Tennessee Territory on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Territory South of the River Ohio, more commonly known as the Southwest Territory or the old Southwest Territory, was an

/ref> In 1784, North Carolina ceded control of the Overmountain settlements following a hotly contested vote. The cession was rescinded later that year, but not before some of the settlers had organized the

The new territory was essentially governed under the same provisions as the

The new territory was essentially governed under the same provisions as the

Residents of the Southwest Territory initially welcomed federal control, believing the federal government would provide better protection from hostile Indians than North Carolina's distant government to the east. However, the Federal government was already more focused on critical affairs in the old Northwest Territory. Most of the land in the "

Residents of the Southwest Territory initially welcomed federal control, believing the federal government would provide better protection from hostile Indians than North Carolina's distant government to the east. However, the Federal government was already more focused on critical affairs in the old Northwest Territory. Most of the land in the "

A census in the summer of 1791 showed the territory's population to be 35,691. There were 6,271 free adult white males, more than the 5,000 needed for the territory to organize a legislature. Blount, however, waited until 1793 to call for elections. Members of the territorial House of Representatives (the lower chamber of the legislature) were elected in December 1793, and the first House session convened on February 24, 1794. The representatives nominated ten individuals for appointment to the territorial council (the legislature's upper chamber), five of whom—

A census in the summer of 1791 showed the territory's population to be 35,691. There were 6,271 free adult white males, more than the 5,000 needed for the territory to organize a legislature. Blount, however, waited until 1793 to call for elections. Members of the territorial House of Representatives (the lower chamber of the legislature) were elected in December 1793, and the first House session convened on February 24, 1794. The representatives nominated ten individuals for appointment to the territorial council (the legislature's upper chamber), five of whom—

Tennessee Blue Book

'' (2012), p. 566. Hopkins Lacy was elected clerk.William Robertson Garrett and Albert Virgil Goodpasture,

History of Tennessee

' (Brandon Printing Company, 1903), p. 109. Members of the territorial council were appointed by the President from a list of candidates submitted by the territorial House of Representatives. At its first session in February 1794, the House submitted ten candidates for the council: James Winchester, William Fort, Stockley Donelson, Richard Gammon, David Russell,

The Southwest Territory covered , consisting of what is now Tennessee, with the exception of a few minor boundary changes resulting from later surveys. To its north was Virginia's

The Southwest Territory covered , consisting of what is now Tennessee, with the exception of a few minor boundary changes resulting from later surveys. To its north was Virginia's  The Washington District initially included lands north of the

The Washington District initially included lands north of the

"Fort Blount"

''Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture''. Accessed 10 November 2013. The population of the Southwest Territory in 1791 was 35,691. This included 3,417 slaves and 361 free persons of color. The population of the Washington District was 28,649, while the population of Mero was 7,042. The territory's 1795 census showed a total population of 77,262 inhabitants, including 10,613 slaves and 973 free persons of color. The population of the Washington and Hamilton districts was 65,338, and the population of Mero was 11,924.

Southwest Ordinance of 1790

at Tennessee GenWeb.com *

"Journal of the proceedings of the Legislative council of the territory of the United States of America, South of the river Ohio: begun and held at Knoxville, the 25th day of August, 1794"

at archives.org. {{Territories of the United States 1790 establishments in the United States 1796 disestablishments in the United States Pre-statehood history of Tennessee

organized incorporated territory of the United States

The territory of the United States and its overseas possessions has evolved over time, from the colonial era to the present day. It includes formally organized territories, proposed and failed states, unrecognized breakaway states, internatio ...

that existed from May 26, 1790, until June 1, 1796, when it was admitted to the United States as the State of Tennessee

Tennessee (, ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Kentucky to the north, Virginia to the northeast, North Carolina t ...

. The Southwest Territory was created by the Southwest Ordinance which was similar to the previous two ordinances passed by the Confederation Congress

The Congress of the Confederation, or the Confederation Congress, formally referred to as the United States in Congress Assembled, was the governing body of the United States from March 1, 1781, until March 3, 1789, during the Confederation ...

for the parallel establishment and development of the old Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from part of the unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolution. Established ...

of 1786–1803. It pertained to lands situated north of the Ohio River

The Ohio River () is a river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing in a southwesterly direction from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to its river mouth, mouth on the Mississippi Riv ...

, around the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes spanning the Canada–United States border. The five lakes are Lake Superior, Superior, Lake Michigan, Michigan, Lake Huron, H ...

and extending west to the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

. The lands of the Territory were taken from western areas beyond the mountains of the Commonwealth of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

(later to be separated and erected into the new 15th state

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

of the Commonwealth of Kentucky

Kentucky (, ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north, West Virginia to the ...

.) Western lands were also ceded by the state of North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

from lands of the Washington District

The Washington District is a Norfolk Southern Railway line in the U.S. state of Virginia that connects Alexandria and Lynchburg. Most of the line was built from 1850 to 1860 by the Orange and Alexandria Railroad, while a small portion in th ...

that had been already ceded

The act of cession is the assignment of property to another entity. In international law it commonly refers to land transferred by treaty. Ballentine's Law Dictionary defines cession as "a surrender; a giving up; a relinquishment of jurisdicti ...

to the U.S. federal government

The Federal Government of the United States of America (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States.

The U.S. federal government is composed of three distinct branches: legislative, execut ...

by North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

.

The territory's first—and only—appointed governor for its existence was William Blount

William Blount ( ; April 6, 1749March 21, 1800) was an American politician, landowner and Founding Father who was one of the signers of the Constitution of the United States. He was a member of the North Carolina delegation at the Constitution ...

, and the appointed secretary of the territory was Daniel Smith. Both were appointed by President George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

.

The establishment of the Southwest Territory followed a series of efforts by North Carolina's trans-Appalachia

Trans-Appalachia is an area in the United States bounded to the east by the Appalachian Mountains and extending west roughly to the Mississippi River. It spans from the Midwest to the Upper South. The term is used most frequently when referring to ...

n settlers to form a separate political entity, initially with the Watauga Association

The Watauga Association (sometimes referred to as the Republic of Watauga) was a semi-autonomous government created in 1772 by frontier settlers living along the Watauga River in what is now Elizabethton, Tennessee. Although it lasted only a fe ...

, and later with the failure of the additional proposed western State of Franklin

The State of Franklin (also the Free Republic of Franklin, Lost State of Franklin, or the State of Frankland) was an unrecognized proposed U.S. state, state located in present-day East Tennessee, in the United States. Franklin was created in ...

