The Call Of The Wild (Service) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''The Call of the Wild'' is an adventure novel by

California native

California native  In the spring, as the annual gold stampeders began to stream in, London left. He had contracted

In the spring, as the annual gold stampeders began to stream in, London left. He had contracted

The 100 best novels: No 35 – The Call of the Wild by Jack London (1903)

"The 100 best novels: No 35 – ''The Call of the Wild'' by Jack London (1903)". ''The Guardian''. 19 May 2014. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

Jack London

John Griffith London (; January 12, 1876 – November 22, 1916), better known as Jack London, was an American novelist, journalist and activist. A pioneer of commercial fiction and American magazines, he was one of the first American authors t ...

, published in 1903 and set in Yukon

Yukon () is a Provinces and territories of Canada, territory of Canada, bordering British Columbia to the south, the Northwest Territories to the east, the Beaufort Sea to the north, and the U.S. state of Alaska to the west. It is Canada’s we ...

, Canada, during the 1890s Klondike Gold Rush, when strong sled dog

A sled dog is a dog trained and used to pull a land vehicle in Dog harness, harness, most commonly a Dog sled, sled over snow.

Sled dogs have been used in the Arctic for at least 8,000 years and, along with watercraft, were the only transpor ...

s were in high demand. The central character of the novel is a dog named Buck. The story opens at a ranch in Santa Clara Valley

The Santa Clara Valley (Spanish language, Spanish: ''Valle de Santa Clara'') is a geologic trough in Northern California that extends south–southeast from San Francisco to Hollister, California, Hollister. The longitudinal valley is bordered ...

, California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

, when Buck is stolen from his home and sold into service as a sled dog in Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

. He becomes progressively more primitive and wild in the harsh environment, where he is forced to fight to survive and dominate other dogs. By the end, he sheds the veneer of civilization, and relies on primordial instinct and learned experience to emerge as a leader in the wild.

London spent about a year in Yukon, and his observations form much of the material for the book. The story was serialized in ''The Saturday Evening Post

''The Saturday Evening Post'' is an American magazine published six times a year. It was published weekly from 1897 until 1963, and then every other week until 1969. From the 1920s to the 1960s, it was one of the most widely circulated and influ ...

'' in the summer of 1903 and was published later that year in book form. The book's great popularity and success made a reputation for London. As early as 1923, the story was adapted to film, and it has since seen several more cinematic adaptations.

One of the more notable earlier films was filmed in 1935, starring Clark Gable

William Clark Gable (February 1, 1901November 16, 1960) was an American actor often referred to as the "King of Cinema of the United States, Hollywood". He appeared in more than 60 Film, motion pictures across a variety of Film genre, genres dur ...

and Loretta Young

Loretta Young (born Gretchen Michaela Young; January 6, 1913 – August 12, 2000) was an American actress. Starting as a child, she had a long and varied career in film from 1917 to 1989. She received numerous honors including an Academy Awards ...

, as well as Frank Conroy and Jack Oakie

Jack Oakie (born Lewis Delaney Offield; November 12, 1903 – January 23, 1978) was an American actor, starring mostly in films, but also working on stage, radio and television. He portrayed Napaloni in Chaplin's ''The Great Dictator'' (1940) ...

. Considerable liberties were taken with the story line.

Summary

The story opens in 1897 with Buck, a powerful 140-pound St. Bernard– Scotch Shepherd mix, happily living inCalifornia

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

's Santa Clara Valley

The Santa Clara Valley (Spanish language, Spanish: ''Valle de Santa Clara'') is a geologic trough in Northern California that extends south–southeast from San Francisco to Hollister, California, Hollister. The longitudinal valley is bordered ...

as the pampered pet of Judge Miller and his family. One night, assistant gardener Manuel, needing money to pay off gambling debts, steals Buck and sells him to a stranger. Buck is shipped to Seattle

Seattle ( ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Washington and in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. With a population of 780,995 in 2024, it is the 18th-most populous city in the United States. The city is the cou ...

, where he is

confined in a crate, starved, and ill-treated. When released, Buck attacks his handler, the "man in the red sweater" who teaches Buck the "law of club and fang", sufficiently cowing him. The man shows some kindness after Buck demonstrates obedience.

Shortly after, Buck is sold to two French-Canadian

French Canadians, referred to as Canadiens mainly before the nineteenth century, are an ethnic group descended from French colonists first arriving in France's colony of Canada in 1608. The vast majority of French Canadians live in the prov ...

dispatchers from the Canadian government, François and Perrault, who take him to Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

. Buck is trained as a sled dog

A sled dog is a dog trained and used to pull a land vehicle in Dog harness, harness, most commonly a Dog sled, sled over snow.

Sled dogs have been used in the Arctic for at least 8,000 years and, along with watercraft, were the only transpor ...

for the Klondike region of Canada. In addition to Buck, François and Perrault have ten dogs on their team. Buck's teammates teach him how to survive cold winter nights and about pack society. Over the next several weeks on the trail, a bitter rivalry develops between Buck and the lead dog, Spitz, a vicious and quarrelsome white husky

Husky is a general term for a type of dog used in the polar regions, primarily and specifically for work as sled dogs. It refers to a traditional northern type, notable for its cold-weather tolerance and overall hardiness. Modern racing huskies ...

