Background

The Roman EmperorActivity of the Inquisition

Start of the Inquisition against Jewish ''conversos''

Fray Alonso de Ojeda, a Dominican friar from Seville, convinced Queen Isabella of the existence of

Fray Alonso de Ojeda, a Dominican friar from Seville, convinced Queen Isabella of the existence of The Trials

Torquemada quickly established procedures for the Inquisition. In 1484, based onExpulsion of Jews and Jewish ''conversos''

The Spanish Inquisition had been established in part to prevent ''conversos'' from engaging in Jewish practices. The Inquisitor Torquemada convinced the monarchs that the remaining unbaptized Jews still posed a threat. Thus, in 1492 they issued theExpulsion of Muslim ''conversos''

The Inquisition searched for false or relapsed converts among the''The Assimilation of Spain's Moriscos: Fiction or Reality?''

. Journal of Levantine Studies, vol. 1, no. 2, Winter 2011, pp. 11–30 Nevertheless, the eastern region of Valencia, where ethnic tensions were high, was particularly affected by the expulsion, suffering economic collapse and depopulation of much of its territory. Of those permanently expelled, the majority finally settled in the Maghreb or the Barbary coast. Those who avoided expulsion or who managed to return were gradually absorbed by the dominant culture. The Inquisition pursued some trials against Moriscos who remained or returned after expulsion: at the height of the Inquisition, cases against Moriscos are estimated to have constituted less than 10 percent of those judged by the Inquisition. Upon the coronation of Philip IV in 1621, the new king gave the order to desist from attempting to impose measures on the remaining Moriscos and returnees. In September 1628, the Council of the Supreme Inquisition ordered inquisitors in Seville not to prosecute expelled Moriscos "unless they cause significant commotion." The last mass prosecution against Moriscos for crypto-Islamic practices occurred in Granada in 1727, with most of those convicted receiving relatively light sentences. By the end of the 18th century, the indigenous practice of Islam is considered to have been effectively extinguished in Spain.

Blood purity statutes

During the Spanish Inquisition, ''Christian heretics

Protestantism

Despite popular myths about the Spanish Inquisition relating to Protestants, it dealt with very few cases involving actual Protestants, as there were so few in Spain. Lutheran was an accusation used by the Inquisition to act against all those who acted in a way that was offensive to the church. The first of the trials against those labeled by the Inquisition as "Lutheran" were those against the sect of mysticism, mystics known as the "Alumbrados" of Guadalajara (province), Guadalajara andMost of them were in no sense Protestants ... Irreligious sentiments, drunken mockery, anticlerical expressions, were all captiously classified by the inquisitors (or by those who denounced the cases) as "Lutheran." Disrespect to church images, and eating meat on forbidden days, were taken as signs of heresy...It is estimated that a dozen Protestant Spaniards were burned alive at the stake in the later part of the sixteenth century. Protestantism was treated as a marker to identify agents of foreign powers and symptoms of political disloyalty as much as, if not more than, a cause of prosecution in itself.

Orthodox Christianity

Even though the Inquisition may have had theoretical permission to investigate Orthodox schismatics, it rarely did. There was no major war between Spain and any Orthodox country, so there was no reason to do so. There was one casualty tortured by those "Jesuits" (though most likely Franciscans) who administered the Spanish Inquisition in North America, according to authorities within the Eastern Orthodox Church: St. Peter the Aleut. Even that single report has various numbers of inaccuracies that make it problematic, and has no confirmation in the Inquisitorial archives.Witchcraft and superstition

The category "superstitions" includes trials related to witchcraft. The witch-hunt in Spain had much less intensity than in other European countries (particularly France, Scotland, and Germany). One remarkable case was Logroño witch trials, that of Logroño, in which the witches of Zugarramurdi inBlasphemy

Included under the rubric of ''heretical propositions'' were verbal offences, from outright blasphemy to questionable statements regarding religious beliefs, from issues of sexual morality to misbehaviour of the clergy. Many were brought to trial for affirming that ''simple fornication'' (sex between unmarried persons) was not a sin or for putting in doubt different aspects of Christianity, Christian faith, such as Transubstantiation or the virginity of Blessed Virgin Mary, Mary. Also, members of the clergy themselves were occasionally accused of heretical propositions. These offences rarely led to severe penalties.Sodomy

Pope Clement VII granted the Inquisition jurisdiction over sodomy within Aragon in 1524 in response to a petition from the Saragossa tribunal. The Inquisition in Castile declined to take the same jurisdiction, making sodomy the only major crime with such a significant regional discrepancy. Even within Aragon, the treatment of sodomy varied significantly by region because the pope's decree required that it be prosecuted according to each area's local law. For instance, contemporaries considered the tribunal of the city of Zaragoza unusually harsh. The first person known to have been executed by the Inquisition for sodomy was a priest, Salvador Vidal, in 1541. Others convicted of sodomy received sentences including fines, burning in effigy, public whipping, and the galleys. The first burning for sodomy took place in Valencia in 1572. Sodomy was an expansive term; while a 1560 decision ruled that lesbian sex not involving a dildo could not be prosecuted as sodomy, bestiality routinely was, especially in Saragossa in the 1570s. Men might also be prosecuted based on accusations of engaging in heterosexual sodomy with their wives. For that time and place, the word "sodomy" covered several kinds of not procreative sexual acts denounced by the Church, like ''coitus interruptus'', masturbation, ''fellatio'', Anal sex, anal coitus (whether heterosexual or homosexual), etc. Those accused included 19% clergy, 6% nobles, 37% workers, 19% servants, and 18% soldiers and sailors. Nearly all of almost 500 cases of sodomy between persons concerned the relationship pederasty, between an older man and an adolescent, often by coercion, with only a few cases where the couple were consenting homosexual adults. About 100 of the total involved allegations of child abuse. Adolescents were typically punished more leniently than adults, but only when they were very young (approximately below the age of twelve) or when the case concerned rape did they have a chance to avoid punishment altogether. Prosecutions for sodomy gradually declined, primarily due to decisions from the Suprema intended to reduce the publicity for sodomy cases. In 1579, public ''autos de fe'' ceased to include people convicted on sodomy charges unless they were sentenced to death; even the death sentences were excluded from public proclamation after 1610. In 1589, Aragon raised the minimum age for sodomy executions to 25, and by 1633, executions for sodomy had generally come to an end.Freemasonry

The Roman Catholic Church has regarded Freemasonry as heretical since about 1738; the ''suspicion'' of Freemasonry was potentially a capital offence. Spanish Inquisition records reveal two prosecutions in Spain and only a few more throughout the Spanish Empire. In 1815, Francisco Javier de Mier y Campillo, the Inquisitor General of the Spanish Inquisition and the Bishop of Almería, suppressed Freemasonry and denounced the lodges as "societies which lead to atheism, to sedition and to all errors and crimes."William R. Denslow, Harry S. Truman: ''10,000 Famous Freemasons'', . He then instituted a purge during which Spaniards could be arrested on the charge of being "suspected of Freemasonry".Censorship

