Theodor Fritsch on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

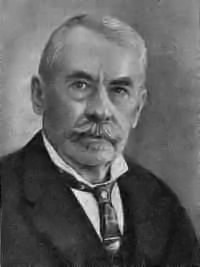

Theodor Fritsch (born Emil Theodor Fritsche; 28 October 1852 – 8 September 1933) was a German publisher and

Theodor Fritsch (born Emil Theodor Fritsche; 28 October 1852 – 8 September 1933) was a German publisher and

Fritsch created an early discussion forum, "Antisemitic Correspondence" in 1885 for antisemites of various political persuasions. In 1887 he sent several editions to

Fritsch created an early discussion forum, "Antisemitic Correspondence" in 1885 for antisemites of various political persuasions. In 1887 he sent several editions to

''Antisemiten-Katechismus'' by Theodore Fritsch at archive.org

{{DEFAULTSORT:Fritsch, Theodor 1852 births 1933 deaths People from Nordsachsen People from the Province of Saxony German Protestants German Reform Party politicians German Völkisch Freedom Party politicians National Socialist Freedom Movement politicians Members of the Reichstag 1924 German political scientists Relativity critics Antisemitism in Germany People convicted of speech crimes Prisoners and detainees of Germany

Theodor Fritsch (born Emil Theodor Fritsche; 28 October 1852 – 8 September 1933) was a German publisher and

Theodor Fritsch (born Emil Theodor Fritsche; 28 October 1852 – 8 September 1933) was a German publisher and journalist

A journalist is a person who gathers information in the form of text, audio or pictures, processes it into a newsworthy form and disseminates it to the public. This is called journalism.

Roles

Journalists can work in broadcast, print, advertis ...

. His antisemitic writings did much to influence popular German opinion against Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His writings also appeared under the pen names Thomas Frey, Fritz Thor, and Ferdinand Roderich-Stoltheim.

As a politician and organiser of the ''völkisch'' movement in the German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

, Fritsch was a member of the German Social Party (1889–1893), founder of the '' Reichshammerbund'' and the '' Germanenorden'' (Germanic Order; both in 1912). He was also a promotor of the garden city movement

The garden city movement was a 20th century urban planning movement promoting satellite communities surrounding the central city and separated with Green belt, greenbelts. These Garden Cities would contain proportionate areas of residences, i ...

. During the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic, officially known as the German Reich, was the German Reich, German state from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional republic for the first time in history; hence it is also referred to, and unofficially proclai ...

he co-founded the antisemitic '' Deutschvölkischer Schutz- und Trutzbund'' (German Nationalist Protection and Defiance Federation) and the far-right German Völkisch Freedom Party (1922). In May 1924 he was elected to the Reichstag, representing the National Socialist Freedom Party (NSFP). Fritsch is considered an intellectual forerunner of Nazism

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During Hitler's rise to power, it was fre ...

and was regarded by Nazi leaders as the "doyen of the movement".

He is not to be confused with his son, also named Theodor Fritsch (1895–1946) and also a bookseller, who was a member of the paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party, the Sturmabteilung

The (; SA; or 'Storm Troopers') was the original paramilitary organisation under Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party of Germany. It played a significant role in Adolf Hitler's rise to power, Hitler's rise to power in the 1920s and early 1930s. I ...

.

Life

Fritsch was born Emil Theodor Fritsche, the sixth of seven children to Johann Friedrich Fritsche, a farmer in the village of Wiesenena (present-day Wiedemar) in the Prussian province ofSaxony

Saxony, officially the Free State of Saxony, is a landlocked state of Germany, bordering the states of Brandenburg, Saxony-Anhalt, Thuringia, and Bavaria, as well as the countries of Poland and the Czech Republic. Its capital is Dresden, and ...

, and his wife August Wilhelmine, née Ohme. Four of his siblings died in childhood. He attended vocational school (''Realschule

Real school (, ) is a type of secondary school in Germany, Switzerland and Liechtenstein. It has also existed in Croatia (''realna gimnazija''), the Austrian Empire, the German Empire, Denmark and Norway (''realskole''), Sweden (''realskola''), F ...

'') in Delitzsch where he learned casting and machine building. He then undertook study at the Royal Trade Academy (''Königliche Gewerbeakademie'') in Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

, graduating as a technician in 1875.

In the same year Fritsche found employment in a Berlin machine shop. He gained independence in 1879 through the founding of a technical bureau associated with a publishing firm. In 1880 he founded the ''Deutscher Müllerbund'' (Miller's League) which issued the publication ''Der Deutsche Müller'' (The German Miller). In 1905 he founded the "Saxon Small Business Association." He devoted himself to this organization and to the interests of crafts and small businesses ('' Mittelstand''), as well as to the spread of antisemitic propaganda. When he changed his name to Fritsch is unclear.