. North Carolina ceded these lands in April 1790 as payment of obligations owed to the new central federal government.

It was also along with the intention, that when the previous governing document for the newly independent United States of the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union

The Articles of Confederation, officially the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, was an agreement and early body of law in the Thirteen Colonies, which served as the nation's first frame of government during the American Revolutio ...

which were drawn up in 1776–1778 and adopted unanimously finally in 1781, that the territories west of the Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, are a mountain range in eastern to northeastern North America. The term "Appalachian" refers to several different regions associated with the mountain range, and its surrounding terrain ...

would be ceded to the Confederation Congress

The Congress of the Confederation, or the Confederation Congress, formally referred to as the United States in Congress Assembled, was the governing body of the United States from March 1, 1781, until March 3, 1789, during the Confederation ...

, to be held in trust for all of the original Thirteen States

The Thirteen Colonies were the British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America which broke away from the British Crown in the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), and joined to form the United States of America.

The Thirteen Co ...

, in order to settle and create in the future of new federal territories and states to be admitted to the Union on an equal basis and status. The Southwest Territory's residents welcomed the cession, believing the federal government would provide better protection from native Indian hostilities. The federal government paid relatively little attention however to the territory, increasing its residents' desire for full statehood and admittance to the federal Union.

Along with Blount, a number of individuals who played prominent roles in early Tennessee history served in the old Southwest Territory's administration. These included John Sevier

John Sevier (September 23, 1745 September 24, 1815) was an American soldier, frontiersman, and politician, and one of the founding fathers of the State of Tennessee. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, he played a leading role in Tennes ...

, James Robertson, Griffith Rutherford

Griffith Rutherford (c. 1721 – August 10, 1805) was an American military officer in the Revolutionary War and the Cherokee-American Wars, a political leader in North Carolina, and an important figure in the early history of the Southwes ...

, James Winchester, Archibald Roane

Archibald Roane (1759/60 – January 18, 1819) was the second Governor of Tennessee, serving from 1801 to 1803. He won the office after the state's first governor, John Sevier, was prevented by constitutional restrictions from seeking a fourth c ...

, John McNairy

John McNairy (March 30, 1762 – November 12, 1837) was a U.S. federal judge in Tennessee. He was the judge for the Southwest Territory, and for the United States District Court for the District of Tennessee, the United States District Court for ...

, Joseph McMinn

Joseph McMinn (June 22, 1758 – October 17, 1824) was an American politician who served as the fourth Governor of Tennessee from 1815 to 1821. A veteran of the American Revolutionary War, American Revolution, he had previously served in the leg ...

and General and future seventh President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

, Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

.

Background

During the colonial period, land that would become the Southwest Territory was part ofNorth Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

's land patent

A land patent is a form of letters patent assigning official ownership of a particular tract of land that has gone through various legally-prescribed processes like surveying and documentation, followed by the letter's signing, sealing, and publi ...

. The Blue Ridge Mountains

The Blue Ridge Mountains are a Physiographic regions of the United States, physiographic province of the larger Appalachian Highlands range. The mountain range is located in the Eastern United States and extends 550 miles southwest from southern ...

, which rise along the modern Tennessee-North Carolina border, hindered North Carolina from pursuing any lasting interest in the territory. Initially trade, political interest, and settlement came mostly from Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

and South Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

, though refugees from the Regulator War began arriving from North Carolina in the early 1770s.

The Watauga Association

The Watauga Association (sometimes referred to as the Republic of Watauga) was a semi-autonomous government created in 1772 by frontier settlers living along the Watauga River in what is now Elizabethton, Tennessee. Although it lasted only a fe ...

was a semi-autonomous government created in 1772 by frontier settlers living along the Watauga River

The Watauga River () is a large stream of western North Carolina and East Tennessee. It is long with its headwaters in Linville Gap to the South Fork Holston River at Boone Lake.

Course

The Watauga River rises from a spring located south to ...

in what is present day Elizabethton, Tennessee

Elizabethton () is a city in, and the county seat of Carter County, Tennessee, United States. Elizabethton is the historical site of the first independent American government (known as the Watauga Association, created in 1772) located west of ...

. The colony was established on Cherokee

The Cherokee (; , or ) people are one of the Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, they were concentrated in their homelands, in towns along river valleys of what is now southwestern ...

-owned land in which the Watauga and Nolichucky settlers had negotiated a 10-year lease directly with the Indians. Fort Watauga was established on the Watauga River at Sycamore Shoals

The Sycamore Shoals of the Watauga River, usually shortened to Sycamore Shoals, is a rocky stretch of river rapids along the Watauga River in Elizabethton, Tennessee. Archeological excavations have found Native Americans lived near the shoals ...

as a trade center of the settlements.

In March 1775, land speculator and North Carolina judge Richard Henderson met with more than 1,200 Cherokees at Sycamore Shoals. Included at the gathering were Cherokee leaders such as Attacullaculla

Attakullakulla (Cherokee”Tsalagi”, (ᎠᏔᎫᎧᎷ) ''Atagukalu'' and often called Little Carpenter by the English) (c. 1715 – c. 1777) was an influential Cherokee leader and the tribe's First Beloved Man, serving from 1761 to ar ...

, Oconostota

Oconostota (c. 1707–1783) was a Cherokee '' skiagusta'' (war chief) of Chota, which was for nearly four decades the primary town in the Overhill territory, and within what is now Monroe County, Tennessee. He served as the First Beloved Man o ...

, and Dragging Canoe

Dragging Canoe (ᏥᏳ ᎦᏅᏏᏂ, pronounced ''Tsiyu Gansini'', – February 29, 1792) was a Cherokee red (or war) chief who led a band of Cherokee warriors who resisted colonists and United States settlers in the Upper South. During the Ame ...

. The meeting resulted in the "Treaty of Sycamore Shoals

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between sovereign states and/or international organizations that is governed by international law. A treaty may also be known as an international agreement, protocol, covenant, convention ...

", in which Henderson purchased from the Cherokee all the land situated south of the Ohio River

The Ohio River () is a river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing in a southwesterly direction from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to its river mouth, mouth on the Mississippi Riv ...

and lying between the Cumberland River

The Cumberland River is a major waterway of the Southern United States. The U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed June 8, 2011 river drains almost of southern Kentucky and ...

, the Cumberland Mountains

The Cumberland Mountains are a mountain range in the southeastern section of the Appalachian Mountains. They are located in western Virginia, southwestern West Virginia, the eastern edges of Kentucky, and eastern middle Tennessee, including the ...

