The Puffing Devil on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Richard Trevithick (13 April 1771 – 22 April 1833) was a British inventor and mining engineer. The son of a mining captain, and born in the mining heartland of

As his experience grew, he realised that improvements in

As his experience grew, he realised that improvements in

In 1802 the Coalbrookdale Company in

In 1802 the Coalbrookdale Company in

The ''Puffing Devil'' was unable to maintain sufficient steam pressure for long periods, and would have been of little practical use. He built another steam-powered road vehicle in 1803 dubbed the London Steam Carriage, which attracted much attention from the public and press that year when he drove it in London from

The ''Puffing Devil'' was unable to maintain sufficient steam pressure for long periods, and would have been of little practical use. He built another steam-powered road vehicle in 1803 dubbed the London Steam Carriage, which attracted much attention from the public and press that year when he drove it in London from

In 1802 Trevithick built one of his high-pressure steam engines to drive a

In 1802 Trevithick built one of his high-pressure steam engines to drive a

Trevithick Day

which is held annually on the last Saturday in April. The day is a community festival with steam engines from all over the UK attending. Towards the end of the day they parade through the streets of Camborne and steam past a statue of Richard Trevithick outside the Passmore Edwards building.

The Camborne ‘Trevithick Day’ Website

Cornwall Record Office Online Catalogue for Richard Trevithick

Contributions to the Biography of Richard Trevithick Richard Edmonds, 1859

Richard Trevithick steam engine 1805–06 in the Energy Hall, Science Museum, London

Trevithick Society

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Trevithick, Richard 1771 births 1833 deaths 18th-century English engineers 19th-century English engineers 18th-century British businesspeople 19th-century British businesspeople People from Illogan People of the Industrial Revolution Explorers from Cornwall Locomotive builders and designers British mining engineers

Cornwall

Cornwall (; or ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is also one of the Celtic nations and the homeland of the Cornish people. The county is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, ...

, Trevithick was immersed in mining and engineering from an early age. He was an early pioneer of steam-powered road

A road is a thoroughfare used primarily for movement of traffic. Roads differ from streets, whose primary use is local access. They also differ from stroads, which combine the features of streets and roads. Most modern roads are paved.

Th ...

and rail transport, and his most significant contributions were the development of the first high-pressure steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs Work (physics), mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a Cylinder (locomotive), cyl ...

and the first working railway steam locomotive

A steam locomotive is a locomotive that provides the force to move itself and other vehicles by means of the expansion of steam. It is fuelled by burning combustible material (usually coal, Fuel oil, oil or, rarely, Wood fuel, wood) to heat ...

. The world's first locomotive-hauled railway journey took place on 21 February 1804, when Trevithick's unnamed steam locomotive hauled a train along the tramway of the Penydarren Ironworks, in Merthyr Tydfil

Merthyr Tydfil () is the main town in Merthyr Tydfil County Borough, Wales, administered by Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council. It is about north of Cardiff. Often called just Merthyr, it is said to be named after Tydfil, daughter of K ...

, Wales.

Turning his interests abroad Trevithick also worked as a mining consultant in Peru

Peru, officially the Republic of Peru, is a country in western South America. It is bordered in the north by Ecuador and Colombia, in the east by Brazil, in the southeast by Bolivia, in the south by Chile, and in the south and west by the Pac ...

and later explored parts of Costa Rica

Costa Rica, officially the Republic of Costa Rica, is a country in Central America. It borders Nicaragua to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the northeast, Panama to the southeast, and the Pacific Ocean to the southwest, as well as Maritime bo ...

. Throughout his professional career he went through many ups and downs and at one point faced financial ruin, also suffering from the strong rivalry of many mining and steam engineers of the day. During the prime of his career he was a well-known and highly respected figure in mining and engineering, but near the end of his life he fell out of the public eye.

Trevithick was extremely strong and was a champion Cornish wrestler.Longhurst, Percy: ''Cornish Wrestling'', The Boy's Own Annual, Volume 52, 1930, p167-169.''Trevithick, Ricard'', Encyclopedia Britannica Vol XXIII, Maxwell Sommerville (Philadelphia) 1891, p589.''Cornish wrestling champion of 150 years ago'', Cornish Guardian, 17 March 1966, p10.

Childhood and early life

Richard Trevithick was born at Tregajorran (in the parish ofIllogan

Illogan (pronounced ''il'luggan'', ) is a village and civil parish in west Cornwall, England, United Kingdom, two miles (3 km) northwest of Redruth. The population of Illogan was 5,404 at the 2011 census. In the same year the population of ...

), between Camborne

Camborne (from Cornish language, Cornish ''Cambron'', "crooked hill") is a town in Cornwall, England. The population at the 2011 Census was 20,845. The northern edge of the parish includes a section of the South West Coast Path, Hell's Mouth, C ...

and Redruth

Redruth ( , ) is a town and civil parishes in Cornwall, civil parish in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. According to the 2011 census, the population of Redruth was 14,018 In the same year the population of the Camborne-Redruth urban area, ...

, in the heart of one of the rich mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid substance with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. (2011): Mi ...

-mining areas of Cornwall

Cornwall (; or ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is also one of the Celtic nations and the homeland of the Cornish people. The county is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, ...

. He was the youngest-but-one child and the only boy in a family of six children. He was very tall for the era at , as well as athletic and concentrated more on sport than schoolwork. Sent to the village school

One-room schoolhouses, or One-room schools, have been commonplace throughout rural portions of various countries, including Prussia, Norway, Sweden, the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Portugal, and Spa ...

at Camborne, he did not take much advantage of the education provided; one of his school masters described him as "a disobedient, slow, obstinate, spoiled boy, frequently absent and very inattentive". An exception was arithmetic

Arithmetic is an elementary branch of mathematics that deals with numerical operations like addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. In a wider sense, it also includes exponentiation, extraction of roots, and taking logarithms.

...

, for which he had an aptitude, though arriving at the correct answers by unconventional means.

Trevithick was the son of mine "captain" Richard Trevithick (1735–1797) and of miner's daughter Ann Teague (died 1810). As a child he would watch steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs Work (physics), mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a Cylinder (locomotive), cyl ...

s pump water from the deep tin

Tin is a chemical element; it has symbol Sn () and atomic number 50. A silvery-colored metal, tin is soft enough to be cut with little force, and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, a bar of tin makes a sound, the ...

and copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

mines in Cornwall. For a time he was a neighbour of William Murdoch

William Murdoch (sometimes spelled Murdock) (21 August 1754 – 15 November 1839) was a Scottish chemist, inventor, and mechanical engineer.

Murdoch was employed by the firm of Boulton & Watt and worked for them in Cornwall, as a steam engin ...

, the steam carriage pioneer, and would have been influenced by Murdoch’s experiments with steam-powered road locomotion.

Trevithick first went to work at the age of 19 at the East Stray Park Mine. He was enthusiastic and quickly gained the status of a consultant

A consultant (from "to deliberate") is a professional (also known as ''expert'', ''specialist'', see variations of meaning below) who provides advice or services in an area of specialization (generally to medium or large-size corporations). Cons ...

, unusual for such a young person. He was popular with the miners because of the respect they had for his father.

Marriage and family

In 1797 Trevithick married Jane Harvey ofHayle

Hayle (, "estuary") is a port town and civil parishes in England, civil parish in west Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is situated at the mouth of the Hayle River (which discharges into St Ives Bay) and is approximately northeast of ...

. They raised 6 children:

* Richard Trevithick (1798–1872)

* Anne Ellis (1800–1877)

* Elizabeth Banfield (1803–1870)

* John Harvey Trevithick (1807–1877)

* Francis Trevithick

Francis Trevithick (1812–1877), from Camborne, Cornwall, was one of the first locomotive engineers of the London and North Western Railway (LNWR).

Life

Born in 1812 as the son of Richard Trevithick, he began the study of civil engineering a ...

(1812–1877)

* Frederick Henry Trevithick (1816–1883)

Career

Jane's father, John Harvey, formerly a blacksmith from Carnhell Green, formed the localfoundry

A foundry is a factory that produces metal castings. Metals are cast into shapes by melting them into a liquid, pouring the metal into a mold, and removing the mold material after the metal has solidified as it cools. The most common metals pr ...