As one manifestation of the Counter-Reformation, the Spanish Inquisition worked to impede the diffusion of heretical ideas in Spain by producing "Indexes" of prohibited books. Such lists of prohibited books were common in Europe a decade before the Inquisition published its first. The first Index published in Spain in 1551 was, in reality, a reprinting of the Index published by the Old University of Leuven, University of Leuven in 1550, with an appendix dedicated to Spanish texts. Subsequent Indexes were published in 1559, 1583, 1612, 1632, and 1640. Included in the Indices, at one point, were some of the great works of Spanish literature, but most of the works were plays and religious in nature. A number of religious writers who are today considered saints by the Catholic Church saw their works appear in the Indexes. At first, this might seem counter-intuitive or even nonsensical—it fails to answer how these Spanish authors were published in the first place if their texts were then prohibited by the Inquisition and placed in the Index. The answer lies in the process of publication and censorship in Early Modern Spain. Books in Early Modern Spain faced prepublication licensing and approval (which could include modification) by both secular and religious authorities. Once approved and published, the circulating text also faced the possibility of post-hoc censorship by being denounced by the Inquisition—sometimes decades later. Likewise, as Catholic theology evolved, once-prohibited texts might be removed from the Index. At first, inclusion in the Index meant total prohibition of a text. This proved not only impractical but also contrary to the goals of having a literate and well-educated clergy. In time, a compromise solution was adopted in which trusted Inquisition officials blotted out words, lines, or whole passages of otherwise acceptable texts, thus allowing these expurgated editions to circulate. Although, in theory, the Indexes imposed enormous restrictions on the diffusion of culture in Spain, some historians argue that such strict control was impossible in practice and that there was much more liberty in this respect than is often believed. Irving Leonard has conclusively demonstrated that despite repeated royal prohibitions, romances of chivalry, such as ''Amadis de Gaula, Amadis of Gaul'', found their way to the New World with the blessing of the Inquisition. Moreover, with the coming of the Age of Enlightenment in the 18th century, increasing numbers of licenses to possess and read prohibited texts were granted. Despite the repeated publication of the Indexes and a large bureaucracy of censors, the activities of the Inquisition did not impede the development of Spanish literature's "Spanish Golden Age, Siglo de Oro", although almost all of its major authors crossed paths with the Holy Office at one point or another. Among the Spanish authors included in the Index are Bartolomé Torres Naharro, Juan del Enzina, Jorge de Montemayor, Juan de Valdés and Lope de Vega, as well as the anonymous ''Lazarillo de Tormes'' and the ''Cancionero General'' by Hernando del Castillo. ''La Celestina'', which was not included in the Indexes of the 16th century, was expurgated in 1632 and prohibited in its entirety in 1790. Among the non-Spanish authors prohibited were Ovid, Dante, Rabelais, Ariosto, Machiavelli, Erasmus, Jean Bodin, Valentin Naboth#cite note-13, Valentine Naibod, and Thomas More (known in Spain as Tomás Moro). One of the most outstanding and best-known cases in which the Inquisition directly confronted literary activity is that of Fray Luis de León, noted humanist and religious writer of converso origin, who was imprisoned for four years (from 1572 to 1576) for having translated the Song of Songs directly from Hebrew. One of the major effects of the Inquisition was to end free thought and scientific thought in Spain. As one contemporary Spaniard in exile put it: "Our country is a land of pride and envy ... barbarian, barbarism; down there one cannot produce any culture without being suspected of heresy, error andFamily and marriage

Bigamy

The Inquisition also pursued offences against morals and general social order, at times in open conflict with the jurisdictions of civil tribunals. In particular, there were trials for bigamy, a relatively frequent offence in a society that only permitted divorce under the most extreme circumstances. In the case of men, the penalty was two hundred lashes and five to ten years of "service to the Crown". Said service could be whatever the court deemed most beneficial for the nation, but it usually was either five years as an oarsman in a royal galley for those without any qualification (possibly a death sentence) or ten years working maintained but without salary in a public Hospital or charitable institution of the sort for those with some special skill, such as doctors, surgeons, or lawyers. The penalty was five to seven years as an oarsman in the case of Portugal.Unnatural marriage

Under the category of "unnatural marriage" fell any marriage or attempted marriage between two individuals who could not procreate. The Catholic Church, in general, and in a nation constantly at war like Spain, emphasised the reproductive goal of marriage. The Spanish Inquisition's policy in this regard was restrictive but applied in a very egalitarian way. It considered any non-reproductive marriage unnatural and any reproductive marriage natural, regardless of gender or sex involved. The two forms of obvious male sterility were either due to damage to the genitals through castration or accidental wounding at war (capón) or to some genetic condition that might keep the man from completing puberty (lampiño). Female sterility was also a reason to declare a marriage unnatural but was harder to prove. One case that dealt with marriage, sex, and gender was the trial of Eleno de Céspedes.Non-religious crimes

The notion of religion and civil law being separate is a modern construction and made no sense in the 15th century, so there was no difference between breaking a law regarding religion and breaking a law regarding tax collection. The difference between them is a modern projection the institution itself did not have. As such, the Inquisition was the prosecutor (in some cases the only prosecutor) of any crimes that could be perpetrated without the public taking notice (mainly domestic crimes, crimes against the weakest members of society, administrative crimes and forgeries, organized crime, and crimes against the Crown). Examples include crimes associated with sexual or family relations such as rape and sexual violence (the Inquisition was the first and only body who punished it across the nation), bestiality, pedophilia (often overlapping with sodomy), incest, child abuse or child neglect, neglect and (as discussed) bigamy. Non-religious crimes also included procurement (not prostitution), human trafficking, smuggling, forgery or falsification of counterfeit currency, currency, documents or signature forgery, signatures, tax fraud (many religious crimes were considered subdivisions of this one), illegal weapons, wikt:swindle, swindles, disrespect to the Crown or its institutions (the Inquisition included, but also the church, the guard, and the kings themselves), espionage for a foreign power, conspiracy, treason. The non-religious crimes processed by the Inquisition accounted for a considerable percentage of its total investigations and are often hard to separate in the statistics, even when documentation is available. The line between religious and non-religious crimes did not exist in 15th-century Spain as a legal concept. Many of the crimes listed here and some of the religious crimes listed in previous sections were contemplated under the same article. For example, "sodomy" included paedophilia as a subtype. Often, part of the data given for prosecution of male homosexuality corresponds to convictions for paedophilia, not adult homosexuality. In other cases, religious and non-religious crimes were seen as distinct but equivalent. The treatment of public blasphemy and street swindlers was similar (since both involved "misleading the public in a harmful way"). Making counterfeit currency and heretic proselytism were also treated similarly; both of them were punished by death and subdivided in similar ways since both were "spreading falsifications". In general, heresy and falsifications of material documents were treated similarly by the Spanish Inquisition, indicating that they may have been thought of as equivalent actions. Trials were often further complicated by the attempts of witnesses or victims to add further charges, especially witchcraft. Like with Eleno de Céspedes, charges for witchcraft done in this way, or in general, were quickly dismissed but they often show in the statistics as investigations made.Organization

Beyond its role in religious affairs, the Inquisition was also an institution at the service of the monarchy. The Inquisitor General, in charge of the Holy Office, was designated by the crown. The Inquisitor General was the only public office whose authority stretched to all the kingdoms of Spain (including the American viceroyalties), except for a brief period (1507–1518) during which there were two Inquisitors General, one in the kingdom of Castile, and the other in Aragon.Inquisitor General

The Grand Inquisitor, Inquisitor General presided over the Council of the Supreme and General Inquisition (commonly abbreviated as "Council of the Suprema"), created in 1483, which was made up of six members named directly by the crown (the number of members of the Suprema varied throughout the Inquisition's history, but it was never more than ten). Over time, the authority of the Suprema grew at the expense of the power of the Inquisitor General.

The Grand Inquisitor, Inquisitor General presided over the Council of the Supreme and General Inquisition (commonly abbreviated as "Council of the Suprema"), created in 1483, which was made up of six members named directly by the crown (the number of members of the Suprema varied throughout the Inquisition's history, but it was never more than ten). Over time, the authority of the Suprema grew at the expense of the power of the Inquisitor General.