, and the Kentucky River

The Kentucky River is a tributary of the Ohio River in Kentucky, United States. The river and its tributaries drain much of eastern and central Kentucky, passing through the Eastern Coalfield, the Cumberland Mountains, and the Bluegrass re ...

. This land, which encompassed roughly 20 million acres (80,000 km2), became known as the Transylvania Purchase. Henderson's land deal was found to be in violation of North Carolina and Virginia law, as well as the Royal Proclamation of 1763

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued by British King George III on 7 October 1763. It followed the Treaty of Paris (1763), which formally ended the Seven Years' War and transferred French territory in North America to Great Britain. The ...

, which had prohibited the private purchase of American Indian land.

Both North Carolina and Virginia considered the trans-Appalachian settlements illegal, and refused to annex them. Nevertheless, at the onset of the American War for Independence

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

in 1776, the settlers, who vigorously supported the Patriot cause, organized themselves into the "Washington District" and formed a committee of safety to govern it. In July 1776, Dragging Canoe and the faction of the Cherokee opposed to the Transylvania Purchase (later called the Chickamaugas) aligned with the British and launched an invasion of the Watauga settlements, targeting Fort Watauga at modern Elizabethton and Eaton's Station near modern Kingsport

Kingsport is a city in Sullivan and Hawkins counties in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It lies along the Holston River and had a population of 55,442 at the 2020 census. It is the largest city in the Kingsport–Bristol metropolitan area, w ...

. After the settlers thwarted the attacks, North Carolina agreed to annex the settlements as the Washington District

The Washington District is a Norfolk Southern Railway line in the U.S. state of Virginia that connects Alexandria and Lynchburg. Most of the line was built from 1850 to 1860 by the Orange and Alexandria Railroad, while a small portion in th ...

.

In September 1780, a large group of trans-Appalachian settlers, led by William Campbell, John Sevier

John Sevier (September 23, 1745 September 24, 1815) was an American soldier, frontiersman, and politician, and one of the founding fathers of the State of Tennessee. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, he played a leading role in Tennes ...

and Isaac Shelby

Isaac Shelby (December 11, 1750 – July 18, 1826) was an American politician and military officer who was the List of governors of Kentucky, first and fifth Governor of Kentucky and served in the state legislatures of Virginia and North Ca ...

, assembled at Sycamore Shoals in response to a British threat to attack frontier settlements. Known as the Overmountain Men

The Overmountain Men were American frontiersmen from west of the Blue Ridge Mountains which are the leading edge of the Appalachian Mountains, who took part in the American Revolutionary War. While they were present at multiple engagements in t ...

, the settlers marched across the mountains to South Carolina, where they engaged and defeated a loyalist

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cr ...

force led by Patrick Ferguson

Major Patrick Ferguson (1744 – 7 October 1780) was a British Army officer who designed the Ferguson rifle. He is best known for his service in the 1780 military campaign of Charles Cornwallis during the American Revolutionary War in the ...

at the Battle of Kings Mountain

The Battle of Kings Mountain was a military engagement between Patriot and Loyalist militias in South Carolina during the southern campaign of the American Revolutionary War, resulting in a decisive victory for the Patriots. The battle took pl ...

. Overmountain Men would also take part in the Battle of Musgrove Mill

The Battle of Musgrove Mill, August 19, 1780, occurred near a ford of the Enoree River, near the present-day border between Spartanburg, Laurens and Union Counties in South Carolina. During the course of the battle, 200 Patriot militiamen def ...

and the Battle of Cowpens

The Battle of Cowpens was a military engagement during the American Revolutionary War fought on January 17, 1781, near the town of Cowpens, South Carolina. American Patriot (American Revolution), Patriot forces, estimated at 2,000 militia and reg ...

.U.S. National Park Service./ref> In 1784, North Carolina ceded control of the Overmountain settlements following a hotly contested vote. The cession was rescinded later that year, but not before some of the settlers had organized the

State of Franklin

The State of Franklin (also the Free Republic of Franklin, Lost State of Franklin, or the State of Frankland) was an unrecognized proposed U.S. state, state located in present-day East Tennessee, in the United States. Franklin was created in ...

, which sought statehood. John Sevier

John Sevier (September 23, 1745 September 24, 1815) was an American soldier, frontiersman, and politician, and one of the founding fathers of the State of Tennessee. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, he played a leading role in Tennes ...

was named governor and the area began operating as an independent state not recognized by the Congress of the Confederation

The Congress of the Confederation, or the Confederation Congress, formally referred to as the United States in Congress Assembled, was the governing body of the United States from March 1, 1781, until March 3, 1789, during the Confederation ...

. Many Overmountain settlers, led by John Tipton

John Shields Tipton (August 14, 1786 – April 5, 1839) was from Tennessee and became a farmer in Indiana; an officer in the 1811 Battle of Tippecanoe, and veteran officer of the War of 1812, in which he reached the rank of Brigadier General; ...

, remained loyal to North Carolina, and frequently quarreled with the Franklinites. Following Tipton's defeat of Sevier at the "Battle of Franklin" in early 1788, the State of Franklin movement declined. The Franklinites had agreed to rejoin North Carolina by early 1789.

Territory formation

North Carolina ratified theUnited States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, on March 4, 1789. Originally includi ...

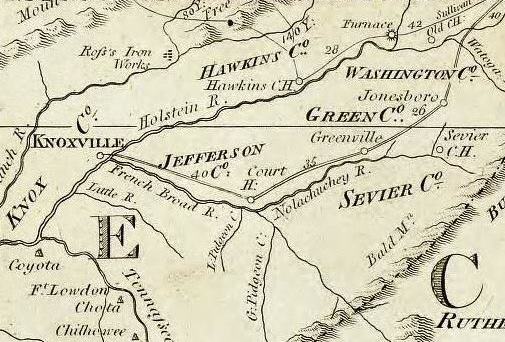

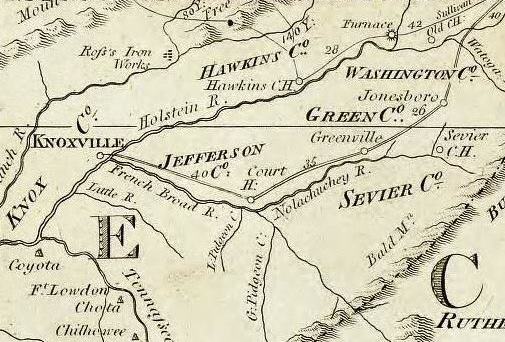

on November 21, 1789. On December 22, the state legislature voted to cede the Overmountain settlements as payment of its obligations to the new federal government.Walter T. Durham, "The Southwest Territory: Progression to Statehood", ''Journal of East Tennessee History'', Vol. 62 (1990), pp. 3–17. Congress accepted the cession during its first session on April 2, 1790, when it passed "An Act to Accept a Cession of the Claims of the State of North Carolina to a Certain District of Western Territory".Walter T. Durham, "The Territory of the United States South of the River Ohio", ''Before Tennessee: The Southwest Territory, 1790–1796'' (Rocky Mount Historical Association, 1990), pp. 31–46. On May 26, 1790, Congress passed an act organizing the new cession as the "Territory of the United States South of the River Ohio", which consisted of modern Tennessee, with the exception of later minor boundary changes. However, most of the new territory was under Indian control, with territorial administration initially covering two unconnected areas—the Washington District in what is now northeast Tennessee, and the Mero District around Nashville. The act also merged the office of territorial governor with the office of Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Southern Department.