, Harveys of Hayle. His company became famous worldwide for building huge stationary "beam" engines for pumping water, usually from mines. Up to this time such steam engines were of the condensing or atmospheric type, originally invented by Thomas Newcomen

Thomas Newcomen (; February 1664 – 5 August 1729) was an English inventor, creator of the Newcomen atmospheric engine, atmospheric engine in 1712, Baptist lay preacher, preacher by calling and ironmonger by trade.

He was born in Dart ...

in 1712, which also became known as low-pressure engines. James Watt

James Watt (; 30 January 1736 (19 January 1736 OS) – 25 August 1819) was a Scottish inventor, mechanical engineer, and chemist who improved on Thomas Newcomen's 1712 Newcomen steam engine with his Watt steam engine in 1776, which was f ...

, on behalf of his partnership with Matthew Boulton

Matthew Boulton ( ; 3 September 172817 August 1809) was an English businessman, inventor, mechanical engineer, and silversmith. He was a business partner of the Scottish engineer James Watt. In the final quarter of the 18th century, the par ...

, held a number of patent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an sufficiency of disclosure, enabling discl ...

s for improving the efficiency of Newcomen's engine—including the "separate condenser patent", which proved the most contentious.

Trevithick became engineer at the Ding Dong Mine in 1797, and there (in conjunction with Edward Bull) he pioneered the use of high-pressure steam. He worked on building and modifying steam engines to avoid the royalties due to Watt on the separate condenser patent. Boulton & Watt served an injunction

An injunction is an equitable remedy in the form of a special court order compelling a party to do or refrain from doing certain acts. It was developed by the English courts of equity but its origins go back to Roman law and the equitable rem ...

on him at Ding Dong, and posted it "on the minestuffs" and "most likely on the door" of the Count (Account) House which, although now a ruin, is the only surviving building from Trevithick's time there.

He also experimented with the plunger-pole pump, a type of pump—with a beam engine—used widely in Cornwall's tin mines, in which he reversed the plunger to change it into a water-power engine.

High-pressure engine

As his experience grew, he realised that improvements in

As his experience grew, he realised that improvements in boiler

A boiler is a closed vessel in which fluid (generally water) is heated. The fluid does not necessarily boil. The heated or vaporized fluid exits the boiler for use in various processes or heating applications, including water heating, centra ...

technology now permitted the safe production of high-pressure steam, which could move a piston

A piston is a component of reciprocating engines, reciprocating pumps, gas compressors, hydraulic cylinders and pneumatic cylinders, among other similar mechanisms. It is the moving component that is contained by a cylinder (engine), cylinder a ...

in a steam engine on its own account, instead of using near-atmospheric pressure, in a condensing engine. He was not the first to think of so-called "strong steam" or steam of about . William Murdoch

William Murdoch (sometimes spelled Murdock) (21 August 1754 – 15 November 1839) was a Scottish chemist, inventor, and mechanical engineer.

Murdoch was employed by the firm of Boulton & Watt and worked for them in Cornwall, as a steam engin ...

had developed and demonstrated a model steam carriage in 1784 and demonstrated it to Trevithick at his request in 1794. In fact, Trevithick lived next door to Murdoch in Redruth in 1797 and 1798. Oliver Evans

Oliver Evans (September 13, 1755 – April 15, 1819) was an American inventor, engineer, and businessman born in rural Delaware and later rooted commercially in Philadelphia. He was one of the first Americans to build steam engines and an advo ...

in the U.S. had also concerned himself with the concept, but there is no indication that Trevithick knew of his ideas. Independently of this, Arthur Woolf

Arthur Woolf (1766, Camborne, Cornwall – 16 October 1837, Guernsey) was a Cornish engineer, most famous for inventing a high-pressure compound steam engine. In this way he made an outstanding contribution to the development and perfection ...

was experimenting with higher pressures whilst working as the Chief Engineer of the Griffin Brewery (proprietors Meux and Reid). This was an engine designed by Hornblower and Maberly, and the proprietors were looking to have the best steam engine in London. Around 1796, Woolf believed he could save substantial amounts of coal consumption.

According to his son Francis, Trevithick was the first to make high-pressure steam work in England in 1799, although other sources say he had invented his first high-pressure engine by 1797. Not only would a high-pressure steam engine eliminate the condenser, but it would allow the use of a smaller cylinder, saving space and weight. He reasoned that his engine could now be lighter, more compact, and small enough to carry its own weight even with a carriage attached (this did not use the ''expansion'' of the steam, so-called "expansive working" came later).