The Council of Castile and the Council of the Supreme and General Inquisition

By the 17th century, two councilors from the Royal Council of Castile played a key role in overseeing the Council of the Spanish Inquisition, advising the monarchy on legal and religious matters. At this time, the Spanish Inquisition consisted of six primary councilors, two afternoon members from the Royal Council of Castile, and a permanent Dominican seat. Additionally, the ''fiscal'' (prosecutor) was responsible for managing inquisitorial trials and legal proceedings. With royal approval, the Council adjusted its structure to improve efficiency, including chamber divisions for handling cases. Notable members included:Fernández Gimén, María del Camino. "''El Origen y Fundación de las Inquisiciones de España''" by José de Rivera. Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia, vol. 23, pp. 11–46. ISSN 1131-5571. * Joseph González, Commissary General of the Crusade, Councilor of Castile * Juan Martínez, Dominican friar * Diego Sarmiento Valladares, Diego Sarmiento de Valladares * Gabriel de la Calle y Heredia * Bernardino de León de la Rocha * Francisco de Lara * Martín de Castejón * Doctor of Canon Law (Catholic Church), Doctor Gaspar de Medrano, the second-ranking Councilor of Castile The Royal Council and the Inquisition remained deeply intertwined, enforcing religious conformity while serving as an instrument of monarchical control.Schedule

The ''Suprema'' met every morning, except for holidays, and for two hours in the afternoon on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays. The morning sessions were devoted to questions of faith, while the afternoons were reserved for "minor heresies," cases of perceived unacceptable sexual behavior, bigamy, witchcraft, etc.Tribunals

Below the Suprema were the various tribunals of the Inquisition, initially itinerant, which installed themselves where they were necessary to combat heresy but later settled in fixed locations. During the first phase, numerous tribunals were established, but the period after 1495 saw a marked tendency towards centralization. In the kingdom of Castile, the following permanent tribunals of the Inquisition were established: * 1482 InComposition of the tribunals

Initially, each of the tribunals included two inquisitors, ''calificadors'' (qualifiers), an ''alguacil'' (bailiff), and a ''fiscal'' (prosecutor); new positions were added as the institution matured. The inquisitors were preferably jurists more than theologians; in 1608, Philip III even stipulated that all inquisitors needed to have a background in law. The inquisitors rarely remained in the position for a long time: for the Court of Valencia (autonomous community), Valencia, for example, the average tenure in the position was about two years. Most of the inquisitors belonged to the secular clergy (priests who were not members of religious orders) and had a university education. The ''fiscal'' was in charge of presenting the accusation, investigating the denunciations, and interrogating the witnesses by the use of physical and mental torture. The ''calificadores'' were generally theologians; it fell to them to determine whether the defendant's conduct added up to a crime against the faith. Consultants were expert jurists who advised the court on questions of procedure. The court had, in addition, three secretaries: the ''notario de secuestros'' (Notary of Property), who registered the goods of the accused at the moment of his detention; the ''notario del secreto'' (Notary of the Secret), who recorded the testimony of the defendant and the witnesses; and the ''Escribano General'' (General Notary), secretary of the court. The ''alguacil'' was the executive arm of the court, responsible for detaining, jailing, and physically torturing the defendant. Other civil employees were the ''nuncio'', ordered to spread official notices of the court, and the ''alcaide'', the jailer in charge of feeding the prisoners. In addition to the members of the court, two auxiliary figures existed that collaborated with the Holy Office: the ''familiares'' and the ''comissarios'' (commissioners). ''Familiares'' were lay collaborators of the Inquisition who had to be permanently at the service of the Holy Office. To become a ''familiar'' was considered an honor since it was a public recognition of ''Your Majesty must provide, before all else, that the expenses of the Holy Office do not come from the properties of the condemned, because if that is the case if they do not burn they do not eat.

Mode of operation

Accusation

When the Inquisition arrived in a city, the first step was the ''Edict of Grace''. Following the Sunday Mass, the Inquisitor would proceed to read the edict, which described possible heresies and encouraged all the congregation to come to the tribunals of the Inquisition to "relieve their consciences". They were called ''Edicts of Grace'' because all the self-incriminated who presented themselves within a ''period of grace'' (usually ranging from thirty to forty days) were offered the possibility of reconciliation with the Church without severe punishment. The promise of benevolence was effective, and many voluntarily presented themselves to the Inquisition. These were encouraged to denounce others who had also committed offences, informants being the Inquisition's primary source of information. After about 1500, the Edicts of Grace were replaced by the ''Edicts of Faith'', which left out the grace period and instead encouraged the denunciation of those deemed guilty. The denunciations were anonymous, and the defendants had no way of knowing the identities of their accusers. This was one of the points most criticized by those who opposed the Inquisition. In practice, false denunciations were frequent. Denunciations were made for a variety of reasons apart from genuine concern. Some just went after non-conformists. Others wished to hurt a neighbor or get rid of an opponent. This method turned everyone into an agent of the Inquisition and made everyone aware that a simple word or deed could bring them before the tribunal. Denunciation was elevated to the rank of a superior religious duty, filled the nation with spies, and made each individual an object of suspicion to their neighbor, family, and any strangers they might meet.Detention

After a denunciation, the case was examined by the ''calificadores'', who had to determine whether there was heresy involved. This was followed by the detention of the accused. In practice, many were detained in preventive custody, and many cases of lengthy incarcerations occurred, lasting up to two years before the ''calificadores'' examined the case.

Detention of the accused entailed the preventive sequestration of their property by the Inquisition. The property of the prisoner was used to pay for procedural expenses and the accused's maintenance and costs. Often, the relatives of the defendant found themselves in outright misery. This situation was remedied only by following instructions written in 1561. However, Llorente, despite having consulted numerous records of old Inquisition proceedings, did not find any record of such an agreement in favor of the children of condemned heretics.

Some authors, such as apologist William Thomas Walsh, stated that the entire process was undertaken with the utmost secrecy, as much for the public as for the accused, who were not informed about the accusations that were levied against them. Months or even years could pass without the accused being informed about why they were imprisoned. The prisoners remained isolated, and, during this time, they were not allowed to attend mass (liturgy), Mass nor receive the sacraments. The jails of the Inquisition were no worse than those of secular authorities, and there are even certain testimonies that occasionally they were much better. According to William Walsh, the miseries of the Jews "are not the result, fundamentally, of the hatred and misunderstanding of others, but the consequence of their own stubborn Rejection of Jesus#Rejection as the Jewish messiah, rejection of Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ".

After a denunciation, the case was examined by the ''calificadores'', who had to determine whether there was heresy involved. This was followed by the detention of the accused. In practice, many were detained in preventive custody, and many cases of lengthy incarcerations occurred, lasting up to two years before the ''calificadores'' examined the case.

Detention of the accused entailed the preventive sequestration of their property by the Inquisition. The property of the prisoner was used to pay for procedural expenses and the accused's maintenance and costs. Often, the relatives of the defendant found themselves in outright misery. This situation was remedied only by following instructions written in 1561. However, Llorente, despite having consulted numerous records of old Inquisition proceedings, did not find any record of such an agreement in favor of the children of condemned heretics.

Some authors, such as apologist William Thomas Walsh, stated that the entire process was undertaken with the utmost secrecy, as much for the public as for the accused, who were not informed about the accusations that were levied against them. Months or even years could pass without the accused being informed about why they were imprisoned. The prisoners remained isolated, and, during this time, they were not allowed to attend mass (liturgy), Mass nor receive the sacraments. The jails of the Inquisition were no worse than those of secular authorities, and there are even certain testimonies that occasionally they were much better. According to William Walsh, the miseries of the Jews "are not the result, fundamentally, of the hatred and misunderstanding of others, but the consequence of their own stubborn Rejection of Jesus#Rejection as the Jewish messiah, rejection of Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ".

Trial

The inquisitorial process consisted of a series of hearings in which both the denouncers and the defendant gave separate testimony. A defense counsel, a so-called lawyer, a member of the tribunal itself, was assigned to the defendant; his role was simply to advise the accused and to encourage them to speak the truth. He was obliged to renounce the defense at the moment when he realized his client's guilt.

The prosecution was directed by the ''fiscal''. Interrogation of the defendant was done in the presence of the ''notario del secreto'', who meticulously wrote down the words of the accused. The archives of the Inquisition, in comparison to those of other judicial systems of the era, are striking in the completeness of their documentation.

To defend themselves, the accused had two main choices: ''abonos'' (to find favourable and character witnesses) or ''tachas'' (to demonstrate that the witnesses of accusers — whose identity he did not know — were not trustworthy, and were his personal enemies.