The new territory was essentially governed under the same provisions as the

The new territory was essentially governed under the same provisions as the Northwest Ordinance

The Northwest Ordinance (formally An Ordinance for the Government of the Territory of the United States, North-West of the River Ohio and also known as the Ordinance of 1787), enacted July 13, 1787, was an organic act of the Congress of the Co ...

, a 1787 act enacted for the creation of the Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from part of the unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolution. Established ...

north of the Ohio River. The Northwest Ordinance's provision outlawing slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

was not applied to the Southwest Territory, however. Along with rules of governance, the Ordinance outlined steps a territory could take to gain admission to the Union. The first step involved the organization of a territorial government. The next step, which would take place when the territory had at least 5,000 adult males, was to organize a territorial legislature, with a popularly elected lower chamber and an upper chamber appointed by the president. The final step, which would take place when the territory had a population of at least 60,000, was to write a state constitution and elect a state government, at which time the territory would be admitted to the Union.

Several candidates were put forth for governor of the new territory. William Blount

William Blount ( ; April 6, 1749March 21, 1800) was an American politician, landowner and Founding Father who was one of the signers of the Constitution of the United States. He was a member of the North Carolina delegation at the Constitution ...

, a Constitutional Convention delegate and former state legislator who had championed the causes of western settlers, was supported by key North Carolina politicians such as Hugh Williamson

Hugh Williamson (December 5, 1735 – May 22, 1819) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father, physician, and politician. He is best known as a Signature, signatory to the U.S. Constitution and for representing Nort ...

, Timothy Bloodworth

Timothy James Bloodworth (1736August 24, 1814) was an American anti-Federalist politician. He was a leader of the American Revolution and later served as a member of the Confederation Congress, U.S. congressman and senator, and collector of custom ...

, John B. Ashe and Benjamin Hawkins

Benjamin Hawkins (August 15, 1754June 6, 1816) was an American planter, statesman and a U.S. Indian agent. He was a delegate to the Continental Congress and a United States Senator from North Carolina, having grown up among the planter elite ...

. Blount, an aggressive land speculator, had extensive land holdings in the new territory. Virginia's Patrick Henry

Patrick Henry (May 29, 1736 ld Style and New Style dates, O.S. May 18, 1736une 6, 1799) was an American politician, planter and orator who declared to the Virginia Conventions, Second Virginia Convention (1775): "Give me liberty or give m ...

called for his friend, General Joseph Martin Joseph Martin may refer to:

Military

*Joseph Martin (general) (1740–1808), American Revolutionary War general from Virginia

*Joseph Plumb Martin (1760–1850), American soldier and memoir writer

* Joseph M. Martin (born 1962), U.S. Army officer

...

, to be appointed governor. A small group of ex-Franklinites convened in Greeneville to push for the appointment of John Sevier.

On June 8, 1790, President George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

chose Blount as the territory's new governor. He also appointed Daniel Smith the territory's Secretary, and named two of the territory's three judges, John McNairy

John McNairy (March 30, 1762 – November 12, 1837) was a U.S. federal judge in Tennessee. He was the judge for the Southwest Territory, and for the United States District Court for the District of Tennessee, the United States District Court for ...

and David Campbell (Joseph Anderson Joseph Anderson may refer to:

Politics

*Joe Anderson (politician) (born 1958), mayor of Liverpool

*Joseph Anderson (South Australian politician) (1876–1947), and accountant, real estate

*Joseph C. Anderson (1830–1891), member of the Kansas T ...

would eventually be chosen as the third judge). John Sevier was appointed brigadier general of the Washington District militia, and James Robertson was appointed brigadier general of the Mero District militia.

In September 1790, Blount visited Washington at Mount Vernon

Mount Vernon is the former residence and plantation of George Washington, a Founding Father, commander of the Continental Army in the Revolutionary War, and the first president of the United States, and his wife, Martha. An American landmar ...

, and was sworn in by Supreme Court justice James Iredell

James Iredell (October 5, 1751 – October 20, 1799) was one of the first justices of the Supreme Court of the United States. He was appointed by President George Washington and served from 1790 until his death in 1799. His son, James Iredel ...

. He then moved to the new territory, where he set up a temporary capital at Rocky Mount, the home of William Cobb in Sullivan County. He recruited North Carolina publisher George Roulstone to establish a newspaper, the ''Knoxville Gazette

The ''Knoxville Gazette'' was the first newspaper published in the U.S. state of Tennessee and the third published west of the Appalachian Mountains. Established by George Roulstone (1767–1804) at the urging of Southwest Territory governor W ...

'' (initially published at Rogersville). He spent most of October and November issuing appointments to lower-level administrative and militia positions. In December, he made the dangerous trip across Indian territory to the Mero District, where he likewise issued appointments, before returning to Rocky Mount by the end of the year.

Blount initially wanted the permanent territorial capital to be located at the confluence of the Clinch and Tennessee

Tennessee (, ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Kentucky to the north, Virginia to the northeast, North Carolina t ...

rivers (in the vicinity of modern Kingston

Kingston may refer to:

Places

* List of places called Kingston, including the six most populated:

** Kingston, Jamaica

** Kingston upon Hull, England

** City of Kingston, Victoria, Australia

** Kingston, Ontario, Canada

** Kingston upon Thames, ...

), where he had extensive land claims, but was unable to convince the Cherokee to relinquish ownership of these lands. He therefore chose James White's Fort, an outpost located further upstream along the Tennessee. In 1791, White's son-in-law, Charles McClung

Charles McClung (May 13, 1761August 9, 1835) was an American pioneer, politician, and surveyor best known for drawing up the original plat of Knoxville, Tennessee, in 1791. While Knoxville has since expanded to many times its original size, the ...

