreted as a heart. "Willo" also includes a complete skull, showing that it was much lower and longer than previously thought. "Willo" and the other new specimens made it clear that ''Bugenasaura infernalis'' must be assigned to ''Thescelosaurus''. By reassigning the species, Boyd and colleagues created the new combination ''T. infernalis'' which they considered undiagnostic.

After the discovery of additional specimens of ''Thescelosaurus'' preserving both the skull and skeleton, Clint Boyd and colleagues reassessed the historic and current species of ''Thescelosaurus'' in 2009. One of the new specimens ( MOR 979) was found in the Hell Creek of Montana and preserves a nearly complete skull and skeleton. The researchers also identified previously overlooked skull material of the ''T. neglectus'' paratype USNM 7758, which allowed comparisons of the diagnostic regions of the skull and ankle across multiple specimens and species. The key specimen, however, was NCSM 15728, nicknamed "Willo", which was found in the upper Hell Creek Formation in Harding County, South Dakota by Michael Hammer in 1999. This specimen preserves most of the skeleton and a mass in the chest cavity that was initially interpreted as a heart. "Willo" also includes a complete skull, showing that it was much lower and longer than previously thought. "Willo" and the other new specimens made it clear that ''Bugenasaura infernalis'' must be assigned to ''Thescelosaurus''. By reassigning the species, Boyd and colleagues created the new combination ''T. infernalis'' which they considered undiagnostic.

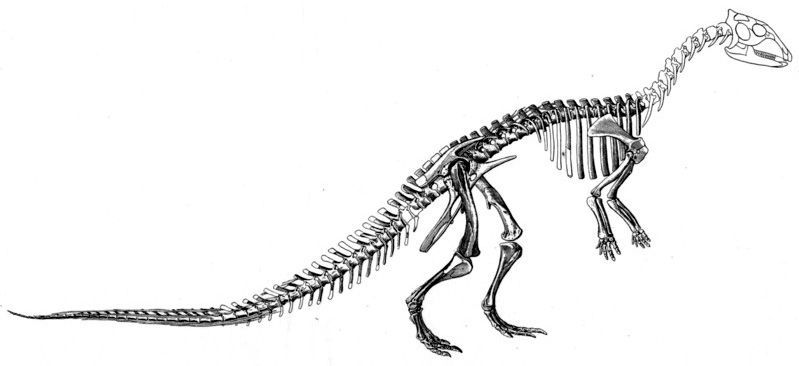

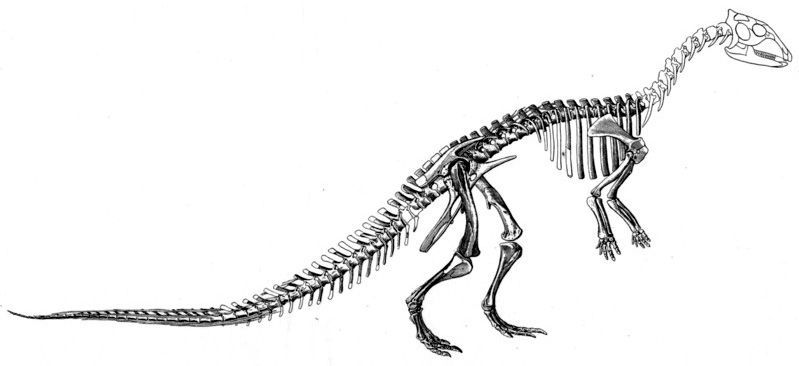

The skeletal anatomy of this genus is well documented overall, and restorations have been published in several papers, including skeletal restorations and models. The skeleton is known well enough that a detailed reconstruction of the hip and hindlimb muscles has been made. The largest known thescelosaurid, its body length has been estimated at and the weight at , with the large type specimen of ''T. garbanii'' estimated at long. It may have been

The skeletal anatomy of this genus is well documented overall, and restorations have been published in several papers, including skeletal restorations and models. The skeleton is known well enough that a detailed reconstruction of the hip and hindlimb muscles has been made. The largest known thescelosaurid, its body length has been estimated at and the weight at , with the large type specimen of ''T. garbanii'' estimated at long. It may have been

For most of its history, the nature of this genus'

For most of its history, the nature of this genus'

The concept of Hypsilophodontidae as a monophyletic group then fell out of favor. Rodney Sheetz suggested in 1999 that "hypsilophodontids" were simply the primitive forms of ornithopods, the larger grouping to which they were commonly assigned. Scheetz found ''Thescelosaurus'', ''Parksosaurus'' and ''Bugenasaura'' to be successively closer to ''Hypsilophodon'' and later ornithopods, but not a group of their own. Other studies had similar results, with ''Thescelosaurus'' or ''Bugenasaura'' as early ornithopods close to the origin of the group, sometimes forming a clade with ''Parksosaurus''. An issue with ''T. neglectus'' prior to the revision by Boyd and colleagues in 2009 was the uncertainty about the assigned specimens, including the separation of ''Bugenasaura'' and the unresolved question of whether ''T. edmontonensis'' was distinct or not. Following their taxonomic revision, the systematic relationships of ''Thescelosaurus'' and "hypsilophodonts" have become clearer, and Boyd and colleagues found support for a larger group of early ornithopods consisting of ''Thescelosaurus'', ''Parksosaurus'', ''Zephyrosaurus'', '' Orodromeus'' and '' Oryctodromeus''. Brown and colleagues, while describing ''T. assiniboiensis'' in 2011, came to similar results. The same authors confirmed these results again in 2013, prompting them to reintroduce the name Thescelosauridae for the entire group, which was divided into the revised subfamily Thescelosaurinae and the new subfamily Orodrominae.

Other studies did not find ''Parksosaurus'' to be closely related to ''Thescelosaurus'', and instead proposed that it was related to the South American ''

The concept of Hypsilophodontidae as a monophyletic group then fell out of favor. Rodney Sheetz suggested in 1999 that "hypsilophodontids" were simply the primitive forms of ornithopods, the larger grouping to which they were commonly assigned. Scheetz found ''Thescelosaurus'', ''Parksosaurus'' and ''Bugenasaura'' to be successively closer to ''Hypsilophodon'' and later ornithopods, but not a group of their own. Other studies had similar results, with ''Thescelosaurus'' or ''Bugenasaura'' as early ornithopods close to the origin of the group, sometimes forming a clade with ''Parksosaurus''. An issue with ''T. neglectus'' prior to the revision by Boyd and colleagues in 2009 was the uncertainty about the assigned specimens, including the separation of ''Bugenasaura'' and the unresolved question of whether ''T. edmontonensis'' was distinct or not. Following their taxonomic revision, the systematic relationships of ''Thescelosaurus'' and "hypsilophodonts" have become clearer, and Boyd and colleagues found support for a larger group of early ornithopods consisting of ''Thescelosaurus'', ''Parksosaurus'', ''Zephyrosaurus'', '' Orodromeus'' and '' Oryctodromeus''. Brown and colleagues, while describing ''T. assiniboiensis'' in 2011, came to similar results. The same authors confirmed these results again in 2013, prompting them to reintroduce the name Thescelosauridae for the entire group, which was divided into the revised subfamily Thescelosaurinae and the new subfamily Orodrominae.