. Buck eventually kills Spitz in a fight and becomes the new lead dog.

When François and Perrault complete the round-trip of the Yukon Trail in record time, returning to Skagway

The Municipality and Borough of Skagway is a borough in Alaska on the Alaska Panhandle. As of the 2020 census, the population was 1,240, up from 968 in 2010. The population doubles in the summer tourist season in order to deal with the large ...

with their dispatches, they are given new orders from the Canadian government. They sell their sled team to a "Scotch half-breed" man, who works in the mail service. The dogs must make long, tiring trips, carrying heavy loads to the mining areas. While running the trail, Buck seems to have memories of a canine ancestor who has a short-legged hairy man as a companion. Meanwhile, the weary animals become weak from the hard labor, and the wheel dog, Dave, a morose husky, becomes terminally sick and is eventually shot

Shot may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Shot'' (album), by The Jesus Lizard

*''Shot, Illusion, New God'', an EP by Gruntruck

*'' Shot Rev 2.0'', a video album by The Sisters of Mercy

* "Shot" (song), by The Rasmus

* ''Shot'' (2017 ...

.

With the dogs too exhausted and footsore to be of use, the mail carrier sells them to three stampeders from the American Southland (the present-day contiguous United States

The contiguous United States, also known as the U.S. mainland, officially referred to as the conterminous United States, consists of the 48 adjoining U.S. states and the District of Columbia of the United States in central North America. The te ...

)—a vain woman named Mercedes, her sheepish husband Charles, and her arrogant brother Hal. They lack survival skills for the Northern wilderness, struggle to control the sled, and ignore others' helpful advice—particularly warnings about the dangerous spring melt. When told her sled is too heavy, Mercedes dumps out crucial supplies in favor of fashion objects. She and Hal foolishly create a team of 14 dogs, believing they will travel faster. The dogs are overfed and overworked, then starved when food runs low. Most of the dogs die on the trail, leaving only Buck and four other dogs when they pull into the White River.

The group meets John Thornton, an experienced outdoorsman, who notices the dogs' poor condition. The trio ignores Thornton's warnings about crossing the ice and press onward. Exhausted, starving, and sensing the danger ahead, Buck refuses to continue. After Hal whips Buck mercilessly, Thornton hits him and cuts Buck free. The group presses onward with the four remaining dogs, but their weight causes the ice to break and the dogs and humans (along with their sled) to fall into the river and drown.

As Thornton nurses Buck back to health, Buck grows to love him. Buck fends off a malicious man named Burton who hit Thornton while the latter was defending an innocent "tenderfoot." This gives Buck a reputation all over the North. Buck also saves Thornton when he falls into a river. After Thornton takes him on trips to pan for gold, a man called Matthewson wagers Thornton on Buck's strength and devotion. Buck pulls a sled with a half-ton () load of flour, breaking it free from the frozen ground, dragging it , and winning Thornton US$1,600 ().

Using his winnings, Thornton pays his debts and continues searching for gold with partners Pete and Hans, sledding Buck and six other dogs to search for a fabled Lost Cabin. Once they locate a suitable gold find, the dogs find they have nothing to do. Buck has more ancestor memories of being with the primitive "hairy man." While Thornton and his two friends pan gold, Buck hears the call of the wild, explores the wilderness, and socializes with a wolf from a local pack. However, Buck does not join the wolves and returns to Thornton. Buck repeatedly goes back and forth between Thornton and the wild, unsure of where he belongs. Returning to the campsite one day, he finds Hans, Pete, and Thornton along with their dogs have been murdered by Native American

Native Americans or Native American usually refers to Native Americans in the United States.

Related terms and peoples include:

Ethnic groups

* Indigenous peoples of the Americas, the pre-Columbian peoples of North, South, and Central America ...

Yeehats. Enraged, Buck kills several Natives to avenge Thornton, then realizes he no longer has any human ties left. He goes looking for his wild brother and encounters a hostile wolf pack. He fights them and wins, then discovers that the lone wolf he had socialized with is a pack member. Buck follows the pack into the forest and answers the call of the wild.

The legend of Buck spreads among other Native Americans as the "Ghost Dog" of the Northland (Alaska and northwestern Canada). Each year, on the anniversary of his attack on the Yeehats, Buck returns to the former campsite where he was last with Thornton to mourn his death. Every winter, leading the wolf pack, Buck wreaks vengeance on the Yeehats "as he sings a song of the younger world, which is the song of the pack."

Background

California native

California native Jack London

John Griffith London (; January 12, 1876 – November 22, 1916), better known as Jack London, was an American novelist, journalist and activist. A pioneer of commercial fiction and American magazines, he was one of the first American authors t ...

had traveled around the United States as a hobo

A hobo is a migrant worker in the United States. Hoboes, tramps, and bums are generally regarded as related, but distinct: a hobo travels and is willing to work; a tramp travels, but avoids work if possible; a bum neither travels nor works.

Et ...