Publishing

Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher. He began his career as a classical philology, classical philologist, turning to philosophy early in his academic career. In 1869, aged 24, Nietzsche bec ...

but was brusquely dismissed. Nietzsche sent Fritsch a letter in which he thanked him to be permitted "to cast a glance at the muddle of principles that lie at the heart of this strange movement", but requested not to be sent again such writings, for he was afraid that he might lose his patience. Fritsch offered editorship to right-wing politician Max Liebermann von Sonnenberg in 1894, whereafter it became an organ for Sonnenberg's German Social Party under the name "German Social Articles." Fritsch' 1896 book ''The City of the Future'' became a blueprint of the German garden city movement

The garden city movement was a 20th century urban planning movement promoting satellite communities surrounding the central city and separated with Green belt, greenbelts. These Garden Cities would contain proportionate areas of residences, i ...

which was adopted by '' Völkisch'' circles.

In 1902 Fritsch founded a Leipzig

Leipzig (, ; ; Upper Saxon: ; ) is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Saxony. The city has a population of 628,718 inhabitants as of 2023. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, eighth-largest city in Ge ...

publishing house, ''Hammer-Verlag'', whose flagship publication was ''The Hammer: Pages for German Sense'' (1902–1940). The firm issued German translations of ''The Protocols of the Elders of Zion

''The Protocols of the Elders of Zion'' is a fabricated text purporting to detail a Jewish plot for global domination. Largely plagiarized from several earlier sources, it was first published in Imperial Russia in 1903, translated into multip ...

'' and '' The International Jew'' (collected writings of Henry Ford from '' The Dearborn Independent'') as well as many of Fritsch's own works. An inflammatory article published in 1910 earned him a charge of defamation

Defamation is a communication that injures a third party's reputation and causes a legally redressable injury. The precise legal definition of defamation varies from country to country. It is not necessarily restricted to making assertions ...

of religious societies and disturbing the public peace. Fritsch was sentenced to one week in prison, and received another ten-day term in 1911.