The structure of the trials was similar to modern trials and, according to apologists, advanced for the time with regard to fairness. The Inquisition, "professional and efficient", was dependent on the political power of the King. The lack of separation of powers allows for assuming questionable fairness in certain scenarios. The fairness of the Inquisitorial tribunals is alleged by apologists to be among the best in early modern Europe when it came to the trial of laymen. There are also testimonies by former prisoners that, if believed, suggest that said fairness was less than ideal when national or political interests were involved.

The historian Walter Ullmann thinks very differently:

:::There is hardly one item in the whole Inquisitorial procedure that could be squared with the demands of justice; on the contrary, every one of its items is the denial of justice or a hideous caricature of it [...] its principles are the very denial of the demands made by the most primitive concepts of natural justice [...] This kind of proceeding has no longer any semblance to a judicial trial but is rather its systematic and methodical perversion.

To obtain a confession or information relevant to an investigation, the Inquisition used torture, as prescribed in the ''instrucciones''. It is impossible to determine with any degree of accuracy the number of cases in which it was employed during the Inquisition's existence.

Torture would be applied if the alleged heresy was "half proven" and could be repeated, according to Article XV of Torquemada's instructions. Henry Lea estimates that between 1575 and 1610, the court of

The inquisitorial process consisted of a series of hearings in which both the denouncers and the defendant gave separate testimony. A defense counsel, a so-called lawyer, a member of the tribunal itself, was assigned to the defendant; his role was simply to advise the accused and to encourage them to speak the truth. He was obliged to renounce the defense at the moment when he realized his client's guilt.

The prosecution was directed by the ''fiscal''. Interrogation of the defendant was done in the presence of the ''notario del secreto'', who meticulously wrote down the words of the accused. The archives of the Inquisition, in comparison to those of other judicial systems of the era, are striking in the completeness of their documentation.

To defend themselves, the accused had two main choices: ''abonos'' (to find favourable and character witnesses) or ''tachas'' (to demonstrate that the witnesses of accusers — whose identity he did not know — were not trustworthy, and were his personal enemies.

The structure of the trials was similar to modern trials and, according to apologists, advanced for the time with regard to fairness. The Inquisition, "professional and efficient", was dependent on the political power of the King. The lack of separation of powers allows for assuming questionable fairness in certain scenarios. The fairness of the Inquisitorial tribunals is alleged by apologists to be among the best in early modern Europe when it came to the trial of laymen. There are also testimonies by former prisoners that, if believed, suggest that said fairness was less than ideal when national or political interests were involved.

The historian Walter Ullmann thinks very differently:

:::There is hardly one item in the whole Inquisitorial procedure that could be squared with the demands of justice; on the contrary, every one of its items is the denial of justice or a hideous caricature of it [...] its principles are the very denial of the demands made by the most primitive concepts of natural justice [...] This kind of proceeding has no longer any semblance to a judicial trial but is rather its systematic and methodical perversion.

To obtain a confession or information relevant to an investigation, the Inquisition used torture, as prescribed in the ''instrucciones''. It is impossible to determine with any degree of accuracy the number of cases in which it was employed during the Inquisition's existence.

Torture would be applied if the alleged heresy was "half proven" and could be repeated, according to Article XV of Torquemada's instructions. Henry Lea estimates that between 1575 and 1610, the court of Torture

Torture was employed in all civil and religious trials in Europe. The Spanish Inquisition allegedly used it more restrictively than was common at the time. Unlike both civil trials and other inquisitions, it had strict regulations in relation to when, what, whom, frequency, duration, and supervision.Bethencourt, Francisco. La Inquisición En La Época Moderna: España, Portugal E Italia, Siglos xv–xix. Madrid: Akal, 1997. According to some scholars, the Spanish Inquisition engaged in torture less often and with greater care than secular courts.Peters, Edward, ''Inquisition'', Dissent, Heterodoxy and the Medieval Inquisitional Office, pp. 92–93, University of California Press (1989), .

Kamen and other scholars cite the lack of evidence for the use of torture. Their conclusions are based on research uncovered in newly opened files of the Spanish Inquisition's archives. Stories of torture and other maltreatment of prisoners appear to have been based on Protestant propaganda as well as popular imagination and ignorance.

* When: Torture was allowed when guilt was "half proven" or there existed a "presumption of guilt", as stated in Article XV of Torquemada's ''instruciones'' and in Eymerich's directions. However, Eymerich admits that information obtained through torment was not always reliable, and should be used only when all other means of obtaining "the truth" had failed.

* What: The Spanish Inquisition was not permitted to "maim, mutilate, draw blood or cause any sort of permanent damage" to the prisoner. Ecclesiastical tribunals were prohibited by church law from shedding blood. As a result of torture, many had broken limbs, or other definitive health problems, and some died.

* Supervision: A Physician was usually available in case of emergency. It was also required for a doctor to certify that the prisoner was healthy enough to go through the torment without suffering harm, which of course happened.

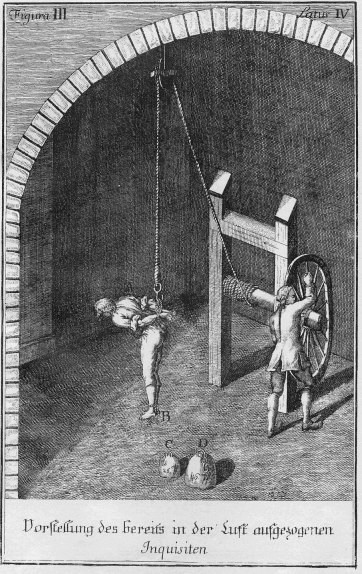

Among the methods of torture allowed were ''garrucha'', ''toca'', and the ''potro'' (which were all used in other secular and ecclesiastical tribunals). The application of the ''garrucha'', also known as the strappado, consisted of suspending the victim from the ceiling by the wrists, which are tied behind the back. Sometimes weights were tied to the feet, with a series of lifts and violent drops, during which the arms and legs suffered violent pulls and were sometimes dislocated.

The use of the ''toca'' (cloth), also called ''interrogatorio mejorado del agua'' (enhanced Water cure (torture), water interrogation), now known as waterboarding, is better documented. It consisted of forcing the victim to ingest water poured from a jar so that they had the impression of drowning. The ''potro'', the rack (torture), rack, in which the limbs were slowly pulled apart, was thought to be the instrument of torture used most frequently. The assertion that ''confessionem esse veram, non factam vi tormentorum'' (literally: '[a person's] confession is truth, not made by way of torture') sometimes follows a description of how, after torture had ended, the subject "freely" confessed to the offences. In practice, those who recanted confessions made during torture knew that they could be tortured again. Under torture, or even harsh interrogation, comments Cullen Murphy, people will say anything. Bernard Délicieux, the Franciscan friar who was tortured by the Inquisition and ultimately died in prison as a result of the abuse, said the Inquisition's tactics would have proved Saint Peter, St. Peter and Paul the Apostle, St. Paul to be heretics.

Once the process concluded, the inquisitors met with a representative of the bishop and with the ''consultores'' (consultants), experts in theology or Canon Law (but not necessarily clergy themselves), which was called the ''consulta de fe'' (faith consultation/religion check). The case was voted and sentence pronounced, which had to be unanimous. In case of discrepancies, the ''Suprema'' had to be informed.

Torture was employed in all civil and religious trials in Europe. The Spanish Inquisition allegedly used it more restrictively than was common at the time. Unlike both civil trials and other inquisitions, it had strict regulations in relation to when, what, whom, frequency, duration, and supervision.Bethencourt, Francisco. La Inquisición En La Época Moderna: España, Portugal E Italia, Siglos xv–xix. Madrid: Akal, 1997. According to some scholars, the Spanish Inquisition engaged in torture less often and with greater care than secular courts.Peters, Edward, ''Inquisition'', Dissent, Heterodoxy and the Medieval Inquisitional Office, pp. 92–93, University of California Press (1989), .

Kamen and other scholars cite the lack of evidence for the use of torture. Their conclusions are based on research uncovered in newly opened files of the Spanish Inquisition's archives. Stories of torture and other maltreatment of prisoners appear to have been based on Protestant propaganda as well as popular imagination and ignorance.