, returned to California to finish high school (he dropped out at age 14), and spent a year in college at Berkeley

Berkeley most often refers to:

*Berkeley, California, a city in the United States

**University of California, Berkeley, a public university in Berkeley, California

*George Berkeley (1685–1753), Anglo-Irish philosopher

Berkeley may also refer to ...

, when in 1897 he went to the Klondike by way of Alaska during the height of the Klondike Gold Rush. Later, he said of the experience: "It was in the Klondike I found myself."

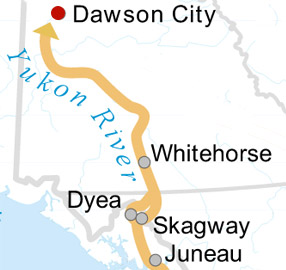

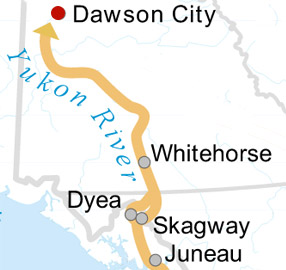

He left California in July and traveled by boat to Dyea, Alaska

Dyea ( ) is a ghost town in the U.S. state of Alaska. A few people live on individual small homesteads in the valley; however, it is largely abandoned. It is located at the convergence of the Taiya River and Taiya Inlet on the south side of the ...

, where he landed and went inland. To reach the goldfields, he and his party transported their gear over the Chilkoot Pass

Chilkoot Pass (el. ) is a high mountain pass through the Boundary Ranges of the Coast Mountains in the U.S. state of Alaska and British Columbia, Canada. It is the highest point along the Chilkoot Trail that leads from Dyea, Alaska to Bennett ...

, often carrying loads as heavy as on their backs. They were successful in staking claims to eight gold mines along the Stewart River.

London stayed in the Klondike for almost a year, living temporarily in the frontier town of Dawson City

Dawson City is a town in the Canadian territory of Yukon. It is inseparably linked to the Klondike Gold Rush (1896–1899). Its population was 1,577 as of the 2021 census, making it the second-largest municipality in Yukon.

History

Prior t ...

, before moving to a nearby winter camp, where he spent the winter in a temporary shelter reading books he had brought: Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

's ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life'')The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by M ...

'' and John Milton

John Milton (9 December 1608 – 8 November 1674) was an English poet, polemicist, and civil servant. His 1667 epic poem ''Paradise Lost'' was written in blank verse and included 12 books, written in a time of immense religious flux and politic ...

's ''Paradise Lost

''Paradise Lost'' is an Epic poetry, epic poem in blank verse by the English poet John Milton (1608–1674). The poem concerns the Bible, biblical story of the fall of man: the temptation of Adam and Eve by the fallen angel Satan and their ex ...

''. In the winter of 1898, Dawson City was a city comprising about 30,000 miners, a saloon, an opera house, and a street of brothels.

In the spring, as the annual gold stampeders began to stream in, London left. He had contracted

In the spring, as the annual gold stampeders began to stream in, London left. He had contracted scurvy

Scurvy is a deficiency disease (state of malnutrition) resulting from a lack of vitamin C (ascorbic acid). Early symptoms of deficiency include weakness, fatigue, and sore arms and legs. Without treatment, anemia, decreased red blood cells, gum d ...

, common in the Arctic winters where fresh produce was unavailable. When his gums began to swell he decided to return to California. With his companions, he rafted down the Yukon River

The Yukon River is a major watercourse of northwestern North America. From its source in British Columbia, it flows through Canada's territory of Yukon (itself named after the river). The lower half of the river continues westward through the U.S ...

, through portions of the wildest territory in the region, until they reached St. Michael

Michael, also called Saint Michael the Archangel, Archangel Michael and Saint Michael the Taxiarch is an archangel and the warrior of God in Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. The earliest surviving mentions of his name are in third- and second- ...

. There, he hired himself out on a boat to earn return passage to San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

.

In Alaska, London found the material that inspired him to write ''The Call of the Wild''. Dyea Beach was the primary point of arrival for miners when London traveled through there, but because its access was treacherous Skagway

The Municipality and Borough of Skagway is a borough in Alaska on the Alaska Panhandle. As of the 2020 census, the population was 1,240, up from 968 in 2010. The population doubles in the summer tourist season in order to deal with the large ...

soon became the new arrival point for prospectors. To reach the Klondike, miners had to navigate White Pass

White Pass, also known as the Dead Horse Trail (elevation ), is a mountain pass through the Boundary Ranges of the Coast Mountains on the border of the U.S. state of Alaska and the province of British Columbia, Canada. It leads from Skagway, Ala ...

, known as "Dead Horse Pass", where horse carcasses littered the route because they could not survive the harsh and steep ascent. Horses were replaced with dogs as pack animals to transport material over the pass; particularly strong dogs with thick fur were "much desired, scarce and high in price".