, platted the new city, and lots were sold in October of that year. Blount named the new city "Knoxville" after his superior in the War Department, Henry Knox

Henry Knox (July 25, 1750 – October 25, 1806) was an American military officer, politician, bookseller, and a Founding Father of the United States. Knox, born in Boston, became a senior general of the Continental Army during the Revolutionar ...

.

In the 1790 United States census

The 1790 United States census was the first United States census. It recorded the population of the whole United States as of Census Day, August 2, 1790, as mandated by Article 1, Section 2, of the Constitution and applicable laws. In the first ...

, 7 counties in the Southwest Territory reported the following population counts:

Indian hostilities

Residents of the Southwest Territory initially welcomed federal control, believing the federal government would provide better protection from hostile Indians than North Carolina's distant government to the east. However, the Federal government was already more focused on critical affairs in the old Northwest Territory. Most of the land in the "

Residents of the Southwest Territory initially welcomed federal control, believing the federal government would provide better protection from hostile Indians than North Carolina's distant government to the east. However, the Federal government was already more focused on critical affairs in the old Northwest Territory. Most of the land in the "Old Southwest

The "Old Southwest" is an informal name for the southwestern frontier territories of the United States from the American Revolutionary War , through the early 1800s, at which point the US had acquired the Louisiana Territory, pushing the sout ...

" was still either Indian territory or had already been claimed by speculators or settlers, and thus there was little money to be made from land sales. President Washington issued a proclamation forbidding the violation of the Treaty of Hopewell

Three agreements, each known as a Treaty of Hopewell, were signed between representatives of the Congress of the United States and the Cherokee, Choctaw, and Chickasaw peoples. They were negotiated and signed at the Hopewell plantation in South ...

(which had set Indian boundaries), and Secretary of War Knox frequently accused settlers of illegally encroaching on Indian lands. Blount was consistently torn between placating angry frontiersmen and appeasing his superiors in the Federal government.

In the Summer of 1791, Blount negotiated the Treaty of Holston

The Treaty of Holston (or Treaty of the Holston) was a treaty between the United States government and the Cherokee signed on July 2, 1791, and proclaimed on February 7, 1792. It was negotiated and signed by William Blount, governor of the So ...

with the Cherokee at the future site of Knoxville. The Treaty brought lands south of the French Broad River

The French Broad River is a river in the U.S. states of North Carolina and Tennessee. It flows from near the town of Rosman, North Carolina, Rosman in Transylvania County, North Carolina, into Tennessee, where its confluence with the Holston R ...

and east of the divide between Little River

Little River may refer to several places:

Australia Streams New South Wales

*Little River (Dubbo), source in the Dubbo region, a tributary of the Macquarie River

* Little River (Oberon), source in the Oberon Shire, a tributary of Coxs River (Haw ...

and the Little Tennessee River

The Little Tennessee River (known locally as the Little T) is a tributary of the Tennessee River that flows through the Blue Ridge Mountains from Georgia, into North Carolina, and then into Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. It dra ...

(essentially modern Cocke, Sevier and Blount counties) under U.S. control, and guaranteed the Territory use of a road between the Washington and Mero districts, as well as the Tennessee River. The following year, Blount negotiated an agreement clarifying land boundaries with the Chickasaw

The Chickasaw ( ) are an Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands, United States. Their traditional territory was in northern Mississippi, northwestern and northern Alabama, western Tennessee and southwestern Kentucky. Their language is ...

, who controlled what is now West Tennessee

West Tennessee is one of the three Grand Divisions of Tennessee that roughly comprises the western quarter of the state. The region includes 21 counties between the Tennessee and Mississippi rivers, delineated by state law. Its geography consists ...

.

In spite of these agreements, continued encroachment by settlers onto Indian lands prompted reprisals, which primarily came from hostile Chickamauga Cherokee

The Chickamauga Cherokee is a Native American group who separated from the Cherokee from the American Revolutionary War to the early 1800s. Most of the Cherokee people signed peace treaties with the Americans in 1776-1777, after the Second Chero ...

and Creek Indians

The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek or just Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy ( in the Muscogee language; English: ), are a group of related Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern WoodlandsSpanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many countries in the Americas

**Spanish cuisine

**Spanish history

**Spanish culture

...

, who controlled Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

along the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico () is an oceanic basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, mostly surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north, and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States; on the southw ...

coast and still disputed the southern borders of the United States, fifteen years after the end of the Revolutionary War, encouraged and armed the southern tribes. These attacks persisted throughout 1792 and 1793, with the Mero settlements bearing the brunt of the hostilities. Ziegler's Station near modern Hendersonville was destroyed, and Mero defenders had to rally to thwart a large invasion at Buchanan's Station

Buchanan's Station was a fortified stockade established around 1784 in Tennessee. Founded by Major John Buchanan (frontiersman), John Buchanan, the settlement was located in what is today the Donelson, Tennessee, Donelson neighborhood of Nashvi ...

near Nashville. In spite of growing impatience from frontiersmen, Secretary of War Knox refused to authorize an invasion of Indian territory.

In September 1793, while Blount was away in Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

, a large group of Cherokee invaders overran Cavet's Station west of Knoxville, and were planning to march on Knoxville before the invading force dissolved due to infighting among chiefs. Territorial Secretary Daniel Smith, who was Acting Governor

An acting governor is a person who acts in the role of governor. In Commonwealth jurisdictions where the governor is a vice-regal position, the role of "acting governor" may be filled by a lieutenant governor (as in most Australian states) or a ...

in Blount's absence, summoned the militia and ordered an invasion of Cherokee

The Cherokee (; , or ) people are one of the Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, they were concentrated in their homelands, in towns along river valleys of what is now southwestern ...

territory. Militia General Sevier led the militia south and destroyed several Chickamauga villages. While Blount supported Smith's decision, the invasion angered Knox, who refused to issue pay for the militiamen. In September 1794, Robertson, without authorization from Knox, dispatched a mounted American force under James Ore

James may refer to:

People

* James (given name)

* James (surname) James is a surname in the French language, Albert Dauzat, ''Noms et prénoms de France'', Librairie Larousse 1980, édition revue et commentée par Marie-Thérèse Morlet, p. 340a ...

which destroyed the Chickamauga towns of Nickajack and Running Water. Robertson resigned as brigadier general shortly afterward.

