Terence Atherton on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Arthur Terence Atherton (3 August 1902 – 15 July 1942) was a British

Despite careful planning, Operation Hydra failed completely. The presence of former Yugoslav Royal Air Force officer implied strong links to the

Despite careful planning, Operation Hydra failed completely. The presence of former Yugoslav Royal Air Force officer implied strong links to the

journalist

A journalist is a person who gathers information in the form of text, audio or pictures, processes it into a newsworthy form and disseminates it to the public. This is called journalism.

Roles

Journalists can work in broadcast, print, advertis ...

, War correspondent

A war correspondent is a journalist who covers stories first-hand from a war, war zone.

War correspondence stands as one of journalism's most important and impactful forms. War correspondents operate in the most conflict-ridden parts of the wor ...

and a newspaper proprietor of various English language publications in Belgrade between 1931 and 1941. He was also a British Special Operations Executive

Special Operations Executive (SOE) was a British organisation formed in 1940 to conduct espionage, sabotage and reconnaissance in German-occupied Europe and to aid local Resistance during World War II, resistance movements during World War II. ...

intelligence officer for Section D and an espionage agent, both in pre-war Belgrade

Belgrade is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city of Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers and at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin, Pannonian Plain and the Balkan Peninsula. T ...

and during World War II in Yugoslavia

World War II in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia began on 6 April 1941, when the country was Invasion of Yugoslavia, invaded and swiftly conquered by Axis powers, Axis forces and partitioned among Nazi Germany, Germany, Fascist Italy (1922–1943), It ...

. The former journalist led a Commando Mission behind enemy lines during World War II and died in mysterious circumstances.

Early life

He was the son of Douglas Harold Atherton (1861-1924) and Letitia Elizabeth Haigh (1861-1933). His parents married inLindley, North Yorkshire

Lindley is a village and civil parish in the county of North Yorkshire, England. It is near Lindley Wood Reservoir and 1 mile north of Otley. In 2001 the parish had a population of 52. The population was estimated at 50 in 2015. In the 2011 cen ...

on 24 November 1887. He was born in Wavertree

Wavertree is a district and suburb of Liverpool, in the county of Merseyside, England. It is a Ward (country subdivision), ward of Liverpool City Council, and its population at the United Kingdom Census 2011, 2011 census was 14,772. Located to ...

, Liverpool

Liverpool is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. It is situated on the eastern side of the River Mersey, Mersey Estuary, near the Irish Sea, north-west of London. With a population ...

, and had 3 elder siblings. His paternal ancestors were gentlemen farmers and his maternal grandfather was a solicitor.

Career

From 1919, Atherton was employed by the Bank of Liverpool and Martins as a bank clerk. He enlisted within theRoyal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

on 27 November 1925. He joined the service as an aircraftman

Aircraftman (AC) or aircraftwoman (ACW) was formerly the lowest rank in the British Royal Air Force (RAF) and is still in use by the air forces of several other Commonwealth countries. In RAF slang, aircraftmen were sometimes called "erks".

Air ...

second class (AC2), and would have performed air mechanical duties. He left the service after less than 280 days.

Atherton went on to become a leading British journalist in Belgrade

Belgrade is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city of Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers and at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin, Pannonian Plain and the Balkan Peninsula. T ...

, Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was a country in Southeast Europe, Southeast and Central Europe that existed from 1918 until 1941. From 1918 to 1929, it was officially called the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, but the term "Yugoslavia" () h ...

where he remained for a number of years. It is a mystery how within 5 years he became a foreign correspondent in a European capital city. It is possible that Atherton was residing in Yugoslavia prior to 1930. He was the Belgrade correspondent for The Daily Mail

The ''Daily Mail'' is a British daily middle-market tabloid conservative newspaper founded in 1896 and published in London. , it has the highest circulation of paid newspapers in the UK. Its sister paper ''The Mail on Sunday'' was launch ...

and the Daily Dispatch

for ten years. He traveled extensively throughout Yugoslavia and Bulgaria, and was fluent in Serbo-Croatian

Serbo-Croatian ( / ), also known as Bosnian-Croatian-Montenegrin-Serbian (BCMS), is a South Slavic language and the primary language of Serbia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Montenegro. It is a pluricentric language with four mutually i ...

. He was also the chief editor and founder of the South Slav Herald in Belgrade in 1931, and owner and publisher of the Balkan Herald founded in 1934. His assistant editor was Alexander Simić-Stevens who had also been the Belgrade Correspondent for the Evening Standard and The Star.

Atherton was an intelligence agent for Section D of the British Special Operations Executive in pre-war Belgrade. His cover was a journalist and newspaperman. His assistant editor was also a member of SOE. Atherton married a Yugoslavian National from Sarajevo

Sarajevo ( ), ; ''see Names of European cities in different languages (Q–T)#S, names in other languages'' is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Bosnia and Herzegovina, largest city of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with a population of 2 ...

, Bosnia

Bosnia and Herzegovina, sometimes known as Bosnia-Herzegovina and informally as Bosnia, is a country in Southeast Europe. Situated on the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula, it borders Serbia to the east, Montenegro to the southeast, and Croatia to th ...

, of Muslim faith.

By 1934, his articles on a Yugoslavian perspective were being published around the world. He reported on Princess Marina of Greece and Denmark

Princess Marina, Duchess of Kent (born Princess Marina of Greece and Denmark, ; 27 August 1968) was a Greek royal family, Greek and Danish princess by birth and a British princess by marriage. She was a daughter of Prince Nicholas of Greece and ...

’s engagement to Prince George, Duke of Kent

Prince George, Duke of Kent (George Edward Alexander Edmund; 20 December 1902 – 25 August 1942) was a member of the British royal family, the fourth son of King George V and Queen Mary. He was a younger brother of kings Edward VIII and George ...

and their gift from Alexander I of Yugoslavia

Alexander I Karađorđević (, ; – 9 October 1934), also known as Alexander the Unifier ( / ), was King of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes from 16 August 1921 to 3 October 1929 and King of Yugoslavia from 3 October 1929 until his assassinati ...

, just one month before the King of Yugoslavia was assassinated in Marseille

Marseille (; ; see #Name, below) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Bouches-du-Rhône and of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region. Situated in the ...

whilst on a state visit

A state visit is a formal visit by the head of state, head of a sovereign state, sovereign country (or Governor-general, representative of the head of a sovereign country) to another sovereign country, at the invitation of the head of state (or ...

to France.

Atherton, whilst correspondent for the Daily Mail and editor of the Balkan Herald was based at Dobrašina 12, Belgrade, and would write to editors of London papers with anecdotes of life in the Balkan

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

city. On 25 November 1935, Atherton reported to the Editor of The Times of London of the donation of animals from Tierpark Hagenbeck

The Tierpark Hagenbeck is a zoo in Stellingen, Hamburg, Germany. The collection began in 1863 with animals that belonged to Carl Hagenbeck Sr. (1810–1887), a fishmonger who became an amateur animal collector. The park itself was founded by Ca ...

to Prince Paul of Yugoslavia

Prince Paul of Yugoslavia, also known as Paul Karađorđević (, English transliteration: ''Paul Karageorgevich''; 27 April 1893 – 14 September 1976), was prince regent of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia during the minority of King Peter II. Paul w ...

. Whereas the Mayor of Belgrade, Vlada Ilić appealed to the United Kingdom for gifts of specimens, preferably in pairs, for a much anticipated Belgrade Zoo

Beo zoo vrt ( sr-Cyrl, Бео зоо врт), also known as Vrt dobre nade ( Serbian Cyrilic: Врт добре наде, ''The Garden of good hope''), is a publicly owned zoo located in Kalemegdan Park, downtown of Belgrade, Serbia. Established ...

