The Net (substance) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English

In 1666, Newton observed that the spectrum of colours exiting a

In 1666, Newton observed that the spectrum of colours exiting a  From this work, he concluded that the lens of any

From this work, he concluded that the lens of any  Newton argued that light is composed of particles or corpuscles, which were refracted by accelerating into a denser medium. He verged on soundlike waves to explain the repeated pattern of reflection and transmission by thin films (''Opticks'' Bk. II, Props. 12), but still retained his theory of 'fits' that disposed corpuscles to be reflected or transmitted (Props.13). Physicists later favoured a purely wavelike explanation of light to account for the

Newton argued that light is composed of particles or corpuscles, which were refracted by accelerating into a denser medium. He verged on soundlike waves to explain the repeated pattern of reflection and transmission by thin films (''Opticks'' Bk. II, Props. 12), but still retained his theory of 'fits' that disposed corpuscles to be reflected or transmitted (Props.13). Physicists later favoured a purely wavelike explanation of light to account for the

In the 1690s, Newton wrote a number of

In the 1690s, Newton wrote a number of

polymath

A polymath or polyhistor is an individual whose knowledge spans many different subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific problems. Polymaths often prefer a specific context in which to explain their knowledge, ...

active as a mathematician

A mathematician is someone who uses an extensive knowledge of mathematics in their work, typically to solve mathematical problems. Mathematicians are concerned with numbers, data, quantity, mathematical structure, structure, space, Mathematica ...

, physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe. Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

, astronomer

An astronomer is a scientist in the field of astronomy who focuses on a specific question or field outside the scope of Earth. Astronomers observe astronomical objects, such as stars, planets, natural satellite, moons, comets and galaxy, galax ...

, alchemist

Alchemy (from the Arabic word , ) is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practised in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first ...

, theologian

Theology is the study of religious belief from a religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of ...

, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of History of science, modern science during the early modern period, when developments in History of mathematics#Mathematics during the Scientific Revolution, mathemati ...

and the Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

that followed. His book (''Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy''), first published in 1687, achieved the first great unification in physics and established classical mechanics

Classical mechanics is a Theoretical physics, physical theory describing the motion of objects such as projectiles, parts of Machine (mechanical), machinery, spacecraft, planets, stars, and galaxies. The development of classical mechanics inv ...

. Newton also made seminal contributions to optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of optical instruments, instruments that use or Photodetector, detect it. Optics usually describes t ...

, and shares credit with German mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (or Leibnitz; – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat who is credited, alongside Sir Isaac Newton, with the creation of calculus in addition to ...

for formulating infinitesimal calculus

Calculus is the mathematical study of continuous change, in the same way that geometry is the study of shape, and algebra is the study of generalizations of arithmetic operations.

Originally called infinitesimal calculus or "the calculus of ...

, though he developed calculus years before Leibniz. Newton contributed to and refined the scientific method

The scientific method is an Empirical evidence, empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has been referred to while doing science since at least the 17th century. Historically, it was developed through the centuries from the ancient and ...

, and his work is considered the most influential in bringing forth modern science.

In the , Newton formulated the laws of motion

In physics, a number of noted theories of the motion of objects have developed. Among the best known are:

* Classical mechanics

** Newton's laws of motion

** Euler's laws of motion

** Cauchy's equations of motion

** Kepler's laws of planetary mo ...

and universal gravitation

Newton's law of universal gravitation describes gravity as a force by stating that every particle attracts every other particle in the universe with a force that is Proportionality (mathematics)#Direct proportionality, proportional to the product ...

that formed the dominant scientific viewpoint for centuries until it was superseded by the theory of relativity

The theory of relativity usually encompasses two interrelated physics theories by Albert Einstein: special relativity and general relativity, proposed and published in 1905 and 1915, respectively. Special relativity applies to all physical ph ...

. He used his mathematical description of gravity

In physics, gravity (), also known as gravitation or a gravitational interaction, is a fundamental interaction, a mutual attraction between all massive particles. On Earth, gravity takes a slightly different meaning: the observed force b ...

to derive Kepler's laws of planetary motion

In astronomy, Kepler's laws of planetary motion, published by Johannes Kepler in 1609 (except the third law, which was fully published in 1619), describe the orbits of planets around the Sun. These laws replaced circular orbits and epicycles in ...

, account for tide

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the Moon (and to a much lesser extent, the Sun) and are also caused by the Earth and Moon orbiting one another.

Tide tables ...

s, the trajectories

A trajectory or flight path is the path that an object with mass in motion follows through space as a function of time. In classical mechanics, a trajectory is defined by Hamiltonian mechanics via canonical coordinates; hence, a complete traje ...

of comet

A comet is an icy, small Solar System body that warms and begins to release gases when passing close to the Sun, a process called outgassing. This produces an extended, gravitationally unbound atmosphere or Coma (cometary), coma surrounding ...

s, the precession of the equinoxes

In astronomy, axial precession is a gravity-induced, slow, and continuous change in the orientation of an astronomical body's Rotation around a fixed axis, rotational axis. In the absence of precession, the astronomical body's orbit would show ...

and other phenomena, eradicating doubt about the Solar System

The Solar SystemCapitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Sola ...

's heliocentricity. Newton solved the two-body problem

In classical mechanics, the two-body problem is to calculate and predict the motion of two massive bodies that are orbiting each other in space. The problem assumes that the two bodies are point particles that interact only with one another; th ...

, and introduced the three-body problem

In physics, specifically classical mechanics, the three-body problem is to take the initial positions and velocities (or momenta) of three point masses orbiting each other in space and then calculate their subsequent trajectories using Newton' ...

. He demonstrated that the motion of objects on Earth and celestial bodies

An astronomical object, celestial object, stellar object or heavenly body is a naturally occurring physical entity, association, or structure that exists within the observable universe. In astronomy, the terms ''object'' and ''body'' are of ...

could be accounted for by the same principles. Newton's inference that the Earth is an oblate spheroid

A spheroid, also known as an ellipsoid of revolution or rotational ellipsoid, is a quadric surface obtained by rotating an ellipse about one of its principal axes; in other words, an ellipsoid with two equal semi-diameters. A spheroid has circu ...

was later confirmed by the geodetic measurements of Alexis Clairaut

Alexis Claude Clairaut (; ; 13 May 1713 – 17 May 1765) was a French mathematician, astronomer, and geophysicist. He was a prominent Newtonian whose work helped to establish the validity of the principles and results that Isaac Newton, Sir Isaa ...

, Charles Marie de La Condamine

Charles Marie de La Condamine (; 28 January 1701 – 4 February 1774) was a French explorer, geographer, and mathematician. He spent ten years in territory which is now Ecuador, measuring the length of a degree of latitude at the equator and pre ...

, and others, convincing most European scientists of the superiority of Newtonian mechanics over earlier systems. He was also the first to calculate the age of Earth

The age of Earth is estimated to be 4.54 ± 0.05 billion years. This age may represent the age of Earth's accretion, or core formation, or of the material from which Earth formed. This dating is based on evidence from radiometric age-dating of ...

by experiment, and described a precursor to the modern wind tunnel

A wind tunnel is "an apparatus for producing a controlled stream of air for conducting aerodynamic experiments". The experiment is conducted in the test section of the wind tunnel and a complete tunnel configuration includes air ducting to and f ...

.