The defeat of northern tribes at the Battle of Fallen Timbers

The Battle of Fallen Timbers (20 August 1794) was the final battle of the Northwest Indian War, a struggle between Indigenous peoples of North America, Native American tribes affiliated with the Northwestern Confederacy and their Kingdom of Gre ...

in August 1794, the destruction of Nickajack and Running Water, and the resolving of boundary disputes between the United States and Spain led to a decline in hostile Indian attacks. In November 1794, Blount negotiated an end to the Cherokee–American wars

The Cherokee–American wars, also known as the Chickamauga Wars, were a series of raids, campaigns, ambushes, minor skirmishes, and several full-scale frontier battles in the Old Southwest from 1776 to 1794 between the Cherokee and American se ...

at the Tellico Blockhouse

The Tellico Blockhouse was an early American outpost located along the Little Tennessee River in what developed as Vonore, Monroe County, Tennessee. Completed in 1794, the blockhouse was a US military outpost that operated until 1807; the garris ...

, a federal outpost south of Knoxville.

Statehood

A census in the summer of 1791 showed the territory's population to be 35,691. There were 6,271 free adult white males, more than the 5,000 needed for the territory to organize a legislature. Blount, however, waited until 1793 to call for elections. Members of the territorial House of Representatives (the lower chamber of the legislature) were elected in December 1793, and the first House session convened on February 24, 1794. The representatives nominated ten individuals for appointment to the territorial council (the legislature's upper chamber), five of whom—

A census in the summer of 1791 showed the territory's population to be 35,691. There were 6,271 free adult white males, more than the 5,000 needed for the territory to organize a legislature. Blount, however, waited until 1793 to call for elections. Members of the territorial House of Representatives (the lower chamber of the legislature) were elected in December 1793, and the first House session convened on February 24, 1794. The representatives nominated ten individuals for appointment to the territorial council (the legislature's upper chamber), five of whom—Griffith Rutherford

Griffith Rutherford (c. 1721 – August 10, 1805) was an American military officer in the Revolutionary War and the Cherokee-American Wars, a political leader in North Carolina, and an important figure in the early history of the Southwes ...

, John Sevier, James Winchester, Stockley Donelson and Parmenas Taylor—were eventually appointed by President Washington. Rutherford was chosen as the council's president.

The assembly first convened on August 26, 1794, and called for immediate steps to be taken to achieve full statehood. The assembly appointed Dr. James White (not to be confused with Knoxville's founder) as its non-voting representative in Congress, making the Southwest Territory one of the first U.S. territories to make use of this power. A special session of the assembly on June 29, 1795, called for a census to be taken the following month to determine if the territory's population had reached the 60,000 threshold required for statehood. The census revealed a population of 77,262 inhabitants.

After the census, the territory moved swiftly to form a state government. In December 1795, counties elected delegates for the state constitutional convention. This convention met in Knoxville in January 1796, and drafted a new state constitution. The name "Tennessee", which had been in common use since 1793 when Secretary Smith published his "Short Description of the Tennassee Government", was chosen as the new name for the state.

The Northwest Ordinance was vague on the final steps to be taken for a state to be fully admitted to the Union, so Tennessee's leaders proceeded to organize a state government. John Sevier was elected governor, the first Tennessee General Assembly convened in March 1796, and Blount notified the Secretary of State, Timothy Pickering

Timothy Pickering (July 17, 1745January 29, 1829) was the third United States Secretary of State, serving under Presidents George Washington and John Adams. He also represented Massachusetts in both houses of United States Congress, Congress as ...

, that the territorial government had been terminated. A copy of the state constitution was delivered to Pickering by future governor Joseph McMinn

Joseph McMinn (June 22, 1758 – October 17, 1824) was an American politician who served as the fourth Governor of Tennessee from 1815 to 1821. A veteran of the American Revolutionary War, American Revolution, he had previously served in the leg ...

. Blount and William Cocke

William Cocke (1748August 22, 1828) was an American lawyer, pioneer, and statesman. He has the distinction of having served in the state legislatures of four different states: Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Mississippi, and was one of ...

were chosen as the state's U.S. Senators, and Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

was elected the state's representative. As the Southwest Territory was the first federal territory to petition to join the Union, there was confusion in Congress about how to proceed. Nonetheless, Tennessee was admitted to the Union on June 1, 1796, as the 16th state.

Government and law

The Southwest Territory was governed under an act of Congress, "An Act for the Government of the Territory of the United States, South of the River Ohio" (Southwest Ordinance), passed May 26, 1790. This act essentially mirrored the earlierNorthwest Ordinance

The Northwest Ordinance (formally An Ordinance for the Government of the Territory of the United States, North-West of the River Ohio and also known as the Ordinance of 1787), enacted July 13, 1787, was an organic act of the Congress of the Co ...

, the key difference being over slavery, which was prohibited by the Northwest Ordinance, but not the Southwest Ordinance. Both ordinances provided for freedom of religion and the sanctity of contracts, barred legal primogeniture

Primogeniture () is the right, by law or custom, of the firstborn Legitimacy (family law), legitimate child to inheritance, inherit all or most of their parent's estate (law), estate in preference to shared inheritance among all or some childre ...

, and encouraged the establishment of schools and respect for the liberty of the Indians.

The supreme power in the territory rested in the governor, who was appointed by the President of the United States. He was assisted by the Secretary, also appointed by the President. Legislative powers rested in a bicameral territorial assembly consisting of the House of Representatives (lower chamber) and the Territorial Council (upper chamber). Representatives were popularly elected, whereas councilors were appointed by the President. Judicial power rested in three judges appointed by the President. Brigadier generals of the territorial militia were also appointed by the President. Lower administrative, judicial and military officers were appointed by the governor.

Executive

The Governor of the Southwest Territory had supreme authority in the territory. The governor could decree ordinances, propose and enact new laws, create towns and counties, and license lawyers. Though the territorial assembly held legislative powers, the governor held veto power over all proposed laws. The governor was responsible for appointing the lower territorial administrative officers, including attorneys general, justices of the peace, registers, and court clerks. He recommended candidates for brigadier general to the President, and appointed lower militia officers. The governor also served as the Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Southern Department, the federal government's chief diplomat to the Southern tribes. To serve as governor, an individual had to own at least of land in the territory.William Blount

William Blount ( ; April 6, 1749March 21, 1800) was an American politician, landowner and Founding Father who was one of the signers of the Constitution of the United States. He was a member of the North Carolina delegation at the Constitution ...

served as Governor of the Southwest Territory throughout the territory's existence.