Other studies did not find ''Parksosaurus'' to be closely related to ''Thescelosaurus'', and instead proposed that it was related to the South American ''

Like other ornithischians, ''Thescelosaurus'' was probably herbivorous. The different types of teeth, as well as the narrow snout, suggest that it was a selective feeder. The contemporary pachycephalosaur ''

Like other ornithischians, ''Thescelosaurus'' was probably herbivorous. The different types of teeth, as well as the narrow snout, suggest that it was a selective feeder. The contemporary pachycephalosaur ''

A 2023 study by David Button and Lindsay Zanno concluded that ''Thescelosaurus'' was less adapted for running than other thescelosaurids but nonetheless showed two traits that are common in runners. The first of these is the

A 2023 study by David Button and Lindsay Zanno concluded that ''Thescelosaurus'' was less adapted for running than other thescelosaurids but nonetheless showed two traits that are common in runners. The first of these is the

Button and Zanno, in 2023, discussed the sensory and cognitive abilities of ''Thescelosaurus'' based on a CT scan of the skull of the "Willo" specimen. Even though the brain itself is not preserved, the skull vault that contained the brain, the

Button and Zanno, in 2023, discussed the sensory and cognitive abilities of ''Thescelosaurus'' based on a CT scan of the skull of the "Willo" specimen. Even though the brain itself is not preserved, the skull vault that contained the brain, the

In 2000, the imaging specialist Paul Fisher and colleagues interpreted a concretion in the chest region of the "Willo" specimen as the remnant of a

In 2000, the imaging specialist Paul Fisher and colleagues interpreted a concretion in the chest region of the "Willo" specimen as the remnant of a

''Thescelosaurus'' is definitively known only from deposits in western North America dating to the late

''Thescelosaurus'' is definitively known only from deposits in western North America dating to the late

''Thescelosaurus'' was historically thought to be relatively uncommon in its paleoenvironments. A 1987 study estimated that hypsilophodontids (including ''Thescelosaurus'') and

''Thescelosaurus'' was historically thought to be relatively uncommon in its paleoenvironments. A 1987 study estimated that hypsilophodontids (including ''Thescelosaurus'') and

Paleoenvironments of the Scollard and Hell Creek formation show that the very end of the Cretaceous was intermediate between

Paleoenvironments of the Scollard and Hell Creek formation show that the very end of the Cretaceous was intermediate between  Many fossil vertebrates are found in the Scollard Formation alongside ''Thescelosaurus'', including

Many fossil vertebrates are found in the Scollard Formation alongside ''Thescelosaurus'', including

genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

of ornithischian

Ornithischia () is an extinct clade of mainly herbivorous dinosaurs characterized by a pelvic structure superficially similar to that of birds. The name ''Ornithischia'', or "bird-hipped", reflects this similarity and is derived from the Greek st ...

dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic Geological period, period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the #Evolutio ...

that lived during the Late Cretaceous

The Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma) is the more recent of two epochs into which the Cretaceous Period is divided in the geologic time scale. Rock strata from this epoch form the Upper Cretaceous Series. The Cretaceous is named after ''cre ...

period

Period may refer to:

Common uses

* Period (punctuation)

* Era, a length or span of time

*Menstruation, commonly referred to as a "period"

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Period (music), a concept in musical composition

* Periodic sentence (o ...

in western North America. It was named and described in 1913 by the paleontologist

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure geolo ...

Charles W. Gilmore

Charles Whitney Gilmore (March 11, 1874 – September 27, 1945) was an American paleontologist who gained renown in the early 20th century for his work on vertebrate fossils during his career at the United States National Museum (now the N ...

; the type species

In International_Code_of_Zoological_Nomenclature, zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the spe ...

is ''T. neglectus''. Two other species, ''T. garbanii'' and ''T. assiniboiensis'', were named in 1976 and 2011, respectively. Additional species have been suggested but are currently not accepted. ''Thescelosaurus'' is the eponymous member of its family, the Thescelosauridae

Thescelosauridae is a clade of neornithischians from the Cretaceous of East Asia and North America. The group was originally used as a name by Charles M. Sternberg in 1937, but was not formally defined until 2013, where it was used by Brown and ...

. Thescelosaurids are either considered to be basal ("primitive") ornithopod

Ornithopoda () is a clade of ornithischian dinosaurs, called ornithopods (). They represent one of the most successful groups of herbivorous dinosaurs during the Cretaceous. The most primitive members of the group were bipedal and relatively sm ...

s, or are placed outside of this group within the broader group Neornithischia

Neornithischia ("new ornithischians") is a clade of the dinosaur order Ornithischia. It is the sister group of the Thyreophora within the clade Genasauria. Neornithischians are united by having a thicker layer of asymmetrical enamel on the insi ...

.

Adult ''Thescelosaurus'' would have measured roughly long and probably weighed . It moved on two legs, and its body was counter-balanced by its long tail, which made up half of the body length and was stiffened by rod-like ossified tendons

A tendon or sinew is a tough band of dense fibrous connective tissue that connects muscle to bone. It sends the mechanical forces of muscle contraction to the skeletal system, while withstanding tension.

Tendons, like ligaments, are made of ...

. The animal had a long, low snout that ended in a toothless . It had more teeth than related genera, and the teeth were of different types. The hand bore five fingers, and the foot four toes. Thin plates are found next to the ribs' sides, the function of which is unclear. Scale impressions are known from the leg of one specimen. An herbivore, ''Thescelosaurus'' was likely a selective feeder, as indicated by its teeth and narrow snout. Its limbs were robust, and its (upper thigh bone) was longer than its (shin bone), suggesting that it was not adapted to running. Its brain was comparatively small, possibly indicating small group sizes of two to three individuals. The senses of smell and balance were acute, but hearing was poor. It might have been burrowing, as acute smell and poor hearing are typical for modern burrowing animals. Burrowing has been confirmed for the closely related '' Oryctodromeus'', and might have been widespread in thescelosaurids. The genus attracted media attention in 2000, when a specimen unearthed in 1999 was interpreted as including a fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

ized heart, but scientists now doubt the identification of the object.

''Thescelosaurus'' has been found across a wide geographic range across western North America. The first specimens were discovered in the Lance Formation

The Lance (Creek) Formation is a division of Late Cretaceous (dating to about 69–66 Ma) rocks in the western United States. Named after Lance Creek, Wyoming, the microvertebrate fossils and dinosaurs represent important components of the lates ...

of Wyoming

Wyoming ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States, Western United States. It borders Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho t ...

, but subsequent discoveries have been made in North Dakota

North Dakota ( ) is a U.S. state in the Upper Midwest, named after the indigenous Dakota people, Dakota and Sioux peoples. It is bordered by the Canadian provinces of Saskatchewan and Manitoba to the north and by the U.S. states of Minneso ...

, South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux language, Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state, state in the West North Central states, North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Dakota people, Dakota Sioux ...

, Montana

Montana ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota to the east, South Dakota to the southeast, Wyoming to the south, an ...

, Alberta

Alberta is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Canada. It is a part of Western Canada and is one of the three Canadian Prairies, prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to its west, Saskatchewan to its east, t ...

, and Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Western Canada. It is bordered on the west by Alberta, on the north by the Northwest Territories, on the east by Manitoba, to the northeast by Nunavut, and to the south by the ...

, in geological formations including the Frenchman Formation

The Frenchman Formation is a stratigraphic unit of Late Cretaceous (late Maastrichtian) Geochronology, age in the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin, Western Canada Sedimentary Basin. It is present in southern Saskatchewan and the Cypress Hills (C ...

, Hell Creek Formation

The Hell Creek Formation is an intensively studied division of mostly Upper Cretaceous and some lower Paleocene rocks in North America, named for exposures studied along Hell Creek, near Jordan, Montana. The Formation (stratigraphy), formation s ...

, and Scollard Formation

The Scollard Formation is an Upper Cretaceous to lower Palaeocene stratigraphic unit of the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin in southwestern Alberta. Its deposition spanned the time interval from latest Cretaceous to early Paleocene, and it inc ...

. It was relatively common, and may have been the most common dinosaur in the Frenchman Formation. Living during the late Maastrichtian

The Maastrichtian ( ) is, in the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS) geologic timescale, the latest age (geology), age (uppermost stage (stratigraphy), stage) of the Late Cretaceous epoch (geology), Epoch or Upper Cretaceous series (s ...

age, it was among the last of the non-avian dinosaurs before the entire group went extinct during the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event

The Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) extinction event, also known as the K–T extinction, was the extinction event, mass extinction of three-quarters of the plant and animal species on Earth approximately 66 million years ago. The event cau ...

around 66 million years ago.

Discovery and history

''T. neglectus'' and its type specimen

The first specimens of what would later be named ''Thescelosaurus'' were discovered during thebone wars

The Bone Wars, also known as the Great Dinosaur Rush, was a period of intense and ruthlessly competitive fossil hunting and discovery during the Gilded Age of American history, marked by a heated rivalry between Edward Drinker Cope (of the Aca ...