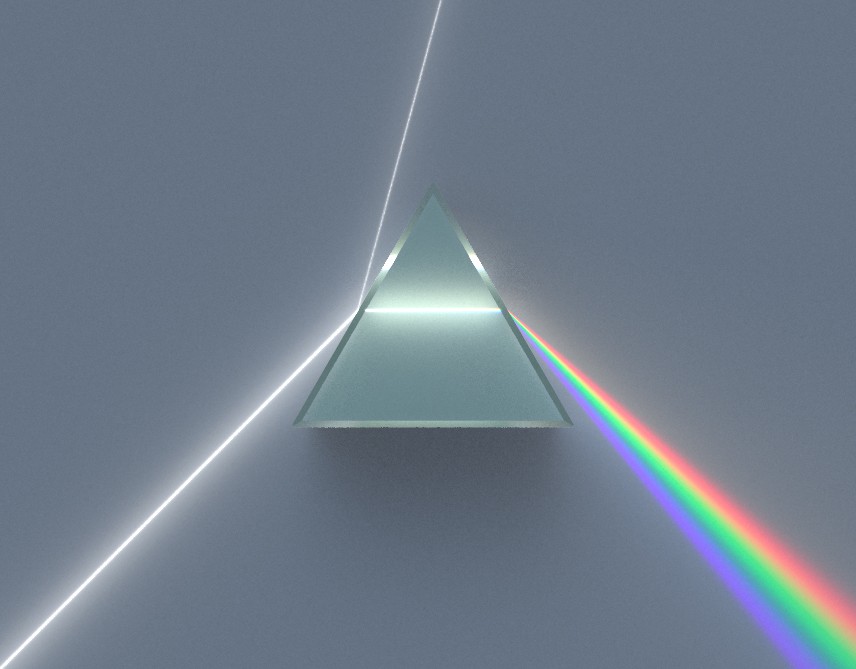

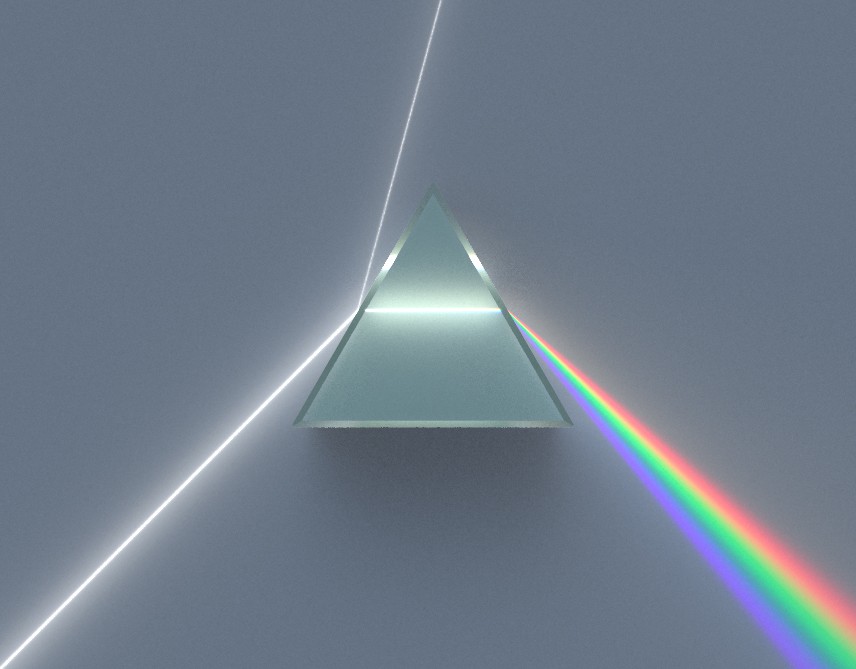

Newton built the first reflecting telescope and developed a sophisticated theory of colour based on the observation that a prism

PRISM is a code name for a program under which the United States National Security Agency (NSA) collects internet communications from various U.S. internet companies. The program is also known by the SIGAD . PRISM collects stored internet ...

separates white light

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no chroma). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully (or almost fully) reflect and scatter all the visible wavelen ...

into the colours of the visible spectrum

The visible spectrum is the spectral band, band of the electromagnetic spectrum that is visual perception, visible to the human eye. Electromagnetic radiation in this range of wavelengths is called ''visible light'' (or simply light).

The optica ...

. His work on light was collected in his book ''Opticks

''Opticks: or, A Treatise of the Reflexions, Refractions, Inflexions and Colours of Light'' is a collection of three books by Isaac Newton that was published in English language, English in 1704 (a scholarly Latin translation appeared in 1706). ...

'', published in 1704. He originated prisms as beam expanders and multiple-prism arrays, which would later become integral to the development of tunable lasers. He also anticipated wave–particle duality

Wave–particle duality is the concept in quantum mechanics that fundamental entities of the universe, like photons and electrons, exhibit particle or wave (physics), wave properties according to the experimental circumstances. It expresses the in ...

and was the first to theorize the Goos–Hänchen effect

The Goos–Hänchen effect, named after Hermann Fritz Gustav Goos (1883–1968) and Hilda Hänchen (1919–2013), but first suggested by Isaac Newton (1643–1727), is an optical phenomenon in which linearly polarized light undergoes a ...

. He further formulated an empirical law of cooling, which was the first heat transfer formulation and serves as the formal basis of convective heat transfer

Convection (or convective heat transfer) is the transfer of heat from one place to another due to the movement of fluid. Although often discussed as a distinct method of heat transfer, convective heat transfer involves the combined processes of ...

, made the first theoretical calculation of the speed of sound

The speed of sound is the distance travelled per unit of time by a sound wave as it propagates through an elasticity (solid mechanics), elastic medium. More simply, the speed of sound is how fast vibrations travel. At , the speed of sound in a ...

, and introduced the notions of a Newtonian fluid

A Newtonian fluid is a fluid in which the viscous stresses arising from its flow are at every point linearly correlated to the local strain rate — the rate of change of its deformation over time. Stresses are proportional to the rate of cha ...

and a black body

A black body or blackbody is an idealized physical body that absorbs all incident electromagnetic radiation, regardless of frequency or angle of incidence. The radiation emitted by a black body in thermal equilibrium with its environment is ...

. He was also the first to explain the Magnus effect

The Magnus effect is a phenomenon that occurs when a spin (geometry), spinning Object (physics), object is moving through a fluid. A lift (force), lift force acts on the spinning object and its path may be deflected in a manner not present when ...

. Furthermore, he made early studies into electricity

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter possessing an electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as described by Maxwel ...

. In addition to his creation of calculus, Newton's work on mathematics was extensive. He generalized the binomial theorem

In elementary algebra, the binomial theorem (or binomial expansion) describes the algebraic expansion of powers of a binomial. According to the theorem, the power expands into a polynomial with terms of the form , where the exponents and a ...

to any real number, introduced the Puiseux series

In mathematics, Puiseux series are a generalization of power series that allow for negative and fractional exponents of the indeterminate. For example, the series

: \begin

x^ &+ 2x^ + x^ + 2x^ + x^ + x^5 + \cdots\\

&=x^+ 2x^ + x^ + 2x^ + x^ + ...

, was the first to state Bézout's theorem

In algebraic geometry, Bézout's theorem is a statement concerning the number of common zeros of polynomials in indeterminates. In its original form the theorem states that ''in general'' the number of common zeros equals the product of the de ...

, classified most of the cubic plane curves, contributed to the study of Cremona transformations, developed a method for approximating the roots of a function, and also originated the Newton–Cotes formulas

In numerical analysis, the Newton–Cotes formulas, also called the Newton–Cotes quadrature rules or simply Newton–Cotes rules, are a group of formulas for numerical integration (also called ''quadrature'') based on evaluating the integrand a ...

for numerical integration

In analysis, numerical integration comprises a broad family of algorithms for calculating the numerical value of a definite integral.

The term numerical quadrature (often abbreviated to quadrature) is more or less a synonym for "numerical integr ...