The Secretary of the Southwest Territory was the official record-keeper of the territory. The Secretary also served as acting governor

An acting governor is a person who acts in the role of governor. In Commonwealth jurisdictions where the governor is a vice-regal position, the role of "acting governor" may be filled by a lieutenant governor (as in most Australian states) or a ...

if the governor was absent or incapacitated. To serve as Secretary, an individual had to own at least of land in the territory. Daniel Smith served as Secretary throughout the territory's existence.

Legislature

Legislative power in the Southwest Territory initially rested with the governor, who consulted with the three territorial judges on new laws. After the territory's population of white males reached 5,000, the territory could form a legislative assembly (the power to summon the assembly rested with the governor). The assembly consisted of an upper chamber, the Territorial Council (the role of which was similar to that of a state senate), and a lower chamber, the House of Representatives. While the assembly could propose new laws, the governor could still veto any bill. To serve on the council, an individual had to own at least of land in the territory. The territorial House of Representatives consisted of thirteen popularly elected members. These members elected aspeaker

Speaker most commonly refers to:

* Speaker, a person who produces speech

* Loudspeaker, a device that produces sound

** Computer speakers

Speaker, Speakers, or The Speaker may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* "Speaker" (song), by David ...

from their own ranks. The House first convened at Knoxville on February 24, 1794. Its members were John Tipton

John Shields Tipton (August 14, 1786 – April 5, 1839) was from Tennessee and became a farmer in Indiana; an officer in the 1811 Battle of Tippecanoe, and veteran officer of the War of 1812, in which he reached the rank of Brigadier General; ...

(Washington), George Rutledge (Sullivan), Joseph Hardin (Greene), William Cocke

William Cocke (1748August 22, 1828) was an American lawyer, pioneer, and statesman. He has the distinction of having served in the state legislatures of four different states: Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Mississippi, and was one of ...

(Hawkins), Joseph McMinn

Joseph McMinn (June 22, 1758 – October 17, 1824) was an American politician who served as the fourth Governor of Tennessee from 1815 to 1821. A veteran of the American Revolutionary War, American Revolution, he had previously served in the leg ...

(Hawkins), Alexander Kelly (Knox), John Beard (Knox), Samuel Wear (Jefferson), George Doharty (Jefferson), David Wilson (Sumner), Dr. James White (Davidson) and James Ford (Tennessee County). Wilson, of Sumner County, served as Speaker from 1794 to 1795. Hardin, of Greene, served as Speaker from 1795 to 1796.Tennessee Blue Book

'' (2012), p. 566. Hopkins Lacy was elected clerk.William Robertson Garrett and Albert Virgil Goodpasture,

History of Tennessee

' (Brandon Printing Company, 1903), p. 109. Members of the territorial council were appointed by the President from a list of candidates submitted by the territorial House of Representatives. At its first session in February 1794, the House submitted ten candidates for the council: James Winchester, William Fort, Stockley Donelson, Richard Gammon, David Russell,

John Sevier

John Sevier (September 23, 1745 September 24, 1815) was an American soldier, frontiersman, and politician, and one of the founding fathers of the State of Tennessee. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, he played a leading role in Tennes ...

, Adam Meek, John Adair, Griffith Rutherford

Griffith Rutherford (c. 1721 – August 10, 1805) was an American military officer in the Revolutionary War and the Cherokee-American Wars, a political leader in North Carolina, and an important figure in the early history of the Southwes ...

and Parmenas Taylor. From this list, President Washington appointed Winchester, Donelson, Sevier, Rutherford and Taylor. Rutherford was chosen as council president (a role similar to speaker).

The Northwest Ordinance allowed a territory's assembly to elect a representative to the United States Congress. This representative could consult with congressmen on legislation, but could not vote. In 1794, the Southwest Territory's assembly chose Dr. James White as its non-voting representative to Congress. The Southwest Territory was the first U.S. territory to exercise this power, and White's efforts in Congress set a precedent for future territorial delegates.

Judiciary

The territory's supreme judicial power rested in three judges, each appointed by the President. The governor appointed court clerks, attorneys general and lower judicial offices, as well as justices of the peace. Along with their judicial powers, the judges could consult with the governor on new legislation, though the governor held final veto power over any proposed laws. To serve as a judge, an individual had to own at least of land in the territory. The judges appointed by President Washington in 1790 wereJohn McNairy

John McNairy (March 30, 1762 – November 12, 1837) was a U.S. federal judge in Tennessee. He was the judge for the Southwest Territory, and for the United States District Court for the District of Tennessee, the United States District Court for ...

(1762–1837), David Campbell (1750–1812), and Joseph Anderson Joseph Anderson may refer to:

Politics

*Joe Anderson (politician) (born 1958), mayor of Liverpool

*Joseph Anderson (South Australian politician) (1876–1947), and accountant, real estate

*Joseph C. Anderson (1830–1891), member of the Kansas T ...

(1757–1837). Blount appointed Francis Alexander Ramsey clerk of the Washington District's superior court of law, Andrew Russell clerk of the Washington District's court of equity, David Allison clerk of Mero's superior court of law, and Joseph Sitgreaves clerk of Mero's court of equity.

The courts of the Southwest Territory were generally more highly regarded than other branches of government. Frontiersmen had for years relied on county courts to settle disputes, and upon being appointed governor, Blount left the existing county courts largely intact. These courts generally followed old North Carolina laws when rendering decisions, relying heavily on James Iredell

James Iredell (October 5, 1751 – October 20, 1799) was one of the first justices of the Supreme Court of the United States. He was appointed by President George Washington and served from 1790 until his death in 1799. His son, James Iredel ...

's ''Revisal of the Laws of North Carolina'' (1791). Along with hearing criminal and civil cases, courts were responsible for licensing ferries

A ferry is a boat or ship that transports passengers, and occasionally vehicles and cargo, across a body of water. A small passenger ferry with multiple stops, like those in Venice, Italy, is sometimes referred to as a water taxi or water bus.

...

, regulating taverns, and designating public gristmill

A gristmill (also: grist mill, corn mill, flour mill, feed mill or feedmill) grinds cereal grain into flour and Wheat middlings, middlings. The term can refer to either the grinding mechanism or the building that holds it. Grist is grain that h ...

s. Courts occasionally rendered financial assistance for internal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, can ...

and relief for the destitute. County sheriffs were responsible for collecting taxes.

Lawyers were licensed by the governor to practice in the territory's courts. Notable individuals licensed to practice in the territory included future president Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

, future governor Archibald Roane

Archibald Roane (1759/60 – January 18, 1819) was the second Governor of Tennessee, serving from 1801 to 1803. He won the office after the state's first governor, John Sevier, was prevented by constitutional restrictions from seeking a fourth c ...