London would have seen many dogs, especially prized husky

Husky is a general term for a type of dog used in the polar regions, primarily and specifically for work as sled dogs. It refers to a traditional northern type, notable for its cold-weather tolerance and overall hardiness. Modern racing huskies ...

sled dogs, in Dawson City and the winter camps situated close to the main sled route. He was friends with Marshall Latham Bond

Marshall Latham Bond was one of two brothers who were Jack London's landlords and among his employers during the autumn of 1897 and the spring of 1898 during the Klondike Gold Rush. They were the owners of the dog that London fictionalized as Bu ...

and his brother Louis Whitford Bond, the owners of a mixed St. Bernard-Scotch Collie

The Rough Collie (also known as the Long-Haired Collie) is a long-coated dog breed of medium to large size that, in its original form, was a type of collie used and bred for Herding dog, herding sheep in Scotland. More recent breeding has focus ...

dog about which London later wrote: "Yes, Buck is based on your dog at Dawson." Beinecke Library

The Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library () is the rare book library and literary archive of the Yale University Library in New Haven, Connecticut. It is one of the largest buildings in the world dedicated to rare books and manuscripts and ...

at Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Stat ...

holds a photograph of Bond's dog, taken during London's stay in the Klondike in 1897. The depiction of the California ranch

A ranch (from /Mexican Spanish) is an area of landscape, land, including various structures, given primarily to ranching, the practice of raising grazing livestock such as cattle and sheep. It is a subtype of farm. These terms are most often ap ...

at the beginning of the story was based on the Bond family ranch.

Publication history

On his return to California, London was unable to find work and relied on odd jobs such as cutting grass. He submitted a query letter to the San Francisco ''Bulletin'' proposing a story about his Alaskan adventure, but the idea was rejected because, as the editor told him, "Interest in Alaska has subsided to an amazing degree." A few years later, London wrote a short story about a dog named Bâtard who, at the end of the story, kills his master. London sold the piece to ''Cosmopolitan Magazine

''Cosmopolitan'' (stylized in all caps) is an American quarterly fashion and entertainment magazine for women, first published based in New York City in March 1886 as a family magazine; it was later transformed into a literary magazine and, sinc ...

'', which published it in the June 1902 issue under the title "Diablo – A Dog". London's biographer, Earle Labor

Earle Gene Labor (March 3, 1928 – September 15, 2022) was an American writer. A George Wilson Professor (Emeritus) of American Literature at Centenary College of Louisiana, his research and teaching career was devoted to the study of the Ameri ...

, says that London then began work on ''The Call of the Wild'' to "redeem the species" from his dark characterization of dogs in "Bâtard". Expecting to write a short story, London explains: "I meant it to be a companion to my other dog story 'Bâtard' ... but it got away from me, and instead of 4,000 words it ran 32,000 before I could call a halt."

Written as a frontier story about the gold rush, ''The Call of the Wild'' was meant for the pulp

Pulp may refer to:

* Pulp (fruit), the inner flesh of fruit

* Pulp (band), an English rock band

Engineering

* Pulp (paper), the fibrous material used to make paper

* Dissolving pulp, highly purified cellulose used in fibre and film manufacture

...

market. It was first published in five installments in ''The Saturday Evening Post'', which bought it for $750 in 1903 (~$ in ). In the same year, London sold all rights to the story to Macmillan, which published it in book format. The book has never been out of print since that time.

Editions

* The first edition, by Macmillan, released in August 1903, had 10 tipped-in color plates by illustrators Philip R. Goodwin andCharles Livingston Bull

Charles Livingston Bull (1874–1932) was an American illustrator. Bull studied taxidermy in Rochester, New York and is known for his illustration of wildlife.

Career

Bull's first job at the age of 16 was preparing animals for mounting at the W ...

, and a color frontispiece by Charles Edward Hooper; it sold for $1.50. It is presently available with the original illustrations at the Internet Archive

The Internet Archive is an American 501(c)(3) organization, non-profit organization founded in 1996 by Brewster Kahle that runs a digital library website, archive.org. It provides free access to collections of digitized media including web ...

.

Genre

''The Call of the Wild'' falls into the categories ofadventure fiction

Adventure fiction is a type of fiction that usually presents danger, or gives the reader a sense of excitement. Some adventure fiction also satisfies the literary definition of Romance (prose fiction)#Definition, romance fiction.

History

In t ...

and what is sometimes referred to as the animal story genre, in which an author attempts to write an animal protagonist without resorting to anthropomorphism

Anthropomorphism is the attribution of human traits, emotions, or intentions to non-human entities. It is considered to be an innate tendency of human psychology. Personification is the related attribution of human form and characteristics t ...

. At the time, London was criticized for attributing "unnatural" human thoughts and insights to a dog, so much so that he was accused of being a nature faker

The nature fakers controversy was an early 20th-century American literary debate highlighting the conflict between science and sentiment in popular nature writing. The debate involved important American literary, environmental and political fig ...

. London himself dismissed these criticisms as " homocentric" and "amateur". London further responded that he had set out to portray nature more accurately than his predecessors.

Along with his contemporaries Frank Norris

Benjamin Franklin Norris Jr. (March 5, 1870 – October 25, 1902) was an American journalist and novelist during the Progressive Era, whose fiction was predominantly in the naturalism (literature), naturalist genre. His notable works include ''M ...

and Theodore Dreiser

Theodore Herman Albert Dreiser (; August 27, 1871 – December 28, 1945) was an American novelist and journalist of the naturalism (literature), naturalist school. His novels often featured main characters who succeeded at their objectives despi ...