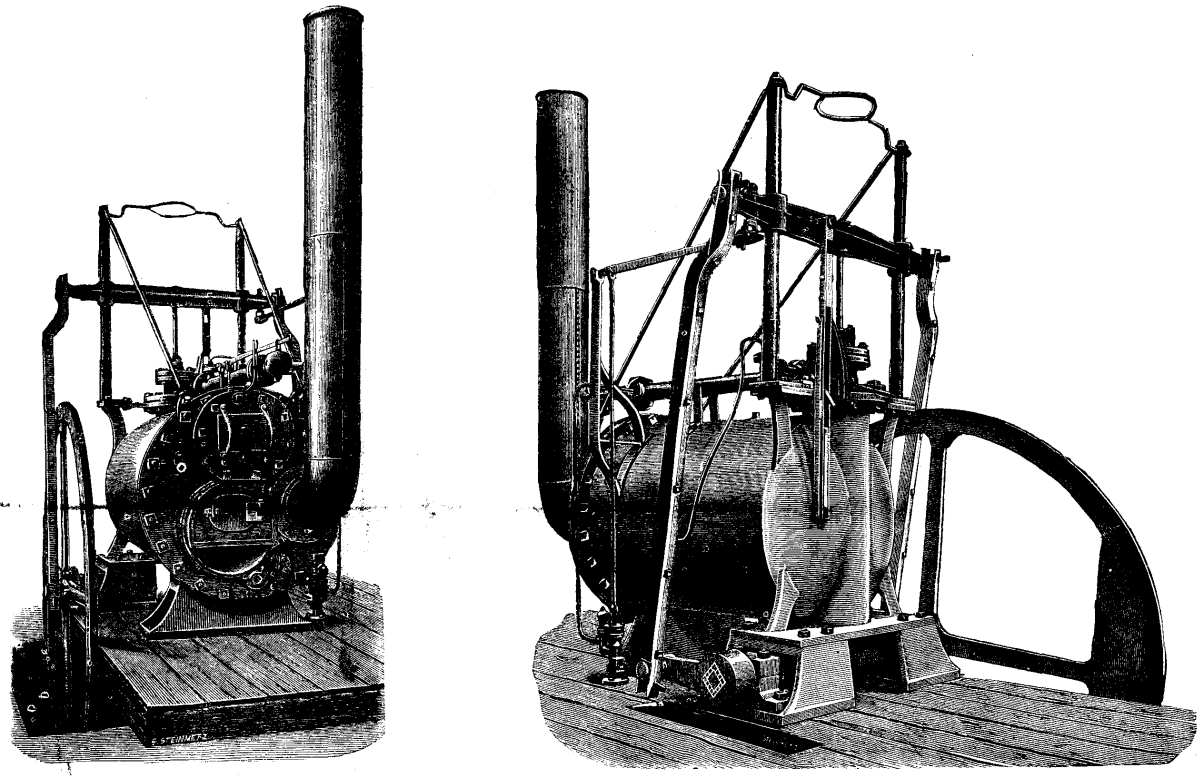

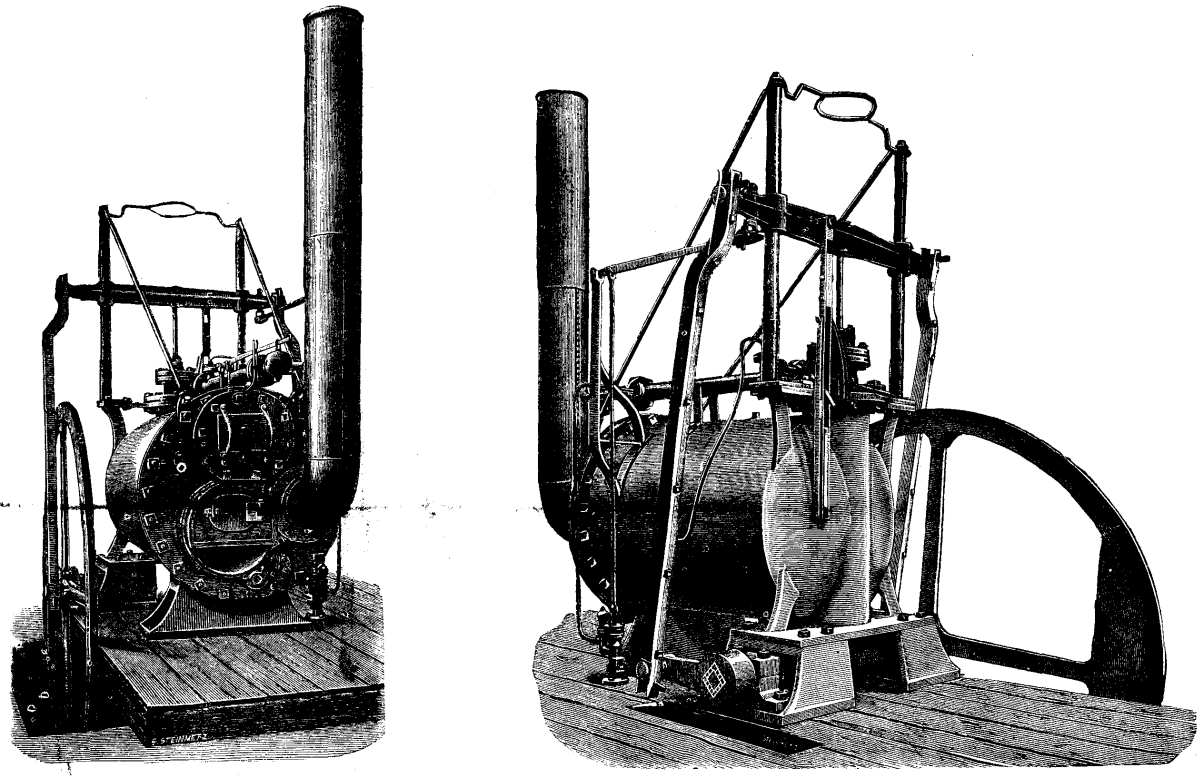

Early experiments

Trevithick began building his first models of high-pressure (meaning a few atmospheres) steam engines – one stationary one and then one attached to a road carriage. A double-acting cylinder was used, with steam distribution by means of afour-way valve

The four-way valve or four-way cock is a fluid control valve whose body has four ports.

One commonly used form—the rotary four way valve—has equally spaced ports around the valve chamber and a plug with two passages that connect pairs of ad ...

. Exhaust steam was vented via a vertical pipe or chimney

A chimney is an architectural ventilation structure made of masonry, clay or metal that isolates hot toxic exhaust gases or smoke produced by a boiler, stove, furnace, incinerator, or fireplace from human living areas. Chimneys are typical ...

straight into the atmosphere, thus avoiding a condenser and any possible infringements of Watt's patent. The linear

In mathematics, the term ''linear'' is used in two distinct senses for two different properties:

* linearity of a '' function'' (or '' mapping'');

* linearity of a '' polynomial''.

An example of a linear function is the function defined by f(x) ...

motion was directly converted into circular motion via a crank instead of using a more cumbersome beam.

''Puffing Devil''

Trevithick built a full-size steam road locomotive in 1801, on a site near present-day Fore Street in Camborne. (A steam wagon built in 1770 by Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot may have an earlier claim.) Trevithick named his carriage ''Puffing Devil'' and onChristmas Eve

Christmas Eve is the evening or entire day before Christmas, the festival commemorating nativity of Jesus, the birth of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus. Christmas Day is observance of Christmas by country, observed around the world, and Christma ...

that year, he demonstrated it by successfully carrying six passengers up Fore Street and then continuing on up Camborne Hill, from Camborne Cross, to the nearby village of Beacon

A beacon is an intentionally conspicuous device designed to attract attention to a specific location. A common example is the lighthouse, which draws attention to a fixed point that can be used to navigate around obstacles or into port. More mode ...

. His cousin and associate, Andrew Vivian

Andrew Vivian (1759–1842) was a British mechanical engineer, inventor, and mine captain of the Dolcoath mine in Cornwall, England.

In partnership with his cousin Richard Trevithick, the inventor of the "high pressure" steam engine, and the ...

, steered the machine. It inspired the popular Cornish folk song " Camborne Hill".

During further tests, Trevithick's locomotive broke down three days later after passing over a gully in the road. The vehicle was left under some shelter with the fire still burning whilst the operators retired to a nearby public house

A pub (short for public house) is in several countries a drinking establishment licensed to serve alcoholic drinks for consumption Licensing laws of the United Kingdom#On-licence, on the premises. The term first appeared in England in the ...

for a meal of roast goose and drinks. The boiler went dry, overheating the engine destroying it in a fire. Trevithick did not see this caused by a design flaw, but rather operator error.

In 1802 Trevithick took out a patent for his high-pressure steam engine. Rogers, Iron Road, pp. 40–44 To prove his ideas, he built a stationary engine at the Coalbrookdale

Coalbrookdale is a town in the Ironbridge Gorge and the Telford and Wrekin borough of Shropshire, England, containing a settlement of great significance in the history of iron ore smelting. It lies within the civil parish called The Gorge, Shro ...

Company's works in Shropshire

Shropshire (; abbreviated SalopAlso used officially as the name of the county from 1974–1980. The demonym for inhabitants of the county "Salopian" derives from this name.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West M ...

in 1802, forcing water to a measured height to measure the work done

In science, work is the energy transferred to or from an object via the application of force along a displacement. In its simplest form, for a constant force aligned with the direction of motion, the work equals the product of the force stren ...

. The engine ran at forty piston strokes a minute, with an unprecedented boiler pressure of .

Coalbrookdale Locomotive

In 1802 the Coalbrookdale Company in

In 1802 the Coalbrookdale Company in Shropshire

Shropshire (; abbreviated SalopAlso used officially as the name of the county from 1974–1980. The demonym for inhabitants of the county "Salopian" derives from this name.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West M ...

built a rail locomotive for him, but little is known about it, including whether or not it actually ran. The death of a company workman in an accident involving the engine is said to have caused the company to not proceed to running it on their existing railway. To date, the only known information about it comes from a drawing preserved at the Science Museum, London

The Science Museum is a major museum on Exhibition Road in South Kensington, London. It was founded in 1857 and is one of the city's major tourist attractions, attracting 3.3 million visitors annually in 2019.

Like other publicly funded ...

, together with a letter written by Trevithick to his friend Davies Giddy. The design incorporated a single horizontal cylinder

A cylinder () has traditionally been a three-dimensional solid, one of the most basic of curvilinear geometric shapes. In elementary geometry, it is considered a prism with a circle as its base.

A cylinder may also be defined as an infinite ...

enclosed in a return-flue boiler

A boiler is a closed vessel in which fluid (generally water) is heated. The fluid does not necessarily boil. The heated or vaporized fluid exits the boiler for use in various processes or heating applications, including water heating, centra ...

. A flywheel

A flywheel is a mechanical device that uses the conservation of angular momentum to store rotational energy, a form of kinetic energy proportional to the product of its moment of inertia and the square of its rotational speed. In particular, a ...

drove the wheels on one side through spur gears, and the axles were mounted directly on the boiler, with no frame. On the drawing, the piston-rod, guide-bars and cross-head are located directly above the firebox door, thus making the engine extremely dangerous to fire while moving. Furthermore, the first drawing by Daniel Shute indicates that the locomotive ran on a plateway

A plateway is an early kind of railway, tramway or wagonway, where the rails are made from cast iron. They were mainly used for about 50 years up to 1830, though some continued later.

Plateways consisted of L-shaped rails, where the flange ...

with a track gauge

In rail transport, track gauge is the distance between the two rails of a railway track. All vehicles on a rail network must have Wheelset (rail transport), wheelsets that are compatible with the track gauge. Since many different track gauges ...

of .

This drawing was used as the basis of all images and replicas of the later "Pen-y-darren" locomotive, as no plans for that locomotive survived.

London Steam Carriage

The ''Puffing Devil'' was unable to maintain sufficient steam pressure for long periods, and would have been of little practical use. He built another steam-powered road vehicle in 1803 dubbed the London Steam Carriage, which attracted much attention from the public and press that year when he drove it in London from

The ''Puffing Devil'' was unable to maintain sufficient steam pressure for long periods, and would have been of little practical use. He built another steam-powered road vehicle in 1803 dubbed the London Steam Carriage, which attracted much attention from the public and press that year when he drove it in London from Holborn

Holborn ( or ), an area in central London, covers the south-eastern part of the London Borough of Camden and a part (St Andrew Holborn (parish), St Andrew Holborn Below the Bars) of the Wards of the City of London, Ward of Farringdon Without i ...

to Paddington

Paddington is an area in the City of Westminster, in central London, England. A medieval parish then a metropolitan borough of the County of London, it was integrated with Westminster and Greater London in 1965. Paddington station, designed b ...

and back. It was uncomfortable for passengers and proved more expensive to run than a horse-drawn carriage, and was abandoned. In 1831, Trevithick gave evidence to a Parliamentary select committee on steam carriages.