. He further initiated the field of calculus of variations

The calculus of variations (or variational calculus) is a field of mathematical analysis that uses variations, which are small changes in Function (mathematics), functions

and functional (mathematics), functionals, to find maxima and minima of f ...

, devised an early form of regression analysis, and was a pioneer of vector analysis

Vector calculus or vector analysis is a branch of mathematics concerned with the differentiation and integration of vector fields, primarily in three-dimensional Euclidean space, \mathbb^3. The term ''vector calculus'' is sometimes used as a ...

.

Newton was a fellow of Trinity College Trinity College may refer to:

Australia

* Trinity Anglican College, an Anglican coeducational primary and secondary school in , New South Wales

* Trinity Catholic College, Auburn, a coeducational school in the inner-western suburbs of Sydney, New ...

and the second Lucasian Professor of Mathematics

The Lucasian Chair of Mathematics () is a mathematics professorship in the University of Cambridge, England; its holder is known as the Lucasian Professor. The post was founded in 1663 by Henry Lucas (politician), Henry Lucas, who was Cambridge U ...

at the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

; he was appointed at the age of 26. He was a devout but unorthodox Christian who privately rejected the doctrine of the Trinity

The Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the Christian doctrine concerning the nature of God, which defines one God existing in three, , consubstantial divine persons: God the Father, God the Son (Jesus Christ) and God the Holy Spirit, thr ...

. He refused to take holy orders

In certain Christian denominations, holy orders are the ordination, ordained ministries of bishop, priest (presbyter), and deacon, and the sacrament or rite by which candidates are ordained to those orders. Churches recognizing these orders inclu ...

in the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

, unlike most members of the Cambridge faculty of the day. Beyond his work on the mathematical sciences

The Mathematical Sciences are a group of areas of study that includes, in addition to mathematics, those academic disciplines that are primarily mathematical in nature but may not be universally considered subfields of mathematics proper.

Statisti ...

, Newton dedicated much of his time to the study of alchemy

Alchemy (from the Arabic word , ) is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practised in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first ...

and biblical chronology

The chronology of the Bible is an elaborate system of lifespans, "generations", and other means by which the Masoretic Hebrew Bible (the text of the Bible most commonly in use today) measures the passage of events from the creation to around 164 ...

, but most of his work in those areas remained unpublished until long after his death. Politically and personally tied to the Whig party, Newton served two brief terms as Member of Parliament for the University of Cambridge, in 1689–1690 and 1701–1702. He was knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

ed by Queen Anne in 1705 and spent the last three decades of his life in London, serving as Warden

A warden is a custodian, defender, or guardian. Warden is often used in the sense of a watchman or guardian, as in a prison warden. It can also refer to a chief or head official, as in the Warden of the Mint.

''Warden'' is etymologically ident ...

(1696–1699) and Master

Master, master's or masters may refer to:

Ranks or titles

In education:

*Master (college), head of a college

*Master's degree, a postgraduate or sometimes undergraduate degree in the specified discipline

*Schoolmaster or master, presiding office ...

(1699–1727) of the Royal Mint

The Royal Mint is the United Kingdom's official maker of British coins. It is currently located in Llantrisant, Wales, where it moved in 1968.

Operating under the legal name The Royal Mint Limited, it is a limited company that is wholly ow ...

, in which he increased the accuracy and security of British coinage, as well as the president of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

(1703–1727).

Early life

Isaac Newton was born (according to theJulian calendar

The Julian calendar is a solar calendar of 365 days in every year with an additional leap day every fourth year (without exception). The Julian calendar is still used as a religious calendar in parts of the Eastern Orthodox Church and in parts ...

in use in England at the time) on Christmas Day, 25 December 1642 ( NS 4 January 1643) at Woolsthorpe Manor

Woolsthorpe Manor in Woolsthorpe-by-Colsterworth, near Grantham, Lincolnshire, England, is the birthplace and family home of Sir Isaac Newton. In the orchard within the grounds is Newton's famous apple tree. A Grade I listed building, it is no ...

in Woolsthorpe-by-Colsterworth

Woolsthorpe-by-Colsterworth (to distinguish it from Woolsthorpe-by-Belvoir in the same county) is a hamlet in the South Kesteven district of Lincolnshire, England, within the civil parish of Colsterworth. It is best known as the birthplace of ...

, a hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a Shakespearean tragedy, tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play. Set in Denmark, the play (the ...

in the county of Lincolnshire. His father, also named Isaac Newton, had died three months before. Born prematurely, Newton was a small child; his mother Hannah Ayscough reportedly said that he could have fit inside a quart

The quart (symbol: qt) is a unit of volume equal to a quarter of a gallon. Three kinds of quarts are currently used: the liquid quart and dry quart of the US customary system and the of the British imperial system. All are roughly equal ...

mug. When Newton was three, his mother remarried and went to live with her new husband, the Reverend Barnabas Smith, leaving her son in the care of his maternal grandmother, Margery Ayscough (née Blythe). Newton disliked his stepfather and maintained some enmity towards his mother for marrying him, as revealed by this entry in a list of sins committed up to the age of 19: "Threatening my father and mother Smith to burn them and the house over them." Newton's mother had three children (Mary, Benjamin, and Hannah) from her second marriage.

The King's School

From the age of about twelve until he was seventeen, Newton was educated at The King's School inGrantham

Grantham () is a market town and civil parish in the South Kesteven district of Lincolnshire, England, situated on the banks of the River Witham and bounded to the west by the A1 road (Great Britain), A1 road. It lies south of Lincoln, England ...

, which taught Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

and Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

and probably imparted a significant foundation of mathematics. He was removed from school by his mother and returned to Woolsthorpe-by-Colsterworth by October 1659. His mother, widowed for the second time, attempted to make him a farmer, an occupation he hated. Henry Stokes, master at The King's School, persuaded his mother to send him back to school. Motivated partly by a desire for revenge against a schoolyard bully, he became the top-ranked student, distinguishing himself mainly by building sundial

A sundial is a horology, horological device that tells the time of day (referred to as civil time in modern usage) when direct sunlight shines by the position of the Sun, apparent position of the Sun in the sky. In the narrowest sense of the ...

s and models of windmills.

University of Cambridge

In June 1661, Newton was admitted toTrinity College Trinity College may refer to:

Australia

* Trinity Anglican College, an Anglican coeducational primary and secondary school in , New South Wales

* Trinity Catholic College, Auburn, a coeducational school in the inner-western suburbs of Sydney, New ...

at the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

. His uncle the Reverend William Ayscough, who had studied at Cambridge, recommended him to the university. At Cambridge, Newton started as a subsizar

At Trinity College Dublin and the University of Cambridge, a sizar is an undergraduate who receives some form of assistance such as meals, lower fees or lodging during his or her period of study, in some cases in return for doing a defined jo ...

, paying his way by performing valet

A valet or varlet is a male servant who serves as personal attendant to his employer. In the Middle Ages and Ancien Régime, ''valet de chambre'' was a role for junior courtiers and specialists such as artists in a royal court, but the term "va ...

duties until he was awarded a scholarship in 1664, which covered his university costs for four more years until the completion of his MA. At the time, Cambridge's teachings were based on those of Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

, whom Newton read along with then more modern philosophers, including René Descartes

René Descartes ( , ; ; 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and Modern science, science. Mathematics was paramou ...

and astronomer

An astronomer is a scientist in the field of astronomy who focuses on a specific question or field outside the scope of Earth. Astronomers observe astronomical objects, such as stars, planets, natural satellite, moons, comets and galaxy, galax ...

s such as Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

and Thomas Street. He set down in his notebook a series of " ''Quaestiones''" about mechanical philosophy

Mechanism is the belief that natural wholes (principally living things) are similar to complicated machines or artifacts, composed of parts lacking any intrinsic relationship to each other.