, a heated rivalry between the paleontologist

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure geolo ...

s Edward Drinker Cope

Edward Drinker Cope (July 28, 1840 – April 12, 1897) was an American zoologist, paleontology, paleontologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist, herpetology, herpetologist, and ichthyology, ichthyologist. Born to a wealthy Quaker fam ...

and Othniel Charles Marsh

Othniel Charles Marsh (October 29, 1831 – March 18, 1899) was an American professor of paleontology. A prolific fossil collector, Marsh was one of the preeminent paleontologists of the nineteenth century. Among his legacies are the discovery or ...

. In July 1891, the fossil hunter John Bell Hatcher, who had been hired by Marsh, and his assistant William H. Utterback discovered a near-complete skeleton of a small herbivorous dinosaur along Doegie Creek in Niobrara County, Wyoming

Wyoming ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States, Western United States. It borders Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho t ...

, in rocks of the Lance Formation

The Lance (Creek) Formation is a division of Late Cretaceous (dating to about 69–66 Ma) rocks in the western United States. Named after Lance Creek, Wyoming, the microvertebrate fossils and dinosaurs represent important components of the lates ...

. The skeleton was found lying on its left side and largely in natural , with only the head and neck lost to erosion. It was taken to the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums, Education center, education and Research institute, research centers, created by the Federal government of the United States, U.S. government "for the increase a ...

's National Museum of Natural History

The National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) is a natural history museum administered by the Smithsonian Institution, located on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., United States. It has free admission and is open 364 days a year. With 4.4 ...

(USNM), where it remained in its original, unlabelled packing box. In 1903, the USNM hired the paleontologist Charles W. Gilmore

Charles Whitney Gilmore (March 11, 1874 – September 27, 1945) was an American paleontologist who gained renown in the early 20th century for his work on vertebrate fossils during his career at the United States National Museum (now the N ...

to work on the extensive collection that had been amassed under the direction of Marsh, who had died in 1899. It was not before 1913 that Gilmore opened the box and, to his surprise, found the skeleton of a new species of dinosaur. In 1913, Gilmore published a preliminary description

Description is any type of communication that aims to make vivid a place, object, person, group, or other physical entity. It is one of four rhetorical modes (also known as ''modes of discourse''), along with exposition, argumentation, and narr ...

naming the new genus and species ''Thescelosaurus neglectus''. In addition to Hatcher's specimen (USNM 7757), which became the type specimen

In biology, a type is a particular wikt:en:specimen, specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally associated. In other words, a type is an example that serves to ancho ...

of the new species, Gilmore assigned a second, more fragmentary skeleton from Lance Creek, also in Niobrara County, to the species (paratype

In zoology and botany, a paratype is a specimen of an organism that helps define what the scientific name of a species and other taxon actually represents, but it is not the holotype (and in botany is also neither an isotype (biology), isotype ...

, USNM 7758). The generic name derives from the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

words ('), , and (') or . The specific name Specific name may refer to:

* in Database management systems, a system-assigned name that is unique within a particular database

In taxonomy, either of these two meanings, each with its own set of rules:

* Specific name (botany), the two-part (bino ...

, , is Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

for or , as the type specimen had been unattended to for so long.

Gilmore published a comprehensive description in 1915 after the type specimen was fully

Gilmore published a comprehensive description in 1915 after the type specimen was fully prepared

The Scout Motto of the Scout movement is, in English, "Be Prepared", with most international branches of the group using a close translation of that phrase. These mottoes have been used by millions of Scouts around the world since 1907. Most of t ...

. He identified six more specimens, including a shoulder blade with coracoid

A coracoid is a paired bone which is part of the shoulder assembly in all vertebrates except therian mammals (marsupials and placentals). In therian mammals (including humans), a coracoid process is present as part of the scapula, but this is n ...

, a neck vertebra, and a toe bone, as well as three partial skeletons that had been collected by Barnum Brown

Barnum Brown (February 12, 1873 – February 5, 1963), commonly referred to as Mr. Bones, was an American paleontologist. He discovered the first documented remains of ''Tyrannosaurus'' during a career that made him one of the most famous fossil ...

and were stored in the American Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) is a natural history museum on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. Located in Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 21 interconn ...

(AMNH). The neck and skull remained unknown, however, and Gilmore restored these missing parts based on ''Hypsilophodon

''Hypsilophodon'' (; meaning "high-crested tooth") is a neornithischian dinosaur genus from the Early Cretaceous period of England. It has traditionally been considered an early member of the group Ornithopoda, but recent research has put this ...

'', which he considered a close relative, in his skeletal and life reconstructions. For the museum display of the type specimen, Gilmore maintained its original posture and incompleteness. Only the right leg, which was slightly dislocated, was adjusted in position, and some minor damage to the bones was restored, but painted lighter than the original bones so that the real and reconstructed parts could be distinguished visually. In 1963, the display was included in a wall mount alongside the ornithischia

Ornithischia () is an extinct clade of mainly herbivorous dinosaurs characterized by a pelvic structure superficially similar to that of birds. The name ''Ornithischia'', or "bird-hipped", reflects this similarity and is derived from the Greek ...

ns ''Edmontosaurus

''Edmontosaurus'' ( ) (meaning "lizard from Edmonton"), with the second species often colloquially and historically known as ''Anatosaurus'' or ''Anatotitan'' (meaning "duck lizard" and "giant duck"), is a genus of hadrosaurid (duck-billed) din ...

'' and ''Corythosaurus

''Corythosaurus'' (; ) is a genus of hadrosaurid "duck-billed" dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous Period (geology), period, about 77–75.7 million years ago, in what is now Laramidia, western North America. Its name is derived from the Anci ...

'' and the theropod

Theropoda (; from ancient Greek , (''therion'') "wild beast"; , (''pous, podos'') "foot"">wiktionary:ποδός"> (''pous, podos'') "foot" is one of the three major groups (clades) of dinosaurs, alongside Ornithischia and Sauropodom ...

''Gorgosaurus

''Gorgosaurus'' ( ; ) is a genus of tyrannosaurid theropod dinosaur that lived in western North America during the Late Cretaceous Period (Campanian), between about 76.5 and 75 million years ago. Fossil remains have been found in the Ca ...

''. In 1981 the display was rearranged, placing ''Thescelosaurus'' higher and more out-of-sight. Renovations of the exhibit from 2014 to 2019 removed the ''Thescelosaurus'' and other dinosaurs on display, replacing them with plaster cast

A plaster cast is a copy made in plaster of another 3-dimensional form. The original from which the cast is taken may be a sculpture, building, a face, a pregnant belly, a fossil or other remains such as fresh or fossilised footprints – ...

s so that the original fossils could be further prepared and studied.

''T. edmontonensis'', revision, and ''T. garbanii''

In 1926, William Parks described the new species ''T. warreni'' from a well-preserved skeleton fromAlberta

Alberta is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Canada. It is a part of Western Canada and is one of the three Canadian Prairies, prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to its west, Saskatchewan to its east, t ...

, Canada, from what was then known as the Edmonton Formation

Within the earth science of geology, the Edmonton Group is a Late Cretaceous (Campanian stage) to early Paleocene stratigraphic unit of the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin in the central Alberta plains. It was first described as the Edmonton For ...

. This skeleton had notable differences from ''T. neglectus'', and so Charles M. Sternberg placed it in a new genus, ''Parksosaurus

''Parksosaurus'' (meaning "William Parks (paleontologist), William Parks's lizard") is a genus of neornithischian dinosaur from the Maastrichtian, early Maastrichtian-age Upper Cretaceous Horseshoe Canyon Formation of Alberta, Canada. It is based ...

'', in 1937. In 1940, Sternberg named an additional species, ''T. edmontonensis'', based on another articulated skeleton ( CMN 8537) that he had discovered in the Edmonton Formation of Rumsey, Alberta. Sternberg had already mentioned this specimen in 1926, though it was still unprepared at that time. It preserves most of the vertebral column

The spinal column, also known as the vertebral column, spine or backbone, is the core part of the axial skeleton in vertebrates. The vertebral column is the defining and eponymous characteristic of the vertebrate. The spinal column is a segmente ...

, pelvis, legs, scapula, coracoid, arm, and, most significantly, multiple bones of the skull roof

The skull roof or the roofing bones of the skull are a set of bones covering the brain, eyes and nostrils in bony fishes, including land-living vertebrates. The bones are derived from dermal bone and are part of the dermatocranium.