Tragedy at Greenwich

Also in 1803, one of Trevithick's stationary pumping engines in use atGreenwich

Greenwich ( , , ) is an List of areas of London, area in south-east London, England, within the Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county of Greater London, east-south-east of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime hi ...

exploded, killing four men. Although Trevithick considered the explosion to be caused by careless operation rather than design error, the incident was heavily exploited by James Watt

James Watt (; 30 January 1736 (19 January 1736 OS) – 25 August 1819) was a Scottish inventor, mechanical engineer, and chemist who improved on Thomas Newcomen's 1712 Newcomen steam engine with his Watt steam engine in 1776, which was f ...

and Matthew Boulton

Matthew Boulton ( ; 3 September 172817 August 1809) was an English businessman, inventor, mechanical engineer, and silversmith. He was a business partner of the Scottish engineer James Watt. In the final quarter of the 18th century, the par ...

(competitors

Competition is a rivalry where two or more parties strive for a common goal which cannot be shared: where one's gain is the other's loss (an example of which is a zero-sum game). Competition can arise between entities such as organisms, indi ...

and promoters of low-pressure engines) who highlighted the perceived risks of using high-pressure steam.

Trevithick's response was to incorporate two safety valve

A safety valve is a valve that acts as a fail-safe. An example of safety valve is a pressure relief valve (PRV), which automatically releases a substance from a boiler, pressure vessel, or other system, when the pressure or temperature exceeds ...

s into future designs, only one of which could be adjusted by the operator. The adjustable valve comprised a disc covering a small hole at the top of the boiler above the water level in the steam chest. The force

In physics, a force is an influence that can cause an Physical object, object to change its velocity unless counterbalanced by other forces. In mechanics, force makes ideas like 'pushing' or 'pulling' mathematically precise. Because the Magnitu ...

exerted by the steam pressure

Pressure (symbol: ''p'' or ''P'') is the force applied perpendicular to the surface of an object per unit area over which that force is distributed. Gauge pressure (also spelled ''gage'' pressure)The preferred spelling varies by country and eve ...

was equalised by an opposite force created by a weight attached to a pivoted lever. The position of the weight on the lever was adjustable thus allowing the operator to set the maximum steam pressure. Trevithick also added a fusible plug of lead, positioned in the boiler just below the minimum safe water level. Under normal operation the water temperature could not exceed that of boiling

Boiling or ebullition is the rapid phase transition from liquid to gas or vapor, vapour; the reverse of boiling is condensation. Boiling occurs when a liquid is heated to its boiling point, so that the vapour pressure of the liquid is equal to ...

water and kept the lead below its melting point. If the water ran low, it exposed the lead plug, and the cooling effect of the water was lost. The temperature would then rise sufficiently to melt the lead, releasing steam into the fire, reducing the boiler pressure and providing an audible alarm in sufficient time for the operator to damp the fire, and let the boiler cool before damage could occur. He also introduced the hydraulic testing of boilers, and the use of a mercury manometer

Pressure measurement is the measurement of an applied force by a fluid (liquid or gas) on a surface. Pressure is typically measured in units of force per unit of surface area. Many techniques have been developed for the measurement of pressu ...

to indicate the pressure.

"Pen-y-Darren" locomotive

In 1802 Trevithick built one of his high-pressure steam engines to drive a

In 1802 Trevithick built one of his high-pressure steam engines to drive a hammer

A hammer is a tool, most often a hand tool, consisting of a weighted "head" fixed to a long handle that is swung to deliver an impact to a small area of an object. This can be, for example, to drive nail (fastener), nails into wood, to sh ...

at the Penydarren Ironworks in Merthyr Tydfil

Merthyr Tydfil () is the main town in Merthyr Tydfil County Borough, Wales, administered by Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council. It is about north of Cardiff. Often called just Merthyr, it is said to be named after Tydfil, daughter of K ...

, Mid Glamorgan. With the assistance of Rees Jones, an employee of the iron works, and under the supervision of Samuel Homfray, the proprietor, Trevithick mounted the engine on wheels and turned it into a locomotive. In 1803, Trevithick sold the patents for his locomotives to Samuel Homfray.

Homfray was so impressed with Trevithick's locomotive that he made a bet of 500 guineas

The guinea (; commonly abbreviated gn., or gns. in plural) was a coin, minted in Great Britain between 1663 and 1814, that contained approximately one-quarter of an ounce of gold. The name came from the Guinea region in West Africa, from where m ...

with another ironmaster, Richard Crawshay, that Trevithick's steam locomotive could haul ten ton

Ton is any of several units of measure of mass, volume or force. It has a long history and has acquired several meanings and uses.

As a unit of mass, ''ton'' can mean:

* the '' long ton'', which is

* the ''tonne'', also called the ''metric ...

s of iron along the Merthyr Tramroad

The Merthyr Tramroad (sometimes referred to as the Penydarren Tramroad due to its use by Trevithick's locomotive, built at the ironworks) was a line that opened in 1802, connecting the private lines belonging to the Dowlais and Penydarren Ironw ...

from Penydarren

: ''For Trevithick's Pen-y-darren locomotive, see Richard Trevithick#"Pen-y-Darren" locomotive, Richard Trevithick.''

Penydarren is a Community (Wales), community and electoral ward in Merthyr Tydfil County Borough in Wales.

Description

The area ...

() to Abercynon

Abercynon () is a village and community (Wales), community (and electoral ward) in the Cynon Valley within the unitary authority of Rhondda Cynon Taf, Wales. The community comprises the village and the districts of Carnetown and Grovers Field to ...

(), a distance of . On 21 February 1804, amid great interest from the public, it successfully carried 10 tons of iron, five wagons and 70 men the full distance in 4 hours and 5 minutes, at an average speed of approximately . As well as Homfray, Crawshay and the passengers, other witnesses included Mr. Giddy, a respected patron of Trevithick, and an "engineer from the Government". The engineer from the government was probably a safety inspector, who would have been particularly interested in the boiler's ability to withstand high steam pressures.

The configuration of the Pen-y-Darren engine differed from the Coalbrookdale engine. The cylinder was moved to the other end of the boiler so that the fire door was out of the way of the moving parts, which involved putting the crankshaft at the chimney end. The locomotive comprised a boiler

A boiler is a closed vessel in which fluid (generally water) is heated. The fluid does not necessarily boil. The heated or vaporized fluid exits the boiler for use in various processes or heating applications, including water heating, centra ...

with a single return flue mounted on a four-wheel frame. At one end, a single cylinder

A cylinder () has traditionally been a three-dimensional solid, one of the most basic of curvilinear geometric shapes. In elementary geometry, it is considered a prism with a circle as its base.

A cylinder may also be defined as an infinite ...

with very long stroke was mounted partly in the boiler, and a piston rod crosshead ran out along a slidebar. There was only one cylinder, which was coupled to a large flywheel

A flywheel is a mechanical device that uses the conservation of angular momentum to store rotational energy, a form of kinetic energy proportional to the product of its moment of inertia and the square of its rotational speed. In particular, a ...

mounted on one side. The rotational inertia

The moment of inertia, otherwise known as the mass moment of inertia, angular/rotational mass, second moment of mass, or most accurately, rotational inertia, of a rigid body is defined relatively to a rotational axis. It is the ratio between ...

of the flywheel would even out the movement that was transmitted to a central cog-wheel that in turn was connected to the driving wheels. It used a high-pressure cylinder without a condenser. The exhaust steam was sent up the chimney, which assisted the draught through the fire, further increasing the engine's efficiency.

Despite heavy scepticism it had been shown that, provided that the gradient

In vector calculus, the gradient of a scalar-valued differentiable function f of several variables is the vector field (or vector-valued function) \nabla f whose value at a point p gives the direction and the rate of fastest increase. The g ...

was sufficiently gentle, it was possible to successfully haul heavy carriages along a smooth iron road using just the adhesive weight of a suitably heavy and powerful steam locomotive. Trevithick's example was likely the first to do so; Kirby, Engineering in History, pp. 274–275 however, the locomotive broke some of the tramroad's short cast iron plates because they were only meant to support the lighter axle load of horse-drawn wagons. Consequently, the tramroad returned to horse power after the initial test run. The engine was placed on blocks and reverted to its original stationary job of driving hammers.