* When: Torture was allowed when guilt was "half proven" or there existed a "presumption of guilt", as stated in Article XV of Torquemada's ''instruciones'' and in Eymerich's directions. However, Eymerich admits that information obtained through torment was not always reliable, and should be used only when all other means of obtaining "the truth" had failed.

* What: The Spanish Inquisition was not permitted to "maim, mutilate, draw blood or cause any sort of permanent damage" to the prisoner. Ecclesiastical tribunals were prohibited by church law from shedding blood. As a result of torture, many had broken limbs, or other definitive health problems, and some died.

* Supervision: A Physician was usually available in case of emergency. It was also required for a doctor to certify that the prisoner was healthy enough to go through the torment without suffering harm, which of course happened.

Among the methods of torture allowed were ''garrucha'', ''toca'', and the ''potro'' (which were all used in other secular and ecclesiastical tribunals). The application of the ''garrucha'', also known as the strappado, consisted of suspending the victim from the ceiling by the wrists, which are tied behind the back. Sometimes weights were tied to the feet, with a series of lifts and violent drops, during which the arms and legs suffered violent pulls and were sometimes dislocated.

The use of the ''toca'' (cloth), also called ''interrogatorio mejorado del agua'' (enhanced Water cure (torture), water interrogation), now known as waterboarding, is better documented. It consisted of forcing the victim to ingest water poured from a jar so that they had the impression of drowning. The ''potro'', the rack (torture), rack, in which the limbs were slowly pulled apart, was thought to be the instrument of torture used most frequently. The assertion that ''confessionem esse veram, non factam vi tormentorum'' (literally: '[a person's] confession is truth, not made by way of torture') sometimes follows a description of how, after torture had ended, the subject "freely" confessed to the offences. In practice, those who recanted confessions made during torture knew that they could be tortured again. Under torture, or even harsh interrogation, comments Cullen Murphy, people will say anything. Bernard Délicieux, the Franciscan friar who was tortured by the Inquisition and ultimately died in prison as a result of the abuse, said the Inquisition's tactics would have proved Saint Peter, St. Peter and Paul the Apostle, St. Paul to be heretics.

Once the process concluded, the inquisitors met with a representative of the bishop and with the ''consultores'' (consultants), experts in theology or Canon Law (but not necessarily clergy themselves), which was called the ''consulta de fe'' (faith consultation/religion check). The case was voted and sentence pronounced, which had to be unanimous. In case of discrepancies, the ''Suprema'' had to be informed.

Sentencing

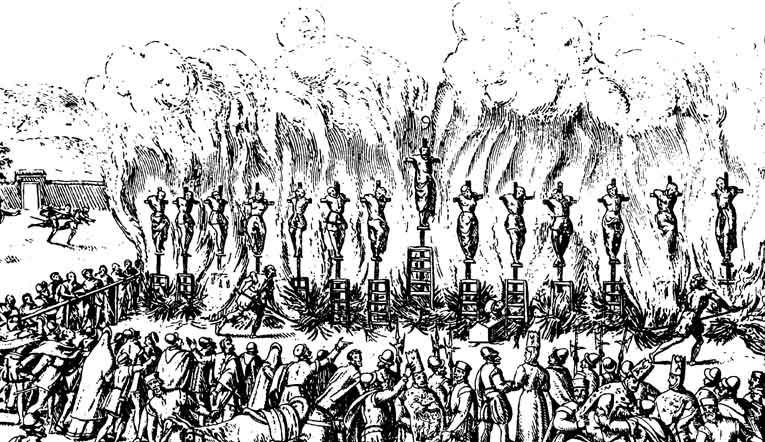

The results of the trial could be the following: # Although quite rare in actual practice, the defendant could be acquitted, but an acquittal was interpreted as a dishonourable reflection on the inquisitors. # The trial could be suspended, in which case the defendant, although under suspicion, went free (with the threat that the process could be reopened at any time). In the unusual instance of a defendant being declared not guilty during the trial, the decision was made in private. # The defendant could be penanced. Since they were considered guilty, they had to publicly abjure their crimes (''de levi'' if it was a misdemeanor, and ''de vehementi'' if the crime were serious), and accept a public punishment. Among these were ''sanbenito'', forced church attendance, exile, scourging, fines or even sentencing to service as oarsmen in royal galleys. # The defendant could be reconciled. In addition to the public ceremony in which the condemned was reconciled with the Catholic Church, more severe punishments were used, among them long sentences to jail or the galleys, plus the confiscation of all property. Physical punishments, such as whipping, were also used. The reconciled were prohibited from working as advocates, landlords, apothecaries, doctors, surgeons, and other professions. They were banned from carrying weapons, wearing jewelry or gold, and from riding horses. The restrictions also applied to the offspring of the convicted. # The most serious punishment was relaxation to the secular arm, i.e. Death by burning, burning at the stake. This penalty was frequently applied to impenitent heretics and those who had relapsed. Execution was public. If the condemned repented, they were "shown mercy" by being garroted before their corpse was burned; if not, they were burned alive. The victims were handed over to the secular authorities, who had no access to the process; they only administered the sentences and were obliged to do so on pain of heresy and excommunication. Frequently, cases were judged ''in absentia''. When the accused died before the trial finished, the condemned were burned in effigy. The death of an accused did not extinguish the inquisitorial actions, even up to forty years after the death. When it was considered proven that the deceased were heretics in their lifetime, their corpses were exhumed and burned, their property confiscated and the heirs disinherited. The distribution of the punishments varied considerably over time. It is believed that sentences of death were enforced most frequently in the early stages of the Inquisition. According to García Cárcel, one of the most active courts—the court of Valencia (autonomous community), Valencia—employed the death penalty in 40% of cases before 1530, but later that percentage dropped to 3%. By the middle of the 16th century, inquisition courts viewed torture as unnecessary, and death sentences had become rare.''Auto da fé''

If thesentence was wikt:condemnatory, condemnatory, this implied that the condemned had to participate in the ceremony of an ''auto de fe'' (more commonly known in English as an ''auto-da-fé'') that solemnized their return to the Church (in most cases), or punishment as an impenitent heretic. The ''autos de fe'' could be public (''auto publico'' or ''auto general'') or private (''auto particular'').

Although initially the public ''autos'' did not have any special solemnity nor sought a large attendance of spectators, with time they became expensive and solemn ceremonies, a display of the great power shared by the Church and the State, celebrated with large public crowds, amidst a festive atmosphere. The ''auto de fe'' eventually became a baroque spectacle, with staging meticulously calculated to cause the greatest effect among the spectators. The ''autos'' were conducted in a large public space (frequently in the largest plaza of the city), generally on holidays. The rituals related to the ''auto'' began the previous night (the "procession of the Green Cross") and sometimes lasted the whole day.

The ''auto de fe'' frequently was taken to the canvas by painters: one of the better-known examples is the 1683 painting by Francisco Rizi, held by the Prado Museum in Madrid that represents the ''auto da fe'' celebrated in the Plaza Mayor of Madrid on 30 June 1680. The last public ''auto da fe de fe'' took place in 1691.

If thesentence was wikt:condemnatory, condemnatory, this implied that the condemned had to participate in the ceremony of an ''auto de fe'' (more commonly known in English as an ''auto-da-fé'') that solemnized their return to the Church (in most cases), or punishment as an impenitent heretic. The ''autos de fe'' could be public (''auto publico'' or ''auto general'') or private (''auto particular'').

Although initially the public ''autos'' did not have any special solemnity nor sought a large attendance of spectators, with time they became expensive and solemn ceremonies, a display of the great power shared by the Church and the State, celebrated with large public crowds, amidst a festive atmosphere. The ''auto de fe'' eventually became a baroque spectacle, with staging meticulously calculated to cause the greatest effect among the spectators. The ''autos'' were conducted in a large public space (frequently in the largest plaza of the city), generally on holidays. The rituals related to the ''auto'' began the previous night (the "procession of the Green Cross") and sometimes lasted the whole day.

