Thaddeus Stevens on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thaddeus Stevens (April 4, 1792August 11, 1868) was an American politician and lawyer who served as a member of the

At the 1837 Pennsylvania constitutional convention, Stevens, who was a delegate, fought against the

At the 1837 Pennsylvania constitutional convention, Stevens, who was a delegate, fought against the

With the Democrats unable to agree on a single presidential candidate, the

With the Democrats unable to agree on a single presidential candidate, the

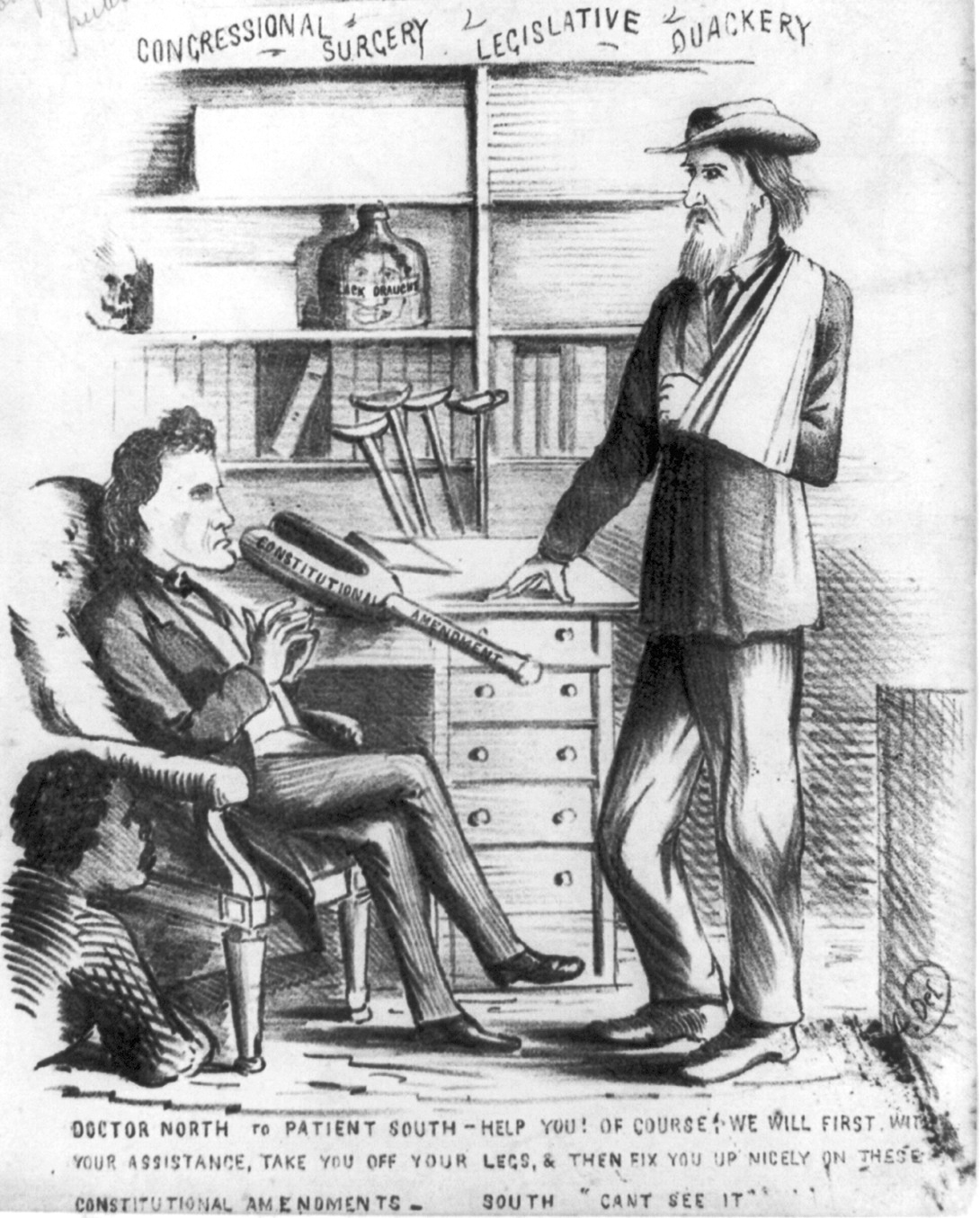

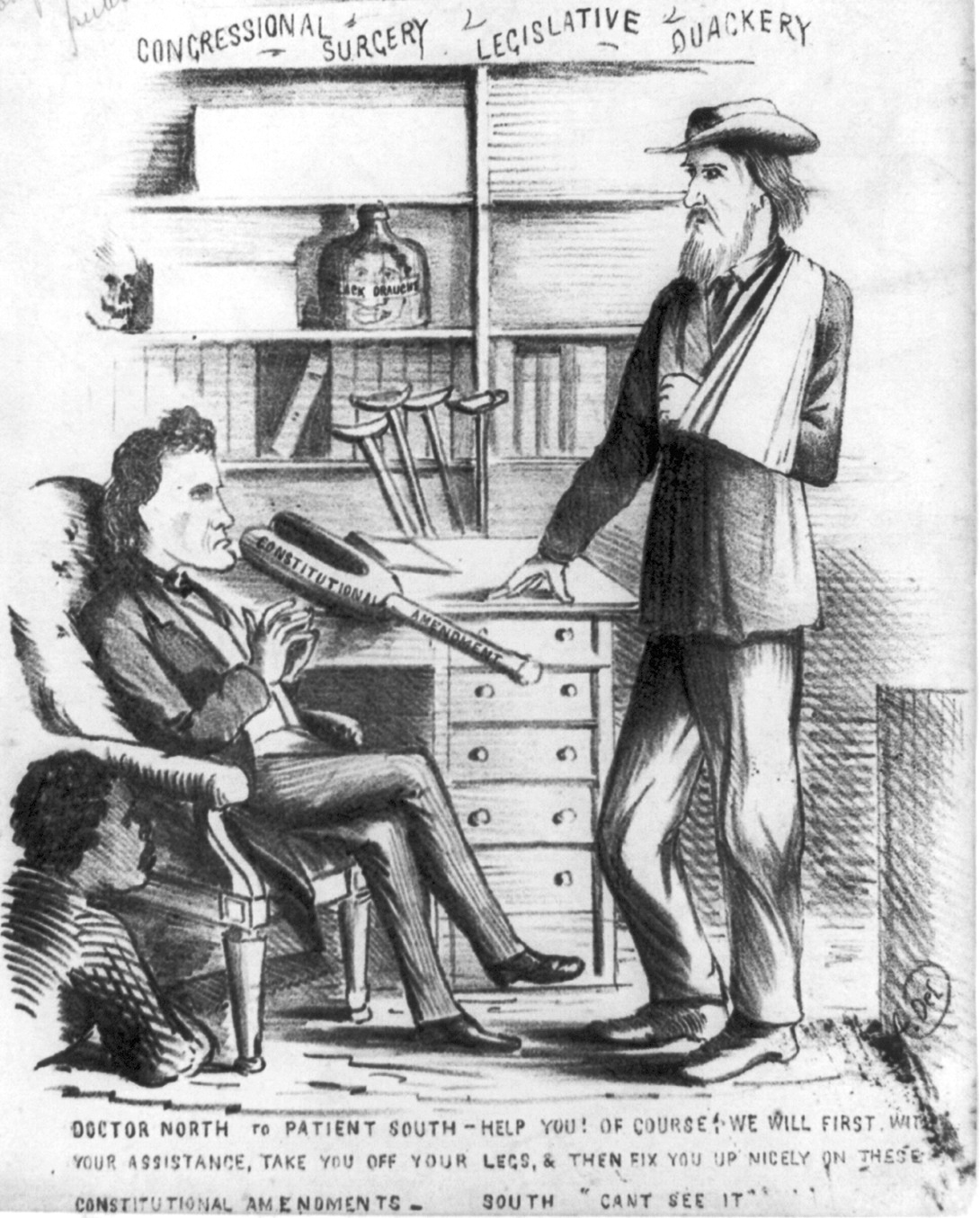

By this time, Stevens was past age seventy and in poor health; he was carried everywhere in a special chair. When Congress convened in early December 1865, Stevens made arrangements with the Clerk of the House that when the roll was called, the names of the Southern electees be omitted. The Senate also excluded Southern claimants. A new congressman, Ohio's Rutherford B. Hayes, described Stevens: "He is radical throughout, except, I am told, he don't believe in hanging. He is leader."