Political activities

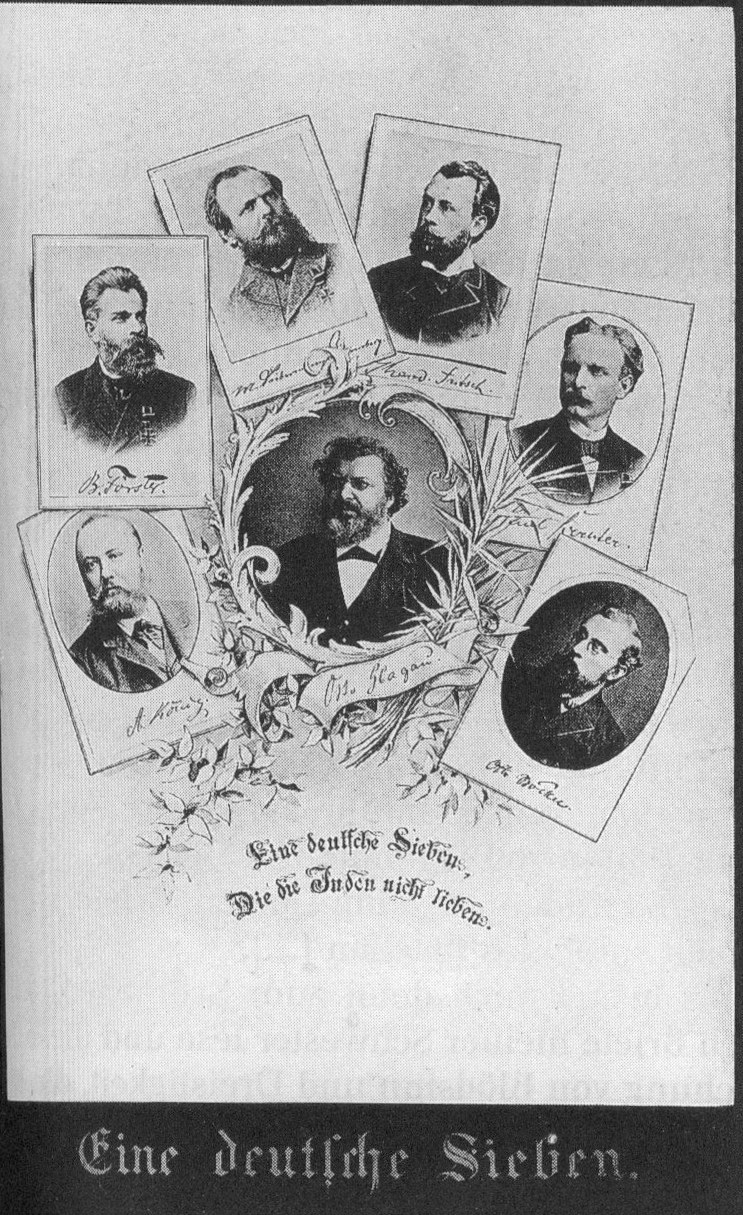

In 1890, Fritsch became, along with Otto Böckel, a candidate of the German Reform Party, founded by Böckel and Oswald Zimmermann, to the German Reichstag. He was not elected. The party was renamed German Reform Party in 1893, achieving sixteen seats. The party failed, however, to achieve significant public recognition. One of Fritsch's major goals was to unite all antisemitic political parties under a single banner; he wished for antisemitism to permeate the agenda of every German social and political organization. This effort proved largely to be a failure, as by 1890 there were over 190 various antisemitic parties in Germany. He also had a powerful rival for the leadership of the antisemites in Otto Böckel, with whom he had a strong personal rivalry. In 1912 Fritsch founded the '' Reichshammerbund'' (Reich's Hammer League) as an antisemitic collective movement. He also established the secret '' Germanenorden'' in that year. Influenced by racist Ariosophic theories, it was one of the first political groups to adopt theswastika

The swastika (卐 or 卍, ) is a symbol used in various Eurasian religions and cultures, as well as a few Indigenous peoples of Africa, African and Indigenous peoples of the Americas, American cultures. In the Western world, it is widely rec ...

symbol. Members of these groups formed the Thule Society in 1918, which eventually sponsored the creation of the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party ( or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported the ideology of Nazism. Its precursor ...

.

The ''Reichshammerbund'' was eventually folded into the '' Deutschvölkischer Schutz und Trutzbund'' (German Nationalist Protection and Defiance Federation), on whose advisory board Fritsch sat. He later became a member of the German Völkisch Freedom Party (DFVP). In the general election of May 1924, Fritsch was elected to serve as a member of the National Socialist Freedom Movement, a party formed in alliance with the DFVP by the Nazis as a legal means to election after the Nazi Party had been banned in the aftermath of the Munich Beer Hall Putsch. He only served until the next election in December, 1924.

In February 1927, Fritsch left the Völkisch Freedom Party in protest. He died shortly after the 1933 Nazi seizure of power at the age of 80 in Gautzsch (today part of Markkleeberg).

A memorial to Fritsch, described as "the first antisemitic memorial in Germany", was erected in Zehlendorf (Berlin) in 1935. The memorial was the idea of Zehlendorf's mayor, Walter Helfenstein (1890–1945), and the work of Arthur Wellmann (1885–1960). The memorial was melted down in 1943 to make armaments for the war.

Works

A believer in the absolute superiority of theAryan race

The Aryan race is a pseudoscientific historical race concepts, historical race concept that emerged in the late-19th century to describe people who descend from the Proto-Indo-Europeans as a Race (human categorization), racial grouping. The ter ...

, Fritsch was upset by the changes brought on by rapid industrialization

Industrialisation (British English, UK) American and British English spelling differences, or industrialization (American English, US) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an i ...

and urbanization

Urbanization (or urbanisation in British English) is the population shift from Rural area, rural to urban areas, the corresponding decrease in the proportion of people living in rural areas, and the ways in which societies adapt to this change. ...

, and called for a return to the traditional peasant values and customs of the distant past, which he believed exemplified the essence of the ''Volk

The German noun ''Volk'' () translates to :wikt:people, people,

both uncountable in the sense of ''people'' as in a crowd, and countable (plural ''Völker'') in the sense of ''People, a people'' as in an ethnic group or nation (compare the E ...

''.

In 1893, Fritsch published his most famous work, ''The Handbook of the Jewish Question'', which leveled a number of conspiratorial charges at European Jews and called upon Germans to refrain from intermingling with them. Vastly popular, the book was read by millions and was in its 49th edition by 1944 (330,000 copies). The ideas espoused by the work greatly influenced Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

and the Nazis

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

during their rise to power after World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. Fritsch also founded an anti-semitic journal – the ''Hammer'' – in 1902, and this became the basis of a movement, the Reichshammerbund, in 1912.

Fritsch was an opponent of Albert Einstein's theory of relativity

The theory of relativity usually encompasses two interrelated physics theories by Albert Einstein: special relativity and general relativity, proposed and published in 1905 and 1915, respectively. Special relativity applies to all physical ph ...

. He published ''Einsteins Truglehre'' (Einstein's Fraudulent Teachings) in 1921, under the pseudonym F. Roderich-Stoltheim (an anagram of his full name).Stachel, John J. (1987). ''The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein: The Berlin Years: Writings, 1918-1921''. Princeton University Press. p. 121

Another work, ''The Riddle of the Jew's Success'', was published in English in 1927 under the pseudonym F. Roderich-Stoltheim.

References

External links

''Antisemiten-Katechismus'' by Theodore Fritsch at archive.org

{{DEFAULTSORT:Fritsch, Theodor 1852 births 1933 deaths People from Nordsachsen People from the Province of Saxony German Protestants German Reform Party politicians German Völkisch Freedom Party politicians National Socialist Freedom Movement politicians Members of the Reichstag 1924 German political scientists Relativity critics Antisemitism in Germany People convicted of speech crimes Prisoners and detainees of Germany