A full-scale working reconstruction of the Pen-y-darren locomotive was commissioned in 1981 and delivered to the Welsh Industrial and Maritime Museum in Cardiff. When that closed, the locomotive was moved to the National Waterfront Museum in Swansea. Several times a year, it is run on a length of railway outside the museum.

"Newcastle" locomotive

Christopher Blackett, proprietor of theWylam

Wylam is a village and civil parish in the county of Northumberland, England. It is located about west of Newcastle upon Tyne.

It is famous for the being the birthplace of George Stephenson, one of the early railway pioneers. George Stephen ...

colliery near Newcastle, heard of the success in Wales and wrote to Trevithick asking for locomotive designs. These were sent to Trevithick's agent John Whitfield at Gateshead, who in 1804 built what was likely the first locomotive to have flanged wheels. Blackett used wooden rails for his tramway, and once again Trevithick's machine was too heavy for its track.

''Catch Me Who Can''

In 1808 Trevithick publicised his steam railway locomotive expertise by building a new locomotive called '' Catch Me Who Can'', built for him by John Hazledine and John Urpeth Rastrick atBridgnorth

Bridgnorth is a market town and civil parish in Shropshire, England. The River Severn splits it into High Town and Low Town, the upper town on the right bank and the lower on the left bank of the River Severn. The population at the United Kingd ...

in Shropshire

Shropshire (; abbreviated SalopAlso used officially as the name of the county from 1974–1980. The demonym for inhabitants of the county "Salopian" derives from this name.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West M ...

, and named by Davies Giddy's daughter. The configuration differed from the previous locomotives in that the cylinder was mounted vertically and drove a pair of wheels directly without a flywheel or gearing. This was probably Trevithick's fourth locomotive, after those used at Coalbrookdale, Pen-y-darren ironworks, and the Wylam colliery. He ran it on a circular track just south of the present-day Euston Square tube station

Euston Square () is a London Underground station at the corner of Euston Road and Gower Street (London), Gower Street, just north of University College London – its main (south) entrance faces the tower of University College Hospital. The ...

in London. The site in Bloomsbury

Bloomsbury is a district in the West End of London, part of the London Borough of Camden in England. It is considered a fashionable residential area, and is the location of numerous cultural institution, cultural, intellectual, and educational ...

has recently been identified archaeologically as that occupied by the Chadwick Building, part of University College London

University College London (Trade name, branded as UCL) is a Public university, public research university in London, England. It is a Member institutions of the University of London, member institution of the Federal university, federal Uni ...

.

Admission to the "steam circus" was one shilling

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currency, currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 1 ...

including a ride and was intended to show that rail travel was faster than by horse. This venture also suffered from weak tracks and public interest was limited.

Trevithick was disappointed by the response and designed no more railway locomotives. It was not until 1812 that twin-cylinder steam locomotives, built by Matthew Murray

Matthew Murray (1765 – 20 February 1826) was an English steam engine and machine tool manufacturer, who designed and built the first commercially viable steam locomotive, the twin-cylinder ''Salamanca'' in 1812. He was an innovative design ...

in Holbeck

Holbeck is an inner city area of Leeds, West Yorkshire, England. It begins on the southern edge of Leeds city centre and mainly lies in the LS11 postcode district. The M1 and M621 motorways used to end/begin in Holbeck. Now the M621 is t ...

, Leeds

Leeds is a city in West Yorkshire, England. It is the largest settlement in Yorkshire and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds Metropolitan Borough, which is the second most populous district in the United Kingdom. It is built aro ...

successfully started replacing horses for hauling coal wagons on the edge railed, rack and pinion Middleton Railway

The Middleton Railway is the world's oldest continuously working railway, situated in Leeds, West Yorkshire, England. It was founded in 1758 and is now a heritage railway, run by volunteers from The Middleton Railway Trust Ltd. since 1960.

The ...

from Middleton colliery to Leeds

Leeds is a city in West Yorkshire, England. It is the largest settlement in Yorkshire and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds Metropolitan Borough, which is the second most populous district in the United Kingdom. It is built aro ...

, West Yorkshire

West Yorkshire is a Metropolitan counties of England, metropolitan and Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the Yorkshire and the Humber region of England. It borders North Yorkshire to the north and east, South Yorkshire and De ...

.

Engineering projects

Thames tunnel

Robert Vazie, another Cornish engineer, was selected by the Thames Archway Company in 1805 to drive a tunnel under theRiver Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, s ...

at Rotherhithe

Rotherhithe ( ) is a district of South London, England, and part of the London Borough of Southwark. It is on a peninsula on the south bank of the Thames, facing Wapping, Shadwell and Limehouse on the north bank, with the Isle of Dogs to the ea ...

. Vazie encountered serious problems with water influx, and had got no further than sinking the end shafts when the directors called in Trevithick for consultation. The directors agreed to pay Trevithick £1000 (the equivalent of £ in ) if he could successfully complete the tunnel, a length of . In August 1807, he began driving a small pilot tunnel or driftway high tapering from at the top to at the bottom.

By 23 December, after it had progressed , progress was delayed after a sudden inrush of water; and only one month later on 26 January 1808, at , a more serious inrush occurred. The tunnel was flooded; Trevithick, being the last to leave, was nearly drowned. Clay was dumped on the river bed to seal the hole, and the tunnel was drained, but mining was now more difficult. Progress stalled, and a few of the directors attempted to discredit Trevithick, but the quality of his work was eventually upheld by two colliery

Coal mining is the process of extracting coal from the ground or from a mine. Coal is valued for its energy content and since the 1880s has been widely used to generate electricity. Steel and cement industries use coal as a fuel for extra ...

engineers from the North of England. Despite suggesting various building techniques to complete the project, including a submerged cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content of more than 2% and silicon content around 1–3%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloying elements determine the form in which its car ...

tube

Tube or tubes may refer to:

* ''Tube'' (2003 film), a 2003 Korean film

* "Tubes" (Peter Dale), performer on the Soccer AM television show

* Tube (band), a Japanese rock band

* Tube & Berger, the alias of dance/electronica producers Arndt Rör ...

, Trevithick's links with the company ceased and the project was never completed.

Completion

The first successful tunnel under the Thames was started by SirMarc Isambard Brunel

Sir Marc Isambard Brunel (, ; 25 April 1769 – 12 December 1849) was a French-American engineer active in the United States and Britain, most famous for the civil engineering work he did in the latter. He is known for having overseen the pr ...

in 1823, upstream, assisted by his son Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel ( ; 9 April 1806 – 15 September 1859) was an English civil engineer and mechanical engineer who is considered "one of the most ingenious and prolific figures in engineering history", "one of the 19th-century engi ...

(who also nearly died in a tunnel collapse). Marc Brunel finally completed it in 1843, the delays being due to problems with funding.

Trevithick's suggestion of a submerged tube approach was successfully implemented for the first time across the Detroit River

The Detroit River is an List of international river borders, international river in North America. The river, which forms part of the border between the U.S. state of Michigan and the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Ont ...

between Michigan

Michigan ( ) is a peninsular U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest, Upper Midwestern United States. It shares water and land boundaries with Minnesota to the northwest, Wisconsin to the west, ...

in the United States and Ontario

Ontario is the southernmost Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada. Located in Central Canada, Ontario is the Population of Canada by province and territory, country's most populous province. As of the 2021 Canadian census, it ...

in Canada with the construction of the Michigan Central Railway Tunnel

The Michigan Central Railway Tunnel is a railroad tunnel under the Detroit River connecting Detroit, Michigan, in the United States with Windsor, Ontario, in Canada. The U.S. entrance is south of Porter and Vermont streets near Rosa Parks Bouleva ...

, under the engineering supervision of The New York Central Railway's engineering vice president, William J Wilgus. Construction began in 1903 and was completed in 1910. The Detroit–Windsor Tunnel

The Detroit–Windsor region is an international transborder agglomeration named for the American city of Detroit, Michigan, the Canadian city of Windsor, Ontario, and the Detroit River, which separates them. The Detroit–Windsor area acts as a ...

which was completed in 1930 for automotive traffic, and the tunnel under the Hong Kong Harbour were also submerged-tube designs.