As the responsibilities of the Ways and Means chairman had been divided, Stevens took the post of Chairman of the House Committee on Appropriations, retaining control over the House's agenda. Stevens focused on legislation that would secure the freedom promised by the newly ratified Thirteenth Amendment.Soifer, p. 1616 He proposed and then co-chaired the Joint Committee on Reconstruction with Maine Senator William Pitt Fessenden. This body, also called the Committee of Fifteen, investigated conditions in the South. It heard not only of the violence against African-Americans but against Union loyalists and against what southerners termed "

By this time, Stevens was past age seventy and in poor health; he was carried everywhere in a special chair. When Congress convened in early December 1865, Stevens made arrangements with the Clerk of the House that when the roll was called, the names of the Southern electees be omitted. The Senate also excluded Southern claimants. A new congressman, Ohio's Rutherford B. Hayes, described Stevens: "He is radical throughout, except, I am told, he don't believe in hanging. He is leader."

As the responsibilities of the Ways and Means chairman had been divided, Stevens took the post of Chairman of the House Committee on Appropriations, retaining control over the House's agenda. Stevens focused on legislation that would secure the freedom promised by the newly ratified Thirteenth Amendment.Soifer, p. 1616 He proposed and then co-chaired the Joint Committee on Reconstruction with Maine Senator William Pitt Fessenden. This body, also called the Committee of Fifteen, investigated conditions in the South. It heard not only of the violence against African-Americans but against Union loyalists and against what southerners termed " When Illinois Senator Lyman Trumbull introduced legislation to reauthorize and expand the

When Illinois Senator Lyman Trumbull introduced legislation to reauthorize and expand the

Stevens led the delegation of House members sent the following day to inform the Senate of the impeachment, though he had to be carried to its doors by his bearers. Elected to the committee charged with drafting articles of impeachment, his illness limited his involvement. Nevertheless, dissatisfied with the committee's proposed articles, Stevens suggested another that would become ArticleXI. This grounded the various accusations in statements Johnson had made denying the legitimacy of Congress due to the exclusion of the southern states and stated that Johnson had tried to disobey the Reconstruction Acts. Stevens also urged Benjamin Butler to, independent of the committee, write his own impeachment article, which would ultimately be adopted as Article X.

Stevens was one of the House impeachment managers (prosecutors) elected by the House to present its case in the impeachment trial. Although Stevens was too ill to appear in the Senate on March 3, when the managers requested that Johnson be summoned (the president would appear only by his counsel or defense managers), he was there ten days later when the summons was returnable. The ''

Stevens led the delegation of House members sent the following day to inform the Senate of the impeachment, though he had to be carried to its doors by his bearers. Elected to the committee charged with drafting articles of impeachment, his illness limited his involvement. Nevertheless, dissatisfied with the committee's proposed articles, Stevens suggested another that would become ArticleXI. This grounded the various accusations in statements Johnson had made denying the legitimacy of Congress due to the exclusion of the southern states and stated that Johnson had tried to disobey the Reconstruction Acts. Stevens also urged Benjamin Butler to, independent of the committee, write his own impeachment article, which would ultimately be adopted as Article X.

Stevens was one of the House impeachment managers (prosecutors) elected by the House to present its case in the impeachment trial. Although Stevens was too ill to appear in the Senate on March 3, when the managers requested that Johnson be summoned (the president would appear only by his counsel or defense managers), he was there ten days later when the summons was returnable. The ''

During the recess of the impeachment court, the Republicans met in convention in Chicago and nominated Grant for president. Stevens did not attend and was dismayed by the exclusion of African-American suffrage from the

During the recess of the impeachment court, the Republicans met in convention in Chicago and nominated Grant for president. Stevens did not attend and was dismayed by the exclusion of African-American suffrage from the

It is uncertain if the Stevens-Smith relationship was romantic. The Democratic press, especially in the South, assumed so, and when he brought Smith to Washington in 1859, she managed his household, which did nothing to stop their insinuations. In the one brief surviving letter from Stevens to her, Stevens addresses her as "Mrs. Lydia Smith". Stevens insisted that his nieces and nephews refer to her as "Mrs. Smith", despite deference towards an African-American servant being almost unheard of at that time. They do so in surviving letters, warmly, asking Stevens to see that she comes with him next time he visits.

As evidence that their relationship was sexual, Brodie pointed to an 1868 letter in which Stevens compares himself to Vice President Richard M. Johnson, who lived openly with a series of African-American slave mistresses. Johnson was elected even though this became known during the 1836 presidential campaign of

It is uncertain if the Stevens-Smith relationship was romantic. The Democratic press, especially in the South, assumed so, and when he brought Smith to Washington in 1859, she managed his household, which did nothing to stop their insinuations. In the one brief surviving letter from Stevens to her, Stevens addresses her as "Mrs. Lydia Smith". Stevens insisted that his nieces and nephews refer to her as "Mrs. Smith", despite deference towards an African-American servant being almost unheard of at that time. They do so in surviving letters, warmly, asking Stevens to see that she comes with him next time he visits.

As evidence that their relationship was sexual, Brodie pointed to an 1868 letter in which Stevens compares himself to Vice President Richard M. Johnson, who lived openly with a series of African-American slave mistresses. Johnson was elected even though this became known during the 1836 presidential campaign of

With the advent of the Dunning School's view of Reconstruction after 1900, Stevens continued to be viewed negatively and generally as motivated by hatred. These historians, led by William Dunning, taught that Reconstruction had been an opportunity for radical politicians, motivated by ill will towards the South, to destroy what little of southern life and dignity the war had left.Berlin, p. 154Castel, pp. 220–21 Dunning himself deemed Stevens "truculent, vindictive, and cynical". Lloyd Paul Stryker, who wrote a highly favorable 1929 biography of Johnson, labeled Stevens as a "horrible old man... craftily preparing to strangle the bleeding, broken body of the South" and who thought it would be "a beautiful thing" to see "the white men, especially the white women of the South, writhing under negro domination". In 1915, D. W. Griffith's film ''The Birth of a Nation'' (based on the 1905 novel ''The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan, The Clansman'', by Thomas Dixon Jr.) was released, containing the influenceable and ill-advised Congressman Austin Stoneman, who resembles Stevens down to the ill-fitting wig, limp, and African-American lover, Lydia Brown. This popular treatment reinforced and reinvigorated public prejudices towards Stevens.Berlin, p. 155 According to Foner, "as historians exalted the magnanimity of Lincoln and Andrew Johnson, Stevens came to symbolize Northern malice, revenge, and irrational hatred of the South."Eric Foner, Foner, Eric

With the advent of the Dunning School's view of Reconstruction after 1900, Stevens continued to be viewed negatively and generally as motivated by hatred. These historians, led by William Dunning, taught that Reconstruction had been an opportunity for radical politicians, motivated by ill will towards the South, to destroy what little of southern life and dignity the war had left.Berlin, p. 154Castel, pp. 220–21 Dunning himself deemed Stevens "truculent, vindictive, and cynical". Lloyd Paul Stryker, who wrote a highly favorable 1929 biography of Johnson, labeled Stevens as a "horrible old man... craftily preparing to strangle the bleeding, broken body of the South" and who thought it would be "a beautiful thing" to see "the white men, especially the white women of the South, writhing under negro domination". In 1915, D. W. Griffith's film ''The Birth of a Nation'' (based on the 1905 novel ''The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan, The Clansman'', by Thomas Dixon Jr.) was released, containing the influenceable and ill-advised Congressman Austin Stoneman, who resembles Stevens down to the ill-fitting wig, limp, and African-American lover, Lydia Brown. This popular treatment reinforced and reinvigorated public prejudices towards Stevens.Berlin, p. 155 According to Foner, "as historians exalted the magnanimity of Lincoln and Andrew Johnson, Stevens came to symbolize Northern malice, revenge, and irrational hatred of the South."Eric Foner, Foner, Eric

"If you wondered about Thaddeus Stevens..."