In com ...

and a complete mandible

In jawed vertebrates, the mandible (from the Latin ''mandibula'', 'for chewing'), lower jaw, or jawbone is a bone that makes up the lowerand typically more mobilecomponent of the mouth (the upper jaw being known as the maxilla).

The jawbone i ...

, the first known from ''Thescelosaurus''. Newer geology has separated the Edmonton Formation into four formations, with ''Parksosaurus'' from the older Horseshoe Canyon Formation

The Horseshoe Canyon Formation is a stratigraphic unit of the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin in southwestern Alberta. It takes its name from Horseshoe Canyon, an area of badlands near Drumheller.

The Horseshoe Canyon Formation is part of th ...

and ''Thescelosaurus edmontonensis'' from the younger Scollard Formation

The Scollard Formation is an Upper Cretaceous to lower Palaeocene stratigraphic unit of the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin in southwestern Alberta. Its deposition spanned the time interval from latest Cretaceous to early Paleocene, and it inc ...

.

In 1974, Peter M. Galton revised ''Thescelosaurus'' and described additional specimens, resulting in a total of 15 specimens known. These include four specimens from the Hell Creek Formation

The Hell Creek Formation is an intensively studied division of mostly Upper Cretaceous and some lower Paleocene rocks in North America, named for exposures studied along Hell Creek, near Jordan, Montana. The Formation (stratigraphy), formation s ...

collected by Barnum Brown in Montana

Montana ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota to the east, South Dakota to the southeast, Wyoming to the south, an ...

in 1906 and 1909, some of which had already been mentioned by Gilmore in 1915; one specimen found in 1892 by Wortman and Peterson at an uncertain location; two specimens found in 1921 by Levi Sternberg in the Frenchman Formation

The Frenchman Formation is a stratigraphic unit of Late Cretaceous (late Maastrichtian) Geochronology, age in the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin, Western Canada Sedimentary Basin. It is present in southern Saskatchewan and the Cypress Hills (C ...

of Rocky Creek, Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Western Canada. It is bordered on the west by Alberta, on the north by the Northwest Territories, on the east by Manitoba, to the northeast by Nunavut, and to the south by the ...

; and two isolated bones, also from Saskatchewan. One of Browns specimens, AMNH 5034, was found just below the Fort Union Formation

The Fort Union Formation is a geologic unit containing sandstones, shales, and coal beds in Wyoming, Montana, and parts of adjacent states. In the Powder River Basin, it contains important economic deposits of coal, uranium, and coalbed methane.

...

, at the youngest locality from which dinosaurs were found. Galton concluded that ''T. edmontonensis'' was simply a more robust individual of ''T. neglectus'' (possibly the opposite sex of the type individual).

William J. Morris described three additional partial skeletons in 1976, two found in the Hell Creek Formation of Garfield County, Montana

Garfield County is a county located in the U.S. state of Montana. As of the 2020 census, the population was 1,173. Its county seat is Jordan. Garfield County is noteworthy as the site of the discovery and excavation of four of the world's doz ...

by preparator Harli Garbani, and one from an unknown location in Harding County, South Dakota. The first specimen (LACM 33543) preserves parts of the vertebral column and pelvis in addition to bones of the skull not yet known from ''Thescelosaurus'' such as the jugal

The jugal is a skull bone found in most reptiles, amphibians and birds. In mammals, the jugal is often called the malar or zygomatic. It is connected to the quadratojugal and maxilla, as well as other bones, which may vary by species.

Anatomy ...

s and braincase

In human anatomy, the neurocranium, also known as the braincase, brainpan, brain-pan, or brainbox, is the upper and back part of the skull, which forms a protective case around the brain. In the human skull, the neurocranium includes the calv ...

. The second specimen (LACM 33542) includes vertebrae from the neck and back, and a nearly complete lower leg with a partial femur

The femur (; : femurs or femora ), or thigh bone is the only long bone, bone in the thigh — the region of the lower limb between the hip and the knee. In many quadrupeds, four-legged animals the femur is the upper bone of the hindleg.

The Femo ...

. Morris concluded that its ankle anatomy and larger size was unique, and therefore named the new species ''Thescelosaurus garbanii'', in honor of the discoverer Garbani. Morris also argued that the ankle of ''T. edmontonensis'', which Galton claimed was damaged and misinterpreted, was truly different from ''T. neglectus'' and more similar to ''T. garbanii''. Therefore, he suggested that ''T. edmontonensis'' and ''T. garbanii'' may eventually be separated from ''Thescelosaurus'' as a new genus. The third specimen (SDSM 7210) includes a large part of the skull, some partial vertebrae from the back and two bones of the fingers, parts that do not overlap with the diagnostic regions of the ''T. neglectus'' type specimen, preventing comparisons. Morris provisionally assigned the specimen to ''Thescelosaurus'', but suggested that it could represent a new species; this potential species has later been called the "Hell Creek hypsilophodontid".

''Bugenasaura'' and the "Willo" specimen

Galton revised ''Thescelosaurus'' for a second time in 1995. He argued that the supposedly diagnostic traits of the ankle of the ''T. edmontonensis'' specimen are the result of breakage, as indicated by the previously undescribed left ankle of that specimen that showed the same anatomy as ''T. neglectus''. Consequently, he synonymized ''T. edmontonensis'' with ''T. neglectus''. Galton determined that Morris correctly interpreted the ankle of ''T. garbanii'' and suggested that the species could be elevated to a genus of its own. There was also the possibility that the hindlimb of ''T. garbanii'' did instead belong to the pachycephalosaurid ''Stygimoloch

''Pachycephalosaurus'' (; meaning "thick-headed lizard", from Greek ''pachys-/'' "thickness", ''kephalon/'' "head" and ''sauros/'' "lizard") is a genus of pachycephalosaurid ornithischian dinosaur. The type species, ''P. wyomingensis'', i ...

'', which is also known from the Hell Creek Formation and for which the hindlimb was unknown. Galton also concluded that the skull of SDSM 7210, the third of the specimens described by Morris, was distinct from ''Thescelosaurus'', and therefore named the new taxon ''Bugenasaura infernalis''. The name is a combination of the Latin , and , , as well as the Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

, . The specific name, from the Latin , , is a reference to the lower levels of the Hell Creek Formation from which it is known. Galton also tentatively assigned LACM 33543, the type of ''T. garbanii'', to the new species, noting that additional material is necessary to determine if the referral is correct, and that the name ''garbanii'' should have priority if this turns out to be the case.

In his 1995 revision, Galton also reassigned isolated teeth from the

In his 1995 revision, Galton also reassigned isolated teeth from the Campanian

The Campanian is the fifth of six ages of the Late Cretaceous epoch on the geologic timescale of the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS). In chronostratigraphy, it is the fifth of six stages in the Upper Cretaceous Series. Campa ...

Judith River Formation

The Judith River Formation is a fossil-bearing geologic formation in Montana, and is part of the Montana Group. It dates to the Late Cretaceous, between 79 and 75.3 million years ago, corresponding to the "Judithian" land vertebrate age. It was ...

of Montana to the related genus '' Orodromeus''. These teeth had been assigned to ''Thescelosaurus'' cf. ''neglectus'' by Ashok Sahni in 1972, which would have been the oldest occurrence of ''Thescelosaurus''. In a 1999 study on the anatomy of ''Bugenasaura'', Galton assigned a tooth in the collection of the University of California Museum of Paleontology

The University of California Museum of Paleontology (UCMP) is a paleontology museum located on the campus of the University of California, Berkeley.

The museum is within the Valley Life Sciences Building (VLSB), designed by George W. Kelham ...

(UCMP 49611) to the latter. Significantly, this tooth reportedly came from the Late Jurassic

The Late Jurassic is the third Epoch (geology), epoch of the Jurassic Period, and it spans the geologic time scale, geologic time from 161.5 ± 1.0 to 143.1 ± 0.8 million years ago (Ma), which is preserved in Upper Jurassic stratum, strata.Owen ...

Kimmeridge Clay Formation

The Kimmeridge Clay is a sedimentary rock, sedimentary deposit of fossiliferous marine clay which is of Late Jurassic to lowermost Cretaceous age and occurs in southern and eastern England and in the North Sea. This rock formation (geology), form ...

of Weymouth, England

Weymouth ( ) is a seaside town and civil parish in the Dorset district, in the ceremonial county of Dorset, England. Situated on a sheltered bay at the mouth of the River Wey, south of the county town of Dorchester, Weymouth had a populatio ...