The doctrine of mechanism in philosophy comes in two diff ...

as he found it. In 1665, he discovered the generalised binomial theorem

In elementary algebra, the binomial theorem (or binomial expansion) describes the algebraic expansion of powers of a binomial. According to the theorem, the power expands into a polynomial with terms of the form , where the exponents and a ...

and began to develop a mathematical theory that later became calculus

Calculus is the mathematics, mathematical study of continuous change, in the same way that geometry is the study of shape, and algebra is the study of generalizations of arithmetic operations.

Originally called infinitesimal calculus or "the ...

. Soon after Newton obtained his BA degree at Cambridge in August 1665, the university temporarily closed as a precaution against the Great Plague

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic that occurred in Europe from 1346 to 1353. It was one of the most fatal pandemics in human history; as many as people perished, perhaps 50% of Europe's 14th century population. The disease is c ...

.

Although he had been undistinguished as a Cambridge student, his private studies and the years following his bachelor's degree have been described as "the richest and most productive ever experienced by a scientist". The next two years alone saw the development of theories on calculus, optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of optical instruments, instruments that use or Photodetector, detect it. Optics usually describes t ...

, and the law of gravitation

Newton's law of universal gravitation describes gravity as a force by stating that every particle attracts every other particle in the universe with a force that is proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the ...

, at his home in Woolsthorpe. The physicist Louis T. More stated that "There are no other examples of achievement in the history of science to compare with that of Newton during those two golden years."

Newton has been described as an "exceptionally organized" person when it came to note-taking, further dog-earing pages he saw as important. Furthermore, Newton's "indexes look like present-day indexes: They are alphabetical, by topic." His books showed his interests to be wide-ranging, with Newton himself described as a "Janusian thinker, someone who could mix and combine seemingly disparate fields to stimulate creative breakthroughs."

In April 1667, Newton returned to the University of Cambridge, and in October he was elected as a fellow of Trinity. Fellows were required to take holy orders

In certain Christian denominations, holy orders are the ordination, ordained ministries of bishop, priest (presbyter), and deacon, and the sacrament or rite by which candidates are ordained to those orders. Churches recognizing these orders inclu ...

and be ordained as Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

priests, although this was not enforced in the Restoration years, and an assertion of conformity to the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

was sufficient. He made the commitment that "I will either set Theology as the object of my studies and will take holy orders when the time prescribed by these statutes yearsarrives, or I will resign from the college." Up until this point he had not thought much about religion and had twice signed his agreement to the Thirty-nine Articles, the basis of Church of England doctrine. By 1675 the issue could not be avoided, and his unconventional views stood in the way.

His academic work impressed the Lucasian Professor Isaac Barrow

Isaac Barrow (October 1630 – 4 May 1677) was an English Christian theologian and mathematician who is generally given credit for his early role in the development of infinitesimal calculus; in particular, for proof of the fundamental theorem ...

, who was anxious to develop his own religious and administrative potential (he became master of Trinity College two years later); in 1669, Newton succeeded him, only one year after receiving his MA. Newton argued that this should exempt him from the ordination requirement, and King Charles II, whose permission was needed, accepted this argument; thus, a conflict between Newton's religious views and Anglican orthodoxy was averted. He was appointed at the age of 26.

As accomplished as Newton was as a theoretician he was less effective as a teacher as his classes were almost always empty. Humphrey Newton, his sizar

At Trinity College Dublin and the University of Cambridge, a sizar is an Undergraduate education, undergraduate who receives some form of assistance such as meals, lower fees or lodging during his or her period of study, in some cases in retur ...

(assistant), noted that Newton would arrive on time and, if the room was empty, he would reduce his lecture time in half from 30 to 15 minutes, talk to the walls, then retreat to his experiments, thus fulfilling his contractual obligations. For his part Newton enjoyed neither teaching nor students. Over his career he was only assigned three students to tutor and none were noteworthy.

The Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at Cambridge position included the responsibility of instructing geography

Geography (from Ancient Greek ; combining 'Earth' and 'write', literally 'Earth writing') is the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. Geography is an all-encompassing discipline that seeks an understanding o ...

. In 1672, and again in 1681, Newton published a revised, corrected, and amended edition of the ''Geographia Generalis

''Geographia Generalis'' is a seminal work in the field of geography authored by Bernhardus Varenius, first published in 1650. This influential text laid the foundations for modern geographical science and was pivotal in the development of geogr ...

'', a geography textbook first published in 1650 by the then-deceased Bernhardus Varenius

Bernhardus Varenius (Bernhard Varen) (1622, Hitzacker, Holy Roman Empire1650) was a German geographer.

Life

His early years (from 1627) were spent at Uelzen, where his father was court preacher to the duke of Brunswick. Varenius studied at th ...

. In the ''Geographia Generalis,'' Varenius attempted to create a theoretical foundation linking scientific principles to classical concepts in geography, and considered geography to be a mix between science and pure mathematics applied to quantifying features of the Earth. While it is unclear if Newton ever lectured in geography, the 1733 Dugdale and Shaw English translation of the book stated Newton published the book to be read by students while he lectured on the subject. The ''Geographia Generalis'' is viewed by some as the dividing line between ancient and modern traditions in the history of geography

The History of geography includes many histories of geography which have differed over time and between different cultural and political groups. In more recent developments, geography has become a distinct academic discipline. 'Geography' derive ...

, and Newton's involvement in the subsequent editions is thought to be a large part of the reason for this enduring legacy.

Newton was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1672.

Mid-life

Calculus

Newton's work has been said "to distinctly advance every branch of mathematics then studied". His work on calculus, usually referred to as fluxions, began in 1664, and by 20 May 1665 as seen in a manuscript, Newton "had already developed the calculus to the point where he could compute the tangent and the curvature at any point of a continuous curve". Another manuscript of October 1666, is now published among Newton's mathematical papers. His work ''De analysi per aequationes numero terminorum infinitas

''De analysi per aequationes numero terminorum infinitas'' (or ''On analysis by infinite series'', ''On Analysis by Equations with an infinite number of terms'', or ''On the Analysis by means of equations of an infinite number of terms'') is a m ...

'', sent by Isaac Barrow

Isaac Barrow (October 1630 – 4 May 1677) was an English Christian theologian and mathematician who is generally given credit for his early role in the development of infinitesimal calculus; in particular, for proof of the fundamental theorem ...

to John Collins in June 1669, was identified by Barrow in a letter sent to Collins that August as the work "of an extraordinary genius and proficiency in these things". Newton later became involved in a dispute with Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (or Leibnitz; – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat who is credited, alongside Sir Isaac Newton, with the creation of calculus in addition to ...

over priority in the development of calculus. Both are now credited with independently developing calculus, though with very different mathematical notation

Mathematical notation consists of using glossary of mathematical symbols, symbols for representing operation (mathematics), operations, unspecified numbers, relation (mathematics), relations, and any other mathematical objects and assembling ...

s. However, it is established that Newton came to develop calculus much earlier than Leibniz. The notation of Leibniz is recognized as the more convenient notation, being adopted by continental European mathematicians, and after 1820, by British mathematicians.

Historian of science A. Rupert Hall notes that while Leibniz deserves credit for his independent formulation of calculus, Newton was undoubtedly the first to develop it, stating:Hall further notes that in ''Principia'', Newton was able to "formulate and resolve problems by the integration of differential equations" and "in fact, he anticipated in his book many results that later exponents of the calculus regarded as their own novel achievements." Hall notes Newton's rapid development of calculus in comparison to his contemporaries, stating that Newton "well before 1690 . . . had reached roughly the point in the development of the calculus that Leibniz, the two Bernoullis, L’Hospital, Hermann and others had by joint efforts reached in print by the early 1700s".