''

"Warning: Artists at work"

Dickinson College. Retrieved on June 15, 2013. According to Aaron Bady in his article about the film and how it portrays the radicals, "he's the uncle everyone is embarrassed of, even if they love him too much to say so. He's not a leader, he's a liability, one whose shining heroic moment will be when he keeps silent about what he really believes."Bady, Aaron

"''Lincoln'' Against the Radicals"

''Jacobin''. Retrieved on June 15, 2013. The film depicts a Stevens-Smith sexual relationship; Pinsker comments that "it may well have been true that they were lovers, but by injecting this issue into the movie, the filmmakers risk leaving the impression for some viewers that the 'secret' reason for Stevens's egalitarianism was his desire to legitimize his romance across racial lines." On April 2, 2022, in front of the Adams County Courthouse in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, a statue of Stevens was unveiled as part of a celebration of Stevens' 230th birthday. The statue was commissioned by the Thaddeus Stevens Society and was sculpted by multidisciplinary artist Alex Paul Loza.

''Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association'', vol. 21, no. 2 (Summer 2000), pp. 75–81.

* * Horace Mann Bond, Bond, Horace Mann. "Social and Economic Forces in Alabama Reconstruction." ''Journal of Negro History'' 23(3), July 1938. , 7July 2013. *

online

* * * LaWanda Cox, Cox, LaWanda and John H. Cox. ''Politics, Principle, and Prejudice 1865–1866: Dilemma of Reconstruction America''. London: Collier-Macmillan, 1963. *

text

* * W. E. B. Du Bois, Du Bois, W. E. B.

Black Reconstruction: An Essay Toward a History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860–1880

'. New York: Russell & Russell, 1935. * * Eric Foner, Foner, Eric. ''Politics and Ideology in the Age of the Civil War''. Oxford University Press, 1980. * * *

text

* Hamilton, Howard Devon. ''The Legislative and Judicial History of the Thirteenth Amendment''. Political Science dissertation at the University of Illinois; accepted May 15, 1950. * * Aviam Soifer, Soifer, Aviam.

Federal Protection, Paternalism, and the Virtually Forgotten Prohibition of Voluntary Peonage

. ''Columbia Law Review'' 112(7), November 2012; pp. 1607–40. * * Hans L. Trefousse, Trefousse, Hans L. ''Thaddeus Stevens: Nineteenth-Century Egalitarian''. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1997. * Alexander Tsesis, Tsesis, Alexander. The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom: A Legal History. New York University Press, 2004. * Vorenberg, Michael. '' Final Freedom: The American Civil War, Civil War, the Abolitionism in the United States, Abolition of Slavery, and the Thirteenth Amendment''. Cambridge University Press, 2001. . * Woodley, Thomas F. ''Great Leveler: The Life of Thaddeus Stevens'' (1937

online

online

*

online

online

* Richard N. Current, Current, Richard Nelson. ''Old Thad Stevens: A Story of Ambition'' (1980 [1942]), Westport, Ct.: Greenwood Press, , , a scholarly biography that argues Stevens was primarily concerned with enhancing his power, the power of the Republican Party, and the needs of big business, especially iron-making and railroads. * * Eric Foner, Foner, Eric. "Thaddeus Stevens, Confiscation, and Reconstruction," in Stanley Elkins and Eric McKitrick, eds. ''The Hofstadter Aegis'' (1974)

* Foner, Eric. "Thaddeus Stevens and the Imperfect Republic." ''Pennsylvania History'', vol. 60, no. 2, pp. 140–52 (April 1993) * William Everdell, Everdell, William R. "Thaddeus Stevens: The Legacy of the America Whigs" in ''The End of Kings: A History of Republics and Republicans''. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000. , * Goldenberg, Barry M. ''The Unknown Architects of Civil Rights: Thaddeus Stevens, Ulysses S. Grant, and Charles Sumner.'' Los Angeles, CA: Critical Minds Press. (2011). * Graber, Mark A.

Subtraction by Addition?: The Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments

. ''Columbia Law Review'' 112(7), November 2012; pp. 1501–49. * Hoelscher, Robert J. ''Thaddeus Stevens as a Lancaster Politician, 1842–1868'' (Lancaster County Historical Society, 1974

online

* Korngold, Ralph. ''Thaddeus Stevens: A Being Darkly Wise and Rudely Great'' (1955

online

* Lawson, Elizabeth.

Thaddeus Stevens

'. New York: International Publishers. 1942. (1962 reprint) * * Samuel W. McCall, McCall, Samuel Walker. ''Thaddeus Stevens'' (1899) 369 pages; outdated biograph

online

* Parra, Fernando. "Thaddeus Stevens: Early Civil Rights Leader." ''Footnotes: A Journal of History'' 1 (2017): 184–203

online

* * Shepard, Christopher, "Making No Distinctions between Rich and Poor: Thaddeus Stevens and Class Equality", ''Pennsylvania History'', 80 (Winter 2013), 37–50

online

* * Stryker, Lloyd Paul. ''Andrew Johnson: A Study in Courage'' (1929), New York: Macmilliam, , hostile to Stevens. * Woodburn, James Albert. ''The Life of Thaddeus Stevens: A Study in American Political History, Especially in the Period of the Civil War and Reconstruction''. (1913

online version

* Woodburn, James Albert. "The Attitude of Thaddeus Stevens Toward the Conduct of the Civil War", ''American Historical Review'', Vol. 12, no.3 (April 1907), pp. 567–83 * Joshua M. Zeitz, Zeitz, Josh. "Stevens, Thaddeus", ''American National Biography Online''. February 2000. , Unique Identifier: 4825694186

online

* Foner, Eric. "Thaddeus Stevens and the Imperfect Republic," ''Pennsylvania History'' 60.2 (1993): 140–152

online

* Jolly, James A. "The Historical Reputation of Thaddeus Stevens," ''Journal of the Lancaster County Historical Society'' (1970) 74:33–71

online

* Pickens, Donald K. "The Republican Synthesis and Thaddeus Stevens," ''Civil War History'' (1985) 31:57–73, , Unique Identifier: 5183399288; argues that Stevens was committed to Republicanism in the United States, Republicanism and capitalism in terms of self-improvement, the advance of society, equal distribution of land, and economic liberty for all; to achieve that he had to destroy slavery and the aristocracy.

The Journal of the Joint Committee of Fifteen on Reconstruction

'. New York: Columbia University, 1914. * Palmer, Beverly Wilson and Holly Byers Ochoa, eds. ''The Selected Papers of Thaddeus Stevens''. Two vol. (1998), 900 pages; his speeches plus letters to and from Stevens. ,

excerpt vol 1

*

online review

* Stevens, Thaddeus, et al. '' Report of the Joint Committee on Reconstruction, at the First Session... by United States Congress. Joint Committee on Reconstruction'', (1866) 791 pages

online edition

* ''Memorial Addresses on the Life and Character of Thaddeus Stevens: Delivered... by United States 40th Cong., 3d sess., 1868–1869''. (1869) 84 pages

online edition

Abolitionist And African American Businesswoman

Stevens and Smith Historic Site

Thaddeus Stevens Society

* Includes

Guide to Research Collections

' where his papers are located.

Mr. Lincoln and Freedom: Thaddeus Stevens

Mr. Lincoln's White House: Thaddeus Stevens

, - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Stevens, Thaddeus 1792 births 1868 deaths Activists for African-American civil rights American politicians with disabilities Anti-Masonic Party politicians from Pennsylvania Baptist abolitionists Baptists from Pennsylvania Dartmouth College alumni Members of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives Pennsylvania city council members Pennsylvania Federalists Pennsylvania Know Nothings Pennsylvania lawyers Pennsylvania Whigs People from Danville, Vermont Politicians from Lancaster, Pennsylvania People of the Reconstruction Era People of Pennsylvania in the American Civil War Radical Republicans Republican Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania Underground Railroad people Union (American Civil War) political leaders Whig Party members of the United States House of Representatives American lawyers with disabilities 19th-century members of the Pennsylvania General Assembly 19th-century members of the United States House of Representatives

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Artic ...

from Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

, being one of the leaders of the Radical Republican faction of the Republican Party during the 1860s. A fierce opponent of slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

and discrimination against black Americans, Stevens sought to secure their rights during Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

, leading the opposition to U.S. President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. The 16th vice president, he assumed the presidency following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a South ...