The ''auto de fe'' frequently was taken to the canvas by painters: one of the better-known examples is the 1683 painting by Francisco Rizi, held by the Prado Museum in Madrid that represents the ''auto da fe'' celebrated in the Plaza Mayor of Madrid on 30 June 1680. The last public ''auto da fe de fe'' took place in 1691.

The ''auto da fe de fe'' involved a Catholic Mass, prayer, a public procession of those found guilty, and a reading of their sentences. They took place in public squares or esplanades and lasted several hours; ecclesiastical and civil authorities attended. Artistic representations of the ''auto de fé de fe'' usually depict torture and the burning at the stake. This type of activity never took place during an ''auto de fé de fe'', which was in essence a religious act. Torture was not administered after a trial concluded, and executions were always held after and separate from the ''auto de fé de fe'', though in the minds and experiences of observers and those undergoing the confession and execution, the separation of the two might be experienced as merely a technicality.

The first recorded ''auto de fe'' was held in Paris in 1242, during the reign of Louis IX. The first Spanish ''auto de fe'' did not take place until 1481 in Seville; six of the men and women subjected to this first religious ritual were later executed by being burned alive at the stake.

The Inquisition had limited power in Portugal, having been established in 1536 and officially lasting until 1821, although its influence was much weakened with the government of the Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, 1st Marquis of Pombal, Marquis of Pombal in the second half of the 18th century. The Marquis, himself a ''familiar'', transformed it into a royal court, and the heretics continued to be persecuted, as so the "high spirits".

''Autos de fe'' also took place in Mexico, Brazil and Peru: contemporary historians of the Conquistadors such as Bernal Díaz del Castillo record them. They also took place in the Portuguese colony of Goa, India, following the establishment of Inquisition there in 1562–1563.

The ''auto da fe de fe'' involved a Catholic Mass, prayer, a public procession of those found guilty, and a reading of their sentences. They took place in public squares or esplanades and lasted several hours; ecclesiastical and civil authorities attended. Artistic representations of the ''auto de fé de fe'' usually depict torture and the burning at the stake. This type of activity never took place during an ''auto de fé de fe'', which was in essence a religious act. Torture was not administered after a trial concluded, and executions were always held after and separate from the ''auto de fé de fe'', though in the minds and experiences of observers and those undergoing the confession and execution, the separation of the two might be experienced as merely a technicality.

The first recorded ''auto de fe'' was held in Paris in 1242, during the reign of Louis IX. The first Spanish ''auto de fe'' did not take place until 1481 in Seville; six of the men and women subjected to this first religious ritual were later executed by being burned alive at the stake.

The Inquisition had limited power in Portugal, having been established in 1536 and officially lasting until 1821, although its influence was much weakened with the government of the Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, 1st Marquis of Pombal, Marquis of Pombal in the second half of the 18th century. The Marquis, himself a ''familiar'', transformed it into a royal court, and the heretics continued to be persecuted, as so the "high spirits".

''Autos de fe'' also took place in Mexico, Brazil and Peru: contemporary historians of the Conquistadors such as Bernal Díaz del Castillo record them. They also took place in the Portuguese colony of Goa, India, following the establishment of Inquisition there in 1562–1563.

Transformation in the Enlightenment

The arrival of the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment in Spain slowed inquisitorial activity. In the first half of the 18th century, 111 were condemned to be burned in person, and 117 in effigy, most of them for Judaizers, judaizing. In the reign of Philip V of Spain, Philip V, there were 125 ''autos de fe'', while in the reigns of Charles III of Spain, Charles III and Charles IV of Spain, Charles IV only 44. During the 18th century, the Inquisition changed: Enlightenment ideas were the closest threat that had to be fought. The main figures of the Spanish Enlightenment were in favour of the abolition of the Inquisition, and many were processed by the Holy Office, among them Pablo de Olavide, Olavide, in 1776; Tomás de Iriarte y Oropesa, Iriarte, in 1779; and Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos, Jovellanos, in 1796; Jovellanos sent a report to Charles IV in which he indicated the inefficiency of the Inquisition's courts and the ignorance of those who operated them: "... friars who take [the position] only to obtain gossip and exemption from the choir; who are ignorant of foreign languages, who only know a little scholastic theology." In its new role, the Inquisition tried to accentuate its function of censoring publications but found that Charles III had secularized censorship procedures, and, on many occasions, the authorization of the Council of Castile hit the more intransigent position of the Inquisition. Since the Inquisition itself was an arm of the state, being within the Council of Castile, civil rather than ecclesiastical censorship usually prevailed. This loss of influence can also be explained because the foreign Enlightenment texts entered the peninsula through prominent members of the nobility or government, influential people with whom it was very difficult to interfere. Thus, for example, Diderot's Encyclopedia entered Spain thanks to special licenses granted by the king. After the French Revolution the Council of Castile, fearing that revolutionary ideas would penetrate Spain's borders, decided to reactivate the Holy Office that was directly charged with the persecution of French works. An Inquisition edict of December 1789, that received the full approval of Charles IV and José Moñino y Redondo, conde de Floridablanca, Floridablanca, stated that:having news that several books have been scattered and promoted in these kingdoms... that, without being contented with the simple narration events of a seditious nature... seem to form a theoretical and practical code of independence from the legitimate powers.... destroying in this way the political and social order... the reading of thirty and nine French works is prohibited, under fine...The fight from within against the Inquisition was almost always clandestine. The first texts that questioned the Inquisition and praised the ideas of Voltaire or Montesquieu appeared in 1759. After the suspension of pre-publication censorship on the part of the Council of Castile in 1785, the newspaper ''El Censor'' began the publication of protests against the activities of the Holy Office by means of a rationalist critique. Valentin de Foronda published ''Espíritu de los Mejores Diarios'', a plea in favour of freedom of expression that was avidly read in the salons. Also, in the same vein, Manuel de Aguirre wrote On Toleration in ''El Censor'', ''El Correo de los Ciegos'' and ''El Diario de Madrid''.

End of the Inquisition

During the reign of Charles IV of Spain (1788–1808), in spite of the fears that the French Revolution provoked, several events accelerated the decline of the Inquisition. The state stopped being a mere social organizer and began to worry about the well-being of the public. As a result, the land-holding power of the Church was reconsidered, in the ''señoríos'' and more generally in the accumulated wealth that had prevented social progress. The power of the throne increased, under which Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers found better protection for their ideas. Manuel Godoy and Antonio Alcalá Galiano were openly hostile to an institution whose only role had been reduced to censorship and was the very embodiment of the Spanish Black Legend of the Spanish Inquisition, Black Legend, internationally, and was not suitable to the political interests of the moment:The Inquisition? Its old power no longer exists: the horrible authority that this bloodthirsty court had exerted in other times was reduced... the Holy Office had come to be a species of commission for book censorship, nothing more...The Inquisition was first abolished during the domination of Napoleon and the reign of Joseph Bonaparte (1808–1812). In 1813, the liberal deputies of the Cortes of Cádiz also obtained its abolition, largely as a result of the Holy Office's condemnation of the popular revolt against French invasion. But the Inquisition was reconstituted when Ferdinand VII of Spain, Ferdinand VII recovered the throne on 1 July 1814. Juan Antonio Llorente, who had been the Inquisition's general secretary in 1789, became a Afrancesado, Bonapartist and published a critical history in 1817 from his French exile, based on his privileged access to its archives. Possibly as a result of Llorente's criticisms, the Inquisition was once again temporarily abolished during the three-year Liberal interlude known as the Trienio liberal, but still the old system had not yet had its last gasp. Later, during the period known as the Ominous Decade, the Inquisition was not formally re-established, although, ''de facto'', it returned under the Congregation of the Meetings of Faith (), created in the dioceses by King Ferdinand VII. The last known person to be executed by the Inquisition was