Despite the convenience of Leibniz's notation, it has been noted that Newton's notation could also have developed multivariate techniques, with his dot notation still widely used in physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

. Some academics have noted the richness and depth of Newton's work, such as physicist Roger Penrose

Sir Roger Penrose (born 8 August 1931) is an English mathematician, mathematical physicist, Philosophy of science, philosopher of science and Nobel Prize in Physics, Nobel Laureate in Physics. He is Emeritus Rouse Ball Professor of Mathematics i ...

, stating "in most cases Newton’s geometrical methods are not only more concise and elegant, they reveal deeper principles than would become evident by the use of those formal methods of calculus that nowadays would seem more direct." Mathematician Vladimir Arnold

Vladimir Igorevich Arnold (or Arnol'd; , ; 12 June 1937 – 3 June 2010) was a Soviet and Russian mathematician. He is best known for the Kolmogorov–Arnold–Moser theorem regarding the stability of integrable systems, and contributed to s ...

states "Comparing the texts of Newton with the comments of his successors, it is striking how Newton’s original presentation is more modern, more understandable and richer in ideas than the translation due to commentators of his geometrical ideas into the formal language of the calculus of Leibniz."

His work extensively uses calculus in geometric form based on limiting values of the ratios of vanishingly small quantities: in the ''Principia'' itself, Newton gave demonstration of this under the name of "the method of first and last ratios" and explained why he put his expositions in this form, remarking also that "hereby the same thing is performed as by the method of indivisibles." Because of this, the ''Principia'' has been called "a book dense with the theory and application of the infinitesimal calculus" in modern times and in Newton's time "nearly all of it is of this calculus." His use of methods involving "one or more orders of the infinitesimally small" is present in his ''De motu corporum in gyrum'' of 1684 and in his papers on motion "during the two decades preceding 1684".

Newton had been reluctant to publish his calculus because he feared controversy and criticism. He was close to the Swiss mathematician Nicolas Fatio de Duillier

Nicolas Fatio de Duillier (also spelled Faccio or Facio; 16 February 1664 – 10 May 1753) was a mathematician, Natural philosophy, natural philosopher, astronomer, inventor, and religious campaigner. Born in Basel, Switzerland, Fatio mostly ...

. In 1691, Duillier started to write a new version of Newton's ''Principia'', and corresponded with Leibniz. In 1693, the relationship between Duillier and Newton deteriorated and the book was never completed. Starting in 1699, Duillier accused Leibniz of plagiarism. Mathematician John Keill

John Keill FRS (1 December 1671 – 31 August 1721) was a Scottish mathematician, natural philosopher, and cryptographer who was an important defender of Isaac Newton.

Biography

Keill was born in Edinburgh, Scotland on 1 December 1671. His fa ...

accused Leibniz of plagiarism in 1708 in the Royal Society journal, thereby deteriorating the situation even more. The dispute then broke out in full force in 1711 when the Royal Society proclaimed in a study that it was Newton who was the true discoverer and labelled Leibniz a fraud; it was later found that Newton wrote the study's concluding remarks on Leibniz. Thus began the bitter controversy which marred the lives of both men until Leibniz's death in 1716.

Newton is credited with the generalised binomial theorem, valid for any exponent. He discovered Newton's identities

In mathematics, Newton's identities, also known as the Girard–Newton formulae, give relations between two types of symmetric polynomials, namely between power sums and elementary symmetric polynomials. Evaluated at the roots of a monic polynomi ...

, Newton's method

In numerical analysis, the Newton–Raphson method, also known simply as Newton's method, named after Isaac Newton and Joseph Raphson, is a root-finding algorithm which produces successively better approximations to the roots (or zeroes) of a ...

, classified cubic plane curve

In mathematics, a cubic plane curve is a plane algebraic curve defined by a cubic equation

:

applied to homogeneous coordinates for the projective plane; or the inhomogeneous version for the affine space determined by setting in such an ...

s (polynomials

In mathematics, a polynomial is a mathematical expression consisting of indeterminates (also called variables) and coefficients, that involves only the operations of addition, subtraction, multiplication and exponentiation to nonnegative int ...

of degree three in two variables

Variable may refer to:

Computer science

* Variable (computer science), a symbolic name associated with a value and whose associated value may be changed

Mathematics

* Variable (mathematics), a symbol that represents a quantity in a mathemat ...

), is a founder of the theory of Cremona transformations, made substantial contributions to the theory of finite differences

A finite difference is a mathematical expression of the form . Finite differences (or the associated difference quotients) are often used as approximations of derivatives, such as in numerical differentiation.

The difference operator, commonly d ...

, with Newton regarded as "the single most significant contributor to finite difference interpolation

In the mathematics, mathematical field of numerical analysis, interpolation is a type of estimation, a method of constructing (finding) new data points based on the range of a discrete set of known data points.

In engineering and science, one ...

", with many formulas created by Newton. He was the first to state Bézout's theorem

In algebraic geometry, Bézout's theorem is a statement concerning the number of common zeros of polynomials in indeterminates. In its original form the theorem states that ''in general'' the number of common zeros equals the product of the de ...

, and was also the first to use fractional indices and to employ coordinate geometry

In mathematics, analytic geometry, also known as coordinate geometry or Cartesian geometry, is the study of geometry using a coordinate system. This contrasts with synthetic geometry.

Analytic geometry is used in physics and engineering, and als ...

to derive solutions to Diophantine equations ''Diophantine'' means pertaining to the ancient Greek mathematician Diophantus. A number of concepts bear this name:

*Diophantine approximation

In number theory, the study of Diophantine approximation deals with the approximation of real n ...

. He approximated partial

Partial may refer to:

Mathematics

*Partial derivative, derivative with respect to one of several variables of a function, with the other variables held constant

** ∂, a symbol that can denote a partial derivative, sometimes pronounced "partial d ...

sums of the harmonic series by logarithms

In mathematics, the logarithm of a number is the exponent by which another fixed value, the base, must be raised to produce that number. For example, the logarithm of to base is , because is to the rd power: . More generally, if , the ...

(a precursor to Euler's summation formula) and was the first to use power series

In mathematics, a power series (in one variable) is an infinite series of the form

\sum_^\infty a_n \left(x - c\right)^n = a_0 + a_1 (x - c) + a_2 (x - c)^2 + \dots

where ''a_n'' represents the coefficient of the ''n''th term and ''c'' is a co ...

with confidence and to revert power series. He introduced the Puisseux series. He originated the Newton-Cotes formulas for numerical integration

In analysis, numerical integration comprises a broad family of algorithms for calculating the numerical value of a definite integral.

The term numerical quadrature (often abbreviated to quadrature) is more or less a synonym for "numerical integr ...

. Newton's work on infinite series was inspired by Simon Stevin

Simon Stevin (; 1548–1620), sometimes called Stevinus, was a County_of_Flanders, Flemish mathematician, scientist and music theorist. He made various contributions in many areas of science and engineering, both theoretical and practical. He a ...

's decimals. He also initiated the field of calculus of variations

The calculus of variations (or variational calculus) is a field of mathematical analysis that uses variations, which are small changes in Function (mathematics), functions

and functional (mathematics), functionals, to find maxima and minima of f ...

, being the first to clearly formulate and correctly solve a problem in the field, that being Newton's minimal resistance problem Newton's minimal resistance problem is a problem of finding a solid of revolution which experiences a minimum resistance when it moves through a homogeneous fluid with constant velocity in the direction of the axis of revolution, named after Isaac N ...