. As chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee

A ways and means committee is a government body that is charged with reviewing and making recommendations for government budgets. Because the raising of revenue is vital to carrying out governmental operations, such a committee is tasked with fi ...

during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, he played a leading role, focusing his attention on defeating the Confederacy, financing the war with new taxes and borrowing, crushing the power of slave owners, ending slavery, and securing equal rights for the freedmen.

Stevens was born in rural Vermont, in poverty, and with a club foot

Clubfoot is a congenital or acquired defect where one or both feet are supinated, rotated inward and plantar flexion, downward. Congenital clubfoot is the most common congenital malformation of the foot with an incidence of 1 per 1000 births. ...

, which left him with a permanent limp. He moved to Pennsylvania as a young man and quickly became a successful lawyer in Gettysburg. He interested himself in municipal affairs and then in politics. He was an active leader of the Anti-Masonic Party

The Anti-Masonic Party was the earliest Third party (United States), third party in the United States. Formally a Single-issue politics, single-issue party, it strongly opposed Freemasonry in the United States. It was active from the late 1820s, ...

, as a fervent believer that Freemasonry in the United States was an evil conspiracy to secretly control the republican system of government. He was elected to the Pennsylvania House of Representatives

The Pennsylvania House of Representatives is the lower house of the bicameral Pennsylvania General Assembly, the legislature of the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. There are 203 members, elected for two-year terms from single member districts.

It ...

, where he became a strong advocate of free public education. Financial setbacks in 1842 caused him to move his home and practice to the larger city of Lancaster. There, he joined the Whig Party and was elected to Congress in 1848. His activities as a lawyer and politician in opposition to slavery cost him votes, and he did not seek reelection in 1852. After a brief flirtation with the Know-Nothing Party

The American Party, known as the Native American Party before 1855 and colloquially referred to as the Know Nothings, or the Know Nothing Party, was an Old Stock nativist political movement in the United States in the 1850s. Members of the m ...

, Stevens joined the newly formed Republican Party and was elected to Congress again in 1858. There, with fellow radicals such as Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811March 11, 1874) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Massachusetts in the United States Senate from 1851 until his death in 1874. Before and during the American Civil War, he was a leading American ...

, he opposed the expansion of slavery and concessions to the South as the war came.

Stevens argued that slavery should not survive the war; he was frustrated by the slowness of U.S. President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

to support his position. He guided the government's financial legislation through the House as Ways and Means chairman. As the war progressed towards a Northern victory, Stevens came to believe that not only should slavery be abolished, but that black Americans should be given a stake in the South's future through the confiscation of land from planters to be distributed to the freedmen. His plans went too far for the Moderate Republicans and were not enacted.

After the assassination of Abraham Lincoln

On April 14, 1865, Abraham Lincoln, the 16th president of the United States, was shot by John Wilkes Booth while attending the play '' Our American Cousin'' at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C. Shot in the head as he watched the play, L ...

in April 1865, Stevens came into conflict with the new president, Johnson, who sought rapid restoration of the seceded states without guarantees for freedmen. The difference in views caused an ongoing battle between Johnson and Congress, with Stevens leading the Radical Republicans. After gains in the 1866 election, the radicals took control of Reconstruction away from Johnson. Stevens's last great battle was to secure in the House articles of impeachment against Johnson, acting as a House manager in the impeachment trial

An impeachment trial is a trial that functions as a component of an impeachment. Several governments utilize impeachment trials as a part of their processes for impeachment. Differences exist between governments as to what stage trials take place ...

, though the Senate did not convict the President.

Historiographical

Historiography is the study of the methods used by historians in developing history as an academic discipline. By extension, the term ":wikt:historiography, historiography" is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiog ...

views of Stevens have dramatically shifted over the years, from the early 20th-century view of Stevens as reckless and motivated by hatred of the white South to the perspective of the neoabolitionists of the 1950s and afterward, who lauded him for his commitment to equality.

Early life and education

Stevens was born inDanville, Vermont

Danville is a New England town, town in Caledonia County, Vermont, Caledonia County, Vermont, United States. The population was 2,335 at the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census. The primary settlement in town is recorded as the Danville (CDP), ...

, on April 4, 1792. He was the second of four children, all boys, and was named to honor the Polish general who served in the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

, Tadeusz "Thaddeus" Kościuszko. His parents were Baptists who had emigrated from Massachusetts around 1786. Thaddeus was born with a club foot

Clubfoot is a congenital or acquired defect where one or both feet are supinated, rotated inward and plantar flexion, downward. Congenital clubfoot is the most common congenital malformation of the foot with an incidence of 1 per 1000 births. ...

which, at the time, was seen by some as a judgment from God for secret parental sin. His older brother was born with the same condition in both feet. The boys' father, Joshua Stevens, was a farmer and cobbler who struggled to make a living in Vermont. After fathering two more sons (born without disability), Joshua abandoned the children and his wife Sarah ( Morrill). The circumstances of his departure and his subsequent fate are uncertain; he may have died at the Battle of Oswego during the War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

.

Sarah Stevens struggled to make a living from the farm even with the increasing aid of her sons. She was determined that her sons improve themselves, and in 1807 moved the family to the neighboring town of Peacham, Vermont, where she enrolled young Thaddeus in the Caledonia Grammar School (often called the Peacham Academy). He suffered much from the taunts of his classmates for his disability. Later accounts describe him as "wilful, headstrong" with "an overwhelming burning desire to secure an education."

After graduation, he enrolled at the University of Vermont

The University of Vermont and State Agricultural College, commonly referred to as the University of Vermont (UVM), is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Burlington, Vermont, United States. Foun ...

, but suspended his studies due to the federal government's appropriation of campus buildings during the War of 1812. Stevens then enrolled in the sophomore class at Dartmouth College

Dartmouth College ( ) is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Hanover, New Hampshire, United States. Established in 1769 by Eleazar Wheelock, Dartmouth is one of the nine colonial colleges chartered before the America ...

. At Dartmouth, despite a stellar academic career, he was not elected to Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States. It was founded in 1776 at the College of William & Mary in Virginia. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal arts and sciences, ...

; this was reportedly a scarring experience for him.

Stevens graduated from Dartmouth in 1814 and spoke at the commencement ceremony. Afterward, he returned to Peacham and briefly taught there. Stevens also began to read law in the office of John Mattocks. In early 1815, correspondence with a friend, Samuel Merrill, a fellow Vermonter who had moved to York, Pennsylvania

York is a city in York County, Pennsylvania, United States, and its county seat. Located in South Central Pennsylvania, the city's population was 44,800 at the time of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the List of cities in ...

to become preceptor of the York Academy, led to an offer for Stevens to join the academy faculty. He moved to York to teach, and continued the study of law in the offices of David Cossett.

Pennsylvania attorney and politician

Gettysburg lawyer

In Pennsylvania, Stevens taught school at the York Academy and continued his studies for the bar. Local lawyers passed a resolution barring from membership anyone who had "followed any other profession while preparing for admission,"Franklin Ellis; Samuel Evans; Everts & Peck. (1993). ''History of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, with Biographical Sketches of Many of its Pioneers and Prominent Men'': ChapterXXI. Salem, Ma.: The Bench and Bar of Lancaster County, a restriction likely aimed at Stevens. Undaunted, he reportedly (according to a story he often retold) presented himself and four bottles of Madeira wine to the examining board in nearbyHarford County, Maryland

Harford County is a county located in the U.S. state of Maryland. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population was 260,924. Its county seat is Bel Air, Harford County, Maryland, Bel Air. Harford County is included in the Wa ...

. Few questions were asked, but much wine was drunk. He left Bel Air the next morning with a certificate allowing him, through reciprocity, to practice law anywhere. Stevens then went to Gettysburg, the seat of Adams County, where he opened an office in September 1816.Brodie, p. 32

Stevens knew no one in Gettysburg and initially had little success as a lawyer. His breakthrough, in mid-1817, was a case in which a farmer who had been jailed for debt later killed one of the constable

A constable is a person holding a particular office, most commonly in law enforcement. The office of constable can vary significantly in different jurisdictions. ''Constable'' is commonly the rank of an officer within a police service. Other peo ...

s who had arrested him. His defense, although unsuccessful, impressed the local people, and he never lacked for business thereafter. In his legal career, he demonstrated the propensity for sarcasm that would later mark him as a politician, once telling a judge who accused him of manifesting contempt of court

Contempt of court, often referred to simply as "contempt", is the crime of being disobedient to or disrespectful toward a court of law and its officers in the form of behavior that opposes or defies the authority, justice, and dignity of the co ...