, and therefore is roughly 70 million years older than the ''Bugenasaura'' type specimen and from another continent. Galton argued that it had possibly been mislabelled and was actually from the Lance Formation of Wyoming, but the tooth was first collected before the museum was active in the Lance region. The lack of diagnostic features led Paul M. Barrett and Susannah Maidment

Susannah "Susie" Catherine Rose Maidment is a British palaeontologist at the Natural History Museum, London. She is also an honorary Professor at the University of Birmingham. She is internationally recognised for her research on ornithischian din ...

to classify the tooth as an indeterminate ornithischian in 2011.

After the discovery of additional specimens of ''Thescelosaurus'' preserving both the skull and skeleton, Clint Boyd and colleagues reassessed the historic and current species of ''Thescelosaurus'' in 2009. One of the new specimens ( MOR 979) was found in the Hell Creek of Montana and preserves a nearly complete skull and skeleton. The researchers also identified previously overlooked skull material of the ''T. neglectus'' paratype USNM 7758, which allowed comparisons of the diagnostic regions of the skull and ankle across multiple specimens and species. The key specimen, however, was NCSM 15728, nicknamed "Willo", which was found in the upper Hell Creek Formation in Harding County, South Dakota by Michael Hammer in 1999. This specimen preserves most of the skeleton and a mass in the chest cavity that was initially interpreted as a heart. "Willo" also includes a complete skull, showing that it was much lower and longer than previously thought. "Willo" and the other new specimens made it clear that ''Bugenasaura infernalis'' must be assigned to ''Thescelosaurus''. By reassigning the species, Boyd and colleagues created the new combination ''T. infernalis'' which they considered undiagnostic.

After the discovery of additional specimens of ''Thescelosaurus'' preserving both the skull and skeleton, Clint Boyd and colleagues reassessed the historic and current species of ''Thescelosaurus'' in 2009. One of the new specimens ( MOR 979) was found in the Hell Creek of Montana and preserves a nearly complete skull and skeleton. The researchers also identified previously overlooked skull material of the ''T. neglectus'' paratype USNM 7758, which allowed comparisons of the diagnostic regions of the skull and ankle across multiple specimens and species. The key specimen, however, was NCSM 15728, nicknamed "Willo", which was found in the upper Hell Creek Formation in Harding County, South Dakota by Michael Hammer in 1999. This specimen preserves most of the skeleton and a mass in the chest cavity that was initially interpreted as a heart. "Willo" also includes a complete skull, showing that it was much lower and longer than previously thought. "Willo" and the other new specimens made it clear that ''Bugenasaura infernalis'' must be assigned to ''Thescelosaurus''. By reassigning the species, Boyd and colleagues created the new combination ''T. infernalis'' which they considered undiagnostic.

''T. assiniboiensis'' and further discoveries

Another species, ''T. assiniboiensis'', was named by Caleb M. Brown and colleagues in 2011 based on a specimen ( RSM P 1225.1) found in 1968 by Albert Swanston, a museum technician at theRoyal Saskatchewan Museum

The Royal Saskatchewan Museum (RSM) is a Canadian natural history museum in Regina, Saskatchewan. Founded in 1906, it is the first museum in Saskatchewan and the first Provincial and territorial museums of Canada, provincial museum among the thr ...

. The specific name, ''assiniboiensis'', derives from the historic District of Assiniboia

Assiniboia District refers to two historical Districts of the Northwest Territories, districts of Canada's Northwest Territories. The name is taken from the Assiniboine people, Assiniboine First Nation.

Historical usage

''For more information on ...

that covered the southern Saskatchewan region where the Frenchman Formation is exposed, which in turn takes its name from the Assiniboine

The Assiniboine or Assiniboin people ( when singular, Assiniboines / Assiniboins when plural; Ojibwe: ''Asiniibwaan'', "stone Sioux"; also in plural Assiniboine or Assiniboin), also known as the Hohe and known by the endonym Nakota (or Nakoda ...

peoples. When discovered, the specimen was articulated, with its tail weathering out of a hill side. It is a small specimen including a fragmentary skull, most of the vertebral column, the pelvic girdles and the hind limbs. The locality of the specimen as originally reported was incorrect, as revisiting of the Frenchman River

The Frenchman River, (), also known locally as the Whitemud River, is a river in Saskatchewan, Canada and Montana, United States. It is a tributary of the Milk River, itself a tributary of the Missouri and, in turn, part of the Mississippi Riv ...

valley by Tim Tokaryk in the 1980s found that the excavation, identifiable by bone and plaster remnants, actually took place on the north side of the valley, approximately halfway up the exposed claystone

Mudrocks are a class of fine-grained siliciclastic sedimentary rocks. The varying types of mudrocks include siltstone, claystone, mudstone and shale. Most of the particles of which the stone is composed are less than and are too small to ...

. This places the specimen in the Frenchman Formation.

Specimens can only be directly compared if they preserve the same bones, but overlapping material is often not available – the assignment of most ''Thescelosaurus'' specimens to any of the three recognized species therefore remained uncertain. This situation improved in 2014, when Boyd and colleagues reported a new specimen from the Hell Creek Formation of Dewey County, South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux language, Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state, state in the West North Central states, North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Dakota people, Dakota Sioux ...

(TLAM.BA.2014.027.0001), that was collected from private lands by Bill Alley before being donated to the Timber Lake and Area Museum. This specimen had yet to be fully prepared but includes a mostly complete but slightly crushed skull and much of the skeleton. This find allowed the assignment of this specimen and the "Willo" specimen to ''T. neglectus''. In 2022, news media reported that a specimen of ''Thescelosaurus'' was found at the Tanis fossil site in North Dakota, which is thought to show direct signs of the Chicxulub asteroid impact in the Gulf of Mexico that resulted in the K-Pg extinction.

Description

sexually dimorphic

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where sexes of the same species exhibit different Morphology (biology), morphological characteristics, including characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most dioecy, di ...

, with one sex

Sex is the biological trait that determines whether a sexually reproducing organism produces male or female gametes. During sexual reproduction, a male and a female gamete fuse to form a zygote, which develops into an offspring that inheri ...

larger than the other.

Skull

The skull is best known from ''T. neglectus'', mostly thanks to the excellently preserved "Willo" specimen which has been CT-scanned to reveal its internal details. A fragmentary skull is also known from ''T. assiniboiensis'' (RSM P 1225.1). Mostautapomorphies

In phylogenetics, an autapomorphy is a distinctive feature, known as a derived trait, that is unique to a given taxon. That is, it is found only in one taxon, but not found in any others or outgroup taxa, not even those most closely related to ...

– distinguishing features that are not found in related genera – are found in the skull. The skull also shows many plesiomorphies

In phylogenetics, a plesiomorphy ("near form") and symplesiomorphy are synonyms for an ancestral character shared by all members of a clade, which does not distinguish the clade from other clades.

Plesiomorphy, symplesiomorphy, apomorphy, an ...

, "primitive" ( basal) features that are typically found in ornithischians that are geologically much older, but also shows derived (advanced) features.

The skull had a long, low snout that ended in a toothless . As in other dinosaurs, it was perforated by several , or skull openings. Of these, the (eye socket) and the (behind the orbit) were proportionally large, while the (nostril) was small. The external naris was formed by the (the front bone of the upper jaw) and the , while the (the tooth-bearing "cheek" bone) was excluded. Another fenestra, the antorbital fenestra

An antorbital fenestra (plural: fenestrae) is an opening in the skull that is in front of the eye sockets. This skull character is largely associated with Archosauriformes, archosauriforms, first appearing during the Triassic Period. Among Extant ...

, was in-between the external naris and the orbit and contained two smaller internal fenestrae. Long rod-like bones called palpebrals were present above the eyes, giving the animal heavy bony eyebrows. The palpebral was not aligned with the upper margin of the orbit as in some other ornithischians, but protruded across it. The , which form the above the orbit, were widest at the level of the middle of the orbit and narrower at their posterior (rear) ends – an autapomorphy of ''Thescelosaurus''.