, London was influenced by the naturalism of European writers such as Émile Zola

Émile Édouard Charles Antoine Zola (, ; ; 2 April 184029 September 1902) was a French novelist, journalist, playwright, the best-known practitioner of the literary school of Naturalism (literature), naturalism, and an important contributor to ...

, in which themes such as heredity versus environment were explored. London's use of the genre gave it a new vibrancy, according to scholar Richard Lehan.

The story is also an example of American pastoral

The pastoral genre of literature, art, or music depicts an idealised form of the shepherd's lifestyle – herding livestock around open areas of land according to the seasons and the changing availability of water and pasture. The target au ...

ism—a prevailing theme in American literature—in which the mythic hero returns to nature. As with other characters of American literature, such as Rip van Winkle

"Rip Van Winkle" () is a short story by the American author Washington Irving, first published in 1819. It follows a Dutch-American villager in Colonial history of the United States, colonial America named Rip Van Winkle who meets mysterious Du ...

and Huckleberry Finn

Huckleberry "Huck" Finn is a fictional character created by Mark Twain who first appeared in the book ''The Adventures of Tom Sawyer'' (1876) and is the protagonist and narrator of its sequel, '' Adventures of Huckleberry Finn'' (1884). He is 12 ...

, Buck symbolizes a reaction against industrialization and social convention with a return to nature. London presents the motif simply, clearly, and powerfully in the story, a motif later echoed by 20th-century American writers William Faulkner

William Cuthbert Faulkner (; September 25, 1897 – July 6, 1962) was an American writer. He is best known for William Faulkner bibliography, his novels and short stories set in the fictional Yoknapatawpha County, Mississippi, a stand-in fo ...

and Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway ( ; July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer and journalist. Known for an economical, understated style that influenced later 20th-century writers, he has been romanticized fo ...

(most notably in "Big Two-Hearted River

"Big Two-Hearted River" is a two-part short story written by American author Ernest Hemingway, published in the 1925 Boni & Liveright edition of ''In Our Time (short story collection), In Our Time'', the first American volume of Hemingway's sho ...

"). E.L. Doctorow says of the story that it is "fervently American".

The enduring appeal of the story, according to American literature scholar Donald Pizer

Donald Pizer (April 5, 1929 – November 7, 2023) was an American academic and literary critic who was regarded as one of the principal authorities on the American naturalism literary movement. He was the Pierce Butler Professor of English Emeri ...

, is that it is a combination of allegory

As a List of narrative techniques, literary device or artistic form, an allegory is a wikt:narrative, narrative or visual representation in which a character, place, or event can be interpreted to represent a meaning with moral or political signi ...

, parable

A parable is a succinct, didactic story, in prose or verse, that illustrates one or more instructive lessons or principles. It differs from a fable in that fables employ animals, plants, inanimate objects, or forces of nature as characters, whe ...

, and fable

Fable is a literary genre defined as a succinct fictional story, in prose or verse, that features animals, legendary creatures, plants, inanimate objects, or forces of nature that are anthropomorphized, and that illustrates or leads to a parti ...

. The story incorporates elements of age-old animal fables, such as ''Aesop's Fables

Aesop's Fables, or the Aesopica, is a collection of fables credited to Aesop, a Slavery in ancient Greece, slave and storyteller who lived in ancient Greece between 620 and 564 Before the Common Era, BCE. Of varied and unclear origins, the stor ...

,'' in which animals speak the truth, and traditional beast fables, in which the beast "substitutes wit for insight". London was influenced by Rudyard Kipling

Joseph Rudyard Kipling ( ; 30 December 1865 – 18 January 1936)''The Times'', (London) 18 January 1936, p. 12. was an English journalist, novelist, poet, and short-story writer. He was born in British Raj, British India, which inspired much ...

's ''The Jungle Book

''The Jungle Book'' is an 1894 collection of stories by the English author Rudyard Kipling. Most of the characters are animals such as Shere Khan the tiger and Baloo the bear, though a principal character is the boy or "man-cub" Mowgli, who ...

'', written a few years earlier, with its combination of parable and animal fable, and by other animal stories popular in the early 20th century. In ''The Call of the Wild'', London intensifies and adds layers of meaning that are lacking in these stories.

As a writer, London tended to skimp on form, according to biographer Labor, and neither ''The Call of the Wild'' nor ''White Fang

''White Fang'' is a novel by American author Jack London (1876–1916) about a wild wolfdog's journey to domestication in Yukon Territory and the Northwest Territories during the 1890s Klondike Gold Rush. First serialized in ''Outing'' magazin ...

'' "is a conventional novel". The story follows the archetypal " myth of the hero"; Buck, who is the hero, takes a journey, is transformed, and achieves an apotheosis

Apotheosis (, ), also called divinization or deification (), is the glorification of a subject to divine levels and, commonly, the treatment of a human being, any other living thing, or an abstract idea in the likeness of a deity.

The origina ...