, "Sir, I am doing my best to conceal it."

Many who memorialized Stevens after his death in 1868 agreed on his talent as a lawyer. He was involved in the first ten cases to reach the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania

The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania is the highest court in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania's Judiciary of Pennsylvania, Unified Judicial System. It began in 1684 as the Provincial Court, and casual references to it as ...

from Adams County after he began his practice and won nine. One case he later wished he had not won was ''Butler v. Delaplaine'', in which he successfully reclaimed a slave on behalf of her owner.

In Gettysburg, Stevens also began his involvement in politics, serving six one-year terms on the borough

A borough is an administrative division in various English language, English-speaking countries. In principle, the term ''borough'' designates a self-governing walled town, although in practice, official use of the term varies widely.

History

...

council between 1822 and 1831 and becoming its president. He took the profits from his practice and invested them in Gettysburg real estate, becoming the largest landowner in the community by 1825, and had an interest in several iron furnaces outside town. In addition to assets, he acquired enemies; after the death of a pregnant black woman in Gettysburg, there were anonymous letter-writers to newspapers, hinting that Stevens was culpable. The rumors dogged him for years; when one newspaper opposed to Stevens printed a letter in 1831 naming him as the killer, he successfully sued for libel.

Anti-Masonry

Stevens's first political cause wasAnti-Masonry

Anti-Masonry (alternatively called anti-Freemasonry) is "avowed opposition to Freemasonry",''Oxford English Dictionary'' (1979 ed.), p. 369. which has led to multiple forms of religious discrimination, Religious violence, violent Religious persec ...

, which became widespread in 1826 after the disappearance and death of William Morgan, a Mason in upstate New York

Upstate New York is a geographic region of New York (state), New York that lies north and northwest of the New York metropolitan area, New York City metropolitan area of downstate New York. Upstate includes the middle and upper Hudson Valley, ...

; fellow Masons were presumed to be the killers of Morgan because they disapproved of his publishing a book revealing the order's secret rites. Since the leading candidate in opposition to President John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was the sixth president of the United States, serving from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States secretary of state from 1817 to 1825. During his long diploma ...

was General Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

, a Mason who mocked opponents of the order, Anti-Masonry became closely associated with opposition to Jackson and his Jacksonian democracy

Jacksonian democracy, also known as Jacksonianism, was a 19th-century political ideology in the United States that restructured a number of federal institutions. Originating with the seventh U.S. president, Andrew Jackson and his supporters, i ...

policies once he was elected president in 1828.

Jackson's adherents were from the old Democratic–Republican Party and eventually became known as the Democrats. Stevens had been told by a fellow attorney (and future president) James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was the 15th president of the United States, serving from 1857 to 1861. He also served as the United States Secretary of State, secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and represented Pennsylvan ...

that he could advance politically if he joined them. However, Stevens could not support Jackson, out of principle. For Stevens, Anti-Masonry became one means of opposing Jackson; he may also have had personal reasons as the Masons barred "cripples" from joining. Stevens took to Anti-Masonry with enthusiasm and remained loyal to it after most Pennsylvanians had dropped the cause. His biographer, Hans Trefousse, suggested that another reason for Stevens's virulence was an attack of disease in the late 1820s that cost him his hair (he thereafter wore wigs, often ill-fitting), and "the unwelcome illness may well have contributed to his unreasonable fanaticism concerning the Masons."

By 1829, Anti-Masonry had evolved into a political party, the Anti-Masonic Party

The Anti-Masonic Party was the earliest Third party (United States), third party in the United States. Formally a Single-issue politics, single-issue party, it strongly opposed Freemasonry in the United States. It was active from the late 1820s, ...

, that proved popular in rural central Pennsylvania. Stevens quickly became prominent in the movement, attending the party's first two national conventions in 1830 and 1831. At the latter, he pressed the candidacy of Supreme Court Justice John McLean as the party's presidential candidate, but in vain as the nomination fell to former Attorney General William Wirt. Jackson was easily reelected; the crushing defeat (Wirt won only Vermont) caused the party to disappear in most places, though it remained powerful in Pennsylvania for several years.

In September 1833, Stevens was elected to a one-year term in the Pennsylvania House of Representatives as an Anti-Mason. Once in the capital Harrisburg

Harrisburg ( ; ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), U.S. commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the county seat, seat of Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, Dauphin County. With a population of 50, ...

, he sought to have the body establish a committee to investigate Masonry. Stevens gained attention far beyond Pennsylvania for his oratory against Masonry and quickly became an expert in legislative maneuvers. In 1835, a split among the Democrats put the Anti-Masons in control of the Pennsylvania General Assembly

The Pennsylvania General Assembly is the legislature of the U.S. commonwealth of Pennsylvania. The legislature convenes in the State Capitol building in Harrisburg. In colonial times (1682–1776), the legislature was known as the Pennsylvani ...

, the legislature. Granted subpoena powers, Stevens summoned leading state politicians who were Masons, including Governor George Wolf. The witnesses invoked their Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination, and when Stevens verbally abused one of them, it created a backlash that caused his own party to end the investigation. The fracas cost Stevens reelection in 1836, and the issue of Anti-Masonry died in Pennsylvania. Nevertheless, Stevens remained an opponent of the order for the rest of his life.

Crusader for education

Beginning with his early years in Gettysburg, Stevens advanced the cause of universal education. At the time, no state outsideNew England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

had free public education for all. In Pennsylvania, there was free education in Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

, but elsewhere in the state, those wishing to have their children educated without paying tuition had to swear a pauper's oath. Stevens opened his extensive private library to the public and gave up his presidency of the borough council, believing his service on the school board

A board of education, school committee or school board is the board of directors or board of trustees of a school, local school district or an equivalent institution.

The elected council determines the educational policy in a small regional area, ...

more important. In 1825, he was elected by the voters of Adams County as a trustee of Gettysburg Academy. As the school was failing, Stevens got county

A county () is a geographic region of a country used for administrative or other purposesL. Brookes (ed.) '' Chambers Dictionary''. Edinburgh: Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd, 2005. in some nations. The term is derived from the Old French denoti ...

voters to agree to pay its debt, allowing it to be sold as a Lutheran seminary. It was granted the right to award college degrees in 1831 as Pennsylvania College, and in 1921 became Gettysburg College

Gettysburg College is a Private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Founded in 1832, the campus is adjacent to the Gettysburg Battlefield. Gettysburg College has about ...

. Stevens gave the school land upon which a building could be raised and served as a trustee for many years.

In April 1834, Stevens, working with Governor Wolf, guided an act through the legislature to allow districts across the state to vote on whether to have public schools and the taxes to pay for them. Gettysburg's district voted in favor and also elected Stevens as a school director, where he served until 1839. Tens of thousands of voters signed petitions urging a reversal. The result was a repeal bill that easily passed the Pennsylvania Senate

The Pennsylvania State Senate is the upper house of the Pennsylvania General Assembly, the Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mi ...

. It was widely believed the bill would also pass the House and be enacted despite opposition by Stevens. When he rose to speak on April 11, 1835, he defended the new educational system, stating that it would actually save money, and demonstrated how. He stated that opponents were seeking to separate the poor into a lower caste than themselves and accused the rich of greed and failure to empathize with the poor. Stevens argued, "Build not your monuments of brass or marble, but make them of everliving mind!" The repeal bill was defeated; Stevens was given wide credit. Trefousse suggested that the victory was not due to Stevens's eloquence, but due to his influence, combined with that of Governor Wolf.

Political change; move to Lancaster

In 1838, Stevens ran again for the legislature. He hoped that if the remaining Anti-Masons and the emerging Whig Party gained a majority, he could be elected to theUnited States Senate

The United States Senate is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the United States House of Representatives, U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and ...