There was a prominent ridge along the length of both maxillae; a similar ridge was also present on both (the tooth-bearing bone of the lower jaw). The ridges and position of the teeth, deeply internal to the outside surface of the skull, have been interpreted as evidence for muscular cheeks. The morphology of the ridge on the maxilla, which is very pronounced and has small and oblique ridges covering its posterior end, is an autapomorphy of the genus. The teeth were of different types: small pointed premaxillary teeth, and leaf-shaped cheek teeth that differed between the maxilla and the dentary. The premaxillae had six teeth each, a primitive trait among ornithischians that is otherwise only found in much earlier and more basal forms such as ''Lesothosaurus

''Lesothosaurus'' is a Monotypic taxon, monospecific genus of ornithischian dinosaur that lived during the Early Jurassic in what is now South Africa and Lesotho. It was named by paleontologist Peter Galton in 1978, the name meaning "lizard from L ...

'' and ''Scutellosaurus

''Scutellosaurus'' ( ) is a genus of basal thyreophoran dinosaur that lived approximately 196 million years ago during the early part of the Jurassic Period in what is now Arizona, USA. It is classified in Thyreophora, the armoured dinosaurs; ...

''. Immature individuals may have had less than six premaxillary teeth. Unlike many other basal ornithischians, the premaxillary teeth lacked (small protuberances on the cutting edges). Both the maxilla and the dentary had up to twenty cheek teeth on each side, which is again similar to basal ornithischians and unlike other neornithischia

Neornithischia ("new ornithischians") is a clade of the dinosaur order Ornithischia. It is the sister group of the Thyreophora within the clade Genasauria. Neornithischians are united by having a thicker layer of asymmetrical enamel on the insi ...

ns, which had a reduced tooth count. The cheek teeth themselves likewise showed primitive features, such as a constriction that separated the crowns from their roots

A root is the part of a plant, generally underground, that anchors the plant body, and absorbs and stores water and nutrients.

Root or roots may also refer to:

Art, entertainment, and media

* ''The Root'' (magazine), an online magazine focusin ...

, and a (bulge surrounding the tooth) above the constriction. The front bone of the lower jaw was the , which was unique to ornithischians. When seen from below, the posterior end of the predentary was bifurcated, which is a derived feature.

Boyd and colleagues, in 2014, listed seven skull features that separate ''T. assiniboiensis'' from ''T. neglectus'', most of which are found in the at the back of the skull. These include, amongst others, a (small opening) piercing the roof of the braincase (absent in ''T. neglectus''); the flattened anterior

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to describe unambiguously the anatomy of humans and other animals. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position pro ...

(front) surface of the bone (V-shaped in ''T. neglectus''); and the trigeminal foramen (the opening for the trigeminal nerve

In neuroanatomy, the trigeminal nerve (literal translation, lit. ''triplet'' nerve), also known as the fifth cranial nerve, cranial nerve V, or simply CN V, is a cranial nerve responsible for Sense, sensation in the face and motor functions ...

) piercing both the and bones (restricted to the prootic in ''T. neglectus'').

Vertebrae and limbs

''T. neglectus'' had 6 ("hip") vertebrae and 27 presacral ("neck and back") vertebrae. The type specimen of ''T. assiniboiensis'' appears to have had only five sacrals, but it is possible that this individual was not yet fully mature and that the last sacral was not yet fused to the other sacrals. The tail was long and made up half of the total body length. It was braced byossified

Ossification (also called osteogenesis or bone mineralization) in bone remodeling is the process of laying down new bone material by cells named osteoblasts. It is synonymous with bone tissue formation. There are two processes resulting in t ...

tendon

A tendon or sinew is a tough band of fibrous connective tissue, dense fibrous connective tissue that connects skeletal muscle, muscle to bone. It sends the mechanical forces of muscle contraction to the skeletal system, while withstanding tensi ...

s from the middle to the tip, which would have reduced the flexibility of the tail. The rib cage was broad, giving it a wide back. Large thin and flat mineralized plates have been found next to the ribs' sides, so-called intercostal plates. The anterior ribs were flattened and concave, and the posterior margins of their lower ends had a rough surface. These features are autapomorphies of ''Thescelosaurus'' and are possibly adaptations that allow the plates to attach to the rib cage.

The limbs were robust. The (upper thigh bone) was longer than the (shin bone), which distinguishes the genus from closely related genera. ''Thescelosaurus'' had short, broad, five-fingered hands. The second digit was the longest, and the fifth digit was strongly reduced in size. Only the first three digits ended in hooflike ungual

An ungual (from Latin ''unguis'', i.e. ''nail'') is a highly modified distal toe bone which ends in a hoof, claw, or nail. Elephants and ungulates have ungual phalanges, as did the sauropod

Sauropoda (), whose members are known as sauropods (; ...

s. There were two phalanges

The phalanges (: phalanx ) are digit (anatomy), digital bones in the hands and foot, feet of most vertebrates. In primates, the Thumb, thumbs and Hallux, big toes have two phalanges while the other Digit (anatomy), digits have three phalanges. ...

(finger bones) in the first digit, three in the second, four in the third, three in the fourth, and two in the fifth. The foot had five , though only the first four carried digits, with the fifth metatarsal being vestigial

Vestigiality is the retention, during the process of evolution, of genetically determined structures or attributes that have lost some or all of the ancestral function in a given species. Assessment of the vestigiality must generally rely on co ...

(reduced to a small splint). The first metatarsal was only half the length of the third, and its digit might not have regularly touched the ground. Most of the animal's weight was therefore supported by the center three , of which the middle (third) was the longest. The first digit had two phalanges, the second had three, the third had four, and the fourth had five. The digits were shorter than the metatarsals, and their phalanges were distinctly flattened. The species ''T. garbanii'' differs from the other species in its unique ankle, with the calcaneus

In humans and many other primates, the calcaneus (; from the Latin ''calcaneus'' or ''calcaneum'', meaning heel; : calcanei or calcanea) or heel bone is a bone of the Tarsus (skeleton), tarsus of the foot which constitutes the heel. In some other ...

being reduced and not contributing to the midtarsal joint.

Integument

For most of its history, the nature of this genus'

For most of its history, the nature of this genus' integument

In biology, an integument is the tissue surrounding an organism's body or an organ within, such as skin, a husk, Exoskeleton, shell, germ or Peel (fruit), rind.

Etymology

The term is derived from ''integumentum'', which is Latin for "a coverin ...

, be it scales or something else, remained unknown. Gilmore described patches of carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalence, tetravalent—meaning that its atoms are able to form up to four covalent bonds due to its valence shell exhibiting 4 ...

ized material near the shoulders as possible epidermis

The epidermis is the outermost of the three layers that comprise the skin, the inner layers being the dermis and Subcutaneous tissue, hypodermis. The epidermal layer provides a barrier to infection from environmental pathogens and regulates the ...

, with a "punctured" texture, but no regular pattern, while Morris suggested that armor

Armour (Commonwealth English) or armor (American English; see American and British English spelling differences#-our, -or, spelling differences) is a covering used to protect an object, individual, or vehicle from physical injury or damage, e ...

was present, in the form of small scute

A scute () or scutum (Latin: ''scutum''; plural: ''scuta'' "Scutum (shield), shield") is a bony external plate or scale overlaid with horn, as on the shell of a turtle, the skin of crocodilians, and the feet of Bird anatomy#Scales, birds. The ter ...

s he interpreted as located at least along the midline of the neck of one specimen. Scutes have not been found with other articulated specimens of ''Thescelosaurus'', though, and Galton argued in 2008 that Morris's scutes are crocodilia

Crocodilia () is an order of semiaquatic, predatory reptiles that are known as crocodilians. They first appeared during the Late Cretaceous and are the closest living relatives of birds. Crocodilians are a type of crocodylomorph pseudosuchia ...

n in origin. In 2022, news media reported that the Tanis specimen preserves skin impressions on a leg that show that parts of the animal were covered in scales.

Classification

In his 1913 description of ''Thescelosaurus'', Gilmore considered it to be a member of Camptosauridae, alongside ''Hypsilophodon'', ''Dryosaurus

''Dryosaurus'' ( , meaning 'tree lizard', Greek ' () meaning 'tree, oak' and () meaning 'lizard', (the name reflects the forested habitat, not a vague oak-leaf shape of its cheek teeth as is sometimes assumed) is a genus of an ornithopod dinos ...