. The format of the story is divided into four distinct parts, according to Labor. In the first part, Buck experiences violence and struggles for survival; in the second part, he proves himself a leader of the pack; the third part brings him to his death (symbolically and almost literally); and in the fourth and final part, he undergoes rebirth.

Themes

London's story is a tale of survival and a return toprimitivism

In the arts of the Western world, Primitivism is a mode of aesthetic idealization that means to recreate the experience of ''the primitive'' time, place, and person, either by emulation or by re-creation. In Western philosophy, Primitivism propo ...

. Pizer writes that: "the strong, the shrewd, and the cunning shall prevail when ...life is bestial".

Pizer also finds evidence in the story of a Christian theme of love and redemption, as shown by Buck's refusal to revert to violence until after the death of Thornton, who had won Buck's love and loyalty. London, who went so far as to fight for custody of one of his own dogs, understood that loyalty between dogs (particularly working dogs) and their masters is built on trust and love.

Writing in the "Introduction" to the Modern Library

The Modern Library is an American book publishing Imprint (trade name), imprint and formerly the parent company of Random House. Founded in 1917 by Albert Boni and Horace Liveright as an imprint of their publishing company Boni & Liveright, Moder ...

edition of ''The Call of the Wild'', E. L. Doctorow

Edgar Lawrence Doctorow (January 6, 1931 – July 21, 2015) was an American novelist, editor, and professor, best known for his works of historical fiction.

He wrote twelve novels, three volumes of short fiction and a stage drama, including the ...

says the theme is based on Darwin's concept of the survival of the fittest. London places Buck in conflict with humans, in conflict with the other dogs, and in conflict with his environment—all of which he must challenge, survive, and conquer. Buck, a domesticated dog, must call on his atavistic

In biology, an atavism is a modification of a biological traits structure or behavior whereby an ancestral genetic trait reappears after having been lost through evolutionary change in previous generations. Atavisms can occur in several ways, ...

hereditary traits to survive; he must learn to be wild to become wild, according to Tina Gianquitto. He learns that in a world where "the club and the fang" are law, where the law of the pack rules and a good-natured dog such as Curly can be torn to pieces by pack members, survival by whatever means is paramount.

London also explores the idea of "nature vs. nurture". Buck, raised as a pet, is by heredity a wolf. The change of environment brings up his innate characteristics and strengths to the point where he fights for survival and becomes the leader of the pack. Pizer describes how the story reflects human nature in its prevailing theme of strength, particularly in the face of harsh circumstances.

The veneer of civilization is thin and fragile, writes Doctorow, and London exposes the brutality at the core of humanity and the ease with which humans revert to a state of primitivism. His interest in Marxism

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflict, ...

is evident in the sub-theme that humanity is motivated by materialism, and his interest in Nietzschean

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) developed his philosophy during the late 19th century. He owed the awakening of his philosophical interest to reading Arthur Schopenhauer's ''Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung'' (''The World as Will and Represe ...

philosophy is shown by Buck's characterization. Gianquitto writes that in Buck's characterization, London created a type of Nietzschean Übermensch

The ( , ; 'Overman' or 'Superman') is a concept in the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche. In his 1883 book, '' Thus Spoke Zarathustra'' (), Nietzsche has his character Zarathustra posit the as a goal for humanity to set for itself. The repre ...

– in this case a dog that reaches mythic proportions.

Doctorow sees the story as a caricature of a ''bildungsroman

In literary criticism, a bildungsroman () is a literary genre that focuses on the psychological and moral growth and change of the protagonist from childhood to adulthood (coming of age). The term comes from the German words ('formation' or 'edu ...

'' – in which a character learns and grows – in that Buck becomes progressively less civilized. Gianquitto explains that Buck has evolved to the point that he is ready to join a wolf pack, which has a social structure uniquely adapted to and successful in the harsh Arctic environment, unlike humans, who are weak in the harsh environment.

Writing style

The first chapter opens with the first quatrain of John Myers O'Hara's poem, ''Atavism'', published in 1902 in '' The Bookman''. Thestanza

In poetry, a stanza (; from Italian ''stanza'', ; ) is a group of lines within a poem, usually set off from others by a blank line or indentation. Stanzas can have regular rhyme and metrical schemes, but they are not required to have either. ...

outlines one of the main motifs of ''The Call of the Wild'': that Buck when removed from the "sun-kissed" Santa Clara Valley

The Santa Clara Valley (Spanish language, Spanish: ''Valle de Santa Clara'') is a geologic trough in Northern California that extends south–southeast from San Francisco to Hollister, California, Hollister. The longitudinal valley is bordered ...

where he was raised, will revert to his wolf heritage with its innate instincts and characteristics.

The themes are conveyed through London's use of symbolism and imagery which, according to Labor, vary in the different phases of the story. The imagery and symbolism in the first phase, to do with the journey and self-discovery, depict physical violence, with strong images of pain and blood. In the second phase, fatigue becomes a dominant image and death is a dominant symbol, as Buck comes close to being killed. The third phase is a period of renewal and rebirth and takes place in the spring, before ending with the fourth phase, when Buck fully reverts to nature and is placed in a vast and "weird atmosphere", a place of pure emptiness.