Outcomes

Confiscations

It is unknown exactly how much wealth was confiscated from converted Jews and others tried by the Inquisition. Wealth confiscated in one year of persecution in the small town of Guadaloupe paid the costs of building a royal residence. There are numerous records of the opinion of ordinary Spaniards of the time that "the Inquisition was devised simply to rob people". "They were burnt only for the money they had", a resident of Cuenca averred. "They burn only the well-off", said another. In 1504 an accused stated, "only the rich were burnt". In 1484 Catalina de Zamora was accused of asserting that "this Inquisition that the fathers are carrying out is as much for taking property from the conversos as for defending the faith. It is the goods that are the heretics." This saying passed into common usage in Spain. In 1524 a treasurer informed Charles V that his predecessor had received ten million ducats from the conversos, but the figure is unverified. In 1592 an inquisitor admitted that most of the fifty women he arrested were rich. In 1676, the Suprema claimed it had confiscated over 700,000 ducats for the royal treasury (which was paid money only after the Inquisition's own budget, amounting in one known case to only 5%). The property on Mallorca alone in 1678 was worth "well over 2,500,000 ducats".Death tolls and sentenced

García Cárcel estimates that the total number prosecuted by the Inquisition throughout its history was approximately 150,000; applying the percentages of executions that appeared in the trials of 1560–1700—about 2%—the approximate total would be about 3,000 put to death. Nevertheless, some authors consider that the toll may have been higher, keeping in mind the data provided by Dedieu and García Cárcel for the tribunals of Toledo and Valencia, respectively, and estimate between 3,000 and 5,000 were executed.Data for executions for witchcraft: And see Witch trials in Early Modern Europe for more detail. Other authors disagree and estimate a max death toll between 1% and 5%, (depending on the time span used) combining all the processes the inquisition carried, both religious and non-religious ones. In either case, this is significantly lower than the Witch trials in Early Modern Europe#Numbers of executions, number of people executed exclusively Witch trials in Early Modern Europe, for witchcraft in other parts of Europe during about the same time span as the Spanish Inquisition (estimated at c. 40,000–60,000).

Modern historians have begun to study the documentary records of the Inquisition. The archives of the Suprema, today held by the National Historical Archive (Spain), National Historical Archive of Spain (Archivo Histórico Nacional), conserves the annual relations of all processes between 1540 and 1700. This material provides information for approximately 44,674 judgments. These 44,674 cases include 826 executions ''in persona'' and 778 ''in effigie'' (i.e. an effigy was burned). This material is far from being complete—for example, the tribunal of Cuenca is entirely omitted, because no ''relaciones de causas'' from this tribunal have been found, and significant gaps concern some other tribunals (e.g., Valladolid). Many more cases not reported to the Suprema are known from the other sources (i.e., no ''relaciones de causas'' from Cuenca have been found, but its original records have been preserved), but were not included in Contreras-Henningsen's statistics for the methodological reasons. William Monter estimates 1000 executions between 1530 and 1630 and 250 between 1630 and 1730.

The archives of the Suprema only provide information about processes prior to 1560. To study the processes themselves, it is necessary to examine the archives of the local tribunals, the majority of which have been lost to the devastation of war, the ravages of time or other events. Some archives have survived including those of Toledo, where 12,000 were judged for offences related to heresy, mainly minor "blasphemy", and those of Valencia. These indicate that the Inquisition was most active in the period between 1480 and 1530 and that during this period the percentage condemned to death was much more significant than in the years that followed. Modern estimates show approximately 2,000 executions ''in persona'' in the whole of Spain up to 1530.

García Cárcel estimates that the total number prosecuted by the Inquisition throughout its history was approximately 150,000; applying the percentages of executions that appeared in the trials of 1560–1700—about 2%—the approximate total would be about 3,000 put to death. Nevertheless, some authors consider that the toll may have been higher, keeping in mind the data provided by Dedieu and García Cárcel for the tribunals of Toledo and Valencia, respectively, and estimate between 3,000 and 5,000 were executed.Data for executions for witchcraft: And see Witch trials in Early Modern Europe for more detail. Other authors disagree and estimate a max death toll between 1% and 5%, (depending on the time span used) combining all the processes the inquisition carried, both religious and non-religious ones. In either case, this is significantly lower than the Witch trials in Early Modern Europe#Numbers of executions, number of people executed exclusively Witch trials in Early Modern Europe, for witchcraft in other parts of Europe during about the same time span as the Spanish Inquisition (estimated at c. 40,000–60,000).

Modern historians have begun to study the documentary records of the Inquisition. The archives of the Suprema, today held by the National Historical Archive (Spain), National Historical Archive of Spain (Archivo Histórico Nacional), conserves the annual relations of all processes between 1540 and 1700. This material provides information for approximately 44,674 judgments. These 44,674 cases include 826 executions ''in persona'' and 778 ''in effigie'' (i.e. an effigy was burned). This material is far from being complete—for example, the tribunal of Cuenca is entirely omitted, because no ''relaciones de causas'' from this tribunal have been found, and significant gaps concern some other tribunals (e.g., Valladolid). Many more cases not reported to the Suprema are known from the other sources (i.e., no ''relaciones de causas'' from Cuenca have been found, but its original records have been preserved), but were not included in Contreras-Henningsen's statistics for the methodological reasons. William Monter estimates 1000 executions between 1530 and 1630 and 250 between 1630 and 1730.

The archives of the Suprema only provide information about processes prior to 1560. To study the processes themselves, it is necessary to examine the archives of the local tribunals, the majority of which have been lost to the devastation of war, the ravages of time or other events. Some archives have survived including those of Toledo, where 12,000 were judged for offences related to heresy, mainly minor "blasphemy", and those of Valencia. These indicate that the Inquisition was most active in the period between 1480 and 1530 and that during this period the percentage condemned to death was much more significant than in the years that followed. Modern estimates show approximately 2,000 executions ''in persona'' in the whole of Spain up to 1530.

Statistics for the period 1540–1700

The statistics of Henningsen and Contreras are based entirely on ''relaciones de causas''. The number of years for which cases are documented varies for different tribunals. Data for the Aragonese Secretariat are probably complete, some small lacunae may concern only Valencia and possibly Sardinia and Cartagena, but the numbers for Castilian Secretariat—except Canaries and Galicia—should be considered as minimal due to gaps in the documentation. In some cases it is remarked that the number does not concern the whole period 1540–1700.''Autos de fe'' between 1701 and 1746

Table of sentences pronounced in the public ''autos de fe'' in Spain (excluding tribunals in Sicily, Sardinia and Latin America) between 1701 and 1746:Abuse of power

According to Toby Green, the great unchecked power given to inquisitors meant that they were "widely seen as above the law", and they sometimes had motives for imprisoning or executing alleged offenders that had nothing to do with punishing religious nonconformity. Green quotes a complaint by historian Manuel Barrios about one Inquisitor, Diego Rodriguez Lucero, who in Cordoba in 1506 burned to death the husbands of two women; he then kept the women as mistresses. According to Barrios:...the daughter of Diego Celemin was exceptionally beautiful, her parents and her husband did not want to give her to [Lucero], and so Lucero had the three of them burnt and now has a child by her, and he has kept for a long time in the Alcázar of Seville, alcazar as a mistress.Some writers disagree with Green. These authors do not necessarily deny the abuses of power, but classify them as politically instigated and comparable to those of any other law enforcement body of the period. Criticisms, usually indirect, have gone from the suspiciously sexual overtones or similarities of these accounts with unrelated older antisemitic accounts of kidnap and torture, to the clear proofs of control that the king had over the institution, to the sources used by Green, or just by reaching completely different conclusions.