Return to London

Trevithick went on to research other projects to exploit his high-pressure steam engines: boringbrass

Brass is an alloy of copper and zinc, in proportions which can be varied to achieve different colours and mechanical, electrical, acoustic and chemical properties, but copper typically has the larger proportion, generally copper and zinc. I ...

for cannon

A cannon is a large-caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder during th ...

manufacture, stone

In geology, rock (or stone) is any naturally occurring solid mass or aggregate of minerals or mineraloid matter. It is categorized by the minerals included, its Chemical compound, chemical composition, and the way in which it is formed. Rocks ...

crushing, rolling mills, forge hammers, blast furnace

A blast furnace is a type of metallurgical furnace used for smelting to produce industrial metals, generally pig iron, but also others such as lead or copper. ''Blast'' refers to the combustion air being supplied above atmospheric pressure.

In a ...

blowers as well as the traditional mining applications. He also built a barge

A barge is typically a flat-bottomed boat, flat-bottomed vessel which does not have its own means of mechanical propulsion. Original use was on inland waterways, while modern use is on both inland and ocean, marine water environments. The firs ...

powered by paddle wheels and several dredge

Dredging is the excavation of material from a water environment. Possible reasons for dredging include improving existing water features; reshaping land and water features to alter drainage, navigability, and commercial use; constructing ...

rs.

Trevithick saw opportunities in London and persuaded his wife and four children reluctantly to join him in 1808 for two and a half years lodging first in Rotherhithe

Rotherhithe ( ) is a district of South London, England, and part of the London Borough of Southwark. It is on a peninsula on the south bank of the Thames, facing Wapping, Shadwell and Limehouse on the north bank, with the Isle of Dogs to the ea ...

and then in Limehouse

Limehouse is a district in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets in East London. It is east of Charing Cross, on the northern bank of the River Thames. Its proximity to the river has given it a strong maritime character, which it retains throu ...

.

Nautical projects

In 1808 Trevithick entered a partnership with Robert Dickinson (businessman), a West India merchant. Dickinson supported several of Trevithick's patents. The first of these was the ''Nautical Labourer''; a steam tug with a floating crane propelled by paddle wheels. However, it did not meet the fire regulations for the docks, and the Society of Coal Whippers, worried about losing their livelihood, even threatened the life of Trevithick. Another patent was for the installation of iron tanks in ships for storage of cargo and water instead of in woodencasks

A barrel or cask is a hollow cylindrical container with a bulging center, longer than it is wide. They are traditionally made of wooden staves and bound by wooden or metal hoops. The word vat is often used for large containers for liquids ...

. A small works was set up at Limehouse

Limehouse is a district in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets in East London. It is east of Charing Cross, on the northern bank of the River Thames. Its proximity to the river has given it a strong maritime character, which it retains throu ...

to manufacture them, employing three men. The tanks were also used to raise sunken wrecks by placing them under the wreck and creating buoyancy

Buoyancy (), or upthrust, is the force exerted by a fluid opposing the weight of a partially or fully immersed object (which may be also be a parcel of fluid). In a column of fluid, pressure increases with depth as a result of the weight of t ...

by pumping them full of air. In 1810 a wreck near Margate

Margate is a seaside resort, seaside town in the Thanet District of Kent, England. It is located on the north coast of Kent and covers an area of long, north-east of Canterbury and includes Cliftonville, Garlinge, Palm Bay, UK, Palm Bay and W ...

was raised in this way but there was a dispute over payment and Trevithick was driven to cut the lashings loose and let it sink again.

In 1809, Trevithick worked on various ideas on improvements for ships: iron floating docks, iron ships, telescopic iron masts, improved ship structures, iron buoys and using heat from the ships boilers for cooking.

Illness, financial difficulties and return to Cornwall

In May 1810 Trevithick caughttyphoid

Typhoid fever, also known simply as typhoid, is a disease caused by ''Salmonella enterica'' serotype Typhi bacteria, also called ''Salmonella'' Typhi. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often ther ...

and nearly died. By September, he had recovered sufficiently to travel back to Cornwall by ship, and in February 1811 he and Dickinson were declared bankrupt

Bankruptcy is a legal process through which people or other entities who cannot repay debts to creditors may seek relief from some or all of their debts. In most jurisdictions, bankruptcy is imposed by a court order, often initiated by the de ...

. They were not discharged until 1814, Trevithick having paid off most of the partnership debts from his own funds.

Cornish boiler and engine

In about 1812 Trevithick designed the ‘ Cornish boiler’. These were horizontal, cylindrical boilers with a single internal fire tube or flue passing horizontally through the middle. Hot exhaust gases from the fire passed through the flue thus increasing the surface area heating the water and improving efficiency. These types were installed in the Boulton and Watt pumping engines at Dolcoath and more than doubled their efficiency. Again in 1812, he installed a new 'high-pressure' experimental condensing steam engine at Wheal Prosper. This became known as theCornish engine

A Cornish engine is a type of steam engine developed in Cornwall, England, mainly for pumping water from a mine. It is a form of beam engine that uses steam at a higher pressure than the earlier engines designed by James Watt. The engines were ...

, and was the most efficient in the world at that time. Other Cornish engineers contributed to its development but Trevithick's work was predominant. In the same year he installed another high-pressure engine, though non-condensing, in a threshing

Threshing or thrashing is the process of loosening the edible part of grain (or other crop) from the straw to which it is attached. It is the step in grain preparation after reaping. Threshing does not remove the bran from the grain.

History of ...

machine at the Trewithen Estate, a farm in Probus, Cornwall

Probus ('' Cornish: Lannbrobus'') is a civil parish and village in Cornwall, England, in the United Kingdom. It has the tallest church tower in Cornwall. The tower is high, and richly decorated with carvings. The place name originates from the c ...

. It was very successful and proved to be cheaper to run than the horses it replaced. In use for 70 years, it was then retired to an exhibit at the Science Museum

A science museum is a museum devoted primarily to science. Older science museums tended to concentrate on static displays of objects related to natural history, paleontology, geology, Industry (manufacturing), industry and Outline of industrial ...

. In 2023, the owners of the Trewithen Estate planned to redevelop their farm, which will also involve returning the historic Trevithick steam engine to its original location within the farm.

Recoil engine

In one of Trevithick's more unusual projects, he attempted to build a 'recoil engine' similar to theaeolipile

An aeolipile, aeolipyle, or eolipile, from the Greek "Αἰόλου πύλη," , also known as a Hero's (or Heron's) engine, is a simple, bladeless radial turbine, radial steam turbine which spins when the central water container is heated. Torq ...

described by Hero of Alexandria

Hero of Alexandria (; , , also known as Heron of Alexandria ; probably 1st or 2nd century AD) was a Greek mathematician and engineer who was active in Alexandria in Egypt during the Roman era. He has been described as the greatest experimental ...

in about AD 50. Trevithick's engine comprised a boiler feeding a hollow axle

An axle or axletree is a central shaft for a rotation, rotating wheel and axle, wheel or gear. On wheeled vehicles, the axle may be fixed to the wheels, rotating with them, or fixed to the vehicle, with the wheels rotating around the axle. In ...

to route the steam to a catherine wheel with two fine- bore steam jets on its circumference. The first wheel was in diameter and a later attempt was in diameter. To get any usable torque

In physics and mechanics, torque is the rotational analogue of linear force. It is also referred to as the moment of force (also abbreviated to moment). The symbol for torque is typically \boldsymbol\tau, the lowercase Greek letter ''tau''. Wh ...

, steam had to issue from the nozzles at a very high velocity

Velocity is a measurement of speed in a certain direction of motion. It is a fundamental concept in kinematics, the branch of classical mechanics that describes the motion of physical objects. Velocity is a vector (geometry), vector Physical q ...

and in such large volume that it proved not to operate with adequate efficiency. Today this would be recognised as a reaction turbine.