, which he posed and solved in 1685, and then later published in ''Principia'' in 1687. It is regarded as one of the most difficult problems tackled by variational methods prior to the twentieth century. He then used calculus of variations in his solving of the brachistochrone curve

In physics and mathematics, a brachistochrone curve (), or curve of fastest descent, is the one lying on the plane between a point ''A'' and a lower point ''B'', where ''B'' is not directly below ''A'', on which a bead slides frictionlessly under ...

problem in 1697, which was posed by Johann Bernoulli

Johann Bernoulli (also known as Jean in French or John in English; – 1 January 1748) was a Swiss people, Swiss mathematician and was one of the many prominent mathematicians in the Bernoulli family. He is known for his contributions to infin ...

in 1696, thus he pioneered the field with his work on the two problems. He was also a pioneer of vector analysis

Vector calculus or vector analysis is a branch of mathematics concerned with the differentiation and integration of vector fields, primarily in three-dimensional Euclidean space, \mathbb^3. The term ''vector calculus'' is sometimes used as a ...

, as he demonstrated how to apply the parallelogram law for adding various physical quantities and realized that these quantities could be broken down into components in any direction.

Optics

In 1666, Newton observed that the spectrum of colours exiting a

In 1666, Newton observed that the spectrum of colours exiting a prism

PRISM is a code name for a program under which the United States National Security Agency (NSA) collects internet communications from various U.S. internet companies. The program is also known by the SIGAD . PRISM collects stored internet ...

in the position of minimum deviation

In a Prism (optics), prism, the angle of deviation () decreases with increase in the angle of incidence () up to a particular angle. This angle of incidence where the angle of deviation in a prism is minimum is called the minimum deviation positio ...

is oblong, even when the light ray entering the prism is circular, which is to say, the prism refracts different colours by different angles. This led him to conclude that colour is a property intrinsic to light – a point which had, until then, been a matter of debate.

From 1670 to 1672, Newton lectured on optics. During this period he investigated the refraction

In physics, refraction is the redirection of a wave as it passes from one transmission medium, medium to another. The redirection can be caused by the wave's change in speed or by a change in the medium. Refraction of light is the most commo ...

of light, demonstrating that the multicoloured image produced by a prism, which he named a spectrum

A spectrum (: spectra or spectrums) is a set of related ideas, objects, or properties whose features overlap such that they blend to form a continuum. The word ''spectrum'' was first used scientifically in optics to describe the rainbow of co ...

, could be recomposed into white light by a lens

A lens is a transmissive optical device that focuses or disperses a light beam by means of refraction. A simple lens consists of a single piece of transparent material, while a compound lens consists of several simple lenses (''elements'') ...

and a second prism. Modern scholarship has revealed that Newton's analysis and resynthesis of white light owes a debt to corpuscular alchemy.

In his work on Newton's rings

Newton's rings is a phenomenon in which an interference pattern is created by the reflection of light between two surfaces, typically a spherical surface and an adjacent touching flat surface. It is named after Isaac Newton, who investigated th ...

in 1671, he used a method that was unprecedented in the 17th century, as "he ''averaged'' all of the differences, and he then calculated the difference between the average and the value for the first ring", in effect introducing a now standard method for reducing noise in measurements, and which does not appear elsewhere at the time. He extended his "error-slaying method" to studies of equinoxes in 1700, which was described as an "altogether unprecedented method" but differed in that here "Newton required good values for each of the original equinoctial times, and so he devised a method that allowed them to, as it were, self-correct." Newton wrote down the first of the two 'normal equations' known from ordinary least squares

In statistics, ordinary least squares (OLS) is a type of linear least squares method for choosing the unknown parameters in a linear regression

In statistics, linear regression is a statistical model, model that estimates the relationship ...

, and devised an early form of regression analysis, as he averaged a set of data, 50 years before Tobias Mayer

Tobias Mayer (17 February 172320 February 1762) was a German astronomer famous for his studies of the Moon.

He was born at Marbach, in Württemberg, and brought up at Esslingen in poor circumstances. A self-taught mathematician, he earned a l ...

and also "summing the residuals to zero he ''forced'' the regression line to pass through the average point". Newton also differentiated between two uneven sets of data and may have considered an optimal solution regarding bias, although not in terms of effectiveness.

He showed that coloured light does not change its properties by separating out a coloured beam and shining it on various objects, and that regardless of whether reflected, scattered, or transmitted, the light remains the same colour. Thus, he observed that colour is the result of objects interacting with already-coloured light rather than objects generating the colour themselves. This is known as Newton's theory of colour. His 1672 paper on the nature of white light and colours forms the basis for all work that followed on colour and colour vision.

From this work, he concluded that the lens of any

From this work, he concluded that the lens of any refracting telescope

A refracting telescope (also called a refractor) is a type of optical telescope that uses a lens (optics), lens as its objective (optics), objective to form an image (also referred to a dioptrics, dioptric telescope). The refracting telescope d ...

would suffer from the dispersion

Dispersion may refer to:

Economics and finance

*Dispersion (finance), a measure for the statistical distribution of portfolio returns

* Price dispersion, a variation in prices across sellers of the same item

*Wage dispersion, the amount of variat ...

of light into colours (chromatic aberration

In optics, chromatic aberration (CA), also called chromatic distortion, color aberration, color fringing, or purple fringing, is a failure of a lens to focus all colors to the same point. It is caused by dispersion: the refractive index of the ...

). As a proof of the concept, he constructed a telescope using reflective mirrors instead of lenses as the objective

Objective may refer to:

* Objectivity, the quality of being confirmed independently of a mind.

* Objective (optics), an element in a camera or microscope

* ''The Objective'', a 2008 science fiction horror film

* Objective pronoun, a personal pron ...

to bypass that problem. Building the design, the first known functional reflecting telescope, today known as a Newtonian telescope

The Newtonian telescope, also called the Newtonian reflector or just a Newtonian, is a type of reflecting telescope invented by the English scientist Sir Isaac Newton, using a concave primary mirror and a flat diagonal secondary mirror. Newto ...

, involved solving the problem of a suitable mirror material and shaping technique. He grounded his own mirrors out of a custom composition of highly reflective speculum metal

Speculum metal is a mixture of around two-thirds copper and one-third tin, making a white brittle alloy that can be polished to make a highly reflective surface. It was used historically to make different kinds of mirrors from personal grooming a ...

, using Newton's rings to judge the quality

Quality may refer to:

Concepts

*Quality (business), the ''non-inferiority'' or ''superiority'' of something

*Quality (philosophy), an attribute or a property

*Quality (physics), in response theory

*Energy quality, used in various science discipli ...

of the optics for his telescopes. In late 1668, he was able to produce this first reflecting telescope. It was about eight inches long and it gave a clearer and larger image. In 1671, he was asked for a demonstration of his reflecting telescope by the Royal Society. Their interest encouraged him to publish his notes, ''Of Colours'', which he later expanded into the work ''Opticks

''Opticks: or, A Treatise of the Reflexions, Refractions, Inflexions and Colours of Light'' is a collection of three books by Isaac Newton that was published in English language, English in 1704 (a scholarly Latin translation appeared in 1706). ...

''. When Robert Hooke

Robert Hooke (; 18 July 16353 March 1703) was an English polymath who was active as a physicist ("natural philosopher"), astronomer, geologist, meteorologist, and architect. He is credited as one of the first scientists to investigate living ...

criticised some of Newton's ideas, Newton was so offended that he withdrew from public debate. However, the two had brief exchanges in 1679–80, when Hooke, who had been appointed Secretary of the Royal Society, opened a correspondence intended to elicit contributions from Newton to Royal Society transactions, which had the effect of stimulating Newton to work out a proof that the elliptical form of planetary orbits would result from a centripetal force inversely proportional to the square of the radius vector.