'' and ''Laosaurus

''Laosaurus'' (meaning "stone or fossil lizard") is a genus of neornithischian dinosaur. The type species, ''Laosaurus celer'', was first described by O.C. Marsh in 1878 from remains from the Oxfordian-Tithonian-age Upper Jurassic Morrison Form ...

''. In 1915, he instead placed it within Hypsilophodontidae

Hypsilophodontidae (or Hypsilophodontia) is a traditionally used family (biology), family of ornithopod dinosaurs, generally considered invalid today. It historically included many small bodied bipedal neornithischian taxa from around the world, ...

alongside only ''Hypsilophodon''. Many authors followed this classification within Hypsilophodontidae. Franz Nopcsa Franz may refer to:

People

* Franz (given name)

* Franz (surname)

Places

* Franz (crater), a lunar crater

* Franz, Ontario, a railway junction and unorganized town in Canada

* Franz Lake, in the state of Washington, United States – see Fran ...

and Friedrich von Huene

Baron Friedrich Richard von Hoyningen-Huene (22 March 1875 – 4 April 1969) was a German nobleman paleontologist who described a large number of dinosaurs, more than anyone else in 20th-century Europe. He studied a range of Permo-Carbonife ...

instead retained ''Thescelosaurus'' as a relative of ''Camptosaurus'' in 1928 and 1956, respectively. In 1937, Sternberg separated ''Thescelosaurus'' and the related ''Parksosaurus'' into a family of their own, the Thescelosauridae

Thescelosauridae is a clade of neornithischians from the Cretaceous of East Asia and North America. The group was originally used as a name by Charles M. Sternberg in 1937, but was not formally defined until 2013, where it was used by Brown and ...

, but considered both genera to be members of the subfamily Thescelosaurinae within Hypsilophodontidae in 1940. Anatoly Konstantinovich Rozhdestvensky Anatoly Konstantinovich Rozhdestvensky (, 1920–1983) was a Soviet paleontologist responsible for naming many dinosaurs, including '' Aralosaurus'' and '' Probactrosaurus''.

References

Soviet paleontologists

1920 births

1983 deaths

Russi ...

and Richard A. Thulborn retained Thescelosauridae as a separate family in 1964 and 1974, respectively. Galton classified ''Thescelosaurus'' as a member of Iguanodontidae

Iguanodontidae is a family of iguanodontians belonging to Styracosterna, a derived clade within Ankylopollexia. The clade is formally defined in the ''PhyloCode'' by Daniel Madzia and colleagues in 2021 as "the largest clade containing '' Igua ...

based on hindlimb proportions in 1974, but this family was found to be polyphyletic

A polyphyletic group is an assemblage that includes organisms with mixed evolutionary origin but does not include their most recent common ancestor. The term is often applied to groups that share similar features known as Homoplasy, homoplasies ...

(not a natural group); he therefore returned to a hypsilophodontid classification in 1995.

Hypsilophodontidae only included four genera in 1940: ''Hypsilophodon'', ''Thescelosaurus'', ''Parksosaurus'', and ''Dysalotosaurus''. In 1966,Alfred Sherwood Romer

Alfred Sherwood Romer (December 28, 1894 – November 5, 1973) was an American paleontologist and biologist and a specialist in vertebrate evolution.

Biography

Alfred Romer was born in White Plains, New York, the son of Harry Houston Romer an ...

assigned most small ornithopods

Ornithopoda () is a clade of ornithischian dinosaurs, called ornithopods (). They represent one of the most successful groups of herbivore, herbivorous dinosaurs during the Cretaceous. The most primitive members of the group were bipedal and rel ...

to the family, which was followed by Galton and later authors, though ''Thescelosaurus'' was not always included in the family. As a result, Hypsilophodontidae included 13 genera in the first edition of the book The Dinosauria

''The Dinosauria'' is an encyclopedia on dinosaurs, edited by paleontologists David B. Weishampel, Peter Dodson, and Halszka Osmólska. It has been published in two editions by the University of California Press, with the first edition in 1990 ...

in 1990. This concept of Hypsilophodontidae as an inclusive monophyletic

In biological cladistics for the classification of organisms, monophyly is the condition of a taxonomic grouping being a clade – that is, a grouping of organisms which meets these criteria:

# the grouping contains its own most recent co ...

(natural) group was supported by the early cladistic

Cladistics ( ; from Ancient Greek 'branch') is an approach to biological classification in which organisms are categorized in groups ("clades") based on hypotheses of most recent common ancestry. The evidence for hypothesized relationships is ...

studies of Paul C. Sereno, David B. Weishampel

Professor David Bruce Weishampel (born November 16, 1952) is an American palaeontologist in the Center for Functional Anatomy and Evolution at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Weishampel received his Ph.D. in Geology from the Univer ...

, and Ronald Heinrich, who found ''Thescelosaurus'' to be the most basal hypsilophodontid. The analysis of Weishampel and Heinrich in 1992 can be seen below.

Gasparinisaura

''Gasparinisaura'' (meaning "Gasparini's lizard") is a genus of herbivorous ornithopod dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous. The first fossils of ''Gasparinisaura'' were found in 1992 near Cinco Saltos in Río Negro Province, Argentina. The type spe ...

''. However, Boyd argued that the anatomy of ''Parksosaurus'' had been misinterpreted, and that ''Parksosaurus'' and ''Thescelosaurus'' were very closely related if not each other's closest relatives. The clades Thescelosauridae (or, alternatively, Parksosauridae) and Thescelosaurinae have been confirmed by numerous phylogenetic analyses, though not by all. There is also disagreement about whether ''Thescelosaurus'' and thescelosaurids are members of Ornithopoda or more basal. Boyd highlighted in 2015 that many phylogenetic studies that included ''Thescelosaurus'' either do not include marginocephalians or are unresolved, so there was no definitive evidence that ''Thescelosaurus'' was an ornithopod. In his analysis, ''Thescelosaurus'' and Thescelosauridae were outside Ornithopoda, instead forming an expansive clade of non-ornithopod neornithischians. Some studies agree with this placement for thescelosaurids, while others support ''Thescelosaurus'' as an ornithopod, and others are unresolved. Fonseca and colleagues gave the name Pyrodontia to the clade uniting ''Thescelosaurus'' with more derived ornithischians when Thescelosauridae is outside Ornithopoda, referencing the early and rapid diversification of Thescelosauridae, Marginocephalia and Ornithopoda. The thescelosaurid results of Fonseca and colleagues in 2024 can be seen below.

The earliest-known thescelosaurids, ''Changchunsaurus'' and ''Zephyrosaurus'', are from the middle Cretaceous, roughly 40 million years younger than when the group would have evolved, suggesting a long ghost lineage

A ghost lineage is a hypothesized ancestor in a species lineage that has left no fossil evidence, but can still be inferred to exist or have existed because of gaps in the fossil record or genomic evidence. The process of determining a ghost line ...

(a period of geologic time during which a group existed but left no fossil evidence). In 2024, André Fonseca and colleagues recovered the Late Jurassic ''Nanosaurus

''Nanosaurus'' ("small or dwarf lizard") is an extinct genus of neornithischian dinosaur that lived about 155 to 148 million years ago, during the Late Jurassic in North America. Its fossils are known from the Morrison Formation of the south-we ...

'' as the earliest thescelosaurid, which would shorten the ghost lineage. Boyd concluded in 2015 that the split between Orodrominae and Thescelosaurinae took place in North America by the Aptian

The Aptian is an age (geology), age in the geologic timescale or a stage (stratigraphy), stage in the stratigraphic column. It is a subdivision of the Early Cretaceous, Early or Lower Cretaceous epoch (geology), Epoch or series (stratigraphy), S ...

stage, with Orodrominae diversifying within North America. Thescelosaurinae might have diversified either in North America or Asia; the genus '' Fona'', described in 2024, suggests that Thescelosaurinae was already established in North America at the beginning of the Late Cretaceous

The Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma) is the more recent of two epochs into which the Cretaceous Period is divided in the geologic time scale. Rock strata from this epoch form the Upper Cretaceous Series. The Cretaceous is named after ''cre ...

.