South America

Draining the Peruvian silver mines

In 1811 draining water from the richsilver

Silver is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ag () and atomic number 47. A soft, whitish-gray, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical conductivity, thermal conductivity, and reflectivity of any metal. ...

mines of Cerro de Pasco

Cerro de Pasco is a city in central Peru, located at the top of the Andean Mountains. It is the capital of both the Pasco Province and the Department of Pasco, and an important mining center of silver, copper, zinc and lead. At an elevation of ...

in Peru

Peru, officially the Republic of Peru, is a country in western South America. It is bordered in the north by Ecuador and Colombia, in the east by Brazil, in the southeast by Bolivia, in the south by Chile, and in the south and west by the Pac ...

at an altitude of posed serious problems for the man in charge, Francisco Uville. The low-pressure condensing engines by Boulton and Watt developed so little power as to be useless at this altitude, and they could not be dismantled into sufficiently small pieces to be transported there along mule

The mule is a domestic equine hybrid between a donkey, and a horse. It is the offspring of a male donkey (a jack) and a female horse (a mare). The horse and the donkey are different species, with different numbers of chromosomes; of the two ...

tracks. Uville was sent to England to investigate using Trevithick's high-pressure steam engine. He bought one for 20 guineas, transported it back and found it to work quite satisfactorily. In 1813 Uville set sail again for England and, having fallen ill on the way, broke his journey via Jamaica

Jamaica is an island country in the Caribbean Sea and the West Indies. At , it is the third-largest island—after Cuba and Hispaniola—of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean. Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, west of Hispaniola (the is ...

. When he had recovered he boarded the Falmouth packet ship

Packet boats were medium-sized boats designed mainly for domestic mail and freight transport in European countries and in North American rivers and canals. Eventually including basic passenger accommodation, they were used extensively during t ...

'Fox' coincidentally with one of Trevithick's cousins on board the same vessel. Trevithick's home was just a few miles from Falmouth so Uville was able to meet him and tell him about the project.

Trevithick leaves for South America

On 20 October 1816 Trevithick leftPenzance

Penzance ( ; ) is a town, civil parish and port in the Penwith district of Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is the westernmost major town in Cornwall and is about west-southwest of Plymouth and west-southwest of London. Situated in the ...

on the whaler

A whaler or whaling ship is a specialized vessel, designed or adapted for whaling: the catching or processing of whales.

Terminology

The term ''whaler'' is mostly historic. A handful of nations continue with industrial whaling, and one, Jap ...

ship ''Asp'' accompanied by a lawyer named Page and a boilermaker bound for Peru. He was received by Uville with honour initially but relations soon broke down and Trevithick left in disgust at the accusations directed at him. He travelled widely in Peru acting as a consultant on mining methods. The government granted him certain mining rights and he found mining areas, but did not have the funds to develop them, with the exception of a copper and silver mine at Caxatambo. After a time serving in the army of Simon Bolivar he returned to Caxatambo but due to the unsettled state of the country and presence of the Spanish army he was forced to leave the area and abandon £5,000 worth of ore ready to ship. Uville died in 1818 and Trevithick soon returned to Cerro de Pasco to continue mining. However, the war of liberation denied him several objectives. Meanwhile, back in England, he was accused of neglecting his wife Jane and family in Cornwall.

Exploring the isthmus of Costa Rica on foot

After leaving Cerro de Pasco, Trevithick passed throughEcuador

Ecuador, officially the Republic of Ecuador, is a country in northwestern South America, bordered by Colombia on the north, Peru on the east and south, and the Pacific Ocean on the west. It also includes the Galápagos Province which contain ...

on his way to Bogotá

Bogotá (, also , , ), officially Bogotá, Distrito Capital, abbreviated Bogotá, D.C., and formerly known as Santa Fe de Bogotá (; ) during the Spanish Imperial period and between 1991 and 2000, is the capital city, capital and largest city ...

in Colombia

Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country primarily located in South America with Insular region of Colombia, insular regions in North America. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Caribbean Sea to the north, Venezuel ...

. He arrived in Costa Rica

Costa Rica, officially the Republic of Costa Rica, is a country in Central America. It borders Nicaragua to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the northeast, Panama to the southeast, and the Pacific Ocean to the southwest, as well as Maritime bo ...

in 1822 hoping to develop mining machinery. He spent time looking for a practical route to transport ore and equipment, settling on using the San Juan River, the Sarapiqui River, and then a railway to cover the remaining distance. In a biography his son wrote that Trevithick had in mind a steam-driven railway and not mule-driven.

The initial party comprised Trevithick, Scottish mining projector James Gerard, two schoolboys: José Maria Montealegre (a future president of Costa Rica) and his brother Mariano, whom Gerard intended to enrol at a small boarding school at Lauderdale House

Lauderdale House is an historic house, now run as an arts and education centre, based in Waterlow Park, Highgate in north London, England.

History

Lauderdale House was one of the finest English country house, country houses in Highgate and was ...

in Highgate

Highgate is a suburban area of N postcode area, north London in the London Borough of Camden, London Boroughs of Camden, London Borough of Islington, Islington and London Borough of Haringey, Haringey. The area is at the north-eastern corner ...

(where Trevithick later made his temporary London home), and seven natives, three of whom returned home after guiding them through the first part of their journey. The journey was treacherous – one of the party was drowned in a raging torrent and Trevithick was nearly killed on at least two occasions. In the first he was saved from drowning by Gerard, and in the second he was nearly devoured by an alligator

An alligator, or colloquially gator, is a large reptile in the genus ''Alligator'' of the Family (biology), family Alligatoridae in the Order (biology), order Crocodilia. The two Extant taxon, extant species are the American alligator (''A. mis ...

following a dispute with a local man whom he had in some way offended. Still in the company of Gerard, he made his way to Cartagena where he chanced to meet Robert Stephenson

Robert Stephenson , (honoris causa, Hon. causa) (16 October 1803 – 12 October 1859) was an English civil engineer and designer of locomotives. The only son of George Stephenson, the "Father of Railways", he built on the achievements of hi ...

who was himself on his way home from Colombia, following a failed three-year mining venture. It had been many years since they last met (when Stephenson was just a baby), and the two men were judged by witnesses to their meeting to have little in common. Despite this Stephenson gave Trevithick £50 to help his passage home. Whilst Stephenson and Gerard booked passage via New York, Trevithick took ship direct to Falmouth, arriving there in October 1827 with few possessions other than the clothes he was wearing. He never returned to Costa Rica.

Later projects

Taking encouragement from earlier inventors who had achieved some successes with similar endeavours, Trevithick petitioned Parliament for a grant, but he was unsuccessful in acquiring one. In 1829 he built a closed cycle steam engine followed by a vertical tubular boiler. In 1830 he invented an early form of storage roomheater

Heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC ) is the use of various technologies to control the temperature, humidity, and purity of the air in an enclosed space. Its goal is to provide thermal comfort and acceptable indoor air quality. ...

. It comprised a small fire tube boiler with a detachable flue which could be heated either outside or indoors with the flue connected to a chimney. Once hot the hot water container could be wheeled to where heat was required and the issuing heat could be altered using adjustable doors.

To commemorate the passing of the Reform Bill in 1832 he designed a massive column to be high, being in diameter at the base tapering to at the top where a statue of a horse would have been mounted. It was to be made of 1500 10-foot-square (3 m) pieces of cast iron and would have weighed . There was substantial public interest in the proposal, but it was never built.

Final project

About the same time he was invited to do some development work on an engine of a new vessel at Dartford by John Hall, the founder of J & E Hall Limited. The work involved a reaction turbine for which Trevithick earned £1200. He lodged at The Bull hotel in the High Street,Dartford

Dartford is the principal town in the Borough of Dartford, Kent, England. It is located south-east of Central London and

is situated adjacent to the London Borough of Bexley to its west. To its north, across the Thames Estuary, is Thurrock in ...

, Kent

Kent is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Essex across the Thames Estuary to the north, the Strait of Dover to the south-east, East Sussex to the south-west, Surrey to the west, and Gr ...

.

Death

After he had been working inDartford

Dartford is the principal town in the Borough of Dartford, Kent, England. It is located south-east of Central London and

is situated adjacent to the London Borough of Bexley to its west. To its north, across the Thames Estuary, is Thurrock in ...

for about a year, Trevithick was taken ill with pneumonia

Pneumonia is an Inflammation, inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as Pulmonary alveolus, alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of Cough#Classification, productive or dry cough, ches ...

and had to retire to bed at the Bull Hotel, where he was lodging at the time. Following a week's confinement in bed he died on the morning of 22 April 1833. He was penniless, and no relatives or friends had attended his bedside during his illness. His colleagues at Hall's works made a collection for his funeral expenses and acted as bearers. They also paid a night watchman to guard his grave at night to deter grave robbers, as body snatching

Body snatching is the illicit removal of corpses from graves, morgues, and other burial sites. Body snatching is distinct from the act of grave robbery as grave robbing does not explicitly involve the removal of the corpse, but rather theft from t ...

was common at that time.