. These stories and many others by Atherton are both intriguing and insightful reports during the inter-war period. Atherton’s journalistic approach to another editor, under the banner of either "Points from Letters" or "Letters to Editor" became more frequent leading up to the German invasion with titles like "Wolves of the Balkans" on 3 March 1937, and therefore each of these letters may contain a hidden message. Alexander Simić-Stevens, who Atherton tutored returned to London and subsequently joined SOE.

The following year, the German annexation of Austria gave Yugoslavia a common border with Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

. Atherton continued in Yugoslavia after the country declared itself neutral at the outbreak of the World War II, writing about a dangerous level of plentiful food in the Balkan countries during December 1939, in comparison to that in Nazi Germany.

During March 1940, Atherton returned to writing about royalty. His articles were published around the world. He reported on a wedding talking place in Belgrade between Prince Nicholas Wladimirovitch Orloff, (who divorced Princess Nadejda Petrovna of Russia the previous week), and an American actress, successful only in Germany, Mary R. Shuck went by the stage name of Marina Marshall. The Russian noble had been close to Nazi-Germany, and only left Berlin because of the

Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, officially the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, and also known as the Hitler–Stalin Pact and the Nazi–Soviet Pact, was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Ge ...

. When he eventually emigrated to the United States he was suspected by U.S. agencies as being Lord Haw-Haw

Lord Haw-Haw was a nickname applied to William Joyce and several other people who broadcast Nazi propaganda to the United Kingdom from Germany during the Second World War. The broadcasts opened with "Germany calling, Germany calling," spoken i ...

, as he was responsible for broadcasting Nazi Propaganda in English over the airwaves before the war. The article refers to the nobleman's admiration of George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from the 188 ...

, who at the time admired Mussolini and Stalin. Atherton's article is likely to contain a coded message.

Atherton went to Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

to cover how the Metaxas Regime

Metaxās or Metaxa may refer to:

Places

* Metaxas Line, fortifications in northeastern Greece in 1935–1940

* Metaxas, Greece, a village in the Greek region of Macedonia

* Metaxas Regime or 4th of August Regime, a short-lived authoritarian reg ...

were combating the Italian incursions from Albania

Albania ( ; or ), officially the Republic of Albania (), is a country in Southeast Europe. It is located in the Balkans, on the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea, and shares land borders with Montenegro to ...

during November 1940 in what became known as the Greco-Italian War

The Greco-Italian War (), also called the Italo-Greek War, Italian campaign in Greece, Italian invasion of Greece, and War of '40 in Greece, took place between Italy and Greece from 28 October 1940 to 23 April 1941. This conflict began the Balk ...

. Atherton remained just three days at the front before returning to Bitola

Bitola (; ) is a city in the southwestern part of North Macedonia. It is located in the southern part of the Pelagonia valley, surrounded by the Baba, Nidže, and Kajmakčalan mountain ranges, north of the Medžitlija-Níki border crossing ...

, previously known as Monastir.

Atherton was in-country when the Yugoslav prince regent

A prince regent or princess regent is a prince or princess who, due to their position in the line of succession, rules a monarchy as regent in the stead of a monarch, e.g., as a result of the sovereign's incapacity (minority or illness) or ab ...

yielded to pressure from Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

and declared the Yugoslav accession to the Tripartite Pact

On 25 March 1941, Yugoslavia signed the Tripartite Pact with the Axis powers. The agreement was reached after months of negotiations between Germany and Yugoslavia and was signed at the Belvedere in Vienna by Joachim von Ribbentrop, German fore ...

on 25 March 1941. However a pro-British coup d'état

A coup d'état (; ; ), or simply a coup

, is typically an illegal and overt attempt by a military organization or other government elites to unseat an incumbent leadership. A self-coup is said to take place when a leader, having come to powe ...

deposed the regent and declared Peter II of Yugoslavia

Peter II Karađorđević (; 6 September 1923 – 3 November 1970) was the last King of Yugoslavia, reigning from October 1934 until he was deposed in November 1945. He was the last reigning member of the Karađorđević dynasty.

The eldest ...

as the new king, two days later. This event was encouraged by SOE, however the level of Atherton's involvement is unknown, since he effectively lead a double life.

The SOE office in Belgrade that Atherton was attached to, had gone to significant lengths to support the opposition to the Dragiša Cvetković

Dragiša Cvetković ( sr-cyr, Драгиша Цветковић; 15 January 1893 – 18 February 1969) was a Yugoslav politician active in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. He served as the Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia from 1939 to 1941 ...

government, which antagonised and undermined the hard-won balance in Yugoslav politics that Cvetković's short lived government represented. SOE Belgrade was entangled with pro-Serb policies and interests, and disregarded, or underestimated warnings from SOE Zagreb

Zagreb ( ) is the capital (political), capital and List of cities and towns in Croatia#List of cities and towns, largest city of Croatia. It is in the Northern Croatia, north of the country, along the Sava river, at the southern slopes of the ...

and British diplomats in that city, who may have been able to provide a clearer analysis of the challenges of a politically complex country, at the time dealing with diverse ethnicities, religious sensitivities and shifting politic allegiances. However rivalries and confusion and lack of continued interest by the British Foreign Office

The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) is the ministry of foreign affairs and a ministerial department of the government of the United Kingdom.

The office was created on 2 September 2020 through the merger of the Foreign an ...

in this region of Europe did little to help matters of diplomacy in Atherton's adoptive home. The level of Atherton's role and involvement with SOE HQ in Belgrade is unknown; however given that he was allegedly married to a Bosnian Muslim, proves that he was less "Belgrade centric", and therefore may have not been so favourable to Serb desire for supremacy over the Croats

The Croats (; , ) are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and other neighboring countries in Central Europe, Central and Southeastern Europe who share a common Croatian Cultural heritage, ancest ...

, Slovenes

The Slovenes, also known as Slovenians ( ), are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Slovenia and adjacent regions in Italy, Austria and Hungary. Slovenes share a common ancestry, Slovenian culture, culture, and History of Slove ...

and Muslims

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

under his watch.

The German bombing of Belgrade, which commenced during the early hours of 6 April 1941, and lasted three days, killing 17,000 people, was known as Operation Punishment

The German bombing of Belgrade, codenamed Operation Retribution () or Operation Punishment, was the April 1941 German bombing of Belgrade, the capital of Yugoslavia, in retaliation for the coup d'état that overthrew the government that had si ...

. Atherton was forced to leave his adoptive city on the second day, his home for over 10 years, with retreating Yugoslav forces, as Axis forces had entered the country and closing in on the capital. His mission was to remain close to Yugoslav leaders until the armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from t ...

, evade capture by Axis-forces, and exit the country by any means and reach British troops in Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

.

Axis invasion and escape from the Kingdom of Yugoslavia

Atherton successfully escaped from Yugoslavia after the invasion byAxis forces

The Axis powers, originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis and also Rome–Berlin–Tokyo Axis, was the military coalition which initiated World War II and fought against the Allies of World War II, Allies. Its principal members were Nazi Ge ...

in April 1941, teaming up with 3 American foreign correspondents; Robert St. John

Robert William St. John (March 9, 1902 – February 6, 2003) was an American writer, broadcasting, broadcaster, and journalist.

Soyer was a member of the Writers and Artists for Peace in the Middle East, a pro-Israel group. In 1984, he signed a ...

(1902-2003) from Chicago, a writer for the Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American not-for-profit organization, not-for-profit news agency headquartered in New York City.

Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association, and produces news reports that are dist ...

; Leigh White (1914-1968) from Vermont, a writer for the New York Post

The ''New York Post'' (''NY Post'') is an American Conservatism in the United States, conservative

daily Tabloid (newspaper format), tabloid newspaper published in New York City. The ''Post'' also operates three online sites: NYPost. ...

and the Columbia Broadcasting System

CBS Broadcasting Inc., commonly shortened to CBS (an abbreviation of its original name, Columbia Broadcasting System), is an American commercial broadcast television and radio network serving as the flagship property of the CBS Entertainme ...

; and Russell Hill of The New York Herald Tribune

The ''New York Herald Tribune'' was a newspaper published between 1924 and 1966. It was created in 1924 when Ogden Mills Reid of the ''New York Tribune'' acquired the ''New York Herald''. It was regarded as a "writer's newspaper" and competed ...

, on a 700-mile journey to Greece using multiple means of transport. He and 2 of his companions, St. John and Hill, arrived in Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

, a month later, with White remaining in hospital in Greece.

In order to evacuate from Belgrade, Atherton acquired a car (a small blue Opel coach) and drove first to Banja Koviljača

Banja Koviljača ( sr-cyrl, Бања Ковиљача, ) is a popular tourist spot and spa town located in the city of Loznica, Serbia. Situated on the west border of Serbia by the Drina River and from Belgrade, it is the oldest spa town in Serbi ...

and then onto Užice

Užice ( sr-cyr, Ужице, ) is a List of cities in Serbia, city and the administrative centre of the Zlatibor District in western Serbia. It is located on the banks of the river Đetinja. According to the 2022 census, the city proper has a popu ...

and to Zvornik

Zvornik ( sr-cyrl, Зворник, ) is a city in Republika Srpska, Bosnia and Herzegovina. In 2013, it had a population of 58,856 inhabitants. Zvornik is located on the Drina River, on the eastern slopes of Majevica mountain, at the altitude of ...

following the retreating Yugoslav government. Atherton would later write that he was in the presence of the new Prime Minister, General Dušan Simović

Dušan Simović (; 28 October 1882 – 26 August 1962) was a Yugoslav Serb Army general (Kingdom of Yugoslavia), army general who served as Chief of the General Staff (Yugoslavia)#Royal Yugoslav Armed Forces (1920–1941), Chief of the General Sta ...

, as he witnessed "first hand", the collapse of the government of national unity, from a small town in Bosnia, within less than 10 days. Atherton later revealed in his articles as a war correspondent, that from the moment the Yugoslav government offices in Belgrade were destroyed in air raids, the only means of communication for Simovic with the Royal Yugoslav Army

The Yugoslav Army ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, Jugoslovenska vojska, JV, Југословенска војска, ЈВ), commonly the Royal Yugoslav Army, was the principal Army, ground force of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. It existed from the establishment of ...

and other forces, was by using a small British radio.

SOE's priority was to assist in ensuring Peter II of Yugoslavia

Peter II Karađorđević (; 6 September 1923 – 3 November 1970) was the last King of Yugoslavia, reigning from October 1934 until he was deposed in November 1945. He was the last reigning member of the Karađorđević dynasty.

The eldest ...

escaped on a plane to Greece before the unconditional surrender

An unconditional surrender is a surrender in which no guarantees, reassurances, or promises (i.e., conditions) are given to the surrendering party. It is often demanded with the threat of complete destruction, extermination or annihilation.

Anno ...

. Atherton, realizing the severity of his own situation, and of his American companions, continued overland onto Cetinje

Cetinje ( cnr-Cyrl, Цетиње, ) is a List of cities and towns in Montenegro, town in Montenegro. It is the former royal capital ( cnr-Latn-Cyrl, prijestonica, приjестоница, separator=" / ") of Montenegro and is the location of sev ...

, and then onto the coastal port of Budva

Budva (Cyrillic script, Cyrillic: Будва, or ) is a town in the Coastal Montenegro, Coastal region of Montenegro. It had 27,445 inhabitants as of 2023, and is the centre of Budva Municipality. The coastal area around Budva, called the Budv ...

in Montenegro

, image_flag = Flag of Montenegro.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Montenegro.svg

, coa_size = 80

, national_motto =

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map = Europe-Mont ...

as an Italian occupation force began entering the ancient walled town.

The invasion of Yugoslavia ended when an armistice was signed on 17 April 1941, which came into effect at noon on 18 April. Shortly prior to this date, in Budva, Atherton seized a small sardine boat, in exchange of his Opel car, and remained hidden in the port until it was safe to leave. With no charts or a compass; only 12 gallons of fuel, some road maps, and a gunny sack

A gunny sack, also known as a gunny shoe, burlap sack, hessian sack or tow sack, is a large Bag, sack, traditionally made of burlap (Hessian fabric) formed from jute, hemp, sisal, or other natural fibres, usually in the crude Spinning (textile ...

of bread, Atherton set off with his 3 companions on a dangerous voyage through Albanian coastal waters, a region subject to invasion

An invasion is a Offensive (military), military offensive of combatants of one geopolitics, geopolitical Legal entity, entity, usually in large numbers, entering territory (country subdivision), territory controlled by another similar entity, ...

and now in control of the Italian forces, in an attempt to safely reach the Greek island of Corfu

Corfu ( , ) or Kerkyra (, ) is a Greece, Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands; including its Greek islands, small satellite islands, it forms the margin of Greece's northwestern frontier. The island is part of the Corfu (regio ...

.

His traveling companion, St John was the only experienced sailor, who later recounted the tale of treacherous weather conditions and the groups imminent danger when an Italian Navy

The Italian Navy (; abbreviated as MM) is one of the four branches of Italian Armed Forces and was formed in 1946 from what remained of the ''Regia Marina'' (Royal Navy) after World War II. , the Italian Navy had a strength of 30,923 active per ...

vessel accompanying troop movement ships spotted their small open boat, and subsequently trained their guns on them in proximity to Durrës

Durrës ( , ; sq-definite, Durrësi) is the List of cities and towns in Albania#List, second most populous city of the Albania, Republic of Albania and county seat, seat of Durrës County and Durrës Municipality. It is one of Albania's oldest ...

. St. John and the others placed a bloodstained American flag so that it was visible; and after several tense minutes, they were eventually waved on. This quick thinking by one of the Americans may have saved Atherton from being detained by the Italian Navy, since as a Briton, he was considered to be an enemy national.

The voyage south coincided with the

German invasion of Greece

The German invasion of Greece or Operation Marita (), were the attacks on Kingdom of Greece, Greece by Kingdom of Italy, Italy and Nazi Germany, Germany during World War II. The Italian invasion in October 1940, which is usually known as the Gr ...

. Having reached Corfu, the Greek naval authorities were initially dubious such a trip was even possible, given the recent weather conditions. The authorities had more pressing matters than 4 journalists in a sardine boat. Eventually the local authorities permitted them to sail south, where they were subsequently machine gunned by Italian fighter planes, and their vessel quickly sank. Atherton and his companions were rescued by a small Greek fishing trawler, which also fell victim to an air attack; this time by 5 Stukageschwader Stuka

The Junkers Ju 87, popularly known as the "Stuka", is a German dive bomber and ground-attack aircraft. Designed by Hermann Pohlmann, it first flew in 1935. The Ju 87 made its combat debut in 1937 with the Luftwaffe's Condor Legion during the ...

dive bomber

A dive bomber is a bomber aircraft that dives directly at its targets in order to provide greater accuracy for the bomb it drops. Diving towards the target simplifies the bomb's trajectory and allows the pilot to keep visual contact througho ...

s, and suffered fatalities. During this incident Atherton was wounded in a knee and White's femur was shattered.