Paleobiology

Like other ornithischians, ''Thescelosaurus'' was probably herbivorous. The different types of teeth, as well as the narrow snout, suggest that it was a selective feeder. The contemporary pachycephalosaur ''

Like other ornithischians, ''Thescelosaurus'' was probably herbivorous. The different types of teeth, as well as the narrow snout, suggest that it was a selective feeder. The contemporary pachycephalosaur ''Stegoceras

''Stegoceras'' is a genus of Pachycephalosauria, pachycephalosaurid (dome-headed) dinosaur that lived in what is now North America during the Late Cretaceous Period (geology), period, about 77.5 to 74 million years ago (mya). The first specim ...

'', in contrast, was probably a more indiscriminate feeder, allowing both animals to share the same environment without competing for food (niche partitioning

In ecology, a niche is the match of a species to a specific environmental condition.

Three variants of ecological niche are described by

It describes how an organism or population responds to the distribution of resources and competitors (for e ...

). One specimen is known to have had a bone pathology

Pathology is the study of disease. The word ''pathology'' also refers to the study of disease in general, incorporating a wide range of biology research fields and medical practices. However, when used in the context of modern medical treatme ...

, with the long bones

The long bones are those that are longer than they are wide. They are one of five types of bones: long, short, flat, irregular and sesamoid. Long bones, especially the femur and tibia, are subjected to most of the load during daily activities a ...

of the right foot fused at their tops.

Posture and locomotion

In his 1915 description, Gilmore suggested that ''Thescelosaurus'' was an agile,biped

Bipedalism is a form of terrestrial locomotion where an animal moves by means of its two rear (or lower) limbs or legs. An animal or machine that usually moves in a bipedal manner is known as a biped , meaning 'two feet' (from Latin ''bis'' ' ...

al (two-legged) animal and was adapted for running. He also created a model to depict its life appearance, showing a light and agile body built with slender hind limbs. These ideas were contested by Sternberg in 1940, who argued that the skeleton, and especially the limbs, were robust. His own model, of the species ''T. edmontonensis'', consequently showed limbs that were much more muscular. Other subsequent studies disagreed with Gilmore idea of a proficient runner given the robust skeleton, the proportionally long femur, and the short lower leg bones. Galton, in 1974, even suggested that ''Thescelosaurus'' could have occasionally moved quadruped

Quadrupedalism is a form of locomotion in which animals have four legs that are used to bear weight and move around. An animal or machine that usually maintains a four-legged posture and moves using all four legs is said to be a quadruped (fr ...

ally (on all fours), given its fairly long arms and wide hands. Phil Senter and Jared Mackey, in 2024, concluded that a quadrupedal posture would have been theoretically possible, as the spine of the back was bent down, allowing the hand to touch the ground even when the hind limbs were straight. However, in such a posture the fingers would have pointed towards the sides rather than front, and consequently could not have been used to propel the animal forward; quadrupedal locomotion therefore seems unlikely.

A 2023 study by David Button and Lindsay Zanno concluded that ''Thescelosaurus'' was less adapted for running than other thescelosaurids but nonetheless showed two traits that are common in runners. The first of these is the

A 2023 study by David Button and Lindsay Zanno concluded that ''Thescelosaurus'' was less adapted for running than other thescelosaurids but nonetheless showed two traits that are common in runners. The first of these is the fourth trochanter

The fourth trochanter is a shared characteristic common to archosaurs. It is a protrusion on the posterior-medial side of the middle of the femur shaft that serves as a muscle attachment, mainly for the '' musculus caudofemoralis longus'', the m ...

, a bony crest on the femur that anchored the main locomotory muscle. This crest was relatively proximal (closer to the upper end of the bone), allowing for faster movements at the expense of power. The second trait is found in the inner ear

The inner ear (internal ear, auris interna) is the innermost part of the vertebrate ear. In vertebrates, the inner ear is mainly responsible for sound detection and balance. In mammals, it consists of the bony labyrinth, a hollow cavity in the ...

, which contains the three semicircular canal

The semicircular canals are three semicircular interconnected tubes located in the innermost part of each ear, the inner ear. The three canals are the lateral, anterior and posterior semicircular canals. They are the part of the bony labyrinth, ...

s that house the sense of balance

The sense of balance or equilibrioception is the perception of balance (ability), balance and Orientation (geometry), spatial orientation. It helps prevent humans and nonhuman animals from falling over when standing or moving. Equilibrioception ...

: one of these canals, the anterior semicircular canal, was greatly enlarged, suggesting acute balance sensitivity, which in turn might suggest high agility but could also be explained by possible burrowing behavior.

In Sternberg's 1940 model, the upper arm was horizontal and almost perpendicular to the body. Peter Galton

Peter Malcolm Galton (born 14 March 1942 in London) is a British vertebrate paleontologist who has to date written or co-written about 190 papers in scientific journals or chapters in paleontology textbooks, especially on ornithischian and prosau ...

pointed out in 1970 that the (upper arm bone) of most ornithischians was articulated to the shoulder by an articular surface consisting of the entire end of the bone, rather than a distinct ball and socket as in mammals, and that the humerus would not have spread sidewards as in Sternberg's model. Senter and Mackey found that the humerus could swing forward to a vertical position, but not much beyond that point.

The semicircular canals may allow for reconstructing the habitual posture of the head. In modern animals, one of the canals, the lateral semicircular canal, is typically horizontal when the head is in an "alert" posture. Button and Zanno argued that the head of ''Thescelosaurus'' would be slightly up-tilted when oriented such that the canal is horizontal. This is similar to ''Dysalotosaurus'', but contrasts with the down-tilted alert postures hypothesized for many other ornithischians including ceratopsia

Ceratopsia or Ceratopia ( or ; Ancient Greek, Greek: "horned faces") is a group of herbivore, herbivorous, beaked dinosaurs that thrived in what are now North America, Asia and Europe, during the Cretaceous Period (geology), Period, although ance ...

ns, ankylosaur

Ankylosauria is a group of herbivorous dinosaurs of the clade Ornithischia. It includes the great majority of dinosaurs with armor in the form of bony osteoderms, similar to turtles. Ankylosaurs were bulky quadrupeds, with short, powerful l ...

s, and hadrosaur

Hadrosaurids (), also hadrosaurs or duck-billed dinosaurs, are members of the ornithischian family Hadrosauridae. This group is known as the duck-billed dinosaurs for the flat duck-bill appearance of the bones in their snouts. The ornithopod fami ...

s.

Function of intercostal plates

The function of the plates at the side of the rib cage remains unclear. Such plates are known from several other ornithischians, and it was originally suggested that they wereosteoderm

Osteoderms are bony deposits forming scales, plates, or other structures based in the dermis. Osteoderms are found in many groups of extant and extinct reptiles and amphibians, including lizards, crocodilians, frogs, temnospondyls (extinct amph ...

s (armor) for defence against predators. This hypothesis has been refuted, as both their outer and inner surfaces show Sharpey's fibres

Sharpey's fibres (bone fibres, or perforating fibres) are a matrix of connective tissue consisting of bundles of strong predominantly type I collagen fibres connecting periosteum to bone. They are part of the outer fibrous layer of periosteum ...

, indicating the insertion of tendons – consequently, the plates must have been completely embedded within the musculature. Furthermore, analysis of thin sections of the plates of ''Thescelosaurus'', ''Hypsilophodon'', and ''Talenkauen

''Talenkauen'' is a genus of Basal (phylogenetics), basal iguanodont dinosaur from the Campanian or Maastrichtian age of the Late Cretaceous Cerro Fortaleza Formation, formerly known as the Pari Aike Formation of Patagonian Lake Viedma, in the Ma ...

'' showed that the plates started as cartilage

Cartilage is a resilient and smooth type of connective tissue. Semi-transparent and non-porous, it is usually covered by a tough and fibrous membrane called perichondrium. In tetrapods, it covers and protects the ends of long bones at the joints ...

and became bone as the animal aged (endochondral ossification

Endochondral ossification is one of the two essential pathways by which bone tissue is produced during fetal development and bone healing, bone repair of the mammalian skeleton, skeletal system, the other pathway being intramembranous ossificatio ...

), which is not the case with osteoderms (which are intramembranous ossification

Intramembranous ossification is one of the two essential processes during fetal development of the gnathostome (excluding chondrichthyans such as sharks) skeletal system by which rudimentary bone tissue is created.