Newton argued that light is composed of particles or corpuscles, which were refracted by accelerating into a denser medium. He verged on soundlike waves to explain the repeated pattern of reflection and transmission by thin films (''Opticks'' Bk. II, Props. 12), but still retained his theory of 'fits' that disposed corpuscles to be reflected or transmitted (Props.13). Physicists later favoured a purely wavelike explanation of light to account for the

Newton argued that light is composed of particles or corpuscles, which were refracted by accelerating into a denser medium. He verged on soundlike waves to explain the repeated pattern of reflection and transmission by thin films (''Opticks'' Bk. II, Props. 12), but still retained his theory of 'fits' that disposed corpuscles to be reflected or transmitted (Props.13). Physicists later favoured a purely wavelike explanation of light to account for the interference

Interference is the act of interfering, invading, or poaching. Interference may also refer to:

Communications

* Interference (communication), anything which alters, modifies, or disrupts a message

* Adjacent-channel interference, caused by extra ...

patterns and the general phenomenon of diffraction

Diffraction is the deviation of waves from straight-line propagation without any change in their energy due to an obstacle or through an aperture. The diffracting object or aperture effectively becomes a secondary source of the Wave propagation ...

. Despite his known preference of a particle theory, Newton in fact noted that light had both particle-like and wave-like properties in ''Opticks'', and was the first to attempt to reconcile the two theories, thereby anticipating later developments of wave-particle duality, which is the modern understanding of light. Physicist David Finkelstein

David Ritz Finkelstein (July 19, 1929 – January 24, 2016) was an emeritus professor of physics at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Biography

Born in New York City, Finkelstein obtained his Ph.D. in physics at the Massachusetts Institute o ...

called him "the first quantum physicist" as a result.

In his ''Hypothesis of Light'' of 1675, Newton posited the existence of the ether

In organic chemistry, ethers are a class of compounds that contain an ether group, a single oxygen atom bonded to two separate carbon atoms, each part of an organyl group (e.g., alkyl or aryl). They have the general formula , where R and R� ...

to transmit forces between particles. The contact with the Cambridge Platonist

The Cambridge Platonists were an influential group of Platonist philosophers and Christian theologians at the University of Cambridge that existed during the 17th century. The leading figures were Ralph Cudworth and Henry More.

Group and its nam ...

philosopher Henry More

Henry More (; 12 October 1614 – 1 September 1687) was an English philosopher of the Cambridge Platonists, Cambridge Platonist school.

Biography

Henry was born in Grantham, Grantham, Lincolnshire on 12 October 1614. He was the seventh son of ...

revived his interest in alchemy. He replaced the ether with occult forces based on Hermetic ideas of attraction and repulsion between particles. His contributions to science cannot be isolated from his interest in alchemy. This was at a time when there was no clear distinction between alchemy and science.

In 1704, Newton published ''Opticks'', in which he expounded his corpuscular theory of light, and included a set of queries at the end, which were posed as unanswered questions and positive assertions. In line with his corpuscle theory, he thought that normal matter was made of grosser corpuscles and speculated that through a kind of alchemical transmutation, with query 30 stating "Are not gross Bodies and Light convertible into one another, and may not Bodies receive much of their Activity from the Particles of Light which enter their Composition?" Query 6 introduced the concept of a black body

A black body or blackbody is an idealized physical body that absorbs all incident electromagnetic radiation, regardless of frequency or angle of incidence. The radiation emitted by a black body in thermal equilibrium with its environment is ...

.

Newton investigated electricity

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter possessing an electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as described by Maxwel ...

by constructing a primitive form of a frictional electrostatic generator

An electrostatic generator, or electrostatic machine, is an electric generator, electrical generator that produces ''static electricity'', or electricity at high voltage and low continuous current. The knowledge of static electricity dates back t ...

using a glass globe, and detailed an experiment in 1675 that showed when one side of a glass sheet is rubbed to create an electric charge, it attracts "light bodies" to the opposite side. He interpreted this as evidence that electric forces could pass through glass. His idea in ''Opticks'' that optical reflection Reflection or reflexion may refer to:

Science and technology

* Reflection (physics), a common wave phenomenon

** Specular reflection, mirror-like reflection of waves from a surface

*** Mirror image, a reflection in a mirror or in water

** Diffuse r ...

and refraction

In physics, refraction is the redirection of a wave as it passes from one transmission medium, medium to another. The redirection can be caused by the wave's change in speed or by a change in the medium. Refraction of light is the most commo ...

arise from interactions across the entire surface is regarded as the beginning of the field theory of electric force. He recognized the crucial role of electricity in nature, believing it to be responsible for various phenomena, including the emission, reflection, refraction, inflection, and heating effects of light. He proposed that electricity was involved in the sensations experienced by the human body, affecting everything from muscle movement to brain function. His mass-dispersion model, ancestral to the successful use of the least action principle

Action principles lie at the heart of fundamental physics, from classical mechanics through quantum mechanics, particle physics, and general relativity. Action principles start with an energy function called a Lagrangian describing the physical sy ...

, provided a credible framework for understanding refraction, particularly in its approach to refraction in terms of momentum.

In ''Opticks'', he was the first to show a diagram using a prism as a beam expander, and also the use of multiple-prism arrays. Some 278 years after Newton's discussion, multiple-prism beam expanders became central to the development of narrow-linewidth tunable laser

A tunable laser is a laser whose wavelength of operation can be altered in a controlled manner. While all active laser medium, laser gain media allow small shifts in output wavelength, only a few types of lasers allow continuous tuning over a sign ...

s. The use of these prismatic beam expanders led to the multiple-prism dispersion theory

The first description of multiple-prism arrays, and multiple-prism dispersion, was given by Isaac Newton in his book '' Opticks,'' also introducing prisms as beam expanders. Prism pair expanders were introduced by David Brewster in 1813. A modern ...

.

Newton was also the first to propose the Goos–Hänchen effect

The Goos–Hänchen effect, named after Hermann Fritz Gustav Goos (1883–1968) and Hilda Hänchen (1919–2013), but first suggested by Isaac Newton (1643–1727), is an optical phenomenon in which linearly polarized light undergoes a ...

, an optical phenomenon

Optical phenomena are any observable events that result from the interaction of light and matter.

All optical phenomena coincide with quantum phenomena. Common optical phenomena are often due to the interaction of light from the Sun or Moon with ...

in which linearly polarized

In electrodynamics, linear polarization or plane polarization of electromagnetic radiation is a confinement of the electric field vector or magnetic field vector to a given plane along the direction of propagation. The term ''linear polarizati ...

light undergoes a small lateral shift when totally internally reflected. He provided both experimental and theoretical explanations for the effect using a mechanical model.

Science came to realise the difference between perception of colour and mathematisable optics. The German poet and scientist, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Johann Wolfgang (von) Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German polymath who is widely regarded as the most influential writer in the German language. His work has had a wide-ranging influence on Western literature, literary, Polit ...

, could not shake the Newtonian foundation but "one hole Goethe did find in Newton's armour, ... Newton had committed himself to the doctrine that refraction without colour was impossible. He, therefore, thought that the object-glasses of telescopes must forever remain imperfect, achromatism and refraction being incompatible. This inference was proved by Dollond to be wrong."