, whose members until 1913 were chosen by state legislatures. A campaign, dirty even by the standards of the times, followed. The result was a Democrat elected as governor, Whig control of the state Senate, and the state House in dispute, with several seats from Philadelphia in question. Stevens won his seat in Adams County, and sought to have those Philadelphia Democrats excluded, which would create a Whig majority that could elect a Speaker and himself as a senator. Amid rioting in Harrisburglater known as the " Buckshot War"Stevens's ploy backfired, with the Democrats taking control of the House. Stevens remained in the legislature for most years through 1842 but the episode cost him much of his political influence. The Whigs blamed him for the debacle and were increasingly unwilling to give leadership to someone who had not yet joined their party. Nevertheless, he supported the pro-business and pro-development Whig stances.Brodie, pp. 75–84 He campaigned for the Whig candidate in the 1840 presidential election, former general William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was the ninth president of the United States, serving from March 4 to April 4, 1841, the shortest presidency in U.S. history. He was also the first U.S. president to die in office, causin ...

. Though Stevens later alleged that Harrison had promised him a Cabinet position if elected, he received none, and any influence ended when Harrison died after a month in office, to be succeeded by John Tyler

John Tyler (March 29, 1790 – January 18, 1862) was the tenth president of the United States, serving from 1841 to 1845, after briefly holding office as the tenth vice president of the United States, vice president in 1841. He was elected ...

, a southerner hostile to Stevens's stances on slavery.

Although Stevens was the most successful lawyer in Gettysburg, he had accrued debt due to his business interests. Refusing to take advantage of the bankruptcy laws, he felt he needed to move to a larger municipality to gain the money to pay his obligations. In 1842, Stevens moved his home and practice to Lancaster. He knew Lancaster County was an Anti-Mason and Whig stronghold, which ensured that he retained a political base. Within a short period, he was earning more than any other Lancaster attorney; by 1848, he had reduced his debts to $30,000 (~$ in ) and paid them off soon after. It was in Lancaster that he engaged the services of Lydia Hamilton Smith, a housekeeper, whose racial makeup was described as mulatto

( , ) is a Race (human categorization), racial classification that refers to people of mixed Sub-Saharan African, African and Ethnic groups in Europe, European ancestry only. When speaking or writing about a singular woman in English, the ...

, and who remained with him the rest of his life.

Abolitionist and prewar congressman

Evolution of views

In the 1830s, few sought the immediate eradication of slavery. The abolitionist movement was young and only recently had figures such asWilliam Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was an Abolitionism in the United States, American abolitionist, journalist, and reformism (historical), social reformer. He is best known for his widely read anti-slavery newspaper ''The ...

taken on the fight.Brodie, pp. 105–06 Stevens's reason for adopting slavery as a cause has been disputed among his recent biographers. Richard N. Current, in 1942, suggested it was out of ambition; Fawn Brodie, in her controversial 1959 psychobiography of Stevens, suggested it was out of identification with the downtrodden, based on his handicap. Trefousse, in his 1997 work, also suggested that Stevens's feelings towards the downtrodden were a factor, combined with remorse over the ''Butler'' case, but that ambition was unlikely to have been a significant motivator, as Stevens's fervor in the anti-slavery cause inhibited his career.

disenfranchisement

Disfranchisement, also disenfranchisement (which has become more common since 1982) or voter disqualification, is the restriction of suffrage (the right to vote) of a person or group of people, or a practice that has the effect of preventing someo ...

of African-Americans (see Black suffrage in Pennsylvania). According to historian Eric Foner

Eric Foner (; born February 7, 1943) is an American historian. He writes extensively on American political history, the history of freedom, the early history of the Republican Party, African American biography, the American Civil War, Reconstr ...

, "When Stevens refused to sign the 1837 constitution because of its voting provision, he announced his commitment to a non-racial definition of American citizenship to which he would adhere for the remainder of his life."Foner, p. 143 After he moved to Lancaster, a city not far from the Mason–Dixon line

The Mason–Dixon line, sometimes referred to as Mason and Dixon's Line, is a demarcation line separating four U.S. states: Pennsylvania, Maryland, Delaware and West Virginia. It was Surveying, surveyed between 1763 and 1767 by Charles Mason ...

, he became active in the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was an organized network of secret routes and safe houses used by freedom seekers to escape to the abolitionist Northern United States and Eastern Canada. Enslaved Africans and African Americans escaped from slavery ...

, not only defending people believed to be fugitive slaves, but coordinating the movements of those seeking freedom. A 2003 renovation at his former home in Lancaster disclosed that there was a hidden cistern, attached to the main building by a concealed tunnel, in which escaped slaves hid.

Until the outbreak of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, Stevens took the public position that he supported slavery's end and opposed its expansion. Nevertheless, he would not seek to disturb it in the states where it existed, because the Constitution protected their internal affairs from federal interference. He also supported slave-owning Whig candidates for president: Henry Clay

Henry Clay (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seventh Spea ...

in 1844 and Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military officer and politician who was the 12th president of the United States, serving from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States ...

in 1848.

First tenure in Congress

In 1848, Stevens ran for election to Congress from . There was opposition to him at the Whig convention. Some delegates felt that because Stevens had been late to join the party, he should not receive the nomination; others disliked his stance on slavery. He narrowly won the nomination. In a strong year for Whigs nationally, Taylor was chosen as president and Stevens was elected to Congress. When the31st United States Congress

The 31st United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C., from March 4, 1849, ...

convened in December 1849, Stevens took his seat, joining other newly elected slavery opponents such as Salmon P. Chase. Stevens spoke out against the Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that temporarily defused tensions between slave and free states during the years leading up to the American Civil War. Designe ...

, crafted by Kentucky Senator Henry Clay

Henry Clay (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seventh Spea ...

, that gave victories to both North and South, but would allow for some of the territories of the United States

Territories of the United States are sub-national administrative divisions and dependent territory, dependent territories overseen by the federal government of the United States. The American territories differ from the U.S. states and Indi ...

recently gained from Mexico to become slave states. As the debates continued, in June he said, "This word 'compromise' when applied to human rights and constitutional rights I abhor." Nevertheless, the pieces of legislation that made up the Compromise passed, including the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850

The Fugitive Slave Act or Fugitive Slave Law was a law passed by the 31st United States Congress on September 18, 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850 between Southern interests in slavery and Northern Free-Soilers.

The Act was one ...

, which Stevens found particularly offensive. Although many Americans hoped that the Compromise would bring sectional peace, Stevens warned that it would be "the fruitful mother of future rebellion, disunion, and civil war."

Stevens was easily renominated and reelected in 1850, even though his stance caused him problems among pro-Compromise Whigs.Brodie, pp. 116–19 In 1851, Stevens was one of the defense lawyers in the trial of 38 African-Americans and three others in federal court in Philadelphia on treason charges. The defendants had been implicated in the so-called Christiana Riot: an attempt to enforce a Fugitive Slave Act warrant had resulted in the killing of the slaveowner. Justice Robert Grier of the U.S. Supreme Court, as circuit justice

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that turn on questions ...

, tried the case, and instructed the jury to acquit because though the defendants might be guilty of murder or riot, they were not charged with that and were not guilty of treason. The well-publicized incident (and others like it) increased polarization over the issue of slavery, and made Stevens a prominent face of Northern abolitionism.Bond, p. 305.

Despite this trend, Stevens suffered political problems. He left the Whig caucus in December 1851, when his colleagues would not join him in seeking the repeal of the offensive elements of the Compromise. Nevertheless, he supported its unsuccessful 1852 candidate for president, General Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as Commanding General of the United States Army from 1841 to 1861, and was a veteran of the War of 1812, American Indian Wars, Mexica ...

. His political opposition, and local dislike of his stance on slavery and participation in the treason trial, made him unlikely to win renomination, and he sought only to pick his successor. His choice was defeated for the Whig nomination.

Know-Nothing and Republican

Out of office, Stevens concentrated on the practice of law in Lancaster, remaining one of the leading attorneys in the state. He stayed active in politics, and in 1854, to gain more votes for the anti-slavery movement, he joined the nativist Know Nothing Party. The members were pledged not to speak of party deliberations (thus, they knew nothing), and Stevens was attacked for his membership in a group with similar secrecy rules as the Masons. In 1855, Stevens joined the new Republican Party. Other former Whigs who were anti-slavery joined as well, including William H. Seward of New York,Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811March 11, 1874) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Massachusetts in the United States Senate from 1851 until his death in 1874. Before and during the American Civil War, he was a leading American ...

of Massachusetts, and Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

of Illinois.

Stevens was a delegate to the 1856 Republican National Convention, where he supported Justice McLean, as he had in 1832. However, the convention nominated John C. Frémont

Major general (United States), Major-General John Charles Frémont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was a United States Army officer, explorer, and politician. He was a United States senator from California and was the first History of the Repub ...