Once in the port of Patras

Patras (; ; Katharevousa and ; ) is Greece's List of cities in Greece, third-largest city and the regional capital and largest city of Western Greece, in the northern Peloponnese, west of Athens. The city is built at the foot of Mount Panachaiko ...

, situated on the western Peloponnese coast, Atherton and his companions promptly boarded a train for headed east to Corinth

Corinth ( ; , ) is a municipality in Corinthia in Greece. The successor to the ancient Corinth, ancient city of Corinth, it is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Sin ...

. They knew they needed to join a British evacuation since the Axis forces were advancing swiftly in the Balkans.However German planes machine gunned the passenger train, wounding two of Atherton's American companions. After two days overland travel to a small port near Argos

Argos most often refers to:

* Argos, Peloponnese, a city in Argolis, Greece

* Argus (Greek myth), several characters in Greek mythology

* Argos (retailer), a catalogue retailer in the United Kingdom

Argos or ARGOS may also refer to:

Businesses

...

, all 4 journalists had received either gunshot or shrapnel injuries during their difficult journey through the Peloponnese with air attacks as they traveled along the Corinth–Argos road, racing to meet British evacuation ships destined for Crete and Egypt. Atherton's traveling companion, Leigh White was later hospitalised in Argos, and was not able to evacuate with Atherton before this ancient city capitulated to Axis forces on 27 April 1941. However, Atherton ensured his other two American companions were evacuated with him on HMS Havock

Six vessels of the Royal Navy have been named HMS ''Havock'', including:

* was a 12-gun gun-brig launched in 1805. She became a lightvessel in 1821, a watch vessel in 1834 and was broken up in 1859.

* was a mortar vessel launched in 1855, and ren ...

, the last British destroyer to leave Greece, alongside British and Commonwealth troops and other foreign nationals to the island of Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

, and onto Alexandria. Atherton was fortunate not to have been a victim of the Slamat disaster

The ''Slamat'' disaster is a succession of three related shipwrecks during the Battle of Greece on 27 April 1941. The Dutch troopship and the Royal Navy destroyers and sank as a result of air attacks by ''Luftwaffe'' Junkers Ju 87 dive bombers ...

, having boarded HMS Havock which survived the voyage.

Atherton's tale of his daring escape was reported around the world on 3 May 1941. The American weekly news magazine Newsweek

''Newsweek'' is an American weekly news magazine based in New York City. Founded as a weekly print magazine in 1933, it was widely distributed during the 20th century and has had many notable editors-in-chief. It is currently co-owned by Dev P ...

published an article about Atherton and three other foreign correspondents; Russell Hill, Leigh White, and Robert St. John

Robert William St. John (March 9, 1902 – February 6, 2003) was an American writer, broadcasting, broadcaster, and journalist.

Soyer was a member of the Writers and Artists for Peace in the Middle East, a pro-Israel group. In 1984, he signed a ...

, who together escaped from Yugoslavia, before it was fully occupied by Axis forces, describing it as "400-miles voyage of four trapped correspondents".

Preparations to a clandestine return into Axis occupied Yugoslavia

Atherton's service to the Special Operations Executive (SOE) took precedence over his journalism during World War II. There are no records of Atherton returning to the UK. During World War II, British troops usedEgypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

as a base for their operations throughout the region. In May 1941, Atherton would have been debriefed by SOE after safely evacuating to Alexandria.

Atherton had a deep knowledge of the Balkans, and was able to fully converse in the South Slavic languages

The South Slavic languages are one of three branches of the Slavic languages. There are approximately 30 million speakers, mainly in the Balkans. These are separated geographically from speakers of the other two Slavic branches (West Slavic la ...

. His level of proficiency is unknown as to whether he was able to pass as a native speaker. However, in the Balkans, a lesser degree of fluency was required as the resistance groups concerned were already in open rebellion and a clandestine existence was unnecessary.

Whilst in Cairo

Cairo ( ; , ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Egypt and the Cairo Governorate, being home to more than 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, L ...

, Atherton enlisted as an Army Mayor; Service number 234206, ceasing his journalism profession, and was likely trained by the Intelligence Corps. He was

appointed to lead a team of specialist field operatives for a future covert mission into Axis controlled Yugoslavia. He was 38 years of age.

SOE needed Atherton's skills. He had proven himself in his daring escape from the enemy. He had sound knowledge of Yugoslavia; and the British Government was deficient having adequate in-country knowledge. Atherton needed to be willing to be adept to negotiating and engaging with potential working partners for the British. He was fluent in the language. He has outdoor survival skills and initiative. He had a history of military service and above all was an SOE agent in Belgrade which made him highly suited to the task.

The British already facilitated contact between Draža Mihailović

Dragoljub "Draža" Mihailović ( sr-Cyrl, Драгољуб "Дража" Михаиловић; 27 April 1893 – 17 July 1946) was a Yugoslavs, Yugoslav Serb general during World War II. He was the leader of the Chetniks, Chetnik Detachments ...

and the Yugoslav government-in-exile

The Government of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in Exile ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, Vlada Kraljevine Jugoslavije u egzilu, Влада Краљевине Југославије у егзилу) was an official government-in-exile of Yugoslavia, headed by King ...

in London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

; and the young King of Yugoslavia in exile in London, and his advisors saw Mihailović as a future prime minister. However, due to the deteriorated relations between this Serb

The Serbs ( sr-Cyr, Срби, Srbi, ) are a South Slavic ethnic group native to Southeastern Europe who share a common Serbian ancestry, culture, history, and language. They primarily live in Serbia, Kosovo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia ...

general, the self-appointed leader of the Chetnik Detachments of the Yugoslav Army, and the British liaison officer, Duane "Bill" Hudson, stationed temporarily outside of Mihailović's headquarters and engaging with partisans as part of Operation Bullseye whilst under radio silence, the SOE, not having heard from Hudson, decided at the end of 1941 to send a second mission to open up channels of communication with partisans, as well as maintain a connection with the Chetniks, and keep to script. Since Atherton was strongly anti-Communist and spoke the local language well, he was the perfect candidate for such a mission.

Atherton would have known the risks involved. SOE's first mission '' Operation Disclaim '' was not successful after its members, who parachuted in to Romanija

Romanija ( sr-cyrl, Романија) is a mountain, karst plateau, and geographical region in eastern Bosnia and Herzegovina, including numerous villages and towns, such as Pale, Sokolac, Rogatica and Han Pijesak. Its highest point is Velik ...

and were captured by the Croatian authorities who handed them over to the Germans. Atherton was chosen to lead SOE's second attempt; Operation Hydra which departed Alexandria, Egypt in January 1942, a month before James Klugmann

Norman John Klugmann (27 February 1912 – 14 September 1977), generally known as James Klugmann, was a leading British Communist writer and WW2 Soviet Spy, who became the official historian of the Communist Party of Great Britain.

Background ...

took on the Yugoslav Section of SOE as an intelligence and coordination officer, based in Cairo. Atherton and his team were to disembark from a submarine on the Budva Riviera

The Budvanian Riviera () is a long strip of the Adriatic

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending ...

at the beginning of February 1942, using the same method to deploy Hudson the previous year. A parallel team code name Henna consisted of 2 officers, headed by Lieutenant Rapojec were to be landed on the island of Mljet

Mljet () is the southernmost and easternmost of the larger Adriatic islands of the Dalmatia region of Croatia. In the west of the island is the Mljet National Park.