Trevithick was buried in an unmarked grave in St Edmund's Burial Ground, East Hill, Dartford. The burial ground closed in 1857, with the gravestones being removed in 1956–57. A plaque marks the approximate spot believed to be the site of the grave. The plaque lies on the side of the park, near the East Hill gate, and an unlinked path.

Memorials

In Camborne, outside the public library, a statue by Leonard Stanford Merrifield depicting Trevithick holding one of his small-scale models was unveiled in 1932 byPrince George, Duke of Kent

Prince George, Duke of Kent (George Edward Alexander Edmund; 20 December 1902 – 25 August 1942) was a member of the British royal family, the fourth son of King George V and Queen Mary. He was a younger brother of kings Edward VIII and George ...

, in front of a crowd of thousands of local people.

On 17 March 2007, Dartford Borough Council invited the Chairman of the Trevithick Society, Phil Hosken, to unveil a Blue plaque

A blue plaque is a permanent sign installed in a public place in the United Kingdom, and certain other countries and territories, to commemorate a link between that location and a famous person, event, or former building on the site, serving a ...

at the Royal Victoria and Bull hotel (formerly The Bull) marking Trevithick's last years in Dartford and the place of his death in 1833. The Blue Plaque is prominently displayed on the hotel's front facade. There is also a plaque at Holy Trinity Church, Dartford.

The Cardiff University

Cardiff University () is a public research university in Cardiff, Wales. It was established in 1883 as the University College of South Wales and Monmouthshire and became a founding college of the University of Wales in 1893. It was renamed Unive ...

Engineering, Computer Science and Physics departments are based around the Trevithick Building which also holds the Trevithick Library, named after Richard Trevithick.

In Gower Street in London, on the wall of the University College

In a number of countries, a university college is a college institution that provides tertiary education but does not have full or independent university status. A university college is often part of a larger university. The precise usage varies f ...

building, an elaborate wall plaque carries the legend: "Close to this place Richard Trevithick (Born 1771 – Died 1833) Pioneer of High Pressure Steam ran in the year 1808 the first steam locomotive to draw passengers." It was erected by "The Trevithick Centenary Memorial Committee".

One of the oldest depictions of Saint Piran's Flag can be seen in a stained glass window at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

, 1888, commemorating Richard Trevithick. The window depicts St Michael at the top and nine Cornish saints, Piran

Piran (; ) is a town in southwestern Slovenia on the Gulf of Piran on the Adriatic Sea. It is one of the three major towns of Slovenian Istria. A bilingual city, with population speaking both Slovene and Italian, Piran is known for its medieva ...

, Petroc, Pinnock, Germanus, Julian, Cyriacus, Constantine, Nonna and Geraint in tiers below. The head of St Piran appears to be a portrait of Trevithick himself and the figure carries the banner of Cornwall.

There is a plaque and memorial situated in Abercynon

Abercynon () is a village and community (Wales), community (and electoral ward) in the Cynon Valley within the unitary authority of Rhondda Cynon Taf, Wales. The community comprises the village and the districts of Carnetown and Grovers Field to ...

, outside the fire station. It says "In commemoration of the achievements of Richard Trevithick who having constructed the first steam locomotive did on February 21st 1804 successfully hail 10 tons of iron and numerous passengers along a tramroad from Merthyr to this precinct where was situated the loading point of the Glamorgan Canal". There is also a building in Abercynon called Ty Trevithick (Trevithick House), named in his honour.

On Penydarren Road, Merthyr Tydfil

Merthyr Tydfil () is the main town in Merthyr Tydfil County Borough, Wales, administered by Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council. It is about north of Cardiff. Often called just Merthyr, it is said to be named after Tydfil, daughter of K ...

there is a memorial on the site of the Penydarren Tramway. The inscription reads "RICHARD TREVITHICK 1771-1833 PIONEER OF HIGH PRESSURE STEAM BUILT THE FIRST STEAM LOCOMOTIVE TO RUN ON RAILS. ON FEBRUARY 21ST 1804 IT TRAVERSED THE SPOT ON WHICH THIS MONUMENT STANDS ON ITS WAY TO ABERCYNON". A short walk north of that is the (slightly misspelled) Trevethick Street, named after Trevithick.

A replica of Trevithick's first full-size steam road locomotive was first displayed at Camborne Trevithick Day 2001, the day chosen for the celebration of Trevithick's public demonstration of the use of high-pressure steam. The team consisting of John Woodward, Mark Rivron and Sean Oliver, have continued to maintain and display the engine at various steam fairs across the country. The ''Puffing Devil'' has proudly led the parade of steam engines at every subsequent Trevithick day up to and including 2014.

Trevithick Drive in Temple Hill, Dartford, was named after Richard Trevithick.

Legacy

The Trevithick Society, a successor toindustrial archaeology

Industrial archaeology (IA) is the systematic study of material evidence associated with the Industry (manufacturing), industrial past. This evidence, collectively referred to as industrial heritage, includes buildings, machinery, artifacts, si ...

organizations that were initially formed to rescue the Levant winding engine from being scrapped, was named in honor of Richard Trevithick. They publish a newsletter, a journal and many books on Cornish engines, the mining industry, engineers, and other industrial archaeological topics.

The active Trevithick Society is not to be confused with the former Trevithick Trust, registered by the Charity Commission in 1994 and removed (ceased to exist) in 2006. The Trevithick Trust attracted grants and did work at various sites in Cornwall, including King Edward Mine

The King Edward Mine at Camborne, Cornwall, in the United Kingdom is a mine owned by Cornwall Council.

At the end of the 19th century, students at the Camborne School of Mines spent much of their time doing practical mining and tin dressing w ...

.

There is also a street named after Trevithick in Merthyr Tydfil.

Richard Trevithick is celebrated in Camborne, Cornwall oTrevithick Day

which is held annually on the last Saturday in April. The day is a community festival with steam engines from all over the UK attending. Towards the end of the day they parade through the streets of Camborne and steam past a statue of Richard Trevithick outside the Passmore Edwards building.

Harry Turtledove

Harry Norman Turtledove (born June 14, 1949) is an American author who is best known for his work in the genres of alternate history, historical fiction, fantasy, science fiction, and mystery fiction. He is a student of history and completed his ...

's alternate history

Alternate history (also referred to as alternative history, allohistory, althist, or simply A.H.) is a subgenre of speculative fiction in which one or more historical events have occurred but are resolved differently than in actual history. As ...

short story " The Iron Elephant" has a character named Richard Trevithick inventing a steam engine in 1782 and subsequently racing a woolly mammoth

The woolly mammoth (''Mammuthus primigenius'') is an extinct species of mammoth that lived from the Middle Pleistocene until its extinction in the Holocene epoch. It was one of the last in a line of mammoth species, beginning with the African ...

- drawn train that it would in time come to supplant. The character was born sometime before 1771, and is American rather than British, indicating he is an analog, rather than the historical figure.

The greatest legacy of Trevithick, of course, is that he set into motion the railway age, and proved that high pressure steam engines were the way forward from low pressure engines. After him came George and Robert Stephenson who created viable locomotives and commercially viable railways, but they only built on what Trevithick laid down before them.

See also

*List of topics related to Cornwall

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to Cornwall:

Cornwall – ceremonial county and unitary authority area of England within the United Kingdom. Cornwall is a peninsula bordered to the north and west by ...

References

Notes

Sources

* * Hodge, James (2003), ''Richard Trevithick'' (''Lifelines''; 6.) Princes Risborough, Buckinghamshire HP27 9AA: Shire Publications * * Lowe, James W. (1975), ''British Steam Locomotive Builders''. Cambridge: Goose (reissued in 1989 by Guild Publishing) * Rogers, Col. H. C. (1961), ''Turnpike to Iron Road'' London: Seeley, Service & Co.; pp. 40–44 * (2 volumes. To be found in the library of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, IMechE, London)External links

The Camborne ‘Trevithick Day’ Website

Cornwall Record Office Online Catalogue for Richard Trevithick

Contributions to the Biography of Richard Trevithick Richard Edmonds, 1859

Richard Trevithick steam engine 1805–06 in the Energy Hall, Science Museum, London

Trevithick Society

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Trevithick, Richard 1771 births 1833 deaths 18th-century English engineers 19th-century English engineers 18th-century British businesspeople 19th-century British businesspeople People from Illogan People of the Industrial Revolution Explorers from Cornwall Locomotive builders and designers British mining engineers