, whom Stevens actively supported in the race against his fellow Lancastrian, the Democratic candidate James Buchanan. Nonetheless, Pennsylvania helped elect Buchanan. Stevens returned to the practice of law, but in 1858, with the President and his party unpopular and the nation torn by such controversies as the Dred Scott decision, Stevens saw an opportunity to return to Congress. As the Republican nominee, he was easily elected. Democratic papers were appalled. One banner headline read, "Niggerism Triumphant."

1860 election; secession crisis

Stevens took his seat in the36th United States Congress

The 36th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1859, ...

in December 1859, only days after the hanging of John Brown, who had attacked the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry

Harpers Ferry is a historic town in Jefferson County, West Virginia, United States. The population was 269 at the 2020 United States census. Situated at the confluence of the Potomac River, Potomac and Shenandoah River, Shenandoah Rivers in the ...

hoping to cause a slave insurrection. Stevens opposed Brown's violent actions at the time, though later, he was more approving. Sectional tensions spilled over into the House, which proved unable to elect a Speaker of the United States House for eight weeks. Stevens was active in the bitter flow of invective from both sides; at one point, Mississippi Congressman William Barksdale drew a knife on him, though no blood was spilled.

With the Democrats unable to agree on a single presidential candidate, the

With the Democrats unable to agree on a single presidential candidate, the 1860 Republican National Convention

The 1860 Republican National Convention was a United States presidential nominating convention, presidential nominating convention that met May 16–18 in Chicago, Illinois. It was held to nominate the Republican Party (United States), Republic ...

in Chicago became crucial, as the nominee would be in a favorable position to become president. Prominent figures in the party, such as Seward and Lincoln, sought the nomination. Stevens continued to support the 75-year-old Justice McLean. Beginning on the second ballot, most Pennsylvania delegates supported Lincoln, helping to win him the nomination. As the Democrats put up no candidate in his district, Stevens was assured of reelection to the House and campaigned for Lincoln in Pennsylvania. Lincoln won a majority in the Electoral College. The President-elect's known opposition to the expansion of slavery caused immediate talk of secession in the southern states, a threat that Stevens had downplayed during the campaign.

Congress convened in December 1860, with several of the southern states already pledging to secede. Stevens was unyielding in opposing efforts to appease the southerners, such as the Crittenden Compromise, which would have enshrined slavery as beyond constitutional amendment. He stated, in a remark widely quoted both North and South, that rather than offer concessions because of Lincoln's election, he would see "this Government crumble into a thousand atoms," and that the forces of the United States would crush any rebellion. Despite Stevens's protests, the lame-duck Buchanan administration did little in response to the secession votes, allowing most federal resources in the South to fall into rebel hands. Even in the abolition movement, many were content to let it be so and let the South go its own way. Stevens disagreed, and the congressman was "undoubtedly pleased" by Lincoln's statement in his first inaugural address on March 4, 1861, that he would "hold, occupy and possess the property and places belonging to the Government."

American Civil War

Slavery

When the war began in April 1861, Stevens argued that the Confederates were revolutionaries to be crushed by force. He also believed that the Confederacy had placed itself beyond the protection of the U.S. Constitution by making war, and that in a reconstituted United States, slavery should have no place. Speaker Galusha Grow, whose views placed him with Stevens among the members becoming known as the Radical Republicans (for their position on slavery, as opposed to the liberal or moderate Republicans), appointed him as chairman of theHouse Ways and Means Committee

A ways and means committee is a government body that is charged with reviewing and making recommendations for government budgets. Because the raising of revenue is vital to carrying out governmental operations, such a committee is tasked with fi ...

. This position gave him power over the House's agenda.

In July 1861, Stevens secured the passage of an act to confiscate the property, including slaves, of certain rebels. In November 1861, Stevens introduced a resolution to emancipate all slaves; it was defeated. However, legislation did pass that abolished slavery in the District of Columbia and in the territories. By March 1862, to Stevens's exasperation, the most Lincoln had publicly supported was gradual emancipation in the Border states, with the slave owners compensated by the federal government.

Stevens and other radicals were frustrated at how slow Lincoln was to adopt their policies for emancipation; according to Brodie, "Lincoln seldom succeeded in matching Stevens's pace, though both were marching towards the same bright horizon." In April 1862, Stevens wrote to a friend, "As for future hopes, they are poor as Lincoln is nobody." The radicals aggressively pushed the issue, provoking Lincoln to comment: "Stevens, Sumner and assachusetts Senator Henry Wilson simply haunt me with their importunities for a Proclamation of Emancipation. Wherever I go and whatever way I turn, they are on my tail, and still in my heart, I have the deep conviction that the hour o issue onehas not yet come." The President stated that if it came to a showdown between the radicals and their enemies, he would have to side with Stevens and his fellows, and deemed them "the unhandiest devils in the world to deal with" but "with their faces... set Zionwards." Although Lincoln composed his proclamation in June and July 1862, the secret was held within his Cabinet, and the President turned aside radical pleadings to issue one until after the Union victory at the Battle of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam ( ), also called the Battle of Sharpsburg, particularly in the Southern United States, took place during the American Civil War on September 17, 1862, between Confederate General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virgi ...

in September. Stevens quickly adopted the Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War. The Proclamation had the eff ...

for use in his successful re-election campaign. When Congress returned in December, Stevens maintained his criticism of Lincoln's policies, calling them "flagrant usurpations, deserving the condemnation of the community." Stevens generally opposed Lincoln's plans to colonize freed slaves abroad, though sometimes he supported emigration proposals for political reasons. Stevens wrote to a nephew in June 1863 saying, "The slaves ought to be incited to insurrection and give the rebels a taste of real civil war."

During the Confederate incursion into the North in mid-1863 that culminated in the Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was a three-day battle in the American Civil War, which was fought between the Union and Confederate armies between July 1 and July 3, 1863, in and around Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The battle, won by the Union, ...

, Confederates twice sent parties to Stevens's Caledonia Forge. Stevens, who had been there supervising operations, was hastened away by his workers against his will. General Jubal Early looted and vandalized the Forge, causing a loss to Stevens of about $80,000. Early said that the North had done the same to southern figures and that Stevens was well known for his vindictiveness towards the South. Asked if he would have taken the congressman to Libby Prison

Libby Prison was a Confederate States of America, Confederate prison at Richmond, Virginia, during the American Civil War. In 1862 it was designated to hold officer prisoners from the Union Army, taking in numbers from the nearby Seven Days battl ...

in Richmond, Early replied that he would have hanged Stevens and divided his bones among the Confederate states.

Stevens pushed Congress to pass a constitutional amendment abolishing slavery. The Emancipation Proclamation was a wartime measure, did not apply to all slaves, and might be reversed by peacetime courts; an amendment would be slavery's end. The Thirteenth Amendmentwhich outlawed slavery and involuntary servitude except as a punishment for crimeeasily passed the Senate but failed in the House in June; fears that it might not pass delayed a renewed attempt there. Lincoln campaigned aggressively for the amendment after his re-election in 1864, and Stevens described his December annual message to Congress as "the most important and best message that has been communicated to Congress for the last 60years". Stevens closed the debate on the amendment on January 13, 1865. Illinois Representative Isaac Arnold wrote: "distinguished soldiers and citizens filled every available seat, to hear the eloquent old man speak on a measure that was to consummate the warfare of forty years against slavery."

The amendment passed narrowly after heavy pressure exerted by Lincoln himself, along with offers of political appointments from the " Seward lobby". Democrats made allegations of bribery; Stevens stated: "the greatest measure of the nineteenth century was passed by corruption, aided and abetted by the purest man in America." The amendment was declared ratified on December 18, 1865. Stevens continued to push for a broad interpretation of it that included economic justice in addition to the formal end of slavery.

After passing the Thirteenth Amendment, Congress debated the economic rights of the freedmen. Urged on by Stevens, it voted to authorize the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, with a mandate (though no funding) to set up schools and to distribute "not more than forty acres" 6 haof confiscated Confederate land to each family of freed slaves.