Population

In the 2011 census, Mljet had a population of 1,088. Ethnic Croats mad ...

.

Operation Hydra

Operation Hydra (Yugoslavia) was a failed attempt by the British duringWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

to develop contact with the Yugoslav Partisans

The Yugoslav Partisans,Serbo-Croatian, Macedonian language, Macedonian, and Slovene language, Slovene: , officially the National Liberation Army and Partisan Detachments of Yugoslavia sh-Latn-Cyrl, Narodnooslobodilačka vojska i partizanski odr ...

, the leading Communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, di ...

-led Anti-fascist

Anti-fascism is a political movement in opposition to fascist ideologies, groups and individuals. Beginning in European countries in the 1920s, it was at its most significant shortly before and during World War II, where the Axis powers were op ...

resistance group

led by Josip Broz Tito

Josip Broz ( sh-Cyrl, Јосип Броз, ; 7 May 1892 – 4 May 1980), commonly known as Tito ( ; , ), was a Yugoslavia, Yugoslav communist revolutionary and politician who served in various positions of national leadership from 1943 unti ...

, in Montenegro

, image_flag = Flag of Montenegro.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Montenegro.svg

, coa_size = 80

, national_motto =

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map = Europe-Mont ...

in February 1942. Special Operations Executive agents, including a former junior officer of the Royal Yugoslav Air Force

The Royal Yugoslav Air Force ( sh-Latn, Jugoslovensko kraljevsko ratno vazduhoplovstvo, JKRV; sh-Cyrl, Југословенско краљевско ратно ваздухопловство, ЈКРВ; (, JKVL); lit. "Yugoslav royal war aviatio ...

were to be put ashore at Perazića Do, just north of Petrovac, Budva

Petrovac (, , ), also known as Petrovac na Moru ().

Petrovac, is a small town in Coastal region of Montenegro. It is located on the coast between Budva and Bar, where the old mountain road from Podgorica reaches the coast is being the most fam ...

, Montenegro

, image_flag = Flag of Montenegro.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Montenegro.svg

, coa_size = 80

, national_motto =

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map = Europe-Mont ...

.

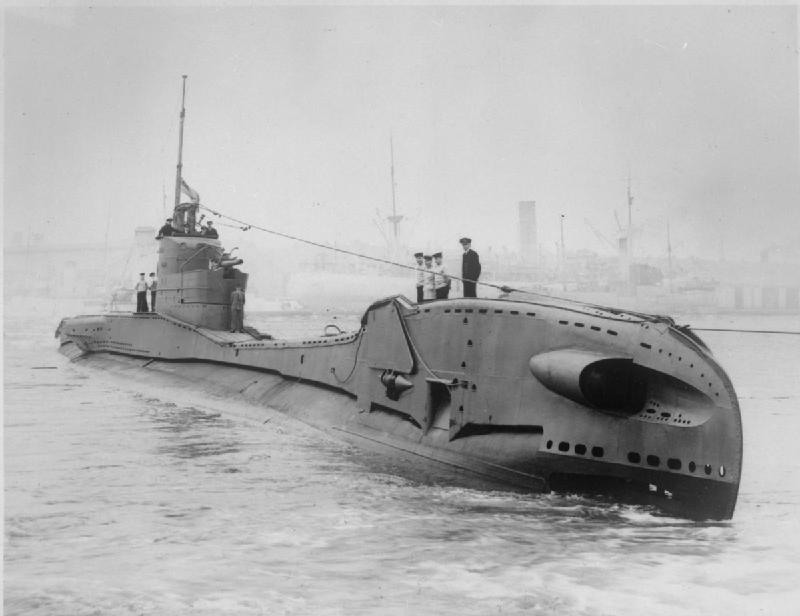

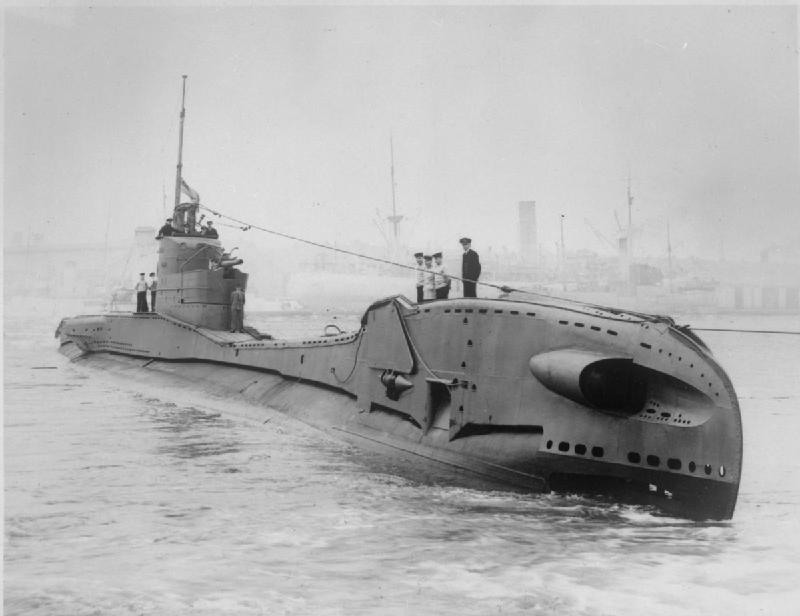

On 4 February 1942, Atherton and two other field agents, Lieutenant Radoje Nedeljković of the Yugoslav Royal Air Force and Sergeant Patrick O'Donovan, an Irish born radio operator, went ashore just north of Petrovac from the British submarine HMS Thorn

Three vessels of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Altho ...

. Alternative sources state that O'Donovan held the rank of Corporal, and that the two were joined by a Flying Officer Medelkovic (not Nedeljković), as well as a Sergeant Djekic.

Despite careful planning, Operation Hydra failed completely. The presence of former Yugoslav Royal Air Force officer implied strong links to the

Despite careful planning, Operation Hydra failed completely. The presence of former Yugoslav Royal Air Force officer implied strong links to the Chetniks

The Chetniks,, ; formally the Chetnik Detachments of the Yugoslav Army, and also the Yugoslav Army in the Homeland; and informally colloquially the Ravna Gora Movement, was a Kingdom of Yugoslavia, Yugoslav royalist and Serbian nationalist m ...

; a royalist and nationalist movement and guerrilla force established following the invasion of Yugoslavia in 1941.

Tito would have been fully aware that the British had already established close ties with Mihailović, a Serb

The Serbs ( sr-Cyr, Срби, Srbi, ) are a South Slavic ethnic group native to Southeastern Europe who share a common Serbian ancestry, culture, history, and language. They primarily live in Serbia, Kosovo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia ...

general and leader of the Chetniks, since October 1941. Consequently, Tito suspected his British guests of being adversarial spies to the Yugoslav partisan cause, and nothing beneficial arose from Atherton's time with Tito, and his British guests departed. Thereafter, what became of Atherton and the rest of the Op Hydra team during April 1942 is unclear. His luck had finally run out, since both he and his team disappeared without a trace. It is likely that he was targeted for the gold sovereigns (worth £2000), and Italian money (1 million Lira) that he carried around his own waist.