The setting is allegorical. The southern lands represent the soft, materialistic world; the northern lands symbolize a world beyond civilization and are inherently competitive. The harshness, brutality, and emptiness in Alaska reduce life to its essence, as London learned, and it shows in Buck's story. Buck must defeat Spitz, the dog who symbolically tries to get ahead and take control. When Buck is sold to Charles, Hal, and Mercedes, he finds himself in a dirty camp. They treat their dogs badly; they are artificial interlopers in the pristine landscape. Conversely, Buck's next masters, John Thornton and his two companions are described as "living close to the earth". They keep a clean camp, treat their animals well, and represent man's nobility in nature. Unlike Buck, Thornton loses his fight with his fellow species, and not until Thornton's death does Buck revert fully to the wild and his primordial state.

The characters too are symbolic of types. Charles, Hal, and Mercedes symbolize vanity and ignorance, while Thornton and his companions represent loyalty, purity, and love. Much of the imagery is stark and simple, with an emphasis on images of cold, snow, ice, darkness, meat, and blood.

London varied his prose style to reflect the action. He wrote in an over-affected style in his descriptions of Charles, Hal, and Mercedes' camp as a reflection of their intrusion into the wilderness. Conversely, when describing Buck and his actions, London wrote in a style that was pared down and simple—a style that would influence and be the forebear of Hemingway's style.

The story was written as a frontier adventure and in such a way that it worked well as a serial. As Doctorow points out, it is good episodic writing that embodies the style of magazine adventure writing popular in that period. "It leaves us with satisfaction at its outcome, a story well and truly told," he said.

Reception and legacy

''The Call of the Wild'' was enormously popular from the moment it was published.H. L. Mencken

Henry Louis Mencken (September 12, 1880 – January 29, 1956) was an American journalist, essayist, satirist, cultural critic, and scholar of American English. He commented widely on the social scene, literature, music, prominent politicians, ...

wrote of London's story: "No other popular writer of his time did any better writing than you will find in ''The Call of the Wild''." A reviewer for ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' wrote of it in 1903: "If nothing else makes Mr. London's book popular, it ought to be rendered so by the complete way in which it will satisfy the love of dog fights apparently inherent in every man." The reviewer for ''The Atlantic Monthly

''The Atlantic'' is an American magazine and multi-platform publisher based in Washington, D.C. It features articles on politics, foreign affairs, business and the economy, culture and the arts, technology, and science.

It was founded in 1857 ...

'' wrote that it was a book: "untouched by bookishness...The making and the achievement of such a hero uckconstitute, not a pretty story at all, but a very powerful one."

The book secured London a place in the canon of American literature. The first printing of 10,000 copies sold out immediately; it is still one of the best-known stories written by an American author and continues to be read and taught in schools. It has been published in 47 languages. London's first success, the book secured his prospects as a writer and gained him a readership that stayed with him throughout his career.

After the success of ''The Call of the Wild'', London wrote to Macmillan in 1904 proposing a second book (''White Fang

''White Fang'' is a novel by American author Jack London (1876–1916) about a wild wolfdog's journey to domestication in Yukon Territory and the Northwest Territories during the 1890s Klondike Gold Rush. First serialized in ''Outing'' magazin ...

'') in which he wanted to describe the opposite of Buck: a dog that transforms from wild to tame: "I'm going to reverse the process...Instead of devolution of decivilization ... I'm going to give the evolution, the civilization of a dog."

Adaptations

* The 1923 adaptation asilent film

A silent film is a film without synchronized recorded sound (or more generally, no audible dialogue). Though silent films convey narrative and emotion visually, various plot elements (such as a setting or era) or key lines of dialogue may, w ...

written and directed by Fred Jackman

Fred Wood Jackman Sr. (July 9, 1881 – August 27, 1959), was an American cinematographer and film director of the silent era. He worked on 58 films as a cinematographer between 1916 and 1925. He also directed eleven films between 1919 and ...

and produced by Hal Roach

Harold Eugene "Hal" Roach Sr. Skretvedt, Randy (2016), ''Laurel and Hardy: The Magic Behind the Movies'', Bonaventure Press. p.608. (January 14, 1892 – November 2, 1992) was an American film and television producer, director and screenwriter, ...

.

* The 1935 version, starring Clark Gable

William Clark Gable (February 1, 1901November 16, 1960) was an American actor often referred to as the "King of Cinema of the United States, Hollywood". He appeared in more than 60 Film, motion pictures across a variety of Film genre, genres dur ...

and Loretta Young

Loretta Young (born Gretchen Michaela Young; January 6, 1913 – August 12, 2000) was an American actress. Starting as a child, she had a long and varied career in film from 1917 to 1989. She received numerous honors including an Academy Awards ...

, expanded John Thornton's role and was the first "talkie

A sound film is a motion picture with synchronized sound, or sound technologically coupled to image, as opposed to a silent film. The first known public exhibition of projected sound films took place in Paris in 1900, but decades passed befo ...

" to feature the story.

* The 1972 movie ''The Call of the Wild

''The Call of the Wild'' is an adventure novel by Jack London, published in 1903 and set in Yukon, Canada, during the 1890s Klondike Gold Rush, when strong sled dogs were in high demand. The central character of the novel is a dog named Buck. ...