, future congressman John Rhea

John Rhea (pronounced ) (c. 1753May 27, 1832) was an American soldier and politician of the early 19th century who represented Tennessee in the United States House of Representatives. Rhea County, Tennessee and Rheatown, a community and for ...

, and Blount's younger half-brother, future governor Willie Blount

Willie Blount (April 18, 1768September 10, 1835) was an American politician who served as the third Governor of Tennessee from 1809 to 1815. Blount's efforts to raise funds and soldiers during the War of 1812 earned Tennessee the nickname, "Volun ...

. Jackson served as a district attorney for the territory.

Land details

The Southwest Territory covered , consisting of what is now Tennessee, with the exception of a few minor boundary changes resulting from later surveys. To its north was Virginia's

The Southwest Territory covered , consisting of what is now Tennessee, with the exception of a few minor boundary changes resulting from later surveys. To its north was Virginia's District of Kentucky

Kentucky County (aka Kentucke County), later the District of Kentucky, was formed by the Commonwealth of Virginia from the western portion (beyond the Big Sandy River and Cumberland Mountains) of Fincastle County effective 1777. The name of ...

, which became the 15th U.S. state in 1792. The lands to the territory's south were at the time either still claimed by Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

, or disputed with Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

, but subsequently consolidated into the Mississippi Territory

The Territory of Mississippi was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that was created under an organic act passed by the United States Congress, Congress of the United States. It was approved and signed into law by Presiden ...

.

At its creation in 1790, the Southwest Territory's administration oversaw two unconnected districts—the Washington District in the northeast, and the Mero District in the area around and north of Nashville. The remainder of the territory remained under Indian control, with the Cherokee

The Cherokee (; , or ) people are one of the Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, they were concentrated in their homelands, in towns along river valleys of what is now southwestern ...

being the dominant tribe in the east, and the Chickasaw

The Chickasaw ( ) are an Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands, United States. Their traditional territory was in northern Mississippi, northwestern and northern Alabama, western Tennessee and southwestern Kentucky. Their language is ...

controlling the western part of the territory. Other important tribes included the Creeks and Choctaw.

The Washington District initially included lands north of the

The Washington District initially included lands north of the French Broad River

The French Broad River is a river in the U.S. states of North Carolina and Tennessee. It flows from near the town of Rosman, North Carolina, Rosman in Transylvania County, North Carolina, into Tennessee, where its confluence with the Holston R ...

and northeast of the confluence of the Clinch and Tennessee

Tennessee (, ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Kentucky to the north, Virginia to the northeast, North Carolina t ...

rivers (near modern Kingston

Kingston may refer to:

Places

* List of places called Kingston, including the six most populated:

** Kingston, Jamaica

** Kingston upon Hull, England

** City of Kingston, Victoria, Australia

** Kingston, Ontario, Canada

** Kingston upon Thames, ...

). The 1791 Treaty of Holston pushed the boundary south of the French Broad and southeast to the divide between Little River and the Little Tennessee River (in what is now southern Blount County). The Washington District originally included Washington

Washington most commonly refers to:

* George Washington (1732–1799), the first president of the United States

* Washington (state), a state in the Pacific Northwest of the United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A ...

, Sullivan

Sullivan may refer to:

People

Characters

* Chloe Sullivan, from the television series ''Smallville''

* Colin Sullivan, a character in the film ''The Departed'', played by Matt Damon

* Harry Sullivan (''Doctor Who''), from the British science f ...

, Greene

Greene may refer to:

Places United States

*Greene, Indiana, an unincorporated community

* Greene, Iowa, a city

* Greene, Maine, a town

** Greene (CDP), Maine, in the town of Greene

* Greene (town), New York

**Greene (village), New York, in the to ...

and Hawkins counties. Knox and Jefferson were created by Governor Blount in 1792.Michael Toomey, Doing Justice to Suitors': The Role of County Courts in the Southwest Territory", ''Journal of East Tennessee History'', Vol. 62 (1990), pp. 33–53. In 1793, Blount organized these two new counties into a separate district, called the "Hamilton District".Stanley Folmsbee, Robert Corlew and Enoch Mitchell, ''Tennessee: A Short History'' (University of Tennessee Press, 1969), p. 100. Blount and Sevier counties would be added to this new district during territorial administration.

The Mero District included the lands around Nashville

Nashville, often known as Music City, is the capital and List of municipalities in Tennessee, most populous city in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is the county seat, seat of Davidson County, Tennessee, Davidson County in Middle Tennessee, locat ...

and along the Cumberland River

The Cumberland River is a major waterway of the Southern United States. The U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed June 8, 2011 river drains almost of southern Kentucky and ...

, north to the modern Kentucky border. It included three counties— Davidson, Sumner

Sumner may refer to:

Places Antarctica

* Mount Sumner, a mountain in the Rare Range, Antarctica

* Sumner Glacier, southern Graham Land, Antarctica

Australia

* Sumner, Queensland, a suburb of Brisbane

New Zealand

* Sumner, New Zealand, a seasi ...

and Tennessee

Tennessee (, ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Kentucky to the north, Virginia to the northeast, North Carolina t ...

. The Mero and Washington districts were connected by a road, generally known as Avery's Trace, which traversed Indian lands.Benjamin Nance"Fort Blount"

''Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture''. Accessed 10 November 2013. The population of the Southwest Territory in 1791 was 35,691. This included 3,417 slaves and 361 free persons of color. The population of the Washington District was 28,649, while the population of Mero was 7,042. The territory's 1795 census showed a total population of 77,262 inhabitants, including 10,613 slaves and 973 free persons of color. The population of the Washington and Hamilton districts was 65,338, and the population of Mero was 11,924.

See also

*Indian Reserve (1763)

"Indian Reserve" is a historical term for the largely uncolonized land in North America that was claimed by France, ceded to Great Britain through the Treaty of Paris (1763) at the end of the Seven Years' War—also known as the French and Indi ...

* Overhill Cherokee

The Overhill Cherokee were a group of the Cherokee people located in their historic settlements in what is now the U.S. state of Tennessee in the Southeastern United States, on the western side of the Appalachian Mountains. This name was used b ...

* United States Attorney for the District of Tennessee

References

Further reading

*External links

Southwest Ordinance of 1790

at Tennessee GenWeb.com *

"Journal of the proceedings of the Legislative council of the territory of the United States of America, South of the river Ohio: begun and held at Knoxville, the 25th day of August, 1794"

at archives.org. {{Territories of the United States 1790 establishments in the United States 1796 disestablishments in the United States Pre-statehood history of Tennessee