A Partisan perspective

The Yugoslav Partisan perceived aim of Operation Hydra was to establish and maintain communication with the Chetnik headquarters, and not establish a relationship with them. Once ashore, Atherton and his team began their journey towards Chetnik headquarters in February 1942. However they were intercepted and redirected to their local headquarters. Atherton was prevented from continuing the perceived Op Hydra mission to rendezvous with the Chetniks; and they spent several weeks, in a futile attempt to persuade Atherton to change his anti-communist sentiment and pro-Chetnik position.Moša Pijade

Moša Pijade (, alternate English transliteration Moshe Piade; – 15 March 1957), was a Serbian and Yugoslavia, Yugoslav painter, journalist, Communist Party of Yugoslavia, Communist Party politician, World War II participant, and a close ...

took Atherton to the Partisan headquarters in Foča

Foča ( sr-Cyrl, Фоча, ) is a town and municipality in Republika Srpska, Bosnia and Herzegovina, located in the south-east on the banks of Drina river. As of 2013, the town has a population of 12,234 inhabitants, while the municipality has 1 ...

to meet Tito, who was very suspicious about him and alerted Croatian communists of the British mission. Atherton vanished from their headquarters in Foča between the night of the 15th, and the morning of 16 April 1942, along with his team.

An initial Chetnik perspective

Chetnik sources during World War II, emphasised that during Atherton's stay in Foča, he was able to learn that Croatian communists organized cooperation between Partisans andUstaše

The Ustaše (), also known by anglicised versions Ustasha or Ustashe, was a Croats, Croatian fascist and ultranationalist organization active, as one organization, between 1929 and 1945, formally known as the Ustaša – Croatian Revolutionar ...

, a Croatian fascist and ultranationalist organisation, so Partisans had to kill him to prevent him from sending a report about the level of cooperation the Partisans had with Ustaše.

He was allegedly last seen, accompanied only by O’Donovan on 22 April 1942 when he headed walking towards German controlled territory.

Sequence of events

Atherton left Alexandria in Egypt on 17 January 1942 and disembarked off the coast of Montenegro on 4 February 1942. Atherton carried a substantial quantity of gold strapped around his waist. He was accompanied by an Irish radio operator and one officer of the Yugoslav Air Force. Atherton had to travel from theAdriatic coast

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) to ...

through the territory controlled by Axis forces, as well as Partisans, in order to reach Chetnik headquarters. A couple of days after Atherton and members of his mission disembarked, they met the battalion controlled by Jovan Tomašević

Jovan may refer to:

*Jovan (given name), a list of people with this given name

*Jovan, Mawal, a village on the western coastal region of Maharashtra, India

*Jōvan Musk, a cologne

*Deli Jovan, a mountain in eastern Serbia

*Róbert Jován (born 196 ...

. Tomašević took them to the headquarter of the Lovćen Partisan Detachment. The Partisans were suspicious about their mission because believed that their contemporary conflict with Montenegrin Chetniks was a result of the British and Yugoslav government-in-exile

The Government of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in Exile ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, Vlada Kraljevine Jugoslavije u egzilu, Влада Краљевине Југославије у егзилу) was an official government-in-exile of Yugoslavia, headed by King ...

orders sent with Atherton's mission. Ivan Milutinović

Ivan Milutinović (nickname Milutin; sr-cyr, Иван Милутиновић; 27 September 1901 – 23 October 1944) was a Yugoslav Partisan general and an eminent military commander who participated in World War II.

Before the war

In October ...

wanted to kill the British agents when they arrived to the Partisan HQ on 12 February 1942, because he thought they were acting on behalf of the Yugoslav government-in-exile, but he did not do it because he received a letter from Tito instructing them to bring Atherton and his team to the headquarter of supreme command near Foča. Tito informed Comintern

The Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern and also known as the Third International, was a political international which existed from 1919 to 1943 and advocated world communism. Emerging from the collapse of the Second Internatio ...

about arrival of one British mission, and on 28 February 1942, he received their reply that they knew nothing about this mission, which additionally increased the Communists suspicions. Tito also remained very suspicious about the Atherton, although Vladimir Dedijer

Vladimir Dedijer ( sr-Cyrl, Владимир Дедијер; 4 February 1914 – 30 November 1990) was a Yugoslav partisan fighter during World War II who became known as a politician, human rights activist, and historian. In the early postwar ...

recognised Atherton, having met him in London prior to World War II, while he was the correspondent of Politika

( sr-Cyrl, Политика, lit=Politics) is a Serbian daily newspaper, published in Belgrade. Founded in 1904 by Vladislav F. Ribnikar, it is the oldest daily newspaper still in circulation in the Balkans.

Publishing and ownership

is publ ...

.

Milutinović was instructed by Tito not to allow the Op Hydra team to have contact with the Chetniks. Instead they were kept in some kind of captivity, isolated from Partisan forces and ordinary people, under the watchful eye of the Lovćen

Lovćen ( cnr-Cyrl, Ловћен, ) is a mountain and national park in southwestern Montenegro. It is the inspiration behind the names ''Montenegro'' and ''Crna Gora'', both of which mean 'Black Mountain' and refer to the appearance of Mount ...

Partisan Detachment Atherton in Partisan Headquarter for Montenegro

, image_flag = Flag of Montenegro.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Montenegro.svg

, coa_size = 80

, national_motto =

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map = Europe-Mont ...

and Gulf Kotor in Gostilj, near Danilovgrad

Danilovgrad (Cyrillic: Даниловград) is a town in central Montenegro. It has a population of 6,852, according to the 2011 census. It is situated in the Danilovgrad Municipality which lies along the main route between Montenegro's two la ...

in period between 12 February 1942 until 10 March 1942 when they headed to supreme Partisan Headquarters in Foča

Foča ( sr-Cyrl, Фоча, ) is a town and municipality in Republika Srpska, Bosnia and Herzegovina, located in the south-east on the banks of Drina river. As of 2013, the town has a population of 12,234 inhabitants, while the municipality has 1 ...

.

Between then 19 and 22 March 1942, Atherton and members of his mission reached Foča

Foča ( sr-Cyrl, Фоча, ) is a town and municipality in Republika Srpska, Bosnia and Herzegovina, located in the south-east on the banks of Drina river. As of 2013, the town has a population of 12,234 inhabitants, while the municipality has 1 ...

where they stayed until 15 April 1942. In Foča in March 1942 he also met Vladimir Velebit

Vladimir "Vlatko" Velebit, PhD (19 August 1907 – 29 August 2004) was a Yugoslav politician, diplomat and military leader who rose the rank of Major-General during World War II. A lawyer by profession, after the war he became a diplomat an ...

who later confirmed that for Atherton Partisans were only "a bypass or way station" en route to Draža Mihailović

Dragoljub "Draža" Mihailović ( sr-Cyrl, Драгољуб "Дража" Михаиловић; 27 April 1893 – 17 July 1946) was a Yugoslavs, Yugoslav Serb general during World War II. He was the leader of the Chetniks, Chetnik Detachments ...

, just as they had experienced with Hudson the previous year. During his stay in Foča with the Yugoslav Partisans, Atherton contacted with his supreme command using his radio station.

On 6 April 1942, Tito wrote a letter to Pijade, expressing his concerns about Atherton's mission. On 8 April 1942 a secret directive was issued to the communist commissars to warn them about Atherton. This secret directive was allegedly issued to the Communist Party of Croatia

League of Communists of Croatia (, SKH) was the Croatian branch of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia (SKJ). It came into power in 1945. Until 1952, it was known as Communist Party of Croatia (, KPH). The party dissolved in 1990.

History

...

According to some anticommunist sources, Atherton was able to learn about contacts between Tito and his most trusted men from the Central Committee of Croatia with leaders of the Independent State of Croatia

The Independent State of Croatia (, NDH) was a World War II–era puppet state of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy (1922–1943), Fascist Italy. It was established in parts of Axis occupation of Yugoslavia, occupied Yugoslavia on 10 April 1941, ...