Financing the war

Stevens worked closely with Lincoln administration officials on legislation to finance the war. Within a day of his appointment as Ways and Means chairman, he had reported a bill for a war loan. Legislation to pay the soldiers Lincoln had already called into service and to allow the administration to borrow to prosecute the war quickly followed. These acts and more were pushed through the House by Stevens. To defeat the delaying tactics of Copperhead opponents, he had the House set debate limits as short as half a minute. Stevens played a major part in the passage of the Legal Tender Act of 1862 when for the first time, the United States issued currency backed only by its own credit, not by gold or silver. Early makeshifts to finance the war, such as war bonds, had failed as it became clear the war would not be short. In 1863, Stevens aided the passage of the National Banking Act, which required that banks limit their currency issues to the number of federal bonds that they were required to hold. The system endured for half a century until supplanted by theFederal Reserve System

The Federal Reserve System (often shortened to the Federal Reserve, or simply the Fed) is the central banking system of the United States. It was created on December 23, 1913, with the enactment of the Federal Reserve Act, after a series of ...

in 1913.

Although the Legal Tender legislation allowed for the payment of government obligations in paper money, Stevens was unable to get the Senate to agree that interest on the national debt should be paid with greenbacks. As the value of paper money dropped, Stevens railed against gold speculators, and in June 1864, after consultation with Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, proposed what became known as the Gold Billto abolish the gold market by forbidding its sale by brokers or for future delivery. It passed Congress in June; the chaos caused by the lack of an organized gold market caused the value of paper to drop even faster. Under heavy pressure from the business community, Congress repealed the bill on July 1, twelve days after its passage. Stevens was unrepentant even as the value of paper currency recovered in late 1864 amid the expectation of Union victory, proposing legislation to make paying a premium in greenbacks for an amount in gold coin a criminal offense. It did not pass.

Like most Pennsylvania politicians of both parties, Stevens was a major proponent of tariffs, which increased from 19% to 48% from fiscal 1861 to fiscal 1865. According to activist Ida Tarbell

Ida Minerva Tarbell (November 5, 1857January 6, 1944) was an American writer, Investigative journalism, investigative journalist, List of biographers, biographer, and lecturer. She was one of the leading muckrakers and reformers of the Progre ...

in "The Tariff in Our Times:" mportduties were never too high for tevens particularly for iron, for he was a manufacturer and it was often said in Pennsylvania that the duties he advocated in no way represented the large iron interests of the state, but were hoisted to cover the needs of his own... badly managed works."

Reconstruction

Problem of reconstructing the South

As Congress debated how the U.S. would be organized after the war, the status of freed slaves and former Confederates remained undetermined.Bryant-Jones, p. 148 Stevens stated that what was needed was a "radical reorganization of southern institutions, habits, and manners." Stevens, Sumner, and other radicals argued that the southern states should be treated like conquered provinces without constitutional rights. Lincoln, on the contrary, said that only individuals, not states, had rebelled. In July 1864, Stevens pushed Lincoln to sign the Wade–Davis Bill, which required at least half of prewar voters to sign an oath of loyalty for a state to gain readmission. Lincoln, who advocated his more lenient ten percent plan, pocket vetoed it. Stevens reluctantly voted for Lincoln at the convention of the National Union Party, a coalition of Republicans and War Democrats. He would have preferred to vote for the sitting vice president,Hannibal Hamlin

Hannibal Hamlin (August 27, 1809 – July 4, 1891) was an American politician and diplomat who was the 15th vice president of the United States, serving from 1861 to 1865, during President Abraham Lincoln's first term. He was the first Republi ...

, as Lincoln's running mate in 1864. However, his delegation voted to cast the state's ballots for the administration's favored candidate, Military Governor of Tennessee Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. The 16th vice president, he assumed the presidency following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a South ...

, a War Democrat who had been a Tennessee senator and elected governor. Stevens was disgusted at Johnson's nomination, complaining, "can't you get a candidate for Vice-President without going down into a damned rebel province for one?" Stevens campaigned for the Lincoln–Johnson ticket; it was elected, as was Stevens for another term in the House. When in January 1865 Congress learned that Lincoln had attempted peace talks with Confederate leaders, an outraged Stevens declared that if the American electorate could vote again, they would elect General Benjamin Butler instead of Lincoln.

Presidential Reconstruction

Before leaving town after Congress adjourned in March 1865, Stevens privately urged Lincoln to press the South hard militarily, though the war was ending. Lincoln replied, "Stevens, this is a pretty big hog we are trying to catch and to hold when we catch him. We must take care that he does not slip away from us." Never to see Lincoln again, Stevens left with "a homely metaphor but no real certainty of having left as much as a thumbprint on Lincoln's policy." On the evening of April 14, 1865, Lincoln was assassinated by Confederate sympathizerJohn Wilkes Booth

John Wilkes Booth (May 10, 1838April 26, 1865) was an American stage actor who Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, assassinated United States president Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C., on April 14, 1865. A member of the p ...

. Stevens did not attend the ceremonies when Lincoln's funeral train stopped in Lancaster; he was said to be ill. Trefousse speculated that he had avoided the rites for other reasons. According to Lincoln biographer Carl Sandburg, Stevens stood at a railroad bridge and lifted his hat.

In May 1865, Andrew Johnson began what came to be known as " Presidential Reconstruction": recognizing a provisional government of Virginia led by Francis Harrison Pierpont, calling for other former rebel states to organize constitutional conventions, declaring amnesty for many southerners, and issuing individual pardons to even more. Johnson did not push the states to protect the rights of freed slaves, and immediately began to counteract the land reform policies of the Freedmen's Bureau. These actions outraged Stevens and others who took his view. The radicals saw that freedmen in the South risked losing the economic and political liberty necessary to sustain emancipation from slavery. They began to call for universal male suffrage

Universal manhood suffrage is a form of voting rights in which all adult male citizens within a political system are allowed to vote, regardless of income, property, religion, race, or any other qualification. It is sometimes summarized by the sl ...

and continued their demands for land reform.

Stevens wrote to Johnson that his policies were gravely damaging the country and that he should call a special session of Congress, which was not scheduled to meet until December. When his communications were ignored, Stevens began to discuss with other radicals how to prevail over Johnson when the two houses convened. Congress has the constitutional power to judge whether those seeking to be its members are properly elected; Stevens urged that no senators or representatives from the South be seated.Brodie, pp. 225–30, 234–39 He argued that the states should not be readmitted as thereafter Congress would lack the power to force race reform.

In September, Stevens gave a widely reprinted speech in Lancaster in which he set forth what he wanted for the South. He proposed that the government confiscate the estates of the largest 70,000 landholders there, those who owned more than . Much of this property he wanted distributed in plots of to the freedmen; other lands would go to reward loyalists both North and South, or to meet government obligations. He warned that under the President's plan, the southern states would send rebels to Congress who would join with northern Democrats and Johnson to govern the nation and perhaps undo emancipation.

Through late 1865, the southern states held white-only balloting and, in congressional elections, chose many former rebels, most prominently Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens

Alexander Hamilton Stephens (February 11, 1812 – March 4, 1883) was an American politician who served as the first and only vice president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865, and later as the 50th governor of Georgia from 1882 unti ...

, voted as senator by the Georgia Legislature. Violence against African-Americans was common and unpunished in the South; the new legislatures enacted Black Codes, depriving the freedmen of most civil rights. These actions, seen as provocative in the North, both privately dismayed Johnson and helped turn northern public opinion against the president. Stevens proclaimed that "This is not a 'white man's Government'!... To say so is political blasphemy, for it violates the fundamental principles of our gospel of liberty."

Congressional Reconstruction

By this time, Stevens was past age seventy and in poor health; he was carried everywhere in a special chair. When Congress convened in early December 1865, Stevens made arrangements with the Clerk of the House that when the roll was called, the names of the Southern electees be omitted. The Senate also excluded Southern claimants. A new congressman, Ohio's Rutherford B. Hayes, described Stevens: "He is radical throughout, except, I am told, he don't believe in hanging. He is leader."

As the responsibilities of the Ways and Means chairman had been divided, Stevens took the post of Chairman of the House Committee on Appropriations, retaining control over the House's agenda. Stevens focused on legislation that would secure the freedom promised by the newly ratified Thirteenth Amendment.Soifer, p. 1616 He proposed and then co-chaired the Joint Committee on Reconstruction with Maine Senator William Pitt Fessenden. This body, also called the Committee of Fifteen, investigated conditions in the South. It heard not only of the violence against African-Americans but against Union loyalists and against what southerners termed "