Gravity

Newton had been developing his theory of gravitation as far back as 1665. In 1679, he returned to his work oncelestial mechanics

Celestial mechanics is the branch of astronomy that deals with the motions of objects in outer space. Historically, celestial mechanics applies principles of physics (classical mechanics) to astronomical objects, such as stars and planets, to ...

by considering gravitation and its effect on the orbits of planet

A planet is a large, Hydrostatic equilibrium, rounded Astronomical object, astronomical body that is generally required to be in orbit around a star, stellar remnant, or brown dwarf, and is not one itself. The Solar System has eight planets b ...

s with reference to Kepler's laws

In astronomy, Kepler's laws of planetary motion, published by Johannes Kepler in 1609 (except the third law, which was fully published in 1619), describe the orbits of planets around the Sun. These laws replaced circular orbits and epicycles in ...

of planetary motion. Newton's reawakening interest in astronomical matters received further stimulus by the appearance of a comet in the winter of 1680–1681, on which he corresponded with John Flamsteed

John Flamsteed (19 August 1646 – 31 December 1719) was an English astronomer and the first Astronomer Royal. His main achievements were the preparation of a 3,000-star catalogue, ''Catalogus Britannicus'', and a star atlas called '' Atlas ...

. After the exchanges with Hooke, Newton worked out a proof that the elliptical form of planetary orbits would result from a centripetal force inversely proportional to the square of the radius vector. He shared his results with Edmond Halley

Edmond (or Edmund) Halley (; – ) was an English astronomer, mathematician and physicist. He was the second Astronomer Royal in Britain, succeeding John Flamsteed in 1720.

From an observatory he constructed on Saint Helena in 1676–77, Hal ...

and the Royal Society in , a tract written on about nine sheets which was copied into the Royal Society's Register Book in December 1684. This tract contained the nucleus that Newton developed and expanded to form the ''Principia''.

The was published on 5 July 1687 with encouragement and financial help from Halley. In this work, Newton stated the three universal laws of motion. Together, these laws describe the relationship between any object, the forces acting upon it and the resulting motion, laying the foundation for classical mechanics

Classical mechanics is a Theoretical physics, physical theory describing the motion of objects such as projectiles, parts of Machine (mechanical), machinery, spacecraft, planets, stars, and galaxies. The development of classical mechanics inv ...

. They contributed to numerous advances during the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

and were not improved upon for more than 200 years. Many of these advances still underpin non-relativistic technologies today. Newton used the Latin word ''gravitas'' (weight) for the effect that would become known as gravity

In physics, gravity (), also known as gravitation or a gravitational interaction, is a fundamental interaction, a mutual attraction between all massive particles. On Earth, gravity takes a slightly different meaning: the observed force b ...

, and defined the law of universal gravitation

Newton's law of universal gravitation describes gravity as a force by stating that every particle attracts every other particle in the universe with a force that is Proportionality (mathematics)#Direct proportionality, proportional to the product ...

. His work achieved the first great unification in physics. He solved the two-body problem

In classical mechanics, the two-body problem is to calculate and predict the motion of two massive bodies that are orbiting each other in space. The problem assumes that the two bodies are point particles that interact only with one another; th ...

, and introduced the three-body problem

In physics, specifically classical mechanics, the three-body problem is to take the initial positions and velocities (or momenta) of three point masses orbiting each other in space and then calculate their subsequent trajectories using Newton' ...

.

In the same work, Newton presented a calculus-like method of geometrical analysis using 'first and last ratios', gave the first analytical determination (based on Boyle's law

Boyle's law, also referred to as the Boyle–Mariotte law or Mariotte's law (especially in France), is an empirical gas laws, gas law that describes the relationship between pressure and volume of a confined gas. Boyle's law has been stated as:

...

) of the speed of sound in air, inferred the oblateness of Earth's spheroidal figure, accounted for the precession of the equinoxes as a result of the Moon's gravitational attraction on the Earth's oblateness, initiated the gravitational study of the irregularities in the motion of the Moon

Lunar theory attempts to account for the motions of the Moon. There are many small variations (or perturbations) in the Moon's motion, and many attempts have been made to account for them. After centuries of being problematic, lunar motion can now ...

, provided a theory for the determination of the orbits of comets, and much more. Newton's biographer David Brewster

Sir David Brewster Knight of the Royal Guelphic Order, KH President of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, PRSE Fellow of the Royal Society of London, FRS Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, FSA Scot Fellow of the Scottish Society of ...

reported that the complexity of applying his theory of gravity to the motion of the moon was so great it affected Newton's health: " was deprived of his appetite and sleep" during his work on the problem in 1692–93, and told the astronomer John Machin

John Machin (bapt. c. 1686 – June 9, 1751)Anita McConnell, ‘Machin, John (bap. 1686?, died 1751)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004. Accessed 26 June 2007. was a professor of astronomy at Gresham ...

that "his head never ached but when he was studying the subject". According to Brewster, Halley also told John Conduitt

John Conduitt (; c. 8 March 1688 – 23 May 1737), of Cranbury Park, Hampshire, was a British landowner and Whig politician. He sat in the House of Commons from 1721 to 1737. He was married to the half-niece of Sir Isaac Newton, whom Conduitt ...

that when pressed to complete his analysis Newton "always replied that it made his head ache, and ''kept him awake so often, that he would think of it no more''". mphasis in originalHe provided the first calculation of the age of Earth

The age of Earth is estimated to be 4.54 ± 0.05 billion years. This age may represent the age of Earth's accretion, or core formation, or of the material from which Earth formed. This dating is based on evidence from radiometric age-dating of ...

by experiment, and described a precursor to the modern wind tunnel

A wind tunnel is "an apparatus for producing a controlled stream of air for conducting aerodynamic experiments". The experiment is conducted in the test section of the wind tunnel and a complete tunnel configuration includes air ducting to and f ...

.

Newton made clear his heliocentric

Heliocentrism (also known as the heliocentric model) is a Superseded theories in science#Astronomy and cosmology, superseded astronomical model in which the Earth and Solar System, planets orbit around the Sun at the center of the universe. His ...

view of the Solar System—developed in a somewhat modern way because already in the mid-1680s he recognised the "deviation of the Sun" from the centre of gravity of the Solar System. For Newton, it was not precisely the centre of the Sun or any other body that could be considered at rest, but rather "the common centre of gravity of the Earth, the Sun and all the Planets is to be esteem'd the Centre of the World", and this centre of gravity "either is at rest or moves uniformly forward in a right line". (Newton adopted the "at rest" alternative in view of common consent that the centre, wherever it was, was at rest.)

Newton was criticised for introducing "occult

The occult () is a category of esoteric or supernatural beliefs and practices which generally fall outside the scope of organized religion and science, encompassing phenomena involving a 'hidden' or 'secret' agency, such as magic and mysti ...

agencies" into science because of his postulate of an invisible force able to act over vast distances. Later, in the second edition of the ''Principia'' (1713), Newton firmly rejected such criticisms in a concluding General Scholium

The General Scholium () is an essay written by Isaac Newton, appended to his work of ''Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica'', known as the ''Principia''. It was first published with the second (1713) edition of the ''Principia'' and rea ...

, writing that it was enough that the phenomenon implied a gravitational attraction, as they did; but they did not so far indicate its cause, and it was both unnecessary and improper to frame hypotheses of things that were not implied by the phenomenon. (Here he used what became his famous expression .)

With the , Newton became internationally recognised. He acquired a circle of admirers, including the Swiss-born mathematician Nicolas Fatio de Duillier

Nicolas Fatio de Duillier (also spelled Faccio or Facio; 16 February 1664 – 10 May 1753) was a mathematician, Natural philosophy, natural philosopher, astronomer, inventor, and religious campaigner. Born in Basel, Switzerland, Fatio mostly ...

.