. This sources emphasize that Partisans and Ustaše made an agreement according to which Ustaše allowed Partisans to enter Foča, supplied them with ammunition to fight against Chetniks and to stay in Foča for several months without any obstruction from Croatian side. Some pro-Chetnik sources even emphasize that Partisans killed Atherton because he had intention to inform his superiors about the cooperation between Partisans and Ustaše.

Tito was afraid that Atherton was a member of just one of many other British missions who were all encouraging Chetniks to attack communists. The Chetnik attacks on communist forces in the region coincided with arrival of the Atherton's mission. Based on the discussions during the session of the Central Communist Committee held on 4 April 1942, Tito issued instructions to find and isolate all British missions. Tito suggested to Atherton not to continue his voyage toward Chetniks, and it was understood by Atherton that he was forbidden to leave Foča.

Whilst Atherton was a "guest" of the Partisans, they tried to convince him to change his pro-Chetnik and anti-Communist orientation. Ivan Milutinović

Ivan Milutinović (nickname Milutin; sr-cyr, Иван Милутиновић; 27 September 1901 – 23 October 1944) was a Yugoslav Partisan general and an eminent military commander who participated in World War II.

Before the war

In October ...

had numerous exhausting polemics with Atherton in futile attempts to convince him to change his positive view about Chetnik leader Draža Mihailović. Pijade took him on a tour of inspection of the organization of the communist forces in Žabljak

Žabljak (Cyrillic script, Cyrillic: Жабљак, ) is a small town in Montenegro in the Northern Montenegro, northern region. It has a population of 1,723.

Žabljak is the seat of Žabljak Municipality (2011 population: 3,569). The town is in ...

. When they arrived at Partisans headquarter near Foča, Atherton also met Vladimir Dedijer

Vladimir Dedijer ( sr-Cyrl, Владимир Дедијер; 4 February 1914 – 30 November 1990) was a Yugoslav partisan fighter during World War II who became known as a politician, human rights activist, and historian. In the early postwar ...

who showed him some agreement about alleged Chetniks cooperation with Milan Nedić

Milan Nedić ( sr-Cyrl, Милан Недић; 2 September 1878 – 4 February 1946) was a Yugoslav and Serbian army general and politician who served as the Chief of the General Staff of the Royal Yugoslav Army and minister of war in the ...

. The communists claimed that Yugoslav government-in-exile approved that agreement and that it was the proof of collaboration between Chetniks and Axis forces. Tito presented to Atherton his proposal to establish new Yugoslav Government from democratic elements from both Yugoslavia and abroad and to invite population of Yugoslavia to rebel against Axis, condemning all collaborators with occupying Axis forces.

At the beginning of April 1942, Atherton was taken by Partisans for an "inspection tour of the front", towards Rogatica in order to demonstrate that only the Partisans were fighting against the Axis. The Yugoslav post-war sources emphasize that Partisans managed to convince Atherton to change his pro-Chetnik and anticommunist view at the extent that he began arguing with General Petar Nedeljković

Petar Nedeljković (9 August 1882 – 1 November 1955) was an Army general (Kingdom of Yugoslavia), army general in the Royal Yugoslav Army who commanded the 4th Army (Yugoslavia), 4th Army during the German-led invasion of Yugoslavia of Ap ...

, according to the letter sent to Pijade by Tito on 11 April 1942.

Atherton secretly left Foča during the night between 15 and 16 April 1942 with support of General Nedeljković and local Chetnik commander Spasoje Dakić and hid in caves around Čelebići until 22 April. He left his radio station with Partisans in Foča. The Partisans sent their units to search for Atherton as soon as they realised they left Foča.

On 22 April 1942, Atherton sent a letter to Mihailović in which he asked Mihailović to inform his superiors that he was alive and that he would shortly be sending more information.

Latas explained that Atherton had some disagreements with General Nedeljković and on 22 April 1942, continued on foot, headed towards German-occupied Serbia to seek Mihailović, accompanied only by O'Donovan. Latas further explain that two of them were shadowed by Spasoje Dakić until they approached a village of Tatarevina. What became of the other team members of Op Hydra is a mystery.

Atherton was allegedly killed on 15 July 1942 by a bandit. However at the end of the war his murder, and the murder of his sergeant was described as a war crime.

Subsequent SOE missions

Atherton's friend and former assistant editor at the South Slav Herald in Belgrade, Alexander Simić-Stevens took part in Operation Fungus which departedDerna, Libya

Derna (; ') is a port city in eastern Libya. With a population of around 90,000, Derna was once the seat of one of the wealthiest provinces among the Barbary States. The city is now the administrative capital of Derna District, which covers ...

in April 1943. Another simultaneous SOE mission, Operation Hoathley 1 took place simultaneously. Each mission served as each other's backup to increase the chances of British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

success.

Testimonials

Some early accounts explained that Atherton was executed by Partisans because they concluded he brought "undesired influence" from Cairo. The War Diaries of Vladimir Dedijer: From 28 November 1942, to 10 September 1943, indicate that Atherton may have been part of a plot to assassinate Tito. Based on initial testimonies that he was killed by Partisans, ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' published an article blaming them for his death, which was denied by a letter written by Tito (the future Yugoslav Head of State) himself.

An account given by Ljubo Novaković

Ljubo Novaković ( sr-Cyrl, Љубо Новаковић; 1883–1943) was a Montenegrin officer in the Royal Yugoslav Army who became a Chetnik commander during World War II. He initially fought for the Chetniks of Draža Mihailović and those of ...

, a 60 year old former Brigadier General captured by Partisans and taken to Foča in January 1942 presents a twist. Novaković was kept under constant surveillance; and months later would meet Atherton upon Op Hydra's arrival in Foča. These circumstances raise the possibility that the British mission may have been murdered by Partisans. It is likely that Tito had initially planned to eventually use Novaković to counteract Mihailović's influence among Chetniks in eastern Bosnia. However Atherton's arrival presented an opportunity for Novaković who left Foča on 15 April 1942 without Tito's knowledge, allegedly with Atherton. Before leaving, Novaković left Tito a note in which he threatened to raise 5,000 Chetniks to fight the Partisans in eastern Bosnia. Furious, Tito became convinced that the British had devised an elaborate plot to disadvantage the Partisans by strengthening the Chetniks

The Chetniks,, ; formally the Chetnik Detachments of the Yugoslav Army, and also the Yugoslav Army in the Homeland; and informally colloquially the Ravna Gora Movement, was a Kingdom of Yugoslavia, Yugoslav royalist and Serbian nationalist m ...

. Novaković survived one more year, however Atherton may still have been betrayed by a rogue band of Chetniks.

After Atherton's disappearance, Partisan sources subsequently blamed the Chetniks, while SOE, British Ministers, and Western media sources initially blamed the Yugoslav Partisans, collectively they later accepted the probability that Atherton and his team were instead killed by Chetniks.

The British liaison officer at Mihailović's headquarters, Bill Hudson, insisted Mihailović conduct a formal inquiry into the fate of Major Atherton's mission. It would have seemed ironic to Hudson, that Atherton's mission had primarily been to ascertain his own whereabouts in January 1941. Atherton was effectively chosen to be his rescuer; and now Hudson was trying to investigate Atherton's untimely death. A summary of the results of this investigation was sent by Hudson, nown by the nom de guerre Markoto SOE office in Cairo. According to the results of the inquiry, the most probable culprit for Atherton's death was Četnik leader Spasoje Dakić.