Long-term economic effects

According to a 2021 study, "municipalities of Spain with a history of a stronger inquisitorial presence show lower economic performance, educational attainment, and trust today."Intrepretation

Within the context of medieval Europe, there are several hypotheses of what prompted the creation of the tribunal after La Convivencia, centuries of tolerance."Too Multi-Religious" hypothesis

The Spanish Inquisition is interpretable as a response to the multi-religious nature of Spanish society following the Reconquista, reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula from the Muslim Moors. The Reconquista did not result in the total expulsion of Muslims from Spain since they, along with Jews, were tolerated by the ruling Christian elite. Large cities, especially; Fritz Kobler, ''Letters of the Jews through the Ages'', London 1952, pp. 272–275; ; Solomon ibn Verga

''Shevaṭ Yehudah'' (The Sceptre of Judah)

Lvov 1846, p. 76 in PDF. From there, the violence spread to

The "Enforcement Across Borders" hypothesis

According to this hypothesis, the Inquisition was created to standardize various laws and the numerous jurisdictions Spain was divided into. It would be an administrative program analogous to the Santa Hermandad (the "Holy Brotherhood", ancestor to the Guardia Civil, a law enforcement body answering to the crown that prosecuted thieves and criminals across counties in a way local county authorities could not), an institution that would guarantee uniform prosecution of crimes against royal laws across all local jurisdictions. The unusual authority wielded by the king over the nobility in the Kingdom of Castile contributed to the kingdom's prosperity in Europe. This strong control kept the kingdom politically stable and prevented in-fighting that weakened other countries like England. Under the House of Trastámara, Trastámara dynasty, both kings of Castile and Aragon had lost power to the great nobles, who now formed dissenting and conspiratorial factions. Taxation and varying privileges differed from county to county, and powerful noble families constantly extorted the kings to attain further concessions, particularly in Aragon. The main goals of the reign of the Catholic Monarchs were to unite their two kingdoms and strengthen royal influence to guarantee stability. In pursuit of this, they sought to unify the laws of their realms further and reduce the power of the nobility in certain local areas. They attained this partially by raw military strength by creating a combined army between the two of them that could outmatch the military of most noble coalitions in the Peninsula. It was impossible to change the entire laws of both realms by force alone, and due to reasonable suspicion of one another, the monarchs kept their kingdoms separate during their lifetimes. The only way to unify both kingdoms and ensure that Isabella, Ferdinand, and their descendants maintained the power of both kingdoms without uniting them in life was to find or create an executive, legislative, and judicial arm directly under the Crown empowered to act in both kingdoms. This goal, the hypothesis goes, might have given birth to the Spanish Inquisition. The religious organization capable of overseeing this role was obvious. Catholicism was the only institution common to both kingdoms and the only one with enough popular support that the nobility could not easily attack it. Through the Spanish Inquisition, Isabella and Ferdinand created a personal police force and personal code of law that rested above the structure of their respective realms without altering or mixing them and could operate freely in both. As the Inquisition had the backing of both kingdoms, it would exist independent of both the nobility and local interests of either kingdom. According to this view, the prosecution of heretics would be secondary, or simply not considered different, from the prosecution of conspirators, traitors, or groups of any kind who planned to resist royal authority. Royal authority rested on the divine right and oaths of loyalty held before God, so the connection between religious deviation and political disloyalty would appear obvious. The disproportionately high representation of the nobility and high clergy among those investigated by the Inquisition supported this hypothesis, as well as the many administrative and civil crimes the Inquisition oversaw. The Inquisition prosecuted the counterfeiting of royal seals and currency, ensured the effective transmission of the orders of the kings, and verified the authenticity of official documents traveling through the kingdoms, from one kingdom to the other.The "Placate Europe" hypothesis

At a time in which most of Europe had already History of the Jews in the Middle Ages, expelled the Jews from the Christian kingdoms, the "dirty blood" of Spaniards was met with open suspicion and contempt. As the world became smaller and foreign relations became more relevant to stay in power, this foreign image of "being the seed of Jews and Moors" may have become a problem. In addition, the coup that allowed Isabella to take the throne from Joanna la Beltraneja, Joanna of Castile ("la Beltraneja") and the Catholic Monarchs to marry had estranged Castile from Portugal, its historical ally, and created the need for new relationships. Similarly, Aragon's ambitions lay in control of the Mediterranean and the defense against France. As their Catholic Monarchs, policy of royal marriages proved, the Catholic Monarchs were deeply concerned about France's growing power and expected to create strong dynastic alliances across Europe. In this scenario, the Iberian reputation of being too tolerant was a problem. Despite the prestige earned through the reconquest (''The "Ottoman Scare" hypothesis

The alleged discovery of Morisco plots to support a possible Ottoman invasion was a crucial factor in their decision to create the Inquisition. At this time, theRenaissance ideas and implementation

The creation of the Spanish Inquisition was consistent with the most important political philosophers of the Florentine School, with whom the kings were known to have contact (Francesco Guicciardini, Guicciardini, Pico della Mirandola, Machiavelli, Segni, Pitti, Nardi, Varchi, etc.) Both Guicciardini and Machiavelli defended the importance of centralization and unification to create a strong state capable of repelling foreign invasions and also warned of the dangers of excessive social uniformity to the creativity and innovation of a nation. Machiavelli considered piety and morals desirable for the subjects but not so much for the ruler, who should use them as a way to unify its population. He also warned of the nefarious influence of a corrupt church in the creation of a selfish population and middle nobility, which had fragmented the peninsula and made it unable to resist either France or Aragon. German philosophers at the time were spreading the importance of a vassal sharing the religion of their lord. The Inquisition may have just been the result of putting these ideas into practice. The use of religion as a unifying factor across a land that was allowed to stay diverse and maintain different laws in other respects, and the creation of the Inquisition to enforce laws across it, maintain said religious unity, and control the local elites were consistent with most of those teachings. Alternatively, the enforcement of Catholicism across the realm might indeed be the result of simple religious devotion by the monarchs. The recent scholarship on the expulsion of the Jews leans towards the belief of religious motivations being at the bottom of it. However, considering the reports on Ferdinand's political persona, that is unlikely the only reason. Machiavelli, among others, described Ferdinand as a man who didn't know the meaning of piety, but who made political use of it and would have achieved little if he had known it. He was Machiavelli's main inspiration while writing ''The Prince''.The "Keeping the Pope in Check" hypothesis

The hierarchy of the Catholic Church had made many attempts during the Middle Ages to take over Christian Spain politically, such as claiming the Church's ownership over all land reconquered from non-Christians (a claim that was rejected by Castile but accepted by Aragon and Portugal). In the past, the papacy had tried and partially succeeded in forcing the Mozarabic Rite out of Iberia. Its intervention had been pivotal for Albigensian Crusade, Aragon's loss of Rosellon. The Crusade of Aragon, meddling regarding Aragon's control over South Italy was even stronger historically. In their lifetime, the Catholic Monarchs had Carrillo de Acuña, problems with Pope Paul II, a fervent proponent of absolute authority for the church over the kings. Carrillo actively opposed them both and often used Spain's "mixed blood" as an excuse to intervene. The papacy and the monarchs of Europe had been involved in a Investiture controversy, rivalry for power throughout the high Middle Ages that Rome already won in other powerful kingdoms, like France. Since the legitimacy granted by the church was necessary for both monarchs, especially Isabella, to stay in power, the creation of the Spanish Inquisition may have been a way to concede to the Pope's demands and criticism regarding Spain's mixed religious heritage, while simultaneously ensuring that the Pope could hardly force the second Inquisition of his own and create a tool to control the power of the Roman Church in Spain. The Spanish Inquisition was unique at the time because it was not led by the Pope. Once the bull of creation was granted, the head of the Inquisition was the Monarch of Spain. It was in charge of enforcing the laws of the king regarding religion and other private-life matters, not of following orders from Rome, from which it was independent. This independence allowed the Inquisition to investigate, prosecute, and convict clergy for both corruption and treason of conspiracy against the crown (on the Pope's behalf, presumably) without the Pope's intervention. The Inquisition was, despite its title of "Holy", not necessarily formed by the clergy, and secular lawyers were equally welcome to it. If it was an attempt at keeping Rome out of Spain, it was an extremely successful and refined one. It was a bureaucratic body that had the nominal authority of the church and permission to prosecute members of the church, which the kings could not do, while answering only to the Spanish Crown. This did not prevent the Pope from having some influence on the decisions of Spanish monarchs, but it did force the influence to be through the kings, making direct influence very difficult.Other hypotheses