'', starring Charlton Heston

Charlton Heston (born John Charles Carter; October 4, 1923 – April 5, 2008) was an American actor. He gained stardom for his leading man roles in numerous Cinema of the United States, Hollywood films including biblical epics, science-fiction f ...

as John Thornton, was filmed in Finland

Finland, officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It borders Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bothnia to the west and the Gulf of Finland to the south, ...

.

* The 1976 television film ''The Call of the Wild

''The Call of the Wild'' is an adventure novel by Jack London, published in 1903 and set in Yukon, Canada, during the 1890s Klondike Gold Rush, when strong sled dogs were in high demand. The central character of the novel is a dog named Buck. ...

'', starring John Beck.

* The 1980 unabridged audiobook

An audiobook (or a talking book) is a recording of a book or other work being read out loud. A reading of the complete text is described as "unabridged", while readings of shorter versions are abridgements.

Spoken audio has been available in sch ...

adaptation by Recorded Books LLC (#80110) (3 audio-cassettes, 4.5 hours playing time), narrated by Frank Muller.

* The 1981 anime film ''Call of the Wild: Howl Buck'', starring Mike Reynolds and Bryan Cranston

Bryan Lee Cranston (born March 7, 1956) is an American actor. After taking minor roles in television, he established himself as a leading actor in both comedic and dramatic Bryan Cranston filmography, works on stage and screen. He has received ...

.

* The 1983–1984 comic book adaptation by Hungarian comics artist Imre Sebök, which was also translated into German.

* The 1993 movie starring Rick Schroeder.

* The 1997 adaptation called '' The Call of the Wild: Dog of the Yukon'', starring Rutger Hauer

Rutger Oelsen Hauer (; 23 January 1944 – 19 July 2019) was a Dutch actor, with a career that spanned over 170 roles across nearly 50 years, beginning in 1969. In 1999, he was named by the Dutch public as the Best Dutch Actor of the Century.

H ...

and narrated by Richard Dreyfuss

Richard Stephen Dreyfuss ( ; Dreyfus; born October 29, 1947) is an American actor. He emerged from the New Hollywood wave of American cinema, finding fame with a succession of leading man parts in the 1970s. He has received an Academy Award, a ...

.

* The 1998 comic adaptation for ''Boys' Life

''Scout Life'' (formerly ''Boys' Life'') is the monthly magazine of the Boy Scouts of America (BSA). Its target readers are children between the ages of 6 and 18. The magazine‘s headquarters are in Irving, Texas.

''Scout Life'' is published ...

'' magazine. Out of cultural sensitivities, the Yeehat Native Americans are omitted, and John Thornton's killers are now white criminals who, as before, are also killed by Buck.

* The 2000 television adaptation

An adaptation is a transfer of a work of art from one style, culture or medium to another.

Some common examples are:

* Film adaptation, a story from another work, adapted into a film (it may be a novel, non-fiction like journalism, autobiography, ...

released on Animal Planet

Animal Planet (stylized in all lowercase since 2018) is an American multinational pay television channel focusing on the animal kingdom owned by the Warner Bros. Discovery Networks unit of Warner Bros. Discovery. First established on June 1 ...

. It ran for a single season of 13 episodes and was released on DVD in 2010 as a feature film.

* The 2020 film ''The Call of the Wild

''The Call of the Wild'' is an adventure novel by Jack London, published in 1903 and set in Yukon, Canada, during the 1890s Klondike Gold Rush, when strong sled dogs were in high demand. The central character of the novel is a dog named Buck. ...

'', a film starring Harrison Ford

Harrison Ford (born July 13, 1942) is an American actor. Regarded as a cinematic cultural icon, he has starred in Harrison Ford filmography, many notable films over seven decades, and is one of List of highest-grossing actors, the highest-gr ...

. Terry Notary

Terry Notary (born August 14, 1968) is an American actor, stunt coordinator/double and movement coach. Notary mainly portrays creatures and animals for the film and television industry, and is known for his motion capture performances in films, ...

provided the motion-capture

Motion capture (sometimes referred as mocap or mo-cap, for short) is the process of recording high-resolution movement of objects or people into a computer system. It is used in military, entertainment, sports, medical applications, and for val ...

performance for Buck the dog.

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

*Fusco, Richard. "On Primitivism in ''The Call of the Wild''. ''American Literary Realism, 1870–1910''. Vol. 20, No. 1 (Fall, 1987), pp. 76–80 * McCrum, RobertThe 100 best novels: No 35 – The Call of the Wild by Jack London (1903)

"The 100 best novels: No 35 – ''The Call of the Wild'' by Jack London (1903)". ''The Guardian''. 19 May 2014. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

External links

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Call of the Wild, The 1903 American novels American adventure novels Novels set in Yukon Klondike Gold Rush in fiction Novels about dogs Fiction about animal cruelty Novels first published in serial form Works originally published in The Saturday Evening Post American novels adapted into films Adventure novels adapted into films American novels adapted into television shows Novels adapted into comics Novels by Jack London