According to the late Croatian military historian Jozo Tomašević

Josip "Jozo" Tomasevich (1908October 15, 1994; ) was an American economist and historian whose speciality was the economic and social history of Yugoslavia. Tomasevich was born in the Kingdom of Dalmatia, then part of Austria-Hungary, and after ...

, the investigation led by Hudson and William Bailey concluded that Atherton was murdered and robbed by local Chetnik commander Spasoje Dakić in the village of Tatarovina, in modern-day Northern Montenegro. According to some sources, Dakić was a commander of Chetnik battalion from Čelebići. According to Dedijer, Dakić was a criminal from Montenegro.

Post war investigation and release of records to the general public

Further investigation into Atherton's untimely death continued in the aftermath of the war. Yugoslav sources indicated the strong likelihood that Atherton was killed by Chetniks. The person who committed murder remained unknown. The post-war Yugoslav sources later complained that at that particular point in time (1941–42), the Allies had increased their support to the Chetniks who were challenging Partisan superiority, instead of supporting the "genuine anti-Axis partisan forces". On 14 February 1945, in theHouse of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

, Miss Irene Ward

Irene Mary Bewick Ward, Baroness Ward of North Tyneside, (23 February 1895 – 26 April 1980) was a British Conservative Party politician. She was the Member of Parliament (MP) successively for Wallsend and for Tynemouth for over three decad ...

, MP asked the Secretary of State for War whether he could make a statement on the death of Atherton. The British government response delivered by the Under-Secretary of State for War

Undersecretary (or under secretary) is a title for a person who works for and has a lower rank than a secretary (person in charge). It is used in the executive branch of government, with different meanings in different political systems, and is a ...

, Arthur Henderson MP was that the circumstances in which he died 3 years prior were still unclear. He may have been killed by partisans, or by the Germans.

In 1946, the new regime in Belgrade staged a politically and ideologically motivated trial of Draža Mihailović, which resulted in his death sentence. The unresolved mystery of Atherton and his teams disappearance was an integral part of the trial, likely to justify an ideological purpose. Later during the trial under cross examination Mihailović advised that he had conducted a personal inquiry in 1942 into the likely murder of Atherton, who admitted that he had probably been executed on the orders of one of his subordinate generals. The Times of London added that Mihailović thought that the murder was instigated by Novakovich, who aimed to be recognised as the supreme commander of Serbia. Mihailović was executed on 17 July 1946, together with nine other officers for their crimes.

In the 1988, Sir Fitzroy Maclean, 1st Baronet

Sir Fitzroy Hew Royle Maclean, 1st Baronet (11 March 1911 – 15 June 1996), was a British Army officer, writer and politician. A Unionist Member of Parliament (MP) from 1941 to 1974 Maclean was one of only two soldiers who during the Second Wor ...

, responsible for Maclean Mission

The Maclean Mission (MACMIS) was a World War II British mission to Yugoslav partisans HQ and Marshal Tito organised by the Special Operations Executive (SOE) in September 1943. Its aim was to assess the value of the partisans contribution to t ...

of 1943,

expressed concern about the unsolved case of the disappearance of Atherton, and the possible involvement by Momčilo Đujić

Momčilo Đujić ( sh-Cyrl, Момчилo Ђујић, ; 27 February 1907 – 11 September 1999) was a Serbian Orthodox Church, Serbian Orthodox priest and Chetnik . He led a significant proportion of the Chetniks within the northern Dalm ...

and his Dinara Division

The Dinara Division () was an irregular Chetnik formation that existed during the World War II Axis occupation of Yugoslavia that largely operated as auxiliaries of the occupying forces and fought the Yugoslav Partisans. Organized in 1942 with ass ...

in Atherton's likely capture and execution. This view by Brigadier Maclean was reported in the Times of London.

Atherton's heroics were archived in London, away from Public access for many years, and his name fell into obscurity, until 30 June 1997. It was only on 1 July 1997 that the Daily Mail of London reported on page 15, "Tragic Mystery of Mailman who led Commando Mission". A Daily Mail journalist (one of their own) had died a hero's death on a mission behind enemy lines during World War II.

Atherton was at the opposite end of the political spectrum of his coordinator in Cairo, Klugmann and this may have put his life at risk. Less than a year after Atherton's death, Churchill switched his support to Tito, having been previously aligned with the Serb Royalist leader General Draža Mihailović, who was at the time the chief beneficiary of British aid and support in the resistance movement in Yugoslavia. It is likely that Klugmann's reports influenced this change in policy, which coincided with Atherton being on the ground in Yugoslavia, leading Operation Hydra. These circumstances are likely to be justification for Atherton's records remaining closed for 61 years after his disappearance. His records within the National Archives

National archives are the archives of a country. The concept evolved in various nations at the dawn of modernity based on the impact of nationalism upon bureaucratic processes of paperwork retention.

Conceptual development

From the Middle Ages i ...

were not open to the public until April 2003.

Some authors blame the persistent misreporting of the BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

and attribution of successful Chetnik anti-Axis actions to Communists on a supposed strong network of Soviet spies in the BBC and the British Ministry of Information. This misreporting changed British public opinion and even influenced some high-ranking officials. At the same time some historians have said that such BBC broadcasts potentially put Atherton and other field agents at greater risk.

Memorial and legacy

Atherton is honoured and remembered, as part of theGeneral Service Corps

The General Service Corps (GSC) is a corps of the British Army.

Role

The role of the corps is to provide specialists, who are usually on the Special List or General List. These lists were used in both World Wars for specialists and those not allo ...

. His memorial is at the Phaleron War Cemetery in Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

. His date of death is marked as 15 July 1942, although he may have died as early as 17 April 1942. It is unusual that other members of Operation Hydra have not been added to this war memorial.

In addition to his war service, Atherton should be remembered for promoting Balkan co-operation in the 1930s, as well as an understanding of the Balkans by the English speaking communities of the issues that are considered most important to each of the various ethnicities living in the region. He founded the South Slav Herald in 1931 and The Balkan Herald in 1934. His articles have been published on across the globe.

Dramatisation

Atherton appears as the main character of the Yugoslav-3 part mini-series ''The Mission of Major Atherton'', directed by Sava Mrmak, where he was played by Slovenian actor Majtaž Višnar.See also

*Yugoslavia and the Allies

In 1941 when the Axis invaded Yugoslavia, King Peter II formed a Government in exile in London, and in January 1942 the royalist Draža Mihailović became the Minister of War with British backing. But by June or July 1943, British Prime Minister ...

* History of the Balkans

The Balkans, partly corresponding with the Balkan Peninsula, encompasses areas that may also be placed in Southeastern, Southern, Central and Eastern Europe. The distinct identity and fragmentation of the Balkans owes much to its often turbulen ...

* Chetnik sabotage of Axis communication lines

The Chetniks,, ; formally the Chetnik Detachments of the Yugoslav Army, and also the Yugoslav Army in the Homeland; and informally colloquially the Ravna Gora Movement, was a Kingdom of Yugoslavia, Yugoslav royalist and Serbian nationalist m ...

* Charles Armstrong (British Army officer)

* Western betrayal

Western betrayal is the view that the United Kingdom, France and the United States failed to meet their legal, diplomatic, military and moral obligations to the Czechoslovakians and Poles before, during and after World War II. It also sometimes ...

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Atherton, Terence 1902 births 1942 deaths British Special Operations Executive personnel British anti-communists 20th-century British journalists British Army personnel killed in World War II British Army General List officers People from Wavertree Military personnel from Liverpool 20th-century Royal Air Force personnel Royal Air Force airmen Special Operations Executive personnel killed in World War II